Sandy de Lissovoy: Floating Topographies, New Work, and Collaborations

Paula Burleigh Assistant Professor of Art History, Allegheny College

On Mountains and Mapping

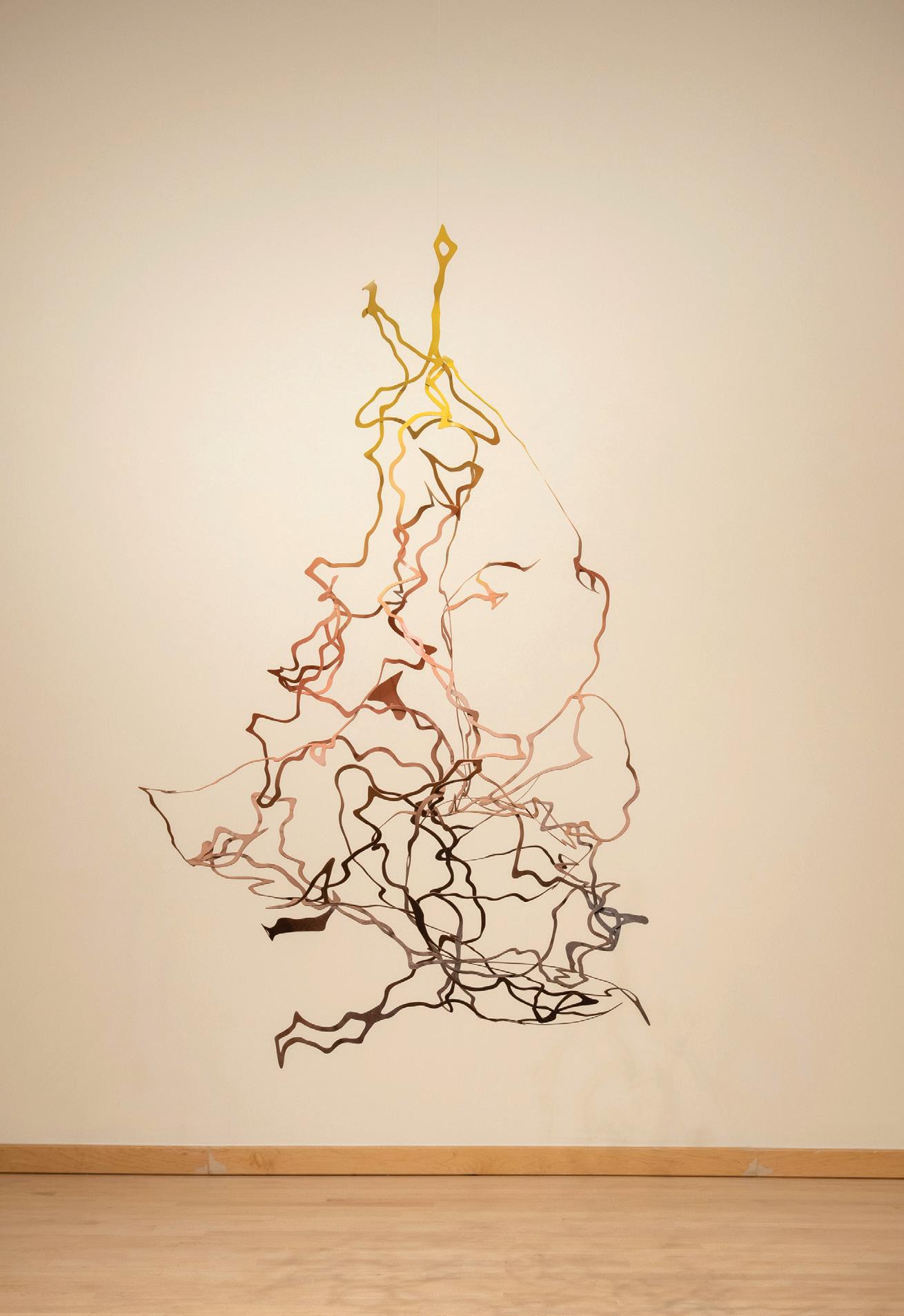

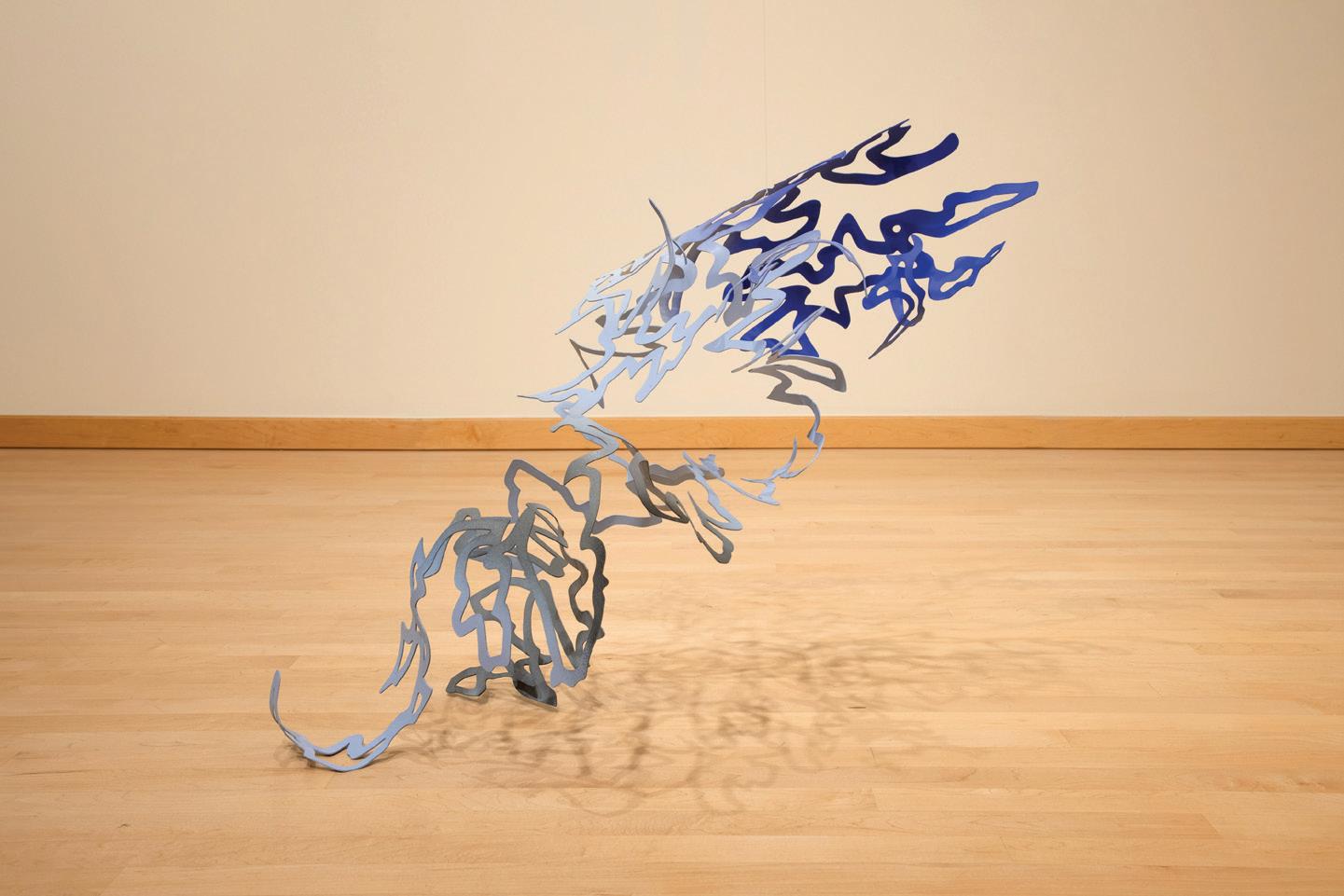

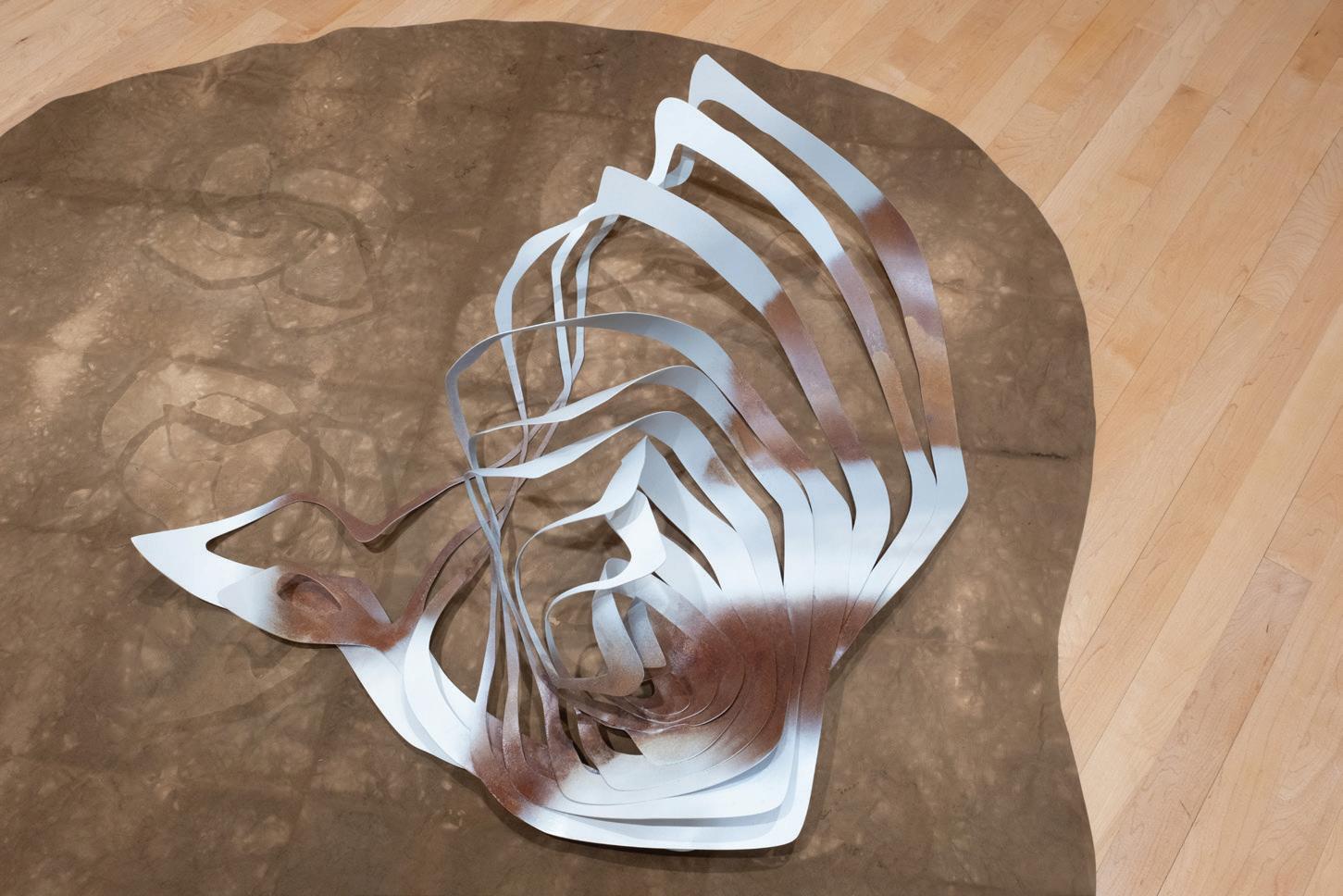

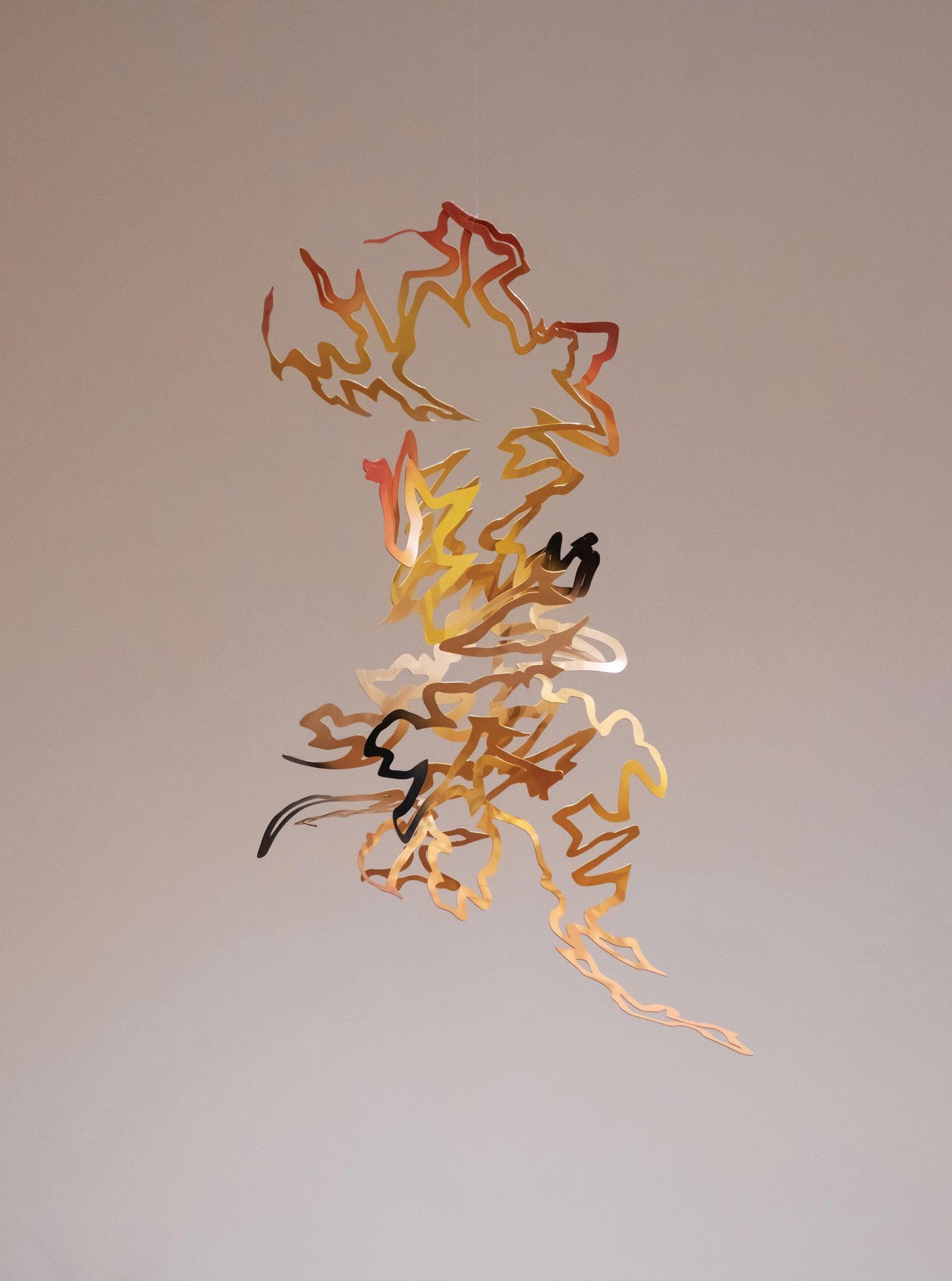

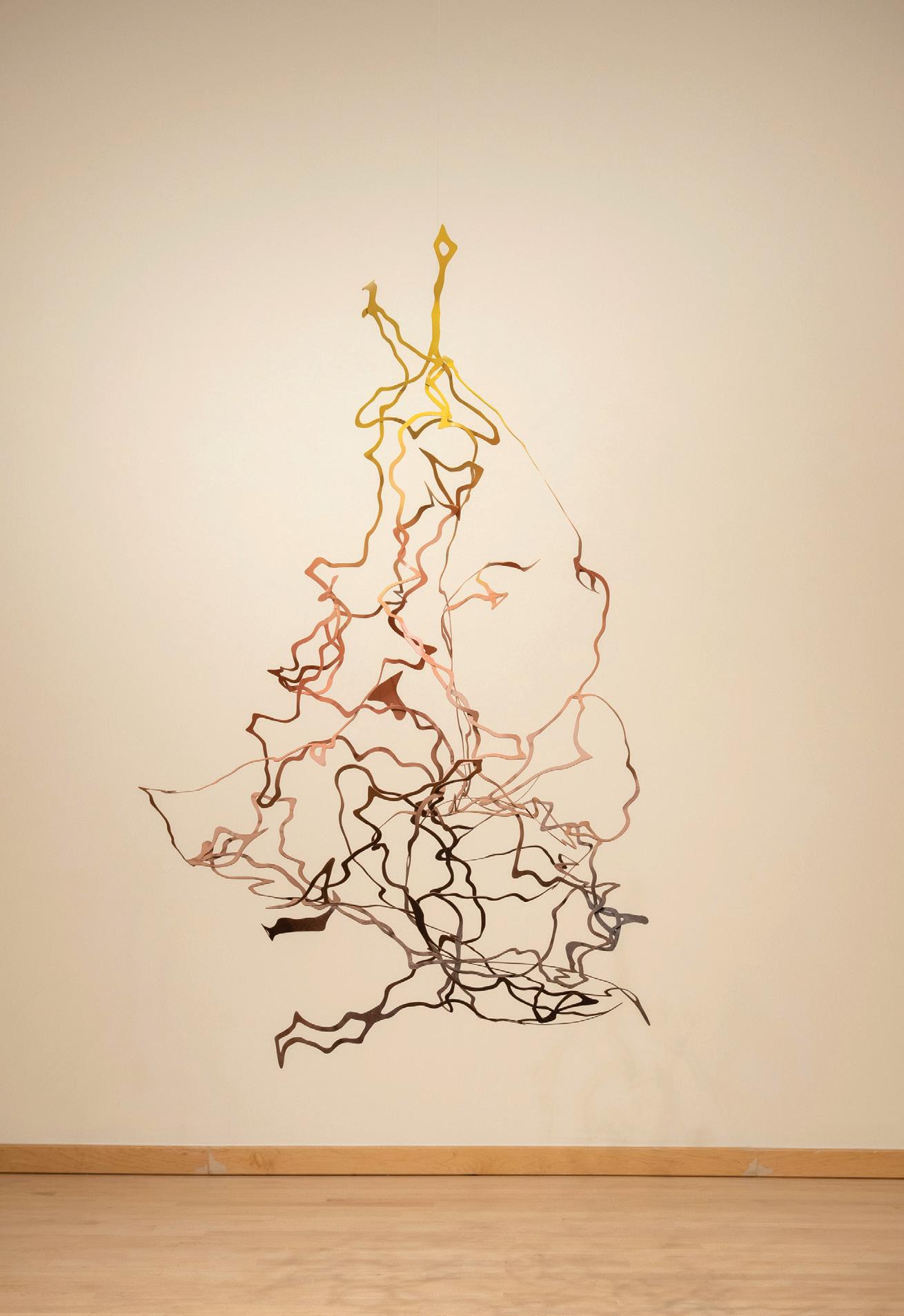

IN THE MIND’S EYE, A MOUNTAIN IS SOLID, PONDEROUS, AND STATIC. BY contrast, sculptures in Sandy de Lissovoy’s Mountains series (2021–23) are open forms comprising sinuous lines of steel and negative space. Despite their delicate nature, de Lissovoy’s compositions share DNA with the rugged terrains of the Sierra Nevada mountain range and the Appalachian Mountains. The artworks begin with topographical maps made by the National Geospatial Program, an initiative of the United States Geological Survey (USGS), which the artist accesses from their database. Topographical maps are recognizable for their distinctive elevation contour lines, which describe the shapes of mountains, the gradients of slopes, and the depths of bodies of