4 28 35 Vol. CXLIV Issue 7 Tenant Chemistry INSIGHT | Tyler jager Interrogating Yale's Music Major opinion | loren bass sanford Crickets poem | audrey kolker

MASTHEAD

Magazine Editor in Chief

Marie Sanford

Managing Editors

Abigail Sylvor Greenberg

Oliver Guinan

Associate Editors

Ana Padilla Castellanos

Isa Dominguez

Sarah Feng Zack Hauptman

Samhitha Josyula Margot Lee Dante Motley Idone Rhodes

Creative Director

Catherine Kwon

Magazine Design Editors

Nicole Ahsan Yuenning Chang Chloe Edwards Christy Lau Clarissa Tan Isaac Yu

Photography Editors

Gavin Guerette

Yasmine Halmane

Tenzin Jorden

Tim Tai Giri Viswanathan

Illustration Editors

Jessai Flores

Ariane de Gennaro

Copy Editors

Josie Jahng Maya Melnik

Hailey O’Conner

Patrick SebaRaj

Editor in Chief & President

Lucy Hodgman

Publisher

Olivia Zhang

Cover Illustration by Cate Roser

THE OCTOBER 2022 ISSUE

Hi Mag Fam, Goodbyes are hard.

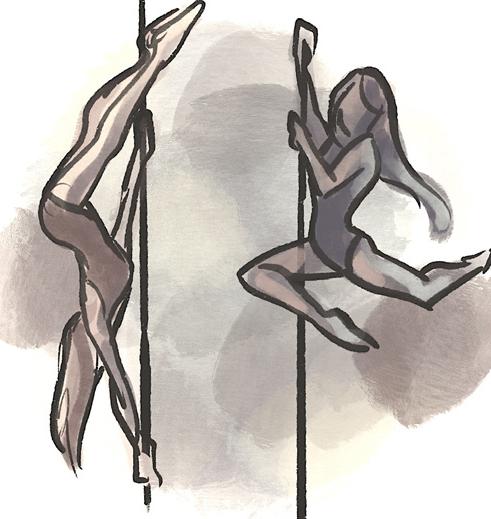

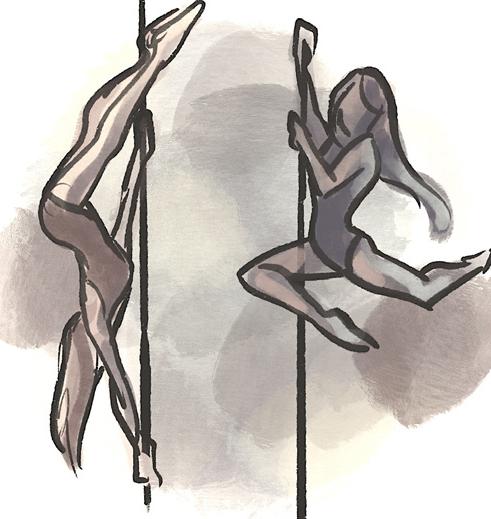

Last week, I had my last board meeting as editor in chief of the YDN Magazine. It was an open board meeting with many writers popping in and out of the newsroom for nal edits. In what has already become a lasting memory for me, I was working with Isabella Zou, the 2020-2021 Mag EIC, on her personal essay, “ e Pole Climb,” while Abigail Sylvor Green berg, an outgoing ME and the incoming 2022-2023 Mag EIC, sat across the table making nal revisions on Noah Humphrey’s religious commentary, “To the Preacher.” As the rest of the 2021-2022 board ltered upstairs to attend the meeting, Isa and I stayed back — both to nish discussing her piece and also to re ect and reminisce.

Like Isa, YDN Mag has been one of my most meaningful Yale experiences, from sta writ ing to being an associate editor to nally assuming the role of editor in chief with my amazing partner-in-crime Claire Lee. Along with long nights proo ng content in the tworoom, Claire and I spent a lot of time thinking about the culture we wanted to cra as EICs. We implemented social activities such as our cross campus print sales to help our sta of 30-strong bond. e night before print sales our board and sta would gather in the YDN basement with glitter glue, scissors, newspaper scraps, googly eyes, etc. to hand-make me mentos that would go towards printing the Mag. Everyone would very politely bop along to my shu ing Liked Songs while determinedly cutting away at pieces of construction paper — in e ect buying into our vision, for which I could not be more grateful.

But producing the Magazine has always been a collaborative labor of love, as we could not produce a publication without the YDN’s amazing Photo, Illustrations, Copy and Produc tion & Design editors. However, this issue is special, as it’s our rst time having a designat ed creative director, the imitable Catherine Kwon, who has already done much in terms of creating Mag’s new visual aesthetic. is heightened focus on production will help propel Mag into the already emergent digital media culture that is rapidly transforming news rooms around the country. But more importantly, it has been my utmost pleasure to work closely on my last issue with such a kind, attentive soul and a competent and innovative designer.

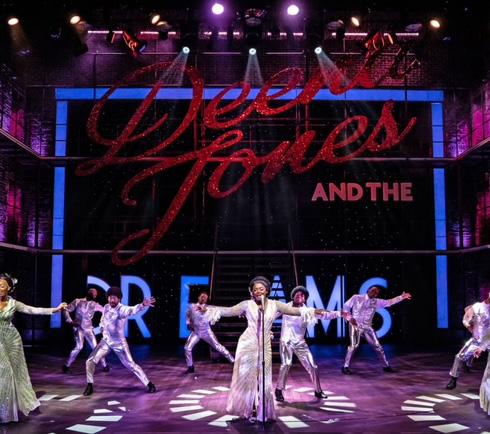

is issue is all about leaving it all on the eld, as my mom says. is is the rst issue in the current volume of YDN Mag that has a humor piece, Hannah Mark’s brilliant, “In venting (H)Anna(h),” and an opinion piece, Loren Bass-Sanford’s incisive critique of Yale’s Music Department. Gavin Guerrette’s beautiful photo essay, “Coming Home,” explores his changing relationship to his home, Pottstown, Pennsylvania, a er a year of grappling with Yale’s unthinkable wealth. Caleb Dunson’s comprehensive pro le of Christopher D. Betts follows Betts’ journey as a Black, queer artist from elementary school to now directing the Je Recommended production of “Dreamgirls” at Paramount Aurora eater in Aurora, IL. And Tyler Jager, in “Tenant Chemistry,” follows Connecticut Tenants Union organizers and local residents ardently ghting for their housing rights against exploitative landlords such as Pike and Ocean Management.

I am so proud of the stories shared in this issue of Mag. I hope they inspire you to question the status quo and remind you that your livelihood is worth ghting for. As I am reminded again and again during my senior fall: Nothing lasts forever; all bets are o

OPINION A Tight Squeeze: An Interrogation of Yale's Music Major Loren Bass-Sanford 4 Humor Inventing (H)Anna(h) Hannah Mark 9 FICTION Saturday Morning I Consider Being an English Major Ariel Kim 12 PROFILE Daring to be Seen: How Christopher Betts Reimagines Life rough Art Caleb Dunson 14 18 19 24 26 28 35 36 38 PHOTO essay Coming Home Gavin Guerette PERSONAL ESSAY e Pole Climb Isabella Zou POEM Crickets Audrey Kolker FICTION Hollow Alexandra Belluck POEM To the Preacher Noah Humphrey PHOTO Fencelines Elishevlyne Eliason INSIGHT Tenant Chemistry Tyler Jager POEM Erica Road Miranda WollenCO NTE NTS

A Tight Squeeze: An Interrogation of Yale’s Music Major

BY Loren Bass Sanford

BY Loren Bass Sanford

Afew weeks ago, I attended Flow in’, a conference that was hosted at Yale in honor of Dr. Farah Jasmine Gri n and her critical work on Black fem inist jazz and literary studies. It was prob ably one of the best things to ever happen to me. I met Dr. Gri n and many of my academic and cultural heroes, including Dr. Angela Y. Davis. e conference felt more like a family reunion than an ac ademic conference. Most importantly, I le with the triumph of knowing that it was possible for me to seriously study the music that I love — African American popular music — in its fullest capacity.

is conference did not focus on music or African American history in isolation. Rather, it centered on the inextricable link between Black feminism and African American music, history and literature. It was the rst space I had been in where I didn’t have to study music and culture separately. Music wasn’t an abstraction that existed in a vacuum, but a medium that embodied all parts of my identity, my sense of self and my family and our history.

Seeing people at the conference talking about the signi cance of Black popular mu sics — discussing the likes of Patti Labelle, Whitney Houston and Billie Holiday — was at once validating and infuriating because it made realize me the extent to which this mu sic had been either devalued or completely omitted from my music education at Yale.

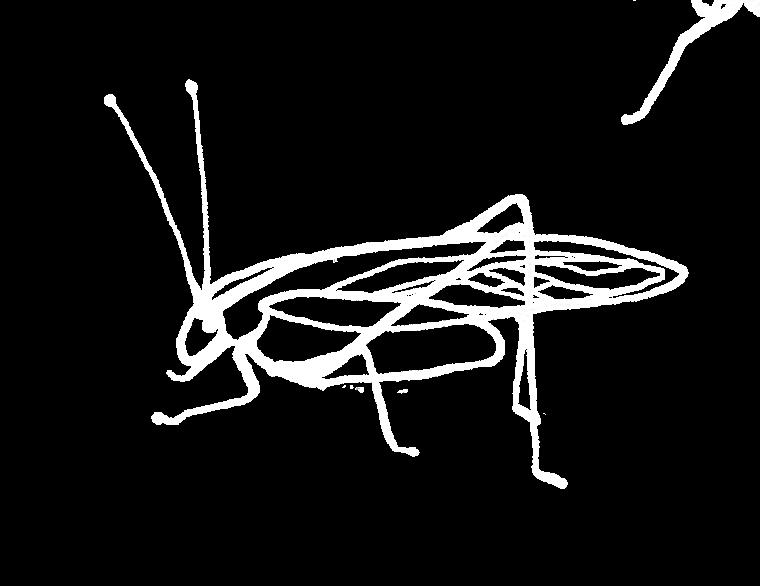

Re ecting on my experiences made me wonder about the experiences of oth er music lovers on campus. ere are so many talented musicians here — from a cappella singers and Yale Symphony Or chestra players to students who produce and perform their own music. How many students shared my experience? How many students would love to study mu sic but don’t see their interests re ected in the department? How many students have an unawakened love for music that may never be brought to life because of the narrow scope of the music curriculum?

e music major is divided into four groups: Music eory; Creative Practic es, which consist of performance, compo sition and lessons; Western Art Musics,

which is everything that would be collo quially called “classical music”; and World & Popular Musics. Unlike a conservato ry like Juilliard, where students focus al most exclusively on music performance, Yale’s music program follows a liberal arts curriculum that requires students to take two intermediate courses and one ad vanced course in each group. e major’s website states that “Yale’s music major is a general music program that combines studies in composition, conducting, eth nomusicology, music history, music tech nology, music theory, and performance.”

e experiences of myself and my peers, how ever, cast doubt on whether this claim is true. Amara Mgbeike ’22, who uses she/her pro nouns, is a vocalist and guitar player who came to Yale with a background in Gospel music. She was eager to explore Gospel music and learn about music production and writing vocal arrangements. Caleb Crayton ’22, who uses he/him pronouns, came to Yale with extensive experience writing and producing hip-hop beats for himself and his friends in a home studio

OPINION 4 | October 2022

setup. He and Mgbeike both began re leasing and performing their own music while at Yale and have continued to pur sue music professionally since graduating. Crayton hopes to pursue music full time.

