Crystalle Lacouture

American, born, Canada, 1978

Correspondence (for Elizabeth Bishop), 2024

Acrylic painting, translated to vinyl mural

Courtesy of the artist and Praise Shadows Gallery, Brookline

Crystalle Lacouture utilizes the powerful symbolism of pattern and color to create sensitive, spiritual art imbued with deep personal meaning. She brings this sensibility to the grand scale of the Worcester Art Museum’s (WAM’s) central Renaissance Court, enlivening the stucco space with a vibrant abstract design that maintains a specific connection to its site, while simultaneously inviting multifaceted interpretations.

Lacouture’s work often references sacred geometry—recurring patterns found in nature and applied in art and religion because they are believed to have divine resonances. She is interested in how these shapes interact with each other and create reverberating energy when combined in compositions. In this way, her work draws inspiration from early 20th century spiritual abstraction, particularly the paintings of Swedish artists Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) and Anna Cassell (1860–1937). While there is not a religious or mystical connotation to her work, Lacouture similarly views the labor of painting as akin to a devotional act, and she feels compelled to create work that “investigates huge things reduced to microcosms and small things blown up for closer inspection.”

Like her predecessors, Lacouture applies what has historically been regarded as a “feminine” aesthetic to her paintings, employing delicate washes of soft hues, elegant lines, and graceful intertwining of shapes. In Correspondence (for Elizabeth Bishop), a dark pink outline highlights a central rhombus, underscoring this concept and connecting the timeless design—echoed in historic art surrounding the Wall at WAM— with Lacouture’s contemporary sensibility. She purposefully retains traces of her hand in the

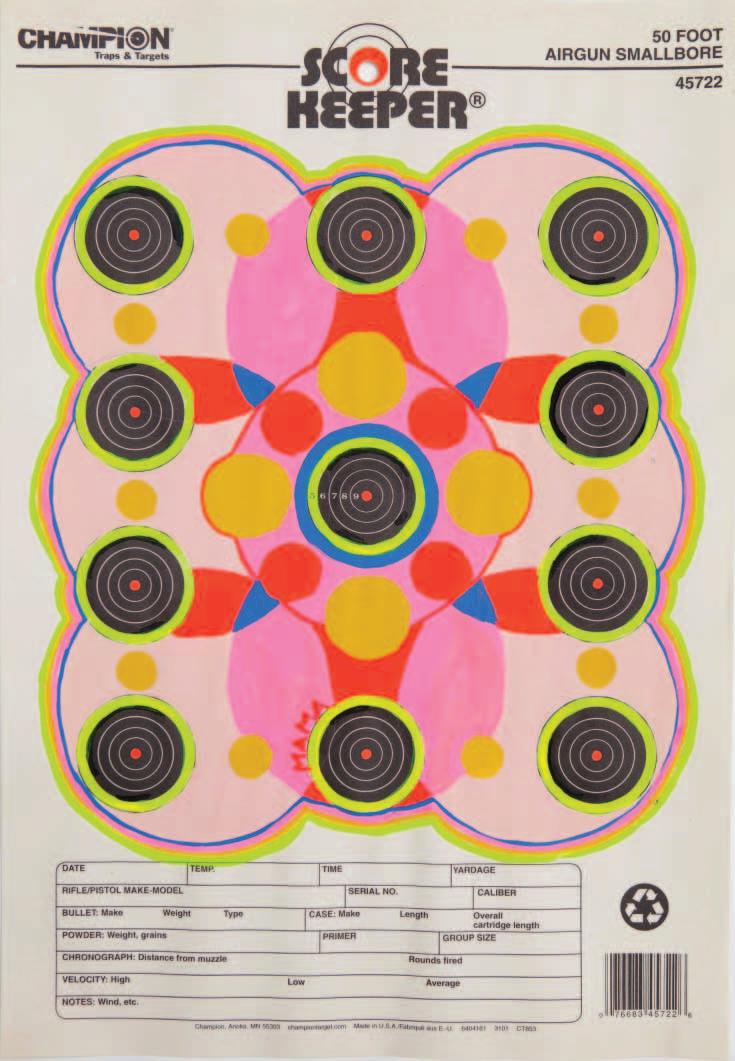

During a period when her mother was gravely ill, Lacouture maintained a practice of creating one small drawing every day as a devotional for her mother. She made her MAMA Drawings on paper shooting targets, noting that “because the papers are already charged with language and designs that imply violence, speed, and action, and the shapes have intense directionality, I thought I could manipulate that innate power and redirect it towards her healing.”1

