Barbara Bullock

Fearless Vision

WoodmereArtMuseumFearless Vision Barbara Bullock

CONTENTS

Foreword 4 by William

R. ValerioA Conversation with Lowery Stokes Sims, Leslie King Hammond, William R. Valerio, and Barbara Bullock 12

A Conversation about Art, Community, and Teaching with Barbara Bullock, Diane Pieri, and Hildy Tow 46

Where People Grow, Like Flowers: The Jasmine Gardens of Barbara Bullock 76 by Tess Wei

The Inspiration of Barbara Bullock 84 by Elbrite Brown

Selected

88 Works

102

Water Spirit for Yemaja, 1997

(Collection of Lewis Tanner Moore)

Water Spirit for Yemaja, 1997

(Collection of Lewis Tanner Moore)

Support for Barbara Bullock: Fearless Vision is provided by The Edna Wright Andrade Fund of the Philadelphia Foundation, the William M. King Charitable Foundation, Robert and Frances Kohler, the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African American Art, the Dorothy J. del Bueno Endowed Exhibition Fund at Woodmere, the Nixon Family on the behalf of James V. Nixon, Jr., and other generous contributors, including those who wish to remain anonymous. Woodmere thanks the Lomax family and WURD, who are the exhibition’s media partners.

DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD

One of the privileges that comes with being on the staff at Woodmere, a museum dedicated to the arts of Philadelphia, is to constantly work with the artists of our community. We have built many longterm relationships with artists, but are especially grateful for the bond we share with Barbara Bullock. Together, we have organized exhibitions, presented public programs and lectures, made podcast episodes and videos, and offered hands-on art projects to museum visitors and schoolchildren alike. Bullock is rightly revered in Philadelphia as a queen in the art world, and like so many others, we bow to her gentle directness and diva-like strength. Our show’s title, Barbara Bullock: Fearless Vision, comes from a conversation, transcribed in this catalogue, between Bullock and distinguished scholars and curators Leslie King Hammond and Lowery Stokes Sims, who are similarly humbled by the power of the artist’s work.

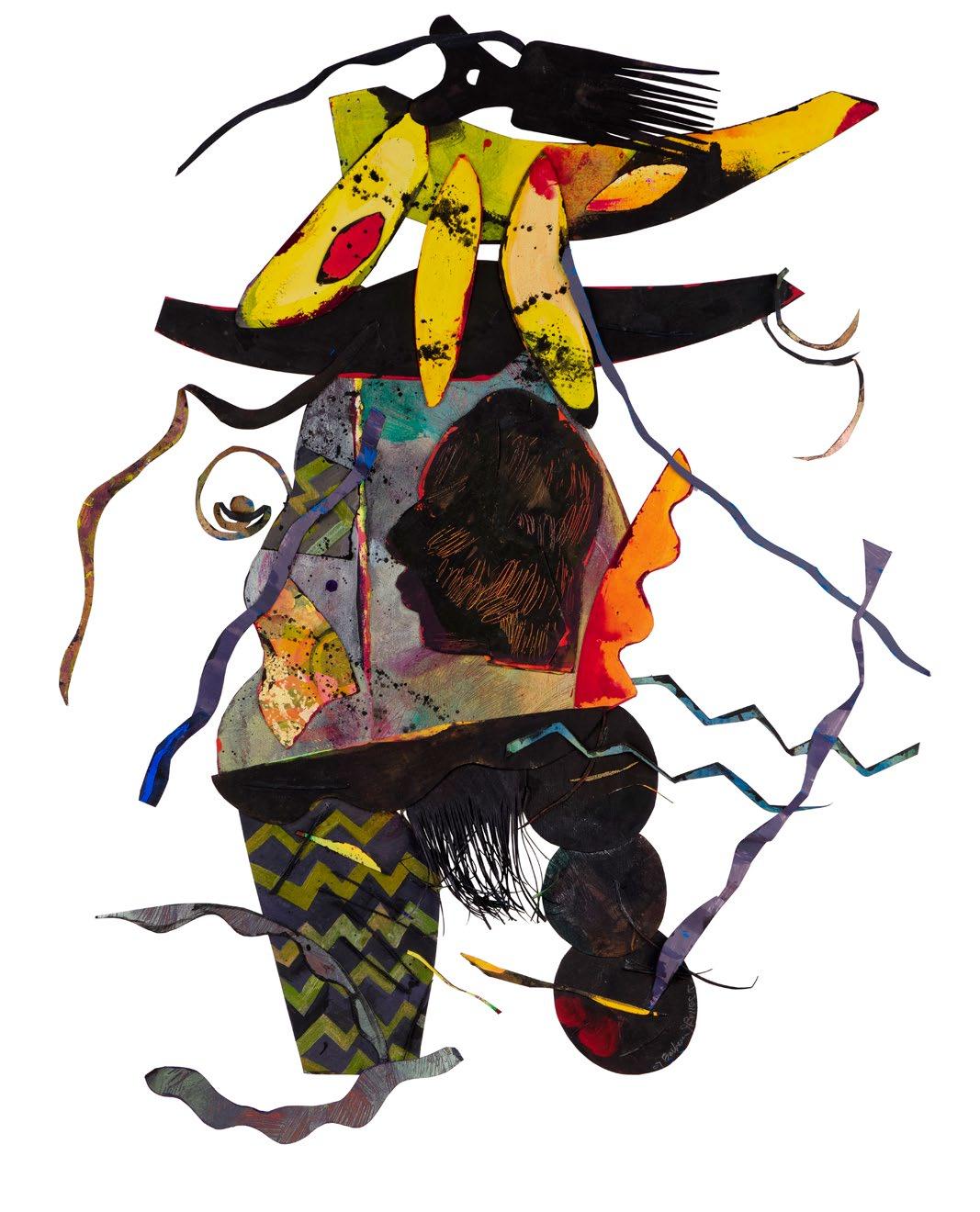

Bullock’s art is unique for its many distinctive qualities. An artist who cannot be confined by the four edges of a rectangular tableau, Bullock makes dynamic wall sculptures in cut, folded, twisted, curled, and gesturally painted paper that navigate an ever-shifting conversation between figuration and abstraction, painting and sculpture. Her unique approach to color is integrated into her collage-based process: elements with bright, primary hues are juxtaposed and made to glow against deep, dark blacks, or fiery yellows and oranges. At the same time, gestural applications of flowing color create nuanced, even rainbowlike color mixing. Complex patterns, sinuous lines, and intricate shapes seem woven into two- and three-dimensional works as if they are expansive

fabrics. The distinctive iconography and stylistic inspiration of Bullock’s travels across Africa stand out; she often describes to me that to visit Ethiopia is a different experience entirely than to visit Nigeria. Her encounters with cultures and people across the African continent has shaped her approach to depicting the human figure and its movement, dancing, carrying of weight, healing, and love making. The work is also nourished by African dance as practiced in Philadelphia, and Bullock’s defining relationship with dancer Arthur Hall. Similarly important was her friendship and admiration for the work of her peers, including Twins Seven Seven, Charles Searles, Ellen Powell Tiberino, Moe Brooker, Martha Jackson Jarvis, and many others. A main point of our exhibition is that Bullock’s work is entirely satisfying and incomparable in its fearless beauty and directness of vision. It also conveys an embrace of African inspiration that not only compels, but also expresses a firm knowledge of an unbroken African lineage that persists across time despite the history of slavery and discrimination.

An aspect of Bullock’s studio practice going back to the 1960s and central to the thesis of our exhibition is that she has always embraced art as a force of active social agency in shaping people’s lives. The artist rejects the notion of paintings and sculptures as objects of passive contemplation. Instead, like the art she encountered firsthand in Africa, or the works she came to know in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (now the Penn Museum), Bullock makes objects that are active and dynamic, literally reaching out to viewers, leaping off walls. Her work sometimes performs

functions in classrooms and community spaces, having been designed to show the process behind a hands-on project. These are mirrors, theaters, houses, puppets, figurative forms, gameboards and game pieces, boxes for secret letters, containers for messages, pop-up books, and more. As demonstrated in the archive of lesson plans Bullock has graciously entrusted to Woodmere, there is a professional educator’s sense of project design and intentionality when it comes to inputs and outcomes. All of this encourages dialogues that are as social as they are personal. I have counted more than two hundred distinct residencies, workshops, community projects, and teaching jobs on Bullock’s CV, and it is not hard to see that this rich history

of making art with others, especially children, cross-inspires to the vocabulary of her studio work. Standing together in front of her wonderful Water Bearers, she described the pure joy of depicting the sun as children so often do: a big yellow circle with rays like the petals of a sunflower. Subjects invented for projects with children with characters like cats, snakes, and spiders also find their way into works made for galleries, collectors’ homes, and museums. Bullock has sometimes incorporated specific parts of objects, or complete works made for the classroom, in her studio work if doing so has proven an expedient way to move a project along. I know many artists who have worked as teachers and make a real difference in their students’ lives.

