BRENDA RAE, SOPRANO WITH BÉNÉDICTE JOURDOIS, PIANO

THURSDAY, MARCH 7, 2024 | 7:30 PM

Collins Recital Hall at Hamel Music Center

THURSDAY, MARCH 7, 2024 | 7:30 PM

Collins Recital Hall at Hamel Music Center

The Wisconsin Union Directorate Performing Arts Committee (WUD PAC) is a student-run organization that brings world-class artists to campus by programming the Wisconsin Union Theater’s annual season of events. WUD PAC focuses on pushing range and diversity in its programming while connecting to students and the broader Madison community.

In addition to planning the Wisconsin Union Theater’s season, WUD PAC programs and produces student-centered events that take place in the Wisconsin Union Theater’s Play Circle. WUD PAC makes it a priority to connect students to performing artists through educational engagement activities and more.

WUD PAC is part of the Wisconsin Union Directorate’s Leadership and Engagement Program and is central to the Wisconsin Union’s purpose of developing the leaders of tomorrow and creating community in a place where all belong.

THURSDAY, MARCH 7, 2024

Franz Liszt (1811–1886)

Francis Poulenc (1899–1963)

Richard Strauss (1864–1949)

Sergei Prokofiev (1891–1953)

Franz Schubert (1797–1828)

Comment, disaient-ils, S. 276/2 (1849–1859)

Es muss ein Wunderbares sein, S. 314 (1852)

Bist du, S. 277 (1844)

Wie singt die Lerche schön, S. 312 (1855)

Oh! Quand je dors, S. 282/2 (1849)

La courte paille (The Short Straw), FP 178 (1960)

Le sommeil

Quelle aventure !

La reine de cœur

Ba, be, bi, bo, bu

Les anges musiciens

Le carafon

Lune d'avril

Die Nacht, Op. 10, No. 3 (1885)

Befreit, Op. 39, No. 4 (1898)

Muttertändelei, Op. 43, No. 2 (1899)

Schlagende Herzen, Op. 29, No. 2 (1895)

Frühlingsgedränge, Op. 26, No. 1 (1891)

The Ugly Duckling, Op. 18 (1914)

Liebe schwärmt auf allen Wegen, D. 239/6 from Claudine von Villa Bella (ca. 1815)

Heimliches Lieben, D. 922 (1827)

Du bist die Ruh, D. 776 (1823)

Vergebliche Liebe, D. 177 (1815)

Lied der Delphine, from Zwei Szenen aus dem Schauspiel “Lacrimas,” D. 857/1 (1825)

In Classical music, German lieder has long held a central position as an emblem of the highest synthesis of music and words in what is more broadly termed “art song.” While it remains valuable to question which traditions are centered and which are marginalized, lieder— and specifically Franz Schubert’s more than 600 songs—nonetheless represents a remarkable achievement, and as a result, it has long been the yardstick against which later composers have been measured (as with Liszt and Strauss on tonight’s program) or the monument they aimed to decenter (as with Poulenc and Prokofiev).

For all its musical import, lieder as we know began with poetry. In the 18th century, German writers aimed to make their works more natural by focusing on descriptive realism and, in some sense, radical honesty. What emerged was not just a new more accurate reflection of the world, however, but also a focus on the heroic role of the individual in the face of a vast and indifferent universe—as captured in the works of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. For its part, lieder—as illustrated in the works of Goethe’s close friend Carl Friedrich Zelter—rendered music subservient to the text for the sake of naturalness by emphasizing the formal clarity of the rhetorical structures (e.g., meter, line, rhyme) through strophic forms (e.g., verses: the music is the same but the text changes).

—Eric LubarskyFirst gaining celebrity as a piano virtuoso before turning strictly to composition, Liszt’s public persona went beyond his everyday world as his image became entangled with and recruited into many of the major social and aesthetic issues of the day: notably, the rising nationalist movements, which claimed him as Hungarian and German, and then the ascendent New German School, as an acolyte of Wagner and an advocate of program music.

Standing in contrast to all of that are Liszt’s songs. For Liszt, who inherited the genre as transformed by Schubert and expanded by Schumann, lied was an emblem of cosmopolitanism (and not specifically “German” in the nationalist sense). This is first and foremost noticeable in the different languages he set (on tonight’s program French and German, although he also set Italian), but also, and regardless of the language of the text, his lieder mixed German, French, and Italian musical elements freely and indiscriminately. Although he was often critical of his own lieder as too sentimental, the texts he selected allowed him to nonetheless explore in miniature his interests in transcendental philosophy and duality in contrast to his epic instrumental works.

In his songs, Liszt maintains the Romantic hallmarks of subjective experience, emotional depth, and philosophical profundity, all of which are encapsulated in the earliest work “Bist du.” The speaker lists the contradictory elements of the beloved, from warm and inviting to cold and distant (which Liszt dramatizes with a modulation to minor), before concluding that the beloved hails from the farthest reaches of the universe. Continuing the theme of transcendent love, “Oh! Quand je dors” portrays the transfiguration of the male narrator from lustful desire to soul awakening, as the music for each stanza illustrates the transformation. In the discursive “Comment, disaient-ils,” the pointillistic staccato piano conveys the man’s anxious questioning, while confident legato chords emphasize the woman’s calming one-word answers. His later two works “Es muss ein Wunderbares sein” and “Wie singt die Lerche schön” return to strophic form. In “Es muss ein Wunderbares sein,” the music’s matter-of-fact declamation undercuts the effusive love language of the text; yet, Liszt underlines the two lines that focus on the couple’s interaction by repeating the text and accompanying it with ascending chromatic modulations. In “Wie singt die Lerche schön,” the strophic form throws into relief the text’s duality: Each stanza offers a different interpretation of the feelings and expectations conjured by the sunrise.

"Comment," disaient-ils, "Avec nos nacelles, fuir les alguazils?"

"Ramez, ramez!" disaient-elles.

"Comment," disaient-ils, "Oublier querelles, Misères et périls?"

"Dormez, dormez!" disaient-elles.

"Comment," disaient-ils, "Enchanter les belles sans philtres subtils?"

"Aimez, aimez!", disaient-elles.

"How then," murmured the men, "Can we with our sails, flee the alguazils?"

"Row," murmured the women.

"How then," murmured the men, "Can we forget our quarrels, miseries and perils?"

"Sleep," answered the women.

"How then," whispered the men, "Can we enchant the beautiful ones without subtle potions?"

"Love," murmured the women.

Es muss ein Wunderbares sein

Ums Lieben zweier Seelen, Sich schliessen ganz einander ein, Sich nie ein Wort verhehlen, Und Freud und Leid Und Glück und Not So miteinander tragen, Vom ersten Kuss bis in den Tod Sich nur von Liebe sagen.

Text by Elim

Petrovich MeshcherskyMild wie ein Lufthauch im Mai, rein wie die Perle im Meer, klar wie der Himmel in Rom, so still wie die Mondnacht bist du.

Kalt wie der Gletscher der Alp, fest wie der Felsen, der Fels von Granit, ruhig wie's Wasser im See, wie Gott unergründlich bist du!

Denn aus den Sphären des Lichts, denn aus den Welten der Schönheit und Liebe,

denn aus den Höhen des Alls, denn aus den Tiefen des Seins kommst du!

There must be something wonderful about the loving of two souls, locking each other wholly in, never hiding any word, and joy and sorrow, happiness and misery thus bearing with each other, from the first kiss unto death, speaking but of love together.

