HOME & GARDEN

IF THESE WALLS COULD TALK

Step inside the 1851 farmhouse where Russ Morash launched a DIY revolution, p. 74

IF THESE WALLS COULD TALK

Step inside the 1851 farmhouse where Russ Morash launched a DIY revolution, p. 74

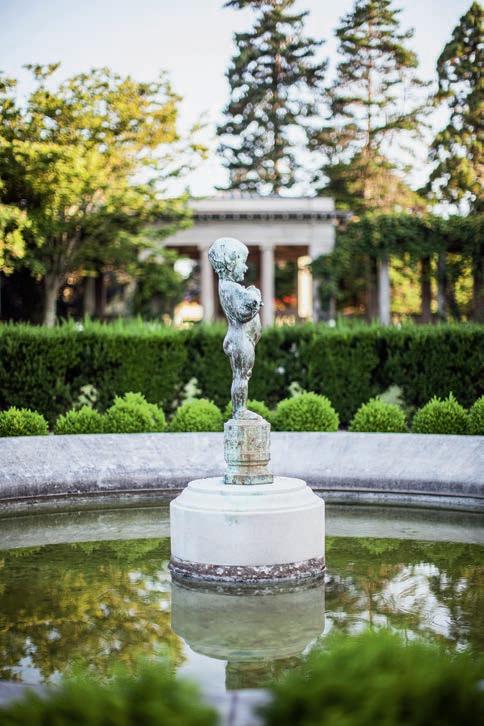

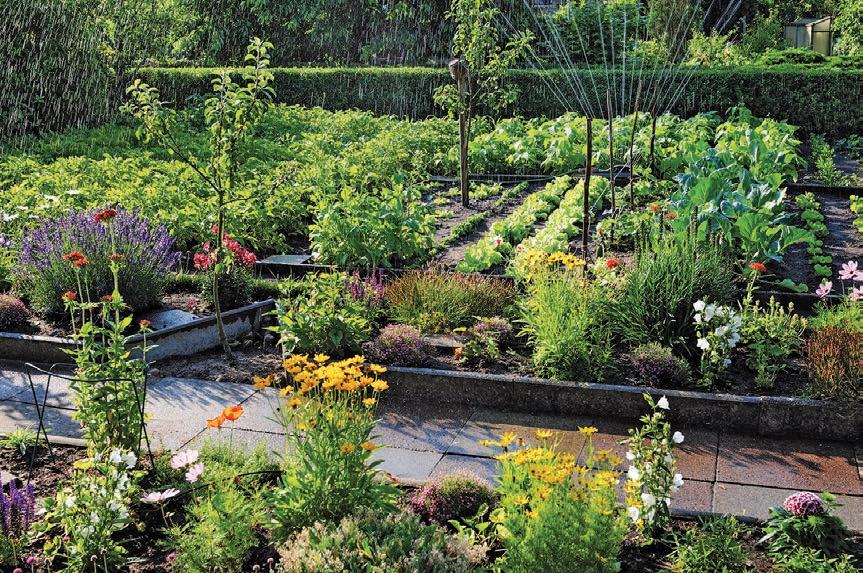

62 /// Estates of Grace

Cultivate your sense of wonder amid New England’s historic garden landscapes. By Kim Knox Beckius

