COMPLETE CORRIDORS AND THE LIVABLE, EQUITABLE CITY

Dr. Christopher Ferrell, Ph.D. Executive Director / Transportation Choices for Sustainable Communities

Paul Halajian, AIA, LEED AP Principal Architect / Paul Halajian Architects

Dr. Christopher Ferrell, Ph.D. Executive Director / Transportation Choices for Sustainable Communities

Paul Halajian, AIA, LEED AP Principal Architect / Paul Halajian Architects

How would a more livable, equitable city be organized?

Americans’ quality of life is diminished by spending inordinate amounts of time getting to the places necessary to address their basic life needs. Furthermore, our cities and suburbs are arranged in ways that make it difficult or impossible for many Americans to fulfill life needs because of their income, age, or abilities.

The Complete Corridor concept provides definition of life needs made operational for city planners, and shows how life need can be brought together along corridors with convenient access by transit, by bike, and on foot, to enhance the quality of life of inhabitants in a way that is not dependent on a person’s ability to own or operate a car.

The Complete Corridor advances the 15-Minute City and other urban development concepts by looking beyond a single walkable district, connecting multiple districts along a sustainable transportation facility to offer inhabitants a larger offering of lifeneed destinations than would be possible in all but America’s densest urban areas.

• How can livability be defined in terms of land use?

• How can land use / transportation integration promote equity?

• How can institutions, market entities, and community groups work together toward complete corridors?

