WILDFLOWER 2023 | Volume 40, No. 2 FUELING THE FALL MIGRATION WINTER BERRY BEAUTY GARDEN GRATITUDE + A TEAM EFFORT TO SAVE THE HOUSTON TOAD PAGE 18 Poised for a Comeback

Monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) have been wintering in the Sierra Madre mountains of Mexico since before recorded history. They arrive each year around November 1 and, in past eras, have been celebrated by local people as the souls of ancestors returning home for the season. Monarchs spend their Mexican winters clinging together — in clusters of millions — in oyamel fir ( Abiesreligiosa), pine (Pinus spp.) and cedar (Cedrus spp.) trees, coating their boughs completely in color. The butterflies stay in their winter home until the spring equinox nears, after which they travel as far north as Texas to lay their eggs. After the eggs are deposited for gestation, the butterflies die, and the next generation carries on their epic migration north. It is their grandchildren and great-grandchildren who will return to the Sierra Madre mountains after the summer in North America. They will not have seen these mountains or these forests before. But they will know them as home. PHOTO Elizaveta Kirina/ Shutterstock

Join us for our first Wildflower Centerhosted trip to view the monarchs at their winter home in Mexico this coming February. See wildflower.org/travel for more information.

FAR Afield

LOOK Closer 2 | WILDFLOWER

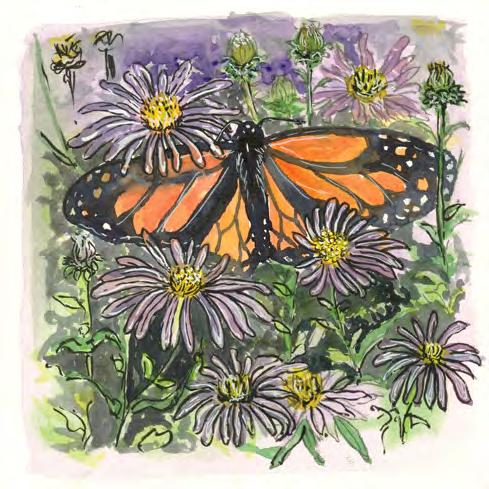

They say perspective is everything. What appears to be a superbly dyed and beautifully woven tribal artifact is in fact a monarch butterfly wing, magnified. Butterfly wings are made of two membranes that are nourished and supported by tubular veins, which support oxygen exchange for the body. Covering the wings are thousands of colorful scales. When the fully-grown adult butterfly emerges from its chrysalis, its delicate wings are crinkled, wet and uninflated. The butterfly hangs upside-down and pumps blood into the wings to inflate them. It must then wait for the wings to dry before it can fly. Strong muscles in the thorax move the wings up and down in a figure-eight pattern during flight. Butterfly wing scales also aid in survival because the scales are designed to come off easily. If a butterfly gets tangled up with a predator or in a spider web, they can more likely slip away by leaving a few scales behind. By the same token, touching a butterfly’s wings can rub its scales off, which can negatively affect wing functioning. When the fragile wings fray or are torn, they do not repair themselves. For these reasons, it is always best to admire butterflies from a distance, even if it’s a very short one.

PHOTO Chrisjbrownnz/Dreamstime

| 3

For Everything, There is a Season

AS THE SEASONS CHANGE, THERE’S A SHIFT THAT TAKES PLACE , and it isn’t only apparent in our landscapes and gardens. There’s a shift in lifestyle, habits and preferences, from the snow cone-fueled, warm vacation days of summer to the cooler, indoor-focused contemplative seasons. We shift from lighter “beach reads” to more hefty tomes. Many of us turn off the grill for the season and cook more indoors. Gardeners have their noses in seed catalogs. We move from outside to inside in many ways, both figuratively and literally.

This issue of Wildflower explores some of these themes. Whether it means appreciating the subtle beauty of winter berries in our own backyards, helping monarch butterflies on their way to their winter homes, or creating a healthy home for an endangered toad, there’s something gratifying and fitting about taking the time to look inward and focus our attention on the home front for a while. The months ahead give us a moment to regroup and gather our thoughts.

We’re doing that at the Wildflower Center too. After celebrating our 40-year anniversary in 2022, we are asking ourselves a lot of questions. With the meteoric growth of Austin, how does the Wildflower Center evolve to meet and serve our new neighbors? How do we extend our mission of inspiring the conservation of native plants to new people? How can we better tell our unique and inspiring story? How can we continue to inspire and delight our members and guests?

The Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center has grown from welcoming approximately 40,000 guests in its first year to 250,000 in 2023. This tells us that what we do remains more relevant than ever. People are deeply interested in the benefits of native plants, native landscapes, science-based land management, and the experiences we create.

We’re thinking about the future and making plans to ensure the Wildflower Center is ready for the next 40 years. We’re dreaming up new programs and ways to inspire you. Along with perennial favorites like Fortlandia and Luminations, we’re creating new programs that engage families in creative ways and looking at how we can create stronger digital experiences that extend our mission across the globe.

The season of contemplation, planning, rethinking and renewing is upon all of us, and I hope it’s a meaningful and beautiful one for you.

Stay wild,

Lee Clippard Executive Director

Lee Clippard Executive Director

4 | WILDFLOWER FROM THE Executive Director

The Draw of

| 5 7 PLANT PICKS Help fuel the fall migration with these pollinator favorites 10 BOTANY 101 Savoring and saving the beauty and abundance of America’s grasslands 12 URBAN GROWTH Phil Hardberger Park bridges a gap for San Antonio 15 PEN & PETAL Celebrating the season’s visual bounty 16 FIELD GUIDE Winter berries invite us to lean in 34 NEWS AND UPDATES The latest on our gardens and our work 38 THINGS WE LOVE What we’re loving right about now 39 THANK YOU, CORPORATE PARTNERS 40 PLANT PEOPLE Growing gardens and fostering community 46 CAN DO Not-so-odd bedfellows in the garden 48 WILD LIFE A gardener turns her pen to gratitude 40 ON THE COVER The Houston toad is ready for its close-up. PHOTO Houston Zoo ABOVE Sunlight catches a spider’s web in the urban garden of Andrew Ong and Jared Goza. PHOTO Ann Alva Wieding Saving the Toad’s Song One Texas vocalist is being brought back from the brink by

Asher Elbein

Nature How the act of creating fosters community by Carrie McDonald 18 26 FEATURES TABLE of Contents 34 16

Asher Elbein is a freelance journalist, fiction writer and artist based in Austin, Texas. His work has previously appeared in The New York Times, Texas Monthly, Scientific American, Audubon, and Undark.

Carrie McDonald has worked in horticulture and education and managed the volunteer program at the Wildflower Center for 17 years. She is currently also working toward completing her M.A. at the University of Texas in December 2023.

Judy Paul has been an artist and graphic designer in central Texas for over 30 years. When she’s not painting, taking photos or creating digital collages, she is finding inspiration while backpacking, biking, trail running or swimming in the

magic of Barton Springs.

Dyhanara Rios is the social media manager for the Wildflower Center. She combines her passion for environmental stewardship and digital media in her career and creative pursuits, including songwriting and poetry.

Kate Rowe is a freelance writer and editor specializing in gardening, food and children’s books. She studied cooking in France and has more than 20 years of cooking and gardening experience. She pairs picture book recommendations with garden and kitchen adventures @ ThePictureBookCook on Instagram.

