WUPR

Washington University Political Review

Theme Spread

Loderstedt

Reflections on Bottled Water Jordan Bradstreet

Theme Art Eric Kim

A Love Letter to Lake Michigan Celia Rattner

The River Caleb Cohen

Theme Art Ceci Deleon-Wilson

WET: Navigating Hook Up Culture Erin Ritter

Water is the Universal Weapon Jason Liu

Breathing Underwater for Dummies Matthew Boyd

Theme Art Mei Liu

In Fashion, Green Doesn’t Mean Clean Jessie Wills

Crashing Waves of Grief

Duran Garcia

Floodgates Gabriela Martínez

Theme Art Ben Eskenazi

Biden’s Student Debt Relief Plan Amrita Kulkarni

Peter Thiel’s New Right-Wing Acolytes Gabriel Squitieri

Vindication: Biden’s Theory of the Case Josh DeLuca

Hungary for Power: Orban in America Will Gunter

Infrastructure Week Should Be Every Week Lara Briggs

Life After Dobbs: A Socioeconomic Take William Yoo

on the Horizon Hannah Richardson

Syria: A Decade Later, the War Rages On Phillip Lisun

China’s COVID Crossroad Michael Qian

Beware the Danger of Economic Decoupling Zubin Rekhi

The Trump Trap: An Economic Race for Hegemony Leo Huang

The Beef Parasite of Questionable Existence Lawrence Hapeman

Letting it Rain in the UAE Jordana Kotler

Sophie Conroy

Alaina Baumohl

Jaden Lanza

Shonali Palacios

Staff Editors

Will Gunter

Tyler Quigley

Oliver Rosand

Evan Trabitz

Celia Rattner

Drew Rosenblum

Matthew Shepetin

Haejin An

Lea Despotis

Daniel Moroze

Jinny Park

Jordan Simmons

Web Editors

Adler Bowman

Jeremy Stiava

Will Pease

Podcast Editors

Lawrence Hapeman

Alexis Hyde

Erin Ritter

Programming Director

Harry Campbell

Treasurer

Larry Liu

Daniel Moroze

Ethan Loderstedt

Asher Charno

We are excited to start off Fall 2022 strong and bring you the Water Issue. Themes each month are selected by vote within WUPR’s Executive Board, and we’re impressed by the insightful and diverse discussions this theme inspires. Notably, for Jaden and I, the very first WUPR issue of our freshman year had the theme of Fire. WUPR has been a huge part of both of our college experiences, and these serendipitously complementary themes make that journey come full-circle.

It has been a challenge to maintain community these past two years due to COVID-19 related restrictions. However, our small but mighty WUPR team has stayed tight-knit. It has been so rewarding to see our community together again and to welcome new editors, artists, writers, and readers back to a space that has been a source of growth, support, and inspiration for myself these past three years. I know that I can say on behalf of us both that we’re grateful for each and every one of you.

In this issue, Jordan Bradstreet reflects on the profoundness of bottled water and our disconnection from the natural world. In her article, Emily DuranGarcia explores the everlasting experience of grief and how we can learn to live alongside it. Celia Rattner shares “A Love Letter to Lake Michigan,” and Jordana Kotler discusses cloud seeding, a geo-engineering technology that could allow countries to “steal” rainwater from one another. National topics include critical analysis of Biden’s recent student debt relief plan by Amrita Kulkarni, as well as insight into hookup culture at Wash U and universities throughout the U.S. by Erin Ritter. Lawrence Hapeman tells a satirical tale about a questionable plan to fight climate change, and Zubin Rekhi touches on the dangers of economic decoupling in our international section.

Altogether, we think Water provokes so much in the imagination as both a source of symbolism and a site of fruitful political discussion. We had a lot of fun putting this issue together, and we hope you enjoy reading it just as much.

Jordan Bradstreet Design by Eric Kim

Jordan Bradstreet Design by Eric Kim

Water: the elixir of life. Everyone and everything loves water. No one would take water to a candle lit dinner; it’s not that kind of love. It is a bond like the one some might have with their parents, a bond that is often taken for granted and given little thought. This attachment is so fundamen tal, and so secure for many of us, that we never think about it. We forget that without water our skin would shrivel, our sweat would cake our bodies in salt, and our minds would plunge into delirium as they dry out.

Love for water, though, is rarely unconditional. Not all water is friendly. The water of the ocean is cold and abrasive, and we’re constantly fight ing hurricanes, floods, and leaky roofs. Water doesn’t have any care for our love towards it. It does what it will, and sometimes it is an agent of destruction and death. We do a lot to ensure it will bring us life more often than death. We’ve funneled it into our homes, we’ve calmed it with dams, and we’ve harnessed it to power our cit ies. But what is the crown jewel of our triumphs? It is something mundane: bottled water.

Bottled water is incredible precisely because it is so mundane. It is the antithesis of the chaos of nature. Every bottle is a lifeless and sterile sea

— each entirely identical to its predecessors. It has transcended all of time and space. We don’t know where it comes from. They say it comes from a glacier, or a spring, or God’s tears, but all we know is what is said on the bottle. Maybe they actually filter and bottle up my own sew age and sell it back to me. Who could say? And it tastes fine, so who would care at the end of the day? There are no limits to the perfect equa nimity and uniformity of bottled water; it is truly the pinnacle of industrialism and man’s triumph over nature.

Grip. Twist, snap. Lift and lean back. Gulp gulp gulp gulp gulp.

The mild thirst that had been tugging at the edge of your mind is quenched, and your shoul ders relax as the water hits you with its sooth ing, cool relief. How convenient! How renewing! Truly what a gift! What great ease and control you have with bottled water — as long as you're strong enough to open the lid, that is.

It gets better: bottled water comes in different flavors. With tap water we don’t get to choose the taste. We balk at its subtle impurities. Who knows what’s in those pipes that deliver it to us? Do you really trust the government to give you

clean water? Fortunately there is bottled water for everyone. There is Dasani, Aquafina, Smart Water, and for those of a more aristocratic bent, Fiji Water — water straight from the heavens, untouched by man and his sins. Don’t forget that there is more to choosing a kind of bottled water than how it tastes. A small part of your identity is at stake. Your choice is just as much part of you as the clothes you wear or the kind of music you listen to.

All of this has brought a great turn inward. Our choice of water has more to do with our frivolous tastes and identities — more to do with ourselves — than the outside world it comes from. It is brought so far away from the untamed, constructive, and destructive force of water in nature that we never even think to consider its source and what it once was before reaching us. We don’t stop to picture the mighty Colorado River fizzling out before it reaches the sea, the aquifers under our communities pump ing out less than they did last year, or the factory gulping down oil to churn out thousands of bot tles every day. Why would any of that be on our minds? We don’t see any of it. For all we know, the things we consume came from Mars. And why should we care? Whatever problems exist out there are not our problems. They happen somewhere else to someone else or something else. We don’t even see that there is a problem most of the time, because no matter what hap pens out there in the world, the same sterile and tame water is always there when we go to the store. Everything is fine. Everything will be fine until it isn’t — and we might not see it until it happens.

Jordan Bradstreet ‘24 studies in the College of Arts & Sciences. He can be reached at bradstreet.j@wustl. edu.

But what is the crown jewel of our triumphs? It is something mundane: bottled water.

When I think of home, I think of sprawl ing blue water, hazy horizon lines, and icy-cold currents. No, I’m not from the Bay or Nantucket. I am from America’s third coast: the shoreline of Lake Michigan.

To be specific, I grew up in Chicago’s northside neighborhood of Lakeview. And though the lake’s namesake takes from Illinois’ north eastern neighbor, Lake Michigan has long been embedded in my identity. The entire city of Chicago is built around it.

As a Chicagoan, you are taught at an early age that “the lake is always East” when learning to navigate the city. For 14 years, my commute to and from school took place on Lake Shore Drive. The athletic club my family frequented for over a decade was also named Lake Shore. Next to Lincoln, “lake” is probably the most common L-word you’ll find in the Windy City.

Simply put, I — like most other Chicagoans — love Lake Michigan. It is integral to the city’s identity, and, thus, integral to mine. My

summers would be incomplete without dips in the lake and my winters would probably be a lot more manageable were it not for Lake Michigan’s unforgiving wind.