When I asked Crayton if he ever considered majoring or double-majoring in music, he said that he considered it out of a love for music, but that his pas sion wasn’t in music theory, composition or classical music. ese disciplines, he said, are “more so what the mu sic major prepares you for unless you try to go at it on your own.”

Mgbeike said that most of her deci sion to not major or double-major in music was due to family concern about the viability of a music degree. However, those considerations aside, when I asked her if she could have seen

a place for herself in the music ma jor, she said, “I really have to say no.”

“ e course listings each semester didn’t have a lot of variety. Sometimes there’s one cool class or two, but the majority of what I’d have to take probably wouldn’t have excited me,” she said. “I’m so grateful for the extracurricular things that allowed me to be involved in music so I didn’t have to major in music and take class es I didn’t want to take.”

Mgbeike and Crayton’s rst encounters with the music major were in the fall of 2018, the year that a recon guration of the major went into e ect. In the previous structure of the major, Western clas sical music dominated the curriculum — sev en of the 16 credits were required courses that focused on Western classical music. e newly con gured mu sic major was supposed to provide more

exibility and decenter the Western can on through changes such as eliminating required courses and creating the group structure that allows students to have more choice in which classes they take.

It takes time for some of the impact of these changes to be felt, so it’s possible that aspects of the major have since im proved. I talked to Sage Friedman ’25, a sophomore considering majoring in mu sic. Friedman, who uses she/her pronouns, is a classically trained opera singer, but her true passion relates to music history and ethnomusicology, the study of music in its social and cultural contexts. She has a deep love for Caribbean music and the music of Haitian immigrants and is consid ering double-majoring in American Stud ies. During her rst year, she took “Com mercial & Pop Music eory,” a recent course added to the curriculum in the fall of 2020, as well as a class called “Western Philosophy in Four Operas,” which she de scribed as her “bread and butter.” She was so thrilled that she was exposed to things like “music history, ethnomusicology and all of these ways to study music as subject.”

OPINION Yale Daily News | 5

How many students have an unawakened love for music that may never be brought to life because of the narrow scope of the music curriculum?

// LILY dorstewitz

ough initially excited by those classes, Friedman has since developed concerns about how she will be able to further her course of study in the department. In oth er words, she’s feeling similarly to Mg beike — there might be one or two classes in her area of interest, but the majority of the department doesn’t really have a place for her. She told me she would be meeting with the director of undergraduate studies of the Music Department in the days a er our conversation to address her concerns.

“Now I’m here, having taken two music courses, and I’m like, ‘Okay, where is this going?’” Friedman told me. “ ere are kids sitting next to me in these music classes who are classically trained musicians of 10 years. ey know what this looks like for them, but my path is much less clear. I’m not a theorist or composer, and I’m not nec essarily a performer, so I’m worried I’ll have to squeeze myself into this shoe that doesn’t t to continue doing the thing that I love.”

When Friedman told me all of this, I jok ingly asked her how she got into my brain. We had never met before this conversa tion, yet she articulated my exact experi ence with the music major in a way that I had never been able to. I had been feel ing constrained by what felt like a narrow range of musical study and thus feeling less passionate about music as a whole.

Coming into college, I knew that I wanted to leave with a degree in mu sic because I wanted it to be part of my professional life. I knew I did not want to focus on performance or theory, so I settled on composition and began the four-semester-long composition se quence, even though my passion has never been for composing. At times my friends saw my dissatisfaction and sug gested I stop pursuing the composition track. What else would I do? I would re spond. e senior project options are a composition, a musical theater compo sition, a senior recital or a senior essay. I could have done the senior essay, but there weren’t enough relevant courses to undergird the writing and research I was interested in, African Ameri can popular music. us, I continued walking around with that too-tight shoe, even when it gave me blisters.

My experience in the music major is espe cially jarring when compared to my expe rience as an Ethnicity, Race and Migration major, also known as ER&M. ough my interests in ER&M would traditionally

are added in here and there — as Mgbeike noted — for the sake of diversifying the course o erings, but there is no structur al interrogation of who the major serves.

Sarkar is a classically trained pianist and composer whose work has received na tional and international recognition. ey decided against majoring or double-major ing in music because of the dominance of western classical music in the music major that resulted from this diversity approach.

fall under the African American Studies Department, the ER&M Program rec ognizes that a lot of African American studies topics overlap with ethnicity, race and migration. erefore, there are a lot of ER&M courses that re ect that over lap. In other words, I don’t feel like I have to leave the ER&M Department to sub stantially study various topics related to ethnicity, race and migration. Why is this not the case with the Music Department? Why do I have to go outside of the Music Department to substantially study music that is not of the western classical tradition?

While it was a rming to hear I’m not alone, I hated listening to Friedman echo the same problem. I’m glad that she has such a strong sense of what she wants to study and is tak ing the steps to make sure she is supported academically, but she shouldn’t have to do all of that heavy li ing. None of us should have to “go at it on our own,” as Crayton noted, if we want to deviate from the tra ditional path. No one should have to come into college knowing exactly what they want and be ready to ght tooth and nail to get it.

e fact that students are slipping through the cracks or feeling con ned within the major is indicative of a larger problem with the structure of the major, which lies in what Avik Sarkar ’23, who uses any pro nouns, calls its “diversity approach.” In this model, classes that focus on music outside of the Western classical music tradition

She noted that in this context, classes that don’t focus on Western classical can “only matter as additives.” is is why stu dents like Friedman, Mgbeike, Crayton and I did not — and have not — felt as though there’s a place for us in the music major. e music that we consider wor thy of serious study functions more as a way to enrich the education of students studying Western classical music than as a topic for any student to focus on, as if the music we love is an a erthought.

is is evident in the way the major still re quires students to interact with the West ern tradition for the majority of their study. Until last year’s introduction of the popular music theory sequence, almost all of the classes that ful lled the music theory re quirement were based in the Western clas sical tradition. e only classes that ful ll the intermediate level of the Western classi cal music history requirement are the same three history classes that used to be re quired for the major. In other words, there’s still a de facto requirement that all music majors take two of those western classical music history classes. Lastly, there are con sistently only three or four classes o ered in the World and Popular Musics catego ry — for comparison, the Creative Prac tices category usually has een classes.

On a smaller scale, the diversity approach results in feelings of alienation and lacklus ter support for students who want to study or create music that is not of the Western classical tradition. Sarkar gave this account from his semester in Composition Seminar I:

“I wanted to write something that was in uenced by Indian classical music, which has a very highly complicated system of notation, counterpoint, rhythm and meter,

6 | October 2022

OPINION

“I’m not a theorist or composer, and I’m not necessarily a performer, so I’m worried I’ll have to squeeze myself into this shoe that doesn’t t to continue doing the thing that I love.”

but there was no one to guide me through that. I was completely on my own. All any one wanted to talk about was that I was bringing in a diverse perspective. at to me is a problem with the diversity ap proach because it’s like, ‘We need to inte grate non-Western in uences into West ern music,’ but that leads to people only regarding this music as exotic and other.”

Mgbeike had a similar anecdote about her time in Composition Seminar I: “When I took Composition Seminar, I was trying to make something more jazzy than the rest of my classmates, so I kind of felt out of place. I wondered if that feeling would have subsided at all had I continued with the major. During my rst year, I was feeling like everyone was better than me or more advanced than me because they were doing something di erent from me.”

ese are the stakes of the diversity ap proach. Music lovers either see the over whelming dominance of Western classical music in the major and feel completely shut out, or they continue walking through the major with blisters on their feet, al ways feeling implicitly less than or exoti cized and exhausted from having to learn about the music they love without support.

Immediately following my conversation with Sarkar, I interviewed Dr. Fredara Had ley, an ethnomusicologist who specializes in African American popular music, who gave me some context that even further highlights the problems with Yale’s diversi ty approach. Dr. Hadley, who uses she/her pronouns, went to Florida A&M Universi ty, received her Ph.D. at Indiana University, and has taught at Oberlin College and Con servatory and e Juilliard School, both of which are conservatories where the over whelming majority of students study West ern classical music performance. When I asked her where her ethnomusicology courses t into the conservatory curriculum, she said many of her classes are electives.

“Conservatory students are required to take courses in Western classical music history, and there are always electives that they have le over. O entimes ethnomu sicology courses are among the electives they can take a er they’ve completed their classical music history requirements. At

Oberlin, students could use these courses to ful ll a cultural diversity requirement.”

While Yale’s Music Department does not solely focus on performance, the struc ture of the major is very similar to that of the conservatory structure Dr. Hadley described: Western classical music dom inates the curriculum and a few courses are o ered in other types of music to act as supplements to the classical music educa tion. e problem here is that Yale’s Music Department is explicitly not a conservatory. It’s also the Music Department, not the de partment of Western classical music or the Western-classical-music-and-a-few-oth er-types-of-music department. Dr. Hadley herself noted that departments like Yale’s are meant to be more exible than conser vatories, so one would think there’d be a much more expansive study of music in our department. But instead, as Fried man noted, the department is “boxing itself in and sti ing what could be a really vibrant and much more popular ma jor.” She continued, ““We all interact with music so di erently, it’s one of the most versatile forms of media you can engage with. I think the lack of versatil ity in the department is disheartening.”

I talked to the DUS — Dr. Anna Za yaruznaya, who specializes in music of the Middle ages and Renaissance — about a place to start with potential changes. I rst asked about cross-listing music-relat ed classes taught in other departments as a way to start, since hiring new music faculty would be a lengthy process. e list below shows some of the music-related classes that have been o ered in other departments since the recon guration of the music major but were not cross-listed with the music major.

