Abigail Sylvor Greenberg

Oliver Guinan

Margot Lee

Idone Rhodes

Associate

Kinnia Cheuk

Gavin Guerrette Wilhelmina Graff Zack Hauptman

Hannah Han

Audrey Kolker Isabel Maney Olivia Wedemeyer

Creative Director

Catherine Kwon

Design Editor

Christy Lau Photography Editors

Gavin Guerette

Yasmine Halmane

Tenzin Jorden

Tim Tai Giri Viswanathan

Jessai Flores

Ariane de Gennaro

Lucy Hodgman

Publisher

Olivia Zhang

What

At stake in this question is not only why you ought to keep reading, but also our clarity of purpose. We are asking because, while it is our job to showcase the work of our peers, it is equally important to state the values according to which we do. Every organization happens just in case of some reason, a unifying trait or principle. What is ours?

One answer is that the YDN Magazine is a paper volume printed by TCI Press in Seekonk, Massachusetts and delivered to Yale’s campus. That answer explains how it found its way into your hands. We think a more interesting answer, however, would explain what the Magazine is with reference to the work between its covers, how it is constituted. That’s the kind of answer we’ll give here.

Our magazine is at once for and against the Yale Daily News. It is for the News because we are the news. We and our staff work alongside the hundreds of reporters, editors, illustrators, photographers, and producers who put together the Oldest College Daily.

But if the YDN puts its emphasis on the D and the N, we are most invested in the Y — or really, its homophone, the why. We know that the response to why is seldom didactic. Sometimes the best answer is even another question. It is a commitment to this ongoing line of questioning that unites us as a Magazine and guides toward creative, ambitious art and writing.

This issue is the first of our tenure as co-Editors-in-Chief. Our talented staff of editors, designers, writers, and photographers have made this process both joyful and meaningful. We are tremendously grateful for their diligence and commitment.

Inside, you’ll find a variety of pieces that explore the border between myth and reality. Our cover story, “Sacred Rites,” by Naina Agrawal-Hardin dives deep into the vaults to expose the history of initiation rituals in Yale’s clubs, fraternities, and senior societies. In “At the Heart of Things,” Olivia Wedemeyer goes to the Grove St. Cemetery and digs up the literal and figurative bones underneath Yale’s grand edifice. Eli Osei’s “Finding Panjo” searches the South African roadside for a storied tiger, and David DeRuiter’s “The Real Thing” blurs metaphor and meaning.

In all, our writers show that compelling answers are grounded in not only the world we inhabit, but also the many worlds we imagine.

Thanks for reading!

Abigail Sylvor Greenberg and Oliver Guinan

College is a Joke COLUMN | Audrey Kolker 6

Kate's Music Beat COLUMN | kate reynolds 8

The Real Thing poem | david deruiter

The First Days of the War from the Perspective of Lydia Fomenko feature | kalina mladenova 10

Responding to Daffodils in Mexico City personal essay | Isabel maney

Finding Panjo photo essay | eli osei

At the Heart of Things: Yale's Life at the Cemetary feature | olivia wedemeyer

Sonnet POEM | cindy kuang

Watching People, People Watching culture | wilhelmina Graff

Sacred Rites: Initiation Rituals in Yale's Secret Sects feature | Naina Agrawal-Hardin

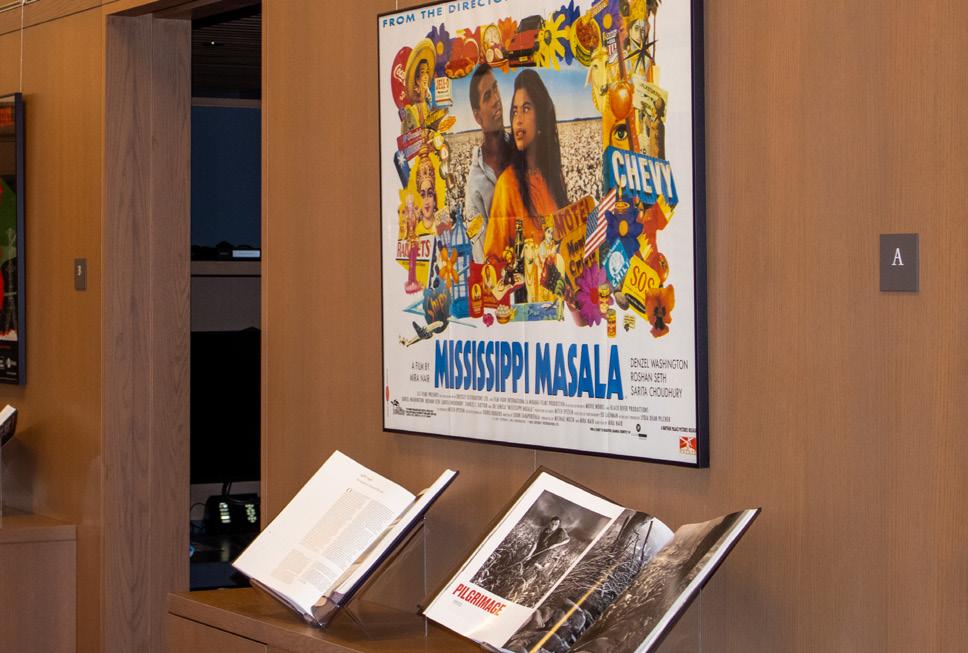

Yale's Motion Pictures are Moving Again culture | Abby Asmuth

The In-Betweens personal essay | kinnia cheuk

Cut to the Chase column | genevieve chase

IS

Who are the funniest people on Yale’s campus?

Jack Moffatt '25 is kind of tall, but he won’t say how tall. His hair is curly. His glasses are glasses. He can jump pretty high, despite the Lyme disease.

I met Jack freshman year, when the two of us were the blondest members of a ten-person suite at the top of Farnam Hall. It’s been an eventful fifteen months since then. Jack foraged: he brought five stolen signposts, two working hand sanitizer dispensers, and a ten-foot-long pole back to the suite. Jack conquered: he became a competitively ranked geometry tutor for students in Lithuania, he ranked 700th in the world in the online geography game Geoguessr, and he would have won JE’s game of Assassin if he wasn’t faceblind. Jack made allies: using unsalted almonds from the Bow Wow, he trained the Old Campus squirrels to sit. They repaid him with unflinching obedience— and at least one tick-borne illness.

When I ask how that illness is going, Jack grins. “It’s really great. I need a conversation topic sometimes. ‘Jack, what’s going on in your life?’ Aw, I have Lyme disease. It’s because I was too invested in meeting some squirrels.”

Not that Jack’s interest in animals is limited to rodents. In Florida, his home state, Jack’s favorite pastime is yelling at alligators; he once went viral on TikTok for making a math pun while holding six lizards. The pun? “My friend in calculus today was trying to take the integral of -csc(x)cot(x). Why couldn’t he do it? Cuz he can’t!” (The integral of -csc(x) cot(x) is cosecant). It’s terrible, sure, but the video captures Jack’s personality pretty well. By the time I graduate with a bachelor’s degree in reading books, Jack will have completed a master’s in mathematics and befriended the wild.

For Jack, it’s more exciting if the squirrels remember him than if other people notice him training the squirrels. He knows it’s funny, but he would still do it even if it wasn’t. Is this the key to humor—not caring either way? When I ask Jack if he thinks he’s funny, he shrugs. After two and half semesters studying Jack’s supernaturally excellent deadpan, I still can’t tell when he’s joking.

I once heard Jack describe another human being as a “lovely, lighthearted chap.” If we’re just talking like that now, then Jack is impish, bashful, and wry. Some of his expressions are so

exaggerated that they become farcical: a wide-swung snap, liberal use of the phrase “aw, jeez”. He speaks as if enchanté is flexible enough to capture every human emotion.

Jack often finds himself in strange situations. He thinks of them like side quests in a video game, or B-plots in a television show. “If you watch a TV show and the whole thing is just plot, that’s exhausting,” Jack says. “You need side plots to develop the characters’ morals and relationships.”

The side quest approach came in handy when he started college. Life became, in Jack’s words, “very plot heavy”; something needed to be done to make each episode unique. The main quest: Jack takes (or skips) graduate-level math courses, uncovering the secrets of the universe through equations. The side quest: Jack rollerskates eight miles to Quinnipiac University before learning how to break.

All this to say: Jack’s character is really developed. He spent a month memorizing the longest words in the dictionary for the middle school regional spelling bee. Then he was eliminated—on a short word. (What got you into spelling? “What got me out of it was ‘cashew.’”) Jack didn’t get into math until his sophomore year of high school. (Before that, what were you doing? “Being awesome.”) On a whim, he tried to solve one of the problems on

a mail-in math competition and realized it couldn’t be completed without learning calculus. So Jack did what anyone would do: he learned calculus, which turned out to be “kinda cool.”

I ask Jack to walk me through how he thinks about math. The answer is he doesn’t think. Jack used to have an internal monologue, but he decided the redundancy was slowing things down: “I had to fire the guy that was doin’ it.” His brain has been silent ever since.

“Sorry, what?” I say. Jack explains. “You know in Ratatouille when he tries the cheese and it’s good, and then he tries the grapes and they’re good, and then he tries the cheese with the grapes and it’s like fireworks?” I did know. “Imagine you’re thinking about a math problem where it’s so abstracted that everything is all fireworks.”

But talking to Jack never feels like talking to a pyrotechnic calculator. He gives his friends’ feelings and grievances the same attention and focus he might give a math problem. He’s been dating his girlfriend for over two years, and his room is filled with her crochet projects.

