THE MAGAZINE FOR INTERNATIONAL EDUCATORS Finding Joy without Judgement Successful self-taught study kampus24.com MAGAZINE SPRING 2023 www.schoolmanagementplus.com PART OF SCHOOL MANAGEMENT plus British and International? IN PARTNERSHIP WITH In partnership with

Speech and Language Therapy training for teachers to support children in the classroom

Our courses are especially helpful for those supporting children with Special Educational Needs (SEN)

online now www.elklan.co.uk

to Support Children’s Language and Learning Book

The

ADVERTISING

Contents 28 Successful self-taught study Vanessa Walker 32 How do we teach children about the World without scaring them? Rob Ford 36 Challenges in International Assessment Louise Badham From the Schools 38 Rethinking Learning and Learning Spaces after the Pandemic Tasneem Khan 40 British and International? In today’s changing world, it is more possible than ever for schools to be both Claire Russell From the Associations 44 New Paradigm Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Leadership Angela Browne Features 4 Finding Joy without Judgement: From Goals to Values Helen Street 8 What words would YOU use to describe 2022? Elisabeth Neiada 12 Developing effective Environmental and Sustainability Education for longterm behaviour change – the changing focus of education Lauren Binnington 16 What is a concept? A brief journey from Plato’s forms to the Overton Window Paul Regan Leading, Teaching and Learning 20 Challenges Faced By Women Who Lead. Part One: Four Themes from Interviews with Women in School Leadership Kim Cofino 24 Strategic Planning for International Schools Jacobus Steyn On the Cover How do we teach children about the World without scaring them? page 32 12 Developing e ective Environmental and Sustainability Education for long-term behaviour change – the changing focus of education 28 Successful self-taught study 32 How do we teach children about the World without scaring them? THE MAGAZINE FOR INTERNATIONAL EDUCATORS EDITORS

DIRECTOR

Mary Hayden Jeff Thompson editor@is-mag.com www.is-mag.com MANAGING

& PRINT

Steve Spriggs steve@williamclarence.com DESIGN

Fellows Media Ltd

Gallery,

Southam Lane, Cheltenham GL52 3PB 01242 259241 bryony.morris@fellowsmedia.com

part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted in any form or by any means. International School is an independent magazine. The views expressed in signed articles do not necessarily represent those of the magazine. The magazine cannot accept any responsibility for products and services advertised within it. fellowsmedia est. 1992

Jacob Holmes jacob.holmes@fellowsmedia.com 01242 259249 No

Spring 2023 International School Finding Joy without Judgement Successful self-taught study MAGAZINE schoolmanagementplus plus and International? partnership Spring 2023 | International School | 3

Part of the Independent School Management Plus Group schoolmanagementplus.com

Finding Joy without Judgement: From Goals to Values

By Helen Street

A focus on values supports the development of contextual wellbeing with meaning and purpose. Moreover, the exploration of values within a classroom, living room or board room helps us to understand and pay attention to what matters, without limiting our understanding of ourselves, or of who we can become.

In part one of this two-part series (which appeared in the last issue of International School magazine), I explored the value of focusing on ‘what works well’ in any given situation; as opposed to ‘what is not working and needs changing’. Taking this strength-based approach to guiding behaviour is both energizing and encouraging. It ensures that feedback provides an opportunity to experience competency and growth.

To ensure that this strength-based approach is both meaningful and workable, the concept of a strength (ie what works well) needs to be defined in relation to the context a person is in. For example, in the midst of a class discussion having the ‘courage’ to present your ideas on stage will often be a valuable strength; whereas in the midst of a sporting event, embracing

4 | International School | Spring 2023 Features

‘perseverance’ might lead to the best experience.

Behavioural theories of depression have long suggested that we learn behaviours that are useful to us (ie act as strengths) in the context of our childhood. If we then change context, but do not alter our behaviour, the behaviours that used to be useful can become barriers to wellbeing. For example, consider a child growing up in a household where noise and chatter are not tolerated from junior family members. The child may usefully learn to sit quietly when other people are around. If the child then grows into an extremely quiet adult, this may impede them connecting easily with others. It is thus imperative that we learn fluidity and flexibility in our attitudes and behaviours, as much as we learn about how different attitudes and behaviours can work in different situations.

I believe an authentic and thriving world needs to embrace all facets of the human condition as worthy, meaningful and of great value within the right situation. As such, any of the multitude of human attitudes, feelings and behaviours can be experienced as positive or negative given the right moment in the right context, at the right time. This is true of those ways of being and behaving that are often experienced as tough and challenging. For example, anger can be a call to improve equity; grief can be an expression of immense love; anxiety can be an important call for caution.

Certainly, some of Seligman and Peterson’s identified ‘character strengths’

(2004) have been well-researched as mediators of wellbeing in western culture. For example, kindness has often been cited as a cornerstone of positive relationships, an important element of living well (see, eg, Lim et al, 2021; Anonymous, 2010). Gratitude has been significantly linked to both wellbeing (Alkozei et al, 2017) and the reduction of unwanted states such as resentment (Hammer & Brenner, 2019). Still, no-one would state that the expression of any attitude or behaviour is always beneficial or warranted in every situation, and perhaps even more importantly, it does not always represent a person’s authentic response to a context. For example, if a person is frustrated and angry within an inequitable context, this could be a strong, healthy and understandable response. Moreover, if this frustration and anger leads to that person changing or leaving the context which is unhealthy for them, then their response has also arguably been a strength at that time.

The more we categorize personality states and traits in positive and negative terms, as ‘strengths’ or weaknesses,

the more likely we are to pathologize unpleasant emotions and to limit the full complexity of human experience. This can be troubling on multiple levels. It can lead those experiencing distress, anxiety or sadness to view themselves as lesser or estranged from their communities. At its extreme, the preference given to certain ways of behaving and feeling can lead to an assumption that dysphoric states are inherently wrong. This belief may well compound distress, leading sufferers to feel bad about feeling bad (Street, in press).

I propose that a more useful, and more accurate representation of Seligman and Peterson’s character strengths would be to state that they represent some of the attitudes and behaviours that are frequently associated with wellbeing in the twenty-first century. As such, they provide a useful reference point to explore responses in any given situation. This is a very different notion to assuming each person can usefully be assessed according to their ‘top’ character strengths, that character strengths are positive traits irrespective of context, or

Spring 2023 | International School | 5 Features

We learn behaviours that are useful to us (ie act as strengths) in the context of our childhood.

that there are a definitive 24 character strengths in the world.

Rather than asking ‘what are your top character strengths?’, I suggest it is better we ask: ‘what attitudes and behaviours are strong within this situation at this time?’ Far better to believe in the power of multiple possibilities than to be defined with limited powers.

The Guidance of Values

So, if we shift our focus on well-being and behaving from the individual to the context, how might we better support and guide an individual on their unique journey in life? Rather than consideration of a person as having a

References

certain number of ‘character strengths’ to a greater or lesser degree, I suggest we invest in understanding ‘the power of living according to our values’. Unlike the proposed assessment of ‘character strengths’, we are not defined by our values. Rather, our values are the things that we consider most important in life. They represent ways of being and behaving that we consider as valuable guides for an authentic life. They form the basis for the development of many of our beliefs about what matters in the world, and what attitudes and behaviours we choose to express. As such, the identification of our values can help us understand more about how

we operate in the world while also honouring context and the ever-changing nature of our social identity. Our values represent what matters to us within a flexible, ever-changing, multi-faceted existence. I suggest that it is incredibly useful for any social group, be it a family, a classroom or a staffroom, to spend time identifying shared values that inform normative development and our shared understandings of the world.

I formulated the idea of Contextual Wellbeing (Street, 2018) as a means of better understanding our place in the world as social beings. The Contextual Wellbeing framework proposes that we are a ‘well being’ when we experience belonging and engagement within a healthy social context. A healthy social context is a context that meets our fundamental needs for relatedness, autonomy and competency (Ryan & Deci, 2012) in an equitable way. A focus on values supports the development of contextual wellbeing with meaning and purpose. Moreover, the exploration of values within a classroom, living room or staff room helps us to understand and pay attention to what matters, without limiting our understanding of ourselves, or of who we can become.

If we can learn to accept and connect with both our ‘inner-most selves’ and our ‘outer-most contexts’ in a way that respects and responds to our values, we can learn to live well. ◆

Dr Helen Street is an education consultant, social psychologist and advocate for educational reform. She works in schools around the world supporting the equitable development of improved wellbeing, mental health and engagement in students and staff.

