58 /// Winter

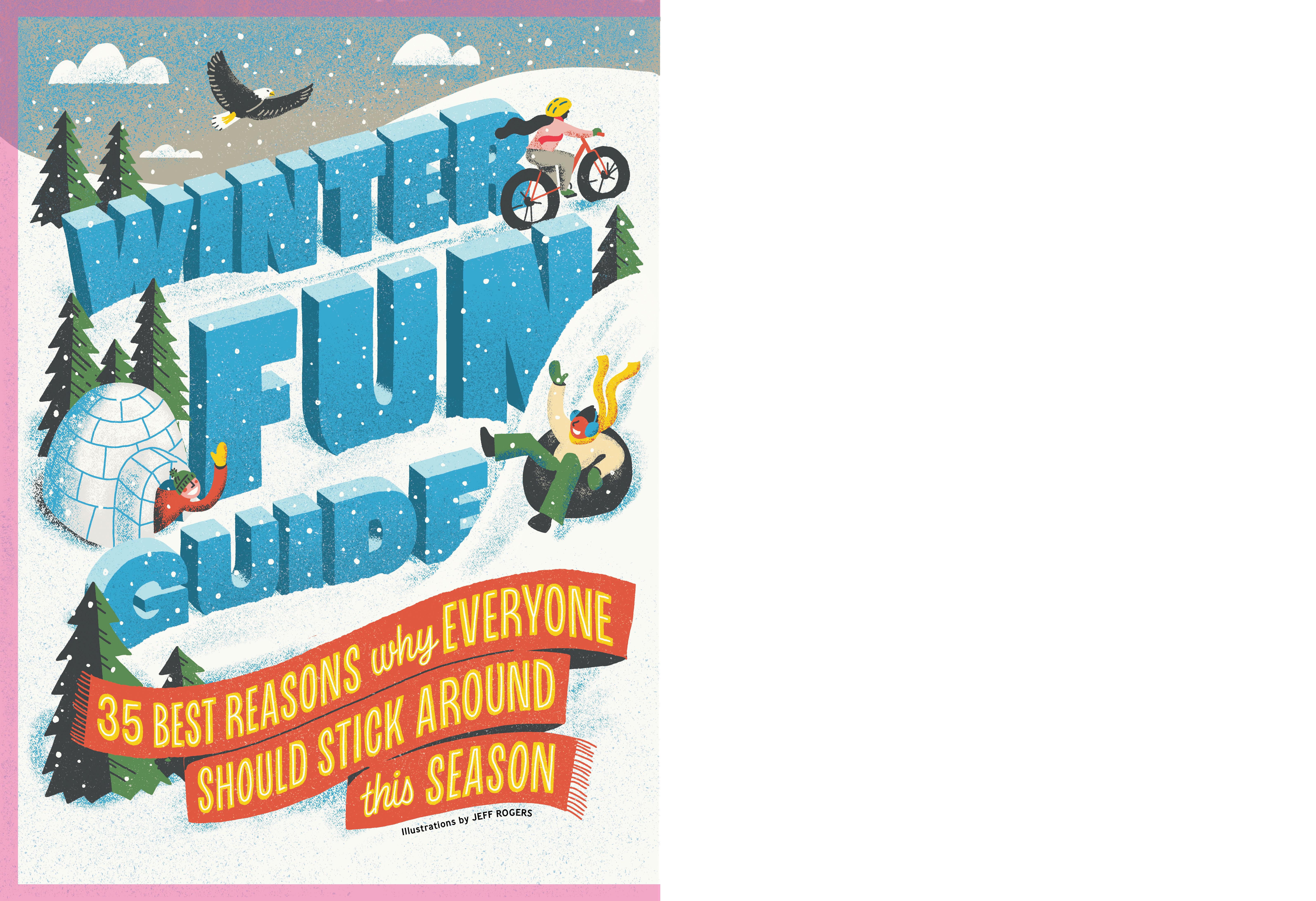

From outdoor adventures to indoor delights, we’ve got the 35 best reasons to stick around New England this season.

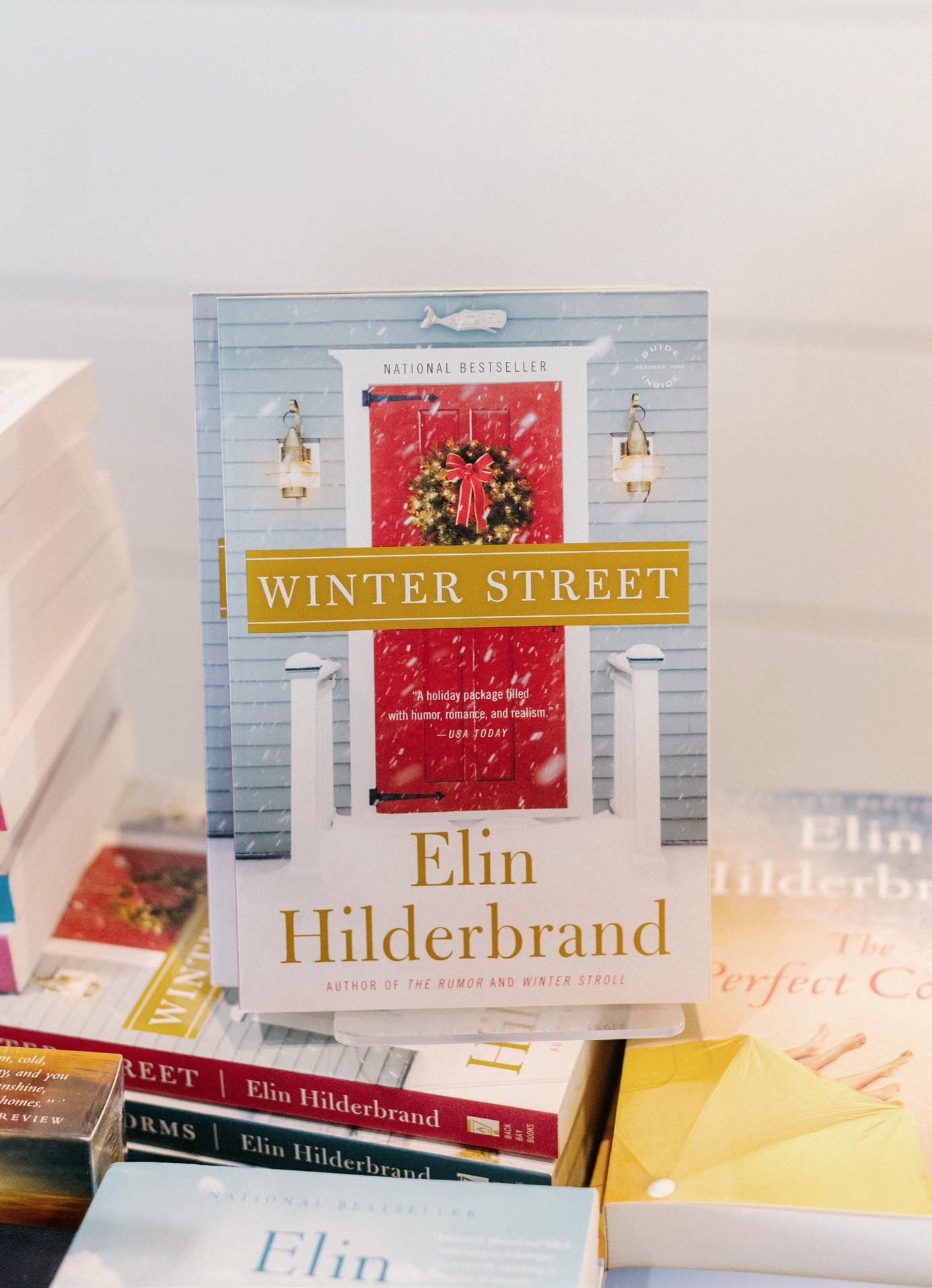

Elin Hilderbrand’s hold on her avid readers comes to life on a Nantucket January weekend. By Meg Lukens Noonan

Skaters take a harborside twirl against a pictureperfect backdrop at Rhode Island’s Newport Harbor Island Resort. “Winter Fun Guide,” p. 58

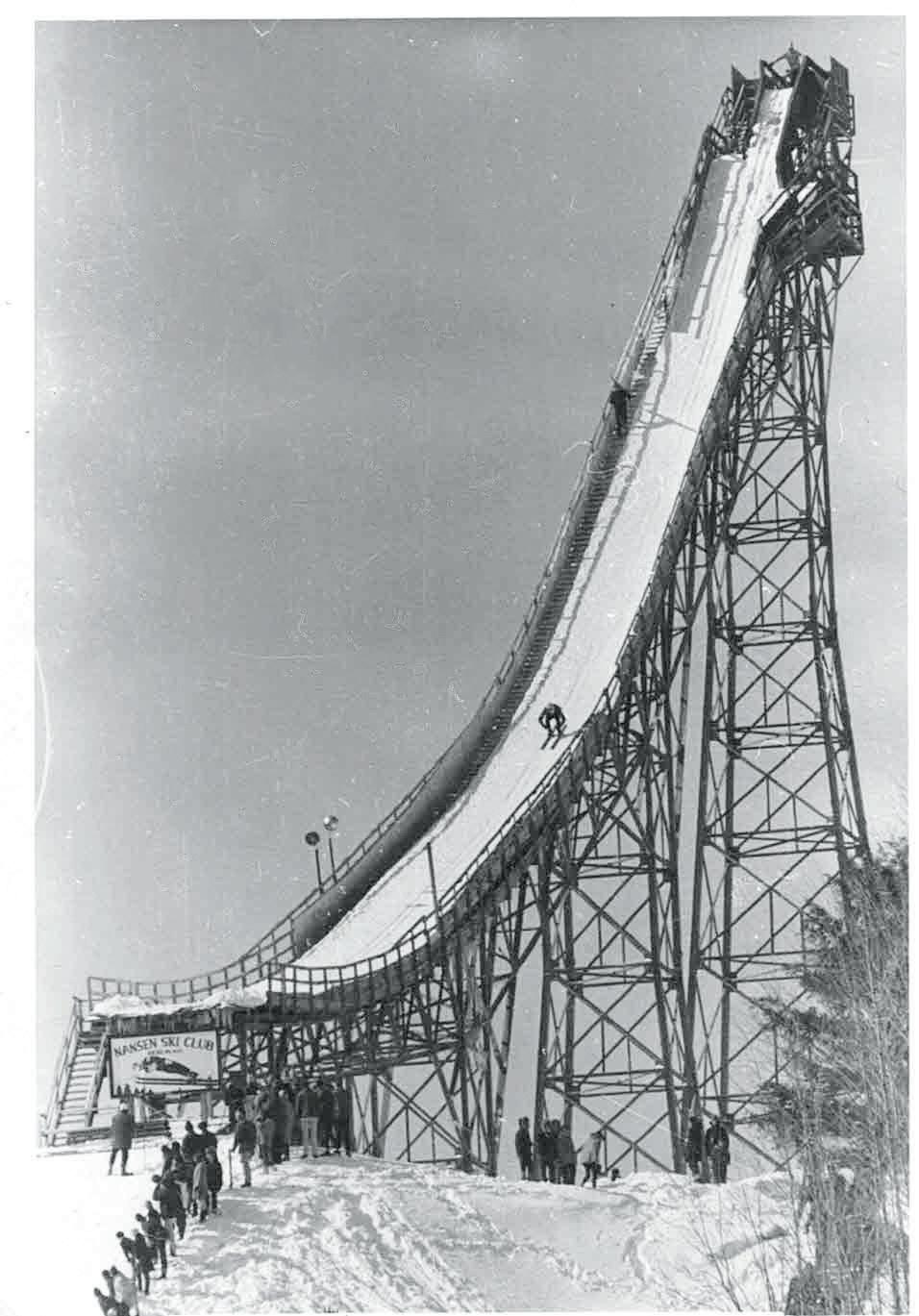

How a ski jump that was once the pride of the North Country may rise up once again. By Bill Donahue 94 /// The Storm

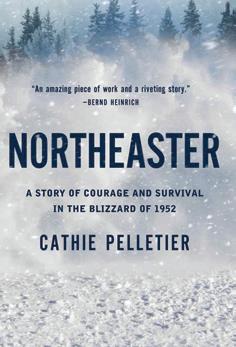

Cathie Pelletier’s new book, Northeaster, puts a spotlight on ordinary people caught in extraordinary circumstances.

With skill, patience, and a bit of luck, Roger Irwin captures nature photos that reveal a world of wonder.

Hitting the trails at the Jackson (New Hampshire) Ski Touring Center. Photo by Cait Bourgault

Yankee (ISSN 0044-0191). Bimonthly, Vol. 87 No. 1. Publication Office, Dublin, NH 03444-0520. Periodicals postage paid at Dublin, NH, and additional offices. Copyright 2022 by Yankee Publishing Incorporated; all rights reserved. Postmaster: Send address changes to Yankee, P.O. Box 37128, Boone, IA 50037-0128.

ON THE COVER Publishing Incorporated; all rights reserved. Postmaster: Send address changes to Yankee

Discover how a southern Vermont saltbox from the 1980s was rebuilt as a timeless mountain ski home. By Lisa Gosselin Lynn

On the South Shore of Massachusetts, Danielle Driscoll’s creative reinvention has become a family affair. By Annie Graves

In midcoast Maine, melty cheese known as raclette is at the heart of a simple, cozy meal. By Amy Traverso

40

With the Super Bowl right around the corner, we’ve got two crowd-pleasing appetizers to warm up the home team.