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION 5 The Origin of Regina, 2022 (Collection of the artist)

Bullock does that and more by creating a unique flow of energy that fortifies her own practice and everyone else who is touched in the process. Bullock has brought creativity and the vitality of world cultures into the lives of generations of people across our region, many of whom might not have had access to the arts. While doing this, she has also built a body of work in the studio that expresses deep emotions, curiosity, joy, and pride in Blackness.

Finally, for an artist whose primary medium is paper, it is surprising that Bullock’s drawings have received little attention. And so, as encouraged by our mutual friend Lewis Tanner Moore, a unique

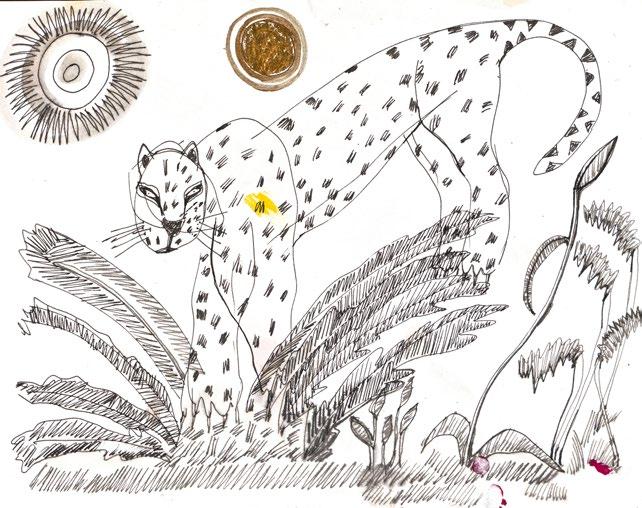

contribution of our exhibition is the inclusion of numerous drawings. Some of these works document the encounters of a world traveler, while others are diagrams for classroom projects. A large portion of Bullock’s drawings are figurative subjects like dancers in motion and lovers intertwined, usually rendered in gestural lines of ink, pencil, and watercolor. It is thrilling to show Bullock’s monumental Black Panther, a central element in her large Bitches Brew installation of 2014, and even more exciting to show it together with the many related drawings of panthers and leopards that bridge the journey from study and observation to imagination and expression.

Barbara Bullock: Fearless Vision is truly a labor of love for everyone at Woodmere, and we are grateful to the generous donors who have made our exhibition and this catalogue possible. Rob Kohler and his late wife Frances Kohler have been instrumental in helping us build a strong representation of Bullock’s work in our collection. Rob is also a generous funder of the exhibition. With the leadership of Jim Petrucci and Claudia Volpe at the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African American Art, that organization has become a true partner to Woodmere in this exhibition, and in other projects grounded in a shared commitment to exploring the work of African American artists.

The Edna Wright Andrade Fund of the Philadelphia Foundation stepped in with generous support in the spirit of its founder, Edna Andrade. Like Bullock, Andrade was one of the great artists of our city. We are equally grateful to Theresa and Lamont King as well as Mira Zergani at the William M. King Charitable Foundation, whose support is particularly important as we build audience and engage our visitors with public programs, lectures, and music events that are so much a part of Bullock’s work. We thank our wonderful, late trustee Dorothy J. Del Bueno for creating the Dorothy J. del Bueno Endowed Exhibition Fund at Woodmere, which provides invaluable support we

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION

count on for exhibitions, year in and year out. I recall that Bullock’s work initially stretched Dorothy’s understanding of contemporary art, but she soon became an ardent champion of the artist. People grow through art, as did Dorothy. The Lomax family and WURD are media partners for the exhibition, and we are deeply grateful for the collaborative spirit and shared understanding of Bullock’s

importance and the priority to engage community, both locally and nationally. And finally, it means a great deal that Jennifer Nixon and the Nixon family have not only made a financial contribution, but also made the gift of an important work of art, Bitches Brew (2014), in honor of Bullock and on the behalf of our late friend James V. Nixon, Jr. Jim was a visionary collector and will always be an angel in

the Woodmere universe. He became like a son—an advisor and often personal driver—to the artist, and we are thrilled to celebrate their special friendship.

Judy Heggestad and Lewis Tanner Moore have been friends to Woodmere in so many ways, and, in addition to lending generously to the show, they are long-term advocates for Bullock’s unique importance in American art. We are also grateful to Elaine Finkelstein, who has once again been generous in honoring our request to borrow her exceptional Healer (1994) for the show. We are thrilled to know that it is a promised gift to the Museum’s collection. Woodmere’s friends and longtime collaborative partners Klare Scarborough and Andrea Packard each helped us in many ways. Everything about Woodmere’s exhibition builds on their excellent exhibitions and catalogues: Klare’s Barbara Bullock: Chasing After Spirits at the La Salle University Art Museum in 2016 and Andrea’s Ubiquitous Presence: Selected Works by Barbara Bullock at the List Gallery at Swarthmore College in 2022.

Thanks also to Leslie King Hammond, Lowery Stokes Sims, and Diane Pieri, our thought partners

and participants in the conversations with Bullock that are transcribed in this catalogue. Tess Wei, whose work at the List Gallery at Swarthmore College we admire, became a special partner in helping us organize our show. Woodmere’s staff has shined bright as always, and I must recognize the Deputy Director of Exhibitions Rick Ortwein, Associate Curator Rachel Hruszkewycz, and Registrar Laura Heemer for conceiving, planning, and implementing the show. With our purpose being so grounded in education, special appreciation goes to Hildy Tow, the Robert L. McNeil Jr. Curator of Education. More than any other staff member, she gave shape to all aspects of the presentation. And finally, Woodmere is indebted to Barbara Bullock herself. This exhibition could not have happened without her direct participation, and every step in the journey has been beautiful and revelatory. Woodmere is honored, and as director I extend the museum’s sincere gratitude.

WILLIAM R. VALERIO, PHD

The Patricia Van Burgh Allison Director and Chief Executive Officer

A Conversation with Barbara Bullock, Lowery Stokes Sims, and Leslie King Hammond

A CONVERSATION WITH BARBARA BULLOCK, LOWERY STOKES SIMS, AND LESLIE KING HAMMOND

On May 12, 2023, Woodmere Director William Valerio and independent art historians and curators Lowery Stokes Sims and Leslie King Hammond joined Barbara Bullock in her studio to discuss her work.

WILLIAM VALERIO: Barbara, I’m honored to be here today in your studio, with Lowery Stokes Sims and Leslie King Hammond and excited about the exhibition of your work coming up at Woodmere. This will be a career-spanning show that focuses on the crossover between your work in the studio and your work in the community. You’ve been a socially active artist your entire career, bringing art into classrooms and community centers, and you’re the first I know to have brought art into prisons. In the 1970s, you were the founding director of the art program at the Ile Ife Black Humanitarian Center and in the 1980s, you became the leader of the Germantown Workshop of Prints in Progress. I’m grateful to you, Leslie and Lowery, for being here today to talk with Barbara about her history, which needs to be shared.

LOWERY STOKES SIMS: Bill, that’s a wonderful introduction to what I believe is going to be a really critical conversation. Barbara, this show is going to cover six decades, so I’d like to start by understanding your formative period. What was your life like growing up?

BARBARA BULLOCK: I was born in North Philadelphia. I lived with my mother, my brother, Jack, and my sister, Delores at 1908 North Newkirk Street. It was a great community. I still think about it and I dream about it, although the house that I

lived in is gone. I went to Blaine Elementary School. I always felt like I was creative. I was constantly looking at people, trying to understand them and who they were.

I don’t really talk about elementary school, to be honest with you. I just couldn’t stay in school. I knew that I was different—I had this sort of excitement about life. I felt like I was the only one in the school that had that kind of excitement. One time, in second or third grade, we were all in the auditorium, watching Little Red Riding Hood. I got extremely excited and I jumped up on the seat. So I was told to leave the auditorium. That happened a lot. I just always felt that you were supposed to express yourself.

There were other things that happened. I had a friend in elementary school. He had little red freckles all over and we would play in the schoolyard constantly.

I was a ballet dancer, he was—I forget what, some kind of cowboy or something. One day after school, his father came up to me and said, Barbara, I’m taking you and my son to get an ice cream cone. He buys the ice cream cone and he hands one to his son, and then I noticed mine was melting in his hand. He was like, listen, if you promise not to play with my son, you can have this ice cream.

So I looked at the ice cream cone. I was like, look, I’ll take the ice cream cone because I knew we were going to be playing together anyway. [LAUGHS]

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION 13

Healing Feeling, 1998 (Woodmere Art Museum: Museum purchase with funds generously provided by Frances and Robert Kohler, 2020)

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION 13

Healing Feeling, 1998 (Woodmere Art Museum: Museum purchase with funds generously provided by Frances and Robert Kohler, 2020)

14 WOODMERE ART MUSEUM

Trayvon Martin, Most Precious Blood, 2013–14 (Woodmere Art Museum: Museum purchase, 2014)

14 WOODMERE ART MUSEUM

Trayvon Martin, Most Precious Blood, 2013–14 (Woodmere Art Museum: Museum purchase, 2014)

VALERIO: This father didn’t matter.

