9 minute read

Humans & Influenza

HUMANS & INFLUENZA: ARE WE MAKING OURSELVES MORE VULNERABLE TO A GLOBAL PANDEMIC?

Charlotte Furness (OHS)

In January of this year, the World Health Organisation (WHO) released its list of the ‘Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019’. On this list was ‘Global influenza pandemic’, however what made this threat different was that the others on the list are known ongoing problems, yet influenza was the only one with uncertainty, as even WHO admits they can’t be sure of “when it will hit and how severe it will be.” On this list were a range of threats, from Dengue to air pollution and climate change . Subsequent monitoring systems are in place to detect any potential pandemic-causing strain of influenza, however could it be possible that human causes are speeding up the process of heading towards a global outbreak? Influenza is a virus, with several different strains. Most commonly known is seasonal influenza, which tends to occur in the coldest seasons in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. It is prevalent year-round along the equator . There are 3 strains of seasonal influenza: A, B, and C, yet influenza A and B pose a much greater threat of a large outbreak. Humans can also be infected by influenza that affects animals, known as ‘zoonotic influenza’ and while these currently don’t have the capacity to cause large scale outbreaks, if a mutation of the virus allowed it to spread effectively between humans, then the repercussions would be serious . An influenza pandemic is when a new variation of the virus previously not seen among humans emerges. If many people aren’t immune to this new variation then the virus will transmit rapidly, potentially causing a rapid, large-scale outbreak of influenza . An influenza pandemic could be deadly because the pandemic causing virus will be one that can easily infect people and that few people have immunity towards, causing the virus to spread rapidly. Flu pandemics on a global scale have been seen multiple times, but most notably in 1918. It’s estimated that around one third of the global population was infected with the virus, and up to 50 million people died as a result, which is more than double the death toll of the First World War, which was around 17 million. Each year, over half a million people are killed by seasonal influenza and 1 billion are affected by the virus . Recently, an increasing number of influenza positive viruses have been found over the past 20 years, as seen in Figure 1, meaning the likelihood of an outbreak is increasing as there are more variations of the virus which can mutate.

Figure 1 A growing population means that more people are vulnerable to influenza, as well as more people which the virus can infect, making it harder to contain outbreaks. The most vulnerable are the very old, the very young, and pregnant women . As Figure 2 and Figure 3 show, the population of the US has increased and the age structure has changed, with a large increase in the number of dependents, who are the most susceptible to influenza. A larger number of vulnerable people means more people to treat and more people to vaccinate. In lower income countries, the rate of population growth tends to be higher, leaving them more susceptible to outbreaks as their healthcare systems often lack resources needed to treat outbreaks of the virus.

Figure 2

Figure 3

A recent study has linked climate change and warmer winters to worse flu seasons. It indicates that milder winters are followed by heavier and earlier influenza seasons, as fewer people are infected with the virus during the warm winter, so more people are susceptible to it entering the next season . As climate change increases global temperatures, warmer winters will become more common, meaning the effects of future