✉ Helen.street@uwa.edu.au

• Alkozei A, Smith R and Killgore W D S (2017) Gratitude and Subjective Wellbeing: A Proposal of Two Causal Frameworks. Journal of Happiness Studies. 19(5): 1519.

• Anonymous (2010) Kindness Can Improve Mental Wellbeing. Irish Medical Times. 44(42): 36

• Hammer J H and Brenner R E (2019) Disentangling Gratitude: A Theoretical and Psychometric Examination of the Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test-Revised Short (GRAT-RS). Journal of Personality Assessment. 101(1): 96.

• Lim M H et al (2021) A Randomised Controlled Trial of the Nextdoor Kind Challenge: a Study Protocol. BMC Public Health. 21(1): 1.

• Peterson C & Seligman M E P (2004) Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. New York: Oxford University Press, and Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

• Ryan R M & Deci E L (2012) Motivation, Personality, and Development Within Embedded Social Contexts: An Overview of Self-Determination Theory. In: E L Deci & R M Ryan (eds). The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation. Oxford: Oxford University Press

• Street H (in press) Everything Changes – how to hold on when the world lets go.

• Street H (2018) Contextual Wellbeing – creating positive schools from the inside out. Perth, WA: Wise Solutions.

6 | International School | Spring 2023

Spring 2023 | International School | 7 Features Special offer Try our complete package for only £250 Get all the resources and professional development you need to plan outstanding maths lessons for just £250. For more information scan the QR code opposite or get in touch using the details below: International schools package Scan the QR code international@whiterosemaths.com whiterosemaths.com/international-schools +441422 433 323

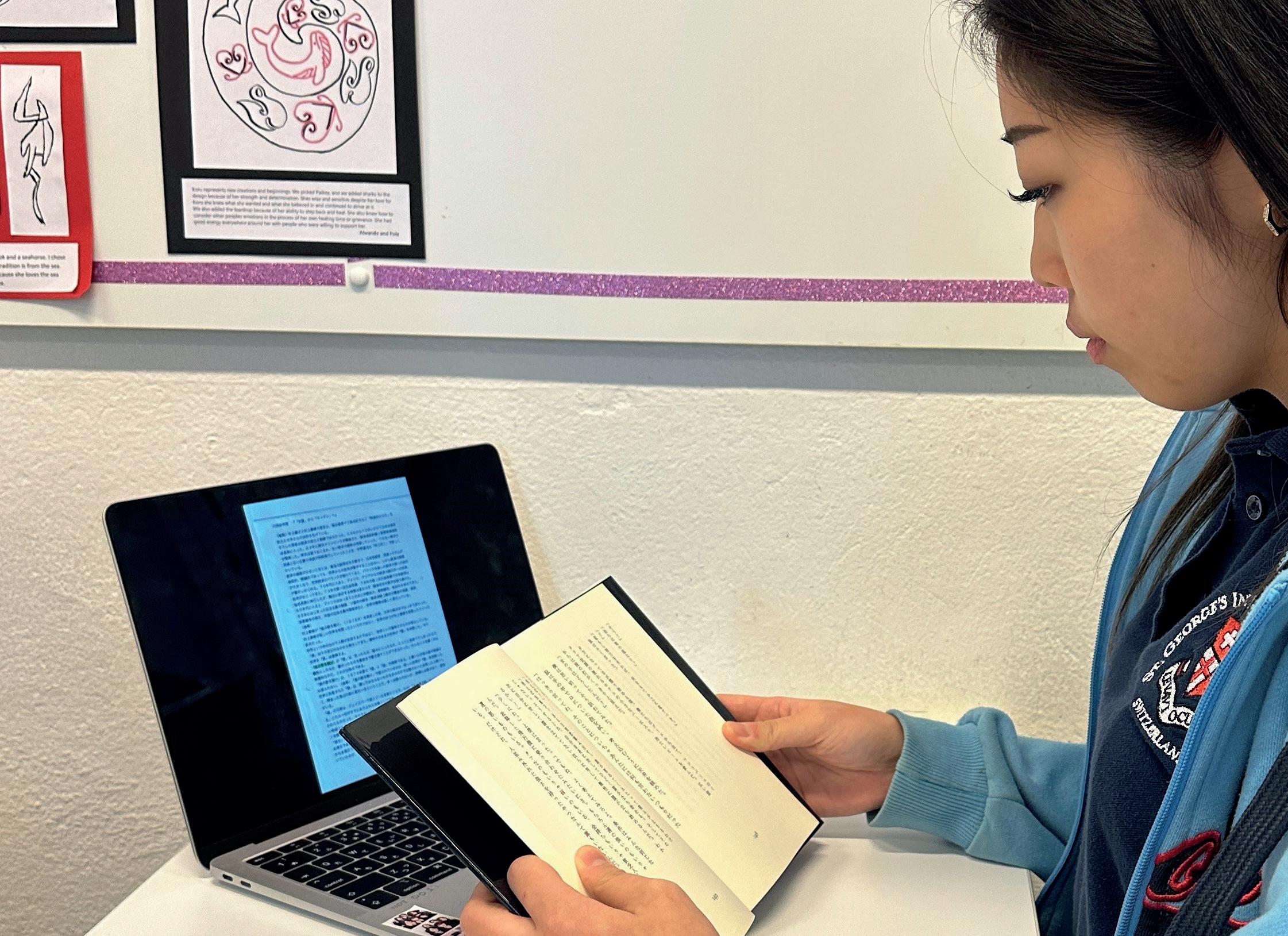

What words would YOU use to describe 2022?

By Elisabeth Neiada

By Elisabeth Neiada

As I think back on 2022, I reflect on the big moments, thoughts, feelings, and even smells that came along during the year. I pause for a minute and ask myself: ‘What words would I use to describe this year?’. As both a mother of young children and a teacher, I love words: words are powerful, words are unique, words are descriptive, and words offer endless possibilities.

My first word is Growth, personally and professionally.

Professionally, I experienced growth, as in 2022 I started and completed the data collection for my PhD. It was one of the most memorable moments, and inspired me to write this article, hoping to share the initial findings of my research in Education, which addresses parental engagement in three International Baccalaureate (IB) schools in Athens, Greece. My research seeks to explore how parental engagement is understood and manifested in the IB Diploma Programme (11th and 12th grades in High School). The three IB schools that participated in my research are ‘same, same but different’, as previously noted (Neiada, 2022), with similarities and differences. All offer one or more of the IB Primary Years Programme (PYP), Middle Years Programme (MYP) and Diploma Programme

(DP), and are thus connected to the IB mission, Learner Profile and international mindedness (IB, 2020). All are private schools with high tuition fees, catering for families of higher socio-economic status (SES), and could be described as ‘elite schools’ (Valassi, 2009). Yet, each school includes Greek elements to different extents, because of their geographical location, cultural ties to the country, and being part of the wider Greek educational system.

As might be expected in such a study, my research is underpinned by theoretical assumptions and empirical observations. Theoretical assumptions suggest that parental engagement is a multi-faceted and versatile term, which comes in all shapes and sizes (Goodall, 2017; Epstein & Sheldon, 2002). For instance, it includes parents’ orientations, attitudes, practices, behaviours, and identities when involved in their child’s education (Barr & Saltmarsh, 2014). Parental engagement concerns the involvement of parents in students’ academics at school (Epstein et al, 2002), as well as in students’ extra-curricular and holistic learning outside of school, especially at home (Goodall, 2017). Moreover, successful parental engagement creates strong ties between parents and educators, leading to fruitful home-school partnerships (de Oliveira Lima & Kuusisto, 2019; Epstein & Sheldon, 2002). Consequently, parental engagement becomes a continuous, interactive, mutual process between parents

8 | International School | Spring 2023

and schools. Existing literature suggests that positive forms of parental engagement positively impact the whole school community (IB, 2020). For instance, students at such schools experience an increased quality of education and present higher levels of academic attainment (Garcia et al, 2016; Sterian & Mocanu, 2013); schools have a positive school culture, pursuing innovation, continuous learning and improvement (Connolly et al, 2019); and parents enjoy stable and nurturing home environments, with emphasis on parental confidence and skill (Lawson, 2003). Negative forms of parental engagement, on the other hand, can be a source of agony and stress for educators, parents, and students (Xanthacou et al, 2013). When parental engagement is unsuccessful, it creates a gap between parents and educators, which is problematic for students (Antonopoulou et al, 2011).