And, to be frank, it’s strange to live in an area so removed from such a body of water. How do I know autumn is coming if I can’t observe the dwindling number of boats in Diversey Harbor, or prepare for spring without notice of the mountains of melting ice that pile along the lake’s edge?

It’s difficult to remember when I first became aware of climate change. But, I feel as though global warming has always been on my mind. The term “global warming” was first coined in 1975, but I must have always assumed Chicago gained immunity due to its inland nature. In the last decade, however, Lake Michigan’s water levels have risen nearly six feet, with a record 9.51 inches of rainfall in May 2020.

Let’s put that in context.

Chicago, like many major American cities, was built on swampland and gained prominence after the construction of a canal, which con nected the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River Basin. In 2013, Lake Michigan’s water levels hit a record low, but have since grown six feet, reaching record highs in 2020.

Chicago’s infamous weather cycles — heavy snows that lead to heavy rains which lead to summertime swells — aren’t helping either. Though Lake Michigan may appear indistin guishable from an ocean coastline, the Great Lakes behave more akin to rivers: they deposit

into one another and flow to the Atlantic via the St. Lawrence River.

These deposits are replaced by rain and snow, but climate change has exacerbated normal evaporation and precipitation cycles, causing the last five years to be the wettest in recorded history. Factor in the fact that the average air temperature in Chicago has risen 1.2 degrees Fahrenheit since 1991 and it’s no wonder lake levels have risen as well.

I’ll spare you more details about the wind pat terns, ice levels, and the notorious Polar Vortex. The lake’s levels have decreased since 2020, but the trends are alarming nonetheless. All this to say: flooding has gotten worse, beaches have disappeared, and it is clear that the lake’s ebb and flow jeopardizes the city’s future.

I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge the disparate impacts of such flooding. Many of the city's more impoverished south side neighbor hoods have been slammed by the recent flood ing, with the working-class neighborhood South Shore bearing the brunt of the lake’s force.

Though the city has requested federal funds to build a barrier along South Shore Drive and has concocted other plans to mitigate shoreline ero sion, the financial burden on individual residents has already added up. Yet, many have criticized the city’s response as neglectful toward south side residents.

To be frank, it all frightens me. Climate change is a slow process, but one that is clearly quick ening. In a public policy course I’m taking this semester, we discussed the ways governments

place dollar amounts on climate change. New reports are showing that the current levels we assign to carbon — $51 per ton — are far too low, and $185 per ton is a more accurate esti mate. These new figures forecast devastating consequences if action is delayed.

Scientific studies like this lead to questions: How long have we been undervaluing the effects of carbon emissions? Is it too late? As I sit writ ing this paper during a 99 degree day in late September, I fear the worst. Is there any hope of stopping climate change in its tracks? If not, how do we mourn something that still exists?

Celia Rattner ’25 studies in the College of Arts & Sciences. She can be reached at crattner@wustl.edu.

Simply put, I — like most other Chicagoans — love Lake Michigan. It is integral to the city’s identity, and, thus, integral to mine.

The steel bleachers shook as the antic ipation grew. The spotlight poked center stage and everyone stood with the anticipation of something great. Bruce Springsteen walked out with the force of a giant. The hard strum on his worn-down, mustard-col ored guitar hit the strings with a fist full of power, and the crowd roared. Springsteen’s con certs are a marathon of music and story-telling, spanning almost four hours. There are not many moments I can point to and say changed my life. Bruce Springsteen’s 40th anniversary tour of “The River” was one of those moments.

The show was equal parts religious experience and political campaign rally. Springsteen asks his audience to take stock of their lives and the American dream as a whole. While Springsteen has lent his support to Democratic candidates over the years, he imbues his performance with themes that are small-d democrat — hard work, neighbors helping neighbors, and communities that leave no parts behind. He is the last of a generation of musicians that include Dylan, Lennon, and Cash to use the stage as a bully pulpit for political ideals.

Springsteen’s enduring appeal is that he is able to attract both sides of the political aisle — sometimes in the very same song. In argu ably his most famous album, “Born in the USA,” conservatives embrace the anthemic superfi cial title and wrap themselves in the flag that is showcased on the album’s cover. Whereas, liberals appreciate the lyrics of the song as n indictment of the Vietnam War. Springsteen has built a career honoring the hard work of the underpaid and under-appreciated, but is unafraid to hold people accountable, as he does to police officers on the song “American Skin.” That song was inspired by the 1999 shoot ing death of Amadou Diallo by New York City police officers. At the time, some police asso ciations called for the boycott of Springsteen’s shows. Where other artists may have caused more controversy with such a political song, Springsteen's life-long commitment to writing about the promise of America gives him the cover to touch on politics and move on.

Springsteen's albums have staying power because they reach beyond politics and into the daily struggles of the average American. In the 1970s, “Born to Run” explored the idea of free dom and the open road. On the album’s cover, Springsteen subtly touches on racial politics with a picture of him and his black friend and saxophonist Clarence Clemmons standing by his side. It was not insignificant to have a man of color standing center stage with a white man, Springsteen, during this time. In the 1980s, it was “Born in the USA,” and in 2000, “The Rising,” which was an answer to terrorist attacks on our country. It was a moving exchange of words that brought a country back together. It is filled with both mourning and resilience. It is a powerful look into the strength of America and its people. Like any political figure, people look towards Springsteen for inspiration. He is a steady voice that speaks for the country, and like a successful politician, captures your curios ity and attention through his words.

For me, Springsteen’s powerful tales of sorrow and triumph began with “The River.” On this album, the ideals of youthful freedoms are met with the responsibilities of growing up. It is a double album with 20 songs. About midway through the concert he arrived at the title track. It’s a classic Springsteen song about the story of a life in transition. Here Springsteen substi tutes the symbolic freedom of the open road and the westward railway for a winding body of water. Near the end of the song, he asks, “Is a dream a lie if it doesn't come true?” The ques tion is quintessential Springsteen. Once again, he is testing his audience’s faith in the American dream. In the hands of somebody else, this

might be an inherently political question. It is the kind of one-liner or soundbite a politician would use to get the attention of their audience. In the hands of Springsteen, it's not a question of politics. It's about the strength of chasing a dream when there are setbacks. It is the premise of most of his music that touches on the idea to never stop believing. Springsteen has the unique ability as an artist to make us think and feel at a concert and to restore for just a few hours the sense of a shared community.

Next year, Springsteen will embark on what will likely be his last tour. At 73 years old, he doesn’t have to tour, he doesn’t need the money, and he doesn’t have anything left to prove. I think it is his way of telling his fans that if you keep going down to the river, one day the dream will come true.

Caleb Cohen ‘25 studies in the College of Arts & Sciences. He can be reached at c.b.cohen@wustl.edu.

Springsteen’s enduring appeal is that he is able to attract both sides of the political aisle — sometimes in the very same song.

