By Claire Cooper

By Claire Cooper

Many readers of International School will have positive and fond memories of George Walker, Director General of the International School of Geneva and subsequently of the International Baccalaureate, who died on 4 March 2022. What follows is taken from a contribution to the March 2023 IB Global Conference in Adelaide, Australia by Claire Cooper, George’s granddaughter and herself a graduate of the IB Diploma Programme.

My name is Claire Cooper. I’m from Buckinghamshire in the UK and I’m 22. I studied the IB Diploma from 2016 to 2018, from the age of 16 to 18, during my sixth form at a grammar school after completing my GCSEs rather than taking A-Levels.

My experience of the IB was rather different from that of many IB students. Instead of studying it at a private school, I didn’t have to pay, and it was only run in my school at the choice of my Headmaster, Mr Stephen Box. He thought the IB was an incredibly valuable alternative to the usual three to four subjects offered by A-Levels. However, my school still offered A-Levels as well, and in a year group of around 200 people, only 23 of us chose to do the IB. Classes varied in size from 1 person to 23, with the average class size being around 8 to 10 people. We were still offered a variety of subjects, though probably not

as many as international schools offer. The subjects I chose were Higher Level English, History and Global Politics, along with Standard Level Biology, Maths Studies and Italian ab initio. I was in the first and last year group to be offered the Global Politics course as, unfortunately, due to a lack of demand and the high fees for the school to pay, I was the last year group to be able to study the IB at Sir Henry Floyd Grammar School.

So, I had to choose between A-Levels and the IB Diploma at the age of 16. Many of you, being such advocates for the IB, may think that’s a straightforward choice. However, for me it came down to the subject matter and one particular family member. The family member in question was my Grandpa. While I knew he was an extremely interesting and intelligent man, at the age of 16 I hadn’t yet asked him enough questions about his career to understand what he did. I knew he and my

Granny lived in Geneva for a while when I was little, but I didn’t realise that was because of work.

My Grandpa was George Walker, director general of the IB from 1999 to 2005. You may think how on earth did she not know about his career? But he was a modest man, and it took a lot of questioning to prise out of him any sort of admission to his vast achievements. I didn’t even know he studied music in Cape Town until I Googled him. Cutting back to 2016 when I was faced with this crossroad decision of A level or IB – obviously he was well aware of the merits of the IB, beyond my knowledge, and therefore, in a very kind way, showed his determined interest in my taking the IB route.

I chose to take the IB partly because of his high regard for it, but mainly because of the incredibly interesting content of the Global Politics course. Studying History at GCSE had sparked an enthusiasm of mine for international affairs and so I was keen to study Politics in sixth form. For those who aren’t familiar with A-Levels, the Politics A-Level comprises one year studying the British Parliament system and one year studying the American Congress system, with a potential trip to Washington: the only selling point of this course is that school trip to Washington.

On the other side, IB Politics divided into themes such as conflict, security, development, and human rights. In these we were free to pick our own case studies from anywhere in the world, and our class was only 9 people. It was an easy sell to me, and funnily enough the conflict, security and development themes ended up titling the Masters that I completed in September last year following my undergraduate degree.

My case here shows that the IB is fascinatingly global, not only in its reach but also in its content. When studying the British Empire as part of IB History it was the first time that we were taught

the severe negative elements of it, and encouraged to question and debate matters of historical and current affairs. In a safe, small, and respectful environment we learnt the valuable skills of critical thinking and not accepting only one narrative.

My experience links with the overall theme of this conference. Not only were people who would not be able to study the IB at international schools due to the fees and location able to study it at my school; the content we learnt was far more diverse than any I have heard from A-Level students. This inclusive atmosphere set the tone for a crucial development stage in teenagers and made me far more culturally aware and engaged in trying to make the world a better place, also a belief I learnt from my Grandpa.

The impact the IB has had on my current and future career path is endless. For starters, when I went to university I studied History and International Relations, essentially going from 6 subjects to 2, when most in England go from 3 to 1. Additionally, I studied Middle Eastern politics as a part of this, while many chose domestic or European topics. I had learnt about Europe for a while when studying for my GCSEs, and so learning about Vietnam and Asia during IB studies opened my eyes to the cultural differences and the vast histories to be learnt about the entire world.

While I was studying the IB and at university my Grandpa read pretty much all of my essays. I wasn’t aware until he died, and we received messages of condolences from various important people, that he had passed some of these on. His pride in me is part of the reason I am here speaking today.

The IB also gave me a head start at university in balancing workload. After completing 17 IB exams in 2 weeks, having 3 university exams in 1 week was an absolute breeze for me because nothing could be worse than 3-hour History and Politics exams in the morning and

then Italian or Biology exams starting 30 minutes later. I have become an efficient reader and worker, to the annoyance of my partner at times, but this will benefit me and my career at PricewaterhouseCoopers where I am starting full-time as a research consultant in September. The title of my PWC job is even relevant to the IB. The IB taught me to love learning and research. Every summer of university and during term time too I undertook research internships because I simply didn’t enjoy going months without challenging my brain and learning something new. The whole reason I am becoming a researcher is because I will now be paid to learn; to me this is the ideal job.

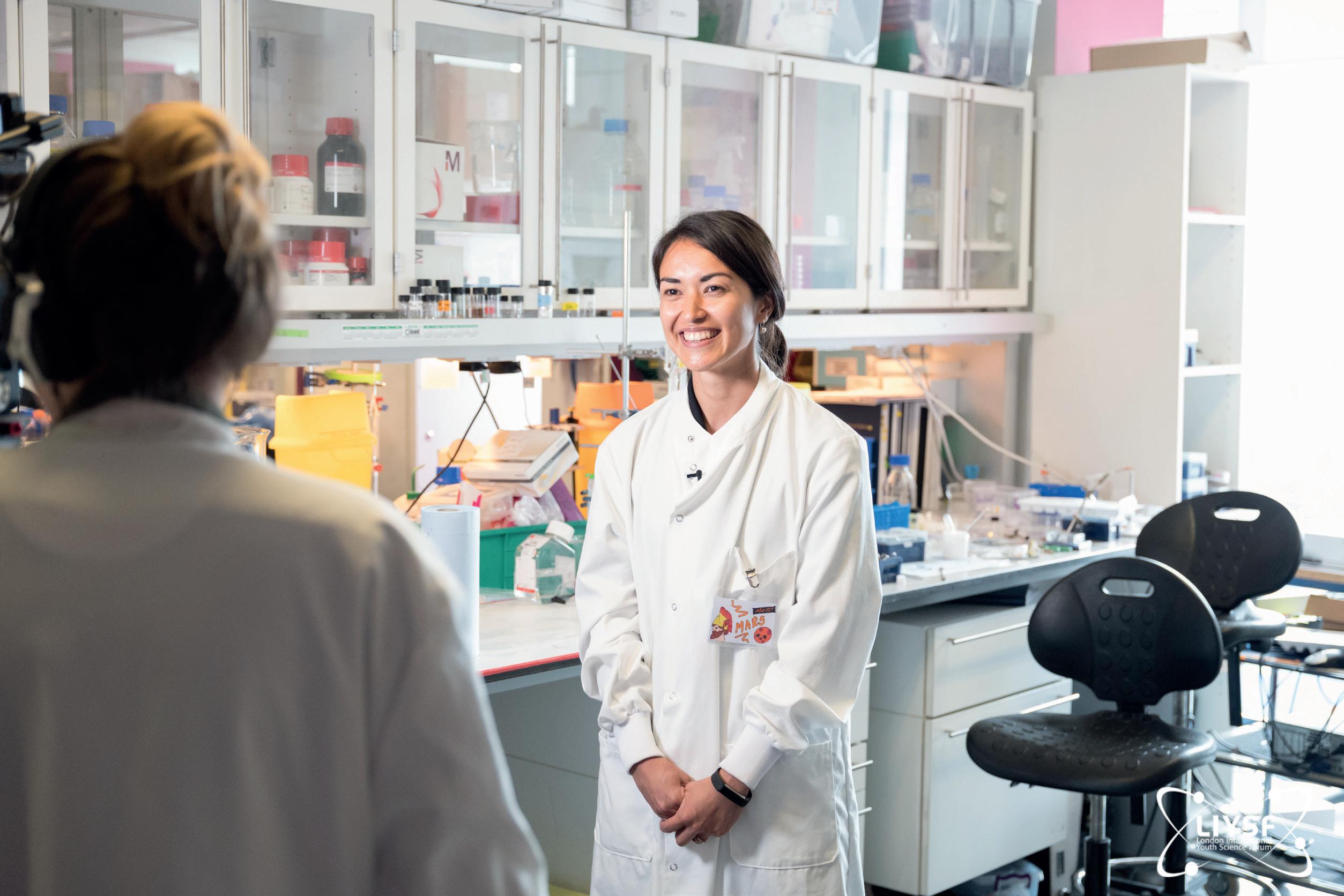

Before concluding I would like to just remember my Grandpa a little more. As mentioned on the IB website, my Grandpa had many interests. My brother, cousins, extended family and I are showing aspects of each of these. Only yesterday I attended a concert where his nephew played as Lead French horn for Adelaide Symphony Orchestra. Meanwhile my brother is spending this week in Switzerland as part of his career in science at the pharmaceutical company Roche. Music, science, education, and international compassion will remain an important part of our family.