work, embracing undulating, hand-drawn lines and eschewing the typical techniques of geometric abstraction, like using masking tape to achieve sharp edges. Lacouture was inspired by the rough-hewn nature of WAM’s ancient and medieval devotional art, particularly because their appearance relays to the contemporary viewer that such objects were labored over by a person and for a purpose. Lacouture hopes her painting emits a similar energy and that the work might be received as a gift, a blessing, or an invitation for mediation.

Lacouture’s work may be best understood as conceptual art conveyed through abstract compositions. When invited to make a new installation for the Wall at WAM, the artist investigated the Museum, its collections, and its city, then let her discoveries fuel her creativity.

Lacouture was first inspired by the art on view in the Museum’s collection galleries. She was drawn especially to details of patterns in art spanning centuries and continents—such as 16th century painted textile fringes and 12th century carved stone archways. She observed that many of these patterns, while rendered differently and expressed for various purposes, are rooted in basic designs common to visual traditions from diverse cultures. Several of these inspirations are incorporated into Correspondence (for Elizabeth Bishop), such as the wave-like trim borrowed from an ancient Antioch mosaic installed directly below it.2 In this way, Lacouture sees her painting in conversation with the other art in the Museum, a tribute to art’s correspondence across time and cultures.

While connected to the Museum in these ways, Lacouture’s mural is also conspicuously distinct. Her bright, ethereal painting juxtaposes the imposing stone Renaissance Court, and her purposefully “feminized” style symbolically contradicts the masculine energy of the building by virtue of being situated in a museum which, like most, was designed by male architects and houses a history of art which has traditionally focused on art by men. Located in the heart of the Museum, Correspondence (for Elizabeth Bishop)

presents and re-presents itself to visitors throughout their visit, asserting its presence and altering the aesthetics of the space.

Upon the realization that one of her favorite poets, Elizabeth Bishop (1911–1979), was born and buried in Worcester (despite living elsewhere for most of her life), Lacouture was compelled to pay homage to Bishop in this project at the poet’s hometown museum.

