Print Editor-in-Chief Lauren Heberlee

Print Managing Editor Samie Travis

theblackandwhite.net

Print Managing Editor Simone Meyer

Print Production Head Maya Wiese

Online Editor-in-Chief

Ethan Schenker Online Managing Editors

Stephanie Solomon, Sonya Rashkovan Online Production Head

Vassili Prokopenko Online Production Assistants

Cameron Newell, Eliza Raphael, Duy Bui, Adam Giesecke Print Production Managing Assistants

Gaby Hodor, Elizabeth Dorokhina Print Production Assistants

Mary Rodriguez, Eva Sola-Sole Photo Director Rohin Dahiya Photo Assistants

Katherine Teitelbaum, Ava Ohana, Charlotte Horn, Heidi Thalman, Sally Esquith, Navin Davoodi Communications and Social Media Directors

Alex Weinstein, Norah Rothman Puzzles Editors

Elena Kotschoubey, Cameron Newell Business Managers

Sari Alexander, Sean Cunniff Business Assistants

Alanna Singer, Aditte Parasher, Greta Berglund, Marissa Rancilio Webmaster Sari Alexander

Sophie Hummel, Christopher Landy Traffic Manager Aditte Parasher Feature Editors

Norah Rothman, Kiara Pearce News Editors

Samantha Wang, Jamie Forman Opinion Editors

William Hallward-Driemeier, Eliana Joftus, Zach Poe Sports Editors

Gibson Hirt, Zach Rice, Alex Weinstein Feature Writers

Emily Weiss, Josefina Masjuan, Caroline Reichert, Grace Roddy, Kate Rodriguez, Sydney Merlo, Dani Klein, Marissa Rancilio, Manuela Montoya, Louisa Ralston, Scarlet Mann News Writers

Alessia Peddrazini, Jasper Lester, Greta Berglund, Ines Foscarini, Darby Infeld, Christopher Landy, Meredith Lee, Aidan Donnan, Harper Barnowski Opinion Writers

Maddie Kaltman, Sadie Goldberg, Jacob Cowan, Ava Faghani, Natalie Easley, Ian Cooper, Macie Slater, Ben Lammers, Lucia Gutierrez, Jacob Palo, Chloe Walker, Ethan Tucker Sports Writers

Faiyaad Kamal, Ellen Ford, Grace O’Halloran, Will Gunster, Diego Elorza, Asa Ostrow, Waleed Aslam Adviser

Ryan Derenberger

The Black & White (B&W) is an open forum for student views from Walt Whitman High School, 7100 Whittier Blvd., Bethesda, MD, 20817. The Black & White’s website is www.theblackandwhite.net.

The Black & White magazine is published six times a year. Signed opinion pieces reflect the positions of individual staff members and not necessarily the opinion of Walt Whitman High School or Montgomery County Public Schools. Unsigned editorial pieces reflect the opinion of the newspaper.

All content in the paper is reviewed to ensure that it meets the highest level of legal and ethical standards with respect to the material as libelous, obscene or invasive of

privacy. All corrections are posted on the website.

Recent awards include the 2019 CSPA Gold Crown, 2018 and 2017 CSPA Hybrid Silver Crowns, 2013 CSPA Gold Medalist and 2012 NSPA Online Pacemaker.

The Black & White encourages readers to submit opinions on relevant topics in the form of letters to the editor, which must be signed to be printed. Anonymity can be granted on request. The Black & White reserves the right to edit letters for content and space. Letters to the editor may be emailed to theblackandwhiteonline@gmail.com.

Annual mail subscriptions cost $35 ($120 for four-year subscription) and can be purchased through the online school store.

Creativity means more than the arts; it’s a beautiful and vulnerable way for us to interact with the world at large.

Our school has a reputation of competi tive academics and a high-stress environment, but that’s never been the best way to define us. Students have always and continue to move beyond the walls of Whitman to pursue their own unique outlets.

From immersing themselves in artistic experiences at the Yellow Barn Art Studio in Glen Echo, orienteering in new terrains, and discovering a nuanced approach to classic chick-flicks — students have found that they already have the keys to escape.

We chose to feature the local D.C. Mor mon Temple, which recently unlocked its doors to the public to settle the curiosity be hind the mysterious local landmark. We also

looked into the meaningful history and tasty menu of a famous D.C. restaurant, Ben’s Chili Bowl — a must-stop for anyone interested in understanding the role the community plays in discovering ourselves.

While it’s important to recognize and place emphasis on students’ passions and re nowned local sites, we must also highlight areas of improvement within our community. Whether it be the complex inner workings of Montgomery County’s Teachers’ Union or the negative stereotypes behind the local Green tree Shelter for boys, we can always bring new conversations to the podium that help us better understand both ourselves and others.

Addressing conflict is a critical skill need ed for that improvement to be effective and efficient. Two Whitman graduates found their voice bringing conflict to conclusion over their

four-year career on the debate team.

Creativity of all kinds empowers students to break out of the mold. We encourage stu dents and the community at large to leave their comfort zone in order to find new passions and a reprieve from the stress of their everyday lives.

As always, we thank our dedicated advisor Ryan Derenberger, driven writers, photojour nalists, editors, business team and digital and print production teams for portraying our in spiring student body and commencing Volume 61 of The Black & White. Enjoy exploring.

Best, Your editors

Early every Monday morning, history teacher Wendy Eagan flicked on the lights of her classroom, illuminating several world maps on the back wall, the esteemed Buddha at the doorway and countless other unique posters of cultures from around the world — artifacts she’d collected over her decades teaching at Whitman.

As students entered Eagan’s classroom, the “golden rule” would greet them: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” The proverb — which hung on a poster by the door and was the main message behind all of Eagan’s teaching — exists in similar forms across diverse cultures and religions. Eagan’s appreciation for “the golden rule” is one of the principal reasons she became a teacher, she said: to find what connects us.

Ever since she was a small child, Eagan knew that she wanted to pursue a career in edu cation. She studied at Northwestern University, where she double-majored in U.S. history and literature and minored in educational theology. At Whitman, Eagan transitioned to the front of the classroom, teaching U.S. History, U.S. Government and Politics, Ancient Mediterra nean History, AP European History, AP Mod ern World History, Comparative Religion and Sociology.

The variety in possible coursework and curriculum is exactly what drew Eagan to

teaching high school. She hoped to introduce students to unfamiliar topics and from there, let them develop their own interests, Eagan said.

“We all want to learn, we all want to grow, we’re all interested,” she said. “That, to me, is what high school is about: opening up, learn ing, growing, changing, new interests.”

Eagan focused on teaching critical think ing as much as teaching history itself. Analyti cal thinking is a key skill assessed on most AP tests, so it felt natural for Eagan to explore this through six themes of world history: human and environmental relations, cultural interac tions, governments, social interactions, eco nomic systems and technological innovations. The themes connect all homosapiens despite their origins, which is an idea that Eagan hopes that her students take them beyond the class room walls and apply in their everyday life, she said.

Senior Julia Wood saw Eagan’s skill as an educator firsthand in AP Modern World Histo ry. “She’s taught me the value of hard work,” Wood said. “She sets very high standards and pushes us hard to meet them.”

Many students are familiar with Eagan’s high expectations. She encouraged her classes to dive deep into the material and engage in the subject — preparing them for life after high school, Wood said.

“You can tell that she’s truly passionate

about history,” said Tomas Montoya (’22), who also took Eagan’s AP ‘World’ class. “She’s also one of the few teachers that takes time at the end of class periods to ask us about current events and our opinions on them.”