water. The maps of Appalachia include mountains that have lost their peaks to surface mining, a process of mountaintop removal used to access coal seams. Working with the scanned maps in Adobe Illustrator, de Lissovoy hand-traces topographical data describing mountains that in many instances no longer exist. The re-drawn contour lines are then laser-cut from thin sheets of rolled steel. Working iteratively, de Lissovoy transforms these steel topographies into myriad forms: they become stencils for large drawings, their outlines register on the surfaces of dyed textiles, and they are bent, rolled, and otherwise manipulated into sculptural interpretations of mountains that live on the floor, wall, or are even suspended in midair. Their colors are elemental, evoking minerals, earth, sky, water, and foliage.

De Lissovoy’s sculptures and drawings challenge assumptions about what a mountain can be. In the popular imagination, mountains are immutable. By virtue of their magnitude, we tend to regard them as fixed structures, immune to time’s passage. Their grandeur inspires awe, and, especially in Western contexts, there can be an adversarial orientation––to climb a mountain represents a deeply rooted desire among humans to not only experience nature, but also to triumph over it.

4

The sculptures in de Lissovoy’s Mountains series, however, are both vulnerable and time-bound. The suspended works are surprisingly kinetic, rotating in response to the slightest air movement. On the floor below Hobet Ochre (2023; figs. 1–2), scattered fragments of steel look like they’ve fallen, as if the mountain is performing its own dissolution. Undermining the monumentality typically associated with steel, the intricately cut contour lines behave like drawings in space, which gesture toward mountains in a constant process of (un)becoming as they move or appear to shed. Unlike mountains that reside in the public imagination, these natural forms are contingent on human-engineered industries as well as the fluctuations catalyzed by climate change (which those same industries accelerate)—the mountains of the Sierra Nevada, for example, have undergone radical topographical shifts owing to wildfires and melting glaciers.

