IN P H

ILADEL PHI A

Henry Bermudez

Foreword 2

by William R. ValerioPhiladelphia Phoenix: Henry Bermudez’s Rebirth Over Two Decades 4 Gaby Heit, guest curator

Everything Is Interrelated, Nothing Stands Alone: Henry Bermudez’s Journey to Philadelphia 20 Jorge Luis Gutierrez

FOREWORD

Artists bring beauty into the world. It was the startling, organic beauty of Henry Bermudez’s work that struck me when I first encountered one of his colossally scaled paintings in the 2018 Woodmere Annual, juried by Syd Carpenter. The vocabulary of Bermudez’s paintings includes electric-colored plant forms, voluptuous ornamented creatures, glittery expanses with opulent flowers, and sensuous figures framed in artificial fur. More is more, and the works are thrilling. In 2022, Woodmere was honored to acquire Bermudez’s The RainMakers Dance (2018) thanks to the generosity of our great friends Frances and Robert Kohler.

Artists also tell the stories that make us human, sharing the thoughts, emotions, and narratives that help us make sense of the ups and downs of our existence. Bermudez’s ongoing story, from one work to the next over the last twenty years, has been the drama of his journey as an immigrant from Venezuela to cities around the world and ultimately to Philadelphia. Along the way he has continued to build a new identity that links his Latin past and his American present.

Bermudez’s story will resonate with many Philadelphians. Our city is one of the nation’s twenty-four Certified Welcoming Places, a designation that recognizes policies of inclusion. As of this writing, fifteen percent of Philadelphia’s population—more than 850,000 individuals if we consider the broader five-county region—are immigrants. With immigration policy a leading subject in national politics and cultural debate, we could not have planned a more timely exhibition.

But Bermudez’s work rises to a higher level still. He makes art that not only describes his experience as a political refugee and immigrant, but also expresses the opulence and passion of human sensuality and a delicacy in his over-thetop decorative sensibility. In our studio visits and conversations, I have come to understand that Bermudez’s work comes from a unique internal joy that has sustained him through tough times and victories alike. Whether his subjects are the clash of Europe with the New World or the strivings of people against obstacles, or interpretations of subjects like Mickey Mouse or Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, there is a spiritual, quasi-religious sensation of positivity that radiates from his canvases. Bermudez recognizes the imperfections of his adopted country and the frequent hardships of those who are displaced. He is also patriotic, and for him, America, as a country that guarantees freedom of expression, is a magnificent place to be.

My first words of thanks go to Henry Bermudez himself. This exhibition evolved out of a relationship between the Museum and the artist that has grown deeper and more meaningful over time. Our understanding of Bermudez’s history and broader place in the spectrum of Latin American art comes from our partnership with Jorge Luis Gutierrez, a long-standing champion of Bermudez’s art who has placed his achievement within the global conversation of artists from Latin America. We also thank our guest curator, Gaby Heit, who organized every aspect of the show and, in particular, worked one-on-one with the artist to select works for

display that express the sweep of Bermudez’s two decades in Philadelphia. Thank you, Jorge and Gaby, for your illuminating essays that are published in this catalogue.

Bermudez is represented by the Wexler Gallery. The Museum is grateful to Sherri and Lewis Wexler for a partnership that has enriched so many aspects of the exhibition and its programs. As always, Woodmere’s staff approached this endeavor with enthusiasm, professionalism, and highest levels of creativity.

Thank you to our curatorial and education team, Laura Heemer, Rachel Hruszkewycz, Rick Ortwein, Hildy Tow, Lya Rodgers, and Amanda Monroe.

As always, Woodmere depends on the generosity of many individuals for the funds that sustain our activities. The Museum thanks our former trustee, the late Dorothy J. Del Bueno, for creating an endowed fund to support our exhibitions. We also extend our gratitude to an anonymous donor, and importantly, we appreciate the generosity of our members, whose support is foundational to all we do. Thank you, everyone!

WILLIAM R. VALERIO, PHD The Patricia Van Burgh Allison Director and Chief Executive Officer HENRYPHILADELPHIA PHOENIX: HENRY BERMUDEZ’S REBIRTH OVER TWO DECADES

GABY HEITHenry Bermudez’s work over the last twenty years is a journal of collected imagery and symbolic representation. Having built a highly successful career as an artist in his native Venezuela, he started over, as if from scratch, when he immigrated to the United States in 2003. As Bermudez describes it, he began to build “a new American life.” This exhibition and this essay explore how his creative practice has evolved with his changing life circumstances. Through it all, his work has remained a visual expression of his internal engine of optimism; he embraces America with pride while also exploring the cultural representation of political power.