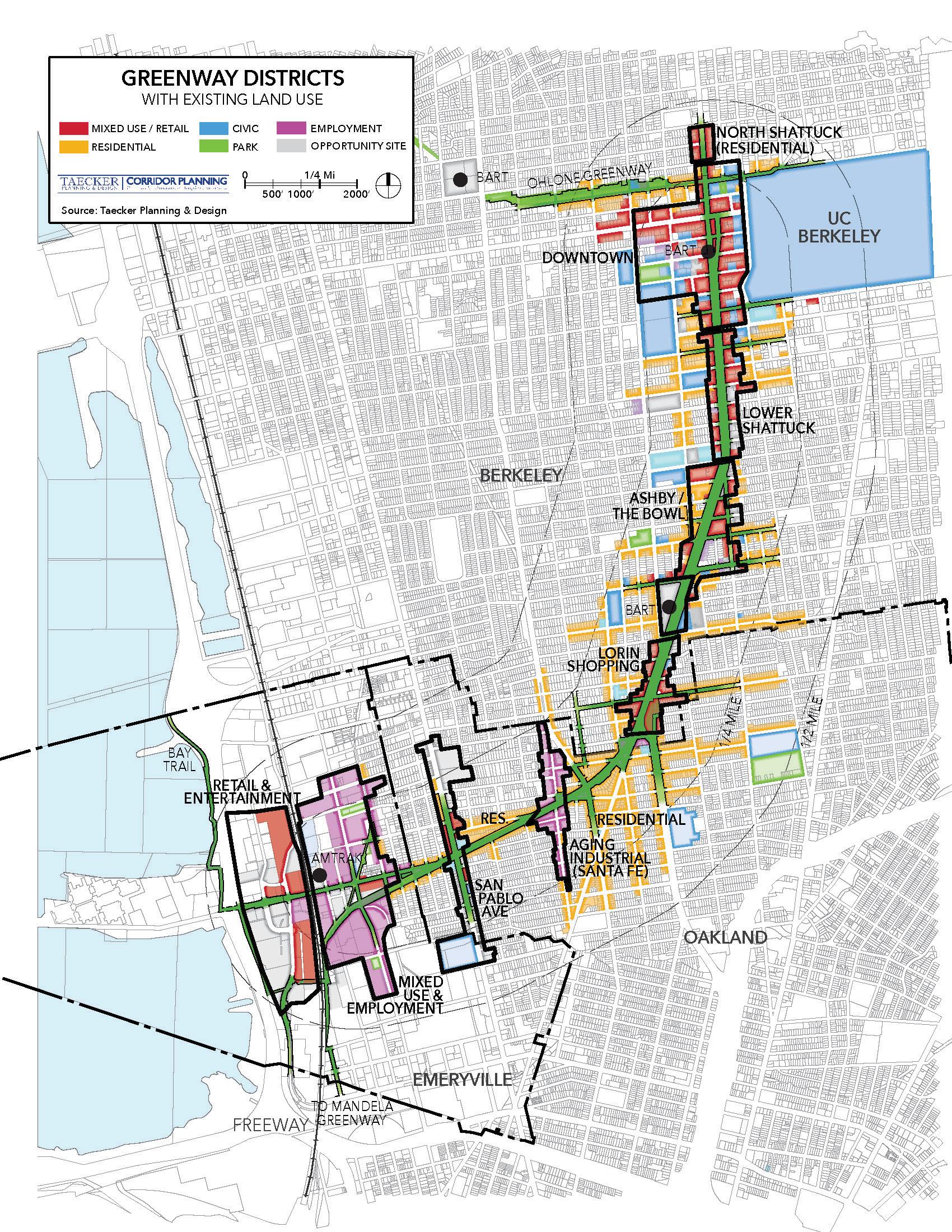

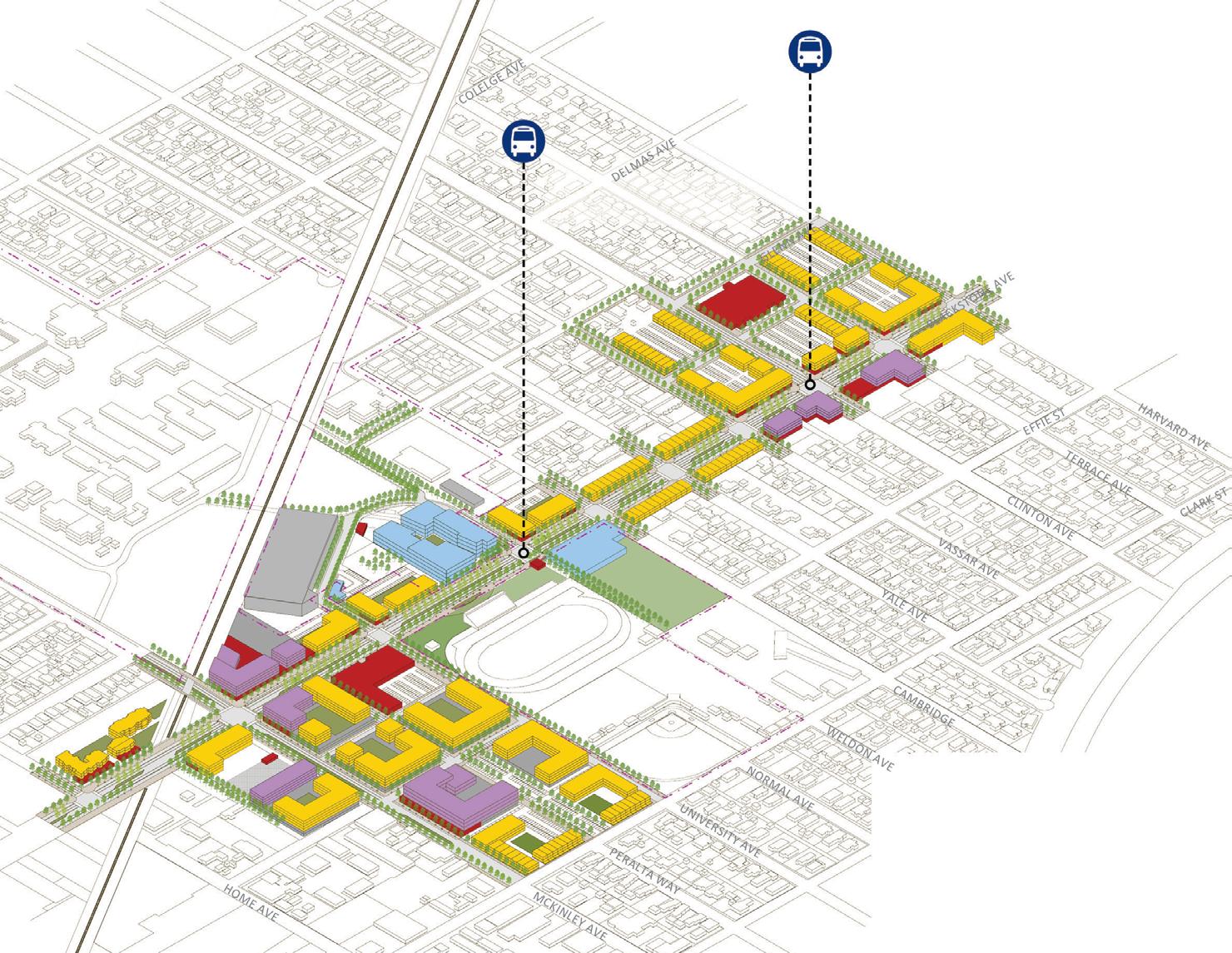

Connecting Housing and Employment. The Shattuck-Adeline-Stanford Greenway Vision Plan proposed active transportation and community improvements to replace auto-oriented roadways along wide existing rights-of-way. The 3-mile corridor is anchored at each end by commercial centers, while the center of the corridor offers abundant opportunities for infill housing development. Residents living near the center of the corridor would live less than a 10-minute bike ride from the commercial centers.

ASSOCIATE / WRT

ASSOCIATE / WRT

Matt has been a leader in placemaking, urban policy, and transit-oriented development. He authored among the nation’s first TOD guidelines. He has developed mixeduse and station area plans in diverse settings, including Berkeley’s Downtown Area Plan (California and National APA Award winner). An emeritus member of the California Planning Roundtable (CPR), Matt chaired its committee on infill development.