Moving on to empirical observations of parental engagement in schools, insight is shared by various researchers who have worked in schools in Greece and abroad (see, eg, Goodall, 2017; Lazaridou & Gravani Kassida, 2015; Sheridan & Kratochwill, 2008). It is argued that parental engagement is culture- and context-bound (Faircloth & Rosen, 2020; Barr & Saltmarsh, 2014), depending on different family and school factors – which may include parents’ backgrounds, upbringing and style, and a school’s type, mission, profile and size. According to Barr & Saltmarsh (2014), there is a range of ways in which schools address their relationships with parents, and in which parents choose to – or not to – engage with their child and their schooling.

Considering the above, I was intrigued to study parental engagement myself, hoping to draw conclusions in relation to what parental engagement means in theory and practice, in the context of IB schools in Greece. My data collection process involved listening to and considering the viewpoints and experiences vis-a-vis parental engagement, through interviews and focus groups, of both parents and educators of IB Diploma students. All participants voluntarily expressed interest and committed to participating in my research. I was fortunate to be able to conduct a total of forty-two interviews, the majority faceto-face, in school premises, with others completed online due to remaining Covid-19 constraints. All interviews were recorded, and then transcribed and translated (from Greek to English) by me (I am bilingual). Interviews lasted for around an hour, although their importance and vibrancy echoed with me for much longer. I am currently working on the main data analysis, but in the following paragraphs I share some of my findings that originate from an initial analysis and stand out in a first ‘scanning’ and read-through of the data.

Let me begin by discussing different forms of parental engagement, namely between parents and children, and between parents and educators. Parental engagement between parents and children can be divided into three broad categories: academics, extra-curricular activities, and social-emotional engagement. Parental engagement in academics concerns parental participation in students’ learning, assessments, grades, and university applications. A noteworthy aspect of parental engagement in students’ academics is private tutoring at home, which seems to be prevalent for students in IB schools in Greece. Private tutoring in the IBDP was described by one parent as ‘something essential that everyone does and is associated with societal stereotypes. Parents think that if they don’t do private tutoring, their child will stay behind or feel left out’. In turn, educators mentioned that private tutoring at home interferes with their teaching in the classroom, and makes their job more difficult. Parental engagement in extra-curricular activities happens mostly in practical ways, such as taking children to and from activities that contribute to the IBDP Creativity, Activity, Service (CAS) programme. Social-emotional engagement, meanwhile, relates to when parents support children’s emotional needs during their teenage years. For instance, one parent said that they are ‘present in a child’s life, sensitive to surrounding circumstances and the psychology of the child, offering them a safety net’. Engagement between parents and children happens to the extent the child wants it to, and is based on ‘trust’, ‘respect’, ‘tolerance’, ‘patience’ and ‘open communication’.

The second form of parental engagement, between parents and educators, is something participants were asked to describe in terms of the dynamics and roles that evolve between them. One educator said that ‘both parties should invest time and effort in such relationships,

Spring 2023 | International School | 9 Features

Positive forms of parental engagement positively impact the whole school community.

as they are important and necessary’. They thought that relationships with parents vary, as they are determined by people’s personalities, experiences, and way of thought – which cover a large spectrum. Nevertheless, most educators mentioned that they have ‘positive’, ‘trusting’, ‘close’ and ‘professional’ relationships with parents. In educators’ words, ‘parents are aware, grounded and well-informed about the IBDP’; ‘they are appreciative of the help and advice we give them’. Parents said that they have ‘excellent’, ‘healthy’, ‘interactive’ and ‘communicative’ relationships with educators; ‘educators are honest, close to students, know their job well and prioritize students’ needs’. Parents and educators therefore seem to agree about their complementary roles in parental engagement: ‘parents are the connecting link between teachers and child. They inform teachers about things they see at home, so that they can view the child holistically in the classroom’. In turn, ‘educators are proactive with parents: they inform them of a situation’, and ‘respect parents’ worries for their child’. Participants thought that, in such circumstances, parents and educators are a team, in collaboration and partnership. This leads to ‘independent, happy and confident children’, while ‘parents discover things about their child in a different light. They know the school better and have an ally in educators’. Also, ‘children know that their learning is supported from home and school; educators know that parents are not adversaries, [but are] supporting their effort’. When parents and educators do not form strong relationships, either because of excessive intervention or crossing boundaries, children may become stressed and insecure, with parents and educators assuming separate and distinct roles.

From the above, it is clear that parental engagement is a triangular process between parents, educators and students. In interviews, my favourite question to participants was ‘What words or images would you choose to describe parental engagement?’. Parents stated that parental engagement is: ‘connection with the child through discovery and exploration’; ‘an image: a child, in several stages of life, running, laughing, playing, etc. and the parent standing in the back, as an observer’; ‘balance, support, and continuing the educators’ effort and work’; ‘an equilateral triangle: parents, students, and educators are a triangle, and we all benefit from it’. Educators said that parental engagement is ‘necessary, a crucial pillar in the educational process and school experience of children’. ‘It should be evident, coherent and intelligible in the work of educators and school administrators’. One educator said that parental engagement ‘takes three to tango: I want the parent to be there in multiple ways, along with the teacher and student’. The same idea was echoed by other educators, who described parental engagement as: ‘love, care, support, safety and presence in your child’s life’; ‘to believe in your child as a parent and show it to them’.

Following the different forms and definitions of parental engagement, findings helped me outline elements that influence and contribute towards parental engagement. Participants suggested that parental engagement is influenced by a number of elements, the most prominent being the school, the IB Diploma Programme, and the Greek culture. By school, I mean the people in a school, as well as the school’s profile and policies on how to approach parents and parental engagement. The majority of parents expressed views such as that ‘the school really wants to engage us, invites us to participate in activities and keeps us informed’. In this endeavour, the role of the Diploma Programme Coordinator in engaging parents was highlighted in all interviews. For instance, one parent noted that ‘the IB Coordinator is extremely important, in how much he understands and believes in the IB, and engages parents. We are very pleased with him’. Parents also expressed the view that all three schools are ‘well-established, well-trusted, and well-known, so we do not need to get overly engaged’.

Finally, an idea commonly expressed by parents and educators concerned the Covid-19 pandemic’s aftermath in parental engagement. One educator said: ‘Covid-19 has been a huge barrier to parental engagement and impacted human relationships to an immense extent. Before Covid, there was passion and enthusiasm in human relationships and conversations. For

10 | International School | Spring 2023 Features

It is clear that parental engagement is a triangular process between parents, educators and students.

instance, parent-teacher conferences were an important event, while now everything happens online, and you don’t see the same directness in our relationships’.

Concerning the influence of the IBDP on parental engagement, parents and educators agreed that the IB mentality and philosophy place students at the heart of learning, ‘promoting creative thinking and personalised learning’. Small class sizes, the high level of learning and the interconnectedness of subjects may discourage parents from getting involved, as they do not easily understand the IBDP curriculum. All participants mentioned, too, a considerable difference and gap between the Greek educational system and the IBDP, in terms of curricula, assessments and grades. As a result, parents might show a lack of interest and/or over engagement in academics and school matters. Still, all parents mentioned that they were extremely satisfied with the IBDP as a programme, which they reported was also the case for their children.

Finally, the Greek culture and mentality were noted as major elements influencing parental engagement. Indicatively, participants said that the ‘Greek culture and mentality of parents comes above all else and shadows everything’. Specifically, ‘the role of family in Greece is paramount, and not necessarily in good ways; it suffocates children’. For instance, ‘Greek parents pamper and over-protect their children, and want them to succeed at all costs’. This is attributed to parental aspirations and high expectations for children to achieve good grades and enter Ivy League universities, which reflects upon parents’ engagement with educators and the school. One participant expressed the view that ‘no school or program will ever ‘dethrone’ the Greek traditional mother from her position’. I believe such an approach comes in sharp contrast to the IB mission and ideals that promote students’ autonomy, independence, and personalised learning. Thus, participants observed that the implementation of IB programmes in schools in Greece is very much culture-based.

References

• Antonopoulou K, Koutrouba K & Babalis T (2011) Parental involvement in secondary education schools: the views of parents in Greece. Educational Studies. 37(3): 333-344.

• Barr J & Saltmarsh S (2014) ‘It all comes down to the leadership’. The role of the school principal in fostering parent-school engagement. Educational Management Administration & Leadership. 42(4): 491-505.

• Connolly M, Eddy-Spicer D H, James C & Kruse S D (2019) The SAGE Handbook of School Organization. Los Angeles, Calif: SAGE.

• de Oliveira Lima C L & Kuusisto E (2019) Parental Engagement in Children’s Learning: A Holistic Approach to Teacher-Parents’ Partnerships. In: Pedagogy in Basic and Higher Education-Current Developments and Challenges. IntechOpen.

• Epstein J L & Sheldon S B (2002) Present and Accounted for: Improving Student Attendance Through Family and Community Involvement. The Journal of Educational Research (Washington, DC). 95(5): 308-318.