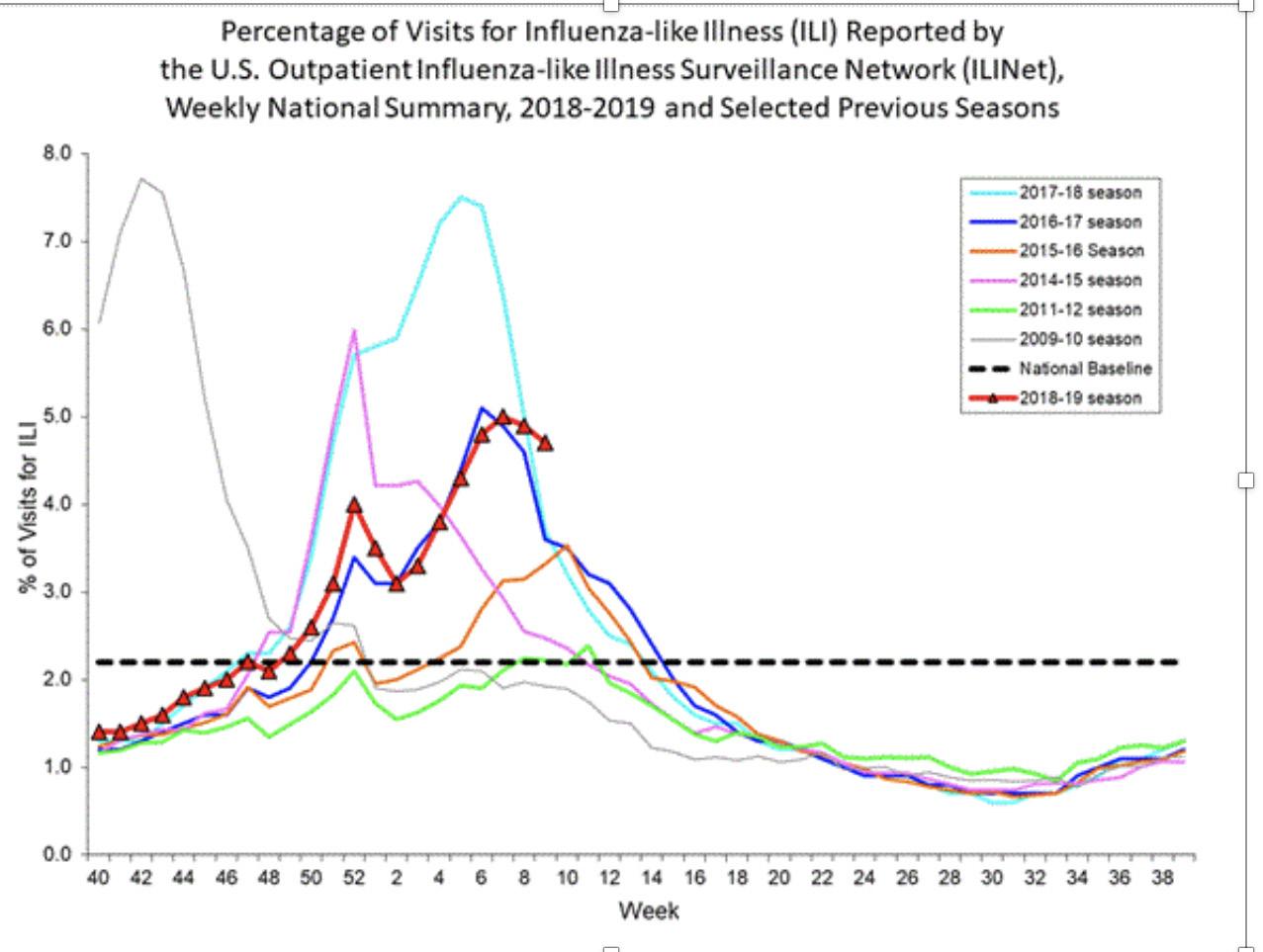

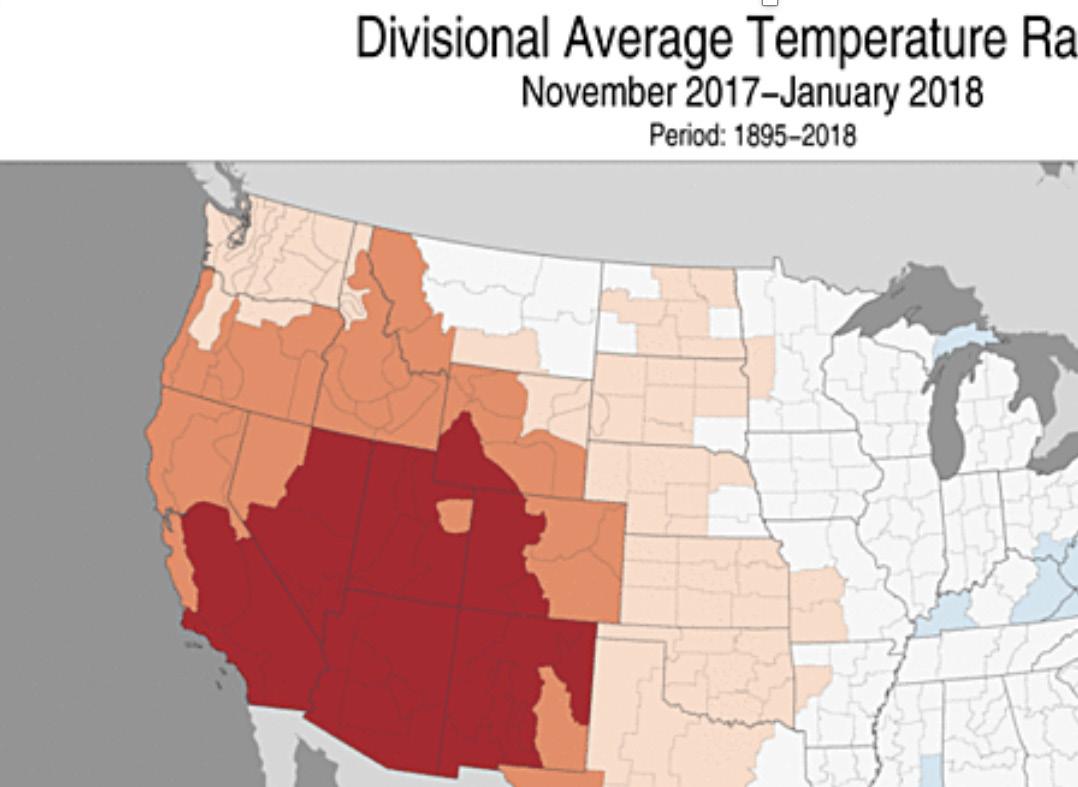

influenza seasons could be more and more serious . Figure 4 shows the percentage of influenza-like illness (ILI) visits to medical centres in the US, which is a way of recording influenza cases, and Figure 5 demonstrates the large number of record warmest temperatures from November 2017 to January 2018, coinciding with the large spike in visits for ILI over the same time period. However, this theory has not been explored in enough depth for the findings to be absolutely conclusive.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Another, more recent reason for the growing influenza pandemic concern are people who don’t get vaccinations and those who are against vaccinations. Vaccine hesitancy is another of the threats to global health that WHO announced this year . The US’s Centre for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that in the 2016-17 season, overall influenza vaccination for the US was 47%, below the national target of 70% . A vaccinated adult may still get the flu, as the vaccine only protects against the potential outbreak-causing strains, however it’s been proven to reduce deaths and hospital care duration for those who have been vaccinated. Vaccines helps prevent the circulation of the virus by stopping it from being spread to others as fewer people are exposed to the virus, creating what is known as ‘herd immunity’ . While complete vaccine refusal in the US is estimated at 2%,

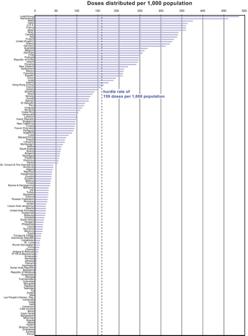

and a similar rate in Europe, these numbers haven’t increased exponentially over time , meaning their impact is minimal. However, a Canadian study reported that people who partially vaccinate are actually a larger issue than the relatively few total vaccine refusers . In Canada in 2014, there was an increase in 30% of vaccine-preventable disease cases from 2005 . Although many issues such as inaccessibility may also cause fewer people to get vaccinated, the fact still remains that not all those who are able to be vaccinated do, leading to a more susceptible population to outbreaks of disease and viruses like influenza. Even so, the impacts of vaccine hesitancy could be argued to be