exploring creative crip utopias and structural barriers in the creative industry

Hi!

We are Karina and Kristin, a graphic designer and a creative social worker who wanted to create something new. We are two people who tried to find a community for disabled artsist, but couldn’t find one in The Netherlands. We met over tea at the end of 2021 and knew that we needed to get a project started, or at least try. So here it is.

Creatives with Unseen Disabilities (CUD), is a community-based project for creatives living with non-apparent disabilities, chronic illnesses or those who are neurodiverse. CUD uses ‘unseen’ to emphasise that all disabilities are visible to those who are willing to see them. The creative industry has many barriers that make it inaccessible, and many creatives don’t disclose their disability, medical issues and/or access needs due to social stigma, or lack of support.

We initiated this community as part of our creative residency at WORM, running from March–November 2022. Our whole group met monthly for 6 group sessions to connect, collaborate and discuss inaccessibilities and challenges within the creative industry. Together with various guest speakers, the sessions focused on topics such as disability language and pride; how to balance self-care and work; and how disability can shape our creative practices.

CUD is a space for people to contribute in whatever way they are able to and feel comfortable with. Each person has their unique background and story, which forms how, and to what extent, their experiences and difficulties shape their creative practices. By sharing these experiences we built a sense of reassurance and were able to support one another. Thank you to you all who have been there and helped us along the way.

For our final exhibition, our group chose the theme ‘Creative Crip Utopia Workspace’. Come and dream with us about what an accessible art world could look like, as we launch this zine capturing all that we have explored during the residency.

We hope you enjoy the read!

Best, Karina Dukalska and Kristin Langer

WORM Pirate Bay residency March–November 2022

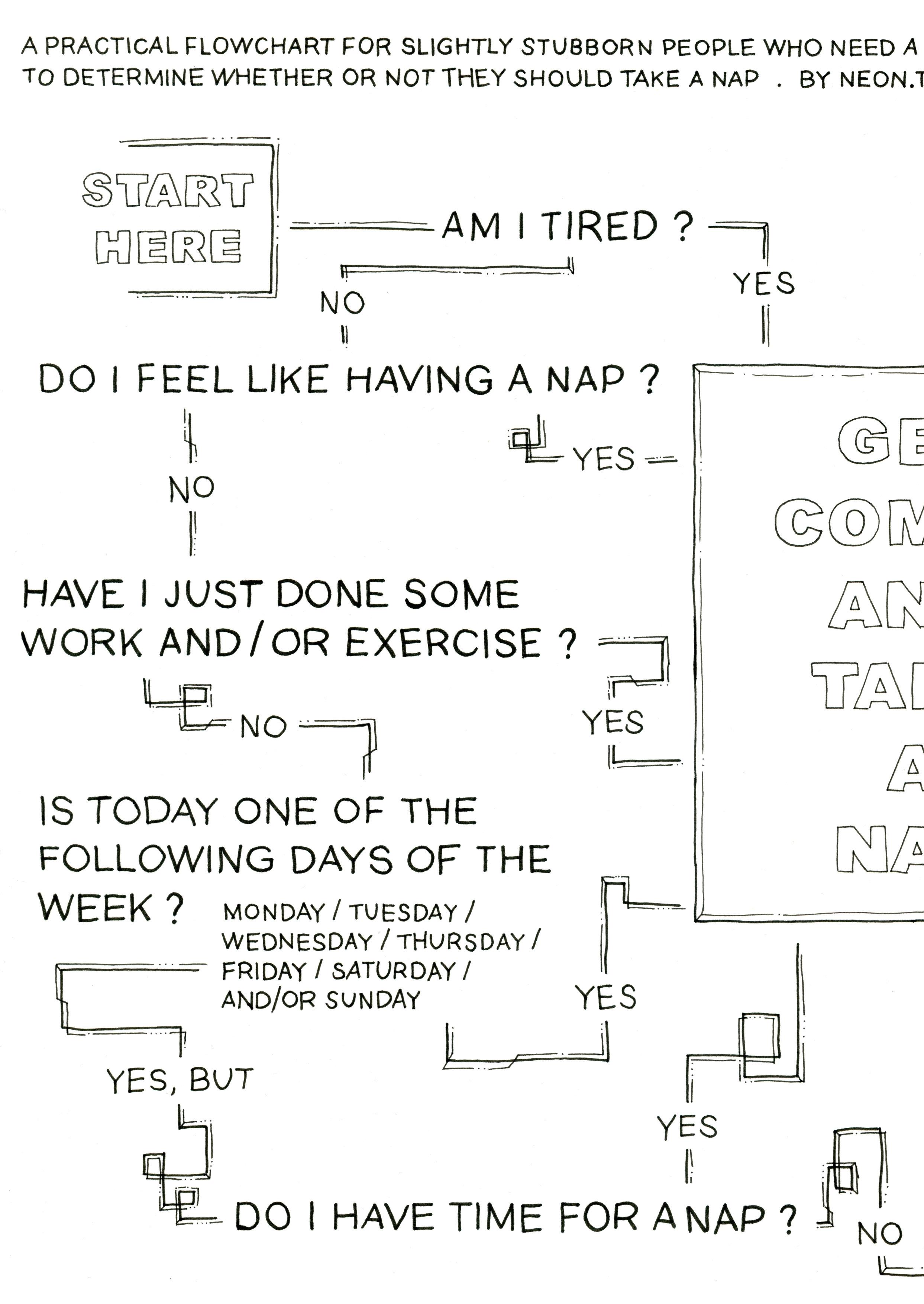

Participants: Beatrijs Rümke, Daphnis Monastirioti, Hester van Dam-Pieters, Maartje Reggin, Nicole Sciarone, NEON . TINK, Noli Kat, Pier van Wijk, Sara Rosa Espi, Victor Evink

Glossary of Disability-Related Terms

Ableism

The system of discriminatory practices and beliefs that maintain and perpetuate disability oppression - Sins Invalid

Accessibility

the quality of being able to be reached or entered the quality of being easy to obtain or use the quality of being easily understood or appreciated - Cambridge Dictionary

Access Intimacy

Access intimacy is that elusive, hard to describe feeling when someone else ‘gets’ your access needs. The kind of eerie comfort that your disabled self feels with someone on a purely access level. - Mia Mingus

Access Needs

Anything a person requires in order to fully participate in their environment or community can be considered access needs. Examples of this could be wheelchair accessibility, scent-free spaces, trauma-informed spaces, financial support etc.

Body-mind

I followed the lead of many communities and spiritual traditions that recognize body and mind not as two entities but one, resisting the dualism built into white Western culture. - Eli Clare

Crip

In-group slang for people with disabilities - Sins Invalid.

Crip is bold, rebellious and unapologetic. Crip has sass and attitude. Crip is a movement that has emerged from the disability community actively rebelling against ableist attitudes, prejudice and stereotypes. - Alice Kirby

Crip Time

‘Rather than bend disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock, crip time bends the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds.’ - Alison Kafer

Disability Justice

‘A Disability Justice framework understands that all bodies are unique and essential, that all bodies have strengths and needs that must be met’. - Patty Berne.

Internalised Ableism

Ableism that is played out inside ourselves which impacts our beliefs about our own worth and capacity - Sins Invalid

‘Invisible’

Disabilities

Non-Apparent Disabilities or ‘Invisible’ Disabilities. Impairments that are not obvious or visible. Could range from food allergies to autoimmune conditions to chronic pain to mental health conditions - Sins Invalid

Medical model of disability

Medical models of disability locate the source of the ‘problem’ as the individual disabled person and, in doing so, place responsibility for the situation onto the disabled person and away from society and how it is run and organised.

Neurodivergent

Neurodivergent, a term originally coined by neurodiversity activist Kassiane Asasumasu, means having a mind that functions in ways that diverge significantly from the dominant societal standards of ‘normal.’ - Stimpunks

Neurodivergent refers to neurologically divergent from typical. That’s ALL. I am multiply neurodivergent: I’m Autistic, epileptic, have PTSD, have cluster headaches, have a chiari malformation. Neurodivergent just means a brain that diverges. Autistic people. ADHD people. People with learning disabilities. Epileptic people. People with mental illnesses. People with MS or Parkinsons or apraxia or cerebral palsy or dyspraxia or no specific diagnosis but wonky lateralization or something. That is all it means. It is not another damn tool of exclusion. It is specifically a tool of inclusion. - Kassiane Asasumasu

Social model of disability

The social model of disability holds that people are ‘disabled’ by the barriers operating in society that exclude and discriminate against them. - Inclusion London

Will Billany

Our first Creatives with Unseen Disabilities left us in awe. Guest speaker Will Billany discussed disability justice, language and pride, and shared their own experiences of building community with other crip people. During our first session, the participants in the residency came together for the first time, and created an atmosphere of communal love, compassion, energy and instant comfort.

“Hi, my name is Will, I’m 23 and my pronouns are they/them.

I am a disabled creative, starting out in the industry. 2022 marks my 5th first year at an arts universitynavigating inaccessible and disabling institutions -my journey has shown me, we are not the problem.”

Session

23rd April

#1

2022

During the workshop Will asked us:

What do you have in common?

How would you visually represent disability pride?