• CSGH 370 e Media of Sound: Ex perimental Approaches to Sound De sign (Fall 2022)

• CSBF 370 Hip-Hop Music and Culture (Fall 2022, Spring 2021, Fall 2019)

• ENGL 423 Writing about the Perform ing Arts (Spring 2022, 2021, 2020)

• RLST 156 Buddhism & Hip-Hop (Fall 2021)

• FILM 338 International Movie Musical (Fall 2021)

• CSDC 330 e Art and Business of Songwriting (Spring 2021)

• AFAM 190/AMST 204 Protest Music and the Black Radical Tradition (Fall 2020)

• AMST 034 Country Music in America (Spring 2021)

• AMST 357 e Times of Bob Dylan (Spring 2020 but was canceled)

• CSBR 301 Music and Cinema: A His tory (Fall 2019)

• CSDC 300 Composing for Film & Me dia: Art, Innovation, and Commerce (2019)

• ENGL 350 Literary Sound Studies (Fall 2019, Spr 21 canceled)

• AMST 354 Music and Resistance in the United States (Fall 2018)

I also asked about the in clusion of the so-called “gen eral interest and introduc tory classes” that are taught in the Music Department but cannot cur rently be counted towards the major. Many of these are rst-year seminars like Music 081: “Race and Place in British New Wave, K-Pop, and Beyond,” Music 031: “Mu sic of Protest, & Propaganda” and Music 087: “Music, Memes and Digital Culture.” Some are introductory courses like Music 145: “Music in Japan,” Music 185: “Ameri can Musical eater History,” and even the class Friedman loved, Music 137: “Western Philosophy in Four Operas.” e exclusion of these classes from the major is a bit ludi crous to me — imagine taking one of these classes as a rst-year student or someone who’s interested in the major only to nd out those classes can’t count towards the ful llment of the requirements and the rest of the major looks nothing like those classes.

Professor Zayaruznaya, who uses she/her pronouns, said her “goal is never to gate keep” and that she would always be open to allowing classes to count for the major when individual students ask. She also

Yale Daily News | 7

No one should have to come into college knowing exactly what they want and be ready to ght tooth and nail to get it.

OPINION

agreed that some of the music-related classes from other departments should be cross-listed with music, noting that sometimes the department just doesn’t know that those classes are being taught.

While this is certainly nice to hear, it places the burden of getting credits counted toward the major on the stu dent and does not structurally change the prioritization of Western music. If the department made a more centralized e ort to include these classes in the ma jor that would be much more impactful. It’s the di erence between sure, we’ll al low that class to count towards the ful llment of this requirement in this one case and these concepts are important components of the study of music. Let’s make sure that is re ected in our course o erings. is requires both an interro gation or expansion of what is consid ered to be important to music education and an examination of the course o er ings to determine if the di erent types of music represented are actually getting

a matter of Western classical music being so disproportionately centered in the department to the extent that it’s di cult to study any other type of music substantively. It’s a matter of the curriculum being designed with a “typical” student in mind when, in reality, there should be no typical. While incorporating some of the classes I mentioned would be a great start, I dream of the vibrant music major that Friedman talked about.

What if the Music Department was a multicultural hub for the study of music? What if you could walk in and hear the sounds of someone learning how to DJ, a classically trained pianist preparing for a performance, and a classroom of students analyzing a Be yoncé album? What if the Music De partment was a place where a person’s love for music, no matter the form, could blossom instead of wilting from malnourishment? What if the Music Department could be reimagined so that students like myself, Crayton, Mgbeike, Friedman and Sarkar aren’t le behind or forced to squeeze into shoes that don’t t in order to pursue our love of music?

an equal amount of focus. at is what is missing in the Music Department.

In the last part of our discussion, I told Professor Zayaruznaya that this piece is not necessarily about me shaking my st at the Music Department. I just want so much more. I want my study of music to be as expansive as my love for music, and I want the same for all music lovers. It’s also not about getting rid of Western classical music — all of the students I spoke with value the many skills they’ve learned from studying that canon. It’s

OPINION 8 | October 2022

What if you could walk in and hear the sounds of someone learning how to DJ, a classically trained pianist preparing for a performance, and a classroom of students analyzing a Beyoncé album?

INVENTING (H)ANNA(H)

by Hannah Mark

by Hannah Mark

Over the summer, it seemed that every person on my Instagram feed was off on a glamorous study-abroad trip to Europe or doing research at a world-class university. Meanwhile, my sum mer activities included watching TikTok in my childhood bedroom and working a job where I came in contact with an ungodly vol ume of urine specimens. It prom ised to be a long, lonely and contemplative three months.

To combat the isolation, I start ed watching “Inventing Anna.” The show follows the true story of a plucky journalist named Vivi an Kent as she investigates a fake German Heiress named Anna Delvey who hoodwinked the New York elite. Anna — or rather, “In venting Anna” — changed my life. Anna’s character spoke to my soul. She had impeccable fashion sense, goddess-like networking capabilities, a deliciously dramat ic circle of friends, a really weird accent and a propen sity for engaging

in semi-illegal activities. She was who I dreamed of becoming. The only downside to my fascination with Anna was that I developed a deeply unfeminist urge to mar ry rich and spend my days being disgustingly wealthy.

With this in mind, I shifted my adoration to a more ethical character: Vivian Kent, the re porter who investigates Anna. With her razor sharp wit and in tense stare, Vivian Kent secured forbidden interviews, delved into intrigues and asked tough questions, scribbling everything into her super chic notebook.

Soon, I was lost in visions of a dazzling journalistic career. Instead of thinking about the bedpans I was scrubbing, I imagined the steamy, fantasti cal realm of a newsroom, the thrill of rubbing shoulders with celebrities, the jolt of adrena line incurred by a rapidly ap proaching deadline. I dreamed of living on sporadic paychecks while searching frantically

for the next big story. True, the desire to be a starving reporter is probably just as troublesome as the desire to be really rich, but at least it’s not unfeminist.

As I watched episode after epi sode of “Inventing Anna,” I saw both Vivian and Anna taking risks. They made moves. They knew what they wanted. They weren’t content to let things stay the way they were; they wanted big changes. They got what they wanted.

I began to reevaluate my own position, my own boring sum mer: What did I want?

Then it came to me. I wanted my life to be like Anna and Vivian.

In order to do this, I had to take a few steps.

HUMOR Yale Daily News | 9

//Yuenning chang

STEP 1.

Find the Next Big Story

For Vivian Kent, living in a busy city, the Next Big Story could be around practically any corner. Finding a story in my small town was a bit more challenging.

But then the only nursing home in my small town decided to close its doors, outraging residents and community members. Here it was, dropped into my lap, the Next Big Story. Now, I just

STEP 3. Leverage All Connections

I cold-emailed the editor of a local newspaper with my story pitch. I mentioned Yale immediately and said I was basically a pro because of all those YDN reporter trainings.

I even sent a writing sample — and prayed he wouldn’t realize it was a human interest piece and not real, hard-hitting journalism.

but one false move, and I would be outed as an imposter.

Then I remembered something Anna used to say: “You look poor.” Anna was right. If I wanted to be successful, if I wanted to be a real journalist, I needed to …

STEP 4 .

Dress for the Part

The slight issue with that plan: my journalism experience is limited to being a lifelong NPR nerd and taking approximately six report er training sessions at the YDN building. Fortunately, Vivian Kent showed me the real key to being a successful journalist …

STEP 2. Get a Cool Notebook

I went to the dollar store and bought a spiral-bound red notebook. Fueled by dollar store chips — which, by the way, are now $1.25, thanks, in

path to journalistic excellence was basically guaranteed by my new red notebook, I decided to

It sounds bold but hear me out. Along with some other max ims learned year, includ ing “milk the hell out of the alumni network” and “a buttery buck saved is a but tery buck that can be exploited for lots of free grilled cheese,” I dis covered that name-dropping Yale often grants me access to things

like writing a breaking news story about a nursing home closure.

And sure enough, the editor said he was delighted to work with me on the story. He even offered in ad vance to pay me for my article.

That’s when I realized I was in over my head. Pay me? What if it turned out the article I was theoretical ly going to write was complete garbage? I felt like Anna Delvey, sweet-talking her way onto a pri vate jet without paying for it. The

Thankfully, in smalltown Montana, the pace of fashion trends is always a few years behind, so an anti-wrinkle blouse from the clearance rack at TJ Maxx ba sically counts as de signer. Wrinkle free and ready to write, I proceeded to knock on doors and visit facilities and call old ladies who went to my church.

After gathering all the informa tion I needed, via lots of Google searches and Facebook stalking, it was the moment of truth. Was my journalist act enough to actually write the Next Big Story?

HUMOR

“HERE IT WAS, DROPPED INTO MY LAP, THE NEXT BIG STORY.”

Anna Delvey faced a moment of truth too. The huge bank loan she was trying to se cure — so that her fake socialite life could be real — fell through. Then, stranded in Moroc co without a func tioning credit card, she was nearly jailed for not paying her astronomical bills. Just like Anna in Morocco, my next task was to …

STEP 5 . Panic

I panicked about interviewing tech niques. Who was I, thinking that binge watching nine episodes of a me how to secure an exclusive in terview, crack people open and capitalize on their secrets?!

I panicked about the fact that 50 percent of my sources knew me, my parents and my grandparents held me when I was still in diapers and if I said anything that made the sources look bad, my life would be miserable forever.

I panicked about impending dead lines. In the show, Vivian Kent is

motivated to write her story by the

considered this form of motivation, but decided it wasn’t feasible for me.

Eventually, though, it was time to …

STEP 6. Do It

I relistened to my interview tapes, I reviewed notes, I fact-checked jar with minty water — very VIP — and forced myself to sit at the desk until I had a passable draft. Then I wrote the article.

And lo, it was published! On the front page! And there was my name in print underneath it, just like a real journalist! Vivian Kent would be proud of my article, and Anna Delvey would be proud that I absolutely and completely im provised my way through it.

After I wrote the article, I went to the mystical news room I thought it would be. It was a 100-year old shag-carpet ed building with a staff of exactly three people. I read some previ ous editions of the paper and realized the editor I “hood winked” was actu ally writing 90 per cent of the articles himself. Maybe he just let me write the article because he was tired of doing all the reporting alone.

In any case, Anna Delvey and Vivan Kent taught me that you can get a lot of things just by asking for them. Take a page out of An na’s book and steal a jet. Or buy a cool red note book. Or some thing like that. With a little imagina tion, you too can reinvent yourself.