By Amy Traverso

With camera in hand, our Canadian correspondent shares how to enjoy his beautiful hometown, Québec City, in winter. Story and photos by Renaud Philippe

54

Under-the-radar ski mountains offer a bit of elbow room for your next downhill run. Compiled by Katherine Keenan

56

Fireplace fans, look no further: Warmed by flickering hearths of all shapes and sizes, these New England inns and restaurants excel at offering the cozy side of winter. Compiled by Bill Scheller

Contemplating the two faces of winter—a season that rewards our loyalty even as it tests our resilience.

By Mel Allen

Joe Bills

Ben Hewitt

moved to Maine during a January snowstorm over half a century ago.

I had known only mid-Atlantic winters, and soon I discovered a different season altogether, snow drifting past windows, cold plunging to 20 below. I learned what happens to an old car’s engine when antifreeze runs low. But I also came to appreciate the comforting sound of plows during the night, the warmth from a woodstove, the rush of clicking into Nordic skis and taking off into a forest. My young career as a freelance writer was made possible by Mainers who headed to warmer climes and needed someone to keep their home safe. One winter I lived by the sea near Biddeford Pool, another time in Portland, another in Yarmouth. I did my part and was sheltered for free.

I understand why some people leave before December’s first flurries, not to return until buds blossom on the trees. But as our “Winter Fun Guide” [p. 58] shows, there is a special satisfaction here when you dress in layers and embrace all that awaits, along with the special quality of light and beauty that belongs to no other season quite like this. Photographer Renaud Philippe makes the case that few places celebrate colder months like his home of Quebec City [“Weekend Away,” p. 44]. And “The Queen of Summer … in Winter” [p. 72] shows that even Elin Hilderbrand, whose novels set in beach-season Nantucket have

become best-sellers, finds deep pleasure in the inward turn that winter leads us to.

New Englanders also understand that winter tests our resilience, too. The news this autumn has been filled with storms: first Hurricane Fiona and then, of course, Hurricane Ian. We read about homes swept away, and lives lost. Rarely, though, do we get to know the people who made it through and those who did not. Using her novelist’s eye for detail, Maine writer Cathie Pelletier re-creates what happened to those whose world was forever changed by another storm, one that buried northern New England in the winter of 1952. Her new book, Northeaster, brings us into the lives of ordinary Mainers, and of one family on the New Hampshire coast, who found themselves needing to call on every ounce of courage and endurance—and even pure luck—to make it through. And she lets us see the hard, intimate moments when that is not enough. Though that blizzard happened 70 years ago, our adapted excerpt [“The Storm,” p. 94] shows how connected and vulnerable we all are when nature unleashes such force. A force that connects us past and present, now and far into the future.

Mel Allen

Though she had read some of Nantucket author Elin Hilderbrand’s books (“on the beach, of course!”), Noonan didn’t know much about her before reporting “The Queen of Summer … in Winter” [p. 72]. “In spending time with her, I learned that while she is, in many ways, living the kind of fabulous sun-kissed life she writes about, she’s also a highly disciplined writer who takes her craft and her fans—and her impending retirement—very seriously.”

“The Storm” [p. 94] is an excerpt of Pelletier’s latest book, Northeaster—whose title may give some readers pause. But the acclaimed author, who hails from northern Maine, believes the use of “nor’easter” is about as authentically Maine as the accents in Murder, She Wrote. And as Pelletier notes in her book, “The Oxford English Dictionary gives the term nor’easter an origin as early as the 1500s, long before any New Englander read a weather report.”

As an independent documentary photographer, Philippe has traveled everywhere from Haiti to Nepal, but he relished the chance to turn his lens on his hometown, Québec City [“Weekend Away,” p. 44]. “This is a city that, for my work, I often leave and find again, that I rediscover year after year, season after season,” he says. “We don’t reinvent classic places like this, but instead find new ways to look at them.”

This Brooklyn-based illustrator and graphic designer from Buenos Aires, Argentina, provides the endearing artwork for editor Mel Allen’s essay about teaching in rural Maine [“The Boy Who Walked on the Moon,” p. 10]. “I related to the feeling of having a teacher/safe haven who created space for a child to dream,” Mello says. “I think I am where I am, and what I am, in large part because of a teacher like that.”

“I like to say that my life was built one cookie at a time,” says Gallant, who grew up running around her mother’s bakery in Newburyport, Massachusetts. That early love of food pointed the way to her eventual career as a Bostonbased food photographer who works for the likes of Food & Wine, Condé Nast Traveler, America’s Test Kitchen, and, of course, Yankee, for which she created the stunning photos in this issue’s food feature, “A Winter Feast” [p. 34].

A graphic designer and illustrator whose work has appeared in Esquire, The New York Times, and Wired, among others, Rogers lives in Texas but had no problem channeling the feeling of our “Winter Fun Guide” [p. 58]. The assignment came right on the heels of working on a big holiday campaign for another client, “so my head was already very much in the snow! Which is ironic, since we just came off one of the hottest summers on record!”

Thank you for the powerful interview with JerriAnne Boggis [“Conversations,” November/December]. It challenges us all to step back and try to understand the feelings of those who may feel different from a perceived majority in any community.

All skin colors matter; all emotional, mental, and social feelings matter. All people have unique strengths which need to be identified and valued. Yes, attitudes about the human condition have been strongly influenced by the media, politics, money, and more. But those things don’t have to stop us from personally reaching out in our own communities to people who are not just like us and who are hurting because of feelings of exclusion.

JerriAnne Boggis sees herself as “a warrior, not a victim.” What a great mentor. Americans, listen up.

Susan Conroy Jacksonville, Florida

Susan Conroy Jacksonville, Florida

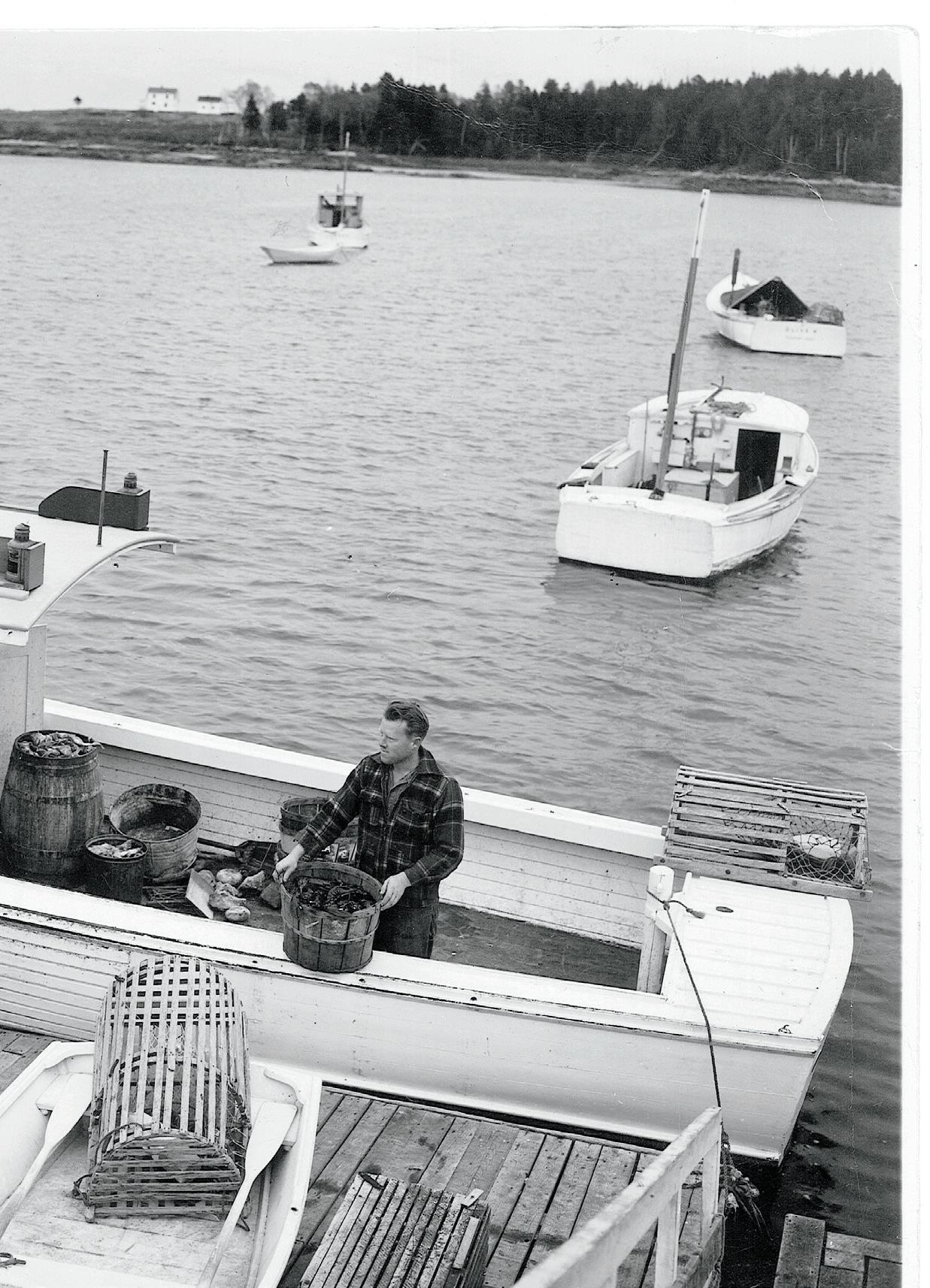

The young men and women in Erin Rhoda’s article “Lessons of the Field” [September/October] will cherish the memories and work ethic ingrained by the Aroostook County potato harvests. In most parts of America, people

do not even know where their food comes from, let alone anything about the people who harvest it with care and commitment. These young people will know the where, when, why, and how—and will be able to translate that experience into whatever life they build for themselves in Maine or elsewhere. Bravo to them for carrying on the great American tradition of hard work and dedication! I would advise them to keep it up, because the country needs people with that kind of can-do ethos.

James Babashak via NewEngland.com

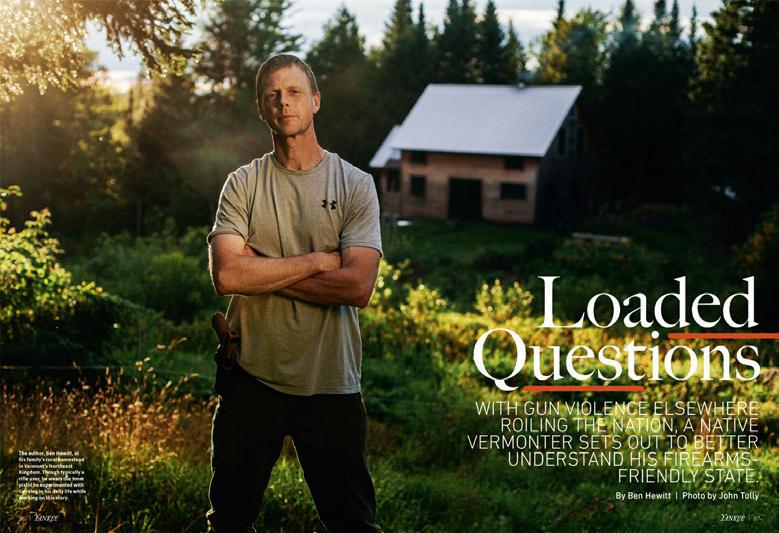

Ben Hewitt’s essay on gun ownership, “Loaded Questions” [November/ December], drew plenty of letters from Yankee readers with strong feelings on the subject. Here’s a sampling of what they shared:

Kudos to Yankee and author Ben Hewitt for a well-thought-out and relatively balanced article on guns. Journalism at its best tries to present both sides of any discussion, but it is rare to see today in any media. I envy Mr. Hewitt’s freedom in Vermont; as a resident of the state with the most oppressive—and ineffective—gun laws in the nation, I am frustrated daily with the hassle of trying to abide by them.

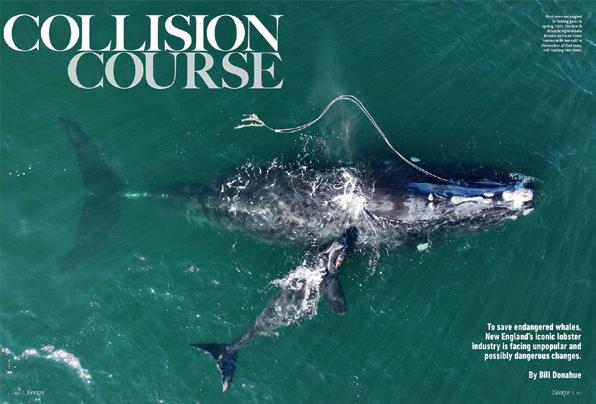

Bill Donahue’s article on North Atlantic right whales and the New England lobster industry [“Collision Course,” September/October] sparked a flurry of comments on Yankee ’s social media and website, with many feeling it showed Maine lobstermen in a poor light. One reader pointed out that there hasn’t been a single documented right whale death caused by Maine fishing gear in two decades, and suggested, “Don’t you think you should have said that?” Another reader, however, praised the article’s reporting as balanced, saying, “How is it that both sides of this ‘collision course’ come out seeming sympathetic?” Read for yourself, and weigh in at newengland.com/ rightwhales. —The editors

We want to hear from you! Write to us at editor@yankeepub.com. Please include your name and hometown, and note that letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Much as with alcohol during Prohibition, the anti-gun people hope that if they make guns illegal, gun violence will go away. But if you want to end “gun” violence, you have to focus on the causes and cures of the violence, not the tool.

John Willsie Jamestown, New YorkBen Hewitt’s thoughtful article was not only a timely read given today’s news headlines, but also a balanced examination of the issue of carrying handguns.

