4 minute read

ROOTS

Cara Hene (WHS)

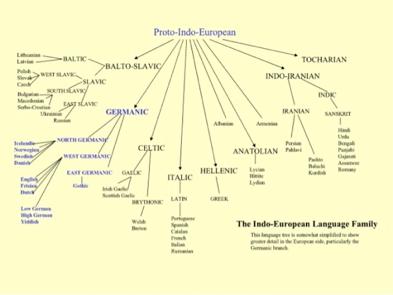

As of 2020, there are over 230,000 words defined in the Oxford Dictionary, each with their own unique journey; crossing borders, changing meanings countless times, growing, shrinking, as they make their way into the common vernacular used today, until their next inevitable transformation. The word “tree”, as we know it, is no different. The dictionary definition of ‘tree’ is: “a woody perennial plant, typically having a single stem or trunk growing to a considerable height and bearing lateral branches at some distance from the ground.” 15 It also has other specific definitions in botany, linguistics, computing and mathematics. But where did this seemingly inconspicuous, monosyllabic word come from? Unlike other common words, it’s difficult to pinpoint its roots. “Tree” does not have any obvious roots in Greek or Latin (δέντρο, abror/bratus) and unlike other botanical words, it’s not intertwined with European languages: like ‘foliage’ its roots in Old French ‘feuille’ meaning leaf and similarly hedge, originating from the German ‘hecke’16. We therefore must delve much further to discover its true origins. The roots of the word “tree” are so ancient that they buried in a language that was spoken during the Bronze age, 6,000 years ago17, called Proto-Indo-European. This, in fact, not really a language at all, there are no written texts18, therefore linguists theorised what this language would have sounded like. These linguists draw on the assumption it was the ancestor to more modern Indo-European language groups such as Italic, Celtic and Germanic. Therefore, Proto-Indo-European is an almost hypothetical language, with each word being a well-informed guess as to how our ancestors may have conversed. Here is a diagram to show how influential Proto-Indo-European is on the development of languages worldwide: 19 These ancient Proto-Indo-Europeans roamed the land in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe, (present day Ukraine and southern Russia) 20 in a quest to find shelter and food, both fortunately abundant in the trees surrounding them, which we believed they named ‘deru’21 . Interestingly, ‘deru’ had two meanings, it also meant true, as in upright or steady. The similarities between ‘tree’ and ‘true’ are many: not only are trees strong and steady, they are also reliable, year after year an orchard delivers a harvest of fruit, faithful and true. Then, ‘deru’ slowly but surely evolved into the ProtoGermanic ‘trewam’ - (spoken in 500 BC).22 ProtoGermanic is another theorised language; it was spoken by Northern Europeans and Southern Scandinavians during the Roman Republic.23 A map to show the approximate locations of IndoEuropean languages in contemporary Eurasia: 23

Nearly 1000 years later, the word for ‘tree’ was little changed, and in 450 – 1150 AD25, Anglo-Saxons, who spoke in Old English, used not ‘trewam’, but trēow, to describe these tall majestic plants26. Importantly, it is during this period that the earliest example of ‘tree’, was recorded in a manuscript. Dated around 825 AD, Psalm 148 reads:

“Muntas and alle hyllas, treo westemberu and alle cederbeamas” (“Mountains and all hills, fruit trees and all cedars”)27 .

This is where it begins to become possible to prove, or at least try to prove the etymology of the word ‘tree’. Where earlier versions of ‘trēow’ were hypothesized, it’s only during this period that English-speakers started to preserve the language that they spoke.

The word for tree, and what was to become modernday English as a whole, slowly became more and more similar to the language we use today. Its next step took place at some point from the 12th to 16th century, when the island of Britain had been invaded by William Conquerer and the population began to speak what we now call Middle English, spellings differed during this period of time even more than they did in Old English28. There was no real uniform dictionary nor spelling conventions, yet more and more people were becoming literate, giving rise to “tre”, “treo”, “trew, “trow” all having the same meaning. Finally, after its long and arduous voyage, “tre”, “treo”, “trew and “trow” merged into the singular “tree” and its cousin, “true”. Despite there being a 6,000-year difference, having changed in meaning, been spoken by many different ethnic groups and in many different regions, it is still not that disimiliar to its humble root - “deru”. Bibliography

15 Oxford Dictionary 16 Online Etymology Dictionary 17 Telling Tales in Proto-Indo-European, Eric Powell A. 18 Archaeology et al: an Indo-European Study, School of History, Classics and Archaeology, University of Edinburgh, 2018 19 Slideshare.net

20 The Indo-European Homeland from linguistic and archaeological perspectives, annualreviews.org 21 Forest Words and where they came from - grammarphobia.com 22 From Proto-Indo European to Proto-Germanic OUP, 2006, page 296

11 Andrew, 2000 The Role of Migration in the History of the Eurasian Steppe: Sedentry Civilisation v. “Barbarian” and Nomad Palgrave Macmillan. Page 117 23 Britannica.com

24 Baugh Albert, 1951, A History of the English Language. Pages 60-83, 110-130 25 Online etymology dictionary 26 Forest Words and where they came from -grammarphobia.com 27 Burrow J. A,Thurville-Petre, Thorlac, 2005, A Book of Middle English, 3 ed, Blackwell page 23.