Topographical maps use a standardized cartographic language to compress expansive physical terrain into flat, legible guides. Those guides are useful to hikers, for example, which is how de Lissovoy initially became familiar with them. Such maps—particularly in the United States—also reflect histories of human technology, power, and desire exercised upon natural landscapes. The USGS began mapping the nation’s topography in 1879, when it was established as the United States’ primary civilian mapping agency. But before 1879 and in some cases after, topographers held positions in the military, where they were charged with developing maps that would guide maneuvers in battle.1 And while the USGS is not affiliated with the military, its topographers nonetheless benefit from military-grade technology—namely aerial photography and photogrammetry (the technique of measuring three-dimensional objects or terrain from photographs), both used for intelligence—which dramatically increased the coverage, detail, and accuracy of topographical maps following the Second World War. 2

Topographical maps made in the United States effectively abstract the complexities of landscape into a two-dimensional visual language rooted in nationalism, surveillance, and violence. In the artistic process of translating this source material, however, de Lissovoy maintains little fidelity to topographical data. Instead, he works in an intuitive, improvisatory mode to return the forms to three-dimensional space, liberating the spirit of the mountains from the systems of power in which the maps participate. By reducing the mountains to human scale but removing them from the descriptive, rational logic of their maps, de Lissovoy invites viewers to engage with the landscape as it is: vulnerable, shifting, and deeply intertwined with our own perilous futures.

5

Site and Nonsite

In 1968, American artist Robert Smithson—best known for the monumental earthwork Spiral Jetty (1970), a giant coil of basalt and earth jutting off the shoreline into Utah’s Great Salt Lake—wrote a theory of “nonsites,” a term he used to describe sculptures that function as abstract portraits of external locales by virtue of their materials. Smithson’s nonsite sculptures comprised bins filled with rock, sand, or concrete collected from specific places in New Jersey, and the resulting installation was, as Smithson wrote in a 1968 text, “a three dimensional logical picture that is abstract , yet it represents an actual site in N.J… . It is by this three dimensional metaphor that one site can represent another site which does not resemble it—thus The Nonsite.”3 Both the legacy of Earthworks and the logic of nonsites—to evoke a place through material rather than description—informs much of de Lissovoy’s practice.

The artist has worked extensively with textiles and natural dyes, creating objects that range in form from wall hangings to more elaborate, shaped structures suspended from the ceiling. De Lissovoy sources dyes that engage with specific histories of place, and the resulting artworks—however abstract—are imbued with those site-specific associations. While the natural dyes gesture toward places via their material histories—as in Smithson’s nonsite works—de Lissovoy likewise stages and documents installations in outdoor landscapes.

The artist treats fabric with dyes made from walnuts, or wood from Orange Osage (Maclura pomifera ) and Purple Logwood (Haematoxylum campechianum ) trees. The locally foraged black walnuts (Juglans nigra ) produce a rich brown hue, a pigment that serves as an indexical trace of the artist’s immediate environs. While the Orange Osage and Purple Logwood materials are not hand gathered, their distinctively saturated hues reflect site-specific histories of conquest and colonization. Both trees are native to the Americas, and each has been imbricated in fraught relations between Indigenous peoples and settlers. Purple Logwood, long used as a dye by the Nahua people in Mexico, captured the attention of the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés in the early sixteenth century and became a highly sought-after export to Europe. Because of its profitability as a commodity, logging camps and plantations were established in Central America and the Caribbean in which enslaved laborers were forced to cultivate and harvest the tree’s heartwood.4 Likewise, members of the Osage Nation, now in Oklahoma, valued Orange Osage for its rare combination of flexibility and strength, often making it into archery bows,

6

which were then traded with other Indigenous tribes including the Blackfeet in Montana and the Shawnee and Wyandotte in Ohio. 5 It was subsequently planted by European settlers to serve as prairie fencing—a precursor to modern barbed wire—in the mid-nineteenth century. 6

While these complex histories are not pictorially evident in de Lissovoy’s textile sculptures, they are nonetheless adjacent to the materials with which he engages. Wall-hanging textile works like Polytemporal Pilgrim and Double-Cut (2023; figs. 14–15) display subtle gradations of saturation on their surfaces, which conjure associations with geological strata—abstract portraits of land—and likewise with the nebulous transitions between fields of color in mid-twentieth century paintings by Mark Rothko or with the stained, unprimed canvases of Helen Frankenthaler. While Rothko, among other Abstract Expressionists, aspired to the condition of making a universal language in painting, de Lissovoy’s specific and intentional use of material pigments insists on just the opposite: an abstraction that is informed by the social conditions of culture, history, and place.

The inverse of the nonsite is the Earthwork—rather than gesturing toward an external site from the gallery, the work is situated in nature. However, de Lissovoy is not driven by the impulse to make monumental, permanent sculptures in natural landscapes—like Smithson, Nancy Holt, or Michael Heizer—but instead he adopts a more ephemeral practice of site-specific interventions. In the seven-minute video Long Walks with Ephemeral Indigo Interventions, California and Virginia (2022–23; fig. 17), de Lissovoy stages temporary installations in the California High Sierra and Virginia Appalachian Mountains, sites related to those that inspired the Mountains series. Temporarily anchored to the earth by aluminum rods, hand-dyed indigo textiles snap and unfurl in the wind. The frenzied movement in the video’s opening cuts to a passage of calmly rustling trees rife with autumn leaves, and later the indigo fabric appears at rest, draped over large rock formations.

With its stunning views and stark contrasts between the placid forest and relentless winds, Long Walks with Ephemeral Indigo Interventions evinces a reverence for nature that falls within the art historical scope of the sublime—representations that exalt both the grandeur and power of nature. The material presence of the textile alludes to human interlopers within the landscape, while its indigo pigment suggests both water and sky. Building on the work of Land art precursors like Michelle Stuart and Ana Mendieta, who staged temporary, low-footprint performances or installations in natural landscapes, de Lissovoy’s video suggests an ethics of

7

human engagement with nature that is predicated on ephemeral, anti-monumental interventions that leave nothing behind. Read another way, perhaps the textile evokes the invisible vulnerability of nature itself. The preternaturally still High Sierra mountains in the video’s opening background appear impervious to time, and yet the insistent movement of the textiles—struggling to remain upright—reminds us of the mountain’s susceptibility to forces like climate change.

Collaborating in Nepantla

Beginning in 2022, de Lissovoy embarked on a sustained artist collaboration with Ander Azpiri, based in Mexico City, and Griselda Rosas, based between San Diego and Tijuana. De Lissovoy and Azpiri met at Sculpture Space, an artist residency in Utica, New York, and their conversations expanded to include Rosas, whose background in fiber arts became a crucial catalyst for collaborations that followed. After a fertile period of exchanging ideas and artworks through the mail, the three artists convened in Virginia in 2023 for a shared experience of thinking and making alongside one another. The collaboration is inspired by the concept of nepantla, a Nahuatl word that describes a liminal state of existing “in between.” Gloria Anzaldúa, a pioneering writer of Chicana feminist and queer theory, defines nepantla as “uncertain terrain,” and a “bewildering transitional space.” 7 Anzaldúa’s phrases allude to the complexity engendered by collaboration, which requires the ceding of individual, artistic authority in favor of an approach in which this individual is not assimilated, but becomes part of a hybrid, collective process.

The three artists produced several artworks together (figs. 18–24), including a monumental weaving itself titled Nepantla (fig.18). Weaving—a process of transforming individuated strands into a unified structure—is an apt metaphor for nepantla. In the woven Nepantla, a vibrant horizon of magenta snakes across a sea of ruddy brown. Bright sinews of orange flash from an otherwise monochrome white background. Natural and synthetic ropes are woven together with wire, PVC hose, and extension cords. These unlikely, occasionally discordant juxtapositions suggest a cacophony of viewpoints coalescing into the woven panel. In places, especially near the bottom of the work, the woven surface looks like a landscape viewed from far above. It does not, of course, correspond to any specific topography. Ultimately, Rosas, Azpiri, and de Lissovoy engaged in speculative cartography: Nepantla evokes a previously unknown geography that three artists charted together through the enriching and at times fraught process of communicating from differing cultural vantage points.