HUMOR

“VIVIAN KENT WOULD BE PROUD OF MY ARTICLE, AND ANNA DELVEY WOULD BE PROUD THAT I ABSOLUTELY AND COMPLETELY IMPROVISED MY WAY THROUGH IT.”

Saturday morning I consider being an English major

BY ARIEL KIM

BY ARIEL KIM

Something like that, I gesticulate. It’s not like I’m all that into medieval literature. I’m not about to analyze “Beowulf” for the 14th time. e mouth of the MCDB major sitting opposite me at the dining hall grins.

It’s outdated, you know? e idea that you’re supposed to choose between your passions and nancial stability. I choose both, I say. e right side of my lips pinch together. My facial expressions have always been uneven like that.

It’s outdated, I repeat into the phone that evening, my IKEA lamp perched overhead. Umma rambles

FICTION 12 | October 2022

// Ariane de Gennaro

on the other end of the phone, something about how cousin Lana interned at all these major lm agen cies but now she’s working at a furniture startup. About how Jin-woo from across the street is a computer sci ence major now. How Un cle Park sold his start-up for $100 million, how Yale is the past and Stanford is the future and “you shouldn’t have rejected Stanford for a humanities school.”

You don’t know the job market as well as I do, I lie. For Umma, I produce soothing placebos of million-dollar book deals and million-dollar movie deals. How humanities majors might not have the best starting salary but “that doesn’t mean we don’t have an upwards trajectory.”

“Act as if,” preaches the reddit thread r/thelawofattraction. Or, fake it till you make it. On Sunday I talk to Sara about the eventfulness of my summer as if it were a continuous strand of string rather than thumbtacks

scattered across a corkboard.

I don’t mention that the cork board was one-half existential ism and one-half nearly-crash ing-Dad’s-hon da-while-par allel-parking. I imbue constella tions of meaning into this web-de velopment in ternship or this trip to see my childhood friend. I don’t say that my employer asked for nine iterations of the homepage and that visiting Jocelyn was a mu tual therapy session.

Sunday a ernoon I’m training as a peer mental health coun selor and the counselee scenar io I’m supposed to act out goes something like “you’re a sec ond-semester sophomore with crip pling loneli ness and are considering self-harm.”

I’ve never considered self-harm, I think, somewhat pleased by this realization, but by the end

of the scenario I am crying. For a second I was convinced that was real, the instructor remarks. I laugh. No, no, no, I wave my hands. Not at all.

Monday morning I’m tucked into my chair-desk watching Professor Leitus draw a story diagram on the board. Fiction is realism, he remarks. We read stories, not because we want to watch the knight slay the drag on, but because stories sneak around somewhere near the truth. I like writing because I can fold myself inside the word ction. Oh, it’s just ction, I’d say. It’s not like I mean any of it.

Monday evening I lean on a beanbag and stare at the draw ings on my wall. I wonder if be ing a writer just means that I’m monetizing entries in my diary.

I wonder if that would be so bad.

I go on Student Information Ser vices, click “de clare English.” I can always undo it later, I say into the phone. Umma, it’s not like law school is going anywhere.

Yale Daily News | 13 FICTION

"It’s outdated, you know? The idea that you’re supposed to choose between your passions and f inancial stability. I choose both, I say."

“Humanities majors might not have the best starting salary but “that doesn’t mean we don’t have an upwards trajectory.”

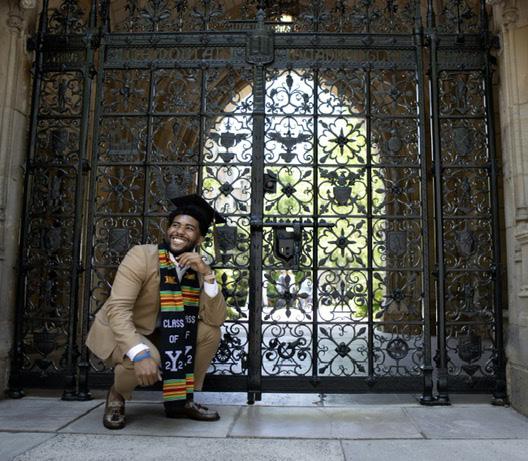

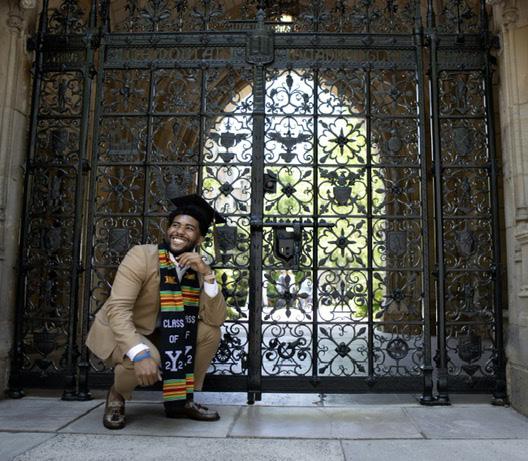

BY CALEB DUNSON

PROFILE 14 | October 2022 How Christopher Betts Reimagines Life Through Art Daring to Be Seen:

Christopher Betts has a great memory. He remembers the names of his elemen

ed in (“Cinderella,” when he was seven),

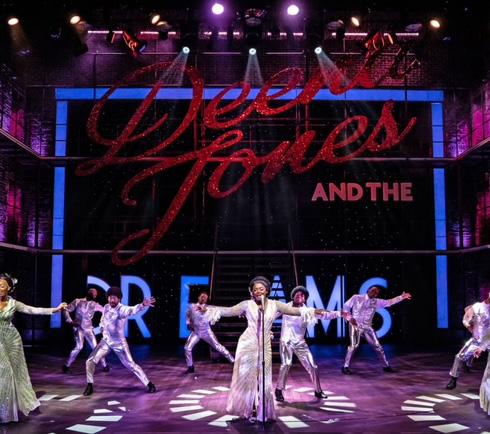

production he saw (“Wicked,” on July 19, 2006) and all 30 shows from a theater fes tival he attended in South Africa in 2017. He shares all of these memories during an interview, done via Zoom from his New York City apartment. Betts is an NYU and Yale Drama graduate and the director of the Paramount Theater production of

his hair, worn in thick twists, as he thinks, and he often pauses between phrases for long stretches, tilting his head toward the sky and letting his mind search for the exact word he wants to use. He backtracks and corrects himself as he tells stories, deter mined to convey what he’s thinking in me ticulous fashion. It’s the same attention to detail he puts into his work, which he sees

When Betts was in preschool he joined a performance his grandmother, a kindergar ten teacher, was putting on with her class. He practiced and got dressed up for the performance, but Betts said, “When we got to the theater I was like, ‘I don’t want to do it…’ So then she was like, ‘Okay.’ She was like, ‘All right, you could just sit in the audi ence.’” So he did. He saw his grandmother’s he views as an “omen from the universe that I should be a director not an actor.”

Betts’ grandmother Frankie, much like him, was a creative. Though she couldn’t

craft the career in the arts that she wanted –– largely, as Betts says, because it was dif

do so –– she found ways to share her love for the arts with Christopher. “My grand

way of my making theater… that wasn’t informed by her.” The performances she put on with her Chicago Public Schools students — the pains to which she went to make those performances look beautiful — stuck with Betts. “The one thing I can say about all of the plays I’ve done is that they looked good… and I know that I get that from my grandmother.”

Betts’ work strives to “give Black people [a] sense of joy and exuberance.” To Betts, that means making sure that his produc tions look good because “there’s been so many centuries of black people… not be ing elevated in as much beauty and excel lence as we have.” Betts’ shows burst with color; the lights make the brown skin of his actors sparkle on stage. They convey the richness of Black life, undergirded by the belief that “being able to see representa

tity.” That belief, and that goal, are rooted in his childhood relationship with theater.

As he went through middle school, Betts was bullied. During that time, he turned to theater as a respite. “So many of my ear liest memories are related to theater be cause it was such a sanctuary for me. And I think that it was the thing that helped me keep going. It was the thing that helped me know that everything was worth it.” When not doing theater, he found other ways to express his burgeoning creativity. In third grade, he set up a pretend swap meet in his family’s apartment and tried to convince his family members to buy what he was selling. He delved into fairytales and fantasy books, which he says “gave me hope that my life could be more than what I was born into.”

But what truly resonated with him was a collection of VHS tapes, created by the Encyclopedia Britannica, that showed car toon fairy tales performed in different cul tural contexts around the world. The tapes

a European telling of the story, and the last two parts were the same story told from the perspective of non-European coun

to seeing non-white people in whimsical and fantastic circumstances, and that creat ed a hunger for more.” Those fairytales si multaneously made him feel that life could be more interesting than what it was and highlighted the absence of non-white peo ple in fantastical narratives. That absence of visibility felt personal for him because, as Betts said, “There’s a connection between not feeling seen as a person and being in formed that there are stories all over the world that aren’t being seen.” Betts had felt reduced to invisibility in middle school,

PROFILE Yale Daily News | 15

“I needed a drastic change because I felt that the capitalist model for theater was going to eat me alive. And I knew that I wasn’t going to like the art I made, I wasn’t going to like myself.”

“Betts’ shows convey the richness of Black life, undergirded by the belief that “being able to see representations of ourselves…

dredness in the lack of representation, and it made me feel empowered to do some thing about it.” It was the beginning “of a quest to try and create more stories like those because the visibility of those stories also created more visibility for me.” This link between identity and art, and the work to reconcile the two, have framed much of the tension that characterizes Betts’ work.

It was Betts’ high school theater teacher that told him to consider pursuing an act ing career. From that day, Betts took the ater seriously, and he decided to go to NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts to get his

for him. “I gave up my whole life to go to NYU,” Betts said. “I gave up everything I knew about life, and everyone that I loved was so far away.” That, in addition to nav igating a new environment surrounded by classmates that were “fucking rich” made college a profound challenge for him. But the central frustration was that of not be ing able to fully express himself in theater. “When I was in college, gay boys needed to be able to play straight. And I did not want to do that. I found theater because I wanted to express sides of myself that I was taught were not beautiful, that were shameful and that need to be put away… so I started to fall out of love with theater because, well, what was the point? I wasn’t in it.” Betts hated the shows picked to be performed out of his studio that year, so he had one of two options: take a role in a show he didn’t like, or direct his own. He chose the latter.