Since receiving his doctorate at the University of California, Berkeley, Chris has combined practical and academic experience to integrate transportation and land use systems. His research has evaluated transit-oriented development performance, examined urban interstates’ potential as multimodal corridors, and TCRP Report 187: Livable Transit Corridors: Methods, Metrics, and Strategies (the principal precursor for complete corridors).

Paul Halajian is passionate about creating a bright future for the Central Valley. A native of Fresno, Paul’s firm addresses social, economic, and environmental challenges through participatory urban design. In Fresno, Paul spearheaded the Better Blackstone Design Challenge to transform an auto-dominated commercial corridor into a multimodal mixed-use boulevard. Paul has received several awards for his community-focused work.

Livable Transit Corridors: Metrics, Methods, and Strategies / Diagram by Taecker Planning & Design

Complete Corridor Illustrated. A complete corridor offers easy affordable access to basic life needs on foot, by bicycle, or in a single transit trip. Complete corridors enhance quality of life for people who live and work along it.

Right-of-Way as Living Room. In addition to diverse land uses, Complete Corridors feature safe and welcoming environments for pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit users. Street trees and vegetation play an important role in making active transportation more attractive, by making rights-of-way more comfortable climatically and more human in scale.

Medical Care along Complete Corridors. Along Euclid Avenue in Cleveland Ohio, the City, community, and transit authority have worked to make transit access to medical care easy and affordable. Meanwhile, infill housing and employment growth along Euclid have transformed it into a complete corridor.

How would a more livable, equitable city be organized? What would it offer its inhabitants? How would it be arranged?

A more livable city offers people good access to opportunities they can use in the pursuit of improvements to their quality of life.1 People of all walks of life face challenges. While some are of our own making, many have to do with life circumstances stemming from the ways we organize our cities. Each day, Americans take 1.1 billion trips and travel almost 40 miles per person, with the average motorist driving more than 29 miles with over 55 minutes behind the wheel. While we might blame long work commutes, challenges in “getting there” are deeply ingrained in people’s lives. For example, work trips comprise only 15 percent of household trips, whereas shopping and other personal business consume nearly half of daily trips. 2 Similarly, families with children

1 Ferrell, Christopher, Bruce Appleyard, Matthew Taecker, et al, “Livable Transit Corridors: Methods, Metrics, and Strategies, Transportation Research Board, online https:// www.trb.org/Publications/Blurbs/174953.aspx , 2016.

2 https://www.bts.gov/statistical-products/ surveys/national-household-travel-surveydaily-travel-quick-facts

at home travel over twice as much on average as households without children, as precious time is stretched getting to day care, schools, and doctors’ offices.3

As people have to go farther to take care of daily needs, household car ownership and travel distances go up as well.4 In America, some 87 percent of daily trips are made in personal vehicles,5 and the car use at this level can be fairly viewed as less of a choice and more of a requirement, where the things we need are hard to get to any other way.

Granted, transit, walking, and biking are important alternatives to the car, but alternative modes offer no panacea if they can’t get you to where you can address life needs in a safe, convenient, and direct way.

3 Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), Mobility Challenges for Households in Poverty, https://nhts.ornl.gov/briefs/PovertyBrief.pdf, 2014

4 Bartholomew, Keith, and Reid Ewing. “Hedonic Price Effects of Pedestrian- and TransitOriented Development.” Journal of Planning Literature.

5 https://www.bts.gov/statistical-products/ surveys/national-household-travel-surveydaily-travel-quick-facts

The challenge of “getting there” is particularly burdensome for people who are unable to drive a car, because of income, age, or ability. An average low-income household spends nearly 40% of their budget on transportation, as needing to own, insure, and fuel a car eats into household finances, depriving families of money they could spend on other critical needs, contributing to a cycle of poverty that is difficult to escape.6

Unfortunately, most American cities are car-dependent with sprawling development patterns that make it difficult to serve by transit, let alone travel in by foot or bicycle. Car dependency also affects people on account of age and ability. In the last Census, 22% of Americans were under 18 and 18% were over 70. 26% of Americans have a disability. These people struggle to meet their basic, daily needs, living in cities optimized for the auto-affluent.

Based on these numbers, it is not an exaggeration to say that many Americans would benefit from a more balanced, affordable, and accessible urban form. Roughly half of all Americans would benefit substantively if they could access basic life needs on foot, on a bike, or in an easy transit trip. Regardless of income, many more Americans would enjoy a life in which time now spent in travel could be devoted to more personally meaningful pursuits.

6 Institute for Transportation & Development Policy, ITDP, The High Cost of Transportation in the United States, online https://www.itdp. org/2019/05/23/high-cost-transportationunited-states , March 2019.

While every person has unique preferences and abilities, people’s basic life (livability) needs – the fundamental constituents of livability – can be addressed through how we organize our cities. The pedestrian pocket and transit-oriented development (TOD) concepts first highlighted this point towards the end of the last century and have since grown in prominence and popularity. Walking, biking, and transit service, when paired with a meaningful mix of land uses, can provide a high degree of accessibility, even for nondrivers. By bringing land uses together, car use and transportation costs can be reduced, and residents can spend less time getting to where they need to go.