“The moral of the story,” says Jack, “is to make more side quests, so everyone can watch your life and say, ‘Wow, the writers are really good.’”

— Audrey Kolkerillustrated by Catherine Kwon

In each issue of this column, I’ll be talking to a new funny person at Yale—someone who, like Jack, couldn’t care less. If you think of someone, get in touch; email audrey.kolker@yale.edu.

Kate (she/her/hers) is a sophomore in Branford. She’s a History major and a diehard Willoughby’s fan. She joined the Magazine to Say Anything because she loves to listen to, think about, and share music. This column will focus on playlists: how we make them, name them, listen to them. Every column will look at a different type of playlist or a different dimension of playlist culture and try to figure out what’s in a list, anyways.

In the pivotal scene of the 1989 rom-com Say Anything…, John Cusack’s character, Lloyd, raises a boombox above his head and blasts Peter Gabriel’s “In Your Eyes” into the bedroom window of his forbidden love. The movie may have been lost to history if it did not include this iconic image.

“In Your Eyes” is a peculiar composition, mixing instrumental strings with electric guitars and choruses sung in Wolof, a West African language. It sounds like all the absurdity and cultural upheaval of 1989 in musical form. I was 16 when I watched Say Anything… with my mom, and the boombox scene was electrifying to me. The song was unlike anything I had ever heard before. I couldn’t tell whether it was love or hate–all I knew was that I was obesssesed.

Until that point, I mostly listened to hip-hop and R&B. There was no use in wasting my time with music adored by previous generations, I thought, when contemporary masterpieces like Kanye West’s My Beau-

tiful Dark Twisted Fantasy and Kendrick Lamar’s good kid m.a.a.d city existed.

“In Your Eyes” totally contradicted this belief. My mom sang along as it played in the movie, and I found myself wishing I knew all the lyrics like she did. The song made me determined to find more music that felt similarly new and exciting, even though it was released decades earlier.

I created a playlist on Spotify that night, named it “Say Anything,” and added Gabriel’s song. The playlist soon became my point of entry into a world of music I had never explored.

For months, I religiously added songs to “Say Anything.” The playlist is mostly classic rock from the 1960s through 80s, and it messily jumps between decades and continents, from bands to solo artists. It is home to Pink Floyd’s tortured “Brain Damage” and James Taylor’s quietly grieving “Fire and Rain.” It is full of contradictions and

artistic strife: it includes both “What Is Life,” George Harrison’s jubilant love song, and John Lennon’s “How Do You Sleep,” an excoriating criticism of Paul McCartney that features a traitorous guitar solo from Harrison.

Many of the songs that were part of this exploration were ones I had heard before, at family BBQs or on the radio. In listening to these classics on my own, though, I realized how much I was missing by overlooking rock music. I already knew the Eagles’ “Hotel California,” but when I heard it with my headphones in and mind open, I finally appreciated the strange lodgers profiled in the lyrics and the legendary guitar coda that closes out the track. “Hotel California” was soon added to the playlist.

There was no clear logic governing what music was added—admission to the playlist was based simply on my sense of transcendent connection with a song. I listened to Queen’s “Radio Ga Ga” and added it to the playlist because its use of synths and melding of disco and arena rock seemed so new and daring. “I Want to Break Free,” which I listened to around the same time, didn’t make the cut because I found it much less interesting or inspiring. It didn’t make me feel anything, and this was a playlist entirely based on feeling something, even if that feeling was ineffable. I opted to add Springsteen’s “Born to Run” but not “No Surrender” for a similar reason: “Born to Run” gave me goosebumps when I first heard it. That was enough.

The playlist’s messy, free-form nature was a reflection of my unique and often-contradictory musical preferences. It also influenced these preferences—as I played the songs in “Say Anything” over and over again, I realized I liked 70s’ folk rock a lot more than 80s’ disco, and guitar solos a lot more than drum ones.

The more I listened to these songs and refined my taste, the more curious I grew about other types of music. I started making playlists dedicated to other genres—folk, jazz, alternative rock—or other themes, like my favorite covers, best live performances, great samples. Whenever I tired of adding songs to a given playlist, I would create another one. After “Say Anything,” playlists became free-wheeling,

open-ended creative projects through which I could discover new music from the ground up.

The blank-canvas quality of “Say Anything” reflects the broader ways people in my generation think about collecting music. Some playlists are perfectly-manicured Pinterest mood boards, while others are curated more naturally, through random or arbitrary decisions about where songs belong. Playlists have limitless possibility; they are an art form that lacks definition.

This column is meant to dissect how and why we create playlists, and what they mean to us. Why are certain playlists public or private? Why do some people make playlists with their friends or playlists dedicated to every month? “Say Anything” was the first playlist that I had an emotional stake in—it was my entrance into the lifelong project of discovering my own music taste.

The final song in the playlist, “Domino” by Van Morrison, was added on December 2nd, 2020, only a few months after my project had been started. “Say Anything” is stuck in time, a collection of the very first experiences I had with artists who have become some of my all-time favorites, artists whose discographies I now know like the back of my hand.

It’s funny to think that a random song from a movie inspired me to explore these new music genres. The unexpected impact of “In Your Eyes” reflects how finicky music taste can be, how easily it’s swayed by serendipitous discoveries.

One of my most lucky musical moments was that “In Your Eyes” played from Cusack’s boombox at all. The movie’s director initially wanted to use “Question of Life,” a deep cut by the punk band Fishbone, for the movie’s iconic scene. “Question of Life” is grating, muddled, and exhausting—the opposite of romantic.

I always wonder what the version of “Say Anything” that was inspired by Fishbone might have looked like. Maybe it wouldn’t have existed at all, or maybe it would have revealed an entirely different side of my music taste, one that I am still waiting to discover.

As a person who is half Ukrainian and half Bulgarian, I have been haunted for months by the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War. My family from Poltava, Ukraine sought shelter during the war in Sofia, Bulgaria along with many other Ukrainian women fleeing the country. Telling stories of Ukrainian refugees in Bulgaria is important to me. I don’t mean casualty numbers and photographs of violence. Here, I wanted to tell a real story about people seeking a new beginning, a story that brings hope

Ifirst met Lydia Fomenko on July 16, 2022, when she was sipping a matcha latte on a quiet street in Sofia. This was the first time we met in person. We had only talked on the phone a few times. I had tried to imagine what she looked like, and for some reason when I saw her next to the fountain in front of the Museum of Sofia, I knew it was her. She was tall, slim, and beautiful. We went to her favorite cafe in Sofia. Back then, it had been five months since the war started and the summer months had brought Ukraine some victories.

“War? Really? This is not real,” Lydia began.

But on February 24 at 2 a.m., 32-year-old Lydia woke to the sound of a bomb hitting a building nearby her apartment in Odessa, “My heart went to my heels. There was smoke, and then light. It was the start of the war. We decided to leave the next morning.”

Her husband was in Brazil at the time. He works on a ship and would come home every four months. In Odessa, she was alone with her mother. Lydia’s mother was baking when Lydia went to pick her up that day. In the manner of a classic Ukrainian mother, she didn’t want to leave without freshly made food for the road.

“We packed the pirozhki my mother made, one bag each, and sat in the car; we were ready to embark on a journey that would take us to Bulgaria,” this is how Lydia described leaving Odessa.

First, they drove to Moldova, the closest neighboring country. They arrived at its capital, Chisinau, in the middle of the night. Without phone service, they drove around the city in search of a place to stay. A passerby pointed them to a nearby hotel, but it was full. People were sleeping in the lobby. The panic had started.

Tired after the road, Lydia and her mother were ready to sleep anywhere. The receptionist mentioned a Facebook post where Moldovans were welcoming Ukrainians into their homes, “We called one of the people who posted at 4 a.m.. We were scared, because we didn’t know if that man was actually going to host us or use us for something else. It was a risk, but we had nowhere to go.”

Along with these worries came more ordinary concerns germane to meeting a new person. Lydia had just been at a solarium the day before to work on her tan

and she worried about how she looked to their host: “This stranger was accepting two women into his home, and my face was burning red like a tomato. He probably thought I was crazy.”

The night passed without incident. In Moldova, Lydia was supposed to meet her husband’s family. But while his family was waiting at the Ukraine-Moldova border, there was a bombing. Lydia’s mother-in-law called to say they were stuck and that Lydia shouldn’t wait for them. Everyone had to turn off their phones at the border to prevent the unintentional emission of signals, since that might show the enemy that there are a lot of people there and potentially cause a bombing.

Lydia and her mother went on alone to Bucharest, Romania.

Relatives had told them to be vigilant there. It turned out to be a prescient warning. Lydia had booked a hotel online that same day. When they returned to their room after breakfast the next morning, their bag full of food was gone. Lydia immediately talked to the manager and it turned out that the staff had gone through their things, since they thought they had left the hotel for good. They got their supplies back and left Romania as quickly as possible.

After one night, they continued their journey to Bulgaria. Close enough to drive to and a part of NATO, it had always been their most desired destination. But navigation was complicated without the internet.

They stopped to ask a man for directions. Leaning on the driver’s window, he winked at Lydia and told her he could show her a shortcut to the border. Lydia drove away in disgust.

Two days later, they were in Bulgaria. Lydia’s mother had met a woman in a hospital in Ukraine whose daughter was studying in Bulgaria. She had reconnected with the mother while on the road to Bulgaria and had gotten the contact of her daughter. The young Ukrainian student had helped them find a host family through a Facebook group. However, when they arrived, the woman who was supposed to host them did not pick up the phone.