One of the last paintings Bermudez completed before he left Venezuela in 2003, from the series The Eagle and the Sun (2003), is remarkably prescient. Within the work there are two sets of relationships. At left, the sun (representing the artist himself) looks down on an eagle perched in a tree. At center the same sun and eagle appear again, but now they are intertwined with each other and with the plant life around them. We can interpret these as two states of being for the artist: one separate from the US, and the other, moving forward together with his new country to a new life. One way that Bermudez inserts himself into the narrative of his work is as the face of the sun, and it is important to note that these are bald eagles, a bird specifically symbolic of the US. The foreshadowing is remarkable: just months after he completed the painting, Bermudez left Venezuela to build a new life in the US. Since then, he has taken on the challenge of trying to understand what it

means to become an American, and the freedoms and responsibilities that citizenship entails.

In Venezuela, Bermudez was a celebrated artist who, in 1986, represented his country in the 42nd Venice Biennale. Venezuela had once been one of the wealthiest in South America, but its democratic government collapsed under President Hugo Chávez and human rights abuses, corruption, anti-democratic actions, violence, and poverty quickly escalated. Many Venezuelans immediately fled when Chávez took office, the first of several mass migrations. Looking for a safe place to live, Bermudez initially moved to Miami, and then relocated to Philadelphia in 2003. Not knowing many people, or any English, he resorted to washing dishes, and slept on a friend’s sofa. He had left everything behind, but persevered, confident that he could achieve the American dream.

Once settled in Philadelphia, Bermudez began to take part in the city’s thriving art scene. In 2004 he was commissioned by Mural Arts to create five murals in the city’s Latin American neighborhoods— the first income he received as a professional artist since his arrival in the US. Hanging Garden (2004) was a multi-artist collaboration with a tropical forest theme. One collaborator, Frank Hyder, was the friend who initially invited him to Philadelphia. Bermudez also began to adapt his artistic practice to his new environment: lacking proper ventilation to paint with oils, he turned instead to acrylics and cut paper. And he began participating in juried exhibitions. A later mural, The Circle (2017), depicts a partitioned circle against a lace-like background,

a reference to the most famous of pre-Columbian images, the so-called Aztec calendar stone, from the grand plaza of Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City).

ARTISTIC INFLUENCES

The most significant throughline in Bermudez’s work in Venezuela and the US is his ongoing embrace of Latin American imagery. His extensive travels in Mexico, Peru, and elsewhere have left a permanent imprint in his imagination. He understands the shared symbols and mythologies from pre-Columbian cultures, like the Aztecs and Incas, are a rich source of imagery to re-evaluate and reclaim.

In a broad sense, Bermudez, like many Latin American artists, points to the magical and mystical in folklore. Inspiration from ancient religions and the occult, as well as complex views of Catholicism and Santería, are behind many of his messages. He emphatically repeats certain icons and creatures in his paintings, reinforcing each work’s role as a microcosm of the larger story of his career. These recurring symbols include cats, horses, birds, and snakes, as well as hybrid creatures from ancient South American and Afro-Caribbean cultures, like suns with faces, Quetzalcoatl (the Aztec feathered serpent deity), leopards shouting rainbows, and various anthropomorphic beings. As in some European cultures, Bermudez’s mythological “monsters” are generally a combination of different

creatures’ strongest parts. Some are sacred, some magical, all mythological, having deep personal meaning for the artist.

Bermudez sometimes turns a negative symbol into something positive and vice versa. The omnipresent Quetzalcoatl points to both heaven and earth. When the deity encounters the cross in Resting Snake (2007), it dies, conquered by European colonialism. Bermudez also takes advantage of symbols having different meanings in different cultures, and how they evolve over time. Decoding the sequence of symbols and images reveals additional meanings, reflecting the artist’s past, present, and future

dreams. He often incorporates roses into his work because they are widely recognized as a sign of love, connecting different cultures and languages.

A major inspiration for Bermudez in Philadelphia has been Black and African American culture. Prior to his American life, from 1965 to 1970, he worked as a teacher to Afro-Caribbean youth in Bobures, a small jungle village on the northern coast of Venezuela. He pays tribute to those students in works like Gonzalez Sisters (2017), where they appear lovingly enmeshed in their lush landscape, with a vase of roses. The art community in Philadelphia that Bermudez has come to know is diverse in ways

he hadn’t previously imagined: without the rigid social hierarchies of Venezuela, Black and Brown artists (like him) have a voice. “Bobures taught me about one sector of our culture that is little shown in the big cities of Venezuela—it is the culture of African descendants,” he says. By contrast, here in Philadelphia, “It’s a great moment for artists of color, and artists of other nationalities in America, from Africa, Asia, and Latin America.”

