Cover art and Design: Isaac James

Letter from the editors

Dear Readers,

The Talon is under new management. Last year we said goodbye to Dr. and Mr. Broaddus, the advisors of The Talon and its editors for the last seventeen years. The prospect of a Broaddus-less magazine was frightening. We were a band without its conductors. Our new advisors—Mr. Amos and Mr. Wright—kept the tempo, however, and gave us the confidence to make this publication our own.

For our last few editions, the main focus has been on change—both from the pandemic, and the recovery out of it. It seems fitting that this year of adjustment for The Talon comes during an abnormally “normal” year. After so much emphasis on the individual during the pandemic—with people looking inward and focusing on themselves—we decided to turn to our community.

We started with a competition, asking students to imitate “The Red Wheelbarrow” by William Carlos Williams. Whether for its relative simplicity, or the monetary incentives, the contest drew in almost twenty submissions from fellow students. One of our favorites, “In the Hands” by Dan Chen, questions the powers that be and points to the absurdity of The Bilderbergs who run our lives.

Continuing the tradition of an annual writer-in-residence, we welcomed Ann Pancake—Pushcart Prize winner, Whiting Award recipient, and writer-in-residence at the WVU Humanities Center—to our Creative Writing Class for the winter. We began the year reading poetry, focusing at the line level, and paying attention to things often ignored (a lesson for life as much as literature).

Her short stories like “Sab” and “Dog Song” challenged us to do the same. She encouraged us to

write with a “stream-of-consciousness” to trust our subconscious freeing us from the shackles of our own minds and inspiring several pieces of prose. In “Slag,” Stuart Gallihugh gives new life to a humdrum iron-worker who—in a moment of final defiance—sticks it to The Man. Fletcher Gillespie’s “The Chosen” explores the perverted relationship between a paranoid cult leader and his “favorite wife.”

Works like “Trash Gods,” “Doolally Bughouse,” “The Watchers,” “Still in Sydney,” and host of others are the result of a year’s worth of lively imagination—created, assembled, and given as a free gift by Woodberry students who love language and art and who know its power to affect lives.

We sincerely hope you enjoy the next 180 pages, but first, a message from our sponsors:

From Mr. Amos and Mr. Wright,

First things first: “All Hail” to Karen and Rich Broaddus. Without their mentorship last year of Aiden, Conwell, Eddie, Hugh, and Isaac, this year’s magazine simply couldn’t have happened. As new sponsors, we were at first a bit daunted at the prospect of following Dr. and Mr. Broaddus. We needn’t have worried because they had prepared this year’s senior editors so well that we could simply turn them loose to create and to share their knowledge with the younger members of the staff. The Broaddus’s impact will be felt for generations of Woodberry students, as seniors teach underclassmen who become seniors who teach underclassmen…So to Dr. and Mr. Broaddus we say, “Thanks and thanks and ever thanks.”

John B. Amos Charlie Wright

POETRY

PHOTOGRAPHY

long

time to be

gone

long time to be gone long time to be gone long time to be gone

Lovers after René Magritte | Ata Twining | charcoal on paper |12 x 18 in.

Lovers after René Magritte | Ata Twining | charcoal on paper |12 x 18 in.

Dear

Mary, my sweet Mary

I never kept you long had a short time to stay here and a long time to be gone

Mary, my sweet Mary

I never kept you long Had a short time to stay here And a long time to be gone

by Stuart GallihughI’d rather die in some deep valley

Where the sun never shines

I’d rather die in some deep valley where the sun never shines than for you to be another man’s darling and know you can’t be mine

Than for you to be another man’s darling And know you can’t be mine

Mary, my little Mary

What made you say good-bye

I never tried to stop you I just sat down and cried

With you never beside me

And without your sweet song You caused me constant trouble

What you caused me too, too long

Mary, My sweet Mary

Mary, my little Mary what made you say good-bye I never tried to stop you I just sat down and cried with you never beside me and without your sweet song you caused me constant trouble what you caused me too, too long Mary, My sweet Mary what made you leave me so what more did that man have that lured you to pack and go farewell my little Mary now it’s time for you to cry I’m headed for that valley i'll watch you from way up high

What made you leave me so

What more did that man have

That lured you to pack and go

Farewell my little Mary

Now it’s time for you to cry

I’m headed for that valley

I'll watch you from way up high

Mary, long time to be gone: a song

slag

by stuart gallihughWillam MacKay’s morning was uneventful. His day started with punchcard accuracy like all the others.

Up at 7:15, he drank the glass of water on his nightstand, cracked his toes, and washed his face in the dingy blue sink inside his harshly lit bathroom. There was a faint plick plick plick from a leaky pipe. A CHOCK

FULL O’ NUTS can was placed underneath the drip. For all the years it had spent under the

sink in the MacKay bathroom, it might have grown there and sprouted roots.

“I’ll have to fix that,” he thought, while inspecting a stubbly and weathered face in his mirror. The plumbing groaned in protest as he shaved his face. No lather, he couldn’t afford it.

His wife Sarah’s voice sounded sharply

from downstairs like a bullhorn.

“WM! It’s getting cold! Do I have to drag you down here myself?”

“No.” he reassured, “I’ll be down.”

He picked up a tarnished pocketwatch off his bedside table. William paused and ran a work-tough finger over the cracked bezel. It had been

his father’s before he died on shift at Bethlehem Steel. He had been too young then to remember him anyway. The spidery silver hands read 7:35.

He threw a mothy bedrobe around his shoulders and went downstairs. On the table was an all-too runny egg, a piece of toast blackened on a single side, and oily coffee. His wife stared over the edge of yesterday’s newspaper like a vulture regarding carrion.

“You’d better eat it, that’s 20 cents worth.”

William pulled out, then sat in a hard chair. As each bite went down his gullet, it turned to sand. Taking the watch from his pocket, he flicked it open with his left thumb. 7:53.

He was a number at Bethlehem Steel. A timeslot, a drone, a husk that was in charge of skimming slag. He had been for the past 32 years. God, thinking of it, even silently, felt like capital punishment. Every day it felt like life had lost a little more color, and food a little more flavor. It could be the ash, but it wasn’t, it was something inside him. His father had worked himself to the grave at Bethlehem Steel. What was he going to do?

William’s gray eyes stared at his bone-white plate,

and the watch beside it. The watch stared back. 8:13.

He snapped up and cried, “Oh Jesus Sarah! I’ll be late!”

Sarah said nothing. Racing upstairs he fastened a pair of greasy overalls over his gaunt frame. Floorboards creaked and the stairs groaned as he paraded down. Grabbing his hat and coat from a chair, and lunch from the kitchen, he flew out the door. The rattly metal lunchbox contained a lard sandwich and some unshelled peanuts. He saddled his bike and pedaled twelve miles in the

He was a number at Bethlehem Steel. A timeslot, a drone, a husk that was in charge of skimming slag.

bitter New England morning.

He arrived in front of Bethlehem Steel with frozen eyebrows. If anyone paid any attention to him, they would have thought he looked like a tired racehorse with steam shooting from its nose. Unsticking his hands from the bare metal grips of his bicycle, he loped towards the iron gate of Bethlehem Steel. The soulless sooty windows and greasy brick made his stomach churn. Twin smokestacks reached into a slate sky like the arms of God. He took a deep breath, and as the ‘9 whistle

blew, stepped into a familiar hell.

The roar of the blast furnaces melted the ice from his brow and the

deep red glow of iron glazed his eyes. Above the sounds of furnaces and machinery were the collective groans of a hundred men.

He reported to his foreman and punched a frayed timecard. Clik-pinng. He stared at the little hole the punch-clock made by 9:09. Donning a pair of worn leather gloves he went to the spot where he had stood for the past 32 years. He stripped down to his

overalls, and pulled his shirt off. He felt like frozen meat slung into a ripping hot skillet. The workers near the furnace were almost down to their underwear. Beads of blood and sweat spat out a cadence as they hit the molten steel. The lucky ones had saved up enough and bought leather aprons to shield themselves from the heat, but there were no such luxuries for William MacKay.

His station was perched only feet above Crucible №4, and his job was to lean over a thin railing and skim slag off the top with an iron rake. If he leaned too far he would end up like the last man. Poor soul. He would perform this task until lunch,

He felt like frozen meat slung into a ripping hot skillet.... Beads of blood and sweat spat out a cadence.

hellfire in his mind and swirling below.