BULLOCK: Things like that you realize in life. Being a child, things like that constantly happen. People say things to you. I spent a lot of my childhood during the summer in the South with my grandmother and grandfather.

LESLIE KING HAMMOND: What part of the South?

BULLOCK: In North Carolina, and in Norfolk, Virginia. My grandfather was a freed man. His father was a slave. He worked in the mines. There was a mine cave-in, and he had a brain injury. He would tell me things he saw. I would see them too. We would see birds in the sky and I would say what color they were. My grandmother told me that she had lost a child—she had, I think, eleven children— and she said, without a doubt, I was the child that she lost.

KING HAMMOND: Coming back?

BULLOCK: Right, coming back. Her oldest daughter believed it too. I felt like it could explain some things, because I had this thing about looking at people constantly and just seeing different things. I loved to write—I wasn’t actually writing, I was scribbling, but I felt like it was beautiful. When I was in the third grade, the teacher would come around and she would put these little gold stars on everybody’s homework. She would usually just look at me and . . . [LAUGHS]

One day, she put a star on my paper. I knew I was in trouble. But she had this tutor and the tutor came and took me out of class. She said, I’m going to teach you how to write and how to read. I was like, no, I’m not going to read. This is the way I like to

write. But within the week, I started writing for her. I said, if that’s what you wanted, you should have said so. So I had always just this thing about being different and knowing it.

KING HAMMOND: That was the time of the Great Migration—lots of Black families moved from the South to the North, coming from rural areas to northern urban areas. In your elementary school, how many Black students were there? Were you an “only” or a “first?”

BULLOCK: No, there was a mixture.

KING HAMMOND: Did you have a lot of interaction with other students?

BULLOCK: Definitely. But I think the other thing was you realized that you were poor. There were a lot of things you couldn’t do, you couldn’t afford. Every year at school there was a festival with rides and candy. We didn’t have much money so I would go to the festival and look on the ground for lost tickets. That’s how I got on the rides. There was a public housing project across the street, and Ridge Avenue was very close. But the community was so different from the way things are now. We had a dog named Icky. He slept in the street, and the cars drove around him. He would have been a pancake today. When there was a funeral, which was always held in the family’s home, we as children would go and knock on the door and tell everybody we were so sorry.

VALERIO: Barbara, you attended the Most Precious Blood Roman Catholic Church, is that right? I know that’s figured in the title of one of your works, Trayvon Martin, Most Precious Blood. The church was unfortunately demolished recently.

BULLOCK: Yes. We went to Catholic school in the summer. I was really afraid of the nuns. The nuns didn’t like me either. [LAUGHS] But one Easter, we were all searching for Easter eggs. Everybody’s out there, you have your little black patent leather shoes and your black patent leather pocketbook. I found an egg. The nun came to me and said, so Barbara, how many eggs do you have? I had a little mirror in my pocketbook, so it made it look like I had two eggs. I said two. She says, you’re getting one. So she took the egg out. [LAUGHS]

KING HAMMOND: What were the nuns like? Aside from the egg incident.

BULLOCK: They were very strict. At that time, they could hit you with a ruler.

KING HAMMOND: How many times did you get hit?

BULLOCK: Oh, so many times. [LAUGHS] I don’t have a very clear memory of that time. But I remember the name of the church. Years later, I fell in love with the names of churches. Most Precious Blood—I thought of that name when all the brothers were being shot in the street. It happened in front of me a couple of times. I remember the mothers and thinking, God, that’s their most precious blood.

STOKES SIMS: You have a brother and sister also?

BULLOCK: Yes. My brother was always a mystery to me. He was nomadic and I loved and admired him. He passed away in the pandemic. My sister wanted to be an actress and she wrote stories and has a wonderful singing voice.

KING HAMMOND: With all the scribblings in school and being slightly rebellious and different, when did you get a sense that you were an artist?

like in the Black communities, where you had painting and drawing. So I was always being creative.

I also wanted to be a dancer. I hadn’t seen African dancing yet and at first I wanted to be a ballet dancer. Two weeks after taking my first class, I bought a pair of toe slippers. I put them on and tried to stand up, and that was the end of that. No way. No, we’re not doing this. [LAUGHS]

STOKES SIMS: Did you see any ballets when you were a kid?

BULLOCK: Yes, we did. We saw a lot of dance.

KING HAMMOND: Did you get to go to the theater?

BULLOCK: As a child, you’re always drawing, you’re always creative. I remember one time when I was about eight years old, I had made a school out of paper and little paper cutouts of children, teachers, and desks. Because I was having a hard time in school, I made up stories. In one, I was the favorite student in the school and the paper teachers would come and get me to teach the other children.

KING HAMMOND: It was probably the first time you recognized the power of a creative act. Even though your teachers were dismissive, you held on to the fact that you were a maker.

BULLOCK: In the school system back then, art was part of the curriculum. They had clubs after school, so you were always doing art. Then we had centers,

BULLOCK: Not the theater, but it was dance that made the difference in my life as I got older. The first very serious dancer I knew was Arthur Hall and the Afro-American Dance Ensemble in North Philadelphia. That would have been in the early 1960s. We had [Babatunde] Olatunji, we had Ossie Davis and his wife Ruby Dee. We had jazz musicians. We had photography and printmaking. Everyone came through. It was like a mecca.

I led the art department at Ile Ife, the studio and school Hall founded. We had an excellent group of artists. We had Charles Searles and Winnie Owens. Winnie was a very strong person. She said if anyone called clay “mud” that she was going to punch them. [LAUGHS]

She worked there for a while and then she went to Howard University. And then Martha Jackson Jarvis came. She would sit down on the ground and talk to children about what they were doing. She was the kind of person that worked naturally with children. The way she worked with the children was just amazing. All of our students were Black

children. We would have them draw their parents’ faces. Some of them would draw this outline and they would draw blonde hair, and it was like, OK, everybody just stop for a minute. What does your mother really look like? I want you to look at her hair, and you’re going to draw so that when we see this portrait, we’re going to know her when we see her. And so they did. They started using black, brown, and beige colors, and they did the hair. Charles and I were constantly painting and drawing and showing them.

STOKES SIMS: So where did you go to art school?

BULLOCK: I went to Hussian School of Art, which was basically a commercial school. That was the school I could afford to go to, because I was always working. I would have two and three jobs and then I would go to school at night.

KING HAMMOND: Black women artists of your age found that when they sought to become an artist, their families would ask, how are you going to support yourself? Many were able to earn degrees in education or commercial art. Was that your idea to have a job and keep your mother happy, or did you really like commercial art?

BULLOCK: Really, I didn’t think that way. Hussian School of Art was a school that I could afford to go to. I realized while I was there that pretty much everybody else was on the GI Bill, but I wasn’t. When they asked us to sketch Michelangelo’s David statue, I made him African American.

VALERIO: Now that’s something we need for the show!

BULLOCK: It’s long gone, but it was during this time that I met John Simpson and Richard Watson. I was on my way home from Hussian School of Art,

and I was walking toward the subway and City Hall, and here come these guys. John loved women, and so he came up to me and he was like, you know, I’ve been watching you and I would like to draw you. I was like, I’m an artist myself. He said, well, we’re on our way to the studio and we want you to come with us. I was like, sure. After that day, we were always together. I was so fortunate to meet them. We would have these conversations, from 10:00 at night to 3:00 in the morning about being Black artists. They had all graduated from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and they

were constantly talking about how it was so great, what they had learned, but now they had to find themselves.

We talked about whether we wanted to be known as Black artists or just as artists. We talked about our struggle and were constantly in conversation. At that time, it was so urgent—because we couldn’t exhibit anywhere.

KING HAMMOND: This was the 1960s, right?

BULLOCK: Yes. We found some recreation centers, and there were people in New York who opened

their homes for our shows. Every month, we would try to have exhibitions. That was also when we had the National Conference of Artists—we had many people who would come into the group, like younger artists. I felt like these were the people I understood, when I would look at their work and how strong it was. They constantly talked to me about trying to get into another art school. They said, we want you. We’re going to teach you. We’re going to tutor you. We just want you to be yourself and just never, ever do anything that someone asks you to do. I was happy to do that.

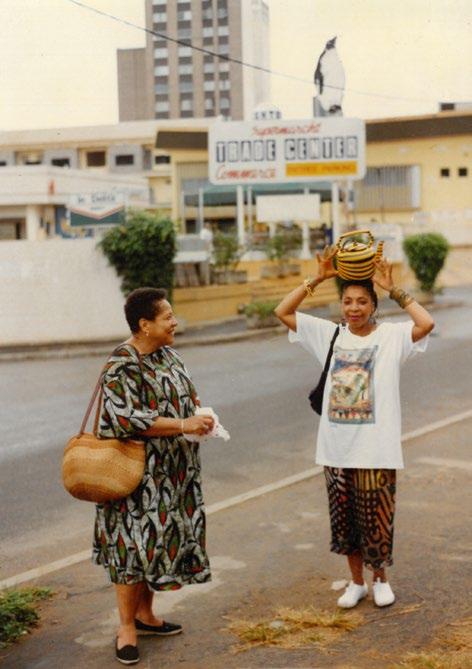

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION 19 Untitled (Ethiopia), 1998 (Collection of the artist)KING HAMMOND: You were blessed. That was a very rich period of Black nationalist awakening with the beginning of the Black Arts movement. Those artists you first met were at the forefront in the Philadelphia region. I often say that Jacob Lawrence was educated in the “University of Harlem.” Barbara, you were educated in the “University of Philadelphia,” in those inspired communities and workshops who recognized your artistic capacity. This becomes a really pivotal moment in your development that I don’t think people are aware of—in terms of the narrative that’s going to be presented in your Woodmere retrospective. This is so important!

