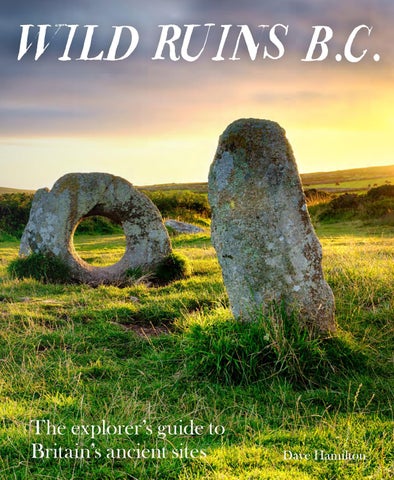

Discover Britain’s extraordinary prehistory in this handbook to

its wildest and most beautiful ancient remains. The sequel to

the best-selling Wild Ruins.

Wild Ruins B.C. reveals the extraordinary tale of Britain’s human

story before Christianity, from the first human footprints of 800,000

years ago, to ancient axe factories, rock art, stone circles, mountain

burials, sunset hill forts, lost villages and temples to the dead.