Temporary salvation came as the ‘12 whistle shrieked like a kicked rooster. He ate his tasteless lard sandwich in silence and stared up through a high window, where outside there was marginally cleaner

air. He coughed harshly, and small drops of crimson blood hit the white bread of his sandwich. Bethlehem Steel was killing William, just like his father. Only his father had gone quick, crushed by a rogue beam. Snap. William thought. Just like

that. He tugged his father’s watch from his vest pocket and stared into its ivory face, the purest thing in Bethlehem Steel. The little silver hands marched forward. One minute, one hour, one shift, one day, one week, one month, one goddamned year

at a time. But there was no other way. There was a table that needed food, and a wife that needed support, even if she was a vulture.

As William MacKay wiped the blood from a corner of his lip, a dirty tear threatened to roll down his cheek. And then his face hardened, and his eyes became flecks of granite. He rose, checked his watch, and gently closed his lunchbox.

“Today is the day.” he said aloud. It was 12:19. The other workers looked at him with wide sunken eyes.

He said again,

firmly, “Today is the day. Slaves of Bethlehem Steel, today is the day I kill that sonofabitch in his office.”

So without a backward glance he picked up a piece of pipe and went to meet the faceless tycoon of Bethlehem Steel.

He bulled through doors and cleanshaven secretaries, making his way to the corporate wing of Bethlehem Steel. He dimly heard protests through his wrath, but they couldn’t stop him. His boots left dirty prints on the linoleum, and his hands soiled the doorknobs. At the

end of his odyssey he came to the door. In his pocket, the watch hands had slid over 12:30.

French polished and gold script around the doorframe read J. BINGHAM, OWNER.

He knocked softly and heard a growl from inside.

“I’m busy dammit! I swear to God, Martha, if you tell me about those workers again I’ll dock your pay!”

With this William kicked the door open , splintering the carved mahogany with a fury only a fatherless son could produce. He saw a thin man behind a desk, with a long, angular face and cold eyes. He stared at the man in silence, his lungs rattling.

“Wh-who are you?” squeaked the man.

As William MacKay wiped the blood from a corner of his lip, a dirty tear threatened to roll down his cheek.

William placed his fathers watch on the oaken desk and spun it around so the man could read it. William leaned in close and spat,

thick pipe like it was a feather and swung. If he had worn a different uniform, it would have been an MLB record. J. Bingham,

in place through their patent shoes. He sneered at them bitterly.

“It’s your time now, Mr. Bingham.”

J. Bingham, Owner’s eyes slowly settled on the lead pipe in his worker’s hand. William stood stiff for a minute, watching the man squirm and fret in his chair. Then William roared, each word like a hammer strike.

“I AM NUMBER 384, SIR! MY FATHER WAS NUMBER 96! AND I’VE BEEN A SLAVE OF THIS GODDAMNED COMPANY FOR 32 YEARS!”

He raised the

Owner, made not a sound as the anger of William MacKay connected with the side of his temple. He toppled like a blighted tree. In the reflection of his dead eyes, the watch read 12:33.

As the pipe fell from William’s hand with a dull thunk, he turned to the crowd of lackeys behind him. They had seen it all. He stared at their clean faces and combed hair savagely. They were frozen, rooted

Stepping across the lifeless body of J. Bingham, Owner, he sat in the chair. William stared at the watch, its gold chain flowing over the edge of the desk. He picked it up and clutched it to his heart. He laughed, a full, deep laugh. He noticed the lackeys still in the doorway.

“Now what?” he said to them. He chuckled.

“Now what?” he screamed.

The lackeys stared at William MacKay.

He just laughed.

They were frozen, rooted in place through their patent leather shoes. He sneered at them bitterly.

coastal chuckwagon gumbo

by isaac james

ocean spray salts the sizzling iron pot. we’ve been here for hours, my papa and his fire.

corn, sliced by scarred hands and flung into stew, simmers in mushrooms and cod liver oil. bone marrow dissipates inside the chuckwagon.

my sister runs barefoot across the beach with a bucket of fresh shucked peas and lays them at his feet.

in the marram grass, a battered woman calls my sister back across the sand. she returns, blushing, with tomatoes in her hands.

we sit, bent and gray against the drooping sun, tongue-dried, joint-creaking ladle-dippers, our fingers so cold we can’t feel our spoons.

bone marrow calms our quivering stomachs. corn kernels crunch against our soft tongues. papa grins with broken teeth and slurps

the cast iron, sea-salt seasoned, coastal chuckwagon gumbo in the firelight and sighs.

Hap py in Hell Happy in

by darren mccantsYellow and brown leaves

Float over corn and soybeans.

Pines sway

In the crisp, cold air.

A house, Wrapped in vines, Rots in mold.

The door

Dangles from hinges. The floor

Creaks below a sunken ceiling.

A child, Rolls his red fire truck with laughter. His emerald eyes shimmer. He has what he needs.

The once upward reaching branches now droop, pulled down from days of rain water. Damp leaves cover the coffee colored dirt in a tan mosaic. The mud squelches underneath my thick rubber heel.

I glance back at my prints— atop the soil glints an opaque bead. As I bend down, the small pearl reveals itself as the shy lip of a cup. I pull.

A bone white jar emerges, caked in earth that clumps like small June Bugs. Residue of a copper lid stains the rim with rust. I break up the cup’s packed coffee grounds, and pour the fine powder back on the forest floor. Three lone coins. I pick each one, and let it fall, clinking back into the jar. I produce my own worn, green penny and drop it in. I settle the capsule back into the dirt, as it awaits the next heavy-footed traveler.

so what happened was...

a telephone transcript by william green

Sowhat happened was my father sent me to New York for my twenty-first birthday. It is a tradition in Nigerian royalty, you see. The trip started out great, but a few days in I was mugged by some of you American hooligans. Now I am stuck in America when my father needs me most.

Oh, they sell weapons. No, no I am sure Amazon sells the best weapons for fighting Somali pirates.

Why? My nation is currently being attacked by Al Qaeda and I need to be there to lead the army, but I am stuck in Mia… New York. That is why I need you to send me ten $100 Amazon gift

cards. I promise that when I get home, I will make you very rich. y sell weapons. No, no I am sure Amazon sells the best weapons for fighting Somali pirates. No, ma’am, Chili’s gift cards will not work. I need the Amazon gift cards to buy weapons for my men and so we can retake the throne.

y sell weapons. No, no I a

What is a Bass Pro?

y sell weapons. No, no I a

y sell weapons. No, no I a

y sell weapons. No, no I a

Oh, they sell weapons. No, no I am sure Amazon sells the best weapons for fighting Somali pirates. sell weapons. No, no I am sure

Amazon sells the best weapons

What? No, I am quite sure I said Somali pirates are invading my country. sell weapons. No, no I am sure Amazon sells the best weapons for fighting Somali pirates. Yes, ma’am, they wish to take our gold, and you can have some of that gold if you just help me return and take back my country. No, I do not wish to speak to your husband…

sell weapons. No, no I am sure Amazon sells the best for fighting Somali pirates.

Hello, sir, I am a Nigerian prince who is trapped in America while Al Qaeda invades my country.

sell weapons. No, no I am sure Amazon sells the best weapons for fighting Somali pirates. No, the Somali pirates control your American news. You wouldn’t have heard of it.

sell weapons. No, no I am sure Amazon sells the beons for fighting Somali pirates. Nigeria? It’s in uhhh… Africa. sell weapons. No, no I am Amazon sells the best weapons for fighting Somali pirates.

Oh, you’ve always wanted to go to Africa?

zon sells the best weapons for fighting Somali pirates. Your friends, too?

sell weapons. No, no I am sure Amazon sells the best wefor fighting Somali pirat

No, no. I assure you it is much too dangerous for you Americans. sell weapons. No, no I am sure Amazon sells the best for fighting Soma

You are a Hell’s Angel? What is a… It does not matter, what I really need is ten $100 Amazon gift cards so I can save my country and then make you and your wife very rich.

sell weapons. No, no I am sure Amazonthe best for fighting Soma

No, not Chili’s, Amazon. sells the best for fighting Soma

Yes, yes, you will be very rich, I assure you.

sell weapons. No, no I am sure Amazon sells the best weapons for fighting Somali pirates. You will send the money? Thank you very much. The whole country of Nigeria is indebted to you.

TheChosen

by fletcher gillespie

by fletcher gillespie

Doors slammed open and closed. Then, starting quietly, truck tires ground against the gravel road that led to the compound. The crunching got louder and Sarah thought she could hear other vehicles. Was that whirrrrrrrrr a helicopter propellor? Someone outside began speaking in muffled words, crumpled by a megaphone. Sarah could make out the words, but she ignored them. What was the point in listening to lies? Have mercy on them, she thought. They know not what they do.