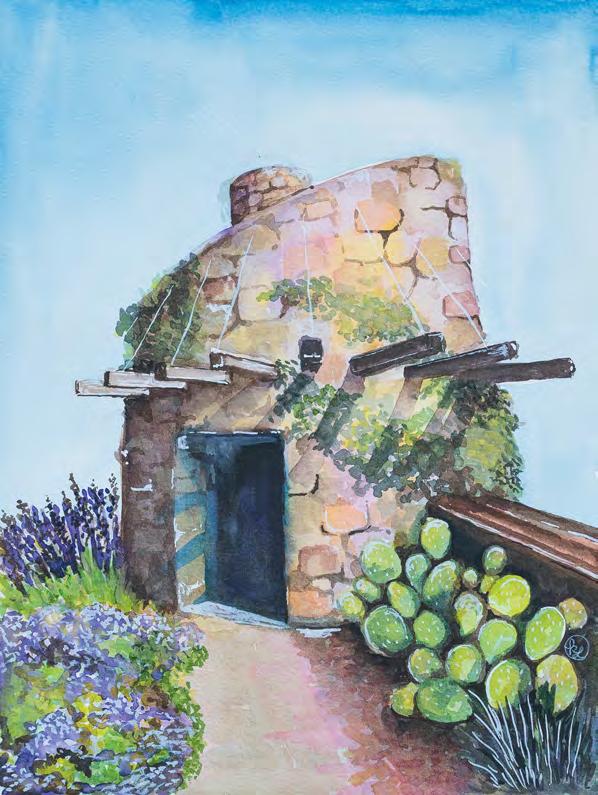

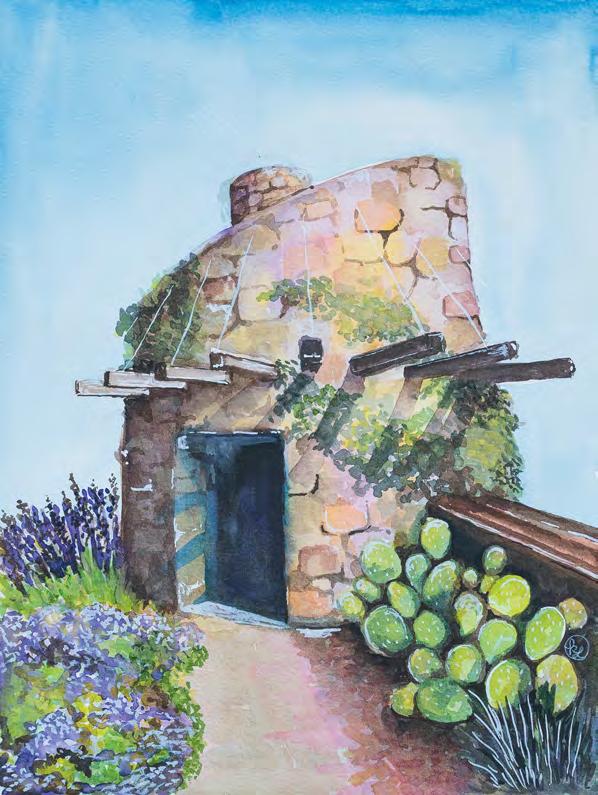

Lisa Spangler is a software engineer turned artist and lifelong plant nerd living in Austin, Texas. She

became a Wildflower Center member 20 years ago and has volunteered for vegetation monitoring and led plant walks. She served two terms as president of the Native Plant Society of Texas’ Austin Chapter. Lisa can be found roaming through nature doing field studies and considers herself a watercolor wanderer — make that a wonder-er, because watercolors never fail to fill her with joy and wonder, even when they’re misbehaving.

Ann Alva Wieding is a commercial, documentary and portrait photographer from Austin, Texas. As an avid gardener and naturalist with a background in Art & Museum Education, she combines her passion for the natural world with capturing environmental portraits of others doing the same. She loves to travel and wander through various environments, looking for flora and fauna in vast landscapes.

WILDFLOWER

2023 | Volume 40, No. 2

EDITOR

Scott Simons

DESIGNER

Joanna Wojtkowiak

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Elizabeth Standley

PLANT INFORMATION EDITOR Joseph Marcus

FOUNDERS

Lady Bird Johnson and Helen Hayes

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Lee Clippard

DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION

Demekia Biscoe

DIRECTOR OF HORTICULTURE

Andrea DeLong-Amaya

DIRECTOR OF SCIENCE & CONSERVATION

Sean Griffin

DIRECTOR OF LAND RESOURCES

Matt O’Toole

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING & COMMUNICATIONS

Scott Simons

DIRECTOR OF FINANCE

Cathy Tran

DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT

Leslie D. Zachary

ADVISORY COUNCIL

CHAIR Laura Beckworth

VICE CHAIR Jeanie Carter

SECRETARY Celina Romero

Wildflower (ISSN 1936-9646) is published biannually by The University of Texas at Austin Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, 4801 La Crosse Ave., Austin, TX 78739-1702. Copyright © 2023 by the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Members of the Wildflower Center receive a subscription as a benefit of membership. No part of this periodical may be reproduced without the written consent of the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. The opinions expressed herein may not necessarily reflect those held by the Wildflower Center. Please direct any inquiries or letters to 512.232.0100 or magazine@wildflower.org.

Materials are chosen for the printing and distribution of Wildflower magazine with respect for the environment. Wildflower is printed locally in Austin , Texas, by Capital Printing.

WILDFLOWER.ORG

facebook.com/wildflowercenter @wildflowercenter youtube.com/ WildflowerCenterAustin

6 | WILDFLOWER

FEATURED Contributors

MAXIMILIAN SUNFLOWER

Helianthus maximiliani

WHY WE LOVE THEM: Sunny, showy and easy to grow, this perennial provides nutrition to wildlife and a bright splash of color to the garden.

PREFERRED GARDEN ENVIRONMENT: Prefers moist, clay-like soil but can tolerate — and even flourish in — a wide variety of soils. Moderate water requirements and plenty of sun make this a repeat performer in the garden.

USES: Attractive color for the perennial border and palatable to deer and other wildlife. Attracts nectar-loving pollinators, including birds, bees and butterflies.

BRINGS THE BLOOMS: August to November, peaking in October

Beyond Milkweed

Asteraceae fuel the fall migrating pollinators and provide a reliable autumn show.

by Joseph Marcus

PLANT Picks

PHOTO Wildflower Center

FROSTWEED

Verbesina virginica

WHY WE LOVE THEM: They’re easy to grow and lend stately, dark green leaves and white, autumn flowers to areas with dappled shade. Winter ice ribbons that form on the plant are a bonus.

PREFERRED GARDEN ENVIRONMENT:

Thrives in partly shaded gardens and on the edges of woodlands, especially under live oaks. Likes well-drained, acidic or calcareous loam soils and has low-to-medium water requirements.

USES: Great as a naturalizing accent plant beneath live oaks. Useful as a transitional plant between manicured and wild areas.

BRINGS THE BLOOMS: July through December, mostly September and October

TEXAS GAYFEATHER

Liatris punctata var. mucronata

WHY WE LOVE THEM: With an upright habit that stands out in the garden, the vibrant flowering stems and elegant, swaying stalks add dimension and height to the landscape. Butterflies love the nectar of this striking perennial.

PREFERRED GARDEN ENVIRONMENT: Best in dry, rocky or gravelly soil and full sun. Afternoon shade can be helpful in exceptionally warm garden spaces.

USES: Gravel gardens and areas with naturally dry soil. Adds vertical interest to the garden border.

BRINGS THE BLOOMS: August through December

8 | WILDFLOWER

SHRUBBY BONESET

Ageratina havanensis

WHY WE LOVE THEM: The white to pinkish-white flowers are fragrant and showy, providing late summer and early fall color. May be transplanted almost year-round if cut back by one third. A pollinator magnet.

PREFERRED GARDEN ENVIRONMENT: Ideal for a woodland edge or dappled shade garden.

USES: Easily grown from seed and readily rooted from cuttings. Likes well-drained sand, loam, clay, and limestone soils. Prefers partly shaded areas but can survive in some sun.

SAND PALAFOX

Palafoxia hookeriana

WHY WE LOVE THEM: Tall and useful in the back of a border, this striking, pink-flowering beauty can sometimes grow up to six feet tall, though often two to three feet in height.

PREFERRED GARDEN ENVIRONMENT: Low water requirements and some flexibility in light requirements make this a more versatile reseeding annual than many. The blooming season can be prolonged with pruning and deadheading. Can thrive in many soil types.

USES: Lovely in a meadow environment or along a rocky or gravelly hillside.

BRINGS THE BLOOMS: June through October

BRINGS THE BLOOMS: April through December

Need more native plant info? Search our mobile-friendly Native Plants of North America database for bloom times, planting conditions and more: plants.wildflower.org

| 9

PHOTOS Wildflower Center

Restoring America’s Grasslands, Piece by Piece

How one conservationist rediscovered the vibrant, diverse beauty of native prairies

by Sean Griffin, Ph.D.

DRIVING THROUGH MILES UPON MILES of corn and soybean fields in the American Midwest, it can be difficult to imagine that most of the land was once natural habitat. Prior to colonization in the 1800s, over 150 million acres of tallgrass prairie stretched across North America — a seemingly endless expanse that early explorers referred to as a vast “ocean of grass.”

Now, less than 5% of that original grassland remains, representing a mind-boggling loss of biodiversity and making the North American prairie one of the most endangered ecosystems in the world. In the face of increased urbanization and human expansion, saving our native grassland plants and animals will require not only the protection of existing prairie remnants, but also the active recreation of habitats that have been lost.

