CONSERVE

Planting With a Purpose

Planting With a Purpose

In this issue of Conserve, we share some of the many ways that the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy addresses environmental and community issues through the Conservancy’s tree and landscape plantings. Our planting programs are extensive, ranging from planting street trees and urban park trees in urban and neighborhood settings to tree plantings in rural areas along our rivers and streams.

Our community greening program plants trees in neighborhoods across Pittsburgh and Allegheny County, and in other communities from Erie to New Kensington to Johnstown. The tree plantings are focused to a significant extent on under-resourced communities, low-shade communities and others where the need and interest is strong. The trees sequester carbon, make our neighborhoods more attractive, walkable and transit-friendly, provide shade for residents, and spur investment. The Conservancy has planted more than 40,000 street and park trees in our cities and neighborhoods.

Our community greening staff also plant and maintain 130 gardens across the region. More than 90 of them are in Allegheny County, but the Conservancy also plants and maintains gardens in many other communities across Western Pennsylvania. The gardens, with their annuals and native perennials, are centerpieces for many communities, reinforcing the beauty of our region’s cities and the character and identity of our neighborhoods.

In places with stormwater management needs, the Conservancy’s plantings often provide natural, landscape-based stormwater solutions. Our garden at Centre and Herron in Pittsburgh’s Hill District filters more than one million gallons of stormwater annually. In communities ranging from Millvale to Point State Park, our plantings manage stormwater through swales and vegetation. Many of our plantings include pollinator plants, important at a time that so many pollinators have declining populations.

The Conservancy provides extensive plantings in Pittsburgh’s downtown. More than 1,000 planters and hanging baskets brighten city sidewalks, and we provide them in other locations such as downtown’s bridges over the Allegheny River and along South Side’s Carson Street. We change out the plantings in the downtown planters five times a year, so they are planted through all the seasons.

We also partner with Pittsburgh Public schools and early learning centers, to convert under-landscaped school grounds into beautifully landscaped settings that children can use as outside play areas and outside settings for education. The Conservancy has

(Continued on Page 20)

PRESIDENT AND CEO

Thomas D. Saunders

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Alfred Barbour

David Barensfeld

Franklin Blackstone, Jr.*

Barbara H. Bott

E. Michael Boyle

Marie Cosgrove-Davies

Beverlynn Elliott

Donna J. Fisher

Susan Fitzsimmons

OFFICERS

Debra H. Dermody Chair

Geoffrey P. Dunn Vice Chair

Thomas Kavanaugh Treasurer

Bala Kumar Secretary

Paula A. Foradora

Dan B. Frankel

Dennis Fredericks

Felix G. Fukui

Caryle R. Glosser

Carolyn Hendricks

Thomas F. Hoffman

Robert T. McDowell

Sanjeeb Manandhar

3 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20

Community Engagement Ensures Funding, Support for Greenspaces and New Trees in McKeesport

Native Plantings on WPC Preserves Attract Birds, Help Biodiversity

Volunteers Find a Happy Place Among Riparian Trees

Kids in Nature! Conservancy Continues Greening School Grounds

Major Milestone! 40,000 Trees Planted, Capturing a Million Pounds of Carbon

Greening Erie County

Eco Assessments: The “Gift that Keeps Giving”

Listen to Nature: Landscape Interns Balance Plants with Planning

Make a High-Impact Gift by Donating Appreciated Assets

The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy protects and restores exceptional places to provide our region with clean waters and healthy forests, wildlife and natural areas for the benefit of present and future generations. To date, the Conservancy has permanently protected more than 290,000 acres of natural lands. The Conservancy also creates green spaces and gardens, contributing to the vitality of our cities and towns, and preserves Fallingwater, a symbol of people living in harmony with nature.

Paul J. Mooney

Daniel S. Nydick

Stephen G. Robinson

Samuel H. Smith

Alexander C. Speyer III

K. William Stout

Megan Turnbull

Joshua C. Whetzel III

Gina Winstead

*Emeritus Director

For information on WPC & Fallingwater membership: 412-288-2777 | Toll Free: 1-866-564-6972 info@paconserve.org WaterLandLife.org | Fallingwater.org

There isn’t a day that goes by that Tom Maglicco doesn’t think about big issues facing the City of McKeesport. As the city administrator, chief of staff to the mayor, and parks and recreation director, Tom’s plate is usually full helping to address a variety of issues from economic development needs to housing concerns.

He also spends a considerable amount of time thinking about quality-of-life concerns, community improvements and revitalizing blighted areas across the city. “Just like any other city, we have our challenges and complexities, but the McKeesport community is resilient and hopeful about the future. I just want to see our town prosper again,” says Tom.

Located about 15 miles from downtown Pittsburgh at the confluence of the Monongahela and Youghiogheny rivers, McKeesport is Allegheny County's second-largest city. In the early 20th century, coal mining and steel production brought economic prosperity and population growth, but those industries

declined by the1980s, leaving McKeesport and other Mon Valley communities with population losses, vacant buildings, high unemployment rates and legacy environmental impacts.

“We are not defined by our past, but rather we’re learning from it and redefining our future,” Tom adds. “But we’re so grateful to have the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy as such an important partner in our ongoing endeavors.”