There was a time when Sarah wouldn’t have prayed for anybody. Before she met Luke, her life was as average as could be. She was going to get her degree, find a job she liked, and settle down. She wasn’t sure when it went wrong. A bag of coke. Academic probation. Telephoned screaming matches

with Dad. That eviction letter. She still had nightmares about where she’d be if she had never met Luke and been accepted into this community.

She swallowed, trying to give her voice an unconcerned cadence. “Dontcha think it’s almost cute?” she asked Mark, who sat in shadow at the other end of the room. “They’re going to war with God and they still think they’re the good ones. They’ve got so turned around they don’t know which way’s up. Cult? Hostages? It's like they’re blind.”

Mark grunted, studying the gun in his lap intently. Sarah could see a bead of sweat on his cheek, illuminated by lanternlight. Or was it a tear?

“Y’know, you don’t need to stay in here just to protect me.

I’m fine. I bet you’d be more useful downstairs anyway!” She meant it. Despite the hordes of

federal agents coming down on the compound, Sarah felt no fear in her heart. It was as if she were floating in a pool, her ears underwater. Everything happens as God wills. It is known.

“I’m staying with you,” Mark mumbled, refusing to look away from the gun. “Luke says I have to keep you in here.”

Sarah understood. Things were getting dangerous, and after all, she did feel safe in the study. She sat on a carpeted floor, her back against a wide bookshelf lit only by a lantern sitting on a desk. Luke’s guitar leaned against the bookshelf beside her. She smiled, remembering the countless songs he’d sung to her in the summer twilight. On the bookshelf was a mix of classic literature and Luke’s own writing. There were many copies of his published work, from before he learned his true name: apologetics

Sarah couldn’t see the attack. She could hear it, though, through the thin walls of Luke’s study. Voices barked orders at each other. Boots hammered the wooden staircase outside the door.

accredited to a “William Tide.”

Then there was the writing from after his awakening, collected in dozens of nondescript diaries and folders: notes detailing the commandments, decrees, and prophecies God had delivered through Luke. Few of his followers made a habit of reading

wrong.” The silhouette of his head stayed tilted towards the ground.

“We–are–trapped,” he choked out. “Sooner or later— the Feds are going to break down the front door, and we’re done. It's over.” Mark’s tone was as dark as ink.

“Don’t say that!” Sarah tried to inject some energy into her voice. “Luke has a plan.”

or writing, so the “communal study” was essentially Luke’s private office; it was also Sarah’s hiding place if an attack ever came.

From the shadows, Mark muttered.

“Hmm?” she looked up at him.

“I said I can’t do this.” His face was only half visible, but she could see he was shaking. “It's all bullshit. We’re in too deep.” Terror filled his voice. Sarah opened her mouth, concerned, but didn’t know what to say. Was Mark, one of Luke’s closest followers, really going through a crisis of faith?

“It's okay,” she said softly. “We haven’t done anything

“Don’t say that!” Sarah tried to inject some energy into her voice. “Luke has a plan.” Mark snorted.

“Does he?” For the first time in hours, he looked up at her. She could see the faint lanternlight in his eyes. “He hasn’t given me a straight answer in days. If he had a plan, you’d think he’d at least run it by me and the other generals, right?” Mark’s lips were curled upward into a cold, empty smile that turned Sarah’s stomach.

“Luke is one of the smartest men I’ve ever met. I’m sure he prepared for this.”

“I’m sure he has. But for some reason, he won’t let any of us know what he’s thinking.

I have a feeling he’s about to leave us out to dry. And some of the things he’s said… Sarah, I’m worried you’re going to get hurt.” His voice hardened.

“Mark, what do you mean? Luke loves us. Please stop worrying.” Sarah knew how limp the words sounded. If Mark’s faith was shaken, maybe there really was something to worry about. Mark clambered to his feet. His lanky arms reached towards her, and she felt cold metal press into her palms. She looked down to see a closed switchblade between them. She flinched and jerked her hand backwards, letting the knife thud onto the carpet. She felt goosebumps on her skin where it had touched.

“What are you doing?” she snapped. It wasn’t the first knife she had touched, but it was the first weapon. Weapons are forbidden. It is known. Except for all the guns that had been appearing in the mens’ hands over the last few days…

“Look,” Mark started, his voice edged with anxiety.

“I don’t think you can trust everyone in here to shield you. You need a way to protect

Moon Night | Scott Carmichael | Woodberry Forest, Virginia | digital photography

yourself.” As Mark talked, Sarah slowly circled him, getting closer to the door.

“I want to be with Luke if something goes wrong,” Sarah told him, eying the gun in his hand. “Wait until he hears about your heresy.”

“No, Sarah, don’t tell him. Please, stay in here,” Mark begged, but it was too late. Sarah opened the door, and blinding light shot into the study, making her squint. Out in the hallway, the sun shone through large windows, and lanterns hung from the ceiling. The walls were painted white, and a tan rug ran the hall’s length.

“David!” Sarah called out. David stood at the far end of the empty hall. “Where’s Luke? I need to see him.” She jogged down the hall, away from Mark’s lies and knives.

“He’s in the dining room. Didn’t he want you to stay up here?” Sarah ignored the question and blew past David. His soft chin trembled with confusion. She turned a corner and began running down the stairs, taking three at a time. Mark obviously wasn’t feeling well, but he was right about

one thing: Even aside from the federal siege, something felt wrong. Sarah felt the pit of anxiety in her stomach grow with every passing second. If she could just see Luke, hold his hand, everything would be better.

few years younger to whom he delegated his responsibilities. If Luke was the president of The Chosen, they were his cabinet. Mark was one, which made his words upstairs all the more shocking to Sarah.

The dining room was the largest room in the homestead, with five tables long enough to seat all of The Chosen together.

She reached the bottom of the stairs and made way for the dining room, weaving through the armed men hurrying in every direction. Luke’s commandment echoed in her head, unbidden. Weapons are forbidden. It is known. Sarah silently thanked God she had yet to hear gunshots.

The dining room was the largest room in the homestead, with five tables long enough to seat all of The Chosen together. Four of them ran parallel to each other, and at the far end, a fifth stood on a perpendicular dais. That was where Luke took his meals, along with his wives and “generals,” his inner circle. They were all men around his age or a

There Luke sat with four of them, all hunched around a cell phone. The other men looked concerned, but Luke’s face was marred by a wicked grin. As Sarah walked between the lower tables, she began to make out what Luke was saying.

“That’s right, sir. Seven hostages. Yes, it is.” His voice, so unfamiliar, froze her legs. This sounded nothing like his singing that she loved so much. This voice rang of cold steel. “Seven women, that’s right. Molly Palmer, Caroline Smith…”

Those were the names of his other wives. Luke was listing his wives. Sarah felt sick. She stood in the middle of the dining room, feeling so distant from the dais right in front of

just threatened to murder her and was acting as if nothing happened. Without warning, she wept. She tried to hold back her sobs, but it was no use.

Her blood ran cold. Who was the man standing in front of her? Where was the Luke who had worked the garden with her?

her. “... Sarah McMillan,” Luke continued, winking at Sarah over his sunglasses. After finishing the list he continued. “You agress on us in any way, and heads will roll. Understand?” One of the generals silently threw up frustrated arms. Another’s unshaved jaw dropped with shock.

Luke hung up the phone, slammed it on the table and started cackling. “Can you believe those assholes actually bought that? I swear I could make them believe anything!” He was met with cold glares around the table.

“What the hell are you doing?” one general nearly screamed. “Are you trying to land us all life sentences?”

“Don’t worry, Daniel, I’m just buying a little time.” His voice had returned to the buttery signature that was much more familiar to Sarah, who still stood transfixed in the middle of the room. Her own husband had

In seconds, Luke had bounded over the table and was holding her to his chest. “Hey, hey, hey,” he said softly. “I’m here.” Not knowing what to do, Sarah threw her arms back around him. He leaned down to her ear.

the phone with the ATF agents.

“Isaac, are my other wives still in the back room?” He was talking to his generals again. “Go visit their guards. Make sure they understand my orders.” The command dripped with a malice Sarah had never heard from Luke before. She unwrapped her arms and stumbled back from his wiry frame, trembling. He continued delivering orders, his back already turned. “Samson, tell your men to man the windows.”

“Are you sure? I’d be putting them in the line of fire. I don’t want to spill unnecessary blood,” Samson asked from the dais.

“What the hell are you doing?” one general nearly screamed. “Are you trying to land us all life sentences?”