• Epstein J L, Sheldon S B, Sanders M G, Simon B S, Clark Salinas K, Rodriguez Jansorn N & Van Voorhis F L (2002) School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/ERICED467082/pdf/ERIC-ED467082.pdf

• Faircloth C & Rosen R (2020) Childhood, parenting culture, and adult-child relations in global perspectives. Families, Relationships and Societies. 9(1): 3.

• Garcia M E, Frunzi K, Dean C B, Flores N & Miller K B (2016) Toolkit of

My second word, revisiting my article’s initial question about words to describe 2022, is Gratitude.

I feel extremely grateful to participants, for their genuine enthusiasm towards my research and willingness to talk about their experiences and thoughts on parental engagement. Their interviews and words offered me endless insights not only into parental engagement as a phenomenon, but also into the importance of familyschool relationships as discussed and practised in everyday life. My initial analysis of data has surfaced a couple of important take-aways that will inform the main data analysis: first, parents and educators alike are favourably disposed towards parental engagement. They value parental engagement, believe in its benefits, and seek for it to happen in schools. Consequently, in most cases, relationships between parents and educators are positive and productive, benefitting students and the whole school community. Second, parental engagement is based on human relationships and connections between educators, parents and students. I believe that human relationships and connections are vital, especially in environments such as schools that are human-centred. In cases where parental engagement is negative, human relationships and connections have the power to transform the engagement into something more positive. The IBDP promotes and embraces human relationships and connections through its pedagogy, as is the case for participating schools in my research. It is on this positive note that I finish this article, feeling confident that parental engagement in research and practice will continue to grow, leaving a positive imprint on international schools and the world of Education. ◆

Elisabeth Neiada is a doctoral student in Education at the University of Bath, UK. She has taught at international and IB schools in Athens, London, Paris and New York.

✉ een26@bath.ac.uk

Resources for Engaging Families and the Community as Partners in Education. Part 1: Building an Understanding of Family and Community Engagement. REL 2016-148. Regional Educational Laboratory Pacific.

• Goodall J (2017) Narrowing the achievement gap: Parental engagement with children’s learning. London: Taylor & Francis.

• IB (2020) Facts and Figures. https://www.ibo.org/about-the-ib/facts-and-figures/

• Lawson M A (2003) School-family relations in context: Parent and teacher perceptions of parent involvement. Urban Education. 38(1): 77-133.

• Lazaridou A & Gravani Kassida A (2015) Involving parents in secondary schools: principals’ perspectives in Greece. International Journal of Educational Management. 29(1): 98-114.

• Neiada E (2022) Parental engagement re-imagined: new beginnings and fresh starts. International School. Spring: 6-8

• Sheridan S M & Kratochwill T R (2008) Conjoint behavioral consultation: Promoting family-school connections and interventions. Springer Science & Business Media.

• Sterian M & Mocanu M (2013) Family-school partnerships: Information and approaches for educators. Euromentor Journal. 4(2): 166.

• Valassi D (2009) Choosing a private school in the Greek education market: a multidimensional procedure. Atelier. 6: 13-14.

• Xanthacou Y, Babalis T & Stavrou N A (2013) The role of parental involvement in classroom life in Greek Primary and Secondary education. Psychology. 4(02): 118.

Spring 2023 | International School | 11 Features

Developing effective Environmental and Sustainability Education for

By Lauren Binnington

By Lauren Binnington

As an educator at an international school in Vietnam, a country that generates the 4th largest amount of plastic waste in Southeast Asia (annually throwing 730,000 tones into the ocean: Hai and Vu, 2019), and recognising that schools contribute up to 19% of plastic waste in Vietnamese cities (Verma et al, 2016), I have become personally invested in educating young people to develop skills for long-lasting change for our planet. Environmental and Sustainability Education (ESE) refers to teaching and learning that develops the knowledge and skills needed to deal with global environmental challenges, seeking to equip young people for a rapidly changing planetary environment. The United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), aiming to eradicate poverty, reduce inequalities, and develop sustainable environmental approaches (UN, 2015), have been a catalyst for many international schools to grow ESE provision, providing more regular opportunities for students to develop sustainable behaviours that minimise their environmental impact. Successful ESE is interdisciplinary, locally relevant, promotes lifelong learning, and ‘empowers learners of all ages with the knowledge, skills, values and attitudes to address the interconnected global challenges we are facing’ (UNESCO, nd).

So how do we build a curriculum approach that develops proenvironmental behaviours in a sustainable way? Early ESE approaches shared knowledge through communication campaigns, or taught knowledge related to global issues, aiming to alter attitudes and therefore motivate behaviour change (Hungerford and Volk, 1990). However, simply learning about climate change fails to develop the social and emotional action competencies needed for behavioural change, and focuses more on what young people will do in the future than

long-term behaviour change – the changing focus of education

on what impact they can have now. Environmental Psychology, which explores humanity’s relationship with the environment, can help schools to develop effective ESE, by considering how knowledge and attitudes become behaviour. Theories suggest that sustainable pro-environmental behaviour is influenced by motivating variables such as environmental sensitivity or having empathy towards the environment (Hungerford and Volk, 1990) which can be developed from taking direct environmental action and having experiences in the outdoors. Traditionally, ESE provides more indirect experiences through videos or case studies that have limited impact; learning about climate change, and living with a flooded street experiencing the result of climate change, generates different emotions. Research shows that experience in natural areas, especially in childhood, creates a commitment to engage in pro-environmental behaviour (Chawla, 1999). A recommendation for ESE is therefore to provide informal outdoor experiences or more formalised planned action, such as taking care of a local area, to develop environmental sensitivity or environmental consciousness in young people (Chawla, 1999).

Another important motivator involves taking ‘ownership’ of environmental issues, gained through having in-depth knowledge regarding the issue, its implications, and action strategies, and having self-efficacy and belief in one’s ability to enact a change (Hungerford and Volk, 1990). This is also influenced by values, attitudes and emotions, personality, culture, and the social norms of family and peers (Kollmuss and Agyeman, 2002). Therefore, for effective ESE we need to develop a culture of sustainability, making pro-environmental behaviour the norm; this involves the entire school community.

ESE also needs to break down barriers to action, such as existing patterns of behaviour (Kollmuss and Agyeman, 2002). An individual’s motives, even with environmental knowledge, can be contradictory. For example, while

wanting to have an environmentally friendly lifestyle we may also focus on our immediate comfort when we choose to drive rather than cycle in the rain (Kollmuss and Agyeman, 2002). These internal barriers to action can be partly overcome through emotional involvement and learning to respond empathetically to environmental issues. This depends upon our locus of control; when we feel we can act, then we can cope with strong emotional reactions (Kollmuss and Agyeman, 2002). In dissertation research for my Masters in Education, graduates from my school expressed a willingness to take action that came from the knowledge and experiences they gained while at school, but also an inability to act due to feeling that actions were too inconvenient or wouldn’t make a difference to the wider global problem.

Spring 2023 | International School | 13 Features

For effective ESE we need to develop a culture of sustainability, making proenvironmental behaviour the norm.

ESE could develop skills to reduce these barriers by enabling students to create their own projects and increase their self-efficacy; schools can provide experiences for students to take meaningful action and increase competence. In this approach, ESE requires student involvement in decisionmaking and outcomes themselves. For example, rather than simply making students use recycling bins (a passive action), instead they could be tasked with generating, trialling, and implementing recycling strategies themselves, thus engaging in direct problem-solving with immediate impact. Effective ESE focuses on the skills young people need to consider their actions and make behavioural decisions. If we want to develop self-efficacy, then we need to increase these experiences in our schools. Further ways to develop self-effi cacy can be through growing student-led projects, involving students as action researchers, leaders of campaigns, activists, researchers, and educators. Young people instigating action themselves has greater meaning; taking classroom-based learning into their community through project-work, such as designing a sustainable refi ll service

for a local business, gives responsibility for empowering and developing the capacity for change in others to young people, enabling them to practise their skills. Educators can work with parents, community members and local organisations to increase the impact that young people can have within the community and as role models.

What has become clear from my own research is that simply learning about sustainability through ESE is not enough; young people need to have experiences and opportunities for action. ESE can

References

provide knowledge of environmental issues and opportunities to engage in active projects, develop leadership skills, and make connections with like-minded others. Schools need to take risks and allow young people to initiate and work through change actions in the present, gaining immediate experiences beyond the classroom that impact within the community. By empowering young people, encouraging action, developing project work, and engaging in refl ection, they will begin to act in creative ways and have an immediate and longer-term impact on the world. ◆

✉

• Chawla L (1999) Life Paths into Effective Environmental Action. The Journal of Environmental Education. 31(1): 15-26.