After several hours of calls not being picked up, Lydia decided to call her godmother. She lives in the US and according to her, they don’t have a good relationship, but she knew she could rely on her for help. “Booking a hotel in Sofia is expensive, so my godmother paid it for us,” Lydia said with relief.

They spent three nights in the hotel. During that time the Ukrainian student had found a new host family for them. One of the girls was her classmate in university. Their host family consisted of a few young college students, a dog, and a cat. They helped Lydia with everything, from finding the best coffee shops to fixing her car. Eventually, they helped Lydia get the perfect job— leading stretching classes at a new Pilates studio. Back in Ukraine. Lydia had her own sports studio where she taught every day, so being able to go back and teach was what would make her feel as if “life is normal again.”

Lydia started teaching twice a week, but the demand for her classes became so high, she added an extra session.

Life with their hosts was amazing. Lydia got really attached to the dog and the mother to the cat. These young Bulgarians became Lydia’s good friends and she trusted them wholeheartedly.

It is worth noting that Lydia was lucky to find hosts who helped her seek solutions to all her needs. For other Ukrainian refugees, assistance is far from assured. Bulgaria’s comprehensive structure of volunteer organizations, however, has been invaluable.

When the first big wave of refugees came,

the Bulgarian Red Cross had stations throughout the country. They provided food, water, blankets, and anything else that could be of immediate need.

Non-profit organizations such as Bulgaria for Ukraine and Karitas Bulgaria bear the rest of the load. Bulgaria for Ukraine, for instance, helps with anything from finding a baby carriage to assisting during evacuation. Karitas Bulgaria helps Ukrainian refugees with life after evacuation by helping them register as refugees, which grants Ukrainians refugees access to public resources.

It has now been five months since Lydia and her mother came to Bulgaria. Lydia showed me photos of the new apartment they rent together. Whenever Lydia comes home, her mother can always be found in their large kitchen, baking a cake with insane amounts of chocolate.

This is how they live together: two women, sometimes fighting, sometimes laughing, but always relying on each other.

Lydia has finally found some peace, despite all her troubles and her husband’s absence. He is stuck in Brazil, unable to make it to Bulgaria until his company finds a replacement for him. But for now, Lydia has found a community of other Ukrainian women in Bulgaria. They explore together, find hope for a new life, and enjoy the peace that Sofia offers. Returning to Odessa is a dream for now, but it’s worth dreaming.

They explore find hope for a new life, and enjoy the peace that Sofia offers.

together,

ELI OSEI

ELI OSEI

To grow up in Johannesburg is to grow up in a thought experiment. The city was conceived as a temporary town. A childhood there is defined by chaos and confusion. New-Democracy-themed birthday parties. Party-politics-themed democracy.

Forced to piece together Johannesburg’s identity before we had identities of our own, we were born responsible. Graduates of South Africa’s school of inexperience, life turned us into many people.

Some sanguine, some ignorant, others disillusioned. It was the 28th graduating class’ disillusioned who left their caps, gowns, and burdens behind in late June. Joseph said drive. Tiya asked where. Joseph said it didn’t matter. We made our way onto the road.

To come out of Johannesburg is to begin a journey into nothing. Dirt becomes grass becomes hill becomes mineshaft.

This part of the R51 is a money sandwich.Mineshafts as bread; road as filling. For as long as natural ground has been natural profit, we’ve had to stomach this meal. Along the road, the hopeful would stop for work.

Clusters of small towns litter the money sandwich. We drove past the homes that “once belonged to miners and now belong to people like Panjo’s owners,” Tiya remarked.

“Panjo?” I asked.

Tiya began: “Panjo’s a tiger. An actual tiger. But in 2012 or maybe ‘11 or maybe ‘13, Panjo began to dream. He was in the back of a pickup truck, on this very road.”

“Why?”

“Panjo wasn’t the tiger he once was. He used to roll and roar, but it’d been days since his owner had seen that gnashing smile of his, and a gloomy tiger doesn’t bring in the big bucks. So they left for the vet with a broken tiger in the back and arrived there with his broken chains.”

“What?”

“Yeah, he was gone. And it was this big thing, man. His owner was distraught. She phoned a radio station and was like, ‘Panjo’s gone, my poor sweet Panjo,’ and the host was like, ‘who?’ And when she’d gotten the details out, everyone wanted to help find him – to dedicate themselves to something, even fleetingly. And they did, after two days they found the little guy. He was on a farm just up this road. I’ll take you guys there. I swear it’s real.

They found him on this farm, alone, roaring, free, and they took him back into the city. He was happy out here. And they took that from him.”

Tiya stopped the car. A single sign separated fact from fiction, the fickle from the farm. It read “Panjo could have been here!” We got out and stepped onto hallowed ground. Panjo found purpose here. We found two windmills and a train track.

“This track could take you to the end of our world and the beginning of the next one,” said Joseph, “but no one uses it anymore.”

Back in the car, I looked out and counted cows. Joseph pointed to a building on the horizon that looked as out of place as us. Soon after, we arrived at Carnival City.

People come from far and wide to gamble in Vegas because Vegas is a gambling city. Brakpan, halfway between Johannesburg and Mpumalanga, was not built this way. Carnival City, Brakpan’s main attraction, is no city at all. People do not come from far and wide. They come from very close and they stay for very long. Carnival City is a casino belonging to the road.

If mine shafts rewinded time, this building froze it. There were no windows, no clocks, no mirrors. There were food courts, showers, and overnight rooms. One could live and die in Carnival City. Ready to live, we each forked over R50 and tried to take our first steps.

R25 was lost to the slot machines. R50 was lost to Texas Holdem. Disheveled and disappointed, we found ourselves at the Black Jack table, looking for a way to break even.

“Black Jack’s a simple game,” an unkempt gambler told us. “It’s us versus the dealer. I win. We all win. You lose. We all lose. He wins...” he sighed and thought a thought we would never know. “Play behind me,” he whispered.

And so we did.

Gazing through the cigarette smoke and past the inscrutability, one might declare that this was a family, if only for a moment.

“Look at that thing go,” a member of our makeshift audience said, “I could watch it spin forever.”

When we stepped back into our world, we were R150 richer, the sky was many shades darker.

We drove by the petrol stations where they once prayed for Panjo, back to the petrol stations where they prayed for lower fuel prices. We drove past the tracks and into the new abyss. A cow becomes a cow becomes a cow becomes a cow.

The road stays the road. It’s oblivion out. It’s oblivion in. There’s no meaning on the road. But the road raised us.

Kuang illustrated by Catherine Kwon

Kuang illustrated by Catherine Kwon

Yesterday, I found a dead sparrow with no legs, stump body left on Whitney street. Dirt-dry bird casting radius of filth: side-steps, side-eyes, meat hung neatly in heat.

Summer maggots in the eye—rotting breast, larvae in the chest. The pitter-patter, soft twittering of hatchlings in the nest, quiets into closed eyes. Devastations.

A realization, a mother’s last breath. Gilded wings by goldsmith hands, a weeping, belly-up, bent, beaten, sun-boiled life— Still. How lightly they fold for safekeeping.

She is wing-skirted and small-beaked. If I listen: wind is whistling through her bones.

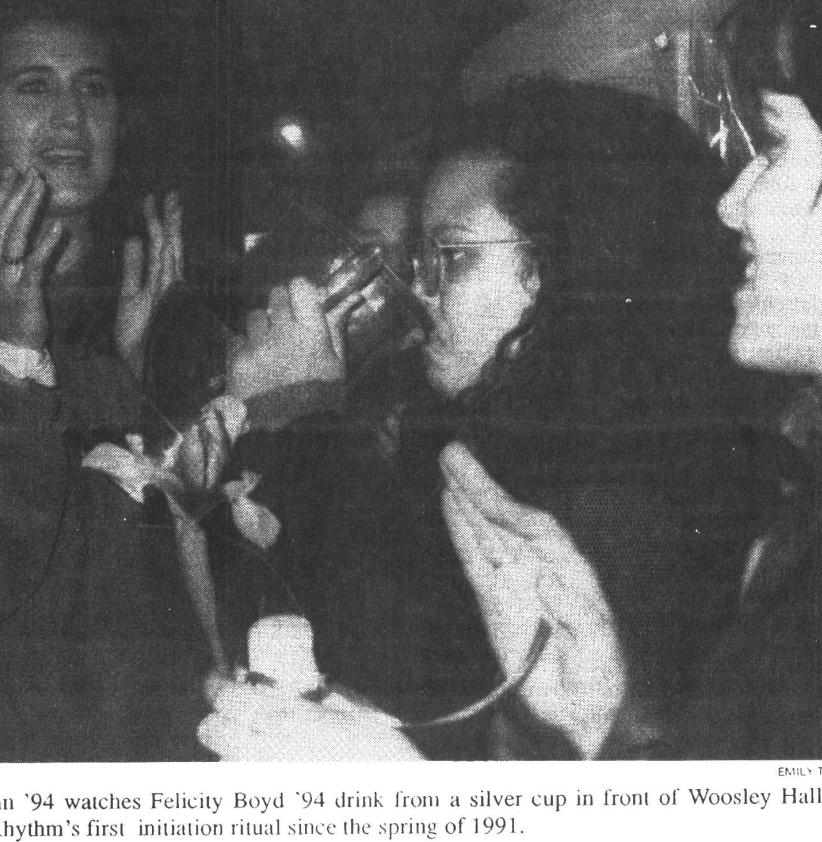

In the vast entrance hall of Sterling Memorial Library, intricate stained glass window panes depict iconic moments in Yale’s history. Among panes featuring Sir Isaac Newton donating books to Yale’s library and the execution of Nathan Hale, there is one scene which is often interpreted as a Skull & Bones initiation ritual. Several figures, cloaked in black, stand in the shadows of what seems like the garden behind the society’s tomb on High Street. In front of them, two more cloaked members push a hesitant character, presumably a new “tap,” towards an open coffin. Although the panel more likely represents the burial of Euclid, students’ tendency to interpret it as a nod to Bones speaks to how Yale’s nearly-mythic initiations are embedded in the campus psyche.