I found it a very funny coincidence that I happened to be in Adelaide, during five months travelling with my partner, in the right month for this conference, and also almost exactly a year since my Grandpa died. In fact, this week it is a year since his funeral – so thank you again for hosting me so that I am able to commemorate him not just with our family but also with his other devotion, education. I would also like to take this opportunity to thank all of the IB community, students and teachers, past and present who sent such kind messages to my Granny and our family, remembering their stories with him and reminding us what a truly wonderful man we were lucky to call Grandpa. ◆

Claire Cooper joined PricewaterhouseCoopers as a research consultant in September 2023, having successfully completed the IB Diploma at Sir Henry Floyd Grammar School, UK before moving to the University of Exeter, UK where she completed a BA in History and International Relations, and an MA in Conflict, Security and Development ✉ clairecooper.cooper@gmail.com

The impact the IB has had on my current and future career path is endless.

Adaptive, baseline assessments from Cambridge CEM are used by schools in over 109 countries to empower teaching and help students reach their potential.

Cambridge Wellbeing Check (for 7 to 18 year olds)

Cambridge Primary Insight (for 5 to 11 year olds)

MidYIS (for 11 to 14 year olds)

Yellis (for 14 to 16 year olds)

Alis (for 16 to 19 year olds)

“We have found that Cambridge CEM’s data helps us to develop informed teaching and learning interventions. This has lead to better exam results.”

Flexible test your students when and where you want to

Time-saving digital assessments and automatic marking

Quick each assessment takes only one lesson

Student-friendly enjoyable and engaging for all ages

Adaptive assessments challenge students appropriately

I doubt anyone reading this article woke up this morning thinking about regionalization. But even if you didn’t, it is still affecting you. This third article in a series exploring changes to international education and looking to the future (see Summer 2022 and Autumn 2022 issues of International School for previous articles) considers a subtle but significant change happening around us, and one that will affect us as international educators.

What is regionalization? In the context of this discussion, regionalization is a process of moving away from global trade and politics and towards a specific region or bloc. This drift away from globalization is not the sort of change that grabs headlines, so you may not have noticed it. But globalization, as measured by global trade, is slowing and possibly even flatlining. Meanwhile, as the Economist magazine summarized in 2019, an ‘evolution of a new world order – a fully multipolar world composed of three (perhaps four, depending upon how India develops) large regions that are distinct in the workings of their economies, laws, cultures and

security networks – is manifestly underway’. Four years later, Covid and the war in Ukraine have accelerated these forces. Today governments, and to a certain extent companies, are worried about supply chain resiliency and security as much as they are about cost. Examples of this include Russia and China officially expanding their trading relationship/bloc, and the US having just enacted the ‘Chip Act’ to limit Chinese access to American technology.

As international educators, we should not underestimate the importance of commercial trade. When groups of people exchange goods and services, they develop cultural connections and normally understand each other better. Developing a shared understanding between groups is, of course, one of the tenets of an international education. If global trade changes, international education will as well. Furthermore, strong arguments can be made that globalization and interdependent trade networks have made the world safer: trading nations have more to lose if they go to war. But, as evidenced by the war in Ukraine, major conflict between different countries is back.

The idea of ‘becoming a global citizen’ will not be universally accepted as a good educational outcome.

James MacDonald is Director of the International School of Brussels, having previously held posts including Head of School at NIST, Bangkok and Yokohama International School, Japan.

✉ james.w. macdonald @gmail.com

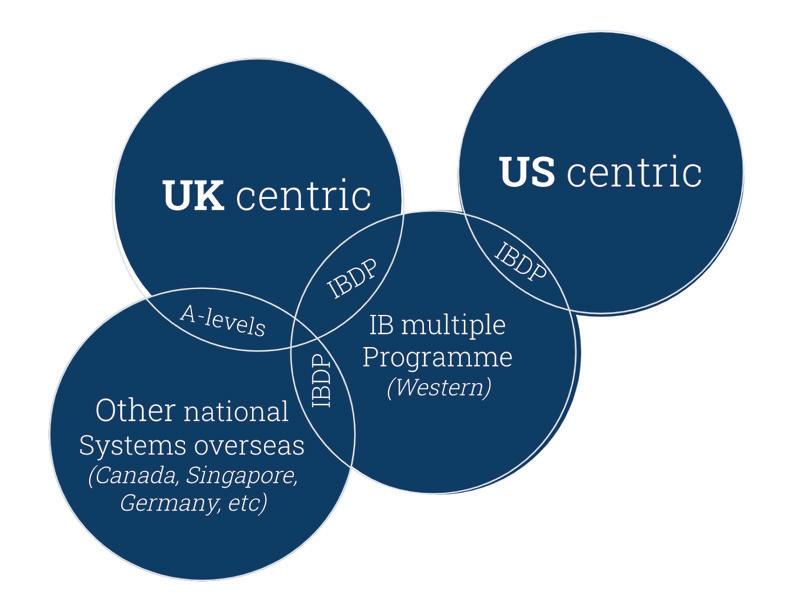

Like regional trade blocs within the global economy, international education has its own clusters. (See figure showing a Network Clustering of International Schools).

This is a big topic and a short article, but to briefly illustrate this point, consider professional learning. Educators in each of the clusters in the figure tend to gravitate towards their own conferences and training. However, if schools offer the same curriculum (such as the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme, IBDP) then teachers from different networks are likely to interact. Otherwise, they are unlikely to share professional development. The reality is that different curriculum types of international school generally do not need each other, just like countries are deciding they do not need countries outside of their own bloc.

You will also notice that, within this discussion, two of the biggest circles in the figure represent national Western curriculum models. Yes, these are national approaches to curriculum, but American and British overseas schools almost always have international elements of their educational programme so I include them. Some argue that the IB is one of the few ‘truly international’ curricula. But, as others have pointed out before me, the IB’s origins are Western as all four IB programmes (Primary Years Programme, Middle Years Programme, Career-related Programme, Diploma Programme) emerged from Western thought and values. International education may not be a national curriculum, but it largely remains a Western bloc education.

Incidentally, referring again to the figure, in many large cities around the world with international schools we see a similar pattern emerge: two or three leading schools representing the major ‘international’ curriculum offerings, then a mixture of smaller, ‘second tier’ schools sometimes offering different national curricula. Things tend to evolve a little like a shopping mall with a few big, well-branded anchor stores complemented by a range of smaller offerings. Market forces shape international education in many ways, and changes in trade patterns will impact us in a number of respects.

Demand for a greater balance between regional and global education

Regionalization is also a mindset and, as its popularity grows, we can expect parents and local governance to insist upon more regional and nativist elements within an international school’s learning programme. Graduates of schools outside of the Western bloc are more likely to consider regional universities (especially as non-Western universities improve in global rankings) instead of only Western ones. Related to this, anticipate that international schools will offer more bilingual programmes, especially in the lower grades.

The idea of ‘becoming a global citizen’ will not be universally accepted as a good educational outcome. Instead, expect to see more missions reflecting a balance between global citizenship and local values. This is part of the overall transition of international schools towards becoming more like regular independent schools. More people will refer to international education as Western education, especially as divisions between regions grow; not everyone will be interested in that for their children. Globalist will equal Western bloc.

Given the overall growth of international schools, it makes sense that bigger clusters (eg IB, US and UK) within international education will become increasingly siloed and independent of each other. Without an explicit effort to connect people across school clusters, international educators may start acting more like educational regionalists existing in echo chambers of their our making, closing off from each other and looking inward.

