Working Today for a Better Tomorrow in Ethiopia

Jobs for Poor and Vulnerable Households

INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN FOCUS

Emily Weedon Chapman and Margaux Vinez, Editors

Jobs for Poor and Vulnerable Households

Working Today for

Better Tomorrow in

a

Ethiopia

INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN FOCUS

Editors

EMILY WEEDON CHAPMAN AND MARGAUX VINEZ,

© 2023 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank

1818 H Street, NW, Washington, DC 20433

Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org

Some rights reserved

1 2 3 4 26 25 24 23

Books in this series are published to communicate the results of World Bank research, analysis, and operational experience with the least possible delay. The extent of language editing varies from book to book.

This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or currency of the data included in this work and does not assume responsibility for any errors, omissions, or discrepancies in the information, or liability with respect to the use of or failure to use the information, methods, processes, or conclusions set forth. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries.

Nothing herein shall constitute or be construed or considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved.

Rights and Permissions

This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions:

Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: Chapman, Emily Weedon, and Margaux Vinez, eds. 2023. Working Today for a Better Tomorrow in Ethiopia: Jobs for Poor and Vulnerable Households. International Development in Focus. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-2020-5. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO

Translations—If you create a translation of this work, please add the following disclaimer along with the attribution: This translation was not created by The World Bank and should not be considered an official World Bank translation. The World Bank shall not be liable for any content or error in this translation.

Adaptations—If you create an adaptation of this work, please add the following disclaimer along with the attribution: This is an adaptation of an original work by The World Bank. Views and opinions expressed in the adaptation are the sole responsibility of the author or authors of the adaptation and are not endorsed by The World Bank.

Third-party content—The World Bank does not necessarily own each component of the content contained within the work. The World Bank therefore does not warrant that the use of any third-party-owned individual component or part contained in the work will not infringe on the rights of those third parties. The risk of claims resulting from such infringement rests solely with you. If you wish to re-use a component of the work, it is your responsibility to determine whether permission is needed for that re-use and to obtain permission from the copyright owner. Examples of components can include, but are not limited to, tables, figures, or images.

All queries on rights and licenses should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street, NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; e-mail: pubrights@worldbank.org

ISBN: 978-1-4648-2020-5

DOI: 10.1596/978-1-4648-2020-5

Cover art: © Jihane El Khoury Roederer, World Bank. Used with permission; further permission required for reuse.

Cover design: Debra Naylor / Naylor Design Inc.

Contents

Acknowledgments xi

About the Editors and Authors xiii

Executive Summary xvii

Abbreviations xxix

PART I ETHIOPIAN LABOR MARKET

iii

CHAPTER 1: The Challenges of Job Growth in Ethiopia 3 Summary 3 Introduction 4 Service sector jobs are increasingly important in Ethiopia 6 Unemployment and inactivity are on the rise 12 Vulnerable groups face additional challenges in a difficult labor market 17 Conclusion 21 Note 22 References 22 SPOTLIGHT 1.1: Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Program 24 SPOTLIGHT 1.2: Ethiopia’s Urban Productive Safety Net and Jobs Project 26 PART II BARRIERS TO BETTER JOBS FOR POOR AND VULNERABLE WORKERS CHAPTER 2: Women in Rural Jobs: Constraints to Productivity 31 Summary 31 Introduction 32 Rural women in the Ethiopian labor market 33 Women in agriculture 36 Women in nonfarm enterprises 39 Women in wage employment 41 Limited access to financial services hinders rural women’s productivity 42 Designing safety nets to reduce gender gaps 44 Conclusion 45

Notes 47

References 47

Annex 2A: Productivity of male- and female-managed agricultural plots in Ethiopia 48

Annex 2B: Productivity of male- and female-managed nonfarm enterprises in Ethiopia 51

Annex 2C: Productivity of men and women in wage employment in Ethiopia 53

CHAPTER 3: Youth Employment in Urban Ethiopia: Aspirations in the Labor Market 55

Summary 55

Introduction 56 Employment trends among Ethiopian urban youth 57

62

67

Conclusion 72

Notes 72

References 73

CHAPTER 4: Disability and Work in Ethiopia: Supporting Access to Good Jobs 75

Summary 75

Introduction 76

Framework for understanding disability 76 Portrait of people with disabilities in Ethiopia 80

Promoting an enabling environment in Ethiopia 83

Conclusion 85

Notes 86

References 87

CHAPTER 5: Social Safety Nets and Labor Migration: Influencing, but Not Deterring, Urban Migration 91

Summary 91

Introduction 92

Migration, poverty reduction, and jobs 92 Evidence on social safety nets and migration 93 History of migration in Ethiopia 94 Migration patterns of the poor in rural communities 96

of PSNP on migration patterns 103

Conclusion 104

Notes 104

References 105

Annex 5A: Determinants of migration across PSNP and non-PSNP areas in Ethiopia 108

PART III SOCIAL SAFETY NET PROGRAMS TO INCREASE EARNINGS AND PRODUCTIVITY

CHAPTER 6: Creating Small Enterprise and Microenterprise Jobs in Ethiopia: The Role of Social Safety Nets 111

Summary 111

Introduction 112

Self-employment is the predominant form of work for poor households 112

Self-employment is critical for poverty reduction 114 Social safety nets and economic transformation for self-employed individuals 116

iv | W ORKING T ODAY FOR A B ETTER T OMORROW IN E THIOPIA

When the labor market works for Ethiopian youth

Role of aspirations in job status

Impact

Ethiopia’s rural social safety nets and self-employment for poor households 122

Social safety nets and self-employment in urban Ethiopia 126

Conclusion 128

Notes 130

References 130

SPOTLIGHT 6.1: Climate-Smart Self-Employment 133

CHAPTER 7: Wage Employment Interventions in Ethiopia’s Social Safety Net Programs: Matching Poor Workers to Wage Jobs 135

Summary 135

Introduction 136

Wage employment’s role in poverty reduction 136 Social safety net programs can help poor individuals into wage employment 137

Engaging rural Ethiopians in wage work in towns and small cities 142

Overcoming barriers for young job seekers in urban areas 143

Conclusion 147 Notes 148 References 149

CHAPTER 8: Conflict, Displacement, and Livelihoods in Ethiopia: Role of Social Safety Nets 153

Summary 153 Introduction 154

Pathways to support of displaced people 156

Overview of displacement in Ethiopia 157

Role of Ethiopia’s social protection system in supporting displaced people 167

Conclusion 173

Notes 174

References 177

CHAPTER 9: Labor Market Delivery Systems for Ethiopia and Beyond: A Framework Approach 181

Summary 181

Introduction 182

Steps in making labor market policies work 183

for employment and employability 184 Phases of a labor program delivery system 185

Conclusion 210

Notes 211

References 211

Annex 9A: Checklist for supporting apprenticeship program delivery systems 214

Boxes

ES.1 A durable solution: Livelihoods for internally displaced people in Ethiopia xxiv

1.1 Data sources and methodology 5

1.2 Income growth evades rural households in Ethiopia, particularly poor rural households 11

1.3

Contents | v

Programs

Data

the

Ethiopia’s

Service-led structural transformation 13 2.1

sources for

rural Ethiopian labor market 32 3.1

Urban Employment Unemployment Survey 57

3.2 Demand assessment for the Urban Productive Safety Net and Jobs Projec t’s apprenticeship program 67

4.1 Main conceptual models of disability 77

4.2 World Bank commitments and programs on disability-inclusive development: Haiti and Ethiopia 80

5.1 Methodology of the PSNP migration study 97

6.1 Lessons from the early graduation pilot in Ethiopia 120

6.2 A multidimensional approach to improve incomes among Niger’s poor population 120

6.3 Adapting the graduation approach for people with disabilities 122

7.1 An evidence-based approach to the Bikat Program’s design 144

8.1 Study methodology 155

8.2

9.1

9.2 Successes and challenges of Guinea’s Women Breaking Barriers outreach campaign 186

9.3 Awareness campaign for Ethiopia’s Bikat Program 188

9.4

9.5 Lessons from the Bikat Program’s registration process 191

9.6 Role of entrepreneurship aptitude tests in finding suitable training candidates 194

9.7 Enrolling firms in Ethiopia’s Bikat Program 195

9.8 Kenya’s Youth Employment and Opportunities Project: Assessing formal and informal training providers 196

9.9 Eligibility criteria for young entrepreneurs under Kenya’s

9.10

9.11

9.13

Figures

ES.1 Low-skill self-employment remains the most common type of work in Ethiopia xviii