8

In a video by Azpiri documenting the collaboration, the artists communicate in a patchwork of overlapping Spanish and English—Azpiri and Rosas are both native Spanish speakers, whereas de Lissovoy is not—which gives way to moments of both joy and misunderstanding. Ruminating on the state of “in betweenness” in which new identities are forged, in the video Azpiri remarks, “Together we’re nepantla— we’re not here, we’re not there; we are embracing three different styles of working … it is not a mixture where everything is dissolved; instead, our ideas collide.”

Anzaldúa used nepantla to characterize moments of transformation, when “two or more forces clash and are held teetering on the verge of chaos, a state of entreguerras.”8 This impulse to inhabit spaces on the precipice of radical change is operative throughout de Lissovoy’s practice, as the artist—like all of us—witnesses the transformation of the climate and the planet within our lifetime. And we are on the precipice of even more catastrophic transformations incited by centuries of willful destruction to our environment. De Lissovoy’s video Our House is on Fire (fig. 25) features a textile-based structure situated outdoors, painted with text that reads, “our house is on fire,” a phrase made famous by the young climate activist Greta Thunberg. As a lens through which to understand the artist’s practice, the video foregrounds de Lissovoy’s work of both exposing and exploring nature’s extreme conditions of precarity.

9

Endnotes

1 Matthew T. Boan, “Sketch of a Nation: Mapmaking and the U.S. Army,” Army History, no. 119 (Spring 2021): 26–31.

2 “Topographic Mapping,” United States Geological Survey, www.usgs.gov/ educational-resources/topographic-mapping.

3 Robert Smithson, “A Provisional Theory of Nonsites,” in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings , ed. Jack Flam (Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996), 364.

4 Carlos Ortiz-Hidalgo and Sergio Pina-Oviedo, “Hematoxylin: Mesoamerica’s Gift to Histopathology. Palo de Campeche (Logwood Tree), Pirates’ Most Desired Treasure, and Irreplaceable Tissue Stain,” International Journal of Surgical Pathology 27, no. 1 (2019): 4–14.

5 “Osage Apple (Orange),” National Park Service, www.nps.gov/articles/ osage-apple-orange.htm.

6 Douglas Main, “The Odd History of the Orange Osage Trees,” National Geographic (November 23, 2021), www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/ hedge-apple-osage-orange-ghost-of-evolution.

7 Gloria Anzaldúa, “Border Arte: Nepantla, el lugar de la frontera,” in Light in the Dark / Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identify, Spirituality, Reality, ed. AnaLouise Keating (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 56.

8 Anzaldúa, “Border Arte,” 56.

10

Catalogue of Work

11

12

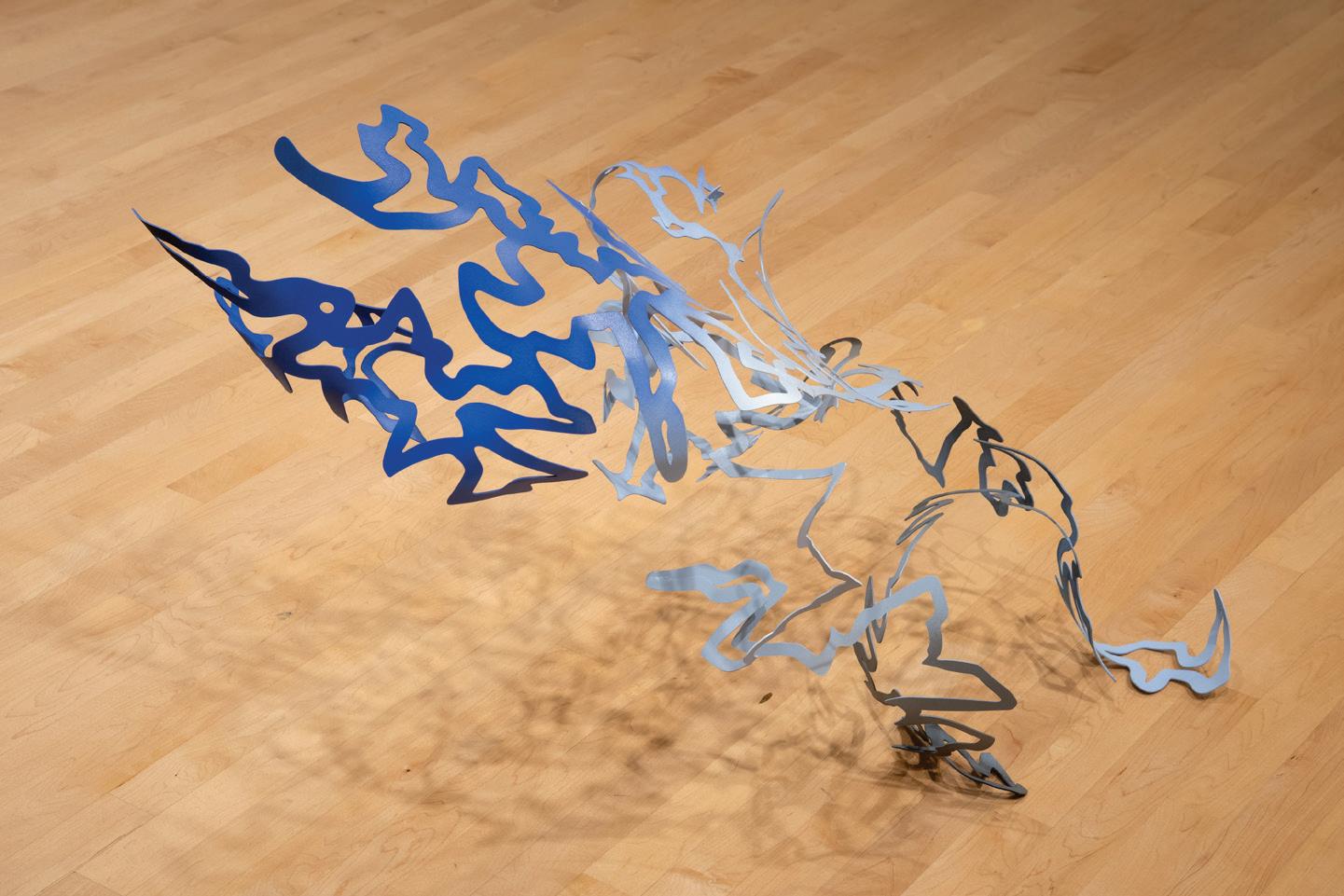

Figure 1 Hobet Ochre, 2023 Steel, paint, string, 34 x 18 x 27 in.

