TV

Sarah Patience

Kerry Jiang

Bohong Sun

Paris Chia

Yola Reinecke

Content

Aala Cheema

Holly McDonell

Sarah Greaves

Ally Pitt

Anuva Rai

Caelan Doel

Chi Chi Zhao

Cleo Robins

Hannah Bachelard

Lara Connolly

Patrick Fullilove

Remi Lynch

Rosie Bendo

Management

Sania Jamadar

Benjamin van der Niet

Madeleine Grisard

Hannah Seo

Sigourney Vallis

Alina Spitz

Art

Vera Tan

Sanle Yan

Amanda Lim

Brandon Sung

Cynthia Weng

Jocelyn Wong

Oliver Stephens

Xiaochen (Fiona) Bao

Radio

Caoimhe Grant

Cate Armstrong

Alexander An

Natasha Kie

Punit Deshwal

Lilian James

Laura Heath

Grace Williams

News

Sophie Hilton

Ruby Saulwick

Constance Tan

Madhav Kacker

Hannah Benhassine

Gisele Weishan

Dash Bennett

Beatrice Tomlinson

Joseph Mann

Front Cover by Sanle Yan

ANU Offers Cash In Bid To Fill Up Empty Residential Halls

The Winners And Losers Of Post-Study Visa Cuts ANUSA 2023 End of Year Report Reveals Increased Demands For Welfare Services Place

A Sunburnt Country For Me

News

Lost

The Call of Home The Dutch House: Houses, Homes and Hearts Can You Afford to Leave the Sharehouse Behind? In Defence of Vanilla Driving Lessons Sprout Street Berlin Is a Door Just a Door?

Finding Home in

Why Disabled Advocates Should Be at

on the Political Left Poetry 313 Lobelia Dare Waiting For a Friend Home. Untitled 5 9 11 15 18 20 22 24 26 28 29 31 34 36 38 42 44 47 50 52 55 57 58 60 62 63

Home:

On Campus

People Via Fernando Santi, 5 Love’s Labour’s Lost Labour Unveiling Love: A Family’s Symphony of Breaking Stereotypes and Embracing Diversity Diane The Biological Tapestry: Navigating the Nesting Instinct

an Unexpected Connection

Home

Contents

Earlier this year, I came across an advertisement for rooms available in ANU residential accommodations. While my time at Woroni News has made me accustomed to the University’s bizarre and unpredictable moves (see pyramid scheme, page 5), this was late January, only one week before the infamous occupancy agreement contract began, only two weeks before students arrived on campus.

In late January, most returning and new students have already bought their plane tickets to Canberra. In late January, only three weeks before the semester starts, most rooms should already be assigned. In late January, rooms should not have been available, rooms should not have been empty.

Our homes define who we are, and the homes, or rather empty rooms, at the ANU define what the University is becoming or what it already has become.

Recent data from the Department of Education has revealed that the ANU has some of the lowest rates of lower socio-economic attendance. While this information shouldn’t be surprising to anyone who has stepped foot inside any of ANU’s residential halls (even at Burton and Garran hall, where the white and the affluent hide underneath a carefully crafted veneer of the Green Shed), its confirmation should be cause for concern.

Living at the ANU and studying at the ANU are inextricably linked, perhaps more so than other universities given that a considerable number of ANU students are inter-state. Those who study at the ANU are only those who can afford to live at the ANU.

Between selling halls to hedge-funds and tokenistic financial grants, the University has actively made it more difficult to live at the ANU. Prices go up quite nefariously and irresponsibly. Demand moves elsewhere, into over-crowded share-houses, farther and farther away from the University. Affordability comes before accessibility.

While these empty rooms stand as a stern and quite possibly the first ever signal to the ANU that it cannot defy economic logic and ethical concern in its pursuit to uplift its investors-one empty room comes at too many costs.

These empty rooms, which I can only imagine at this point are dust-covered and grim, comes at the cost of one more remote or regional student, or one more Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander student or one more lower-socio economic student who couldn’t attend the ANU.

One empty room is one less home.

As I write this in week three, rooms continue to be available at ANU accommodations. This magazine, however, is filled to the brim, with your nostalgia, musings, search, anger, longing and love for homes new and homes past, and we are forever grateful they found a place at Woroni. Finally, a thanks to our Art Editor Jasmin Small, our Content Editor Claudia Hunt and their teams, our News team, and the Board of Editors, without whom Woroni would not be possible.

Thank you for never leaving Woroni empty.

2.

Raida Chowdhury, News Editor.

Letter From the Editor

3. Managing Editor Phoebe Denham (they/them) Editor-in-Chief Matthew Box (he/him) Head of Radio George Hogg (any pronouns) News Editor Raida Chowdhury (she/her) Art Editor Jasmin Small (she/her) Content Editor Claudia Hunt (she/her) Deputy Editor-in-Chief Charlie Crawford (he/him) Head of TV Arabella Ritchie (she/her)

by Jasmin Small

4.

Art

ANU Offers Cash In Bid To Fill Up Empty Residential Halls

Joseph Mann

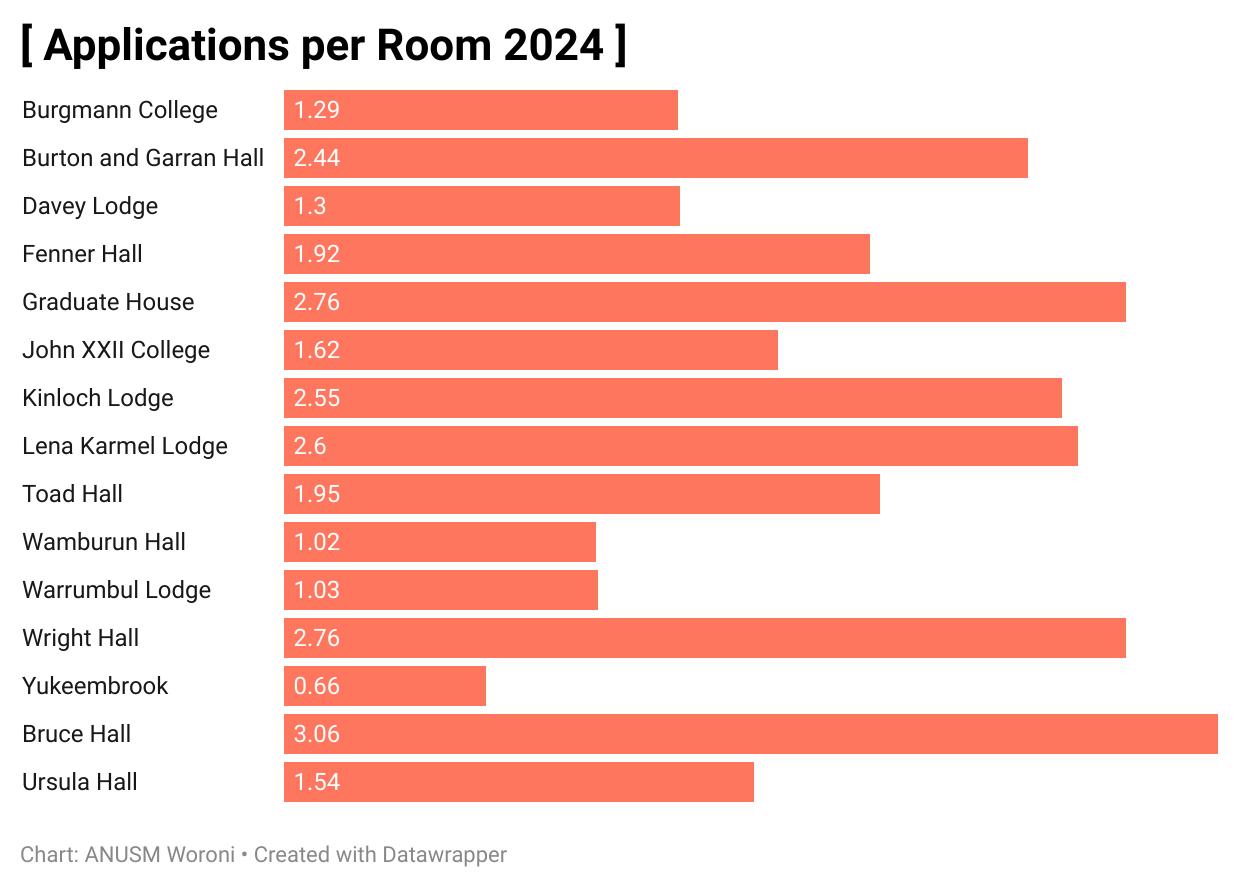

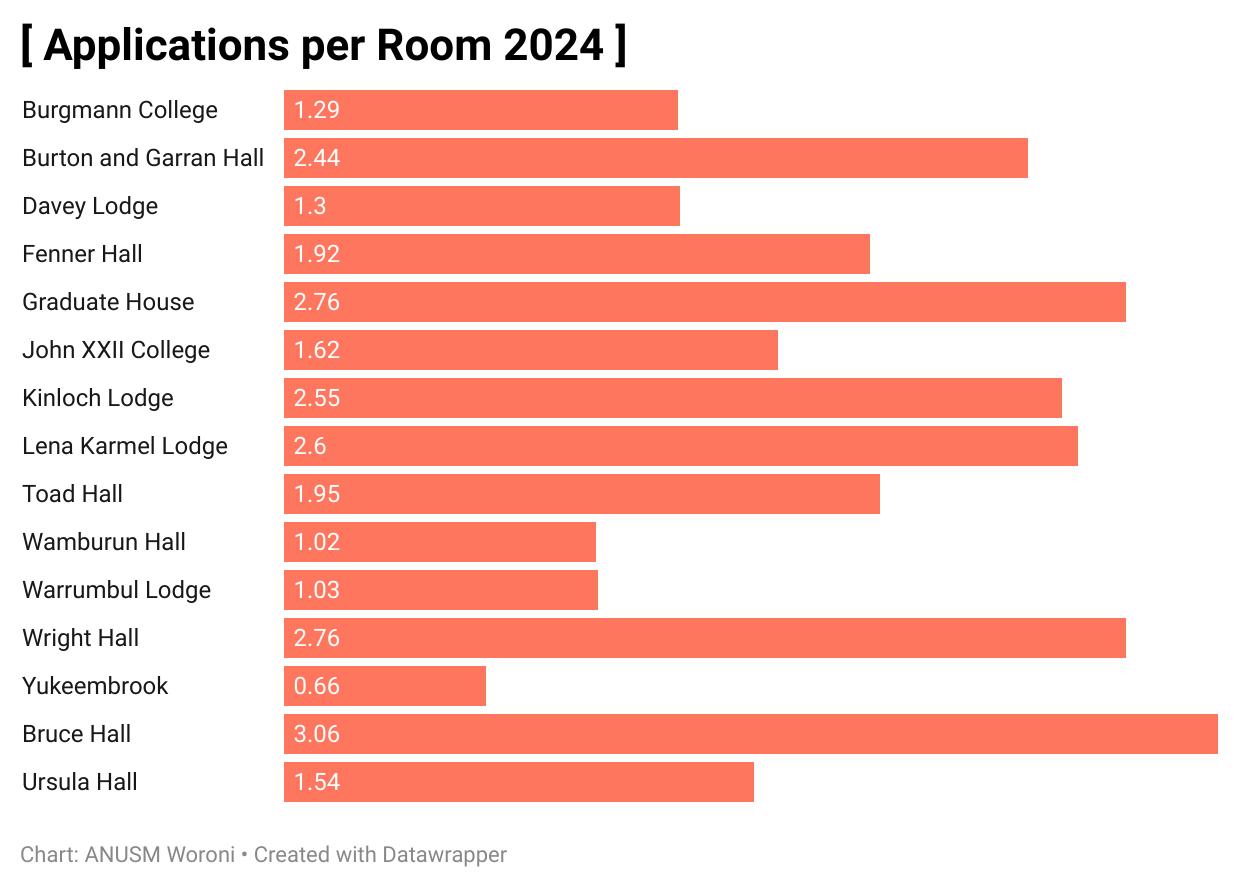

The ANU is offering up to $5,000 to students who refer others to move into the University’s residential halls, following a 4% decline in residential hall applications. Data accessed by Woroni revealed that applications for 2024 totalled at 11,912 applications, which is 500 less than last year’s total of 12,413 applications.