The show was called “Carrie” and it told the story of a teenage girl struggling with bullying. Betts chose the show largely because he felt a connection to the main character’s experience. “I remember I was so focused, and I was so excited, and I had so much energy… people could call me at three o’clock in the morning to talk about “Carrie,” and I would be like, ‘Yes, I’m up,’ because it meant that much to me. And I remember looking at all the design and re search images and walking into tech, and seeing the set and seeing the actors and costumes and being like, oh my god, 1000 people are about to see my perspective on this story that meant so much to me as a child.” This was the moment for Betts — wherein he had the opportunity to be vulnerable with his audience through his work — that reignited his joy for theater.

Now Betts views directing as a profoundly

I direct something I’m literally taking my mind and my imagination and putting it in front of people and saying, ‘This is the way that I think, would you like to see?,’ and I don’t know how to be more vulnerable than that.” It’s a step forward on the jour ney toward complete self-expression that in hindsight seems straightforward to Betts.

Straight out of college and living in New would allow him to keep a roof over his head and pursue his newfound passion for directing. So he took several assistant positions, working under actors like Phyli cia Rashad and helping on projects like “Moonlight.” His plan was to work his way up the ranks and eventually turn those as sistant positions into director positions. But things began to stagnate. While Betts was getting opportunities that many would

dream of, he wasn’t getting chances to work on his own projects. The positions he was taking weren’t bridging the gap between wanting to be a professional di rector and being a professional director.

Betts characterized that gap as ambiguous and frustrating. “I knew what I wanted to do,” he said. “I knew that that was what I was supposed to be doing. But I didn’t know how to get there. That’s depressing. When you’re an actor, you can show up, you can go to 1000 auditions, but when you’re a director, it’s much more of a chick en and egg of how to establish yourself.” Giving everything to the roles that he was in, Betts began to burn out. “I needed a drastic change because I felt that the capi talist model for theater was going to eat me alive. And I knew that I wasn’t going to like the art I made, I wasn’t going to like myself.”

In search of a new experience, Betts ap plied to the Taymor World Theater Fellow ship. Getting the fellowship would give him an opportunity to travel to several countries to explore their approaches to art. Though he said it was a long shot, he won the fel lowship. From 2017 through 2018, Betts traveled to South Africa, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya and Morocco. Finding himself in a new environment, Betts began to see what it looked like for theater to be a commu nal act, not just one that employs profes

Many of the performers he watched had other jobs and used theater as a means of self-expression. The celebration and rever ence of it all, the love of art for art’s sake, was compelling to him. “[It was] refreshing to be in the presence of artists who felt that their stories mattered, and who knew their audience, and who knew that they could share in community their stories and also be affected by other stories.”Grounded by

PROFILE 16 | October 2022

“When I was in college, gay boys needed to be able to play straight. And I did not want to do that. I found theater because I wanted to express sides of myself that I was taught were not beautiful, that were shameful and that need to be put away… so I started to fall out of love with theater because, well, what was the point? I wasn’t in it.”

this experience, Betts ventured to Yale to get his Masters in Fine Arts. “I felt that I could either assistant and associate direct my way into the position that I wanted to be in as a director or I could make a per sonal investment,” Betts said of his choice. The opportunity to build his portfolio and get the backing of an elite degree made the decision simple for Betts. His experi ence in the MFA program was colored by the pandemic, as he lost opportunities to put together shows and work in person, but he still found his time at Yale valuable.

One of his most meaningful experiences was directing “Choir Boy” at the Yale Rep ertory Theater. Originally, Phylicia Rashad was slated to direct the production, and Betts sought to work alongside her as an assistant director. He relished the oppor tunity to work alongside Rashad again, so

James Bundy, the Dean of the Yale School of Drama, and asked to be put on the mu sical. Soon thereafter, Rashad was tapped to be the next Dean of Howard University’s College of Fine Arts, leaving the director’s

to direct at the Rep, an opportunity which

reminder from the university to keep it up.”

More than that, directing “Choir Boy” gave him the chance to pay forward a the ater experience that was once so resonant for him. In an interview for the Yale Rep ertory Theater about “Choir Boy,” Betts

stage in Tarell McCraney’s Marcus, call ing it “ the most humanizing experience I had in the theater” and expressing a hope that “Choir Boy” could be that for some one else. “I hope that Black queer youth see [“Choir Boy”], and see their place in the work… and they know that the world would not turn without them,” said Betts.

moment, Betts was moved by the prospect of having created an experience that those girls will carry with them, an experience that might inspire them to pursue the arts. His time back in Chicago has also led him back to some of the very people that shaped his view of the stage. The artistic director for “Dreamgirls,” Jim Corti, directed one of

shared this with Corti after Corti hired him. “He had no idea 14 years ago that he would direct a show, and that he would [eventual ly] be hiring someone who saw that show” all these years later. For Betts, their recon nection was a testament to the ability of theater to leave marks on people’s lives.

cal’s author, Tarell McCraney, a good friend of Betts’ for whom he was an assistant in years past. The production, according to

Today, Betts is working on several new projects. Among them is the production “Dreamgirls,” running at the Paramount Theater in Aurora, Ill. Betts has spoken about what returning to his hometown means to him in an interview with the Au rora Beacon-News, highlighting how he is now in a position to carry forward his grandmother’s legacy and share the gift of art that was once given to him. Speak ing with me, he shared a story of seeing four young Black girls sitting in front of him

When asked how he thinks about his lega cy, Betts leaned away from the discussion of awards and accolades. Instead, he framed the question as one of process, practice and progress. His goal for right now is “daring to be seen,” and his hope is that his work

“By showing up bravely and authentically, as who I am, I allow people to see me. And by allowing people to see me, I know that will inspire others to be seen as well.”

PROFILE Yale Daily News | 17

// PHOTOS COURTESY OF CHRISTOPHER D BETTS

To the Preacher Noah

Your own past drowns in Bible passages and screams out sin in front of a crowd

wrap wounds of

who are you without

trauma and ask forgiveness.

pulpit,

crazed gospel and hapless sacrilege?

see headlines and false teachers scheming in their megachurches.

In the shadows, faith

In the light, they exile them from

to batter scarred women.

False

use

to bribe the public,

in

–

who are you behind

set sail on the Arc but jump ship like

care?

them about their Trinity,

them if

has a key, Ask them if they have committed these sins — then I am ready for hate

//Jessai Flores

POEM 18 | October 2022

To

generational

Preacher,

your

your

I

leaders use theology

churches, Expelling feminism from sacred spaces,

prophets

apology

Hypocrites

holy clothing

darkness underneath their cloaks. Preacher,

your pastoral

You

Jonah. Ask

Ask

morality

speech.