13

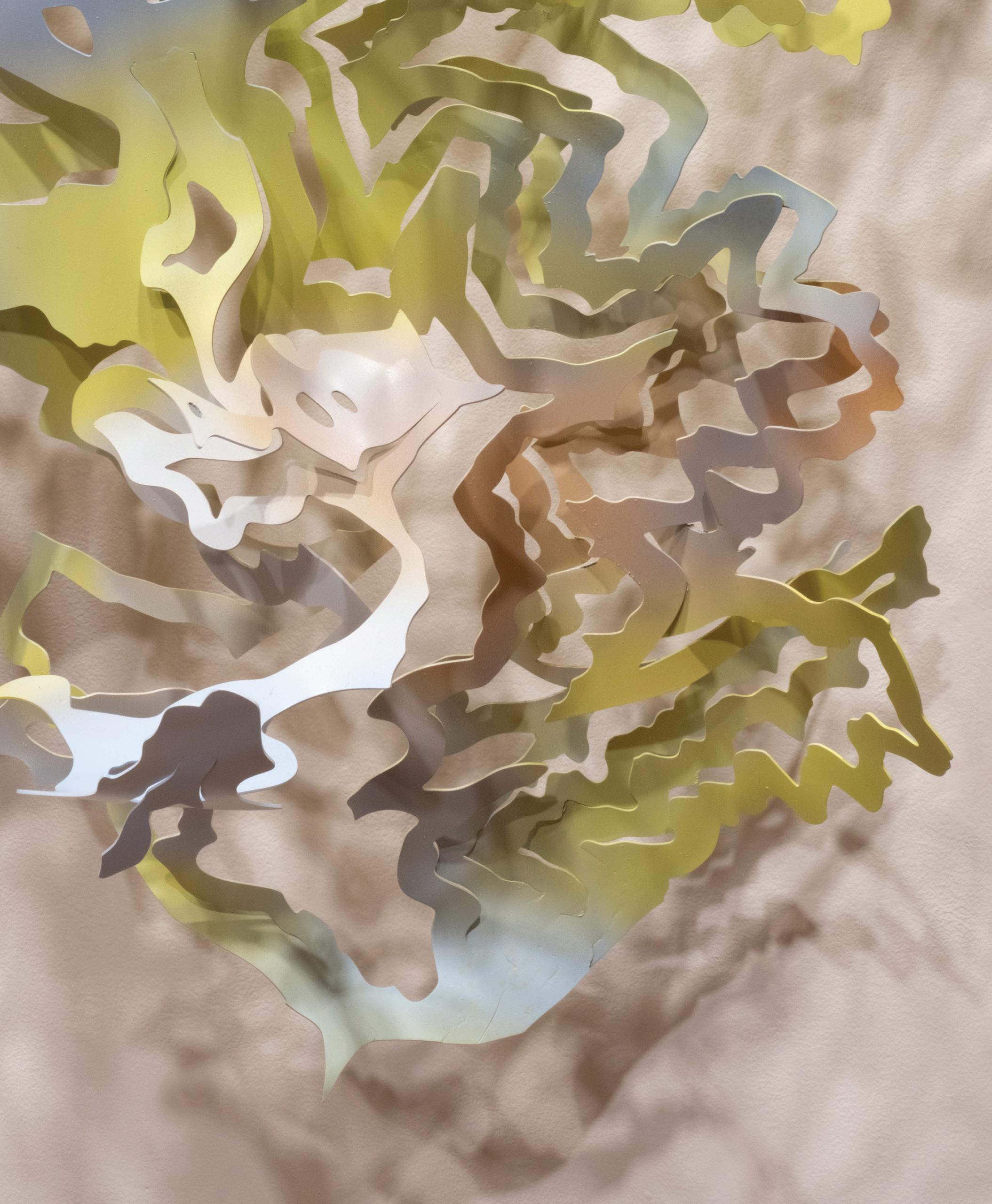

Figure 2 (Detail) Hobet Ochre, 2023 Steel, paint, string, 34 x 18 x 27 in.

14

Figure 3 Boyd Branch Reconstruction #3, 2022

Pastel, Sumi Ink, and graphite on paper, 44” x 30”

15

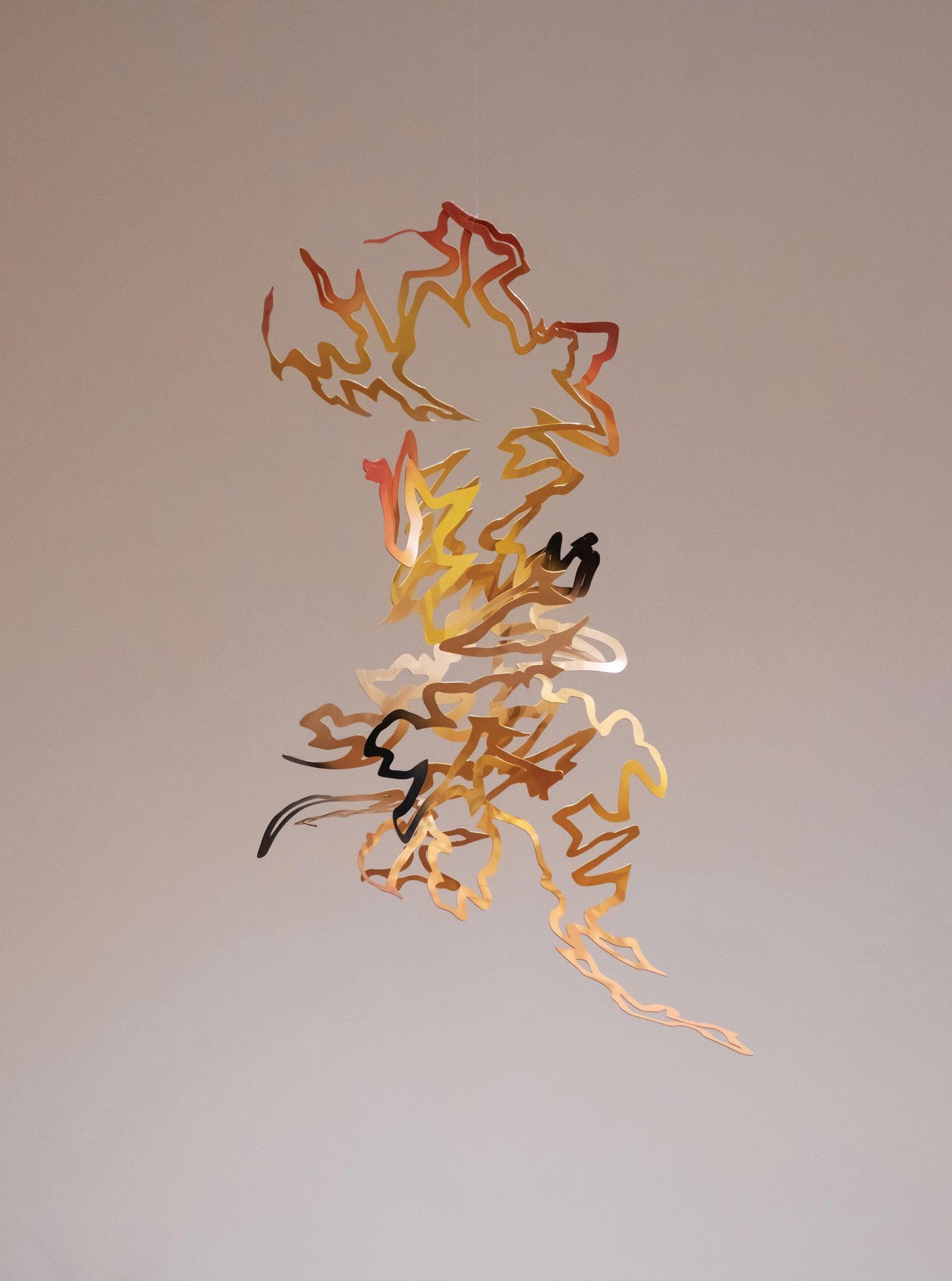

Figure 4 Boyd Branch, 2022 – 23 Steel, patina, paint, string, 60” x 27” x 21”