“I’m really sorry you had to hear that,” he was almost whispering. “You understand what I’m pulling, right? If they think we hold hostages, they’ll hesitate to open fire. This’ll give me just enough time.” Sarah was melting into his arms now, but his voice was already returning to that icy cadence he had used on

“We’re at war, general. People die. Carry out my orders.” Sarah couldn’t detect a shred of sympathy in Luke’s voice. Her blood ran cold. Who was the man standing in front of her? Where was the Luke who had worked the garden with her, who would lose himself in books? Sarah thought of those

between her ribs diminished. Luke leaned forward and kissed her cheek.

The shadowy scowls the generals always wore as they walked back up the stairs. The increasingly late nights they’d spent down there once rumors of a raid had started to spread.

closed-door basement meetings. How Luke would never let her sit in, though she was supposedly his favorite wife. The shadowy scowls the generals always wore as they walked back up the stairs. The increasingly late nights they’d spent down there once rumors of a raid had started to spread. The awkward silence Luke would give her when she asked what they discussed. How did he sound down in the dark?

“Sarah, is Mark okay? Why did you come down here?” Luke’s voice slid back into warmth as he turned towards her. She hesitated.

“Mark is fine,” she lied. “I…” she trailed off. “I just wanted to see you.” Finally, Luke’s face broke into a smile she recognized. It was a look-at-thiskitten-I-found smile, a listen-tothis-song-I-just-learned smile. For a moment, the pit of anxiety

“I love you, sweetie, but you shouldn’t be here right now. It's safer for you up with Mark.” She nodded. She didn’t want to go back upstairs but had no choice. As she walked out of the dining hall, all traces of warmth vanished. She replayed everything she had just heard. Mark was wrong. wasn’t he? The men continued to run chaotically, shouting at each other and loading guns, but Sarah felt far away. She was alone. She set her shoulders back and looked towards the staircase. Maybe she did need to protect herself. She walked back up the stairs, determined. She’d left a switchblade up there. It couldn’t hurt to grab it. Just in case.

Saturday: 1:05 A.M. AEST

Sunday: 3:23 P.M. AEST

Michael slung his arm around Peter, coaxing him to take a line of bass

“Just one Pete. You’ve his childhood one.”

Michael slung his arm around Peter, coaxing him to take a line of cocaine. The bass thumped, forcing him to lean in. “Just one line, Pete. You’ve got to celebrate these things.” Peter faced his childhood friend, business partner, and saw the devious look. “Just one.”

Reluctantly, Peter grabbed the hundred dollar bill from the table, stuck one end into his nostril and jerked back as the dopamine rocketed up his nose. Michael howled and snagged two cocktails from the passing waitress’s tray,

Reluctantly, Peter bill from stuck one end into his nostril and nose. Michael cocktails from million-dollar deals!”

clinked their glasses, downed ordered four

“To friendship, to Sydney, and to million-dollar deals!” They clinked their glasses, downed their drinks and ordered four more.

Peter woke up to a spinning room, stark white. He reached for

Peter woke up to a spinning room, stark white. He reached for his phone but found a scrawled post-it note stuck on top…

Crazy night. Can’t believe you did that, least she was hot. Meet at Opera at 7pm. I’ll be late, meeting clients.

clients.

–Michael

Peter struggled to remember. His head sank deeper into the pillow. He probed the bed and raised a smooth object with a sharp needle into view. A pearl earring. Peter’s misery consumed him. He called Michael repeatedly but the phone went to voicemail. Michael

–Michael struggled to His head earring. him. He called Michael repeatedly but the phone went to voicemail. Michael

will know, just get up. He forced himself out of bed, staggered into the shower and ordered an Uber to the Opera House.

know, just bed, staggered the shower and ordered an Uber the Opera House.

Sunday: 7:05 P.M. AEST

Sunday: 7:05 P.M. AEST

Reaching into his cashmere coat, he retrieved a handkerchief to wipe a tear. As Anna Netrebko glimmered under the spotlight, her wide melodic leaps echoed in Peter’s ears. He left his center box seat for the bathroom. He was alone, washing his hands, avoiding the reflection of his frail frame. He had promised Sarah he’d be careful around Michael, but it was all bullshit.

glimmered under the spotlight, Peter’s ears. He left his center box seat for the bathroom. He was alone, washing his hands, avoiding frame. around Michael, all bullshit.

The water became warm, then scalding. He yanked his hands

away, almost striking himself in the face. The mirror caught his gaze and refused to let go. He brushed his arm under his nose expecting white particles, but there were none.

He remembered his zipper lowering and a stranger’s fiery lips pucker, “Peter, relax.” The regret rushed back and haunted him. Looking into the glass, he saw a pale, naked figure–a foggy imitation of the man he used to be.

Netrebko reached the quintessential part of her “Odna Lyubov.” Peter heard her through the bathroom door…

Eye to eye

Hand in hand

Whoever loves, we keep

One love

In two destinies.

A tear, then two. Peter’s knees melted. He cocooned himself in memories of Sarah. The time she’d asked to share a cab in college. The time Peter’s hands had trembled from getting down on one knee so that the ring fell at her feet. The time when Eric was born, their driver taking a wrong turn and Sarah’s agony that brought about the widest smile she ever shared.

Netrebko’s voice came to a

soft end. Peter shook his head trying to forget. He pushed against the flooring, struggling to his feet. The mirror stared back at him, and he burst through the door and out into the thunderous applause. He dipped his trembling hand into his pocket, texted

Sarah stood there, beautiful and gentle as the day they had met, wearing a white robe and holding Eric’s head against her waist. Peter looked distraught and weary. Her smile turned to concern. His eyes welled as he tried to utter even a single syllable. Sarah saw him

The regret rushed back and haunted him. Looking into the glass, he saw a pale, naked figure–a foggy imitation of the man he used to be.

Michael, “Will be late as well” and called his pilot to meet him at the airport.

Monday: 9:24 P.M. EST

The porter held the door, “Welcome back Peter. Sarah must be very excited to see you.”

Peter attempted a smile, “Thanks, it feels good to be home.”

When he walked past, he felt a sharp ache in his chest. In the elevator, he scrambled over how to confess.

Peter, grim and deflated, faced the pearl door. He knocked. He heard shuffling inside and Eric’s excitement, “Daddy’s home, Daddy’s home!” A ruffling of the doorknob, a switch of the lock.

standing there, like a cat in the pouring rain.

Peter's voice shook as he finally mustered…

“I’m s-so sorry.” choking on his regret.

As she embraced him, her eyes began to swell. She rested her head against his chest and whispered...

“Peter…I know…Michael came and told me.”

Peter appeared on the verge of collapse, “What? What are you talking about? He’s still in Sydney…”

She lowered her head. With deliberate care, she interlaced her fingers with his and mumbled, “... No … he left this morning … I hope you can forgive me, too.”

D lally

Bughouse

Doolally Bughouse don’t bother givin’ me no ring to wear, but Clive’s gone doolally and I’ve gone bughouse, so it’s gonna be just as sure as apples on the kissing tree

Solongasthesunstillshines

Sunstillshines

Sunstillshinesonme.

She took me to town, little girl in a gown, and told me I’d gone doolally. Sally sold me to the bughouse show slippin’, creepin’, peekin’, freakin’ and that’s the way it’s been

Isaac James

Sincethesunstillshines

Sunstillshines

Sunstillshinesonme.

In sheets of rain back of Penniless Lane

Clive Bughouse bore a ring to the wild Doolally maiden. And not a soul to tell why both of them fell

Butthesunstillshines

Thesunstillshines

Thesunstillshines

Ondoolallybughouseandme.

Irememberwhen I had the spark, when I still found the hidden stories that trash and forgotten things told. I’m not much older now, but I no longer spend my days asking how or why everything came to be. I relish when I was Huck Finn, a boy on a boat with the rest of the world to explore. I got my first boat the summer I turned twelve, but the motor stayed in the garage until I learned how to row. Boats are part of everyone’s life on The Shore, whether you are an oyster shucking waterman or just part of the summer sandbar gatherings. Mine was twelve feet long, and made of dark aluminum that cooked my bare feet every afternoon. I never chose her name but she was all I thought about. Most mornings I searched the creek from our dock for a new marsh or gut to explore.

Then I’d gather my oars and tell my mother of my newest adventure that would surely involve treasure.

As I strained my body against the oars, my boat jerked forward in a zigzag, while I dreamt of running from the boat police I thought wanted to arrest me. This was my escape from the summer heat: stories, always morphing in my mind and crafted from my adventures

on the water.

