THE MUDD CENTER FOR ETHICS ANNUAL REPORT ’24

Ethics of Design

Washington and Lee University

Lexington, Virginia

Washington and Lee University

Lexington, Virginia

In 2023-24, the Mudd Center for Ethics explored the Ethics of Design. To design is to create, fashion, execute or construct something according to a plan. Designers craft products, systems, programs, policies, technologies, strategies and experiences. They analyze problems from a holistic perspective and use ingenuity and design methodologies to address them. Design processes can use art and science to express a particular vision and optimize certain outcomes.

Effective design can be invisible to us even as it shapes our lives in powerful ways. The Ethics of Design program explored how design thinking might address modern ethical dilemmas that we collectively face. How should design solutions be informed or constrained by their potential social or environmental costs? What methodologies can designers use to assess and shape the ethical contexts of their work?

Our series began with a lecture by Danielle Wood, an aerospace engineer whose research uses space technology to address issues of justice and sustainability on Earth and in space. Next, the designer George Aye described methods used in his Greater Good Studio to ensure that their work promotes social equity and avoids the unintentional perpetuation of social harms. The bioethicist Jennifer Blumenthal-Barby discussed how health care providers might use choice architecture to nudge patients toward medical decisions that are in their best interest and in accordance with their values and goals.

The artist, design researcher and writer Sara Hendren encouraged us to think in normative terms about the physical world we inhabit: to sharpen our perceptions of how it’s typically built, to envision how it should be and to contemplate how design thinking can help to bridge that gap. The architect Elgin Cleckley described his _mpathic design methodology that raises untold narratives and unheard voices within public spaces. Finally, the urban space artist Candy Chang described participatory art installations that allow us to connect with our shared humanity in public spaces.

All of the events in the Ethics of Design program emphasized normative as well as methodological thinking – how should things be, and through what practices could one make that happen? Workshops provided opportunities for students, staff and faculty to explore methods for conducting values-driven work and collaboration. The Before I Die wall, located in W&L’s intellectual heart – Leyburn Library – prompted community members to contemplate and share aspirations on an existential scale. The Human Library® provided a welcomed framework for us to challenge stereotypes and prejudices through dialogue.

A highlight of this year was the Mudd Center’s Ethical Reasoning in Action (ERiA) Faculty Learning Community. Sixteen faculty members from all corners of the university learned a flexible approach for teaching ethical reasoning and developed topical lesson plans in a year-long, eight-session workshop. I’m optimistic that this initiative has helped to seed the integration of ethics-related content across our curriculum.

I sign off as Mudd Center director with deep gratitude for the wisdom and camaraderie of Mudd Center team members, for the instrumental role of W&L collaborators in actualizing the center’s mission and for the inspirational ideas that Mudd Center contributors have shared with our community. Roger Mudd’s legacy is thriving, and it has been an honor to be part of it.

Karla Klein Murdock, Director

A record number of faculty and staff signed up to participate in the Mudd Center Fellows Program this year. In response to feedback on our 2023 Fellows Program assessment survey, we increased the variety of participation options to suit participants’ varying schedules and interests. Highlights of the 2023-24 Fellows Program included reading books by Sara Hendren (“What Can a Body Do? How We Meet the Built World”) and Elgin Cleckley (“Empathic Design: Perspectives on Creating Inclusive Spaces”), enjoying lively luncheon discussions with designer George Aye and bioethicist Jennifer Blumenthal-Barby and discussing Cleckley’s work over dinner with public historian Lynn Rainville.

Jumana Al-Ahmad: visiting assistant professor of Arabic

Emma Brobeck: visiting assistant professor of classics

James Broda: assistant professor of mathematics

Ronda Bryant: associate dean of students

Terri Byrnes: administrative assistant, law

Ruth Candler: associate director of Lifelong Learning

Sarah Cravens: visiting professor of law

Katherine Dau: senior associate director of Annual Giving

Jon Eastwood: professor of sociology

Kyle Friend: associate professor of chemistry and biochemistry

Jacob Gibson: visiting assistant professor of cognitive and behavioral science

Keri Gould: externship program director and professor of practice, law

Andrea Hilton: associate director of professional development

Li Kang: assistant professor of philosophy

Chawne Kimber: dean of the college, professor of mathematics

Gary Kirk: director of Lifelong Learning

Julie Knudson: director of academic technologies

Matthew Lamb: visiting assistant director of philosophy

Emily Landry: visiting assistant professor of business administration

Fred LaRiviere: associate dean of the college, associate professor of chemistry

Robin LeBlanc: professor of politics

Mengying Liu: assistant professor of engineering

Jayson Margalus: Johnson Professor of Entrepreneurship and Leadership and director of the Connolly Center for Entrepreneurship