Eagan made a point not to shy away from analyzing current events in her classroom. To her, history was never complete without dis cussing the present. Eagan believes it was her responsibility as a teacher to keep her students up-to-date on the world around them, she said.

“One of the reasons social studies teachers tell you the reality, not sugarcoat it, is so that you’re aware of what’s going on around you,” Eagan said.

Montoya remembers Eagan for this partic ular passion and appreciated her commitment to educating students and spreading awareness about the broader world, including the invasion of Ukraine this year.

“She was very emotional about it and would often spend 10 to 15 minutes review ing articles and updating us with information,” Montoya said. “You can tell she really cares.”

Eagan also shared her love for traveling with many of her students, allowing them to learn about different cultures and languages across the globe. Through a program led by Whitman, Eagan has taken students on trips to Central and Eastern Europe.

“Everywhere I’ve traveled, I’ve run into

friendly, nice people, whether they’re adults or children,” Eagan said. “I think that’s what I like about people; just because somebody speaks a little differently or dresses a little differently, we’re all pretty similar.”

Eagan proved her reputation among staff as much as she did among students. Whitman staff looked to her for content knowledge and teaching advice.

History teacher Jacob East remembers Eagan being kind and welcoming when they were first introduced over the summer while preparing for the then upcoming school year. East was instantly inspired by her dedication, he said. Any time he runs into parents or alums, he fields questions about how Eagan is doing and watches their faces light up as they talk about her influence on Whitman.

“She’s made me a better teacher,” East said. “She’s expanded not just students’ knowl edge, but she’s enlightened me and has taught me — not just in subjects, but teaching meth odology. She doesn’t just teach students; she vicariously teaches teachers.”

Colin O’Brien, an Honors US History and AP U.S. Government and Politics teacher at Whitman, worked alongside Eagan for 18 years. Eagan never failed to inspire him, he said.

About 15 years ago, O’Brien created a pre sentation with Eagan that The National Coun cil for Social Studies selected to be featured at its San Diego conference. O’Brien and Eagan traveled to California where they delievered their presentation, which explored the three Abrahamic religions — Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

“We flew out there together, did the pre sentation and it went over really well,” O’Brien said. “It was a great learning experience for me, and I was so lucky to be able to work with her. I’m forever grateful for that opportunity.”

Just as O’Brien appreciated the chance to partner with Eagan, many other teachers recog nized her ability to thoughtfully collaborate as well. She always went out of her way to make others feel welcome. “Ms. Eagan is one of the most caring, kind and generous people that I’ve

had the pleasure of working with,” East said. “I consider her a good friend.”

Another one of Eagan’s unique traditions was getting gifts for her colleagues’ kids when ever they came to visit Whitman. East recalls his daughter Willow receiving a present from Eagan every year on Willow’s birthday.

Both East and O’Brien are grateful for the connections their children have developed with Eagan. Her years at Whitman have allowed her to watch them grow up, O’Brien said.

When the time came for Eagan to turn off the lights in her empty classroom this past school year, she hoped all of her students left her classes with curiosity and an urge to ex plore the world.

“There’s always going to be something out there you didn’t know yesterday that can excite you and intrigue you for tomorrow,” Ea gan said. “That’s my advice — get out of where you live and see other people because there’s a whole world of wonderful stuff out there. They may speak a different language, they may have a different culture, but we are the same.”

October 7th, 1988

October 7th, 1988

Names of the youth have been changed for their anonymity and safety

Lee entered the foster system at eightyears-old after his mother was deemed incapable of caring for him. He spent four years in foster care before a family adopt ed him in 2017. These major life changes left Lee whiplashed — he felt that he was consis tently being let down, he said.

In Nov. 2021, Lee moved into The Gre entree Adolescent Program (GAP) or The Residence. The GAP is a group home located in the Whitman dis trict created in 1973 to help male victims of trauma, abuse and neglect through in dividual and com munity support. The National Center for Children and Fam ilies (NCCF), open since 1914, runs the group home and other centers for disenfran chised children.

Following two incidents, one in 2019 and one in 2021, NCCF drew criticism from the community on online platforms such as NextDoor. In 2019, a Whitman student living at Greentree assaulted another student on Whitman’s campus, and in 2021, three individuals from Greentree were charged with the drug-related robbery and mur der of a 33-year-old male. The charges were dropped on one of the individuals.

Assistant Principal and former NCCF em ployee Gregory Miller hope the community will further the compassion it showed in the past to students at Greentree, he said.

“When I think about what we all can do to make any student feel more comfortable, I think about listening to their lived experienc es,” Miller said, “Not in a sense to just hear them, but to figure out how we can take that experience in order to create an environment where all students, staff members and people feel welcome.”

Division Manager of Adolescent Services and NCCF Administrator Omoré Okhomina helps to give a voice to all of the organization’s children and families under their care, includ

ing the GAP. The reputation of the program and public care systems as a whole must be addressed, Okhomina said.

“I think that there’s this stigma — it’s un fortunately the reality for young people who find themselves in the care of public systems,” Okhomina said. “I think people make a lot of assumptions about a young person when they are in a group home or in a program that is pro vided by the public services. The youth are the future regardless of where they come from.”

Greentree often hosts outings for the youth under their care with activities such as bowling

do I want to do for my future?” Callaghan said. “It’s the same for any student, no matter where they are placed.”

Students at Greentree each house their own plan for the future. Lee aspires to become an electrician. He wants to work hard to obtain his own apartment, income and friends, he said.

“There are good people at Greentree,” Lee said. “We’re not bad kids — the majority of us are just lost and don’t have anywhere to go.”

Despite their past traumas and differing backgrounds, almost all of the GAP youth at Whitman continue to strive to be the best ver sions of themselves, Lee and Okhomina said. The GAP youth want to urge everyone to try to put their “typical Bethesda life” in perspective and try to always look for the best in people.

“Greentree has giv en me an opportunity to go to one of the best schools,” Lee said, “I’m honored by that and I try to do the best I can.”

and Top Golf matches. They also hold “Tasty Tuesday” where local restaurants and families bring meals of different cultures for the resi dents to taste. The NCCF and local volunteers help organize all of the activities. The group home itself includes a gym, art room, mu sic room, movie room and several basketball courts.

Additionally, NCCF provides routine ther apy, offering both individual and group ses sions every week. Lee praised therapist “Ms. Emmy” for her guidance and soothing strat egies that help manage both typical teenage stress and past trauma.

Former Whitman social worker Emily Cal laghan also provided emotional support to the GAP youth in addition to the rest of the student body. Callaghan hopes that the community will be understanding of Greentree’s importance in the lives of individuals living and learning there, she said.

“Everyone here are adolescents, right? People have similar struggles: What are you going to wear? How do I fit in at school? What

Lee, along with oth er youths in the home, fear that people would assume he is capable of committing crimes or callous actions because others at Greentree were, he said. Lee requests that the Whitman community has an open mind to all of the other students like him living at the group home, he said.

Okhomina has witnessed the success sto ries of youth at Greentree firsthand. He knows that where the youth lives and their circum stances don’t define Greentree residents or limit their ability to accomplish future achieve ments, Okhomina said.

“Lots of young people are able to over come some unimaginable odds and make themselves successful, productive members of society, or young people who are in col lege,” Okhomina said. “We have young people who have gone on to start their own families; they’re parents now. “It’s great for community members to be educated to seek out informa tion rather than make assumptions — because these assumptions have real impacts on young people across the country.”

“THE YOUTH

THE FUTURE REGARDLESS OF WHERE THEY COME FROM.”