As soft as a May breeze,

As pure as a pearl in the sea,

As clear as the sky in Rome,

As quiet as a moonlit night are you.

As cold as a glacier in the Alps,

As strong as a cliff, a granite cliff,

As tranquil as the water in the lake, As unfathomable as God are you!

For you come from the spheres of light, From the realms of Beauty and Love,

From the heights of the universe, From the depths of existence!

Wie singt die Lerche schön

Im Tal und auf den Höh'n, Wenn der Morgen graut, Und die Blümlein Frischbetaut, Harren auf den Sonnenschein!

So sing, mein Herz, nun auch Beim frischen Morgenhauch. Hast du auch gewacht

Unter Gram und Pein

Diese Nacht— Dein auch harrt ein Sonnenschein.

How beautiful is the lark’s song

In the valley and in the mountains, When the morning dawns, And the little flowers, Freshly covered in dew, Await the sunshine!

So sing as well, my heart, In the fresh morning breeze. You too have stayed awake

In grief and pain

Last night— You, too, await the sunshine.

Oh! quand je dors, viens auprès de ma couche,

Comme à Pétrarque apparaissait Laura, Et qu'en passant ton haleine me touche ... Soudain ma bouche S'entr'ouvrira!

Sur mon front morne où peut-être s'achève Un songe noir qui trop longtemps dura,

Que ton regard comme un astre se lève ... Et soudain mon rêve Rayonnera!

Puis sur ma lèvre où voltige une flamme, Éclair d'amour que Dieu même épura, Pose un baiser, et d'ange deviens femme ...

Soudain mon âme S'éveillera!

Oh, while I sleep, come to my bedside,

As Laura appeared to Petrarch, And in passing let your breath touch me ... All at once I shall smile!

On my somber brow where perhaps there is Ending a dismal dream that has lasted too long;

Let your face rise like a star ...

All at once my dream Will become radiant!

Then on my lips, where a flame flutters, A flash of love purified by God himself, Place a kiss, and be transformed from angel into woman....

All at once my soul

Will awaken!

Like Prokofiev, Poulenc was, in his youth, a rebel. Unlike Prokofiev, he was more convivial with his artistic peers. A member of Les Six, Poulenc sought to strike out in radical new directions while also writing approachable music, and his special gift for melody went a long way toward accomplishing that goal. Les Six espoused a strong anti-Romantic stance: They wanted music to be agreeable, light, and stylistic, in contrast to the (German) Romantics’ focus on depth, psychological drama, and philosophical profundity. As his career progressed, Poulenc’s radicalism mellowed, but he always kept the mainstream music industry at an arm’s length while also letting mid-century avant-garde serialism pass him by. By 1960, when he wrote the song cycle La courte paille, he was coming off the success of his serious operas Dialogues des Carmélites and La voix humaine

Written for his frequent collaborator soprano Denise Duval, La courte paille is a collection of lighthearted children’s texts set in a modern style, an alternative to the seriousness of Romantic lieder. Characteristic of Poulenc’s style—and indicating the set is meant to be heard as a whole—the progression of songs emphasizes stark contrasts by switching from happy optimism to sorrow, from slow and legato to quick and staccato. Though silly and childlike, the texts of the work are nonetheless modernist: “La carafon” highlights the sound of the language by drawing an absurdist connection between a carafe and giraffe merely because the words rhyme. In his songs, Poulenc tended to follow the structure and prosody of the words to further highlight the sonic qualities of language, such as in “Quelle Aventure !” in which the repeating shouts “Mon Dieu!” leap upward each time. If, by and large, the naïve subject matter of the texts and Poulenc’s, at times, quite joyful music continue to illustrate his youthful aesthetic ideals as a member of Les Six, the final song shows the 61-year-old composer’s maturation by gesturing toward moral philosophy: The slow-building “Lune d’Avril” meditates on childlike dreams of a better future where “all the guns have been destroyed”—ending the irreverent work on a (light) political note in a Cold War context rife with fear of nuclear war.

FRENCH

Le sommeil est en voyage

Mon Dieu! où est-il parti?

J'ai beau bercer mon petit, Il pleure dans son lit-cage, Il pleure depuis midi.

Où le sommeil a-t-il mis

Son sable et ses rêves sages

J'ai beau bercer mon petit, il se tourne tout en nage, Il sanglote dans son lit.

Ah! reviens, reviens, sommeil, Sur ton beau cheval de course!

Dans le ciel noir, la Grande Ourse

A enterré le soleil

Et rallumé ses abeilles.

Si l'enfant ne dort pas bien, Il ne dira pas bonjour, Il ne dira rien demain

A ses doigts, au lait, au pain

Qui l'accueillent dans le jour.

ENGLISH

Sleep has gone off on a journey, Gracious me! Where can it have got to?

I have rocked my little one in vain, He is crying in his cot, He has been crying ever since noon.

Where has sleep put

Its sand and its gentle dreams?

I have rocked my little one in vain, He tosses and turns perspiring, He sobs in his bed.

Ah! Come back, come back, sleep, On your fine race-horse!

In the dark sky, the Great Bear

Has buried the sun

And reawakened his bees.

If baby does not sleep well

He will not say good day, He will have nothing to say

To his fingers, to the milk, to the bread

That greet him in the morning.

FRENCH

Une puce, dans sa voiture, Tirait un petit éléphant

En regardant les devantures

Où scintillaient les diamants.

—Mon Dieu! mon Dieu! quelle aventure!

Qui va me croire, s'il m'entend?

L’éléphanteau, d'un air absent, Suçait un pot de confiture.

Mais la puce n'en avait cure, Elle tirait en souriant.

—Mon Dieu! mon Dieu! que cela dure

Et je vais me croire dément!

Soudain, le long d'une clôture, La puce fondit dans le vent

Et je vis le jeune éléphant

Se sauver en fendant les murs.

—Mon Dieu! mon Dieu! la chose est sûre, Mais comment la dire a maman?

ENGLISH

A flea, in its carriage,

Was pulling a little elephant along Gazing at the shop windows

Where diamonds were sparkling.

—Good gracious! Good gracious! What goings-on!

Who will believe me if I tell them?

The little elephant was absentmindedly

Sucking a pot of jam.

But the flea took no notice,

And went on pulling with a smile.

—Good gracious! Good gracious! If this goes on

I shall really think I am mad!

Suddenly, along by a fence, The flea disappeared in the wind

And I saw the young elephant Make off, breaking through the walls.

—Good gracious! Good gracious! It is perfectly true,

But how shall I tell Mummy?

Mollement accoudée

A ses vitres de lune, La reine vous salue

D'une fleur d'amandier.

C'est la reine de coeur, Elle peut, s'il lui plait, Vous mener en secret

Vers d'étranges demeures.

Où il n'est plus de portes, De salles, ni de tours

Et où les jeunes mortes

Viennent parler d'amour.

La reine vous salue, Hâtez-vous de la suivre

Dans son château de givre

Aux doux vitreaux de lune.

Ba,

FRENCH FRENCH

Ba, be, bi, bo, bu, bé!

Le chat a mis ses bottes, Il va de porte en porte

Jouer, danser, chanter.

Pou, chou, genou, hibou.

“Tu dois apprendre à lire, À compter, à écrire,”

Lui crie-t-on de partout.

Mais rikketikketau,

Le chat de s'esclaffer,

En rentrant au château:

Il est le Chat Botté!

FRENCH

Lune, Belle lune, lune d'Avril, Faites-moi voir en m’endormant

Le pêcher au coeur de safran, Le poisson qui rit du grésil, L'oiseau qui, lointain comme un cor, Doucement réveille les morts

Gently leaning on her elbow

At her moon windows,

The queen waves to you

With a flower of the almond tree.