That said, Hewitt chooses to describe his experience of carrying as a “sinister” feeling. As a multidecade holder of a CCP (concealed carry permit) from two Eastern states, I have never felt “sinister,” but instead “prepared” to not become a helpless victim of crime. The difference between the two words speaks volumes.

Mike Van Winkle Sorrento, Maine

I always look forward to Ben Hewitt’s column when each new Yankee arrives, so I turned right away to “Loaded Questions” to see what his ever-reasonable approach to gun ownership would be. Well... off to a bad start when I see Ben’s “Make my day!” photo on p. 96, complete with holstered pistol and accompanying assertion that guns make him feel “powerful.” Come on, Ben! All we need to know is that Japan has one civilian-held firearm per every 330 citizens, and in 2021 that country experienced a total of one firearm death. It’s not complicated. Ban guns!

Ken PotterSan Diego, California Gun Owners of Vermont president Eric Davis says [in the article], “We don’t have a gun problem, we have a psychological problem.” Can he mean that countries with sane gun laws—where mass shootings are a rare occurrence—are less crazy than we are? It would seem so, as they have apparently determined how to keep guns out of the wrong hands.

And, if guns represent freedom to Americans, the question must be asked: Are those countries less free? If you mean less free to worship, watch a movie, shop, attend a concert, or go to school without fear of being shot, the answer is no.

David Crane Stockbridge, Massachusetts

ILLUSTRATION BY EUGENIA MELLO

ILLUSTRATION BY EUGENIA MELLO

was in my early 20s when I taught my first fourth-grade class in a small Maine town. My only experience was that once I had been 10 years old. I was hired because the district wanted a male teacher for a group that had frustrated their educators in earlier grades. I had just returned from the Peace Corps, and the thinking seemed to be that if I could survive the rigors of an equatorial mountain town, I could tame 27 country kids with attitudes.

I taught 80 children during my three years, and today they are pushing 60; no doubt a number have grandchildren, perhaps even some entering fourth grade. Occasionally I get the urge to see my former students again, because I knew them when they were young, and I wonder what happened after. And maybe, I want to know if they remember, too. Back then, want-

ing to help them succeed often kept me awake at night.

One winter day there was a knock on the classroom door. A woman stood there, and beside her was a boy. She said he was from another town and he had come here to live with a foster family. He was short, sandyhaired, unsmiling. He said his name was Faron. The other kids looked on in silence, aware there might now be a shift in the class dynamic.

I asked him to write his name on the blackboard. He didn’t move. I thought he was shy and said I’d walk with him to the board. He motioned to me. I leaned down, and he whispered, “I don’t know how.”

This was back when instruction was done in groups separated by ability, especially in reading. Faron and I became a group of two, and each day we sat together reading “books” I wrote

for him. They were no more than 10 handwritten pages, stapled together, and they came with bold titles in black Magic Marker. Faron flew with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on Apollo 11, and as Armstrong stepped onto the lunar surface, so, too, did Faron. He fought through cold and ice-choked waterways to plant a flag at the North Pole with Admiral Robert E. Peary. He stood with Edmund Hillary on top of Everest. He set sail from Plymouth, England, aboard the Mayflower. He was a scout with Lewis and Clark. He was the lone survivor at Little Big Horn. He found his way to this little Maine town where he was brave enough to tell me what he did not know.

I don’t know whether he learned to read that year or whether, as I suspected, he memorized the stories from all the times we read them, and the words flowed. Soon he was reading the tales of his exploits aloud to a larger group, and a few months later the school year ended, and Faron disappeared from my life.

Not long ago, I typed his name into Google. What I found was his grave marker and, beneath it, the year 2002. He had not yet reached 40. He had died on a street in Portland. Maybe he kept those stories for a while. Maybe not. Teachers rarely know if they change lives, but sometimes—if they are lucky—they can change a few months here and there, when even a little boy with so much stacked against him can be a hero, when he reads aloud about the night he walked on the moon.

When a child cannot read, what can a teacher do?

A small mountain in Maine delivers a big-time thrill.

BY IAN ALDRICH

BY IAN ALDRICH

For a brief, stomach-churning moment, I had a painful vision of my future: A crash? A voice asking if I was OK? I wasn’t totally sure. The only certainty was that as I sat in a borrowed sled atop the toboggan chute at the Camden Snow Bowl, I wanted to bail. It was a Friday afternoon in mid-February, the opening day of the weekend-long U.S. National Tobog gan Championships. In a matter of hours this area would be open to more daring sledders from around the country. Until then, however, anyone with the gumption to climb the hill to the starting platform could sample the glory. So long as they possessed more courage than I felt just then.

“Hold on,” I shouted to the chute master, Stuart Young, whose hands gripped a big lever.

“Maybe we shouldn’t do this.” Then I heard the voice of my 11-year-old son, Calvin, seated in front of me.

“Come on, Dad,” he implored. “Let’s go!”

I locked eyes with a smiling Young and meekly returned a grin. “Yeah, Dad,” Young said, releasing the gate, “let’s go.” And with that, the front of our sled dropped down onto the chute and we were off. My son screamed with delight.

So many others have shared his reaction. If there is a center point in the toboggan world, it is Camden, Maine. Here, at the foot of the Snow Bowl, a small town-owned ski moun tain, sits the Jack Williams Toboggan Chute. This 400-foot wooden run first opened to the public in 1936 and is still considered the

opposite : A two-man toboggan team hurtles down the 400-foot-long Jack Williams Toboggan Chute, a time-honored fixture at Maine’s Camden Snow Bowl.

above : “Golden Girls” (from left) Sarah Maxcy, Amanda Overlock, and Carrie Overlock head to the top of the chute at the 2022 U.S. National Toboggan Championships. Their team, Shear Madness of Warren, Maine, won the Fastest All-Female Team category and placed second in Best Costume.

longest of its kind in the country. To the uninitiated, its features are both simple and daunting: a steep drop and then a long, icy straightaway that spills out onto a frozen Hosmer Pond. It’s not unusual for sleds to top 40 mph by the time they hit the pond.

“Sometimes you get two trips in one,” says Young, a Camden native whose father helmed the rebuilding of the chute in the ’60s. “You have the chute run. And then when you get out on the lake, you have a whole other run.”

The fastest times are clocked at the U.S. National Toboggan Cham pionships, an annual February event started by the Snow Bowl in 1991 as

a fundraiser for the skiing operation. Despite the race’s grand title, the bar rier to actually becoming one of the 400 teams to compete is low: Your sled must be made of wood and you need to meet certain size and weight restric tions. Otherwise, no real experience is necessary. Pay the registration fee, and you’ll get a bib number.

Which is to say, this event both is and isn’t a race. Oh sure, it attracts obsessive types who’ve worked all year on their sleds, but coming as it does in the depths of winter, the weekend serves up a hearty stretch of light and noise when those things are in short supply. There’s tailgat ing on the pond. There’s live music. And there’s a costume parade. Maybe you’ll see a team clad in NASA blue onesies, or dressed as Golden Girls characters. It’s hard to miss the fid dle player who strolls the crowds or the man dressed as Sasquatch who clutches a beer in one hand and highfives new fans with the other. At these championships even the slowest

from lower left : Dressed in their best Snoopy

of racers receives applause.

“People that come here are often brought here by other people,” says Holly Anderson, the Snow Bowl’s assistant director and co-chair of the toboggan championships organizing committee. “They’re here as specta tors, but then they come back as rac ers.” She laughs. “It’s kind of an insidi ous thing that we’ve got going here. We make it so fun that they want to get on that chute and try it out.”

I got a taste of that as my sled hit the straightaway. It had been unseason ably warm, which meant the ice that Young and his team had been so dili gent in building up earlier that morn ing had softened. Our quick descent gave way to a petered-out finish that just barely brought my son and me to the pond. As we coasted by the timer’s station, the few onlookers still in atten dance clapped for us. And, like many a tobogganer before me, I felt certain thoughts begin to percolate. Maybe, just maybe, I started to believe, we’d race in this event one day ourselves.

You may not recognize Peter Kilham’s name, but you probably know his work. There’s a good chance at least one of his creations is in your yard right now.

In his 2018 biography The Perfectionist: Peter Kilham and the Birds, Kilham’s son Larry writes that his father had a passion for inventing. In 1960, after retiring as a design engineer, Kilham cofounded a quirky Rhode Island–based record company, Droll Yankees, which specialized in capturing the voices and tall tales of native New Englanders as well as the sounds of nature, such as birds in the woods near Kilham’s home.

Along the way, Kilham began reflecting on the bird feeder in his yard. A wooden log with drilled holes for holding suet, it was homely and messy, and birds didn’t seem to find it particularly interesting. So he began

brainstorming a model that would be attractive, easy to clean and fill, and able to entice a variety of birds by serving up seed instead of suet.

What he came up with was the birding world’s first tube feeder, a style widely used today. Topped with a rugged metal cap to discourage squirrels, it would come to be called the Classic A-6F. It was a hit with both birds and the National Audubon Society, which gave it an enthusiastic endorsement, and before long Droll Yankees was in the bird feeder business.

But Kilham wasn’t done inventing. In addition to designing multiple other feeder styles, he made an accessory that became the A-6F’s ideal companion. After threading an old vinyl record onto the feeder’s cord and seeing how it discouraged pillaging squirrels, Kilham refined his discovery into the now-omnipresent— and endlessly entertaining—squirrel baffle.

Droll Yankees has changed hands several times since Kilham’s death in 1992, and most recently it was acquired by Pennsylvania-based Woodstream. Yet the quality endures, with Droll Yankees still considered the crème de la crème by birds and birders alike. Squirrels, on the other hand, are far less enthusiastic. —Joe Bills

How a Rhode Island tinkerer built a better feeder.

Who says kids should have all the fun? At The Baldwin — an all-new Life Plan Community (CCRC) — we say this is your time. Make a splash in the pool. Dance, stretch, lift, and box in the fitness center. Learn for the love of it. Take to the nearby trails, then top off your day at the local brewery. Define life on your terms and do whatever you choose — whether that’s everything or nothing at all.

The Baldwin is approaching sold-out status with opening planned for fall 2023. Call 603.404.6080 or visit TheBaldwinNH.org today!

The Baldwin Welcome Center

1E Commons Drive, No. 24 | Londonderry, NH 03053 603.404.6080 | TheBaldwinNH.org

Scan to see the latest construction update video or go to TheBaldwinNH.org/ Construction_Update.

In the living room, a steel beam marks where the footprint of the Ehrlichs’ home was expanded to create a window-filled sunroom they call the “snow globe.” On winter evenings, a fire can always be found roaring behind doors crafted by Stoll Industries. The 100-year-old barnboard adds to the warm feel, as does the handmade leather chandelier, by South Africa’s Ngala Trading. right : Lisa and Randy with their kids, Ella and Daniel, and their dog, Nellie.

BY LISA GOSSELIN

BY LISA GOSSELIN

On winter afternoons when she is done snowboarding at Mount Snow, her two chil dren are snowmobiling behind the house, and her husband, Randy, is skinning up the hills for an extra workout, Lisa Ehrlich likes to curl up for a moment of quiet in the room she calls the “snow globe.”

Light streams into her Wilmington, Ver mont, ski home through the floor-to-ceiling windows. Off one end of the room, double doors open to a large, covered balcony that looks out over a stand of snow-laden pines.

Inside, deep armchairs are slung with fauxfur and nubbly wool throws. “I have a thing for throws,” Lisa admits with a laugh. Across the room, flames flicker in a fireplace set into

a wall of antique barnboard.

“When we first toured the place and I saw those barnboard walls—some planks are 16 inches or wider—and the fireplace and the hand-hewn beams, I knew we could do some thing with this,” she remembers.

“This” was a house that looked very differ ent from the one where the Ehrlichs now spend their winter weekends. It was an unremarkable 1980s clapboard saltbox set in a subdivision.

“The interior felt small and dark,” Lisa recalls. “But there was that barnboard. And you can’t really see any neighbors.”

The original owner had added barnboard paneling to the walls and rough-hewn beams to the ceiling. Those elements became the theme that Lisa, an interior designer who works with Trovare Home Design of Green wich, Connecticut, riffed upon.

Barnboard is etched with stories of the long

New England winters that build a timeless patina. It is a material that Rob Wadsworth of Vermont Barns and Wadsworth Design/ Build—a firm known for its use of reclaimed materials—works with often. Lisa reached out to the Bondville-based builder and together they completely reimagined the home, dou bling the space and adding on to three sides. “We wanted to keep the original footprint, but we needed more space,” Lisa says.

The “snow globe” sunroom was added off the main living room to bring light in. A garage and small mudroom were attached off the kitchen. The house sits on a hillside, so a lower-level “sports garage” (for the snowmobiles and skis, bikes, and dirt bikes) could be built off the back, accessed from a walkway that leads to the base ment playroom and small office.

far left : A view through the living room to the snow globe, where leather chairs custom-made by Lee Industries invite hanging out with family and friends.

center : Frost Bite by Colorado artist Leslie Le Coq overlooks the banquette that Lisa had custom-built to accommodate greater seating flexibility.

above : The Ehrlichs prefer home-cooked meals, so the compact kitchen gets plenty of use—and space-saving touches, like the pots and pans hung from a beam, are the soul of practicality.

above : The Ehrlichs’ home, nestled in snow. The floor-to-ceiling windows of the snow globe can be seen at far left.