About seven years ago, Tom and other city workers initiated a review of the vegetation at Renziehausen Park, a beautiful and popular 205-acre outdoor recreation complex that includes ballfields, hiking trails, pavilions, gardens, a fishing pond and a spray park for children. The park, called Renzie for short, had significant vegetation issues, including populations of invasive species, dead trees and more than 100 stumps left in the ground after tree removals.

“Why were so many trees being cut down or dying and are we planting to replace them?” Tom recalls asking himself and others before requesting the Conservancy’s help to undertake a comprehensive review and assessment of McKeesport’s public tree canopy.

capture nearly 12,000 pounds of carbon dioxide (CO2) annually, and are storing nearly 3.4 million pounds of the atmosphericaltering gas.

Not only did the tree assessment identify locations for new tree plantings, data collection, hydrological analyses and site evaluations were also done to identify locations for new green infrastructure projects, such as bioswales and rain gardens, that will help slow stormwater runoff, decrease pollution entering streams and reduce the risk of flooding.

Communities are often required to address these water quality and stormwater management issues, but with few resources to do so. Filled with native pollinator-friendly plants, moist-soil loving trees and wild grasses, bioswales and rain gardens are effective environmentally-friendly alternatives to installing new gutters and pipes.

“When you bring different people, perspectives and ideas to the table, the community can work together to overcome barriers and make meaningful progress towards creating a greener, healthier neighborhood."

— Dr. Jamil Bey of the UrbanKind Institute

In fall 2021, Conservancy staff, including Brian Crooks, an International Society of Arboriculturecertified arborist, and Community Forestry Project Manager Alicia Wehrle, initiated a tree inventory that assessed and inventoried the number and quality of McKeesport’s street trees and those located in community parks, including at Renzie. In total, 1,421 trees were inventoried, with 902 located within parks and 519 along municipal streets in the public right of way. Together, these trees

In the face of climate change, tree planting and green infrastructure projects are essential to reduce the risk of flooding and improve water quality. These initiatives not only help combat climate change, they also have other benefits for the community such as providing shade, cleaner air and habitat for wildlife, as well as improving the overall aesthetics of the community.

Since 2022, more than 800 trees have been planted in McKeesport, 540 of which are in Renzie Park. With TreeVitalize Pittsburgh funding, more trees will be planted across the city.

“Our optimism about future plans for tree plantings and green infrastructure is well-founded, and now federally supported,” says Tom, referring to a $1 million Environmental Protection

McKeesport

Forester Brian Crooks

inventory assessment.

Agency environmental justice program grant recently secured to help design and implement new programs and actions that expand and enhance current greening programs.

McKeesport is just one example of the comprehensive community greening assessments the Conservancy undertakes for cities and towns throughout Western Pennsylvania. The process helps evaluate community greening needs, engages community residents, municipal officials, partners and other professionals, and recommends greenspace improvement projects.

“We know greening work has such immense environmental, economic, social, recreational and health benefits,” says Jeffrey Bergman, senior director of community forestry & TreeVitalize Pittsburgh at the Conservancy. “With help from our dedicated community partners, future tree planting, community garden and bioswale projects are aligned directly with priorities identified by community residents and leaders through a facilitated outreach and engagement process,” he adds.

The Conservancy is partnering with Dr.

Jamil Bey of the UrbanKind Institute (and recently appointed director of Pittsburgh City Planning) to lead community outreach efforts in McKeesport. Jamil founded the institute in 2016 to help lift up the voices of over-burdened and under-resourced residents in Pittsburgh and surrounding areas with the hope to bridge a gap between community experiences, public policy, academic research, and the benefits of community greening.

“When you bring different people, perspectives and ideas to the table, the community can work together to overcome barriers and make meaningful progress towards creating a greener, healthier neighborhood,” explains Jamil, who specializes in inclusion strategies for underserved communities.

Collaborating with local organizations, businesses and government agencies, he says, also helps provide additional resources and support for tree planting and green infrastructure projects. He has coordinated three community meetings in 2023 and 2024 to listen to residents, obtain feedback and form partnerships.

“We’re leveraging existing networks in the community, and by coming together, we are breaking barriers and making meaningful progress toward creating a greener, healthier McKeesport,” Jamil adds.

Thanks to a grant from the Mary Hillman Jennings Foundation, a new school greening project is taking shape at McKeesport School District's Founders’ Hall Middle School, where students, teachers and Conservancy staff are working together to plan a natural outdoor classroom and play area. Stepping stones, benches, a stage and other playful and educational elements are adjacent to native plants and shrubs—all available for young learners to explore and discover. Outdoor learning and play foster imagination and a connection to nature, and, we hope, future conservationists!

Nearby, at O’Neil Boulevard and Hartman Street, a Pennsylvania American Water-sponsored community flower garden is filled with hundreds of colorful flowers, including zinnias, pansies and brown-eyed Susans that attract pollinators and other wildlife. Garden sponsors make it possible for the Conservancy to purchase the flowers, mulch, tools and other materials, as well as coordinate the exceptional network of volunteers, to help keep local communities blooming with natural color.