A framework for understanding life needs would allow this vision for a more livable, equitable city to emerge. Such a framework was developed as part of the Obama administration’s “Partnership for Sustainable Communities.” This program’s “livability principles” offer a shared purpose around which government agencies and other stakeholders can focus. The Sustainable Communities’ livability principles provide benchmarks for considering how to make a place more

livable, and have been adapted here to align with common roles for city planners and the stakeholders with whom they engage:

• High-Quality Transit, Pedestrian & Bicycle Connections

• Safe & Welcoming Walking & Biking Environments

• Diverse & Affordable Housing

• Diverse Jobs and Job Training

• Commercial and Cultural Destinations

• Health Care and Social Services

• Community and Recreation Opportunities

A high-level framework like this leaves out particulars such as personal preferences, but the livability principles succeed in broadly defining fundamental needs. They describe a set of needs that, if easily available, allow a person to lead a better life and, if accessible to all inhabitants, define essential ingredients for a more equitable city.

Transit-Oriented Development. Transit and walking become convenient options by concentrating homes and jobs near retail and transit, as shown in this diagram by the author.

The 15-Minute City describes an ideal type of place where most human needs are only fifteen minutes away. It is a planning concept that has attracted considerable interest within professional and political circles. The 15-Minute City concept was first popularized by Paris Mayor Anne Hildago, who articulated a principal reason that life in urban places can afford an exceptional quality of life –you can get to everything you need and more without endless hours in a car.

While the 15-Minute City explains livability in a succinct and relatable way, it only provides a general idea of what destinations should be gathered. The 15-Minute City concept inspires but doesn’t begin to sort through the attributes that could make it happen. To begin, it doesn’t attempt to define basic life needs with the same clarity as Sustainable Communities’ Livability Principles – which is necessary to bridge between the general concept and a clear community planning approach.

The 15-Minute City is not thought through in another important way –like the pedestrian pocket and TOD concepts before, a single district is not big enough. Except in places as dense as Paris and New York, a single district does not hold enough people to support institutional uses like health care and commercial uses like comparison shopping.

Economists routinely study the number of potential patrons needed for different types of developments. This thinking may be expressed best in Urban Land Institute’s “Shopping Center Development Handbook,” which says that access to department stores, theaters, and other subregional commercial destinations normally require a population upwards of 150,000 people. To get this population within a single district would need to average eight stories or more, something that is impractical in most American urban neighborhoods. But what if the 15-Minute City was organized around a multi-modal corridor that compressed distances within the same travel time without being car dependent?

The 15-Minute City. Ideally, cities would bring all of a person’s life needs together in a walkable district, as has been popularized by Anne Delgado and illustrated by Michael Dessin.

Scale Comparison of 15-Minute District versus 15-Minute Corridor. A transit or micro-mobility corridor extends how far a person can get in 15 minutes, when compared to walking 15 minutes in a single district. Consequently, a complete corridor offers a more practical way to connect people to more of what they need at densities that are more typical of American cities.

A multi-modal corridor can be large enough to include the range of land use destinations envisioned by the 15-Minute City and embodied by Sustainable Communities’ Livability Principles. Furthermore, corridor development is ubiquitous to American cities. In recognition of a multimodal corridor’s potential to address livability and equity in American cities, the Transportation Research Board commissioned the Livable Transit Corridors: Metrics, Methods, and Strategies” Handbook (referred to here as the “Handbook”) which defined livability and metrics to measure livability performance across 350 transit corridors nationwide.

While the Handbook provided the foundational elements for this vision, including the definitions of livability, measurement tools, and the strategies to implement them in a transit corridor, the potential of transit corridors remains unfulfilled in practice. Put simply, there is no organization or agency that champions comprehensive planning at a corridor scale, in which transportation facilities, land use decisions, and urban design investments are brought together. If such institutional challenges can be overcome, the livable transit

corridor remains a comprehensive solution to help us overcome our auto dependence and make our cities more equitable, sustainable, and livable. Furthermore, these concepts are equally applicable to other modes of travel. The possibility that a corridor’s transportation spine can be a continuous, enhanced bicycle facility for the rapid movement of bicyclists and other forms of micro-mobility is one such example.

Mixed-use multi-modal corridors— Complete Corridors—provide an affordable way to connect housing, employment, commercial destinations, and other essential uses in a single affordable car-free trip. Complete Corridors offer a new urban model that extends transitoriented development principles within a linear geography that is large enough to contain a complete array of life-need destinations, served by convenient, rapid, and high-capacity alternatives to car travel. Complete Corridors offer a robust way to give people of all incomes and abilities easy access to a full spectrum of uses and activities, thereby improving their quality of life.