The big winners this year were Wamburun, where applications jumped 53% to 508 (from 332), Burton and Garran Hall where applications increased 33% to 1262 (from 948), and Fenner Hall where applications increased 30% to 868 (from 664).

The biggest losers this year were all at UniLodge including Warrumbul Lodge where applications fell 36% to 432 (from 675), Lena Karmel Lodge which fell 32% to 1452 (from 2146), and Kinloch Lodge which fell 25% to 1278 applications (from 1707).

5.

Yukeembruk had the fewest applications per room, which is concerning against the backdrop of high withdrawal rates from the hall last year, with 129 leaving or choosing not to take up residence between January and August 2023.

While 11,912 applicants would be enough to fill the total 6,400 residential units offered at the University, the ANU Accommodation website was still offering “instant” offers as of week two.

This suggests that there are still many rooms available. An ANU spokesperson confirmed, “as of the first week of semester one 2024, the majority of rooms across our campus accommodation have been filled”. It is the case that students may be declining successful offers or the University is rejecting applications.

Accepting residential offers present large upfront costs. These upfront payments include the registration fee for new students, the refundable deposit, residential committee fee, cleaning fee and two weeks of tariff payments in advance.

The refundable deposit for most standard rooms, some with shared kitchens and bathrooms, ranges between $800 to $1000. For Burton and Garran Hall, which has the lowest tariffs, the upfront costs for a new resident would be about $2087.

However, it may also be the case that students found more affordable options offcampus. Rent in Canberra’s private market stabilised for some and decreased for others as the vacancy rate in Canberra’s rental market went above 2% for the first time in a decade last year.

ANU’s residential halls are also facing competition from the new market entrants Y Suites, which opened a student residence on Moore Street with 736 units last year. In addition, competition includes UniLodge residences at the University of Canberra, which are also open to ANU students, a small number of private operators like the non-profit Student Housing Co-operative at Havelock House and the private rental market.

The ‘Refer ANU Earn’ scheme was announced in the On Campus newsletter and the Residential Experience unit’s social media pages in early February. The scheme was advertised offering $250 per student for a maximum payout of $1,000. On February 16th, the ANU announced on Instagram that it had raised its referral bonus offer to $1,000 per referral for a maximum payout of $5,000.

Under the scheme, referrers receive $1,000 for every student who accepts an offer, by signing the occupancy agreement, through following the receiver’s delegated link. The referred student will receive a credit to their rent of $1,000.

6.

It is yet to be seen whether the referral scheme will successfully fill up the halls, given that the average increase in tariff prices for a standard (non-lodge) has been an extra $20 per week, an approximately 5.04% increase from last year. Over a typical 44 week contract, this amounts to an extra $880 a year.

Rooms continue to be available as of week two of the semester.

The ANU spokesperson told Woroni that “ANU remains the only university in Australia to provide new students with guaranteed on-campus accommodation”, stating that “demand for…campus residences remains strong”.

As for the soft demand at Yukeembruk, the spokesperson pointed out that “it takes time to build these new on-campus communities” explaining that the University expected the first-year and returning cohort to be smaller than more established halls given that it only opened last year: “In comparison, our other residences are made up of both new and returning residents over multiple years.”

The spokesperson did not answer Woroni’s question about the ‘Refer ANU Earn’ program.

7.

by Jocelyn Wong

8.

Art

The Winners And Losers Of Post-Study Visa Cuts

Constance Tan

Late last year, the Albanese government announced in its migration strategy its plan to to cut post-study visa stay periods from four to two years. The strategy, which will be implemented later this year, also includes increasing minimum English language requirements to an equivalent of an International English Language Testing System (IELTS) score of 6.0 for student visas – up from 5.5 –and 6.5 for graduate visas.

The current “genuine temporary entrant” (GTE) requirement will also be replaced with a “genuine student test” (GST), in addition to the lowered age limit for temporary graduate visa applicants from 50 to 35.

Currently, the GTE test requires written proof that potential students intend to return home after completing their studies, as well as a statement of purpose articulating why the student is capable of undertaking the course.

While details of the new GST test have not been released, it will be designed to assess genuine intentions to study rather than work in Australia, including meeting relevant visa requirements like English proficiency, academic qualifications, financial documents, and overall authenticity.

While only a year ago, the federal government announced extensions to the graduate work visa offered to international students, this recent move is the latest in a slate of amendments tightening Australia’s immigration policies.

In December of last year, Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil vouched that the new measures would help “bring [migrant] numbers back under control” and reduce the annual migration intake by about 50%. The federal government affirmed the decision, citing the need to weed out students “whose primary intention is to work rather than study” and to restrict “visa hopping”.

Universities Australia, a representative body of Australia’s universities, previously recommended the implementation of the genuine student test and affirmed their continued support for the Albanese Government’s decision.

The representative body asserted that the updates would mainly “(protect) students from unscrupulous operators seeking to exploit them for personal gain” and concurrently “preserve the integrity and strength of the education system”.

Acknowledging the significant impact international graduates have on Australia’s economy, the organisation emphasised “getting the right people with genuine ambitions” to attend university in the country. They continued, “We must continue to attract them for mutual benefit.”

9.

Art by Jasmin Small

While the changes have been proclaimed to create a fairer and less competitive system for genuine students, it raises questions on who will truly benefit. The issue at hand may not simply be about the education sector at all, but rather a reflection of the bigger migration scene in Australia; of the country’s stance towards immigrants and the government’s attempts to curb it.

The possibility is not unfounded. Overseas-born immigrants make up close to 30% of the population and of those, student and post-study work visa holders make up 3% of temporary migrants. According to a poll conducted mid-2023, a majority of Australians believed their country’s migrant intake is too high.

Granted, the reforms will primarily impact vocational education and training (VET) colleges rather than the higher education sector—given most universities, including the ANU, already require IELTS 6.0 or above for admission—but many international university students still fall through the cracks.

The lowered age limit for graduate visa applicants from 50 to 35 means genuine mature students above the new age no longer qualify for post graduate employment, even though they make up a significant proportion of postgraduate populations at universities. Stricter English language requirements also means that genuine students whose first language is not English may be at a disadvantage.

The inconvenience the new changes bring is not lost on higher education international students. But it is current students already in the system who will bear the brunt of the visa cuts.

A third-year postgraduate ANU medical student explains that the incoming changes to post-study work visas means that her plans to stay on in Australia upon graduation may be derailed.

The student tells Woroni, “the tightening of the [post-study] work visa could make it harder for us to obtain a visa to work in Australia after graduation”. She elaborates, “with the increasing difficulty in (obtaining) a work visa, we have to return to our home country or move to a new country.”

These visa changes come in the wake of a post-Covid era, a period which saw the loosening of immigration policies in an attempt to reintroduce international travel. Today, the Albanese government faces an increasing pressure to streamline the broken migration system left behind by its predecessors, especially in the face of a growing housing crisis in which migrants have been scapegoated as a primary cause.

However, as much as the government stresses upon the benefits its new strategy would bring to international students, the one size fits all policy makes it unconvincing that these measures have genuine intentions.

In the quest for a manageable international student count, the new changes will indiscriminately exclude even genuine students with the right skill sets, especially mature aged students, which raises the question if Australia is heading towards a closed border policy.

While there will be winners and losers in the latest graduate visa policy changes, it remains to be seen if these measures will truly be mutually beneficial like advertised – if they would promise a fairer system for both international graduates and local Australians, or if they will only result in a win-lose situation, one where the losers are international students.

10.

ANUSA 2023 End of Year Report Reveals Increased Demands For Welfare Services

Gisele Weishan

The ANU Student Association’s recently released 2023 End of Year Report highlights the increasing student demands for accommodation and welfare services, as students continue to bear the brunt of the cost of living crisis.

Amongst other things, the report revealed record usages of ANUSA’s welfare services including clubs, the Brian Kenyon Student Space and financial grants.

The report noted, “BKSS usage rose to an all time high this year.” The BKSS offers regular free breakfast to students, affordable snacks and dinner, although the latter are currently suspended. Beyond meals, the building also offers a dedicated student space and free contraceptives. Last year, Queer* Department supplied free gender-affirming gear was distributed at the BKSS along with free menstrual products.

2024 ANUSA Treasurer Will Burfoot (he/him) told Woroni “the BKSS is a key component of ANUSA’s service delivery to students and the current budget for 2024, passed at the last Ordinary General Meeting of 2023, will see an increase to the BKSS of $10,000.”

As for whether any of the other services will be subject to financial changes, Burfoot explained, “We are carefully assessing all of our services and the final financial decision is of course to be made by students at our Ordinary General Meetings, the first of which is in early March.”

11.

In 2023, clubs also saw a significant increase in funding, with the 2023 report noting that it was the “biggest ever spend on Clubs, with $200,000 spent.” The largest expenditure went to supporting ordinary club events. The maximum grant for ordinary club events depends on attendance.

Despite uptakes in the provision of student food services, ANUSA saw a marked decrease in its overall student financial assistance this year. In their 2022 End of Year Report, it was reported that student assistance covered 1,648 successful grant and program applications with $329,571 total financial assistance provided to students.

However in ANUSA’s more recent 2023 End of Year Report, there were 999 total successful grant and program applications with $105,898 total financial assistance provided.

