10 minute read

Hiive design

HIVE MIND

» Hiive is an innovative human-animal-centred design, created by a German start-up, which aims to provide beekeepers with an alternative to outdated and unsustainable traditional beehives. Claudia Schergna met the team behind the hive

Asked to help a friend with his beekeeping, German industrial designer Philip Potthast could not believe his eyes when he saw how antiquated the equipment was. And it didn’t take him long to realise this was not an isolated case.

“For many people, a beehive is just a box with bees inside, and that includes many beekeepers,” says Potthast, stressing the fact that, since artificial beehives were introduced over two centuries ago, this kind of equipment has barely changed.

Aware that bees, among the most important pollinators of plants - including our food crops - are facing extinction, he started thinking about how he could employ his knowledge to tackle this issue. To help him in his mission, he partnered with Fabian Wischmann, who he met at the Startup Centre of the University of Applied Sciences, Berlin.

The main issue with traditional beehives, Potthast explains, is that the climate inside those boxes is nothing near the one that bees find in their natural habitats among tree hollows.

This is what inspired the design at the heart of Hiive, the company that Potthast and Wischmann co-founded to help beekeepers tend their honeybees in a natural, sustainable way, by reproducing the microclimate of a tree.

“Most of the time, [beehives] are handcrafted by some companies who work with wood,” says Potthast, highlighting how the usual shape of bee boxes – a cube – is totally inadequate for the purpose.

“There are no cubes in nature,” he points out, explaining that the use of this shape directly affects life within the hive, including the inside temperature, moisture levels and the space available for bees.

The cylindrical structure used by Hiive mimics the natural geometry of a tree hollow. Using plant-based hemp to produce the cover provides natural insulation, keeping the inside temperature cool in the summer and warm in the winter, while helping regulate moisture.

This way, the bees can expend less of their energy heating the hive in winter, which they do by gathering and vibrating, and they always experience the right humidity level. ANIMAL MAGIC

Potthast describes Hiive as being an ‘animal-centred’ design, as opposed to traditional boxes, which only consider the needs of beekeepers.

By providing bees with something closer to their natural habitat, the new hive helps support bees’ natural behaviour and increases their resilience. This doesn’t mean that beekeepers have not been taken into consideration, however. Quite the opposite, says Potthast: “We have a lot of features in there for making it usable for the humans, like usability and ergonomics. If we designed it just for the bees, it would have been much easier and cheaper.”

To help beekeepers monitor swarms, Hiive is fitted with low-energy sensors installed all over the hive. Via an app, they get notified on when to expect a swarm and the conditions within.

Hiive is designed in two separate compartments, a honey chamber and a brood chamber, and the honey section can be opened separately for collection without disturbing the brooding room.

The structure is fully modular, with easily exchangeable components that allow for single parts to be replaced in case of damage.

The construction is based on sustainable materials including hemp, wool and clay, as well as polymers. As its designer explains, the project received some criticisms about the use of plastic because of a common misconception. “A lot of people think that polymers are not good. But plastic is not the enemy. The enemy is the human behind the plastic. Plastic is gold, actually, as long as it’s clean plastic and you can make a long-lasting product with it.”

The use of plastic is limited to the outer structure, while the surface that bees are in contact with is made of the natural fibres.