Bermudez is attuned to issues of social consciousness, while aspiring for progress and racial harmony. In Miss America (2019) he envisions the pageant winner as a Black woman in a red, white, and blue sparkling crown; hers is the largest visage in all of Bermudez’s work. When asked

about this image, the artist points to his students in Bobures, his current pupils in Philadelphia’s underserved communities, San Benito (the Black saint of Bobures), and Kelicia Pitts, an African American model for many artists in Philadelphia and Bermudez’s local muse. Miss America is especially important; she is the complete connector woman, his past informing his future. In the painting, she is flanked like a queen by jaguars, which reach out to touch her, an expression of goodwill. With regard to an embrace of Black culture, Bermudez transforms and reappropriates a Philadelphia treasure, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, into his Black Sunflowers (2023), taking ownership of the white European artist’s work in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Bermudez creates his own symbolic language to include stories of European colonialism and the American dream in his work. He is keenly aware that the American dream is entwined with Western colonialism and that individual freedoms for Americans coexist with the erasure of freedom of those colonized by Americans. The symbols Bermudez uses in these ways are borrowed, reappropriated, and in conflict. The Duchess is a recurring figure in Bermudez’s work, based on Piero della Francesca’s iconic Portraits of the Duke and Duchess of Urbino in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Bermudez notes that Piero died in 1492, the year of Columbus’s voyage to America, and she appears for the first time in works from the early 2010s in his Visitor series (2010–11) and Medusa (2011); series; the Duchess becomes his stand-in for the famous explorer. In Piero’s depiction, the couple stare at each other in profile; they are as confident in their relationship as they are in their dominion just beyond them, a view from their castle. For Bermudez, the single figure of the Duchess is

taken out of her surroundings, appearing out of place in new environments, whether it is among Black and Indigenous figures or lost in the abstract jungles of the so-called New World. In this sense of displacement, the Duchess is the antithesis of his later painting of the Black Miss America, who represents a synthesis, a center of gravity, or coming together of history and geography. She brings her culture with her. Bermudez’s Duchess, by contrast, usually floats above, often literally pasted on top, disconnected from the other elements of the composition. She is an interrupter. Similarly, in What Mr. von Humboldt Saw When He Visited the Orinoco (2008), Bermudez tells the story of Alexander von Humboldt from a Latin American point of view. Von Humboldt, a German explorer and naturalist, documented the flora, fauna, and native peoples of Venezuela on his expedition to South America authorized by the king of Spain.

NEW EXPERIMENTS AND NEW SYMBOLS

For Bermudez, the greatest change that came from working in Philadelphia is the freedom to experiment. The style of representation he has developed is marked by undulating curves and repeating gestures, often suggesting scales, feathers, tentacles, and vegetation in one living mass. Relative to his previous modes, he perceives that he can push his forms harder and break the rules, so to speak, that he had previously tried to follow. His abstract drawings, mostly in. black and white, appear to be elaborate graphic designs based on organized lines and detail.

Bermudez considers The Heaven (2007) to be a milestone of his career in Philadelphia, in which he confidently scaled up in size, increased the intensity of dot decoration, and started layering cut paper. The work presents floating figures and freeform ornamentation that suggest astrology and constellations. As he himself sees it, this new stylistic freedom is a release that runs parallel to growing more comfortable in his new environment.

Freedom and evolution are also revealed in his adaptation of new materials, which have shifted from traditional oil painting to cut paper, to a liberal use of glitter, faux fur, plastic flowers, and wood carving. His cut paper works also start to move away from the wall, undulating and becoming more sculptural and adjustable. If previously, the painter who Bermudez acknowledged as his most important inspiration was the French renegade “primitivist” Henri Rousseau, he now embraces a broad range of inputs coming from many places. Urban culture and his students continue to be important, but he also looks to the work of the artists close by, including that of his wife Michelle Marcuse, a sculptor who assembles found and unconventional materials in dramatic threedimensional compositions. He also admires the work of Barbara Bullock, the great master of cutting, twisting, and sculpting paper in space.

In Philadelphia, Bermudez has not only experimented with new materials, but also has

felt a deep freedom and obligation to exercise his political voice. In Venezuela, his paintings included symbols in a quieter, less emotive language. Looking back, Bermudez describes that his process and thinking about subjects was more “expected.” His Philadelphia works tell us more about a conflicted artist, finding his place in American society and expressing his freedom to criticize. Premonition of a Civil War (Venezuela) of 2019 is a rare overt statement on his homeland and reappropriation of Dalí’s nightmarish Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) of 1936, painted six months before the Spanish civil war began. Dalí’s iconic work expresses the destruction and horrors of the Spanish conflict, considered a prelude to World War II. Comparatively, Venezuela is an extremely divided country, and has had tremendous unrest since the mid-nineteenth century. And some Venezuelans expect a civil war in the near

future. In Premonition of a Civil War (Venezuela), Bermudez expresses his alarm at that prospect. A partial figure with a vicious feline head breathes flames in the colors of the Venezuelan flag (as if it’s just been eaten) while stepping on the back of a crouching headless figure who loosely holds a small Venezuelan flag. It’s a dark painting, and far from the vibrant tones of Bermudez’s other work. The shape of the centerpiece arrangement, and the accentuated negative space of the complicated figures, replicate those in Dali’s painting. But Bermudez’s figures are not defeated.