humphrey

COMING HOME

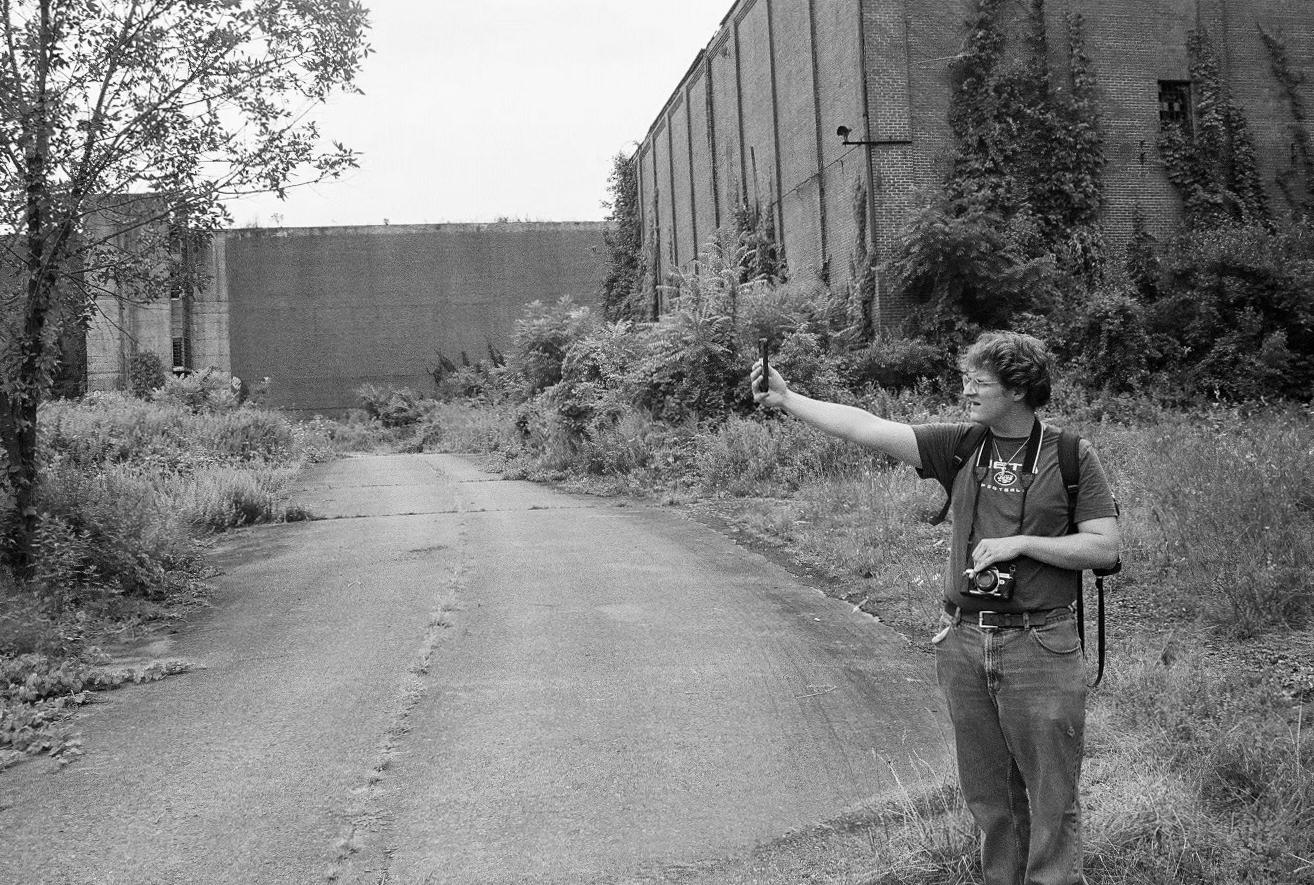

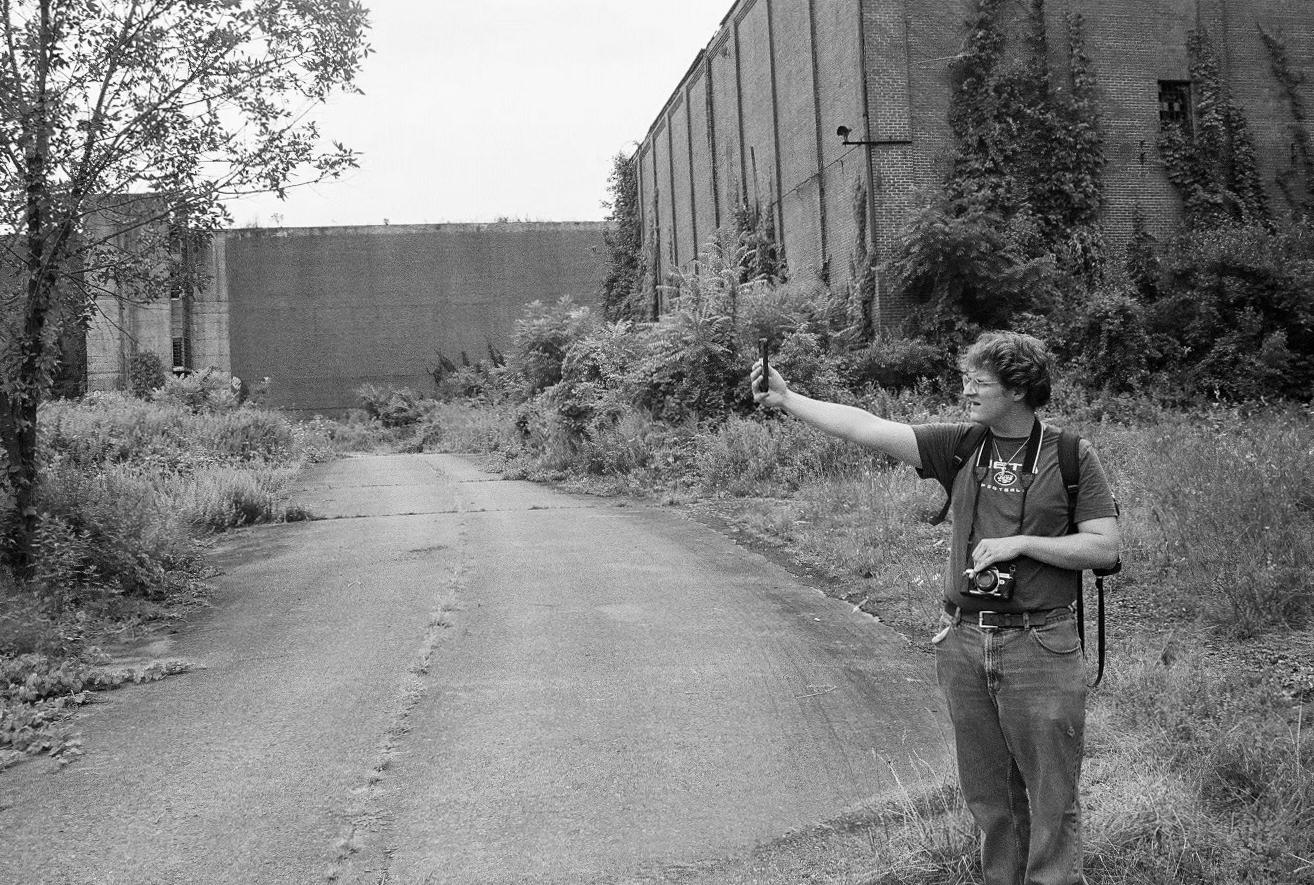

by Gavin Guerrette

by Gavin Guerrette

PHOTO ESSAY

Ispent countless hours this sum mer exploring the area around my home. My friends and I would wan der, talk, listen to music and take pictures together. It was a simple and rewarding way to keep busy and en tertained throughout the summer. It also provided a new way for me to observe my home, Pottstown, Penn sylvania. e little suburban world I grew up in, surrounded by the dead and discarded remnants of Ameri can industry, had always seemed so painfully mundane to me. Home felt like a place from which to escape — there had to be bigger cities and more intellectual vitality elsewhere. But, as summer crawled by and I continued to work and take pictures, I came to

thoroughly appreciate the authentici ty, the almost vulgar honesty, that life at home brought me.

About halfway through this past summer, I bought a 35mm manual SLR camera for $30 at a yardsale. In well over my head, with little prior knowledge of photography, I had to learn the process behind lm photog raphy in order to make use of my new camera. Equipped with a phone cam era for the better half of my life, I was used to the spray-and-pray method of photography – take as many pic tures as you need until you get it right and delete all the rest. Shooting lm manually, however, forced me to slow down, take one or two well composed shots of a given subject, and move on.

A typical roll of 35mm lm has either 24 or 36 exposures on it. With each exposure (i.e. photo that I want to take) I have to manually adjust the shutter speed and aperture settings on my camera based on readings from a light meter, as well as focus the im age. Each shot requires its own series of considerations based on lighting, composition and the type of lm I’m shooting on. Once I’ve used every ex posure on a given roll of lm, I have to get it developed and scanned, a pro cess that can take up to two or three weeks. is delayed grati cation to see how an image turns out has made me particularly concerned with the quality of my photos — every detail has to be correct to justify everything

20 | October 2022

that goes into taking and seeing a sin gle photo.

In an e ort to elevate the quality of my photography, I began to inten sify the attention I gave to my home town and allowed myself to see beauty where I had before felt disdain. I be came singularly concerned with cap turing the essence of home through my photos — the pace of life, the charm of its people, its rich industri al history now replaced by econom ic stagnation and our proximity to nature. Rather than taking photos of everyone and everything in a docu mentary style, I narrowed down my subject matter, focusing primarily on architectural studies of abandoned in dustry and street photography.

My architectural studies gave me the opportunity to explore with my friends and to feel wonder at some thing I was once embarrassed of. No town proudly admits that it is a shell of what it once was, struggling to pro vide for its residents as job prospects grow farther and farther away from home. For the longest time it felt easier to look past these steel husks and the harsh realities they contained, shi ing my gaze outward towards bigger cit ies and better opportunities. As I ex plored these spaces with friends, how ever, their history began to unfold and fascinate us — the fact that sprawling industrial complexes where countless people spent much of their lives work ing could become abandoned within a generation, and then drowned in overgrowth and gra ti soon a er, gave us a resounding sense of tem porality. With my camera in hand, I felt that I could draw art, but also anthropological insight, from these places, capturing their state following

abandonment, focusing primarily on the ways in which nature attempts to reclaim itself from industry as well as the ways in which individuals leave their marks on these spaces. In the act of photography, I captured these spac es in a particular moment in time, where the nuances of these miniature histories formed the basis of what I found to be so beautiful about them.

I also took a particular interest in street photography over the summer. Walking the streets of Pottstown with a camera completely recontextualized my view of the town. It gave heart to a place that felt so lifeless; it person alized a place I thought I could just leave behind. e primacy of authen ticity over aesthetic purpose necessi tated by street photography vitalized my subjects, who were Pottstown resi dents going about their everyday lives.

rough the lens of my camera, I was able to better grasp the appeal of not only my hometown but also its resi dents, whose lives embody a sense of sincerity which I feel Yale lacks.

At Yale it feels like our language is shrouded in euphemism and mock concern for the events of the world as we ponder this or that from our neo-gothic castles, sleeping com fortably on the promise that we’ll be successful enough that none of these things will a ect us. At home, however, I was grounded by my friends, coworkers and family into a real world, a world where detach ments permitted by wealth and oth er forms of privilege that are all too common at Yale simply don’t exist.

I spent the summer working in construction alongside my father, do ing manual labor which trivialized so much of my experience at Yale. is

university produces a thinking class of individuals, who might only ever be theoretically concerned with what goes into making a building, but a er digging the trenches myself, spending days in the beating sun, and looking down at my dirty calloused hands at the end of each day, the intellectual chatter of Yale felt so silly.

I know that part of me wanted to spend my summer at home working construction and taking photos for how distinctly non-Yale it was, with no prospects for academic or profes sional advancement and certainly no soul-searching abroad in Europe. Per haps I chose to do so to be able to lord it over those Yale students who could stomach the opulence of the rst year dinner, but I’d like to think I did it for a more idealistic reason: before the ac ademic and professional pressures of Yale start to close in, I wanted a nal chance to internalize the parts of my self that I won’t allow the university, or anything else, to touch.

With the memories of the place that I am leaving behind, Yale has become a strange new home for me. At the periphery of wealth and power and desperately holding on to the shreds of my idealism, these photos are keepsakes of a place which I hope to keep within me as I pass through life. Contained within them is an embrace of the vulgarity of truth, a dedication to find the beauty of everyday life and a refutation of the cynicism of the bottom dollar. While in them selves they are photos, they con tain a world that I took into the palm of my hand and examined gently, finding a place which I am sad to leave behind.

Yale Daily News | 21

PHOTO ESSAY

erica road

Miranda Wollen

I wake up unwashed with two rubber bands on my wrist, extras for you in case yours break and you go back to picking away at yourself. You drive us to the next town. You pack no bags.

Erica Road is lined with foliage, the kind you don’t see on the east coast this time of year. As the clouds part over the bay, we sing like God is coming home with us.

You bump the car too hard into the curb in a t of frustration. e front-right wheel well skitters on the pavement. My anger is just enamel. You keep scraping me.

You tell me you want seven children; that I am special, if not important; that everything is God; that I am a safe love, a good love, if not a great one. I paint your sentences onto smaller birds, the migrating kind.

POEM 24 | October 2022

Still, I keep house: I think of buying yellow tulips and sending mail back home. I walk the slow, careful paths around your neighborhood until I grow so sick of them I cannot speak.

Two nights, we go out to dinner. You wear both of your good dress shirts. One is bright red. I wear all white. I’ve planned on doing so. is way, when I retell the story I might seem sacri cial, prepared — innocuous.

We drive to the airport. It’s the rst rainy day since I’ve been here, six days beyond my welcome. My hand cramps when you grasp it, a so ness withering in my lap. I won’t move away.

From the car, you watch me try to leave you.

I waste four minutes at a broken ticket machine. Only when I relent, turning back to your negative, do you sit up in the driver’s seat and recede into the foggy line of piecemeal natives.

Once, in the spring, it rained all day and you held me as I shivered and I wished more than anything to t into you for as long as I could.