She is the queen of hearts, She can, if she wishes, Lead you in secret

To strange dwellings.

Where there are no more doors, No rooms nor towers

And where the young who are dead

Come to speak of love.

The queen waves to you, Hasten to follow her

Into her castle of hoar-frost

With the lovely moon windows.

ENGLISH ENGLISH

Ba, be, bi, bo, bu, be!

The cat has put on his boots, He goes from door to door

Playing, dancing, singing.

Pou, chou, genou, hibou.

“You must learn to read,

To count, to write,”

They cry to him on all sides.

But rikketikketau, The cat burst out laughing,

As he goes back to the castle: He is Puss in Boots!

Et surtout, surtout le pays

Où il fait joie, où il fait clair, Où soleilleux de primevères, On a brisé tous les fusils.

Belle lune, lune d'Avril

Lune.

FRENCH

Sur les fils de la pluie, Les anges du jeudi

Jouent longtemps de la harpe.

Et sous leurs doigts, Mozart

Tinte délicieux,

En gouttes de joie bleue.

Car c'est toujours Mozart

Que reprennent sans fin

Les anges musiciens,

Qui, au long du jeudi,

Font chanter sur la harpe

La douceur de la pluie.

FRENCH

“Pourquoi,” se plaignait la carafe, N'aurais-je pas un carafon?

Au zoo, madame la Girafe

N'a-t-elle pas un girafon?”

Un sorcier qui passait par là, A cheval sur un phonographe, Enregistra la belle voix

De soprano de la carafe

Et la fit entendre à Merlin.

“Fort bien,” dit celui-ci, “fort bien!”

Il frappa trois fois dans les mains

Et la dame de la maison

Se demande encore pourquoi

Elle trouva, ce matin-là,

Un joli petit carafon

Blotti tout contre la carafe

Ainsi qu'au zoo, le girafon

Pose son cou fragile et long

Sur le flanc clair de la girafe.

ENGLISH

Moon,

Beautiful moon, April moon, Let me see in my sleep

The peach tree with the saffron heart, The fish who laughs at the sleet, The bird who, distant as a hunting horn, Gently awakens the dead

ENGLISH

On the threads of the rain

The Thursday angels

Play all day upon the harp.

And beneath their fingers, Mozart

Tinkles deliciously

In drops of blue joy.

For it is always Mozart

That is repeated endlessly

By the angel musicians,

Who, all day Thursday,

Sing on their harps

The sweetness of the rain.

ENGLISH

“Why,” complained the carafe, “Should I not have a baby carafe?

At the zoo, Madame the giraffe, Has she not a baby giraffe?”

A sorcerer who happened to be passing by Astride a phonograph, Recorded the lovely soprano voice

Of the carafe

And let Merlin hear it.

“Very good,” said he, “very good.”

He clapped his hands three times

And the lady of the house

Still asks herself why

She found that very morning

A pretty little baby carafe

Nestling closed to the carafe

Just as in the zoo, the baby giraffe

Rest its long fragile neck

Against the pale flank of the giraffe.

And above all, above all, the land

Where there is joy, where there is light, Where sunny with primroses

All the guns have been destroyed. Beautiful moon, April moon, Moon.

Strauss wrote most of his songs during the closing decades of the 19th century, a time during which he was predominantly composing symphonic tone poems with the belief that new ideas demanded new musical forms. As with Liszt, cosmopolitan lieder represented something of the antidote to such large-scale works and such grand ideas. Indeed, for him, lieder had an additional personal meaning, as his wife Pauline de Ahna was a singer, and Strauss’s Op. 27 collection was written in celebration of their marriage. Although completely immersed in the philosophical-musical discourse of his time—his close friend Alexander Ritter constantly pushed him toward Wagner and Liszt’s New German School—Strauss remained somewhat cool toward the Romantic fascination with philosophical depth (he would, after all, become intrigued by Nietzsche’s egocentric nihilism, enough to write the tone poem Also sprach Zarathustra). Indeed, perhaps the most modernist element of Strauss’s style was his interest in finding profundity in the mundane, or pointing out the contradictory ironies of modern life.

In his earliest songs on this evening’s program, Strauss foregrounds strophic form. In “Die Nacht,” the simplicity of the form allows for a slow, dramatic build in emotional intensity as the text describes night stealing the world away in darkness. In “Frülingsgedränge,” the fluttering piano depicts the springtime breeze while modulating through different keys before Strauss breaks the form and ends with impassioned oration as the text turns to direct address. His later songs, all basically throughcomposed, align to his ideal of his symphonic tone poems: Text-inspired musical ideas develop in their own forms. In “Schlagende Herzen,” the onomatopoeia “kling-klang” (which represents a heartbeat) provides a motivic anchor—reminiscent of song refrain—while the spritely music unfolds of its own volition. Ultimately a dramatic monologue in an operatic vein for the vocalist, “Befreit” features musical accompaniment that reveals the underlying internal emotional state of the character attempting to maintain dignity and optimism while saying goodbye to her dying spouse. Finally, in “Muttertändelei,” the music becomes associative, not only depicting specific words—twisting melismas to convey golden curls; harsh dissonance on “bitterböse” (“wicked”)—but also randomly recalling past elements in new contexts as the work progresses.

Aus dem Walde tritt die Nacht, aus den Bäumen schleicht sie leise, schaut sich um in weitem Kreise, nun gib acht!

Alle Lichter dieser Welt, alle Blumen, alle Farben löscht sie aus und stiehlt die Garben weg vom Feld.

Alles nimmt sie, was nur hold; nimmt das Silber weg des Stroms, nimmt vom Kupferdach des Doms weg das Gold.

Ausgeplündert steht der Strauch— rücke näher, Seel’ an Seele, o die Nacht, mir bangt, sie stehle dich mir auch.

Du wirst nicht weinen.

Leise wirst du lächeln und wie zur Reise Geb’ ich dir Blick und Kuβ zurück.

Unsre lieben vier Wände, du hast sie bereitet, Ich habe sie dir zur Welt geweitet;

O Glück!

Dann wirst du heiβ meine Hände fassen Und wirst mir deine Seele lassen, Läβt unsern Kindern mich zurück. Du schenktest mir dein ganzes Leben, Ich will es ihnen wieder geben; O Glück!

Es wird sehr bald sein, wir wissen’s beide, Wir haben einander befreit vom Leide, So gab ich dich der Welt zurück!

Dann wirst du mir nur noch im Traum erscheinen

Und mich segnen und mit mir weinen; O Glück!

Out of the woods steps the night, out of the trees it creeps softly, it looks around in a wide circle, now pay heed!

All of the lights of this world, all of the flowers, the colors it extinguishes, and steals the sheaves from the field.

It takes everything that is lovely; it takes the silver away from the stream, it takes the gold from the copper roof of the cathedral. Plundered stand the bushes— draw nearer, soul to soul, oh the night, I fear, will also steal you from me.

You will not weep. Gently you will smile, and as before a journey, I will return your gaze and your kiss. Our dear four walls you have helped build; and I have now widened them for you into the world.

O joy!

Then you will warmly seize my hands and you will leave me your soul, leaving me behind for our children. You gave me your entire life, so I will give it again to them.

O joy!

It will be very soon, as we both know— but we have freed each other from sorrow. And so I return you to the world! You will then appear to me only in dreams, and bless me and weep with me.

O joy!

