CHARLOTTE MULLINS A LITTLE HISTORY of

‘An energetic, illuminating and wonderful book’

Edmund de Waal

It is a warm June day in 1840. The young student John Ruskin stands in his cravat, coat and top hat in front of Turner’s painting Slave Ship at the Royal Academy’s summer exhibition. Ruskin drinks it in, overwhelmed by the turbulent sea, the pitching ship, the sky aflame as the sun sets. His eyes linger on the choppy waters in the foreground, where a single leg can be seen above the waves, its ankle banded with the tell-tale shackles of a slave. As he looks he can make out hands reaching out of the foaming sea, circled by fish and gulls eager for food. His own hunger is for the fiery sunset as it sinks blood-red behind the storm-tossed silhouette of the ship.

Aged twenty-one, Ruskin is taking a break from Oxford University for mental health reasons and is about to embark on a year-long tour of Italy. He has admired Turner’s art ever since his parents gave him an illustrated guide to Italy for his thirteenth birthday that was full of his Italian views. He even owns a watercolour by Turner, another birthday present, and he is hoping to meet the great painter soon. He has corresponded with him already and

found him funny and generous, although Ruskin knows most people find him coarse and unintellectual.

Ruskin read this year’s reviews of the summer exhibition with despair. While he thinks Turner is the most important artist alive the critics laughed at his latest works, saying he had ‘outTurnered’ himself with his ‘freaks of chromomania’. Ruskin doesn’t understand why they can’t see how brilliant he is. *

John Ruskin became nineteenth-century Britain’s most influential art critic. He published the first volume of his master work Modern Painters just three years after seeing Turner’s Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhoon Coming On), a work he would come to own. In Modern Painters he writes that the real subject of Slave Ship is ‘the power, majesty and deathfulness of the open, deep, illimitable sea’. What he totally skirts around is the contemporary subject on which Turner based this sublime reflection of ‘deathfulness’: slavery.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851) supported the abolitionists, who had finally managed to put an end to Britain’s involvement in slavery in 1833. It had taken over fifty years of campaigning. Slave Ship is based on historical accounts of the inhumane actions of the captain of the slave-ship Zong. The ship ran low on water on its voyage from Ghana to Jamaica in 1781. Many of the slaves in the hold were ill and so, with a storm approaching, the crew were told to throw more than 130 of them overboard, alive and in shackles, so the owners could claim insurance money – their policy would reimburse them for slaves lost at sea, not those lost to disease on board.

Critics were not averse to the subject matter of Turner’s painting – in the same exhibition François Auguste Biard’s (1799–1882) The Slave Trade was praised for its cleverness and accuracy. What critics couldn’t fathom, in fact all they could talk about, was the way Slave Ship was painted. The novelist William Thackeray ridiculed it for its ‘horrible sea of emerald and purple’ while another reviewer criticised its ‘passionate extravagance of marigold sky’. By contrast, it is Turner’s late paintings like Slave Ship that communicate most

directly with us today. As we confront the despicable actions of those in charge of the Zong the setting sun simultaneously marks the end of the slave trade, the tragic end for these particular slaves, the depths sea captains sank to for money and the brutal insignificance of all humankind when faced with the might of the sea.

Turner’s late canvases, full of emotional intensity, were often misunderstood by critics who were used to polished academic works. But the Romantics, including Turner, had shown that art didn’t have to be like that and, in France, young artists took confidence from this and confronted academic taste once again.

Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) retained the scale and grandeur of history painting while choosing as his subject figures from poor backgrounds who would leave no other mark on history – travelling musicians and stone-breakers, peasants and farmers. In A Burial at Ornans from 1849 over fifty figures attend a funeral in Ornans, Courbet’s hometown in eastern France. Each figure is life-size and together they stretch across a vast canvas well over 6 metres wide.

There are no heroes to focus on, no central characters. Courbet used people from the town to model for him and wanted to create a work of unflinching realism, a million miles away from David’s neoclassical scenes. As Courbet wrote in 1851, ‘I am . . . above all a Realist . . for “Realist” means a sincere lover of the honest truth.’ He weaponised art in support of the working class but his paintings were too much for many critics and they railed against them, finding them too ugly, too inelegant, too large, too socialist.