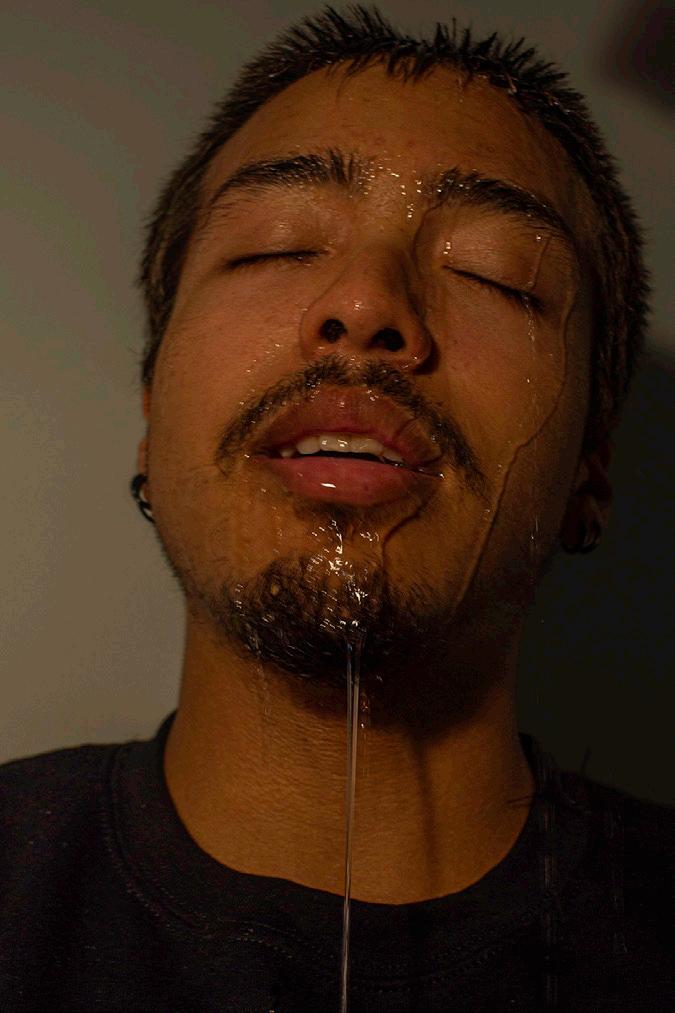

Erin Ritter, Podcast Editor

Photography by Jordan Simmons Modeled by Wladimir Alarcon

Erin Ritter, Podcast Editor

Photography by Jordan Simmons Modeled by Wladimir Alarcon

I’ll never forget my first hook-up experi ence: it was the first week of my fresh man year at Wash U. I met him through some mutual friends and we hit it off quickly. We chatted as we strolled through the unfamiliar campus scenery and made out behind the DUC (what an incredibly embarrassing freshman thing to do). One thing led to another, and he met me in my dorm room one night. Up until this point, it had felt a little like some cute 90’s comingof-age romantic comedy… until we realized neither of us knew what to do from there. Needless to say, it was awkward, and not just because he cried two days later when he found out I was also hooking up with his roommate (yet another embarrassing freshman thing to do). As weird as it felt at the time, my experience wasn’t all that uncommon. If I could go back to prevent myself from diving too soon and hitting my head on the metaphorical pool floor, I’d tell my naive freshman-self to read an article like this.

What is hook-up culture? The American Psychological Association defines hook-up culture as “the shift in openness and acceptance of uncommitted sex.” Studies show that 90% of college students believe that their campus demonstrates hook up culture, while an estimated 72% of college students participate in hook-up culture. According to the National College Health Assessment, only 20% of students hook up regularly and 35% don’t hook up at all. In short, no matter which side of the pool you’re on, you are not alone.

Regardless of your experience in the mat ter, we do need to clarify one thing before diving in the deep end: consent is a neces sary component of any sexual or romantic encounter, and it goes much deeper than a simple “yes.” In fact, consent is more

of an ongoing conversation. You and your partner might feel comfortable at first, but feelings are fluid; consent is reversible and needs to be discussed continually. Clear, open conversation is necessary as one can’t rely on assumptions, perceived gen der roles, or a lack of protest to guarantee consent. As always, but especially with a new partner, previous flirtation or conver sations hold no bearing on your current encounter. In addition, traditional gender roles often disregard the fact that women can be perpetrators as well, leaving men and masculine folks at risk. Finally, unless there’s a clear and enthusiastic “Yes!”, the answer is no.

What does this look like? Try dipping your toes in with this simple conversation starter: “What are you into?” Short and sweet, but highly effective. After estab lishing this, you can move on with, “What are you comfortable with? Do you want to [blank]?” The best part about constant conversation is that you don’t have to rely on previous sexual experience to impress your partner. As all good sex should be, you and your partner make it up as you go along! If you want a seriously hot way to keep the discussion up, use phrases like “Does this feel good? Should I keep going?” In general, it’s best to ask before doing: “Can I put my hand here?”

While consent is paramount in any circum stance, it’s important to acknowledge that the consent conversation that happens during a relationship can look a lot different during a hook-up. According to one study, almost 50% of respondents indicated that they had hooked up either during the first in-person meet up or within the first few weeks of meeting, and the other half indi cated they waited more than a few weeks. And while the time period is varied, you cannot guess at someone’s sexual comfort levels without asking them. In a relation ship, an element of trust has already been established. Hook-ups don’t have this; therefore, one of the most important parts of this conversation is maintaining aware ness of your partner’s demeanor as well as your own. Does your partner appear hesi tant? Are you both sober? If in doubt, play it safe by not continuing. It is always bet ter to be awkward than risk overstepping boundaries or hurting someone. Again, silence does not mean consent. Nerves can get in the way of your partner verbal izing their concerns; check in frequently. Sometimes even the most experienced folks lack the knowledge or confidence it

...consent is a necessary component of any sexual or romantic encounter, and it goes much deeper than a simple yes.

takes to breach the subject. And the truth is, no matter how many Canvas modules you complete or infographics you like on Instagram, having these conversations will still feel a little weird.

The good news is, if it feels a little awkward at first, you’re doing it right! Think of every sexual encounter you have witnessed in the media: hot, fast, and often wordless (but accompanied by plenty of noises.) Think Sex Life on Netflix, Fifty Shades of Grey, or Game of Thrones. Spoiler: sex doesn’t always look like that. At least, I hope it doesn’t. When actors film these scenes, they’re required to wear special padded underwear that prevents any sensation or contact. If that doesn’t have enough of a cold-shower-effect, there’s also a room full of directors and choreographers to advise. Not only are these examples often skewed in an idealistic light by being heteronorma tive, uninclusive, and just plain scripted, these scenes reinforce harmful ideas about what sex actually is. Rather, what it’s not. To put it bluntly, sex can actually be kind of gross. Think about it: various bodily flu ids, razor burn, back acne, and less-thanfresh smells. Certain sex acts often result in some unexpected consequences. Any vaginal penetration is usually accompanied by some sort of vaginal flatulence. Giving oral can be fun until you get a pube stuck in your throat, and receiving oral is awesome until you feel some teeth. Specks of toilet paper left over from the day’s toilet breaks can even make an appearance. And no matter what hole(s) you’re engaging with,

you’ll almost always end up with a suspi cious stain on the sheets. One can only wonder as to what Christian Grey would do if he found a mysterious brown spot on his red leather mattress.

At this point, I’ve probably convinced you that every passionate sex scene you’ve ever seen was incredibly unrealistic (it was) and that real-life hook ups will never live up to them. And if TV sex isn’t your thing, think back to any story you’ve ever heard from a peer and look at it through the lens of sex ual maturity. Chances are they didn’t men tion the inner struggle between leaving the socks on or taking them off, the awkward silence that came after the fart that wasn’t a fart, or the unsettling amount of sweat. Not to worry, my friends, there does exist a balance between hot and cringeworthy. The secret: embracing the weird! Now that you’ve established consent through contin uous conversation, you can use this com munication to put your partner at ease. Be

honest about your thoughts and feelings to empower your partner to do the same. Reassure them that the inner-sock-battle isn’t a big deal. Hook ups should be fun! Don’t be afraid to giggle every now and then.

So, we’ve got the hook-up itself figured out, but what about the aftermath? As I’ve demonstrated with my story, a conversa tion with your partner about boundaries would save you both (or at least one of you) some tears. Are you both interested in a hook up? Statistics show that people who regularly hook up are in the minority, this can’t always be assumed. Like water in a pool, some people’s comfort levels are deeper than others, and sexual activity can mean something different for everyone. Do you both have the emotional capacity for a hook up? (Read: are they okay with the fact that you’re also hooking up with their roommate?) While this discussion can be awkward as well, avoiding eye contact despite living on the same floor AND tak ing the same classes will always be worse. Even if you play it safe by only hooking up with people you don’t regularly associate with, clarifying expectations will make your experience more enjoyable for everyone.

When you think about it, sex is a lot like swimming: no one is born knowing how to do it, but if everyone is on the same page, it can be a lot of fun! And if you’re unpre pared, you’ll drown.

Erin Ritter '24 studies in the College of Arts & Sciences. She can be reached at e.h.ritter@wustl.edu

It is always better to be awkward than risk overstepping boundaries or hurting someone.

It wasn’t until this declaration in 1999 that UN explicitly acknowledged water as a universal right.