10 | WILDFLOWER BOTANY 101

An American bison (Bison bison) herd grazes in a restored planting at the Nachusa Grasslands PHOTO Dee Hudson at The Nature Conservancy

In north-central Illinois, about 1.5 hours from the Chicago metroplex and surrounded by sprawling agriculture on all sides, a dedicated team of restorationists have made it their mission to create just such a refuge for prairie biodiversity. This gem, established as the Nachusa Grasslands in 1988 by the Nature Conservancy, is now one of the largest prairie restorations in North America with nearly 4,000 acres of remnant and restored tallgrass prairie, oak savannah, and wetland habitat.

Every year, teams of restoration practitioners, researchers and volunteers carefully manage and monitor Nachusa’s mosaic of habitat to encourage the return of native biodiversity and better understand the effects of restoration on these ecologies.

My story at Nachusa first began in 2013, when I was invited to collect bees across the restored prairies prior to a planned introduction of bison. At the time, I was a somewhat disillusioned graduate student in New Jersey, studying the bee communities of biofuel crops. The grasslands project didn’t seem related to my graduate work but on a whim, I decided to make the trek out to Illinois to set up what I thought would be a small, one-off study. What I didn’t know is that my experiences at Nachusa would ultimately change my life and lead me to pursue a career in restoration ecology.

Before that summer, I had never spent much time in prairies, believing them to be drab and uninteresting in comparison to flashier habitats such as wetlands or rainforests. What I experienced at Nachusa, however, totally upended that perception. Intensively managed with prescribed fire and native seeding, this prairie was bursting with beautiful biodiversity, carpeted in flowers and buzzing with life.

Further, the community of ecologists and volunteers at Nachusa was like nothing I’d seen, composed of nearly a hundred prairie fanatics so dedicated to the mission that some even moved from Chicago to be closer. Surrounded by this shared sense of purpose and a profound optimism for the future, I fell in love with the field of restoration ecology.

After that first prairie epiphany, I ended up moving on from my crop-focused research to pursue a Ph.D. at Michigan State University, entirely focused on ecological restoration. Over 10 years later, I’m still working on the Nachusa Grasslands project. We’ve found more than 250 species of bees on the Nachusa lands, and we’ve discovered that recreated grasslands continue to increase bee diversity more than 20 years after restoration.

Along with other ecologist collaborators, our group has also found that prescribed burning and the reintroduction of large grazers such as bison can help support diverse communities of animals including birds, reptiles, beetles, bees and rodents in complex and important ways. For example, recently burned restorations show higher abundances of small mammals and contain significantly higher percentages of ground-nesting bees than unburned sites.

For thriving native prairies to exist in the future, we will need more protected lands like the Nachusa Grasslands, where passionate people work to restore and safeguard grassland plants and animals. This same thinking and work can be applied all over the globe, including Central Texas, the home of the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center.

This is my dream — to bring widespread appreciation of the unique beauty and value of grasslands to students and the public, and to inspire conservation efforts where I live and across the globe.

Dr. Sean Griffin was the 2023 recipient of the Robert and Patricia Anderson Outstanding Contribution to Science at Nachusa Grasslands Award from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands, a non-profit group founded by volunteers to support research and management at Nachusa.

| 11

The endangered rusty patch bumblebee (Bombus affinis) visiting flowers at Nachusa PHOTO Josh Klostermann; Mason bee (Osmia sp.) foraging for nectar PHOTO Dee Hudson at The Nature Conservancy

City on a Mission

Quick thinking and fast legwork made Mayor Hardberger’s environmental vision a reality for San Antonio

by Scott Simons

ONE PERSON CAN MAKE A POWERFUL IMPACT ON THE WORLD AND IN THEIR community. That’s certainly been true for our founder, Lady Bird Johnson — and it’s proving to be true for Phil Hardberger.

Hardberger, a former Air Force Pilot and retired Chief Justice Fourth Court of Appeals who served two terms as Mayor of San Antonio and served in the Office of Economic Opportunity under President Lyndon Johnson, personally steered the innovative urban escape now known as Phil Hardberger Park into existence. Spanning 330 protected acres and over seven miles of trails, the park sits only 14 miles from downtown San Antonio and serves the seventh-largest city in the United States.

The fact that the park is new seems like a miracle, considering it is almost completely surrounded by development. And the fact that it was named in Hardberger’s honor is well-de -

served, because creating new park spaces for San Antonio was part of his mayoral vision from the start.

“Phil Hardberger was concerned that the development of San Antonio was outpacing preservation of greenspaces,” said Teresa Shumaker, Associate Director of the Phil Hardberger Park Conservancy. “When he became Mayor of San Antonio, he began looking for opportunities to set aside new park spaces.”

In his first term, Hardberger encountered a defining moment and had to act incredibly quickly.

“I got the call that the Voelcker Dairy Farm was coming up for sale, and I went out that very

12 | WILDFLOWER URBAN Growth

The land bridge at Phil Hardberger Park provides wildlife and visitors with a safe passage over busy Wurzbach Parkway in San Antonio. PHOTO

Justin Moore Airborne Aerial Photography

afternoon to see the land, and I knew this was the place for the next great park in San Antonio,” said Hardberger. “To think it was an untouched property in the middle of San Antonio.

I returned to the office and asked our City Manager, Sheryl Sculley if we could afford the land. She said she would look into it. By the next morning, she came into the office, grinning, saying we could. After that, we moved at light speed, and the land was secured.”

In a positive twist of fate, the land was owned by a private family fund dedicated to medical research in San Antonio, so the money spent on the land was reinvested back into the community. And, city residents have rallied to support the completion of the park and are embracing it.

“One of the biggest surprises has been the park’s popularity and how much people value

it”, said Hardberger. “In the first week of its opening, the park had between 500 to 700 people come through per day. Now, the park averages 2,000 visitors per day.”

As the park was being developed, staff and hundreds of volunteers restored a 13-acre historic savanna, created a wetland that filters stormwater from neighboring developments, restored a field that was once a maintenance yard and established five pollinator gardens. Additionally, the park created space for two Texas Master Naturalist projects, a Native Plant Wildscape Demonstration Garden in partnership with the San Antonio Area River Foundation and Texas Parks and Wildlife, and a Butterfly Learning Center that features rare, pollinator-friendly plants.

The Alamo Area Texas Master Naturalists

| 13

Phil Hardberger Park welcomes about 2,000 visitors per day. PHOTO

Teresa Shumaker

and Native Plant Society lead native plant walks in the park several times a year, with each walk having a different focus, such as trees, native grasses or wildflowers, to create an educational arm of the park experience.

But the thing that’s driven the most buzz around Hardberger Park is its land bridge which transports both wildlife and people and is the first of its kind in the United States. It connects two sections of the park that are divided by Wurzbach Parkway, providing a safe passage for wildlife (and park visitors) from

one side to the other. The bridge, at 150 feet wide at the top and 165 feet wide at the base, allows a vast expanse for wildlife to travel safely without fear of traffic.

“The Robert L.B. Tobin Land Bridge is the park’s most popular feature,” said Shumaker. “As part of an ongoing study, the Park Naturalists have set up trap cameras along the Land Bridge to document its use by wildlife. We are very excited to report that within the first year of its opening, the trap cameras photographed every mammal species known to reside in the park. Those species are the Virginia opossum, cottontail rabbit, white-tailed deer, striped skunk, ringtail, northern raccoon, rock squirrel, Eastern fox squirrel, coyote, gray fox, and bobcat. From our cameras, the park naturalists have learned there are breeding pairs of gray foxes and bobcats in the park. Additionally, they have images of what some of those species prefer to eat. It has been very exciting, and we cannot wait to see what else we learn in this study.”

Additionally, the Children’s Nature Play Area, on the NW Military Highway side of the park, is where children can get off the trail and get their hands dirty. This area was built to eliminate barriers to the natural landscape, allowing urban children the opportunity to interact with nature in more meaningful ways, whether through climbing trees and large fallen logs or building teepees and other structures with branches set aside for just this purpose.

“Another very popular park area is Phil’s Tree. This giant Heritage Live Oak tree, estimated to be almost 400 years old, provides a serene and reflective space. On a field trip with a school from an underserved part of town, two teachers held back after the group left the tree. One was crying; both were praying. They said they felt a spiritual significance at that tree. They shared that they hesitated to come to the park on that particular day, due to the heat and logistics. But after being in the presence of that tree and seeing the park, they better understood the significance of getting out into nature.”