Historically, in the beginning of the migration, as these artists moved North, many of them could not go to schools of art for training. Augusta Savage was able to attend Cooper Union. William Henry Johnson studied at the National Academy of Design. But they were the “only onlys.” Later Columbia University’s programs opened up. And in between that time, there was the WPA experience.

Many of those artists who did have access and privilege came out of those educational systems to teach other artists. They would convene meetings and artists gatherings, similar to what you and Jacob experienced, in the Harlem art workshops. You are much like the Jacob Lawrence of Philadelphia.

BULLOCK: Do you remember Ellen Powell Tiberino?

KING HAMMOND: Yes, I remember Ellen Powell Tiberino.

BULLOCK: All of us were able to, as you said, commune. Those were the people we worked with. So you had—it was absolutely strong.

STOKES SIMS: You have all these people supporting you, providing input, examples. Tell us about your style, how it developed over the years, and how you reached all these different possibilities of abstraction and figuration.

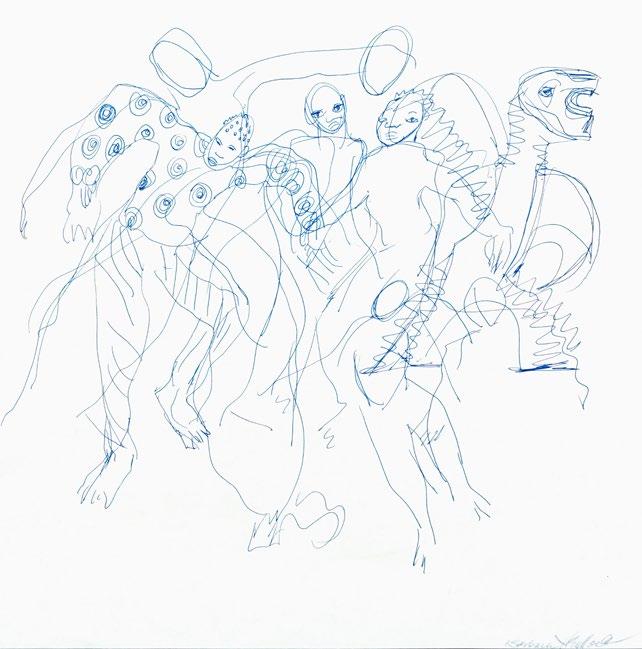

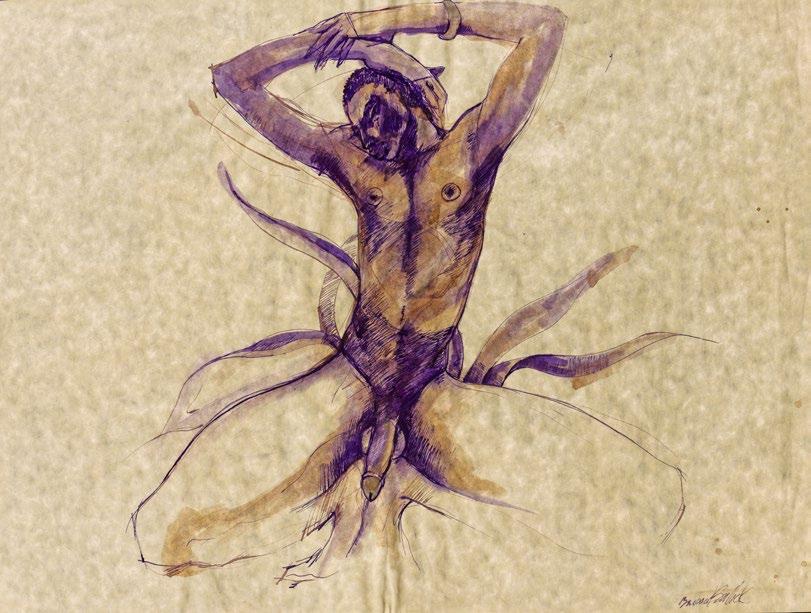

BULLOCK: I started out more figurative because, basically, you just naturally do that for portraits. Because I worked with a lot of dancers and musicians, I began to draw dancers constantly. Dancers are amazing—what they do with their bodies and their energy. I began to draw on my own, without models, knowing that it had to be right because I was always working with them.

KING HAMMOND: So you were interested in capturing motion and movement?

BULLOCK: Movement, definitely. You do a lot of drawing before you begin to paint because it’s sort of like a fear there when you see the painting. It’s like, God, can I really do this? I had hundreds of drawings hidden all over the place. At one of my jobs, they found the drawings. They didn’t fire me, though.

KING HAMMOND: This is in an office building?

BULLOCK: No, this is in a regular home. I did everything—I would babysit and I was a private cook—in order to survive. I didn’t want the kind of job where there was a boss telling me what to do, so that kind of work was easiest. Mentally, I could think about art because everything else was simple to do.

VALERIO: Barbara, did you ever exhibit at the Pyramid Club? I think of it as an important exhibition venue. Humbert Howard organized the gallery program there. Did you know him?

BULLOCK: Yes, I knew Humbert Howard. But that’s almost a different universe. You know why? Because

that had to do with color. You had to pass the paper bag test.

KING HAMMOND: Oh yes, you had to be a certain complexion. They put a paper bag on the door to an event and if you were darker than the bag, you could not gain admission. This was an act of intracultural racism.

VALERIO: Oh, I didn’t know about this.

KING HAMMOND: Barbara, we understand why this is hard for you because you lived it and experienced it. Having been bounced out of classrooms, workshops, and other situations, you understood racial biases within your own culture. Being denied

entry to Black art salons and private clubs takes on a different level of pain and dismissiveness. This was a very active process of classist discrimination within privileged communities of Black people stemming from old line plantation politics.

BULLOCK: I remember my parents talked about that all the time.

STOKES SIMS: Do you think they didn’t take you as seriously because you were a woman?

BULLOCK: Oh, always. Yes. But I really didn’t pay much attention to that. I was really close to Ellen Powell Tiberino. I remember visiting her, and she showed me a drawer of her drawings. She said that

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION 21 The Cock Crows, 1988, by Ellen Powell Tiberino (Woodmere Art Museum: Gift of Jason Friedland, Andrew Eisenstein, and Matthew Canno, 2023)

it was painful for her to draw. I felt she was speaking emotionally about her work. She was a very strong artist. She was speaking about the spiritual pain of creativity.

KING HAMMOND: I went to see her toward the end of her illness because the African American Museum was considering an exhibition. I was so torn by her condition. That was the hardest thing I have ever experienced in working with an artist. I could see and feel her pain. It was hard for her, and hard for me—it was a life lesson that I had to learn, how to deal with artists navigating their health and their artmaking processes. It’s good to know that you knew her.

BULLOCK: Oh yeah. In fact, when she passed, her husband said, I want you to be one of the pallbearers. I said, yes, I will be one of the pallbearers. I remember that I couldn’t believe that

Dancers, c. 1985 (Collection of the artist)

Ellen was leaving. I worried about what was going to happen to her work. I still worry.

VALERIO: We have about fifteen works by Ellen Powell Tiberino at Woodmere, and each one is deeply felt. A colorful pastel of a white rooster crowing at dawn, for example, represents her husband, Joseph Tiberino. I’m told by one of their children that she was ill at the time and imagining the future, thinking ahead to her husband’s life after her own death. The rooster’s shadow and the red markings of the sun are intense. There’s also the intensity of the social context that needs to be explored. She was one of the main cultural voices in the MOVE resistance in West Philly.

KING HAMMOND: Absolutely.

STOKES SIMS: Now I want to move on to something else: travel. Barbara, what were your first journeys abroad?

BULLOCK: The first place I went to was Egypt. I thought that should be the first place. I brought sketchbooks with me, I was going to draw, but everything you see in Egypt I felt has been drawn already. I couldn’t do anything that would be original.

STOKES SIMS: When was that approximately? Was that the 1960s or the 1970s?

BULLOCK: 1970s. When we were on the Nile, I choreographed a dance. We won the contest and they gave us a bottle of wine. [LAUGHS]

But it was a wonderful trip. All I wanted to do is be in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo—oh my god, we would go there every day, basically. The next place I went was Morocco. I went with a friend and that was amazing too.

We decided that since no one could tell us what to do, we could do whatever we wanted to do. When we got there, put our things in the room, put up anything like money or what we had to put away, and walked out in the street. Then down the street came hundreds of guys. Hundreds of guys came running, and we ran back into the hotel.