International education, from its genesis, was designed to be a force for peace. Interdependent global supply chains and the rise of democracy helped promote peace between nations. Regionalization presents a dangerous phase of global politics. If things continue down their current path, this generation of international students could experience a major war between nations and, possibly, between regional blocs. International educators need to return to our roots as a uniquely positioned powerful force for peace.

The shift to regionalization offers no dramatic elements that drive news cycles. But this is a big shift, and we will see its effects. ◆

Thousands of students this year were able to take their International GCSE exams onscreen and the number of schools adopting onscreen assessments for high stakes exams has doubled in the last year with this trend looking set to continue. One of the benefits of allowing students to take their exams online is that it is in a format that is familiar to them. It provides them with the ability to move easily though the question paper and revisit questions if they have time.

Sitting their exams in this format is incredibly natural to them so by adopting this approach as a school, you are meeting your students where they are technologically.

90% of students who sat their exams onscreen in 2022 said they wanted their school to offer more onscreen exams in the future. Qatar International School were one of the trailblazer schools adopting onscreen assessment and their students said:

I am really reliant on computers in my daily life.

I type a lot faster than I write.

I can move back and forth between answers really quickly and amend answers.

100% of teachers who registered students for onscreen assessments in 2022 registered students for 2023 onscreen exam series too. They find it easy to organise and manage, it boosts students’ confidence, and they find the support they receive from Pearson is excellent. Wayne Ridgway the Head of Senior School at the British School of Bahrain says,

It’s been a fantastic experience for us as a school and also for our students who were absolutely delighted to work in a way that felt most comfortable to them.

Whilst the feedback we have received is positive for onscreen assessment, we recognise that this may not suit every student’s style and preferred choice of taking high-stakes exams and a paper-based option might be the better choice. Onscreen assessments are the same as paper-based assessments with the same questions being answered under exam conditions, the only difference onscreen is that students type their response in the onscreen platform. Students who choose to complete their exams onscreen have access to the accessibility features and tools available in the onscreen platform.

If you would like to start onscreen assessment but are unsure a hybrid approach where you have a blend of onscreen and paper assessments is a good alternative. A hybrid approach allows you to manage the transition and provide students with the option that best suits their style of taking high-stakes exams.

Onscreen Assessment has been tried and tested and Pearson have been delivering robust secure onscreen assessments for the last 10 years.

To find out more, visit: www.pearson.com/international-schools/onscreen-assessment

Students from around the world have been sitting their high stakes exams online this summer.

There is a very well-used openended science activity, often found in primary schools, whereby students are given a stack of cards showing, for example, different types of animals and are asked to work in groups to ‘sort’ them. No other direction or information is given. The results are always interesting and varied: one group may sort by the number of legs (grouping horses, dogs and turtles into one group, kangaroos and humans into another); a second may sort by colour (grouping crocodiles, turtles, parrots and grasshoppers together) while another may assume the teacher is looking for ‘scientific’ classification, and sort the reptiles, mammals and insects into distinct groups. None of these students is incorrect. They are each able to justify the choices that have led to the classifications made; the features that stood out to them are the ones that were used to categorise the animals.

This activity could just as easily be used for the classification, or categorisation, of international schools; as stakeholders, we can categorise the schools based on the features that are of significance to us. For example, in this magazine in 2022, James MacDonald suggested that types of international schools could be attributed to

ownership of the schools, using ownership to classify three types of international schools as ‘traditional’ (the historic, not-forprofit, parent-governed model), ‘corporate’ and ‘single private owner’. Another commonly used term to categorise schools is ‘tiers’, more specifically Tier 1, Tier 2 and Tier 3, though there is no agreed definition for this terminology which, again, depends on the stakeholder discussing the school. For parents, it may be tuition cost (the higher the tuition fee the higher the tier), university entrance and general reputation. For teachers it may be salary, working conditions and importance placed on professional development. The use of ‘tiers’ has no official status, though they are often used by schools in their marketing (especially those that consider themselves to be in Tier 1).

Perhaps the most ubiquitous of the international school typologies, at least in academic research, is that created by Hayden and Thompson (2013). Their ABC typology is based on the raison d’être of each school: Type A are schools created to cater for those expatriates who cannot access their local education system; Type B have been established with an ideological view to develop ‘global peace and understanding’; Type C are largely for the

local socio-economically elite students who seek a perceived better education than their local system can provide. Since 2013 there has been discussion, including by Hayden and Thompson themselves (2018), as to whether this typology continues to be appropriate in today’s international school sector.

Naturally, there is also the option to categorise international schools by curriculum. British, American, Australian, International Baccalaureate (IB) Diploma Programme (DP) (and Middle Years Programme (MYP)/Primary Years Programme (PYP)) are just a few examples of curriculum to be found in the international school sector. As the diversity of the student body has changed over recent years, however, so has the diversity in curriculum, especially among those schools that are nationally-affiliated (such as British or American). Not only is this diversity in the curriculum offered across different schools, but also within schools; there has been an ‘evolution in how nationally affiliated schools present their curriculum model’ and there is now ‘evidence to suggest that internationalising the national is present in many’ international schools (Pearce, 2023). For this reason, in a recent article I presented

an emerging type of international school: the internationally-national school.

The internationally-national school is a school that remains grounded in its national curriculum or ethos, yet is still an international school. The national affiliation might be in the name of the school, how the school organises itself (such as nomenclature for leadership), the school’s day-to-day functioning (for instance if the students are organised into houses) as well as in the curriculum basis for learning. However, there is also certainly a ‘more nuanced and complex’ (Pearce, 2023) group of schools than those that purely align themselves to one homogenous category of school. For example, in my research I found schools that presented their curriculum in a number of ways that deviate from a single national curriculum

NATIONAL AFFILIATION

(see table). Each of these schools includes their national affiliation in their name or as part of their marketing on their website.

The schools included in the table, and presumably many other internationallynational schools, were once created for the globally mobile citizens of that country who sought an education for their children that would allow them to return for study to their home countries. These schools have now become institutions that are open to students from all over the world, including host country students, and incorporate an international dimension while remaining aligned with one national affiliation; ‘they have moved beyond both their “national” and “international” labels to create a new model of international school, the internationally-national school’ (Pearce, 2023).

CURRICULUM

In a further fork in the road of international school development, the reversal – or at least slowing – of globalisation may have an impact on how international schools (and within this grouping, internationally-national schools) may develop and thrive in future (see MacDonald, 2022). This could again change not only the way in which schools define themselves, but also in how they are defined by others. Categorising schools will become increasingly difficult, and typologies that remain stagnant may render themselves inadequate; this is therefore an aspect of international schools that should be regularly reviewed. As stakeholders, however, we will – like primary school students grouping animals – continue to define school types in a way that is important to us and our needs at the time. ◆

British based or IBDP Students may choose which pathway to take

US

IB PYP and US based (Common Core and American Education Reaches Out {AERO})

Canadian PYP

US based (Common Core and AERO)

US based school diploma and/or IBDP

Students may choose IBDP in addition to the school diploma

Canadian (Prince Edward Island)

• Hayden M and Thompson J (2013) International Schools: Antecedents, Current Issues and Metaphors for the Future. In: R Pearce (ed) International Education and Schools : Moving Beyond the First 40 Years. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [pp3–23].

• Hayden M and Thompson J (2018) Time for new terminology. International School. Autumn: p3.

• MacDonald J (2022) Inflection point? Exploring the contemporary purpose of an international education. International School. Summer: pp4–5.

German school abroad German

Australian PYP underpinned by Australian curriculum

Canadian (Prince Edward Island) and US based (Advanced Placement) Students may choose AP classes in addition to Canadian diploma

German and US based Students can graduate with two qualifications: German International Abitur (DIA) and diploma from state in which school is located

Year 6-8 Australian curriculum Year 9-10 British based (IGCSE)

Australian curriculum Higher School Certificate or IBDP Students may choose which pathway to take

Sarah Pearce is currently completing a doctorate in Education, having worked in leadership of schools in Dubai, Malaysia and, until recently, the USA.

✉ sktp20@bath.ac.uk

So, here’s a provocation: the how of learning is as important as the what. Let that sink in for a moment... More precisely, how we learn knowledge and skills as children affects how we understand problems and their solutions as adults.