Barton A. Myers: professor of history

Brooklyn Parr: dining services

Howard Pickett: director of the Shepherd Program and associate professor of poverty and human capability studies

Emily Pogue: director of Annual Fund leadership gifts

Amanda Price: assistant director of admissions

Wendy Rains: office manager, University Library

Jake Reeves: assistant director of inclusion and engagement

Stephanie Sandberg: assistant professor of theater

Heather Scherschel: associate director of career and professional development

Elizabeth Spear: curator of academic engagement, Museums

Beth Staples: assistant professor of English, editor of Shenandoah

Emma Steinkraus: assistant professor of art

Jane Stewart: director of sustainability

Jill Sundie: associate professor of business administration

Chrissy van Assendelft: ITS business analyst

Dirk van Assendelft: director of core systems

Jessica Wager: assistant director of institutional history

Elizabeth Wislar: costume designer and shop manager, theater, dance and film

DANIELLE WOOD | SEPT. 21, 2023

In her keynote lecture, Danielle Wood offered a dramatic introduction to our theme by entering the Stackhouse Theater stage while reciting the poem “Myself” by George Moses Horton, an enslaved person from the 19th century. Wood’s presentation interweaved “the inspiring strains of ancient lore” and her own life story to explain how she thinks about what equity means for space access.

Wood explained how the aspirations from the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 entail that all states have the right and, in theory, the opportunity to participate in space. However, countries with fewer resources are often disadvantaged by the way space technology is created and framed. For example, Wood explained how small satellites are often created to have a long lifespan; however, a different engineering philosophy could entail that small satellites could also be made more cheaply and developed collaboratively by “emerging space nations.” These satellites are important because they allow for countries to create maps that can address pressing social and ecological issues.

Wood emphasized the importance of applying academic findings and making data useful. She encouraged us to use wisdom traditions and design toolkits in conjunction with each other, and she walked

us through some ways she uses system engineering as a design framework. She explained a simplified process, where a design challenge can be answered by asking about context, examining stakeholders and then considering, “What actions do I need to take to address this problem?” and “What are the tools we can put in place to do that?” This process, she explained, helps her work with local communities all over the world to answer the questions that are meaningful to them.

Wood connected space findings to the Sustainable Development Goals put forward by the United Nations and argued that technologies from space can improve life on Earth, even if that’s not what they were designed for. Wood shared current examples of her work. She explained a project she worked on in Benin, where the invasive water hyacinth plant grows in a lake people depend on for access to trade and education. Wood’s team helped track the growth patterns of this invasive plant, which then supported a company that created local jobs in harvesting the plant and turning it into a fiber that can clean oil spills.

Wood concluded by discussing a current project where she is testing the viability of using beeswax as rocket fuel, once again connecting the Earth to the stars.

Danielle Wood is an assistant professor of media arts and sciences, aeronautics and astronautics as well as the director of the Space Enabled Research Group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Her research considers how we can repurpose satellites to change the world for the better. Collaborating with local and national governments, nonprofits and entrepreneurial firms, Wood and her team identify opportunities for space technology to improve public services and solve global problems.

GEORGE

George Aye argued for design practices that are attuned to power. Designers, Aye asserted, need to do work that actually helps. Unfortunately, there are some practices baked into the discipline of design that may put designers at risk of straying from their values or doing more harm than good. Aye’s presentation emphasized his mission to change the way design functions and described his tools for enacting ethical design processes.

Aye argued that the standard of “humancentered design” can be problematic. He opened by telling the story of Juul electronic cigarettes as an example of a product design that is very much attuned to humans yet, ultimately, unethical with regard to its impact on health. Aye explained that the formal discipline of design is a morally agnostic and craft-based framework. Although many disciplines train us to say yes, we need to listen to our quiet little voice that questions whether something is truly the right thing. Designers — and other professionals — need to be comfortable saying no to projects that compromise their values.