Flags are important symbols in Bermudez’s work, and the American flag is used to different ends in different contexts. In Pledge of Allegiance (2018), for example, there are several flags next to faces of every color, suggesting pride in immigrant citizenship of all stripes. It reflects Bermudez’s personal journey and becoming an American citizen

HENRY BERMUDEZ IN PHILADELPHIA

HENRY BERMUDEZ IN PHILADELPHIA

in September 2013. And when the flag makes more subtle appearances, in different sizes, positions, and relationships to other elements in the overall image, it becomes a more direct political statement. Bermudez, in depicting the flag as a symbol, often makes it elusive and variable, but definitive presence. It slips out of the frame, half in or half out, or isolated and small in a corner. It could be lost. We might think about the flag’s positioning in our national anthem. It could be lost, but “the rockets’ red glare . . .gave proof through the night that our flag was still there.” So, the flag is almost out of reach, leaving the frame in The Wall (2018). It is tightly wound at the bottom of Zero Tolerance (2018) while an out-of-frame parent and child reach for each other. Quetzalcoatl “unmasks” the scene. Both paintings depict the plight of political refugees at the US border with Mexico and offer a criticism of our current political landscape. In other recent paintings Bermudez uses Mickey Mouse

as a glittering symbol of American capitalism, commercialism, and entertainment, a mixed message on freedoms and priorities.

THE AMERICAN MYTH

As complex as Bermudez’s work can be in its exploration of American culture, the artist continues to embrace the US as the greatest utopia the world has known. America remains the myth, the place “where dreams come true,” the great mythological promise he perceived from afar as a younger man in Venezuela. An abstraction, the mythological promise can’t fail; it may be that in our imperfect lives we don’t live up to America, but still, America stands as a supreme abstraction of hope and promise. This positive embrace of America is the strength that Bermudez believes made it possible to for him to persevere, and now succeed.

On October 20, 2023, Bermudez celebrated his twentieth year in the US, or as he likes to describe it, his “rebirth.” He does not like to dwell on his life in Venezuela. He considers himself an American artist from Venezuela, a Latin American artist, a Philadelphia artist who continues to find his place in the great American melting pot. He continues to be a collector of symbols and images from different cultures, amid a vibrant life in America’s founding city. There is no single American culture, and as the

Zero Tolerance/ Tolerancia cero, 2018 (Courtesy of the artist)

population is always changing, it is becoming more pluralistic. As an artist, Bermudez is constantly experimenting, and his ultimate experiment has been building his new life as an American citizen in Philadelphia. He has been reborn in the birthplace of American democracy.

EVERYTHING IS INTERRELATED, NOTHING STANDS ALONE: HENRY BERMUDEZ’S JOURNEY TO PHILADELPHIA

JORGE LUIS GUTIERREZ“It’s not easy to start over in a new place,” he said. “Exile is not for everyone. Someone has to stay behind, to receive the letters and greet family members when they come back.”

—EDWIDGE DANTICAT, BROTHER, I’M DYING

Henry Bermudez’s interest in the visual representation of cultures and mythologies has driven his work throughout his career. His journey of unique geographical, artistic, and human observation has taken him from his formative experiences in small, isolated communities in the Caribbean to representing Venezuela in the Venice Biennale. His work transcends national boundaries. An artist-nomad, he has lived in Mexico City, New York, Caracas, Rome, Maracaibo, Venice, Gelsenkirchen, Lima, Kunshan, to name a few, and, for the past twenty years, Philadelphia.

As a young man, Bermudez formed his powerful artistic vision from the fusion of religious and social traditions of the Venezuelan coastal Afro-Caribbean community of Bobures, whose symbolism and iconography arose from the African diaspora. It occasioned his first steps, breaking from the formalities of mainstream styles learned in art school, and launched him into a long search for new forms of expression. Bermudez continues to pursue intense research, experimentation, and hybrid artistic approaches, fluidly moving between modes. He has realized his gestural and expressionistic style on a significantly larger scale, and continues

to capture his now-emblematic subjects: the intersecting icons of myth, human history, and nature.

THE NOMADIC STRATEGY: THE LOOK OF THE “OTHER”

“I haven’t been everywhere, but it’s on my list.”

—SUSAN SONTAG

Bermudez assimilates elements of the diverse geographies in which he has lived and transforms them into metaphors of the past, the present, and future: Latin American myths, symbols, and syncretism (Venezuela, Mexico, Peru); dominion, conceptualism, and mixed media (New York, Rome, Germany); globalism in art, adapted iconography, and experimentation (Philadelphia). He does not follow fashionable art-collecting trends, nor does he cling to the disciplines dividing art into accepted classifications of ethnography, folklore, semiotics, and anthropology. His approach is based on a specific nomadic methodology, capable of circulating through history and the complexities

HENRY BERMUDEZ IN PHILADELPHIA 21

Flor, 2019 (Courtesy of the artist)

HENRY BERMUDEZ IN PHILADELPHIA 21

Flor, 2019 (Courtesy of the artist)

of today’s cultures. Through each of his works, Bermudez seeks to redesign the forms used to narrate a visual record of hybrid culture and society. It includes, without reference to any hierarchies of value, the Anglo-Saxon, Latin, Asian, and Afrodescendant multitudes.