Text by Gottfried August Bürger

GERMAN ENGLISH

Seht mir doch mein schönes Kind, Mit den gold’nen Zottellöckchen, Blauen Augen, roten Bäckchen!

Leutchen, habt ihr auch so eins?

Leutchen, nein, ihr habt keins!

Seht mir doch mein süßes Kind, Fetter als ein fettes Schneckchen, Süßer als ein Zuckerweckchen!

Leutchen, habt ihr auch so eins?

Leutchen, nein, ihr habt keins!

Seht mir doch mein holdes Kind, Nicht zu mürrisch, nicht zu wählig! Immer freundlich, immer fröhlich!

Leutchen, habt ihr auch so eins?

Leutchen, nein, ihr habt keins!

Seht mir doch mein frommes Kind!

Keine bitterböse Sieben Würd’ ihr Mütterchen so lieben.

Leutchen, möchtet ihr so eins?

O, ihr kriegt gewiß nicht meins!

Komm’ einmal ein Kaufmann her! Hunderttausend blanke Taler, Alles Gold der Erde zahl’ er!

O, er kriegt gewiß nicht meins!— Kauf’ er sich woanders eins!

Just look at my lovely child with golden curls, blue eyes, red cheeks!

Dear friends, do you have one like this?

Dear friends, no, you do not!

Just look at my sweet child, rounder than a plump little snail, sweeter than a sugar roll!

Dear friends, do you have one like this?

Dear friends, no, you do not!

Just look at my darling child, not too moody, not too choosy!

Always friendly, always happy!

Dear friends, do you have one like this?

Dear friends, no, you do not!

Just look at my innocent child!

No wicked little vixen would love her mother as much.

Dear friends, would you like one like this? Oh, you surely won’t get mine!

Let some merchant come along!

A hundred thousand shiny thalers, all the gold on earth let him pay, Oh, he surely won’t get mine! Let him buy one somewhere else!

Text

by Nikolas LenauGERMAN

Frühlingskinder im bunten Gedränge, Flatternde Blüten, duftende Hauche, Schmachtende, jubelnde Liebesgesänge Stürzen ans Herz mir aus jedem Strauche.

Frühlingskinder mein Herz umschwärmen, Flüstern hinein mit schmeichelnden Worten, Rufen hinein mit trunk’nem Lärmen, Rütteln an längst verschloss’nen Pforten.

Frühlingskinder, mein Herz umringend, Was doch sucht ihr darin so dringend?

Hab' ich's verraten euch jüngst im Traume, Schlummernd unterm Blütenbaume?

Brachten euch Morgenwinde die Sage, Daß ich im Herzen eingeschlossen Euren lieblichen Spielgenossen, Heimlich und selig ihr Bildnis trage?

GERMAN

Über Wiesen und Felder ein Knabe ging,

Kling klang, schlug ihm das Herz;

Es glänzt ihm am Finger von Golde ein Ring.

Kling klang, schlug ihm das Herz;

O Wiesen, o Felder, wie seid ihr schön!

O Berge, o Täler, wie schön!

Wie bist du gut, wie bist du schön, Du gold’ne Sonne in Himmelshöhn!

Kling klang, kling klang, kling klang, schlug ihm das Herz.

Schnell eilte der Knabe mit fröhlichem Schritt, Kling klang, schlug ihm das Herz; Nahm manche lachende Blume mit—

Kling klang, schlug ihm das Herz.

Über Wiesen und Felder weht Frühlingswind,

Über Berge und Wälder weht Frühlingswind, Im Herzen mir innen weht Frühlingswind, Der treibt zu dir mich leise, lind,

Kling klang, schlug ihm das Herz.

Zwischen Wiesen und Feldern ein Mädel stand, Kling klang, schlug ihr das Herz.

Hielt über die Augen zum Schauen die Hand,

Kling klang, schlug ihr das Herz.

Über Wiesen und Felder, über Berge und Wälder,

Zu mir, zu mir, schnell kommt er her, O wenn er bei mir nur, bei mir schon wär!

Kling klang, kling klang, kling klang, schlug ihr das Herz.

ENGLISH

Over meadows and fields went a boy, pit-a-pat beat his heart; on his finger shines a ring of gold, pit-a-pat beat his heart!

O meadows, o fields, how fair you are!

O hills, o valleys, how fair!

How good, how lovely you are, you golden sun in heaven’s heights! Pit-a-pat beat his heart.

Swiftly hurried the lad with joyous step, pit-a-pat beat his heart; taking with him many a smiling flower— pit-a-pat beat his heart.

Over meadows and fields the spring wind blows, over hills and woods the spring wind blows, deep within my heart the spring wind blows, driving me softly, gently to you, pit-a-pat beat his heart.

Between meadows and fields stood a girl, pit-a-pat beat her heart.

Shading her eyes with her hand to gaze, pit-a-pat beat her heart.

Over meadows and fields, over hills and woods, to me, he is hastening here to me. Oh, if he were only with me, were already here!

Pit-a-pat beat her heart.

ENGLISH

Spring’s children in colorful abundance, Fluttering blooms, fragrant breezes, Languishing, triumphant love songs Rush to my heart from every bush.

Spring’s children swarm around my heart, Whisper to it with flattering words, Call to it with intoxicated noise, Rattle at long-closed gates.

Spring’s children, surrounding my heart, What are you looking for so insistently? Have I revealed it to you in my dreams, As I was sleeping under the blooming tree?

Did the morning breezes tell you That, locked in my heart, I secretly and lovingly carry the portrait Of your lovely playmate?

An iconoclast from a young age, Prokofiev engaged the lieder tradition as a way to reject much of the Russian nationalism of the “Mighty Handful” (with their interest in folk songs) by adopting the older, Germanic through-composed ideals of Schubert. Recognized for his talent at an early age, Prokofiev began studying piano at age four; attended his first operas at age nine, becoming familiar with works by Gounod, Borodin, Tchaikovsky, Verdi, and Bizet; and even wrote his first opera at age 10. He entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory around age 13, a child among adults. Although he admired his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov at conservatory, Prokofiev nonetheless rejected outright most of his teachings—notably the importance of using closely-related keys and overall emphasis on organic unity. Moreover, he completely avoided the larger nationalist school of the conservatory. In the recently published Rethinking Prokofiev, Marina Raku, Rita McAllister, and Gabrielle Cornish state: “Looking back at this decisive period in the formation of Prokofiev’s musical persona, it is of interest to note just how unimportant is the part the ‘Russian tradition’ played in its makeup and how insignificant was the influence of his immediate teachers.” What Prokofiev took away from his time in St. Petersburg was the attitude of aesthetic progressivism and experimentalism found broadly across the arts during the city’s so-called Silver Age. The work in which these ideals came into fruition was his 12-minute art song—one of his earliest mature works—based on the Hans Christian Andersen story “The Ugly Duckling.” Speaking of the work, he wrote: “It may represent the birth of a new style in my compositions, but it is one that has been maturing for more than a year now.”