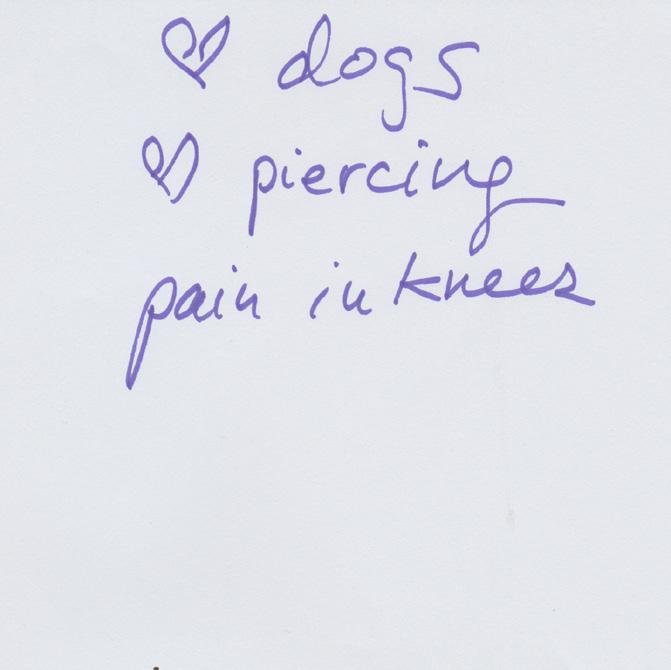

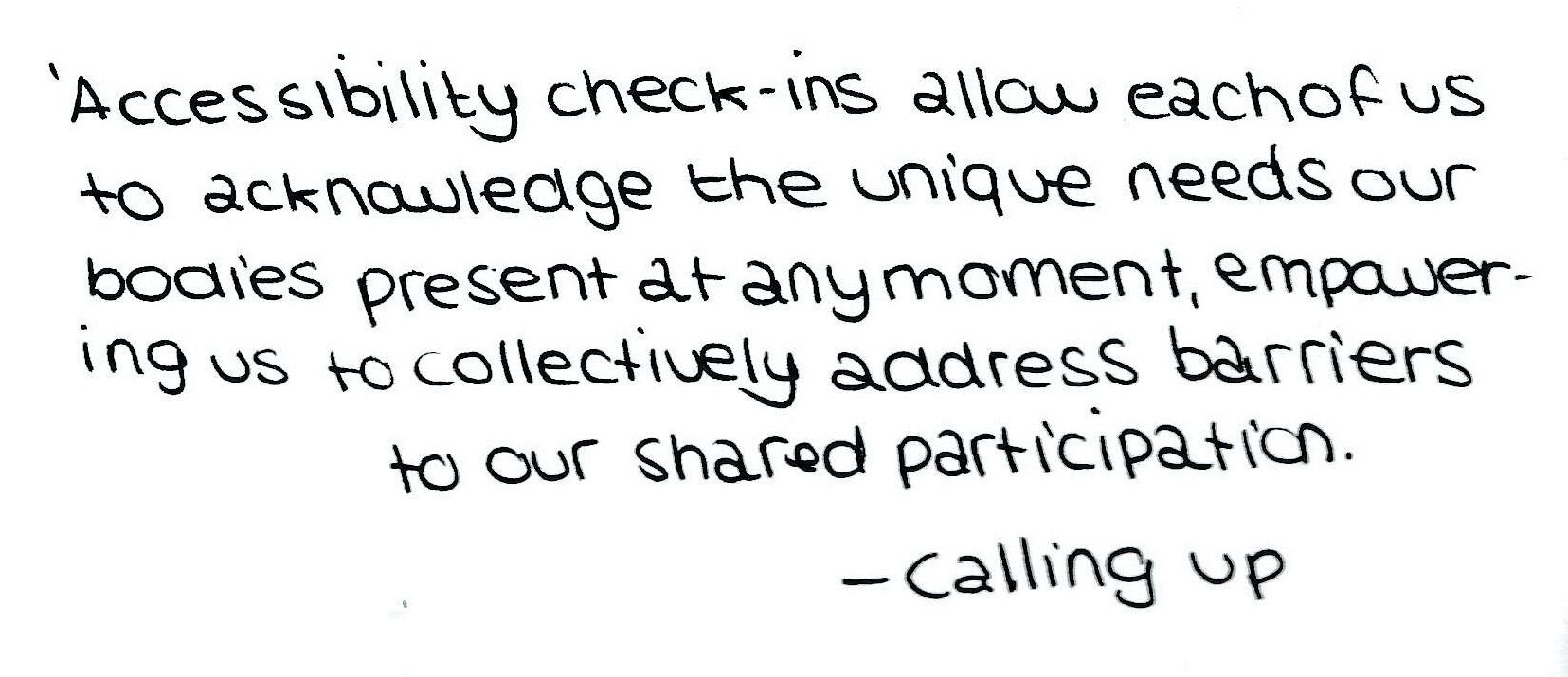

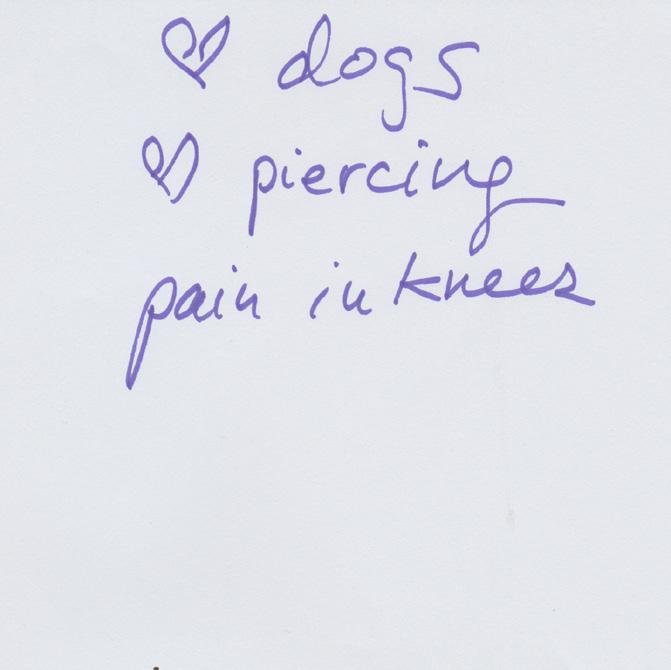

What do you need to be present in this space today? CUD and Access Check-Ins

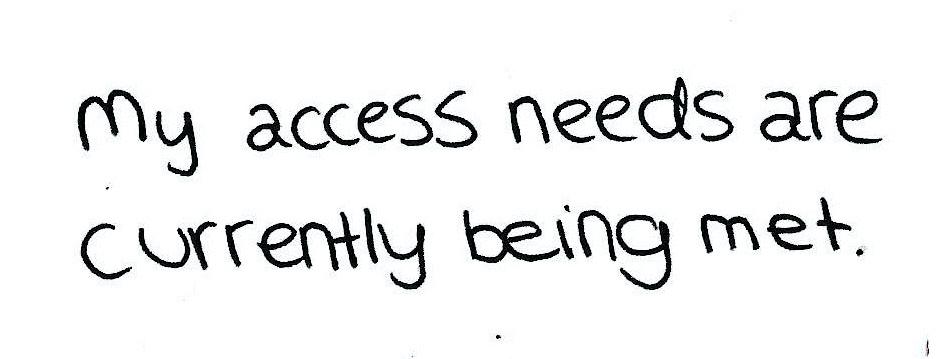

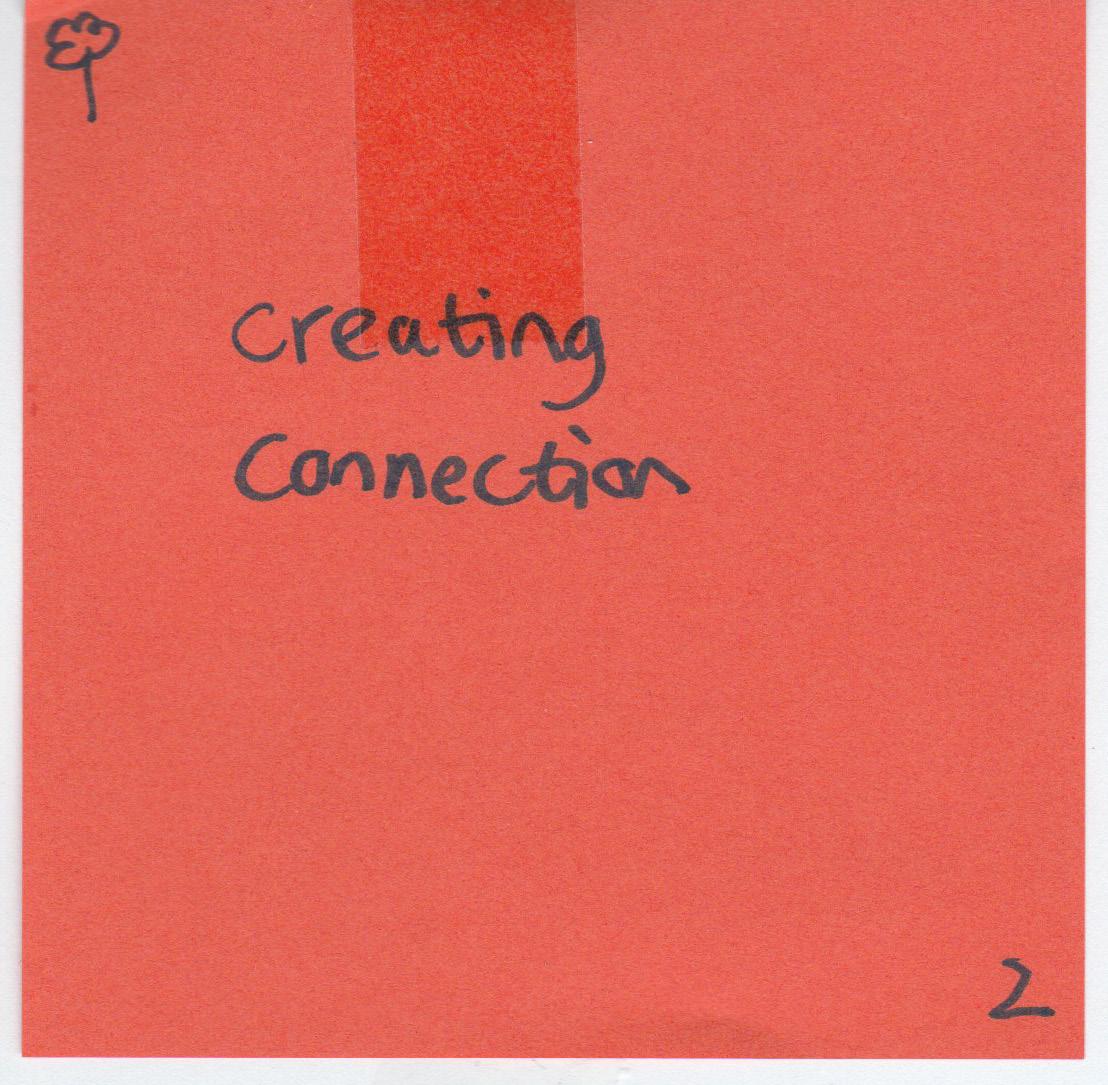

From session #2 onwards we started every meeting with an access check-in. It’s a bit like asking before you start: hey, what do you need to fully participate in this session? How are you doing today? What can we collectively as a group do to make you feel able to be present for this? We sit in a circle and listen to everyone share and then we try to work out how to support them. People can choose to participate and what they want to disclose.

Usually when we walk into a lecture/meeting etc we are just expected to show up and take in information and perform as is expected by the dominant norms of the space irrelevant of the particular needs of our bodyminds or what might be emotionally present for us that day. This can lead to us feeling uncomfortable, unable to actually be present and even dehumanized or ashamed.

Access check-ins are a practice that come from Disability Justice which is a framework that originated in the US when in 2005 a group of disabled people of colour mostly queer woman such as Patricia Berne, Mia Mingus, Stacey Milbern and others came together as a response to the fact that the Disability Rights movement in the US had largely centred the experience of white, heteronormative, upper class people. A big part of putting Disability Justice into practice is creating liberated zones where disabled people feel like they can show up as their whole selves: spaces where they don’t have to hide their disabilities or perform according to the able-bodied, neurotypical norm in order to belong.