We told the people in the hotel what had happened and they said, just touch one or two, and the others will just go away. And that’s what happened. We just pulled one guy, and everybody else left. So it was like, that’s how they got jobs, taking people around. But it was hundreds. It was raining men, you know?

We went to all the bazaars, and we went to this one restaurant, and we met the owner. He said we should stay there for a while, so we said OK. But it was wonderful. We were so naive at that point. But the one guy had a friend who was a soldier. We

were like, well this is different really. What are we really doing here?

STOKES SIMS: Sometimes you have those encounters. I had that with a friend in Turkey in the early 1970s. We met these two Turkish students who saw the two of us with these two German guys and said, you’re coming home with us because you don’t know what you’re doing. Now I’m sure the whole neighborhood talked about the two of us women in there with five men, but you know. Anyway, but yeah, it was a much more innocent time.

BULLOCK: Yeah, you really didn’t know the dangers or anything like that.

KING HAMMOND: Were people more protective of you at that time?

BULLOCK: Nowadays they’re not. I know when I really started traveling, when I went to Senegal the first time—I went with a group. I realized that when you travel, you have to know what you’re doing and who you’re traveling with. A lot of times when you’re in a car with a group, and driving somewhere, you want to stop and see something that looks interesting. But it’s impossible. They say no, we can’t get off the road. So I decided that I would start traveling by myself. So the next time I went to Senegal, I went by myself. I just wanted to travel all over Africa.

The next few places I went, I only had $30 once I got there. So that meant I ate all the food I wasn’t supposed to eat. I never got sick. I drank all the water I wasn’t supposed to drink. This friend and I, we cooked fish on the beach, and we cooked fish for children. We had crowds of children, and were cooking for them, and they were bringing us tea. It was just amazing. He also had me read by a diviner.

Remembrance, 1985, from the series Initiation (Woodmere Art Museum: Partial gift of the artist and museum purchase with funds generously provided by Robert Kohler, Osagie Imasogie, and Jim Nixon, 2020)

KING HAMMOND: What did the diviner tell you? Was this in Senegal?

BULLOCK: In Senegal. They had a lean-to. You had to get down and crawl in it. And when he was reading the stones and the bones, it all came out that when I got home, I would be selling African sculpture and artifacts when I finished my journey.

We went into the country to visit a farm and met these women who were so dark and beautiful. I have never seen anything as beautiful. I couldn’t take my eyes off them. They had an aura. Their voices were like bells. When I spoke to them, they just laughed.

I ate with the men, which is unusual. We ate out of this big bowl, and they told me to use a particular hand—

STOKES SIMS: I think it’s your left hand.

BULLOCK: Yes, that’s the answer. They tell you to wash your hands before you eat. There were five of them, and we’re just eating. They talked to me about farming in Africa. They said that the tools they were using were so old, and they needed to get better tools—good farming tools. Basically they were farming by hand. We went to another area in Senegal, way up country, where it was all Arabic. But all these things I was able to do is because of a man I met named Mustapha. He made sure we went to Gorée Island. Gorée Island, off the coast of Senegal, known as “the door of no return” in the slave trade. Gorée Island is an emotional experience and feels sacred.

KING HAMMOND: Changing topics, inquiring minds want to know: were there any significant relationships that impacted your work, your life,

even though you didn’t get married? You observed that so many women artists had trouble being married that you decided not to get married so you could do your art. You don’t have to give details.

BULLOCK: Yes, there were several. All my life I wanted friends and I felt like friendship lasts so much longer than marriages and all that. Knowing Charles and all of them, it was like being around these guys that this is what they did. Art was their life. But they were married, and their wives were cooking and doing all the other stuff. I was like, you know what? I’m not getting married. I am going to be an artist. I want to know who I am. I don’t want someone to tell me who I am.

So when someone would ask to get married, I felt insulted. Like we were good friends, why would you mess that up, you know? I really felt that way. I know my mother, she never even thought that I would get married, but she never asked, she never pushed me to. She really wanted me to tell her everything that I did, though. She was like that. I was lucky, you know? She didn’t say I was wrong or anything.

STOKES SIMS: She was protecting you.

BULLOCK: She was protecting me and then she would tell me about her life, so—

STOKES SIMS: I think many of us had that experience, where our mothers would complain about their own partners, but assured us that it would be different for us. But I am interested to know, is it true that you knew Twins Seven Seven?

BULLOCK: Yes.

STOKES SIMS: How did you meet him?

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION

BULLOCK: Twins Seven Seven came to Model Cities and Ile Ife, where I was working at the time. He came to the art department, and explained to Charles and me that he was an artist, and a musician, and a dancer. He went on and on, and we were like, how do you have time to do work? My God. But when we saw his work, it was like another world, just extraordinary. The forms and the

meanings—you could look at it for forever and you’d still never see everything in it. He was Yoruba. So there were a lot of spirits in his work.

VALERIO: The show we did at Woodmere in 2020, Africa in the Arts of Philadelphia, brought together your work with that of Charles and Twins. It was an amazing “conversation” of artists.

KING HAMMOND: How did that impact you spiritually? Did it change your work?

BULLOCK: Well, it was the whole thing, that you can paint spirits. You can draw spirits, you know? And it’s that whole thing of the freedom of your belief, you know? He would talk about the forest in his work, and about the magicians. I was just so inspired, deeply inspired, and just really loving what he did. And I just knew it was going to change me.

STOKES SIMS: Looking back on it, did you see your travels in Africa, your contact with Twins Seven Seven as a way for you to get in touch with your ancestral heritage? How did that begin to appear in your work?

BULLOCK: I did a lot of research. I love to do research. It gave me answers, you know? I was always influenced by life, by the people I met, and their homes. And I know that the people who really influenced me were people I had to remember. I remember that with my grandmother in the South, when she cooked, all her daughters were cooking with her. They were all married. They all lived in the South in different places. But they would come together on a Sunday, and they would just cook everything. And I would just listen to them speaking while they were cooking. Looking at them and listening to their conversations was like experiencing a celebration of females.

I would look at the dishes, and a lot of the dishes were cracked. And I was influenced by that. The kitchen was just the most wonderful part of the house. That whole communal thing. When I was really young, I remember my grandmother and all of them cooking fried chicken, stewed chicken, sweet potato pudding—they cooked everything.

Then they would take us into the living room, and everybody would have to grab a chair, and then they would pray. They would say prayers. And I was like, we need to go in the kitchen and eat, you know? They were long prayers—I mean, we were thankful about a lot of things.

STOKES SIMS: But in terms of your style, how did you develop that? There are certain things that are very distinctive about your work. The decorative surfaces. You have this way of doing these razorsharp edges, and using this heavy paper. How did that all come together for you?

BULLOCK: Well, I love paper, and the fact that people make paper. In the beginning, I was working figuratively, and I was working with gouache. And I felt like I was doing what everybody else was doing. I didn’t want to do what anybody else was doing.

So I started working on a piece that had to do with a dancer. I got up early in the morning and cut it up and put it back together again, and put it together in a different way. That was Animal Healer

I felt like, this is really what I want to do. I had to figure out how to do something that would speak for me. It’s like that language that you’re looking for. And it’s not only with figures, with faces, it’s with your materials. You’re respecting your materials and changing them at the same time.

Working with 300 lb. watercolor paper, I would layer constantly five layers on the top, five layers on the other side. And then it feels like it’s something—like it’s real. And I started moving it and shaping it. In the beginning, it amazed me that it would keep its shape. And I knew how to do that, but it was still a lot of work.

When you’re working on something, you’re changing it. In other words, when I’m painting, I’m never going to paint exactly what I want to shape out. That’s impossible. So the painting is, in itself, totally different. And it’s really so wonderful just to mix these forms and shapes while you’re painting. But I don’t know what I’m doing sometimes. So I’m just going to keep painting and discovering and experimenting. I started using fabric paints, with acrylics, and oil paints, and they would just do all these amazing things. When I wake up in the morning, I feel like I really want to experiment more.

STOKES SIMS: Have you ever physically made paper?

BULLOCK: Yes, I had a couple of friends who made paper. We did that with children too.

STOKES SIMS: I look around your studio and I say, it’s almost like occasionally this sculpture is trying to come out. And you sort of go back and forth between the flat surface and the sculptural surface. I’m really intrigued by how prominent black is in your work.

BULLOCK: At one point in time, I was only going to paint with black. I knew how to use other colors,

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION 29

Animal Healer, 1990, from the series Healer (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia: The Harold A. and Ann R. Sorgenti Collection of Contemporary African American Art, 2004.20.12) © Barbara Bullock

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION 29

Animal Healer, 1990, from the series Healer (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia: The Harold A. and Ann R. Sorgenti Collection of Contemporary African American Art, 2004.20.12) © Barbara Bullock

too, but I only paint with black. There was always a negativity that was given to it, you know? It’s just the most powerful color. I was talking to my late friend, A. M. Weaver, the curator and writer, and we would talk about a lot of things and she would just say, you know, when you cut these thin strips, it’s almost like you’re drawing. When you let them hang, it’s like a continuum.