Burfoot attributed the decrease in student financial assistance to a return to pre-COVID-19 pandemic funding as “grant deliveries over [the years 2020, 2021 and 2022] were substantially higher owing to the pandemic and the associated increase in funding provided by the ANU and as a reprioritising based on student needs… As we reached the end of the additional COVID funding we reverted back to our standard allocation.”

Despite this decrease in student financial assistance, the Report revealed an “overall increase in total expenditure” in 2023, as a result of the “expansion of [ANUSA’s] services to encompass all ANU students, including postgraduates’’ unlike previous years.

Former Treasurer Katrina Euijung Ha (she/her) also noted that ANUSA had secured $2.8 million in total, in addition to $446k “for one-off capital expenditures that will be acquitted by the first half of the next year.” Further that “despite the overall increase in total expenditure, ANUSA now stands on a more stable financial footing. We are actively working on ensuring funding for 2024 remains stable as well.”

12.

However, Burfoot explains, “[The Union] of course [has] constraints, a less than ideal SSAF agreement means we cannot aim as high as we were hoping. “

For 2024, ANUSA’s SSAF allocation consists of two million in initial baseline funding and an additional one million for funding in return for capital expenditure costs including the Bla(c)k, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) safe space, upgrades to the BKSS and for the provision of post-graduate services.

Nonetheless, Burfoot remains optimistic,”with prudent and pragmatic management of our finances I feel confident students will continue to see ANUSA as THE service provider on campus.”

According to the 2023 SSAF Survey Report, “Providing health or welfare services to students” remains the most important service to students followed closely by access provided to legal services, support for the specific needs of cohorts and accommodation services.

As such, Burfoot maintains, “We expect to continue to see students engage in our free services in 2024, particularly the postgraduate and HDR cohort where we are seeing strong up-take.”

Disclosure: Woroni is also a recipient of Student Services and Amenities Fee funding.

13.

by Jasmin Small

14.

Art

Home: A Sunburnt Country For Me

I’m sitting in my bedroom at home as I write this. At 19, almost 20, I could tell you quite confidently what home means. I think that this is a privilege — to so easily define home.

For me, home is in Queensland, on the Gold Coast. We are a little further from the sea now, having traded salty air for tall trees and slanting hills. Home sits upon one such hill. Home is a white brick, brown tile, one-storey house with two frangipani trees in the front yard — one is big and the other small. The gardens are Amma’s; she has filled the front yard with abundantly growing flowers, herbs and cacti. In the backyard dwells our mango tree, a blackberry bush and a growing papaya tree, amongst others.

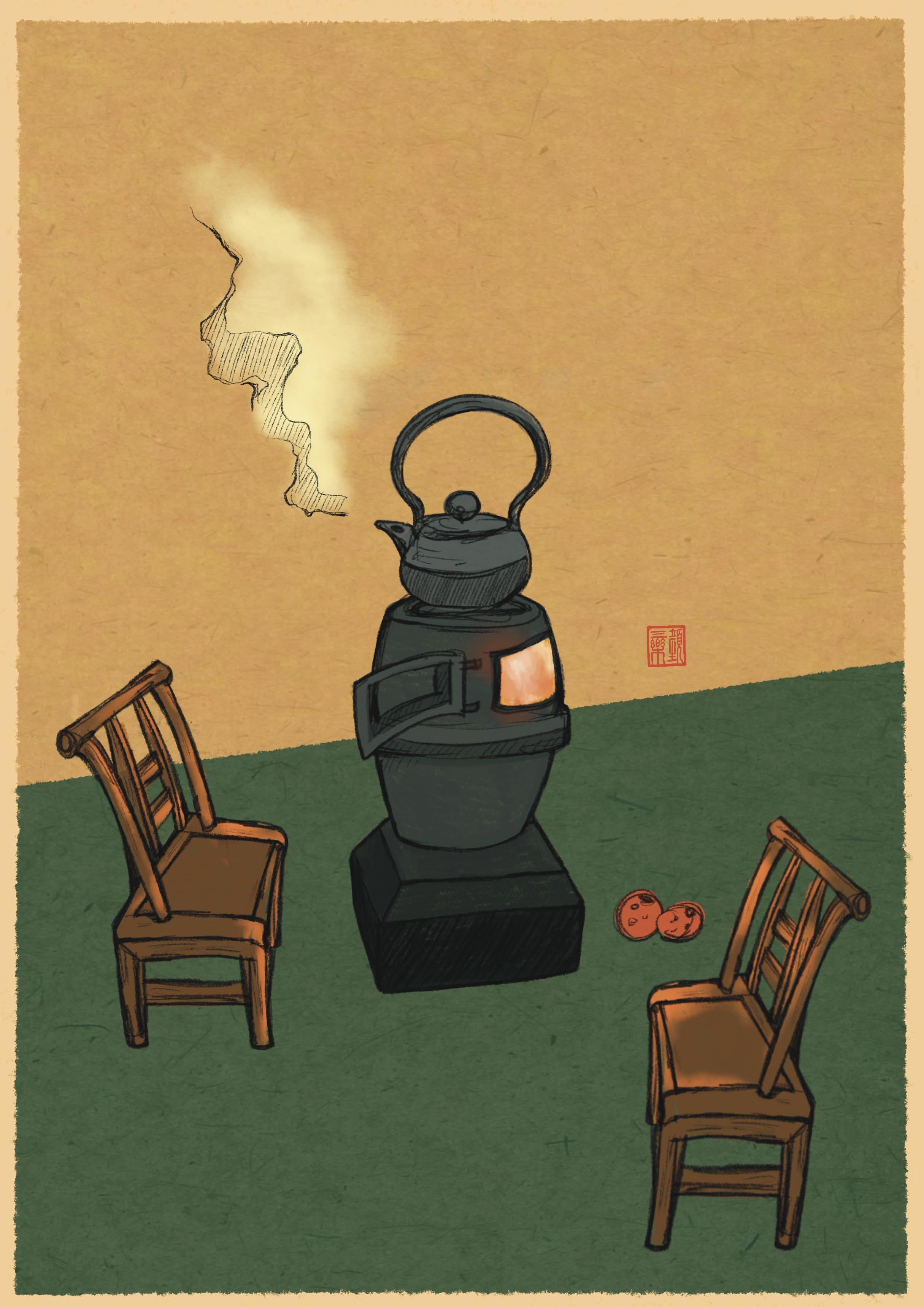

We have the most beautiful sunsets. Around 5pm, almost ritualistically, we sit out on the patio facing the hinterland, watching the sun disappear beneath familiar mountains. I love those afternoons. Brown skin washed with an orange tint from the slipping sun, black hair glowing ever so slightly red, the distinct taste of my mother’s tea, the comfort of our soft chatter and the occasional whine and bark from our dog Vetty begging for a treat.

Yes, I love those afternoons dearly. But I don’t think I would love them as much as I do if I hadn’t moved to Canberra. Something about coming home for the summer and knowing that I have to go back — the twinge of bitterness makes those afternoons all the more sweet, like adding a little coffee to chocolate cake.

I am turning 20 in February, and it feels as though this summer is the last I will have as a child. I know 19 is hardly a child, but that’s how I feel. I remember from Japanese classes that 20 was considered the age of adulthood in Japan. They have a ceremony to mark the occasion called ‘Genpuku’ (元服), the Coming of Age Ceremony. I’m trying to make the best of this summer, grasping greedily at every little moment at home with my family before my own ‘Genpuku’.

The hardest part of this summer is watching my little brothers grow up, knowing that I’m not always going to be here as they do. It’s hard separating from those who have shared everything with you. I took the youngest to get a haircut the other day — he is only 13. A little snarky now, quite proud to be a teenager. But he’ll always be the baby to me. He still looks like one — he’s all chubby cheeks and dark, soft hair — which, to my dismay, he chopped off. My oldest brother is 16, turning 17 mid-year — this I quite frankly refuse to believe. He’s much taller than me now, and he thinks he is so mature. No 16-year-old is mature. But he’s the sweetest kid you’ll ever meet — a proper Steve Rogers type, lawful and kind to a fault. I’ll miss them dearly when I leave next month. But of course, I’ll see them again. Can you imagine not?

I’m embedding all the pieces of this summer into my memory; the scorching Queensland heat, the humidity and evening downpours, having coffee at Cafe Catelina with my parents, going to the temple, helping Amma with her saree, bingeing Christian Bale’s Dark Knight series for movie nights (the best Batman trilogy). All these little domestic moments and beloved old haunts mean home to me. But that’s the thing, the definition of home is pretty solidified for me at this stage, and I’m only just realising how lucky I am in that regard. I know where home is. I know that no matter how homesick I get in Canberra, home is just a short flight away. Home for me is this country and the people in it — it’s really all I’ve known. I could describe home to you as Dorothea Mackellar might:

15.