Pre-K students in McKeesport have a new natural outdoor play space, thanks to the Mary Hillman Jennings Foundation.

Waterfowl and birders alike are already benefitting from a wetland restoration project across 89 acres of the Conservancy’s 552-acre Helen B. Katz Natural Area in Crawford County that was completed in 2023.

Wetlands are areas of land that are saturated with water or covered by water, and home to a diverse array of plant and animal species, many of which are specialized and reliant on these unique habitats for their survival.

In addition to supporting biodiversity, wetlands play a crucial role in mitigating the impacts of climate change, because they store large amounts of carbon that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere.

The restoration project restored former agricultural fields to their original ecology and reestablished water flows within the floodplain forest along Cussewago Creek, a tributary to French Creek. Part of the restoration project involved controlling and reducing invasive plants, and planting native vegetation. Native plants are

adapted to the local climate and soil conditions, making them more resilient and better suited to thrive in wetland habitats.

One such wetland plant is the common cattail (Typha latifolia), a tall, reed-like plant native to Pennsylvania that thrives in marshy areas. Native cattails provide important habitat for birds, insects and amphibians, and help stabilize soils and filter water. However, don’t confuse it with the narrow-leaved cattail (Typha angustifolia), a quick-spreading invasive that can devastate wetland ecosystems and the seeds of which can remain viable in the soil for up to 100 years.

Two other common wetland plants are the marsh marigold (Caltha palustris), with its bright yellow flowers that bloom in the spring, and the swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), a favorite of butterflies and other pollinators. These plants, along with many others, play vital roles in the wetland ecosystem, contributing to its overall health and providing cover and nesting sites for waterfowl and other wildlife.

Bird Atlas, an effort to understand the distribution, abundance, long-term change and seasonal patterns of birds breeding in a specific region. Volunteer birders are asked to record observations to help track and better understand Pennsylvania's bird populations. Within the restored wetland, they saw an elusive Virginia rail, which are common but more often heard than seen.

“What a great place Katz is for wildlife,” John notes. “It is gratifying to see that WPC’s efforts to restore natural hydrology and vegetation in what were once drained farm fields is already benefitting wildlife.”

“By protecting and conserving these valuable habitats, we can help safeguard biodiversity, mitigate climate change, and maintain the health of our planet for future generations. We’re already seeing some of the benefits of these plantings that can only get better over time.”

— Andy Zadnik, Conservancy Senior Director of Land Stewardship

In addition to the wetland work, riparian trees were recently planted—thanks to help from the Crawford County Conservation District, PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources and local high school students—along an unnamed tributary of Cussewago Creek that runs through the preserve. Also, Conservancy staff planted about an acre of native wildflowers, using a mix that includes native grasses and flower species.

Local conservationists and Conservancy members John Tautin and his wife, Joan Galli, visited the preserve this spring as part of the PA Game Commission’s Breeding

Recent restoration work at other Conservancy-owned preserves includes the planting of 185 trees at Toms Run Nature Reserve with the help of volunteers as part of the Allegheny Bird Conservation Alliance, and planting wildflowers at Sideling Hill Creek Conservation Area in Bedford County. Conservancy Board Member Carolyn Hendricks and her husband, Steve, helped with the site preparation and are assisting with stewarding efforts; they will be on the lookout for bees, butterflies and hummingbirds soon.

Conservancy Senior Director of Land Stewardship Andy Zadnik says these are good examples of planting native plants with the purpose of preserving natural ecosystems and supporting native species.

“By protecting and conserving these valuable habitats, we can help safeguard biodiversity, mitigate climate change, and maintain the health of our planet for future generations,” he adds. “We’re already seeing some of the benefits of these plantings that can only get better over time.”

Planting and stewarding riparian areas, such as this one in Clearfield County, help to restore lands including old mining land, retired livestock pastures and eroding streambanks.

Catching crayfish in Brady’s Run, examining streamside plants and harvesting tomatoes from her Beaver County garden…these things make 12-year-old Sophie Tripp smile.

So when the self-proclaimed botanistto-be spent a spring day volunteering with her dad, Jeff Tripp, to plant and care for trees near streams with the Conservancy’s watershed conservation team, she gave the experience two green thumbs up.

As they crossed the muddy Ohio River en route to the planting, Jeff, an engineer who writes riparian (streamside) restoration and erosion control plans as part of his job, explained to Sophie how tributaries can contribute to silt runoff in rivers.

“We discussed the importance of addressing stream quality in the upper reaches of the watershed,” Jeff says, “and addressing smaller issues before they become larger.” They talked about how trees planted in riparian areas near streams help prevent excessive silt runoff and streambank erosion, and cool the water, all of which improve water quality for fish and other aquatic wildlife. The trees provide shelter and food for other wildlife.

“At the planting, we got to walk around first and then plant whichever trees or shrubs we wanted,” Sophie says. “We put nets over the trees to keep birds out of the cylinder that goes around the tree.” The tube and net keep animals from nesting in, eating or rubbing the tree.