Bermudez’s contributions to contemporary American art are tied to his global journey. His work contains signs and images of mixed and unfinished memories of past and contemporary societies. He paints a world that transforms minute by minute, informed by the achievements, triumphs, contradictions, and cross-failures of its inhabitants. His creative strategy is nonlinear; it is malleable, developing on several parallel levels of narration and reading.

The major cultural forces of the American continent—not only English, French, and Spanish, but also Indigenous and African—make tracing any artistic development a fragmented process. Bermudez’s artistic project is loaded with narratives inspired by milestones, myths, and stories from many of these cultures, from sophisticated civilizations that were present in whole splendor centuries before the arrival of Europeans, through a long process of confrontations, exterminations, mergers, innovations, and unexpected mixtures, to the post-colonial period.

Modernism in Latin America became an experience of mixed and unfinished results, reflecting the region’s struggles in its search for identity and its turbulent social and political history. In this context,

the prevailing art trends were figuration inspired by national values, exemplified by the work of Diego Rivera and Rufino Tamayo, and geometric abstraction and concrete art open to foreign influence, embraced by artists such as Julio Le Parc and Jesús Rafael Soto.

Bermudez has broken away from these dominating art trends. He dissociates himself from established idealizations and stereotypes, a move that intensified when he arrived in Philadelphia. Philadelphia liberated him from a narrative burden and initiated a highly fruitful experimental period.

Bermudez continues to tell elaborate, multidimensional stories about what we are. In this sense, as Dawn Ades, a member of the British Academy, former Tate trustee, and professor of art history at the Royal Academy, states: “Latin America occupies a peculiar position, being both part of and distinct from Western artistic traditions and the modernist canon. On the rare occasions when it is included in the general history of art, this is almost always in terms of European norms, so stereotypes

are repeated, and Latin American art is reduced to the work of Mexican muralists and magical realism.”1

ONE OR MULTIPLE ORIGINS: CONTEXT, IN TIME AND PLACE

“One must always maintain one’s connection to the past and yet ceaselessly pull away from it.”

—GASTON BACHELARD

Bermudez conceives of Latin America, where he developed the initial phases of his creative narrative, as his starting point. However, from that point onward, he proposes a journey gleaned from multiple places that have nurtured his ideas. Bermudez does not seek recognition of his work based on his origins; instead, he embraces an absolute aesthetic autonomy. As he views his work as part of a global language, there are no

hierarchical classifications or divisions and, thus, no regionalisms or provincialisms.

Decades of political turmoil, social contrast, and radical change in art pushed Bermudez out of his artistic comfort zone and fueled the development of his discourse. In the 1970s, he left Maracaibo for Mexico, where the first transformation of his work occurred, as observed by noted critic Roberto Guevara:

“Mexico’s experience was important. A more accurate narrative insisted on describing the places of a city with the same resources as the previous drawings: The colors began with solemn meaning at the beginning, as the use of greys, gilded, and silver, then becoming an inflamed intensity of colors, more additive than integrative. The fire was outside the drawing. We had to wait for fusion at the right temperature.”2

The development of Bermudez’s work belongs to a counterbalancing movement from the 1970s,

linked to the reflection, experimentation with, and transmission of underlying meanings in art. In this period, mythical symbols like the eagle, the tiger, and the snake are integrated into his intense environmental landscapes.

The 1980s marked a paradigm shift with the emergence of an economic model of globalization, reshaping the art market, collecting, and the investment value of art. Nowhere was this commodification of creativity more evident than in New York. Artists such as Richard Prince, JeanMichel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Willem de Kooning, Jeff Koons, Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Eric Fischl, Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, and Damien Hirst defined the city’s profile as the center of the art market.

It was against this background that Bermudez left Mexico for New York. It was there that the unbridled art market unfolded before his eyes, and there that he first experienced the meanings, modes of operation, dynamics, and practices of the Western art world. Equally important to him were the city’s

great museums, auction houses, and galleries. The energy, shock, and intensity of New York spurred Bermudez to study the elements that characterized his narrative and creative strategies. As time passed, his work began to operate beyond the framework of Latin American art. He felt that this definition did not contain his work. After the New York experience, his work changed with larger formats, color shifts, and more clarity in form and content.