Today, we face a host of incredibly complex problems: resources, climate, pollution, conflict, migration, global economic and digital poverty. The problems appear endless and often overwhelming, but rarely are they, and their solutions, viewed as interconnected. More alarming is our collective passivity and reliance on an ‘expert in the room’ to tell us what to do. In the context of my provocation, the suggestion is that the expert is a proxy for our caricature of the classroom teacher. An incarnation of Dickens’ Gradgrind, with us cast as the ignorant vessels waiting to be filled with knowledge and given the answers. A learned passivity at a time when dynamic collective action is desperately needed.

The industrial education model has always been a trade-off between the measurable apparent in knowledge dissemination and its measurable regurgitation, and the more nebulous development of human agency and adaptive skills. It is a model that prioritises didactic teaching and requires compliant passivity from the learner. However, today technological advances have expanded the range of this knowledge to a point where we are now becoming overwhelmed by its volume. Then add to this the rapid emergence of generative AI and machine learning, which challenges the primacy of the three ‘Rs’ of traditional cognitive pedagogy. Unfortunately, educational change is not keeping pace with these advances, meaning we have done little to promote more future-relevant modes of cognition such as critical thinking and learner agency (Bandura, 2000). Is it any wonder, therefore, that many think-tanks identify a global deficit in adaptive expertise? (Carbonell et al, 2014; OECD, 2019).

Here, I want to suggest that our passivity is a product of the ‘transmission’ model of learning [the how] (Tishman et al, 1993),

which is in turn compounded by a continued emphasis on a narrow view of cognitive intelligence [the what]: the upshot being what Paolo Freire identified as a ‘banking’ model of education, which sees knowledge as ‘a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing’ (Freire, 2018). In other words, industrial education institutionalises a profit-and-loss scenario in which learners develop a cumulative relationship with both knowledge and the process of knowing. In fact, much in education borrows from language from the traditions of economic theory. For example, education theory has adopted the term knowledge economy (Chorev & Ball, 2022), and in turn this has led many to see learning ‘stuff’ as a cumulative activity, which subsequently relies on metaphors such as growth and wealth to describe a learner’s development.

Traditional economics, however, is being significantly critiqued by theories such as circular cumulative causation (Donaghy, 2022) and circular or donut economics, which offer powerful alternative ways of understanding the interrelated complexities of economics (Brennan et al, 2015). In this article I advocate for using these new analogies as we try to reimagine education for the future. Put simply, I argue that the circularity offers a more regenerative view of education, one that rebuilds both the how and the what of learning so that we can educate tomorrow’s learners to move beyond the learned passivity and inertia affecting many of our generation.

At Education in Motion (EiM, 2023a), we have examined how best to address educational regeneration. To do this we began by considering how to redesign the cluttered linearity of the traditional curriculum and shift from a cumulative approach towards more circularity. Much of the research and development for this grew from an SE21 STEM high school concept developed between 2019 and 2021 (EiM, 2023b). In that work we created a literacies framework, which subsequently has informed two school models within the EiM network: Green School International and School of Humanity. Each curriculum took the principle of literacies from the SE21 model and created independent versions that reflect their own interdisciplinary approaches to knowledge and problem-based learning design.

For School of Humanity (2023), the Human Literacies Framework (HLF) addresses the problem of complexity in learning design by establishing a model that acknowledges two

we can educate tomorrow’s learners to move beyond the learned passivity and inertia...

fundamental principles of future-ready education. First, the HLF recognises the iterative nature of knowledge and skills acquisition, and the regenerative reality of a challenge-based curriculum.

Second, School of Humanity’s framework articulates conceptual domains and knowledge dimensions in ways that actively prioritise an interdisciplinary pedagogy. It is, however, important to acknowledge that the literacies model is not intended as a replacement for well-established disciplinary traditions; rather it represents a reengineering of such knowledge in ways that recognise new knowledge as always emerging across disciplines. Green School International takes a regenerative approach to accelerate systemic change in education. Its aim is to better equip learners to meet the needs of the twenty-first century than is the case with the use of traditional approaches. The model ensures curriculum convergence across Green School’s global network by mapping learning outcomes to internationally recognised qualifications frameworks whilst embracing divergence based on each school’s indigenous context. The foundation of the curriculum is articulated in the Green Literacies Framework (GLF), which acknowledges established disciplinary learning whilst anticipating a more interdisciplinary future. Together with the Green Skills and I-RESPECT values, Green School International’s curriculum appreciates what knowledge and skills traditions we must have while anticipating how new knowledge and skills priorities are influencing how our future evolves.

It goes without saying that by the end of school most of us consider ourselves to be literate. This, however, is an outmoded view of literacy. Today, society requires fluencies beyond traditional reading, writing, and mathematics. The advent of ubiquitous technologies and the proliferation of text forms means we must be literate across a wider array of textual, aural, and visual

media. Additionally, we need a more sophisticated understanding of numeracy and its application because everyday lives are dominated by data.

More innovative recent approaches to learning design often use one of three common concepts when describing the what of learning: competency, capability, and mastery. And while an audit of these terms reveals little agreement on what each one describes, one way of understanding them is to see each on a skills continuum. At one end there’s competency, with capability somewhere in the middle and mastery at the other end. Seen this way, I would argue, competency somewhat underplays the depth of knowledge, skills, and dispositions acquired at school whilst mastery is maybe too presumptuous for the high school learner, and capability perhaps too suggestive of a deficit view of knowledge and skills accumulation.

Both School of Humanity and Green School International see literacies as an effective way of avoiding this continuum in allowing for varying degrees of fluency and sophistication across disciplinary knowledge, adaptive skills, and environmentally-focused dispositional traits. Furthermore, the interpretation of literacies is founded on three powerful theoretical concepts that readily align with a futurefocused view of education provided by each school model.

The first of these theoretical influences is ‘critical literacy’, which describes a key skill developed by students using Freire’s ‘critical pedagogy’. Seen this way, literacy offers ‘an important strategic, practical alternative for teachers and students to reconnect literacy with everyday life, and with an education that entails debate, argument, and action over social, cultural and economic issues that matter’ (Luke et al, 2009). In other words, critical literacy equips learners with a sophisticated awareness of the political realities of both how they learn and what they learn in a ‘post-truth’ era. Such an approach not only nurtures the cognitive skills required to navigate ideological and economic debates, but also builds the agency required to create impactful solutions.

A second theoretical inspiration for the literacies draws on Cope and Kalantzis’ theory of ‘multiliteracy’ developed with the New London Group in the 1990s (New London Group, 2023). Multiliteracy represents ‘a set of supple, variable communication strategies, ever-diverging according to the cultures and social languages of technologies, functional groups, types of organization and niche clienteles’ (Cope and Kalantzis, 2009). It is essentially the ability to read across disciplines and media using various interpretative methods and communicative tools. Significantly, multiliteracy is interdisciplinary in nature and thus highlights for learners the permeability of disciplines.

The final theoretical foundation combines three inter-related concepts that have emerged in regenerative educational theory over the last thirty years. ‘Environmental literacy,’ ‘ecological literacy’ and ‘ecoliteracy’ are often used interchangeably to describe educating for a more environmentally aware and agentic citizenry. Again, the term literacy emphasizes an interdisciplinary approach that is ‘open and inclusive, and... involves the overlap and interaction between subjects of study... and ways of knowing’ (Berkowitz et al, 2004). Again, being ecoliterate means having fluency across traditional and emerging knowledge domains, twenty-first century adaptive skills, and environmentally cognizant dispositional traits.

To address the learned behaviours under scrutiny in this article, education must provide environments and experiences that promote agency, collaboration, and interdisciplinary approaches to knowledge and skills development. Our young learners today need the confidence to constantly ‘road test’ their burgeoning knowledge by applying it to immersive, real-world challenges rather than the abstract scenarios provided in a traditional classroom. Moreover, future learning must nurture adaptive skills fluency by providing far more authentic experiential opportunities beyond the walls of the campus.

One example of this approach is in Green School Bali where students objected to the use of polluting diesel fuel by the school bus and sought to find an alternative. While exploring the interconnected elements of the issue they discovered that many local restaurants disposed of used cooking oil in the nearby village’s open sewage system. Both activities were having a detrimental impact on the local environment. By examining the complex interrelationships of waste disposal and recycling science the students were able to design a solution to both problems. The project culminated in what has become known as the Green School Bali Bio-Bus (Green School, 2023). Students now collect used cooking oil from local restaurants and use a student-designed recycling process to recover the cooking oil so it can be used to fuel the school bus. The project was student-driven and required impressive academic research and community negotiation skills to develop the concept and bring local restaurant owners onboard. Importantly, the project demonstrated the regeneration of existing technical knowledge to create a real-world solution to a local environmental problem.