I started painting black birds, black cats, Black people, black houses. And I said, you know what? I’m going to use a little bit of yellow in here. I’ll just use a little bit of yellow. And I would add some—I would use yellow first, and then I’d add green and red, and then put that black on there, and it’s just beautiful.

KING HAMMOND: Black is the composite amalgam of the entire spectrum of colors.

STOKES SIMS: What kind of paints do you use? What brands?

BULLOCK: It’s French—flashe paint. I used it when I did the Philadelphia International Airport project. It was just amazing. I bought about $500 or $600 worth of it—these huge containers. But I also use gouache and acrylics. Charles was like, Barbara, you really need to use acrylic because it dries easily, and you can be spontaneous, or whatever, but that was a decision I had made to really work with black. When I was teaching, the students questioned me, why black? I said, OK, sit down. I will tell y’all why I use black. So I told them, you know, I said, it’s given

such a negative reference. So they understood. But they said, OK, that’s basically the way you feel as a Black woman. So it was—at least they knew that.

STOKES SIMS: The interesting thing is the color black has become such a focal point in the art world because the British painter Anish Kapoor has patented a specific black that he uses. I remember going to see his work once in a gallery, and they were these basalt sculptures. They had little areas of black in them. There was a stele form that had a black hole in it.

I was being a smartass, and I said, I’m going to walk up to that thing real quick and stop just short of putting my nose in the black. The next thing I knew, my head was in the sculpture because that black had no reflective quality. It was the most powerful, palpable experience I had with the color black.

VALERIO: I want to just clarify something, Barbara. The black that we see, like Black Panther, for example, or these black figures, that’s paper that you’ve painted black? Or are you buying paper that’s already dyed black?

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION 31 George Floyd (portrait #7), 2022 (Collection of the artist)

BULLOCK: Oh, God, no. I paint it black.

VALERIO: So all of this is white paper that you’ve painted black?

BULLOCK: Yeah, which takes a lot of layers.

KING HAMMOND: Those portraits that you did during the pandemic, those are also the same white—this white, heavy paper?

BULLOCK: Right. 300 pound.

KING HAMMOND: Now you mix your own black?

BULLOCK: I do. But a lot of times, I paint right from the jar, that flashe paint. It’s water-based. I’ve only used water-based paint for the last thirty or forty years.

I’m thinking about when I made Chasing After Spirits. I thought about history. It’s like chasing after spirits, chasing after the people who have gone before, all the people, everything that has happened, you know? I felt that was a title that was going to cover over a lot of work that I was doing.

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION 33

Used Furniture, 2007, from the series Katrina (Woodmere Art Museum: Museum purchase with funding generously provided by Robert and Frances Kohler, 2023)

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION 33

Used Furniture, 2007, from the series Katrina (Woodmere Art Museum: Museum purchase with funding generously provided by Robert and Frances Kohler, 2023)

And then I remember when Hurricane Katrina happened in Louisiana—I would keep the TV on. And my friend Ife Nii Owoo and I were looking at these people, and I was like, oh my God. I started putting that series together right then and there. It was called the Katrina series. I showed it at Sande Webster’s gallery and some other venues. When they wrote about it, they wrote something totally

different than what I was thinking, but I felt like, OK, that works too, you know?

I think as far as Most Precious Blood went, it was that same thing. It was like working emotionally, which is not always the best way to work. But at times, you have to do that. I was following the trial with Trayvon Martin’s mother watching—and I just

started working with that red. And I remember thinking that it’s a lot of red in life. And that was blood, I felt it was a powerful color.

When I did that piece, it was so personal. I was so glad I did it. But it wasn’t enough. I felt like this is what we can do. We can say how we feel, but how do we really solve problems? What are we as artists doing? That’s my reaction to a lot of things that happen in life, that’s how I work out a lot of the artwork that I do.

KING HAMMOND: You are clearly an artist who developed your own style, craft, and processes by your own invention, vision, instinct, and impulse. Which one of your series do you think was the most challenging? And which ones do you think taught you the most?

BULLOCK: I think—well, the erotic series, let’s face it. I mean, being wise in one way, and vulnerable in another way. I just decided, OK, if you’re going to do an erotic series, you’re going to do the whole thing. You’re not going to leave anything out, you’re not going to leave anybody out, any whatever out. And you’re going to do the research. And so I went to the bookstores, and I went to the back of the bookstore where all the guys were looking at the magazines. [LAUGHS] I even went to bars, you know? The gay bar, they would tell me to leave. It was like, no, I’m doing research. And they’re like, no. You have to leave. In Atlantic City, they asked me to leave.

STOKES SIMS: So you did get thrown out again? [LAUGHS]

BULLOCK: I’m so used to it. It’s like, just don’t let the door hit you in the face. And I have friends who would say, if there’s anything you need to know, just come to us and we’ll show you. I went to the baths

in New York City. And that was—God, that was tiring. I mean, some of us would get tired watching. [LAUGHS]

STOKES SIMS: So when did you do this series? I’m curious. You know, I ask because Al Loving, after he broke from his cubes, he did his drape sculptures. Then he started doing his collage sculptures that were based on the inspiration of the Monet show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. And then he went into an erotic series, with cut paper and shapes. It was kind of like Matisse and Al sort of getting together. You didn’t know about that, though, did you?

BULLOCK: No, I didn’t. But actually, I was inspired by the Japanese. I love what they did with the fabric and the love letters, and everything.

VALERIO: Now, Barbara, you had friends who were gay men in this period, too, who were artists.

BULLOCK: Oh, I had many friends who were gay.

VALERIO: And I think of the gay culture of that time opening up the ideas of sexual freedom and eroticism for the straight world too.

BULLOCK: Well, yes. I was invited to do a lecture, which I really wasn’t ready to do. But it was gay women on one side and gay men on the other side. And they wanted me to show all the photographs of everything. And I would show them, and I talked to them, and they were like, oh, wow, you’re so brave. And I was like, I don’t think about bravery. I think it’s just something that I was inspired to do. And of all the people on the planet, they loved what I was doing. So I was able to talk to them about the different drawings and paintings that I did.

VALERIO: Barbara, with regard to the figure, it’s

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION

fascinating to think about the group of artists who were your colleagues: Ellen Powell Tiberino, Charles Searles, Clarence Morgan, James Brantley. They started out steeped in the realism of the Academy— realism as handed down through the generations from Thomas Eakins. We have that beautiful painting of a boxer by Charles Searles at Woodmere, and I can’t look at it without thinking about Eakins. Did you have greater freedom to explore subjects like the erotic core of life, or your Blackness, or your African heritage because you weren’t weighed down by the Academy and its traditions?

BULLOCK: There are these strange questions that people ask you all the time. Are you a Black artist? Are you an artist? Why do I even have to answer

any of it? That was always my whole thing. And it was like, obviously I’m not a white artist. I mean, I must be a Black artist then. But you know, they use that to explain you, to color and place you.

And to make that separation. Only more recently, I saw something on YouTube where—and I think with the artists in Chicago—that said, there are two arts. There has to be two arts because the way we think about our lives and the things that we want to talk about, we have to talk about our lives. It was so brilliant.

STOKES SIMS: You mean terms of abstraction and figuration? Or in terms of—

BULLOCK: Black people and white people. It’s

like the way we write, the way we think—even in color, you know? I mean, I can remember teaching children who were not allowed to use red. They weren’t allowed to use red and they weren’t allowed to use yellow. And they said, their parents told them that. I was like, look, we have a lot of red. You’re going to have to use that red. You’ve got to use the yellow. You use the colors that you love.

We talked about the palette. The palette was going to be different. It’s totally different, you know? And I remember Charles speaking on that. I didn’t always understand everything he was saying, but he said, our palette is different. And what we have to say is our lives. This is what we have to say. But you put us in this group. Oh, that’s Black art, you know?

It’s so insulting. It doesn’t make sense. I mean, if you look at it even as a child, how could you explain it? What does that mean? What is it about?

We are going to say what we have to say regardless of what we’re told not to do. And I do see with some artists that really get lost in that. They really get lost in it. I think James Brantley was very strong on that. He definitely was, look, I’m an artist. But he was very clear what he wanted to do. And that’s the thing. So that limitation—that you’re actually saying there’s a limitation, you know? You should paint this. I’ve had people—when I was living on Harvey Street not too long ago—who would come and they would tell me, you’re never going to make it if you keep painting Black people. They would say that.

STOKES SIMS: In New York, in the 1960s and 1970s, there was so much polemic around the art made by Black people. It was weaponized, to a certain extent, one group against the other—Blackstream or white mainstream. I remember being at many a dinner table talking about am I an artist? Am I a Black

artist? Do I paint the Black experience exclusively? If I do abstract work, am I copping out? If I do abstract work, are my colors different from anybody else’s? And to a certain extent, from my point of view, you can sort of say, yes, that’s true. But from another point of view, you can say, no, that isn’t true.

I remember visiting with Alex Katz—I think it was when the Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series show was at MoMA. And he said, I always thought Jacob used the Black colors. And I went, well what does that mean? And he couldn’t explain to me exactly. So I think people impose their own perspective on things that conform to their ideas, and make them feel comfortable with how they’re situated in the world.