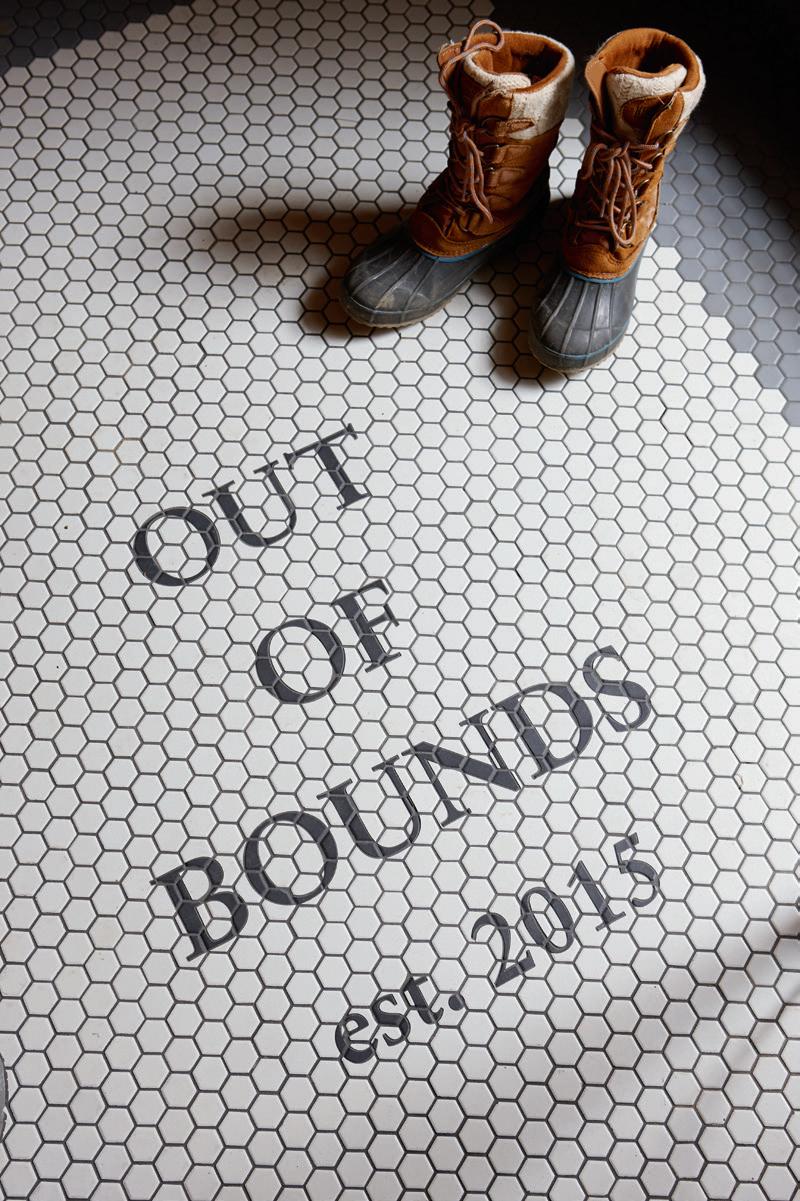

right : In the guest mudroom, which also serves as the main entrance, Lisa designed the penny tile floor to showcase the skiinginspired name of her family’s home, Out of Bounds, with lettering laser-cut by Vermontbased Village Tile.

far right : Another Leslie Le Coq photo, Below Zero, anchors this vignette of pieces carefully sourced to play up the mountainchic vibe. Lisa chose the leather-wrapped console to create a small bar area; two faux-fur stools are tucked underneath to be moved when the family is entertaining and additional seating is called for.

To visually tie the various additions together, Wadsworth clad the entire exterior in reclaimed wood. The effect is a mountain cabin that looks as if it could have weathered hundreds of winters.

Lisa went to work on the interior. She had trained with the acclaimed New York designer Bunny Williams, who’s been called the “doy

enne of livable luxury.” The influence shows in the mix of plush fabrics and textures used throughout. But Lisa tempered it with a color palette drawn from the granite, bark, and loam of the surrounding Vermont woods. “I literally picked up stones to determine some of the col ors,” Lisa says. “I wanted to bring that feeling of nature inside.”

Except for the addition of the “snow globe” room, the basic layout of the main part of the home stayed the same. Lisa gutted the kitchen and rebuilt it with new appliances, cabinets done in a warm gray, and subway tiles. For the dining nook off one side of the kitchen, she found a table and benches of reclaimed wood from West Elm and had a carpenter use the materials from one of the benches to extend the table to form a larger square shape. “We’ve had as many as 15 here for Thanksgiving,” she says.

The Ehrlichs love to entertain, and the poufs that are scattered around the living room are just the right height so that they can be pulled up to the table when guests arrive. “We also have the ‘party barn,’” says Lisa as she walks into the garage that connects to the kitchen. With an interior finished in cedar, it can be converted into an additional dining or dancing area.

The master suite sits off the main living room, hidden behind a door in the barnboard

above : In the master suite, acrylic consoles provide tabletop space without overwhelming the small space. The stylishly layered bedding includes Lisa’s favorite coverlet, a brown heathered wool blanket by Libeco.

top right : A view of the Jack-and-Jill bathroom, with its custom-made shower curtain.

bottom right : In a master bath designed to have the feel of a spa, the shower also functions as a steam room, while antler towel hooks provide a casual, rustic touch.

wall. Lisa kept the original narrow farmhouse stairs that lead up to two small bedrooms and a full bath.

“We’re lucky that our two children still share a bedroom,” says Lisa. That allowed her to make the second bedroom a guest bed room for sleepovers with friends. There, Lisa put three single beds with pine frames that she painted a matte black. The two rooms connect to a Jack-and-Jill bathroom.

“This is a weekend ski house and we wanted to have fun with it,” Lisa says. In that bath room, she designed a shower curtain with the black silhouette of a skier. The metal letters “S K I” hang on the wall of the kids’ bedroom next to a metal cabinet with mesh doors that serves as a bureau. The finishing touch Lisa

added was in the entryway, which has the name of the home, “Out of Bounds,” tiled in black on the white floor.

“We had wanted a ski house that was close to the slopes, but not right on them, so we call the house ‘Out of Bounds,’” says Lisa. “It’s also where we come on weekends to get away. Whenever we get up to Vermont, I feel like we leave our other lives behind. We don’t watch TV or spend much time on screens. We just unplug.”

BY ANNIE GRAVES

PHOTOS BY JOSEPH KELLER

BY ANNIE GRAVES

PHOTOS BY JOSEPH KELLER

As a little kid, she went rummaging through antiques stores with her mom, getting a taste for the treasure hunt and the potential lurking in old things. Later, grow ing up, she would help out at her parents’ restau rant in Woburn, Massachusetts, set in an aging mansion—further enhancing her aesthetic and an eye for possibilities. Flash-forward a few decades to married life in England, a career in film and television production, and a subsequent return to the U.S.

“Why are we living in London, so far from the ocean?” Danielle Driscoll remembers her husband, Luke, asking one day. They remedied

COURTESY OF DANIELLE DRISCOLL (PAINTING)that oversight in 2013, buying a century-old gray-shingled gambrel, rugged as a nut, just a few blocks up from Scituate Harbor, a small seaside town on Boston’s South Shore. In the movies, it’s called foreshadowing. In other words, there is every reason why the crisp Atlan tic would feature so prominently in Driscoll’s future artistic life.

This is where Driscoll, 45, polished a life style blog she calls “Finding Silver Pennies,” named for a vintage children’s book her mother had given her. “You must have a silver penny to get into Fairyland,” she reads to me, from the title page. It seems like code for entering

the world of imagination; the blog, she says, unlocked her creativity. While it initially focused on home life—more of a journal—it quickly changed direction a few months later, when she discovered the wonders of milk paint, and its transformative effects on kicked-tothe-curb furniture. Driscoll’s experiences with brushes and paints, and the skills she acquired and subsequently shared in her online DIY and home decor videos, would lead her to try her hand at watercolors.

Specifically, to capture the charms in and around Scituate Harbor, where she and her husband were rehabbing their home. In fact,

far left : Danielle Driscoll recalls painting “Breaking Wave” in spring 2020 partly as a way “to feel calm in a time that felt very uncertain.” The beach, she says, “is my happy place.”

center : Driscoll with her son John in the sunroom/ studio of their Scituate Harbor home. An artist in his own right, John prefers to use a tablet to create his illustrations, while his mother makes this reclaimed table the main workspace for her sketching and painting.

above , from top : A classic New England beach tote filled with a bouquet of hydrangeas is the star of one of Driscoll’s greeting cards, playfully captioned “Thanks a bunch!”; a collection of Driscoll’s art-making tools, ready to fill a blank page with her colorful ideas.

breeze, barely holding on. A sug gestion of seashells, a characterful whale, a fleeting lighthouse, a whiff of mojito caught in a saucy glass. The kind of airy seaside pick-me-up that some of us crave mid-January.

“I love painting the ocean,” she says, simply. “Water, shells, natu ral things. I struggle with structure, buildings, and straight lines.”

The same airy feeling echoes through Driscoll’s sun-washed studio that juts off the side of the main house. The floor is painted white, with a pale blue ceiling. Sketch pads and water colors are scattered over a round work table, and a jar of brushes sits handy; the water holder is a small French yogurt pot. Hydrangeas lounge in a

top : A sampling of Driscoll’s work, including some of her newest offerings, stickers. “I’m so glad they’ve made a comeback!” she says. above : Driscoll’s love of the ocean is echoed but expressed in an entirely different way in John’s Ink Harbour Illustrations designs.

dangling wall basket; beach stones sit on the windowsills, soaking up the sun. It’s like a painting spa.

“Watching the watery paint on the paper is mesmerizing,” says Driscoll. “Like a meditation.” She’ll use both wet and dry watercolor techniques to cre ate her ocean seascapes, lighthouses, seashells, sometimes adding swipes of acrylic after.

But the other inspiration for Driscoll resides not down the street, where masts bob in the harbor and seagulls hunker on salt-soaked piers— it’s right here, at home. “Family plays such a big role in my creativity,” she says. She collaborates in an online shop with her 16-year-old son, John, who is “super-artistic,” and prefers to draw on a tablet and paint with acrylics to cre ate his own beachy graphics under the moniker Ink Harbour Illustrations. Her younger son, Conor, 13, helps pack cards (although Driscoll oversees all shipments—her “type A personality,” she says). And Luke, a software engi neer who loves woodworking, just fin ished making a fleet of wooden stands to accompany the 2023 calendars.

We’re thumbing through a rack of greeting cards—a mix of hers and John’s—in the “packing” area, upstairs. Stacks of 2023 calendars have just arrived. Mother and son donate a por tion of every sale to the World Wild life Fund. On the horizon, Driscoll is planning a line of fabrics and wall paper. “I don’t know why at a certain point people are taught not to be cre ative,” she muses, as we’re looking at the note cards. “But that’s why I share the tutorials.”

And it occurs to me that quite possi bly the renaissance women of the pres ent day must have wide expertise in a range of skills. Where blogging leads to DIY, which leads to light-filled water colors, and then comes full circle, with tutorials where she passes along every thing she’s learned. “The first water color class I ever took, I wanted to cry,” says Driscoll. And she smiles. “Then I got better.” findingsilverpennies.com

Finding a home at Taylor means more than access to a stunning n

New England’s appeal as a retirement destination may not be as obvious compared with other parts of the country—but when you stop and consider all that this region has to o er, why would you retire anywhere else? e same natural beauty, rich history, and cultural vitality that make New England a favorite travel destination also make it a great place to retire.

Picturesque coastlines, pristine lakes, rugged mountains, world-famous fall foliage, small-town charm, big-city sophistication, and vibrant culture— these are just a few of the features of living in New England that make it

an increasingly popular choice for those looking to retire. And there are more practical considerations, too, including close proximity to Boston and New York, access to world-class healthcare, and the lowest crime rate in the country (all six New England states are among the 10 safest in the nation, according to a recent ranking by U.S. News & World Report).