To me, access check-ins are a way of reminding ourselves that we are humans with needs and to prioritize care for each other over the demands of the structure. The structure of the session has to adapt to what we need rather than the other way around. It is not just a practice for disabled people. Everyone has access needs, it is just that as Patricia Berne says ‘able-bodied’ people are usually less aware of them. Disabled people openly expressing our access needs is actually a service to the world: we are modeling what it is like to reclaim your needs without shame.

My own access needs changed throughout the program. The first few sessions in order to participate I had to lie down on a mattress because otherwise I would get too exhausted. For this reason a mattress was hauled into the space and I could lie down in the center of the room which was quite the unconventional picture. I never would have dared to ask for this in a space that wasn’t disability centered, I would have just not shown up. One day when I came to the session I had just lost a relative some days before. I know that if I had not expressed this I would have spent most of the session in a state of dissociation.

Being in a mixed-ability space meant that sometimes access needs of different participants clashed and we had to find a way to try to meet them all as best as possible. An example from our group was that for instance some needed others to wear facemasks in order to be protected from Covid whilst another participant needed to see other people’s mouths when they spoke in order to be able to follow what was being said. How do you resolve this? We came to a compromise of taking off the facemask when you were speaking but wearing it otherwise. You can’t always meet everyone’s access needs perfectly, it’s a messy business but for me even just taking the interest in trying makes a huge difference in how I experience the space, whether I feel welcomed, able to be there and whether the potential for feeling a sense of belonging will arise.

I felt a big urge to share on access needs check-ins for this zine because I wish for it to be a practice that everyone does everywhere all the time. My dream is that whenever I enter a space I am always first asked how I am doing and what I need. May our attempts at the CUD residency inspire you to try it out as well!