Was this simply too obvious to be put into words before? It’s the opposite, actually. We may intuitively accept water to be a right, but it is also a resource. When it comes to such, we take for granted that the nation-state gets to decide how to use their resources within their jurisdiction, as they see fit, even if said use is inequitable across the globe. Just as Russia is not obligated to provide oil to Germany and the U.S. is not obligated to provide grain to Somalia, the UN has no power to enforce this non-binding resolution.

De facto, water is not a universal right. Instead, political institutions use their control over water as a tool of authority over populations both within and without. That is their right.

In that sense, water can be a weapon. And all too many have used it as such.

Flooding as a battlefield tactic is usually equal parts uncontrollable and ineffective. The Dutch have for centuries relied on the intentional destruction of dikes for defense, but neither the Spaniards in the Eighty Years’ War or the Germans in WWII were deterred (though efforts against the former left regions inundated for a century). In 1938, the Chinese Nationalists released the Yellow River against the invading Japanese, only to result in over 800,000 casualties and the fall of Wuhan anyways. However, there is a modern example

of a nation deliberately flooding as an effective territorial tool, despite their now defunct status as a state.

At its peak in early 2015, the Islamic State (IS) controlled large swathes of Syria and Northern Iraq — including many crucial dams along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. These dams became weapons in their hands; for example, in April 2014, IS closed the Falluja Dam flood gates, submerging the town of Abu Gharib and 200 square kilometers of farmland to repel upstream Iraqi forces. However, this wasn’t the worst that IS could have inflicted. The capture of the Mosul Dam in August 2014, though only held for a few days, gave IS the power to poten tially inundate the cities of Mosul and Baghdad. An estimated 500,000 people would have died.

Yet, IS’s tactics also reveal water's double-edged nature as a tool of governance. Consider the Tabqa Dam in Syria. Under IS administration, the water in the Lake Assad reservoir was diverted to occupied regions, while simultaneously squeezing the water supplies of downstream Al Rakka and Aleppo. The flip side of this coin was that IS also increased hydroelectric output. Under former Free Syrian Army (an umbrella name for various Syrian rebels) control, electric power was only produced for an hour a day. IS at one point provided power for all 24.

This policy created surreal contradictions in the dynamics of the Syrian Civil War. The Assad government,

IS’s sworn enemy, was forced to pay ransom to maintain power and pay the dam operators’ salaries. Regions under drought were supplied water by IS, while IS artificially created droughts elsewhere. However, these contradictions are part of the IS’s unique strategy among Islamist militant groups: to establish their legitimacy as a caliphate, as a political state, by effec tively demarcating between constituents and non-constituents for which they have a (non) responsibility to provide basic services.

That responsibility is as fickle as the borders that divide them — and not just for IS’s quasi-state. For example, throughout the Syrian Civil War, Aleppo has suffered from similar tactics at the hands of the Assad government and various rebel groups, who all have withheld water to lay siege to the city, depending on which was occu pying it at the time.

We don’t have to stay in the Middle East, either. Take, for example, Crimea. When Russia seized the territory in 2014, the Ukranian government ordered the construction of a makeshift dam to cut off the flow of water from the Dnieper River through the North Crimean Canal, which supplies 85% of the peninsula’s water. Even Ukraine’s top irrigation official protested the decision, warning of a “humanitarian catastro phe,” but the Geneva Convention actu ally takes a side here: provid

ing for basic services is the occupiers’ respon sibility. This was the crux of the Ukranian government’s dare: if you want to claim Crimea to be Russian, then take care of your own citi zens. That is, if you can.

And to Russia’s credit (as weird as it is to admit this), they spent tens of billions of dollars on var ious infrastructure projects, including a 12-mile bridge linked to the Russian mainland so that water could be trucked across the country and multi-million dollar aquifer projects. However, these solutions’ effectiveness are in question as the aquifers are increasingly tainted by salt without replenishment from the river. While shoddy pipelines burst and dead-on-arrival moonshot projects such as desalination plants and cloud-seeding planes were abandoned, agriculture was nearly wiped out and residents had to make do with what one described as “brandy-colored” water.

Many in the world — even the residents them selves — would still call them Ukrainian. But in the end, it was Kyiv that built that dam, and in the first days of the broader invasion, the Russian army that brought it down. In the eyes of a detached world, the difference between cit izens and non-citizens is the same as the differ ence between a tragedy and a means to an end.

This dissociation between the governing and the governed allows water to be wielded as a geopolitical weapon, rationalized by the for mer at the expense of the latter. For Crimea, it was the severing border that allowed Kyiv to abandon its social mandate. For the Bolivians shot and arrested by government troops in the Cochabamba Water War, that dissociation was shaped by capitalist globalism.

For much of Latin America, the 1980s was the “lost decade”, thrown into chaos by defaults on foreign debt and the resultant recessions. At the time, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and the U.S. Federal Reserve stepped in to renegotiate and ultimately arrange the forgiveness of much of these loans. The catch was “structural

adjustment”: indebted countries had to open up to foreign investment and the privatization of state firms. In the case of Bolivia’s state water system (SEMPA), only foreign investors would have the capital to improve utility infrastructure, and treating water as a monetizable good will incentivize sustainable consumption. So the argument went.

Eventually, in 1999, the Bolivian government acquiesced after the World Bank threatened to deny further debt relief, opening SEMPA up to privatization. The only contract bidder was Aguas del Tunari, a consortium of international firms led by Bechtel, an American construction company. An agreement was only reached with certain preconditions: Aguas del Tunari would hold a monopoly over water supply and service in Cochabamba, be guaranteed a 15% return on investment, and would work to finish construct ing the Misicuni Dam, local mayor Manfred Reyes Villa’s vanity project that the World Bank had actually written off as uneconomic.

Political institutions use their control over water as a tool of authority over populations both within and without. That is their right.

At this point, you can predict how this all turned out. Rates were raised by more than 100%, protests arose, martial law was declared, and innocents were shot. I will dwell on this later. What I want to call out now is, when the Bolivian government finally caved in, how quickly the various political actors distanced themselves. The Bolivian government terminated the con tract on the grounds of Aguas del Tunari having abandoned it when executives fled the violence.

Mayor Reyes Villa had already abandoned sup port for the project several weeks earlier. Aguas del Tunari demanded $25 million compensation, blaming Bolivia for

breaking the terms — it wasn’t until 2006 that trade courts ruled against paying a single penny.

As for the World Bank, let’s just note that when protests against similar policy arose in El Alto, a World Bank official blamed native Andean con sumption habits — implying that they weren’t consuming enough to fulfill investors’ bottom lines.

That’s what all of these examples come down to, don’t they? In the tumult left behind by tenuous international law, constantly shifting geopolitics and principal-agent relationships, the question of who is responsible for meeting people’s basic needs is muddled. This is not to make a moral equivalence between the polit ical actors mentioned in this piece. (Probably should leave a disclaimer now: no, I don’t think Zelensky should be judged as harshly as the Islamic State.)

Nonetheless, within this ambiguity, in an attempt to seize control of situations spiraling beyond it, political institutions and entities tend to focus on what they can control. Troop deploy ments. Utility outputs. Financials. Numbers. After all, as the apocryphally attributed but forever influential quote goes, “The death of one man is a tragedy. The death of millions is a statistic.” Turns out you don’t have to be Stalin to fall into that line of thinking. You just have to have power over human lives to forget about them.

What convinced the Bolivian government to stand down wasn’t the effective hostage-tak ing in the form of debt dollars, or the exorbitant rates charged to their citizens, or the 50,000 people that rose in protest. It was the televised rifle of a Bolivian army captain, shooting seven teen-year-old Victor Hugo Daza in the face.

As citizens, when the very things that sus tain our lives are instead pointed against us as weapons by the political entities that manage them, we have to make that the world sees it as a tragedy. Not a statistic.

Jason Liu '23 studies in the Olin Business School. He can be reached at jliu1@wustl.edu.