But why bother trying to systemically change the how and the what of education?

Curriculum built around a literacies framework anticipates the dynamism of modern learning and the fluid nature of emergent

knowledge dimensions and adaptive skills development in a rapidly changing world dominated by technology. In Green School International and School of Humanity there is an understanding that powerful learning arises by ‘weaving between different knowledge processes in an explicit and purposeful way’ (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009). To this end, the literacies move beyond the limitations of the competencies-capabilities-mastery continuum and a cumulative view of knowledge by recognising the regenerative reality of human knowledge and the dynamic nature of adaptive expertise. As a concept the literacies offer students a timely and authentic interdisciplinary learning experience that builds adults who will not learn the passivity and inertia that has hamstrung our generation. EiM’s development of literacies frameworks, in partnership with Green School International and School of Humanity, represents a judicious regeneration of traditional schooling’s value proposition, and offers a compelling invitation to reconsider education’s higher moral purpose in these testing times. ◆

• Bandura A (2000) Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 9(3): 75-78.

• Berkowitz A R, Ford M E & Brewer C A (2005) A framework for integrating ecological literacy, civics literacy, and environmental citizenship in environmental education. Environmental Education and Advocacy: Changing perspectives of ecology and education. 227: 66.

• Brennan G, Tennant M & Blomsma F (2015) Business and production solutions: closing loops and the circular economy. In: Kopnina H and Shoreman-Ouimet E (eds) Sustainability. London: Routledge.

• Carbonell K B, Stalmeijer R E, Könings K D, Segers M & van Merriënboer J (2014) How experts deal with novel situations: A review of adaptive expertise. Educational Research Review. 12: 14-29.

• Chorev N & Ball A C (2022) The Knowledge-Based Economy and the Global South. Annual Review of Sociology. 48: 171-191.

• Cope B & Kalantzis M (2009) ‘Multiliteracies’: New literacies, new learning. Pedagogies: An International Journal: 4(3): 164-195.

• Donaghy K P (2022) A circular economy model of economic growth with circular and cumulative causation and trade. Networks and Spatial Economics. 22(3): 461-488.

• Education in Motion (2023a) https://www.eimglobal.com/

• Education in Motion (2023b) https://www.eimglobal.com/se21-education

• Freire P (2018) The Banking Concept of Education. In: Thinking about Schools (pp 117-127). London: Routledge.

• Green School (2023) https://www.greenschool.org/bali/support-us/biobus/

• Luke A, Woods A, Fisher D, Bruett J & Fink L (2009) Critical Literacies in Schools: A Primer. Voices from the Middle. 17(2): 9-18.

• New London Group (2023) https://learning-theories.com/multiliteraciesnew-london-group.html

• OECD (2019) OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030: Learning Compass 2030. Paris: OECD

• School of Humanity (2023) Curriculum Guide. Available from https://online. flippingbook.com/view/956322525/8/

• Tishman S, Jay E & Perkins D N (1993) Teaching Thinking Dispositions: From transmission to enculturation. Theory into Practice. 32(3): 147-153.

Dr Kevin House is Group Education Futures Architect for Education in Motion (EiM). ✉ Kevin.House@eimglobal.com

The British International School, Ukraine (BISU) is an inclusive international community established in 1997 as the first school to offer a British style education in Ukraine. Catering for children aged 3-18 years old via IGCSE, IBDP and A-level qualifications, this is the story of BISU navigating its way through the ongoing war since the outbreak of the invasion, and its vision for future development.

Iam part of a generation that was fortunate to grow up without experiencing war first-hand. Our understanding of military conflicts came solely from books, films, documentaries, history lessons, and the poignant accounts passed down by our grandparents. We used to naively believe that we might be spared from such a dreadful fate... until that late February morning when we awoke to the ominous thunder of war on our doorstep. Everything changed in an instant.

Certainly, our school’s Senior Leadership Team had made some prior arrangements. In January, a few of our international educators had heeded the advice of their embassies and returned to their home countries, transitioning to online teaching,

while others, including local staff, carried on with their regular on-site duties. Yet nobody can truly be prepared for war, and that was the first lesson I learnt immediately. The best we could do was to respond swiftly, support one another and, above all, remain calm. It brought to mind my late father’s words; a civil pilot, he always said, ‘It is panic that kills first’. We sprang into action and sent out an email to parents, students and staff, notifying them about temporary closure of the school.

In the early stages of the invasion, we took decisive measures to assist both BISU and the wider community. The Board prioritised evacuating people, amid damaged roads and city attacks. Ensuring the safety of BISU staff and their families was our main focus. We also opened our school facilities to provide crucial aid, such as food and shelter, to those in need. Some of our colleagues and alumni bravely joined the Ukrainian Armed Forces, and we made sure they had the necessary safety gear and IT equipment.

Within a span of two weeks, we found ourselves scattered across the world. Each day, we asked one another, ‘Where are you? Are you safe?’. Losing contact with

one of our teachers caused great concern, and our relief was immense when we eventually located her.

BISU didn’t back down; instead, we forged ahead with the development of our school. Leveraging the systems we built during Covid, within just two days we merged all three campuses in Kyiv and Dnipro into a unified virtual school. We rescheduled lessons by utilising available and secure teachers. Thanks to tremendous support of our global partners, our students experienced uninterrupted education. Not stopping there, our Primary and Secondary curriculum received a significant boost through valuable collaboration with renowned institutions.

As a result, we successfully wrapped up the 2021-2022 academic year. The BISU community came together online and celebrated the accomplishments of our IB Diploma and Ukrainian certificate graduates. Though the first four months of the dreadful conflict were now in the past, what lay ahead was uncertain.

With the substantial drop in student enrolment, the school Board faced one of the toughest decisions they had ever encountered. However, on 1 September 2022 our two schools in Kyiv and Dnipro courageously resumed in-person operations, while the third campus remained closed. To make it happen, we transformed our basement facilities into secure air alert shelters, fully equipped with essential amenities, including wifi and cots for the youngest students. In adherence to wartime policies, our children and teachers display self-discipline and bravery whenever they hear air raid warnings. They promptly move to the shelter to continue their lessons in safety. It has become a part of their ‘normal’ routine now.

Since mid-October 2022, Ukraine’s infrastructure has been under relentless attack with massive missile and drone strikes. During that period, Ukrainians had to endure plenty of hardships, with no electricity, internet connection, or heating. One of the most challenging tasks was acquiring a generator to cope with

the winter season. Still, we managed to overcome these obstacles.

Of course, studies at our school have undergone changes to adapt to the current situation. At BISU, we offer a bilingual programme, blending the strengths of the British and Ukrainian educational systems. Our Ukrainian teachers work on-site, focusing on the local curriculum, while our international teachers handle British curriculum lessons online. This setup gives our students the option to choose between remote or in-person studies, depending on their individual situations.

Our online school remains efficient, with ongoing partnerships with esteemed international schools and technology corporations like Oxford Education Online, King’s InterHigh, White Rose Math, Century AI, Firefly and many more. Thus, our children gain access to top-notch learning platforms and a diverse range of subjects that uphold BISU’s commitment to highquality education. Beyond that, we keep our students connected with the wider world. They actively participate in impactful charity and social initiatives, collaborating with organisations like Global School Alliance, Future Foundations, Global Social Leaders, COBIS, Brundibár Arts Festival, and many others. These projects foster cross-cultural communication and unity, instilling in our students a sense of global citizenship and reducing feelings of isolation.

I hope to provide some strength to those around me and instil belief that Ukraine will eventually overcome this nightmare and emerge even stronger.Year 2 teacher Alex with students

A key challenge we face is fulfilling the demand for more on-site British curriculum academic staff. Due to the prolonged period of online teaching during and since the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for ‘physical’ teachers in schools has become crucial to uphold the quality of learning. Currently, we have a few international educators who are physically present in Ukraine, teaching our students in classrooms. One of them is our Year 2 teacher, who has been with BISU since September 2020. He says, ‘By staying, I hope to provide some strength to those around me and instil belief that Ukraine will eventually overcome this nightmare and emerge even stronger.’ So, we wholeheartedly welcome those brave international academic staff who are ready to join us in Ukraine in these turbulent times. It will also be beneficial if retired international educators agree to remotely share their invaluable experiences with our students and teachers.