For outdoor enthusiasts, New England’s geographic diversity is unparalleled. No matter where you decide to settle, you’ll be within an easy drive of year-round adventures at beaches, lakes, and mountains. New England’s 6,000-plus miles of

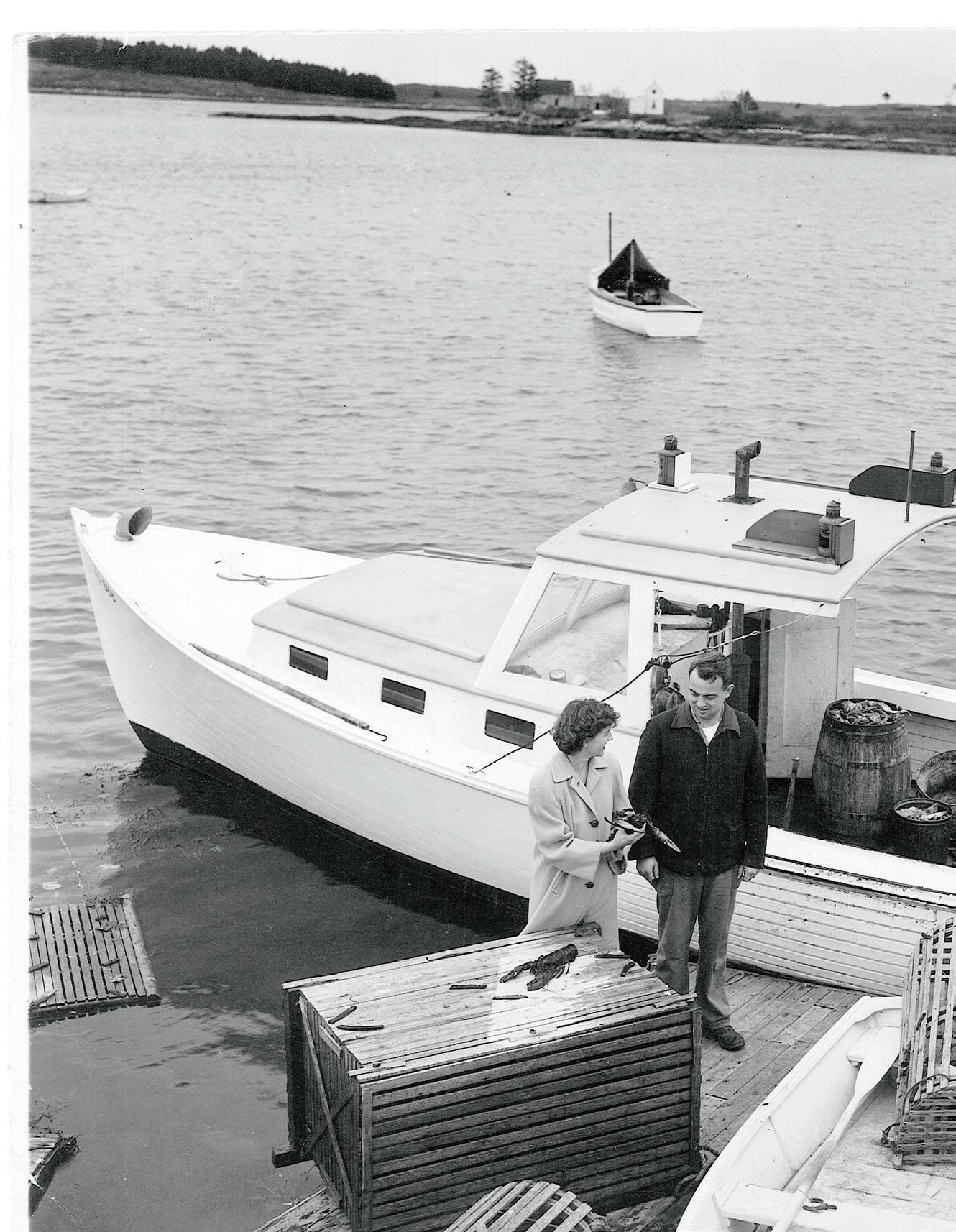

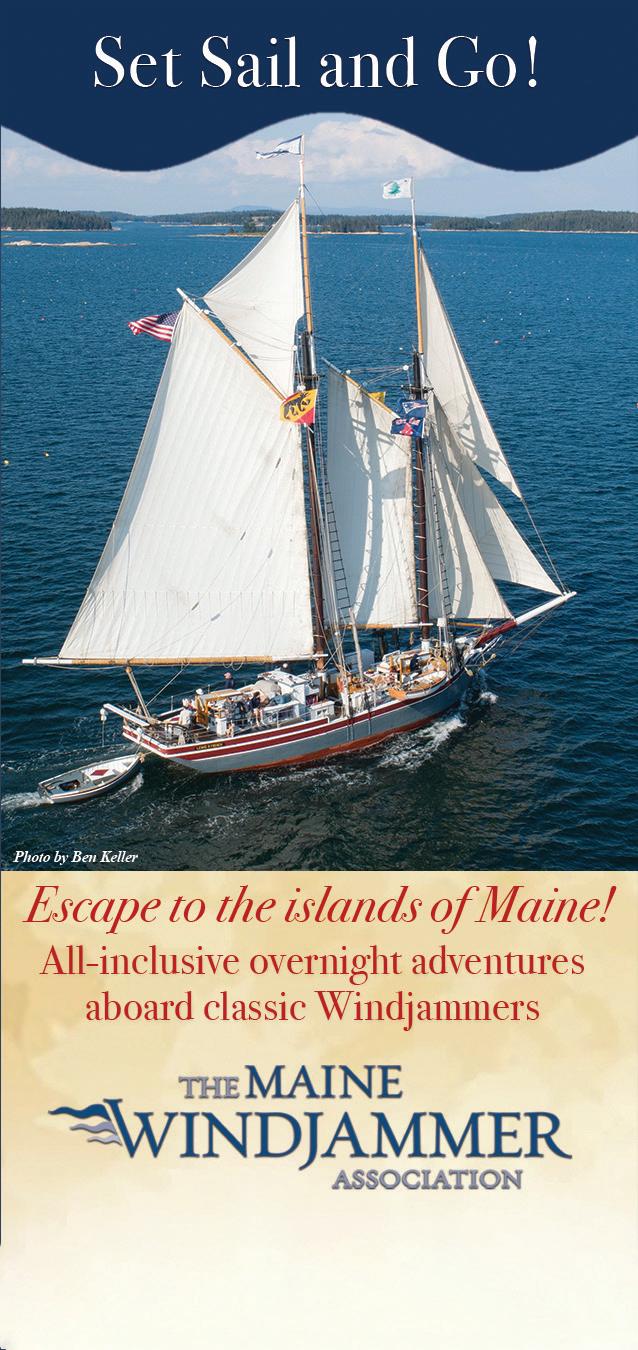

coastline invites endless exploration (and along the way you’ll enjoy some of the freshest seafood you’ve ever had). ese iconic waters are a sailor’s dream for “gunkholing”—nautical speak for meandering by boat—along the coast from Mount Desert Island to Cape Cod, Narragansett Bay, Block Island, and beyond. On land, hunt for shells and sea glass and look for wildlife during a walk along rocky tidal shores, or lounge under an umbrella on wide, sandy beaches. Even better, the New England coast is punctuated by nearly 200 lighthouses, with many of these historic beauties open to the public and all with a unique story to tell.

Venture inland, and you’ll discover rolling hills, crystal-clear lakes, and majestic mountains that provide a playground for hiking, swimming, shing, camping, and mountain biking. ere are rivers with tranquil

pools for shing and long, gentle stretches for kayaking and canoeing; plus, thrill seekers can nd all classes of rapids for whitewater ra ing. Summer in New England is a magical time to be outdoors—but so is fall, when recreation takes place against a backdrop of brilliant reds, yellows, and oranges. And when winter snow arrives, the countryside invites snowshoeing and Nordic skiing, while downhill types can choose from 60-plus ski mountains that together o er an impressive variety of terrain, from wide, sunny slopes to steep vertical drops.

Retirees can also reap the bene ts of living in a land of “thinkers.” While Boston may be New England’s bestknown college town (think Harvard and MIT), each of the six states has a handful of cities and towns anchored by historic colleges and universities, including Burlington,

To

Quarry Hill offers adults 55+ a gracious, maintenance-free home with easy one-floor living, plus priority access to the fullest spectrum of care.

Quarry Hill offers it all: a gracious, maintenance-free home with easy one-floor living, plus priority access to the fullest spectrum of care.

Quarry Hill offers it all: a gracious, maintenance-free home with easy one-floor living, plus priority access to the fullest spectrum of care.

Quarry Hill offers it all: a gracious, maintenance-free home with easy one-floor living, plus priority access to the fullest spectrum of care.

Quarry Hill offers it all: a gracious, maintenance-free home with easy one-floor living, plus priority access to the fullest spectrum of care.

Enjoy all the beauty and cultural sophistication of Camden, Maine, and discover your best future.

Enjoy all the beauty and cultural sophistication of Camden, Maine, and discover your best future.

Enjoy all the beauty and cultural sophistication of Camden, Maine, and discover your best future.

Enjoy all the beauty and cultural sophistication of Camden, Maine, and discover your best future.

Enjoy all the beauty and cultural sophistication of Camden, Maine, and discover your best future.

For Adults 55+

For Adults 55+

For

For Adults 55+

Pen Bay Medical Center | A MaineHealth Member 207-301-6116 | quarryhill.org

Pen Bay Medical Center | A MaineHealth Member 207-301-6116 | quarryhill.org

Pen Bay Medical Center | A MaineHealth Member 207-301-6116 | quarryhill.org

Pen Bay Medical Center | A MaineHealth Member 207-301-6116 | quarryhill.org

Pen Bay Medical Center | A MaineHealth Member 207-301-6116 | quarryhill.org

Vermont; Hanover, New Hampshire; Providence, Rhode Island; and Brunswick, Maine. ese places provide not only a youthful energy, but also the opportunity for residents to stay intellectually sharp via continuing education programs.

Arts and culture have an equally long and prestigious history in New England. Artists such as Andrew Wyeth, Edward Hopper, and Winslow Homer immortalized the region’s landscapes and seascapes, while Norman Rockwell depicted the

enduring appeal of small-town New England life in many of his illustrations. ese and many other artists helped inspire New England’s world-class collection of museums, from the Farnsworth in Rockland, Maine, to the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and the MFA in Boston.

Where arts and culture ourish, dining and shopping follow. New England’s four-season climate means there is a strong emphasis on everchanging local bounty at the region’s many award-winning restaurants. Local avor also de nes the tone at shops and boutiques selling inspired, one-of-a-kind items in quaint, walkable downtowns.

Few regions in the world can approach the variety of all New England has to o er in such a relatively small geographic area. From picturesque small towns to bustling cities, New England o ers a vision of retirement that is as authentic as it is appealing.

Few regions in the world can approach the variety of all New England has to o er.

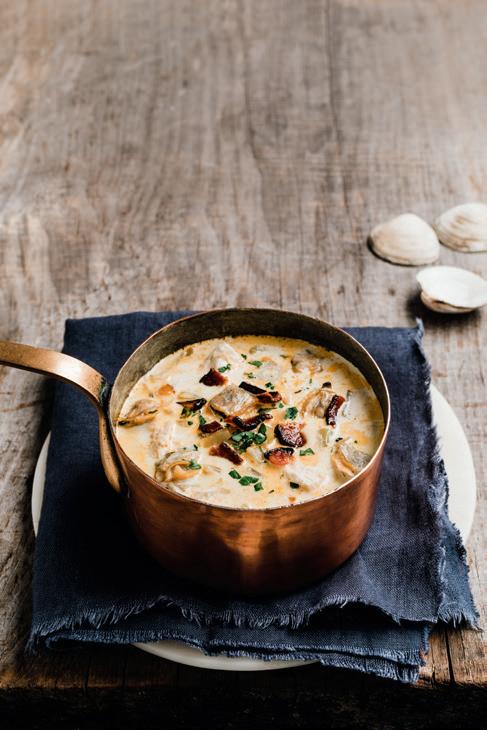

In midcoast Maine, melty cheese known as raclette is at the heart of a simple, cozy meal.

BY AMY TRAVERSO

BY AMY TRAVERSO

Roasted

On a dead-of-winter night in mid coast Maine after a full day of skiing, I walked across a snowcrusted field to a barn glowing with warm light and the promise of the ultimate après-ski meal. Outside, guests were cozying up to a trio of firepits, clutching mugs of Aquavit toddies, downing local oys ters, and looking up at a full moon. Inside, staff were attending to the finishing touches, lay ing out sheepskins and wool blankets, lighting candles, and setting out Mason jars of home made pickles.

Sarah Pike, the owner of this barn and the land on which it stands, Tops’l Farm, surveyed the scene with a mostly calm eye. This was

the 16th dinner she had hosted that winter, but there were still dozens of mouths to feed. It was all part of Tops’l Farm’s larger mission to welcome visitors to Waldoboro for glamp ing vacations, farm programs and classes, and year-round feasts.

This meal was centered around raclette, the classic French and Swiss Alpine cheese known for its great melting properties. It’s typically heated with a type of electric grill, scraped off onto plates, and served with generous mounds of boiled potatoes, cured meats, vegetables, crusty bread, and pickles. Pike’s approach, adapted for pandemic safety, is to give each table its own individual raclette spread. “Much like most everything here at the farm, it’s an

Recipes from the

Tops’l Farm in Waldoboro, Maine, include Winter Beet & Citrus Salad ( above ) and Sweet-and-Sour Pork Skewers ( right). The accompanying raclette recipe works beautifully with a number of New England–made cheeses, such as “Whitney” ( top right), a buttery-smooth mountain-style cheese by Vermont’s own Jasper Hill Farm. Recipes begin on p. 100.

expression of a lot of different life experiences,” she says.

Tonight, that inspiration came from a meal that she and her husband, Josh, had enjoyed at a Swiss restaurant called Waldhüttli (Forest Hut). “It was a 20-minute hike up into the Alps,” Pike says. “We weren’t sure whether we were on the right path, but it was one of the most magical meals of my life, in a little log cabin off the grid with a big bonfire out front. The chef came out wearing an L.L. Bean hat, and I knew I was at the right spot.”

Inside the barn, we melted slices

of raclette on a tabletop griddle and piled our plates with bread, vegetables, pickles, and meats. It wasn’t the Alps, but with a glass of local cider to wash it down, it was a perfect meal.

The raclette dinner series takes place all winter at Tops’l Farm. But if you can’t make it to Maine, Pike’s team shared their recipes for the winter salad, grilled pork skewers, and raclette (adapted for standard kitchen equipment). To finish: a butterscotch pudding recipe from Pike’s grandmother, Mom-Anne.

recipes, see p. 100)

Angel with a Golden Halo Blue Sapphire & Diamond Ring G3661...$2,950

Newcastle Seaside Blue Sapphire & Diamond Ring G3925...$6,350

Essex Blue Sapphire & Diamond Ring G4046...$9,950

The color blue is good for all of us. It is the color of health and happiness. Blue is the color of calm. Blue is our sanctuary of serenity.

We at Cross love blue and believe in all things blue. We live on a 3,500 mile coastline of blue ocean and blue skies, we think our proximity to the sea deepens our passion for great, awesome and incredible shades of blue. We search the world for the best blue sapphires, pure, true, bright, brilliant; then design our sapphires into our favorite jewelry designs. Its a longer process to build our own sapphire collection...it’s worth it though because we can have the shades of blue we and you truly love.