When I was six or seven years old, I almost drowned and that is some thing I never got entirely over. It was so long ago that I can’t even begin to articulate every thought that seemed to flash through my head. It was an experience that I try hard not to remember, the only thing that I know was accu rately burned into my memory is the impossi bly slow fade to blackness that seemed to last for hours. Within that blackness fear took over and that fear was the only thing that I could focus on. I did not construct any plans about how to save myself, but instead a primal fear of something I couldn’t even comprehend began to invade me. Inside of that blackness, I didn’t quite get to my life flashing before my eyes but instead, I felt empty with a meek “is this it?” that could have either been due to being so young and having so few things to draw off of or a feel ing of helplessness in a current that consumed me. I was dragged out of the current in what was likely just a handful of minutes and I wish that fear had only consumed me in those brief, horri ble minutes but instead, the current had eroded who I was until just a compartmentalized ver sion remained.

A handful of years later, the Sandy Hook shoot ing happened. As a child freshly able to tie his shoes and having recently discovered frac tions, I watched news coverage about kids who looked just like me being subject to a random

act of violence. However, for an event that some remark as a turning point in American history, it all seemed so typical. More than that, I don’t remember feeling anything. Seeing the worst of what people can do and then watching as adults talk like enough was enough and a change had to be made was something I had become accus tomed to. Some might say I was just a jaded kid but then this exact type of thing happened six years later in Parkland, when I saw teenagers who looked like who I was then get caught in an act of violence. Then, this year in Uvalde, the cycle began anew.

In between these three events, more school shootings that weren’t deemed worthy of signif icant coverage and calls for reforms happened. Those reforms are still being mulled over right now and held up for reasons that feel drawn out of a hat. Still, knowing all of that, I think that feeling of apathy towards events so awful is something I can’t stop feeling ashamed of. I was too young to grasp it but it still grates on my soul and consciousness that I couldn’t muster any thing worthwhile to feel for those other kids that were just people on the TV to me. I also wanted to do something of note but that prospect and creating a tangible change felt entirely out of reach. I think that might be something a lot of other people who are reading this also feel.

After all those experiences stuck being submit ted to the worst of the world, I wish I could end with a perfect story about how I changed my mindset that then leads into an expertly con structed anecdote about how you can do the same. But I can’t do that. I still sometimes feel turned off to the bad and even horrific things that happen as a coping mechanism. But that is, after all, only some of the time. As I’ve got ten older, I have tried to work more on getting out and doing something, even if it seems like an infinitely small step. I had to learn how to be comfortable making these small steps with similarly slow, uneven progress. There was no light bulb moment but instead an ugly, labored process.

Going through with that made it so I can under stand how a person might feel like what they do has no chance of making a lasting differ ence. Climate change can feel like an existen tial threat, the stripping of women’s rights can feel dystopic and often it might feel like no one with the power to change these things really cares. Those are entirely rightful things to feel but I just want to say that you can try to be the difference. You can feel all those things you feel and not have to stuff it down to survive. If you really feel strongly about something that upsets you, I promise you there are plenty of people who want to change the world in the same way and have a place for you to start. Getting to that point though requires you to keep moving which can feel like an insurmountable task. If no one is going to tell you today, I can tell you that you can help make a difference.

Matthew Boyd ‘24 studies in the College of Arts & Sciences. He can be reached at bmatthew@wustl. edu.

"If you really feel strongly about something that upsets you, I promise you there are plenty of people who want to change the world in the same way and have a place for you to start."

When you buy a t-shirt, 713 gallons of water go down the drain. Now, multiply that by every t-shirt in your closet. Water is used at nearly every step of the garment production process. According to CNN, the fashion industry uses 21 trillion gal lons of water annually, which is enough water to fill 37 million Olympic-sized swimming pools. Crops like cotton require hundreds of gallons of water and use more insecticides and pesticides than any other crop in the world. In major man ufacturing cities like Savar, Bangladesh, water runs black with dye. The toxins in the water make it impotable and pose serious health challenges to the population living in the area. Additionally, textiles like polyester and nylon shed synthetic microplastics that end up in the ocean, where fish ingest the plastic. Then we eat those fish along with the microfibers of our old clothing inside them.

Fashion brands are starting to acknowledge their role in harming the environment and human health. This wake-up call is largely due to a growing consumer conscience for buying ethically and sustainably. Instead of attacking the problem at the beginning of the production cycle, however, many fashion brands are turning to greenwashing. As a marketing ploy, green washing falsely signals to buyers that a brand’s products are good for the environment, and it makes consumers believe they are doing more to help the environment than they actually are. In reality, the only thing that is getting cleaner is a consumer’s conscience.

Greenwashing has become such a customary business practice that it is hard to detect with the untrained eye. Even branding as simple as using green colors can make a customer believe that a company is concerned for the environ ment. Brands also use vague keywords like ‘sus tainable’ and ‘eco-friendly’ that are not backed up with any transparent information about the sourcing or production of the item. Take H&M for example, which released their “Conscious

Choice” collection with vague allusions to sustainability: the items must be made with “at least 50% of more sustainable materials.”

Nevermind that H&M is a fast fashion empire that churns out hundreds of other non-“sustain able” products weekly. Truly sustainable brands — and those that aspire to be — should be fully transparent about what their products contain.

Apart from the intentional vagueness surround ing a brand’s sustainability practices, green washing encourages consumers to buy more. Endless consumerism is antithetical to sustain able fashion because it encourages so much waste. Patagonia is a rare example of a brand that has encouraged its customers to not buy its products unless they actually need them. See their “Don’t Buy This Jacket” advertisement. Fast fashion brands that rotate through inven tory every two weeks encourage high levels of consumption by keeping trend-oriented cus tomers coming back for more. What happens to those clothes that you bought a year ago that are now completely out of style? They go in the trash, or to the thrift store if we are lucky. They are probably falling apart anyways; after all, most companies don’t produce clothes to last, they produce clothes to maximize profits.

As a society, we are becoming more aware of how our consumer practices are hastening envi ronmental decay. However, brands still manage to win us over with simple marketing schemes that are easy to poke holes through. When we see the word ‘sustainable,’ we feel like we can check that socially conscious box in our minds. But really this just makes our shopping habits

more palatable. Clothing cannot be split up into good and bad categories based on its environ mental impact. Yes, some textiles are worse for the environment than others, but they can all end up in landfills. For this reason, the real answer to sustainable fashion is buying less. When we buy less, we pollute less water and throw away less clothing. Buying less also means buying higher quality clothes that are built to last. Suddenly trends aren’t so import ant anymore.

Exiting the fashion consumer cycle is liberating. You can see the influence the fashion industry has on our behavior. It uses ever-evolving trends to make you think you always need something new. Then greenwashing comes in to make you feel okay about those purchases. This illu sion of care for the environment is dangerous and deceptive. Industry regulations on pro duction transparency and marketing need to be strengthened to encourage a more honest and truly sustainable industry. It is a dangerous game when consumers think they are solving fashion sustainability when, in reality, they con tinue to be part of the problem.

Jessie Wills ‘24 studies in the College of Arts & Sciences. She can be reached at j.l.wills@wustl.edu.

When we see the word ‘sustainable,’ we feel like we can check that socially conscious box in our minds.Emily Duran Garcia, Featured Writer Design by Eric Kim

t’s six in the morning when you receive the news. Groggily, you answer the unexpected phone call, frowning at the incessant and desperate buzzing. You sit up, rubbing at your eyes to chase the sleep away. All it takes is the single press of a button for your entire world to fall apart.

Perhaps that is not how you remember it. Maybe you were there to see it happen, or maybe someone gently grasped your hands and looked at you with teary eyes. But, you remem ber the pain, how grief slowly trickled into your chest until you could no longer breathe. It pulls you under, drowning you.

Grief is like water.

At first, it takes the form and strength of a tsu nami. It overwhelms the sky, taunting the last bits of peace you clutch onto tightly, until it suddenly crashes into the ground. It tears away at the foundations you’ve built and mercilessly wrenches you into its surging waters. You can not breathe; you cannot hear; you cannot see. All you know is that your arms and legs become numb to the cold that continues to pull you under. You start to wonder whether this is just a nightmare that you can’t seem to wake from.

You don’t know how long you’ve been underwa ter. Days? Weeks? Months? Even years?

You stare at the wall as you begin to drift deeper underwater. When was the last time you saw them? What did they say? Did you say “I love you” that time? Were they happy? Why weren’t you able to go see them? Why didn’t you take

that extra time to see them? Why didn’t you call them that night? Did they know that you wanted to see them again? Were they scared in those final moments? Were they loved?