Complete Corridors already exist in many places, and many of the

The Complete Corridor. The Complete Corridor model offers an way to assemble land uses for the most common life needs within a multi-modal corridor where its inhabitants can travel easily and affordably.

ingredients for Complete Corridors exist in many more. In urban settings, development patterns often predate the automobile and maintain historic transportation connections and land use mix. In suburban situations, mixeduse activity centers, provide the kinds of destinations than would otherwise occur along transit lines created since the advent of the car.

In places where vital land use destinations or car-free mobility options are absent, corridor planning can play a vital role in creating more livable and equitable communities. With the Livability Principles serving as their touchstone, community planners can work to integrate transportation, land use, and design, in more effective and equitable ways. As a community planning model, the Complete Corridor

can be applied to create holistic communities—livable neighborhoods within a larger city and region connected by alternative travel options.

In brief, Complete Corridors organize land use intensity and lifeneed destinations along a reliably swift transportation spine and is accompanied by safe welcoming pedestrian and bicycle environments

and connectivity. Complete Corridors perform well across all the domains identified by the Livability Principles.

High-Quality Transit, Pedestrian and Bicycle Connections. Along the length of the Complete Corridor is a transportation spine that offers highquality transit, bikeway, and pedestrian connections. These alternatives to the car are prioritized for safety and reliability, such as providing buses with dedicated lanes, and queue jumps lanes for bicycles. Land uses along the Complete Corridors concentrate trips and allow transportation investments and operations to be more targeted than diffuse transportation systems.

Safe and Welcoming Walking and Biking Environments. The experience of moving across a corridor is a key ingredient to the success of its walking and biking environments. A sense of safety is paramount, such that traffic is calmed and routes are inhabited by active building fronts. Environments are made more welcoming when buildings and landscape attends to the human experience, not the least of which is climatic comfort afforded by street trees.

Diverse and Affordable Housing. A more inclusive community offers diverse housing options with something for most income brackets, particularly affordable housing. Programs for the production and protection of affordable housing can target corridors where more housing options are needed. Complete Corridors can also leverage more affordable market-rate housing, as living in Complete Corridors is less expensive since a dollar spent on a car means one less dollar for household housing, food, and education.1

Diverse Jobs and Job Training. A key challenge for low-income workers seeking employment and betterpaying jobs is the mismatch between the housing where they live and the types of jobs that they can get to easily and affordably, as high car costs and long bus rides make having a job more difficult. Economic development programs can encourage certain types of businesses to locate along corridors where there is available workforce. Programs can also provide ways to help residents acquire work skills that fit the needs of existing businesses,

1 The Center for Neighborhood Technology, H+T Index, online: https://htaindex.cnt.org/

such as by improving corridor access to community colleges and job training programs.

Commercial and Cultural Destinations. Livability is enhanced when commercial destinations, like retail and personal services, and cultural destinations, like theaters and places of worship, are easy to reach. Research by Reid Ewing and others show the availability of commercial and cultural destinations influences the extent to which people drive farther and spend more money on transportation. 2 Furthermore, the real estate industry recognizes demand for convenient access commercial and cultural destinations, such as in the rise of mixed-use lifestyle projects3 and the Walk Score assessment of a location4.

Health Care and Social Services. A corridor is not complete without access to health care, which is recognized by the World Health Organization as a fundamental

2 Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 1994. The Effects of Land-use and Travel Demand Management

3 Strategies on Commuting Behavior. Technology Sharing Program. Prepared for the U.S. Department of Public Transportation, Washington, DC.

4 https://www.walkscore.com/

human right,5 and regardless of age, income, or ability. An ideal corridor places health care providers within steps of the transportation spine, such as along Cleveland’s Euclid corridor “Health Line.” Last mile strategies can also be employed, such as shuttle buses connecting transit to hospital campuses. Under either scenario, health care availability— like retail developments discussed earlier—depends on easy access to large numbers of people. Similarly, a Complete Corridor provides barrier-free access to government services, such as offices that interview candidates for public assistance or provide crisis intervention.

Community and Recreation Opportunities. A person’s well-being depends on having opportunities for socialization, exercise, and relaxation. Complete Corridors provide easy, affordable access to community and recreation destinations, like schools, libraries, community centers, and recreation centers. Because corridors may touch areas that are developed less intensively, some corridors can offer access to open spaces that are 5 https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/ detail/human-rights-and-health

large enough for playfields, hiking, and contact with nature. Community and recreation opportunities complete the spectrum of basic needs that a Complete Corridor should provide.

A Complete Corridor is large enough to integrate complementary land uses and destinations, yet focused enough for meaningful corridor-specific visioning, transportation and land use planning, urban design, and implementation programs. If city planners held this as an aspiration, it would set them on a path to making more livable and equitable cities – ones in which there is safe, convenient, and affordable access to life-need opportunities.

While corridor planning is not new, rarely has community planning aspired to integrate multi-modal transportation investments, holistic land use planning, human-centered design, and stakeholder engagement with the shared purpose of promoting livability for persons of all ages, incomes, and abilities at scale. Related concepts get part of the way: the 15-Minute City emphasizes a full complement of life-need destinations and walkability; and Transit-Oriented Development integrates transportation, land use, and design, within a single neighborhood district.