Before I was halfway across the creek, my back ached and my soft hands were red with budding blisters. I heard my father’s voice in my head, “I didn’t even know I had a back when I was your age.” The rich smell of marsh mud hit my nose as the bow scraped against the oyster shells and slid into the emerald grass between me and Blackbeard’s lost treasure. From the

As I strained my body against the oars, my boat jerked forward in a zigzag...

bow I punted the boat through curves cut by the current that fought like a turtle to drag me back to the creek. If I was lucky, I would find a green glass bottle worn by the bay or an aluminum top to a steel beer can that had rusted away years before. Each had a backstory.

A heron that took flight as I approached his perch, an old Locust tree, like the poles they used to fence in cows beside our house. Its few holes reminded me of a reed flute. Barnacles covered the bottom half, and where it met the mud something sparkled.

I pushed the bow into the grass to hold the boat in place before stripping to my boxers so mom wouldn’t be mad over dirty shorts. The water was warm from summer heat that made each night in bed sweaty and unrestful. As I slipped into the water, my toes buried into the mud, releasing bubbles that smelled of rotten eggs. I eased my arm down to uncover the glittering edge of a doubloon or diamond. My fingers grasped something smooth like a pebble. Triumphantly I stood and

I knew there was treasure in the marshes but my mother thought me a liar because she had never searched.

looked at my palm; a lumpy pearl the size of a quarter shone dark blue with specks of silver.

My mind raced and my hand trembled. I knew there was treasure in the marshes but my mother thought me a liar because she had never searched. I’d found countless rusted and broken treasures, but this pearl didn’t need cleaning to show its beauty. It must have fallen from some queen’s crown or been lost by a native chieftain years ago. Or maybe it belonged to the water itself because I’d only seen this blue when we went past the barrier islands to catch majestic sailfish.

I climbed back into the boat and drip-dried on the scalding

seat, admiring my find. Eventually I pushed the bow out of the grass and let the current drag me back to the creek. I dipped my oars into the water and bent my back against them, pushing the boat home at a crawl.

After tying up to the dock, I crossed the yard to the woods that alcoved our house. A little ways in was the hollow oak, my treasure chest. I’d chipped little pockets out of the rotten wood to store my finds. Today's pearl went beside the glass Coke bottle, turkey feather, pipestems, and fossilized oyster shell. Like a book in a library, it fit perfectly and had its own story. Turning my back, I walked to wash up before going inside.

I opened the screen door. My mother stood in the kitchen. Her stormy eyes scanned me for mud that might dirty her infernally clean house. I had washed up at the spigot, but still she frowned.

“Your left elbow, it's dirty,” she said in an almost whisper.

“Yeah, but Mom, guess what I found!”

“Wash up first, then we’ll talk,” she responded.

I scrubbed my hands and arms again with the gritty soap she kept at every sink. I don’t know why she insisted on everything being cleaned raw. She scoured past the point when everything sparkled.

I turned around from the sink and she sat, back straight, in her wicker chair with an absent frown drawing her lips down. She looked like a queen with an uprising to put down. Her hair was pulled back in a ponytail, the way it was whenever she was angry or impatient. I looked down at my clean wet hands. I realized she was waiting for me to tell my story so she could get on with what she had been doing. She had something on her mind, and I knew asking her about how the

pearl had ended up in the marsh wouldn’t entertain her. She didn’t care if it had fallen out of a crown, if it was buried by a pirate, or if a fish had swallowed it and died there.

“I found the mail key by the hose when I was coming in,” I muttered.

“Oh good, I’ve been expecting the Condé Nast magazine,” she said happily before taking the key and heading for her car.

As she left for the post office I grabbed my illustrated Don Quixote and headed back to the woods, to the dirt, my kingdom.

She had something on her mind, and I knew asking her about how the pearl had ended up in the marsh wouldn’t entertain her.

An Interview with Jack

Kenneth KimCC: 1823-89348

Are you Mr. Liston?

I did not stab her.

I asked, Are you Mr. Liston?

I did not open her.

Did you know Annie?

I did not know her.

Were you at Whitechapel?

I was not there.

How about “From Hell”?

I did not send it.

Then, who are you?

Not the right question.

Are you the Reaper?

No, I am the Ripper.

Queen of Hell | Jason Zhang | charcoal on paper | 16 x 24 in.

September, 1888.

Hansbury. 45-39854-2345

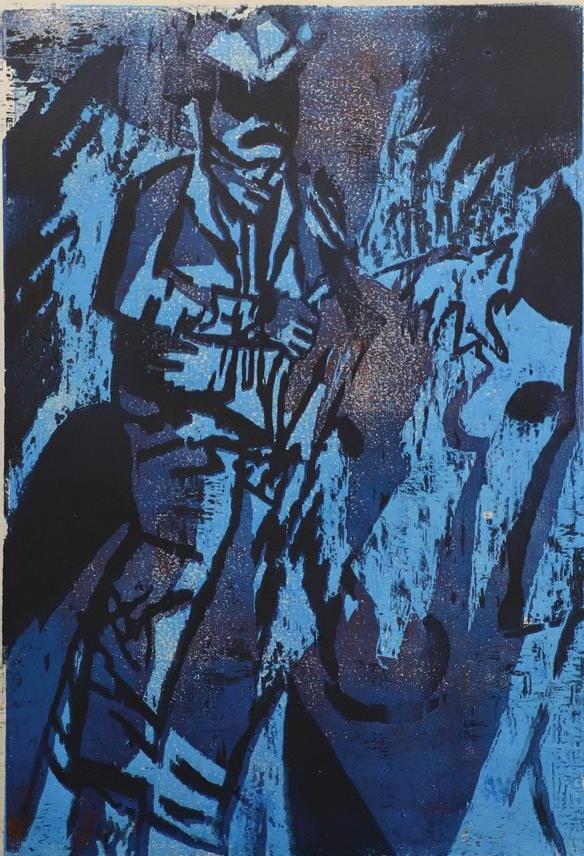

Man in Suit | William Appiah | acrylic monotype | 9 x 12 in.

Queen of Hell | Jason Zhang | charcoal on paper | 16 x 24 in.

September, 1888.

Hansbury. 45-39854-2345

Man in Suit | William Appiah | acrylic monotype | 9 x 12 in.

On the marble altar at the front of the congregation stood a royal blue urn. Like Dad, its presence cultivated respect among observers. Staring at the container, sweltering in the day’s warmth, I recalled that same late summer sun, a couple of miles from here, before I began eighth grade.

The truck tilted into the turn and slowly came to a halt. Dad swung open the driver’s door and jolted out of his seat. I buried my head in both palms, waking from a midday nap. Ahead on the road, I saw the

back of a dark leather jacket, boots the same color, and light blue jeans. I squinted while my vision slowly focused. Sprawled on his face before our truck lay a man. Stomach slowly churning and heart sinking to my spine, I sat motionless. Some yards away, the man’s motorcycle lay sprawled just like him. I was unsure how long he’d been there, but I knew the beating rays cooked the dark gravel below. We'd been on our way home from the farmer’s market. I rested on the way back because the rural Virginia roads always

rocked me to sleep. They were now the backdrop for a terrible scene. I could see Dad kneel and gently lay his hand on the man’s shoulder. I watched his mouth move with patience and his eyes dart around the road. He dug the other hand under the opposite shoulder, turning the man onto his back.

He was hefty with sagging cheeks and thin white hair. I leaned forward in my seat and peered into his face. He looked like a man I had seen at church or a distant relative I’d met last year.

My scrambled brain settled onto a single thought. He’s just like everyone else. The rolled-up windows blocked the outside noise, leaving me alone with the realization. Sitting in the front

We sat packed at the front of the chapel. I knew the lone droplet of water cascading down Mom’s face wasn’t caused by the late August heat.

meant seeing the sunrise on the way to the farmer's market. Now it also meant that nothing on the road was hidden from me. Not the man's heavy breathing, blood-splattered tank top, or struggle to sit up. His fast-moving lips revealed his growing anxiety and panic. Dad brushed his palm along the man’s shoulder and looked away every couple of seconds. For the first time, Dad got up from helping and rushed back to the truck. Is he coming for me? I tried to sit up, but the seatbelt latched onto my beating chest. Dad opened the truck door. The chattering birds and easy breeze sucked me into the scene. I was no longer watching. He snatched his phone off of the dashboard, and told me, “It sounds like he lost control on the turn. Right now he’s having trouble breathing and can’t feel his legs.” Before leaving he added, “I’m gonna call the cops. Stay here.”