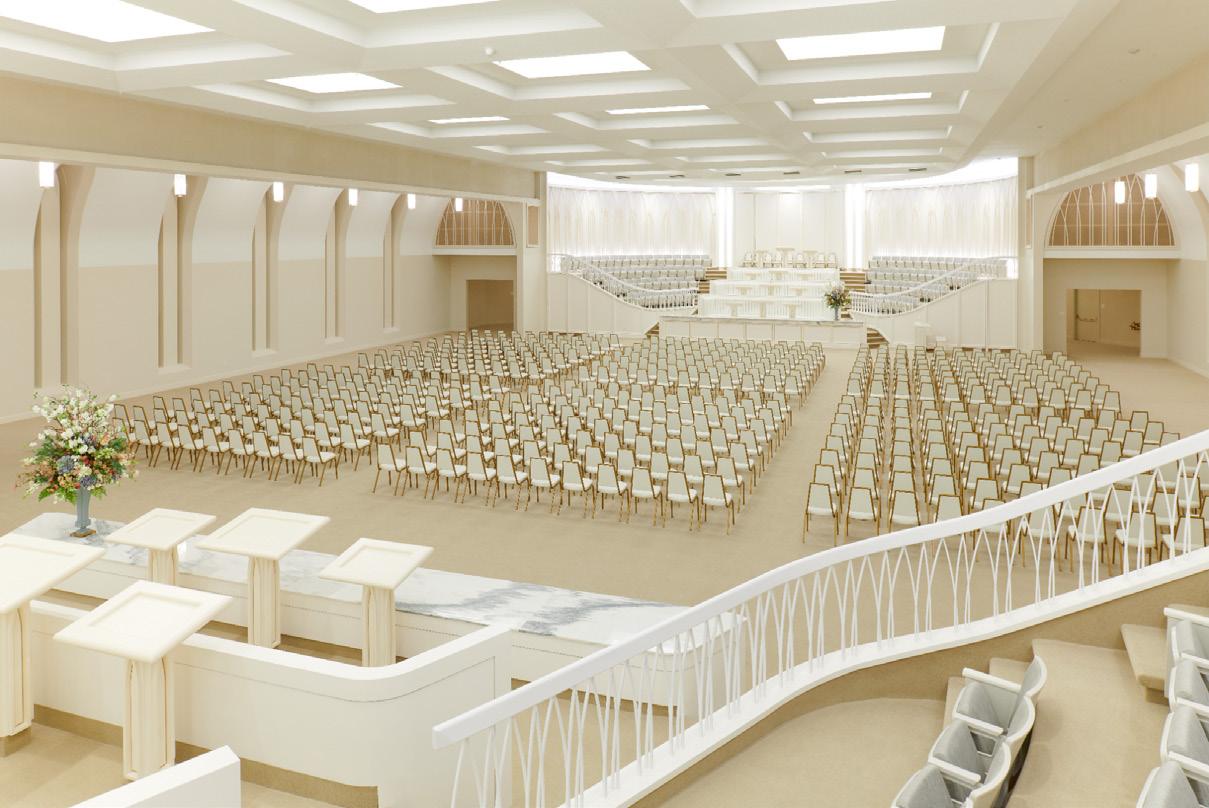

ommuters on the Capital Beltway know it well: the Washington D.C. Temple, with its white marble facade and two-ton gold Angel Moroni standing high above, gallantly blowing his trumpet.

This year, from April 28th to June 11th, the temple’s secrets were finally uncovered and the nearly 300-foot building, casually known in the area as “Maryland’s Disneyland,” unlocked its doors to the public for the first time in nearly 50 years.

The Washington D.C. Temple opened in 1974 for members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The Temple serves all Lat ter-day Saints, also known as Mormons, living east of Mississippi and in parts of South Amer ica and Canada. For members, the D.C. temple is the most sa cred place of worship on Earth, a place set apart from the rest of the world where members seek to grow their personal connec tion to God.

At Whitman, there are fewer than ten members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, reflecting its small Bethesda demographic and adding to the mystery of the religion within the community.

Most Latter-day Saint af filiates in the U.S. reside in Utah, with about 60% of the state’s population belonging to the church. Professor Paul Reeve, Simmons Chair of Mor mon Studies at The University of Utah, knows the history of Mormonism and the D.C. Tem ple well.

“The Washington D.C. Temple is unique because of its location on the beltway,” Reeve said, “The way it kind of emerg es seemingly hanging in the air so that it’s a recognizable icon in the D.C region.”

In March 2018, the temple closed for worship due to an extensive renovation, includ ing a replacement of the elec trical and mechanical systems. During this period of time, church staff allowed non-mem bers to enter and view the tem ple under construction. Follow ing its completion, the church hosted an open house for the public.

Every temple belonging to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints must endure a dedication ceremony after it is built or renovat ed. Dedicating a temple makes it sacred for the ordinances and covenants that take place there, symbolizing that they’re set aside as works of God. The ceremony includes a special prayer designating the building for church use and ask ing God to bless its structure and grounds. It’s a custom of the Latter-day Saint faith to hold a free open house before the temple’s dedication, or in this case rededication, to satisfy any curi

osities the public might have and demystify the church’s practices.

Right before stepping foot into the temple for this year’s tours, guests were given shoe coverings to maintain the floor’s new condition. Volunteers greeted the public as they crossed the threshold and provided them with a link to par ticipate in a self-guided tour. On the tour, guests traveled through six rooms and received a print ed summary of each room’s importance.

The first room on the tour was the baptistry. Visitors traveled up steep flights of stairs to a floor containing dressing rooms where members change from everyday clothing into all white upon entering the temple. The colorless apparel symbolizes the idea that all Latter-day Saints are

very meaningful to Latter-day Saints.

“We strongly believe that families are for ever and we’ll be sealed together through eterni ty,” said Washington D.C. Temple member Sue Hugley.

Afterward, visitors ventured into the in struction room, where members go to learn more about their relationship with God. Their final destination on the tour was the celestial room, where members go at the conclusion of their “endowment ordinance.” The endowment — a gift of sacred blessings from God to each member — is granted in a two-part ordinance ceremony designed for participants to become kings, queens, priests and priestesses in the af terlife. The celestial room is also a place of quiet reflection and a symbol of being in God’s presence or in heaven.

Many of the temple’s cur rent members were raised in the church by older relatives who worship. Most have been mem bers for a majority — if not the entirety — of their lives.

“It’s where we gain a com plete understanding of our pur pose in life,” member Ken Pe terson said, “what we’re here for, where we came from, where we’re going.”

Latter-day Saints’ temples don’t offer regular Sunday wor ship services. Instead, in hopes to increase turnout, church leaders hold services in separate meeting houses open to all faiths.

Members of any faith can attend and participate in worship, recreational events and social gatherings.

The D.C. Temple’s open house this year served a similar purpose, allowing non-members to delve even deeper into one of the most sacred spaces for Lat ter-day Saints — a rare opportu nity to gain a broader understand ing of the religion’s customs.

Many Whitman families took the opportunity to tour, including junior Caris Costigan, who was in awe upon entering the temple’s massive doors, she said.

equal before God.

The next room was the bride’s room — an area embellished with gold accents where brides wait prior to their marriage ceremonies. The faith’s most sacred ceremonies include marriag es and sealings, where a couple kneels across an altar and becomes bonded together for eternity, and are held in the sealing room. An altar sur rounded by a line of chairs for guests rests at the center of each sealing room.

Latter-day Saint sealings ensure that death cannot separate loved ones. Children born or adopted into such eternal marriages can also be sealed to their families forever, making sealings

“I grew up driving by the Temple and always wondered what it looked like inside,” Costi gan said. “When I finally saw it years later I was really surprised because it was completely dif ferent than what I imagined.”