And that’s why parks, wild preserves and botanic gardens exist: to eliminate barriers and allow people to connect with nature in powerful – and even transformative – ways.

“Phil Hardberger Park is a beautiful and nurturing place with an inspiring story,” said Lee Clippard, Executive Director of the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, “and the park is another example of how Lady Bird Johnson’s vision for a more beautiful, more naturefocused America is becoming a reality.”

14 | WILDFLOWER

TOP Phil’s Tree is a visitor favorite. PHOTO Brad DiBaggio BOTTOM Children’s Nature Play Area

PHOTO Justin Moore Airborne Aerial Photography

Sunset Palette

by Dyhanara Rios

In the heart of Texas, when autumn unfurls, A vibrant dance of colors brightly twirls. Trees burst with pride against the azure sky, Changing colors to bid summer goodbye.

The warmest tones paint lavish leaves, Whispering secrets on the gentle breeze. Amidst the rustling limbs, a cooling song; Nature’s transition is gorgeous and strong.

Cedar elms stand tall with golden grace; We find solace in this enchanted space.

Flameleaf sumac, ablaze with scarlet hue; Fiery branches sparkling with morning dew.

Red, orange, and yellow, a harmonious blend, The fall’s natural wonder knows no end.

A painted scene with a magical spell, We celebrate this season’s vibrant swell.

| 15 PEN & Petal

Deck the Halls

A quick guide to native winter “berries.”

by Elizabeth Standley

Illustrations by Lisa

Spangler

CONFESSION: ONLY ONE OF THESE IS a true berry. Most are single-seeded drupes (not to be confused with dupes). But regardless of their technical classification, these berry-look-alikes are decidedly festive. Want to harvest some for a holiday wreath or dinner party centerpiece? This quick guide has you covered.

POSSUMHAW

Ilex decidua

15 to 30 foot tree with twiggy branches

Bunches of tiny, white flowers bloom March – May

Bright red drupes attract opossums, raccoons, songbirds and more

Telltale trait: Unlike yaupon holly, possumhaw is deciduous. Leaves shed every winter

YAUPON HOLLY

Ilex vomitoria

Single or multi trunked shrub. Rarely taller than 25 feet

Mottled gray and white bark

Females produce an abundance of somewhat translucent red drupes

Telltale trait: Dark, 1 ½ inch evergreen leaves

ASHE JUNIPER

Juniperus ashei

Aromatic, evergreen tree. Rarely taller than 30 feet

Branches start low to the ground and radiate upwards, giving the illusion of multiple trunks

Females produce tiny blueberry-esque cones

Telltale trait: Due to an abundance of pollen, male

MISTLETOE Phoradendron tomentosum

Parasitic shrub. Absorbs water and nutrients from trees via root-like haustoria

Leathery leaves that taper evenly at base and apex

Females produce shiny, white berries; males produce greenish-yellow flowers

Telltale trait: Often grows on sugar hackberry (Celtis laevigata), cedar elm (Ulmus crassifolia), and honey mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa)

CORALBERRY

Symphoricarpos orbiculatus

4 to 6 foot shrub often found in post oak (Quercus stellata) woodlands

Mature plants have shredded bark and purplish branchlets

Pale green flowers bloom April - Sept. Clusters of fuchsiacolored drupes linger all winter long

Telltale trait: Tiny hairs — visibly only by magnifying lens — cover branchlets

FIELD Guide

The Houston toad belts one out.

PHOTO Houston Zoo

The Houston toad belts one out.

PHOTO Houston Zoo

KEEPING THE HOUSTON TOAD SINGING

How one Texas vocalist is being brought back from the brink

by Asher Elbein

| 19

IN EARLY SUMMER, A POND OUT ON THE

Griffith League Scout Ranch in Bastrop begins to sing. The high-pitched trill pulses in the air like a jackhammer, rolling out from the muddy shoreline and through the rustling pines: the song of courting Houston toads ( Anaxyrus houstonensis).

Toads — particularly the adaptable, hardy Gulf Coast toad ( Bufo valliceps) — are a common sight throughout much of central and eastern Texas. But the Houston toad is something special. Small, with mottled colors and a perpetually befuddled stare, the warty amphibian is an ice-age relic, isolated from its nearest relatives by the dance of glaciers during the Pleistocene. They’re fond of sandy soil, the shade of pine canopies and grassy meadows. “They’re truly a Texas native, which few of us can say,” said Stan Mays, curator of herpetology and etymology at the Houston Zoo.

Once, Houston toads numbered in the tens of thousands across east-central Texas, breeding in ephemeral pools from the coastal prairies of Houston to the forests of College Station. Today, only a few thousand toads are found in Bastrop and Robinson

counties. In the depths of Bastrop County’s pine forests, however, a coalition of zoos, federal and state organizations have teamed up to keep one of Texas’ most notable amphibians from extinction.

OUT OF THE SPOTLIGHT

The causes of the Houston toads’ decline are varied, but many share the same root: development. The growth of the Houston metroplex devoured the sandy coastal prairies that the toad preferred, flooding it in seas of asphalt. None have been seen in its namesake city for half a century: the pond where the species was first scientifically described now sits under a parking lot outside the Bass Pro Shop in Katy Mills Mall. Roads carved up the central Texas prairies, and housing developments chewed at the loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) forests. Continuous livestock grazing, the suppression of fires,

20 | WILDFLOWER

| 21

TOP Entrance to the Griffith League Scout Ranch PHOTO Texas State University, BOTTOM Preservationists at work

PHOTO Houston Zoo

the invasion of sod grasses and fire ants, and long-running droughts — all took their toll.

Even changes that are generally helpful for amphibians — such as the introduction of stock tanks into the dry plains around Central Texas — dealt the Houston toads a blow, Mays said. Traditionally, the species gathered en masse at a few ephemeral ponds, resulting in a dense population of amorous toads and higher mating chances. As permanent artificial ponds spread over the landscape, Mays said, males scattered: “Instead of a hundred males at one pond, you’d have five here, three there, two over there.” Breeding success dropped.

“It’s the death of a thousand cuts,” said Mike Forstner, a Texas State University professor and toad researcher. “Small losses add to habitat fragmentation, and in the end, occupied patches shrink again and again.” By 1970, this complex mixture of threats had led the Houston toad to a dubious honor: the first amphibian to be listed as an endangered species.

But the federal listing didn’t help much, Forstner said, in part because the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service doesn’t consistently enforce laws preventing habitat destruction. “Legal thresholds appear to require dead toads,” he said, “and that’s a hard thing to find under a Walmart-size pile of bulldozed trees… ultimately, its not just nature that bats last, it’s the toad.”

In 1981, the Houston Zoo took a first stab at setting up a grant-funded breeding program. It was a rocky effort at first, Mays said. “We had to learn everything about them. Things that work great for Gulf Coast or American toads don’t work for Houston toads: It took us about three to four years to figure out how to breed them.” The zoo did eventually get the hang of it, he said, releasing 65 adults and 401,000 egg strands at the Attwater Prairie Chicken National Wildlife Refuge. Not long afterward, choruses of amorous toads were heard on the refuge, Forstner recalled. But by 1988, there was no grant money left either to survey for toads — or breed them.

The following decades were not kind to the Houston toad. The number of adults in Bastrop State Park dropped dramatically throughout the 1990s: the choruses grew fainter and fainter with every breeding season. Worse was to come. In 2011, a devastating wildfire raged through Bastrop County. Ideally, toads burrow deep into the sand to escape periodic fires. But decades of fire suppression had led to a catastrophic buildup of organic material in the soil: in the resulting inferno, the ground and pines burned, cooking toads and wiping out the canopies they depended on.

It was a devastating blow for the species. But in 2007, the Houston Zoo restarted its toad breeding program in an effort to insure against a future irreversible disaster. Within a few years, they and their partners in the Houston Toad Recovery Program — the Dallas and Fort Worth Zoos, Texas State University, US Fish and Wildlife, and Texas Parks and Wildlife, as well as private landowners and the Boy Scouts of America — would be hard at work bringing the toads back.

MAKING A COMEBACK

The Houston Zoo’s toad factory sits in two separate sheds on the backlot of the property, in a trio of concrete-floored rooms that hold 600 adult toads. They sit in glass and plastic tanks, with filtered water on one end and damp sphagnum moss banks on the other, fat, blinking little amphibians in various shades of mottled brown and green. In one row of tanks, newly metamorphosed toadlets float with tiny, seemingly disapproving faces pressed up against the glass.