• Hai T T & Vu N (2019) The Crisis of Plastic Waste in Vietnam is Real. European Journal of Engineering Research and Science. 4(9): 107-111.

• Hungerford H R & Volk T L (1990) Changing learner behavior through environmental education. Journal of Environmental Education. 21(3): 8–21.

• Kollmuss A & Agyeman J (2002) Mind the Gap: why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behaviour? Environmental Education Research. 8(3): 239-260

• United Nations (2015) Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution 70/1 adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Available from: http://www. un.org/en/ga/70/resolutions.Shtml [Accessed 18 April 2019].

• UNESCO (nd) Global Action Plan for Education for Sustainable Development (2015-2019). Available from: https://en.unesco.org/globalactionprogrammeoneducation [Accessed 23 December 2021].

• Verma R L, Borongan G & Memon M (2016) Municipal Solid Waste Management in Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam, Current Practices and Future Recommendation. Procedia Environmental Sciences 35: 127-139.

14 | International School | Spring 2023

Lauren Binnington is Deputy Headteacher at the British International School, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

lauren.binnington@googlemail.com

An individual’s motives, even with environmental knowledge, can be contradictory.

Meet students where they are with digital titles

The Sora student reading app offers an extensive catalog that spans the interests and reading levels of every student, and includes titles in over 100 languages. With ebooks for visual learners, audiobooks for auditory learning and diverse subject matter, Sora helps makes sure every child feels included and empowered.

Learn more at company.overdrive.com/international-schools

What is a concept? A brief journey from Plato’s forms to the Overton Window

By Paul Regan

It is empirically obvious that an ability to make sense of reality must have conferred an evolutionary advantage on our ancestors. From a very early age, experience tells us that as soon as we become confused or mistaken, we become vulnerable to manipulation and attack. But, it is less obvious how our species has evolved to encode and decode meanings and patterns in our environment in order to construct the most successful models that can both protect us, and also, as a by-product, guarantee power and knowledge. For example, in times of crisis and danger it may have been too time-consuming to seek unvarnished truth, so instead, successive generations developed the ability to make heuristic, conceptual models which repeated experience revealed to be useful and life-saving. Adults then found new ways to pass them on to their offspring via innovations such as language and play. If you could escape the predatory lion by knowing first how to avoid him and then later how to hunt him, you might survive long enough to reproduce and pass on your genes. For Humanity, the survival of the fittest owes a great deal to an inherited ability to understand and exploit ecosystems by using and communicating concepts.

Fast forward to today and, give or take the occasional refit, we are still relying on those same mental models

not only to survive as before but also, inter alia, to socialise, make ethical choices, and navigate complexity. Failure to do so can condemn an individual to make poor choices, repeat failures rather than learn by them, and lose touch with reality. Little wonder then that conceptual learning is part of the toolkit which educators are being advised or told to understand and to include in their teaching. Quite rightly, conceptual learning has made a comeback.

But what exactly is a concept and how can it benefit the learner?

Firstly, although concepts are basically a description of events, facts or aspects of reality, not all concepts are born equal. What they all do share, however, is their abstract quality. You cannot see or touch them; nevertheless, you can think about them, use them, and pass them on. They are descriptive, even reflective, inasmuch as they either transcend a body of facts or events or neatly synthesise or summarise them, placing them in classes or categories, the better to understand them. And they are interpretative, designed to represent a state of affairs by appealing to certain cognitive faculties such as reason, intuition and imagination. A good example of a concept is causation. As the enlightenment philosopher David Hume observed, you cannot see or touch a cause or en effect, but you can infer both of them due to a reasonable confidence in the uniformity of nature (another concept). It is also descriptive in that it neatly

16 | International School | Spring 2023

But what exactly is a concept and how can it benefit the learner?

simplifies, packages and categorises a universal phenomenon, and it helps us to recognise it wherever it occurs.

But concepts, unlike theories, are not or need not be evidence-based. A ‘dragon’ is a concept even though it is a fictional creature, whilst Humanity is a concept based upon observation of individual men and women. Plato’s seminal idea of ‘Forms’ – ideal, eternal and unique qualities of which our reality is but a partial representation – is profoundly metaphysical. It is also a theory of knowledge since it claims that knowledge of the Forms, impossible for most of us, is the only true knowledge, whilst everything else is mere opinion. For the German eighteenth century philosopher Emmanuel Kant, a concept is a mental representation which refers to one of twelve categories such as quality, quantity, relation, and possibility. In their turn, these categories act like a pair of spectacles which we wear in order to interpret and even to construct reality.

The International Baccalaureate (IB) Primary Years Programme (PYP) assessment programme makes explicit its commitment to conceptual learning and even has its own set of eight concepts, which it requires teachers to weave into their disciplines via their scope and sequence curriculum planning documents. IB teachers are expected to implant in the minds of their students not Kant’s categories exactly, but the seeds of a conceptual framework which in theory is designed to promote a holistic understanding of the connectivity of facts, events, ideas and beliefs. They even sound similar with titles such as function, form, causation, change and connection.

But concepts are not or should not be normative; they are descriptions or explanations of how things are, not how they should be. As they are not necessarily evidence-based, they can be differentiated from theories that are or should be based upon experiment and observation. Although the various terms known as concepts, categories and theories are often used interchangeably, they are quite different. Concepts are philosophical rather than scientific, and illustrative rather than definitive. This does not mean of course that they are false or misleading, just that they are ideas rather than verifiable facts. An ability to spot any attempt to win an argument by using concepts normatively, to move as it were from an ‘is’ to an ‘ought’, is one of the pillars of critical thinking. To fail to know when you are doing so is to commit the naturalistic fallacy, something most of us do several times a day by the way.

Which brings me finally to the concept of the Overton Window, and why I believe it to be an important tool for educators. Named after the political scientist who first coined it, Joseph Overton, it describes how at any one time in any one political entity (nation state, empire, city state and so on), there is a body of ideas, beliefs and ‘truths’ which are permissible. And conversely there are others that are not permissible by virtue of being too radical, or culturally unacceptable. Let’s call it the Zeitgeist. Politicians should be wary of upsetting the equilibrium of the window, but they frequently do so

anyway – often to their own cost or to the detriment of society.

Why have I chosen the Overton Window? For educators, it is a perfect example of a class of concepts which attempt to describe certain human phenomena or ways of behaving that we routinely observe but cannot quite explain or define. There are many others in this class, such as Occam’s Razor, and The Invisible Hand, which not only speak to aspects of our reality but can also be a guide to thinking about the world in a more ordered way. The first sets out a method for thinking by eliminating extraneous information, and the second explains the movement and effects of market forces.

The Overton Window shifts over time, but why and how does it shift and who makes the shift? The empowered citizen has a role to play within the window, but is not given advice about what he or she should want to take out or to bring in. That would be normative, which is forbidden. Thus over time does slavery and discrimination disappear whilst female emancipation and universal human rights make an appearance. But totalitarianism, war, and inequality can also return to the window since there is no assumption about inevitable moral progress. The Overton Window also explains why the recent attempt in Scotland to introduce radical legislation concerning change of gender without a proper medical licence was so emphatically rejected by the population. On the other hand recent pandemicrelated lockdowns and other non-medical interventions, although radical, were broadly accepted – albeit for only a relatively short time.

The Overton Window stands on its own as a way of thinking about the marketplace of ideas and policies which can be a rational guide for active and informed citizenship. Conceptual learning is all very well, but it can only be of value when the student both understands the meaning of concepts and can grade them according to their type and usefulness. I have used the Overton Window to illustrate my point for three reasons. Firstly, it explains why some policies work and others don’t. Secondly, it demonstrates how a well thought-out concept of its type can be a tool for learning. And thirdly, in our current time of iconoclasm, when we are busy debunking many of the most treasured notions of our histories and cultures, it will help students to at least make some sense of it all. ◆

Spring 2023 | International School | 17 Features

Paul Regan has been headteacher of four international schools and is now an educational consultant for an Indian educational group. ✉ paul_regan5@hotmail.com

But concepts, unlike theories, are not or need not be evidence-based.

Mindfulness practice in the school environment: a solution to students’ and teachers’ state of wellbeing

What are the stressors teachers and students face? ’

The academic world is ever changing, both for teachers and students. The role of a teacher requires continuous flexibility with an ever-evolving desire to motivate students in their educational journey. It requires adaptation to new and increasing expectations and variations, technology shifts and pastoral care elements. Students are not exempt from pressures and stressors either: firstly, an array of internal factors influence their wellbeing such as energy levels, family pressures, social complexities and identity development. These, along with increasing pressure to achieve, frequency of examinations and assessment, and their own academic ability, all contribute to high stress levels students experience on school grounds.