Sophie and Jeff learned that regular visits and follow-up care for young riparian trees is crucial and improves success rates— so much so that WPC Watershed Riparian Coordinator Monica Lee is recruiting riparian steward volunteers in six counties to check on some of the roughly 8,000 riparian trees planted by WPC’s watershed conservation staff and volunteers annually. “We’re improving water quality and wildlife habitat while increasing biodiversity,” Monica says.

Riparian steward volunteers adopt a site, visiting on their own schedule for about one hour monthly. They typically hike approximately one mile to the site. “If

someone has some mobility limitations but can comfortably hike, I’ll match a site with little to no terrain if there is one located in their preferred area,” she notes.

“The volunteers check trees and ensure the tree tube, stake and tree are straight and sturdy, and do some light weeding within the tree tubes,” she says. “Are the trees alive? Are the birds safe?”

Once the trees reach a certain age, volunteers remove the bird nets. They request supplies, update Monica on trees’ health and report any detrimental events, such as a damaging flood.

Sophie is happy to make a difference. “Rather than just think ‘Oh no!,’ it’s better to help,” she says, adding of the planting day, “It felt like other people also cared, just like I care about the stream and plants.”

Contact Monica Lee at 724-471-7202 ext. 5111 or mlee@paconserve.org to become a riparian steward in Blair, Butler, Clearfield, Huntingdon, Westmoreland or Venango counties, or to plant riparian trees during fall or spring.

Birdhouses, Eastern redbud trees, tree stump tables and seats, black-eyed Susans, artful mosaics, milkweed and stepping stone trails are all among the playful and natural features nurturing creativity and stimulating curiosity for hundreds of young learners in our region. That’s thanks to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy’s work since 2007 to transform hard blacktop parking lots or grass-only spaces into outdoor classrooms and play spaces that facilitate hands-on, nature-based learning. Research shows that time spent outdoors in a safe, engaging and natural setting has a wide range of benefits for children,

including creativity, imagination, problem-solving, discovery, observation, experimentation and social interaction. To date, 57 high schools and elementary schools and 11 early childhood centers in the Pittsburgh area have received green enhancements. We've also advanced greening projects at six other schools in the region.

Initial funding for the program was made possible through the Grable Foundation and the Richard King Mellon Foundation. Since 2012, the Conservancy has partnered with the PNC Foundation to add natural play spaces at Pittsburgh Public Schools through the foundation’s Grow Up Great initiative. For each of those projects, Conservancy staff worked with PPS facilities and early childhood administrators to select locations and create

At PPS West Liberty PreK-5, a grass-only lot was transformed into a space where students can explore nature among native plantings.

Outdoor play areas provide safe places for children to play and encourage motor skill development, nurture creativity and stimulate curiosity.

outdoor spaces that are based on curriculum needs.

In celebration of PNC Grow Up Great’s 20th anniversary, the foundation is providing additional support for another outdoor classroom and green play area, and assisting Conservancy staff in evaluating and improving the infrastructure at the 12 previously installed sites.

“The Conservancy is grateful for funding support from local foundations, which has greatly helped establish and expand our school ground greening efforts to early childhood centers, providing young children with fun and educational activities in natural surroundings,” says Julie Holmes, the Conservancy’s senior director of development.

Volunteers pose after planting several trees in Pittsburgh’s Beltzhoover community.

Arainy spring morning in downtown Sharpsburg, Pa., with the smell of freshly turned soil, mulch and dew lingering in the air, was the perfect setting for the Conservancy to celebrate an important milestone.

At the April 19 celebration, attended by community leaders, volunteers and state and county representatives, Conservancy staff planted a tree to commemorate the 40,000 trees planted by the Conservancy’s community forestry programs, including TreeVitalize Pittsburgh and the Pittsburgh Redbud Project.

districts and parks in 73 City of Pittsburgh neighborhoods and 57 municipalities in the region with the help of more than 17,000 community volunteers.

Trees offer a multitude of benefits to urban and rural communities, including controlling stormwater runoff, cooling neighborhoods, increasing property values, increasing economic activity in business districts, and reducing airborne pollutioninduced health issues such as asthma.

A tree’s ability to improve air quality and absorb carbon dioxide and other pollutants, while releasing oxygen into the atmosphere,

Since 2008, the Conservancy has been undertaking community forestry work with several partners in many communities throughout Southwestern Pennsylvania, with priority given to low-income and under-resourced communities.

Many native tree species, such as Eastern redbud, sweetbay magnolia, hornbeam, red maples and red oaks, have been planted across Western Pennsylvania to increase tree canopy and diversity, and maximize the many benefits they provide.

These 40,000 trees have been planted along streets and trails and in business

being of urban communities. Research has shown that access to green spaces, such as parks with trees, can reduce stress, improve mood and enhance overall mental health.

Along with our state and local partners, the Conservancy will continue planting trees with a priority of increasing the tree canopy in under-resourced communities with low tree canopy in the region. Statistically, these communities tend to have disproportionate exposure to environmental pollution.

“We could not have accomplished planting 40,000 trees without the help,

is unmatched. This process not only cleans the air but helps combat climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. With one mature tree absorbing more than 48 pounds of carbon dioxide each year, the Conservancy’s 40,000 trees are estimated to be capturing approximately one million pounds annually. Trees also contribute to biodiversity by providing habitats for various species of birds, insects and other wildlife.