ES.2 Ethiopia has seen slow shifts in its labor market, with services as the only growth sector xix

ES.3 Unemployment in Ethiopia has almost doubled since 2013, with women and rural areas hardest hit xx

ES.4 Across all sectors, women in Ethiopia earn less per month than men xxi

ES.5 Within Ethiopia’s service sector, most urban youths work in low-skill domestic jobs xxii

ES.6 Young people, particularly young women, are increasingly leaving the Ethiopian labor market xxii

ES.7 Wealthier households in Ethiopia have more diversity in how they earn a living xxiii

ES.8 Job support activities complement cash transfers for better labor outcomes in Ethiopia xxv

ES.9 From productive safety nets to produc tive jobs in Ethiopia xxvi

1.1 Service sector has driven job creation in Ethiopia for nearly two decades 7

1.2 Most people in Ethiopia are self-employed 8

1.3 Ethiopia has seen little shift away from low-skilled employment 9 1.4 Wage job creation fell and remained weak in rural areas of Ethiopia 10 1.5 Public sector accounts for half of wage employment in Ethiopia 10

1.6 For wage employment in Ethiopia, real wages rose regardless of education or gender 11

1.7 Unemployment in Ethiopia has almost doubled since 2013, increasingly affecting women and rural areas 14

vi | W ORKING T ODAY FOR A B ETTER T OMORROW IN E THIOPIA

Community-based health insurance in Ethiopia 168

Urban

Productive Safety Net and Jobs Project’s Bikat Program 183

Intake requires trained support staff 190

Opportunities

Youth Employment and

Project 198

Matching trainees with training providers in Kenya’s

Opportunities Project 199

Youth Employment and

Onboarding for Guinea’s Women Breaking Barriers Project 201 9.12 Using results-based contracts to enhance program effectiveness 203

Project monitoring and outcome tracking in Kenya’s Youth

Opportunities

209

Employment and

Project

1.8 Unemployment is rising across Ethiopia, regardless of age or educational attainment, with the burden falling disproportionally on young people 14

1.9 Rural underemployment in Ethiopia has doubled since 2005 15

1.10 People in Ethiopia are leaving the labor market 15

1.11 Inequitable distribution of household work affects women’s labor market participation in Ethiopia 16

1.12 Education partly explains lower labor market participation, but women are increasingly NEET 17

1.13 Four profiles of vulnerable groups cover a significant part of Ethiopian society 18

1.14 In Ethiopia, inactivity increased across the four profiles, especially for rural women 19

1.15 Unemployment and underemployment are on the rise among vulnerable groups in Ethiopia 20

1.16 Trends in, but not rates of, work in different sectors mirror national statistics in Ethiopia 20

1.17 Employment pathways have remained the same over the past two decades, with some small changes at the national level and for some groups 21

S1.1.1 Consumption expenditures doubled for PSNP households by 2014 25

S1.2.1 UPSNP labor-intensive public works demonstrated positive individual, household, and community impacts 27

2.1 Rural labor force participation in Ethiopia, by gender, 1999–2021 34

2.2 Reason for not seeking a job in Ethiopia, by gender and age group, 2021 34

2.3 Rural employment in Ethiopia, by sector and gender, 1999–2021 35

2.4 Self-employment in rural Ethiopia, by gender, 1999–2021 35

2.5 Informal employment in Ethiopia, by gender and education level, 2021 36

2.6 Monthly wages in Ethiopia, by gender and sector of employment, 2021 36

2.7 Weekly time spent on various activities in Ethiopia, by gender and age, 2018/19 37

2.8 Land size and livestock ownership in Ethiopia, by gender of household head, 2018/19 37

2.9 Number of productive agricultural assets owned in Ethiopia, by gender of household head, 2018/19 38

2.10 Use of improved seeds and fertilizer in Ethiopia, by gender of plot manager, 2018/19 38

2.11 Ownership of nonfarm enterprises in Ethiopia, by type of business and gender of household head, 2018/19 39

2.12 Income from nonfarm enterprises in Ethiopia, by gender of household head, 2018/19 40

2.13 Constraints to starting and growing a nonfarm enterprise in Ethiopia, by gender of household head, 2018/19 41

2.14 Proportion of employed population that engaged in paid work over the past 12 months in Ethiopia, by gender, 2018/19 42

2.15 Last reported month’s salary of those engaged in paid work in Ethiopia, by gender, 2018/19 42

2.16 Average hours worked per week in paid wage employment in Ethiopia, by gender, 2018/19 42

2.17 Proportion of population that owns an account in a financial institution in Ethiopia, by gender, 2018/19 43

2.18 Proportion of population that knows how to open a bank account in Ethiopia, by gender, 2018/19 43

2.19 Saving patterns in Ethiopia, by gender, 2018/19 44

2.20 Credit and loan rejection rates in Ethiopia, by gender of household head, 2018/19 44

3.1 Ethiopia’s rapidly growing youth and urban populations will magnify the challenge of urban youth employment 56

Contents | vii

3.2 Initial increase in Ethiopia’s youth labor force participation rate from 2010 to 2014 reversed after 2015 58

3.3 Despite increased school attendance in Ethiopia since 2014, the number of young people, especially women, left behind has grown 58

3.4 Increased access to education in Ethiopia is delivering more educated youth, but the vast majority do not make it beyond secondary school 59

3.5 Youth unemployment in Ethiopia has risen since 2015, with large gender disparities 60

3.6 Majority of Ethiopia’s unemployed youth has had consistently low levels of education 60

3.7 Ethiopia’s rising unemployment seems to be driven particularly by gender disparities 61

3.8 Duration of unemployment in Ethiopia has increased, particularly for women and those with less education 62

3.9 Urban youth in Ethiopia are more likely to have private wage employment and less likely to be self-employed 63

3.10 Ethiopian youth with higher education are more likely to have a permanent job 64

3.11 Urban youth in Ethiopia, especially women, are more likely to work in the service sector 65

3.12 Most service sector jobs in Ethiopia are in low-skill domestic services, which have limited scope for structural transformation 65

3.13 In Ethiopia, young people with higher education dominate the skill-intensive jobs that have potential for economic transformation 66

3.14 Majority of unemployed youth want to be in self-employment, but their employed peers are predominantly in wage employment 68

3.15 Although many of their less-educated peers work in low-skill jobs, few unemployed young people want such jobs 69

3.16 Income expectations of Ethiopian youth do not align with labor market realities, 2020 70

3.17 Wages offered by Ethiopian firms to junior employees with higher education are more in line with youth expectations, but wages offered for those with less education do not meet those expectations 71

3.18 Unemployed Ethiopian youth cite lack of jobs as the most common reason for not working 71

4.1 Vicious cycle of poverty and disability 78

4.2 In Ethiopia, the proportion of people with disabilities who have no education remains high, 2005, 2013, and 2021 82

4.3 In Ethiopia, people with disabilities engage in low-productivity sectors, by vulnerable groups, 1999–2021 82

5.1 International migration of Ethiopians, by stock and flows, 1990–2019 95

5.2 Migration status of PSNP and non-PSNP households in Ethiopia, 2021 97

5.3 Time spent away by migrating, PSNP and non-PSNP households in Ethiopia, 2021 98

5.4 Month of out-migration by PSNP and non-PSNP households in Ethiopia, 2021 98

5.5 Month of return of migrating PSNP and non-PSNP households in Ethiopia, 2021 99

5.6 Destinations of migrating PSNP and non-PSNP households in Ethiopia, 2021 99

5.7 Reasons for migrating, all migrants from PSNP and non-PSNP households in Ethiopia, 2021 100

5.8 Reasons for migrating, returning migrants from PSNP and non-PSNP households in Ethiopia, 2021 100

5.9 Reasons not to migrate, PSNP and non-PSNP households in Ethiopia, 2021 101

5.10 Reasons for returning, migrants from PSNP and non-PSNP households in Ethiopia, 2021 102

6.1 Household head’s employment type in Ethiopia, by area, PSNP participation, gender, and age, 2016 113

viii | W ORKING T ODAY FOR A B ETTER T OMORROW IN E THIOPIA

6.2 Self-employment in rural and urban areas in Ethiopia, by subsector, 2016 113

6.3 Industries accounting for self-employment in Ethiopia, by wealth quintile, 2016 114

6.4 Household head’s employment type in Ethiopia, by education level, 2016 115

6.5 Earnings in Ethiopia, by sector and compared to global averages 116

6.6 Comparison of factors affecting agricultural produc tion in PSNP and non-PSNP households in Ethiopia, 2016 118

B6.2.1 “Projet de filets sociaux” intervention cycle and suppor t services, Niger 121