What is Wellbeing?

Wellbeing is made up of two factors: how a person feels, and how a person functions. Often this is a bi-directional relationship where either factor can influence the other. For example, when we feel good we tend to function well; when we feel overwhelmed/stressed

References

our performance can suffer; when our motivation reduces we can feel distressed; when our behaviours result in positive outcomes we feel proud/energised. Our wellbeing can also be directly impacted by personal, social and societal factors with positive or negative effects - including familial demands, academic or career stress, financial worries, or other mental health and physiological needs being met or unmet.

What happens when wellbeing is negatively impacted?

When looking at wellbeing from both teacher and student perspectives, similar trends both in behaviour and cognition can be observed. Clearly, with an absence of beneficial skills comes reductions in other areas of functioning related to wellbeing. Teachers and students can experience:

• Difficulty with emotion regulation, including irritability, depression, and anxiety

• Decline in concentration, information retention and self-efficacy

• Feelings of burnout or being overwhelmed, including frustration,

Armstrong, T. (2019). Mindfulness in the Classroom: Strategies for Promoting Concentration, Compassion, and Calm. ASCD.

Chittaro, L., & Sioni, R. (2014). Evaluating mobile apps for breathing training. The effectiveness of visualization. Computers in Human Behaviour, 40, 56-63.

Crowe, A. (2021). The Importance of Self Care for Teachers & 20 Ways to Help. Prodigy. https://www. prodigygame.com/main-en/blog/teacher-self-care/

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Context: Past, Present, and Future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 144-156.

Moyano, N., Perez-Yus, M.C., Herrera-Mercadal, P. et al. (2021). Burned or engaged teachers? The role of mindfulness, self-efficacy, teacher and students’ relationships, and the mediating role of intrapersonal and interpersonal mindfulness. Curr Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02433-9

Roberts-Wolfe, D., Sacchet, M. D., Hastings, E., Roth, H., & Britton, W. (2012). Mindfulness Training alters emotional memory recall compared to active controls: support for an Emotional information processing model of mindfulness. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6(15), 1-13.

Sanger, K. L., & Dorjee, D. (2015). Mindfulness Training for Adolescents: A Neurodevelopmental perspective on investigating modifications in attention and emotion regulation using event-related brain potentials.

Cognitive Affect Behavioural Neuroscience, 15, 696-711.

Savill-Smith, C,. & Scanlan, D. (2022). Teacher Wellbeing Index 2022. https://www.educationsupport.org.uk/ media/zoga2r13/teacher-wellbeing-index-2022.pdf

Zalaznick, M. (2017). Mindfulness exercises for children: Relaxation techniques calm K12 students and staff, leading to better grades and better behavior. Retrieved from https://www.districtadministration.com/ article/mindfulness-makes-difference-school

exhaustion and decreased memory

• Negative impacts on physical health, including headaches, eating, tension, sleeping

• Maladaptive coping strategies, such as substance abuse

• Feelings of decreased motivation and engagement

• Teachers may experience potential apathy for the role

• The student-teacher relationship may be negatively affected.

With this awareness of negative outcomes, what strategy can be utilised within the classroom to support both students and teachers in their wellbeing journey? The answer is Mindfulness Practice.

What is Mindfulness?

Mindfulness is the ability to intentionally focus on the present moment, allowing internal and external events or distress to pass without judgement and can be practised through multiple skills and activities. Part of mindfulness practice is increasing one’s own levels of consciousness both on a physical and psychological level. Consciousness is a crucial element of mindfulness as it increases skills of awareness and attention, which is beneficial for individual wellbeing.

What does Mindfulness consist of? Mindfulness is made up of three core components: attention, attitude and intention.

1. Attention is the ability to prioritise the information an individual receives, either from external situations or internal cognitions, and using mindfulness skills to remain attending to the present: meaning that as the mind wanders to distressing or uncomfortable thoughts, the individual uses mindfulness tools to recall their focus and calm their mind once again.

2. Attitude highlights the importance of the individuals’ approach to mindfulness. It has a direct impact on the outcome effectiveness; curiosity and openness are crucial for allowing non-judgmental thoughts and practice.

3. Intention is the goal, plan or steps to succeed in mindfulness practice. Intention is the motivation to carry out the practice or task, and is the catalyst to commence the mindfulness activity, and consistently practise long-term.

18 | International School | Spring 2023 Features 4 | International School | Spring 2023 Advertorial Feature

Benefits of mindfulness for students and teachers

There are a number of benefits that have been observed in both adults and youth when utilising mindfulness practices.

Individually, mindfulness can aid in focussing the mind, improving cognitive processing, engagement and, overall, academic performance. Alongside this, attention during class and learning can improve which supports motivation to learn. As mindfulness has shown to improve emotion regulation and provide advantageous skills, students may find they possess more effective tools and responses in anxiety-provoking situations such as exams, presentations and social situations. Additionally, with improved emotion regulation skills from acceptance and non-judgment, students may experience increased self-compassion and compassion towards others.

Within the classroom environment, mindfulness can be used to positively transition through different areas of the day, such as from the rush of arriving and settling into the day, or in between different classes. For students with multiple responsibilities and expectations, mindfulness can support the mental weight each factor requires of the student, allowing them to deliberately take time to breathe, pause, and recalibrate. Students are also able to accept their present situation and sensations, and feel a sense of control over what they can, and accept the factors they can’t. When experiencing distressing emotions such as anger or frustration, students can regulate their emotions faster, allowing for effective problem-solving. For both teachers and students mindfulness has been shown to have significant impacts on wellbeing both on a cognitive and emotional level as it helps to relieve stress, increase self-regulation and self-efficacy, improve memory and engagement, and aid in social and emotional development.

Strategies in the classroom

When beginning the classroom mindfulness journey, it may feel overwhelming for teachers to integrate another focus or dedicate time to another activity, during an already busy day. But with mindfulness, the practice can be as short as 5 minutes, which can include breathing, movement (such as yoga or mindful walking) or writing. When implementing these effectively, the benefits

from mindfulness can reduce time spent supporting students and result in more time dedicated to teaching overall. Firstly, make mindfulness practice more attractive to students by identifying celebrities of interest who utilise mindfulness. This can be a good way to get students engaged with the activities. For example, Lebron James practises on the bench during basketball games, Emma Watson is a proud Headspace advocate, and Lady Gaga utilises mindful meditation.

Schedule consistent practice with “5 Mindful Minutes”. At the beginning of the day, the entire class and teacher focus on sitting comfortably with a relaxed body, practising a breathing exercise: focussing on the breath, the feeling of the chest rising and falling, and completing a body scan to notice different tensions. Whilst doing this, practise the present moment thinking and self-compassion; when the mind wanders, accept and bring the mind back to the present. It can help to set a hidden timer, to remove temptation to count down the minutes.

Make mindfulness part of the daily activities and spaces. Calm breathing can be inserted into multiple areas of the day, such as at the start of each class, before lunch or after breaktime to allow for regulation. Identify areas in the classroom that can be relaxing and mindful spaces for students to use, for students to regulate, refocus, re-energise and rejoin the class. Don’t be afraid to use mindfulness in the moment, when noticing the overall classroom feeling.

Have fun with mindfulness by creating sensory activities for yourself and students. Have students pass round

different sensory objects, whilst remaining quiet and focussed, breathing slowly and noticing how the items feel in their hand. This can also be done with mindful eating, where foods can be used to bring attention to the senses and the present moment. Spend time mindfully listening to calm music, practising acceptance and bringing the self back when the mind wanders.

Build in time for the class to mindfully journal. This allows individuals to practise self reflection, track their experiences, identify and monitor their emotions, and practise present moment openness. Conduct a body scan and write down the sensations in the body at present as part of the journal.

Utilise resources and apps created to support the distribution and practice of mindfulness, including the Calm app and Headspace.

With all this in mind, mindfulness can support both teachers and students to feel increased motivation, value in themselves and others, energised by their abilities and efforts and effective in their work, all whilst regulating their emotions, feeling a sense of control and nonjudgment, and capable to get through the school day. ◆

Spring 2023 | International School | 19 Features Spring 2023 | International School | 5 Advertorial Feature

Abby Dale-Bates is one of Komodo’s Registered Child & Family Psychologists. She has experience working with children, adolescents and families focussing on mental health, social health and behaviour support within primary health, community and residential settings. At Komodo, she supports schools in their data-driven wellbeing journey and can be seen presenting at numerous conferences across the globe on student and staff wellbeing.