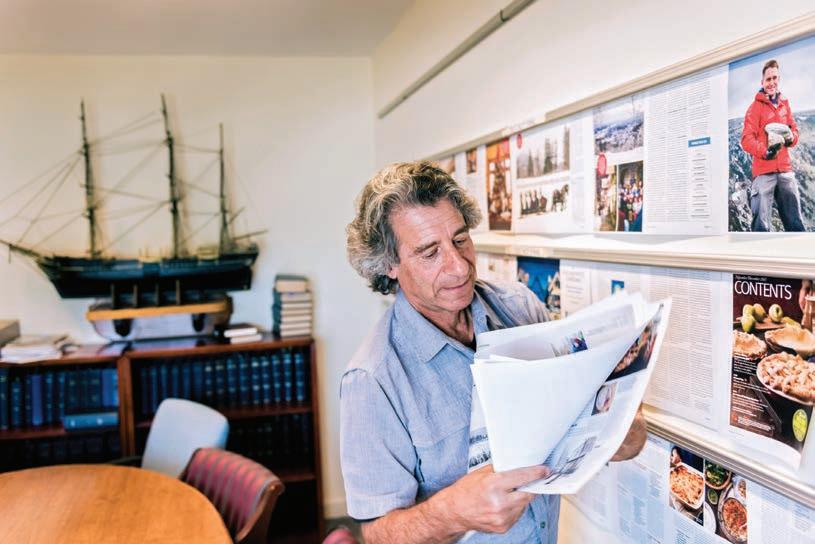

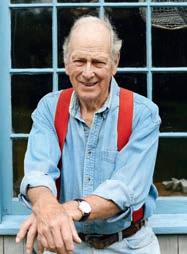

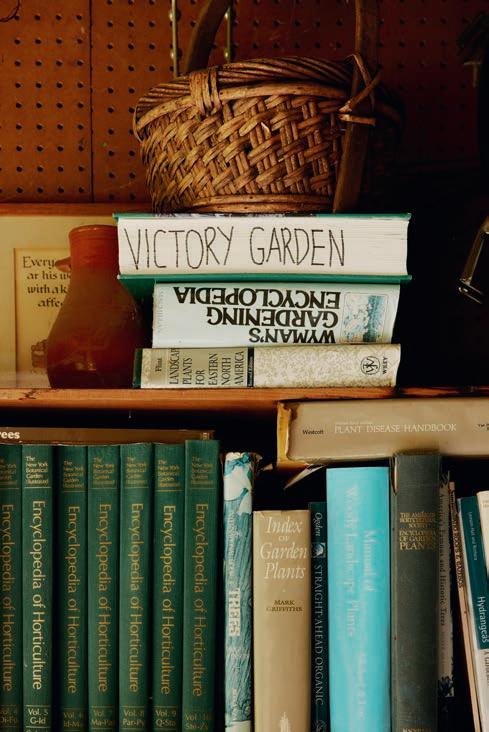

74 /// Master of the House

When it came to building a new genre of television, This Old House creator Russ Morash went DIY all the way. By Bruce Irving

80 /// Silent Witness

Seeing the Bunker Hill Monument soaring skyward,

we’re reminded that it holds national memories that run incredibly deep. By Howard Mansfield

84 /// The Lobster Trap

When you grow up with generations of tradition, change can be both welcome and feared. By Ian Aldrich

92 /// Blast from the Past

Nearly 90 years after Mount Washington was struck by world-record-setting winds, one writer heads to the summit to conjure up that historic day. By Rachel Slade

On this enchanting 9-day cruise from Charleston to Amelia Island, experience the charm and hospitality of the South. In the comfort of our modern fleet, travel to some of the most beautiful historic cities in America. The fascinating sites you visit, the warm people you meet, and the delectable cuisine you taste, come together for an unforgettable journey.

Small Ship Cruising Done Perfectly

26 /// Rock Stars

How a 19th-century masonry technique from Scotland created a treasure trove of rare buildings in Vermont. By Bruce Irving

32 /// Feats of Clay

In the home or in the garden, the whimsical creations of D. Lasser Ceramics lend a welcome jolt of color. By Bill Scheller

36 /// Lessons of a Very Old House

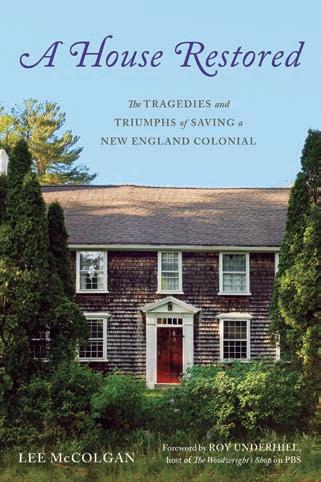

What a three-century-old Colonial taught its owner about his place in the world today. By Lee McColgan

10

INSIDE YANKEE

On the eve of retirement, our editor looks back on his own long stretch of Yankee ’s 90-year history.