The rooms are the domain of Matt Lammers, the Houston Zoo’s toad keeper, and both he and Mays — clad in blue disposable booties to avoid tracking in contaminants — point out

22 | WILDFLOWER

A sign at Lost Pines lets visitors know a recovery is in process. PHOTO

Lost Pines Yaupon Tea

the finer features of breeding the beleaguered amphibians. The toads in each enclosure are siblings, a measure intended to prevent breeding and keep the genetic lines clear. Even with the rooms kept at a cool, toad-comfortable temperature, however, the toads have some sense of what’s occurring outside: when weather fronts move through in January and February, the drop in barometric pressure prompts the males to begin chorusing. The resulting din can be “deafening” Lammers says: a high, hammering trill of sound. “It can get so loud that you have to take little breaks.”

The recovery program’s teams quickly learned that releasing adults didn’t work: toads kept in captivity grow comfortable around people and start seeing larger animals as potential sources of food. “You release them, they see a racoon,” Mays said. “They hop, hop, hop over — lunch.” Instead, from February to May, Texas State University biologists take the majority of the captive colo -

nies’ gelatinous eggs out into the ponds on the Boy Scouts’ Griffith League Ranch, where the tadpoles can emerge and grow in the wild.

This approach can also be tricky, Lammers said. In better days, the Houston toad relied on seasonal ponds that evaporated long before egg-gobbling fish could find their way into them. The permanent ponds on the Griffiths League Ranch — shallow, muddy-banked waters abounding with fish and snakes — are a necessary evil. When releasing eggs, they run fish bait buckets across the ponds on long guidewires, with mesh walls that permit the passage of tadpoles while keeping predators out.

In 2013, the Houston Zoo placed the first round of 36,000 toad eggs on the ranch. The aftermath of the Bastrop Fires had been brutal: in the period from 2013 to 2015, no toads were heard calling at the ponds. But by 2018, Mays said, the combined breeding programs were releasing around a million eggs a year.

| 23

A toad in the hand, pictured at the Houston Zoo’s toad factory.

PHOTO Houston Zoo

Slowly, the toad numbers began to rebound, and the trilling of males began ringing out further from the release site.

This year’s breeding season has been particularly good, Mays said, with 1.28 million eggs released, and field crews counting over a hundred calling toads in the muddy ponds. By the month of May, he said, the release sites were hopping with so many tiny toadlets that field crews couldn’t enter them. And as those numbers grow, the population’s health is actually improving. Houston toads compete for insects with the more common Gulf Coast toads. But since the endangered amphibians breed earlier,

“ We have averted a second catastrophe,” Forstner said.

“A lot of people doing a lot of things have enabled a success story for Bastrop County since 2011.”

Lammers said, their babies can actually devour the majority of available insect prey before the Gulf Coast toads emerge, pushing out their competitors and giving themselves some breathing room.

“We have averted a second catastrophe,” Forstner said. “A lot of people doing a lot of things have enabled a success story for Bastrop County since 2011.”

But while the toad populations are booming compared to the bad years after the wildfire, Lammers said, there’s still a lot of room for populations on the ground to grow. As they do, the toads are likely to migrate out in search of new habitat — which will help the recovery program figure out where to begin other rounds of egg releases. “The idea is to establish Bastrop County as the hub of the wheel,” Mays said, and reinforce new breeding grounds as the toads establish them. “The toads will tell us where we need to go next.”

Nonetheless, the recovery program is taking some steps to give the toads as much room to move as possible. The new plan calls for three different ten-thousand-acre preserves, all as closely connected as possible. That way, toads from the Griffith League property will be able to disperse, first out onto the 6,600-acre Bastrop State Park and then to future preserved lands. Once toads start showing up in greater

24 | WILDFLOWER

TOP A Houston toad tadpole PHOTO Dallas Zoo, BOTTOM Toad eggs in suspension PHOTO Houston Zoo

numbers in other counties, Mays said, other zoos in the program will ideally stop releasing at Griffith League Ranch and begin bolstering populations closer to home.

Much of this is going to depend on the goodwill of landowners, Mays noted, who haven’t always been thrilled about the project. Some fear that getting involved in toad conservation will lead to government entities coming in and telling them how to run their land. (One property adjacent to the Griffith League Ranch — whom Lammers declined to name — told the program’s field representatives they wanted nothing to do with it.) But others are more enthusiastic about the idea of toads returning to their land. Texas State, UFWS and TPWD are in the process of refining the current landowner agreements, and discussing the possibility of offering agricultural exemptions for property holders who keep their tracts toad-friendly.

“Native vegetation, habitat stewardship,

more pollinators — just the appreciation of our Texas landscapes — is all net good for the toad,” Forstner said. Managing for Houston toads is also key to managing for game animals like deer and turkey, or for healthy woodland. “It’s not a risk: it’s a way to get federal and state assistance to make your lands healthier, more fire resilient, and better habitat for wildlife.”

“Once you explain to people what you’re doing, the tone usually changes,” Lammers said. “All the folks I’ve encountered out there moved out there so they could live in the woods, and they like frogs. Everyone’s on the same page, it’s just clearing red tape.”

For now, the mission to make more toads continues. In the Houston Zoo’s toad factory, Lammers handles a startlingly round female toad, her belly full of eggs. Across the way, plastic tanks throng with floating hatchlings awaiting release — and the chance to keep Bastrop County’s pine forests singing.

| 25

The endangered Houston toad in the wild

PHOTO Houston Zoo

The Draw of Nature

How the act of creating

fosters community

by Carrie McDonald

Photos by Ann Alva Wieding

Candace sketches in the Theme Gardens.

| 27

I’ve worked at the Wildflower Center since 2005 and over the last year, I’ve looked forward to coming in on Wednesday mornings especially. Often, I see a certain group gathered either in the Café or around our display of seasonal plant specimens, sketching and sharing drawings. Over time, I have become their unofficial plant tutor and staff liaison. They show me their work. “Spiderwort?” I ask. “It is!” someone answers. “Is this one firewheel? Is this the stamen?” A chorus of delight and “yeses” erupts. And on we go. Part of the reason this is so fun is because many members of this group are novice artists, and if they have captured a petal or berry with enough accuracy that I can identify the subject, it means their technique is improving. They call themselves the Botanical Buds.

28 | WILDFLOWER

| 29

LEFT TO RIGHT Katie Lydeck, Candace Vorhaus, Ann Marie Terzian, Stella Harper, Kim Freels, Tina Ritterhoff and Shannon McClenny

Origin Story

In the fall of 2021, the Center hosted a class on botanical illustration with local illustrator Clair Gaston. As the class concluded, a handful of participants exchanged numbers and a few were inspired to continue painting together. This is how the Botanical Buds were born.

Botanical Bud Ann recalls that one of her favorite things about the illustration class was how Gaston would lead the group on nature walks to find specimens, then guide them through the drawing or painting process, even in the rain. Another member of the group, Stella, says that examining the stems and leaves of flowers or the way groupings of plants grow together and intermingle prompted her to think differently about shape, shade, texture and tone.

Meanwhile, Botanical Bud Rachel says, “I’m probably the one who knows the least about plants.” She signed up for the botanical illustration class because her mother-in-law “is big into gardening and she asked me to draw her some flowers. I had no idea how, so I took the class. My final project, a daylily, is now hanging on her wall.”

Ann Marie is known as one of the Botanical Bud’s bird photographers and native plant

connoisseurs, along with Tina, who was already a self-proclaimed “obsessed gardener” with many native plants in her own yard. “Between the Wildflower Center, Austin Community College and Central Texas Gardener, I’ve learned a lot about the wonderful plants we have in this region,” she says. “Our ecoregion is unlike anywhere else in the world and the Wildflower Center showcases our natural beauty. In times of climate change, our native plants teach us what is truly resilient.”

Finding a Rhythm

The Botanical Buds enjoy weekly walks along different gardens and paths, pausing to inspect and identify particular plants that catch their attention.

With the Center as homebase, they explore venues throughout Austin and continue to give themselves new challenges like felting and non-dominant hand drawing. The group has added a new exercise this year and is creating art inspired by celebrated poet Mary Oliver, such as this line, describing a swan:

Did you see it in the morning, rising into the silvery air — An armful of white blossoms

30 | WILDFLOWER

Stella Harper at her plein air easel, painting firewheel

The group includes retired people and working people. It includes a mosaic tile artist and baker, a ballet student, an illustrator, a hair stylist, an architect and designer, and a Ph.D. of science and geology, resulting in an interesting mix of experiences, viewpoints and approaches. Finding new and unique things around every corner creates a new challenge for them each week. While their subject matter has grown to include birds, fruit and even longhorns, a deepening engagement and love of nature has been growing within each of them too.