7.1 Wage employment could help in Ethiopia’s structural transformation 137

7.2 Regardless of gender, poor households in Ethiopia have little access to wage jobs 138

7.3 Framework for integrated employment programs in Ethiopia 139

7.4 Employment record of Ethiopian youth consists of frequent unemployment 145

7.5 Most Ethiopian firms are interested in hosting an apprentice 145

7.6 Approximately one in three firms has previously hosted an apprentice, but few are currently hosting apprentices 146

7.7 One in three Ethiopian firms provides formal training 146

7.8 Most training provided by Ethiopian firms focuses on technical skills 147

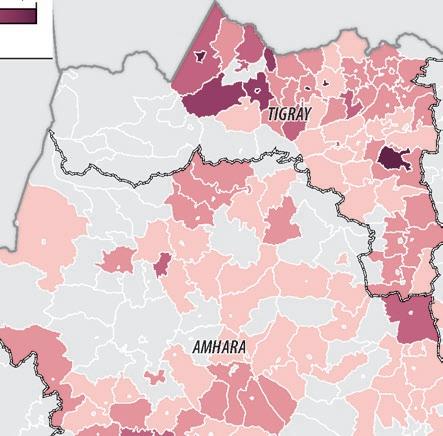

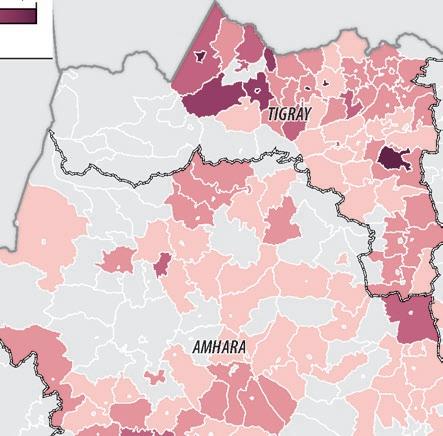

8.1 Internal displacement in Ethiopia, by cause, 2012–21 158

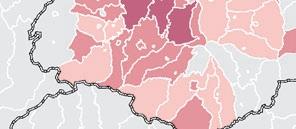

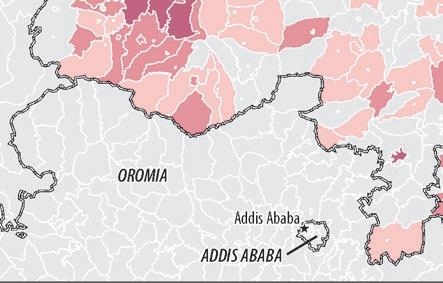

8.2 Displacement in Ethiopia, by region, 2022 159

8.3 Number of internally displaced people in the northern Ethiopian crisis, by region, January 2021 to February 2022 161

8.4 Share of displaced people in selected Ethiopian regions, by site type 163

8.5 IDPs in range of each Ethiopian safety net, by IDP status and rural vs. urban 169

8.6 Entry points for social protection systems in Ethiopia along the displacement timeline 170

9.1 Delivery chain for labor programs 183

B9.5.1 Sample of Bikat Job Seekers Registration Form 191

9.2 Instruments and approaches for assessing and profiling labor program applicants 192

Maps

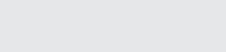

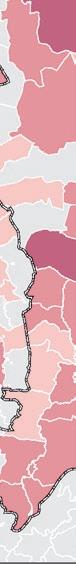

S1.1.1 Footprints of expanding new and old PSNP programs in Ethiopia 24

8.1 Internally displaced persons in Ethiopia, by zone 160

8.2 Number of internally displaced people in the northern Ethiopian crisis, by woreda 162

Tables

B1.2.1 Comparison of household income sources, Ethiopia and selected countries, 2019 12

2A.1 Field, field manager, and household characteristics, by gender of field manager, rural Ethiopia 48

2A.2 Gender gap in agricultural productivity, Blinder–Oaxaca decomposition results, rural Ethiopia 49

2B.1 Difference in enterprise, household head, and household characteristics of NFEs, by gender of manager, rural Ethiopia 51

2B.2 Gender gap in NFE sales, Blinder–Oaxaca decomposition results, rural Ethiopia 52

2C.1 Individual and household characteristics of wage-employed population, by gender, rural Ethiopia 53

2C.2 Gender gap in hourly wage, Blinder–Oaxaca decomposition results, rural Ethiopia 54

Contents | ix

3.1 Although starting from a low base, Ethiopia’s global innovator ser vices subsector has had encouraging jobs growth, 2004−20 66

5A.1 Probit model on determinants of migration across PSNP and non-PSNP areas in Ethiopia 108

8.1 Overlap of safety nets and displaced populations in Ethiopia, in millions of individuals 169

9.1 Overview of labor program categories 184

B9.6.1 Sample entrepreneurship aptitude test questions 194

9.2 Taxonomy of labor programs for selected risk groups 202

9.3 Labor program performance indicators 209

x | W ORKING T ODAY FOR A B ETTER T OMORROW IN E THIOPIA

Acknowledgments

The editors and chapter authors are grateful to the extensive team who wrote and contributed to this report. Special thanks to Robert Chase, Ousmane Dione, and Andrea Vermehren for their guidance, leadership, and vision in prioritizing and developing this report. Luc Christiaensen and Wendy Cunningham provided thoughtful peer review guidance on the original policy note and the report’s overarching framework and findings. We also appreciate the support of Christabel Dadzie, Ayuba Hussein, Michael Munavu, and Suleiman Namara throughout the preparation of this report. Candace Gebre wrote the spotlight on climate-smart self-employment, Carter Dougherty edited the report, and Jihane El Khoury Roederer designed the cover art.

The editors and chapter authors thank the following peer reviewers and providers of analytical support and general guidance: Girum Abebe, Tirsit Amha, Niklas Beuren, Berhe Mekonnen Beyene, Tom Bundervoet, Joanna de Berry, Alan de Brauw, Gustavo Demarco, Jymdey Mercedes Yeffimo Garcia, Paula Gonzalez, Melis Guven, Adiam Hagos Hailemicheal, Janet Heisey, Christian Meyer, Theodros Hailemariam Nigatu, Lucian Bucur Pop, Wout Soer, Roman Tesfaye, Samuel Weldeegzie, Christina Wieser, and Tesfaye Workineh. The editors and chapter authors also thank colleagues who provided thoughtful feedback and constructive inputs.

The chapter authors are as follows:

• Chapter 1, “The Challenges of Job Growth in Ethiopia,” was written by Koen Maaskant, Berhe Mekonnen Beyene, and Obert Pimhidzai.

• Chapter 2, “Women in Rural Jobs: Constraints to Productivity,” was written by Barbara Coello and Bezawit Adugna Bahru.

• Chapter 3, “Youth Employment in Urban Ethiopia: Aspirations in the Labor Market,” was written by Koen Maaskant.

• Chapter 4, “Disability and Work in Ethiopia: Supporting Access to Good Jobs,” was written by Simon Narbeth and Andrey Tretyak.

• Chapter 5, “Safety Nets and Labor Migration: Influencing, but Not Deterring, Urban Migration,” was written by Daisy Demirag.

• Chapter 6, “Creating Small Enterprise and Microenterprise Jobs in Ethiopia: The Role of Social Safety Nets,” was written by Margaux Vinez, Blene A. Betemariam, and Natnael Simachew Nigatu.

xi

• Chapter 7, “Wage Employment Interventions in Ethiopia’s Social Safety Net Programs: Matching Poor Workers to Wage Jobs,” was written by Koen Maaskant, Natnael Simachew Nigatu, and Margaux Vinez.

• Chapter 8, “Conflict, Displacement, and Livelihoods in Ethiopia: Role of Social Protection,” was written by Aditya Sarkar, Alfredo Manfredini Böhm, and Fasil Mulatu Gessesse.

• Chapter 9, “Labor Market Delivery Systems for Ethiopia and Beyond: A Framework Approach,” was written by Inés Rodríguez Caillava, Carola Gruen, Koen Maaskant, and Indhira Santos.

The editors further acknowledge the support of the Austrian Development Cooperation, the European Union, German Cooperation for International Cooperation, Global Affairs Canada, the Government of Ireland International Development Programme, KfW Development Bank, the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the Royal Danish Embassy, Sweden, the United Kingdom Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, UNICEF, USAID, the World Food Programme, and the World Bank.