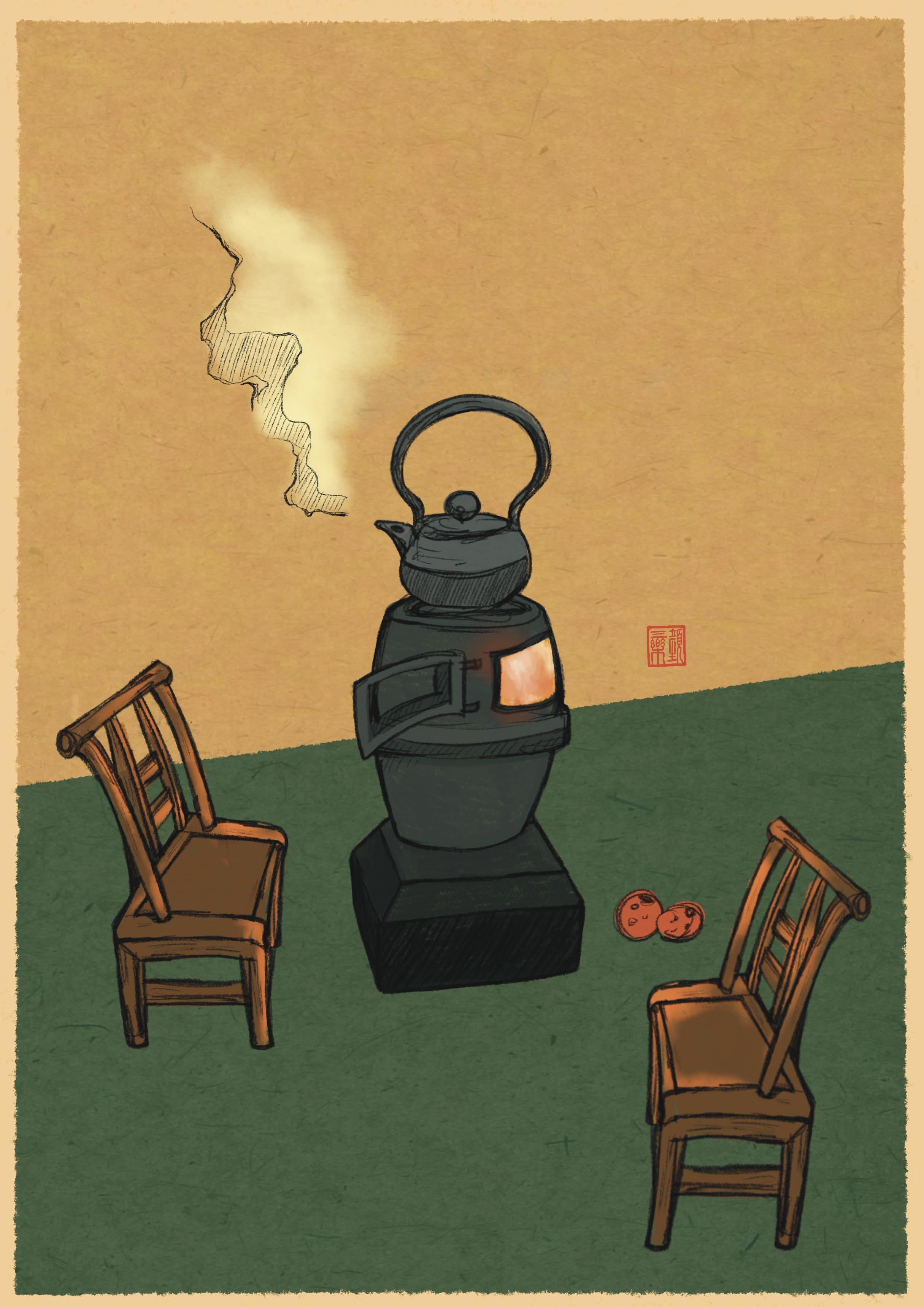

Atputha Rahavan Art by Sanle Yan

“I love my sunburnt country, A land of sweeping plains, Of ragged mountains ranges, Of droughts and flooding rains, I love her far horizons, I love her jewel-sea, Her beauty and her terror - The wide brown land for me!”

I love that poem; it’s one of my favourites. But I don’t think home can be defined so easily for some. It certainly can’t be defined so easily by my parents. They came to Australia in 2009 as asylum seekers, escaping Sri Lanka amidst the end of a devastating, decades-long civil war. They turned 20 on another island, surrounded by a different jewel-sea — but one just as beautiful, I’m told. Instead of flooding rains, they had their summer monsoons. And the horizons on that little island weren’t as far as they are on this one.

They went through their ‘Genpuku’ in circumstances very different from mine. Gunshots and bomb threats to confetti and cake.

I’ve been thinking a great deal about this as we near February. For them, at the age of 20, home meant a very different thing and was a very different place than it is for me. This was decades ago, but something similar is happening again in another country. When we hear about the genocide, I wonder how my parents feel. Different people but an all too familiar, heart-breaking fate.

For me, home is a sunburnt country. For them, their country, their home, is left behind. For them, home is bloodied, war-torn and beyond recognition. Only dust remains of once well-loved houses and carefully curated gardens. Some fathers and mothers are forever lost in the rubble of decimated holy ground. Some little brothers are never to be seen again. I could never bear it. Imagine bearing it.

I wonder if Amma and Appa will ever define home the same as me? I wonder if Australia is to them only as the English countryside was to Mackellar; beautiful and safe but never quite home. I wonder what it feels like, continuing on with life, knowing in the back of your mind that you might never return to the country of your childhood, never again set foot in the country of your kith and kin? I wonder, for my parents and all like them, if a piece will always be missing from their definition of home? I might ask them tomorrow. I think I’m old enough to know.

It is a privilege to so easily define home.

When I return to Canberra next month, when I miss the home I so confidently know, I think I’ll savour the homesickness a little more; I think I’ll have more gratitude for it. I’ll take the bitterness, knowing the sweetness will always be there. Knowing that for some, home is not so easily defined.

16.

Art by Sanle Yan

17. Art by Vera Tan

Lost on Campus

Why academia and the uncanny go hand in hand

Cleo Robins

Returning to campus after the summer can, in a paradoxical kind of way, feel like a homecoming. You reunite with friends, who are often as near and dear to you as your own family. You return to the streets and buildings that have witnessed some of your most intimate moments: sweaty dashes to forgotten lectures, tears in bathrooms, laughter echoing across lawns. And you slip back into a routine, study grounding you in a way that casual work and spontaneous road trips rarely can. With campus life providing such a rich array of experiences to mine for creative output, it’s no wonder that writers return time and time again to stories set in the hallowed halls of universities. What is less clear is why so many of the novels about academia are steeped in Gothic and horror tropes. From group murders to cults to dark magic to gory rituals, the genre of dark academia has produced some truly chilling tales. But how did the aesthetic movement take shape? And more importantly, why do its sordid little tales continue to fascinate us?

Despite so many novels fitting into its generic confines, dark academia is not technically a literary genre. In fact, it is more aptly described in a rather contemporary way as an internet aesthetic. The New York Times describes dark academia as “a subculture with a heavy emphasis on reading, writing, and learning”. It identifies its origins as the mid-2010s when Tumblr usage was at its height. The images that internet users invoke to embody this aesthetic are of gothic architecture and interior design, as well as tweed, autumn-hued fashion pieces. Dark academia has recently gained increased traction on Instagram and TikTok. Popular, theorised the Times, because many young people were deprived of their on-campus experience due to COVID-19 lockdowns. And as with all good online trends, its proponents have retroactively created a literary canon to epitomise its trappings.

The novel most closely associated with dark academia is Donna Tartt’s cult classic, The Secret History (1992). The Secret History tells the story of a tight-knit group of Greek scholars whose commitment to their field of study causes irreparable ruptures in their friendship. It’s not a spoiler to say that the novel’s focus is a murder - Tartt begins the book with this fact. The crime is the driving force of the plot, but rather than the academic elements taking a back seat, they actually play a key role in the development of the central characters’ relationships. Due to Tartt’s decision to reveal the murder (and its perpetrators) in the novel’s first pages, the entire experience of reading The Secret History is suffused with a sense of dread and foreboding. That which is familiar - three-hour tutorials, endless readings, heated literary discussions, even drunken parties - becomes sinister. Once the plot has run its course and the consequences of the pivotal act have reached its climax, you’re left with a strange sense that academia itself has caused the death, an uneasy thought that disrupts the conception of the university as a homely, friendly place. Not only does Tartt’s novel capture the all-consuming nature of a cohort friend group, but it also pioneers the idea that academia and the Gothic are inextricably linked.

The key to understanding Tartt’s decision to set a murder story in a university is the concept of the uncanny. The term was developed (but not originated) by Sigmund Freud in 1919 and is used by many literary scholars to describe the disquieting essence of the Gothic style. While in English, we use the term “uncanny”, when translated from the original German, “unheimlich”, it literally means “not from home.” Freud saw the uncanny as the feeling one experiences when the ordinary becomes strange and was fascinated by the angst that arises from this paradox. The Secret History’s constant hum of literary unease perfectly embodies Freud’s description, and so too do other dark academia texts, albeit in a more overt way – by using magic and the macabre.

18.

R.F. Kuang’s Babel (2022) is one such example. Set in a fantastical 19th-century Oxford, Kuang fuses her academic setting with an innovative magic system to construct a treatise on colonialism and the politics of labour. Despite its subject matter differing substantially from The Secret History, Kuang’s book similarly uses the uncanny to convey its central theme. For one, the presence of magic in the world of Babel makes its Victorian setting seem slightly askew. However, Kuang’s use of the uncanny comes to the fore at the novel’s climax, when Chinese-born protagonist Robin Swift returns to England after a business trip to his home nation after over a decade of living at the centre of the British Empire. Upon his return, Robin experiences a profound sense of unease; people on the street seem to regard him differently, and the milieu of his beloved Oxford is more ominous than when he left. This malaise that Robin feels is not only the result of a crime he committed on the journey home but also of a change in his psyche. Experiencing China as an outsider, especially as someone complicit in the work of the British Empire, has shown Robin how not only he but entire nations have been exploited by the colonial project. Kuang’s use of the uncanny in her work of dark academica fiction, therefore, functions not only as a stylistic device but as a comment on the absurd, abject strangeness of colonisation.

Babel is not the only 21st-century iteration of dark academia fiction. Mona Awad’s Bunny (2019) pushes the aesthetic into horror territory, while Leigh Bardugo’s Ninth House (2019) delves into the cultish nature of university societies. The dark academia hashtag has tens of thousands of posts on TikTok, and even the recent internet-breaking movie Saltburn (2023) made reference to the aesthetic in its visual style. While their subject matter and messages are starkly different, all of these pieces of media use the uncanny in some way or another to subvert the expectations of their audience.

So, why is it that academia and the uncanny can’t seem to extricate themselves from one another? Perhaps it is dark academia’s ability to convey nuanced societal critiques. There is a growing cultural understanding that Western science and philosophy will not save the world from the effects of colonial destruction and that universities are part of the toolkit used to maintain the status quo. Dark academia allows creators like R.F. Kuang to express the absurdity of academic prestige and to try to imagine something different, albeit something fantastical and dark. Or perhaps dark academia’s popularity can be explained by its relatability. Moving away from home and discovering the world is always jarring, and doing so at an institution that simultaneously exposes you to the real world as it shelters you from it even more. Dark academia allows creators to reflect on the often tumultuous experience of university study in order to find some meaning from it. Ultimately, it is likely a combination of all of these factors – our tendency to romanticise our lives and our hunger for content that helps us reconcile the dark, exclusive past of universities with our present-day experience – which makes the style so popular. Perhaps we just love to be horrified every now and then. Or perhaps dark academia endures because it hits so close to home.

19.

Art by Xiaochen (Fiona)

Bao

Art

by Amanda Lim

The Call of Home

Hayley Tobin

So, where’s home for you?

The typical icebreaker, on the lips of first years and fourth years alike, nestled between “What’s your name?” and “What’re you studying?” is such a simple question for so many. However the answer fills me with a sense of dread, and I quickly start to panic as I wonder how to properly sum up the broadness of what ‘home’ means to me.

Do I answer Mackay, the regional city in central Queensland where I was born, but have no memory of? Or should I answer Bundaberg, where I spent the first few years of my life growing up? My parents still own a home there, but we haven’t lived there since I was seven.

From there, the water only gets murkier. After a few years of roughing it in public education, my parents, both teachers, made the daring decision to spend two years teaching abroad in an international school in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. The decision was undoubtedly unheard of, and was met with uneasy trepidation from the rest of my extended family. However, my parents assured them that after two years, we would return home having gained some world experience, unique perspectives and unforgettable memories.