I sank into the seat with a deep breath. The door shut, sending me back to the quiet pocket of the truck. I had imagined him requesting help. How I’d stay locked in place. The man, looking over and expecting

my help while Dad scrambled to do everything himself. I knew I was no help and I was glad Dad wouldn’t realize that.

The truck bed shook and Dad returned to the man with a bottle of water in one hand and phone in the other. The sun was set at the top of the sky, but he stood so the man was shaded.

one struggled to look at him. Instead, they peered at the top of the road, awaiting an ambulance.

The faint siren grew and with it the others, who’d helped, walked back to their cars. Dad, like that urn, stood unwavering, waiting for the paramedics. I had grown a sense of pride, in my father over the last hour; but

He’d always been one to pitch in. I knew him as someone who took care of the house, his truck, and myself. I hadn’t thought of him doing the same for others. Shielding his eyes from the sun and looking out across the road, I watched him become a member of the world around him. Not just the man who’d come back late from work and take me to baseball practice.

It wasn’t a busy road, but after enough time, traffic was backed up more than three cars deep. Some stayed distant from the crash, thinking it was all they could do. A couple rushed to Dad and assisted. One brought a towel for the man’s head. Each

My eyes were fixed on the road. Like at some point a curtain would close and those standing at their cars would applaud the heart-wrenching performances. The paramedics hurried past my window with great efficiency. The three of them spoke to Dad who knelt down next to the man again. Dad smiled his eye-squinting, wrinkle-revealing smile everyone knew. He lost that smile only a few seconds later as he walked back to the truck.

Dad leaned on the hood instead of waiting in the driv-

I didn’t feel as heavy-chested knowing the professionals had arrived.

Shielding his eyes from the sun and looking out across the road, I noticed his image shift into a member of the world around him.

er’s seat. The paramedics began working with the man. After some time he stopped communicating with them. They made their way to and from the ambulance. Eventually, they retrieved an oxygen mask and stretcher.

Things began to slow down. I noticed the sun lowering to the tops of the thickly leaved trees that covered the overlapping hills behind. The medics lifted the

man onto the stretcher, pulled it up to waist height, and applied the oxygen mask. They hovered over him for minutes, covering his body.

Stillness erupted into action. The paramedics began to perform CPR in front of the truck. The movements, clearly practiced, resembled a machine. Each member gave their full movement. With every push, I

saw them give their own breath in hopes to continue his. It looks violent. I thought, shocked at the sight. The three of them pounded on the man’s chest. In a split moment they stopped and rushed the stretcher to the ambulance.

The scene seemed empty now. The tossed motorcycle was motionless. There was a single stain of blood from the man's

tumble. Passing by my window, a police officer began to talk to Dad and jot down notes. When he finished, the officer tucked the notepad into his front shirt

opened the door. He dropped into the seat and exhaled. I wasn’t sure if I’d hear a word out of him. Without turning his head he asked,

pocket and turned back towards the car. I locked eyes with him and, as when Dad had come running to the car, thought that my assistance might be needed. I rolled down the window but the officer walked past. The opening let in a breeze. The air had cooled and felt calm. A rush of wind passed through between the roads, across the cars. Not long after, one paramedic returned to my Dad. His eyes were sunken and posture slouched. The message was delivered with a low tone and, reading my Dad’s face, I understood. The man was gone. Soon enough the people he had been off to see or returning to hug would notice him missing. Maybe they already had.

I sat with a heavy, hollow conscience. I said a quick prayer and looked out at Dad. He was still for a minute and then

“You alright?”

“I’ll be okay,” I mustered. I was glad he hadn’t turned his head as tears quietly spilled from my eyes.

The thought of crying brought me back to my father’s funeral. Sitting next to Mom. The tears hadn’t rushed down my face yet. They sat waiting to fall. I looked at the urn where Dad was now. I’d never looked at him the same after that day and now I couldn’t look at him at all. The first tear dropped. I wanted him to look at me this time and tell me I’d be just as strong as he was. See just how weak I was without him.

I sat with a heavy, hollow conscience. I said a quick prayer and looked out at Dad.

The Watchers

by Robbie BrownHe stepped out from the safety of the awning. The nearly frozen rain stung his arms and drenched his hair. It thundered against the corrugated metal, blocked the honks and shouts, and crept into his once dry shoes. His foggy breath filled the air, caught the passing headlights, and then dissipated.

“Taxi!” he yelled, waving his hand. “Taxi!”

“Come on. Taxi!” he tried again. If he stood there too long the watchers would notice. They knew when you were nervous. They saw your fear.

“Taxi!” he tried again. No one stopped.

The sharp wind numbed his nose and ears. He had already spent too long. Home was just a ten-minute walk. He could make it. There was no reason to worry. Everything was all right. The puddles still gave way to concrete with every step. The rain still fell.

The rain’s rooftop drum still thundered on.

He sped up slightly.

The alleys were filled with nothing but darkness and the occasional rat. There were fewer people here. Still, he could feel the watchers. He couldn’t be

It wasn’t from the cold anymore. One glance into their eyes and he would surely feel unworldly pain. He would rather be skinned alive and dipped in salt. The fate of those with manners enough to look Medusa in the eye was surely better than this. His chest was

sure that they were watching, but he couldn’t help worrying. He wasn’t safe.

He must be faster. The drumming wasn’t coming only from the rooftops now. His chest began to pitch in too.

He turned right. There he saw them. He nearly toppled into the concrete. Two watchers occupied the sidewalk before him. It was too late for him now. He knew it. He shivered fiercely.

playing almost at the rain’s pitch now. He was a lost cause. He fell to his knees.

The headlights of a passing taxi illuminated the trash bags in front of him. They were only trash bags. What cruel tricks his mind was playing on him! He stood up awkwardly. The watchers must have seen his fear. They knew he was afraid. He sped up. Now on the verge of running. Faster now. He found

He sped up slightly. The drumming wasn’t coming only from the rooftops now. His chest began to pitch in too.

himself sprinting. He knew they were behind him.

He couldn’t help but look over his shoulder. He looked again. Again. Nothing was there. What a strange sight he must be. A grown man drenched from head to toe, sprinting from no one, glancing back and forth but finding nothing, leather briefcase trailing behind him, a funny sight, a disappointing sight, a perfect target.

“Taxi!” he called again desperately. The street was empty now. The rain thundered on.

He could feel them in the shadows. They were watching him closely. They the silent midnight hunters, he the doomed rabbit. The darkness was thick and choking. His pursuers’ footsteps pounded behind him. The drummer in his chest was breaking free. An alley ahead of him glowed eerily. He wiped his eyes again. It wasn’t his mind playing tricks this time. They were waiting. This is how it always happened. He couldn’t be imagining this time. He jumped. A pot shattered behind him. The trash cans ahead toppled. A shadowy figure

stepped out.

“Who’s there?” he called out. He already knew.

A shadow dropped from the roof across the street. He had no hope. His own front door bolted tightly wouldn’t save him now.

A drab yellow taxi stopped at his left. If he had a chance, this was it. He leapt desperately for the handle and managed to get the door open. The burnt rubbery stench suggested that the hooded driver had missed his last century of inspections, but that did not matter now. The door slammed shut behind him. He was safe.

The driver pulled away from the curb. He could make out the watchers’ silhouettes through the chalky brown glass. They couldn’t get him now. He was safe. All they could do was watch. They were just watchers.

They say the watchers always got you. Not this time. He was the exception. He was safe.

He took a deep breath and turned to thank the kind driver.

The watcher’s burning eyes bore into his.

Clara Louise

by jordan mcconnellHesat down at the bow of the Clara Louise, named after his late mother. The boat was a link to his mother. It reminded him of her.

He liked thinking of all the daily laughs. Days at the beach and runs to the grocery store, where he would sneak in a bag of candy or some ice cream and she’d wink at him.

He leaned forward and felt the water rush against his hand. The seagulls clamored, arguing over who would eat the stolen bag of chips. Crabs scuttled about the sand, claws raised like David against Goliath. The wind whipped against the tattered pink sail with its tuna logo. The sun glared off the water, burning his skin as he sat back in the old boat. Looking out on the horizon, he thought the old sailors weren’t so stupid for believing the Earth was

flat. He slid towards the stern of the boat, where he could steer and control his speed.

He came about, pointing the Clara Louise back towards the rotted dock, ducking as the boom swung around. The wind caught the sail and he leaned out, back facing the water to make sure the boat didn’t flip. One time, with his mother, he had flipped at low tide and the tip of the mast had broken off in the mud. He had stood and held the top of the mast to stretch the sail out while his mother piloted the boat.