Critics preferred the work of Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899). Her energetic canvases of working horses and cattle were a big hit and she became France’s most successful female artist in the nineteenth century. The Horse Fair from 1853 is a spirited swirl of Percheron draft horses only just kept in check by hopeful traders. At over 5 metres wide it was the largest animal painting ever shown when it was exhibited at the Salon. Although, as a woman, she still wasn’t allowed to attend life-drawing classes at the Academy, no such rules applied to the abattoir and horse fairs. She did have to obtain special permission to wear trousers so she could disguise herself as a man in order to draw in peace, but her subsequent sketches from life enabled her to paint horses and other animals that seem to snort and whinny across her canvases.

In England, a different revolution was underway, spearheaded by a group of precocious artists who styled themselves the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, or PRB. Again, theirs was a rejection of the traditional teaching of art academies. They felt the Royal Academy exhibitions were full of bloated works that slavishly followed mannered styles of painting. They wanted to sweep recent history away and look back to Giotto and Van Eyck, to an innocent time before art became too knowing. John Everett Millais (1829–1896) had entered the Royal Academy’s Schools in 1840, the youngest ever student at the age of eleven. There he met Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) and William Holman Hunt (1827–1910) and in 1848 they formed their secret group, the PRB. In 1850 Millais exhibited Christ in the House of his Parents at the Academy’s annual exhibition. A young Christ stands in Joseph’s carpentry workshop, every wood shaving and fleck of sawdust carefully painted on the unswept floor. Christ

appears pale and wounded, having cut his hand on a nail in the door Joseph is working on, a premonition of his later crucifixion. This painting drove critics mad – the holy family didn’t look divine, they looked ordinary. The writer Charles Dickens blustered that Christ had just climbed out of the gutter, ‘a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-headed boy, in a bed-gown’. It was John Ruskin who jumped to the PRB’s defence, insisting their paintings were not ‘repulsive and revolting’ (Dickens again), but through their attention to detail, to nature, the Pre-Raphaelites were striving towards a deeper truth.

By the time the PRB was formed, photography had been in use commercially for nearly a decade. It seemed to offer the ultimate mimesis – for the first time in history artists were not the only ones who could reproduce images of the world. While the camera obscura had been known for centuries it wasn’t until the 1820s that inventors figured out how to capture the image it produced. In 1839 in France Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851) fixed his images on to silver-coated copper plates using light-sensitive salts, creating a ‘positive’ image of the camera’s subject. It took several minutes for his daguerreotype to appear and early sitters for portraits were strapped in to neck braces to ensure they didn’t move. In the same year the British pioneer of photography William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) fixed his images on paper ‘negatives’, known as calotypes. The initial images were not as sharp as daguerreotypes but the negative could be reproduced many times, like a print. Ultimately the two distinct processes of ‘drawing with light’ led to the collodion method, developed in the early 1850s, which captured the view as a negative on a glass plate from which repeated sharp copies could be printed.

In the 1850s photographs took off as a cheap form of portraiture and a way of saying ‘I was there’. Photographic studios rapidly sprang up around the world, and cameras went off on expeditions to the Arctic and into the theatre of war in the Crimea. By the 1850s photography was widely practised at the Iranian court of Nasir al-Din Shah, himself an enthusiastic amateur photographer. Photography wasn’t seen as an art form at this time but as a useful tool for artists, a modern-day sketchbook and pencil, and it

immediately exerted an influence. The 1856–7 Persian miniature Portrait of Prince ‘Ali Quli Mirza by Sani’ al-Mulk (Abu’l Hasan Ghaffari, 1814–1866) looks just like a fashionable studio portrait photograph, with its ornate setting and carefully arranged furnishings. Similarly in China the important Shanghai School artist Ren Xiong (1820–1857) painted a startling self-portrait where his naturalistic shaved head and bare chest have the clarity of a photograph but rise out of a highly stylised traditional Chinese jacket and trousers.

Some early photographers, however, did begin to experiment with the artistic possibilities of the new technology. In France, artists such as Gustave Le Gray (1820–1884) used the camera to take landscape photographs such as The Great Wave, Sète from 1857. In Britain Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879) explored the camera’s creative possibilities for portraiture, drawing on Renaissance art for inspiration. She created soft-focus compositions that transformed children into angels and dreamers and young women into the Greek enchantress Circe and the Virgin Mary.