Feeling the Impact

In February 2022, Stella experienced a healing moment at the Center that involved the maximilian sunflower ( Helianthus maximiliani ), a yellow fall bloomer in the Aster family, reaching 10 feet tall and growing throughout the central plains from Texas up into Canada. As the Botanical Buds strolled out into the Savanna Meadow, looking for their challenge that week, everything around them was in winter shades of gray, tan and brown. A stalky stand of golden-brown remnants — remnants of something that was once green — caught their eyes. They unfolded their chairs to study and sketch. You see,

in February, after the fall flowers of the maximilian sunflower have done their job of attracting butterflies for pollination, the small seed heads form. These seeds are an important food source for lesser goldfinches that land on the tops of the tall swaying stalks and pick the seeds out. It was a transformative moment for Stella, whose mother had recently passed, as she witnessed and acknowledged the beauty and reassurance in the cycles of life and death. Several members of

| 31

TOP Tina Ritterhoff (left) and Ann Marie BOTTOM Katie with her plein air paint box, painting cacti

the group submit art to various shows around Central Texas. One show in particular focuses on happiness and mental health, and Stella will be submitting one of her paintings of maximilian sunflowers.

In the winter of 2020, Botanical Bud Candace made a new year’s resolution to learn watercolor painting. She was a novice artist entering the botanical illustration class and over the course of that next year she began making her own handmade watercolor paints from natural pigments and sharing them with her fellow painters. She determined that hand-made paints allowed the group to better capture the colors of our native plant subjects. She recently completed an educator’s nature journaling workshop taught by John Muir Laws. The journaling starts with observation, taking the participants through a mindfulness exercise about nature stewardship, asking questions, and slowing down. Their art becomes the output of their observation as they ask themselves, “What’s the weather like as I observe this plant? Which direction is the wind coming from? How hot is it today? What are the companion plants nearby?” Candace was inspired to take what she learned and continue her journey in education. She is now teaching children watercolor painting.

Fulfilling a Mission

Over time, I began to see something emerging in this group; something every conservation organization works to foster: community, inspiration, and a better understanding of nature and our interconnectedness with it. The painters became members of the Center. They started installing carloads of plants from our plant sales in their home gardens. They continue to return to the Center because — as members, volunteers and staff always point out — the place is new and different every day, season to season. Each spring reveals surprises. All summers hold promises. Every fall reveals new colors. All winters offer different textures.

So many aspects of our lives demand speed, but studying a petal with the intention of drawing it encourages us to slow down and take in the details. Is its edge smooth or slightly toothed? Does its surface shine, or are there tiny hairs there? The practice of drawing asks that artists sharpen their looking skills.

At the Center, we’re always thinking about how to make inroads with more people; to

provide an experience where visitors can come to fully appreciate and celebrate the natural world and their place in it. We care for these landscapes and make inspiring gardens and we set the stage. However, as Robin Wall Kimmerer writes, “The land is the real teacher. All we need as students is mindfulness.”

Taking a class can be like planting a seed, and just like in a garden, a collection of individuals has grown into a community. The Botanical Buds have bloomed, their art has evolved and their friendships have flourished. Their curiosity about our planet has intensified and deepened. And isn’t that what the Center’s mission is all about?

I love the opportunity to see our landscapes at the Center through different perspectives. I sometimes look over the Botanical Buds’ shoulders as they paint. What a delight it is to look from canvas to meadow and back as they draw and paint and things come to life on paper or canvas. My eye might be drawn to a foreground of coneflowers edging a June meadow, where their skills capture the scene in abstract swaths of summery purples.

And so, in the end, an art class can be much more than an art class. Like Marcel Proust suggested, “the real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.”

32 | WILDFLOWER

Wildflower Center’s Observation Tower by Katie Lydeck

| 33

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT Rachel with next gen Buds

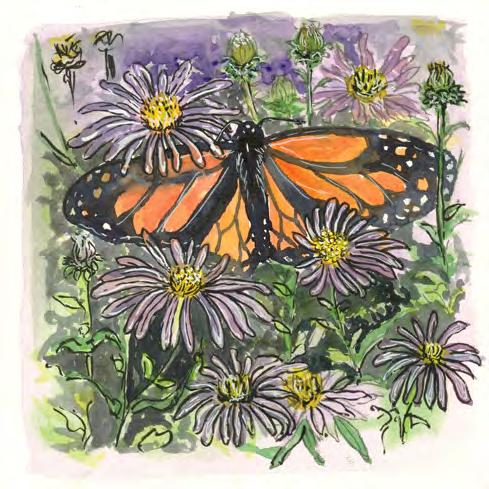

PHOTO Ann Alva Wieding, Mexican tulip poppy (Hunnemannia fumariifolia) by Candace Vorhaus, twistleaf yucca (Yucca rupicola) bloom by Kim Freels, golden grounsel (Packera obovata) by Debbie Conyers, monarch with fall aster (Symphyotrichum oblongifolium) by Katie Lydeck

The latest on our gardens and our work

by Emily Engelbart

POSITIVE DISTURBANCES

THIS YEAR, RESEARCHERS FROM the Wildflower Center joined DRAGNet and Drought-Net — two global networks with hundreds of sites around the globe — in order to more deeply and comprehensively understand ecological disturbances and how they impact plant growth. Led by Dr. Sean Griffin, Director of Science and Conservation at the Center, and Dr. Amy Wolfe, Assistant Professor in the Department of Integrative Biology at The University of Texas at Austin, the project employs standardized methods to examine the effects of drought and land-clearing on plant communities.

Global networks like these allow sites around the world to coordinate their methods and compare their results.

The Center’s Land Steward, Dick Davis, and Director of Land Resources, Matt O’Toole, used chainsaws and herbicide to remove trees from across the site. They then used a tractor to clear subsets of the plots themselves to allow for disturbance treatments, removing roots and other plant material. This clearing process took months. Griffin and his team established five meter by five meter plots in this more remote area of the Wildflower Center grounds.

34 | WILDFLOWER

CENTERED: News and Updates

“The goal is to have the starting, baseline conditions of the plots as standardized as possible,” Griffin said.

The team then constructed covers to prevent rain from reaching 66% of the plot ground, simulating extreme drought. “It’s doing multiple things that drought events do, which is reducing the rainfall as well as increasing heat and evaporation,” Griffin says. Griffin and his team, in addition to UT students and interns, have been conducting plant monitoring and soil coring (for nutrient analysis) of these newly grown plots in order to understand changes

in the biological communities.

Between the two networks, the scientists are employing 14 treatment methods throughout the 84 plots. “We’re not just examining the effects of drought or disturbance, we are also observing the effects of drought on disturbance,” Griffin says. In a time where ecological disturbances are increasing in prevalence, the data gathered from these projects will allow scientists around the world to understand the harmful effects, and potentially develop mitigation or combative strategies.

| 35 PHOTOS Sean Griffin

A BLOOMING REOPENING

IN AN ONGOING EFFORT to extend the reach of the Wildflower Center’s mission of inspiring the conservation of native plants, Center horticulturists have partnered with staff at The University of Texas at Austin’s Texas Science and Natural History Museum (formerly known as the Texas Memorial Museum) to create a new garden that enhances the exterior of the museum, which is slated to reopen this September. The garden’s native plants and pollinators complement the museum’s themes of natural history, like biology and entomology.

Our Director of Horticulture, Andrea DeLongAmaya, says she and a committee initiated plans with the museum in late 2022 to create a pollinator garden. At the time, the exterior was mostly dirt and weeds, so their goal was to create something appealing for visitors that would also provide a healthy habitat for pollinators.

“Everything is native to Texas, most are locally native, so it’s intended to help people connect with our natural world,” DeLong-Amaya says.

They introduced a variety of plants like the Engelmann daisy (Engelmannia peristenia), large buttercup (Ranunculus macranthus) and cenizo (Leucophyllum frutescens), all of which typically attract bees and butterflies. Plants like flame acanthus (Anisacanthus quadrifidus var. wrightii ) attract birds, in addition to bees and butterflies.

Rather than only introducing flowers that bloom during the spring, DeLong-Amaya says they practiced timesharing (see page 46), which will produce a beautiful array of colors and benefit pollinators throughout different seasons of the year.