Those who belong to the Church have wel comed outside visitors during this transition pe riod for that exact reason — they want people to better understand their religion.

“We want to invite others to come see and hopefully they can understand our faith a little better and what we do in the temple,” said D.C. Temple member Holly Peterson. “We want to share with others. It’s sacred, it’s not secret.”

Despite the pressure of needing to respond in mere seconds, So phia Polley-Fisanich (‘22) and Katheryne Dwyer (‘22) remain perfectly composed. The judge scores closely as the duo refutes attacks from the opposing team and shifts to the offensive.

For Polley-Fisanich and Dwyer, outside forces melt away when they’re debating together — teamwork is their only priority.

The pair have competed in the Whitman Public Forum Speech and Debate Club since their freshman year, though it wasn’t until their sophomore year that they became a team. After cycling through other partners, the duo first competed together at the Capitol Beltway Classic during the fall of 2019. Despite having lost this competition, they were immediately drawn to each other’s ambition and wanted to continue as a pair.

“We both knew that we had the drive to go a lot further than we did on that day,” Polley-Fisanich said. “Being committed to making the partnership work and working hard in the activity, we both developed the same mindset towards it.”

In an activity like debate, losing is inevitable. Even the top-ranked teams experience defeat because judging is subjective and rounds rarely go perfectly. Over the years, Dwyer has come to understand how crucial it is to accept defeat in debate, she said.

“Learning how to lose is a really important part of it,” Dwyer said. “You’re going to lose a lot and you have to deal with that.”

After that initial tournament, Polley-Fisanich and Dwyer went on to become one of the nation’s top-ranked teams. Over the course of their debate careers, they’ve accumulated 13 “gold bids” — achievements earned when debaters reach a specific round in a tournament — that qualified them for the Tournament of Champions, an exclusive and es teemed national stage.

Polley-Fisanich and Dwyer are not strangers to this debate success. From winning the Valley Mid-America Cup for two consecutive years and semifinaling in the Tournament of Champions in April of this year — the first all-female team to do so in the Gold Public Forum since 2018 — to reaching semifinal and final rounds in multiple invitational Round Robin tournaments, the duo has racked up plenty of accomplishments.

Polley-Fisanich and Dwyer have both earned leadership roles on the Whitman Debate Team as a Captain and Team President respectively. In her role as a Captain, Polley-Fisanich feels that her main job is to keep morale high, she said.

“I think that what leadership is meant to do is prevent the boat from rocking,” Polley-Fisanich said. “If it does rock, [we] make sure that ev eryone ends up happy at the end of the day because we’re a community, we’re a family and we have to make sure that we all succeed.”

Dwyer’s responsibilities as Debate Team President include hiring coaches, administering team elections and attending parent board meet ings.

“I’m meant to represent the student perspective,” Dwyer said. “[I] raise concerns that are on the students’ minds to the parent board so that they can deal with them as appropriate.”

While it might look effortless on the surface, Polley-Fisanich and Dwyer’s journey to the top has not been easy. As women, they have to deal with more than just fierce competition — they must manage the inherent sexism that follows them every step they take.

“When you’re a woman in a male-dominated activity, you become a more obvious target,” Polley-Fisanich said.

The pair has experienced sexism from fellow competitors and judg es and faced situations where debate results felt skewed because of gen der bias.

“Sometimes you lose rounds and the only thing the judge will say is that you sounded ‘hysterical’ or ‘too aggressive’ or any of those loaded words that are wrapped in misogyny,” Dwyer said.

To ease the pressure of competing in a male-dominated field, Dwyer works with Beyond Resolved, an organization originally founded as a space for women in debate to come together and share their experiences. Currently, she and other leaders are in the process of expanding to help all marginalized groups in the circuit like people of color, LGBTQIA+ members and low-income students.

Beyond Resolved has played a major role in Dwyer’s debate experi ence. During rough times, she’s been able to lean on the people she met through the organization, Dwyer said. These relationships proved to be critical since prejudice still plagues many areas of the activity

byWhile competing at a high level has proven difficult as young wom en, Polley-Fisanich and Dwyer keep a positive outlook towards the struggles they’ve endured during their career. Their disadvantage has made every win all the more rewarding because they’ve had to work harder to even the playing field, Dwyer said.

“There’s a lot of [misogyny] in the debate community that makes it harder,” Dwyer said. “There are less examples of women having high-level success that you can model yourself after.”

The pair recognizes the importance of having somebody to look up to and take pride in the fact that they’re able to be role models for young er women in the field, they said.

“I’m very proud of us, because I know for a fact that we’ve paved the way for a lot of girls,” Polley-Fisanich said.

One of these girls is junior Mitra Hu-Henderson. Already, Hu-Hen derson has amassed two gold bids, two silver bids and was named the top female speaker at the 2022 Lexington Invitational — a tournament where debaters can be awarded bids that qualify them for the Tourna ment of Champions. Hu-Henderson credits Polley-Fisanich and Dwyer for fueling her determination and drive for success, she said.

“Sophia and Katheryne are role models to so many women in Pub lic Forum [for] their success and impact on the debate community,” Hu-Henderson said. “As a female debater, seeing any successful female debaters really keeps you motivated to stay in the activity and work hard, especially when they’re on your own team.”

Despite the pride they take from inspiring women on the team, be ing a prominent member of a debate team is challenging. Debate tour naments in particular require participants to think well on their feet, something that can be stressful for many individuals. The challenge that comes with competition makes the experience of winning all the more addicting, they said.

“Debate is something that has the power to both build and destroy your self-esteem in equal measure,” Polley-Fisanich said. “The thrill of winning is unmatched, but when you’re really committed to it, the pain of losing is really brutal.”

“There’s nothing better than getting up and giving your speeches and seeing the fruits of your labor,” Polley-Fisanich said. “Deconstruct ing your opponents’ arguments and reaffirming yours is particularly re warding because you get to see how fast your brain can work on the spot.”

However, winning isn’t a guarantee. Throughout their debate ca reers, Polley-Fisanich and Dwyer have experienced a lot of defeat. These losses have given Polley-Fisanich and Dwyer skills that will be valuable to them for the rest of their lives, they said.

“At a certain point, you need to learn how to get yelled at, how to handle yourself in super high pressure situations and how to lose,” Dw yer said. “Even those moments where you’re not having debate success, you’re having a ton of personal growth.”

Although Polley-Fisanich and Dwyer are unlikely to continue com peting in college because opportunities in Public Forum Debate are lim ited, they plan to stay a part of the community through coaching and judging. The pair is eager to see Whitman Debate continue to thrive regardless of the end of their competitive careers.

“Whitman is one of the names in national circuits for a reason — we have a lot of smart people who are super committed,” Dwyer said. “There’s so many people on the team who have such bright futures and I can’t wait to see them step into new roles on the Whitman team and on the circuit.” ■

graphic by GABY HODORWhitman boys embrace their role as foster siblings.

After school, most students go home, grab a snack and unzip their backpacks to dive into a night full of homework. However, Bennett Browning (‘22) and sophomore Beckett Browning have something else on their minds when they walk through the front door: caring for their foster siblings.

Diaper changes, bottle refills and toddler tantrums often come be fore completing assignments and studying for tests.

Since February 2020, the Browning family has fostered eight chil dren. While two children were short-term placements who only resided in the Browning home for a couple of days, the other five stayed with them for months at a time. Most recently, the family fostered their first girl — a 14-month-old baby — who was the Brownings’ oldest longterm placement. After five months in their care, she moved in with a new family looking to adopt to begin forming a bond with them.