As we gear up for the next academic year, we recognise the need for additional global support to fulfil our mission. First, we need to strengthen our team and fill some important roles: SENCO, EAL Coordinator, and Head of AI. We also

aim to help Ukrainian educators obtain international curriculum certification. Our main focus is to seek partnerships with sister schools to create a new progressive educational model for Ukraine.

BISU recently marked its 26th anniversary, maintaining an unbroken presence in Ukraine throughout the years, even during the invasion. Our commitment goes beyond education; we strive to provide children with a sense of stability and

normalcy amidst chaos and uncertainty. Our students represent the future leaders who will rebuild and uplift the country. Equipping them with resilience, faith, and a lifelong dedication to learning is essential for Ukraine’s success and the triumph of human values all over the world. ◆

✉ a.azarova@britishschool.ua

t the end of June 2023 an obituary appeared in The Times in England for the materials scientist John Goodenough. He had reached 100 years of age and was not particularly a household name. However, together with Stanley Whittingham and Akira Yoshino, he had won the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for work of key significance for current telecommunications progress and, perhaps more importantly, our future development in the current global warming crisis. Together they were credited with discovering the usefulness of lithium cobalt oxide as an electrode material to power the revolution in portable electronics through the lithium-ion mobile phone batteries of the early 1990’s.

Lithium becomes crucially even more important as we seek to phase out fossil fuels and eliminate carbon emissions. We will need to build many more wind turbine and solar panel ‘farms’, but none of this will entirely do the trick unless we have efficient ways of storing that electrical energy. Storage will help counteract the inherent intermittency of renewable energy sources such as the sun and the wind. It is also needed so that we can power road and other transport vehicles. While not providing all of the answers, batteries are a large part of the missing link that will help us establish the new energy economy.

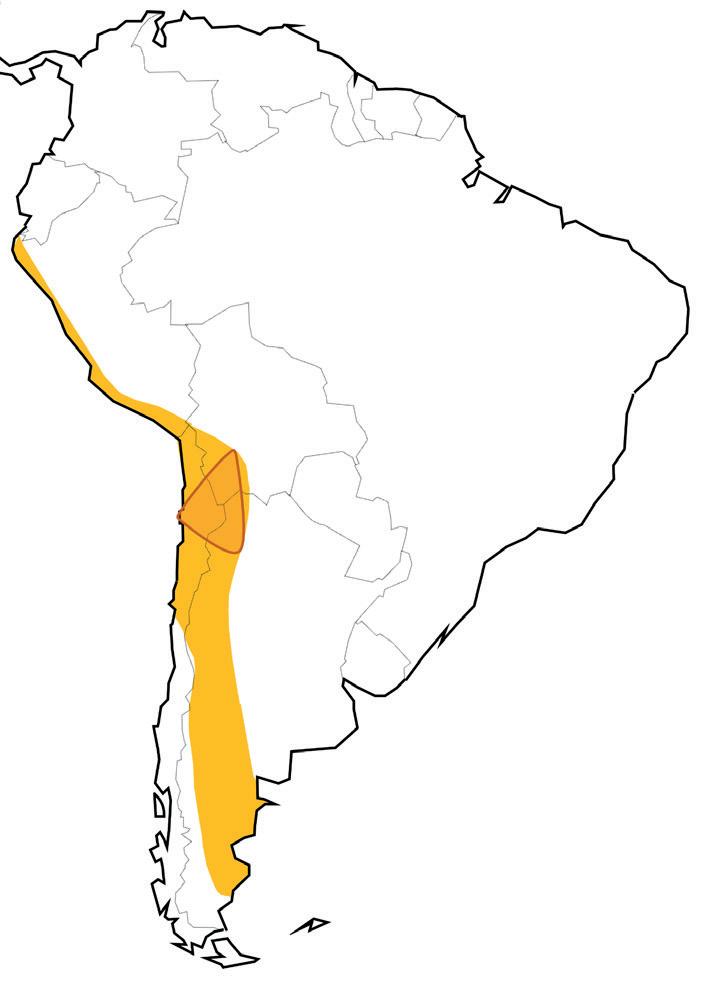

We need huge quantities of minerals, including lithium, cobalt and nickel, to make the batteries and other equipment required for the transition to net zero. The demand for lithium is particularly significant and is putting pressure on identifying new mineral resources and means of extraction. Until recently the biggest sources of exploitable lithium salts have been found in the brine beneath the huge salt flats of Bolivia, Chile and Argentina: the ‘lithium triangle’ of South America.

These massive salt flats, such as the Salar de Atacama and the Salar de Uyuni, are the remnants of prehistoric lakes surrounded by mountains without drainage outlets. Beneath the dried salt beds are enormous salt lakes containing dissolved metal salts including lithium chloride. Lithium chloride is separated from the concentrated brine by pumping it through a series of evaporation ponds in which the different metal salts precipitate out over time: a process of fractional precipitation. After well over a year in these different ponds the final solution is about 25% lithium chloride.

Above: Map of the lithium triangle within the arid diagonal of South America https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9a/Triangulo_del_lito.png

Right: Mounds of salt on the surface of the Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia. https://upload. wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/dd/Piles_of_Salt_Salar_de_Uyuni_Bolivia_Luca_ Galuzzi_2006_a.jpg

This solution is then transported to a lithium refinery where it is converted into lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide for shipping to battery producers around the world.

The pressure is on to develop other mineral sources of lithium, and the metal can be extracted from solid ores such as spodumene (lithium aluminium silicate). Australia is a major source of this ore and nearly all of it is then shipped to China to be processed. It’s important to realise that there is an environmental cost to processing the solid ore in terms of energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, emphasising the balances we need to consider in moving to new energy sources.

Countries worldwide are looking to exploit lithium mineral deposits. Portugal is developing what will become one of Europe’s biggest lithium mines, aiming to produce enough to power some 500,000 electric cars per year. Other projects are being considered in Italy, Germany and the United Kingdom. Lithium, until recently a relatively insignificant part of the mineral exploitation industry, is now at the centre of a ‘white gold’ rush linked to the need to establish gigafactories producing the new power batteries for our transport needs. The move from dependence on fossil fuels will create a new breed of electrostates – such as Chile, Argentina, Australia and China – that will dominate the extraction and refining of the metals needed for battery production, while other economic regions will push forward pursuing the development of battery technology and production. ◆

By Jessica Russo Scherr

By Jessica Russo Scherr

In late November 2022, the launch of Chat-GPT sent shockwaves through educational institutions across the globe, marking the advent of a new era in artificial intelligence that would reshape the landscape of education. For me, this transformative journey began in my Theory of Knowledge (TOK) class at Frankfurt International School, an International Baccalaureate (IB) Diploma course renowned for building critical thinking skills. It served as the perfect springboard to delve into the far-reaching implications of Artificial Intelligence (AI), not only within the walls of our school but also in our daily lives.

With TOK prompts that seem tailored to this topic, we looked into the features that influence the reliability of knowledge, the accuracy of evidence, and the role of material tools in knowledge production and acquisition as they relate to generative AI. Our initial discussions paved the way for a symposium on the Promise and Pitfalls of Artificial Intelligence in Education, held in early March 2023. The aim of the symposium was to ignite conversations regarding generative AI, specifically the unveiling of Chat-GPT. Students spearheaded the panel, discussing AI’s impact on critical thinking, the likelihood of bias, and the importance of maintaining academic honesty. The symposium garnered global interest, with over 52 countries tuning in to the streamed event, underscoring the universal curiosity and interest surrounding this pressing topic.

Months later, two essential questions continue to come to the forefront of our conversations about AI in education: What do students need to know? And how can we effectively teach them to navigate a world profoundly influenced by AI when we are still grappling with its full potential and usage? To start answering these questions we should go beyond simply thinking of AI as a cheating tool. In addition, we need to have a better grasp of how and when students use AI for their school work. Then we will be able to develop strategies that enable students to critically evaluate AI-generated content, empowering them to make informed decisions and engage responsibly with AI.

Over the course of the last few months, I have been speaking informally with our IB Diploma students, purposefully seeking their feedback on AI usage, gaining a deeper understanding of their perspectives, and identifying the essential support they require. What follows are some notable trends that emerged from their responses.