He slowed down to take a sip of tea from his dented travel mug. A couple of kayakers were fishing and drinking. Visiting for the

weekend, he figured. He focused on the dock since many boats lay between him and home. It was like maneuvering through a labyrinth; hard enough for a human, another thing entirely for a sailboat. He recognized names on boats as they passed. Some he had never seen lift their anchor. What was the point of a boat if you never used it? He couldn’t imagine not using his Clara Louise.

He suddenly thought of the summer of 7th grade. His mother had pulled him out three days early – she said those last three days were fruitless anyway. She had picked him up with snacks and drinks, all set for a road trip. They left but then had to turn back.

She’d forgotten to pack clothes. She always remembered “the essentials,” but not the actual essentials. They drove to New York and spent the next couple days gallivanting around the city. His mother said one could learn more from spending time in a city than from time in a classroom anyway.

As the dock neared, he pulled up the centerboard to avoid getting stuck. He stood up slowly, making sure not to rock the boat. He reached out with his left hand and grabbed the second post which brought him to a stop. After climbing onto the dock, he tied the boat to the posts with his favorite clove hitch.

He took off the rudder, centerboard, mast, and sail and set them on the dock. He left the boat in the water, trusting that nothing would happen to his Clara Louise. Slipping on his flip flops, soles warm from the sunlight, he continued to the garage. He walked up the path around the house, the broken seashells crunching. He set everything down carefully, then pulled up the garage door. The centerboard and rudder went on

the wire rack, and the mast and sail leaned against the wall.

He walked back down again, and heard music carry across the water. Not knowing the song made him think of a line from Seger’s “Old Time Rock and Roll.” He recognized the kayakers from earlier as the source. He waved, but got no wave back. He wondered why they were still in the water after so long. While the sun set, the clouds turned a light shade of pink, reflected in the evening water.

He walked down the dock; bending with each step, but still sturdy. He smelled barbecue along with the ocean, and heard children giggle over the lapping waves. After walking up the shell-littered path back around the house, he pulled the garage door closed, its wheels squeaking as they followed their rusty tracks.

Hewoke the next morning as the sunrise snuck through his fish-patterned blinds. He shuffled to the kitchen and popped a bagel into the toaster. Throwing on some clothes and making his bed, he opened the blinds. The water glared at him.

He remembered mornings when he was younger; sleeping in, getting up only because he couldn’t make himself go back to sleep. When he finally got up, his mother had already made pancakes.

He peered over towards the dock, but didn’t see the Clara Louise. His heart raced. It must have drifted under the dock. He ran to the garage, cursing the old door as it squeaked along slowly. He ducked under. Flying down the shells, he stopped at the dock.

The clove hitch was gone, leaving the dock posts uncomfortably bare. Shards of green glass covered the dock. Sunlight glinted off them. A rusty fishing rod lay precariously on the end of the dock, and he finally understood. The kayakers, from yesterday, had taken the boat. Like modern pirates, they had sailed in and stolen his ship.

Speechless. He could only walk back to the garage, leaving the door ajar as he trudged up to the house. His bagel sat charred in the toaster.

They had only stolen his boat. But they had taken much more.

S C tream on ci s o s u ness of

an interview with

Ann Pancake

During the Winter of 2022, Woodberry welcomed Ann Pancake as our writer in residence through the White Family Visiting Writer Endowment. Known for her short stories and novels about Appalachia, Ms. Pancake hails from Romney, West Virginia. Some of her achievements include The Bakeless Prize, finalist for The Washington State Book Award, The New York Times Editor’s Choice Award, The Weatherford Prize and finalist for The Orion Book Award. Ms. Pancake and her decades of experience helped English classes rethink the creative process. She spent most of her time with Mr. Hale and his Honors 600 Creative Writing classes, diving into her award winning novel Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley. Her ideas of writing in a “stream of consciousness,” coupled with a profound focus on language and sound, changed the way many Woodberry boys think about writing. Senior Talon editors Edward, Conwell and Hugh had a chance to ask Ms. Pancake some questions before she finished her residency. Topics ranged from life in West Virginia to teaching in Japan, storytelling, strip mining and, of course, Bob Marley. She did not disappoint.

Edward Woltz, Conwell Morris & Hugh WileyConwell: At what point did you consider yourself an author?

Ann: I didn’t really see myself as an author until I published my first book. It was called Given Ground, published in 2001. I wrote it over the course of many years, just writing short stories. I didn’t know there was gonna

and write. And then if you don’t feel inspired, you have to play this mind game to make your writing at least feel inspired. I had to keep at it all the time.

Edward: You’ve spent the Winter with our Creative Writing Class. What are some of your goals when teaching students?

mental class is. You have to go in and engage. Where are these students? Where can I start? I learned a lot of that teaching overseas because I was teaching English as a second language, and I was teaching in different cultures. I had to read the room and see where we could start and where we could get to.

Edward: What pieces of prose are you most proud of?

be a book yet. I didn’t think I was good enough to make a book. I didn’t have very much confidence back then.

Hugh: Did you ever hit a wall while writing your first novel? I imagine the process is different from short stories.

Ann: Yes, but you have to write in such a way that it looks like you’re not powering through. I write short stories intuitively––I don’t think ahead a lot. But with the novel, you eventually have to start thinking ahead. You have to sit down every day

Ann: My biggest goal for my students is to help them find different ways of looking at the world than the ones they are accustomed to. That can occur through reading, but also by talking about the power of art and what art can do. You can see in radically different ways if you write, read or study art. I teach Native American and Appalachian literature as a way to get people thinking in a different way early on. The other thing I’ve learned is you have to start where the student is. Especially if you’re doing anything political, which the environ-

Ann: My novel Strange as This Weather has Been. That was a huge undertaking. It was a political novel, and it involved a lot of time with people who were suffering badly in West Virginia from mountaintop removal mining. I felt obligated to a lot of people that I had met because the book is based on interviews with people I really knew. So during those seven years when I would often feel like I wanted to give up, I would think, “If these people can live in this situation, I can at least write this book.”

Conwell: You allow yourself to write with a stream-of-consciousness. Is that a skill that

So during those seven years when I would often feel like I wanted to give up, I would think, “If these people can live in this situation, I can at least write this book.”

must be developed over time, or does the writer simply have to let go and write freely?

Ann: By my late 20’s I had read other writers who wrote in a stream-of-consciousness style, and then I read French feminist theorists who gave me even more permission to be experimental. I started taking more risks in my fiction, and I realize stream-of-consciousness allowed me to go deeper into my art and to give the reader a fuller experience of the characters, language, and situation.

Edward: Storytelling is a big part of Appalachian culture. What to you is the power of storytelling?

Ann: So much of it was gossip, ya know. It was people telling stories about wrecks or about hunting or about this house that had burned down or about somebody who drowned. But as

far as the power of storytelling, I think it helps the storyteller understand their own identity. It helps the listener understand his or her own identity and it helps build community among the people who are telling the story. It teaches empathy, compassion, and gives you a deeper understanding of how people operate. I find myself being less judgmental about people in general when I spend a while inside a character I am writing. Storytelling is honestly hardwired into human beings. Both to create it and to receive it. And traditionally it was for survival, because before literacy, people told stories to preserve cultural knowledge down the generations.

Ann: I know that there’s a certain number of people who just aren’t gonna read any of them, and I’m okay with that. I have my aesthetic vision for it, and then how I execute it depends on who the audience is. When I wrote short stories in my twenties, I didn’t think anybody would read them, so I didn’t care. I just wrote them for myself. They were more obscure. But with my novel, I wanted to educate people about mountaintop removal strip mining and the people affected by it. I knew that. I intentionally went back and calmed down some of the language, tried to write with less ambiguity, so the book would reach a larger audience.

Edward: Has there been change in the mindset of West Virginians about mountaintop removal since authors in the area have written more about it?

Conwell: You seem to respect your readers enough to handle the ambiguities of your stories. Are you ever worried about losing your reader?

Ann: Not so much. There was a huge movement against strip mining in the early 2000’s and it was life changing for me. But it’s been very, very frustrating. There is a little less [strip mining] now, but that’s mostly

I realize stream-of-consciousness allowed me to go deeper into my art and to give the reader a fuller experience of the characters, language, and situation.

because there is less market for coal now, not because environmental regulations have been enforced. It’s partly because West Virginia is completely lock, stock, and barrel controlled by gas, coal, and timber companies. It’s the poorest state except for Mississippi and it’s very hard to get any kind of political change there because the lobbying forces are so strong.

