Windhover, NC State’s literary and arts magazine, strives to serve the creative community of NC State through its annual publication that includes art, film, music, poetry, and prose. Our main goals are to provide a welcoming environment for out-of-the-box thought processes and to encourage all artists to submit.

Mission Colophon

Printed by RR Donnelley in Durham, NC

One Litho Way, Durham NC 27703

Typefaces used are 70 point Duende Pro for display type, 30 point Yatra One for headers, 13 point Karla Regular for bylines, and 10 point Karla Regular, Bold, and Italic for body copy.

Book pages are printed on 80# Text Lynx Ultra Vellum, White. Cover printed on 100# Cover Lynx Ultra Vellum, White with embossing. Created with Adobe InDesign 2023 on personal staff MacBook Pros 1,200 copies distributed free of charge on NC State’s campus in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Editors

EDITOR IN CHIEF Ryley Fallon junior in English

DESIGN EDITOR Emma Carter senior in graphic design and English, creative writing

ASST. DESIGN EDITOR Sophia Chunn senior in graphic design

PROMOTIONS DESIGNER Cora Jones freshman in art + design

LITERARY EDITOR Tuesday Pil sophomore in English, creative writing

ASST. LITERARY EDITOR Protima Mukherjee senior in chemistry and science education

VISUAL EDITOR Ben Daggs sophomore in English and philosophy

AUDIO VIDEO EDITOR Javian Evans PhD of textile technology management

Literary Committee

Macon Monday freshman in English literature

Kayla Lare freshman in English

Marisa Hooper freshman in communication and English, creative writing

Nicole Shearon junior in English

Kaitlyn Parker freshman in English

Sruti Bontala freshman in biology, integrative physiology and neurobiology

Visual Committee

Hallie Walker junior in business administration, marketing

Camilla Keil senior in arts studies

Publication Adviser

Martha Collins

From the Editors

With the signature swirls of Windhover LVII, I hope that this new edition can remind you of our interconnectedness. In our earliest stages of planning, we wanted to find a way to celebrate and lament all things new and relevant with a timeless design. As our submissions started to roll in, the aftermath of the pandemic and the state of the campus mental health crisis became clear, and we were reminded of the value of participation in the arts. At Windhover, although we always wish we could have included more pieces, we hope to give our artists the space to just be. As you’re reading, feel free to sit with what our community has chosen to bring forward. We hope you can see all the life that exists beyond these pages.

I want to wholeheartedly thank all the lovely people who crafted this edition with so much patience and care. Thank you to all the volunteers who just started their journey with the outlet and whose work is essential to this publication. Thank you to Emma and Sophia who magically make readers gravitate toward the pages. Thank you to Tuesday and Protima for truly caring for every word submitted. Thank you to Ben for always helping to elevate the visual experience. Thank you to Javian for selecting submissions that can’t be contained on the page, audio and video. Thank you to Cora for understanding Windhover at its heart and dreaming up our promotional material. Thank you to Camilla for always being there. Thank you to our spectacular advisor Martha, who has empowered us as student leaders at every step. The thoughtfulness you all contributed is vital to our impact.

Above all else, I want to thank all those who trusted this publication with a tiny piece of themselves. We admire those who are willing to translate their experiences into art and share it with their community. Whether your work is featured or not, we hope you can see yourself as a piece of something bigger while reading and viewing. This year’s publication cycle has been both devastating and remarkable. We hope this edition is a retreat for its readers, a way to better see ourselves and each other.

Interconnectedness is the lifeforce underneath the design of this year’s Windhover. It is difficult to reflect upon what has been a particularly heavy year here at NC State, but as I was considering what kind of visual box this year’s creative work was going to fit into, I knew it needed to reflect the reliance we have upon each other. The bright spots are undeniably related to those we find ourselves able to lean on in difficult times. I wanted the design to reflect the warmth that can be found between friends even if there are no words being spoken, the trust that sits in a hand being held, and the comfort that can be found in the cookies your roommate made for you. I hope that this community is something that each of you reading this magazine can locate and cherish in your worlds.

Ryley Fallon, Editor in ChiefFor four years I have been so fortunate to have been at the helm of this publication’s design. Designing and creating a publication is an enormous undertaking, and any note I wrote would be incomplete without a brief list of acknowledgements. First, to my good friends who have been on this design team with me: Campbell Briggs and Sophia Chunn, I am indebted to your creative geniuses and flair that you brought to each of the books we crafted together. To my editors in chief: Xenna Smith, Camilla Keil, and Ryley Fallon, I am so thankful for your steady hands. To the numerous folks that have worked on staff and poured hours into making sure that each book’s contents were stellar: Windhover, and I, am better for your dedication and knowledge. Of course, to our adviser, Martha Collins: thank you for caring so fondly for not only our craft and the final product, but also for us as creatives and students. Finally, to my grandfather, Dick Carter, who sent a letter to NC State Student Media on my behalf the second I was admitted to the university in 2018. I have been so fortunate to be raised by people who believe in every step I take before I take it, and nearly none have done so with the vigor you have. I am fortunate beyond words to have been surrounded by so many incredible people, and I will always owe so much of my character to each one of you and those I have failed to mention in this brief space. There is so much joy to be found in the spaces we occupy together. Thank you, reader, for contributing to these spaces. Cheers!