16

PERSON

40 /// Season’s Greetings

A food-forward preview of Weekends with Yankee season 9, premiering on public television stations this spring. By Amy Traverso

46 /// In Season

Maple syrup shines in these sweet and savory recipes. By Amy Traverso

One last ski day reminds a father how quickly children grow up. By Brian Kevin

18

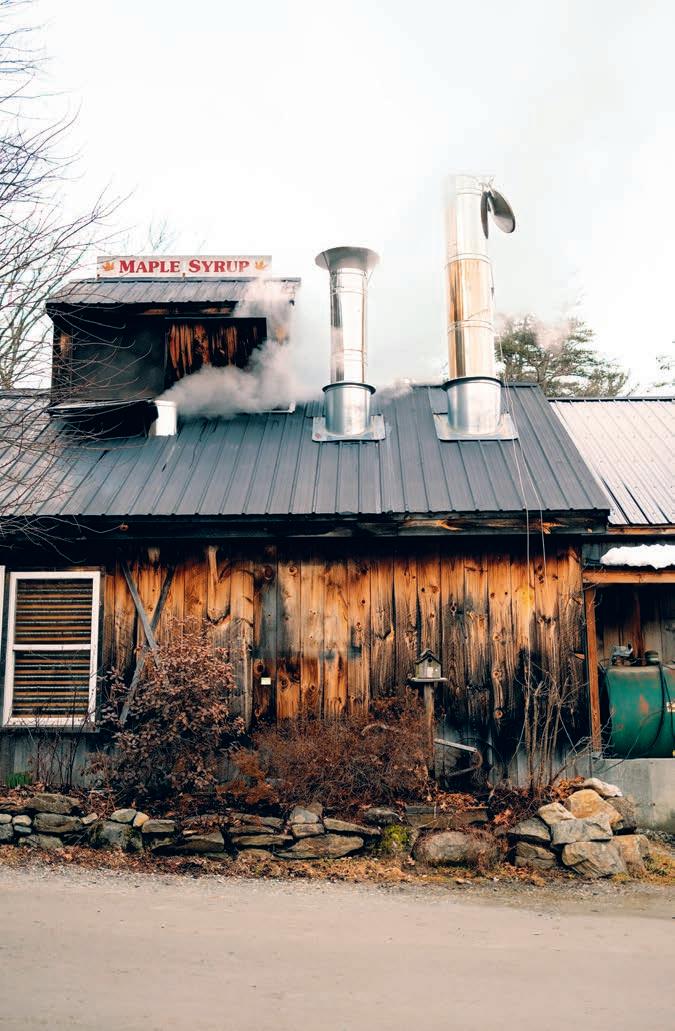

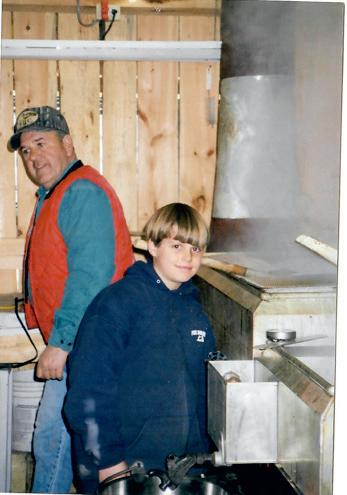

Tracing a maple syrup empire back to a boyhood dream. By Annie Graves

Fenway Park’s eye-catching tribute to Ted Williams’s record-setting home run. By Todd Balf

120

LIFE IN THE KINGDOM

Some places we never leave, but instead carry with us all our lives. By Ben Hewitt

50 /// Weekend Away

A proud history of invention meets a thoroughly modern mix of art, culture, and dining in Worcester, Massachusetts. By Annie Sherman

58 /// Flair Fresheners

Our roundup of New England home and garden shops that are worth the drive. By Elyse Major