By Noli Kat @myfragileself

Maartje Reggin

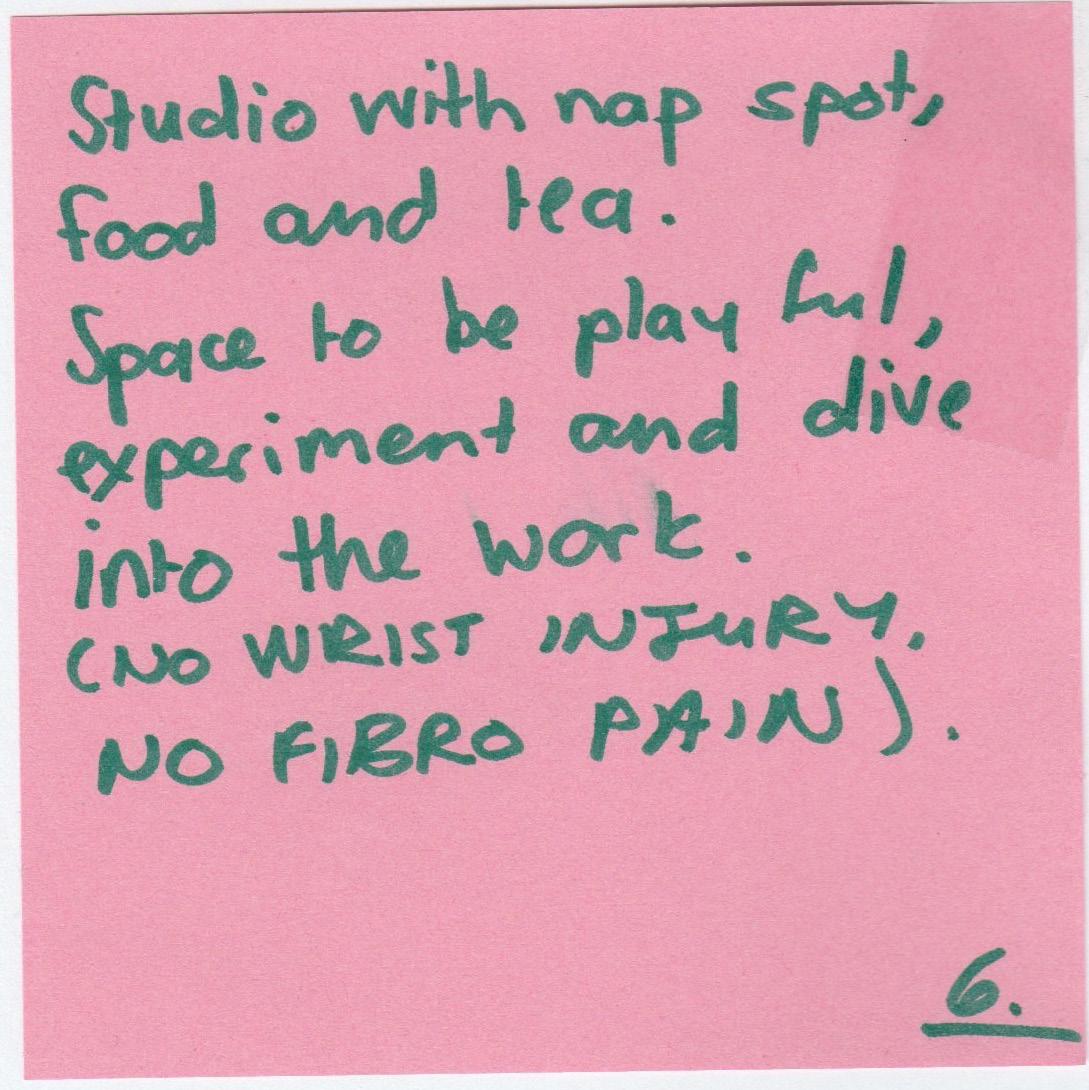

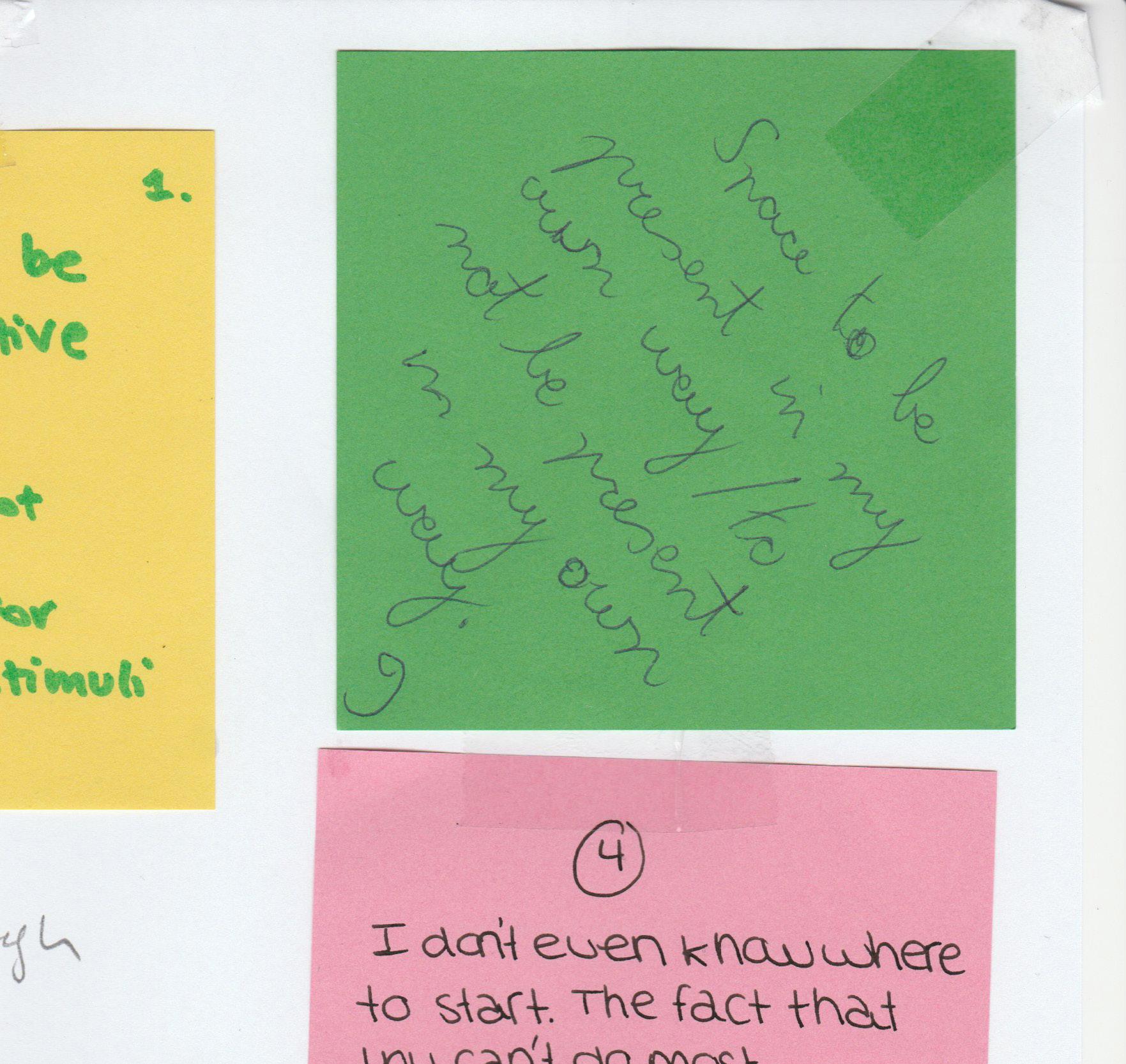

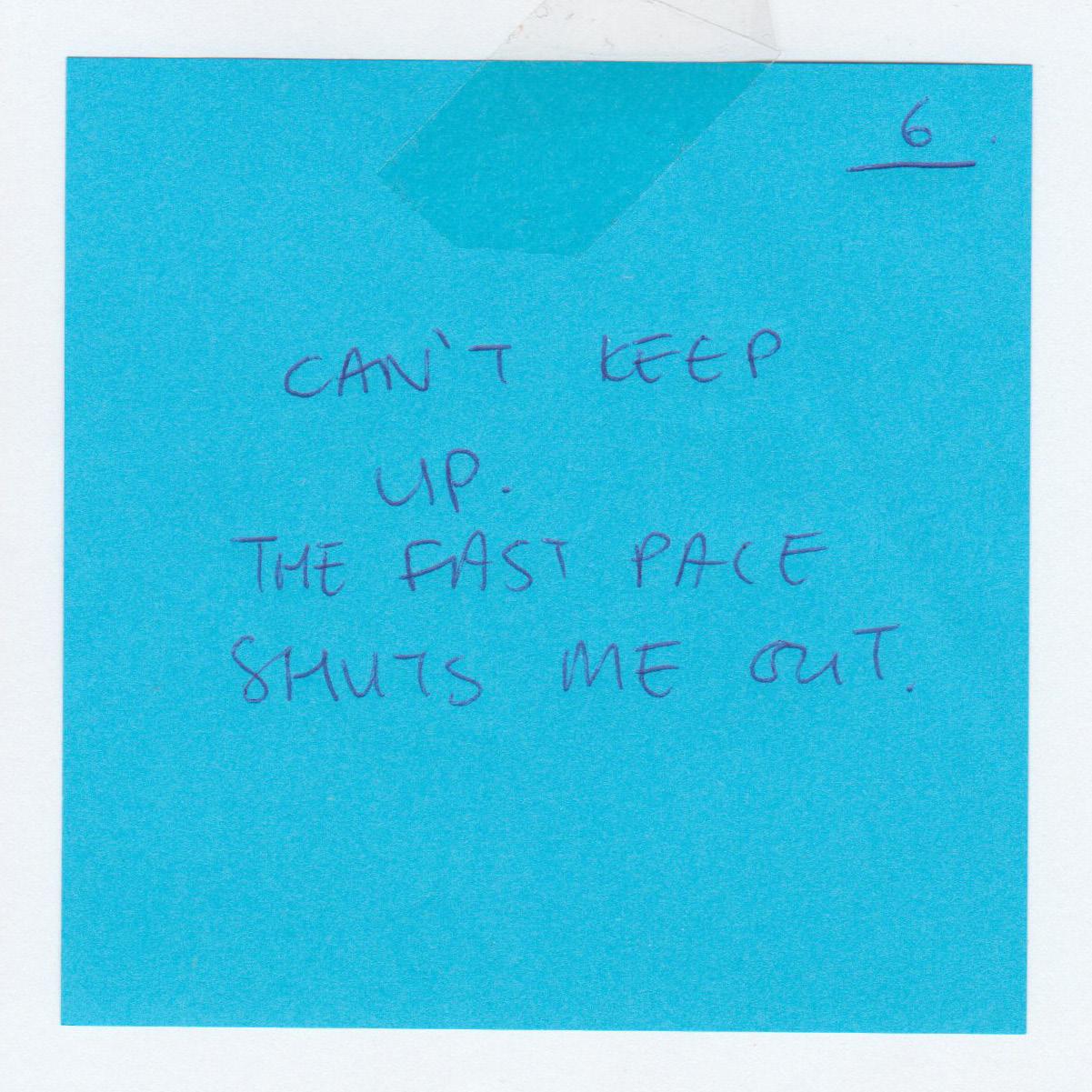

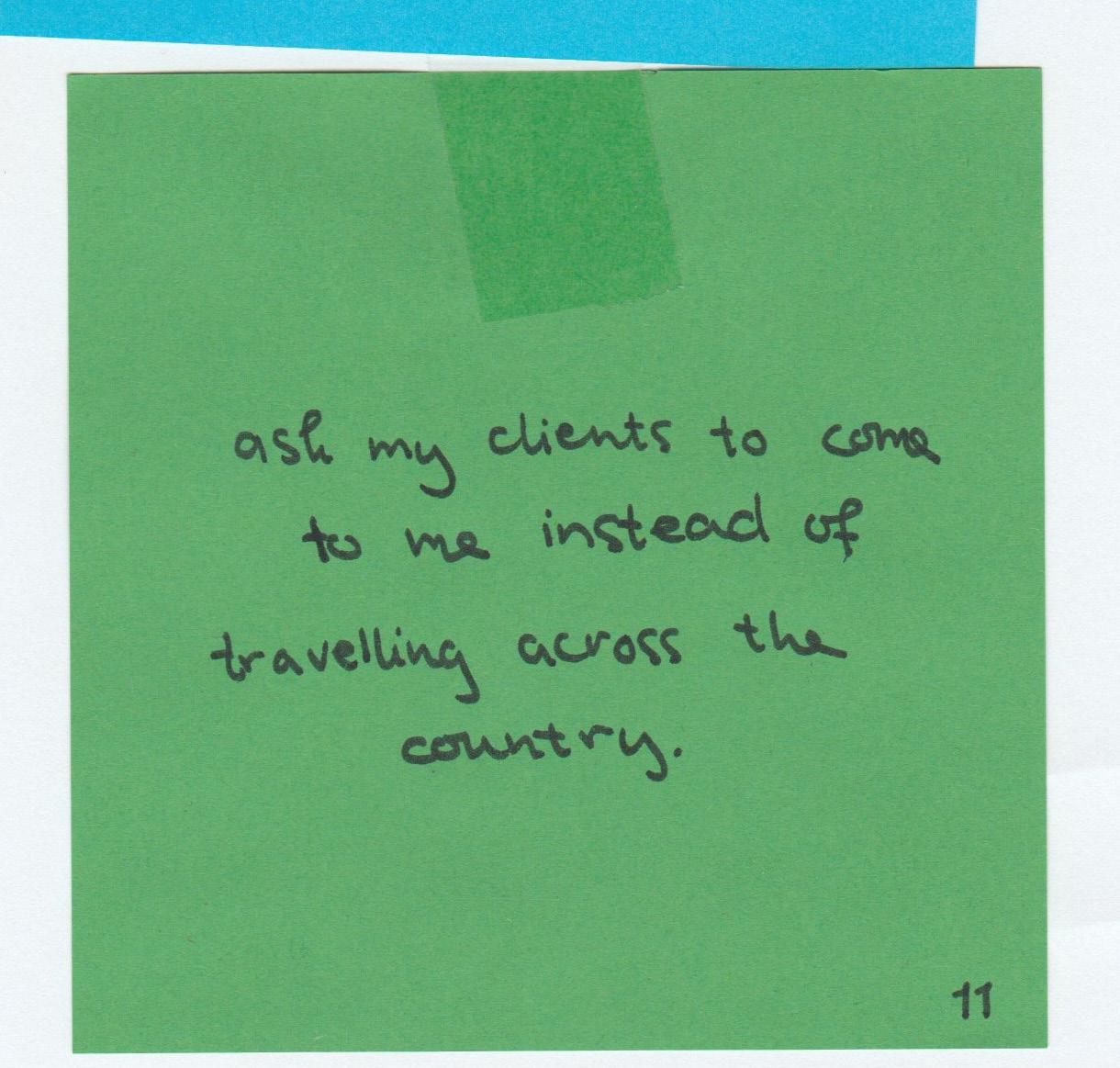

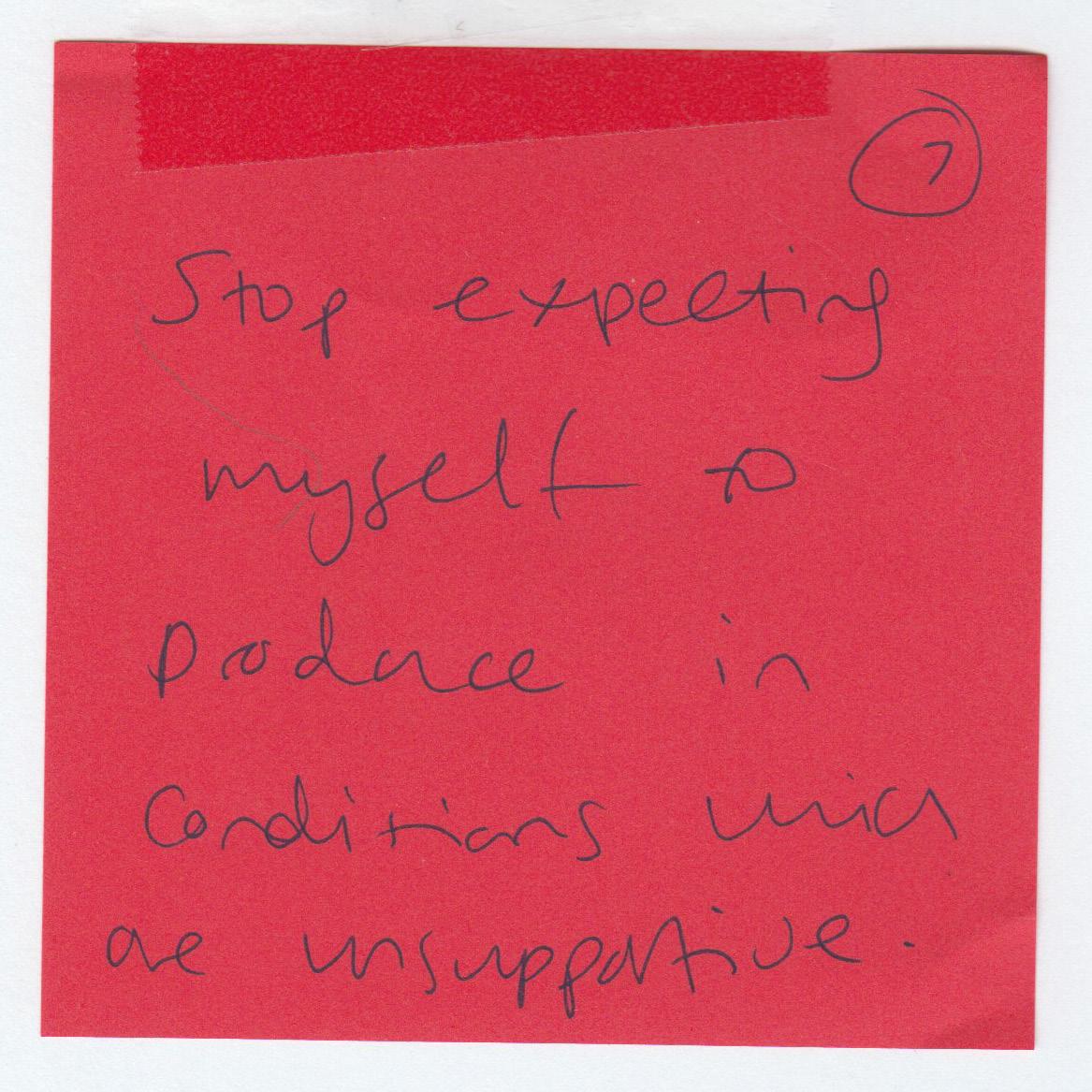

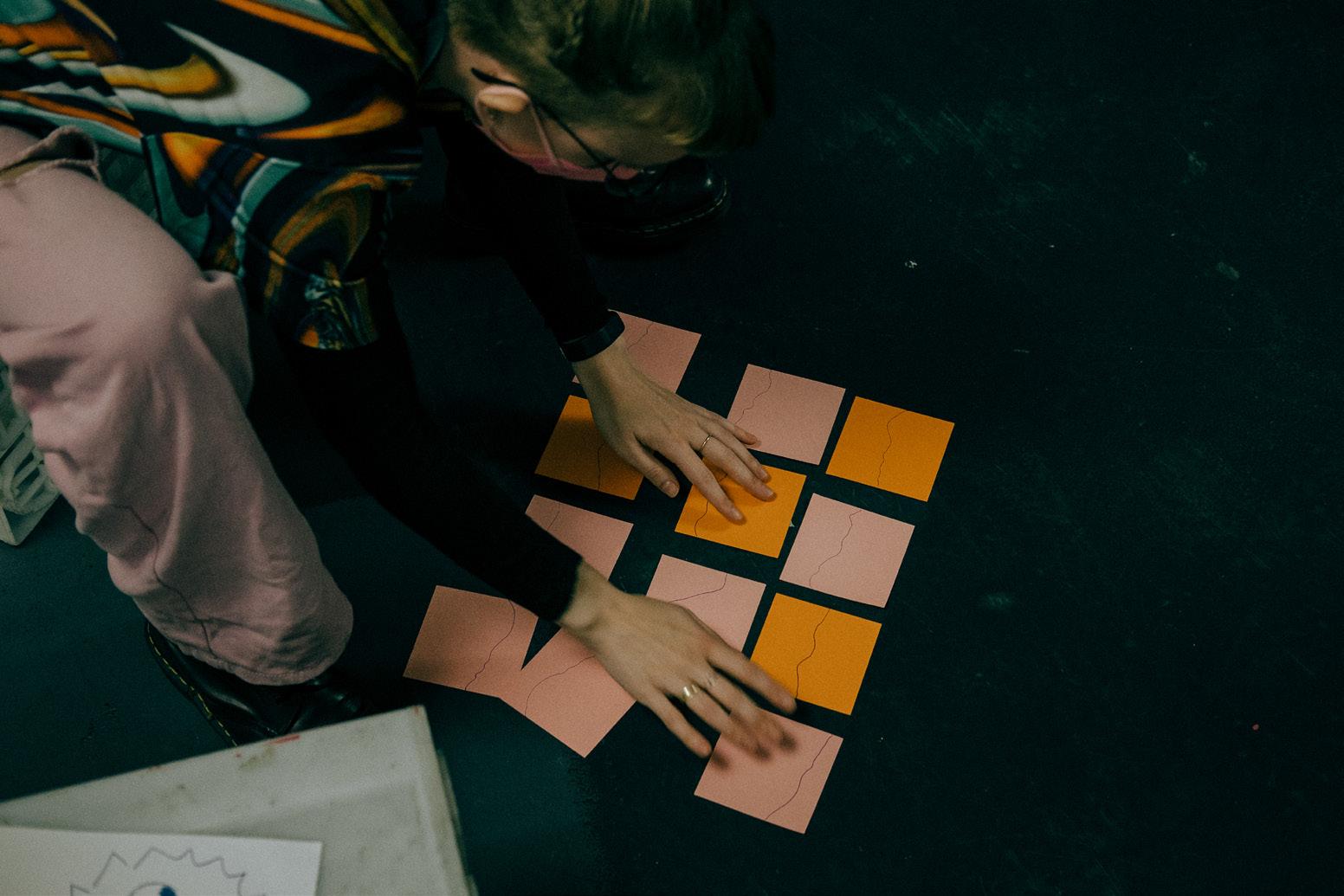

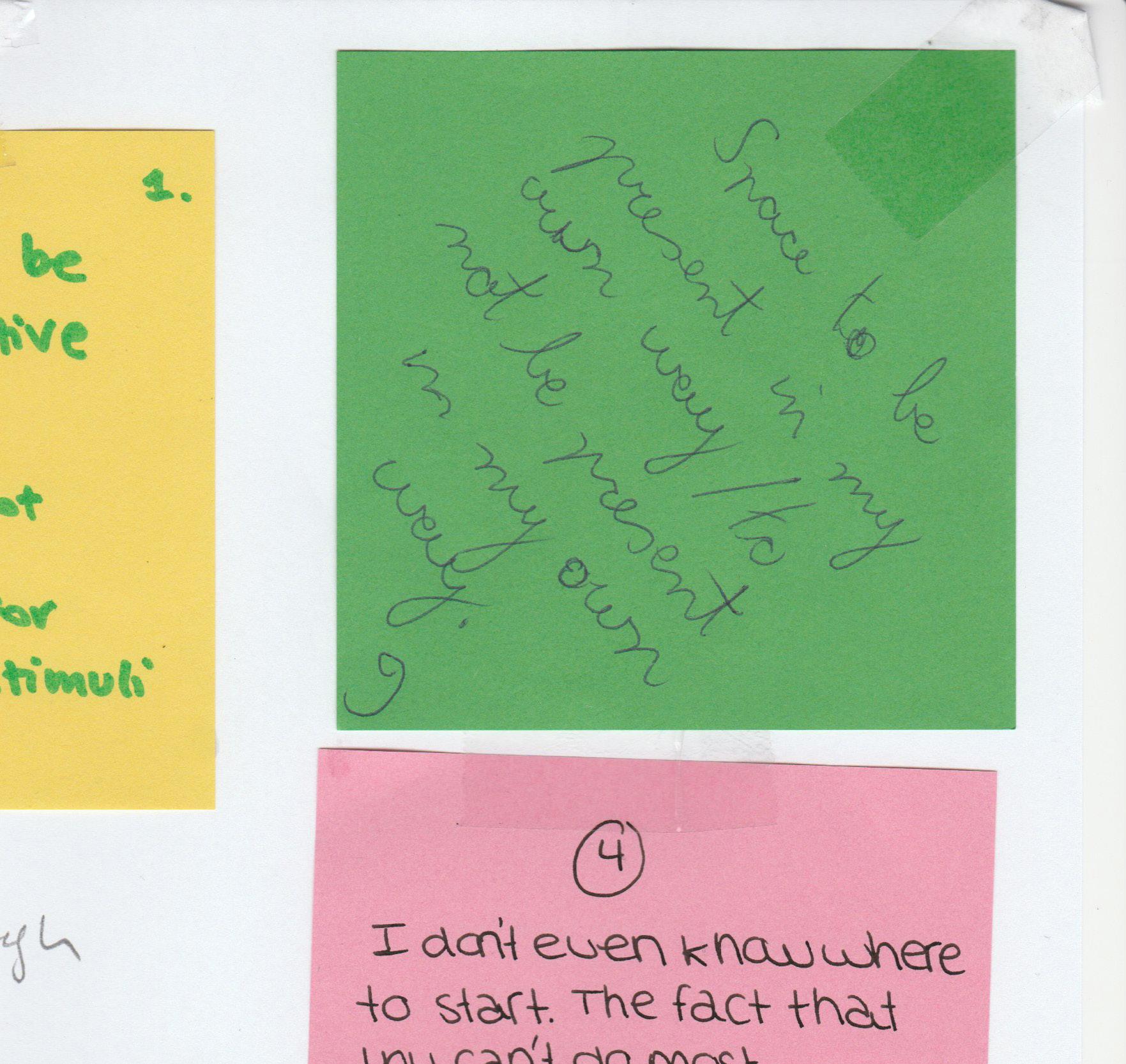

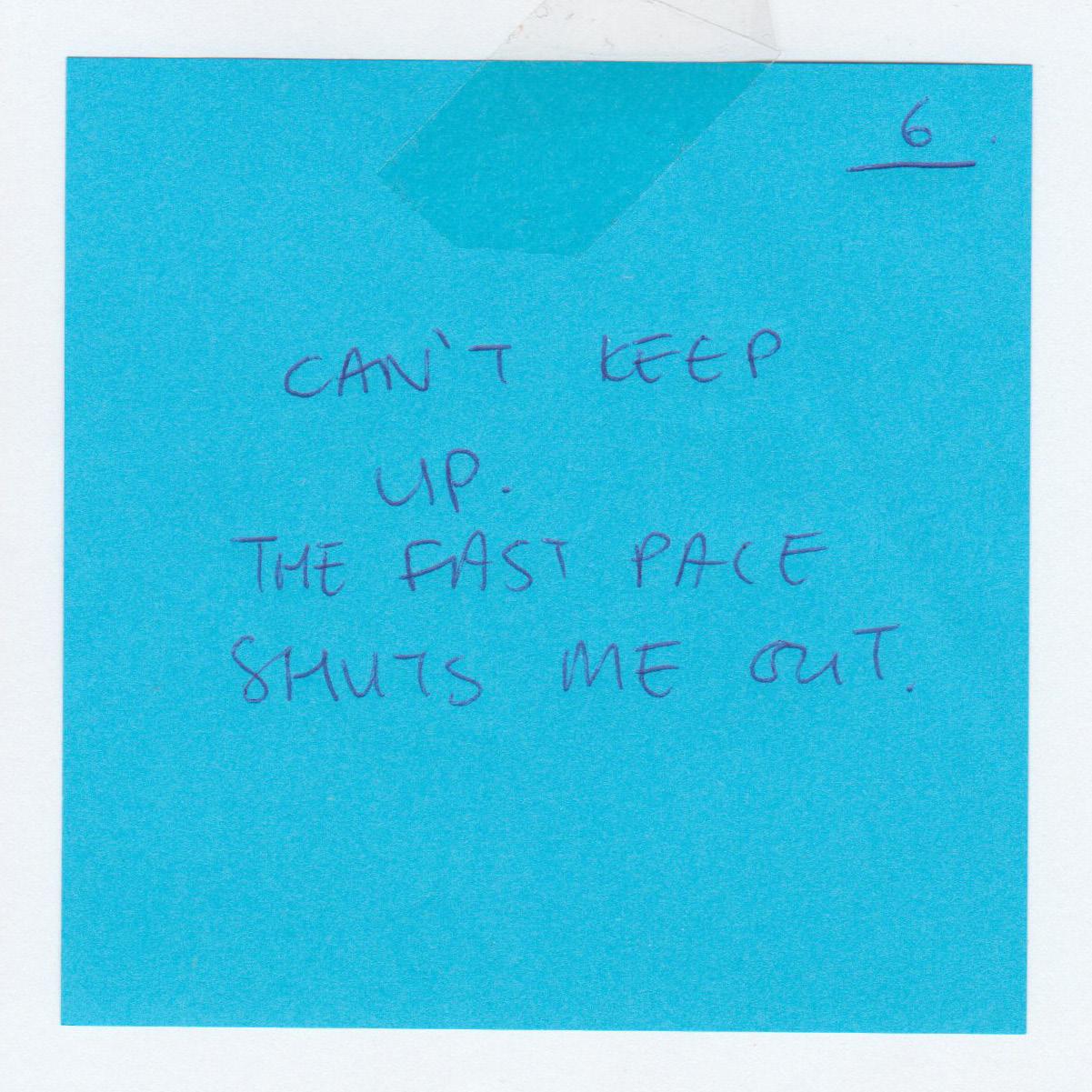

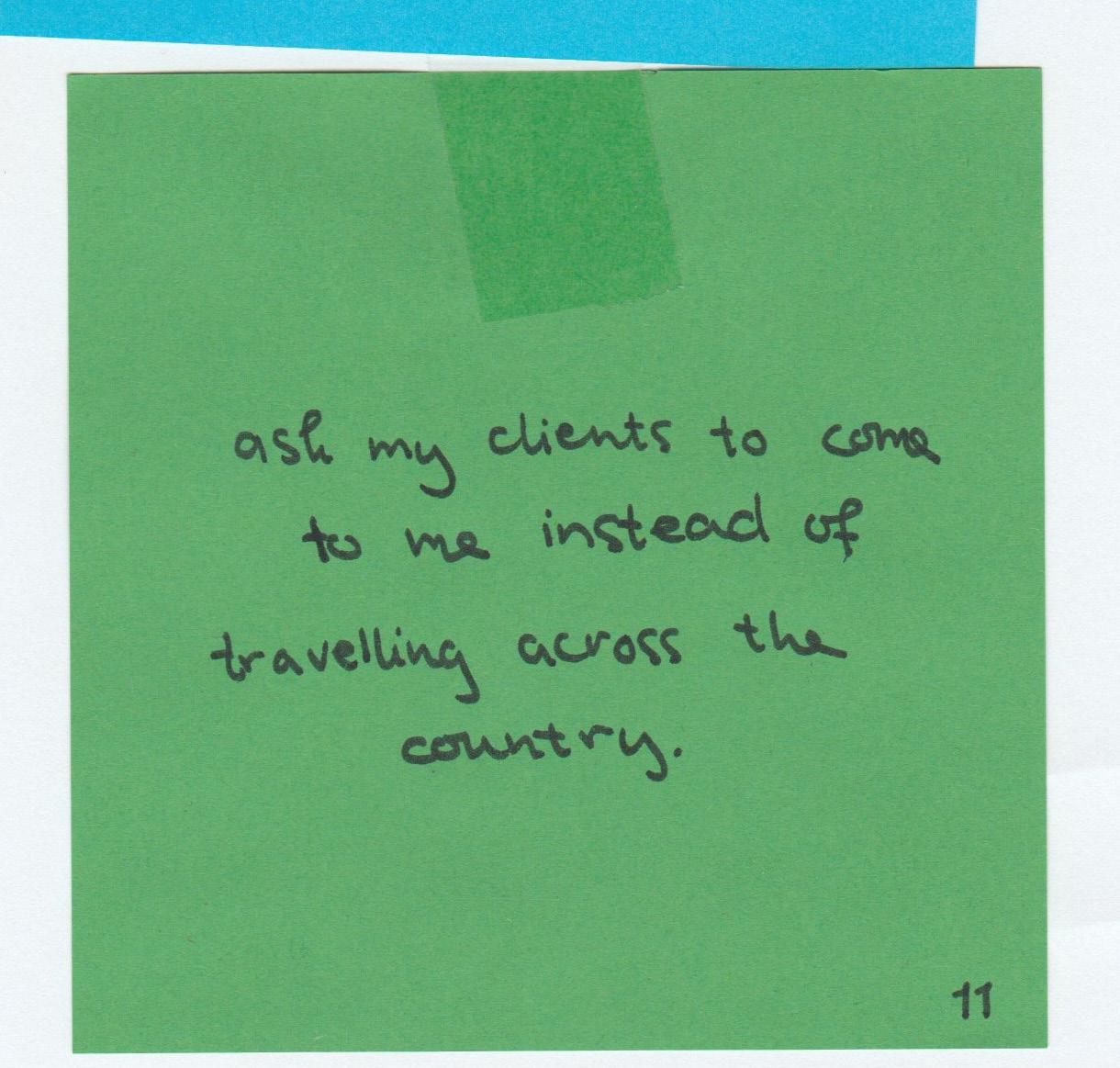

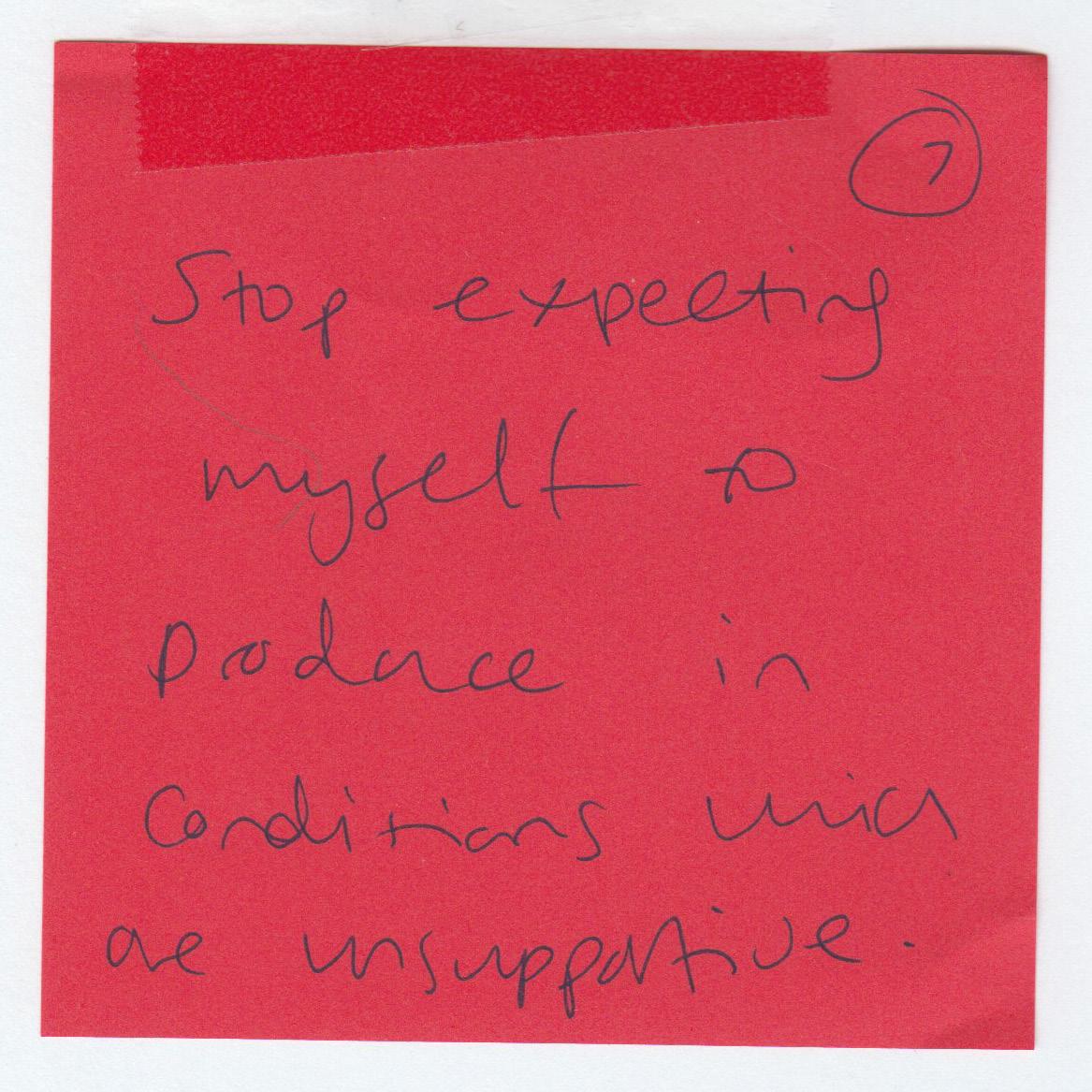

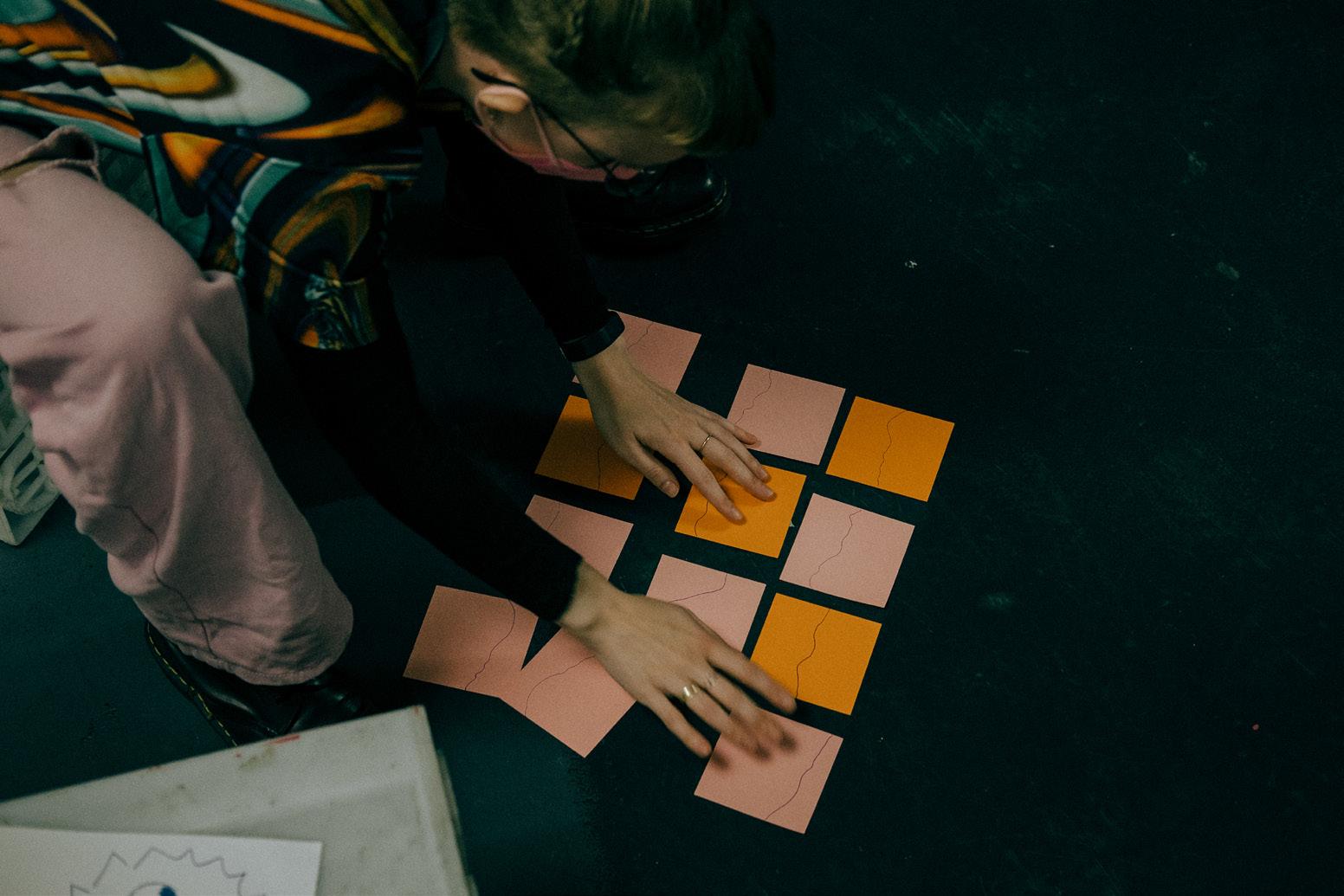

Our second session was an immersive, interactive workshop titled “The utopia of your creative practice”, and led by expert facilitator Maartje Reggin. Together, we set out on an adventure into the land of our own creative practices; we skipped through the meadows of our creative joys and visited the valleys of what we (might have) lost. Lastly, Maartje posed the question: “How can we as a community support each other through the highs and lows?” All participants shared enthusiastically, creating vivid collages of Post-its in response to each question. The workshop allowed us to reflect; to mourn; and to dream about what other worlds are possible.

Maartje (she/her) is full time disabled and hustles on the side. Her side hustles include working as a museum tour guide and disability justice activist. She’s also a dedicated pet mom to her two bunnies and cat. In her creative work she is motivated by a fascination for identity and love to connect unseen wires between visual elements

Session

14th

#2

May 2022

tallest tree in the forest what is a unique ability I have that my peers don’t have?

skipping through the meadows in an ideal world and with a limitless bodymind, what would my practice look like?

floating though the sky like an eagle in what way is the creative world inaccessible to me?

climbing a mountain

how can I adapt my practice to my abilities?

Katharina Bauer and Maren Wehrle

For our third session, we dived head-first into the deep philosophical question of “what does it mean to be ‘normal’? Philosophers Katharina Bauer and Maren Wehrle prepared a workshop titled: “Just normal? Why normality needs diversity”. During the workshop, they started a Socratic discussion on normality. Participants had space to develop specific questions, thoughts, and ideas on these issues, and to explore together how we can expand and diversify our standards of normality in the creative industries.

Maren wants to introduce herself with the brief words her good friend and colleague once wrote about her:

“Maren Wehrle is a wonderful philosopher from the Black Forest who now works at the Erasmus University in Rotterdam, Netherlands. She likes to dance, to listen to music, and to run. She works on normality, attention and the body.”