In addition to their environmental benefits, trees in parks also have a positive impact on the mental and physical well-

support and dedication of our community volunteers and partners,” says Jeffrey Bergman, senior director of community forestry and TreeVitalize Pittsburgh at the Conservancy. “This is momentous. Trees truly are invaluable for so many reasons. As stewards of this planet, we have to act now to plant and care for trees to create a healthier and more sustainable Western Pennsylvania for everyone,” he adds.

With 1,558 square miles of land nearly flattened by glaciers that formed lakes in Pennsylvania’s northwesternmost corner, Erie County offers unique opportunities for exploring nature and studying diverse plants and wildlife. WPC has a long history of conservation there: We’ve protected land to help establish Erie Bluffs State Park, protected acreage for State Game Lands 109 and 314, and established 10 nature preserves, including Lake Pleasant Conservation Area and Bentley Run Wetlands. Read on to discover some of the Conservancy’s recent greening efforts in Erie County.

It’s a hot afternoon and WPC volunteer garden steward Tom Chandley is sitting on his boat at a Lake Erie marina, waiting out a downpour. He’s not disappointed about the interruption to his nautical adventures. “The garden could use an inch of rain,” he muses.

That thirsty garden is WPC’s community flower garden in Erie County, located at East 6th Street and East Avenue in downtown Erie. “It’s a nice place to highlight the entrance to Erie’s East Side,” Tom says of the colorful oasis that he has stewarded since 2013.

The site was an unremarkable brown dirt smudge on a concrete sea until the Conservancy installed the garden in 2000. Traditionally planted with annual flowers, this fall the garden is receiving an update featuring native perennials including switchgrass, winterberry and fragrant sumac, thanks to grant funding from KeyBank and Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.

Tom believes the sweat equity invested to remove invasive daylilies in preparation for the perennial planting is worthwhile. “You can stage perennials to get three seasons of bloom,” he says. “They’re great for the pollinators, and plants that stay green all year make good roosting places for birds.”

Before: Without trees to shade it, Elk Creek’s waters can warm and algae can form, creating unhealthy conditions for aquatic wildlife.

After: Volunteers helped to plant 100 native trees on a half-acre at WPC's Lower Elk Creek Nature Reserve. This riparian buffer will create canopy closure, or shade, for the stream.

Beeps from appreciative commuters motivate Tom when his back aches or the mercury rises. Greening the neighborhood “upgrades our identity,” he says. “It’s like putting a mural on a wall to brighten an area and this garden does the same.”

Just blocks away, WPC is growing downtown Erie’s urban forest by a few dozen trees a year. As the canopy grows, streets cool and homes gain curb appeal. Birds and small wildlife nest and find food in the sturdy branches.

In 2013, the Conservancy inventoried trees on 70 city blocks, identifying the benefits and conditions of existing trees. Working with private funders, Erie Downtown Partnership, city and county officials and Gannon University, the Conservancy developed a plan to improve Erie’s tree canopy. “Part of the plan focuses on encouraging community involvement to manage an urban forest,” says WPC Community Greening Services Manager Marah Fielden. Since then, WPC has planted 320 street trees in Erie, such as red maple, hawthorne, hophornbeam and Eastern redbud. “The trees that existed in downtown Erie 11 years ago were providing $85,000 annually in benefits, including stormwater management, energy

savings and air quality improvement,” Marah says. “As the urban forest grows, those benefits increase.”

The trees are planted with the help of community volunteers, including Gannon University students, who plant on their Day of Giving in April. Quality of life improves with communities greening, Marah notes. “Community leaders, residents and volunteers can engage and collaborate on greening projects that spur community and economic revitalization.”

A half hour’s drive southeast of Erie, the rural community of Union City has undergone a slightly smaller but no-less impactful “tree-vitalization.” In 2019, Union City contacted WPC for help getting street trees, says Union City Borough Manager Cindy Wells. “During preparation of a Historic Preservation Plan, the public expressed a desire for more trees and greenery in the historic commercial district.” Although the pandemic thwarted a large volunteer planting effort, WPC staff planted 12 trees on Main Street in 2020 and have returned to help prune and mulch the trees and educate volunteers on tree care. Cindy notes, “The trees have definitely helped to ‘soften’ the hard concrete appearance.”

Along Elk Creek, a 30-mile tributary to Lake Erie and popular destination for paddling and steelhead fishing, miles of forested buffer provide habitat for bald eagles, herons and many other birds and animals. Lower Elk Creek hosts wetlands and diverse wildlife, including river otters.

For years, sedimentation and pollutants from the eroding streambank entered Elk Creek, decreasing water quality and causing safety hazards to anglers and other outdoor enthusiasts. In 2022, after 10 years of planning and fundraising, WPC’s watershed conservation team installed a 600-foot stone wall to stabilize an eroding streambank on Elk Creek within WPC’s 92-acre Lower Elk Creek Nature Reserve. They also installed eight in-stream weirs,

a classroom and stare at a white board while a professor talks. But students in Chris Dempsey’s Gannon University limnology class can hop into canoes, paddle onto the glacier-formed Lake Pleasant and scoop water samples while great blue herons skim the surface.