While it is often dubious to interpret artworks autobiographically, “The Ugly Duckling” nonetheless has striking parallels to Prokofiev’s life and character that suggest the work represents his personal identity (at least as he understood himself in 1914). The narrative tells of an ugly “duckling” who is alienated and jeered by his peers and then goes through a difficult winter before transforming into a beautiful swan and finding his place in the world. Musically, the vocal line sustains a declamatory style—following the prosody and inflection of the language in a heightened, but still natural, manner—while slyly moving around chromatically from one key to the next. (Such chromatic motion was antithetical to Prokofiev’s conservatory instruction and was something he admired in the German composer Max Reger and the Moscow-based Alexander Scriabin.) While the vocal line remains, for the most part, stylistically unified, the piano accompaniment is a veritable box of chocolates. Styles come and go with practically every two lines of text, usually illustrating some semantic concept (e.g., staccato piano for hatching from shells; a dramatic modulation to major for the arrival of spring). Yet writ large, the work starts with fast-moving music; switches to an arduous, slow, and highly chromatic middle section as the duckling weathers the winter; and returns to a brisk finale. Prokofiev, the alienated child prodigy, had to go through his own journey to find his voice, and the swan that emerged was The Ugly Duckling

Kak khorosho bylo v derevne!

Solnce veselo sijalo, rozh' zolotilas', Dushistoje seno lezhalo v stogakh.

V zelenom ugolke, sredi lopukhov,

Utka sidela na jajcakh.

Jej bylo skuchno, ona utomilas' ot dolgogo sidenija.

Nakonec, zatreshchali skorlupki odna za drugoj.

Utjata vylezli na svet.

Kak velik bozhij mir! Kak velik bozhij mir!

Poslednij utjonok byl ochen' nekrasiv, Bez per'ev, na dlinnykh nogakh.

Uzh ne indjushonok li?!—

Ispugalas' sosedka-utka.

Poshjol utinyj vyvodok na ptichij dvor. Derzhites', deti, prjamo, lapki vroz'.

Poklonites' nizko toj staroj utke, Ona ispanskoj porody.

Vidite u nej na lape krasnuju tesemku?

`Eto vysshij znak otlichija dlja utki!

Utjata nizko klanjalis' ispanskoj utke

I skoro osvoilis' so vsem naselenijem

Ptich'ego dvora. Plokho prishlos' Tol'ko bednomu nekrasivomu utjonku.

Nad nim vse smejalis', gnali jego otovsjudu, Zhelali, chtoby koshka s"ela skoreje jego.

Kury klevali jego, utki shchipali, Ljudi tolkali nogoj, a indejskij petukh, Naduvshis', kak korabl' na parusakh, Naskochil na neschastnogo utjonka!

Utjonok sobral vse svoi sily i pereletel cherez zabor.

Ptichki, sidevshije v kustakh, vsporkhnuli s ispugu.

Utjonok podumal: `Eto ottogo, chto ja takoj gadkij ...

On zakryl glaza, no vse zhe prodolzhal bezhat', Poka ne dostig bolota. Tam dikije utki

Nakinulis' na nego: Ty chto za ptica?!

Utjonok povorachivalsja na vse storony. Ty uzhasno gadok!

Utjonok klanjalsja kak tol'ko mog nizhe. Ne vzdumaj zhenit'sja na kom-nibud' iz nas!

Mog li podumat' ob `etom utjonok!

Tak nachalis' jego stranstvovanija.

It was beautiful in the country!

The golden wheat rolled in waves. The grass was green, the hay was put to the millstone, the sun shone.

In the shade of the reeds, alone at the bottom of the garden, a duck sat on her nest. She was sad and very tired of sitting.

All of a sudden the eggshells gaily burst one by one.

All the little ones saw the day. "What a grand world!"

Of all the brood, one alone was ugly, without feathers, his feet too long.

"What a horror, a true turkey!" cried all the gossiping ducks.

All the little ones reached the farmyard. "Children, hold your feet well apart. Say hello to the old duck. She is Spanish!

Do you see that red scarf around her foot?

It is a distinction very rare among the ducks."

The little ones bowed before her. Soon they knew all the customs of the farmyard.

Sad and all alone lived the featherless ugly duckling.

His fate was terrible. He knew nothing but hatred.

Everyone wished him to be eaten by the cat. He was pecked at by the rooster and by the guinea-fowl. They found him much too ugly.

The turkey, turning red, clucking and inflating himself like a sail, attacked the little weak and trembling one.

Then the duckling, by flapping his wings, got over the wall of the yard and flew away. Birds quickly flew away when he approached. The poor little one thought, "It's because I am ugly that they fly away when I arrive."

He closed his eyes and painfully made his way to a deep pond.

There, to his surprise, he saw wild ducks. "What is this monster?"

The poor little duck hung his head, all a-tremble.

Chego tol'ko ne vyterpel on za `etu strashnuju osen'!

Inogda on chasami sidel v kamyshakh, Zamiraja ot strakha, drozha ot ispuga, A vystrely okhotnikhov razdavalis' po vsemu lesu.

Strashnaja past' sobaki zijala nad jego golovoj.

Stanovilos' kholodnej. Ozero postepenno zatjagivalos' l'dom.

Utjonok dolzhen byl vse vremja plavat', chtob voda ne zamerzla.

Bylo b slishkom grustno rasskazyvat'

O tekh lishen'jakh, kakije vynes on v `etu zimu!

Odnazhdy solnyshko prigrelo zemlju svoimi teplymi luchami, Zhavoronki zapeli, kusty zacveli - prishla vesna.

Veselo vzmakhnul utjonok kryl'jami. Za zimu oni uspeli vyrasti.

Podnjalsja na kryl'jakh utjonok

I priletel v bol'shoj cvetushchij sad.

Tam bylo tak khorosho!

Vdrug iz chashchi trostnikov pojavilis' Tri prekrasnykh lebedja.

Neponjatnaja sila privlekala utjonka k `etim carstvennym pticam.

Jesli on priblizitsja k nim, oni, konechno, jego ub'jut,

Potomu chto on takoj gadkij...

No luchshe umeret' ot ikh udarov, Chem terpet' vse, chto vystradal on v prodolzhenije `etoj zimy!

Ubejte menja... skazal utjonok

I opustil golovu, ozhidaja smerti.

No chto on uvidel v chistoj vode? Svoje otrazhen'e!

No on byl teper' ne gadkoj seroj pticej, A prekrasnym lebedem.

Ne beda v gnezde utinom rodit'sja, Bylo b jajco lebedinoje!

Solnce laskalo jego, siren' sklonjalas' pred nim,

Lebedi nezhno jego celovali!

Mog li on mechtat' o takom schast'e, Kogda byl gadkim utjonkom?

"You are very grotesque!"

The poor one made deep bows.

"Don't you dream of marrying one of us!"

Oh, he was far from dreaming of marriage.

It was the beginning of his sad adventures.

During the autumn months he endured nothing but harm and suffering.

He spent the days trembling in the reeds, ravaged by anguish, dying of terror, while hunters shot without stopping, close to the gloomy lake.

Then an enormous dog hurled himself at the duck, wanting to eat him.

The weather became much colder. Little by little the ice covered the waters of the lake.

The duckling had to swim constantly to keep a corner open.

And he experienced other sufferings, other miseries, during the terrible icy winter.

The clear sun finally regained its strength; nature was revived.

The birds sang and the air was clear. Oh, beautiful springtime!

The duck happily beat his wings, which felt bigger and stronger.

He flew into space and landed in a flowering garden.

The park was beautiful!

Suddenly, gliding over the water appeared three swans, beautiful and graceful. A strong force attracted him against his will to the proud and noble birds.

Yet if he approached them certainly he would be killed, because wasn't he truly a monster?

Better to be killed by these beautiful swans, than to endure again the misfortunes he suffered through the winter.

"All right, kill me!" he said quietly, and resignedly lowered his head waiting for death.

In the dazzling clear water, he saw his reflection. What joy!

He was no longer a bird without feathers, but a swan, beautiful and proud.