Becoming a certified resource family requires an extensive process consisting of interviews, fingerprints, stacks of paperwork and 10 weeks of training. During their training, Nancy and Cassie Browning, Bennett and Beckett’s parents, performed practice scenarios of difficulties they might experience while fostering. In November 2019, after completing the required course, the foster system assigned the Browning family a social worker to inform them of possible place ments. Having both dreamt of fostering children since they were young, Cassie and Nancy were excited to receive their first place ment, Cassie said.

“When I grew up, the adults in my life were very important and helped me find my path,” Cassie said. “I wanted to give that expe rience back to the children.”

In 2019, before begin ning the fostering process, the Brownings decided to only accept placements ranging from infants to 14-year-olds because Beck ett wasn’t keen on foster ing older teens. However, now the Browning’s longterm placements consist of exclusively infants and younger children as a result of the abundance of toddlers and infants in the foster care system who need a loving home. Many families aren’t willing to take in children under the age of two due to the fact that they’re difficult to manage and care for due to the fact that childcare centers only start at two years old, Nancy said.

While some families foster with the intention of adoption, this was never the Brownings’ plan. The same year they settled their preferred age range, they also collectively agreed to solely foster children instead of adopting them. Although their social worker offered the family a chance to adopt one of their long-term foster children later on in their fostering career, they ultimately decided to stick to their original plan even though it was difficult for all of them, Cassie said.

In February 2020, the Brownings received their first foster place ment, an infant weighing only four and a half pounds — three and a half pounds under the average weight of a baby that age. Shortly after receiv ing their first infant, many other resource families closed their homes to placements in fear of contracting COVID-19. However, the Brownings chose to continue providing foster support because they knew many children would still need a temporary home.

The infant resided with the Brownings for around one month before he was moved to a new location prior to the March COVID-19 surge.

The family’s second long-term foster was a premature baby that stayed with them for nine months. When the Browning’s social worker reached out asking if they would take in another child during the heart of the pandemic, the Brownings felt conflicted. Taking on another fos ter placement would be difficult because of the many extra precautions they would have to take to care for a newborn. Despite this predicament, when they heard about the child’s heart condition, the family decided that they would make space for him in their home.

“We thought both for him and the fact that we were a conservative family as far as really wearing masks and trying to be diligent, it would be a good match,” Cassie said.

Every time a child is placed in the Browning’s care, Bennett and Beckett make it a priority to ensure the child feels comfortable in their home. The brothers play games, read books and teach their new siblings how to communicate. The entire family enjoys the extra company the foster children provide, Bennett said.

“It’s just like having another brother,” Bennett said. “There’s some thing positive in every aspect of it.”

After The Department of Health and Human Ser vices relocates a child from the Browning home to their new permanent residence, the family eagerly awaits their next placement. Al though the process can take any amount of time, ranging from a few days to a year or more, the Brownings typi cally wait a period of four to five months before receiv ing their next placement.

When the Brownings’ social worker places a child in their home, they inform the family of a court hear ing date which determines whether the child will stay with the family until their guardian is ready to take care of them or if they’ll be placed into someone else’s care after their time with the Brownings.

Cassie and Nancy have the option to go on parental leave once their social worker calls them in need of a home for a child. They have access to up to 12 weeks of paid leave per year providing flexibility to bond with their new family member, as well as time to figure out a childcare plan and ensure that the child is adjusting to their new home.

“It’s really nice to have those days to settle down with them, bond with them and let them know everything’s gonna be okay,” Nancy said.

To properly welcome a new child into their family, Cassie and Nan cy ensure that their house is baby-proofed and that the child has activ ities or daycare to keep them entertained while they are at work. The Browning’s neighbors also step in to provide the family with childcare resources in case of a hurried placement.

“Many of our friends and neighbors will drop off diapers, formula and all of the things that you need in the first couple of weeks which is really a blessing,” Cassie said.

Considering that they receive foster infants and younger children, the Brownings get to see many of the children’s firsts.

“There’s a deep sense of satisfaction when the baby [leaves] four times as large,” Bennett said. “We even get to see them crawl and walk

“IT’S JUST LIKE HAVING ANOTHER BROTHER ... THERE’S SOMETHING POSITIVE IN EVERY ASPECT OF IT.”

“ “

at the end. It was cool to see them getting around and more mobile.”

No matter how long the placement is, the family develops close relationships and uncovers each child’s personality, Bennett and Beckett said. With long-term placements, the family is informed where the child will reside upon leaving their home, and they’re allowed to reach out to the assumed future guardian.

“Nancy really builds relationships and has been successful with the biological parents typically,” Cassie said. “Right now, [she] spends a lot of time talking to our foster daughter’s grandmother, and did the same thing with the first baby.”

Once a child’s placement with the Brownings has run its course, the family only has a few days to say goodbye before the baby’s new home is ready.

“It’s like, you’re happy that they’re going somewhere and you hope they’re going to thrive, but at the same time, there are things you’re going to miss,” Bennett said. “It’s a mixed feeling.”

Children are put into the foster care system for a variety of rea sons including, but not limited to abuse, neglect, parental drug abuse, incarceration, loss of parents and parent illness. If a family doesn’t have enough money to care for their children, they try to get them the resourc es they need. However, financial stress isn’t the sole reason to put chil dren into the foster care system but tends to make tense situations worse.

Sometimes the Brownings are aware of a child’s prior situ ation, but it’s not guaranteed that they’ll receive this informa tion. However, the child’s social worker informs the family of any critical information before transferring a child into their home.

The children the Brownings foster have occasionally faced previous challenging circumstances that make it even more crucial for them to experience a safe, loving home. In August, the Brownings received a call from their social work er saying that their next foster was a set of infant twins — one with broken legs and one with burn wounds.

The babies kept the family entertained with their huge per sonalities and playful behavior during the pandemic, Cassie said. Despite the fact that they spent their first few weeks with the Brownings in the hospital, the infants were able to come out of their shells when introduced to a caring home.

“[At first,] they’re really guarded, scared and hesitant,” Nan cy said. “A few months later, you see them explode with joy, smiles and laughter, and it’s really amazing to see that transfor mation.”

Once the children feel comfortable with the Brownings, the family is able to see that they are the same as other kids regard less of what their previous situation was like. The experience of fostering has opened the Brownings’ eyes to the struggles en dured by many foster children, helping to provide a better per spective on each child’s situation, Cassie said.

“I think that’s another thing [Bennett and Beckett] learned, that people are people, and we all struggle — some of us are more successful in our process or had more support in life,” Cas sie said. “I think they’ve been able to see the side of parents who have children relocated as well.”

Most children in the system range from infants to nine-yearolds because caring for a young child can be challenging and expensive. In the United States, childcare averages $1,230 per month for infants. In Maryland, however, the Children’s Health Program provides free health care for uninsured children from birth to age 19.

According to the Department of Health and Human Ser vices, foster parents must provide each child with attention, health supervision, basic physical needs, balanced nutrition, a home to live in and clothing.

The Managed Care Organization provides the rest, includ ing hospital and dental visits, medicine prescriptions and mental

health services.

The Browning family continues to expand their relationship with each child after they move out by visiting them multiple times a year. When the Brownings have the opportunity to see a child again, they find it rewarding to observe their growth, Bennett said.

By opening themselves up to unique opportunities as a resource family, the Brownings are able to give a better childhood to kids in dif ficult circumstances — their goal from the start. They feel that fostering has only had a positive impact on their family and that it has brought the entire family closer together, Cassie said.