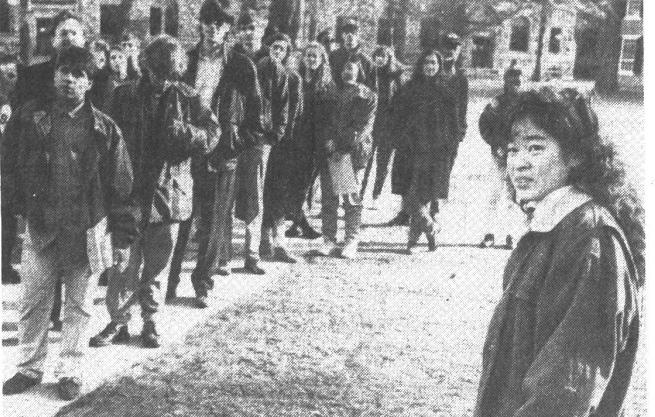

Initiations at Yale range from benign to bizarre. During the early ‘90s, a group of Ezra Stiles seniors regularly took the “polar plunge” by submerging themselves in the frigid Long Island Sound. These thrill seekers were members of the Polar Bear Club, an organization into which they were initiated through a ritual involving a bowling ball named Sarah. From then, initiates were asked to perform a “druidic dance” around the ball before their first dip. Sarah, Polar Bear members said, was “Neptune’s gift” to the club. Yalies are constantly confronted with the spectacle of initiation rituals like the Polar Bear Club’s. At once hyper-visible and shrouded in mystery, initiations at Yale are ubiquitous––nearly every prominent undergraduate organization has a ceremony of some sort. Josh Vogel ‘23, current president of the acapella group Society of Orpheus and Bacchus (SOB), says: “It’s not Yale if you don’t see a random group of blindfolded people walking up Science Hill in the middle of the night.” Some initiation traditions are nearly as old as Yale itself. Rachel Hardy, ‘23 (whose name was changed to preserve her anonymity) belongs to one of Yale’s prestigious “landed” senior societies––societies which own property on campus. “The members of our delegation’s outgoing class prepared a formal banquet dinner for us, at which they delivered speeches and gave us gold pins representing our society,” she described about her initiation last spring. Yalies have participated in initiation banquets since the 19th century, when academic societies like Phi Beta Kappa hosted elaborate dinners with decadent menus and esteemed “toastmasters” (usually Yale faculty and administrators). Similarly, newly initiated Yale seniors have been receiving society pins since the mid 1800s. An

1869 issue of the College Courant, a 19th century publication on American undergraduate affairs, reported that on the morning following Yale society initiation new members would start to wear their pins on the cravats of their neckties. Members of Skull & Bones were known to wear their pins every day, even after graduating. The pins branded initiates, signaling their membership status to the outside world. Non-affiliated Yalies described the pins as ostentatious and elitist, symbolizing membership in organizations which rewarded and reproduced America’s wealthy, WASP-y ruling class. “Realistically, the initiation ritual is elitist and I think meant to make us feel special for joining the ranks,” Hardy admits. The paid-for dinner and pure gold pins are flashy indicators––to new members and to their peers––of the society’s resources and influence. “But there’s also a fundamentally understandable instinct that it plays to,” Hardy says contemplatively. “People have committed to getting to know each other for the next year. Here is a fun and silly ritual to symbolize that commitment.” Hardy points out that many Yalies have a tendency to take themselves more seriously than they should. This is unsurprising, as the college self-selects for people who are accustomed to academic and extracurricular striving. Though some aspects of Yale’s initiation rituals heighten and reinforce a sense of seriousness, other elements introduce levity. After Hardy’s society banquet, she was blindfolded and led on a walk through New Haven. The night ended in an afterparty.

Building on the banquets and badges of the 19th century societies, Yale’s fraternities, singing groups, and sports teams have created initiation rites of their own. They supplement serious traditions with silly, spectacular, and even sinister ones. In the early 1900s, Yale’s now-obsolete junior fraternities, popular social spaces for college juniors, had a lengthy initiation period which began with “Calcium Light Night.” Robe-clad brothers carrying calcium torches paraded around Old Campus, collected new pledges, and marched them to their fraternity houses. This tradition, perhaps inspired by the robed “tap night” practiced by Yale’s senior societies, created a sense of collective, almost cultish identity for Yale men. As a public performance, it broadcasted new brothers’ fraternity affiliations, serving the same purpose as society pins in ritual form. 1937’s Calcium

Night saw broken windows, burning torches thrown into Freshman rooms, and beer poured into masses of letters in the campus mailroom. The practice was abolished by the Intrafraternity Council (IFC) later that year on charges that it was “riotous.”

In the years that followed, the IFC continued to regulate frat initiations. They became less public, save for the occasional controversy which surfaced in the YDN. In 1967, a student wrote a chilling account of the ceremony by which he was initiated into the fraternity Phi Gamma Alpha. The ceremony lasted nine hours, eight of which involved sitting naked on the floor without water or a bathroom break. A non-American pledge was forced to admit that his national flag contained “some obscenity.” Another pledge was beaten until he said that any member of the frat could sleep with his girlfriend. The ceremony culminated in a threat of hot iron branding and was used to intimidate the pledges into delivering soliloquies about their commitment to the fraternity. One pledge commented: “I was scared, but I said I would [accept the brand]. It was a relief to know that only physical pain would be required of me.” Despite efforts from the IFC, it was commonplace for fraternities like Phi Gam to practice fear-based rituals which challenged initiates’ physical limits. DKE (which is now back on campus after a four year hiatus following 2018’s sexual assault scandal) was notorious for physical beatings and verbal abuse. Beta Theta Pi brothers commented to the YDN in 1967 that harsh traditions were meant to deflate pledges’ egos after the courting they received during the rush process. The rituals established a rigid hierarchy within the organization and fostered buy-in: who would abandon a frat after enduring the physical and psychological toll of being initiated?

For most of the University’s history, the benefits of a Yale education were exclusively conferred on white men. Its initiation rituals reflected its demography: senior societies reinforced moneyed status and frats encouraged performance of masculinity. In the 1960 and ‘70s, the institution of affirmative action and the decision to admit women made Yale a more diverse institution. As Yale has evolved to include students of all genders, races, and class backgrounds, overtly sexist, racist, and classist practices have become socially unacceptable. At Yale and on campuses across the country which have undergone similar transitions, fraternity-style ritualized hazing has come under increased scrutiny for its patriarchal implications and dangerous physical consequences. Some Yale social organizations have adapted their initiation practices accordingly, emphasizing bonding and celebration over degradation.

A member of the Fence club, which originated as a fraternity and reopened as a coed space in 2004, shares: “Bonding is best done when everybody feels comfortable in the space.” Fence has recently eliminated petty theft and other activities that

could land initiates in trouble with Yale administration or law enforcement, partially because of a growing recognition that inductees of color could face more dire consequences than their white counterparts if they were caught breaking the rules.

Members of The Edon Club have had a unique opportunity to reimagine frat initiation. The still-new social club replaced Signa Phi Epsilon when the fraternity disbanded in 2020, inviting a wholesale reconsideration of which aspects of male Greek life could be preserved, and which needed to change.

Zoe Kanga, Edon’s Development Chair, was tasked with planning initiation for Edon’s most recent pledge class. She sought to make it a “celebration” of initiates’ completion of the Development process. In addition to traditions handed down from Ep––blindfolds, a candlelit path, a blaring Hans Zimmer song, and a shot of Everclear from a baseball bat (now optional!)––Kanga added the tradition of handing initiates their green Edon sweatshirts. Like society pins, these sweatshirts signal participation in Edon to the outside world. While most of Edon’s initiation practices come from its fraternal predecessor, the social club has dispensed with “over-consumption, forced exercise, and other activities designed to push physical limits.” Kanga contrasts this philosophy with the initiation rituals she’s heard about from fraternities at Yale like Sigma Nu and LEO, which she characterizes as more “masculinity-charged” and “mysterious.” Sig Nu and LEO remain all-male fraternities.