The work of Aye’s Greater Good Studio is shaped by a set of key beliefs: The status quo is unacceptable; lived experience is a form of expertise; and design is transformative. He explained that design companies originated

for commercial design, but design studios can do transformative work in new spaces, like nonprofits. For prospective clients, his firm’s workflow begins with implementing a specific methodology to decide whether their team is best situated to do the work at hand. Studio staff members collaboratively assess factors such as how various community stakeholders would be involved in the project, whether the goals can be realistically met and what unintentional effects may result from the work. At times, this process shows why and how a project might not be a good match for the studio, and Aye described how he communicates this respectfully to clients.

Aye encouraged us to interrogate where power is and how power operates in the interactions that govern our work. He drew attention to power asymmetries, such as such as those between government and community, client and designer, employer and employees, and teacher and student. These power structures, and the crystallized professional practices that maintain them, can make it challenging for us to stay true to our values as we carry out our work. However, it can help to create and faithfully utilize methodologies and collaborative practices that consistently bring our focus back to values.

Jennifer Blumenthal-Barby’s Ethics of Design lecture addressed how health care providers might use “nudges” to lead patients toward medical decisions that are in their best interest and in accordance with their values and goals. She began by explaining how patients exercise autonomy in a medical setting. In the ideal, a physician’s task is to remove impediments to autonomy so that patients can exercise their values. However, the emerging field of decision science has shown that a patient’s decision-making process often relies on intuition and impulse, not consideration and understanding. Blumenthal-Barby works on what ethical choice architecture may look like in medicine and how autonomy can be promoted given the nuances of human cognition.

Blumenthal-Barby familiarized us with some of the biases that patients, as human beings, often rely on in medical decision-making. For instance, we tend to feel losses more acutely than gains of equal magnitude (loss aversion). We tend to choose action over inaction (commission bias), even when inaction would be the better option. Also, our decisions tend to be most powerfully influenced by information that we learn first or last (primacy and recency bias). She offered examples of how these heuristics influence decisions across domains of medicine including cancer treatment, vaccination, organ donation and end-of-life planning.

Blumenthal-Barby explained that our knowledge of heuristics and biases in medical decisionmaking challenges the assumption that patients are making autonomous decisions. We hope patients are making decisions based on sufficient understanding and reasoning and that they are

able to appreciate what a choice means for them. Indeed, the concept of autonomy fundamentally implies that choices are self-governed and belong to the agent. However, given the evidence that our decisions can vary in predictable ways according to the design of information available to us, the ideal of autonomy is challenged.

These concerns need not mean that we return to full paternalism; rather, we can harness our knowledge of decision-making heuristics and help patients make decisions that are in line with their interests and values. Once we know how people make decisions, we can use this knowledge to structure the way we present decisions so that we get closer to the values that autonomy is meant to achieve.

Blumenthal-Barby added that when contemplating the use of nudges, health care providers should be sensitive to specific conditions of a patient’s decision-making. For instance, it is important to understand why a patient makes a choice within the patient’s own values. For example, a practitioner may think a patient should accept treatment, but it matters whether that patient is refusing due to a religious objection or because they are deferring to a heuristic. Finally, the clinician-patient relationship should be valued, and it is paramount to ensure that patient does not feel alienated or feel manipulated.

Blumenthal-Barby concluded by explaining current projects on tough cases. She invited the audience to examine some real-world questions of how to respect the values of patients, even when our “ideal” concept of autonomy may not match the reality of human decision-making.

Jennifer Blumenthal-Barby is the Cullen Professor of Medical Ethics and associate director of the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy at Baylor College of Medicine. Her work explores ethical questions raised by research on human judgment and decision-making. She analyzes ethical issues raised by “nudging” patient decision-making and argues that the practice can improve patient decisions, prevent harm and perhaps enhance autonomy.

Sara Hendren interrogated the assumptions implicit in many designs: that design should be universal, that we know what a user wants and that designs will be used by a particular type of person with a particular type of body. Hendren merges the domains of art, design and engineering to imagine and create technologies for people with varied physical bodies and needs. She views this work as not merely an additive process that allows the user to engage with the world, but as a process that pushes the world to change for the user.