Emma Carter, Design EditorEsperanza Kairas Williams poetry

mealtimes Krushi Badnam poetry

Untitled Maren Carter lithograph

Hayley Williams Madison Jennette watercolor

superstition Thomas Jackson poetry

Gorge Daniel Knorr photography

The Bottle Jordan Watts poetry

Identity @ 4:24 a.m. CJ Murphy collage

Homogeneous Alex McRorie charcoal

Teeth Alex McRorie charcoal

What Happened to Sammy Kairas Williams prose

Limelight Daniel Knorr photography

Compost I am today Alexis Jacobs poetry

Pitchers Haley Kinsler photography

Cheers Grace O'Daniel collage

/ANALOG/ Skeleton Thomas Jackson poetry

This Earth is Our Own Roshni Iyer prose

Bachelors Kenneth Scott photography

Cosmic Jazz Ben Price poetry

Twilight in Mirror Town Hal Meeks photography

Tug of War Joi Vercellono poetry

AUDIO SUBMISSIONS Various creators

Little boxes Alex McRorie charcoal

Jon at Raven Rock Haley Kinsler photography

Dryad Callihan Herbster prose

Me, the baseball Mairead Maley poetry

Chef's Cannibal Concoction Ben Price poetry

Gay is, Gay ain't Anthony Ramsey poetry

Kicking Up Stardust Ray photography

Fulfilment Marlas Yvonne Whitley poetry

Take A Picture Keymoni Sakil-Slack digital art

Even the faintest sounds Dedan Wilkins poetry

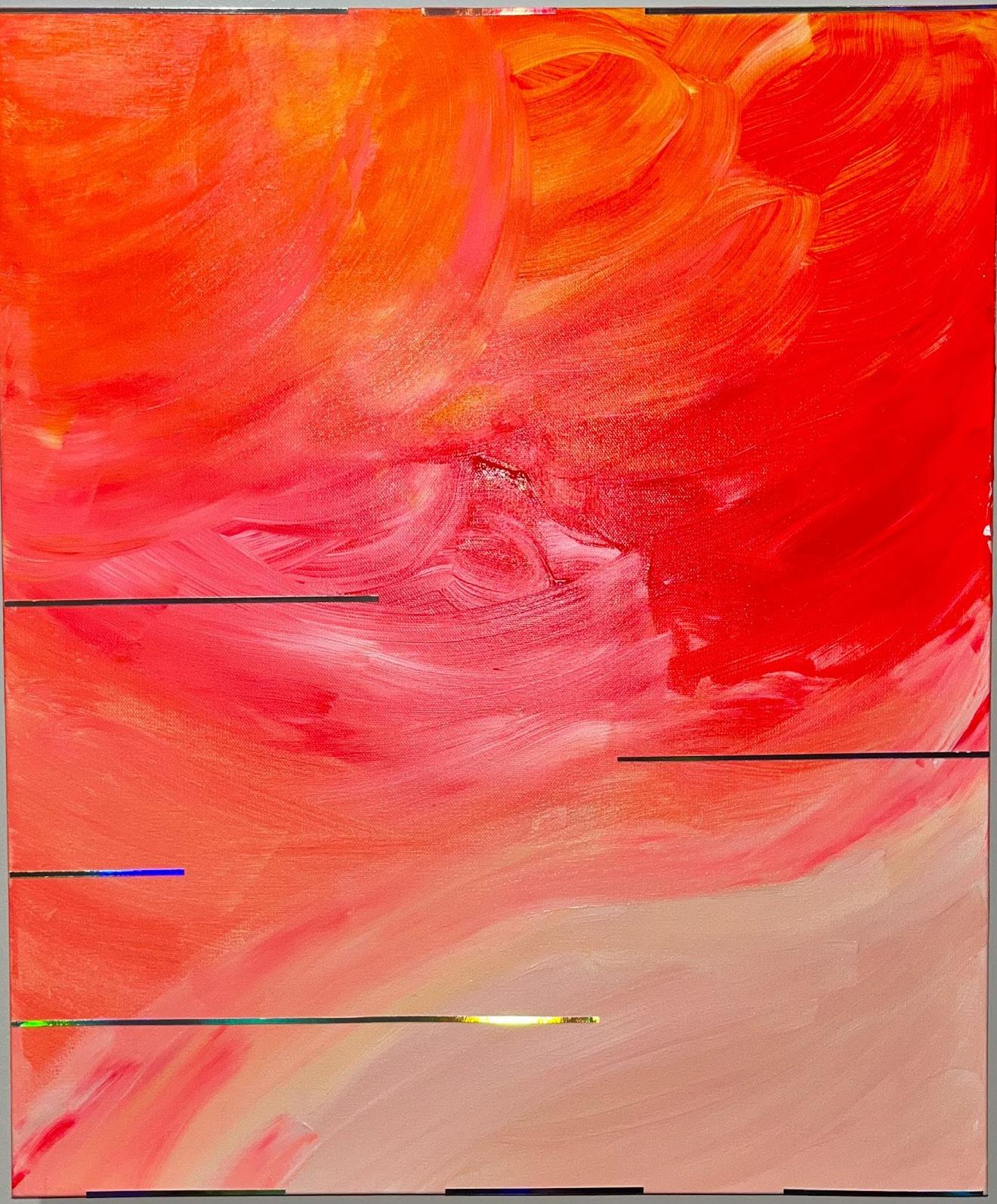

Abstract Sunset Keymoni Sakil-Slack digital art

White Lead and Mercury Thomas Long poetry

70 72 Master Procrastinator Brandon Herrera a day spent in a body that is mine Vy Hoang digital art

Dark Star Jules Millward poetry

Tether Unique Patton digital art A Chance Encounter Christopher Oates digital art

Aubade Nicole Shearon poetry

What is composition? Sarah Wagoner collage

Just Saying Hello Katie Winslow poetry

Rain, At Last Sruti Bontala poetry come find me in the storm Ami Patel acrylic Planes Charlie Blackerby ink pen

malibu Jordan Watts poetry

Rhode Island Sophie Frain photography

Black Bodies, White Eyes CJ Murphy collage

I Sit with the House Cat Nicole Shearon poetry

In My Room Grace O'Daniel acrylic

The Tray Bella Woods prose

I am

Like a red balloon, tied to an anchor

Wishing I could float, float, float, high away Tan alto que no puede alcanzarme.

I am waiting for a day that will not come

That window feeling, that graveyard feeling, that I don’t think I belong here feeling

That feeling that swallows you up so whole that you forget what it means to breathe

And you sit

And you wait and you wait and you wait

Your sighs threatening to put the radiator out of business

A deep heave so strong it makes the wind jealous.

Sometimes God is asleep, entiendes

But when he wakes up he paints watercolors and Monets

And names it after you

Except you get to sleep in rickety houses instead of galleries.

Morenita, que linda, you look like Christmas, And feel like it too

And if it looks good and feels good then it must be true

But I don’t think I want to be Christmas anymore.

No, I am Alphabet soup.

Eating it up so I can pass my classes and get out of here.

So I can leave Mango, leave windows, leave boys with too tough hands

Who think black and blue suits me more than my natural brown.

I am

Glass breaking

Dishes clattering

The string loose on the violin

The kind of sound that turns your brains into soup, Mixes with dust and blood,

Using your bones to stir the pot.

That’s what I am.

A pot of soup with too many vegetables that no one likes but maybe they would after they haven’t eaten in awhile.

A pot of soup that hopes that someone will be nice enough to take me to the sky to eat under the tortilla star, never to bring me back to the earth that isn’t mine.

Then everything would be fine. Then I could grow

As tall as the trees, so outstretched that there would be no use for my elbows anymore.

Es muy cansado

Teniendo all this esperanza

And no one to give it to or take it away. A hope

All my own.

my mother and i compare scars in the kitchen a bruise, a burn, a slivered half-moon branded into our palms.

we gossip, our voices like dry tinder as they catch fire ; our spittle is lighter fluid, bubbling oil, monsters that ebb and flow by our fingertips.

she oils my hair with kerosene and tells me about the street dogs and their melting eyes, wearing garlands on festivals.

she packs me a lunchbox as i sip on sweetened milk ; savories wrapped in tinfoil ; her forgotten vices slipping down my throat

she says i grind my teeth too hard, they’ve lost their edge. i wear my retainer anyways, feeling my nerves whittle away ; inherited porcelain ; yellow china ; crack, crack, cracking.

and on the day i finally come home, smelling like smoke, disheveled ; my braid unbound ; i will pick up a knife, — and tiptoeing across its sharp edge, i see the end — and learn how to cut

if your ears ever swell with heat the old wives telltale sign that someone’s talking about you or a chill runs down your spine because someone stepped on your grave or you feel my hands working knots out of your back turn to find it’s just the wind know i’m doing all of it for you the rubble i call my home feels like the last day i spent in yours i thought i loved the feeling of vulnerability thought i finally came around to it yet just like the last carousel spin i’m in the same place same mood cycle same coping where i go on a four day liquor bender because i read once that they used whiskey to warm people up in arctic conditions and i’m trying anything to solve the cold brick i try to get even a sputter out of i stepped on a crack in the pavement and it never broke my mother’s back now i’m sure they got it wrong that the little pavement canyon ran up my porcelain body and settled like a spiderweb in my heart

we passed around chapstick like a joint: pressing it against our lips barely parted, soft to the touch and warm. it made us giddy, flushed and giggly sitting in a circle and looking more at the bottle in the center than at each other. i wanted to open a window, gulp down cool air, to stick my head out into the night and not pull out till my body was cold again.

it always began in early May when the air is sticky and sweet heavy with all the promise of summer about to come.

all of us girls in a tiny dorm room, hot with blood and breath and bodies, and wanting. i watched her take her t-shirt off: the way her lace bra peeked out and then revealed itself, laying flat across her breasts, i watched her back arch when she pulled it over her head. she smiled at me, god i wanted

"What happened to Sammy?"

"Oh, you know how boys are sometimes. They can’t keep themselves outta trouble."

A beat. She gives a lopsided mischievous smile. There’s something she’s not telling me.

"Sammy, oh Sammy. You know he never liked his daddy much. Too big, too mean, too hard. Always tryna teach someone a lesson who never asked for none. There weren’t nothing about him that he didn’t hate.