16

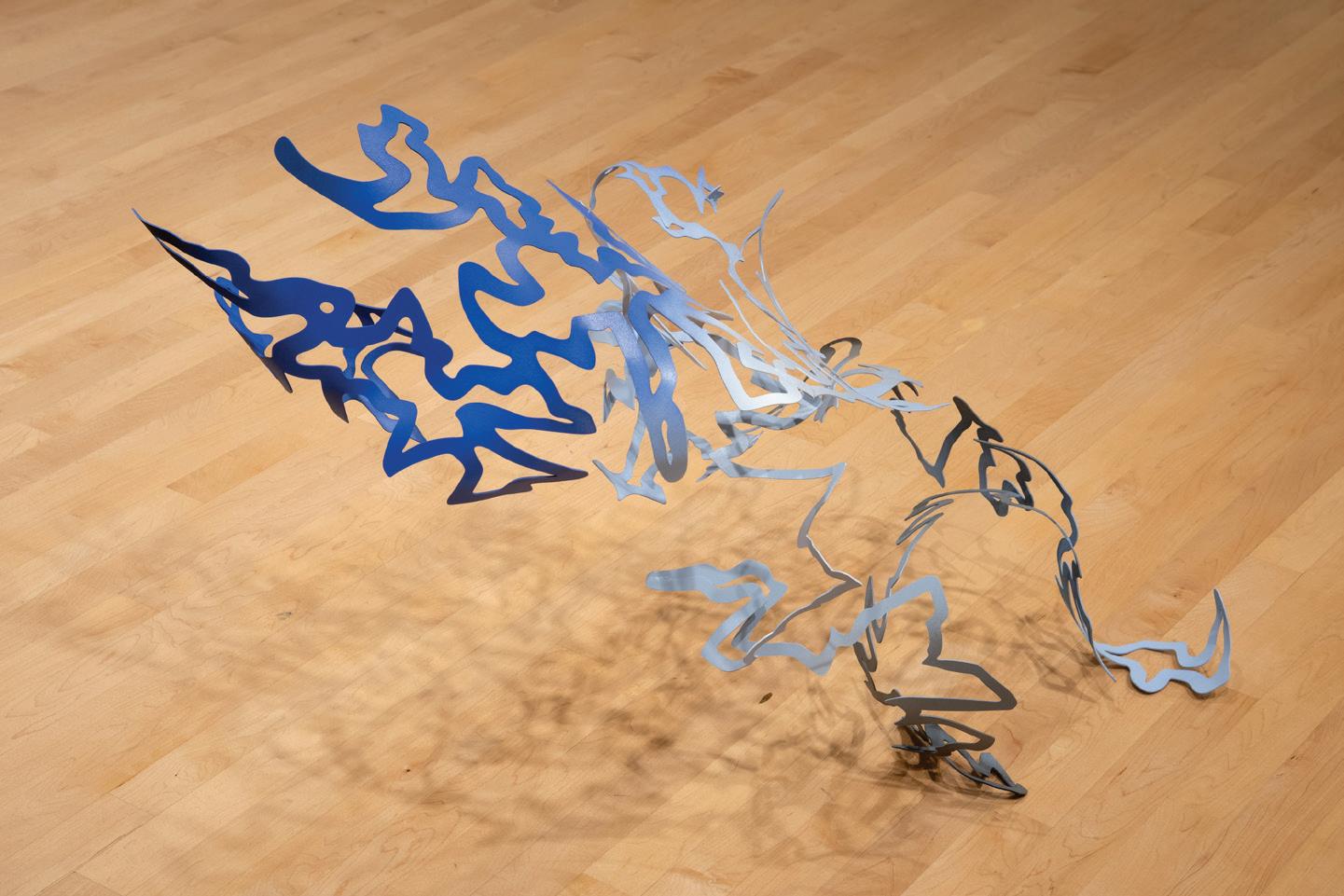

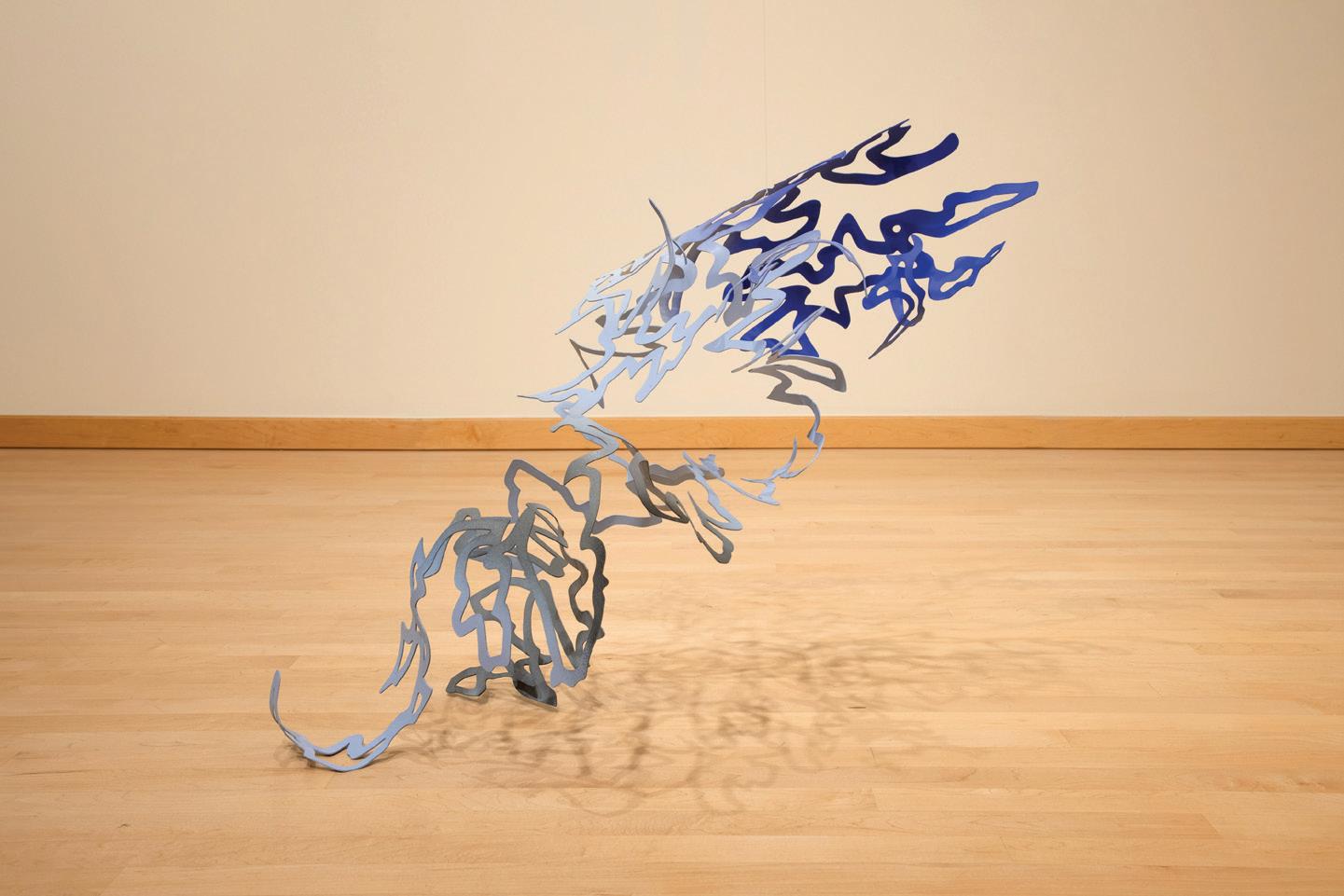

Figures 5-6 Blue Sky x Hobet 21, 2023 Steel, paint, string, 47 x 18 x 21 in.