“We have the kids here and they’ve all had such big booming per sonalities, we focus on them and they reflect back so much joy,” Cassie said. “During the pandemic, for example, there was less contention in the home than there might have been due to the focus on our foster chil dren.”

The Brownings strongly encourage others to get involved in fos ter care if they are interested. One option is to become a family on the emergency list — a roster of homes available for emergency, short-term replacements. Another option is to become a short-term or long-term placement family like the Brownings, where children are placed in a home for a set amount of time. Adopting a child in the foster care system and giving them permanent residence is also possible.

Courteney Monroe is President of the National Geographic Global Television Networks, for which she oversees global ope rations, marketing and the production of all National Geographic content. Monroe joined the company in 2012 as Chief Marketing Of ficer and worked her way up to become the Chief Executive Officer of National Geograp hic’s U.S. Channels in 2014. Prior to joining National Geographic, Monroe was the Execu tive Vice President of Consumer Marketing and Digital Platforms at HBO. While with the company, she marketed high-profile shows such as “Sex and the City,” “Game of Thro nes” and “The Sopranos.”

At National Geographic, Monroe heads numerous award-winning productions inclu ding documentaries and scripted series. Under her leadership, “Free Solo” — a documen tary following rock climber Alex Honnold’s thrilling free climb of El Capitan — won an Academy Award for the “Best Documentary Feature” in 2019. Additionally, productions “Jane” and “Genius: Picasso” have also at tracted global attention under Monroe’s direc tion, winning multiple Creative Emmy awards each.

Monroe resides in Bethesda with her hus band, Mike, and two children, Miles and Lola.

Responses have been edited for length and clarity.

THE BLACK & WHITE: HOW DID YOU BEGIN WORKING WITH NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC, AND HOW DID YOU ACHIEVE YOUR CURRENT POSITION?

Courteney Monroe: I was living in New York City and decided to move back to the Washington D.C. area because I grew up around here. The jobs that I had in New York were in media and entertainment, and I really wanted to stay in that field, but there aren’t a lot of media and entertainment jobs in the D.C. area. Somebody that I knew was on the board of National Geographic, and I set up an informational interview with that person to see whether there were any opportunities or if they knew of any other opportunities in D.C. It turned out that they had just hired a new CEO and he was making lots of changes at the executive level. They needed a new head of marketing, which is what I had been in New York. I worked at HBO in New York as the head of marketing, so I was offered the job to be the head of marketing at National Geograp hic, which I did for a few years and I loved it. I felt really grateful that I was able to have a job similar to my previous one in New York. About two to three years after that, the higher ups at 21st Century Fox — the company that

owns National Geographic — weren’t happy with the CEO, so they came to me and asked me to take over as the CEO of the entire tele vision network. This really surprised me — I didn’t have any experience with that position, and I wasn’t looking to switch jobs necessa rily. However, they offered me the job, and I said “yes.”

THE B&W: WHAT DOES YOUR DAY-TODAY LIFE AT NAT GEO ENTAIL?

CM: I’m responsible for the development and production of all National Geographic television and film, and its marketing. The marketing aspect relates to whether a film — like a documentary — is in theaters, pre mieres on the National Geographic television network or goes on Disney+. We are now part of The Walt Disney Company which is really fun because I get free passes to Disney World. On Disney+, there’s Disney content, Marvel content, Lucasfilm Star Wars content, Pixar content and National Geographic content. My teams are responsible for all of the content that goes on that tile. I have over 300 people that work for me. They’re based in D.C., Los Angeles and New York City, and all of them have jobs related to the making and marketing of National Geographic’s streaming, televisi on and film programming services.

THE B&W: DID YOU ALWAYS HAVE A CLEAR VISION OF WHAT CAREER YOU WANTED TO PURSUE?

CM: I definitely didn’t go into undergrad knowing what I wanted to do. I went to Wil liams College and I actually majored in Poli tical Science just because I was sort of intere sted in it — maybe because I grew up in the D.C. area. I thought that I actually wanted to go into broadcast journalism, so after college I worked at a really big advertising agency in New York City. During that experience, I fell in love with marketing, advertising and being in a creative business. It was during that job that I decided I wanted to go to business school and get my MBA.

Going into business school, I didn’t know for sure that I wanted to be in media and en tertainment, but I knew that I wanted to go into marketing. It wasn’t really until business school — or maybe even right after — that I realized I loved marketing. I also wanted to do marketing in an industry that really in terested me. You can get a marketing job in all businesses, but I wasn’t just interested in marketing. I wanted to be involved with tele vision and film — both things that I’m really passionate about.

THE B&W: CAN YOU DESCRIBE THE FEELING OF WINNING A “BEST DO CUMENTARY FEATURE” OSCAR FOR “FREE SOLO”?

CM: I would say, that was probably the best day of my entire career. To be fully accu rate, the people who actually won the Oscar were the directors of the film, Jimmy Chin and Chai Vasarhelyi, but it was for a Natio nal Geographic documentary film which we guided them through and gave them the mo ney to make. We did all the marketing to get Academy members to watch it and vote for it, so the experience was really gratifying. I was both shocked and elated. It was extraordinary. It was amazing. Even just going to the Oscars is an incredible thing, and then being a part of a project that wins an Oscar — it’s a once in a lifetime opportunity that most people don’t have, so I’m very grateful.

THE B&W: WHAT IS THE MOST MEMORABLE EXPERIENCE YOU’VE GOTTEN THROUGH NAT GEO?

CM: The Oscar was probably number one, or meeting Jane Goodall — that was pretty incredible. We did a documentary about her called “Jane” on Disney+. I got to lead her through that process. I’ve also had the oppor tunity to meet a lot of celebrities through both my job at HBO and my job at National Geo graphic.

THE B&W: WHAT IS THE MOST REMARKABLE TAKEAWAY THAT YOU’VE GOTTEN FROM THE WORK YOU DO?

CM: I’ve personally derived a tremen dous amount of satisfaction from my work. I love being a mom — that’s the most impor tant thing to me. But, I’ve also loved having this other thing that challenges me and affords me the opportunity to travel, meet really inte resting people and do really exciting things. It’s stressful though, too. I’ve had to be away from my family a lot for travel, and I’ve had to miss a lot of things because of my job. Howe ver, in the end, I love the challenge. I love the sense of accomplishment and I love leading people. I particularly love mentoring and lea ding young, aspiring women executives. I try to show them that you can have a big career and do things that are challenging, but you can also have a family — you don’t have to choose. There’s an opportunity to do it all in your life and live a really full life that’s filled with lots of different dimensions; that’s what my job has enabled me to do.

Schlesinger said. “The person was looking at themselves, studying themselves. That’s what a lot of life is about.”

Schlesinger developed a genuine passion for the arts when she was 13 years old. At first, Schlesinger was doubtful that she could build a career around art, but she later began to realize that despite it not being the most high paying job, art enriches the world and is a lifelong skill, Schlesinger said.

“I was impressed there was no silliness in any of the portraits,” Schlesinger said. “The person was looking at themselves, studying themselves. That’s what a lot of life is about.”

Schlesinger developed a genuine passion for the arts when she was 13 years old. At first, she was doubtful that she could build a career around art, but she later began to realize that despite it not being the most high paying job, art enriches the world and is a lifelong skill, she said.

This year’s winning piece was Waldorf High School then-senior Omari Lawson’s self portrait titled “New Horizons.” The detailed oil-painted skin tones and the composition of his eye-glasses captivated Schlesinger, she said.

This year’s winning piece was Waldorf High School senior Omari Lawson’s self portrait titled “New Horizons.” The detailed oil-painted skin tones and the composition of his eye-glasses captivated Schlesinger, she said.