//catherine kwon

POEM Yale Daily News | 25

BY Alexandra Belluck Hollow

People are hollow like ghosts, and the whole world is hollow, and I can’t get over that lurk ing sadness. Most days I wake up thinking about Mom. You have no idea what it feels like to be a shadow.

On the rst day of college, my mom unboxed the tea kettle she bought for my suite. Every night since then, I’ve made myself chamomile tea before bed. From the start of the tea-mak ing process, I am soothed. e kettle whispers so white noise. en, its screaming whistle announces that the water is boiling…

“Hey, how are you?”

“Fine. Good. How are you?”

On the outside, that’s what I reply.

People are hollow like ghosts, and the whole world is hollow, and I can’t get over that lurk ing sadness. Most days I wake up thinking about Mom. You have no idea what it feels like to be a shadow.

I want to scream this truth.

Being hollow means feeling constricted and feeling empty. Being hollow means having skin and a body and not knowing what’s in side. Being hollow means becoming so used to hiding your pain that you can’t look within anymore — because if you look within, then you’ll discover something that you can’t show to other people.

FICTION 26 | October 2022

Hollowness looks like me scratching a pen on pa per, trying to bring my mom back into existence. e pen runs out of ink, and I press harder. I’m making grooves; I press harder, and the ink stops owing. She doesn’t come back.

I choke down my despair. None of my friends will understand. It’s not their fault that they can’t make me feel any less alone.

I sit in class as a shell. I get up and go outside to cry because I can’t face the rst line again. I can’t bear to analyze Camus’ line. “Today, Mother died.”

…But when I get home, I will make myself tea. Warm steam will caress my face: the mist will transport me back to that very rst cup.

But tonight — ere’s no bubbling. e water is cold. I plug it in and plug it in many times. Nothing happens. e light doesn’t turn on. I sink to my knees and stare at the kettle. I’m willing the water to boil. I can make it boil with my mind if I stare hard enough. e water will boil. It has to boil. If it doesn’t boil I don’t know what I’ll do. It has to boil right now. I cast a spell and make a wish. I pray, I pray, I pray. e water doesn’t boil. It’s all falling apart.

I reassure myself that, when I make my green tea in the morning, the water will be hot. Tomorrow will be better. It’ll be boiling.

I don’t sleep well. I wake up to make tea as the sun is coming up. I press the button, expecting the gentle hum. Carmen, my roommate, dri s into the common room.

“ e kettle is not working,” I say. I crack my knuck les and shake my head in disbelief. Carmen runs into her room and grabs her own tea kettle. “Here, try this one.” I snatch it out of her hands. A so “thank you” escapes my lips. It’s not better; noth ing’s ne, screams inside.

Carmen’s tea kettle makes a disquieting hissing sound. I don’t like the water, which is scalding. e water from the kettle my mom gave me was some how always the perfect temperature. I ll the mug to over owing, and burning liquid spills over the lip and onto my hand. I wince from the physical pain of the welt forming on my hand, and the in visible shock of grief.

A week later, my dad shows up for Parents’ Week end. He knows about the kettle, so he comes with a brand new one. He buys me the fanciest kettle. It’s one of the retro looking ones. e kind that makes me wonder how a basic kitchen appliance can somehow project style. I like the way the chrome gleams on this new one and the way that the out side feels smooth to my touch. e fact that it’s my favorite color, lilac.

We plug it in, and I make tea. e room is too qui et. Why doesn’t the kettle cry out to me? How will I know when the water’s boiling? Even when the ket tle is full, it sounds hollow.

A faint beeping sound alerts us that the tea is ready. My dad pours me a cup. I hold the mug to my chin, waiting for the steam to li me. We sit and catch up and try not to talk about the biggest absence. e whole world is hollow. Mom is dead.

Yale Daily News | 27 FICTION

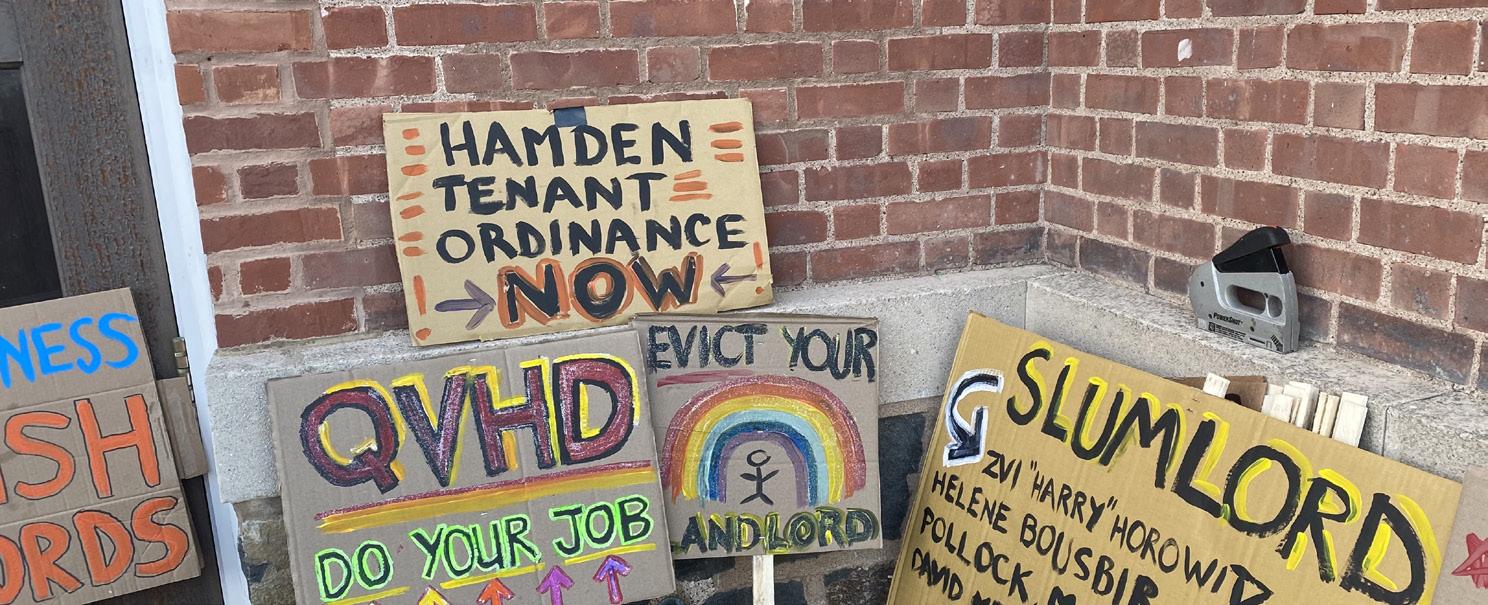

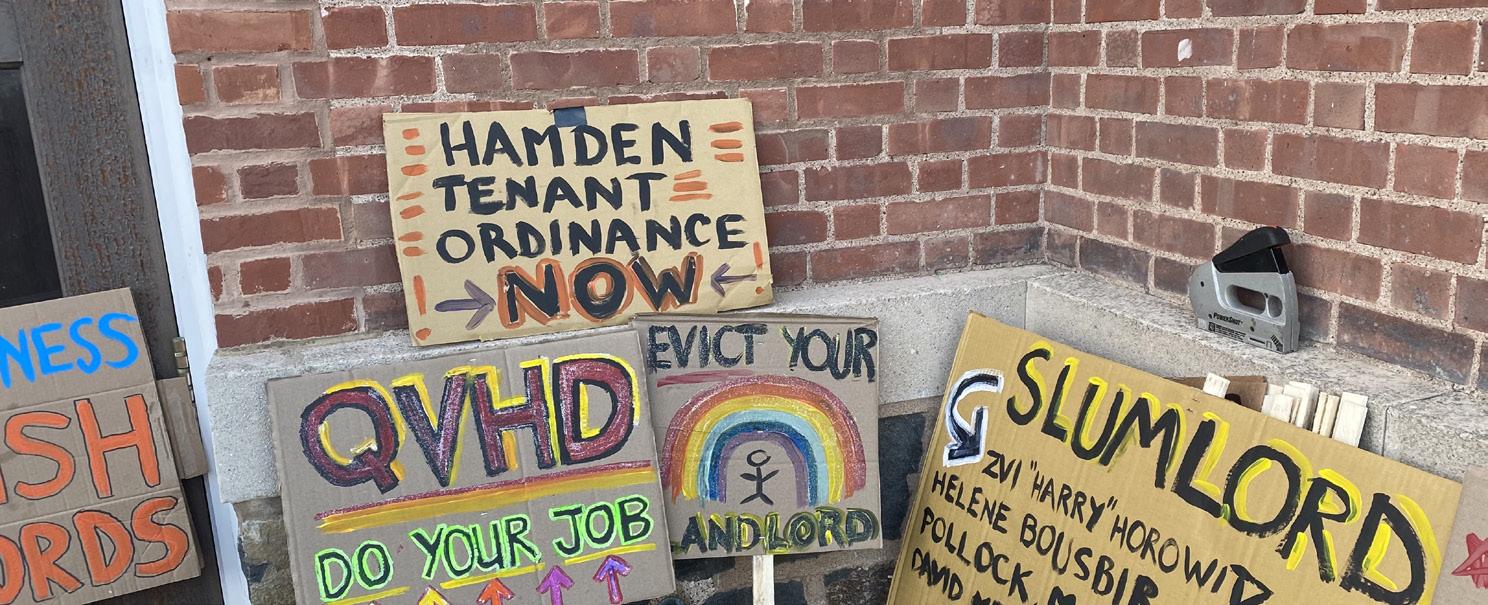

Tenant Chemistry

BY TYLER JAGER

In late August, 2021, in an eight-sid ed gazebo at the corner of New Hav en’s Edgewood Park, 41-year-old Alex Speiser joined a new organizing drive in what he described as a “leap of faith.” It was early evening, humid, and the weather was soupy. Speiser, a high school English teach er in Darien, Connecticut, walked from his home through New Haven’s Westville neighborhood, where he was due to meet three tenant organizers. ey belonged to the Central Connecticut branch of the Democratic Socialists of America, and they intended to prepare a half-dozen novices, Speiser included, for a “deep canvass.” In stead of a pitch to join a cause, the organiz ers wanted to knock doors, hear residents’ anger about poor housing conditions, and identify potential leaders among the ten ants who could join future organizing ef forts. “We tried some role-play by acting out scenarios between tenants and can vassers,” one of the organizers, Luke Mel onakos-Harrison, recalled later. “I think we’ve re ned our talking points since then.”