As a designer, Hendren problematizes the way we perceive disability and disability technology. Instead of asking how people can be fixed or made to fit in better with the world that exists, she wonders, “Why must the way things are be the way things are?” When people with disabilities ask for rights, they are asking that the built world “shift its shape” to make room for those who have been excluded. Hendren pushes the world to new shapes and forms by attending to the needs and ideas of individual users. This helps all of us understand the world to have more potential.

Hendren has created ramps to be used both by wheelchair users and skateboard artists to show the ways that a city can be explored anew by all kinds of people who use wheels. She has worked with an art lecturer to design a small-stature podium. When the lecturer, who is under 4 feet tall, uses the podium Hendren created, it creates an encounter for audience members in which they see the dimensions of all surrounding furniture differently. Hendren

has even revised the very symbols we use to indicate access, creating a wheelchair user in motion to indicate accessibility.

She entreated us to be “a little less certain, a little more aware,” and to examine stories outside of universality. She demonstrated the care she gives each design process, urging the audience to understand that design doesn’t need to be concerned necessarily with mass problem solving or a one-size-fits-all solution, but can in fact engage precisely what makes us unique and recognize and celebrate human diversity.

Expansive thinking about disability and design can raise provocative questions. For instance, Hendren is concerned about the “remedicalization” of human normalcy and asked the audience to consider questions of selective termination on the basis of disability. She also brought up the movement toward assistive dying as a place for deeper conversation, stating her own uncertainty as well as a worry that we may move toward “eliminating suffering by eliminating sufferers.”

Hendren views design as the confluence of utility and significance for the person a product is designed for and for the world at large. Design should allow all of us to understand the narrowness of the things we have already built and dream of ways to create more expansive design that’s sensitive to the needs of individuals.

Sara Hendren is an artist, design researcher, writer and humanist who works as an associate professor in art + design and architecture at Northeastern University. She teaches design for disability and reframes the human body and technology through collaborative public art, social design and writing projects. Her adaptation + ability group uses a capabilities approach to develop adaptive technologies because “some bodies do some things, and others do others.”

Elgin Cleckley is an assistant professor of architecture and design and the University of Virginia. He is the principal of _mpathic design, a multi-award-winning pedagogy, initiative and professional practice that uses evidence-based methods grounded in cultural competency, empathy and human-centered design. His work operates at the intersections of identity, culture, history, memory and place. His methodology provides tangible toolkits and frameworks for developing belonging in public space.

Elgin Cleckley launched his talk by explaining his journey through design. First learning empathic design practices from family quilts, he then attended design school, where the model of training emphasizes that designers should dictate and control actions. He had to navigate the tension between appreciating aesthetic beauty and thinking about who created that beauty. This led him to develop methods that take in the present but also acknowledge the past. Cleckley explained that in practice, it is our emotional reaction that defines spaces. Designers that respect this can create spaces and experiences that are rooted, intergenerational and connected.

Cleckley established his design approach, _mpathic design, while working with students to create a historical exhibit that acknowledged a painful history. He emphasized the difficulties but also the importance of laboring to repair harm that one did not create. He reminded the audience of the power of empathy to reconnect and re-engage, using an academic understanding of empathy from psychology and metaethics to live out empathetic values.

The absence of the “e” in _mpathic design not only provides a visual representation of space, but also represents the removal of ego in the design process. In this form of design, designers acknowledge often untold, marginalized narratives of the past while operating with care in the present. Cleckley emphasized the importance of self-analysis to meet communities whole-heartedly. The phases of his _mpathic method allow designers to process emotion and co-create with community through exploration, uncovering and connection.

This _mpathic method has been applied in local, national and global projects. Among his Virginia projects is the Charlottesville Memorial for Peace and Justice, which memorializes a lynching. He explained how he chose to orient a body column with a view of Monticello, with axes toward the site of a slave market, Confederate statues and the courthouse. Cleckley also discussed his collaboration with the Anne Spencer House and Garden. This project involved the creation of an empathic ecosystem for middle-schoolers and college students, who were brought in as designers.