The students access the lake via the Conservancy’s 581-acre Lake Pleasant Conservation Area, says Chris, director of Gannon’s Freshwater and Marine Biology Program. Established in 1990, the preserve features old fields, forests and diverse wetlands, and includes approximately 70 percent of the shoreline around Lake Pleasant, considered the region’s highest quality glacial lake.

which are small barriers built partway into the stream that slightly redirect water flow. The project helps to prevent erosion, ultimately improving water quality.

In 2023, staff and 14 volunteers planted 800 live stakes of trees to further stabilize the streambanks and enhance habitat. Live stakes are tree branches cut while the trees are dormant, then planted directly in the soil. They grow into new trees that help stabilize the streambank and filter pollutants from entering the stream.

The “cherry on the cake,” says WPC Watershed Project Manager Alysha Trexler, was a half-acre planting of 100 native trees and shrubs, including sycamore, hickory, nannyberry and elderberry near the stream.

“The goal is to have canopy closure, or shade, for the stream,” she says. “Shade keeps the tributaries that flow into Elk Creek cooler, which is better for the terrestrial and aquatic wildlife, and helps to control algae growth.”

Some students studying ecosystems of inland waters can only sit in

Whereas Lake Erie’s size can be daunting, at the much smaller Lake Pleasant “students can grasp concepts much quicker,” Chris says. “They can see everything in action.”

Invasive water milfoil and other aquatic invasive species threaten the lake, says Tyson Johnston, WPC land stewardship manager. “Our natural heritage staff helps us monitor that, and treat for invasive narrow and broadleaf cattail in the lake and surrounding wetlands.”

Students soon can continue lessons learned on the water at an ADA-accessible open-air pavilion being built this fall near the canoe launch on the lake’s west shore. On the east shore, a 50-seat pavilion, driveway and ADA parking spaces will be built. Both will be available for public use.

The improvements are funded in part from the Conservancy’s “41 Places” fundraising campaign, which since 2021 has raised $657,500 for improvements to WPC’s preserves.

Perhaps the most impactful improvement to Lake Pleasant Conservation Area will be the reforestation in 2025 of 130 acres of old gravel mine lands. “Tree regeneration is stunted because the land was so compacted by gravel mining,” Tyson explains. “A contractor is loosening the soil to make it more inviting for the thousands of trees that will be planted next spring.” Planting trees on almost 20 percent of the preserve will improve soil conditions, water quality in the lake and wildlife habitat, he says, adding, “The ultimate goal is carbon sequestration.”

At WPC’s 1,000-acre West Branch French Creek Conservation Area, a new canoe access site with parking and signage at the Page Road bridge, funded by WPC’s Canoe Access Development Fund and another private donor, invite people to get on the water. 41Places funds were used to resurface three parking areas and install signage at the preserve.

“Seeing The Unseen: Aquatic Invaders & What’s at Stake,” about invasive species in the Great Lakes watershed and beyond.

In Allegheny County’s South Park near the old fairgrounds at Corrigan Drive, what was once an aged asphalt lot that contributed to runoff into Catfish Run is now a place worth celebrating.

More than 90 trees shade the parking spaces and drive aisles, which are made of permeable pavers that allow water to pass through into the soil, decreasing runoff. Two rain gardens featuring more than 20,000 mostly native plants filter pollutants and feed pollinating insects. Walkers chat as they stroll a tree-lined promenade and joggers circle the track below. A pollinator-friendly riparian area along Catfish Run was installed with the help of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy’s community greening staff.

The environmentally friendly oasis, which won a Governor’s Award for Environmental Excellence, was inspired by an ecological assessment and action plan completed in 2017 by Western Pennsylvania Conservancy staff. It’s one of eight such plans WPC has completed or is completing in partnership with Allegheny County Parks Foundation (ACPF) and the Allegheny County Parks Department (ACPD); a ninth assessment is

canopy gaps and

pollinator-friendly

pending until funds are raised.

A decade ago, then-ACPF Executive Director Caren Glotfelty shared her vision with the Conservancy to conduct an eco plan at Boyce Park. In 2015, WPC community forestry and natural heritage program staff began to evaluate natural resources and ecological assets of all Allegheny County parks, beginning with Boyce Park. The assessments provide a framework for projects that protect and improve the parks’ environmental health, says WPC Senior Director of Community Forestry Jeff Bergman. “We have a multidisciplinary team that brings GIS, forestry, green infrastructure and ecological expertise.”

Using state-of-the-art mapping, data collection techniques, surveys and field observations, WPC staff identify natural assets such as native plants, water bodies and older-growth forests. They note issues such as invasive plants, soil erosion and tree pests and diseases.

With this data in hand, WPC recommends invasive plant management, tree plantings, green infrastructure, meadow restoration and more. ACPD and ACPF have been implementing projects based on these recommendations.

“The studies point out ways we can improve the parks, get more volunteers, gain funding and build relationships with communities and corporations,” says ACPF Executive Director Joey Linn Ulrich. ACPF fundraises and provides leadership for these vital projects to improve, conserve and restore Allegheny County parks.