negligible, as Figure 5 shows that global vaccine dose distribution has increased by 27% since 2006 over 157 countries, from 350 million doses in 2006 to 450 million in 2009 . Nevertheless, only 20% of WHO Member States studied in one report reached the ‘hurdle’ rate of 159 doses per 1000 of the population, as seen in Figure 6. Over two thirds didn’t distribute enough doses to cover 10% of the population and over a third didn’t distribute sufficient to cover 1% of their population, despite the global increase in vaccine dose distribution . In the UK, young children over 65s, pregnant women and people who work in situations that mean they could catch the virus, such as health workers, are given free vaccination . However, the relatively small vaccine cover means that a lot of the global population is still vulnerable to influenza outbreaks and herd immunity is not yet achieved.

Figure 5

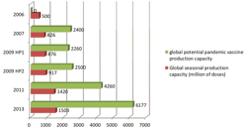

While the human-related problems of a growing population, milder winters and vaccine hesitancy could increase the effects of a global influenza outbreak, the fact still remains that the pandemic will be caused as a result of a mutation of the virus into one that our immune systems aren’t effective against. People may get influenza several times through their lifetime due to its constant evolution, meaning seasonal vaccines are reviewed biannually to increase their effectiveness .The constant mutation into new variations, means continuous surveillance is needed to monitor the spread of the virus. In 1952, the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GIRS) was created by WHO to monitor outbreaks in countries, watch for potential pandemic-inducing strains and to help advise the composition of vaccinations to ensure they are the most effective. With 114 countries participating, it is the largest influenza monitoring scheme to date. WHO has also set up the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Framework, to help the 194 member countries of WHO should a pandemic ever occur . Furthermore, vaccine production capacity has increased, with Figure 7 representing the estimates of global seasonal and potential pandemic influenza vaccine production capacity in million doses per year.