"Well, there was one thing. You see, Sammy’s daddy had a shotgun. And he was only following orders, you know, only worryin’ about problems that he knew he could change. His momma taught him that. And so, it was lookin’ like this one problem could finally get around to being solved. Ain’t that something! The old bat finally gave him something to smile about. Anyways, as soon as Sammy found it he made out a plan. Now he ain’t ever used daddy’s shotgun before, but that didn’t bother him none. Slowly, quietly, he made his way upstairs, creeping around all sneaky-like. He stopped by little Isabella’s room, making sure her star lights were on and her teddy bear was in her arms, all nice and snug. He loved Isabella, and would never forgive himself if he ever caused her any harm. Wanted to make sure she could fall right on back asleep if she woke up. He kissed her on the forehead too—a goodbye, just in case. Then he walked to momma and daddy’s room, quiet as could be. You know, I knowed he was a brooder, always sulking around like he was the next James Dean or somethin’, like that dark head a hair of his would make him blend into the night better, that’s what he said. But I had never seen him so serious in all our days. He peered into momma and daddy’s room and even though it was dark I swear I saw a glint in his eye. Momma wasn’t there, of course. Working late at the hospital again. But daddy, that lazy, good-for-nothing lug, he was sleeping. I thought he looked kind of nice actually, all peaceful and relaxed. We stayed still for a little, just breathing and watching him. I glanced over at Sammy and I started to wonder if he was gonna quit. Couldn’t read his face—it was too dark—so I went back to watching daddy sleep. The longer I kept on lookin’ the more I saw Sammy. He looked like him, a little, in the eyes. I asked Sammy if he knew that. I guess that set him off because the next thing I knew daddy’s

shotgun is touching my head. Nearly went cross-eyed tryna look at it."

I didn’t realize we had leaned in as her story progressed until now. I could feel her breath on my face and her eyes locked on mine.

"Then, BANG!" She slams her hands on the table. I snap back. "Dark as night. Can’t see nothing."

My eyes go wide. I knew her and Sammy’s relationship was an odd one. After all, they met and fell in love at the very hospital his mother worked at. Unhealthy at best, miserable and treacherous at worst, but I always assumed that she was the one person that was off-limits from his typical anger and outbursts. Had I been fooled this whole time? Was I wrong? What else did I not know?

"He shot you?!" I exclaimed. She gives me that smile again and winks.

"Nah, I had just closed my eyes." Her expression changes, but not in a way that I understand. She never drops that grin, but I can tell that it isn’t laced with its usual glee and playfulness at this moment. The bard has stopped playing his song. I’m not sure if she’s telling the truth or if she just doesn’t want to go any further. I sit in silence, eager to discover which it is and waiting for her cue.

"Later on I asked him why he did it. I mean, I’ll stand by him through anythin’ as long as he’s gotta good reason. Motives are important, y’know. Wanna know what he said? Can’t be my father’s son if he’s not here. Can’t become my daddy if he didn’t become nothing. I told him that he became dead and we will too one day so what if we didn’t actually win?"

She takes a pause.

"Sammy said there’re always winners." She trails off, looking into the distance. She’s either trying to remember something or trying hard to forget. She begins laughing, throwing her head back. Did I miss a joke? Did I miss the five minute warning before the end of intermission? She starts back, in between gasps—

"See, I was crazy because I tried to kill myself and he was crazy cos he tried to kill someone else and it’s like our crazy clicked. And that’s what life is all about! Finding someone who cancels out your crazy. Finding someone who sees the skeletons in your closet and then shows you the monster under their bed and then you have a big ol’ party full of spooks, a real creature feature. Finding someone... who sees all your screws loose but ain't afraid to get on your shoddy carnival ride anyway."

Suddenly, without warning or hesitation, she springs out of her seat, hopping onto the table. She plucks my hat off my head.

"Step right up, step right up! Grab your tickets here! The circus is in town, baby!" She extends her hand, and I know from her face what’s coming next. I shyly prop one foot up on the chair, too embarrassed to fully rise and join her theatrics. "Aha, there you go! See, that’s the spirit! You done already started turning red."

A deep urge to create followed by a deeper urge to rot. To let my mind consume itself, now that would be a fruitful endeavor. To compost today’s efforts (along with yesterday’s and tomorrow’s) and try again another time.

Another time I’ll yield a crop I won’t destroy, plant a seed I won’t dig up. Root myself in a garden and tend to it with the utmost care. I’ll be damned to sit in darkness, but the light is far and the rot is inviting.

Compost I am today, fruit I’ll bear tomorrow.

i want to break/the door/

i want to drain/the hot springs/

i want to wash/the snow/out of your arteries monochrome pill paintings

fourth hookup how am i/the boyfriend/already

i want to drain the snow

i want to break the hot springs

i want to wash the boyfriend of his soot

i want to maim/the door/

i want to plug into your capillaries embroider snapdragons with loose hairs on my pillow

i want to wash/the werewolf/

fourth hookup how am i/the door/

i want to maim the werewolf prove i’m more than a pawn

i want to advance/the bishop/

i want to chip/the mug/

i want to break the bishop

i want to drain the mug

i want to turn/the clock/back

i want to open/the door/ dissipate your puffed rings

i want to break the clock

i want to close the door

Yeh dharti apni hai.

You never remember the exact smell of the smoke. Whenever you smell smoke at home, you think, this is it. This is what Delhi smells like And then you get off the plane and go through customs and step out into the night air right outside Indira Gandhi International Airport and you take a deep breath and then you remember: I was wrong. Nothing smells quite like this.

You always cry when you step out of the building. There’s something different about the earth there too. The dirt, the dust—it rises to meet you, demands to be recognized, welcomes you home. You returned. You came back. Hello, hello, hello.

You can almost taste the idli. It was what your grandmother would make back when she and Thatha still lived here. The plane would always land at night, and it was a good, easy meal. They would be warm, freshly heated, and the spice of the gunpowder tasted like an emotion you could never name. You don’t get gunpowder in restaurants, and the idlis are always the first food you’ve had that tastes like home. Your amma used to pack idli to eat at the airport, but they aren’t meant to be had cold.

You haven’t seen that house since 2014, and you never will again, but the layout of the rooms is burned to the back of your eyelids. If you could have it your way, it would stay there forever.

This time, you go straight to a different part of the city, and though there is no idli waiting for you, Athai has curd rice, and you have it with pickle. Your athai and athimber pick you up, and you cry a little seeing her too—but you try to play it off.

She doesn’t say anything. Maybe she blinks a few more times than she has to.

II.

You had been in the airport back home when you found out. The last two trips you had made hadn’t been to visit. You cry in the airport, and your amma blinks hard. Your little brother is quiet, but he leans into your mom, and she has a child on either side pressing into her. Please don’t let this visit be another goodbye, you think. Please don’t let it. You are so sick of them.

I might stay longer, Amma says. I’m not sure how long

The last time you were in India, the house was full of smoke and a fire blazed in the living room. Priests were chanting and you and your brother were under your paati’s bed and you were both crying. Thatha, your dad’s dad, had died a year ago, but you hadn’t been able to attend the funeral. This one-year ritual was the closest you got. Was it the smoke making you cry or was it the grief?

III.

Your bhaiya gives you a hug when you walk in. He is both taller and shorter than you expected—last time, you had both been seven years younger, and he is less spindly-looking. Your brother still has the lanky frame your bhaiya did then, and they are almost the same height. He’s older, you think, though you’re not sure why you’re surprised. Of course he’s older. You all are.

You expect it to be more awkward considering you haven’t spoken in the better part of a decade, and even though the three of you don’t really have all that much in common, words come easier than you could have hoped.

The last memory you have of the three of you, you were at your thatha-paati’s old house, sitting on the white plastic chairs on the veranda. The smell of jasmine was hanging thick in the air, the tree branches hanging through the gate. Wet clothes were hung up on pins in the sun, and you, your brother, and bhaiya were sitting in the shade under the fan. Your bhaiya taught you Slapjack, and he was better at it. By the end, your hands hurt from how competitive the game had gotten. Remember this, you thought then. Save it for later.

IV.

You are sitting on the couch two days later when your didi walks in. She had gone back for business school, one in another state, and you hadn’t expected to see her for the whole trip.

Maine jhoot boli, she says. I told my school my older brother was getting married so I had an excuse to leave. Bhaiya is younger to her. Didi doesn’t even have an older brother. She shows you the invite she had edited as proof for her lie, and you marvel at her cleverness. She was always good at lying, you think, but that was mostly when you played Bluff. You realize you barely know her now.