“Once a few studies were done, we saw patterns and could ascertain information that applies to all parks,” says ACPD Director Andy Baechle. “The eco plans will be the gift that keeps giving.”

implemented with suggestions from WPC’s eco assessments, as well as the detailed plans for each park.

At the top of the gradual uphill path leading from the house to the Visitor Center, a bench provides a spot for visitors to rest after touring Fallingwater and walking the rhododendron-lined paths of Bear Run Nature Reserve. A natural screen of plants and trees hides a nearby parking lot. The setting’s centerpiece is a moss-covered stone wall where mice scurry and robins perch to sing.

Landscape architects call this scene a vignette—an arrangement of plants and other items that create a focal point, encouraging people to stop and enjoy the space.

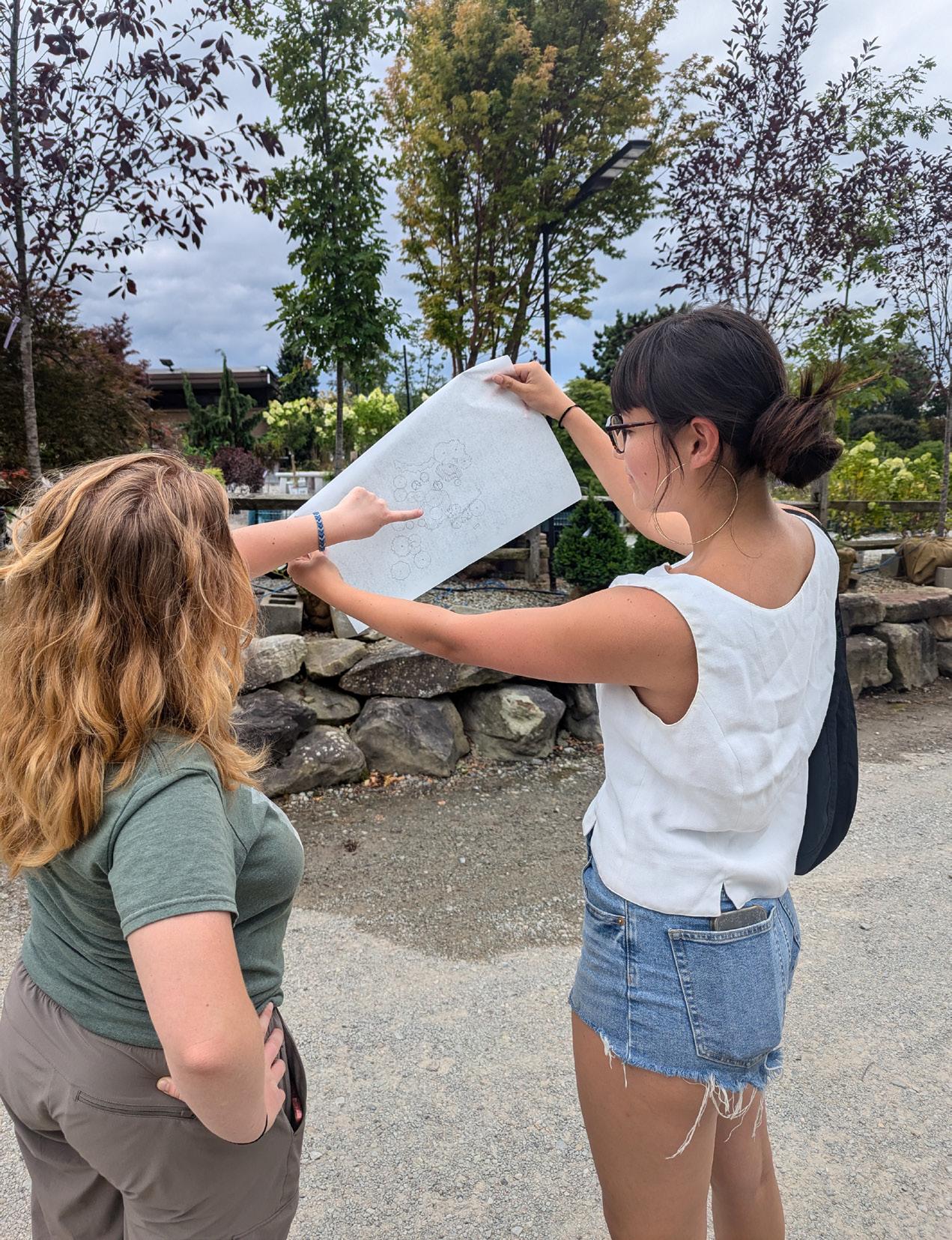

Recently reimagined and redesigned by summer 2024 Katherine Mabis McKenna Foundation

Landscape Interns Zoe Matteson and Alaira Hudson, the area exemplifies two intertwining philosophies followed by interns since the program’s inception in 1986: “Listen to what nature has to say” and “strategically integrate”—or integrate plantings without making them appear deliberate. Indeed, the approach is similar to Frank Lloyd Wright’s advice to students to “study nature, love nature, stay close to nature. It will never fail you.”