Session

18th

#3

June 2022

And here is what Katharina has to say about herself:

“It took me a while until I was ready to say: “I’m a philosopher” and not just “I have studied philosophy (in Bochum, Germany)” “I do some research in ethics” or “I work at a philosophy department (currently at the Erasmus University in Rotterdam)”. I am a philosopher: always longing for new insights, for new perspectives, exchanging thoughts, asking annoying and hardly answerable questions - a ‘lover of wisdom’ . What else do I love? My three boys (one husband, and two children), our garden, poetry, music, good food, good wine, good friends, and the sea…”

The Ladder

In the book Your Brain’s Not Broken, author Tamara Rosier tries to gives people with ADHD a guidebook to their own brains, outlining the enormous possibilities - and equally enormous difficulties - of having a brain that works differently. Rosier suggests that we all have an “emotional voice” in our heads. For neurotypical people, that voice is like a professional personal assistant, calmly issuing instructions about transitioning from one task to the next. For people with ADHD, that assistant is more irate, screaming loud hate-filled tirades and issuing guilt trips to jolt us into action because we feel frustrated and out of control. Through using the metaphor of a ladder, Rosier shows how we can tune into our own emotional states, and get a grasp of how reactive and stressed we’re feeling in that moment. If we’re in “survival mode”, our lateral thinking capacities shut down, our breathing quickens, and we become brittle and stressed — on the look out for threats. If we’re present and calm, on the other hand, we’ll be much more flexible — able to analyse a situation without taking it personally, and make thoughtful choices. The screaming voice will also become much calmer in that state. Identifying these states allows us to tune into how we feel, and advocate for what we need in that moment.

By Sara Rosa Espi

Yamini Cinamon Nair

For our fourth session, we were lucky to have a guest lecture by Yamini Cinamon Nair, who Zoomed in for an online session from London. Yamini shared her experiences of living with EhlersDanlos Syndrome and learning to thrive with chronic pain. Her workshop was practically-oriented, featuring solo and group exercises to discuss the social model of disability and how to create reasonable adjustments over time. It ended with an inspiring group discussion about small yet tangible solutions we can develop to start to thrive in a disabling world.