The earliest memory you have of her is from when you were five years old. You have one end of a dupatta in your little hands, and your big sister has the other end. "It’s the Time to Disco" is playing, and the two of you are moving the scarf up and down, up and down, up and down. It couldn’t possibly be that fun for her—she is seven

years your elder, but she watches you bounce your round knees, a grin splitting your face in two.

Maybe you don’t know her anymore, but maybe for now, you know enough.

V.

Delhi gets cold in the winter. The walls are not so insulated, and extra blankets are laid out for each of you. The sleeping arrangements get shuffled around to fit you all.

A lot of things are shut down, and there’s a curfew for being on the road, so you don’t leave the house too much this time. But you go to the parlour for a haircut, and while you don’t speak Hindi, you understand a lot of it. Why is the hair cut so unevenly? the woman cutting your hair asks, and you spend five minutes perfecting your sentence, how you would say it in Hindi. You’ve been taking a class at school. Maine baal khud caat liya, you want to say. The words are on the tip of your tongue. You try to move your mouth to say them, but you’re paralyzed. You’re scared of being wrong, and so you tell Didi in English. I cut the bangs myself. She laughs, and tells the woman that, exactly how you had rehearsed in your head and been unable to speak. You think about it all day.

You don’t leave the house much, but you visit Bodela. You, Amma, Athai, and your brother go and find him some good kurtas—he hasn’t had any good Indian clothes since he was ten. Amma buys you two saris, and the worker at the store had you stand so he could drape them on you, just so you could see what it looked like. That evening, you sat down on a stool on the street and had the mehendiwalas apply henna to your hands. You hold them over the stove to burn them into your hands, so it comes out darker.

You don’t leave the house much, but your athimber brings home aloo tikki from the street, and it is so spicy it burns your throat. You savor every bite.

VI.

You get another week before you head to the south. Coming to India means splitting time, and also that no visit is ever long enough. Didi will go back to school by time you get back, so you tell her goodbye for now, while the others get a see you later.

When you step into your grandparents’ house after the two-hour car ride from the nearest airport, tears prick your eyes. Paati would have come with the driver she sent to get you, but she can’t leave your thatha alone right now. It has been five years since you’ve last seen them, and a decade since you’ve last been there, and on the wall, there is a collage of pictures of their daughter—your amma—and some with your dad too. Mostly, though, the photos are of you and your brother. There is one with you and him sitting on the backs of two chairs in the room. Thatha and Paati are sitting on the chairs, and you and your brother are laughing about something, your little bodies lurched in opposite directions.

You wipe away the tears before your paati sees, and then give her a hug.

Thatha is lying down when you walk in, but when he sees you, he sits up. His tired eyes light up, and he smiles wide. There are sores around his mouth so his smile isn’t its usual shape, and you struggle to keep it together. You walk over to him, talking, and you want to give him a hug—but he looks fragile right now, and so you don’t. You wish you had for days.

You don’t remember much of Palakkad, but you remember this house well enough. You remember these chairs, and the beds you slept in last time, and the balconies. You, your paati, and your thatha in one, your amma and appa and brother in another. The beds are two put together, and now one of them is for your thatha in the living room so he has less to walk and is easier to watch. You and your amma share a bed while your brother gets the single. Paati insists on sleeping on the couch.

Just to make sure.

Palakkad is not as cold as Delhi. You’re in the tropics now, and some days are muggy as late spring back home. You stand on the balconies in their house and take in all the green. There is less pollution here, so the smell isn’t as memorable as Delhi, but the earth still smells like it belongs to someplace else.

It is more somber here, but the TV is on for a lot of the day as Thatha watches his shows, and it’s nice to have background noise.

VII.

You leave the house even less here. Your amma and paati take Thatha to hospitals, some of them in the nearest big city, where the airport is. The uncle across the hall has a cook now since his wife died a few years ago, and she makes extra food to give to you. On days when you and your brother are alone for a while, this is especially helpful, but less cooking for your amma and paati when they’re here is still good. They have enough to deal with.

VIII.

The event happens on Christmas. You missed the moment, having been in the shower, but when you come out to the commotion, they tell you to stay in the room.

Your thatha has been extra tired recently, but he fell. They call an ambulance to rush him to the hospital, and you and your brother assure your amma that you’ll be fine here overnight.

You spend the next day alone with your brother. The TV serials you’ve been watching with your thatha in the evenings don’t play on Sundays, but it’s so messy that you forget, and at 6:45 you turn the TV on for the 7pm show.

Instead the channel shows a movie, and it’s pachai Tamil, pure Tamil, which is not the dialect you speak. A lot of the dialogue goes over your head, but here is what matters: the main characters are in love, and he fights gangs, and when a gang kills him, his wife takes his scythe and cuts down everyone who hurt him. It is the best movie you have ever seen and ever will see. If that’s the grief talking, you won’t admit it.

Later that day, you go into a room and cry, and you play a song

from that movie on repeat until you stop. You listen to it obsessively the next few days. Next time you cry, your amma is already asleep, and leaving the room means your paati will see you instead. You put on your headphones and play it over and over as you stand in the darkness. The sobbing subsides eventually.

IX.

They send you and your brother back to Delhi a few days early. They don’t want to worry about you with everything else.

Your thatha is still in the hospital, but he is getting better—at least, from the reason he fell. The rest would be dealt with later, if it could. The hospital has really good chai, but the food isn’t the best, Amma says. You have chai as you say goodbye in the hospital and try to keep it together. And you fail.

X.

Being back in Delhi is weird now. You weren’t meant to be here so soon. It’s colder now than when you left, and your grandmother is always bundled up. She’s forgotten how to be cold here. She was never very good at it.

Your bhaiya has more now than he did, and Didi has returned to school. You’re trying to be normal, but you’ve forgotten how.

Your athimber gets the aloo tikki again. It’s still so good, but it’s harder to savor.

XI.

You spend New Year’s Eve on the building’s terrace. They have a bunch of newspapers saved up, because your family saves everything in case it could be useful, and you all help build a square with bricks wide enough to place an old kadai on it. It takes a second before the fire catches, and then it isn’t as cold anymore.

You’re head of music, and you choose ABBA because your other favorites are more controversial. This is an exaggeration, but you’re worried they’ll judge your taste in Hindi music. They’re your family— what’s the worst they’d do?

Your bhaiya and his uncle—but not yours—have a beer. This surprises you for some reason. He’s older than you, and you’re legal now, too. Of course he can drink if he wants.

After all the adults have gone downstairs, the three of you stay up on the terrace. You ask Athai if you can use more newspapers to keep the fire going when it starts to fizzle out, and she says Just don’t use all of them.

You go down to the ground floor and your bhaiya and your brother and you find every last newspaper stashed away and bring it up to set it ablaze.

The fire chases away the chill, but when it starts to go out, you try a sip of your bhaiya’s beer. It tastes like oil and battery acid, and you wonder how he’s on his second can, but it feels warm in your belly.

The day before you’re set to return, you go into a bedroom and sit on the floor in the dark and cry. Everyone else is in the main room, talking and laughing, and the thought of leaving hurts so bad that it’s all you can do to not make a sound.

Someone finds you after a bit, and you forget who it was through the tears. But your athai gives you a hug.

A few nights ago, your brother asked your bhaiya how much he liked Delhi. How would you rate it? One to ten.

Your bhaiya wasn’t sure. Between three and seven. Because the air quality is abysmal, and the crime is awful, and it is so busy all the time. And because it’s home

Your bhaiya asked you and your brother. He said four. There are always so many mosquitos, and the houses have weird heating. The air pollution hurts my eyes.

You say seven or eight. Because the air sucks, but when you’re away and you smell smoke, you think of Delhi. And it’s too hot in summer and too cold in winter and it’s not very safe, but you miss it like a lost limb. Every time without fail that you walk out of Indira Gandhi International Airport, you think I’m home. This is what home is meant to feel like.