This was not to be the case. If the home of Angkor Wat didn’t seem foreign enough, this time my parents accepted a position in Zimbabwe, where, at the time, authoritarian Robert Mugabe still controlled the country. We spent five years there, and absolutely loved it. Oftentimes, when I picture home, I remember the blood-red colour of the African soil staining my skin, sitting underneath a purple canopy of jacaranda trees, and the deep throaty roar of a lion ringing through the bush. Someone once said that Africa gets under your skin, and it is certainly true.

However, given the nature of international teaching, our journey did not end there. I started Grade 10 in Uzbekistan, a country in Central Asia along the famous Silk Road, and continued there until graduation. Unfortunately, most of our time there was marred by the global pandemic and we found ourselves isolating like the rest of the world.

20.

For so long, the answer to this question was always so easy. Australia, I’d confidently answer. As one may imagine, Australians are few and far to come by in remote areas of Cambodia, Zimbabwe and Uzbekistan, and so my answer was rarely elaborated on. However, by the time I started university in 2022, my family had just moved to Fiji. As one of ANU’s 17,000 domestic students, I could no longer simply answer Australia, nor Queensland, and thus found myself at a loss. Should I answer Zimbabwe, where we’d spent the years I most remember? Or Uzbekistan, where I’d most recently lived and graduated university? Or should I answer Fiji, a country I’d never even been to before, but where my parents and sisters now lived?

I’ve found that home depends on context. When I am outside of Australia, the answer is simply there. When I am in Queensland, my answer is Canberra, where I’ve now lived and studied for two years. When I am in Canberra, I will most often answer Queensland, however, if pushed, may recount the elaborate tale.

Although my childhood was unique, I think that as students and young adults the transition from childhood to adulthood has brought ‘home’ into question for a lot of us. For those who have been living in Canberra for a number of years now, it is becoming a home of its own, separate to that of your family home. However, whilst here, many of us will answer this question with wherever our families currently are. And on top of that, I would challenge you to consider where home would be to you if your family moved away from the town or city they currently reside in. Is home the land itself, etched forever into the tapestry of your lives, or is it your family unit themselves? Is home a place, or a person? For so many years, my home was wherever my family was, however now that I am starting to make my own way in the world, that means redefining what home means to me, and making my own home, here.

Queensland, I’ll answer, with a small smile. My fingers are crossed behind my back, praying they won’t ask me where exactly. As I subtly shift the conversation away from the topic, my brain wanders back home. Home, where my mother’s arms are held open wide to embrace me. Home, where the hot sun beats down onto my back. Home, which is a delicious blend of familiar incertitude. A place simultaneously concrete and imaginary. It is where I throw my clothes on the floor after a long day. It is the smell of markets and sweat imprinted in my scent memory. It is the sea breeze dancing through my hair. The soft snow melting on my tongue. Home is a conveyor belt carrying my luggage away into the deep belly of a plane. Home is both nowhere and everywhere.

21.

Art by Amanda Lim

The Dutch House: Houses, Homes and Hearts

Aala Cheema

‘House’ and ‘home’ are terms that are often used interchangeably. Treated as homogenous, they are perceived as one and the same. However, a house isn’t always a home, and a home isn’t always a house.

Ann Patchett’s 2019 novel, The Dutch House, weaves a compelling narrative about the meaning of home. A finalist for the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, the novel begins in the post-war period and follows two siblings, Danny and Maeve Conroy. The deuteragonists grow up in a mansion monikered the eponymous Dutch House in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania. For five long decades, that house remains tormentful and haunting to not only the Conroy family, but all those who interact with it.

A magnificent piece of neoclassical architecture that toes the line between Mediterranean and French, the 1922 house is named for its previous Dutch owners, the Van Hoebeeks. Described as ‘a piece of art’, the house is fitted with marble floors, fireplaces, blue delft mantels, egg-and-dart crown moulded ceilings, and even a ballroom. Imposing oil paintings and portraits of the mythical Van Hoebeeks scrutinise the inhabitants from their place upon the wall while silk drapes, yellow silk chairs, tapestry ottomans, Chinese lamps, silver cigarette boxes and a glass-fronted secretary adorn the house. Even the foyer contributes to the house’s splendour, with its round marble-topped table, French chairs, a mirror framed by the arms of a golden octopus, and a grandfather clock with a ship rocking between two rows of painted metal waves.

Maeve and Danny’s parents, Elna and Cyril, acquire the Dutch House due to a combination of happenstance and luck. A burgeoning property developer, Cyril buys the house and its contents and even retains its staff in 1946 after the Van Hoebeeks go bankrupt. The house has an unexpected influence on the couple’s marriage. While Cyril feels accomplished and esteemed by the majestic acquisition, Elna feels undeserving of such affluence and begins to hate the house. As the guilt of living with extreme wealth overpowers her, she descends into misery. Ultimately, she abandons the family, fleeing to India to help the poor and the destitute.

Even the remaining members of the family are at times mortified by the excessive indulgence of their residence. Gilded with carved leaves and painted deep blue, the dining room ceiling is described as “more in keeping with Versailles than Eastern Pennsylvania”. Danny remarks how he, Maeve, and Cyril, “made a point of keeping our eyes on our plates during dinner.”

22.

Art by Cynthia Weng

After Elna leaves the family, Cyril retreats to his work, and Maeve primarily raises Danny. She becomes his mother, sister, friend, caretaker, and confidant. Danny’s love for his sister is greater than any other love he feels throughout his life. Cyril eventually remarries a younger woman named Andrea. He does not marry her because he loves her, but because Andrea loves the Dutch House, unlike his first wife: “[Cyril] thought that house was the most beautiful thing in the world and he found himself a woman who agreed…[Elna] hated it and Andrea loved it. He thought he’d solved the problem.”

Maeve and Danny, despite having a positive relationship with Andrea’s two children, Norma and Bright, have a mutual dislike for Andrea. When Danny is 15, his father suddenly dies from a heart attack. Soon after, Andrea kicks Danny out of the Dutch House. The siblings manage to move on with their lives, for the most part. However, for years after their banishment, Danny and Maeve engage in an almost ritualistic practice of sitting outside the Dutch House in their car, watching it and its inhabitants and reminiscing about their childhoods. For Maeve, it is her only connection to her mother. For Danny, the house is representative of all that he has lost. Only years later, he realises the truth about their sittings outside the Dutch House: “We pretended that what we had lost was the house, not our mother, not our father. We pretended that what we had lost had been taken from us by the person who still lived inside.”

The characters of The Dutch House reckon with finding their home. Andrea, convinced that the beauty of the Dutch House is unsurpassable, devotes her efforts to retaining ownership of it. In the process, she earns the resentment and estrangement of her own two children, who feel the unfairness of her treatment towards the Conroy siblings. She, therefore, loses the people that should have been most important to her in exchange for a dwelling. Elna finds home in the charity work she dispenses with almost saint-like precision. However, she is unable to extend to her own family the same love and consideration that she administers to the poor. Danny, too, observes that his own interpretation of home was misguided: “Because I was fifteen and generally an idiot, I thought that feeling of home I was experiencing had to do with the car and where it was parked, instead of attributing it wholly and gratefully to my sister.”

The Dutch House expounds that home is not necessarily the place where we may reside or even grow up. It may not even be the work that we feel most passionately for. Instead, home can be found in the people who fiercely love us and dedicate their lives to care for us. Home is more than a building, and it is more than a calling. It is the pang of jubilation we feel and the cloak of safety we adorn when we think of those we love most in the world.

23.

Can You Afford to Leave the Sharehouse Behind?

Sarah Greaves

Young people seemed to be gripped by a sort of existential dread these days, and not without reason. Faced with a dying planet, political polarisation and the positioning of jorts as peak fashion, there are seemingly limited prospects for a bright future. To add to these worries is the now almost collective acknowledgement that homeownership is a near impossible feat, weighed down not only by shockingly high house prices but also six figure HECS debts, incredibly undesirable interest rates and $10 bags of shredded cheese.

To make matters worse, there is the continual insistence from a particular section of society that this despair is not actually a reflection of the degradation of a mythological Australian meritocracy. Instead, your inability to even fathom the idea of buying a house arises from this generation’s expectation for everything to be handed to them on a plate. An undeniably infuriating notion given the fact that the multitude of these complainants had free or very cheap tertiary education and house prices that were around 20 percent of what they are today, even when adjusted for inflation.

Despite my initial fretting over my ability to ever own a home, my fears were recently abetted by the highly publicised Suburbtrends report. Apparently, an annual income of a mere $300,000 is all you need to buy a house. Like many others, I was struck by the realisation that I should probably substitute my career aspirations with the far more productive search for a partner willing to provide the necessary income needed to afford a house.

The unattainability of a $300,000 annual income cannot be overemphasised. The highest salaried profession in this country is an anaesthetist. According to the ABC, the average (female) anaesthetist’s annual income sits at about $325,000 — a just about sufficient amount to begin affording a house (ignoring the medical school HECS debt). As of 2016, there were 4,373 qualified anaesthetists in Australia. Even if we take this number to have risen to a generous 5,000, that is still only 0.019 percent of the Australian population. To be clear, the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research estimates there are currently 59,000 heroin addicts in the country, making up 0.23 percent of the population. Twelve times the number of anaesthetists. As a woman, the two next highest-paid professions available to me are a surgeon or a ‘legislator’. However, both pay an annual wage of $250,000, an enormously handsome wage placing one in the top 1 per cent of Australian earners, but is still not enough by this $300,000 metric.

24.

Which begs the question: who to marry? Even in an ideal world of equal contribution, both parties would need to be earning at least $150,000 — a salary typically achieved by less than 10 percent of the population. In the face of such statistical improbability, the conclusion is clear. In light of an extraordinary cost of living, the Australian government is using economic incentives to destroy the nuclear family and transform this nation into one of endless group cohabitation.

Of course, I am leaving out one significant factor that explains why this situation persists. My focus on searching for a salary that would enable me to buy a house was unsuccessful because so few people today are able to buy a house purely with their salary. Australia’s housing crisis is a display of systemic inequality.

Older generations were able to buy into the property market long ago under vastly different circumstances. They were then incentivised to monopolise property ownership via the acquisition of enormous investment property profiles, built up through the assistance of negative gearing. This leaves a gaping generational divide in the ownership of wealth in this country that can only be bridged by the transfer of assets between such generations. As put by data analyst Kent Lardner, the availability and stability of the ‘bank of Mum and Dad’ is now a significant factor in whether you will be able to buy a house, and how nice that house is.