Yamini, works in the London Mayor’s Private Office in the Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Working Group. She was diagnosed with hypermobility Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (hEDS) in 2018 after spending much of her childhood suffering from seemingly unexplained and uncorrelated pains and injuries. She has since mentored disabled students at the LSE, working with them to devise reasonable adjustment plans to implement in the academic and professional workspace.

Session #4 16th July 2022

An access rider is a document that outlines a persons disability or access needs to let people they work with know how to ensure they have equal access to work.

Thank you for inviting me to be here today. I am so glad to be here. I would like to outline some access needs I have. I would love for us to together find ways for me to participate in this day in a way that supports my well-being. Here are some suggestions I have.

REST

Because I have ME/CFS my energy capacities are different from others in my age category.

In terms of taking care of myself I find it supportive when there is space and opportunity for me to rest during the day and to be communicated ahead of time when this this will be possible so I can plan accordingly.

FOOD

Because of various conditions I have very specific dietary requirements and I also need to eat at a slow pace and go for a walk after eating to support my digestive system. For these reasons it helps me to know when I need to be available and when I can take a break so I can schedule my lunch routine around this.

COVID

Because of my chronic illness exposure to COVID could potentially harm my recovery process. For this reason I try to keep distance with people that I am interacting with and preferably would ask them to either take a self-test or wear a mask to ensure my safety if we have to interact for longer periods of time indoors. If I have to be in a room for a longer period of time I prefer that it is well-ventilated.

ONGOING ENGAGEMENT WITH ACCESS NEEDS ON THE DAY

As my condition fluctuates what I might need in order to be well might change. I might feel perfectly fine standing and chatting for hours on end, I might be more tired and need to sit down a bit more. I would love an ongoing conversation about this.

If on the basis of reading this you have any questions feel free to approach me.

Noli Kat @myfragileself

CARE TASKS ARE MORALLY NEUTRAL

“CARE TASKS ARE MORALLY NEUTRAL”. That phrase flashed up in big block letters during the TED talk by KC Davis, titled “How to do laundry when you’re depressed.” Davis is a parent with ADHD who has worked in mental health for years. While in lockdown with two small kids, daily tasks like cleaning and showering and yes - doing laundry - completely started to overwhelm her. She became very depressed, and would lie awake at night feeling like a complete and utter failure as a mother, and partner, and person.