A return.

And you know if you stayed here long enough, your rating would go down. You know it like you know your hometown, because you hate it a little, even while it’s the place you know best.

Delhi is the city of your childhood, it’s the one you remember most, it’s your safe haven after a day of uncomfortable travel and shitty food and shittier sleep. It’s the home you never got to keep.

You would hate it a little, too, if you lived here.

Yeh dharti apni hai. This earth is yours. It runs in your blood, races through your veins, beats against your chest. Your bones are made of it, and standing on it again grounds you. Fills in all the cracks. You’re more real here, somehow. You want to stay in a place where you can get lost in the crowd. You want to drag your siblings places, and laugh like you’ve never laughed before.

You want to breathe deep, be outside until the pollution stings your eyes.

Just enough to know that this is real. Tu zinda hai. You are alive. I would stay here until I hate it like the rest.

A star gasps forabreath, clashes with *bliss* *shock* *love* itsucksinair and sssssssqqqqqqqqquuuuuuuuuuuuueeeeeeeeeeeeaaaaaaaaaaaallllllllllssssssssssss!

hit an’th’r cosmic pounding, trumpet t o o t bass b o u n c e

bah bah bah bum de dum be bi di di beee bu buh tst tst tst tete puh pupp per prrrr pprapppa prap prrrrap prap-prap-prap heee na na naaanaa naaaaa twiii ti tet-te-tet tst tst

tah skee skr skr skee did krrr krrrkrrr krrr si si sisi skrr ksk---sk skee skee diddl duh dum du dumm duhdum dum DUM!

The star heaves n’ swirls with new-life: chaotic-peace.

i am a product of june 12, 1967. that day made me legal but it did not make me accepted

i spent my afternoons with the temptations with journey with biggie and steven tyler

i tamed my mane and let it loose

i rejected and accepted the gift my mother had no choice but to give me my mother, dark and proud gave me the beauty of this culture and the fears

if i told you i hated my hair and myself would you believe me?

if i told you some feel i’m contaminated would you believe me?

if i told you i’ve been called a niwould you believe me?

and if i told you that you are just as disappointing that you don’t see me as a member that you condemned me for loving someone who doesn’t possess the gift would you fucking believe me?

am i supposed to play into this trap? of my blackness and whiteness am i supposed to apologize for my blackness and whiteness?

who are you to say i can’t give my children this gift give my children this family, my family because their father looks like mine?

i would say you are the one who is contaminated. tainted with bigotry and hate

for i was created through love and i will pass this love to my children

so if this is tug of war, between father and mother i call a truce i can’t choose both are me and i am free

Listen online at windhover.bandcamp.com

All trees are mothers. It was a reality that Maple knew from the bottom of her roots to the tips of her leaves. It was a very uninspired way of thinking.

A few seasons ago, my breeze had blown over and witnessed the humans carve her a place in the soil. They paid no mind to the wind, even when I flung a few specks of dirt into their eyes. That was right before one of their buildings sucked me back up. There was no place for nature here.

It would be the first season that she seeded after getting planted and she was about as excited as a tree could be for the event. Which probably wasn’t that much, as trees are boring. All they do is wait around for stuff to happen. They’re not like ivy, who can spread within a few weeks or sundew, who can eat flies. Trees just sit and get slightly bigger every few years. It’s such a still life and I only find them interesting once I’m breathed in. That’s when I can hear their thoughts. Though Maple’s were always the same.

I’m so excited to meet you! She would wish for her budding seeds. Grow big and drop quicker. Maple was the single piece of nature in a bustling city, planted to contrast the faded gray municipal buildings. She couldn’t hear thoughts like I could, so she didn’t know why she was here. She only felt the constant vibrations coming up through the ground as people, transport, and machinery all scrambled together. Sometimes her isolation would be cracked by some weeds, obnoxious dandelions, or invasive crabgrass, but their lives were short as they were annoying. She couldn’t see that they were an eyesore, she only felt their absence in the soil. Trees are pitiful, blind creatures, aren’t they?

The fungi at her roots were her only constant. Well, I guess that

I could count, but she was unaware of my presence except for the times I whistled through her branches and tugged on her lobed leaves. She never seemed to think much about it. As I said, Maple wasn’t smart. It’s probably why the fungi felt bad for her, and would often tell their host stories. Her favorites were from the deepest part of the distant woods, where if a tree fell, only her sisters would mourn her. These trees grew wild off of unbound fantasies.

Tell me again. Maple would whisper through her roots. About the ones who move. Even with her branches heavy with green-sailed seeds, Maple was worried that they would be taken from her when the time came for them to fall. So she wished for ways to protect them or follow them to wherever they went. It was pathetic.

Then, probably swayed by the depressing display, the microscopic tendrils would echo the wildest trees.

Once before the first were chopped, we could uproot ourselves and move freely through the hills. All of our roots were aerial, like the orchid or the mangrove, but we could move quickly, like the fastest vines. We were always attached to the earth, but within a day we would have moved miles, our roots leaving a trail for others to follow. Some of you will say that having our roots unprotected would allow them to rot or get cut or eaten. You would be wrong. Our roots back then were as strong as steel and could push through rock. If somehow they were cut or broken, it would be like a twig snapped off of one branch out of many. We protected the forest, because we were the forest.

Then, one day the humans grew annoyed. Our roots had spread everywhere and our great canopies that shaded the ground stopped new growth from appearing. So they buried our roots and pruned our leaves, making us much smaller and more manageable. But in times of great stress, we can grow like that once more.

A ridiculous story made worse by how much faith Maple put into it. Every night, once the sun stopped touching her leaves and most of the rumbling stopped, she would sit and revel in the feeling of the heavy seeds weighing down her limbs. I would become a dryad for you. She whispered to her children, knowing in the pith of her heartwood that it was true. Get it? Pith of her heartwood. Because she’s a tree?

Anyways, days went on and Maple remained useless. Trees like Maple only have a purpose when cut or used as a set piece for far more interesting stories. Not to say mine is more interesting. Things that are trapped in the city become reliant on it and, to my endless frustration, I am subject to this rule as well.

As they grew, Maple continued to worry after her seeds. She was both excited and terrified for the day they joined her in the soil. What if they succumb to rot? Or the skittering claws reach for them? I hope they grow even taller than me. Please, reach high into the air, my little ones. When the first one broke off, one that hung off the tips of her branches, she couldn’t see its whirling flight to the ground. She could only notice a miniscule weight off her boughs and rejoice in the fact that she may soon have a companion in the soil.

But the feeling of wings and the hard shell covering of seed never came. Maple remained hopeful though, believing that she was too big to feel such a small intrusion. Worst case scenario, it had been blown too far away. Like I would ever help spread her offspring. She deserved to figure out that there was no fun or desires to be had here.

But she kept hoping. Three more seeds fell, then a whole clump of them, then a whole branch, then all of them. Yet, she could feel none of them nestle into the earth with her.

Maple was devastated and confused. Yet, there was a simple answer to this. As she was a decorative tree, meant to trick passersby into thinking that they weren’t in an inescapable labor maze, concrete surrounded Maple on all sides. Her seedlings were all right beside her, but she’d never be able to feel them thanks to the trash-stained rock between them and the soil. Even those who landed at the base of her soil couldn’t connect with their mother. The dirt had been packed firm beneath the feet of people too lazy to go around the tree.

I flicked a few of the closest seeds deeper into the ground. Not to help her, just to see what would happen. But it was too little too late, they had been thoroughly tread on and were broken husks of what Maple had hoped for.

No! The power of her grief echoed from her roots, through the fungi, and out into the far woods. Not a single one of her children would be planted and she was powerless to help. I breezed through her fruitless leaves, whispering all the while. C’mon, Maple, turn into a dryad. A few weeks ago you said you would do anything for your seedlings. But she was only a tree, like I was only the wind, and a case of motherly anguish wouldn’t be undoing the work of her cement cage anytime soon.

against the plaza sidewalk. It was aggravating to watch. She was a tree, so I knew she couldn’t stop herself from blooming—not while there was sunlight and water to thrive on—but it was beyond stupid to see her get all mushy with unfallen seeds that would never survive.