Challenges Faced By Women Who Lead

Part One: Four Themes from Interviews with Women in School Leadership

By Kim Cofino

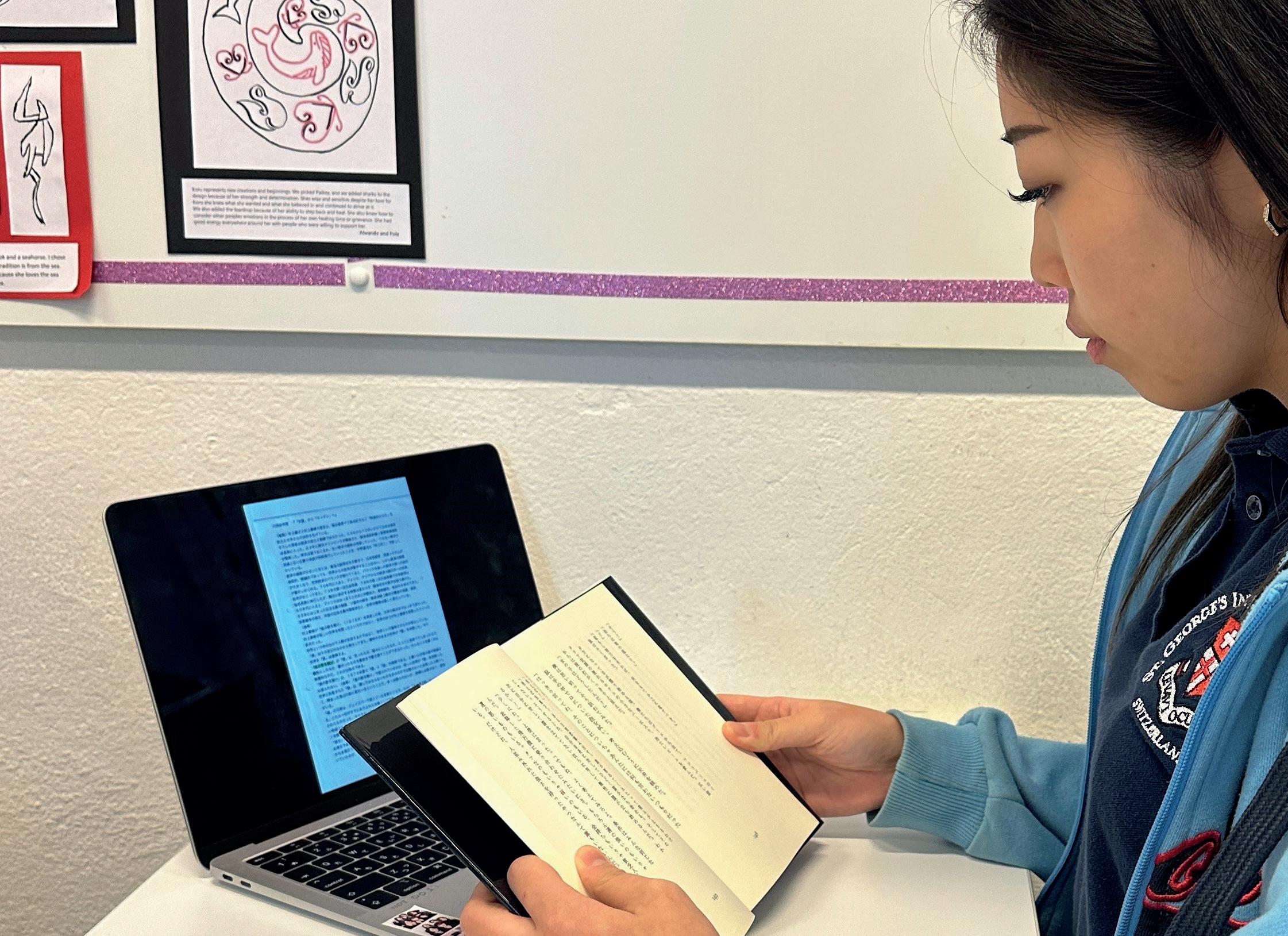

In the Spring of 2020, I interviewed over 70 successful female leaders (in international schools, and some public and private schools around the world) for the Women Who Lead program, in order to seek their personal stories and insights on the challenges and realities facing women in leadership in education. Those interviews highlighted many of the unique challenges that women face pursuing a leadership role in schools –and their stories can help aspiring leaders recognize that the path to leadership may share some common experiences and barriers for those who do not fit the stereotypical view of ‘a leader’.

Although we may have the perception that there are more women moving into leadership roles in recent years, the data shows that is not the case. During the Women Who Lead interviews, I spoke to Deb Welsh, then CEO of the Academy of International School Heads, who noted that the percentage of women in Head of School positions has remained steady at 28-33% over the last ten years (during both her and Bambi Betts’ tenure as CEO of AISH).

While we may see more women than before in lower leadership positions, the results of the 2019 Diversity Collaborative Survey From Resistance to Sustainability and Leadership. Cultivating

20 | International School | Spring 2023 Leading, teaching and learning

Diverse Leaders in International Schools

state that ‘the pipeline is a trickle by the time you get to the upper end’ (Shaklee, 2019). The reality is that this is an ongoing problem in international, public and private schools around the world. Regarding international schools specifically, according to the same survey, ‘Whatever their definition, international schools are more likely to be focused on students demonstrating these attributes than on faculty/leadership reflecting and modeling these attributes.’ (Shaklee, 2019)

In the interviews I conducted, several key themes emerged as unique challenges for women pursuing a leadership role. Many readers will find these stories familiar. For those who are hearing these types of stories for the first time, you may want to seek out opportunities to dig deeper into why that might be. In this first article I’ll be highlighting some specific stories regarding the following four of our main identified areas of challenges faced by women in educational leadership:

• unconscious bias and daily microaggressions;

• physical expectations;

• linguistic expectations; and

• cultural expectations of ‘leaders’. All the following direct quotes are excerpts from the Women Who Lead Interview Series (Cofino, 2020).

Unconscious Bias and Daily Microaggressions

While many people might find themselves facing the problem of dealing with microaggressions in the work environment, women in leadership, and even more so women of color, often encounter particularly elevated levels of these negative interactions, since in their positions they so visibly combine the lightning-rod issues of gender and power dynamics. Junlah Madalinski, ES & MS Principal at Shutz American School, Alexandria, Egypt, described this clearly in our conversation: ‘What happens when women of color are in leadership positions is it makes them more visible. Instead of having yourself within your classroom, you have … a larger audience and microaggressions tend to play themselves out in that way.’

Women, and women of color in particular, no longer have the safety of ‘staying in their classroom’ once they take on the mantle of leadership. Being in the more public eye of a leadership position leaves them more exposed to these daily

attacks, unless there is action taken to improve the school culture. In fact, these kinds of microaggressions can begin even in the interview process. For example, Katie Wellbook, Assistant Principal for Academics at Suzhou Singapore International School, China, has heard comments like: ‘Your earrings are too big, they’re a distraction. Is that a power suit you’re wearing? Is it possible to be too ambitious?’ As she says, ‘women have to determine if these comments are misogynistic. Would they ask this to a man?’

While these kinds of comments might be an initial warning sign to determine if the recruiting organization is the right fit for the individual, we need to shift the culture to be unaccepting of this kind of language and commentary in any setting.

Physical Expectations

Many women also spoke about realizing that their actual appearance or stature had been an unspoken obstacle to securing a leadership position. When you combine physical size with heritage,

linguistic background, and other qualities subject to bias, a unique set of intersectional challenges is created. As Madeleine Heide, then Head of School at Lincoln American School, Buenos Aires, Argentina, highlighted in her interview: ‘I don’t have the profile of being a leader: I’m a woman, I come from Early Childhood, I’m not a white woman, I’m biracial, my heritage is Philipino and I claim my Philipino-ness. These are all “points against me” in terms of stepping up to the top leadership position. In my experience, people have stereotyped notions about what leadership looks like.’

Jasmeen Philleen, Assistant Principal at International School Manila, talked about the weight of responsibility she feels of not only representing herself as a Black woman, but also representing a long line of African American people. She is forced to carefully try to navigate the world knowing that when she’s new to a school, parents can be initially reluctant to have her as their child’s teacher – simply because of the color of her skin. While these stereotypes exist at all levels of education, it’s definitely still the exception to see many faces like Jasmeen’s in leadership positions in international schools. As a leader, she realizes that she’s unique, and this, as she mentioned, ‘makes me strive even harder to prove myself, to prove that I am worthy.’ Similarly, Tambi Tyler, Head of School at the Colorado Springs School, highlighted that she had ‘3 strikes [against her] coming out of the gate: as a leader, I’m young, I’m black, I’m a woman.’