Until she realised that her worth shouldn’t be tied to how well she does laundry, that in fact other people’s perfectionism and ideas of how things “should be” was getting in the way of her giving herself the care she really needed. That if she could somehow free herself from the ancient moral messages about what it means to be “clean” and “tidy” she could understand that her value is completely separate from her function. That she develop a way of doing care tasks that actually worked for her, at her level of capability.

Ableism seeps into every aspect of our lives. Access isn’t only about asking for a ramp. It’s about detangling the poisonous messages about what it means to be productive, what it means to be a contributing member of society. It means having the courage to shun other people’s ideas about what our practices should look like, whether that’s in how we build homes or make families or create art.

KC Davis dealt with her isolation and despair by posting videos to TikTok. She posted clip after clip of her messy house, even when she could hardly walk from room to room because of all the clutter. She got some hateful comments, yes. But she got many more stories. Thousands of people wrote to their own feelings of overwhelm and despair and relief at hearing they weren’t alone. The best kind of change happens by creating communities like these.

Communities that think, together, about what it means to be disabled, and how we can shape the world to fit us, rather than the other way around. Like this Creative Crip Utopia, where we reject the need to be “upstanding citizens” and examine what happens if we embrace the horizontal. Together.

By Sara Rosa Espi

by Sara Rosa Espi

by Sara Rosa Espi

Frederike Manders

Our fifth session featured an interactive workshop by visual artist and VR expert, Frederike Manders. During the workshop, Frederike shared her experiences and challenges and discussed what moved her to express herself in photography and VR. How is life living with epilepsy? Is it possible to experience the impact of this unnoticeable neurological disorder? And how would you visualize your perspective of the world? These are all the questions that we delved into during the session. It ended with an exercise where each participant created visual responses to the following questions: “How would you visualise the perspective of your world to your loved ones? How would you represent your most difficult or vulnerable parts of you?”