1

2

BUSY BEES

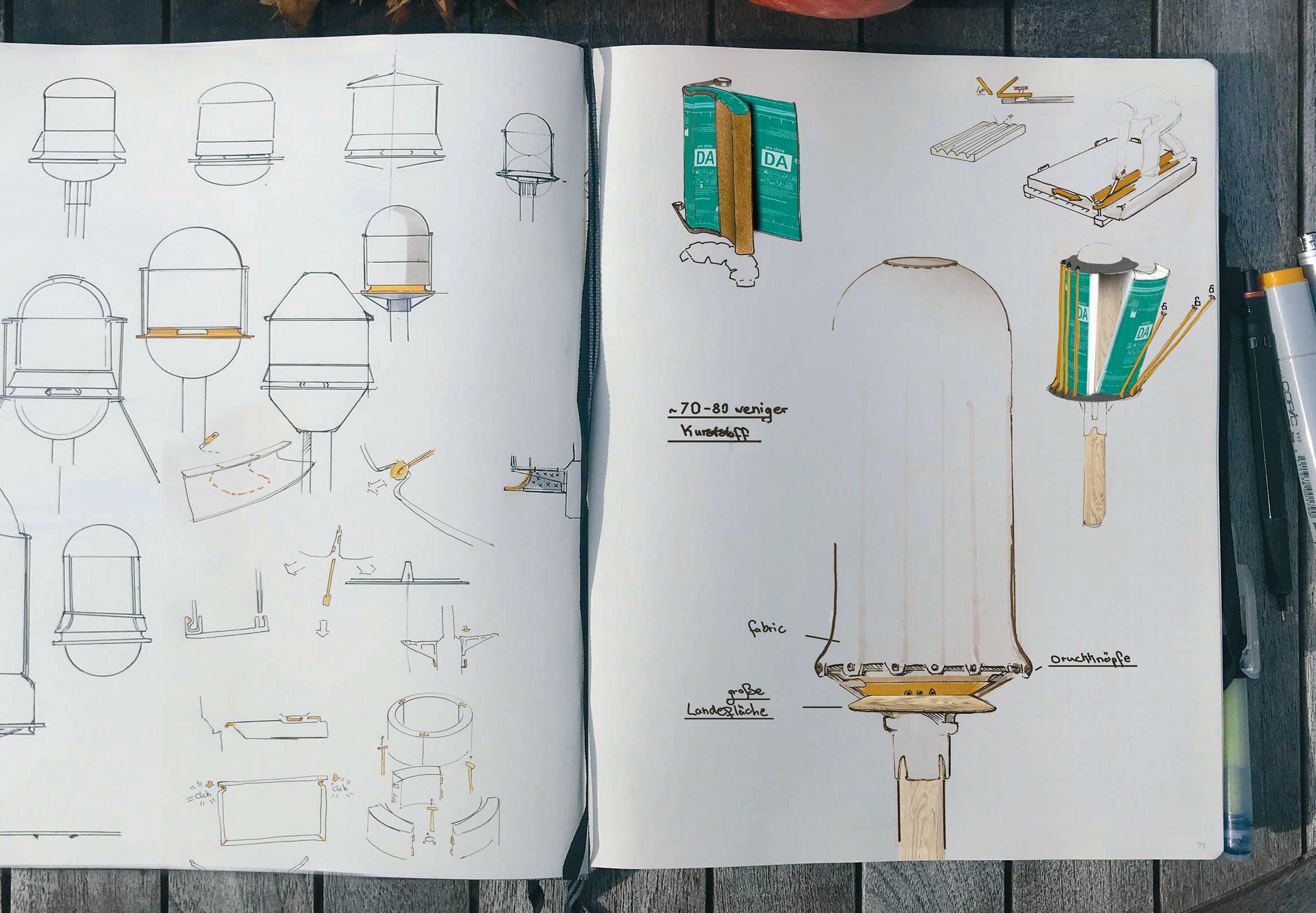

Over the past two years, Potthast and Wischmann worked on countless sketches using Adobe Photoshop and Autodesk Fusion 360, where they developed the 3D CAD models and carried out stress simulation tests.

The process then moved into Simplify 3D to prepare the model for 3D printing using their Flow XL CraftBot 3D printer, which was used to create physical mock-ups.

“The first prototype we did was like a spaceship – really ridiculous,” jokes Potthast, thinking about how much the project has evolved over the past two years.

“But that’s when we realised it was too small, and we came up with this really narrow tube design, that is narrower and therefore much longer, as we needed more volume. Now the volume is 45 litres.”

Potthast says 3D printing using the CraftBot turned out to be essential for the development of Hiive as it allowed them to produce prototypes at a reduced price and consumption of materials, giving them the opportunity to test the design multiple times while it was still in development: “You can sketch as much and as well as you want, but there’s nothing comparable to having in real life and holding it and trying it out with real bees, in nature, with the influence of rainstorms.”

An early prototype was knocked down by a storm, leading them to realise that Hiive needed to have a sturdier support structure, which they then developed. 3D printing was also key as it allowed them to produce prototypes to be presented to investors during the product’s Kickstarter campaign. cake. Potthast recalls sleepless nights during lockdown when he could hear his 3D printer on for hours, terrified something would go wrong and they would have to start all over again.

They were, in fact, working on a very tight schedule: “The whole timing is set by nature, not by you,” says Potthast. “We were almost late with the prototyping process, because bees start a new colony in May, and we needed to be ready to go outside with the beehive so we could give new housing to the new colony.”

Without 3D printing, developing the project over lockdown and on a limited budget would have been virtually impossible, says Potthast: “If we were to injection-mould all the prototypes, it would have cost us somewhere around €200,000 and, even assuming we had the money, we would have had to produce a whole range of tooling as well.”