Sculpture had to wait a little longer for its own revolution and the neoclassical style remained popular throughout the nineteenth century on both sides of the Atlantic. However, it was increasingly used for new sculptural subjects by a bold group of American women who lived in Rome in the 1850s and 1860s. Called the ‘strange sisterhood’ by novelist Henry James, the women moved to Rome to access the best marble, to see classical sculpture and because there was a plentiful supply of skilled assistants. The lure of a country in which they could work unimpeded, freed from the usual restrictions placed on nineteenth-century women, must have clinched the deal. Harriet Hosmer (1830–1908) was one of the first to arrive in 1852. She later wrote, ‘Here [in Rome] every woman has a chance if she is bold enough to avail herself of it.’

Hosmer had studied anatomy privately in Boston and had a thorough understanding of the body. While she created highly marketable cherubic sculptures to finance her stay in Rome she also carved powerful women such as Zenobia in Chains (1859). Zenobia was a third-century CE queen of Palmyra, in modern-day Syria, who was placed in chains by her captors. While her head is

slightly bowed she stands tall, nobly accepting her imprisonment. When the sculpture was shown in England in 1862 critics argued that such a piece couldn’t have been carved by a woman. They said it must be by her former tutor or by Roman workmen. Hosmer promptly sued the two magazines who alleged this and issued a lengthy rebuttal in the form of an article that explained the collaborative process of working with assistants, something that applied equally to male and female sculptors.

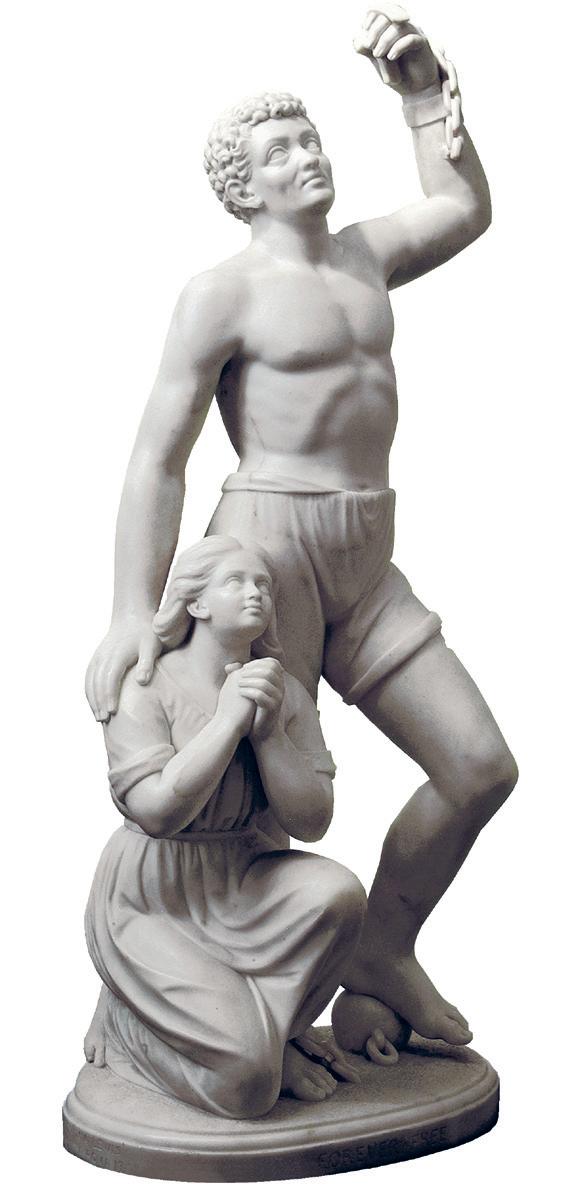

Hosmer’s circle also included Mary Edmonia Lewis (1844–1907). Lewis arrived in Rome from America in 1865 having raised money for her passage by selling busts of Civil War heroes and medals of abolitionists at a time when America was finally offering

black slaves their freedom. As a mixed-race woman with an African-American father and Native American mother Lewis was subjected to many prejudices in America and chose to spend much of her time in Rome, only returning home for the inauguration of her public sculptures. Instead of toeing the line in terms of traditional subject matter she created sculptures of black emancipation as in Forever Free from 1867. Two years later the sculpture was installed at the Tremont Temple in Boston. A black man stands, hand in the air, celebrating President Lincoln’s proclamation of freedom for all slaves. A woman kneels by his side, hands raised in prayer and thanks.

Rome may have been forward-looking for American women artists in the 1860s but France was still doggedly wedded to the Academy and the Salon. In 1863, however, an explosive exhibition at the heart of the establishment changed things for ever.