These thanks and appreciation are noted without implication. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions herein are those of the editors and authors, not necessarily those of colleagues consulted in the preparation of the report.

xii | W ORKING T ODAY FOR A B ETTER T OMORROW IN E THIOPIA

About the Editors and Authors

ABOUT THE EDITORS

Emily Weedon Chapman is a senior human development economist at the World Bank. Her work focuses on human capital development, particularly jobs and livelihoods; human capital and climate change; women’s empowerment; nutrition; and governance and transparency in the delivery of basic services. She has managed World Bank Social Protection and Jobs lending portfolios in Ethiopia, Liberia, and Zambia and engaged in policy dialogue with and technical assistance for other governments in Africa and the Middle East. Her research includes qualitative methods to understand productive inclusion through human-centered design. Emily has an MA in international development from The George Washington University and a BA in international relations from Colgate University.

Margaux Vinez is a senior economist in the World Bank’s Social Protection and Jobs Global Practice Group. She works with governments in East and West Africa to support the design, implementation, and evaluation of programs in social protection, productive inclusion and jobs, shock-responsive safety nets and climate change, and food security and agriculture. She is currently working on a range of operations and research activities in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Mauritania, and in the Sahel region. She has a master’s degree in management from HEC Paris and a PhD in economics from the Paris School of Economics.

ABOUT THE CHAPTER AUTHORS

Bezawit Adugna Bahru is a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Hohenheim and an EASST fellow at the Center for Effective Global Action, University of California at Berkeley. She uses survey data and large-scale experiments to study the transformative effects of social protection programs and gender differences in agricultural productivity, time poverty, and women’s economic empowerment. Her current work focuses on Ethiopia, Indonesia, and Uganda. Bezawit has a PhD in agricultural economics from the University of Hohenheim.

xiii

Blene A. Betemariam is a skills and labor consultant with the World Bank’s Social Protection and Jobs East Africa Practice. She has supported the Ethiopian government around human capital and workforce development as an adviser with more than 20 years of combined experience as a program designer, developer and evaluator, educator, and operational manager in various environments. Blene has a PhD in education and leadership from Lynn University and an MBA from American International University.

Berhe Mekonnen Beyene is a senior economist in the World Bank’s Poverty and Equity Global Practice. He is an applied development economist whose areas of expertise include poverty analysis, migration, labor market, and program evaluation. Previously, he served as a consultant and researcher for various organizations in Ethiopia, including the Ethiopian Development Research Institute and United National Development Programme. He was a visiting scholar in the department of sociology at the University of California at Berkeley and a postdoctoral research fellow at the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Berhe has a PhD in economics and an MPhil in environmental and development economics from the University of Oslo.

Alfredo Manfredini Böhm is an applied development economist in the World Bank’s Social Protection and Jobs East Africa Practice. His most recent work in Ethiopia and the Republic of Congo focused on researching and supporting the implementation of safety-net responses, promoting social cohesion, and expanding economic opportunities for refugees, internally displaced persons, and their hosting populations. He has worked as an economic adviser for the government of the United Kingdom in transport, local development, and agricultural trade and for Ethiopia’s Export Committee of the Prime Minister’s Office in trade and logistics policy. Alfredo has an MPhil in economic research from the University of Cambridge and a BA in philosophy.

Inés Rodríguez Caillava is a social protection specialist in the World Bank’s Social Protection and Jobs Global Practice. She is a core team member of the Delivery Systems Global Solutions Group, contributing to the global knowledge program on delivery systems. She coauthored the Sourcebook on the Foundations of Social Protection Delivery Systems (2020). She also has worked on social safety net programs and delivery systems in Angola, Burkina Faso, Djibouti, GuineaBissau, Mozambique, Peru, and the Republic of Congo. Inés has a BA and an MA in international relations from the Universidad de San Andrés and an MA in international development from The George Washington University.

Barbara Coello is a rural economist who has worked for the World Bank and other international institutions for more than a decade. The focus of her work relates to food systems at the nexus of agriculture, food security, and gender. She has worked in different regions on the design of operations, implementation, and evaluation. A French and Spanish national, Barbara has a PhD in development economics from the Paris School of Economics.

Daisy Demirag is an economist within the World Bank’s Human Capital Project. Previously, as a member of the World Bank’s Social Protection and Jobs team she worked in the South Asia Region and the East Africa Region, focusing on Bangladesh, Nepal, and Ethiopia, respectively. She has written on the linkages between social protection and migration, as well as on occupational choices of returning migrants. Daisy is a PhD researcher at Maastricht University.

xiv | W ORKING T ODAY FOR A B ETTER T OMORROW IN E THIOPIA

Candace Gebre is a writer and communications consultant for the World Bank’s Social Protection and Jobs Team in Ethiopia. She previously provided a range of communications support (writing, graphic design, and editorial) for various projects in the Energy, Water, Governance, and Poverty Global Practices. Candace has studied comparative literature and Africana studies at New York University and has an MFA in creative writing from Hollins University.

Fasil Mulatu Gessesse holds a teaching position at Addis Ababa University’s Centre for Human Rights (CHR) and is the chair of the CHR. His areas of expertise include human rights protection, children’s rights, migration law, refugee law, and human-trafficking law. He is a former visiting scholar at the University of Antwerp, the University of Graz, and the University of Lund, and has worked with the German Corporation for International Cooperation, Save the Children, the International Organization for Migration, the Norwegian Refugee Council, UNICEF, and World Bank in different capacities. Fasil has a PhD in human rights law from the University of Western Cape, South Africa.

Carola Gruen has served as a senior consultant in the World Bank’s Social Protection and Jobs Global Practice since 2014. An applied labor economist, she has provided analytical and policy support to client countries in Africa, East Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, and South Asia, focusing on issues such as labor market disparities, job quality, employment promotion, informality, and underemployment. Carola has a PhD in economics from the University of Munich.

Koen Maaskant is a consultant in the World Bank’s Social Protection and Jobs Global Practice, focusing on the jobs analytical agenda and related operational projects in Ethiopia, South Africa, and globally. He has worked in Ethiopia in different roles for government and development partners, including as an ODI Fellow at the Ethiopian Investment Commission, where he coordinated several donor projects and sector strategies. Before his work for the government of Ethiopia, he managed a randomized controlled trial on labor market interventions in Addis Ababa for the University of Oxford. Koen has an MA in economics for development from the University of Oxford and a BA in economics and political science from University College Roosevelt.

Simon Narbeth was a senior social protection specialist at the World Bank. Before joining the World Bank, he was a senior social development adviser for the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. He has worked across Africa, Asia, and the Balkans region, focusing on social inclusion in support of social development and social protection policy and reforms. Simon has a DPhil in human geography from the University of Bristol.

Natnael Simachew Nigatu is a consultant in the World Bank’s Social Protection and Jobs Global Practice. His current research focuses on the intersections of international trade and labor economics, online gig work, and youth employment. Before joining the World Bank, he worked as a postdoctoral researcher at Lund University, where he taught advanced courses in economic integration. In addition, he was a visiting scholar at Purdue University. Natnael has a BA in economics from Bahir Dar University and an MA and a PhD in economics from the University of Copenhagen.

Obert Pimhidzai is the lead economist in the World Bank’s Poverty and Equity Global Practice in Europe and Central Asia. He has extensive experience

About the Editors and Authors | xv

supporting World Bank analytical and technical assistance programs on povertyand equity-related issues. He has led pioneering project financing in statistical capacity building such as statistical modernization in Viet Nam and large multicountry statistics projects such as the Eastern Africa Regional Statistics Project, and he has contributed to the design of anti-poverty programs in low- and middle-income countries in Africa and East Asia. Obert has a PhD in economics from the University of Cape Town.

Indhira Santos is a senior economist at the World Bank, coordinating the human capital agenda in the Western Balkans. She is a specialist in labor markets, skills, and social protection. During her career at the World Bank, she has been the global lead for labor and skills and has worked on the Africa, Europe and Central Asia, and South Asia Regions since joining as a young professional in 2009. She also is a primary author of the World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work, and the World Development Report 2016: Digital Divides. Before joining the World Bank, she was a research fellow at Bruegel, a European policy think tank in Brussels, and worked for the Economic Research Center of Pontificia Universidad Católica Madre y Maestra and the Ministry of Finance in the Dominican Republic. A Fulbright Scholar, Indhira has an MA in public administration in international development and a PhD in public policy from Harvard University.