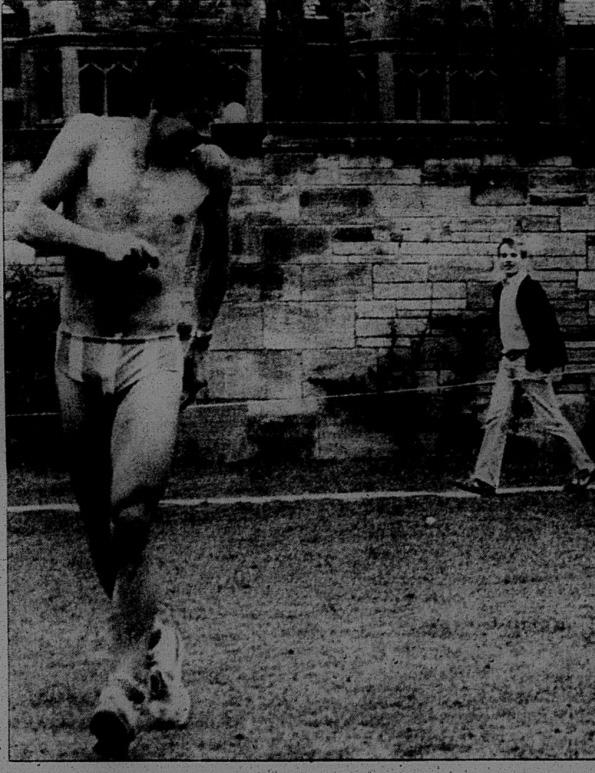

Like Fence and Edon, historically-male a cappella groups such as the Society of Orpheus and Bacchus have also adapted initiation rituals to emphasize respect and bodily autonomy in recent years. Vogel, the aforementioned SOB President, chuckles when he hears about old photos of SOB initiates stripped naked on cross campus in a 1994 YDN article. “We would not be naked in public now. We would try to avoid any activity that would be obnoxious to someone who has no choice but to put up with it, like a low-wage retail worker.” He adds that while SOB “neophytes” (new taps) may be pushed out of their comfort zones, “The SOBs never challenge people’s physical limits. [It’s not about] establishing hierarchy as much as about [expanding] the way that we interact with the world.’” Although Vogel is tight-lipped about what this might look like at present, in the ‘90s, it meant staging a mock wedding, parading around in sundresses on cross campus, and dressing up as Wizard of Oz characters––any activity that initiates wouldn’t engage in outside the context of initiation. Vogel points out that stretching comfort zones plays a special role for a performance group: “You can literally see people shaking on stage sometimes when they start out.” Strange challenges and mysterious tasks force new members to place trust in each other and take risks, which in turn makes them more confident performers.

Sports teams navigate similar questions about hazing and alcohol consumption, also opting for traditions geared towards bonding. Colin Quinn, social chair of the Yale Track Team, has fond memories of his initiation: “It consisted of a track-themed scavenger hunt with different stations and a lot of drinking stuff, which was optional.” He smiles with a mix of pride and sheepishness: “Every year someone’s sick with, like, mono, and you win the scavenger hunt if you take a shot with whoever’s sick.” On initiation night, the team splits into groups of 5-6, and each group is assigned a recognizable costume theme like Mario Kart or Star Wars. The costumes turn the scavenger hunt into a spectacle for bystanders. The randomized groups, Quinn explains, allow runners from different disciplines (throwers, jumpers, sprinters, distance runners, and cross country) to get to know each other. In addition to unifying across disciplines, he also explains that track initiation “Removes the tension that there would be with drinking and track culture. [Through initiation] people realize that it’s okay if you want to [drink], but you don’t have to.” Some of Track’s traditions, including the costumed scavenger hunt, are fairly new. Quinn harbors suspicions that a recent graduate adopted many of the track’s current traditions from WYBC. But others are decades old: every year a freshman is made to give a speech atop a shed after being selected by the person who did it the year before them.

Alexandra Stone graduated last Spring as a member of one of Yale’s oldest three secret societies. She coyly discloses two details about her group’s initiation tradition: it involves submergence in a large body of water and dressing up in full suits of armor. “For me, college was very much about ramen noodles and reading,” she says. By contrast, witnessing initiation was a “rare experience to experience deep mystery and excitement.” Yalies crave experiences like Stone’s, which she describes as “a secular religious experience,” because they offset the insecurity that we’re not doing Yale the right way.

Some of the only groups on Yale’s campus without initiation rituals are those which have no formal application process or hierarchy. Tara Bhat, an organizer with the Endowment Justice Coalition, believes that initiations at Yale create an “ingroup” of people with close organizational ties. Explaining EJC’s lack of a ritual, she says: “The goal of [EJC] is to make everybody feel welcome whenever they feel they have the capacity to contribute. Having an ‘ingroup’ would be divisive.”

In the absence of organizational hierarchy, there is no need to distinguish between “official” and nonofficial members. When buy-in is expected to waver over the course of a semester or year, there is no need to solidify it through an initiation. In fact, such a ritual might actually be counterproductive. Like Yale itself, many of

Yale’s most popular student organizations derive their desirability from their exclusivity. But for the few organizations that position themselves in opposition to Yale’s brand, power comes from numbers, not prestige.

Outliers notwithstanding, an overwhelming proportion of Yale clubs––including many of the most niche organizations on campus ––practice rituals of some sort. For decades, the Yale Carillonneurs were known to host a highly secretive initiation ritual each January. According to one carillonneur, the ritual served “dual purpose: to [break] the ice between the group and the initiates” and to “cause the absolute most embarrassment possible.” In the ‘80s and ‘90s, the Yale Tour Guides initiated their new, competitively selected cohorts by making them drink prune juice, leading them to Abrahamus Pierson’s statue on Old Campus, and sending them through a time trial through the usual tour route, along which existing guides were stationed to ask them obscure questions about Yale’s history. In 1990, they added a tradition called “tape night,” where current guides taped prospective guides together and paraded them through Sterling and down Wall Street. Group members back then were careful to emphasize that the ritual was not “hazing,” but rather intended to “introduce the new tour guides to ourselves and each other.” Members of the 2022-2023 Tour Guide class said that they no longer employ that ritual.

Some organizations––The SOBs, Edon, Fence, Track, Tour Guides, and more––have made significant chang-

es to their rituals in recent decades. These changes correspond to a number of factors: what students find fun, what students find acceptable, and where students strive to secure “official” membership. Yet other, older organizations have steadfastly practiced the same initiation ritual for as long as members can recall. Because of COVID, Stone was initiated for her society via Zoom. Nevertheless, she knew exactly what to do when tasked with planning the next delegation’s in-person rites. “Our initiation process is handed down to us from on high. It’s set out in great detail.” Prestige, power, and resources make it both more appealing and more logistically feasible to strictly adhere to traditions once practiced by now-famous alumni (William F. Buckley, George H.W. Bush, Edward & William Harkness, and many more notable grads participated in societies like Stone’s.)

Initiation rituals, whether for a social club, a sports team, or the Ezra Stiles Polar Bear Club, appeal to the sensibilities of students who appreciate tradition and strive to feel elite. Reflecting on her recent senior society initiation, Hardy says: “I think a lot of us here like the idea of initiations because it takes the guesswork out of belonging. Many of us spend a lot of time and energy on figuring out the niche that makes us valuable enough for society, for Yale, for our communities, and the initiation is a reassuring process, one that tells you that you’ve been chosen.”

It was bingo time at Yale’s Orientation for International Students, and my groupmates had yet to write a name in the box for “a person who speaks three or more languages.”

“Wait — Kinnia, don’t you speak English, Cantonese, and Mandarin?”

“Yeah, but it’s more like 2.5 languages… you know?” They wrote my name in the box anyway, and I was left wondering how I had arrived at the number 2.5. I was pretty sure that Cantonese was the 0.5 — I just wasn’t sure why.

Growing up in Hong Kong meant that most of my classes were taught in English besides six years of Chinese classes in Mandarin, but I spoke Cantonese — my native language — everywhere else. One Friday afternoon in seventh grade, I left my Chinese class unsettled. I sprinted back home, desperately Googling the prosodic rules of an cient Tang poems on my

sluggish Samsung Note — all because my teacher had commented on how these poems were meant to be recited in Cantonese, not Mandarin. Bursting into the kitchen, in a twelve-year-old’s piercing soprano, I started a fervent reading of Wong Wai’s “Yearning” in Cantonese. My mom was unimpressed, even after my five-minute lecture on how, prosodically, Cantonese makes

the poem that much more meaningful. Scoffing, she said: 「相思你識條鐵

咩」 (loosely: “what the hell do you know about yearning?”). In that moment, though, I felt like I did know what it was like to yearn — for validity, if not anything else.

I tell this story a lot; I enjoy how idiosyncratic and defensive it makes me seem. In the years since, I’ve picked up the habit of writing in spoken Cantonese (which makes use of the universal set of Chinese characters and some more niche, Canto-specific ones). This habit is like microdosing the drug that is unsolicited Cantonese poetry in the kitchen; I feel real, and illicit, when I do it. I almost never see spoken Cantonese written out officially, as TV captions or in government papers; Mandarin is always employed as the standard written form (which, in itself, represents a kind of superiority: there’s no fear that it will ever be lost in the tides of time).

Nonetheless, this drug has taken its toll on me: I have never felt as incompetent as I did one night, sit-

ting cross-legged on my wobbly dorm chair, nervously chewing the tip of my pencil while helping my friend with her L3 Chinese homework. Embarrassingly, I wasn’t sure about the “official” written syntax which I knew her instructor must have expected; Beijing Mandarin, after all, has nuances that differ drastically from the Cantonese structures I am used to. I never toldv anyone how I labored over the Mandarin speaking portion in Yale’s Chinese placement test (I emailed to ask about protocols for native Cantonese speakers, only to find that Yale didn’t have a system for recognizing spoken proficiency in Chinese dialects), and, after twenty discarded voice recordings, settled for a garbled fusion of Cantonese and Mandarin pronunciations. Beyond feeling sorry for my Mandarin teachers in primary school, I also sensed that, in some way, I had failed to live up to my roots. If I couldn’t even help my friend with her Chinese homework in America, or express myself coherently on a test that was specifically designed to test Chinese abilities, what did I have

apart from the impassive label, “Chinese,” on my passport?