Australia’s policy of negative gearing is one of the most insidious means of perpetuating not just a climate of inequality but also one that is actively opposed to the traditional Australian conceptions of hard work, merit and a ‘fair go’. These values are often (and with good reason) dismissed amongst the modern left as tools to cement a neoliberal and systemically unfair capitalistic society. However, this does not render the current situation any less undesirable or hypocritical. Indeed, despite my in-depth account of the near total impossibility of hard work to equate to home ownership, there is still an insistence that the anxiety felt by the youth of today is one representative of their own rejection of hard work. There is an almost head-in-the-sand approach to the fact that Australian meritocracy (if it ever existed) is dead, and that the current housing crisis is a symptom of this.

Ironically, if this country wants to maintain any semblance of a liberal economy guided forward by the “Australian dream”, it must acknowledge that current policies are not acts of deregulation, freeing up a housing market and cutting away red tape. Instead, these are actions with deeply illiberal consequences, designed to keep wealth in the hands of a select few.

25.

In Defence of Vanilla

Lachlan Peele

We’re on the tram, cruising past stop-start traffic.

“I think my body yearns for the Salsa… but my mind, it just, understands the Bachata more”

And you’re just talking.

“Like, I’m just built for it, don’t you think?”

I love the tram, but in the same way that a Christian church-goer may love a mosque.

“Those dancers were pretty impressive still”

I respect it as a place of worship and recognise its power in gathering large numbers of people, but I’ll always prefer the train, simply because I grew up on the train.

“I think my stop is coming up”

It’s not, but I don’t like it when people talk in places of worship. I find it disrespectful to the sermon. And today, on this overcast but warm Tuesday, it really is such a wonderful sermon: With every jarring start and jolting stop we are asked to appeal to our inner patience. ‘Love thy neighbour’ is prominent, seeing as it is hard not to forgive them for the inevitable invasion of personal space as the carriage rocks back and forth. A motion that, every now and then, sees even the most experienced of commuters fall into the at once both familiar and estranging place of a mother’s lap, much to the dismay of the child that used to be there. Finally, the high pitched squeaking of metal brakes reminds us to cherish what silence we can find in this life, as it is silence that brings true peace… “I thought yours wasn’t for another four stops?” The tram squeaks then jolts to a stop. “Yep, this is me”

“No, it’s not”

The tram doors open and I look out, past the coming and going of passengers — their heads bowed to shield their faces from a light shower that had been brewing all day — and I see the street, tarmac darkening in the rain, the traffic crawling as people run for shelter on the footpath or stiffen up and keep walking as if they could raise their shoulders high enough to shield themselves from the rain above. Walking stiffly, their shoulders two great peaks and their heads disembodied and rolling in the valley. The tram doors close.

“Anyway, I actually don’t think I can make it to your parents’ thing this weekend” I remember playing in the shed of my parents suburban house.

“It’s just going to be too hot, thirty-five degrees on Sunday! Can you believe it?”

I can believe it, it was practically unbearable in summer, but at least then she’d offered some shade. Just four corrugated walls and one corrugated roof, a shed in its most pure form: you would pay for the shade with constant watery eyes as your body desperately tried to defend itself from the sawdust particles. Holes too, in abundance, sporadically appearing and disappearing, never in the same place you remembered them. Yet, I have such distinct memories of the light of the sun through those holes.

26.

Art by Sanle Yan

The sun in those summers would pierce you like a blade, making millions of deep and enduring cuts under the skin so that no matter how you contorted to escape it, you would be left at the end of the day feeling betrayed by your own bed and dreading the weight of even the finest cotton shirts. The blades of the sun, I used to think, were responsible for all the holes in the shed — they must have been! — cutting through the iron as easily as it cuts down the softest of spring flowers and makes them wilt. I used to run to the shed to escape the daily onslaught on my skin and still, even once inside, tentatively dance around the beams piercing through the holes. Then, while dancing between the blades of light, I would wallow in the despair of an inescapable heat, as a speck of bacteria might accept their own fate in a sink of soapy water, after jumping ship from a spoon to a colander.

But I quickly noticed, and came to appreciate, that these beams of light, these precious rays, did not provide the same familiar sting as those outside the shed. These rays, while they came in with such anger and keenness to cut became soft, immediately dissipating into a gentle glow as they would catch and bounce upon the omnipresent sawdust. The glow of the dust illuminating the ancient and withered spider webs that adorned the corners of the shed and encircled the lone, long blown, lightbulb, like a wreath made of silk string. The same sawdust that floated upwards as if to purposefully make its way into your eyes and throat. I remember how I hated the stinging but I also remember the distinct aroma. The stains my parents would use on everything they fashioned or repaired, mostly jarrah, left me with a disdain for the colour but a fondness for the smell. I remember feeling grateful on days the sawdust was forgiving and settled in the nook of my nostril as opposed to the corner of my eye. I remember how the sawdust, even with all its stinging and itchy eyes, created the sights and smells of my childhood.

“You’re welcome to come to mine, our apartment has air-conditioning and a pool.”

I’m staring blankly at the window. There is a spider web in the top left corner.

“That would be nice, thank you, but I really should see my parents.”

The web appears to house within it, a tiny and patient spider; and, to my surprise, I notice it is on the inside of the tram. Where surely no fly or unfortunate insect would find it.

“You can make a living like that?”

“Hm? Oh yeah, the apartment really isn’t that expensive, I mean, It’s not cheap either but we manage.”

Another squeak, another stop.

“Well… this is me.”

“Come on, really? I know it isn’t”

The tram doors open again and I catch a glimpse of the street briefly, it has stopped raining, before we are flooded with a batch of new, tired and worn faces. There is a balding man in a tweed suit who squeezes through to find his spot amongst the rest of us as if he was fumbling through a ball pit to find his wallet. When he finally arrives at a suitable enough destination he sinks, not into the ground but into his shoes and his tucked in shirt, as if he had spent all day holding himself up from the skin on his forehead and was finally now his true self. Sunk into his shoes, with his gut pressed against his yellow stained shirt and the flesh on his eyebrows now almost completely curtaining his vision, I wonder if he had in fact always been there. The doors linger open.

“Okay, I’ll see ya next week.”

“Seriously?”

“Yep, I don’t make the rules, this is definitely my stop.”

“Your stop is in two… You’re really gonna wal-”

The tram doors close.

“I’ll see you tomorrow.”

I mouth from the gutter. You’re shaking your head but you’re smiling.

27.

Art by Sanle Yan

Driving Lessons

Annalise Hall

Driving to work these days feels as much like a betrayal as it does a fulfilment of prophecy.

This is not where I learnt to drive. I learnt to drive in a city 3 hours from here, although some may call it a town. I learnt to drive with my mum in the passenger seat and my brother in the back, travelling to the same familiar places. At times, it felt monotonous, but once I had finally passed that learning stage, it was comforting. Driving to my own job, in my own car, on my own time, through roads I realised had become committed to memory. In a place that now felt like home in a way it never had before. Like it was mine.

So what was I doing here just a few weeks later? Driving? My car was made to drive in that city, 3 hours away. Its wheels were worn into the pothole-ridden road — potholes which it avoided like an enemy, but which it knew like one, too. Here, the roads felt almost unapproachable, too untouched, like I could’ve slid off them without a chance to adapt to them. I used a GPS for the first time.

My car became an unwelcome guest, but I was also sitting in the wrong seat. While I’m here, I’m supposed to be in the back seat. That’s the only way it feels familiar. While I’m here, I don’t know the traffic lights that always take forever to change. While I’m here, I don’t know the best lane to be in and when to turn into it, or the shortcuts to take if you want to avoid peak-hour traffic. But I do remember the sight of the houses that lined the streets on the way to school and back. The windscreen wipers going up, then down, then up, then down. My dad tapping his thumb on the steering wheel along to the music. That’s home. How can the place I learnt through the backseat with my brother on the way to primary school be the same place where I’m now driving myself to work?

Although, as time has passed, I’ve begun to experience a sense of familiarity I don’t have a word for — I don’t think there is one in English. I can’t imagine describing it in only one word. I first felt it while driving to work on a winter’s day — the time had just reached the hour, and the sound of the Triple J news began to play. That was a sound that took me straight to the back seat, as did the 2005 chart-topper that had preceded it. I was wearing a warm coat my mum had given me — the one that used to be hers. She’d bought it from the place she’d been working at the time, in the same building I was driving to.

Until that moment, I’d never experienced such an overwhelming collision of past, present, and future. I was experiencing them all at once, from two pairs of eyes. My experience of distance went through a similarly drastic transformation. Despite it being a period when my mother had never felt so far away, suddenly, I could feel her in my DNA.

Sometimes while I’m here and driving, it feels like an old friend replacing a new one. Like a shirt I wish I could’ve grown into, but am instead awkwardly attempting to try on again. Sometimes I wish I didn’t have to use the word ‘again’ — a word that reminds me that I’m moving backwards, yet somehow as far from the past as I’ve ever been. But sometimes ‘again’ feels like ‘always’. A word that reminds me that the past and the present are the same and move in a constant cycle. It’s when I remember that the sight of Black Mountain Tower will always feel like a warm embrace, whether I’m sitting in the driver’s seat or in the back.

28.

Art by Jasmin Small

Sprout Street

Charlotte McLeod

My first home on Sprout Street was a fixer-upper that was never quite fixed. The bathroom down the hall remained unpainted, with heaps of insulation near a hole in the floor I was told would send me straight through the kitchen ceiling.

A few of the lights in the kitchen hung out of their sockets by their wires. Alexandra and I danced to songs of the 70s and 80s - our parents’ taste – in the warm light. The kitchen would smell of Mum’s cooking; maybe the rich smell of bolognese or perhaps the sweetness of baked goods for dessert. On the unplastered walls at the back of the kitchen, we marked our heights each year with a pencil or stuck up increasingly undecipherable scribbles.

I trampled over the slabs of concrete and wild onions that grew in my ‘jungle’. There was a lone fruit tree at the back of the garden (if you could call it that), and one morning, a stepladder was left below. It creaked and wobbled slightly under my weight as I clambered upon it. The apples above me were uneven in size, somewhat dull with brown spots and the occasional worm. They were real apples, not coated with wax or pesticides. I plucked one of the low-hanging fruit and sat barefoot against the trunk to eat it, shaded mostly from the sun, which fell in dappled pools of light around me.

When I returned in 2018, the floors were varnished and glossy. I could see my weary and jet-lagged 16-year-old reflection – less round than years before, without the thick, embarrassing fringe of childhood. Mum and Dad hoped for inspections and a buyer.

The backyard was perfectly manicured, with green grass and sickly pink flower bushes around the perimeter. The garden felt so bright it was like someone had turned the saturation up artificially – the reds were lobster, and the greens were headache-inducing. No children played in the garden anymore.

The bathroom had been tiled, and the hole repaired. An entirely new and unfamiliar bathroom had been built on the second floor.

The apple tree had been cut down, and new turf rolled over its place.

29.