It is possible to be born in the nest of a duck as long as the egg is that of a swan!

In the rays of the sun the waters of the lake rocked him, and tenderly the beautiful swans embraced him. Could he ever have had such a beautiful dream when he was a bird without feathers?!

Then Schubert changed everything. His innovation was to elevate the simplicity of the genre by letting music imbue the text with greater emotional depth and drama. In Schubert’s works, the music functioned at once as part of the work—it is not a song without music, even Goethe, who called his poetry “lieder,” said so—but no longer subservient to the text, the music transcended its own medium to offer commentary on the words.

One way Schubert accomplished this was to adopt the Romantic ideal of program music (that is, music that conveys a story or “extra-musical” ideas) and writing through-composed works, like “Vergebliche liebe.” In this lied, each stanza has a distinct musical style: first speech-like declamation, second a characteristically Schubertian motto perpetuo accompaniment, and last a rustic um-pa-pa. On the opposite end of the spectrum, however, Schubert maintained the simplicity of the traditional strophic structure in “Du bist die Ruh” and “Liebe schwärmt auf allen Wegen” from Claudine von Villa Bella. Notably, the latter—technically an arietta from a Singspiel (a form of German musical theater)—is perhaps the most songlike of the works on this evening’s program, in part because in theatrical music,the character sings a song that must be distinguished from other singing. Yet, many of Schubert’s works fall in between through-composed and strophic. “Lied der Delphine” hints at strophic song form with the vocal melody, while using another motto perpetuo accompaniment (conveying the obsessive appetite of desire) as the foundation for a wandering musical narrative. Whether strophic or through-composed, Schubert also used modal mixture—borrowing harmonies of the relative minor key in the context of a major key—to connote shifting moods of the text. In his late work “Heimliches lieben,” the swift modulations through many distant keys is particularly remarkable for this effect.

by J. W. von Goethe

GERMAN

Liebe schwärmt auf allen Wegen;

Treue wohnt für sich allein.

Liebe kommt euch rasch entgegen;

Aufgesucht will Treue sein.

Liebe schwärmt auf allen Wegen;

Treue wohnt für sich allein.

Liebe schwärmt auf allen Wegen

Aufgesucht will Treue sein

Aufgesucht will Treue sein

Love roves everywhere; constancy lives alone.

Love comes rushing towards you; constancy must be sought.

Love roves everywhere; constancy lives alone.

Love comes rushing towards you; constancy must be sought constancy must be sought

GERMAN

O du, wenn deine Lippen mich berühren, Dann will die Lust die Seele mir entführen. Ich fühle tief ein namenloses Beben Den Busen heben.

Mein Auge flammt, Gluth schwebt auf meinen Wangen, Es schlägt mein Herz ein unbekannt Verlangen;

Mein Geist verirrt in trunkner Lippen Stammeln

Kann kaum sich sammeln.

Mein Leben hängt in einer solchen Stunde

An deinem süßen, roseweichen Munde, Und will, bei deinem trauten Armumfassen, Mich fast verlassen.

O! daß es doch nicht außer sich kann fliehen, Die Seele ganz in deiner Seele glühen!

Daß doch die Lippen, die vor Sehnsucht brennen, Sich müssen trennen!

Daß doch im Kuß’ mein Wesen nicht zerfließet,

Wenn es so fest an deinen Mund sich schließet,

Und an dein Herz, das niemals laut darf wagen für mich zu schlagen!

ENGLISH

When your lips touch me, desire would bear my soul away; I feel a nameless trembling which swells my breast. My eyes flame, a glow colors my cheeks; my heart beats with an unknown longing;

my mind, lost in the stammering of my drunken lips can hardly compose itself. In such a moment my life hangs on your sweet lips, soft as roses, and, in your dear embrace, life nearly deserts me.

Oh would that my life could escape from itself, my soul aflame in yours!

Oh that lips burning with longing, must part!

Oh that my being might not dissolve in kisses

when my lips are pressed so tightly to yours, and to your heart, which might never dare to beat aloud for me!

Text

by Friedrich RückertGERMAN

Du bist die Ruh, Der Friede mild, Die Sehnsucht du, Und was sie stillt.

Ich weihe dir

Voll Lust und Schmerz

Zur Wohnung hier

Mein Aug’ und Herz.

Kehr’ ein bei mir

Und schließe du

Still hinter dir

Die Pforte zu.

Treib’ andern Schmerz

Aus dieser Brust!

Voll sei dies Herz Von deiner Lust.

Dies Augenzelt, Von deinem Glanz Allein erhellt, O füll’ es ganz!

ENGLISH

You are rest, the gentle peace, you are longing and what stills it.

To you I dedicate, full of pleasure and pain, as a dwelling here, my eyes and heart. Come, enter in and close quietly behind you the gates.

Drive other pain from this breast!

May my heart be full with your pleasure.

The temple of my eyes is illumined only by your radiance, oh fill it completely!

Ja, ich weiß es, diese treue Liebe Hegt umsonst mein wundes Herz!

Wenn mir nur die kleinste Hoffnung bliebe, Reich belohnet wär' mein Schmerz!

Aber auch die Hoffnung ist vergebens, Kenn' ich doch ihr grausam Spiel!

Trotz der Treue meines Strebens Fliehet ewig mich das Ziel!

Dennoch lieb' ich, dennoch hoff' ich, immer Ohne Liebe, ohne Hoffnung treu; Lassen kann ich diese Liebe nimmer! Mit ihr bricht das Herz entzwei!

Text by Christian Wilhelm von Schütz

GERMAN

Ach, was soll ich beginnen vor Liebe?

Ach, wie sie innig durchdringet mein Inn’res!

Siehe, Jüngling das Kleinste vom Scheitel

Bis zur Sohl’ ist dir einzig geweihet.

Ist dir einzig, einzig dir geweihet.

O Blumen, Blumen! Verwelket, Euch pfleget nur, bis sie Lieb’ erkennet, die Seele Nichts will ich thun, wissen und haben,

Gedanken der Liebe, Die mächtig mich fassen, Gedanken der Liebe nur tragen.

ENGLISH

Yes, I know that my wounded heart

Contains this true and unrequited love!

If I still had the smallest glimmer of hope, My pain would gladly be rewarded!

But, alas, all hope is in vain,

How well I know her cruel game!

In spite of the loyalty of my longing

The goal always eludes me!

Yet I still love, yet I always keep hope

Without Love, without hope I can never forget this love! With it, my heart is broken!

Immer sinn’ ich, was ich aus Inbrunst wohl könne thun,

Doch zu sehr hält mich Liebe in Druck, Nichts, nichts, nichts lässt sie zu.

Jetzt, da ich liebe, möcht’ ich erst leben, und sterbe. Jetzt, da ich liebe, möcht’ ich hell brennen, und welke.

Wozu ach Blumen reihen und wässern? Entblättert!

So sieht, wie Liebe mich entkräftet, Sein Spähen.

Der Rose Wange will bleichen, auch meine, ihr Schmuck, Zerfällt, wie verscheinen die Kleider.

Ach, Jüngling da du mich erfreuest mit Treue, Wie kann mich mit Schmerz so bestreuen die Freude?

Ach, was soll ich beginnen, Ach was vor Liebe, vor Liebe?

What shall I do, I am so much in love?

How it pervades my whole being!

See, dear youth, the smallest thing from my head to my toes is dedicated only to you.

O flowers! wither away, for you were only tended until my soul knew love.

I want to do nothing, know nothing, have nothing; The thoughts of love which hold me so fast are all I need.