Wright also earned success for his drawing titled “Girl with Red Coat.” His drawing depicts a girl, drawn out in pencil, with underwear on her head accompanied by contrasting darkened pencil shades and a red streak across her neck. The piece ended up in the show’s final selec tion of works.

Wright also earned success for his drawing titled “Girl with Red Coat.” His drawing depicts a girl, drawn out in pencil, with underwear on her head accompanied by contrasting darkened pencil shades and a red streak across her neck. The piece ended up in the show’s final selec tion of works.

In his artwork, Wright strives to capture aspects of death and na ture — a theme especially evident in his piece “purgatory.” The drawing contains a group of skulls fused together and blended in colors of gray and red.

In his artwork, Wright strives to capture aspects of death and na ture —a theme especially evident in his piece “purgatory.” The drawing contains a group of skulls fused together and blended in colors of gray and red.

“I’ve tried to make people more comfortable with death and more interested in nature,” Wright said. “People are very in their own heads and it’s not about them. It’s about the world.”

“I’ve tried to make people more comfortable with death and more interested in nature,” Wright said. “People are very in their own heads and it’s not about them. It’s about the world.”

While Whitman’s art programs help students like Wright develop their artistic expression, local art studios like Yellow Barn provide addi tional resources and unique opportunities for artists to hone in their skills outside of school. Whitman studio art teacher Robert Burgess believes the time that local studios provide to students, on top of a 45-minute art class, creates important spaces of development for aspiring artists, he said.

While Whitman’s art programs help students like Wright develop their artistic expression, local art studios like Yellow Barn provide addi tional resources and unique opportunities for artists to hone in their skills outside of school. Whitman studio art teacher Robert Burgess believes the time that local studios provide to students, on top of a 45-minute art class, creates important spaces of development for aspiring artists, he said.

Prior to submitting art into competitions like the Yellow Barn ex hibition, Whitman students typically seek out Burgess. He ensures that the artists are prepared for judging and helps them select the best piece for that particular competition. Burgess also wants to make sure that students are prepared for the mental aspect of participating in art com petitions, he said.

Prior to submitting art into competitions like the Yellow Barn ex hibition, Whitman students typically seek out Burgess. He ensures that the artists are prepared for judging and helps them select the best piece for that particular competition. Burgess also wants to make sure that students are prepared for the mental aspect of participating in art com petitions, he said.

“Some students are motivated by the competition, wanting to suc ceed in terms of ‘I put my best work out here, how’s it measure up?’” Burgess said. “Others shy away from them. Art is a little too personal for them, and they might not want to put it out there that way.”

“Some students are motivated by the competition, wanting to suc ceed in terms of ‘I put my best work out here, how’s it measure up?” Burgess said. “Others shy away from them. Art is a little too personal for them, and they might not want to put it out there that way.”

Burgess’ art classes include technical instruction on drawing and painting as well as focus on enabling students to become comfortable

Burgess’ art classes include technical instruction on drawing and painting as well as focus on enabling students to become comfortable

operating different tools. Burgess wants to use his classes to allow stu dents to escape the academic pressure of school, he said.

operating different tools. He wants to use his classes to allow students to escape the academic pressure of school, he said.

“I want them to learn to be free to create without fear; without fear of failing,” Burgess said, “to understand that the only way you’re going to improve is to work and take risks and experiment and be open to dif ferent ideas and possibilities.”

“I want them to learn to be free to create without fear; without fear of failing,” Burgess said, “to understand that the only way you’re going to improve is to work and take risks and experiment and be open to dif ferent ideas and possibilities.”

Both Burgess and Schlesinger hope to get more students involved in art programs such as the Yellow Barn competition because they en courage students to take risks with their art and put themselves out there.

Both Burgess and Schlesinger hope to get more students involved in art programs such as the Yellow Barn competition because they en courage students to take risks with their art and put themselves out there.

“I encourage people to be messy,” Schlesinger said. “Experiment, and you can ‘fail.’ I’m going to put that in quotes because really, people learn a lot when they fail, when they make a mistake. Sometimes mis takes lead to great discoveries.” ■

“I encourage people to be messy,” Schlesinger said. “Experiment, and you can ‘fail’. I’m going to put that in quotes because really, people learn a lot when they fail, when they make a mistake. Sometimes mis takes lead to great discoveries.” ■

1. Girl With Red Coat by Kip Wright, Walt Whitman HS (’22)

1. Girl With Red Coat by Kip Wright, Grade 12, Walt Whitman HS

2. Elephant in the Plains of South Africa by Audrey Young, Grade 11, Winston Churchill HS

2. Elephant in the Plains of South Africa by Audrey Young, Grade 10, Winston Churchill HS

3. New Horizons (1st Place) by Omari Lawson, Grade 11

3. New Horizons (1st Place) by Omari Lawson, Grade 12 Washington Wal dorf

4. Plastic Ashore (2nd Place) by Kath erine Yoon, Grade 12, Holton-Arms School

5. Frozen In Time (3rd Place) by Lariso Kachko, Albert Einstein HS (’22)

6. Canoe by Jeff Duong, Landon School (’22)

Art attributed to the Friends of the Yellow Barn Studio.

Some names have been changed to respect stu dents’ and teachers’ privacy.

Every student knows that one teacher, at Whitman or elsewhere. The teacher who made their older sibling cry. The teacher who’s constantly the subject of their friends’ com plaints about unfair grading policies or ineffec tive instruction. The teacher who’s been at their school for years and has never changed their behavior, despite repeated complaints.

Public school teachers with or without tenure can be fired quickly, even immediately, when a proven offense is severe. However, stu dents are stuck with ineffective or inappropri ate teachers because of an otherwise red tapefilled firing process when it comes to any other kind of offense. The often extensive, high-cost series of evaluations, reports and recommen dations protect innocent teachers from any personal discrimination from their superiors while simultaneously insulating insubordinate teachers who never do anything “bad” or “doc umentable enough” to be fired quickly.

Montgomery County is no exception. In the years between 2001 and 2012, Montgom ery County Public Schools dismissed only 245 teachers who underwent the formal evalua tion and review process: that includes tenured teachers every 3-5 years, but also every teach er new to the profession or new to MCPS. If distributed evenly among each MCPS school, that’s around one teacher fired for low-level of fenses every decade.

The nationwide teacher shortage of 300,000 vacancies this fall, as reported in Sep tember by the National Education Association, also complicates the issue for school admin istrations, at least when it comes to underper forming teachers whose methods are ineffec tive but not abusive to their students.

One of the larger trade-offs with the way the evaluation process fits into high schools like Whitman is that it is confidential by de sign, creating the illusion that there is less ac countability than there really is. But despite the confidentiality of the process, removal of teachers is very rare — even with fully devel

oped systems in place.

In a formal evaluation the staff members in MCPS responsible for assessments, department heads or “resource teacher,” and the designat ed administrator from each department, grade teachers on six core teaching standards. These standards include measures such as ensuring that classrooms are effective, professional and welcoming. In order to “meet standard,” teach ers must demonstrate proficiency in all six cat egories during their evaluation.

Analyses on these standards occur twice a year for all MCPS teachers who are in their formal evaluation year. Formal evaluations for all teachers consists of shared lesson planning with a department head “resource teacher,” les son observations and follow-up written report completed by both the resource teacher and the administrator overseeing the department in separate semesters. Evaluations occur on cycles of decreasing frequency depending on how long a teacher has worked at a school.

While these formal evaluations ultimate ly occur in cycles, informal observations and

“Peer

conferences with teachers also take place in re sponse to issues like a lack of professionalism, unfair grading practices, tardiness or repeated complaints from students. These complaints are often directed towards counselors or de partment resource teachers, who follow up as they see fit.