You remember their smile and the way it used to warm you up. You remember the funny quirk they had that made you chuckle. You remember the texture of their hands that held you when you were frightened. You remember their voice that soothed your worries away. Your mind becomes a broken record of memories as it flits through all the joys they brought you. It must be a joke, albeit one in poor taste, you reason with yourself. They’re still here, sitting on the worn out couch, waiting for you to come home. They’re still humming their favorite song under their breath as they cook. They’re still tuning in every day to watch the old-timey show they’ve raved to you about. You want to stay there, in the delusion that they’re still here with you. You want to cry and scream, but you find yourself unable to lift a finger, much less get out of bed.

You are unaware of the hand that grows closer to your floating form underwater.

Heaving for air, you grasp at the hand that pulls you out. They do not let go as you continue to tremble. With shaky breaths, you sit in silence as they caress your head, murmuring prayers and condolences under their breath. They are your sister, your brother, your aunt, your pastor, or even your neighbor, but it doesn’t matter. You become painfully aware of the coarse cotton of their clothes underneath your clammy hands. “I’m so sorry,” they whisper. You remember their smile, now tight lipped, and their voice,

now silent, sealed and stuffed inside a lifeless box. The warmth of the delusion you were under drips away, leaving the cold reality to seep in. A familiar feeling starts to settle in your chest, and you scream.

Soon, it becomes like the tide. Some days, the tide is calm. You smile and laugh with the feel ing of water lingering behind you, until the water reaches out to you, much stronger than before. You freeze, wondering when the feeling would go away. People assure you that eventually, one fateful day in the far future, you will learn to let it go, but, as you stand in front of their grave, fingers tracing over the wooden carving that is their name, it starts to rain. You wipe away the droplet running down your cheek, and the tsu nami takes form once more.

Instead of being under the constant warmth of the sun, you remain surrounded by water. Some days it's like the tide; some days it’s like the tsunami; some days you are underwater. But, you learn how to swim as the water constantly changes and shifts. You learn to keep your head above water. But the water will remain clinging onto your form as days go by. You accept the reality that the promised fateful day in the far future will never come. You simply learn to fol low the crashing rhythm of the waves of grief.

In your heart, mind, and memories — it stays.

Emily Duran Garcia ‘24 studies in the College of Arts & Sciences. She can be reached at durangarcia.e@ wustl.edu

The seventeen floodgates of the Bull Shoals Dam stand for flood control, hydroelectric power, and recreation. It took two-hundred and fifty-six feet of concrete and the loss of a local cemetery to build their imposing frame.

A feat of reason overtook the turbulent, dangerous river. The once-wild water moves neatly below a bridge while cars cruise smoothly to their next destination. Their tires trace the gray lines we drew over blue.

There’s a body of water that remains unscathed by the desire to harness fluidity.

In the name of energy production, The Army Corps of Engineers proposed the construction of two dams on the Buffalo River.

It had been done before. It could be done again. And again. But not here, not on the waters that would become our first national river.

The river doesn’t need our protection. Doesn’t need a title or our discretion. Doesn’t need us to see value in floatable depths or jumpable cliffs.

We don’t let the river do anything. We may have control over concrete and engineering, but we still lack control over water.

This summer, a man drowned in flood-stage waters.

When the river reaches such levels, things start to disappear roads, bridges, bodies, stories.

Clabber Creek knows the Buffalo River. And at the meeting point of rock-littered sand and Clabber’s peaceful creekwater, sits farmland. Acres lovingly populated with tomatoes, blackberries, green squash, corn, and zinnias. Farming happens in tandem with the water’s song, whose rhythm depends on how much it has rained.

When the creek runs high, you hear the liquid collisions with solid rock. The music is an invitation to swim and rest. On scorching hot Arkansan days, 4pm is Creek Time. You revel in the flow of water around your burning skin and thank whatever powers you believe in for this place.

When the creek runs low, it barely moves at all. You have to lean in to listen. Still, you strain to hear any water at all. The creek sits still and so does the sky. The clouds are empty and the grass is tired of waiting, turning yellow with impatient thirst.

Two summers ago, you never thought about rain. Now, you think about it every time you see the tomatoes shriveling and the indigo struggling to grow. You watch a man rotate garden sprinklers every fifteen minutes, getting up in the middle of dinner to shift the water from the corn to the hibiscus. It’s not enough. You need rain. There’s only so much a man and a sprinkler can do.

You ask the clouds to open their floodgates.

Gabriela Martínez ‘23 studies in the College of Arts & Sciences. She can be reached at gabimartinez@wustl.edu.

In the last two decades, a combination of fac tors have pushed the student debt crisis to a critical point of unsustainability. Therefore, canceling student debt, while not perfect, is necessary to provide immediate relief to mil lions of Americans and buy policy makers time to enact legislation to truly solve the crisis.

During my senior year of high school, my inbox was perpetually clogged with notifications of scholarships and financial aid opportunities. Every hour, I would feel my phone buzzing with new messages, pulling me from my schoolwork. I was often annoyed at the constant barrage of emails, but then I would always remind myself that every dollar counts. And, when considering the amount of student debt in the United States, this phrase could not be more true. According to the most recent estimates from the Federal Reserve, U.S. student debt totals $1.75 trillion, which is higher than both medical and auto debt.

To address this crisis, on August 24, President Joe Biden announced his plan to provide stu dent loan relief by canceling debt for millions of Americans. Biden’s plan sent shockwaves around the country — some lauded it as a gift to the middle-class, while others criticized it for its recklessness. Given the widespread debate over debt cancellation and Biden’s proposal, a closer look into the student debt crisis is warranted.

Student debt in the U.S. was not always an emergency. Only within the past two decades has the cost of higher education exponen tially grown. According to the Bipartisan Policy Center, between 2007 and 2020, student debt increased by 144% from $642 billion to $1.56 trillion. So, what is driving this massive growth?

A combination of factors have led to this point, the first being a lack of state funding towards public universities. Within the last decade, the responsibility for public university funding has

shifted away from the states and towards stu dents. According to the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO), the average student contribution towards public four-year university revenues was 53.2%. While critics argue that state funding towards public institutions has increased in the past decade, per-student funding has decreased, leading to higher tuition costs for all.

Additionally, the 4.5% growth in university funding during the 2021 fiscal year was driven by federal stimulus money and is unlikely to continue in the long-run. According to SHEEO, if between 2020 and 2021 full-time student enrollment had not declined and federal stim ulus money had not been provided (in effect, if there was no pandemic or recession), total university funding would have decreased by 1%, suggesting that long-term growth is unlikely to occur. Thus, the lack of state funding in pub lic universities has led to students bearing the brunt of the financial burden.

The rise in student debt is also attributed to the high demand for elite university edu cation. According to the National Student Clearinghouse, during the pandemic, universi ties with less than 50% acceptance rates expe rienced growth in their class sizes, with public universities experiencing a 4.5% increase and private universities experiencing a 12% increase. These metrics indicate that the demand for elite universities is so high that even a recession can

not diminish it. As a result, institutions have lit tle incentive to lower their tuition, causing more students to take out loans.

The surge in popularity of for-profit universities has led to a dramatic increase in student debt. Unlike non-profit colleges which are required to invest their profits into the institution, forprofit colleges are under no such obligations. Consequently, these universities, such as DeVry University and the University of Phoenix, prior itize financial gain, often at the expense of their students. As a result, students who attend these institutions are more likely to have student debt and be ill-equipped to pay it off, causing total student debt in the U.S. to increase.

For example, a study published in the Journal of Financial Economics found that between 2000 and 2010 (during which for-profit enrollment was at an all-time high) student debt rose by 66%. According to the same report, in 2012, 39% of all federal student loan defaults were among those who graduated from for-profit universities. Moreover, according to the Student Borrower Protection Center, for-profit institu tions disproportionately target communities of color, exacerbating racial inequity. Thus, as more students get scammed into attending forprofit universities, student debt will increase.

Finally, the sheer number of people attending undergraduate and graduate schools means more people are taking out loans. According to the Education Data Initiative, between 1960 and 2022, the rate of college enrollment increased by 46.8%, meaning more students than ever are borrowing money.