Art by Jasmin Small

30.

by

Art

Jasmin Small

Berlin

Sigourney Vallis

I dream I’m running through tall, shapeless black blocks. At every turn, more stretch out. With no distinct features, I can’t tell where I’ve come from or where I’m going. I search for lofty Eucalyptus trees and the crisscross of overhead electrical wires. I want the caw of magpies to break the mechanical silence. But there’s nothing of Sydney in this place, nothing of you. I wait for something to take shape.

I blink, open my eyes, and I’m sent back to my reality where someone, whose name I learnt last night, has flung his limbs over me. A stranger in another stranger’s arms. I avoid looking at his face, knowing it’s not yours. At least I have his heat. From the window, I know it’s almost time to get up. When I first arrived in Berlin months ago, the sky seemed the same opaque grey at all hours. I’ve learnt to notice the subtleties and search for that dull blue glow.

“I’ve got work in an hour or so,” I tell him. Curt, unfeeling, a clear signal of what’s to follow. I’m impressed with my increasing skill in negotiating all things casual and uncommitted. “Yes, no problem. I leave now.” He dresses with noted efficiency and hesitates before giving me a kiss on the cheek goodbye.

When I emerge from my room, Ailish is slathering her bread with too much butter in the kitchen. I heard her through the wall again last night, talking in her sleep, saying sorry, I’m so sorry, over and over again. We’ve spent minimal time together, so I don’t want to ask about it. She seems lighthearted otherwise, but I suspect that’s just the Irish accent.

“Everyone remembers tonight’s dinner?” Hanna strides in, hair pinned high, grey slacks, and a long black puffer. Sleek, cool and collected, she pencils things in. She pencils in our chores and paying bills, and now she pencils in our overdue bonding dinner.

“Yes, I’ll be there for sure!” Ailish sings. I echo her and leave before I change my mind.

31.

Art by Brandon Sung

The U-Bahn is always a punishing ride. When I get on, my ears itch to hear something I understand, even better, a laconic Australian drawl. But every commuter’s a paid actor, there to remind me I’ve not been cast. Then I’ll see someone who reminds me of you. Berlin is full of photocopies. Today, he gets on at Alexanderplatz. Brown leather jacket, white t-shirt, slight hump protruding, a lazy arm thrown over the partition, fingers tapping, a splattering of facial hair, solid moustache, slightly sweaty brown hair, furrowed eyebrows, reading a book. Exactly like you. I’ll spend some time observing, letting my mind recreate suppressed moments, substituting his face for yours. Eventually, he’ll leave, or I will, and it’s like breaking up again. In one sudden, small but violent gas leak, the entire city of Sydney emptied of air. My home was left deflated.

In Gesundbrunnen-Center, I take orders and serve at Pizza Pasta Tralala. On slow days, like today, I watch. Old people shuffle around aimlessly, left behind in life, and mums examine long receipts, kids clinging to them. People tapping their feet, hanging their heads, rubbing their necks and shoulders. Lives under the microscope of the cool overhead lighting. I’m hanging by the counter today, contemplating. Where would I be if I hadn’t responded to your Facebook marketplace ad about a mid-century sideboard? If I hadn’t picked it up? If you hadn’t offered to help carry it? It’s an amusement park with endless opportunities to play with regret and longing. The clock says two hours to go.

After work, I’m spat back into the cold. Wind roars over slick black roads through grey gnarled trees and boxy buildings. Walking from the station, I see kids laughing at the bus stop, pushing each other into the dirty snow. A couple shares an umbrella, and an elderly woman chats angrily on the phone. Pitiful jealousy worms its way through me. The city’s sharp edges and corners are cushioned with significance for these people. They collided with a car on their bike over there; their iconic leather jacket is from that shop; that awkward encounter with a high school teacher happened at that bar, and their parents met in that house. In Berlin, life happens in front of me, but I’m separated from it by an invisible film, sturdy and unbreakable.

The housemate dinner drags. Unsurprisingly. Our common interests are limited to living in the same apartment.

“How’s work?” Ailish asks Hanna, pushing a potato around her plate.

“It’s ok,” Hanna replies. Ailish and I murmur our approval. There’s nothing left to say, so we just nod slightly as though a conversation is taking place.

“Ok, no, I’ve had enough.” Hanna’s abrupt response wakes me up.

“A work friend has a younger brother who is in a fraternity - yes, we have those in Germany - and they have a party tonight, and yes, we are going. No excuses.”

32.

Ailish and I recite the usual: work early tomorrow, not really up to it, actually feeling a little sick. It’s futile since Hanna’s already showcasing outfit options. Ailish gives in and puts on some house music. We’re committed to the night now. There’s really nothing better to do. ***

Leaving the apartment, the only place we’ve been together, is like being on school camp. Our inhibitions are left at home, and a shy excitement sets in. On the tram, we’re laughing at everything, draping our limbs over each other to squeeze into a single seat.

“I’ve heard they keep an embryo jar at the house,” Hanna whispers, lowering her voice. “We should find it!” Ailish insists, and laughter ruptures out of us. Seizing the moment, I can’t stop myself from asking.

“Hey, Ailish, why do you say sorry in your sleep?” Ailish reddens, and I hope I haven’t muddied clear waters. Hanna takes Ailish’s hand, squeezing it and I give her a slight smile.

“I lost my virginity with a childhood friend at my grandfather’s wake when I was sixteen. I’ve always felt guilty about it, and my subconscious drags it up when I sleep.”

There’s a moment’s hesitation before Hanna and I start cackling.

“Guyssss, it’s bad,” Ailish groans before she gives in, and we’re all holding each other, laughing for the rest of the tram ride.

We’re off the tram and need to pee.

“Behind the garage bins?” Ailish suggests. Hanna leads the way and we’re all squatting, our streams echoing against the concrete. Someone’s looking over the balcony, but we just keep going.

“Verpiss dich!” Time to go. We run off giggling, high off our transgression, and I know I’ll remember those garage bins, that tram ride and these streets.

33.

Art by Brandon Sung

Art by Jocelyn Wong

Is a Door Just a Door?

Hannah Bailey

A door is not just a door. It is more. It will always be cursed by the haze of your childhood. The door isn’t just a door; it’s your front door. Its hinges hide and hold your family’s secrets. The golden doorknob isn’t just a doorknob - it is the thing that gleamed gleefully at you while you figured out you had lost your keys and watched as you waited impatiently for your parents. The light in your kitchen is not just a light. It lit the first floor of your house while you dutifully studied and when you snuck down to eat more ice cream. It was a friend, really. An accomplice.

But are the people just people? Are your parents just your parents? No. They were kids first. We know their stories, their loves and their fights. But is that all they are - the sum of their lives after us? Maybe all they are is kids clawing through litres of adult blood and distrust and regret. There is a story somewhere of this heavy blood and distrust and regret. It will rain on you, painting your face red, filling your nostrils and ears until you cannot see it. Until you cannot see real life. Until you can only see this story. You know this story, and you are scared. It is an itch you cautiously beg your mother to scratch. Call me home again, Mum, you want to say and think of the yellow grass and the blue sky. You know it, and this story feels like the time you asked for one last chocolate Froggo and then slammed your finger in a door. And you can’t even remember the order of events or if they happened on different days. All you can remember is the fat tears and how much it hurt. It feels distant, like all memories, but you remember it as a brown-hurt. Not a red-hurt or an urgent hurt, but a hurt digging deep into your gut. You think of it, and you think of your teeth smashing ceramic steps and your toes curl.

Everything is distant now. There is no haze, only blood. That haze was just a trick of the mind; all those memories are only in your head. You want it all back, but all you can think of is that story, a burgeoning prophecy. It has ruined that haze, left it dead. It is gone.

Sometimes, you check.

You know it is gone, but you want it back. You see it, staring depleted in the kitchen. The light is just a light. The front door is just a door. The golden door knob is just a door knob. Your parents, just children.

It is all gone. This is a story you have known for generations.

34.

35.

Art by Jasmin Small

Via Fernando Santi, 5 Margherita Dall’Occo-Vaccaro

I am three, and you are everywhere. You are packed in boxes stacked high through the cold, dark journey. You await a place on the mantle, a spot in the lounge, a space among ferns. You are red among the green, with too many synonyms and a difficult name to spell. We are oceans apart, but I can’t get rid of you. I stumble over words, over people, over our letterbox. I write to you, sing to you, and scream at the thought of having you at the tip of my tongue.

I am seven, and you are a friend. You are pasta lunches and waiting for the postman at Christmas. Our hearts wrap around the earth to see you again. This time, you are cannoli and summer, a wedding and young, young faces. You are adult comments about adolescent changes, the wrong church and only maybe the right person. I get pasta sauce all over my dress but it’s okay because I’m here with you. I hear you in tongues, laughs and cries that suffocate me.

I am 10, 11, 12 and you are a teacher. I am away for months at a time, always anxious and waiting. I unpack luggage and finally put it away in drawers, and see you in summer, again. This time, we are alone. I’m not quite sure why I don’t know or why I’ve forgotten. I am reading again, purposely feeling the meaning of every word, and all I want to do is listen to you whisper in my ear.

I am 15, and you are a stranger. You are broken glass and graffiti, history ruined by chance.

Nothing looks right, but everything looks familiar, similar, and known. The mountains remind me of my nose, my fathers’ nose. I only remember last night, and not the night before but maybe what I had for breakfast. I count 11 stars, two pearl necklaces, and a box full of plastic. We are together, but a man has grown wings and thrown himself over the bridge. He finally took off his shoes, his leg and walked around in his brain. Christmas is red, but I’m not sure I can see past his oak-coloured eyes. I am fifteen, and you are yelling across the corridor, through doors, down throats, past souls. I am fifteen and I hate you.

I am 19, and I’ve found you again. I feel you in gravestones, in a new black wardrobe, in tongues, cries, laughter and long dining tables. I love you from an arm’s length, from the back of the tram, from the orthodontist’s office and plates of pasta and honey wine. I love you from farmers’ lands and lost best friends.

36.

I am 20, and the bunk bed is too small for me, even if I swear I haven’t grown since I was 15. I eat everything and nothing all at once, I walk and walk and walk, and when I run, I trip and sprain my ankle. I am 20, and you are still yelling across the corridor, through doors, down throats, past souls. This time, you are questions, unwrapped gifts and blue fondant left behind on a lavender plate. Swaddles and pesto pasta mash replaced by onesie pajamas and red sauce; you are almost taller than me. I am 20, and suddenly, I am an aunty, a cousin, and a daughter, hoping I am good enough to support the weight of the world. I am glue and steel beams.

I am 21, and you perpetually live in my house. The coffee machine is always humming, and the walls smell of sweat, sunscreen and smog. My ashtray always needs emptying and the fridge never needs filling. I am without you but I am warm olive skin and espresso cups, a sun clock left behind, and shoes at the door. I have never been happier to stumble over sentences, laugh at my mistakes and have to translate.