“I think that’s really important for sustaining pollinators: to give them a food source as much of the year as possible,” DeLong-Amaya says.

With help from UT students and Landscape Services staff, the complete garden facilitates an inviting atmosphere for museum visitors.

The Texas Science and Natural History Museum is supported by a grant from the UT Green Fund for the Pollinator Garden.

Carolyn Connerat 36 | WILDFLOWER

PHOTO

FORGIVE US IF WE’RE BECOMING FERNATICAL

FERNS FIRST APPEARED on our planet

more than 300 million years ago, and since November 2022, the Wildflower Center has been on a mission to collect the 100+ varieties that are native to Texas. Susan Tracy, a self-proclaimed “fern-atic,” initially donated 16 Texas ferns to the Center, as well as monetary donations for us to expand this “Texas Fernery” project.

“Susan is so excited to be able to work with the Wildflower Center and help bring awareness and education to our young, modest collection of ferns,” Stephanie Del Toro, Assistant Director of Development says.

Prior to the project, a few ferns existed in the gardens, but now we can showcase a greater variety of unique ferns with native ranges spanning from east to west Texas. The Center’s Margaret & Eugene McDermott Learning Center, a restored 19th century carriage house, is now home to the Texas Fernery where visitors can look back in time at these plants predating dinosaurs.

To expand the collection, a team from the Center, including Horticulturist Jay Caddel, will continue collecting ferns from around Texas. The ferns’ native habitats will dictate how the team cares for them. Ferns from east Texas require more moisture, while the dryness of west Texas means ferns from that region thrive with less water.

“It’s just about learning the specific needs of each fern,” Caddel says.

The current collection holds the southern maidenhair fern ( Adiantum capillus-veneris), Copeland’s cloakfern (Notholaena copelandii ), and the ovateleaf cliffbrake (Pellaea ovata), among other species.

These nonflowering vascular plants, differ in some ways from the wildflowers at the Center. Ferns reproduce by spores, in contrast to flowering plants which produce seeds after pollination. Both ferns and flowers do, however, sport roots, stems and leaves.

“Ferns don’t flower, they produce spores,” Del Toro says. “I think the fern is underappreciated.”

GIFTS OF NOTE

The Wildflower Center would like to acknowledge these generous gifts and their donors:

Josie Knight

$25,000

Bartlett Tree Experts

$35,000 to support Fortlandia, Luminations, Texas Arbor Day and tree services

Estate of Hester Currens

$45,000

Kim Peoples and Kevin Bacon

$50,000 to support plant collections

PHOTO Joanna Wojtkowiak | 37

CENTERED: Things We Love

PODCAST

Lady Bird

There is no doubt that our namesake, Claudia Alta “Lady Bird” Johnson, was an extraordinary woman with an inspiring life story. This past June, The Drag Audio Production House released a podcast detailing Mrs. Johnson’s journey from growing up in a tiny East Texas town to becoming one of the nation’s most influential first ladies. Working closely with the LBJ Presidential Library, the producers were able to access historic audio files of Mrs. Johnson detailing her life story in her own words. In addition to this pre-existing media, they interviewed many individuals that had been close with Mrs. Johnson throughout her life. This research took them on many adventures, from Washington D.C. and the LBJ Ranch to East Texas where Mrs. Johnson grew up.

While the podcast touches on aspects of Mrs. Johnson’s personal life, the inspiration that drove its creation was her relentless commitment to both people and nature. Throughout her reign as first lady, she continuously prioritized environmentalism and conservation. Over the years, these passions led her to establish many projects that centralized her environmental commitment. Thanks to Mrs. Johnson, we have been given the opportunity to inspire the conservation of native plants worldwide.

Consisting of 12 full episodes and additional bonus episodes, you can find “Lady Bird” on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all other major podcasting platforms thedragaudio.com/introducing-lady-bird

BOOK

The Secret Garden

SUNSCREEN Supergoop!

Texas sun is not to be underestimated, especially in the summertime. In order to protect ourselves from those UV rays, finding a reliable sunscreen is essential. Holly Thaggard, founder of Supergoop! sunscreen, felt the same. Back in 2005, Thaggard founded Supergoop! with the goal of bringing accessible SPF pumps into Texas and Louisiana schools. She continues this work to this day through Ounce By Ounce, Supergoop!’s giving program that donates SPF to schools and communities across America. Supergoop! is my sunscreen of choice because it is lightweight and blends effortlessly into the skin. Unlike most other sunscreens, Supergoop! doesn’t leave the dreaded white cast which makes it accessible for all skin textures and tones. They have a wide variety of products, ranging from the standard body lotions to clear or tinted facial SPFs. The brand is also cruelty free and made with clean ingredients, which is always an important factor I look for in the products I use.

April Briggs

Marketing & Communications Associate supergoop.com

“The Secret Garden” by Frances Hodgson Burnett is a charming coming-of-age story about a sour and spoiled orphan girl who is sent to live in the countryside with her estranged family. After discovering a hidden garden, she finds strength and kindness within herself as she restores the garden and connects with nature. Written in 1911, this classic children’s tale is enjoyable for readers of all levels. I have read this book multiple times and have always thoroughly enjoyed it, from when I was Mary’s age to now in my mid-twenties. I recently read it this spring, and the story was so endearing, I found myself spending more time outside because of it. The importance of connecting with nature and putting love into the Earth is the major theme of this story, and I recommend it to everyone that loves plants!” Audrey Donovan Guest Services Coordinator

38 | WILDFLOWER

The tools, books and media we’re currently into by Wildflower Center Staff

PHOTO

LBJ

Library photo by Frank Wolfe

| 39

CENTERED: Thank You to Our Corporate Partners

Capital Printing

Austin Wood Recycling | Cosmic Coffee + Beer Garden

Desert Door Distillery | Energy Renewal Partners | Glide

Texas Coffee Traders | ThermoFisher Scientific

40 | WILDFLOWER Plant People

Diversity in Nature

Growing gardens and fostering community online

by Dyhanara Rios

photos by Ann Alva Wieding

DRIVING

THROUGH AUSTIN’S HISTORIC, DIVERSE EAST

side neighborhood , I scanned the houses on the left and right. I spotted the house I was looking for right away. With a dark blue exterior and a front garden in full bloom, it was like nothing else on the block. There were towering standing cypress (Ipomopsis rubra), lanceleaf coreopsis (Coreopsis lanceolata), spires of mealy blue sage (Salvia farinacea) and other plants native to Texas that shone in the early evening light. I knew I was at the right house before I looked at the address.

Andrew Ong and Jared Goza, also known as Gays Who Garden on Instagram, walked me around their front and back garden, sharing their space with me. The garden graciously wraps around the house, boasting its bright colors and sweet scents.

How did you come up with the concept for Gays Who Garden?

Andrew Ong: We started our Instagram account, Gays Who Garden, when we moved into our new house about four years ago. At the time, there weren’t many similar accounts that we had come across. We wanted to connect with others and increase visibility for people like us who had a strong passion for plants and nature. The name “Gays Who Garden” came to us because it instantly shows our identities and what we wanted to showcase.

Jared Goza: Andrew was taking so many photos of his roses (Rosa spp .), so I suggested that he should start an Instagram account. We started the account together and we have really seen it take off. Initially, we focused on close-up shots of flowers, but recently Andrew has been creating reels and other types of content as well.

How did you initially approach the design of your garden spaces?

JG: When we first started, our approach was to discuss the plants we liked and find suitable spots for them in the garden. We had a blank canvas, as our property had a lot of concrete and very few trees. So, our first major project was removing all that cement and creating space for plants. Once we cleared the space, we focused on planting trees like oaks (Quercus spp.), magnolias (Magnolia spp.), and redbuds (Cercis spp.). The only existing tree was a pecan tree (Carya illinoinensis), which was unfortunately planted right above the gas line. It killed me

| 41

to think we’d have to take out the tree, but it would literally kill us if we didn’t. It’s important to avoid having to move trees, as we’ve had to do that a few times.

AO: If we could start this all over, we would first get our soil tested. We are fortunate to have good farm soil, being on post-sediment. We would also plan the garden around the existing bigger trees because trees can change the landscape over time due to variations in light levels.

JG: We consider factors like light, water, and soil when planning the garden. Hydro zoning, which involves grouping plants with similar water needs together, would also be part of our garden design to promote water efficiency. We also focus on incorporating different textures, fragrances, and colors to create a sensory experience in the garden. We draw inspiration from English gardening and have been influenced by visits to places like Kew Gardens in London. That’s where we had our wedding!