Maybe this year. Maple would pray as she felt her limbs grow heavy. Then I would whisk by, the smog weighing me down and keeping the seedlings from scattering far, and she would be alone once more. Maple’s roots would push against the concrete, but they were too weak to break through.

This constant back-and-forth was always silly and I loathed her; praying that one day I would blow past and find her a husk. Existing would be easier then. I could allow myself to be pulled from the outside and into a vent system, where they’d chill me or warm at their pleasure before spitting me out again. I could allow myself to remain cramped inside small buildings and alleys. I could allow myself to become greasy, unwashed, and never wonder what it would be like to soar high or be free from the city.

Everyday, Maple still managed to cling to her fantasy of motherhood, asking the fungi to repeat the dryad story when the world was bleak. She was already growing bigger, but through sheer force of will, her roots grew stronger, her bark was more flexible, and she bloomed more often. She was the fastest growing tree around, but then again, she was the only tree around.

I watched her for years. There wasn’t much else for me to do. The city confused and confined me. The humans had tamed me with their unshakable buildings and windmills that made me—the free, roguish wind—do their labor and create their energy. I stayed near Maple, because she was the only thing natural within miles. Pardon the joke, but she was a... breath of fresh air. Sometimes I would whisper to her, but who knows if she heard me. We both understood in different ways. Give up, Maple. I can’t help you plant your seeds. They will always die. One night, I told her. You won’t ever be a mother. They won’t let it happen. It was late fall. All her leaves and progeny were scattered around her, much of them had been stamped to a dust, and maybe she could feel my frustration rustle her branches. Her thoughts quaked into a singularity:

I can’t abandon this dream.

Seasons passed and every summer a little hope would twine its way through Maple, and every fall that same hope would be dashed

Roots burst through fissures in the concrete, fibrous veins tangling in the moonlight. Grasping branches grew out of Maple’s trunk. They weren’t hands, but they could hold just as well. Her bark became more flexible, or rather, everything under the bark had become more flexible in service to Maple’s wish. Her canopy blotted out the moonlight, but she didn’t need eyes to find her little ones. All she had to do was stretch her roots to find where they had gone. To my amazement, she didn’t start breaking buildings and shattering glass with her immense branches. She simply bent down, limbs cracking with the unnatural movement. A few branches fell off, but they grew back immediately as she picked her dried children up.

She would slide her roots across the ground, causing layers of sidewalk-ridden detritus to stick to the little hairs. Maple could finally feel her family and they were pulp. Even the mostly whole ones were stillborn, with sails torn and seeds shattered. Yet that didn’t seem to matter to Maple.

She would brush them together and draw them in close, letting the tendrils from her trunk carry the ones who could be carried and resting her roots on the ground-up infants. She did this like it was a comfort, but if it was for the seeds or herself, I couldn’t guess. Throughout this process, I remained motionless. She had done it. Maple had become a dryad.

Once she finished picking up her lost children, she shifted forward to grow out of her plot.

She froze.

I swirled around her, being careful not to tear her carefully collected treasures out of her hands, as I tried to discover the nature of this stillness. Then, I stopped. It wasn’t a lack of movement that paused her. It was a lack of power. No. We both exclaimed in our ways. Her roots tensed. I blew a cold breeze. I’m never going to be a mother. She thought.

I’m never going to be free. I thought. I became a gust, throwing her seeds into the air. Little wind, please don’t! But I ignored her and pushed them as high as I could. If I can raise them high enough, maybe they’ll scatter. Please. Let them scatter far. But I was too weak, I was too weighted, and they only got a story high before they fell back to the ground.

Little wind, please blow away. She wasn’t talking to me. There was no way. I could only understand her because I blew through her. Still, she kept pleading. Little wind, there’s nothing for you here. Little wind, rush away. I have nothing more to give.

Did Maple blame me for the demise of her children? It wasn’t my fault that her seeds were so easy to send drifting! She wasn’t the only one trapped. Didn’t she understand that on the days when I was too heavy, when I couldn’t rush through the city streets sending clothes into a flurry and goosebumps into skin, helping her seeds float was my only joy? Maple! Please hear me! But I, the blustering, impractical, pitiful wind, didn’t have a way to speak and she didn’t have a way to listen. I rustled her leaves frantically, begging her through action to understand. Then, I flew through her lenticels, the scars she breathed through, desperate for some sign she understood.

This isn’t my fault. Please believe me. I wanted them to live! She didn’t respond. From below, the fungi spoke to her.

Once before the first were chopped, the dryads protected the forest by harboring life for others. The humans–

Stop making me hope! Maple shook with grief and I was wheezed out. It was clear that she had wanted to wash the fungi off her roots and silence their porous voices. They were too filled with the thoughts and stories of trees who could grow how they pleased. There was an aura around her as insidious as any rot. She had finally seen that her wish was impossible.

frightened me. My own existence wasn’t that happy, but Maple had become a symbol. Her attachments seemed far-fetched, but I loved the splash of color they provided against the gray. Without them, I felt washed out.

I must admit, though I had craved this reality-check for so long, it

The winter was long and while I usually loved chilling people with a harsh gale, I was too aware of the bare tree nearby. Nothing I did seemed to matter for long anyways. It was a warm winter with no snow for me to flutter around. Most of the buildings had heaters going in full force and the warm ejected air made me uncomfortable. Sometimes, I would check in on Maple, but it was like going into a hollow. There was nothing except for a few cobwebs of untethered thought.

What do I do now? I couldn’t save any of them. I promised. Even as a dryad... there was nothing there. What is wrong with me? If I had transformed sooner... It was burdening to witness her pain, so I let the vents and open doors inhale me when they could. I did my best to lose myself in the torture of temperature control.

It was better in the spring. People didn’t feel the need to use air conditioning or heating and sometimes I would hit a warm patch and shoot up into the sky for a few moments. From up there, I could see all the birds coming home to roost. The polluted air always dragged me back down to the buildings below, but that brief glimpse at the endless sky would hearten me and I would return to Maple in a puff. Now I was the positive one.

Her leaves had returned and though the humans had managed to fix some of the damage to the concrete, she was still a dryad, if not a frozen one. Many people came by to wonder at her verdant canopy and watch the way the light came through her leaves. This did nothing for her emotional state and while her grief had diminished some, it had been replaced with anxiety.

After spring, it’s summer, and then it’s autumn. Two seasons until I have more seeds. Three until they’re all dead at my roots. I can’t do it again!

There was not much I could do except gently ruffle her leaves. Sometimes she would notice and whisper.

Little wind, you do not need to always come back. I am sure you are very busy with your travels. It must be a nice pastime; rustling the skies. Even if I could speak to her, I would have not told her the truth of my existence. It’s definitely more than ridiculous, but I was hopeful so that she would be hopeful. I made sure to promise myself that once she was back to normal I would return to my mischievous pessimism and all would be right with the world.

home on one of Maple’s branches! I was careful not to jostle it as I visited. It wasn’t a very large nest as it was created out of Maple’s fallen twigs, feathers, and a few strands of hair. However, it was big enough to hold four speckled eggs. Usually, I don’t mind testing how well a nest can survive a gust. But something stopped me. It could have been because their color reminded me of the sky on its best days, when I could float high above the city and get lost in its vastness. Or it was because I was tired of death wreathing Maple’s surroundings.

Maple could feel the tapping of the parent’s feet on her bark, which wasn’t new, but she was uneasy with how long they had remained there. I couldn’t tell her about the new residence, but luckily the scared worms by her roots told the fungi and they transferred the information.

I’m not safe. Nothing is safe around me. Maple worried everyday that the comforting weight of the eggs would disappear, smashed onto the ground like so many others. She wanted to warn them away, but she didn’t want to hurt them. So there she remained.