Anything you purchase comes with our Ninety day full return/exchange privileges. Ninety days takes the pressure off, makes shopping easy. We wish everyone did something like this, it would be a kinder, gentler world. We look forward to hearing from you.

Click & Buy or Click & Call. You may click and buy anytime. Our showroom is still closed to the public. Half our team is working remotely, the other half is safely distanced and working on shipping. You can Click & Buy 24/7 or we are taking calls Monday-Friday 9:30 AM-5PM our staff all speak New England and we will be shipping Monday-Friday all across the USA.

Two crowd-pleasing appetizers to warm up the home team.

BY AMY TRAVERSO

STYLED AND PHOTOGRAPHED BY LIZ NEILY

BY AMY TRAVERSO

STYLED AND PHOTOGRAPHED BY LIZ NEILY

or all the talk of postholiday New Year’s reso lutions and detoxes, by Super Bowl Sunday (February 12 this year) it all goes out the window in favor of chips, dips, and wings. And we are here to meet you in that truth.

To start: an ultra-creamy hot spin ach and artichoke dip nestled under a bubbling crust of mozzarella and Parmesan. We’re not breaking new ground here, but this version is nota bly delicious and packed with as many veggies as possible without losing the ooey-gooey factor.

Next, a New Englander’s take on hot wings (hint: there’s maple syrup in it). The chicken wings are tossed in salt, pepper, and garlic powder to boost their flavor, then basted with sriracha, maple, and soy sauce. Use as much or as little sriracha as you can handle (we preferred the full four tablespoons).

Butter, for greasing pan

3 10-ounce packages frozen spinach, thawed and drained

3 tablespoons olive oil

3 large garlic cloves, minced

2 14-ounce cans artichoke hearts, drained and roughly chopped

1 8-ounce package cream cheese, cut into medium cubes

1 cup sour cream

½ cup mayonnaise

¾ cup grated mozzarella cheese, plus more for the topping

½ cup grated Parmesan (or Romano) cheese, plus more for topping

2½ teaspoons kosher salt

1 teaspoon red chili flakes

Tortilla chips, for serving

Preheat oven to 375 °F and set a rack to the middle position. Grease a 9-by13-inch baking dish (or two smaller dishes or skillets). Set aside.

Squeeze out as much liquid as you can from the thawed spinach. Set aside.

In a large skillet over medium heat, warm the oil, then add the garlic and cook, stirring, until translucent. Add the spinach and artichokes, and stir to combine. Reduce heat to mediumlow and add the cream cheese, sour cream, mayonnaise, mozzarella, Par mesan, salt, and chili flakes. Stir with a spatula until the mixture is smooth

and creamy. Transfer to the prepared baking dish, sprinkle with extra moz zarella and Parmesan, and bake until golden and bubbly, about 25 minutes. Yields 8 to 10 servings.

FOR THE CHICKEN

2 teaspoons kosher salt

1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 teaspoon garlic powder

2 pounds chicken wings and drumettes, patted dry

Chopped cilantro, for garnish

FOR THE GLAZE

¼ cup maple syrup

2–4 tablespoons sriracha

1 tablespoon soy sauce

Prepare the wings: In a small bowl, stir together the salt, pepper, and

garlic powder. In a large bowl, toss the chicken with this spice mixture. Refrigerate for 30 minutes and up to 24 hours (cover bowl if refrigerating for more than 30 minutes).

Preheat oven to 425 °F and set a rack to the upper-third position. Line a rimmed baking sheet with parchment paper or aluminum foil. Set aside.

Make the glaze: In a small bowl, whisk together the maple syrup, srira cha, and soy sauce.

Arrange the wings in a single layer on the prepared baking sheet. Set on the upper third rack and bake for 30 minutes, turning halfway through. After 30 minutes, brush the top of the wings with the glaze. Return to oven for 7 minutes. Now turn the wings over and brush the other side with the glaze. Return to oven and cook until nicely browned, 5 to 7 more minutes. Sprinkle with cilantro and serve hot. Yields 4 to 6 servings.

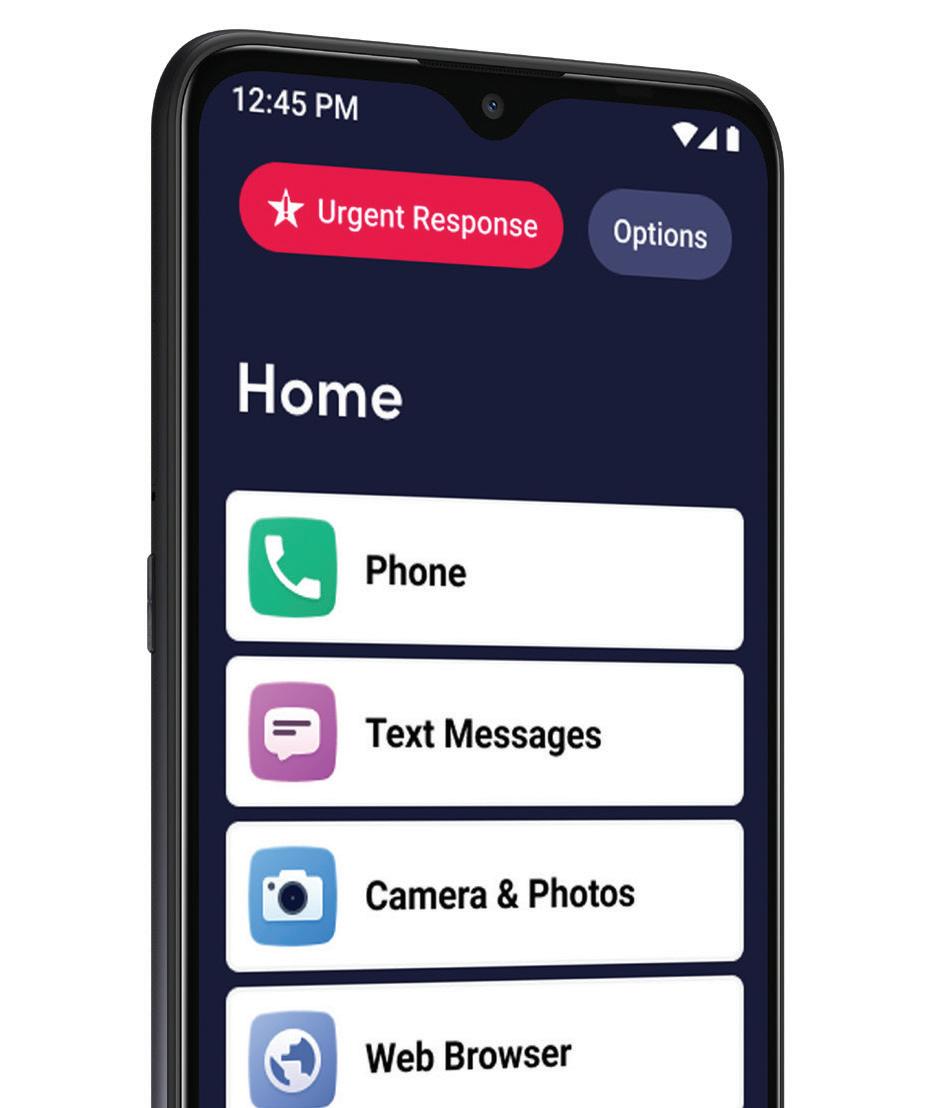

The Jitterbug® Smart3 is our simplest smartphone ever, with a list-based menu, large screen and new Health & Safety Packages available.

EASY Everything you want to do, from calling and video chatting with family, to sharing photos and getting directions, is organized in a single list on one screen with large, legible letters. Plus, voice typing makes writing emails and texts effortless.

SMART In emergencies big or small, tap the Lively Urgent Response button to be connected to a certified Agent who will get you the help you need, 24/7.

AFFORDABLE Lively® has affordable value plans as low as $14 99 a month or Unlimited Talk & Text plans only $1999 a month. Choose the plan that works best for you, then add your required data plan for as low as $249 per month2.

150% off regular price of $149 99 is only valid for new lines of service. Offer valid through 1/2/23 at Best Buy and Amazon. 2Monthly fees do not include government taxes or assessment surcharges and are subject to change. A data plan is required for the Jitterbug Smart3. Plans and services may require purchase of a Lively device and a one-time setup fee of $35. Urgent Response or 9-1-1 calls can be made only when cellular service is available. Urgent Response service tracks an approximate location of the device when the device is turned on and connected to the network. Lively does not guarantee an exact location. Urgent Response is only available with the purchase of a Health & Safety Package. Consistently rated the most reliable network and best overall network performance in the country by IHS Markit’s RootScore Reports. LIVELY and JITTERBUG are trademarks of Best Buy and its affiliated companies. ©2022 Best Buy. All rights reserved.

opposite , clockwise from top left : Firepits in the historic center of Québec City help keep visitors cozy; traditional poutine at La Souche; a snowy scene in the Old Québec district; zipping down an ice slide during the city’s annual Winter Carnival.

this page : Looking toward the grand hotel Fairmont Le Château Frontenac from the ramparts of Old Québec.

T 6 A.M. on this February day*, the city still sleeps as the icebreaker is about to leave the dock to cross the St. Lawrence River. The ferry needs only a few minutes to reach Québec City from neighbor ing Lévis, a journey I have made for 20 years while observing through the lens of my cam era. It’s always the same sense of wonder I feel when I hear the echo of cracking ice get lost in the infinity of the river, my eyes riveted on the towering Château Frontenac, one of the world’s most-photographed hotels. This morn ing, winter envelops the city, and once again time freezes. In just a few hours, about a foot of snow has fallen on the stones and bricks of Qué bec City, nicknamed “the Old Capital.” Coat, boots, gloves, toque—it’s time for a walk inside the city’s historic ramparts. At this time of day, only tourists can be seen wandering through the maze of narrow streets, as city residents armed with shovels are busy freeing their cars from huge mounds of snow.

All is white. All is quiet. Only the sound of one’s own footsteps in the snow disturbs this silence, but it also adds to the magic of

the moment. On narrow rue Couillard, the door of the café Chez Temporel opens, releas ing a warm aroma of coffee and croissants. I enter. It’s a place full of history, where the old stone walls have witnessed the work of the great Québec writers who congregated here. Warmed up, I continue my stroll to the Duf ferin Terrace, a long wooden belvedere at the foot of the Château Frontenac from which the view of the river and the Basse-Ville (Lower Town) district is unique.

Now, already noon. I hear shouts of joy from those who are sliding down the big toboggan chutes that have been one of the most popular attractions here for more than a century—1884, to be exact. From mid-December to midMarch, young and old enjoy this mammoth structure on the terrace, winter after winter, with the magnificent view of the river as the backdrop. And everywhere there is a thrill of

Chez Temporel: Since 1974, locals and visitors have come in from the cold to warm up with coffee, croissants, and local specialties at this Haute-Ville (Upper Town) favorite, while watching the stream of passersby just beyond the picture windows. cheztemporel.com

Chez Rioux & Pettigrew: In the city’s atmospheric Old Port neighborhood, foodies come here for the chef’s secret four-course prix fixe menu, while music playing on a vintage record player amplifies a timeless sense of place. chezriouxetpettigrew.com

Le Don: Québec City’s only vegan restaurant is also one of its most popular. It’s not unusual to see the same travelers returning to eat here day after day. donresto.com

Tanière³: This highend, special-occasion restaurant in a 17thcentury underground vault offers one of the most unforgettable settings you could wish for. taniere3.com/en

Le Clan: Stéphane Modat, one of Québec’s most famous chefs, opened his new eatery on an Old Québec side street. Modat’s creations are partly inspired by his time with First Nations peoples. restaurant leclan.com

Paillard: This café and bakery opens every day at 7 a.m., and its tables fill early because of its excellent breakfast sandwiches and hot drinks. paillard.ca

discovery: climbing the city ramparts, walking around the almost mythical rue Saint-Louis and rue Saint-Jean, wandering from one store to another, strolling by a fire in the Place d’Youville, heading out to play at the Winter Carnival, one of the largest and oldest events of its kind, which now is in full swing.

As the afternoon passes, snow begins to fall again. I make a last stop on the road at the Magasin Général, a legendary general store founded in 1866, before exploring the historic shopping district Petit-Champlain, in Old Québec’s Lower Town.

The Lower Town welcomes more and more tourists every year, especially in the vibrant Limoilou neighborhood. You have to check out Article 721, a little Ali Baba cave of treasures from local artisans. Around it you will find a restaurant, café, bar. The terrace of the bar Le Bal du Lézard is closed in this season, but this makes the interior all the more welcoming.