AO: It’s important to start small and find your passion first. There are many times where you’ll think to yourself “burn it down to the ground,” or get frustrated and think, I don’t want to do this anymore. Find that one

thing that pulls you back into the garden. For me, it’s the roses and ornamentals.

Do you prefer to buy your plants, grow them from seed, or a mix of both?

JG: Growing plants from seed has been a significant change in our gardening approach. For us, our rule is, if a plant will take more than a year to reach adulthood, it’s better to buy it. However, almost everything else can be grown from seed, and it’s a cost-effective and rewarding way to fill in the garden.

AO: Our front yard, specifically the wildflower area, was a project where we grew everything from seed over a period of two months during winter. Timing is crucial in Texas gardening, and it’s something that many people may not initially realize. Understanding when to plant certain seeds or start certain plants is essential for success. For example, a common misconception is with bluebonnets (Lupinus texensis). We’ve seen some local stores sell bluebonnet seeds in spring when people see the plants blooming. But by that time, it’s already too late to plant the seeds for that year — those seeds need to be sown in the fall.

42 | WILDFLOWER

ABOVE Andrew Ong meticulously examines the garden, looking for weeds to pull and cultivating different textures, fragrances and colors. PREVIOUS PAGE

Andrew Ong (left) and Jared Goza, smiling in front of their East Austin house, brimming with flowers.

Tell me more about the feedback you’ve gotten — both online and from neighbors.

JG: We’ve gotten a lot of great feedback from neighbors! A lot of people say they’re looking for inspiration to create something similar in their own gardens. We often emphasize that our front yard, with its abundance of flowers, is a result of consistent planting and maintenance. We encourage them to start small and gradually increase the number of plants they have. We also mention the importance of watering and understanding the specific needs of different plants.

AO: Everyone has their own vision and goals for their garden, so we try to offer advice that’s just based on our experiences. We want to encourage others to enjoy gardening and find their own unique style and approach.

JG: We did, one time, get a note from the city because one of our plants extended over the sidewalk. As our garden becomes more prominent, it reminded us that there’s increased visibility and scrutiny. We understand and accept that as part of the responsibility that comes with having a vibrant and visible garden. Native grasses

like big muhly ( Muhlenbergia lindheimeri) tend to grow tall and some people find them unwieldy.

AO: It’s rewarding to see how our garden sparks curiosity and interest in gardening among our neighbors and visitors. The only negative thing I distinctly remember was this one hate message that included, “Why are y’all doing this? Why isn’t it ‘couples who garden?’” Well, this is how we identify. If you don’t like it, I’m sorry you don’t like it. Feel free to move on. No one’s forcing you to follow us. No one’s forcing you to look at our content. We’re not shoving us in your face. We’re just existing and gardening. But most direct messages are more positive, and we get a lot of questions about our process.

JG: We’re always happy to answer questions and share our experiences. One common question we get is where we source our plants, and we always recommend local nurseries and plant sales.

AO: It’s through these connections and the sharing of knowledge that we can all grow as gardeners and individuals. It’s worth all the hard work and challenges.

A large spider web built between lemon beebalm (Monarda citriodora) and standing cypress (Ipomopsis rubra). Andrew and Jared note that many pollinators call their gardens home.

| 43

Goza enjoys growing plants from seed and refines his techniques over time. “We’re always happy to answer questions and share our experiences,” he says.

Do you see gardening as a reflection of your personalities and identities?

JG: Absolutely. Andrew is more left-brained and I’m more right-brained — I want the plants to flourish on their own, allowing them to be independent and grow into their natural beauty. I embrace the wildness and lushness of the garden. Andrew, on the other hand, has a more structured approach. He focuses on organization and creating a sense of order. Our gardening styles mirror how we work and complement each other.

AO: I think of gardeners as helpers and nurturers in the community. We invest in our garden, knowing that we’ll receive something valuable in return. Gardening has taught us resilience and the ability to bounce back from setbacks — which happens often with plants. It reflects our upbringing and the values of sacrifice and taking care of loved ones. Gardening also provides structure and routine, which benefits our mental health. It’s a reflection of who we are as individuals and our nurturing nature.

JARED & ANDREW’S TIPS FOR TEXAS GARDENERS

Get your soil tested. Resources include the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service for your county.

Start small. Find one area or one type of plant to specialize in where you can make a big impact.

Moving into a new home? Try to let the land rest and see what comes up on its own — plants that were cut back but not fully removed by previous owners may be dormant.

Visit local garden centers and demonstration gardens like the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center for inspiration and to observe what does well in your climate.

44 | WILDFLOWER

Not-So-Strange Bedfellows

Timesharing in the garden creates a year-round show

by Andrea DeLong-Amaya

Partridge pea (Chamaecrista fasciculata) and gayfeather (Liatris punctata var. mucronata) make a complementary fall combination. PHOTO Wildflower Center

ARE YOU LOOKING FOR WAYS TO SUPPLY BUTTERFLIES, bees and hummingbirds with nectar and pollen throughout the seasons? What if you could do this while maximizing beauty in your garden, saving plastic and cutting the greater carbon footprint required to continuously swap out plants?

Most gardeners face a real challenge keeping their gardens looking great for the bulk of the year. What’s one to do when the first freeze of winter renders your lush stand of wax mallow (Malvaviscus arboreus var. drummondii ) into a sad bank of black mush? Some folks reach for bedding plants to supply seasonal color, but we’re committed to Texas natives at the Wildflower Center, so bedding with pansies (Viola tricolor var. hortensis) or coleus (Coleus scutellarioides), as lovely as they are, doesn’t align with our mission. Still, guests visit throughout the year, expecting to see something pretty. We’ve had to innovate a bit when presented with this age-old gardening conundrum.

We practice timesharing, a strategy of planting two species that can share the same spot and actively grow at different times of year. In general, herbaceous plants either lie quiet in winter and grow during the warm season,

or actively grow in the cooler months and go dormant in summer. By selecting a combination of perennials or re-seeding annuals with matching cultural requirements and alternating growing seasons, we maximize the function of cultivated spaces. Benefits reach beyond the cosmetic: gaps filled with seasonal vegetation inhibit weeds, pollinators enjoy more flowers over the year, and we appreciate the reduced efforts and costs of seasonal bedding installations.

If your garden grows in cooler regions, you can still plan for a succession of flowers over the seasons with a little research on plants’ growing and dormant habits. Visit our Native Plants of North America database for more guidance at plants.wildflower.org. Finding winning combinations is all about experimentation. Mix and match to see what works best in your garden.

46 | WILDFLOWER

Can Do

PROVEN PAIRINGS FOR TEXAS AND THE SOUTH

Couple the winter-latent wax mallow with giant spiderwort featuring evergreen daylily-like foliage. Spiderwort awakens in fall, grows through the winter and flaunts copious blue, purple, cerise or white flowers in spring. Plants completely disappear around May, handing the show back to the scarletblossomed wax mallow just emerging from dormancy as temperatures rev up.

A fast-growing annual, partridge pea sports happy yellow blossoms all summer, and its open airy greenery allows enough sunlight to filter down to the scaled-back summer foliage of winecup. During winter, winecup’s deeply lobed, dark green leaves add beauty at ground level before rich magenta flowers push out to bless the spring.

Texas lantana sprouts in mid-spring, carrying the warm season with yellow and orange flowers. Cold weather knocks it down, leaving room for red-dotted primrose foliage to cover the winter ground. Pink evening primrose blossoms appear around March before the dogs days of summer and dwindling rains shut plants down, yielding back to the heat-loving lantana.

| 47

Partridge pea (Chamaecrista fasciculata)

Wax mallow (Malvaviscus arboreus var. drummondii ) Giant spiderwort (Tradescantia gigantea)

Texas lantana (Lantana urticoides)

Pink evening primrose (Oenothera speciosa)

PHOTOS Wildflower Center

Winecup (Callirhoe involucrata)

The new is launching this fall!

After over 20 years, we’re redesigning our Native Plants of North America database. You’ll enjoy easier search functionality, improved navigation and a more intuitive experience.

NONPROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID PERMIT NO. 391 AUSTIN, TX

4801 La Crosse Avenue Austin, Texas 78739

Lee Clippard Executive Director

Lee Clippard Executive Director

The Houston toad belts one out.

PHOTO Houston Zoo

The Houston toad belts one out.

PHOTO Houston Zoo