For my part, I slowed my gliding around her limbs. It’s against my nature to be delicate, but I did my best. Luckily it only took a week or two for chirping to emanate from the nest, cracked blue shells empty. Maple could feel the hatchlings shifting and squirming. She tried not to get excited as they grew.

I’m being silly. She thought as I passed. They won’t make it through the summer. Some animal or storm will get to them. Little did she know that I blew off any predator that tried to attack the robins. This task kept me nearby as Maple was overrun with life. Her larger form was a sanctuary for the local mice and rats. Squirrels made homes on the top of her canopies. Insects crawled through her cambium and the fungi flourished as the shade kept the ground damp.

C’mon, Maple. I would whisper as I brushed the points of her leaves. Have a little hope.

worry, I shifted and pushed against the little bird, bringing it back to its nest. He seemed fine with it, still unused to being in the air.

Maple relaxed slowly, at first believing it was another bird who had landed on her perch. It can’t be. They never come back. They never survive.

My giggle was an exhale of warmth. He lived!

The tiny trickster wasn’t done yet either. He had enlisted his siblings to practice while their parents were out. They all jumped off the branch at once, some were unsteady, but I held them and they flapped quicker to gain some height.

This time I lifted them higher and danced with them in the sky. Their delight was obvious as they spun in the midday sun. They weren’t flying to escape or hunt. They were doing it because it made them feel happy. Because it made them feel free. I was surprised to find I wasn’t jealous – I was content. If I had known it would be that easy to throw away my dreams, I would have herded some birds onto Maple’s branches much quicker.

Eventually, the fledglings grew tired and we drifted back down to the tree below. Maple was relieved to feel eight miniscule feet descend on her limbs.

Fly far, little ones. She prayed. The drumming of life running along her body finally seemed obvious to Maple. Above, cankerworms nipped at her leaves, growing big off her greenery. Below, mice raised their young. Birds feasted on the small creatures in this mini-ecosystem. She was the shelter for so many and helped everyone survive. The words of the fungi colony echoed through her veins. The dryads protected the forest by harboring life.

All trees are mothers. It was a reality that Maple knew from the bottom of her roots to the tips of her leaves. And there, with the golden halo of sunshine glowing through her leaves, alighting her veins and making her radiant against the colorless backdrop, she had finally achieved it.

It took a few more weeks for the baby robins to attempt flight. The first hatchling was an eager one speckled light brown. He leaped into the air without fear and I rushed to catch his outstretched wings.

No! The baby fell from her boughs. But then he took flight.

I tried to let Maple know, but she was too panicked to feel my gentle breeze. She could only recall the drop in weight. Not wanting her to

Mairead Maley

Fate, if you have good aim and a good arm

Send me off to life like a baseball

Throw me up in the air and hit me hard that I might be caught by someone strong enough to catch me Or land near somewhere far away from here

Gentle wind farms with their mile-wide wings Could help to cast me further skyward

Perhaps I will hitchhike in the maw of some bear Accompanying the sweetness of his berries I could endlessly roll the Piedmont hills and up Bavarian peaks

I’m not as delicate as I seem to be No gauzy bubble floating in a current I’m molded from the good stuff that lasts I’m wrapped with thick leather and elastic lace

My core is red clay from the Haw riverbank

Now you see I’m made for this challenge

So don’t be afraid to afraid to throw fast and far For, like a baseball, who are you at the end of life

But all those who have touched you

And the fields you have landed in

Ben Pricetake a finger at a time, no, make it a digit set the blender on medium once the whole hand is smoothly churned into a thick red paste add half a cup of olive oil and 2 fat cloves of garlic set blender on high remember those fat reserves? Yeah use a teaspoon of those, then take a pan and preseason with that fat slap your slime in the simmerin' saucepan and slosh the slop around a while

apply heat, time, philosophize about the way she screamed and what that means for your soul I also advise a sprig of rosemary and 3 basil leaves Don’t forget, salt to taste! boil pasta according to box be ready to eat.

Anthony Ramsey

Gay is, Gay ain't

But what am I?

What Am I?

I ain’t...

I tried, I truly tried

I thought if I pandered,

Got on my knees and was a good boy, I could be gay

But I ain’t

I ain’t skinny enough

My body does not fit "gay"

I have too many curves

My skin stretched and bears the marks

I have hair but not enough and I am also not smooth

But more than that,

I am not white

That was my plight

The thing that haunts me at night

I gave into my desires

I gave my body to men who turned their eyes

I sold my soul to that word

Over and over again

Because I wanted to be it

Because I wanted to be in

And so I tried to conform

Yet I was never enough

And when after came

I felt like my body was diseased

As though the hands of death came and touched me

Soiled me

Crushed me

Beat me until I was broken

And I was broken

And my pieces stolen

So when I looked in the mirror

I saw nothing but hatred

For my love

For my skin

For myself

I could never be enough, could I?

Never masc enough

Never muscular enough

White enough

Gay enough

So I cried and hated myself

I lied and said things would be okay

Waited for love from another but it never came

Because there was a dark hatred inside that told me

I was not enough because I ain’t

But in time

I started to think of what I am

I thought

And sought

And finally those long nights brought to me something hard fought

And when I found it

The answer

I dissolved into pure ecstasy

An essence of myself that glowed so bright

It blinded

Black joy so brilliant, so beautiful

I didn't recognize the skin I was in

Because I loved it

Because I no longer saw a plight I saw a blessing

And finally

At last

I was me

Uninhibited

And I could say to myself

I am black I am gay

I am the masculine and I am the feminine

I walk a line in the path of my ancestors

I am their wildest dreams

But furthermore, I am an embodiment

Of things more than a hollow syllable

Because

Gay is, gay ain’t

But I am

Marlas Yvonne Whitley

I read Annie Allen in the twilight of my day And wore Brook’s words like a necklace The thoughts raced by Demanded I follow

But I read Annie Allen in the twilight of my day And will now go digging for Those silver stars

Content warning: This piece contains explicit content that refers to suicide and self-harm.

can hold so much air, because the lotus flower, blooming in muddy water was more like a boy falling in reverse because the four students who died this year, were not trying to jump but merely, wanted to fly and the truth is, there is no truth. we heard you, we heard all of you but never sought to listen to the mouth quenched of thirst like the sentence demanding to be stopped maybe, the period is only a symbol that something was once here that no matter how close you are to a thing it’s the eyes that will fail you first. that, the body. Alone is not enough. That yes the earth is small

but the heart is smaller. That yes, we want a home but sometimes we are only able to build a shelter. But don’t stop. Keep looking. Hear beyond the flesh. Capture the eyes soft and still like blades of autumn caught in fields of rye. Find warmth, in the moving. The temporary. Find warmth, in the beauty of self-love even if it only be briefly. Even if the war inside you has already ended. Keep fighting.

Because someone out there will love you for who you are and not who you tried to be. Because even the faintest sounds deserve to be heard.

1.

Port and almonds sugared with white lead a staring dollar of mercury eye on the back of the hand a moment suspended before worrying into the flesh

2.

The seething lamplight of poison asphalt lake of the matron’s face

the burning coal has smoldered into the flesh’s white ash

3. White lead and mercury to burn the diamond out of the flesh the diamond seated in the bone

the grain in the mouth of the chorister face down in the canal

Jules Millward

Smooth the rippling temples sear pressing prints to mold and smear

Atoms contract and together bind

This brevity husk is boiler lined

The throbbing thrum comes in waves

pinprick dark stars burst and cave

Snuff the frequency, man the taps

Shuffle out and soon collapse

Nicole Shearon was a volunteer for this volume. As per our Submission Policy volunteers are not permitted to take part in the review of ther submission(s) to prevent subjectivity and bias. The acceptance and consideration of their piece(s) is decided by the editor in chief based on a pre-established critique process.

Last night’s kisses are now a small wave of a whisper. I bite back the urge to wake you, to stroke the horizon of your moon jaw. You were never a morning person, and here, under an ozone of polyester and cotton, I think of all the ways to buy your time before you leave me: I’ll burn the bagels for breakfast, pick a fight about the color of the cabinets. Tell me, again, how you spend your days, about your computers; they’ll take you to Mars where you’ll build skyscrapers on its mechanical skin while I sit in this yellow wallpaper room. The sun can know nothing of the lilac midnight.