Probably noticing how I struggled to correct her grammar, my friend turned to me and said, “It’s OK to not know Chinese perfectly — you’re an English major anyway!” It was clearly meant as a gesture of comfort, but it really hurt — in ways that I am only beginning to understand.

During family dinners, my grandma has told me, with an emphatic nod, 「讀英文好」 (“being an English major is good”). And I agree, especially the part of me that’s still thirteen and beaming onstage at school, clutching my certificate for “Best in Form for English.” But where does this pride come from, exactly? My parents like to recall how, thirty years ago, when Hong Kong was still a British colony, knowing how to English was the only skill you need ed in the job market. English was the language of royalty; it was spoken in “rich people plac es”— areas where Western expats worked and drank — while Cantonese prevailed in the wooden slum villages my dad lived in. So I guess my family is proud that I am an English major, not because they necessarily value literature, but because it was and still is an achievement to speak

the language of our colonizers — and to speak it well. So it goes: another authority, another “official” elite language, but the same illegitimate space that Cantonese is boxed into.

Sometimes, even I wonder whether the language I speak is legitimate. It’s a colonial debt we never repaid: my grandpa used to own a si6do1 (“store”), I take the dik1si2 (“taxi”) when I’m late for school, and my favorite drink is so1daa2 (“soda”). The words I speak are in-betweens, echoes of a language I do not own. Is it not tragically fitting that I, being in love with the real deal, am studying English in America?

In my senior year of high school, we studied Pai Hsien-yung’s Death of Chicago. After completing

main character 漢魂 (literally “Chinese soul”) realizes that he does not know how to reconcile his abstract knowledge of Western literature with his Chinese identity — he spirals into depression, ultimately ending his life in Lake Michigan. By then, all my classmates knew I was planning on majoring in English in the US; this ensured that I was consistently the topic of discussion (and the butt of many insensitive jokes about suicide) in Chinese class. I would always respond with “the bodies of water in Connecticut are not picturesque enough” — but even then, I sensed cultural betrayal looming over me like the fog over Victoria Harbor in spring. My impending betrayal had been easy to ignore when I was confident enough in my own English abilities, yet lately

I’ve been feeling like I have no right to speak in English classes at Yale, with my weirdly phrased sentences and jumbled thoughts. Last Wednesday, my suitemates and I were jaywalking outside our college; we were so engrossed in a discussion that when a gray Toyota came speeding towards us, no one noticed but me. In a moment of frenzied panic, I screamed in the middle of the road, 「睇車啊!」 In my mind, this fleeting moment of unabashed Cantonese in the middle of New Haven is engraved as an eccentric diary entry I always return to; it is relieving to know that Cantonese is still my go-to during emergencies. The phrase was useless though — no one understood me. As the Toyota streaked behind us, my suitemate yelled in Mandarin 「你說啥?」 — I yelled back (in English) “Nothing!” and chuckled to myself all the way to Sterling. When I speak, I settle — as my ancestors did — in the in-betweens, the illegitimacies. As I’m writing this, I’m thinking about how, in Cantonese, 寫, 瀉 and 捨 all have the same pronunciation; therefore, to say that I write is to say that I spill, which is also to say I experience diarrhea, which sounds exactly like I sacrifice. There is a brutal sense of tragedy: if I give up something on either side of me, does it mean that I will be saved from the chasm in between?

Driving is good.

It is the right thing to do in most cases. It pushes spots together like a cross-eyed boy.

When you drive, your toes are the edge of the world, your eyes a periscopic angle of the rest of your life.

You whir past things, okay?

You grumble clear of woven lakes, better than their fishes and frogs.

You trample things, opossum and squirrel, which fight like hell the urge to wait their turn, use a crosswalk, behave like normal— no, the vermin jaywalk then freeze.

Here you may stop to feel their shapes beneath the chassis, but then you must start again. Okay?

Look, though, you can play this quiet kit! Crush these pedals like thirsty leaves beneath you or tease them apart like the hairs of a handsome boy. The lights are the same, either all too much or nothing at all: a giant bullet streaking through the yellow stripe, what fun!

And if you play it just right, the best machine cocks its mirrors and shows what you’ve left behind— this is my favorite part.

Driving is a tired boy who snaps a dry apology. He is confounding and dangerous, I think. Nobody knows him like you, I think. He gives lazy gifts, never what you want, but he is fit and smooth and every button caves to your fingers.

He purrs when you press. He blinks like the real thing.

When you drive, you get where you’re going. For every hour spent peering over wheels, panting at the heels of a thousand custom-license-plates, of accidents-waiting-to-happen, you are saving yourself the filthy exhaust pipe of feeling these moments as they—jesus, feel it now, how you gulp at breath like the fishes and lakes, fuck, There is more to life than this, man!

Driving is safe. It is missing your exit, clucking your tongue. You flick your blinker and drift across the lane like a family dog. You’ll take the next one, you think, and All at once you do.

In the early-August morning, I went to Polanco. The neighborhood was a thirty minute walk from where I lived in Lomas. On the corner of Jules Vernes and Ibsn, (an intersection typical of the neighborhood, where streets are named after authors), a flower vendor had set up his six-by-five stand in the shade to avoid the sun’s wilt. The man held out sunflowers, calling them girasoles. “¿Unas flores, señorita?” he asked. Seeing that I was not interested in the ones he had chosen, he picked up another bunch. “¿Violetas?” he inquired. “¿Astromelias?” He took them out so that I could see the drooping pink petals. “Narcisos,” he finally said. I felt the name with a pang but could not recall its English translation until he held up the yellow bouquet. Fair Daffodils. With delight, I paid for the flowers thinking of Robert Herrick. Herrick was an English poet who once wrote, "Fair Daffodils, we weep to see / You haste away so soon."

The day’s warmth was a reminder that the first week of August would soon pass, and with it, the summer. I glumly threw away the daffodils at the end of the week, remembering Herrick again. The withering of the daffodils also brought the start of the school year. Now, I think again of Herrick and summer’s daffodils. We have short time to stay, as you.

I’ll remind you again, since I have to keep reminding myself: the month is now October. At least, it is October as I’m writing this at a corner table in the Trumbull Library. The room is decorated in the usual collegiate gothic style. Deep burgundy furniture encloses dark-stained tables. Thick carpets cushion the wooden floor. An empty stone fireplace centers the bookshelves. The room, designed to protect against winter, gives the impression that it is waiting for winter. We are waiting along with it.

When I find myself thinking of the coming season, I turn not to Herrick’s poems but to the writings of Elena Garro. Garro is a Mexican writer credited with pioneering magical realism. Her most celebrated novel, Los recuerdos del porvenir, was published in 1963. It is translated to English sometimes as Recollections of Things to Come and other times as Memories of the Future. I prefer the former because of how clearly it presents the irony of Garro’s work. To recollect is to hold a memory or already-visited place with you in the present time. To recollect something that has not yet occurred, something that is to come, requires the opposite action, to entertain a factionalized future, crafted in the present.

feel like constant travelers who are pulled from place to place with the change in weather.

It is by this change, the annual fall of leaves, that I’m brought to remember my time on campus last year.

Confession: I left Yale before the end of the 2021-22 school year, my freshman year, because I couldn’t stop myself from imagining what it would be like to go. The memory of how this plan originated is still clear to me. I spent my freshman year in one of many red-brick buildings along an expansive lawn nestled with oaks and statues called Old Campus. We have short time to stay, I thought moving into Bingham in August, already fearing that my four years of college would go by in a blur. As Herrick kept watch over his daffodils, I looked over the Old Campus oaks, measuring the passage of the year through their changes. I believed myself to still be firmly within fall as I walked back to campus on a late-November afternoon, just as the Branford bells began their toll.

as to where she sits, unsure if she is observing what is around her in the present or looking over a memory.

How curious, no? The progression of seasons, one constantly pushed by another so that it is impossible to set myself firmly in time. I confuse the waning of one thing for the beginning of another. The character of the seasons seems to dominate whatever uniformity might come from living in one place. New England cities with four distinct seasons make residents

While returning through the same gate the next day, I felt peculiarly that I had been gone a long time although I had left Old Campus only that morning. It was at least seven degrees cooler than it had been all week. A steady wind, too, left the lawn much emptier than usual. Only the previous afternoon, an unusually bright and warm day, athletes had amused themselves playing catch. Nostalgics rested in grooves for an hour or so of meaningful poetry. These collegiate rituals, always picturesque, were set among the leaf-cushioned lawns. In only a day, the autumn leaves that had fallen on the ground had been raked and removed. The grass underneath and the

trees were now starkly bare. I stood still for a moment, not yet fully through the gate, and realized with a jolt that fall was nearly over.

My uneasiness began then. The initial thought, not even true, stayed with me: “I have been away for some time.” It kept me from my work, drew me outside for the first of what would become a habitual stroll where, under the comfortable seclusion of evening, I could indulge in daydreaming.

I imagined leaving for Mexico City as I left my room on Old Campus still as the church bells tolled. During the change of seasons, there comes a gloom from the canopy of trees as they let through the day’s last blue light. Walking during the blue hour, I confused the temperate change of seasons—the sudden chill, the early darkness—with the dawning of evening in Mexico’s tropics. Soon, I began to anticipate even the rain. I imagined it falling as it did during the rainy months in Mexico City, from late afternoon to early evening.