However, the potential of integrated cross-disciplinary corridor-level planning has remained obscured, except as arises when thoughtful

planning identifies land uses and transit enhancements that a community needs. One example of this is seen in the Denbigh-Warwick Area Plan that includes recreation of a strip commercial corridor in Newport News VA (see following section, “Case Studies”). Minneapolis-Saint Paul’s Corridors of Opportunity initiative is another example of a comprehensive set of strategies and programs that took advantage of and contributed to investments in a new light rail corridor (see Case Studies), but by and large, the potential for corridor planning to address urban challenges has not been recognized.

So if Complete Corridors are so good at addressing human needs and planning challenges, then why are they missing from our planning lexicon?

This question was posed to leading planners from around the country to help identify obstacles to Complete Corridors and how to overcome them.

Government Silos. Complete

Corridor visualization and creation is frustrated by institutional “silos” that separate regional transportation planning and investments from local land use authority and public

realm improvements. City planners everywhere face challenges engaging community stakeholders effectively, so that plans and their implementation align with a community’s values and needs, and such that planning outcomes benefit all persons regardless of income, ability, ethnicity, and other characteristics.

Suzanne Hague, sustainable equitable communities expert for the California Air Resources Board, attributed the lack of action to the balkanization of government, in which different government bodies are responsible for different things and at different scales. Few entities have boundaries that match the combined transportation

and land use geography of a corridor. Government funding and agencies need to point at corridors, but since this is rare, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and other private sector interests can help them focus. Conceivably, business improvement districts could be formed at the scale of corridors to shepherd visioning, attract investments and manage on-going programs. In the meantime, programs like California’s Transformative Climate Communities program can support corridor initiatives provided that local governments and transit agencies come together with shared purpose.

Land Use / Transportation Integration. Focusing on Complete Corridors can bring together local land use authority, regional transportation authority, community stakeholders, and financial partners.

Reasons to Participate. Michael Carroll, the Deputy Managing Director for Transportation, Infrastructure, and Sustainability for the City of Philadelphia, put it more bluntly: at a time when every public agency is overwhelmed with delivering on their core mission, why should they care about Complete Corridors? Agencies and organizations need to understand how corridor-level planning and cooperation makes their work more effective, easier to accomplish, or better funded. An early member on TRB’s Livable Transit Corridors research team, Carroll underscored that, while it is imperative to have corridor-focused collaboration across agencies and disciplines, partners need to have a direct stake in the partnership and outcomes.

An example of this is the Grand Boulevard Initiative along El Camino Real, which extends through multiple local jurisdictions on the San Francisco Bay Peninsula, and presents one of the Bay Area’s longest and underutilized corridors (see “Case Studies”). The Grand Boulevard Initiative is funded by the local jurisdictions but has no land use authority, no funds to administer, and no latitude for advocacy beyond already-adopted local policies.

Political Motivation. Shelley Poticha, chief climate strategist for NRDC and a longstanding smart growth practitioner, held little hope for government to lead communities toward innovative planning models like Complete Corridors. While she has worked at the highest levels of government and led the Partnership for Sustainable Communities at US HUD, she asserted that lasting paradigm shifts almost always come from advocacy work. Topdown planning and funding programs often follows rather than leads public opinion, and innovations funded by grants stall as funds dry up.

Corridor planning that prioritizes access to opportunity can be initiated and championed by community-based organizations. Fresno’s Blackstone Avenue corridor presents another example of Complete Corridors (see “Case Studies”), where communitybased organizations (CBOs) developed a vision to attain an interrelated set of livability pursuits including business district revitalization, small business development, education and job training, and affordable housing.

Economic Realities. Dena Belzer, founding Principal of Strategic Economics, attributed an absence of corridor-level initiatives to market vagaries, where favorable planning opportunities can go unrealized for decades. Good ideas often lay dormant awaiting a catalyst that, when it arrives, may manifest in ways that are different than expected, and an inability to predict the pace of implementation is not unique to corridor plans.

Pragmatic Adaptation. Val Menotti, the Chief Planning & Development Officer at San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) works within the limitations of the current system, pushing it to address corridor-scale challenges and opportunities. Menotti explained that, for the foreseeable future, regional and local governments will tend to “stay in their own lanes.” Transit agencies have no influence over land use controls along a corridor or near transit but have direct control over transit service and encourage enhancements to pedestrian and bicycle access through studies and grants. City government can be expected to continue focus on land use planning, while taking interest in location-related advantages afforded

by regional transit. Meanwhile regional and state governments can provide incentives for land use, transportation and design integration by funding studies, plans, and infrastructure improvements.