Conwell: Do you think some of the opposition moving away from mining is losing what makes West Virginia West Virginia?

Ann: Yes, I think there is a fear

of losing what makes West Virginia West Virginia. For example, working in mines and other resource extraction industries is tied up with masculinity in West Virginia. The work is dangerous, hands on, in the ground; and to lose that means losing a certain kind of masculine identity. So there’s a real crisis, and has been for years as these kinds of jobs go away, partly due to the movement towards clean energy, but also because of automation and mechanization. So men lose their jobs, and with that, they lose identity, and this is one reason for our drug problem. More women are going to college, and

more are becoming breadwinners. I love West Virginia dearly. There are so many good people there. It’s such a paradoxical place. It has so many deeply decent, hardworking, warm and generous people. But everyone has been caught in a mess, the natural resource curse, for over a hundred years.

Edward: What do you want people to know about West Virginia?

Ann: What’s most important to me is that people from outside West Virginia understand the humanity of West Virginians. One way [others] are able to

come in and exploit a place and create poverty is to dehumanize the people who live there. So, as long as the hillbilly stereotypes keep on coming and the

in a neighborhood with a fair amount of poverty and lots of support for Trump, but the people I live around don’t really care that much that we’re gay.

The qualities in West Virginians ... are rapidly disappearing elsewhere in our country, like neighborliness and generosity. It’s one of the poorest states, but it’s one of the states that gives the most to charity.

ideas that West Virginians are backwards and ignorant, drug addicts and incestuous, then people feel less guilt about exploiting the place. I want to get across to readers the qualities in West Virginians that are rapidly disappearing elsewhere in our country, like neighborliness and generosity. It’s one of the poorest states, but it’s one of the states that gives the most to charity. There are many contradictions in West Virginia. It’s known as being extremely homophobic and racist, and in some ways it is, but it’s also complicated. When people in West Virginia know you, they are likely to be more accepting, regardless of you being different from them. For example, I’m gay and I live with my partner

They like us because we help them out and they help us out. We haven’t had any problems from anyone.

Conwell: Where did you get the inspiration for the title of Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley?

Ann: It’s about my brother and my nephew. My brother’s an addict, and he used to take care of his four year old son. My nephew when he was little would say: Me and My Daddy Listen to Bob Marley.

No Cry” is one…“Three Little Birds”…Yeah, It’s “Three Little Birds.” That’s my favorite.

Hugh: That was 35 minutes of pure gold.

Hugh: Last but most important question, What’s your favorite Bob Marley song?

Ann: That’s hard. “No Woman,

TRASH GOD

by isaac james

by isaac james

Bored… we erected a trash god. We had uncovered another layer of decomposing junk. The pile would never end.

A doll’s head rolled across a particle board. Our lazy eyes followed her until a mangled colander snared her with frayed wires.

She dangled there, smiling up at our dull faces, with thinning acrylic lips and once-golden hair.

We put her on a plastic crate, laid castaway keepsakes under this makeshift shrine: a matchbox car, a Marlboro label, a magazine cutout of what we hoped had been her body.

We stood back and worshiped our genius, And then we left her on the purple plastic crate, turned our hands to other tasks and forgot that we were once bored… and had erected a trash god.

Junk Pile

by kiefer adamsThe two shoes lay side-by-side, They were not a pair. One little more than a sole With finely etched grooves And exposed nails. The other only paper thin leather Clinging to the toe And a worn-down heel. A chapel loafer

Outgrown by a well-off boy. A pump tossed after Too many missteps.

The two shoes lay side-by-side, They were not a pair. One little more than a sole With finely etched grooves And exposed nails. The other only paper thin leather Clinging to the toe And a worn-down heel.

A chapel loafer

Outgrown by a well-off boy. A pump tossed after Too many missteps.

Maybe they knew each other, This woman and boy. Passing on the brick path, Mumbling a quick hello. Or maybe they never met, And the only connection they have Are these two shoes.

Maybe they knew each other, This woman and boy. Passing on the brick path, Mumbling a quick hello. Or maybe they never met, And the only connection they have Are these two shoes.

EDEN

villanelle by nate steinEden lies abandoned still— No longer held by man, A futile journey up the hill.

They dared to face that godly will (The fall, it was His plan), So Eden lies abandoned still.

And we—cast out, reduced to nil—

Descended but then boldly ran That futile journey up the hill.

The cherub sentry rested ‘til He had to face the running, reckless man. Eden lies abandoned still. Access rests upon some skill That won’t be found in human plan. Still a futile journey up the hill.

The angels’ paeans—brazen, shrill— Ringing clearly o’er Earth’s span, Decree that Eden lies abandoned still, A futile journey up the hill.

Ford Garrard

Ford Garrard a

collection of study hall sketches

Unknown Sounds Sounds Unknown

AN interview with braeden lessane

by aiden moon and jordan mcconnell

by aiden moon and jordan mcconnell

“I got asked to make beats for modeling runways. I got asked to make beats for athletic videos. But the best experience while making music is getting together with my friends and making songs. Lots of smiles and laughter are shared during moments I’ll remember forever.”

AM: Can you give us an overview of your process?

BL: When I start a new beat from scratch, it’s like starting on a blank canvas. Sometimes I have no idea what to start with, and other times I have this idea playing over and over in my head all day which doesn’t come out until I open my computer. It also depends on what I feel like making. Some days when I have a lot going on and I want to make a beat in a short amount of time, I search online for already made melodies or “starters” and just add drums to them. Other times when I have a lot of free time, I make the melody and drums by myself, which is more time-consuming. When making melodies, sound selection is key. I have a variety of music software such as pianos, strings, synths, guitars, and so on. This software allows me

to play around with different sounds. Since my primary instrument is piano, playing these instruments on my MIDI keyboard and messing around in different keys, playing different chords and in different tempos helps me get an idea of what to add. Finally, you know it’s done when you mix and master all the sounds you added—when you’re impulsively bobbing your head up and down, getting into the groove of your music, eager to show someone your new beat.

JM: How did you get into making music? What inspired you?

BL: My brother and I used to beatbox and freestyle—it wasn’t good—when we were about twelve or thirteen years old. We both were curious about how beats on rap music were made.

We both installed this free music program called “Soundtrap’’ and messed around with it everyday. Since I was more musically inclined, I kept my interest in beat-making as my brother’s interest faded. For Christmas when I was in the 8th grade, I got a music software app called “FL Studio,” which I have been using ever since.

AM: What continues to excite you about making music?

BL: There are many things that excite me about music. One is the fact that there are still unknown sounds in music. There is still an unknown genre that can be found, like a lost treasure. The software gives me the creative freedom to make electronic music and gives me an opportunity to find that treasure.

Music is a form of relaxation. When I'm having a bad day, music can put me into another world.

BL: Music is a form of relaxation. When I'm having a bad day, music puts me into another world, where I'm not thinking about anything that goes on around me. Just like you read a book, watch Netflix or take a bath, music is my form of relaxation. The most exciting thing is when an artist raps or sings over your beat. In my junior year, I was fortunate enough to get a song with a big artist named Rod Wave. Hearing someone love your music and rap over it fills me with happiness.

JM: What’s the biggest challenge you have experienced?

BL: One morning in my 8:00 A.M. class, I opened my computer and was greeted with an

unusual blue screen. The screen read, “Automatic repair.” I didn’t think much of it as I always have updates on my computer. There were three buttons that advised what to do about the situation. I made a quick decision and clicked the button that read “Reset this PC,” thinking it would just restart. Unfortunately, it rebooted my whole computer, eliminating every file on the computer, including the music ones. It was like my computer was brand new. My heart sank. In the middle of class, people could see the regret and bitterness on my face.

AM: How’d you overcome that?

BL: It wasn’t easy. Facing adversity in the past, I would often

put myself down, feeling like my only option was to sit down and mope. I was tired of that. I was tired of constantly losing to my own consciousness. I knew I was capable of facing challenges, and I was stronger than that. Role models in my life – coaches and teachers, mainly – always emphasized perseverance and endurance. I realized this moment was a test. I reinstalled FL like nothing had ever happened and started making music again, from scratch. Not even a week after the incident, I uploaded a bunch of piano melodies on YouTube, some of which I had saved in my Gmail. One of my favorite producers, Drellonthetrack, a multi-platinum producer, messaged me on Instagram telling me he had added drums to two of my melodies and sent them out to artists. This was how I got the song with Rod Wave.

Cartoons

by hugh wileyMr. Huber’s summer retirement wardrobe

Where did Chase Kirk go?!?

Mr.

Affronti’s 2nd interview