Cleckley ended by discussing the haunting image of the British slave ship the Brookes, and his current project, which invites a modern audience to connect with the legacy of the Brookes in a wholly new way. Cleckley was struck, and had been considering for years, the way architectural plans were used to describe the horrors of the slave trade. He then walked the audience through his arduous process of reinterpreting the infamous image of the Brookes, including diving into the data of what the image entailed. Cleckley created visual “memory markers” to recognize and respect the human beings the Brookes carried. He explained his process of immersing himself in harrowing data and the efforts of physical execution, as well as the connections he aimed to create with this work, for example, linking “memory marker” colors to quilts of West Africa.

Concluding with this intimate look at the emotional impact involved in his design process, Cleckley reminded us of the importance of taking care of oneself as a designer who will have an emotional response to a powerful design process.

Candy Chang presented the last lecture in the Ethics of Design series. Chang works on public art that invites people to share their inner lives in beautiful, vulnerable and anonymous ways; much of Chang’s work centers on “things that you don’t typically tell a stranger.” She explained how her work involves reimagining an ethics of uncertainty for our time and a way to build up the emotional health of our civic life.

Chang expressed gratitude for her own meandering journey from architecture, to graphic design, to urban planning. Her street art emerged from postering and from imagining things she wished existed in her neighborhood. She noted that public spaces are often designed for the highest bidder, so her work offers an opportunity for the values of a community to be reflected in its shared space. The outward expression of these values can help foster inner calm but also connection as we come to understand the deep human commonalities we share.

Chang’s lecture was full of seeming juxtapositions and surprise. She explained how anonymity is often associated with worst behavior but in fact allows us to share without fear of judgment.

She also spoke to the need to create space for uncertainty. Ethics is often thought to be clear views about what is right and what is wrong, but Chang spoke to “uncertainty as an ethical stance,” as reaction to pains of our age. Contrary to the idea that we all must proceed

with certainty and confidence, Chang explained that projects come from feeling confused, uncomfortable or out of place, but those struggles can be turned into service for others. Often, we feel like we have to hide confusions, but in fact these confusions are a source of connection and strength. Through sharing hopes, we can remember what we are capable of, and by sharing anxieties, we can realize we’re not alone.

Chang explained that we often experience others as we experience a city, at least initially: We view only facades. Our online platforms, for example, do not encourage nuance but judgment and comparison. However, each of us has the power to transform our spaces to reflect how we want the world to be.