Despite the presence of AI in their lives and classrooms, ranging from Google searches, maps, and photos to predictive text, students exhibit different levels of usage and comfort with these technologies. While many students eagerly embrace AI tools like Chat-GPT, others prefer using AI writing tools such as QuillBot, Grammarly, and Sudowrite, which have been available for a longer time. The more active users of AI tools like Chat-GPT are learning how and when to use them. From the start, they became aware of its limitations and inaccuracies, as well as the importance of complementing AI-generated responses with reliable sources. Additionally, they are curious about how their use of AI for assessments will be perceived by teachers and peers. For many students, Chat-GPT proves beneficial in initiating brainstorming sessions. It assists them in breaking down larger projects into smaller, more manageable tasks, thereby contributing to their self-management. Notably, they employ it to prioritize their approach to Internal Assessments and Extended Essays in order to identify key arguments or subtopics to explore. Also, students efficiently organize their thoughts and develop a structured approach to their writing. This enables them to delve deeper into specific aspects of their essay, and can ensure a more comprehensive and focused analysis of their research question or topic.

Moreover, students find Chat-GPT to be an invaluable tool for navigating through extensive amounts of research. By providing concise and relevant summaries, Chat-GPT allows students to quickly grasp the main ideas and key points of the articles they encounter. Most commonly, students leverage generative AI to enhance their understanding of challenging concepts and subject matter.

For example, it can rephrase complex research articles into more understandable terms, helping students to comprehend the material fully. Then students can focus their attention on more significant tasks, such as analyzing and synthesizing the information they have gathered. By streamlining the research process, Chat-GPT empowers students to allocate their time and energy more efficiently, ensuring that they engage with the most relevant and meaningful aspects of their studies.

Overwhelmingly, these responsible uses of AI in our students’ work not only promote critical thinking and academic integrity but also impart essential skills that students will need once they leave school. They learn how to discern knowledge, seek multiple perspectives, and understand the limitations of presented information. As I look closely at the student feedback, my goal is to find strategies that would facilitate and foster creative, critical, and ethical engagement with AI. In order to delve deeper into the subject and shed light on its practical implications, I will now explore four main topics that are influential in cultivating engagement with AI: Asking the Right Questions; Harnessing Creativity and Critical Thinking; Ethics, Bias, and Developing a Critical Lens; and Personalized Feedback.

The initial step in working with generative AI is to hone your prompts and tailor them to meet your specific needs. Encouraging students to refine their AI prompts not only cultivates their ability to evaluate effectively but also enhances their grasp of the topic they are exploring.

two essential questions continue to come to the forefront of our conversations about AI in education: What do students need to know?

And how can we effectively teach them to navigate a world profoundly influenced by AI when we are still grappling with its full potential and usage?

Students learning how to craft prompts that not only yield better quality AI-generated responses but also maintain their ideas and perspectives as the centerpiece of their work requires nuanced skills and the ability to ask discerning and well-curated questions. Below is an example of a method for prompting Chat-GPT that I use in my Theory of Knowledge classroom.

1. Communicate the role for Chat-GPT. For example, specify that you want it to act as an IB Theory of Knowledge teacher.

2. Clearly outline the specific requirements and guidelines for the task, but do not ask Chat-GPT to execute the task yet. For example, later on I will ask you if my text aligns with a particular section of a rubric. Tip: Use smaller chunks of text rather than an entire essay.

3. Then ask Chat-GPT, ‘What questions do you need to ask me to fulfill this task?’

4. Provide detailed answers to the questions asked by Chat-GPT. Seek clarification if any questions or prompts from Chat-GPT are unclear.

5. Request Chat-GPT to complete the task, ensuring it centers its response around your ideas and words. Tip: ask for the responses to be in bullet points whenever possible.

6. Encourage Chat-GPT to consider diverse perspectives on the topic.

7. Evaluate the responses for accuracy, relevance, and clarity.

8. Reflect on the response and critically evaluate its strengths, weaknesses, and potential biases.

9. Cite your use of Chat-GPT in your works consulted and find any other primary or secondary sources needed to support your work.

The completed task will use the student’s ideas and words as the center point for framing its response. This collaborative interaction empowers students to actively shape the direction of their AI-assisted exploration.

AI excels at routine processes and tackling timeconsuming tasks. However, it can also enhance creative

The completed task will use the student’s ideas and words as the center point for framing its response.

and critical thinking skills by catalyzing brainstorming, streamlining data analysis, and acting as a simulator for complex scenarios. With the support of AI-powered tools, students can tap into their creative potential by gaining access to diverse perspectives and sources of inspiration.

Brainstorming and Idea Generation: By using AI as a collaborative tool in the learning process, students can gain a deeper understanding of complex theories and topics. This allows them to explore, refine, and express their ideas and propose innovative solutions. AI’s ability to analyze extensive datasets can unveil hidden patterns and connections, sparking creativity and encouraging unexpected connections. Students’ initial ideas can be analyzed, leading to a cascade of related ideas and unique angles. This AI-powered brainstorming process expands thinking and fosters the development of creative skills.

Data Analysis and Insight Generation: AI-powered tools can assist students in analyzing large amounts of data and extracting valuable insights. By leveraging AI’s data analysis capabilities, students can identify patterns, trends, and correlations that might have been overlooked. This exposure to diverse information and perspectives can enrich their understanding, and enables them to draw well-founded arguments and informed conclusions. For example, in a Theory of Knowledge class, students can use AI-powered tools to explore

how culture, knowledge, and language shape our understanding of the world. By inputting diverse cultural texts into Chat-GPT, students can uncover patterns in language usage across cultures. This can help the students see how culture influences how we create and interpret knowledge. It leads to interesting discussions about how cultural perspectives and language affect how we perceive, learn, and communicate knowledge.

Simulating Complex Scenarios: AI can simulate complex scenarios, allowing students to explore and experiment with different variables and outcomes. This interactive simulation fosters critical thinking by encouraging students to analyze the cause-effect relationships and evaluate the consequences of different actions. By engaging with AI simulations, students develop their problem-solving abilities and gain a deeper understanding of complex concepts and systems. For example, TOK students can create a simulation where people from different cultures interact. By manipulating variables such as language, cultural context, and communication styles, students can observe how misunderstandings, biases, and cultural nuances affect the exchange of knowledge. This simulation prompts students to critically reflect on the complexities of intercultural communication, and the role of language in shaping knowledge.

By shifting our focus towards cultivating mindsets that understand and analyze problems creatively and critically, we nurture the unique strengths that differentiate us from AI. The combination of AI-powered tools and human creativity and critical thinking skills enables students to approach challenges and generate innovative solutions.

Critically engaging with AI involves thoughtfully analyzing its capabilities, limitations, biases, and ethical implications. By educating students about these inherent biases and emphasizing the significance of seeking diverse perspectives, we empower them to question and critically evaluate AI-generated content for bias, inaccuracies, and fictional ‘hallucination responses’. Furthermore, students can use AI to engage in critical discussions and debates, enhancing their critical thinking and reasoning abilities.

AI tools learn from existing data, which can contain biases. By raising awareness of the biases that can exist within AI systems, we equip students with the necessary skills to identify, analyze, and evaluate the potential limitations and distortions in the information presented. One approach is to seek diverse perspectives on a topic. AI-powered tools can present different viewpoints and arguments, allowing students to practice analyzing and evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of each position. By fostering an environment that values multiple perspectives, students develop their critical thinking skills and enhance their ability to make informed judgments.

Along the same approach, students can deliberately incorporate ethical dilemmas into their AI inquiries. This involves exploring ethical issues related to artificial intelligence within their prompt, examining scenarios that

raise concerns about equity, social responsibility, privacy, biases, and the impact of AI on individuals and society. By integrating ethical dilemmas, students engage in critical thinking to grasp the complex ethical implications of AI and consider its broader dimensions. This approach encourages reflection on the ethical challenges that AI presents, fostering informed perspectives and thoughtful solutions.

Generative AI tools can target specific areas of improvement, such as grammar, structure, clarity, or argumentation, based on the student’s needs. It can create examples of well-written passages to help the student understand how to apply the feedback to their writing, as well as allowing the student to understand the rationale behind the feedback. Along with pointing out areas for improvement, it could also acknowledge the strengths and accomplishments of the student’s work to build confidence and motivation, fostering a positive learning experience.