Landscape interns spend the summers working with Fallingwater Horticulturist Emily Sachs. “Last year, the interns used those guiding concepts to restore areas disturbed by infrastructure work,” says Emily. “The plans they made will inform future management of these locations.” Intern projects from past years that followed those concepts include a planted area near the Gatehouse, and a perennial garden at the Barn.

Alaira and Zoe experienced firsthand how an area can appear spontaneous yet has received careful attention, Emily notes. “They pruned rhododendrons, removed invasive species from the stone outcrop near Fallingwater, and created flower arrangements from plants found on site.”

Derek Kalp, RLA, a landscape architect at Penn State University and a 1993 Fallingwater landscape intern, just wrapped up his first summer as Fallingwater’s landscape internship advisor. He recalls the late Professor George Longenecker, the program’s previous advisor for 33 years, saying, “The plants talk to me.” At the time, Derek found it strange. “But,” he concedes with a laugh, “George was kind of a Jedi master of the landscape.”

Zoe and Alaira assembled a plant palette, consulting the book "Terrestrial and Palustrine Plant Communities of Pennsylvania" to find plants recommended for the type of forest at Fallingwater. They chose the best native plant options available at local nurseries.

wouldn’t think twice about whether it is deliberate,” he explains. “We’re working with a cultural icon, trying to stay true to Wright’s philosophy and the Kaufmanns’ approach to grounds maintenance— all while balancing with this wild, natural environment.”

The 2024 landscape interns realized that the project accentuating the stone wall would combine those lessons. “We wanted to design something people might not immediately notice,” says Alaira, a senior at West Virginia University. “The idea of the vignette helped to inform our design.”

“Stones and rock placement at Fallingwater are important and thematic,” adds Zoe, a fourth-year student at University of California— Davis. “The stone wall was the border of the old return path and part of a former intern project.” Overgrown shrubs and invasive periwinkle and stiltgrass hid the wall, while large bushes encroached on the path, requiring constant trimming.

Derek too hears nature talking, and leads interns on nature hikes to learn the plants, why they grow in a location, and how they’re changing as the climate warms.

The students must consider the visitor experience, a plant’s cultural or historical significance, and how to choose species appropriate for the mixed mesophytic forest. An unusual forest type for Pennsylvania, it features a variety of tree species that are adapted to cool, moist environments and rich soils. More difficult questions include what to do about invasive species that the Kaufmanns unknowingly introduced, and how to deal with pests, diseases such as hemlock woolly adelgid and issues caused by changing climate.

All of those considerations bridge “listening to nature” to the “strategic integration” concept, which Derek describes as “integrating plantings to achieve your goals, but doing so in a way that people

“We considered plant size and environmental requirements,” Alaira says. “We didn’t want bright, showy colors in a natural woodland setting,” but they did want a diversity of species.

Landscaping requires considerable creativity, patience and perspiration. “You need to adjust on the fly,” Derek says. “You start with a roadmap, but a lot of design happens on site. For example, you’re digging a hole and hit a boulder, so you have to move a plant.”

Volunteers helped remove invasive plants and dead trees. Stumps were pulled and holes dug. Transplanted rhododendrons now hide the view of the parking lot from the bench, groundcover has replaced overgrown bushes, and ferns, trees and native plants provide diversity.

The result is a tranquil spot where visitors can reflect on their Fallingwater experience; a vignette where people, unaware that the space was deliberately prepared to appear naturally occurring, might “listen to what nature has to say.”

note to printer:

(Continued from Page 2)

relandscaped portions of more than 80 schools and early learning centers in our region.

WPC also plants trees along the region’s streams. Our riparian plantings help restore the health of the region’s rivers and streams, shade streams in order to keep them cooler as climate increases, and replace trees where there are impacts like losses of our native hemlocks from hemlock wooly adelgid.

On our many preserves across the region, our stewardship staff manages the natural landscape in a way that supports the environment and our native species. At Fallingwater, the Conservancy blends a historic-based approach to the landscape setting with current knowledge about plant communities.

And in our natural heritage program, our work includes combatting invasive species and studying and supporting the native plant communities that are so important to the habitats of our rare and threatened species. In all our work, conservation science helps to guide what and where we plant in different types of landscapes and habitats.

We hope you enjoy this issue of Conserve. We couldn’t do any of this without the generous support of our members and such wonderful help from thousands of volunteers each year, in our gardens and tree plantings, and on our preserves.

Thomas D. Saunders PRESIDENT AND CEO

by Donating Appreciated Assets

Do you have appreciated assets such as publicly traded securities that you’ve held for more than one year? If so, you have a unique opportunity to leverage these investments to achieve an even greater impact with your charitable giving.

First, with a gift of appreciated securities, you potentially eliminate the capital gains tax you would incur if you sold the assets yourself and donated the proceeds. This may increase the amount available to WPC. Second, you may claim a fair market value charitable deduction for the tax year in which the gift is made, leading to a lower tax bill.

If you are interested in making a gift of appreciated assets, please contact Senior Director of Development Julie Holmes at 412-586-2312 or jholmes@paconserve.org