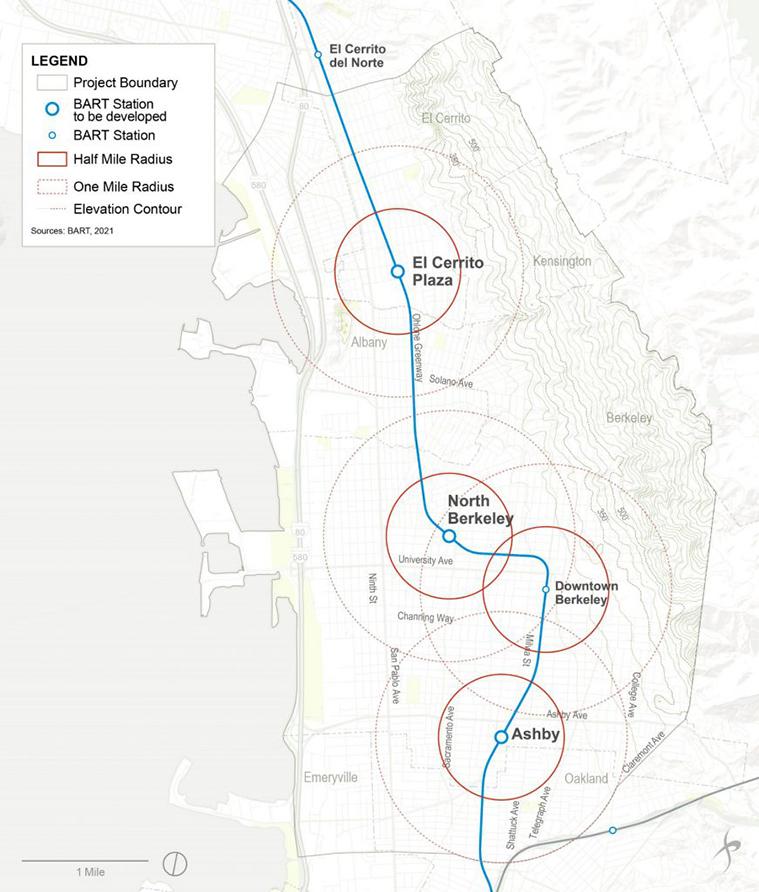

Menotti works in a cooperative fashion with the interests of other governments and grassroots organizations along BART operational corridors, where incremental changes to policies and programs can lead to Complete Corridors over time. As illustrated by activities along its East Bay corridor, BART works with local governments to plan and fund station access improvements that take the form of bicycle lanes, pedestrian safety, and bus service to BART stations. BART is also actively advancing development on the properties it owns to increase housing and transit ridership.

Equity = Access. The most important take away from the complete corridor concept is an awareness that access to opportunities is a key aspect of equity –an aspect of equity for which planning professionals have agency through land use, transportation, urban design policy and projects. Equity relies on reliable and affordable mobility options. like transit and micro-mobility, and rules out reliance on car ownership because of its cost and car use because many among us cannot afford or do not have the ability to drive. Equity also relies on connecting to and therefore bringing together a complete array of life-need destinations like affordable housing, job opportunities, and other categories of land use described above in “Defining Life Needs.”

Target Investments. Complete corridors are large enough to integrate land use needs but small enough to target transportation investments and economic incentives to attract uses and services needed by the community. New sources of government funding recognize the potential of land use, transportation, and design integration to address livability and equity. Many states and regional agencies fund plans to promote transit-oriented

development around one or more station areas, which consider land use, transportation, and urban design in an integrated way. At the corridor scale however, funding tends to be for transportation infrastructure in response to existing land use patterns, as if land use patterns were fixed. One notable exception is U.S. Department of Transportation’s “Areas of Persistent Poverty Program,” which supports transit infrastructure and planning to improve access to jobs, health care, and education, by overcoming barriers posed by automobile dependency. Another exception is California Assembly Bill 2011, which allows “by right” housing development along commercial lands that front arterial roadways, and could precipitate the transformation of underutilized strip commercial corridors into mixed-use corridors, if market forces allow and where multimodal transportation options are provided.

Work Toward a Common Vision. Complete Corridors are much more than a spatial concept. They are a way of organizing community conversations, planning analysis, and decision making that attends to both local and citywide concerns. Public agencies, private

development, social service providers, and community organizations tend to work within interest-based silos. Separate interests can be integrated around a shared purpose – the complete corridor. For each of the life-needs definitions outlined above, specific livability and equity objectives can be developed and can be informed by a “needs assessment” comprised of metric indicators, as was done to evaluate over 350 different corridors as part of TRB’s Livable Transit Corridors Handbook.

The Complete Corridor concept provides communities and planning profession with an attainable rubric for providing equitable access to fulfill the most common life needs. It can build bridges between private sector

business interests, equitable housing advocates, transportation agencies, and city, county, regional, state, and federal governments—toward a common purpose of building more livable and sustainable communities. It focuses them on how to assemble most basic life needs within a robust spatial model - the mixed-use multi-modal corridor. This focus can further social good while benefiting all stakeholders: as transit agencies gain riders, city and county governments increase tax revenues and economic activities, regional governments shape their land use and transportation systems, and developers and residents enjoy the dividends of enhanced livability – regardless of income, age, or ability.