Potthast and Wischmann don’t rule out 3D printing playing a part in manufacturing the end product, depending on the outcome of their Kickstarter campaign.

Something they are sure of is that the design process is far from over: “It is a new product and it’s a good product so far. But there’s always something that you could do a little bit better, and we are not stopping until we really get the best out of it.”

The pair’s work was recognised at the Dyson Awards 2021, where the project was awarded second prize.

Potthast and Wischmann are determined to revolutionise an industry that has seen little innovation for centuries. By offering beekeepers a sustainable and convenient solution, they hope to help tackle the threat of extinction that honeybees are facing and the consequences that would have on the environment.

●1 The narrow tube design boasts an internal volume of 45 litres ● 2 Sketches show the thought process that went into Hiive’s design

The proposed UK reintroduction of imperial measurements has been welcomed in some quarters. Designers, engineers and manufacturers must speak out before British industry gets burnt, writes Stephen Holmes

Things are hotting up here in the UK as we get our own fleeting glimpse of summer. Temperatures above 30C can inflict undue stress on our infrastructure, hampering not just roads and water supplies (even in a country where rain is the default setting), but also our ability to think straight.

For example, we’re already seeing newspaper headlines about ‘scorching heatwaves’, for which most front covers will employ a classic bit of trickery. In summer, they splash the temperatures in Fahrenheit, rather than Celsius, swapping an uncomfortably hot 32C day for a more serious-sounding 90F inferno.

Our tabloids, of course, are well-known for adding a bit of spice. And, in the winter months, they’re always happy to fall back on Celsius, preparing readers for an ‘Arctic blast’ heading their way. After all, negative temperatures always sound more dramatic.

For many, this annual back-and-forth between Celsius and Fahrenheit is reflective of the weird duality of British measurement. As a nation, we suffer from a collective hangover relating to the imperial system, which governed much of life and industry in the last century.

Today, the use of these measurements continues to be accepted, often running side-by-side with metric measurements.

Should it be pints or litres? A 100-metre sprint or a 24-mile marathon? A 15-stone man eating a 35-gram bar of chocolate? There’s no doubt about it. The struggle is real — and confusing. THE ART OF DISTRACTION The Metrication Board in the UK started swapping industry over to the metric system way back in the 1970s. By the 1980s, few bothered with imperial anymore. By the time the UK joined the EU, only the most jingoistic were truly up in arms about not being able to buy tomatoes by the pound.

However, the UK is no longer in the EU. And in an effort to distract people from… well, quite a lot of things actually, the current government says it is ‘giving the British people what they want’. And what they want, it insists, is a return to the imperial system of units.

For some people of a certain age, this is a joy to behold. But for many in our industry, it is a cause of great consternation.

For our last issue, I visited British car maker Alvis, a company that still has all its original engineering drawings, many dating back to the 1920s. Scribbled across some were metric measurements alongside imperial. The story was that some machinery had been bought in second-hand from Germany in the 1960s, and all parts to be machined on it would have to be recalculated into metric by hand across hundreds of documents. Some of you reading this may have a similar story, either from this period, or from working with US companies. (I doubt many of you are doing business in Liberia or Myanmar, the only other countries still officially using imperial.) But after nearly 40 years of normalising metric, there’s a chance of this upheaval returning. At a bare minimum, a reintroduction of imperial measurements would see extra costs associated with new packaging for international markets, reassessment of quality assurance guidelines, issues around recruitment and training, and reams of documentation needing to be rewritten.

As a worst case scenario, you’d better start preparing to get your team fully up to speed on British Standard Whitworth.

IMMINENT UPHEAVAL

It all sounds ridiculous, yet these ideas are already being considered as part of the formal planning stages now underway in central government circles.

For my part, I reckon that if you want to consider how you shop for carrots as a form of national identity, it suggests that you’re probably struggling on that front to begin with. But what the hell, go for it.

However, if all this comes to pass and starts creeping into British industry standards, then it has the potential to create all manner of issues.

The big ones will take more than a visit to WolframAlpha to fix, and British manufacturing could be heading towards another cold winter, regardless of whether you write it in Celsius or Fahrenheit.

The UK government insists that the British people want to see a return to the imperial system of units — but do they really?

GET IN TOUCH: Stephen’s off on holiday to Turkey shortly, where the tabloids would almost certainly describe the weather as ‘scorching’. He intends to spend this time shuffling around a pool in the manner of Ray Winstone in Sexy Beast. Enjoy that image. On Twitter, he’s @swearstoomuch