Howdy

She said,

But her hands did not quite fit my cups

And the red dirt below her nails tasted warmer than grit. Hats were not our limits but nights under stars couldn’t contain what we felt. I know I’ve dreamt of her.

Pick me flowers in the echoes of your inners

And let them smell of sweet sweat and hard-earned victories. Heat like this saturates through the day, soaking by the summer night. I was battling dogs of past love and dragging around books That were empty except for her words.

There is nothing tender about the way her spirit feeds mine, nor soft in the way our cheeks chew on each other’s thoughts, Let your creek always, always, Find a way to flow into mine.

Sruti BontalaI lace each cloud in the sky with my misty breath and I long for my words to rain down upon me.

The earth in my heart has been barren for so long that I wake up early every morning to catch any sweet morning dew on my tongue.

But, when I look in her eyes, I see rainforests blooming and sometimes when she comes close enough her scent fills every crevice in my being, Until I can only see water lily ponds in the sky and in the sea thick with her honey-laden sweetness, and until she covers my skin with her milky humidity.

How can I hate her and her grace? A single drop of her laughter can grow an oasis in my heart.

And so I look from my desert land at her greener grass and I watch the clouds move like tides in the ocean sky and I pray for rain, at last.

Sruti Bontala was a volunteer for this volume. As per our Submission Policy volunteers are not permitted to take part in the review of ther submission(s) to prevent subjectivity and bias. The acceptance and consideration of their piece(s) is decided by the editor in chief based on a pre-established critique process.

the first time i ever got properly drunk was in a house that i had never seen before, with boys who i couldn’t even pretend to know

they had plastic cups with flowers on them i wanted to think that someone had bought them for a picnic even knowing that no one in this house had ever considered going on a picnic without trying to impress a girl. but they had blue and pink flowers that looked happy, whimsical—i traced them over and over again; fingernail following the lip of the paint around careful not to lose my place, not to jerk my thumb or i’d chip the petal, scratch the paint, scratch the record of a memory.

it was his dad’s house: the boy who had invited us. he was my roommate’s first ex-boyfriend and it all felt forgotten untouched till four boys and a bottle showed up to play darts over spring break.

in my memories, everything was in perpetual motion: music so loud that you could feel the air vibrate around you, lulling you into a warm sound bath of grunge rock, alternative chatter.

the memories are hazy now they poured us drinks: four freshmen at virginia tech and two seniors at a boarding school where everyone swore we were older than barely seventeen.

we lived our whole lives before we could drive.

lemonade and coconut, less lemonade than rum but i didn’t really ever taste it. until years later, until college until it came back up.

in the early stage of the pandemic there were shortages all the time. i worked at a grocery store and when they could they bought hand sanitizer in bulk for their employees made at distilleries with a high alcohol content to kill off bacteria even if it dried out your hands.

the first time i pumped it onto my hands i smelled the sickly sweet coconut, felt my stomach lurch back into a memory, leaving my body behind in the present.

without my mind’s consent i made a face, twisted my mouth in revulsion of a younger self’s wild behavior and weak stomach.

they were nice guys—hadn’t meant to get me that drunk, hadn’t meant to make me sick with sugary drinks and not enough to eat before.

they didn’t think my roommate would bring someone who couldn’t handle liquor.

my work best friend laughed at me, i hadn’t realized i’d gone sickly pale holding the bottle out, as far away as my arms could push it. she giggled, "we’ve all had a bad night in malibu."

Her eyes are thick with green wonder as she lays cusped on the sill of the garden room and traces the wings of the summer sparrows with her biting gaze. white-throated, song, chipping all litter the lawn, but she does not know the difference, nor care.

She does not know of the coyotes or the stray dogs that lurk in the woods behind the house, waiting with marble teeth. How the year before the neighbor’s cat escaped from the safety of their wooden porch. It was found a week later; its organs, a basket of red fruits, spilled against faded pavement. She did not watch the way its mother had to carry the dead thing home and bury it in black earth.

For her, life is like waking to a world blanketed by white snow, its beauty begging to be softly marred.

Nicole Shearon was a volunteer for this volume. As per our Submission Policy volunteers are not permitted to take part in the review of ther submission(s) to prevent subjectivity and bias. The acceptance and consideration of their piece(s) is decided by the editor in chief based on a pre-established critique process.

Bella Woods

He sits beside me on the floor, his head down, his back stiff, shoulders strained. His chest heaves, with quiet, barely suppressed sobs. I wait for him to dare a look up into my face.

Rug, plush and silken, rubs against my shins, my knees, the wall a hard slab against my back. The whirring screech of the kettle from the other room cries high, above my head. The crinkled remains of a cardboard box lid catches the corner of my eye. It was to shield his things. The things he kept from me. The nights he stole away on a weekend trip with his "brother" or a "business deal." I was blind then. I can see now.

He remains on the floor, and I stand. He flinches, but does not look up. I trudge to the other room, away from him, from the space gulching far between us. He can sit if he likes, sit and wait, while I pour the tea and stir, the withered leaf-flakes dissolving fast in the boiling water.

A wooden tray sits on the counter beside the kettle, the dark, deep knotholes staring, gaping out from the pale, gleaming sandalwood—a present from my father from a long time ago. My mother carved it, created its delicate framework with her own hands in her shop beside our house. Scrolls and curlicues of transparent wood shavings piled to her ankles as she carved, and sanded, and gingerly coaxed the shape of the tray from that monstrous piece of wood my father hauled in one day. She liked to think of herself as some kind of modern, wood-making Michelangelo, always discovering the life imprisoned beneath the heart of the wood.

But it was my father who finished the tray; it was he who gave it to me that Christmas when my mother died.

Now, I heap sugar into the swirling cups of tea, steam piling high as the wood shavings. Placing the cups on the tray, handles facing the same way, I return to the other room.

The journey back is long and arduous and only two steps from the counter to the living room.

"There’s tea," I sing out.

My partner—now a stranger—glances up a brief moment, the crinkles beside his eyes limping downwards, his lips plummeting into a frown "Shouldn’t waste the gas."

I place the tray on the ground between us, take up my own cup

between my shaking hands. He reaches out, muttering under his breath. We drink, he and I. Slurp in the hot, fragrant tea in silence, the house around us empty. Cold. It had been that way ever since he had moved on. From our future home, from our future life together. From the nights we could have sat together on the couch and just waited for the sun to drop below the horizon, so that we could rest in the embrace of the dark, and the embrace we would give one another. He throws back his head, swallows, arranges the cup on the tray. Grimaces. Swipes at his mouth with the back of his hand. "Water tastes like iron."

I shrug, take another sip, pummeling the suggestion of that metallic tang as the liquid rolls burning and sweet down my throat. "That can always be fixed."

He holds my gaze for the first time that day, speckles of his tears clumping his lashes. Fingering the delicate handle of the teacup on the sandalwood tray, his eyes flick up, hold mine.

"They were hers too, weren’t they?" the words crumple, broken and hushed.

I nod, trace my finger along the rim of the cup. Light glints off the porcelain illuminating the crisp, blue designs chased over the surface. My mother would only use them on special occasions. Church functions. Birthdays. Christmas. I attended, celebrated, but she was distant at those functions. Imperial. But it was her hands that carved out that tray, and all my love with it.

"Have them," I say. "I don’t have room anymore."

Policy

Windhover considers artistic work for publishing across many mediums created by NC State University students, staff, and alumni. Editorial staff, alongside their committees, review submissions with particular criteria in mind and then choose their submissions for the annual magazine. Submissions do not reflect the opinions of Windhover, Student Media, or NC State University.

For submission guidelines, please visit windhover.ncsu.edu

©NC State Student Media 2023

307 Witherspoon, Box 7318, Raleigh NC 27695 919.515.2411 | windhover-editor@ncsu.edu