17

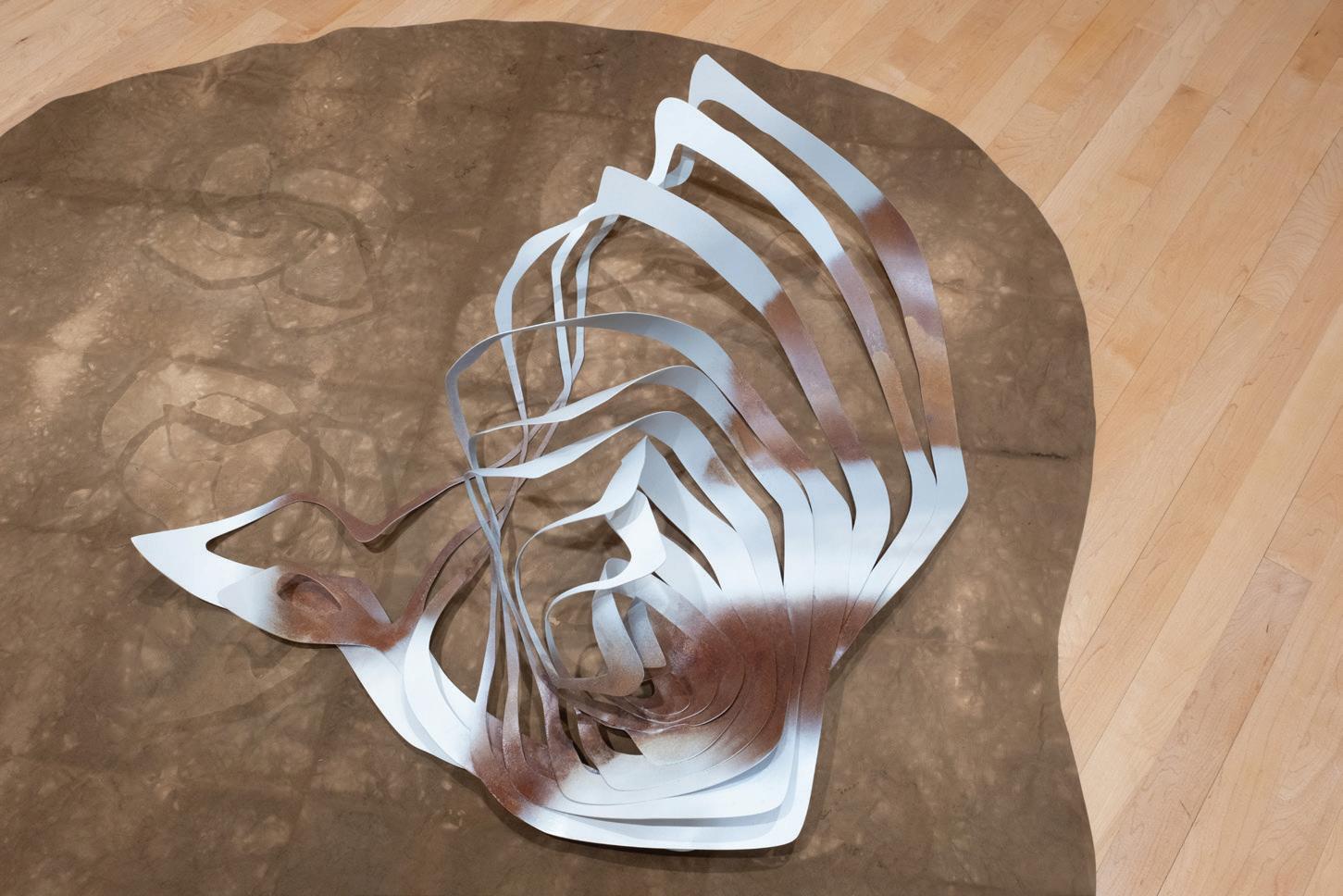

Figures 7-8 Mt. Dana + Walnut , 2023 Steel, paint, patina, canvas, walnut dye, 12 x 60 x 60 in.

18

Figure 9 Kayford Reimagined, 2023 Steel, paint, 44 x 28 x 18 in.

19

Figures 10-11 Koip Exfoliation, 2022–23 Steel, paint, masonite, and mylar, 46 x 34 x 13 in.

20

Figure 12 Boyd Branch Reconstruction #1, 2022 Pastel, Sumi Ink, and graphite on paper, 44 x 30 in.

21

Figure 13 Boyd Branch Reconstruction #2, 2022 Pastel, Sumi Ink, and graphite on paper, 44 x 30 in.

22

Figure 14 Polytemporal Pilgrim, 2023

Cotton, dyes from Purple Logwood and Orange Osage, thread, Ash dowel, 71 x 45 in.

23

Figure 15 Double-Cut , 2023 Cotton, dyes from Walnut and Orange Osage, thread, Ash dowel, 60 x 45 in.

24

Figure 16 Sky Topo Extrusion (Boyd Branch Knob, elev. 3120), 2021–2022 Cotton, indigo, Ash and White Oak, 13 feet x 28 in. x 28 in

25

Figure 17 Long Walks with Ephemeral Indigo Interventions, California and Virginia, 2022–23 Still from Video.

26

Figure 18 Nepantla Collaboration/Colaboracíon, Nepantla, 2023

Natural cotton, Manila, and synthetic ropes, strings, dyed cotton twill, yellow t-shirts, pvc hose, extension cord, copper wire, steel rod, 84 x 60 in.

27

Figure 19 (detail) Nepantla Collaboration/Colaboracíon, Nepantla, 2023

Natural cotton, Manila, and synthetic ropes, strings, dyed cotton twill, yellow t-shirts, pvc hose, extension cord, copper wire, steel rod, 84 x 60 in.

28

Figure 20 Untitled Canasta, from Nepantla Colaboracíon, 2023 Manila rope, found cotton, dyed cotton twill, found nylon rope, 9” x 12” x 18”

29

Figure 21 Nepantla Collaboration/Colaboracíon, Untitled, 2023 Natural cotton and Manila rope, dyed cotton twill, copper wire, 38 x 18 x 8 in.

30

F igures 22

Nepantla Collaboration/Colaboracíon, Raqueta Azul, 2023

Ash, cane, string, acrylic paint, 62 x 18 x 13 in;

F igures 23 and 24 (Left to Right).

Nepantla Collaboration/Colaboracíon, Raqueta Cobre, 2023

Ash, copper, 74 x 21 x 9 in;

Nepantla Collaboration/Colaboracíon, Raqueta Rosa, 2023

Ash, string, aluminum. 74 x 18 x 9 in.

31

32

Figure 25 Our House Is On Fire, 2023–24 Still from Video.

33

Figures 26-27 Floating Topographies, New Work, and Collaborations

W ith Ander Azpiri and Griselda Rosas

Staniar Gallery, Lexington, Virginia, April 29 – May 31, 2024

34

Figures 28-29 Floating Topographies, New Work, and Collaborations with Ander Azpiri and Griselda Rosas Staniar Gallery, Lexington, Virginia, April 29 – May 31, 2024

35

A rtist talk, Washington and Lee University, April 30, 2024.

Photo: Shelby Hamelman.