One of the main stakeholders in the teach er review and removal process within MCPS is the Montgomery County Education Associa tion (MCEA) — the teachers’ union in MCPS. Like any other teachers’ union, MCEA exists to negotiate teachers’ working conditions, ben efits, job security and to assist in any legal rep resentation pertaining to the workplace.

MCEA President Jennifer Martin deeply believes in the union’s power to not only ben efit teachers and their lives, but to improve students’ educational experience, echoing the MCEA’s common refrain of “teachers’ work ing conditions are students’ learning condi tions.”

The MCEA, along with school resource teachers and administrators, takes conflict between teachers and their students and col leagues in MCPS seriously, Martin said.

For that reason, in the late ‘90s, MCPS worked with MCEA to implement the Peer Assistance and Review (PAR) program — a one to two year process intended to provide assistance, resources and advisory to all new teachers, as well as tenured teachers who don’t “meet standard” in their evaluations.

MCPS teachers who have only taught within the county reach tenure when they be gin their fourth year, while MCPS teachers who have received tenure in another Maryland public school system earn it at the start of their second year.

The PAR Panel, a 16-person commit tee made up of teachers and administrators — which can include resource teachers and MCEA representatives — has a significant in fluence over the cases of staff members who are on PAR. That role includes working close ly with each case’s consulting teacher, a teach er assigned by the county to help improve the practices of a teacher under review. The panel serves as a check on a school administration’s power over the PAR process of their faculty members.

If a teacher is new or is “put on PAR” they receive a year of support before a combina tion of the PAR Panel and other county and school authorities decide on whether the teach er should join the regular evaluation cycle or continue to another year of PAR support. If a teacher comes to the end of the PAR program without making the changes to their behavior that allow them to meet the unfulfilled stan dards, MCPS will allow the teacher’s contract to expire. In combination with a teacher’s evaluations, the entire process can last two to three years, even four in very rare cases. The length and complexity of the process are in its design, and also perpetuated by the funds and personnel that PAR demands.

History department resource teacher Su zanne Johnson plays a key role in the evalu ation of teachers within her department. Con ducting classroom observations, collecting evidence, writing detailed reports and submit ting recommendations for teachers to be put on PAR occurs on a strict timeline and all of the responsibility falls on resource teachers and administrators, she said.

Since the union and the county are not di rectly involved in the standard stages of teach er evaluations at all, MCPS and the MCEA rely heavily on principals and administrators to effectively administer the PAR program.

“If a principal is doing their job,” Martin said, “they should be aware of who isn’t meet ing standard in their building, and be giving those people extra support and extra attention to make sure that they’re improving.”

Improving a struggling or problematic teacher’s conduct through PAR takes a lengthy amount of time, during which students and co workers may continue to be subjected to the behavior or deficiency under investigation.

“[It’s] not fair to the administrators, fel low teachers and parents,” said an anonymous MCPS teacher. “It’s definitely unfair to stu dents that they’re getting a subpar education simply because some part of the system can’t remove this individual from their job.”

Sophomore Arjun Mohan believes that in education, if as a student you have a bad teach er, you’re not going to succeed, he said. At the end of the day, students bear the brunt of the damage caused by weaknesses in the system that holds teachers accountable, according to Mohan.

“When you have a teacher that doesn’t teach you, or treats you inappropriately, or somehow makes it a lot harder to learn, it gets

really frustrating as a student,” Mohan said. “When the quality of the education is rather poor, but the level of learning you’re expected to demonstrate is really high, it ends up going poorly for everyone involved.”

The process leading up to and the PAR process itself are confidential by design, but the negative impact of this is students don’t always find their complaints are seen as legit imate and reach the teachers they need to see improve.

Not all tenured teachers enter PAR for the same reasons — there are a variety of reasons why a teacher may not meet standard. When teachers’ salaries, benefits and treatment in the workplace don’t allow them to properly attend to their home lives, they struggle to perform as teachers, and that harms the education experi ence for students, Martin said.

“I think we’re at that situation where we have to ask, does the teacher have the resourc es to be able to take care of their work-life balance?” Martin said. “That’s what makes a teacher truly able to focus on being an edu cator, and unfortunately, we don’t necessarily have those kinds of resources in place.”

Junior Claire believes that the overall learning experience of students deteriorates when teachers don’t seem to have enough time for them. When a teacher is too busy or too stressed to complete an important task for their job, the students suffer for it. She has first-hand experience with this, she said.

“When I tried to get my teacher to help me with my grade, she just got really frustrat ed and started complaining about her life and going on, how she didn’t have time for me,” Claire said. “I told her about concerns I had about a grade after the end of the quarter and she just got really mad at me and said, ‘I have too much going on [about] at home. I can’t deal with this right now.’”

English department resource teacher Lin da Leslie encourages every student whose school experience is negatively impacted by a teacher’s practices to communicate that to staff, she said.

“Even an anonymous note to your teach ers is super helpful to say, ‘Hey, I can’t learn from this practice’ or ‘Could you make more structure in your lessons’ or ‘Could you post your notes?’” Leslie said. “There isn’t a teach er in the world who doesn’t reflect on issues brought to their attention by their students.”

Closing the divide between teachers’ poor behavior and the systems in place to respond to those issues can help protect students and school employees from teachers with prob lematic behaviors.

“The system itself is designed to make sure that we don’t have a situation where we have weak teaching anywhere,” Martin said. “But are we giving our administrators the time to do what they need to do? Are we providing adequate support through the consultant teach er cohort? That, we could be doing better.”

“It’s definitely unfair to students that they’re getting a subpar education simply because some part of the system can’t remove this individual.”

1. End, legally 8. East, West, or Ivory 13. Empress Sissi, originally of _____ 14. Slow, for a musician 15. Large, coarse fern 16. Songs you might find in an 8-down concert 17. Over-the-top 18. Giant, mythological birds 20. Marital honorific 21. A show of dramatic behavior 24. Beer, but not a lager 25. Take On Me? 26. Someone looking through your stuff with ill intent 28. Where does Anne live? 31. You might find them on clumsy people’s limbs 32. What you’re under when you get caught 34. Friend 35. What you say when passing a dairy farm 36. Nothing Else Matters? 41. Spy on aurally, annoy, or a truly small creature 42. “Beware the ____ of March!” 43. “She’s All That” is one, with -com 44. Smaller than an island 46. Arid Chile 49. You’ll hear this when passing the stables 50. Puts under, for a surgery 51. Milk’s favorite cookies 52. Two people who might have their wedding officiated by Elvis

1. Head honcho at a monastery 2. Swiss theologian, abbr. 3. Egg-like 4. Fond du ___, WI 5. Bother 6. Alpine California 7. Ho Chi Minh City is actually not the capital 8. 1750-1820: after Baroque but before Romantic 9. It’s not under, it’s Olde English 10. The Arctic Monkeys, The Eagles, and Gorillaz walk into the House of the Rising Sun... 11. A child actor with high aspirations 12. Not catchers 19. Are you a Fortunate enough Son to Have Ever Seen the Rain? 22. Electric sea creatures, in German 23. Is There a Light that Never Goes Out? 27. Flowers: Spring, Leaves: ____ 28. Childish Redbone? 29. Pheromone 30. French quantum theorist 33. Cruz, Lasso, or Bundy 34. Color palette for a “soft girl” 37. Make fun of, good-naturedly 38. Royally ticked off 39. Outsider, new_____ 40. Collect 45. This might get in the way of your humility 47. “Much ___ About Nothing” 48. To lie