Aditya Sarkar is a PhD candidate at the Fletcher School at Tufts University and is an independent researcher. He has advised the International Labour Organization and the governments of Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan on developing national employment policies and has consulted with the World Bank and the Open Society Foundations. He is qualified as a lawyer in England, India, and Wales. He previously worked with Linklaters LLP, a global law firm, in London, as well as with the Ministry of Commerce in India. Aditya has an MA from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University and is a graduate of the National Law School of India University.

Andrey Tretyak is a senior social protection specialist at the World Bank and is leading the work of disability inclusion in social protection and jobs in line with World Bank commitments. He has worked in the French social protection system for more than 20 years, with a focus on international cooperation projects supporting the expansion of social protection coverage. He has led the Social Protection and Decent Work Unit in Expertise France since 2015. Andrey has a PhD in economics focused on the impact of budgetary policies and speed of reforms on the economic growth and countries’ development.

xvi | W ORKING T ODAY FOR A B ETTER T OMORROW IN E THIOPIA

Executive Summary

INTRODUCTION

The government of Ethiopia prioritizes the jobs agenda in the country, but broadbased job creation remains elusive. Helping poor and vulnerable workers earn more in today’s labor market will require new efforts. Ethiopia’s 10-year Perspective Development Plan (2021–30) and National Plan for Job Creation (2020–25) recognize the country’s limited job growth and, as the 10-year plan says, make a “paradigm shift from state-led to private-sector-led growth.” The National Plan for Job Creation prioritizes job-rich macroeconomic policies, local enterprise development, and human capital development. What the 2021 Labor Force Survey (LFS) data lay clear, however, is that these policies are a long-term prospect. Creating an inclusive labor market—another priority of the National Plan for Job Creation—requires understanding the constraints of poor and vulnerable workers and supporting them within the realities of the current economy.

Since 1999, the structure of the Ethiopian labor market has changed incrementally. The 2021 LFS confirms prepandemic, preconflict data showing that widespread poverty reduction or expanding job opportunities did not accompany the country’s sustained economic growth. It also suggests that the concurrent crises facing Ethiopia may have reinforced the disconnect between economic growth and some agricultural productivity increases on the one hand and stagnant income levels, particularly in rural areas, on the other.

To promote more inclusive growth while long-term reforms take hold, the jobs agenda must invest in near-term measures to improve worker productivity in and connect people to jobs that already exist, such as in the service sector. Such policies can have meaningful near-term impacts and help Ethiopians get more out of currently available opportunities. Moreover, global evidence increasingly shows that employment in the service sector can also contribute to inclusive economic growth.

Ethiopia’s safety net programs present a platform to reach the working-poor population with targeted and tailored financing, training, networking, and other support that can increase their earnings. If implemented alongside macroeconomic reforms, social safety nets that adopt these complementary measures can promote self-employment productivity and links to existing wage jobs that reinforce long-term efforts toward structural transformation of the Ethiopian economy.

xvii

LABOR MARKET OVERVIEW

Job opportunities in Ethiopia have shifted slowly over the past two decades. The 2021 LFS is the first such survey since 2013 and provides insights on national labor market trends since 1999, including preliminary impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the conflict in Northern Ethiopia (refer to box 1.1 in chapter 1 for detailed information on LFS methodologies).

In 2021, like 1999, low-skilled self-employment was the most common type of work (refer to figure ES.1). Only 14 percent of Ethiopians held wage jobs in 2021, up just 5 percentage points from 1999. By contrast, 54 percent were selfemployed—39 percent in agriculture and 15 percent in nonagriculture. An even smaller shift occurred in the skill level of work. In 2021, 74 percent of workers had low-skill jobs as compared to 77 percent in 1999.

This labor market stagnation juxtaposes a nearly 40 percent increase in Ethiopia’s gross domestic product and a rise in agricultural yields since 2004. Maize yields more than doubled between 2004 and 2019; however, teff, which makes up the largest portion of the food basket, saw the slowest yield growth of cereals, increasing only 9 quintals per hectare over the same period (Dorosh and Minten 2020). Labor market stagnation and limited yield increases in key cereals may help contextualize why poor rural households have not experienced any increase in real income levels over the past 10 years (World Bank 2022b).

Now, concurrent crises have eroded economic growth trends and threaten negative repercussions within the labor market. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic closed markets, albeit relatively briefly, and had immediate, negative impacts on job opportunities. In 2021, real GDP growth contracted to 3.5 percent as the country dealt with the implications of the pandemic, the conflict in Northern Ethiopia, and severe drought (World Bank 2022b). Most recently,

xviii | W ORKING T ODAY FOR A B ETTER T OMORROW IN E THIOPIA

FIGURE ES.1

Low-skill self-employment remains the most common type of work in Ethiopia

Those classified as “employer”

owner-managers

businesses. Wage employee Self-employed (agriculture) Unpaid family worker Self-employed (nonagriculture) Employer Other Low Medium High Percent 0 20 40 60 80 100 b. Skill composition of employment, 1999–2021 Percent 0 20 40 60 80 100 a. Terms of employment, 2005–21 10 30 50 70 90 10 2005 2021 2013 1999 2021 20052013 30 50 70 90

Source: World Bank calculations using data from the Ethiopia Labor Force Survey, 1999–2021. Note:

are

of

global shocks have worsened food insecurity and contributed to high inflation, which was roughly 32 percent in Ethiopia as of October 2022 (World Bank 2022a).

Against this backdrop, the service sector is the one area of recent job growth, but it barely accommodates new labor market entrants. Nearly 3.5 million jobs were added in the service sector between 2013 and 2021 (refer to figure ES.2). By contrast, the agriculture and industrial sectors lost about 2 million and 0.5 million jobs, respectively. Moreover, between 2013 and 2021, wage employment grew only 2.9 percent, compared to growth of 7.4 percent between 2005 and 2013. Notably, the trends in decreasing growth of industrial and wage jobs predate the COVID-19 pandemic (Ambel et al. 2021).

The 2021 LFS shows that, over the same period, unemployment has increased (refer to figure ES.3), and people are leaving the labor market altogether. This trend could be due to the COVID-19 pandemic, conflict, and other crises affecting work opportunities. Better understanding of these trends will require further labor market data. Regardless of its cause, however, even a relatively short period of unemployment can reduce income levels for up to a decade afterward. Less-educated workers can take longer to recover. Recent data from high-frequency telephone surveys on COVID-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa, including Ethiopia, found that, one year after the pandemic, education levels were the strongest predictor of whether a household had rejoined the labor market (Ambel et al. 2021).

All workers need labor market policies tailored to the jobs currently available in the Ethiopian labor market—or they need support to invest in creating job opportunities through productive self-employment. Efforts should also support labor mobility and increase labor market participation. These interventions can help improve productivity and earnings in the near term while contributing to services-led structural transformation in the longer term (Diao et al. 2021; Nayyar, Hallward-Driemeier, and Davies 2021).

Executive Summary | xix

FIGURE ES.2

Source:

Agriculture Industry Services b. Net job creation, by sector, 2005–21 Percent Millions 0 20 40 60 80 100 a. Sectoral employment composition, 1999–2021 –3.0 0 3.0 6.0 9.0 –1.5 1.5 4.5 7.5 10 1999 2021 2013 2005 2005–13 2013–21 30 50 70 90

Ethiopia has seen slow shifts in its labor market, with services as the only growth sector

World

Bank calculations using data from the Ethiopia Labor Force Survey,

1999–2021.

FIGURE ES.3

Unemployment in Ethiopia has almost doubled since 2013, with women and rural areas hardest hit

BARRIERS TO GOOD JOBS

Within this context, vulnerable groups face additional and distinct barriers to improving their productivity or finding available jobs. The work experiences of rural women, urban youth, people with disabilities, and rural–urban migrants offer useful information for understanding how to tailor job policies to people’s specific needs. Because these four groups represent about half the Ethiopian population, the policy implications of including them in more productive jobs go well beyond the traditional reach of social safety net programs, which target the poorest decile in Ethiopia. Success in helping these groups can inform policies to encourage broad-based, inclusive job opportunities.

Rural women

Rural women make up 40 percent of the Ethiopian population, but only 34 percent of these women are active in the labor market, nearly identical to the proportion in 1999. Family responsibilities and pregnancy impede about 85 percent of women ages 25–44 from seeking jobs, whereas such responsibilities affect less than 35 percent of men. When women do work, they earn only 73 percent of what men do (refer to figure ES.4). Time constraints play a role, but lack of productive inputs, such as access to land or financial services, is the largest driver of women’s low productivity. Low education is another barrier: 61 percent of rural women have no schooling as compared to 34 percent of rural men.