This experience allowed him to observe art’s migratory mobility, artistic diasporas, and the redefinition of identities within these contexts. Pepón Osorio, Andres Serrano, and Ana Mendieta, among others, shared Bermudez’s cross-cultural experience. These creators assumed a perspective unknown to him until then—the existence and significant contributions of Latino artists in the United States.

Returning to Venezuela in the mid-1980s, Bermudez began working in larger formats, with new propositions and strategies in the crossdiscourse between drawing and painting. His work began to show greater command and frankness in use of color and a high degree of fluidity in the combined different techniques and forms. The attention of critics and curators attested to a belief in its growing significance. After having his

work exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Caracas in 1986, Bermudez was selected to represent Venezuela at the 42nd Venice Biennale under the curatorship of Thomas W. Sokolowski, alongside artists including Isamu Noguchi, Sigmar Polke, and Frank Auerbach. It was an extraordinary and singular honor.

Encouraged by the national recognition and appreciation of his work in the art market as well as

the nomination to represent his country in Venice, Bermudez moved to Rome to find new references and a broader global art language. Where Mexico had signified pre-Columbian cultures, Rome referred to the art of Western civilization. After Italy, Bermudez returned to Venezuela unwilling to compromise his art’s formal and conceptual direction. His work was well positioned in the art market, exhibited in diverse museums, and was acquired by a number of private and institutional collectors.

With the stability offered by recognition and response in the art market, Bermudez decided to leave again—this time for Germany. There his work underwent several shifts: the colors decreased in intensity, and the fusion between drawing and painting became stronger. The symbols and references took on new meanings. But the

transformation in his work was not the only thing changing; the global financial crisis of 1987 ushered in a severe recession. As a result, artists began looking beyond the art world for their themes. The AIDS crisis, gun control, environmental issues, class, race, and the gaze of the “other” took their place on the art agenda. The notion of the artist as an ethnographer emerged. Theorists such as Edward Said, Frantz Fanon, Thomas McEvilley, and Édouard Glissant took an active role in the critical dialogue of the period.

Latin American and Caribbean art experienced growing visibility compared to previous decades. Inventories of the region’s artwork emerged in multiple exhibitions, both local and in non-Latin American territories. Exhibitions in Venezuela, Spain, US, and Colombia brought together international loans from such institutions as the Luis Ángel

By the 1990s, dominant ideas of the avant-garde and modernism had been reduced to rhetoric and semantics. Bermudez kept his discipline of research, rigorous work, and production in his studio as an everyday practice. He strove for excellence in his career, not temporary labels. Meanwhile, Venezuela accelerated its descent into a deepening political, social, and economic crisis.

PHILADELPHIA SERENDIPITY

“A culture, we all know, is made by its cities.”

—DEREK WALCOTT

In 2003, with the tense economic and political situation in Venezuela, Bermudez stopped in Philadelphia while on a visit to New York and would never leave again. He had been searching for a city that would hold fast to the traditions, interests, or ideals of America and Europe in his

need to reimagine new ways of doing. Philadelphia appeared as an epiphany in his life. Known in colonial times as the “Athens of America” because of its rich cultural life, the city had shaped itself as a land of opportunity for European immigrants for hundreds of years. It brought together intellectuals who forged new concepts of freedom, republic,

federalism, and the social model of democracy and coexistence. It offered Bermudez a rich insights into history, culture, race, and ambiance. He saw an intellectually dense urban center with historical references. He decided that this city was his destiny. He became an unapologetic immigrant in exile there.

Henry Bermudez is now a Philadelphia artist, living, creating, teaching, and developing his work. His current interest involves the fabrication of imaginary paradigms of diverse societies, making possible visual narrations that surprise us, provoke questions, and move us beyond our everyday lives.

NOTES

1 Dawn Ades, Writings on Art and Anti-Art (London: Ridinghouse, 2015).

2 Roberto Guevara, 1985, “Los triunfos del dibujo” [The Triumphs of Drawing], National Journal of Culture, 47(259).

SELECTED CHRONOLOGY

1951

Born in Maracaibo, Venezuela

1965–70

Studies at the National School of Art, Maracaibo

Teaches in Bobures, Zulia, Venezuela

1972

First solo exhibition, Gaudi Art Gallery, Maracaibo

1976

Moves to Mexico City, Mexico

1976–79

Studies at the National School of Art, Mexico City

1977

Solo exhibtion, San Angel Art Gallery, Mexico City

1980

Moves to New York

1980–83

Studies at the Art Students League, New York

1983

Returns to Venezuela (Caracas)

1984

Group exhibition: Three Artists for a Biennial, Museum of Contemporary Art Sofia Imber, Caracas, Venezuela

Solo exhibition, Arch Gallery, New York

1985

Moves to Rome and remains there for one year

1986

Represents Venezuela in the XLII Venice Biennale

1987

Group exhibition and award: Christian Dior Grand Prize for Visual Arts, Euroamerican Art Center, Caracas

1998

Group exhibition: The Infinite Signs of the Sun, Museum of Contemporary Art of Zulia (MACZUL), Maracaibo, Venezuela

1999

Hugo Chávez is elected president of Venezuela, giving rise to an authoritarian populist regime

2001

Group exhibition: X Biennale International of Drawing, Taipei, Republic of China

2003

Moves to Miami

In October, relocates to Philadelphia

Group exhibition: The Box, Goldie Paley Gallery, Moore College of Art & Design, Philadelphia

2004

Completes first of six murals for the City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Projects, including collaborations with artists Frank Hyder, Michelle Angela Ortiz, and Paul Santoleri.