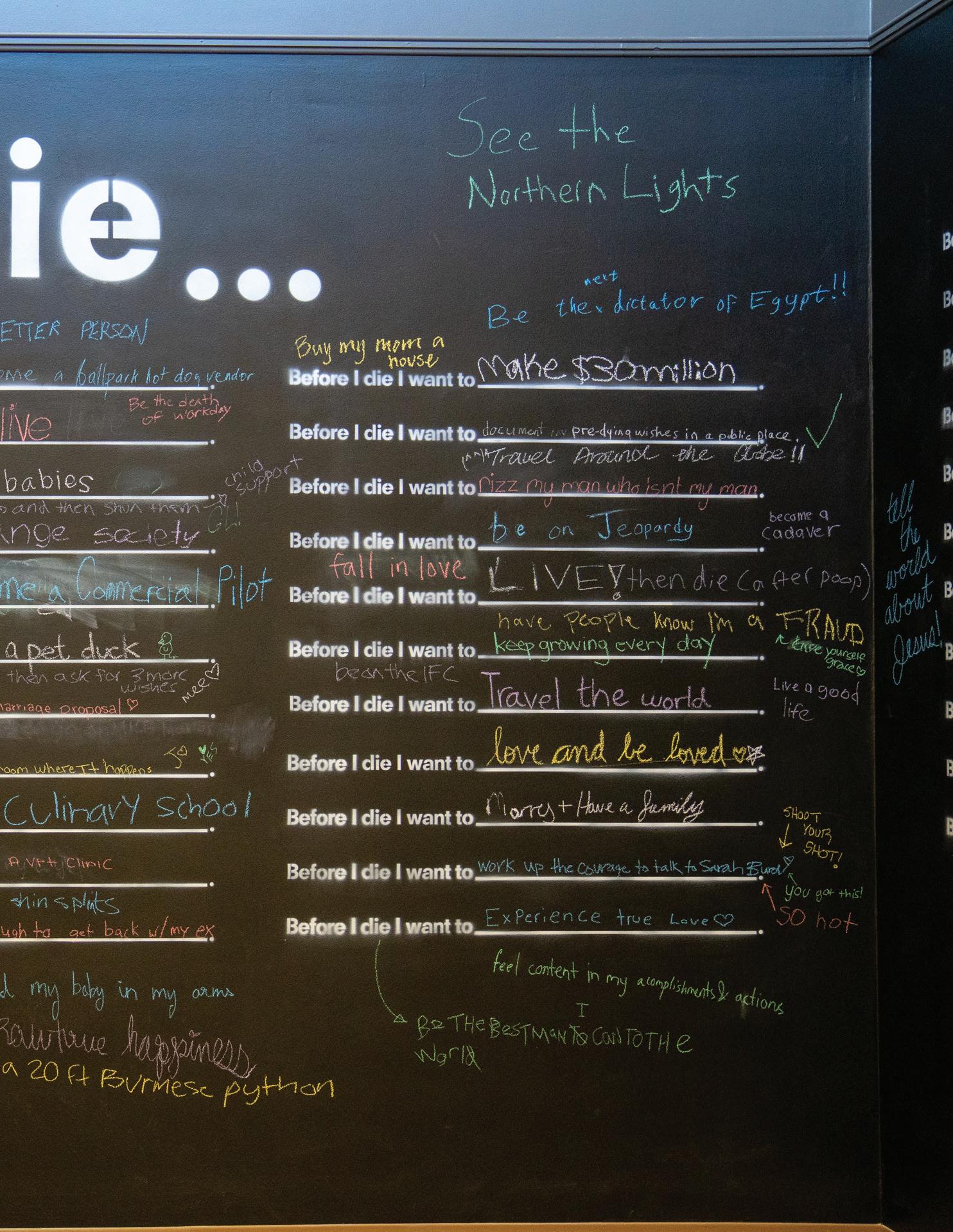

Chang explained the origins of her iconic “Before I Die” walls. This now-global project began as her homage to a mentor who had passed away and a mechanism for expressing humor, fear, joy and pain publicly. “Before I Die” walls serve as a way to interrogate what matters to you and to see what matters to others. There have been over 5,000 “Before I Die” walls all over the world, each wall serving as “a tribute to living an examined life.”

Chang concluded by encouraging us to take the meandering, unexpected creative path of “making the thing I wish existed in the world.” She, too, shared some of her current projects, which involve creating art from the responses her art has elicited — an unexpected, but fitting, conclusion.

As an extension of his public lecture, this workshop was facilitated by George Aye, co-founder of the Greater Good Studio. This social design consultancy has been using and refining its own “gut check” methodology as an integral part of its practice for 12 years.

Through facilitated discussions, interactive exercises and consideration of examples from the Greater Good Studio, W&L students, staff and faculty contemplated past and future choices about their work. They explored their own experiences of previous team-based projects, identified themes and values within this work and discussed how they might judge their own boundaries in the future. Aye addressed the issue of shared fears regarding reputational damage, judgment or retaliation for carrying out values-driven work. Participants saw examples from Greater Good Studio of when their staff said, “No, and here’s why ...” to prospective clients. The Gut Check Workshop gave participants practice with tools that can enable an ethical design practice.

Steve Wei (they/he), a Philadelphia-based fight director, choreographer, performer and instructor, led a workshop for W&L students, faculty and staff to explore their assumptions and emotions around touch and consent. As a stage combat expert, Wei is devoted to an artistic culture that promotes the ethical production of dramatic violence. They have performed in dozens of productions in the greater Philadelphia area and helped create fights for many more.

The workshop began with a simple game in which participants were invited to say “yes” or “no” to the opportunity to stand in the middle of a circle. Wei then walked participants through partnered exercises such as describing and stating preferences for a handshake and creating plans for how to build unusual moments of partnered contact. Amid some giggles, these seemingly simple activities in the workshop built on one another so that, by the end, participants felt comfortable with extensive conversation and describing what felt OK and what did not. Wei then explained their practical method for how we can describe our bodies and comfort level to one another so that we take care of ourselves and others when we work together.