I sense always what I could do out of fervor, yet nothing will make love let go.

Only now that I love, I begin to wish to live, and also die.

Now that I love, I wish to burn brightly, and I fade.

Why plant flowers and water them?

His glance sees how love has weakened me, leafless and withered

The rose’s cheek will pale as will mine, its adornment decays as my garments fade.

Ah, dear youth, since you gladden me with your faithfulness,

how can joy give me so much pain?

What shall I do, I am so much in love?

American soprano Brenda Rae’s current European engagements include her Amina in La sonnambula at the Wiener Staatsoper and Maïma in Barkouf at Opernhaus Zürich, which she will reprise in December. She returns to the Bayerische Staatsoper as Konstanze in Die Entführung aus dem Serail under Ivor Bolton, and then brings her acclaimed Zerbinetta in Ariadne auf Naxos to Hong Kong, on tour with Bayerische Staatsoper. In recital, Brenda will appear at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Future engagements include returns to the Metropolitan Opera, the Opernhaus Zürich and a debut at the Deutsche Oper Berlin.

The 22/23 season featured her return to Bayerische Staatsoper as the title role in Claus Guth’s new production of Semele and her return to Opernhaus Zürich as Maïma in Max Hopp’s new production of Offenbach’s Barkouf. She brought her “mesmerizing stage presence and crystal-clear voice” (New York Classical Review) to Paris, appearing at Opéra Bastille as Ophélie in Thomas’s Hamlet and as the title role in Lucia di Lammermoor. Brenda also returned to the Wiener Staatsoper stage in one of her signature roles, Queen of the Night in Die Zauberflöte, and as Norina in Don Pasquale. She bookended her season with two one-night-only engagements: A Tribute to Edita Gruberová at Bratislava’s Slovak National Theatre and a chamber recital at the Munich Opera Festival.

Honored by the Metropolitan Opera with the 2021 Beverly Sills Artist Award, Brenda has appeared at the Met as Ophelia in the company premiere of Brett Dean’s Hamlet, Poppea in a new David McVicar production of Agrippina, and as Zerbinetta (Ariadne auf Naxos), with all three productions simulcast live in cinemas around the world. She made her much-anticipated Royal Opera House debut as Queen of the Night, and her debut at Teatro Real Madrid as Adina (L’elisir d’amore) was followed by immediate re-engagements as Donna Anna (Don Giovanni) and the title role in Christopher Alden’s Man Ray–inspired production of Partenope.

As a former member of the ensemble of Oper Frankfurt, Brenda amassed an impressive repertoire including Violetta (La traviata), Lucia, Konstanze (Die Entführung aus dem Serail), Amina (La Sonnambula), Olympia (Les contes d’Hoffmann), Zdenka (Arabella), and Gilda (Rigoletto). Zerbinetta (Ariadne auf Naxos) has become one of her most celebrated roles, leading to house debuts at the Staatsoper in Berlin and Hamburg as well as further performances at Bayerische Staatsoper and Edinburgh International Festival.

She has appeared at Wiener Staatsoper as Konstanze (Die Entführung aus dem Serail), Opernhaus Zürich as Comtesse Adèle (Le comte Ory), English National Opera as Berg’s Lulu in the William Kentridge production, Opéra national de Paris as Anne Trulove (The Rake’s Progress), Seattle Opera as Semele, and the 2011 Glyndebourne Festival as Armida (Rinaldo), which was

part of the BBC Proms and released on DVD by Opus Arte. Further roles include Elvira (I puritani) at Oper Frankfurt, and her first Amenaide (Tancredi) at Opera Philadelphia.

On the concert platform, Brenda joined the orchestra of Teatro alla Scala on two occasions singing Mozart, most recently under Zubin Mehta. In recital, she is a regular guest of the celebrated Schubertiade in Schwarzenberg and Wigmore Hall in London.

French pianist and vocal coach Bénédicte Jourdois is a member of the Metropolitan Opera music staff and teaches and coaches at The Juilliard School and the Met’s Lindemann Young Artist Development Program. With Steven Blier, she co-directs the Schwab Vocal Rising Stars program at Caramoor.

Bénédicte has performed in numerous venues in Europe and in the United States, including Alice Tully Hall and Carnegie Hall in New York, and the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC. As a coach and pianist, she has worked with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, LA Opera, Ryan Opera Center (Lyric Opera of Chicago), Chicago Opera Theater, Pittsburgh Opera, Washington National Opera, Washington Concert Opera, Houston Grand Opera, Opera Philadelphia, Palm Beach Opera, Opera Saratoga, Rice University, Chautauqua Institution voice program, Castleton Festival, Spoleto Festival USA, and Carnegie Hall’s SongStudio. She was previously a faculty member at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia and at the Manhattan School of Music.

Born in Paris, Bénédicte holds degrees from the Conservatoire National de Région de Saint-Maur, the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Lyon, Mannes College, and The Juilliard School, and is a graduate of the Lindemann Young Artist Development Program at The Metropolitan Opera.