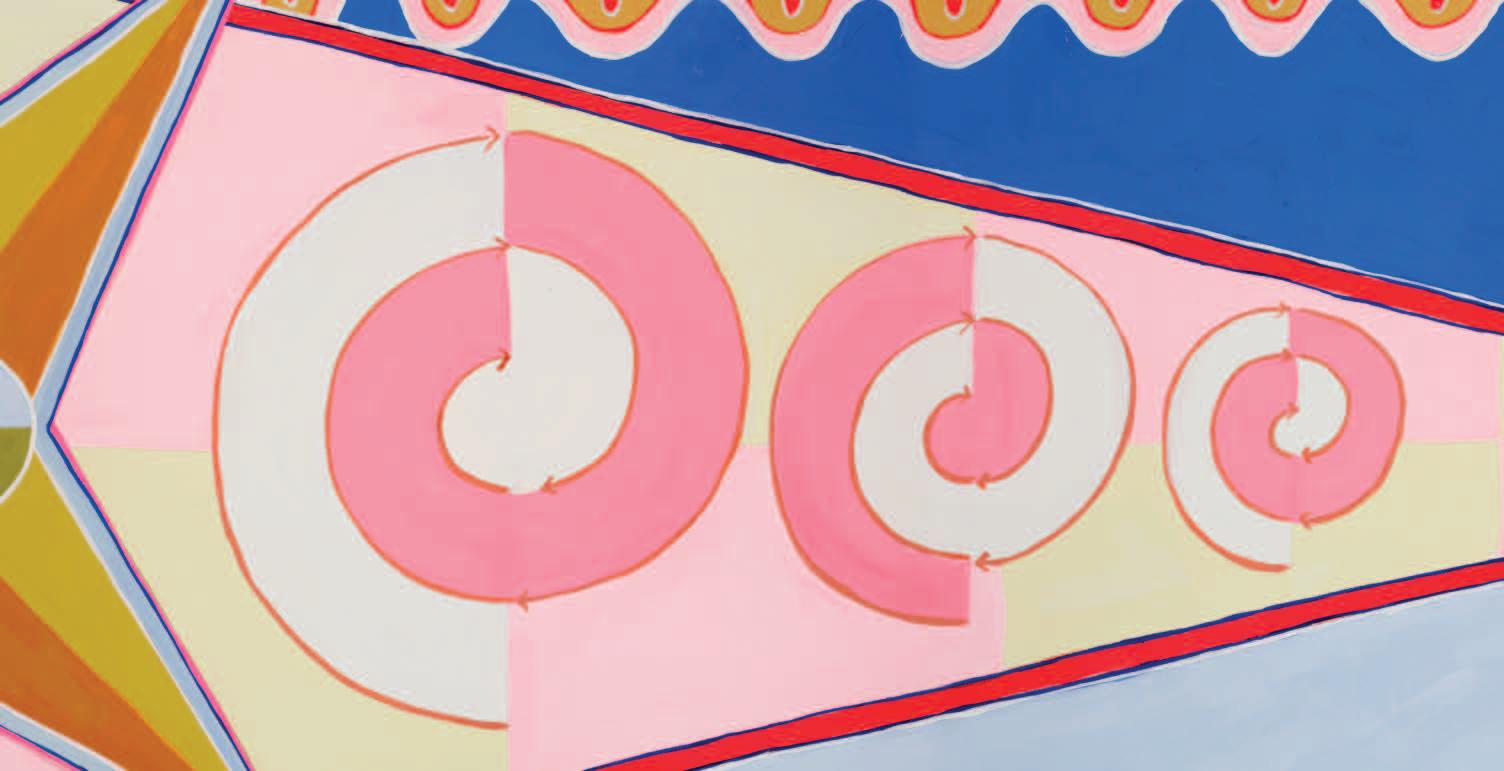

In sacred geometry and in art, a spiral often references cosmic energy, life cycles, or the process of creation. In Correspondence (for Elizabeth Bishop), it retains those allusions while making a specific reference to Bishop: Lacouture’s repeated spiral form is a graphical representation of a sestina, a complex poetry form consisting of six, six-line stanzas used by Bishop in a poem of the same name (“Sestina,” 1956).3 One of Bishop’s most studied poems, it references family dynamics, grief, and loneliness; many scholars believe it was inspired by her own tragic childhood, spent partially in Worcester.

Lacouture embeds another reference to Bishop in the border of the work using Baudot Code (a binary code which translates text using a

two-symbol code of 1s and 0s) to quote some of Bishop’s poetry. This code begins in the lower left of the composition and continues counterclockwise to the upper left—another nod to the spiral form. Lacouture cleverly links phrases from two different poems to illustrate Bishop’s connection to Worcester: “In Worcester Massachusetts…” “All the untidy activity continues, awful but cheerful.” The first phrase is the opening of a poem describing an early childhood memory and realization of self (“In the Waiting Room,” 1971),4 while the second is the closing line of “The Bight,” 1948,5 which Bishop wrote on one of her birthdays and requested as the epitaph on her gravestone.

Bishop’s extensive written correspondence with distant friends, most famously her lyrical exchanges with fellow Massachusetts poet Robert Lowell (1917–1977), add yet another meaning to the title of Lacouture’s work. Though the two poets were rarely in the same place, they were a constant presence in one another’s lives and even work. These letters— and Bishop’s poetry—are filled with references to constellations, planets, and musings on existing under the same skies. Lacouture found great beauty and universal resonance in these sentiments, and uses pinks and blues respectively to reference the idea of bodies and skies.

For Lacouture, Correspondence (for Elizabeth Bishop) is rooted in specific connections, among them those between herself and WAM, between Elizabeth Bishop and Worcester, and between distant friends. But it is the broader concepts of connection that the artist invites us to consider when observing this work: our connection to the space in which we stand, the time in which we find ourselves, the people around us, and the art by which we are surrounded. Positioned in the central gathering space of an institution whose mission is to connect people, communities, and cultures through the experience of art, Lacouture’s work is a testament to the potential of art to transcend.

1 Lacouture, quoted a profile by Jessica Shearer, “Visits and Vigils: Crystalle Lacouture’s Material Memories,” Boston Art Review Issue 10 (Nov. 13, 2023), 34-41.