Urban youth

Urban youth also face challenges in finding good jobs. Ethiopia will have an estimated 54 million youth by 2050, up from 34 million in 2020. Following current trends, in which more than 70 percent of young people do not advance beyond primary school and only 20 percent reach tertiary education, this

xx | W ORKING T ODAY FOR A B ETTER T OMORROW IN E THIOPIA

Source: World Bank calculations using data from the Ethiopia Labor Force Survey, 1999–2021.

2021 1999 2021 1999 2013 2005 20052013 0 10 20 25 5 15 Percent 0 10 20 25 5 15 Percent

Note: This figure uses the relaxed unemployment definition, counting people as unemployed if they are without work and available for work.

a. Unemployment rate, by location, 1999–2021

b. Unemployment rate, by gender, 1999–2021

Urban Rural National Men Women National

population will be unprepared for the labor market. Currently, 75 percent of working urban youth have jobs in services and mostly in low-skill domestic work (refer to figure ES.5). Within services, global innovator jobs—such as in finance, information and communication technology, and scientific fields— grew more in urban areas in percentage terms between 2004 and 2020 than any other service sector, albeit from a low base. This subsection of service jobs has the highest potential to contribute to structural transformation of the economy. Not surprisingly, the skills required for this caliber of job correlate directly with education levels.

Other challenges for youth include unemployment and inactivity. Youth unemployment is on the rise, and the increasing number of youths not in education, employment, or training reveals further gender disparities in the labor market. Young women are three times more likely to be inactive than young men (refer to figure ES.6). Data showing these trends come from the 2020 Urban Employment Unemployment Survey, which predates the COVID-19 outbreak and other crises now affecting the Ethiopia economy.

People with disabilities

Employment and decent work can break the cycle of poverty and exclusion for people with disabilities. Limited data exist on this population, and even estimates of the number of people with disabilities are unreliable, ranging from 1 percent to nearly 20 percent of the population. Nevertheless, the available data show that people with disabilities are poorer, less educated, and less likely to be employed. Enabling self-sufficiency is an important factor in restoring dignity.

Rural−urban migrants

Ethiopia has few rural–urban migrants. Between 2016 and 2021, only 6 percent of adults migrated, mostly to small towns. Nevertheless, internal migration has the potential to promote job opportunities, including for poor households. The country’s rural safety net does influence migration decisions, suggesting that the government could leverage this program to open pathways for rural people into better jobs.

Executive Summary | xxi

FIGURE ES.4

Across all sectors, women in Ethiopia earn less per month than men Monthly earnings, by gender and sector, 2021

Agriculture 1.9 1.3 4.3 4.9 3.6 2.7 Ethiopian birr (thousands) Industr yServices 6 4 2 0

Source: World Bank calculations using data from the Ethiopia Labor Force Survey, 2021.

Men Women

FIGURE ES.6

Within Ethiopia’s service sector, most urban youths work in low-skill domestic jobs

Source: World Bank calculations using data from the Ethiopia Urban Employment Unemployment Survey, 2020. Note: Global innovator services include finance; information and communication technology; and professional, scientific, and technical activities. Low-skill tradable services include transportation and storage, accommodation and food, and wholesale trade. Skill-intensive social services include education and health. Low-skill domestic services include retail trade; administrative and support; arts, entertainment, and recreation; and social, community, and personal services.

Young people, particularly young women, are increasingly leaving the Ethiopian labor market

a. LFPR, youth vs. rest of labor market, 2006–20

b. Number of youths, by activity status and gender, 2020

Source: World Bank calculations using data from the Ethiopia Urban Employment Unemployment Survey, 2006–20. Note: LFPR = labor force participation rate.

DIVERSIFYING SELF-EMPLOYMENT JOBS

Creating opportunities and increasing productivity in self-employment remain an untapped pathway for better, more profitable work for many Ethiopians. Selfemployment, largely in microenterprises, provides an important opportunity for poor households to earn more and build resilience. In rural areas, agriculture accounts for 87 percent of self-employment, with the small remaining share of

xxii | W ORKING T ODAY FOR A B ETTER T OMORROW IN E THIOPIA

FIGURE

ES.5

Number of youths with jobs in service subsectors, 2006–20

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 2006200820102012201420162018 2020 Millions Global innovator services Low-skill tradeable services Skill-intensive social services Low-skill domestic services

Youth (ages 15–29) Rest of labor market (ages 30–64) 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 200620082010 Percen t 20122014201620182020 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4 1.6 Not working, not in school In school Working and in school Working only Millions 30% 24% 9% 37%

Female youth Male youth

employment in petty trade or personal services. In urban areas, self-employment is more diverse, split among trade (which is most common), services, and agriculture.

Diversification of income sources is closely linked to higher incomes and greater income resilience to shocks in Ethiopia (refer to figure ES.7). In the past decade, diversification into self-employment and the service sector helped drive poverty reduction in urban areas (World Bank 2020).

Social safety nets offer a concrete policy entry point to support people in diversifying their work activities to include microenterprise income. Global evidence, as well as small-scale interventions in Ethiopia, show that safety nets can effectively promote self-employment. A pilot program in Ethiopia catalyzed nearly 20 percent increases in the consumption of involved households (Banerjee et al. 2015). Productive economic inclusion uses the social safety net platform as a starting point to leverage self-employment opportunities. The project design adopts a comprehensive package of support, including training in life, business, and financial skills; capital infusions, whether through grants to improve access to credit or through savings options; psychosocial support; and often networking or mentoring opportunities.

Unfortunately, large-scale self-employment programs in Ethiopia have struggled. Their financing repeatedly shifts to cash transfers in the face of innumerable, recurrent crises. These programs face challenges in implementation, too. For example, nearly all rural clients have invested in livestock for savings rather than in productive activities. Social safety nets need to redouble efforts to promote and raise awareness of opportunities for nonfarm enterprise development, both in services and in agriculture. Success requires that support matches the unique barriers faced by different people and in different regions.

Wealthier households in Ethiopia have more diversity in how they earn a living

Source of household income, by sector and income quintile, 2016

Executive Summary | xxiii

ES.7

FIGURE

Sources: World Bank calculations using data from the Ethiopia Household Income, Consumption, and Expenditure Survey, 2016, and Welfare Monitoring Survey, 2016. Percent 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 Quintile 1Quintile 2Quintile 3Quintile 4Quintile 5 Other Hotels and restaurants Construction Manufacturing Transportation and storage Private households with employed person Other community social and personal services

and retail trade Mining Agriculture, forestry, and hunting

Wholesale

A durable solution: Livelihoods for internally displaced people in Ethiopia

Conflict and internal displacement have upended the livelihoods of millions of Ethiopians. In 2021, conflict displaced 5.1 million Ethiopians, the highest annual figure recorded for a country since 2003 (IDMC 2022).

Although they fear insecurity and a lack of livelihoods, most displaced individuals want to return home. During displacement, they rely on sparse food and cash distributions, as well as donations from the host community.

Efforts to support livelihood recovery for these Ethiopians could help during displacement, offering

income-generating opportunities and improving overstretched public infrastructure. Such efforts could also encourage return, helping people recover productive assets often lost during displacement.

In response to the conflict in Northern Ethiopia, the government of Ethiopia quickly retooled the urban safety net to provide cash to the displaced. With additional focus on self-employment and strengthening delivery systems of the country’s safety net programs, future efforts could more effectively reach the hardesthit individuals and facilitate the recovery of their livelihoods.

A harmonized framework for self-employment support could benefit the poor and nonpoor, rural and urban populations, as well as internally displaced people (refer to box ES.1). Such a framework, underpinned by strong delivery systems, can standardize the quality of programming and crowd in various actors—government, development partners, and civil society—financing these programs to maximize coverage and impact at scale. A holistic economic inclusion program would offer direct and immediate benefits to Ethiopian workers and create a multiplier effect that promotes broader local economic development (Andrews et al. 2021; Gassmann et al. 2023).

LINKS TO WAGE EMPLOYMENT

Wage employment remains out of reach for most Ethiopians. In 2021, wage work accounted for 14 percent of the labor market—up only 5 percentage points since 1999. Private sector firms employed just 1.6 million Ethiopians.