BULLOCK: God, I mean, the arts are not supposed to be like that. I mean, that’s your expression. That’s your language, really. I could never understand that. But I could see where it was coming from.

I remember the FESTAC in Nigeria. Charles was like, we’re not doing any of that. So it was a problem there somewhere. We sat in a meeting—Romare Bearden was there. And I remember him saying, I’m definitely not going to go. And I was like, I’m not going either. If you’re not going, I’m not going. Next thing I knew, Charles was on the plane to Nigeria.

KING HAMMOND: FESTAC ’77 was the Second World Festival of Black Arts. Artists from the Black Atlantic diaspora and throughout the Africa continent convened in Lagos, Nigeria, to do an exposition of the arts in all genres. The US had a contingent of 200 artists who went under the leadership—this was the problem—of Jeff Donaldson. Because of the AfriCOBRA-ist aesthetic—which was expounded at length in Chicago—there was significant pressure on Black

artists to visualize their artistry more figuratively and within the “Kool-Aid color” palette.

There were a lot of artists who were pushing back against it because at the same time, there were many African American artists who were going to Africa independently on their own journeys— just like you—to seek their ancestral roots, to demythicize whatever had been laid upon them in terms of the expectations of being an artist. There was a lot of the Blackstream versus the whitestream tensions in the art world.

All the way back to the Harlem Renaissance and the New Negro Movement this was a constant discourse among Black artists. As modernism began to emerge Hale Woodruff asked, “I have to go modern?” What is this tension about modernism and an aesthetic authenticity of Blackness?

STOKES SIMS: Which came from Africa.

KING HAMMOND: Which came from Africa—where did Picasso get it from? It came from Africa. There was a lot of reckoning at the time with artists who prioritized their authority and agency to tell other artists what they should and should not do. Abstractionist Richard Mayhew caught hell because his landscapes are stunningly evocative, spiritual compositions of emotive colors. Too many artists were dismissed and looked over because they did not let their aesthetic integrity be compromised by the currency of this politics.

STOKES SIMS: The irony is now that they’re in their eighties or dead, the art world is looking back at those abstract artists—William T. Williams, Sam Gilliam, Howardena Pindell, Frank Bowling—and they’re getting their due. People are recognizing what they were doing.

KING HAMMOND: During that period of history there was minimal capacity to recognize levels of aesthetic expression that went beyond a Black consciousness in terms of style, content, and context. Multiple psychic spaces of an aesthetic Black ethos were being visualized and articulated in new and meaningful ways beyond figuration.

Barbara, you were probably saved by not having come from an experience of being educated in the Beaux-art academic realm, where curricula were too specific, weighted, and biased with condoned visual languages. Black artists who were first-time admitted into these institutions found themselves in the crosshairs of discovery to define their own sense of identity and agency.

You were spared those experiences because you were mentored similar to Jacob Lawrence. It gave you the critical freedom that affirmed and gave you the confidence needed to continue your experimentation. In spite of being dismissed and negated, it did not deter you. You felt the strength and support of your peers and colleagues and let them deal with those political battles while you went on your own journey.

BULLOCK: Definitely. And family, you know? And friends. It was just that whole thing of beauty. And you’re looking at your friends who are absolutely beautiful people. And hair—when it got to hair, it was like, oh, God. It was like, please, just don’t do this to me.

KING HAMMOND: The issues of Black hair have been worse than the paper bag. Between hair and the paper bags—the journey struggles on.

STOKES SIMS: So Barbara, here we are in 2023. You’re about to have a big retrospective. How would you evaluate the situation that you find yourself in,

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION 39

Altar for Yemaja, c. 2005 (Collection of the artist)

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION 39

Altar for Yemaja, c. 2005 (Collection of the artist)

and other artists find themselves in, given what’s going on in the global art market?

BULLOCK: To be honest with you, the global art market is very confusing. It’s so filled with everything. And I sort of help myself to see that because I stay on my computer, and I look at all these different exhibitions. And I don’t know, I just walk in my studio, and I look at my work. And I know the questions that are asked of me, I have to remember the 1960s and the ’70s and ’80s, and my head isn’t there. And I have to push it.

I know that I love what I did. I know there’s a continuum there. But I don’t really concentrate that much on what the continuum is. When I look around the studio, it’s like from the Dark Gods painting on the end, I look at a panther, I look at other pieces. And I think that—I know there’s a continuum. All I can say is that it’s life, you know? And I wish I didn’t get all the questions all the time because they’re kind of hard to answer. It’s like a ride. It’s the different stages of your life.

I was able to do that erotic series because that was the stage I was in. Because I worked in prisons and different places, things would happen. I would see people being shot. I would stand in front of someone who was being stabbed. I would see that. That changed me. I knew I had to talk about it, but you know, how do I talk about this?

I don’t want to paint negativity. But I know that I have to put it into my work. Hurricane Katrina, all the brothers that I’ve seen killed, and everything. I’ve actually seen it. And when I look at the paper, and I look at the paintings, I don’t know what’s going to happen until I work. Let’s put it like that.

So I continue to paint. And then when I begin to move shapes around, it’s sort of inside knowledge

of what a shape means to me. It just happens like that. Like with the mother and the son, it was like, those were two hearts. They didn’t look like hearts. Nobody thought they were hearts. But they were hearts that were entwined and broken.

If you begin to explain art, you’re going to lose it. I honestly believe that. I think you can’t talk about it. You have to do it. You have to mess with it. You have to experiment with it. And like I said, it’s that language. It just happens. So figurative—no problem.

But when it comes to the abstract—in my belief, life is abstract. It’s totally abstract. It’s not figurative. And it’s filled with all these brilliant colors, and forms, and this language that artists have, that we feel, like we know what we’re doing.

And at the same time, you do your exhibition, and people don’t know what you’re doing. And they want you to explain, what is this painting about? I find that now I’ve learned because of Ife Nii Owoo, my dear friend, who had a chance to sell work. And she had a piece in an exhibition, and the people were looking at it, and they went to buy this painting.

And so she went over to them. She said, I’ll tell you what that painting is about. And then when she told them, they were like, oh, that’s not what we thought. We don’t want that.

I said, that’s a lesson. Let them tell you. Let them look at it and see what they see in it.

STOKES SIMS: It’s about the relationship.

KING HAMMOND: Many people don’t have that confidence. They feel that the visual arts are this indecipherable language. Sometimes people just need to let themselves play with colors, shapes, harmonies, and see what these relationships do to create an interesting artistic experience.

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION 41

Stories My Grandmother Told Me

2012 (Courtesy of the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African American Art)

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION 41

Stories My Grandmother Told Me

2012 (Courtesy of the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African American Art)

BULLOCK: Yeah, especially the children. I found some of the most wonderful work by children. They never questioned it. When Charles and I said, we’re going to be painting spirits today, they were like, OK, where’s the paint? [LAUGHS]

I’ve worked in so many different schools in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, New York. The Guggenheim, that was interesting. But children are, like—you’re learning through them. The thing you’re learning is not to forget why you really wanted to do this in the first place. But that’s what they’re doing.

KING HAMMOND: Barbara, you’ve been so eloquent.

STOKES SIMS: Absolutely.

KING HAMMOND: Thank you so much. Is there anything else that you want to say?

BULLOCK: No, you really helped. It’s hard to talk about your work. You’re really hoping that people will see it. Oh, I also taught seniors. They were amazing to work with. I really wanted them to realize that all their photographs, and all of their furniture, and their clothes and everything, that we would make art with that. We would say, you know, your children will see this as artwork. These are your time capsules.

I remember a person from the office at the Center in the Park, the place where I was teaching the seniors, had come down and said, we want you to sell your stuff because your family’s only going to throw it away. It doesn’t have any meaning to it. And I had to really speak to that person. But I looked at the seniors, and they let it get into their heads like that. So we talked about that afterward. That’s when I introduced them to Betye Saar. And they just flew after that.

I also did work in Shippensburg. Shippensburg was like the South, but it was in Pennsylvania. I was the only Black person in Shippensburg. And everybody knew I was there. I was the artist in residence. In the beginning, nobody talked to me. In the middle, some people began to talk to me. At the end, everybody spoke to me, including the children— they gave me secrets. The girls talked about the boyfriends that their mothers didn’t know about. And they told me everything.

KING HAMMOND: That’s part of our fascinating experience in exploring the depths, profundity, and remarkable essence in the experiences of our Black lives.

BULLOCK: They were like, look at that, and what’s that down there? It’s like, it’s a seashell, you know? I also taught teachers—teachers are extremely creative, if you give them a chance.

VALERIO: One of Woodmere’s goals is to slow people down when they come in the museum in order to tap into creativity.

BULLOCK: I don’t know how people must feel about everyone having a camera now, like, click, click, click, click. I was at Gardens of the Mind at the African American Museum—I really loved that show. That was A. M. Weaver’s last exhibition. But when the people came in, the first thing they did was start snapping pictures and posing in front of the work.