You still have to cross the river, this time via bridge to the island called Île d’Orléans. It is by stepping back that one can fully appreciate things: At the tip, in the quaint community of

Le Chic Shack: A comfort-food oasis in Québec’s Place d’Armes serving burgers, poutine, and shakes, nearly all created with local ingredients. lechicshack.ca/en

At one of Québec City’s most famous landmarks, luxury comes with stunning views of the Dufferin Terrace and the St. Lawrence River. fairmont .com/frontenac-quebec

Auberge SaintPosh accommodations combine with city history, as artifacts from an on-site archaeological dig are displayed throughout the hotel. A two-minute walk brings you to the Museum of Civilization and popular boutiques in the Petit-Champlain district. saint-antoine.com

Hôtel Le Priori: Located on a pretty pedestrian street in a building that dates back to 1734, Le Priori is a cozy and plush boutique hotel, with an interior design featuring brick and stone walls, plus gourmet breakfast. hotellepriori.com/en

Magasin Général: An old-fashioned country store that has long been a local landmark, it’s the kind of place you enter thinking you’ll stop for a few minutes—then you souvenir-hunt for an hour. Facebook

Article 721: Artisanal gifts from some 60 Québec makers, along with vintage finds, fill this beguiling shop in the

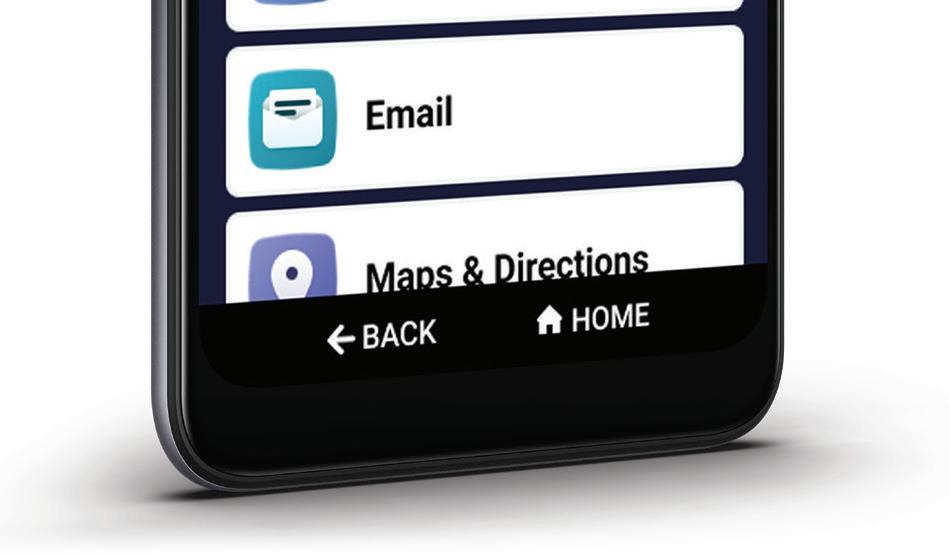

Today, cell phones are hard to hear, difficult to dial and overloaded with features you may never use. That’s not the case with the Jitterbug® Flip2, from the makers of the original easy-to-use cell phone.

EASY TO USE A large screen, big buttons, list-based menu and one-touch speed dialing make calling and texting easy. The powerful speaker ensures conversations are loud and clear.

EASY TO ENJOY A built-in camera makes it easy to capture and share your favorite memories, and a reading magnifier and flashlight help you see in dimly lit areas. The long-lasting battery and coverage powered by the nation’s most reliable wireless network help you stay connected longer.

EASY TO BE PREPARED Life has a way of being unpredictable, but you can press the Urgent Response button and be connected with a certified Urgent Response Agent who will confirm your location, assess the situation and get you the help you need, 24/7.

EASY TO AFFORD The Jitterbug Flip2 is one of the most affordable cell phones on the market with plans as low as $1499/mo. or Unlimited Talk & Text for only $1999/mo. And with no long-term contracts or cancellation fees, you can switch plans anytime. Plus, ask about our new Health & Safety Packages.

125% off $9999 regular price is only valid for new lines of service. Valid through 12/31/22 at Rite Aid and Walgreens and 1/2/23 at Best

directors of the famous Disney movie Just a 20-minute drive or public shuttle from the city center, it is a dreamlike place, a world of ice and snow. Built with more than 2,000 blocks of ice and tons of snow, it is the only ice hotel in North America, where every year engineers and artists reinvent its theme and spaces.

A view across the frozen St. Lawrence River from Île d’Orléans. Freshwater for much of its length, the St. Lawrence freezes during the winter months, providing visitors the chance to walk out onto its icy expanse.

In Wendake, the Huron-Wendat Nation res ervation located 15 minutes from the city, visi tors are greeted with open arms at the HuronWendat Museum and Huron Traditional Site. A stay in Québec City would be incomplete without a visit to this site of great richness, which allows us to understand the past, the his tory of the territory that welcomes us.

Limoilou neighborhood. article721.com

Benjo: Amid electric trains, stuffed animals, and a dozen special toy departments, winter visitors young and old will warm up quickly at this 25,000-square-foot destination toy store. benjo.ca/en

Rue du PetitChamplain: One of the most inviting window-shopping streets anywhere, this cobblestoned walkway lined with boutiques is considered the oldest commercial street in North America. quebeccite.com/en/old-quebeccity/petit-champlain

Hôtel de Glace: You can spend a bundledup overnight here, sleeping in a bed carved from ice, but simply touring this architectural wonder will give you chills of amazement. valcartier.com/en/ accommodations/hotelde-glace-ice-hotel

Wendake: A step back in time 15 minutes outside the city, where you immerse yourself in the First Nations culture and experience, complete with galleries and crafts that honor ancient traditions. tourismewendake.ca/en

Dufferin Terrace and Toboggan Run: Enjoy the thrill of strolling the famous promenade overlooking the river, then speeding down the slide. This signature Québec City winter experience ends with a warm-up snack at the kiosk next to the Château Frontenac. au1884.ca/en

It’s complicated.

Here’s some advice from a licensed therapist.

Whether you’re experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depression, feeling burned out at work, or navigating relationship challenges, therapy can be an effective tool for building resilience and improving your mental health. But finding therapy that works for your schedule, budget, and goals can be challenging. Here are some pointers to make therapy less daunting, and help you get the care you’re looking for:

1. Understand that therapy can be for anyone. Therapy isn’t only for people who have been diagnosed with a severe mental health issue. Mental health is for everyone. Therapy can be beneficial even if you just need someone to talk to.

2. Be kind to yourself — seeking therapy is a sign of strength, not of weakness. Free yourself from the stigma that can be associated with seeking mental health care. Starting therapy is a sign that you’re taking ownership of your narrative, and prioritizing your mental health. It takes a lot of bravery, and it’s something to be proud of.

3. Stay open to different specialties. There are a lot of different licenses in the mental health profession — from psychologists to social workers — but the most important thing is finding a therapist that you feel safe with. Make that a focus of your search.

4. Think about whether you’d prefer to do therapy in-person or virtually. Virtual therapy can be done from home, offers a much wider selection of providers, and is often more affordable. BetterHelp, for example, has a network of over 25,000 licensed therapists and costs between $60-$90 a week. On the other hand, in-person therapy can be more appropriate for people with mental

health challenges that may require in-person care, like substance abuse issues or severe eating disorders.

5. Try messaging with your therapist first if you don’t feel ready for a full session. Starting therapy with someone you’ve never met before can be scary. If that feels like too much, start by messaging with your therapist, which is an option on BetterHelp and some other online providers. Messaging can be a very effective tool for processing feelings on your own time and getting to know your therapist a little bit better.

6. Consider the cost. If you have insurance, call the number on the back of your card to see whether there are affordable providers in-network. For non-insurance options, consider an online provider like BetterHelp, which charges significantly less per hour for regular sessions. Finally, consider group sessions, where you share the cost of services with others in a discussion-based format.

7. Don’t get discouraged if the first therapist you speak with isn’t the right fit. Therapy is super personal, and sometimes it takes a few tries to find someone you connect with enough to continue working with them in the long term. Finding a good match can take time, and it can make a huge difference. Some services, like BetterHelp, make it easy to switch between therapists and can work with you to help you find the right match.

Starting therapy is a major step — and one that can take a lot of courage and time. The work you put in up front is an investment in your long-term wellness. In my decade as a therapist, I’ve seen the transformative effect that therapy can have on people’s lives. If you’re considering it, take the leap and give it a try.

Scan the QR code or visit betterhelp.com/yankee for 10% off your first month.

abilities, including challenging steeps. It’s affordable, it’s quiet, and it’s a clas sic. blackmt.com

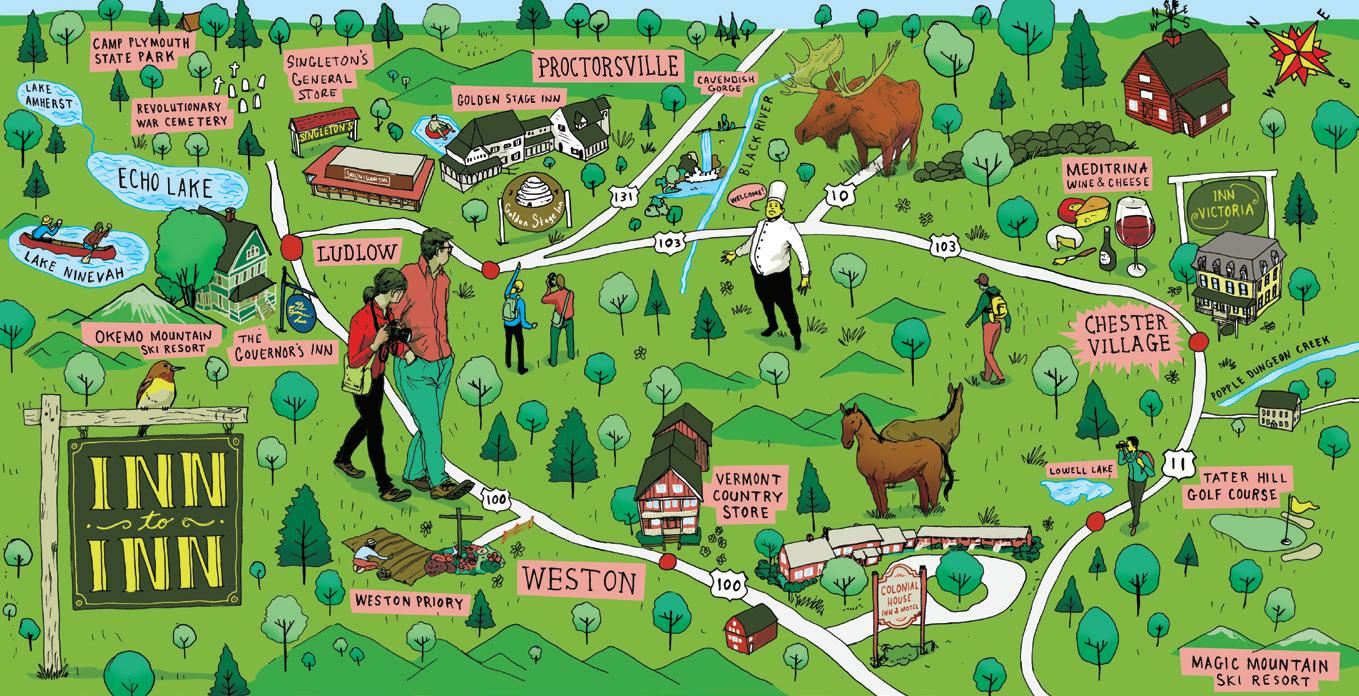

Thanks to its down-to-earth vibe, Magic is often compared to the oldschool ski co-op Mad River Glen— high praise from the Vermont ski community. Combine that welcoming attitude with lots of recent infrastruc ture updates, 135 skiable acres, and brand-new snowmaking machines, and voilà : the best of both worlds. magicmtn.com

Richmond, VT

Locally owned Bolton Valley boasts more than 300 inches of natural snow per year, 70-plus ski trails, and the highest base elevation of any ski resort in the Northeast. But despite being nestled between superstars Stowe and Sugarbush, it avoids its neighbors’ lime light. This is a perfect place to explore the Green Mountain ski scene, espe cially if you’re hoping to avoid crowds of others doing the same. boltonvalley.com

Mendon, VT

refer hitting the slopes over waiting in long lift lines? These lesserknown New England ski moun tains offer all the fun you’re seeking this winter—without the crowds.

Katherine Keenan

Katherine Keenan

Saddleback Mountain Rangeley, ME

Though its future once seemed grim, after five years of closed lifts Saddle back is back in a big way. The west ern Maine location is a bit remote,

but with more than 600 skiable acres of diverse terrain, reasonably priced tickets, and next-to-nonexistent lift lines, this place is worth it. So if you’re up for the drive, start your engine. saddlebackmaine.com

Black Mountain Jackson, NH

This historic gem (c. 1935) in the heart of the White Mountains comes with some of the best summit views in the state. Grab a map, take a lift to the top, and spend the day amid 45 trails for all

It’s widely regarded as a little brother to Killington, just six miles away, but Pico’s nearly 2,000 feet of vertical drop puts it up there with some of the most popular mountains in the East— except here you’ll almost always find parking close to the lodge. Pico is owned by Killington, so it has that well-oiled resort feel, but the lift lines are comparatively short. First-timers will find comfort in the beginners’ area, and those looking for a chal lenge can test their chops on winding black diamonds. What’s not to love? picomountain.com

On the island of Martha’s Vineyard Forrest Pirovano’s painting “Edgartown Light” shows a lighthouse at the entrance of Edgartown Harbor

Edgartown Harbor Light in Edgartown, Massachusetts marks the entrance to Edgartown Harbor and Katama Bay. It is one of five lighthouses on the island of Martha’s Vineyard. Built in 1828 as a two-story wooden structure, it also served as the keeper’s house. In 1939, it was replaced by the current cast-iron tower relocated to Martha’s Vineyard from Crane’s Beach in Ipswich. The lighthouse originally located on an artificial island 1/4 miles from shore is now surrounded by a beach formed by sand accumulating around the stone causeway connecting it to the mainland. This beautiful limited-edition print of an original oil painting, is individually numbered and signed by the artist.

This exquisite print is bordered by a museum-quality white-on-white double mat, measuring 11x14 inches. Framed in either a black or white 1 ½ inch deep wood frame, this limited-edition print measures 12 ¼ X 15 ¼ inches and is priced at only $149. Matted but unframed the price for this print is $109. Prices include shipping and packaging.

Forrest Pirovano is a Cape Cod artist. His paintings capture the picturesque landscape and seascapes of the Cape which have a universal appeal. His paintings often include the many antique wooden sailboats and picturesque lighthouses that are home to Cape Cod.