In collaboration with Leyburn Library, the Mudd Center produced a Human Library® Reading as part of the Ethics of Design program. Originating in Denmark over 20 years ago, the Human Library® was designed to help people “unjudge” one another through dialogue. Human Books are people who volunteer to start a dialogue about an aspect of their experience or identity that’s exposed them to stigma, hardship, prejudice or misunderstanding. Readers sign up to “check out” a Human Book so they can listen, learn and ask questions. The Human Library® provides a safe space for us to talk about things that otherwise we might not. Difficult questions are expected, appreciated and answered. By acknowledging and challenging the judgments that we all carry toward one another, the Human Library® allows us to practice the art of curiosity through personal conversation.

During the fall of 2023, 10 W&L students, staff and faculty volunteered as Books to discuss their experiences related to topics such as mental and physical health, gender, citizenship, sexuality or trauma. They participated, along with other Books from all over the world, in a virtual training program produced by the Human Library® organization in Copenhagen, Denmark. The Books selected a title for their story and practiced framing it for others. During the W&L event in January of 2024, our Human Books provided Readers with insights in a series of three 30-minute small group discussions.

Like other experiential aspects of the Ethics of Design program, the Human Library® supplied a framework for participants to practice actualizing their values through curiosity, listening and connecting with others.

JANUARY – JUNE 2024

The Mudd Center installed a Before I Die wall in Leyburn Library as a complement to Candy Chang’s public lecture entitle “Designing Space for Uncertainty.” Before I Die is a global participatory art project created by Chang, a world-renowned urban designer and artist. These interactive exhibits, constructed in public spaces, invite people to reflect on their mortality and consider the things that matter most. To date, there have been over 5,000 Before I Die walls constructed in 78 countries and 36 languages around the world.

Chang launched W&L’s installation with an artist’s talk on Feb. 19, 2024, during which she discussed the healing power of community members connecting with one another on issues of deep, gut-level concern. Throughout the Winter and Spring terms, W&L’s Before I Die wall was repeatedly filled, erased and filled again with fresh responses by students, faculty and staff.

In an effort to bolster the integration of ethical reasoning pedagogy in W&L’s curriculum, the Mudd Center produced a special initiative in 202324: The Ethical Reasoning in Action (ERiA) Faculty Learning Community. The empirically supported ERiA strategy was developed at James Madison University (JMU) as a component of their campus-wide student orientation program. W&L’s Faculty Learning Community provided support for instructors from all disciplines to translate the principles of ERiA into lesson plans for their topical courses.

Drawing from research in psychology, neuroscience and behavioral economics, the ERiA approach is designed to foster students’ ability to recognize and analyze moral aspects of a situation and make ethically informed decisions about it. It revolves around Eight Key Questions (8KQ) that can be applied to evaluate the ethical dimensions of a situation: fairness, outcomes, responsibility, consequences, liberty, empathy, authority and rights. The ERiA program seeks to help students develop a habit of mind that engages deliberative reasoning processes instead of defaulting to automated moral intuitions.

Sixteen W&L faculty members attended eight in-person workshops during the academic year, developed lesson plans for a topical course and implemented the plans during the Winter Term of 2024. Workshop sessions were coordinated by Karla Murdock, Mudd Center director and professor of cognitive and behavioral science, in collaboration with Christian Early, associate professor of philosophy and director of the ERiA program at JMU. It is hoped that this Mudd Center investment will seed faculty members’ expertise and motivation to address discipline-specific, ethically complex issues in their courses across the curriculum.