2009

Group exhibition: To Be or Not to Be/A Painter’s Dilemma, Rutgers University Department of Fine Arts, Camden, New Jersey

2010

Group exhibition: Suenos: Latin American Contemporary Art, Noyes Museum, New Jersey

Solo exhibition: Encantamientos/Enchantments, The Painted Bride, Philadelphia

2011

Begins teaching at the Career and Academic Development Institute, Philadelphia

Completes installation at Philadelphia International Airport, Terminal C

Solo exhibition: Pen, Ink, Paper, Projects Gallery, Philadelphia

Group exhibition: Philagrafika: The Graphic Unconscious, Philadelphia

Receives Pollock-Krasner Foundation grant

2012

Solo exhibition: Rosenfeld Gallery, Philadelphia

2013

Completes Kelicia’s Project series

In September, becomes a US citizen

2014

Group exhibition: Flight Plan: Drawings on Paper and Leaf: Henry Bermudez and Michelle Marcuse, Denise Bibro Fine Art, New York

2015

Begins teaching at Fleisher Art Memorial, Philadelphia

Solo exhibition: Racso Art Gallery, Philadelphia

Group exhibition: Borderless Caribbean, Haitian Cultural Art Alliance, Miami

Group exhibition: Apollonian|Dionysian: The Constraints of Freedom, Painted Bride, Philadelphia

2016

Visits Peru for research

Group exhibition: Paisajes, Galleria de Artes

Visuales, University of Ricardo Palma, Lima, Peru

Group exhibition: Destination Latin America, Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase, New York

Group exhibition: Taller Boricua, New York

Emerging Visual Artists, Peter Benoliel Visual Artist Fellowship

2017

Awarded Libby Newman Artist Residency, Brandywine Workshop and Archives, Philadelphia

2018

Group exhibition: Woodmere Annual 77th

Juried Exhibition, Woodmere Art Museum, juried by Syd Carpenter

Solo exhibition: Borbures: The Presence of Memory, Dene M. Louchheim Faculty Fellowship award exhibition, Fleisher Art Memorial, Philadelphia

Solo exhibition: In Black and White, Delaware College of Art and Design, Wilmington

2019

Solo exhibition: Totally Mythological, Delaware Contemporary, Wilmington

2020

Solo exhibition: Desolación en la Mente, Taller Puertorriqueño, Philadelphia

Solo exhibition: Tattoed Nature, List Gallery, Swarthmore College

2022

Group exhibition: Cultivating Space, Rowan University Art Gallery, Glassboro, New Jersey

2023

Secures representation by Wexler Gallery, Philadelphia

Group exhibition: Latin American, Caribbean, and Latinx Voices, Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase, New York

2024

Solo exhibition: Henry Bermudez in Philadelphia, Woodmere Art Museum

Group exhibition: MADE in PA, Palmer Museum of Art at Penn State; The RainMakers Dance (2018) in Woodmere’s collection is included

WORKS IN THE EXHIBITION

All works by Henry Bermudez (American, born Venezuela 1951).

From the series The Eagle and the Sun/De la serie el águila y el sol, 2003

Oil on canvas, 13 x 25 in.

Courtesy of the artist

The Heaven/El cielo, 2007

Acrylic, silver, and gold leaf on cut paper reassembled on canvas, 96 x 192 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Resting Snake/El reposo de la serpiente, 2007

Acrylic on cut paper, 96 x 48 in.

Courtesy of the artist

What Mr. von Humboldt Saw

When He Visited the Orinoco/ Lo que von Humboldt vió cuando visitó el Orinoco, 2008

Acrylic on cut paper reassembled on canvas, 46 x 63 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Medusa, 2011

Oil and acrylic on paper, 27 x 60 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Philadelphia, 2011

Digital print with reflective foil layer and die-cut, 18 x 15 in.

Woodmere Art Museum: Gift of Philagrafika, 2015

The Scream/El grito, 2011

Acrylic on cut paper, 26 x 65 1/2 in.