Do you see what I’m trying to show you?

Those were the whimsical evening hours when I walked feeling a yearning akin to homesick ness for a place I had only been once before. I looked to the future, thought of it incessantly in a form of daydreaming, and confused it for having bearing on the present.

In New England, it is impossible to escape the seasons. One is, I am, in constant anticipation for what is to come. When I imagined Mexico City, however, I saw it fixed always during the rainy summer months. By escaping the change of the seasons, I imagined that I could hold

off the passage of time. But even the tropical months each took a characteristic of their own. January and February, when I had yet to adapt to the new city, were demure. March, with the promise and deception of spring, is the month of irony. April marked, finally, the beginning of the rainy season.

I walked incessantly in Mexico City, enjoying most of all the time just after sunrise and sunset. When the rain came in April, however, I was pulled away at whatever hour to go outside. I felt the rainy hours like a bloodletting. They brought on a weakness of perspective, and I found it difficult, even unpleasant, to imagine the future during them. The rain often fell so thickly that it was impossible to see more than a few feet in front. The city

ro’s work as a classic. “It is assumed that the classics will never die, but more than once they have been forgotten for long periods, stuck in crumbling catalogs or exhausted editions, without anyone to reprint them,” wrote David Marcial Pérez for the Spanish newspaper “El País.” Of the most significant reprintings taken on by publishers in the past year, Perez cites Garro’s Los recuerdos del porvenir.

The novel was originally published in 1963 by the editorial Joaquín Mortiz which was known for publishing the works of exiled republicans—Garro lived in exile for 23 years. In 1985, the publishing rights were absorbed by Grupo Planeta, another publishing company. The most recent edition was published by Alfaguara, better known as Penguin Random House, which plans to extend the sale of the novel to Chile, Columbia, and Spain. The previous year, Random House had published Garro’s complete works. The move by

the editorial is part of a larger literary trend to solidify Garro’s place as a pioneer of magical realism, a genre better known through the works of her male contemporary Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and her place as one of Mexico’s greatest writers.

The movement to give female writers their proper due is not new. Judith Thurman, who translated poems by the Mexican poet Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, writes about the effect on her own career as a translator: “The feminist Second Wave was cresting when I immersed myself in the life of Sor Juana. We of that generation were looking for heroines — exceptional women who history hadn’t paid their due.”

Are we, of this generation, still looking for our literary heroines, as Thurman was? If so, Garro would cut quite the figure. Stylish and captivating in her personal life, her biography is as interesting as her literature. She is, in the tra-

ditional way, a scorned woman. Infamous for dying in misery in the house where she lived with more than a dozen cats. Infamous for her turbulent relationship with her ex-husband. Infamous for the conspiracies she engaged in later in her life. And yet, never quite famous for her writing.

If we go back in time and try to make a heroine of this figure, what part of her story would we tell? Would we take her own words as fact or emend her writings to fit the feminist movement that came after her? When we try to make heroes of authors, we run the risk of moralizing their stories, unfairly editing the reality of their life. And yet, I’m still tempted to edit Garro’s biography to suit my conception of what it is to be one of the most prominent female writers.

I refuse especially to take Garro at her word when speaks about her ex-husband, the renowned literary and intellectual figure Octavio Paz. Garro says that she “lived against him, studied against him…wrote against him. [...] In conclusion, everything, everything, everything that I am is against him…in life, you don’t have more than one enemy, and that is enough. My enemy is Paz.”

I don’t believe that Garro was being truthful when she said that her enemy, her only enemy, is Paz. It seems unlikely that she would allow herself to be dominated in such a significant way and still write successfully. But I don’t doubt that Garro has a single enemy that she lives against. I think that her enemy is time. Unlike Herrick’s poems that seem subtly feminine in the way they associate the passage of time with physical decay, Garro describes time

as being primarily enriching. Often, she seems even overwhelmed by how the present is layered with the past and the future.

The question of legacy, especially of how to reinterpret a legacy, seems well suited to Garro, an author who seemed constantly stuck in between times. We return to her words. “Here we sit on this stone,” we may say, trying to place ourselves within time. If we are pressed to say more, to describe our own reality, the temptation to go back to the past resurfaces. The phrase is then modified. We pause. We attempt to answer the question again, and we reach our hand down to the rocky surface and find that its substance is not so straightforward to describe. “Here we sit on this stone,” we may try to repeat, and again, we struggle to continue.

I sit in the Trumbull Library, looking out to the courtyard where fall begins to slip away from the single colorful tree that still stands. I hold Garro’s book. She is pictured on the cover somewhere in her youth, with a timid smile. Like Garro, I try to situate myself in time by beginning: “Here I sit in what looks like fall.” Pressed to continue, I hesitate. “Here I sit in what looks like fall but only my memory knows what it holds. I see what’s outside and I remember the coming of winter, as season flows into season. Melancholically, I come to find myself in its image, transfigured in a multitude of times.” The daffodils bloomed in their vase by the window, withered, and were thrown out. As summer went, so will the fall, then the winter and the spring.

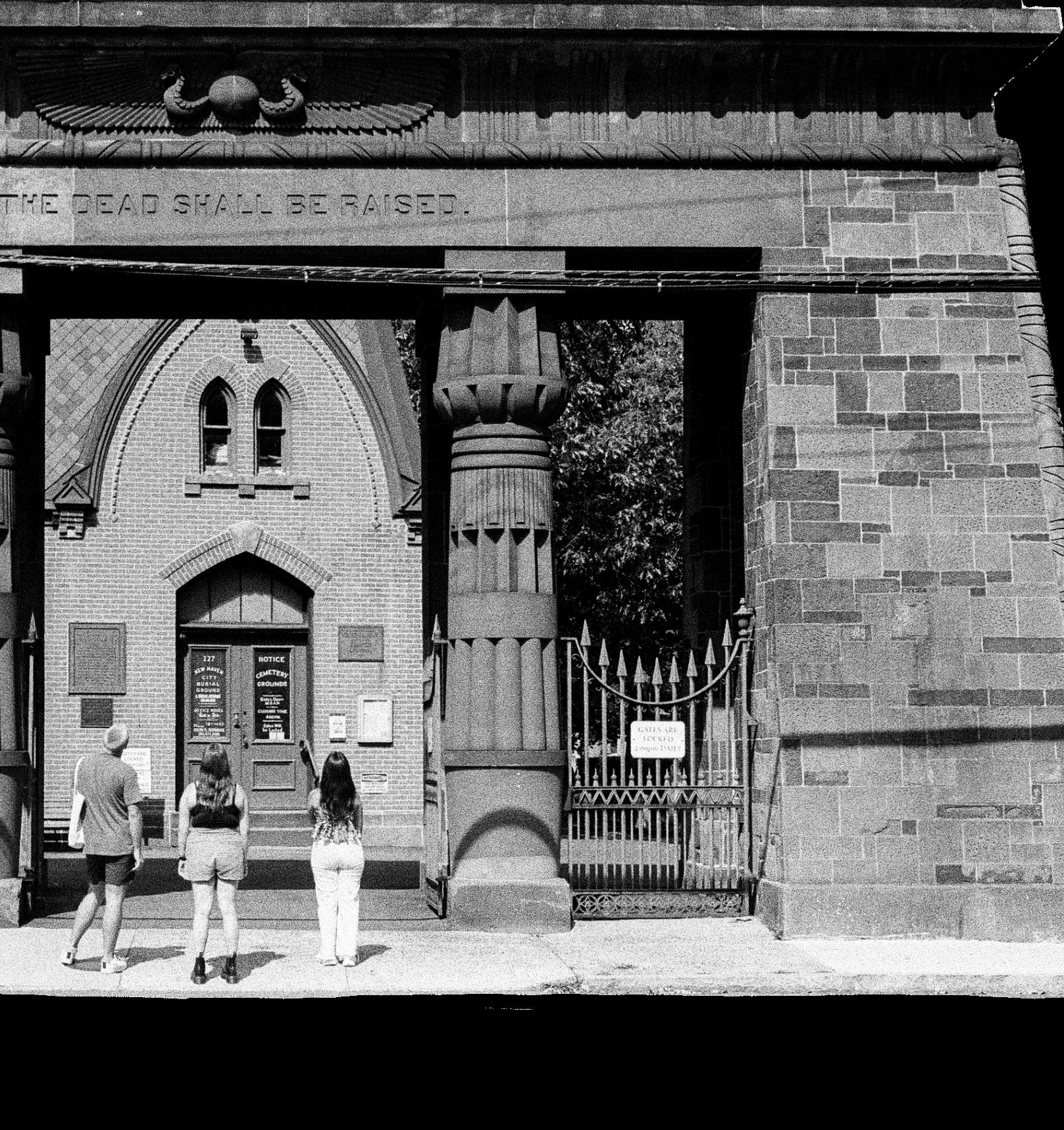

Olivia Wedemeyer

Photos by: Gavin Guerrette & Yale Daily News Archives

Olivia Wedemeyer

Photos by: Gavin Guerrette & Yale Daily News Archives

Yale is a small city. Its stone buildings tower high above the rest of surrounding Downtown New Haven. The throngs of students walking between classes are its citizens.