Figure 7 While humans cannot stop the Influenza virus from mutating, it appears that through climate change, vaccine hesitancy and increasing vulnerable population size we are making ourselves more vulnerable to a global influenza pandemic by decreasing the effectiveness of the preventative methods that are in place. That being said, our capacity to monitor outbreaks as well as produce and distribute vaccines has increased, despite the arguable effect that vaccine hesitancy is having on coverage. Therefore, it remains to be seen just how prepared, or unprepared we truly are for an influenza pandemic until the day comes when we have to put it to the test.

World Health Organisation. (2019). Ten threats to global health in 2019. https://www.who.int/ emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

World Health Organisation. Influenza: are we ready? https://www.who.int/influenza/spotlight

World Health Organisation. (2014) Influenza virus infections in humans. https://www.who.int/influenza/ human_animal_interface/virology_laboratories_and_ vaccines/influenza_virus_infections_humans_feb14. pdf ?ua=1 World Health Organisation. Influenza Laboratory Surveillance Information by the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System. http://apps.who. int/flumart/Default?ReportNo=10

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report. https:// www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/index.htm#ILIMap

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Temperature and Precipitation Maps. https:// www.ncdc.noaa.gov/temp-and-precip/us-maps/3/201 801?products%5b%5d=nationaltavgrank&products%5 b%5d=nationalpcpnrank&products%5b%5d=regiona ltavgrank&products%5b%5d=regionalpcpnrank&prod ucts%5b%5d=statewidetavgrank&products%5b%5d= statewidepcpnrank&products%5b%5d=divisionaltavgr ank&products%5b%5d=divisionalpcpnrank#us-mapsselect Towers, S., Chowell, G., Hameed, R., Jastrebski, M., Khan, M., Meeks, J., Mubayi, A., Harris, G. (2013). Climate change and influenza: the likelihood of early and severe influenza seasons following warmer than average winters. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/ articles/PMC3770759/

Arizona State University College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. (2013). More severe flu seasons predicted due to climate change. ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily. com/releases/2013/01/130128142847.htm

Bergman, R. (2017). CDC: Fewer than half of Americans get flu vaccine. The Nation’s Health. http://thenationshealth.aphapublications.org/ content/47/9/E45

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Key Facts About Seasonal Flu Vaccine. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/ protect/keyfacts.htm

U.S. Census & Minnesota Population Center. U.S. Census Population Pyramid, 1850-2000. http://vis. stanford.edu/jheer/d3/pyramid/shift.html

Tumpey, T.M., Basler, C.F., Aguilar, P.V., Zeng, H., Solórzano, A. (2005). Characterisation of the Reconstructed 1918 Spanish Influenza Pandemic Virus. Science. http://science.sciencemag.org/ content/310/5745/77.abstract

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pandemic Basics. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/ basics/index.html

Vanderslott, S. (2018). Anti-vaxxer effect on vaccination rates is exaggerated. The Conversation. https:// theconversation.com/anti-vaxxer-effect-on-vaccinationrates-is-exaggerated-92630 Busby, C., Jacobs, A., Muthukumaran, R. (2017). In Need of a Booster: How to Improve Childhood Vaccination Coverage in Canada. C.D. Howe Institute. https://www.cdhowe.org/public-policy-research/needbooster-how-improve-childhood-vaccination-coveragecanada

Dubé, D.E. (2017). Who’s really to blame for Canada’s falling vaccination rates? It’s not just anti-vaxxers, report says. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/ news/3409038/whos-really-to-blame-for-canadasfalling-vaccination-rates-its-not-only-anti-vaxxersreport-says/ World Health Organisation. (2014). Global Action Plan for Influenza Vaccines: Global Progress report: January 2006- September 2013.

https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112307/9789241507011_eng.pdf;jsessionid=7C5014B40E7A6F27182D00758B27E6F5?sequence=1

Palache, A. (2011). Seasonal influenza vaccine provision in 157 countries (2004-2009) and the potential influence of national public health policies. ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S0264410X11016379?via%3Dihub

NHS. Who should have the flu vaccine? https://www. nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/who-should-have-fluvaccine/