Courtesy of the artist

The Tiger Spiral/La espiral del tigre, 2011

Acrylic on cut paper, 25 x 65 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Visitor VIII/La visitante VIII, 2011

Oil and acrylic on paper, 22 x 60 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Birds/Pájaros, 2013

Acrylic and ink on paper, 30 x 22 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Petals I/Pétalos I, 2013

Acrylic and ink on paper, 30 x 22 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Tattooed Nature/Naturaleza tatuada, 2013–21

Digital image and acrylic on cut paper, 120 x 120 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Cloud of Water/Nube de agua, 2017

Acrylic and glitter on canvas, 72 x 120 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Gonzalez Sisters/Las hermanas Gonzalez, 2017

Acrylic and glitter on canvas, 96 x 60 in.

Courtesy of the artist

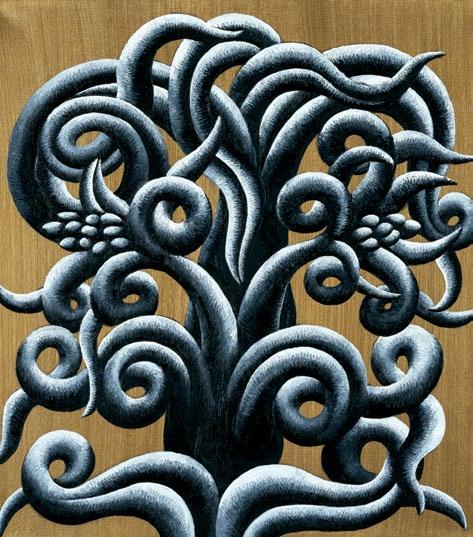

Brown Tree I/Árbol marron I, 2018

Acrylic on paper, 30 x 22 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Rain Over Red Forest, 2017

Lithograph, 30 x 42 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Brown Tree II/Árbol marron II, 2018

Acrylic on paper, 30 x 22 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Pledge of Allegiance, 2018

Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 72 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Tattooed Tree I/Árbol tatuado I, 2018

Acrylic on paper, 30 x 22 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Tattooed Tree III/Árbol tatuado III, 2018

Acrylic on paper, 30 x 22 in.

Courtesy of the artist

The Wall/La pared, 2018

Acrylic on canvas, 72 x 120 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Zero Tolerance/Tolerancia cero, 2018

Acrylic and glitter on canvas, 83 x 72 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Buscando Acomodo, 2019

Ink and pastel on paper, 11 x 14 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Flor, 2019

Acrylic on paper, 13 x 9 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Miss America, 2019

Acrylic and glitter on canvas, 50 x 72 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Premonition of a Civil War (Venezuela)/Premonición de una guerra civil (Venezuela), 2019

Acrylic on canvas, 82 x 70 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Our Cousin from Europe Visiting America/Nuestra prima europea visita America, 2020

Oil on canvas, 53 x 48 in.

Courtesy of the artist

The Singer, 2020

Acrylic and oil on canvas, 20 x 46 in.

Courtesy of the artist

From the series Black Landscape/ De la serie paisaje negro, nos. 1–8 2021

Oil and acrylic on canvas, 25 x 22 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Tattooed Tree I/ Árbol tatuado I, 2018 (Courtesy of the artist)

From the series Black Landscape/ De la serie paisaje negro, nos. 9–11 2021

Oil and acrylic on canvas, 26 x 22 in.

Courtesy of the artist

From the series Black Landscape/ De la serie paisaje negro, no. 12 2021

Oil and acrylic on canvas, 27 x 22 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Spiral I, 2021

Courtesy of the artist

Spiral II, 2021

on canvas,

Courtesy of the artist

in.

Spiral III, 2021

Acrylic

Courtesy of the artist

Mythological Creature, 2022

Acrylic and glitter on paper, 18 x 24 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Black Sunflowers/Girasoles negros, 2023

Acrylic and glitter on canvas, plastic sunflowers and synthetic fur, 88 x 89 in.

Courtesy of the artist

The Stripper/El nudista, 2023

Acrylic

Courtesy of the artist

Untitled (Sankofa and Duchess), date unknown

Acrylic on paper, 9 x 12 in.

Courtesy of the artist

MICHELLE MARCUSE AND HENRY BERMUDEZ

Untitled, 2021

Cardboard and oil on cardboard, 39 x 46 in.

Courtesy of the artists

Woodmere Art Museum receives state arts funding support through a grant from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, a state agency funded by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

©2024 Woodmere Art Museum. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission of the publisher.

Catalogue designed by Barb Barnett and Kelly Edwards, and edited by Gretchen Dykstra, with assistance from Irene Elias and Rafaela Brosnan.

All photography by Jack Ramsdale, except:

Peter Camburn: Resting Snake, p. 7

John Carlano: Migration, p. 27; Tattooed Nature, p. 23; Cloud of Water, p. 22; The Wall, pp. 18–19; Pledge of Allegiance, p. 16; Zero Tolerance, p. 17; Premonition of a Civil War, p. 15

Courtesy of the artist: Gonzalez Sisters, p. 6

Front cover: Miss America, 2019, by Henry Bermudez (Courtesy of the artist)