However, in some places—not only Addis Ababa but also small towns and cities—firms are currently looking for wage workers. Social safety nets can help bridge the gap between these employers and potential employees. Active labor market programs can help overcome information gaps, by connecting workers to existing jobs; skill gaps, by providing targeted training to workers; and location mismatches, by providing transportation subsidies. Like those for self-employment, active labor market programs for wage employment appear most successful when delivered as a multidimensional package of services (refer to figure ES.8).

SAFETY NETS CAN IMPROVE JOB OUTCOMES TODAY

Ethiopia’s 10-year Perspective Development Plan (2021–30) and National Plan for Job Creation (2020–25) demonstrate the government’s commitment to job creation. The World Bank’s 2022 Country Economic Memorandum reinforces that labor mobility and broader participation in the labor market are key to

xxiv | W ORKING T ODAY FOR A B ETTER T OMORROW IN E THIOPIA

BOX ES.1

A multidimensional package of services

Economic inclusion programs for self-employment

Capital grants

Business, financial, and life skills

Savings support

Networking

Mentoring

Active labor market programs for wage employment

Apprenticeships

Mobility grants

Skills training

Networking

Ethiopia’s continued growth and to making that growth more inclusive (World Bank 2022b). The labor market trends highlighted by the 2021 LFS show the need for Ethiopia to find job policies that complement longer-term reforms with near-term investments to achieve these objectives.

Investing in social safety nets can leverage better and more inclusive job outcomes in the near term. Social safety nets in Ethiopia already reach the poorest and have the tools to help them overcome the barriers they face in accessing better jobs. In self-employment, people often need relatively small levels of targeted and comprehensive support to increase their income levels. Providing capital grants or access to credit, alongside targeted financial and business training as well as mentoring and networking, can have lasting impacts. In wage work, evidence shows that support for mobility or a first work experience alongside training can improve access to wage work.

It is not just poor individuals who need this help. Most Ethiopian workers remain in low-productivity jobs and face similar barriers—whether lack of skills, capital, or networks—to improving their income opportunities.

Social safety nets also complement long-term job growth policies. These programs meet Ethiopian workers in the reality of today’s labor market. Through targeted support for self-employment productivity and connecting people with existing wage jobs, they can increase earnings and help shift the nature of work in the near term (refer to figure ES.9).

ABOUT THIS PUBLICATION

Working Today for a Better Tomorrow in Ethiopia: Jobs for Poor and Vulnerable Households provides further evidence and analysis about investing in today’s labor market to improve productivity and earnings in the jobs currently available to poor and vulnerable Ethiopians. Structured in three parts, the first part of the book analyzes Ethiopia’s labor market by comparing the latest 2021 LFS with LFS data from 1999, 2005, and 2013. The second part explores the unique challenges that

Executive Summary | xxv

FIGURE ES.8

Job support activities complement cash transfers for better labor outcomes in Ethiopia

Source: This figure is original to this publication.

FIGURE ES.9

From productive safety nets to productive jobs in Ethiopia

Self-employment generation

Social safety net systems

Capital Labor mobility Skills

Social support

Increased microenterprises

Labor market intermediation

Capital Labor mobility Skills

Networks

Improved labor productivity

Inclusive labor markets

Improved access to wage employment

Broad-based income growth

Poverty reduction

Service-led structural transformation

poor and vulnerable people face in securing good jobs. Rural women, urban youth, people with disabilities, and migrants make up about half of the Ethiopian population. Although not necessarily poor, they are prone to vulnerability in the labor market. The third and final part describes how social safety net programming can increase earnings and productivity of the poor population while simultaneously promoting inclusive and sustainable development in Ethiopia.

REFERENCES

Ambel, A. A., C. Sosa, L. Marcela, W. Y. Kassa, A. H. Tsegay, and C. Wieser. 2021. Monitoring COVID-19 Impacts on Households in Ethiopia: How COVID-19 Is Affecting Households— Results from the High-Frequency Phone Surveys of Households from April 2020 through January 2021. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Andrews, C., A. de Montesquiou, I. Arevalo Sanchez, P. Vasudeva Dutta, B. Varghese Paul, S. Samaranayake, J. Heisey, T. Clay, and S. Chaudhary. 2021. The State of Economic Inclusion Report 2021: The Potential to Scale. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Banerjee, A., E. Duflo, N. Goldberg, D. Karlan, R. Osei, W. Parienté, J. Shapiro, B. Thuysbaert, and C. Udry. 2015. “A Multifaceted Program Causes Lasting Progress for the Very Poor: Evidence from Six Countries.” Science 348 (6236). https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126 /science.1260799

Diao, X., M. Ellis, M. McMillan, and D. Rodrik. 2021. “Africa’s Manufacturing Puzzle: Evidence from Tanzanian and Ethiopian Firms.” NBER Working Paper 28344, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Dorosh, P. A., and B. Minten, eds. 2020. Ethiopia’s Agrifood System: Past Trends, Present Challenges, and Future Scenarios. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Gassmann, F., U. Gentilini, J. Morais, C. Nunnenmacher, Y. Okamura, G. Bordon, and G. Valleriani. 2023. “Is the Magic Happening? A Systematic Literature Review of the Economic Multiplier of Cash Transfers.” Policy Research Working Paper 10529, World Bank, Washington, DC.

xxvi | W ORKING T ODAY FOR A B ETTER T OMORROW IN E THIOPIA

Source: This figure is original to this publication.

IDMC (Internal Displacement Monitoring Center). 2022. “Figures Analysis 2021—Ethiopia: Displacement Associated with Conflict and Violence.” Fact Sheet. https://www.internal -displacement.org/sites/default/files/figures-analysis-2021-eth.pdf

Nayyar, G., M. Hallward-Driemeier, and E. Davies. 2021. At Your Service? The Promise of Services-Led Development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 2020. Ethiopia Poverty Assessment: Harnessing Continued Growth for Accelerated Poverty Reduction. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 2022a. Ethiopia—Rural Income Diagnostics Study: Leveraging the Transformation in the Agri-Food System and Global Trade to Expand Rural Incomes. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 2022b. Ethiopia’s Great Transition: The Next Mile—A Country Economic Memorandum. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Executive Summary | xxvii

Abbreviations

ALMP active labor market policy

Br Ethiopian birr

CBHI community-based health insurance

CRPD Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

DA development agent

DTM Displacement Tracking Matrix

EA enumeration area

EAT entrepreneurship aptitude test

ESA emergency site assessment

ESS Ethiopian Socioeconomic Survey

FGD focus group discussion

GDP gross domestic product

GRM grievance redress mechanism

IAP individualized action plan

IDP internally displaced person

ILO International Labour Organization

IOM International Organization for Migration

LFPR labor force participation rate

LFS Labor Force Survey

LIC low-income country

LMIS labor market information system

M&E monitoring and evaluation

MFI microfinance institution

MIC middle-income country

NEET not in education, employment, or training

NFE nonfarm enterprise

NITA National Industrial Training Authority

PES public employment service

PPP purchasing power parity

PSNP Productive Safety Net Program

SA site assessment

SACCO saving and credit corporation

SDG United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

SSN social safety net

xxix

TPLF Tigray People’s Liberation Front

TVET technical and vocational education and training

UPSNJP Urban Productive Safety Net and Jobs Project

UPSNP Urban Productive Safety Net Project

VAS village assessment survey

WEP wage employment pathway

WHO World Health Organization

xxx | W ORKING T ODAY FOR A B ETTER T OMORROW IN E THIOPIA

I Ethiopian Labor Market

1

The Challenges of Job Growth in Ethiopia 1

SUMMARY*

The Ethiopian labor market has experienced limited change in the past two decades. Job policies need to recognize this reality and include a focus on improving productivity in and connecting people to jobs that already exist. If adopted in parallel with reforms to promote long-term structural transformation, these two objectives can be mutually reinforcing.

• Ethiopia experienced steady economic growth for much of the past two decades. Yet, even before the concurrent crises now facing the country, economic growth did not transform the structure of the labor market, nor did it reduce rural poverty. The latest labor force data suggest that these crises have compounded the challenges that people face in finding good jobs.

• Between the early 2000s and 2021, the distribution of workers across sectors and geographies shifted little. Eighty percent of the population lives in rural areas, where about 75 percent of people work in agriculture. In urban areas, about 70 percent of people work in services.

• The service sector added 3.5 million jobs to the economy between 2013 and 2021; however, job creation has barely matched new labor market entrants. Over this period, industry and agriculture lost a combined 2.3 million jobs. Earlier positive trends in manufacturing began reversing even before the pandemic and conflict.