Blackstone Avenue Corridor, Fresno, California. Community-based organizations (CBOs) partnered with local government to address the life-needs of disadvantaged populations along Fresno’s Blackstone Avenue corridor through various projects. Fresno Metro Ministry (Metro), Local Government Commission (LGC), and the Better Blackstone Community Development Corporation, worked with the City of Fresno and the Fresno Council of Governments (COG) to promote business district revitalization, small business development, affordable housing, and access to education, along a corridor that will be served by bus rapid transit. A mixed-use urban boulevard is emerging as strip commercial uses along an autooriented roadway give way to incremental infill and complete street improvements. Planning along Blackstone Avenue has focused on community needs by bringing together an array of complementary land uses and enhancing transportation options, such as future BRT service (image below). Read more using QR code below (http://arccadigest.org/becoming-the-blackstone-opportunity-corridor/).

activity center areas – there mixed-use zoned parcels with distinct property owners and 618 businesses

Four Activity Centers. In the 4 activity center areas, there are 503 mixed-use zoned parcels with 335 distinct property owners and 618 businesses.

Sheilds Activity Center

Better Blackstone Design Challenge (BBDC). The BBDC is a Fresno COG project led by Metro and funded through Caltrans Strategic Partnership grant and SB-1 funds. The goal of the project is to produce alternative feasible TOD design scenarios; gap financing related to economic, real estate, and Urban Footprint multi-variate analyses translated into useful web-based tools; and on-going technical assistance for property owners and developers along Blackstone corridor. Project scope examined different design alternatives with emphasis on land-use design for four activity centers along the corridor from Shaw and Blackstone activity center all the way to Olive and Blackstone.

April 2012: City of Fresno 2035 General Plan Update Alternative ‘A’

Dec. 2014: City of Fresno General Plan

June 2014: Fresno COG 2014

July 2017: Fresno COG 2018 Regional Transportation Plans and Sustainable Community Strategies

Dec. 2015: City of Fresno Citywide Development Code

Feb. 2016: New Zoning Map for City of Fresno (effective as of March 7, 2016)

Dec. 2016: City of Fresno Active Transportation Plan

April 2017: Blackstone Corridor Transportation + Housing Study

May 2019: Southern Blackstone Smart Mobility Strategy

June 2020: Blackstone/Shaw Activity Center Study

Denbigh-Warwick Area Plan, Newport News, Virginia. In Newport News, Virginia, the gradual economic decline of a suburban commercial strip became an opportunity to reinvigorate the larger area through infill development that targets community needs. In response, the Area Plan sets the stage for creating cultural space (in the form of a new library with community programs), attracting commercial gathering places (like restaurants, tap-houses, and family-friendly venues), and constructing more housing (at all levels of affordability).

By calling for pedestrian-oriented infill development, the Denbigh-Warwick Area Plan addresses how to deliver more housing at all levels of affordability in locations that are served by transit and close to commercial and community services. The Plan, which was authored by WRT, also calls for transportation investments to support walking, bicycling, and transit use.

Read more online at:

https://www.nnva.gov/2401/Denbigh-Warwick-Area-Plan

Corridors of Opportunity, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota. Along MinneapolisSaint Paul’s newest light rail transit investment, the Corridors of Opportunity initiative focused the how to deliver housing affordability, promote economic development, and improve access to life-need destinations within vibrant transitoriented district. Through its “Corridors of Opportunity” initiative, the Metropolitan Council of Minneapolis-Saint Paul engaged stakeholders along light rail transit corridors to understand community needs and address them through land use policy, street improvements, and economic development tools (image credit: Ruch Associates).

Administered by the region’s Metropolitan Council, the Corridors of Opportunity program led to comprehensive station area plans, along with job training and small business assistance for less advantaged populations. Image credit: Met Council.

Read more online at: https://metrocouncil.org/Communities/ Projects/Corridors-of-Opportunity.aspx

BART East Bay, San Francisco Bay Area, California. Joint development of BART parking lots is delivering much-needed affordable housing within five minutes of downtown Berkeley and UC Berkeley, among the region’s largest job centers. Community engagement identified additional needs, such as to provide small parks and lease space to community groups. The Bay Area Rapid Transit authority, BART, and local jurisdictions have worked in parallel to improve station access, build housing, and support community-based organizations and the social services they provide. BART has pursued joint development of its parking lots for housing at 75 dwelling units per acre or higher, as mandated by State of California legislation that also granted BART land use authority over BART’s property.

Knowing that BART intended to develop its property, local jurisdictions selected to work in partnership with BART to address local context through form-based standards. Local jurisdictions also requested that BART development deliver deeply affordable housing, community open space, and subsidized space for non-profit groups that deliver services to less advantaged populations such as persons with disabilities. Simultaneously, BART worked with the Cities to develop “access plans” to strengthen pedestrian, bicycle, and transit connections to stations as park-andride parking becomes more limited. BART and the Cities’ engaged community members and other stakeholders extensively.