Spring 2023 | International School | 21 Leading, teaching and learning

People have stereotyped notions about what leadership looks like.

Linguistic Expectations

Elsa Donohue, Head of School at Vientiane International School in Laos, realized early on that not only her gender, but her speaking accent got in the way of her being offered Head of School positions. During her Women Who Lead interview she points out that for ‘schools that were defined as being American schools, I didn’t potentially fit. Though that was never explained to me, I could figure it out.’ Elsa discovered that an unspoken requirement of speaking English with a stereotypically ‘Anglo’ accent was one of a number of factors that, particularly for women, might impede their progress or even tip the balance one way or the other during hiring.

Marta Medved, Head of School at Western Academy of Beijing, China, also feels that she’s categorized as ‘different’, not in terms of appearance, but of language background. She described experiencing this inequality in attending professional learning, ‘when you are surrounded by a group of 20 native speakers, and you’re the only second language speaker,’ noting that in these situations it might take longer to process in a second language.

Cultural Expectations

In fact, regardless of physical or linguistic conformity to expectations, women leaders with cultural, religious, or national backgrounds that differ from the standard face unique challenges as well. As Abeer Shinnawi pointed out, ‘for me as a hijabi, there’s an extra layer. There are always preconceived notions about what I will be like. I know automatically that they don’t get what they thought they were going to get when they see me.’ Being the only young Muslim woman in her school community, she always felt like she had to prove herself, and even among peers and colleagues, she always had to push against the perception of being a meek ‘wilting flower’ because of her hijab.

Many interviewees discussed similar stories of being treated differently

References

because of their background. Fighting against these stereotypes, particularly ones involving visible signs of cultural and/or religious affiliation, can seem like a never-ending battle. These serious issues are only the first of many which the Women Who Lead interviews have identified. An upcoming second article will discuss some of the remaining areas for concern, including

• perception (or reality) of lack of opportunities for women;

• exclusive networking practices among ‘traditional leaders’;

• impostor syndrome and double standards; and

• availability of mentorship and guidance. While it can be daunting to face the sheer number of obstacles confronting women leaders in education, sharing such stories and experiences might hopefully be a first step towards facing these formidable challenges. ◆

Kim Cofino

Kim Cofino

is

Founder and CEO of Eduro Learning: https://edurolearning.com

✉ kim@edurolearning.com

• Cofino K (2020) Women Who Lead Interviews. [Video Course]. edurolearning.com/women

• Shaklee B D, Daly K, Duffy L and Specker Watts D (2019) From Resistance to Sustainability and Leadership, Cultivating Diverse Leaders in International Schools. Results of the 2019 Diversity Collaborative Survey (DCS). Retrieved from: www.iss.edu/wp-content/uploads/DC_Report_Survey2019Results.pdf

22 | International School | Spring 2023 Leading, teaching and learning

Women leaders with cultural, religious, or national backgrounds that differ from the standard face unique challenges as well.

Spring 2023 | International School | 23 Leading, teaching and learning Personalised Digital Prospectus Open Events Event Follow Up Staff Recruitment Agent tool Make your school personal Personalised school admissions and recruitment “This is the future of school admissions.” UK boarding school Register to watch a demo kampus24.com

Strategic Planning for International Schools

By Jacobus Steyn

By Jacobus Steyn

The strategic plan has been the cornerstone of school development and improvement for a long time. If researched and written well, strategic plans provide a clear roadmap for international school heads and boards to navigate their school to the next development phase. However, strategic plans can also quickly descend into a ‘tickbox’ exercise and become irrelevant if not reviewed against the fast-changing international school landscape.

The isomorphic nature of international schools includes the familiar 3-year or 5-year strategic plan. A head of school joining a new school could expect either to find a strategic plan left by their predecessor or to be expected to develop such a plan: very familiar territory to assist with the smooth transition of leadership. The traditional strategic plan may include the following categories (and a very handy tick-box!):

However, in 2004 Mike Schmoker lamented the use of strategic planning for schools, explaining the rise and fall of the traditional strategic plan. He argues that the sheer scope and size of these plans and very handy ‘boxes’ for tick completion results in a plan with too many activities to monitor, initiate, and implement. There is no mention of ingraining the ‘new’ into the organisational culture. Schmoker commented on using strategic plans within a USA public school context. We know that international schools are very different types of institution; is there still a place in setting the vision for international schools with a traditional strategic plan? It depends. We know that although there are significant similarities between international schools, each school is on its own path in terms of growth and improvement. Different types of plan may be either more or less appropriate, depending on where the school is on its journey.

24 | International School | Spring 2023 Leading, teaching and learning

Goal Objective Action Steps Person Responsible Resources Needed Evaluation Timeline

3-year/5-year Strategic Plan

While the 3/5-year strategic plan may not be best suited for the vast network of a public school system, it certainly has a very clear benefit for international schools as a planning tool. Schools undertaking external accreditation for the first time will certainly benefit greatly from designing their strategic focus areas and school development plans from a 3/5-year strategic plan if this plan is built around the accreditation cycle and matched against the accreditation framework.

However, one pitfall to avoid is matching the plan against the immediate framework for the phase of the accreditation cycle. If we assume a Council of International Schools (CIS) Accreditation Framework, which has four focus areas or drivers (Purpose and Direction, Learning and Teaching, Global Citizenship, and Student Well-being), there are various ‘steps’ for each domain and driver. While ‘foundation’, ‘preparatory evaluation’, and ‘team evaluation’ may all have the same domains and drivers, the success criteria in each step show a clear improvement pathway. The 3/5-year strategic plan can be appropriately utilised to drive school improvement and development to ensure a successful accreditation visit.

Depending on the school’s starting point, one 5-year strategic plan to coincide with the accreditation cycle may be appropriate. Or two 3-year plans may be more suitable if organisational and institutional practices need to be shifted to meet the membership stage. [The membership stage section of the CIS Framework details the minimum requirements to be accepted as a CIS member school. The criteria become more intensive with the phases leading to accreditation.] As strategic plans tend to be linear in nature, it is crucial to build in a review of the plan should the school opt for this route for strategic planning purposes.

Iterative and Rolling Plans

In response to the linear nature of traditional 3/5year strategic plans, in the 1990s iterative plans were discussed as a means of establishing clear goals and resources over time, while promoting flexibility via an ongoing process to navigate the unexpected and capitalise on unforeseen opportunities (Chance, 2010). In 1991, the idea emerged of a rolling wave approach to planning (Knutson and Bitz, 1991). The philosophy underpinning this approach is that the path or journey may change, and planning should be adaptable to this. The analogy of a mountain climbing expedition is used. Thorough research and lessons learned from previous expeditions can secure a solid starting point, with clear approximations (not estimations) of the time and resources required to reach stage 1. As the journey unfolds, the expedition is ready to plan for stage 2. Once stage 2 is reached, enough information is available to plan for stage 3. Stages can be days or months, depending on the situation. (American Management Association, 1997).

Iterative and rolling plans seem very similar in nature. I think the key difference is where the school is on its journey. If a school is already established but would like to move in a certain direction, for example to become a trendsetter for Project Based Learning and Skills Based Assessments, but they are not there yet, then an iterative approach would be most appropriate. This type of strategic planning will allow for strategic goals to be set (establish best practices for Project Based Learning; Develop Skills Based Assessment protocols) and then a route card to be created to reach this goal. As a reflective practice is strategically employed along the journey, changes can be made to ensure the goal is reached to the required standard, incorporating new research or technologies while avoiding pitfalls.

Rolling plans become very interesting for well-established schools that focus on innovation and seek to remain relevant, building on their primary task. It is not surprising that rolling plans were discussed in Forbes’ Magazine Leadership Strategy section (Bradt, 2019). In fastchanging business environments, including international education, taking stock of progress and the relevance of goals every three or six months is ideal. One day per stock-take, as opposed to one week a year with traditional plans, not only saves time but also ensures an accurate representation of reality (the market) in planning.

For example, this planning

Spring 2023 | International School | 25 Leading, teaching and learning

A recent short survey from the Academy of International School Heads (2022) shows a very interesting picture of types of plan found in a number of international schools.

Courtesy of Antonio Patarozzi, Twitter (2013)

method can be handy for schools that identify as technology trendsetters. The emergence of META Quest could potentially have fascinating advantages for education.

Covid-19 taught all of us that the education dynamic could change overnight.