STOKES SIMS: Missing the whole thing.

BULLOCK: Yeah, but that’s the way it is now.

KING HAMMOND: Thank you, Barbara.

STOKES SIMS: This was a beautiful conversation.

A Conversation about Art, Community, and Teaching with Barbara Bullock, Diane Pieri, and Hildy Tow

A CONVERSATION ABOUT ART, COMMUNITY, AND TEACHING WITH BARBARA BULLOCK, DIANE PIERI, AND HILDY TOW

On April 20, 2023, Hildy Tow, The Robert L. McNeil, Jr. Curator of Education, met with Barbara Bullock and her artist colleague Diane Pieri in Bullock’s studio to discuss their work as art educators.

HILDY TOW: Barbara, Woodmere is very excited to be presenting an exhibition that will highlight both the evolution of your artistic practice and your career as an art educator. This conversation will focus on the creativity you have inspired in children and adults in the many public schools and community centers in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. The exhibition will include several of the prototypes used in your teaching. We consider these artworks in and of themselves. Do you?

BULLOCK: Yes, I do. Art is art, and there was always a back-and-forth relationship between the work I was doing in classrooms and community centers and the work I was doing in the studio. The discoveries of the studio flowed into the classroom, and the people—students, teachers, and colleagues—constantly inspired me too. However, teaching was the profession through which I earned my living. The studio art was always my highest aspiration.

TOW: Diane, you and Barbara have a long friendship that began with collaborative teaching. How did you meet?

DIANE PIERI: It was 1980, and I hired Barbara as the associate artist when I was working as the head artist at the Germantown Workshop of Prints in Progress. Those were the titles of the jobs, but as soon as I met Barbara, we were co-teaching and coequal from day one. I thought that the head artist

meant that I was responsible for the administrative stuff, and to turn the heat on and off in the building.

TOW: [LAUGHS] Can you tell us more?

PIERI: Prints in Progress began in 1960 as an outreach program of the Philadelphia Print Club. It brought together artists and children through printmaking. I was hired for their free, after-school printmaking workshop for kids. It was supported by philanthropic Philadelphians.

TOW: I read that Walter L. Wolf, a board member of the Print Club (now the Print Center), launched the program “to bring art to children with limited access to creative experiences.” A 1965 article in Art Education states that he raised funding for the program from “public-spirited Philadelphians including the Loeb and Philadelphia Foundations.”

BULLOCK: At the Model Cities program at Ile Ife and I was told about Prints in Progress by Anne Lee Pitts [now Anne Edmunds], one of the early directors. This was in the mid-1970s. I remember the day that I met Diane. Diane was so busy with all the children. I came in, and said, “I would like to work here.” You said, “Wait over there.” [LAUGHTER]

Working at Model Cities prepared me. I saw that Diane had a similar approach to teaching children to draw and paint, so I felt really sure about working there. It was a great job, it really was. I can remember so many of the children because they

were so serious. The children told us they were artists and they expected to be treated like artists.

We would walk around while they were working and we would talk about what we were doing in our studios. If we stopped talking, the children wanted us to continue speaking, because they considered themselves artists also. It was one of those jobs where you knew that you were really going to be able to work with the children. So many of them could draw already and it was so natural.

PIERI: Barbara and I also talked about how committed we were to our own work. We would talk

about how much our lives were invested in our art.

BULLOCK: And how much time we needed to work. We often designed projects for the students that were similar to what we were working on in our studios.

TOW: Was Prints in Progress five days a week?

PIERI: It was an after-school program five afternoons a week, 3:00 to 5:00 p.m. The original Prints in Progress was the Green Street Workshop in the Spring Garden Community. They slowly opened up workshops in different areas of the city. There was one on Brandywine Street led

BARBARA BULLOCK: FEARLESS VISION 47 Bullock working at the Girls’ Club of Nicetown/Tioga, Philadelphia, a residency supported by the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, 1980. Courtesy of Barbara Bullock.

by Allan Edmunds, which developed into the Brandywine Workshop and Archives in 1972, as well as workshops at the Free Library of Philadelphia and the Samuel S. Fleisher Art Memorial, and in Germantown. I believe there was also a van called Print Mobile that traveled all over the city.

TOW: And you both ran the workshop’s Germantown after-school program?

BULLOCK: It was in a building across the street from Germantown Friends. The building still has a plaque on it that says “Prints in Progress.”

TOW: How old were the children you were teaching?

PIERI: Six to fourteen years old.

TOW: Both of you were and still are living in

TOW: What kind of projects would you do?

BULLOCK: In the beginning, we were doing prints. They wanted to make T-shirts and other things so we chose to work with silk-screen printing. They also made potholders.

PIERI: Right, we were doing silk-screen—it’s a printing process where multiple copies of the same image or design can be produced. Stencils are supported by a mesh fabric that is stretched across a frame called a screen. Ink is forced into the mesh openings with a squeegee and the design is transferred onto another surface below.

Germantown. What was the impact of living in the same community as the students?

BULLOCK: I was on Greene Street in Germantown and lived three blocks away.

PIERI: It was absolutely terrific. There was a fabulous thrift store called Village Thrift where we would go to buy materials for different projects. The kids would be walking down the avenue and they would say, “Hi Barbara. Hi Diane.” We would say, “Are we going to see you on Tuesday? Don’t forget.” We were always walking advertisements for the Germantown Workshop of Prints in Progress. As a result, our attendance was always excellent and consistent.

BULLOCK: Students felt so close to us, like friends.

BULLOCK: They began by drawing a design in the art room. Then the children would go to the office where there was a long table set up with the screens. They would get in line to make their print. Diane and I helped them move the squeegee to push the ink through the screen and make the print. It felt almost like a factory. I said, “Diane, we’re not getting to know the children at all because they’re drawing in one room, and then they come and print and leave. We need to have other projects.” We decided at that point that we were going to do more than printmaking. We were going to work on drawing.

PIERI: They made really beautiful drawings. We also introduced sewing, beading, and using shells.

TOW: What kinds of projects were those?

BULLOCK: Years before, I was looking at African sculptures and had this idea to create figurative forms that involved sewing, beads, shells, and other things. I showed them to Diane and we decided it was a good idea to introduce a sewing project to the students. We made dolls but couldn’t call them dolls because we had boys in the class and

weren’t sure they would want to make them. We told the students they would be making “figures.” They could be based on someone in their family, or an imaginary figure. I remember bringing in a bag of fabric, beads, shells, and other things. The next thing I knew the children had emptied out the bag and were just going through it.

PIERI: I remember the enthusiasm just with the materials.

BULLOCK: We gave them a choice of black, red, and white fabric to use for their figures. They had to draw a pattern of their figure on paper that was then pinned onto two pieces of fabric. The children cut out the pattern on the fabric and cut a long slot down the middle of one of the pieces to be used as an opening for stuffing the figure later. After sewing the fabric pieces together along the edges, they turned it inside out and filled it with stuffing to make a solid form.

There was a grocery store on Wayne Avenue that let us go upstairs and work together around a large round table. We taught them to sew and how to be careful about their stitching. We were all sewing away. This one little girl, a little Italian girl who sang opera and was actually the boss of all the other children, stood up with her needle and her little figure and said, “We are so fortunate because we are making girls who have Virginias and the boys are making boys that have ducks.” She was talking about female and male genitalia. [LAUGHS]

While we were sewing, the children would talk about their lives and ask questions. Diane and I would listen and respond. I noticed how similar Diane and I were in working with children. Diane taught them embroidery and a stitch that her grandmother had taught her. It was all step by step.

They embroidered the faces and chose different fabrics to make clothes. They made hair with three or four strings and macramé knots and added beads and shells.

PIERI: It was a very time-consuming process to make these projects, for example, the masks. And you don’t want to show kids too much because sometimes they would just imitate what they saw.

BULLOCK: For the masks, we had the students create an armature out of poster board strips. We had pre-cut the strips into different sizes, long, medium, and short, curvy and straight. They would begin by connecting long strips to create the outside form, and then use more strips to mold the three-dimensional structure of a face. They would use medium and small strips to fill up the curves of the cheeks, forehead, and nose until the armature was complete. We used lots of staples to connect the strips.

Next the children layered newspaper, brown paper, and colored tissue paper on top. They used matte medium as the adhesive so the tissue paper colors wouldn’t bleed.

PIERI: I made a monkey lady mask as a prototype. To build the features, we told the kids to put the skin on the face and make it more solid. It took weeks!

BULLOCK: They left spaces for eyes and painted or molded a mouth. For the nose, we suggested openings for the nostrils so the mask was more comfortable to wear.

PIERI: Since this process took a long time, we made little sketchbooks for the kids and after projects were complete or they got to a stopping point we would say, get your sketchbook and draw.

BULLOCK: We would have children of different ages in the classes so it was important to have a schedule and a structure for every class.

PIERI: Prints in Progress did not supply snacks for the kids. Barbara and I instituted the idea that kids bring their own snacks so they could calm down, relax, replenish their energy and draw before starting to work on the projects, so we started the program by giving the children snack time. And having them relax after school. The class ended with time to draw.