• Nationally, self-employment accounts for about half of jobs, with unpaid family work the second most common type of employment and wage work a distant third. The urban context is different: wage employment is prevalent, although opportunities are not expanding.

• Unfortunately, the labor market shows rising unemployment and people leaving the labor market altogether. Whether this situation is temporary— resulting from today’s concurrent crises—or a longer-term trend requires

By Koen Maaskant, Berhe Mekonnen Beyene,

3

and Obert Pimhidzai. The authors thank, without implicating, Tom Bundervoet and Christina Wieser for their helpful feedback, and Samuel Weldeegzie for analytical support.

further data. Even if temporary, this issue will exacerbate underlying inequities in access to good jobs and earning levels.

• Within this context, vulnerable populations face unique barriers to quality work. On average, rural women, urban youth, people with disabilities, and rural–urban migrants are more likely to be inactive and less likely to have seen a positive change in how they earn their living in the past two decades.

• all workers, especially vulnerable populations, need labor market policies tailored to the jobs currently available in Ethiopia. Such interventions can help improve productivity and earnings in the near term while contributing to service-led structural transformation in the longer term.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past 15 years, Ethiopia’s gross domestic product (gdP) per capita increased nearly 40 percent but without widespread poverty reduction. Between 2004 and 2020, Ethiopia’s gdP grew, on average, 10 percent per annum and helped reduce the poverty level by about 10 percentage points. The benefits of that growth, however, were unequally realized. Much of the poverty reduction occurred in urban areas, where less than 20 percent of the population lives; the average rural household did not experience any increase in real income level (World Bank 2022b).

Since 2020, concurrent shocks have eroded the growth trends and have increased poverty levels across the country. In 2021, real gdP growth contracted to 3.5 percent as the country dealt with the implications of the COVId-19 pandemic. The conflict in Northern Ethiopia and other parts of the country further hurt the economy and people’s well-being, as did severe droughts in the lowland regions. as a result, nearly one-fifth of the population requires humanitarian assistance. More recently, global shocks have worsened food insecurity and contributed to high inflation, which was roughly 32 percent as of October 2022.

Likewise, improvements in the labor market over the past decade are limited, and even these marginal gains seem threatened by the negative repercussions of the concurrent crises. data from the 2021 Labor force Survey (LfS) show that the high and longstanding economic growth between 2004 and 2020 did not result in a structural transformation of Ethiopia’s labor market (for more on LfS, refer to box 1.1 on data sources and methodology). Shifts in employment productivity and types of employment were moderate at best. Then, in 2020, the COVId -19 pandemic closed markets, albeit relatively briefly, and had immediate negative impacts on job opportunities. although most workers reentered the labor market, many shifted their engagement, not necessarily in positive ways.

Between 2013 and 2021, the service sector drove limited job growth as employment in agriculture and industry shrank. Nearly 3.5 million jobs were added in the service sector between the last LfS in 2013 and the most recent one in 2021. By contrast, the agricultural and industrial sectors lost 1.7 million and 0.6 million jobs, respectively. Moreover, between 2013 and 2021, wage employment growth was less than half that between 2005 and 2013—2.9 percent compared to 7.4 percent. Notably, the trends in decreasing growth of industrial and wage jobs predate the COVId -19 pandemic.

at the same time, more people—rural women in particular—are unemployed or leaving the labor market altogether. Nationally, unemployment doubled

4 | W O r KIN g T O daY f O r a B ETTE r T OMO rr OW IN E T h IOPI a

Data sources and methodology

Labor Force Survey 2021

Ethiopia’s national Labor force Survey (LfS), which is nationally representative, is designed to estimate employment and unemployment outcomes at the regional level by rural, major urban, and other urban categories. across years, the survey has used a twostage cluster sampling procedure, with enumeration areas (E a s) as the primary sampling units and households as the secondary sampling units. The 2021 LfS adopted a new cartographic frame for the upcoming fourth Population and housing Census, whereas the 2013 L f S used the 2 007 Population and housing Census as the sampling frame.

The E a s were selected using the probability proportionate to size in the first stage selection, and 30 households per Ea were selected using a systematic sampling approach. a total of 1,686 Eas (766 major urban, 380 other urban, and 540 rural) were selected for the 2021 LfS, giving a target sample size of 50,580 households. The 2013 L f S sample had 1,955 E a s (817 major urban, 296 other urban, and 842 rural) with a target sample size of 58,650. L f S has very high response rates, exceeding 99 percent in all localities and across surveys over time.

differences in sample coverage between the 2013 LfS and 2021 LfS do not appear to influence comparability significantly. The 2021 LfS did not cover the Tigray region, because of the ongoing conflict, but did include the whole of the afar and Somali regions, despite insecurity in those areas. The 2021 LfS also included pastoralist populations, concentrated in the lowland areas of the country, which the 2013 LfS did not cover. The population sizes of both the pastoralists and the Tigray regions are too small to drive any

differences between the two surveys. regional comparisons also indicate similar patterns (although in varying magnitudes) in labor market trends across countries. Nonetheless, when computing trends, this report excludes earlier survey data on Tigray.

Seasonality represents a comparability concern between the 2013 and 2021 surveys. d ata were collected during the peak season (May and June) in 2013 but during the slack season (January and february) in 2021. a lthough the questionnaire is broadly comparable, seasonal variation could influence the observed trends between 2013 and 2021; thus, such comparison should be treated with caution.

Ethiopian Socioeconomic Survey 2018/19

The Ethiopian Socioeconomic Survey (ESS) is a multimodule panel survey to better understand the relationship among agriculture, household welfare, and poverty. The ESS 2018/19 was the fourth round of the survey in Ethiopia but adopted a new panel rather than a follow-up to previous ESS waves. It covered all nine states and two cities, addis ababa and dire dawa. representative at the regional level by rural or urban area, the ESS 2018/19 collected data from 535 E a s (316 rural and 219 urban) with 12 and 15 households selected per E a in rura l areas and urban areas, respectively. The total sample was 7,527 households, of which 6,894 were eventually interviewed.

The ESS 2018/19 has individual-level modules collecting information on

• Ownership and right to selected physical and financial assets, and

• Education, health, labor, and financial inclusion status.

between 2013 and 2021; in rural areas, the figure tripled. Women and youth both saw particularly sharp increases in unemployment. The decrease in the labor force participation rate (LfPr), from 86 percent in 2013 to 74 percent in the 2021 LfS, is also notable against a steady LfPr increase in the two previous surveys.

The Challenges of Job Growth in Ethiopia | 5

BOX 1.1

Note: The labor module was updated to reflect concepts and definitions endorsed by the 19th International Conference of Labour Statisticians in 2013, which covers employment, volunteering, own-use production, and unpaid training, among other forms of work. The survey also captures household consumption and participation in social assistance programs, which enables analysis of labor market outcomes by socioeconomic status.

Like unemployment, the rural labor market was much more affected than the urban one by falling LfPr, and these trends are particularly striking for women.

The relationship between this observed increase in unemployment and inactivity, COVId -19, the conflict in Northern Ethiopia, and other crises remains unclear. high-frequency telephone surveys on COVId -19, conducted in Ethiopia between april 2020 and april 2021, showed that the percentage of people working over the previous week rebounded within just months of the initial shutdowns and other preventive measures. Loss of income from nonfarm enterprises, however, recovered much more slowly over 2020 and then saw another significant drop when Ethiopia’s COVId -19 caseload rose significantly in early 2021 (ambel et al. 2021). This rise in caseload began at the same time as data collection for the 2021 LfS.

regardless of the situation’s cause or longevity, however, policy attention is critical to prevent economic scarring from unemployment or inactivity and to limit exacerbation of labor market inequalities. data from developed economies have shown that unemployment, whether idiosyncratic or linked to economywide events, can have holdover implications on future earnings for a decade (Nilsen and reiso 2011; rothstein and Kahn 2020). In Latin america, analysis of past crises has shown that this scarring exacerbates inequality, with incomes of better-educated households recovering much more quickly (Silva et al. 2021). The high-frequency telephone surveys seemed to confirm this finding: one year after the pandemic, education levels were the strongest predicator of whether a household had rejoined the labor market (Contreras- gonzalez et al. 2022).

The government’s latest development planning policies mark a shift toward structural transformation through private sector growth and the creation of more and better jobs. The 10-year Perspective development Plan 2021–30 emphasizes economic growth by improving productivity and competitiveness, and promoting growth led by the private, rather than the public, sector. In line with the National Plan for Job Creation 2020–25, these reforms aim to spur the transitions necessary to create widespread opportunities for good jobs.