I will be 22, and you will be infinite; I will move my body through walls and maps and ceilings with ease. I will write to you, in laughter, in tears, in scribbled messages on the inside of books, in curly handwriting I am yet to figure out, in shoes, in gold. In lost looks and missed phone calls, I will always find my way home to you.

37.

Art by Vera Tan

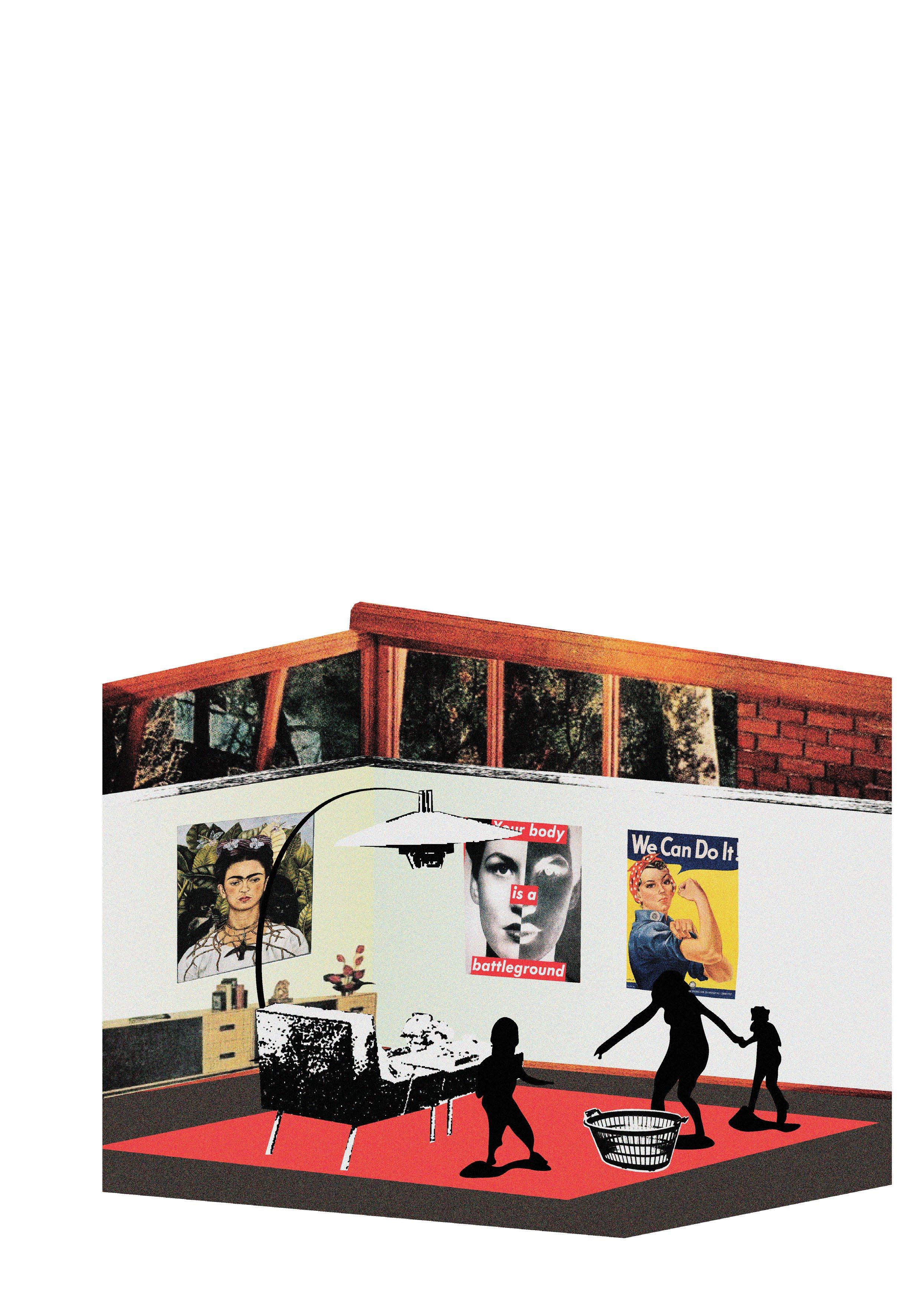

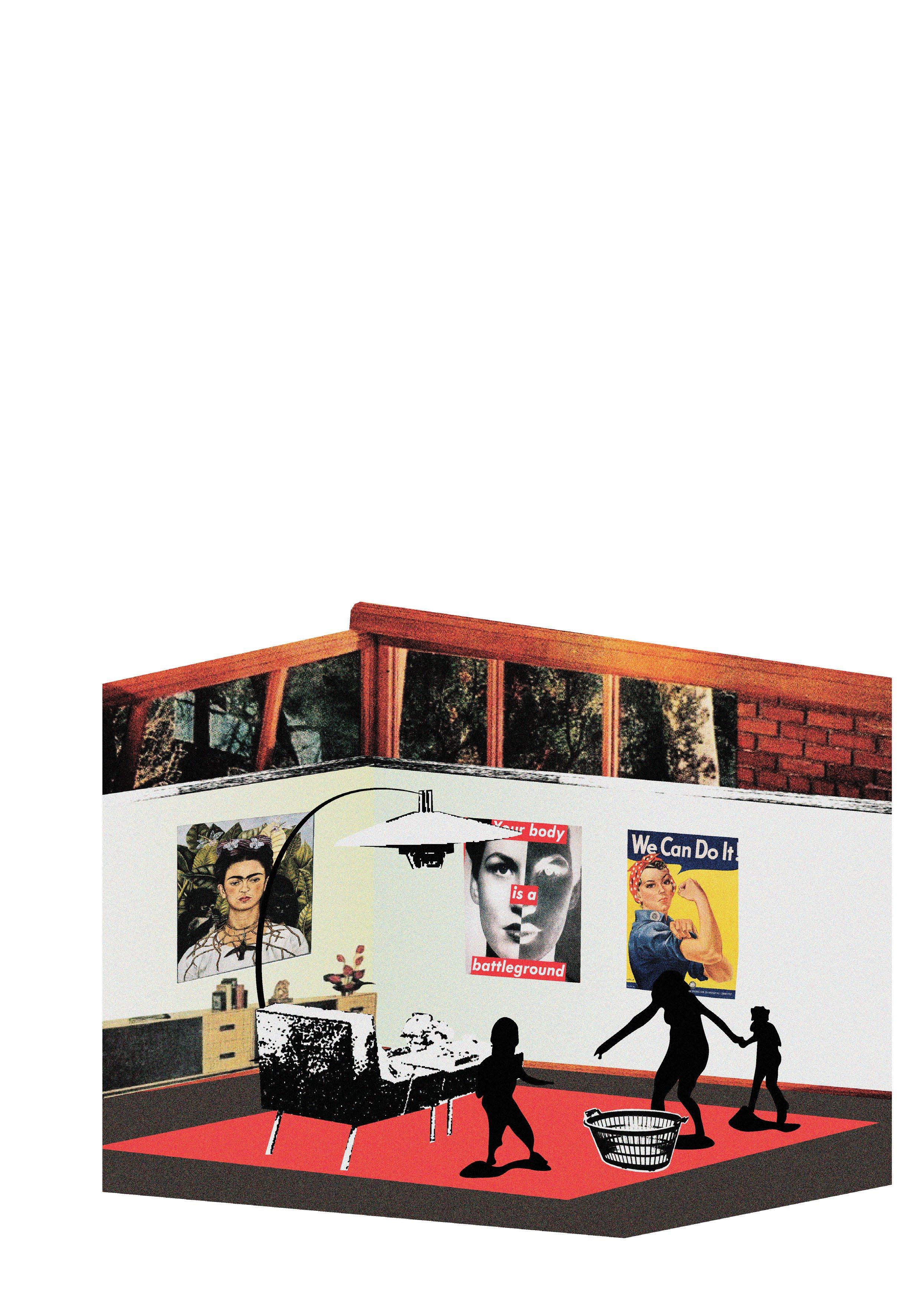

Love’s Labour’s Lost Labour

On money, marriage and Marx

Jaden Ogwayo

The gendered imbalance of domestic duties in heterosexual couples is well-documented, and, due to the androcentrism of marriage and spousal culture, the allocation of domestic labour tends to favour the working (read: earning) husband at the expense of the (house-)wife. Despite men’s gradual decentering as the key earners in heterosexual partnerships in the last seventy years or so, domestic labour inequality often persists even in households which are comprised of two joint breadwinners. These partnerships where each spouse brings home the same dollars — brings home the same bread, if you will — often see the wife bearing the unremunerated role of unpacking, baking, shelving, storing, and apportioning said ‘loaf’, in addition to undertaking the responsibility of feeding and training the future breadwinners she raises within the home. As theorists of reproductive labour will tell you, a wife’s care of her breadwinners — both her husband (i.e., actual earner) and her children-soon-to-be-workers (i.e., future earners) — plays a significant, yet unrecognised (and unpaid), economic role in leavening the ‘dough’ of a nation by reproducing labour-power.

Any Marxist (Neo-, Post-, Classical, take your pick) can — and will! — tell you that the psychically detrimental consequences of entrenched labour and pay inequalities are numerous: alienation, commodity fetishism, enslavement to capital, etc. However, the specific figure of the housewife is too-often neglected in Marxist/socialist critique of labour relations that do not explicitly announce themselves to be ‘feminist’. The housewife is frequently absent from standard historicisations of work that track labour conditions’ transition (within workplaces) from feudal serfdom on the fields, to industrial automation within factories, to neoliberal ‘free’ employment under late-stage capitalism. We often track the dialectics of the worker in his workplace by scrutinising how the proletarian is subjectivated by his bourgeois employer to serve his workplace. But seldom do we offer the proletarienne the same analysis when considering how she is conditioned to serve the husband and his home — how she and her workplace/house similarly function as extensions of his property!

I implore any thinker who situates themselves to the political left to imbibe some gender theory and, when critiquing capitalism’s power relations and exploitative discursive practices, consider the housewife who sustains the economic base from the margins of the superstructure. Despite her absence, let us interrogate the conditions of unwaged housewives inextricably bound to legally, formally, and contractually employed husbands who receive salaries while they receive… a new surname? Our debates about “workers’ rights”, “employment law”, and “workplace fairness” ought to make room for one of the most overworked and underpaid — unpaid! — workers of the nation: the housewife.

38.

She is intractably clocked into endless domicile shifts but never explicitly financially compensated for her labour. Most of us have coworkers to complain to, but for the housewife, how might she as a lone worker feel? Good, bad, how would we ever know? Resentful as she may rightfully be about the exigencies of marriage and labour, who will hear? With whom can she unionise? In Marx’s words, who will help her “break her chains”?