So, how does Biden’s student debt relief plan factor into this situation? Biden’s plan has three main objectives: cancel federal student debt, make the student loan system more manage able, and reduce the cost of college.

Biden’s student debt relief plan is truly revolutionary – it extends the hand of government further into the economy than ever before.

Americans who will benefit from debt cancel lation include Pell Grant recipients, individuals who make less than $125,000 per year, and couples who make less than $250,000 per year. Pell Grant recipients will receive up to $20,000 in debt relief while other borrowers will receive up to $10,000 in relief. According to the Biden administration’s estimates, if all borrowers claim the relief to which they are entitled, 43 million families will see a portion of their stu dent debt canceled, while approximately 20 million will see their full balances eliminated.

To help borrowers pay off their student loans, the administration plans to cap monthly pay ments for undergraduate loans to 5% of a borrower’s discretionary income, as opposed to 10%. Additionally, the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program will be revitalized, ensuring those who participate in public service receive credit towards loan forgiveness.

Probably the most overlooked section of the Biden administration’s plan is its provision to decrease the cost of higher education. Recently, the Department of Education “terminated col lege accreditors” that allowed universities (typ ically for-profit ones) to defraud their students and Biden has vowed to protect student bor rowers from high costs. However, beyond these steps, it is unclear how the administration plans to hold colleges accountable for raising their prices.

Despite the popularity of debt cancellation, Biden’s plan does not come without criti cism. One of the biggest critiques against the plan is the impact it could have on inflation. Republicans and some economists argue that canceling student debt will exacerbate inflation as borrowers will have more disposable income.

According to economists at Goldman Sachs, however, federal student debt cancellation will only have a marginal effect on inflation.

Unlike stimulus checks, which directly increase income, debt relief increases wealth, which is unlikely to spur spending in the same way. According to the Roosevelt Institute, during these past two years of recovery and uncer tainty, there has been little evidence to suggest that an increase in wealth leads to an increase in spending. Recent metrics from the Federal Reserve’s Distributional Financial Accounts also support these findings.

Additionally, under Biden’s plan, only 20 million Americans will have their student debt com pletely forgiven. The majority of borrowers will continue to have outstanding balances, which will offset any increase in inflation.

While it is unlikely that canceling student debt will negatively impact inflation, it will take its toll on the national debt. The Biden administration has not released estimates on how much stu dent debt cancellation would cost the federal government. However, most economists agree that it would add between $300 billion to $600 billion to the national debt. The danger of accu mulating such a high amount of debt is that it increases the risk of a country defaulting — or failing to pay — its debt. While the chance of the U.S. defaulting on its debt is extremely low, the Government Accountability Office has warned that current levels of federal spending are unsustainable and jeopardize the financial health of the country.

However, these potentially negative economic consequences pale in comparison to the dra matic social impacts debt cancellation will have. Debt relief eliminates barriers to higher education, which provides low-income individu als the opportunity to break the cycle of poverty and achieve economic stability. Moreover, debt cancellation is a crucial step towards addressing systemic racism.

Long-standing and institutionalized racial dis crimination in education, housing, and prop erty seizures has left Black families with less wealth than white families. As a result, Black students are more dependent on student loans. According to the Education Data Initiative, Black college graduates owe an average of $25,000 more in student loans than white college grad uates and are more likely to struggle to pay off their loans, which perpetuates the racial wealth gap. Therefore, Biden’s student debt relief plan will disproportionately help Black borrowers and advance racial equity.

Biden’s student debt plan is truly revolutionary — it extends the hand of government further into the economy than ever before. While some politicians and economists worry about this overreach, the reality is, the student debt crisis can not be solved without sweeping govern ment intervention. The proposed student debt relief plan is in no way a permanent solution, but it buys policymakers time to enact legislation to truly solve the crisis.

While Biden’s plan does have its flaws, it cru cially delivers on providing borrowers immedi ate relief. For too long, Americans have been struggling to balance their budgets under their crippling debt, and Biden’s student debt relief plan is the first step to effectively address this crisis.

Amrita Kulkarni ‘26 studies in the College of Arts & Sciences. She can be reached at a.kulkarni@wustl. edu.

Peter Thiel: He’s the Elon Musk of the right. Such a designation is irrelevant now, considering the obsequious bil lionaire Musk has joined forces with the right as well. Nevertheless, I wish not to harp on Mr. Musk. Instead, I find it pertinent to recount and analyze the actions of Peter Thiel as long as we are living in this era. A relatively obscure figure when compared to his fellow tech tycoons, Mr. Thiel is somewhat of an enigma. The co-founder of PayPal does not post on Twitter and is sel dom in the news. Not only has that allowed him to go mostly unnoticed, but he has also been able to influence the American political land scape, making friends in the halls of Congress and funding his acolytes in key races with little noise.

Thiel’s start in politics began as an undergradu ate at Stanford University, where he founded a publication that placed himself and like-minded students in the intensifying culture war. As he rose in the technology sector to become a Silicon Valley tycoon, his political beliefs began to raise eyebrows. In a 2009 essay, arguing in favor of monopolies, he wrote that he “no longer believe[d] that capitalism and democracy are compatible.” Such views — at least the former — come into conflict with his newfound distaste for Big Tech.

While suspicion for Big Tech has become fash ionable among conservatives in recent years,

Thiel has been able to influence the American political landscape, making friends in the halls of Congress and funding his acolytes in key races with little noise.

few have harped on it as much as Thiel. Formerly a member of Facebook’s board of directors, Thiel left in 2019 and has since become increas ingly critical of Big Tech. “The consensus view is again, that it is about large centralization, Google, Google-like governments, that control all the world’s information, in this super central ized way,” Thiel said in a 2021 interview. “Silicon Valley is probably way too enamored of AI, not just for technological reasons, but also because it expresses this left-wing centralized zeitgeist.”

The roots of Theil’s vendetta can be traced back to 2007, when Gawker published an article with the headline “Peter Thiel is totally gay, people.” While the article was a combination of disdain for venture capitalist culture that catered to straight white men and praise for Thiel’s suc cess in a sector of the economy that famously shied away from LGBT-run business ventures, the Silicon Valley magnate was furious that he had been outed. A decade later, Hulk Hogan’s sex tape was leaked, and the wrestler, funded by Thiel, filed a lawsuit that would bankrupt the publication. Thiel insisted that the suit was first and foremost a matter of an individual’s right to privacy. While such a view should not be dis missed without consideration, it is especially ironic that Thiel, who claims to be launching a war for free speech and privacy, has aligned himself with the most authoritarian elements of the Republican Party.

His most recent protégé (and former employee), the Trump-endorsed GOP nominee for Arizona’s Senate seat, Blake Masters, has received over $10 million from PACs backed by Thiel. Like his former boss, Masters is a critic of Big Tech, regularly lambasting platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Google, claiming they are unfairly targeting conservative voices while catering to “the radical left”, and attacking free speech and privacy in the process. However, there is a blind spot in Masters’

outlook: he is no defender of these principles. In a tweet from May 7th, Masters all but stated that Griswold v. Connecticut — which estab lished the right to purchase and use contracep tion on the basis of privacy — was an overreach by the Supreme Court, which had, in his words, “made up a constitutional right to achieve a political outcome.”

While views such as this are finding newfound popularity on the right, they are not the primary stances that made the Thiel acolyte appealing to so many conservatives, including Donald Trump. Like many conservatives, Masters has made unsubstantiated claims of election fraud. “I think Trump won in 2020,” he stated in a YouTube video. He has embraced a range of explanations for why the former president lost, including ballot harvesting, last-minute changes to election laws in swing states, and Big Tech censorship. Each assertion has gained traction among right-wing circles since 2020.

What sets Masters apart from older Republicans is his attunement to the New Right. A burgeoning conservative movement with a large online presence, the New Right is rapidly gaining adherents among the GOP rank-andfile. The New Right, at least to some extent, chafes at the ideas embraced by so-called RINOs (“Republicans In Name Only”). Viewing figures like Mitt Romney and Mitch McConnell as part of a bygone era, its members somewhat eschew traditional conservative talking points such as free-market economics and govern ment downsizing, hoping instead to inflame the raging culture war. Their motivation to fight the latter is based on a combination of America’s glorified past and grievances pertaining to what they view as the country’s economic, social, and moral decay.