• Jumana Al-Ahmad, visiting professor of Arabic

• Michelle Cosby, assistant dean of legal information services and professor of practice

• Andi Coulter, assistant professor of business administration

• David Eggert, professor of law practice

• Elisabeth Gilbert, assistant professor of business administration

• Megan Hess, associate professor of accounting

• Janet Ikeda, associate professor of Japanese

• Dan Johnson, David G. Elmes Term Professor of Cognitive and Behavioral Science

• Julie Kane, professor and collection strategies librarian

• Li Kang, assistant professor of philosophy

• Mengying Liu, assistant professor of engineering

• Sybil Prince Nelson, assistant professor of mathematics

• Howard Pickett, director of the Shepherd Program and associate professor of ethics and poverty studies

• Jaime Roots, visiting assistant professor of German

• Holly Shablack, assistant professor of cognitive and behavioral science

• Kary Smout, associate professor of English

The 2024 Mudd Undergraduate Ethics Conference was hosted by Editor-inChief Margaret Thompson ’24 and Associate Editor Amanda Tan ’26. It featured paper presentations on diverse ethics topics by three undergraduate students. First, Benedict Loo U-Hui of the National University of Singapore presented “Nudging and Paternalism: A Critical Examination of Their Permissibility and Potential Implications in Contemporary Policymaking,” which was followed by a response from W&L Editorial Board member Claire DiChiaro ’26. Erica Esterly of the United States Military Academy at West Point presented “On Identity and Epistemological Understanding,” to which Sydney Smith ’24 and Tan responded. Finally, William Bray ’26 of Washington and Lee University presented “Can Objective Aesthetics be Used for Valuing Nature?” followed by a response from Natalie Eger ’27.

The conference featured a keynote lecture entitled “Play, Spontaneous Freedom and the Avant-Garde” by Professor Jonathan Gingerich of Rutgers University. Gingerich’s research explores ways in which moral and political philosophy can be enriched by attending to experiences that are often neglected in contemporary normative theory, such as experiences of spontaneity, artistic creativity and cultural participation. He is developing a novel theory of freedom focused on the freedom of unplanned and unscripted activity, which he calls “spontaneous freedom.” More information about Gingerich’s work is available at jonathangingerich.net

Members of the 2023-24 Editorial Board included Thompson ’24, Tan ’26, Watson Deacon ’24, Bella Devraj ’25, DiChiaro ’26, Eger ’27, Sam Griffiths ’24, Elias Malakoff ’25, Charlie Moore ’23, Rebecca Nason ’25, Saaraim Núñez ’27, Siya ’27, Smith ’24, Margaret Witkofsky ’24 and Teresa Yoon ’26. Faculty mentorship was provided by Rachel Levit Ades, Mudd Center for Ethics postdoctoral fellow.

The Mudd Center welcomed Rachel Levit Ades as its new postdoctoral fellow in 2023-24. Having completed her Ph.D. in philosophy at Arizona State University in 2023, Levit Ades’s areas of specialization are the philosophy of disability, applied ethics and social and political philosophy. She is interested in questions about difference and imagination and what it means to participate in the world. Levit Ades has worked in deaf education, special education and inclusive arts education, and she is passionate about community projects that apply ideas about ethics and access. In 2023-24, she taught a partner course for the Mudd Center’s Ethics of Design theme as well as an inventive new Spring Term course called Images of Justice.

As the 2023-24 academic year draws to a close, Karla Murdock will return to her post in the cognitive and behavioral science department and Melissa Kerin, associate professor of art history, will bring new leadership to the Mudd Center. Kerin’s research explores the complex relationships of art with political and cultural identity formation. She teaches courses on South Asian and East Asian art and architecture. In 2017, Kerin served an instrumental role in organizing the Mudd Center’s conference titled, “The Ethics of Acquiring Cultural Heritage Objects,” which brought together the disciplines of archaeology, art, art history, economics, ethics, law and museum studies to investigate the role of Western art markets in perpetuating looting systems and black markets.

Kate Saacke will continue to serve the Mudd Center’s mission in 202425 by bringing her extraordinary skill, resourcefulness and good humor to a new role as the Mudd Center’s senior program coordinator.

The Mudd Center will explore the layered and productive relationships among ethics, medicine and narrative to examine aspects of the four pillars of medical ethics: autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice. Central to our yearlong investigation will be the voices of physicians, ethicists and artists, among others, to understand better how sharing and listening to personal stories can inform ethical considerations related to diagnostics, interventions, research and policy. Moreover, the fields of narrative ethics and medical humanities have demonstrated how stories and story-sharing are generative and relational practices that may serve as sources of resilience and well-being for patient, provider and the surrounding community. Through multiple points of engagement, we will explore questions related to human suffering, justice, responsibility and equity in how we live and die.

Mudd Center for Ethics