FORREST PIROVANO, artist P.O. Box 1011 • Mashpee, MA 02649 Visit our studio in Mashpee Commons, Cape Cod

All major credit cards are welcome. Please send card name, card number, expiration date, code number & billing ZIP code. Checks are also accepted.…Or you can call Forrest at 781-858-3691.…Or you can pay through our website www.forrestcapecodpaintings.com

EDGEWOOD MANOR, Cranston . Just south of Providence and blocks from Edgewood Lake and its surrounding park, Edgewood Manor and its adjacent Newhall House are a B&B alternative to staying in the busy capital. Edgewood’s Victorian-themed rooms offer amenities such as four-poster or sleigh beds and two-person Jacuzzi tubs; two have woodburning fireplaces, and a gas hearth. providence-lodging.com

THE NATIONAL HOTEL, Block Island . Not one but eight firepits enliven the grounds at the National Hotel, a Victorian confection dating to 1888 and rebuilt after burning down in 1902 (a hint, perhaps, as to why today’s fires are kept outdoors). The waterfront hotel’s backyard blazes are the perfect place to sip a cocktail and ward off the evening

chill after a day spent exploring the island. blockislandhotels.com

OCEAN HOUSE, Watch Hill . The grande dame of the Rhode Island coast is Ocean House, a sprawling yellow structure that’s a near-exact replica of the original Victorian hotel, with splendid additions and amenities that have earned it Relais & Châteaux status. Top-end suites have gas fireplaces, but the lobby features a stone-by-stone reconstruction of the original building’s great wood-burning hearth. oceanhouse.com

THE WHITE HORSE TAVERN, Newport. There was a Newport long before the Gilded Age, and the White Horse Tavern brings that colonial heyday vividly back to life. Built in 1673, and a purveyor of food and drink for much of its history, the tavern boasts, in its downstairs dining room, a fireplace that once warmed George Washington. whitehorsenewport.com

THE WYNSTONE, Newport. Don’t look for hip minimalism at The Wynstone, downtown Newport’s small-hotel tribute to the Gilded Age. Appropriately, guest rooms are named after the palatial “cottages” built by summering magnificoes at the turn of the last century. The Breakers, Kingscote, Elms, Rosecliff, Belcourt, and so on. All the rooms here are sumptuously decorated, and four feature working, wood-burning fireplaces. innsofnewport.com

BLACKBERRY RIVER INN, Norfolk . “Bed and Breakfast” is almost too pedestrian a category for this southern Berkshires gem built in 1763. Two inviting upstairs

and

destinations offer a warm respite from winter.

In addition to chocolate truffles and caramels, the Massachusetts outpost of New Mexico–based Kakawa Chocolate House has an intoxicating menu of hot chocolate “elixirs.” Inspired by Mayan, Aztec, and historic European and Colonial American recipes, to name a few, the options include Mexican Rose Almond, 1666 Italian Citrus, and a Thomas Jefferson blend flavored with nutmeg and vanilla. Among the modern picks are Chocolate Chai and Havana Rum. Salem, MA; kakawachocolates.com

The Providence Rink is the only place in New England where on-ice collisions are encouraged. Reserve your ice bumper car, a cool reinvention of the classic carnival ride, and spend 15 actionpacked minutes spinning, slamming, ricocheting … and appreciating the architectural diversity of one of America’s oldest cities. Drivers must be at least 6, but kids as young as 3 can ride with adults. Providence, RI; the providencerink.com

Need a little artistic inspiration for your next snowman-building session?

Check out the talent on display at The Flurry, a snow sculpture festival and competition at Vermont’s Saskadena Six, whose past winners have gone on to compete at the national level. 1/13–1/15. Woodstock, VT; saskadenasix.com

“Taking the waters” may be an ancient wellness practice, but a hydrotherapy experience at Bodhi Spa feels like a remedy for 21st-century winter blahs. Luxuriate in 98- and 104-degree mineral pools, dry and infrared saunas, and a eucalyptus steam room; in between, brave a 55-degree cold plunge pool. A two-anda-half-hour session ($85) allows you to cycle through the Water Journey until you’re basically blissed-out mush. Newport & Providence, RI; thebodhispa.com

COMB A WINTER BEACH Secure the hood on your parka, then head down the steps to Cape Cod’s Lighthouse Beach . This picturesque cove is a treasure, and in winter you may have it all to yourself. Walk the ever-changing tideline to see what the ocean has delivered; look across the waters, and you may spot a seal. Here is a beach you can even enjoy from the comfort of your heated vehicle: Arrive just before sunset, park in the overlook lot, and stay until the pink streaks turn to indigo. Chatham, MA; chathaminfo.com/beaches

TAKE A

TO REMEMBER AT SUNDAY RIVER. With eight separate peaks served by 18 lifts, the slopes are hopping all day long at this sprawling Maine resort. But after the sun goes down, catch a different kind of rush by walking through a winter forest sparkling with more than 100,000 lights, as the Après Aglow display returns bigger and brighter in this, its second year. Newry, ME; sundayriver.com

Going snow tubing is accessible, easy, a ordable —and one ride is all it takes to bring out your inner kid. Spend a full day on the 18 lanes of Nashoba Valley Tubing Park, New England’s largest, in Littleton, MA, or go old-school at Great Glen Trails in Gorham, NH, which mixes uphill hiking with downhill zooming. But no matter where in New England you go, remember: If you aren’t grinning by the end, you’re doing it

wrong. skinashoba.com; greatglentrails.com

With over four miles of cleared ice, Vermont’s Lake Morey Skate Trail is the longest in the country, providing a runway for skaters to take flight into a stunning winterscape. Fairlee, VT; lakemoreyresort.com

ESCAPE TO THE TROPICS. When winter feels relentless, grab that steamy beach read you never actually opened last summer and point your getaway vehicle toward one of New England’s pockets of tropical warmth.

It’s 70 degrees at all times inside New England’s largest glass-house garden: the Roger Williams Park Botanical Center in Providence, RI. Fountains burble, camellias blossom, 40-foot palm trees stretch toward the sun. And you’ll feel the warmth tingling from the top of your head to the tips of your toes as you inhale the heavenly scent of Calamondin oranges. Tropical sensations are likewise guaranteed inside the Lyman Conservatory at Smith College in Northampton, MA. One of the nation’s oldest plant havens, this 12-greenhouse complex’s jungle-like Palm House [pictured] is always kept humid and at least 70 degrees for the comfort of its specimens, some of which are a century-plus old. You’ll feel better able to endure winter’s worst after spending time with these survivors and stopping to smell the flowering orchids and rhododendrons. providenceri.gov/ botanical; garden.smith.edu/plants

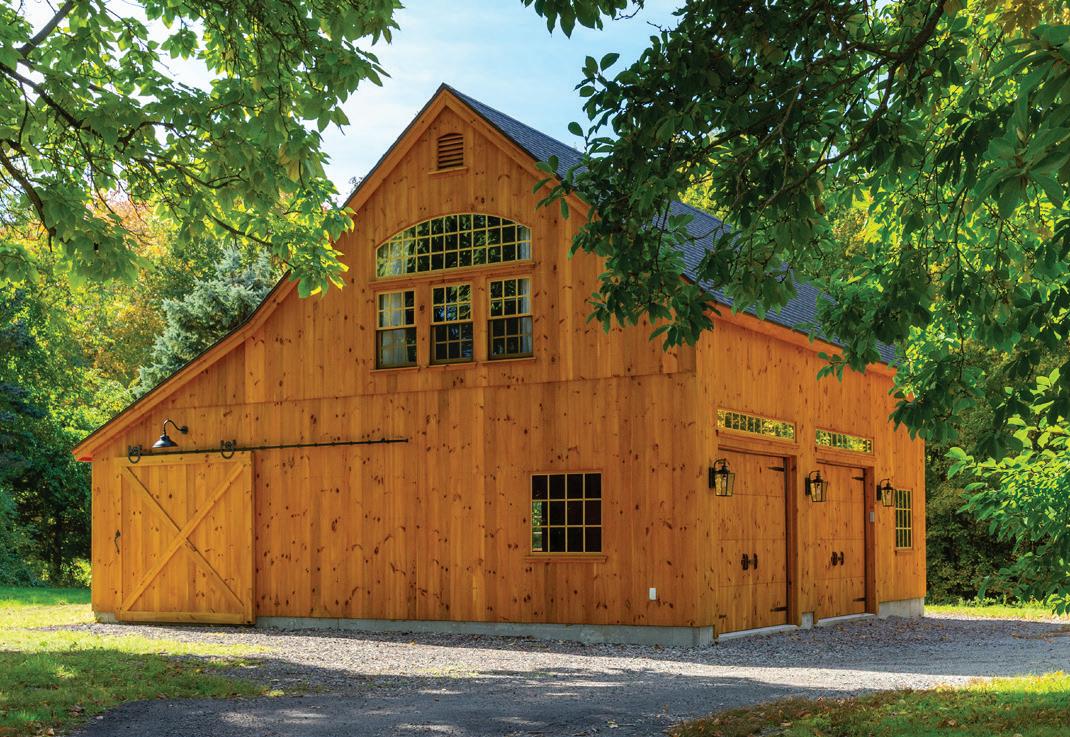

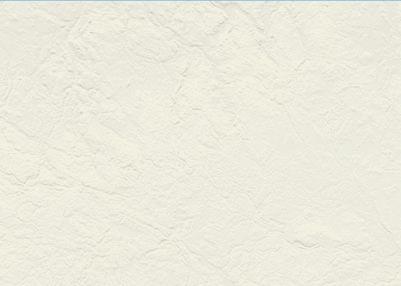

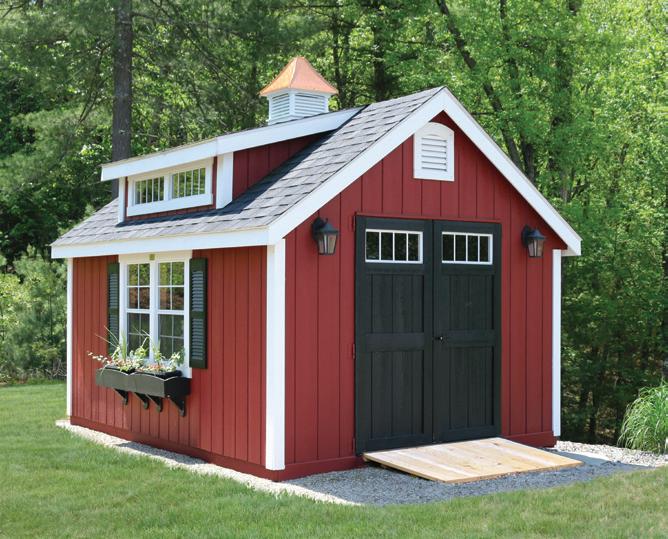

Or even better, let John Gorka, Patty Larkin, Lucy Kaplansky, and Cli Eberhardt handle the vocals. That’s the Feb. 14 lineup at Maine’s Stone Mountain Arts Center. This unique performance space is the brainchild of singer-songwriter Carol Noonan, who one day realized the timber barn built by her husband, Je Flagg, had astounding acoustics. It took planning and a quick lift of the barn (the neighbors all pitched in to handle the ropes to guide it to a new foundation), but now Carol and Je host headliners all year long. Brownsville, ME; stonemountainarts center.com

11GREET THE YEAR OF THE RABBIT. In celebration of the Chinese New Year, lion dancers and clowns lead the colorful annual parade in Boston’s Chinatown, and the sounds of drums, gongs, and firecrackers will lead you to multiple processions across the neighborhood. Postparade, feast at Yankee food editor Amy Traverso’s modern favorite, Shojo, or enjoy classic fare at Peach Farm, the Chinatown restaurant beloved by none other than Julia Child. 2023 parade date TBA; bostonusa.com/events

Staying hip is a tall order for any centenarian, but the 112-year-old Dartmouth Winter Carnival has proven itself adaptable. Gone are the ski jumps and beauty pageants, replaced by polar bear plunges, human dogsled mushes, downhill canoeing, costumed ski racing, and more. Classic touches remain, though, including sleigh rides and ice skating, plus a showing of Winter Carnival, Hollywood’s 1939 take on this February icon. 2/9–2/12. Dartmouth, NH; home.dartmouth.edu

AT

PANCAKE PARLOR. The pancakes come stacked high or low, in varieties ranging from plain to blueberry to gingerbread to gluten-free. Oldtimers can order baked beans on the side; whippersnappers get nitro cold brew. In other words, there’s no one that the crew at Polly’s can’t please. Whether you’ll be skiing Cannon Mountain or just sitting by the fire, there’s no sweeter way to start your day. Sugar Hill, NH; pollyspancakeparlor.com

Located in a wildlife preserve, the Frosty Drew Observatory is the real deal, with working astronomers, giant telescopes, and some of the darkest skies in the region. On celestial tap this winter: the annual Quadrantid Meteor Showers, two micromoons (full moons occurring close to apogee, the farthest point in the lunar orbit), and Comet C/2022 E3 ZTF. It’s open to the public for Friday stargazing nights year-round, and for special events if that comet gets bright enough! Charlestown, RI; frostydrew.org

. In February and early March, when you board the 64-foot RiverQuest tour boat at the Connecticut River Museum for a two-hour naturalist-led cruise, your purpose is clear: to see the fierce beauty of bald eagles in flight or guarding their nests, evidence of the rebound of a once-endangered species. These are prime feeding grounds for eagles and other raptors, and while nature offers no guarantees, passengers often see dozens of majestic birds. Essex, CT; ctrivermuseum.org/eagle-cruises

DINE