There’s another city not far away. Many of its stone towers have the same names as Yale’s: Phelps, Morse, Woolsey, Whitney, Bingham, Trumbull. Wide avenues named after hardwood trees— Cedar, Maple, Magnolia, Cypress— connect to side streets for pedestrian traffic. It can be challenging to find a place to live in this city; the lots for sale are easier to purchase if you already know someone living nearby. Living here, though, is worth the cost. The city is beautifully and carefully planned and prides itself on greenery, celebrity, and a sense of community. It is a fine place in which respectable people might happily find themselves. The dynasties reach their ends as you near the cold sandstone city limits and the fringes are sparsely filled by those without connection. Once someone moves here, they never leave. Who would want to, in a seemingly perfect town such as this?

This city is the Grove Street Cemetery. “The Dead Shall Be Raised” is its rallying cry. This Corinthians verse clashes with the Egyptian-inspired Pharaonic gate that opens into this world. The brick office behind the gate offers several pamphlets for visitors. There is one for bench markers, another for an arboretum tour outlining the 40 species of intentionally planted Northeastern trees, a glossed trifold with Civil War soldiers, and, finally, a solemn inquiry form for new burials. They all smell like cigarettes.

space for 144,000 bodies, was succeeded by the organized and aestheticized New Haven Burial Ground (now Grove Street). Proponents of the movement believed that turning cemeteries into quasi-parks would allow more people to enjoy these occupied spaces and emphasize their gravity as resting places.

Seasonal displays seen from the walk up Prospect Street initially lure many students to the cemetery. Magnolias, cherries, and dogwood trees create pink canopies in the spring, and yellow ginkgo and maple chase each other through the aptly named avenues in autumn.

James Hillhouse of Hillhouse Avenue fame (and early American politician-real-estate-developer extraordinaire in New Haven) first planted poplars throughout the cemetery at the time of its founding as part of the mid-nineteenth century “rural” cemetery movement. Burial went from being utilitarian and efficient to a more beautiful process that emphasized individuality through the planning of a cemetery. The utilitarian New Haven Green, which held

Motifs throughout the 18 acres speak to historical representations of the transition between life and death. A metal moth sculpture sits atop the visitor center, a reminder of the cyclical nature of life and metamorphosis—the change from one state to another. There is no cemetery without life in the first place. Sphinx statues stare at an awkwardly placed street sign on the side of the cemetery that runs along Lock Street, depicting the boundary between man and animal. Old headstones once carved with skulls representing the gruesomeness of death lean against identical headstones carved with angels to show the sanctity of life. The strongest contradiction here, though, is that between Yale and Grove Street. Where does one end and the other begin?

Grove Street Cemetery was founded in 1796, 93 years after Yale. At the time of its construction, the school went as far north as Elm Street.

The institution continued to expand upwards as opposed to further into urban New Haven. ‘Science Hill’ was first used in its current iteration in the twenties. Ezra Stiles and Morse College were constructed to its left in the sixties. Yale completed its total envelopment of the cemetery in 2017 with the opening of the newest residential colleges at the corner of Canal and Prospect. An angel statue watches over a bench headstone engraved with “in a field of memories we meet every day.” For years the angel held a candle. Now she holds a rolled-up copy of the Yale Daily News.

Students, too, are a reminder of Yale’s presence at Grove Street. Molly Hill ’25, a sophomore in Yale College, finds solace in the trees. An avid birder, she has been going to the cemetery about twice a month since starting college last year. She typically sees common grackles and robins, though she likes the bluejays best. She has frequented Grove Street enough to notice the White-throated sparrows that seldom appear, and only in the winter. “I see more birds if I go to further places like East Rock or Lighthouse Point… but probably the biggest difference is that the cemetery is a cemetery, so even if I’m birding, you can't help but think a little bit about death while you’re there,” Hill says, softening her voice at the word “death.” She first went to the cemetery to take a picture of the grave of Josiah Willard Gibbs, a decorated Yale professor and pivotal theorist of thermodynamics who developed “Gibbs Free

Energy.” She reflected on the celebrated scientist and sent the picture to her father, a chemistry professor, and started to explore the grounds. For Hill, Grove Street is an escape from the hectic hustle of school. “Sometimes I go by myself pretty strictly to bird, sometimes I go to write poetry, or write kind of anything vaguely. Something about it is pretty peaceful.” She shares that cemeteries are well known spots within the birding community, as they are often the only serene places in chaotic urban environments such as Yale and New Haven. Life floods and populates this graveyard. Those who take special note are privy to it.

No matter a student’s academic focus, the cemetery is surely home to a Yale notable in their field of interest. Hill first went to the cemetery to visit Gibbs. At his grave, students and passersby leave rocks and pennies as visitation gifts in line with Gibbs’s Jewish faith. Many offerings come from those wishing to do well on their exams, praying to the “chemistry gods” to look favorably upon them. History and English students may visit the cemetery to see Lyman Beecher, father of Harriet Beecher Stowe. For those interested in science and medicine, the school’s fraught history with the cemetery is enough motivation to visit. Yale’s Medical School was initially built where Sheffield-Sterling-Strathcona Hall is— just an intersection away from the cemetery. John Warner, Chair of the History of Medicine, mentioned Yale Medical School’s resurrectionist history to his Western Medicine class earlier this fall. In 1824, the body of 19-year-old Bathsheva Smith went missing from her grave at the West Haven Cemetery. Suspicions turned to the medical school, especially with Grove Street Cemetery so near. It made sense that medical students needed a way to obtain cadavers for anatomical practice. In the 19th century, resurrection— otherwise

known as grave robbing— became a trend at medical schools, and Smith’s body was found buried in a small mound at the corner of Prospect, on the medical school grounds. Riots broke out over the academic desecration of resting corpses. “The mob on the Green threatened to storm the medical school,” Warner elaborated. “[Connecticut] Governor Oliver Wolcott Jr. called the Connecticut Militia to read the Riot Act, or else the militia would charge, and the crowd dissipated.”

A new law was then passed in the State Assembly, “An Act to Prevent the Disinterment of Deceased Bodies.” Rumors spread of tunnels connecting the Medical School to Grove Street. Professional grave-robbing died down with the new act, but suspicions of Yale’s use of the cemetery remained. When asked to expand upon the relationship between Grove Street and the medical school, Warner noted an old practice of students meeting at the grave of Nathan Smith —the founder of the medical school—once a year at midnight. He paused before he spoke again: “What happened at Smith’s grave, I have no idea.”

“The walk along Prospect Street— that’s the most peaceful part of my day” sophomore Chela Simon-Trench said. “It's what separates me at home versus me at school.” Chela loves Grove Street. She has a favorite tree and a favorite bench, but she has been promised that their locations shall not be revealed here. When she was first assigned to live in Benjamin Franklin College as an incoming student, she was intrigued and somewhat concerned by the fact that a cemetery would be the thing separating her from the rest of campus, but she has now found solace in it. On walks home when the gate is open, she dances through the graveyard.

One thing she notes is that “[Grove Street] does not feel like Yale.” “Did you know it's designed to look like a city?” she asks, information she unearthed while researching for an Art History class. Maybe it can simultaneously be a city on its own, and a piece of New Haven, without being solely a small town in the province of Yale.

Cedar Street, an avenue running vertically within the cemetery, was once referred to as “the Street of Dignitaries’, housing the remains of many of the school’s celebrity figures and their families. In the likeness of a city, this is the “nice neighborhood.” Families share unified plots, and their gravestones are grandiose. Cedar houses the corpses of multiple former presidents of the University, including Jedediah Morse, Eli Whitney, and Benjamin Silliman— names that Yale-affiliates would recognize. These individuals are synonymous with the school’s ornate buildings and prestigious programs. In Grove Street, the people of Yale may even see something to aspire to. Walking through the small, planned city is a museum-like display of Yale’s cultivated historical identity. Yale’s elitism is preserved in the center, surrounded on all sides by the bones of residents whom history has forgotten.

A spot at Grove Street comes with a cost and requires connections. The cost of a full grave today is $7,500 ($9,500 including the burial fee). These now-available plots are mostly on the outskirts of the cemetery, far from Cedar. To be placed with the “dignitaries” there would have to be open space, and much more importantly, relation. Like Yale, the cemetery is big on family. A shared last name is a gateway to many opportunities, and a beautiful burial site is one of them. Still,

name can only go so far. Grove Street maintains that anybody can be buried there. The cemetery is always expanding, and more names continue to be added around its open edges.

The cemetery will never be fully congruous with Yale. It is surrounded by the University, and its sandstone walls can feel like an imperious break in the bastion of learning and community many envision Yale to be. Let us return to the 2008 proposal of Pauli Murray and Benjamin Franklin, termed the ‘New Colleges:’ perfect examples of how the school can both use Grove Street Cemetery to house its identity and ignore it when necessary. This is a case where the cemetery is not Yale and rather an entity obstructing Yale’s physical identity. At the 1997 bicentennial celebration of the graveyard, the University’s then president, Richard Levin, jokingly countered “The Dead Shall be Raised” with “[it] certainly shall if Yale ever needs the property.” He was still the leader of the school when architect Robert Stern proposed the plans for the New Colleges. Even though the proposal observed the divine nature of the graveyard, the team leading the project wanted to tear down the sandstone walls, replace them with iron gates, and open up the back of the cemetery to create a path through. This was met with protest from the city’s Urban Design League, Historical Society, Preservation Trust, and citizens. Significant not only because of those resting there, but

also as the first planned cemetery in the United States, Grove Street needed to be preserved. Yale does not have a claim over these lives, and what is best for the institution isn’t always what is best for the city. The proposal was eventually dropped. The new colleges were built without a pathway, and Prospect Street remains the only path to the new colleges.