Masters’ campaign is a perfect microcosm of the movement he represents. Tall, slim, and just 35 years old, Masters bears little, if any,

The Thiel protégé’s plans for Social Security should concern every American, but pale in comparison to the assault on freedom that has become a crucial tenet of his campaign.

resemblance to the “Country Club Republicans” who used to make up the rank-and-file of the party and continue to comprise much of its donor base. An incessant poster on Twitter and Instagram, he has used the platforms to dissem inate his message, a combination of populist economic nationalism, extreme social conser vatism, and disdain for political correctness. His campaign announcement video laments glo balization, Big Tech, and Critical Race Theory, saying that “the country [he] grew up in was optimistic. People thought all you had to do was go to school and work hard. You’d be able to buy a house and raise a family, but it hasn’t worked out that way”.

Masters is right to criticize the political class for its inability to minimize the effects of glo balization, including deindustrialization, a decline in living standards, and rising wealth inequality. However, he has also demonstrated a willingness to attack the same downtrod den Americans he claims to represent. His plans to privatize water and Social Security, while extreme, do not deviate from Republican orthodoxy. In this sense, he is a standard GOP candidate.

Master’s plans for Social Security should con cern every American, but it pales in comparison to the assault on freedom that has become a crucial tenet of his campaign. Radically antichoice, Masters has gone further than most

“moderate” Republicans in his rhetoric. In addition to celebrating the overturning of Roe v. Wade, he has called abortion “demonic,” advocated for a national ban on abortion, lent his support to Arizona’s 15-week ban (with no exceptions for rape and incest), and backed a fetal personhood bill.

None of these views on a woman’s right to choose conform with the libertarianism to which Thiel and Masters formerly subscribed. Even more worryingly, Masters has flirted with the “Great Replacement Theory,” a far-right conspiracy theory that warns of forced demo graphic changes through mass immigration that will ultimately produce a majority-minority country. The theory’s proponents maintain that all of this will be brought about by cultural and political elites intent on destroying America and its way of life.

Granted, the version of the conspiracy theory Masters promotes is sanitized in that it contains fewer references to George Soros and the white race specifically, but it is nonetheless concern ing. Masters has accused the Democratic Party of trying to change the ethnic composition of the country as part of its larger plan to achieve a permanent hold on power. The alleged plan is simple: provide amnesty to illegal immigrants and use their votes to win elections.

While the most notable among his cohort, Masters is not the only GOP candidate hop ing to ride an anti-immigrant wave to victory. Ohio’s J.D. Vance, who is also Trump-endorsed and Thiel-funded, has used similar rhetoric in his race. In a television ad, Vance accused Joe Biden of implementing an open borders policy that allowed fentanyl and illegal immigrants, whom he referred to as “Democrat voters,” to pour into the country. In an interview with Gateway Pundit, Vance asked, “If you wanted to kill a bunch of MAGA voters in the middle of the heartland, how better than to target them and

their kids with this deadly fentanyl?”

Vance’s rhetoric is less extreme than that of his Arizona counterpart, but the Thiel acolytes are both propagating the same idea: Unless some one stops Joe Biden and the left, they’ll use their power to bring about demographic changes and marginalize white Americans. Both candidates, as well as others funded by Thiel, are using a combination of economic populism and farright talking points on immigration to justify a brand of authoritarian politics that defines the New Right.

To understand this movement and the political hopefuls representing it, one must understand Thiel. Like those he is funding, Thiel’s public persona is that of a culture warrior launching a crusade against liberal bodies, namely cor porations and governing institutions, and the social and political agenda that they purvey. The image he and his acolytes have crafted of them selves, however, is a trojan horse for an agenda that combines the GOP’s traditional eagerness to dismantle popular government programs with reactionary and far-right positions on social issues as well as an increasingly obvious authoritarianism.

Gabriel Squitieri ‘23 studies in the College of Arts & Sciences and can be reached at gabriel.s@wustl.edu.

Though the candidates change, every election cycle the American people hear the same refrains: complaints about “gridlock” in Washington and promises to break through and deliver substantive changes. And yet, year after year, substantive legisla tion has largely eluded both presidents and Congress. However, after a string of legislative victories this summer, perhaps President Biden has developed a model for producing results: sincerely reach across the aisle, but if necessary, go at it alone and get things done.

Indeed, Biden articulated such a vision

throughout the 2020 campaign. As a candidate, more than anything else, and more than any singular policy initiative or legislative agenda, Joe Biden promised to “restore the soul of the nation.” Biden cast himself as a steady hand, righting the ship after four years of riding the rough seas. He also played up his centrist credentials, a Washington veteran looking to restore the era of gladhanding and dealmaking that had proved illusive in the age of increasing partisanship.

However, while this commitment to restore nor malcy to the presidency was unquestionably

the prevailing drive of the Biden campaign, it was far from the only promise Biden made as a candidate. Evoking FDR during his speech at the Democratic National Convention, Biden prom ised to pursue a litany of liberal policy goals from vastly expanding the social safety net and investing heavily in sustainable energy to stu dent loan forgiveness.

During the campaign, these dueling promises, centrist certainty and liberal reform, served candidate Biden well. Forming a coalition of pro gressives, independents, and some Republicans, Biden secured the presidency, earning the most

Biden’s theory has been vindicated: Work across the aisle whenever possible, but don’t be afraid of doing it alone.

votes ever by a presidential candidate. While these campaign commitments certainly broad ened Biden’s electoral appeal, they have made Biden’s job governing all the more difficult.

To progressives, Biden’s presidency was the best chance to enact meaningful, transformative change. Anything short would be squandering a great opportunity. To moderates and inde pendents, Biden’s election was not a mandate for transformative change, but rather a rebuke of the chaotic Trump years. As Representative Abigail Spanberger (D-VA) told the New York Times, “Nobody elected [Biden] to be F.D.R., they elected him to be normal and stop the chaos.”

Almost inevitably, every action he took would surely upset a portion of Biden’s electorate. As the first year of Biden’s presidency unfolded, the American people watched these compli cated dynamics play out in real-time. When Democrats passed the American Rescue Plan by a party-line vote, Republicans derided Biden as just another partisan Democrat. Later that year, when Biden appeared dead set on reaching a bipartisan deal on infrastructure investments, some Democrats grumbled that negotiating with Republicans was a fool's errand.

And yet, though it has taken time to come to fruition, perhaps Biden’s theory has been vin dicated: work in a bipartisan fashion whenever possible, but don’t be afraid of doing it alone. Over the past year and a half, Biden has walked this legislative tightrope on his way to a litany of legislative wins.

On the one hand, Biden has not shied away from encouraging Democratic colleagues to ram bills past unified Republican opposition. At Biden’s urging, Congressional Democrats passed The American Rescue Plan, delivering much-needed relief to struggling families. This summer,

Democrats passed the Inflation Reduction Act, lowering the cost of prescription drugs, making the largest-ever investment in clean energy, and extending health insurance subsidies under the Affordable Care Act. While, of course, progres sives wish that these bills had gone even further, they represent substantial moves forwarding the Democratic agenda.

Perhaps more impressive, however, has been Biden’s ability to work across the aisle and deliver Republican votes for substantial legislation. Last year, 17 Senate Republicans, including Minority Leader Mitch McConnell joined Democrats in passing the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, an investment of a trillion dollars in improving our nation’s infrastructure. This summer, Biden’s bipartisan streak kicked into high gear. The most consequential gun safety bill in almost three decades. Funding that will invest in semi conductor chip manufacturing and help the U.S. compete with China. Expanding VA benefits to veterans exposed to burn pits. All of these bills passed with significant bipartisan support.

Of course, the President’s penchant for deal making should not come as a surprise. This President is a 36-year veteran of the Senate, who made a career forging friendships across the aisle. Indeed, he often reminisces, almost whimsically, about his Senate days when he’d “fight like hell” with segregationists, but then

go to lunch with them. As Vice President, Biden was often dispatched to Capitol Hill to bargain with McConnell, a task that President Obama seemed to loathe, but one that Biden relished. Needless to say, working across the aisle is truly at the core of Biden’s political identity, and as president, it has resulted in several victories for the American people.