Speiser, who o en pairs tortoise-shell eye glasses with a plaid shirt and jeans, avoided get-out-the-vote e orts in the past, feeling that the easy sells of preachy politicos too

closely resembled snake oil. e listening approach seemed more respectful and less intimidating. He was surprised by the in timacy of the Westville door-knocking. “I could hear the fear of those answering their doors, sometimes not even opening them, or opening just a crack,” he said. Some tenants in his rst building were willing to share stories of rent hikes and mainte nance delays. In other units, though, all he could do was peek through the dark door slits leading to darker hallways, punctuated by ickering lights and the in termittent beeping of expired re alarms.

He suspected that people hid the truth when they said, “Oh, everything’s ne.”

at rst gathering in Edgewood Park led to a weekly canvassing routine, and that routine represented the “embryonic stages,” in Speiser’s words, of a full- edged Con necticut Tenants’ Union (CTTU), which is the only statewide ‘tenant union’ in Amer ica at present. A loose coalition of renters’ associations, individual tenants, and erst while labor organizers, the CTTU is part of a broader movement to shi power from landlords to tenants caught in the squeeze of American housing, through ‘tenant unions,’ which have emerged in more than

GAVIN GUERrETTE

a few U.S. cities since 2020. Renters who be long to the union “demand stronger rights for stronger rights for tenants; an end to displacement, landlord harassment, and eviction; and democratic control of our housing,” according to the group’s website.

Even among other tenant unions, the CTTU stands out for its willingness to embrace heterodoxy. eirs is a process of constant experimentation, mixing po litical lobbying with digital media savvy, avoiding the pitfalls of risky rent strikes, taking advantage of public hearings and under-resourced city agencies. Most cen tral to their cause, though, is e orts to form community between neighbors in dilapi dated apartments—classes of renters who, despite living down the hallway or across the street as tenants of the region’s sever al mega-landlords, have o en never met.

Speiser describes himself as a once “typi cal liberal Democrat” who shi ed course a er Sen. Bernie Sanders’ rst presidential run in 2016. In the a ermath of that cam paign, he is convinced that the tenant union o ers one alternative vision for grassroots politics—especially since he’s met Mel onakos-Harrison, whose friendship has

INSIGHT 28 | October 2022

With unorthodox advocacy and organizing tools, the Connecticut Tenants Union is paving the way for a national movement to shift the power balance of American housing. But can they build the community necessary to succeed?

//

proven especially fruitful for experiment ing. “One year ago, I knocked on my rst door,” Speiser told me. “I would never have guessed I’d be here, still doing this, today.”

can’t be replicated as easily as switching one credit card company for another. To lose that intimacy, against your consent— notwithstanding the scarring e ect of an eviction notice, or late payment, on your credit score—can potentially mean los ing your health, your humanity, your life.

new home, the case management didn’t stop: landlord neglect, and routinely dis mal public housing conditions, were the root problem. “You wouldn’t believe how many of these houses had bedbugs,” he said.

In 2020, in the wake of national eviction moratoriums, shutdowns of utilities and maintenance o ces, and calls to cancel rent, new “tenant unions” formed in Boston, Los Angeles, Kansas City, Washington, D.C., and notably, New Haven, to protect renters. In New Haven’s metropolitan area, where low- and middle-income residents su ered from poorly maintained housing stock long before the COVID-19 pandemic began, the demand for change was particularly acute.

e attraction of a tenant union is simi lar to a labor union, at least in theory. To gether, tenants provide a collective power that individual attempts to address hous ing concerns can scarcely match. Col lective bargaining can also mean lever age over one’s landlord, if tenant union members were willing to withhold some degree of rent in exchange for demands.

Yet di erences between labor and tenant power can make the latter far more precari ous. Tenants can’t appeal to a federal agency for registration and protection of a union in the way that employees can, through the National Labor Relations Board, a er an election to unionize. In most U.S. munic ipalities, city governments and landlords have no obligation to recognize a renter’s association—and rent strikes can be rem edied in some states, depending on their eviction and retaliation laws, by replacing the unruliest tenants with others who are quietly willing to pay. e biggest di erence may be that tenants in a building, by paying rent, are consumers of a good rather than workers employed to produce that good. In that sense, they have more in common with the consumer protection organizations that serve as watchdogs over banking and cred it, consumer privacy, or food inspections.

Rent, of course, is no mere bank withdraw al or food inspection. e intimacy of home

In July, 2018, Greta Blau, a six-year tenant in an apartment complex named Sera monte Estates in Hamden, began to docu ment numerous health and safety hazards in her building: toxic black mold, ood ed basements, and front doors that didn’t lock. Blau, who is y-four, has asthma and received treatment for breast cancer last spring. She noti ed a Hamden health maintenance inspector, Ryan Currier, about the hazards in June, 2021. Currier told her to inform Northpoint, the owner of the complex. Mold and water damage continued to appear, Blau told me, in units where families with young children lived.

“We were trying to g ure out how to do this when I started reading about one of the Brook lyn tenant unions,” Blau’s husband, Paul Boudreau, recalled. e couple reached out to Justin Farmer, one of Hamden’s city council ors and a member of Central Connecticut’s DSA, with the idea of forming a similar organization. Farm er connected them to Melonakos-Harrison.

Before his involvement in tenant organizing, Luke Melonakos-Har rison M.Div ‘23 was an outreach worker for unsheltered indi viduals in San Diego, California. e posi tion consisted of “trying to put Band-Aids on the gaping wounds of our society—of chronic street homelessness,” he said. He recalled that, once he found his clients a

Redirecting his attention toward preven tion before case management, Melana kos-Harrison joined what later became the Connecticut Tenants’ Union in late 2020. At that point, the organization was a mere outgrowth of Central Connecticut DSA’s housing justice working group. At the time, the prospect of a broader, state-wide tenant union seemed “a daunting task,” he said, giv en that no examples of such a group existed.

But interest was rising. In March, 2021, one organizer, Alex Kolokotronis GSAS ‘23, who studies political theory, put together a history lesson tracing a century of activ ism in New York’s urban housing districts on the Connecti cut DSA’s Youtube channel. In America, Kolokotronis noted, tenant unions were at least as old as ten ement housing itself. e former result ed from the latter’s overcrowding, as ris ing rents and poor health conditions in New York’s im migrant-dominated tenements spurred radical political or ganizing in the early twentieth century. (“We are asking you not to hire rooms in that house,” res idents of the Lower East Side wrote in 1904 on a sidewalk card, in Yiddish and English, during a general rent strike led by young Jewish women. “We want to put a stop to it once and for all. Keep away.”)

By January of the next year, the renters at Seramonte Estates, led by Blau and Bou

INSIGHT Yale Daily News | 29

Most central to their cause, though, is efforts to form community between neigh bors in dilapidated apartments — classes of renters who, despite living down the hallway or across the street as tenants of the region’s several mega-landlords, have often never met.

dreau, began to organize. In February, they hosted their rst canvass. While the temperature was freezing, Blau said, “It was really surprising, because I liked it.” Many of the residents were isolated in the complex, and “it was amazing to talk to somebody who’s so alone. Today, mem bership in the union at Seramonte Es tates encompasses more than 250 tenants.

media and public o cials to poor housing conditions—or at least, they were during an eviction moratorium dating to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Once those moratoriums ended, the costs for tenants who participated in a strike grew: eviction, an a ected credit report, a lawsuit from their landlord to obtain the le over rent.

public hearing, a er a tenant les a com plaint. While a complaint is under con sideration, the Commission can choose to suspend payments or freeze a tenant’s rent to its former amount before the increase.

For a DSA-born alliance of graduate stu dents, labor organizers, and low-income renters, the rekindled interest in tenant unions around the country—as well as local independent e orts like those of Ser amonte Estates—o ered sources of insight. e Connecticut organizers invited a speaker from the Greater Boston Ten ants Union to compare strategies and provide training. ey consulted a thirty-page handbook entitled “No Job, No Rent: Ten Months of Organiz ing the Tenant Strug gle,” created by Stomp Out Slumlords, a D.C. tenant union and advo cacy group that formed in 2018. e handbook bemoaned “the rituals of liberal NGO politics,” celebrating instead a “ca pacity for direct action” and change driven from below— capacities that also appealed to tenant organizations across Connecticut.

e handbook’s assumption that more rad ical, grassroots, tenant unions would clash with other NGOs was perhaps unsurpris ing, given its origins; Stomp Out Slumlords themselves le the D.C. Tenants Union in September, 2020, due to creative di erenc es. Yet their strategy of going it alone was risky, particularly when rent strikes were involved. On the one hand, strikes in D.C. were successful in bringing the attention of

e Connecticut organizers suspected that New Haven could present a smooth er route. In D.C., “you couldn’t just call up your Alder like you can in New Haven and set up a meeting,” Melanakos-Harrison said. “Here, there’s thirty of them in a small little town.” With fewer de grees of separation between Alders, tenants, and city agencies, more avenues and le vers of power were available to tenant organizers— nes, court lings, and calls for great er regulatory funding. Once the Connecticut eviction mora torium expired in June, 2021, the union would need any insti tutional leverage that it could nd.

Building that leverage would mean target ing two institutions: the Livable City Ini tiative (LCI), and Connecticut’s Fair Rent Commissions, which are present in New Haven and some surrounding towns. LCI, New Haven’s housing code enforcement agency, provided tenants an avenue for l ing individual complaints about housing codes and conditions—although timely response and enforcement was another story. e Fair Rent Commission, formed in 1984 to “control and eliminate excessive rental charges on residential housing,” ac cording to the city’s website, can initiate a

e CTTU sees both agencies, with respect to their funding, personnel, and legal pow ers, as potential levers that can shi pow er into tenants’ favor when grievances or rent increases arise. Melonakos-Harrison thought the Fair Rent Commission was par ticularly under-utilized: in 2020, the Com mission nally hired another employee in what was previously a one-person o ce.

As I spoke to more organizers, another dif ference of New Haven struck me besides the city’s size: the structure of the proper ty market was distinct from larger cities too. Extractive landlords are abundant in New York and Los Angeles, but those cit ies are large enough that no one (or two, or three) property owners can corner the market quite like they can in New Haven. For the past decade, housing in Connecti cut’s third-largest city has been dominated by three competing rms: Ocean, Pike, and Mandy Management. As the Independent reported this March, Mandy Management a liates purchased 558 apartments in New Haven in 2021; Ocean Management at tempted to sell 399. Rentals in New Haven are a seller’s market, even as many prop erties are labeled as “distressed” housing stock. Low- and middle-income residents, regardless of industry or employment, have little choice but to rent from them.