Session #5 17th September 2022

Frederike is a visual artist, VRexpert and Founder of INTERU_PSY, a VR project to build awareness and understanding of epilepsy. Worldwide, at least 80 million people live with epilepsy. A neurological disorder that is unnoticeable for people most of the time and difficult to explain to your environment. The impact of epilepsy on daily life is hard to measure. As an artist she used her own experiences of living with epilepsy to create a virtual reality to let people without epilepsy experience what this impact is.

photos by Hester van Dam-Pieters

photos by Hester van Dam-Pieters

photo by Hester van Dam-Pieters

photo by Hester van Dam-Pieters

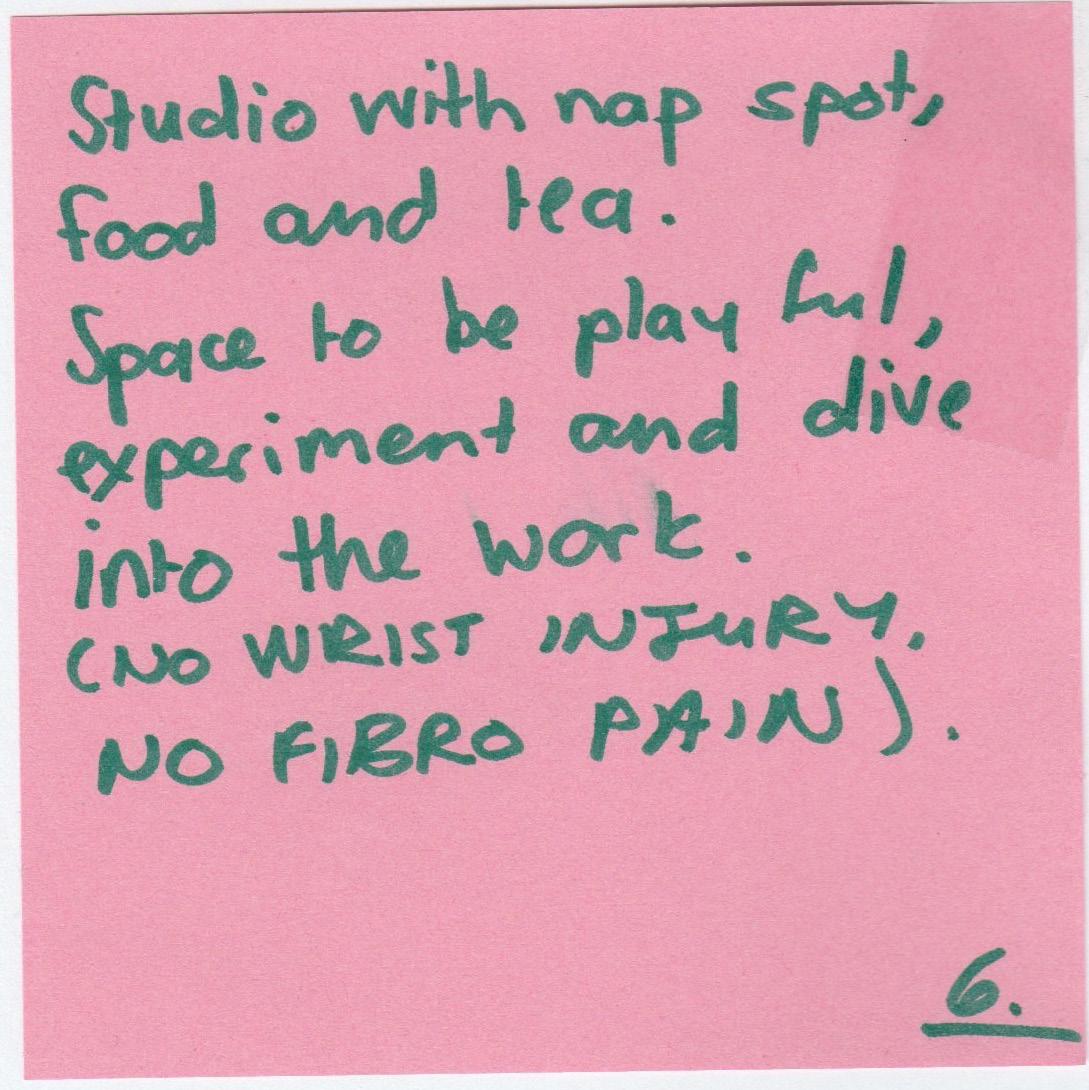

Rebellious Acts Responsibly

In 2018 I lost the ability to use my hands. A severe burnout in conjunction with a previous Repetitive Strain Injury (RSI) led to fibromyalgia. As an artist, this was devastating. It meant that I was unable to perform basic daily tasks; from getting dressed to bathing and cooking.

This combination also meant my body was unable to heal the injuries properly in the expected 9 months.

Instead, it’s taken 4 years and counting. For those 4 years, I had to wear medical braces everyday. I had to do physiotherapy 3 times a day everyday. It was a harsh reminder of what I was unable to do.

So the question arises: what happens when you are unable to do something, and moreover, what happens when you are told you can’t do something you love? You want to defy the odds and do it so much more, but the reality is that it could have severe consequences.

So I did what I do best: get creative.

I turned my healing into a simple act of defiance by doing exactly that which I was not meant to do. I created a series of hand studies with braces, but rebelliously used embroidery in combination with painting.

Contradictory, using these inherently repetitive tasks, albeit much slower, I avoided injury. This made me appreciate the slower approach to life. My methodology as an artist had to change to accommodate fibromyalgia and repetitive use of my hands. But the new limitations my body imposed on me, instead of dragging me down, helped me to grow, adapt, and in a way, become more successful than ever.

In essence my work symbolizes rebelliousness, criticizes grind culture, and imposes inquiry into (inner) ableism; the act of creating something despite setbacks and obstacles, albeit through alternative working methods, has become an example of the fact that I now (have to) find alternative ways for all things in life.

By Nicole Sciarone

RSI Series by Nicole Sciarone

by Karina Dukalska

RSI Series by Nicole Sciarone

by Karina Dukalska

Preparing for final show

Our sixth session was dedicated to planning our final show: a Creative Crip Utopia Workspace.

How could an accessible art world look like? In the space we would like:

launch this(!) zine that captures all that we have explored during the residency artworks of the participants including ‘alternative’ CVs and access riders

a bed, pillows, and textile sculptures a low-stimulation space where people can listen to some relaxing sounds or to our CUD radio show

free snacks and non-alcoholic drinks

Session #6 15th October

2022

photos by Noli Kat

Today I Swam in Flowers by Hester van Dam-Pieters

Today I Swam in Flowers by Hester van Dam-Pieters

Days by Noli Kat

Days by Noli Kat

On behalf of us all, thank you for reading!

It has been a life-changing year for us. We met and befriended the most amazing people. We learned a heap, and we hope that with the help of this small publication, you learned a little too. Thank you for reading along.

If you’d like to find out more, we can recommend:

Books

‘Disability Visibility’ by Alice Wong

‘Rolling Warrior’ by Judith Heumann

‘Crip Kinship: The Disability Justice & Art Activism of Sins Invalid’ by Shayda Kafai

Podcast

Sylvie Rosenkalt’s for BARTALK discussing disability activism and care

Documentary Crip Camp on Netflix

If you’d like to listen to some of our radio recordings, go to: https://m.mixcloud.com/wormpiratebayradio/

Read more about the beginning of the project here: http://bit.ly/3UKaof4

Read an interview with Kristin Langer and Karina Dukalska: http://bit.ly/3A642if

Follow the project on Instagram @creatives.unseen.disabilities

Would you like to connect? Or perhaps you have questions? Get in touch at hello.cud.community@gmail.com

Design: Karina Dukalska

Typefaces: Lato Regular, Lato Bold, Neue Kabel Bold

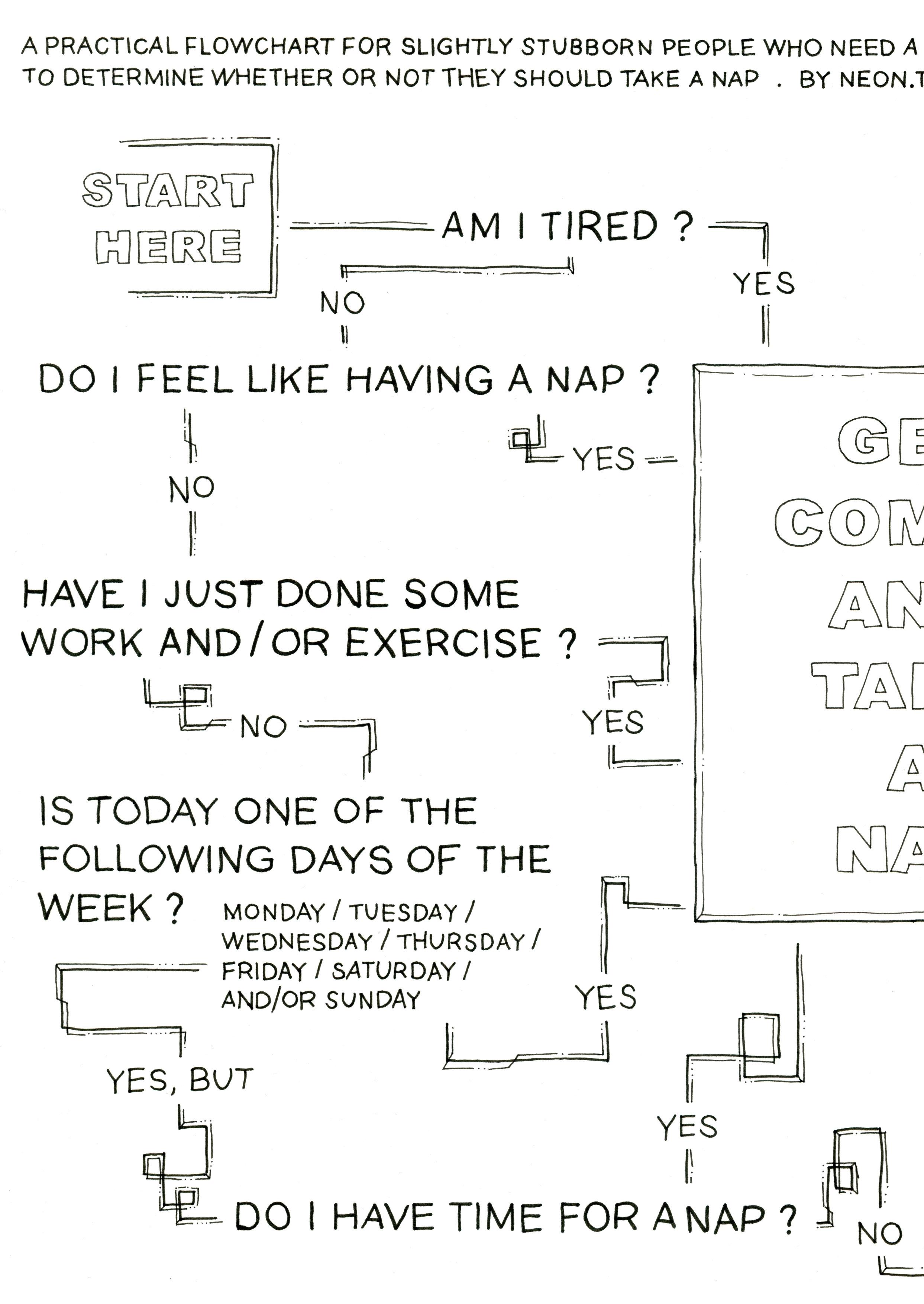

by Noli Kat and Neon.Tink

November 2022

Printed at WORM as part of the Creatives with Unseen Disabilities residency

by Sara Rosa Espi

by Sara Rosa Espi

photos by Hester van Dam-Pieters

photos by Hester van Dam-Pieters

photo by Hester van Dam-Pieters

photo by Hester van Dam-Pieters

RSI Series by Nicole Sciarone

by Karina Dukalska

RSI Series by Nicole Sciarone

by Karina Dukalska

Today I Swam in Flowers by Hester van Dam-Pieters

Today I Swam in Flowers by Hester van Dam-Pieters

Days by Noli Kat

Days by Noli Kat