Generative AI can modify an assignment to the individual student’s academic level and language ability to offer tailored feedback that aligns with their unique needs. It is also important to highlight that generative AI creates a space where the student can safely ask questions that they may not feel comfortable asking in

a classroom setting. This safe space can aid students in exploring new ideas, seeking clarification, and deepening their understanding without fear of judgment or embarrassment. AI adapts to the student’s learning journey step by step with an immediacy that a teacher cannot always provide. This type of feedback does not replace teacher feedback but can work alongside it. The teacher’s understanding of the student within the context of the class allows for a deeper level of insight and the ability to offer more nuanced feedback.

We are confident that the vast majority of students are fully committed to learning and adhering to the principles of academic honesty, which we have instilled in them well before the emergence of Chat-GPT. To facilitate students in using AI tools effectively in their work, we must have clear guidelines for source evaluation, citation, and academic honesty. Our guidelines need to be adaptable and scalable as the technology evolves and new applications are created. As we move forward, we should continue to gather student feedback to assess the effectiveness of AI in our classrooms and understand their experiences and challenges, recognizing that these may change as the technology evolves. Above all we want to ensure the student voice is central in their work. Through critical scrutiny, cross-referencing sources, and adherence to academic protocols, students will develop the necessary discernment to ethically and effectively harness AI’s potential.

In summary, cultivating AI literacy and fostering creative and critical thinking skills among students requires a multifaceted approach that includes clear guidelines, practical strategies, thoughtful prompts, critical evaluation, and considering ethical considerations. Applying these strategies will empower students to embrace AI while upholding our educational values. The journey toward AI literacy and ethical engagement has already begun, and it is up to us to guide students on this path of discovery, exploration, and responsible use of AI. Together, we navigate the promise and pitfalls of AI in education, creating a future where AI serves as a powerful tool for learning and growth. ◆

• Frankfurt International School: A curated collaboration of resources related to AI in Education. Accessible via: https://sites.google.com/fis. edu/ai-and-education

• AI @ FIS. Accessible via: https://sites.google.com/fis.edu/ai-andeducation/a-curated-collaboration?authuser=0

• Grammatical and Organizational Feedback Prompts. Chat GPT. Accessible via: https://chat.openai.com/

Jessica Russo Scherr is IB Diploma Theory of Knowledge Coordinator and Upper School Visual Arts teacher at Frankfurt International School, Germany. ✉ jessica_russoscherr@fis.edu

STANDARD LISTING

45,000+ independent & international professionals

15,000 social media reach accross six channels

Included in weekly jobs newsletter

FEATURED

Standard listing PLUS

Featured listing at the top of the Careers Section

Advertising alongside relevant content throughout the site

School Management Plus is the leading print, digital and social content platform, for leaders, educators and professionals within the independent and international education sector worldwide.

Our readership spans every stakeholder within fee paying education worldwide from Heads, Governors, Bursars, Admissions, Marketing, Development, Fundraising and Educators – to catering, facilities and sports. Our jobs & careers center is the natural meeting point for those already in the sector, aspiring to join it, or hiring from within it.

office@schoolmanagementplus.com

PREMIUM

Featured listing PLUS Free listing if the vacancy is not filled

Included on magazine digital distribution to 150,000 readers

Included in school directory

Listing experience hosted on Kampus24

UNLIMITED

Premium listing PLUS Unlimited job listings throughout the year to our audience

Newsletter presence every month for your school

Exposure and features on your school in main careers section

Print adverts for your listings each term

Listing experience hosted on Kampus24

The rst 100 schools to sign up will receive 20% o a year’s unlimited package

• Social following of 15k across 6 channels

• 60% annual growth in web tra c

• Core readership of Heads, Senior Leaders, Heads of Department, Bursars and Finance managers, Marketing and Admissions, and Development across the sector

By Rob Ford

By Rob Ford

In the summer, we did what many families do with time on their hands; we decided to tackle what was stored at the back of the garage. As we moved things into the cold light of day for the first time in a long time, a big wooden sign appeared that said ‘South Glos’ & Ridings International Learning Centre’. The near Proustian moment took me back to a time in my career in the early millennium when a real community of professionals and ideas came together across sectors in the English local authority of South Gloucestershire, bringing all kinds of teachers together in the centre I helped to establish as a then local authority lead practitioner for international learning.

The energy and achievement from this time has always stayed with me in my career and is one of the reasons I moved from England to Wales at the time

of the Coalition government in the UK: when professional learning communities and communities of ideas in schools and between schools were being squeezed out with a new political agenda that seemed to be less about collaboration, teacher autonomy, trust and the development of professional capital.

As academic deputy head at Crickhowell High School in Powys, one of my roles was to develop the Welsh Government’s policy for schools using the work of Professor Alma Harris and Dr Michelle Jones (2010) on developing

professional learning communities, for teachers and teaching assistants, and this was coordinated within the clusters of schools across Powys and the wider South West Wales region. This was a very innovative approach that helped develop individual skills, share ideas and give voice to teachers in the classroom, in lots of different classrooms and across the curriculum.

My headship took me back to England and a school community right on the border of Wales at Chepstow, at Wyedean School. I was fortunate to inherit a very strong, motivated and skilled teaching cohort who were already well versed in weekly shared teaching and learning briefings that came from

I was fortunate to inherit a very strong, motivated and skilled teaching cohort who were already well versed in weekly shared teaching and learning briefings that came from below and not from the top

‘There is no power for change greater than a community discovering what it cares about.’ Margaret J Wheatley

below and not from the top. They were also practising an approach to lesson observations in ‘Lesson Study’ (Smith, 2016) that really did see the development of ideas in the community of staff, students and parents, and Wyedean was a school where teaching and learning remained at the heart of the school’s mission and vision.

It also helped move the school on from a difficult legacy from the previous leadership team and, coupled with an outward-facing approach, had a powerful impact on systems and school improvement. It gave back trust and autonomy to teachers, which in turn saw greater buy-in from everyone and an arena where ideas and innovation flowed in the community: what all great school communities anywhere in the world should be about.

In his book ‘The Principal’, education writer Michael Fullan made the simple but also powerful case to all school leaders not only for the development of professional capital but also how to go about it: ‘In our work in whole-system change, my colleagues and I have shown time and again that if you give people skills (invest in capacity building), most of them will become more accountable.’ (Fullan, 2023).

Before my move to Moldova in 2019 I had already worked with schools, teachers and communities in Eastern Europe and the former USSR sphere of influence. Part of the legacy here is that very highly trained, intelligent, committed educators are still working largely in systems based on the near omnipotence and arbitrary rule of the principal, who is in turn stuck in a self-serving bureaucracy that didn’t work for children 30 years ago, let alone now for the 2020s.

Heritage International School was founded as something to be completely different from any school in this legacy system, with a mission to educate and prepare young people for the challenges of the future. That school leaders are there to enable, and the culture of servant leadership, is key here. Part of this innovation is the belief in skills and competencies, and trusting the autonomy, of teachers within a community of ideas and professionals to develop the high performing, high achieving school in a successful and sustainable model.

This was realised less than a year into my tenure, when the completely new model of online and hybrid learning

that was being operated in the Heritage schools reached the ears of the then minister, whose team descended rapidly on the school and a community of ideas supported the national education community, prompted by the extraordinary challenge of Covid in Moldova. (Ford, 2020)

This wider national community has continued to collaborate, share ideas and find answers together as Moldova faced the further challenges of the Russian invasion of neighbour Ukraine, energy outages and rising costs in a country that doesn’t have the wealth or development of countries such as the UK. The model I was a part of as a leader in my previous schools, I have brought with me to continue to develop teachers and teaching assistants professionally, and the skills and ideas have benefited all at a national and international level.

Starting in 2022, Heritage introduced nationally the ‘TeachMeet’ arena from the UK as a forum for professionals to bring ideas to share and collaborate. This has been extremely successful, especially as we face the relatively new challenge of AI/ChatGPT in learning. We have also worked across sectors, especially with colleagues in higher education (Ford, 2023). Through our networks including

References

COBIS, Global Schools Alliance, Climate Action Schools (Pope, 2022) and the Varkey Foundation/Global School Leaders, academic leaders and teachers have led online webinars and spoken at conferences on a range of topics that we have been prioritising at Heritage, from sustainability to leadership development to academic learning opportunities.