2 See right for a deeper discussion of these inspirations and references from WAM’s collection.

3 “Sestina” was originally published in The New Yorker, September 15, 1956, 46.

4 Written in 1971 and published in the collection Geography III (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976), 3-8.

5 “The Bight” was originally published in The New Yorker, February 19, 1949, 30.

Crystalle Lacouture’s multimedia practice includes painting, printmaking, sculpture, and conceptual art. She received her BFA in Painting/Printmaking from Skidmore College, where she received the Pamela Weidenman Award for Excellence in Printmaking. She has been a Resident Key Holder Artist at the Lower East Side Printshop and has attended residencies at the Fine Arts Work Center (Michael Mazur Printmaking), Surf Point Foundation, Vermont Studio Center, the Vanguard Mastheads, Contemporary Artist Center, Room 83 Spring, and the Aspen Art Fair, among others. She exhibits her work throughout the United States and is in numerous private and public collections including the Amon Carter Museum of American Art (Fort Worth, TX) and the Worcester Art Museum. Lacouture is represented by Praise Shadows Gallery (Brookline, MA), and is based between Wellesley and North Adams, MA.

The Wall at WAM is an ongoing series of murals installed on a 67 x 17-foot expanse overlooking the Worcester Art Museum’s Renaissance Court. Crystalle Lacouture is the 11th artist commissioned for this series begun in 1998. Correspondence (for Elizabeth Bishop) will be on view from September 18, 2024 into 2026. This project was organized by Samantha Cataldo, Curator of Contemporary Art, with Delaney Keenan, Curatorial Assistant.

Contemporary art installations in common spaces at WAM are supported by the Fletcher Foundation, Larry and Marla Curtis, the Don and Mary Melville Contemporary Art Fund, the John M. Nelson Fund, and Marlene and David Persky.

The center star-shaped form refers to compasses and directionality, as well as to the shapes Lacouture encountered when examining WAM’s collection of early Italian gold-ground panel paintings. The punchwork, or decorative tooling, of the gold leaf surface in panels like Saint Agnes is often geometric and features repeating patterns of star-like forms. This elegant detailing is characteristic of Sienese painting of the 14th century, and Lacouture remarked that these delicate lines and shapes connected to the visual aesthetic of her own artistic practice.

Location: Gallery 212

Location: Gallery 111

This window grille or grid, known as a reja, is an exceptional example of wrought-iron metalwork that would have been used in both secular and sacred architecture. Lacouture was inspired by the thought of the skilled craftsperson who created this object; she is persistently interested in the labor of artmaking, particularly objects which would occupy sacred spaces for devotion. Further, the work resonated with her interest in sacred geometries and the cosmic spiral, which manifests in this repeated pattern.

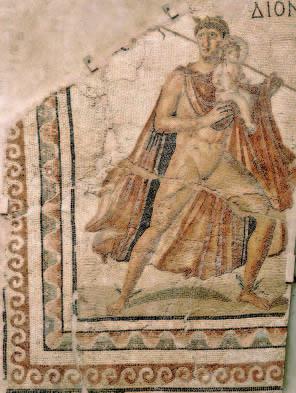

The patterns and forms found in the border imagery of the Antioch mosaics directly below the Wall at WAM struck Lacouture as modern and reminiscent of her own visual language. The undulating and swirling waves surrounding the decorative border of this mosaic can be seen along the edges of Lacouture’s monumental design—though she manipulated the form such that the swirling waves always point inwards towards the central star of her composition.

Hermes and Dionysos floor mosaic, Roman, 4th century CE, Excavation of Antioch and Vicinity funded by the bequests of the Reverend Dr. Austin S. Garver and Sarah C. Garver, 1936.32

Location: Renaissance Court

Lacouture noticed how the alternating pattern of circles and elongated ovals in the decorative border of this fresco fragment visually resembles a binary code system. She connected this to her own deep interest in shapes and color as forms of visual language and encoded messages. The painterly quality of this fresco also speaks to the hand-made nature of the work and directly relates to Lacouture’s insistence on showing her own presence via self-evident lines and visible brushstrokes.

from Santa Maria inter Angelos, Spoleto, attributed to Maestro delle Palazze, The Last Supper and the Agony in the Garden, about 1300, fresco transferred to canvas, Museum purchase, 1924.24

Location: Gallery 109