Association of Performing Arts Professionals

Mohamed F. Bacchus

M Jacob J. Baggott & Jennine E. Baggott

John A. Barnhardt

Gretchen E. Baudenbacher

Robert M. Bell & Jeanne L. Bell

Miriam S. Boegel & Brian M. Boegel

Christine W. Bohlman & Professor Philip V. Bohlman

Richard J. Bonomo & Marla H. Bonomo

Michelle A. Brayer Gregoire & Tim Gregoire

Brittingham Trust

Michael T. Brody & Elizabeth K. Ester

Marion F. Brown

Glenna M. Carter & Reeves E. Smith

Peggy H. Chane

Peter C. Christianson

Matthew S. Clark & Kelly A. Clark

Professor Charles L. Cohen & Christine A. Schindler

Sam Coe

Howard M. Collens & Nancy Collens

David R. Cross

George C. Cutlip

Dane Arts

Heather M. Daniels

Joseph P. Davis III & Wendy T. Davis

André R. De Shields

Kelly G. DeHaven & David T. Cooper

Sean P. DeKok

Darren M. DeMatoff

Lori A. DeMeuse

Mark A. Dettmann

Dr. Leslie D. Dinauer & Stephen R. Dinauer

Jaimie L. Dockray & Brian B. Dockray

Bess Donoghue

Elizabeth G. Douma

Dr. Irene Elkin

Rae L. Erdahl

John R. Evans

Evjue Foundation

Jon E. Fadness

Carol H. Falk & Alan F. Johnson

Hildy B. Feen

Isabel K. Finn

Jill A. Fischer

Janice R. Fountain

Carol A. Fritsche & Jeffrey P. Fritsche

Marisa J. Gandler & Mark J. Gandler

Dr. Linda I. Garrity Living Legends Endowment Fund

Tara L. Genske & Mark A. Dostalek

Leonard H. Gicas

Garry M. Golden & Ann L. Gregg

Clarke C. Greene & Elizabeth A. Greene

Mary Greer Kramer

Kiley A. Groose

Amy Guthier & Mark C. Guthier

Jennifer C. Hartwig

Dr. Marlene T. Hartzman

Brent T. Helt

Michael E. Hosig

Arnold R. Isaacs & Kathleen T. Isaacs

Stephen T. Jacobson

Dr. Arnold F. Jacobson

Brian M. Jenks

Bill and Char Johnson Classical Music Series Fund

Kristen E. Kadner & Brian J. Roddy

Kelly R. Kahl & Kimberly S. Kahl

Michael J. Kane & Jennifer L. Kane

William E. Kasdorf & Cheryl E. Kasdorf

Evelyn L. Keaton

Daniel J. Koehn & Mark R. Koehn

Andrew M. Kohrs

Thomas J. Konditi

Diane M. Kostecke & Nancy A. Ciezki

Amy L. Lambright Murphy & Paul J. Murphy

Matthew A. Lamke

Charles Leadholm

Caryn E. Lesser & Max Lesser

Carolyn P. Liebhauser & Kevin C. Liebhauser

Professor Douglas P. Mackaman & Margaret L. O'Hara

Madison Arts Commission

Roberta L. Markovina & Matthew P. Markovina

Anita L. Mauro & Daniel Mauro

Mead Witter School of Music

Professor Emeritus Charles F. Merbs & Barbara P. Merbs

Stephen Morton

National Endowment for the Arts

William K. Niemeyer & Allison Duncan

Victoria K. Palmer-Erbs

Stephen E. Parker & Jill A. Parker

Ann K. Pehle

Dr. Kato L. Perlman

Lisa A. Pfaff

Kathleen P. Pulvino & Dr. Todd C. Pulvino

Reinhart Boerner Van Deuren SC

Dr. Mark J. Reischel MD & Angela Reischel

Jeremy V. Richards & Joyce D. Richards

Ellen S. Roeder

Dr. Michelle L. Rogers

Ian M. Rosenberg & Caroline Laskow

Kristi A. Ross-Clausen

Sharon S. Rouse

Erik C. Rudeen

Dr. Douglas K. Rush

Ralph F. Russo & Lauren G. Cnare

Peter J. Ryan

Dr. Vinod K. Sahney & J Gail Meyst

Sahney

Emil R. Sanchez & Eloisa R. Sanchez

Ruth Shneider Brown

Margaret A. Shukur

Thomas R. Smith

Elizabeth Snodgrass

Polly Snodgrass

Kristina Stadler

Frank Staszak

Lynn M. Stathas

Jason L. Stephens & Dr. Ana C. Stephens

Dr. Andrew W. Stevens

Ann M. Sticha

Thompson Investment Management

Daniel J. Van Note

Teresa H. Venker

Douglas and Elisabeth B. Weaver Fund for Performing Arts

Wisconsin Alumni Association

Wisconsin Arts Board

Janell M. Wise

James H. Wockenfuss & Lena M. Wockenfuss

Gregory M. Zerkle & Cynthia A. Marty

Thursday, March 14 | 7:30 PM

Play Circle at Memorial Union Jazz

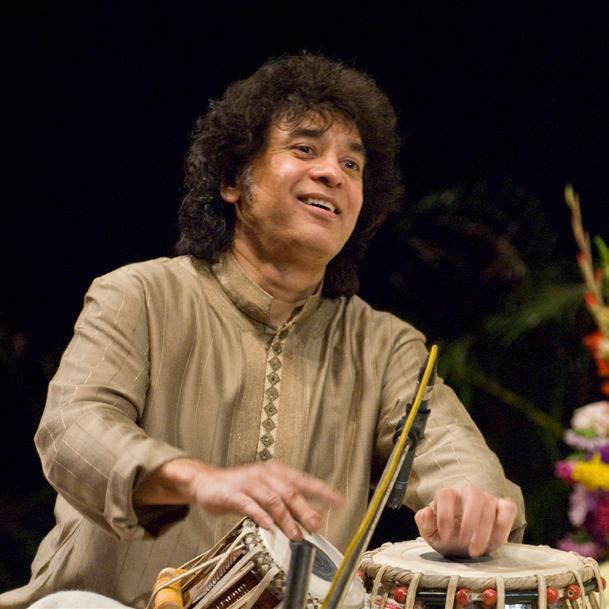

3X 2024 GRAMMY Winner! TISRA: ZAKIR HUSSAIN WITH DEBOPRIYA CHATTERJEE AND SABIR KHAN

Saturday, March 16 | 7:30 PM

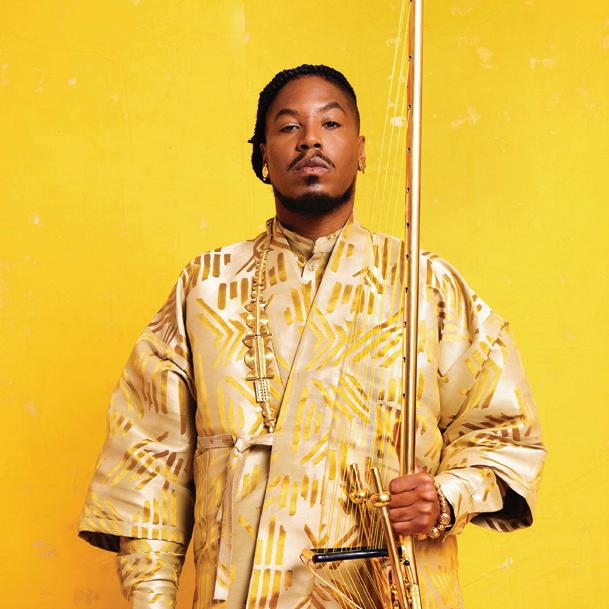

Shannon Hall at Memorial Union International

CHIEF ADJUAH (FORMERLY CHRISTIAN SCOTT)

Thursday, May 2 | 7:30 PM

Shannon Hall at Memorial Union Jazz

With two performance spaces in Memorial Union, Shannon Hall and Play Circle, the Wisconsin Union Theater and the Wisconsin Union Directorate (WUD) Performing Arts Committee presents an annual season of performing arts events including the Classical Series, Jazz Series, and events including dance, music, and more. Additionally, hundreds of free concerts are presented annually in spaces at Memorial Union and Union South, all planned by students.

Wheelhouse Studios, located on the lower level of Memorial Union, is a vibrant art-making space. Three versatile studios provide open studio spaces, art classes, group events, and a variety of free art-making events.

Explore two art galleries in Memorial Union with year-round free exhibitions presented by the Wisconsin Union’s student-led WUD Art Committee, and head to Union South to see a third gallery space. You can also view some of the nearly 1500 works that make up the Wisconsin Union Art Collection in hallways, offices, and meeting rooms in both Memorial Union and Union South.

The 330-seat Marquee Cinema and the Memorial Union Terrace are the setting for hundreds of film screenings every year, the majority of which are programmed by the WUD Film Committee.

UW–Madison students plan and promote the Wisconsin Union’s art exhibitions as well as most of the Union’s more than 1,000 events throughout the year, including live music and performing arts events. Committees and clubs include Performing Arts, Film, Music, Art, Publications, and the Wisconsin Singers.

Elizabeth Snodgrass, Director

Kate Schwartz, Artist Services Manager

George Hommowun, Director of Theater Event Operations

Zane Enloe, Production Manager

Jeff Macheel, Technical Director

Heather Macheel, Technical Director

Chloe Tatro, Lead House Manager

Christina Majchrzak, Director of Ticketing

Sean Danner, Box Office Manager

Will Griffin, Ticketing and Web Systems Administrator

Ryan Flannery, Bolz Center Administrative Intern

Azura Tyabji, Director

Diya Abbas, General Programming Associate Director

Heavyn Dyer-Jones, General Programming Associate Director

Savanna Lee, Marketing Associate Director

Nazeeha Rahman, External Relations Associate Director

Wisconsin Union Theater

800 Langdon St., Madison, WI 53706

608-262-2202 (Main Office)

608-265-ARTS (Box Office)

uniontheater.wisc.edu