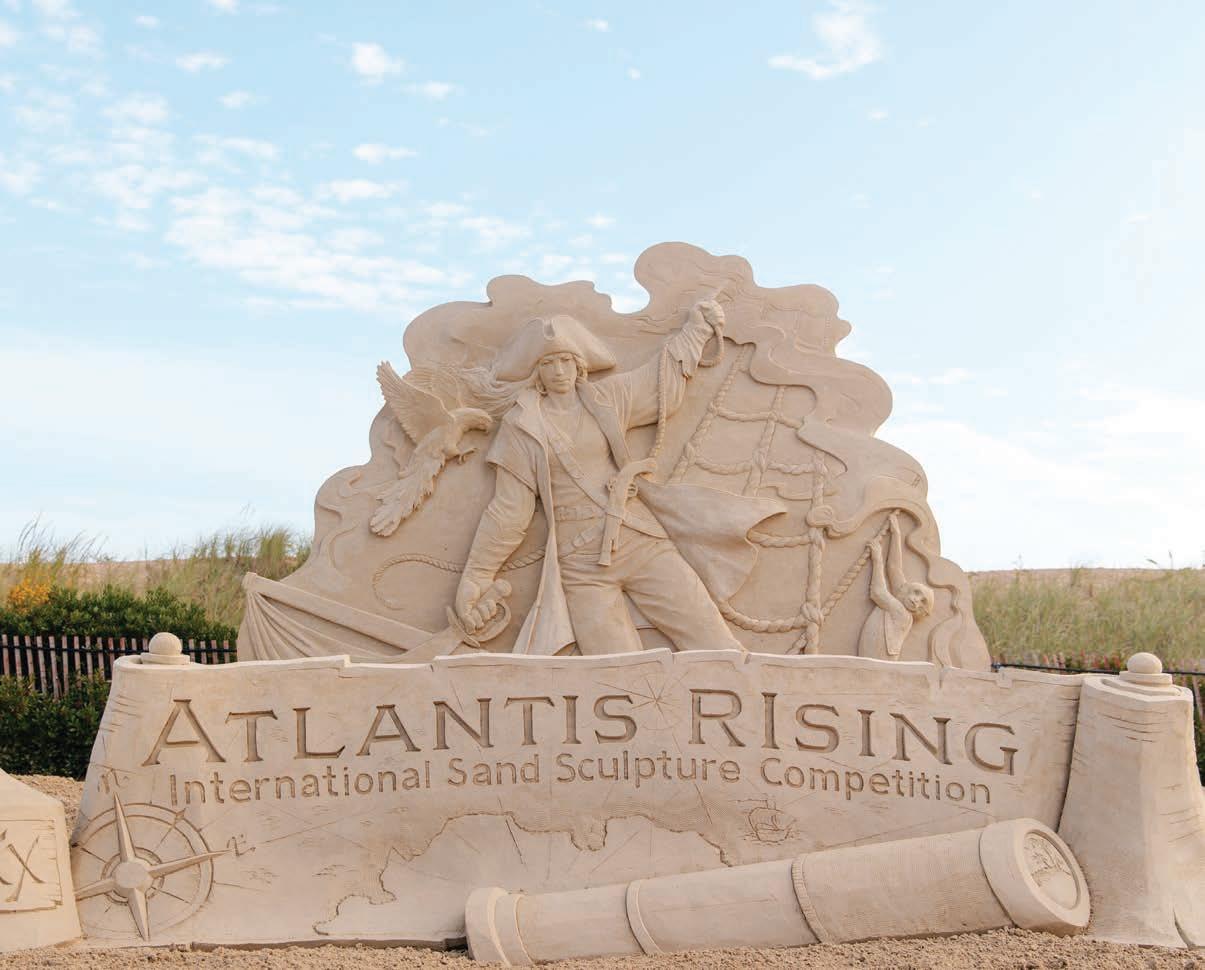

Artists from around the world will convene in South County, RI this May to compete in a sand sculpture competition for a cash prize. Come watch, them work, see live music, shop, eat, and play! May 30 - June 1 in Ninigret Park. Learn more at SouthCountyRI.com

Publisher Brook Holmberg

Editor Mel Allen

Senior Managing Editor Jenn Johnson

Executive Editor Ian Aldrich

Senior Food Editor Amy Traverso

Senior Digital/Home Editor Aimee Tucker

Travel/Branded Content Editor Kim Knox Beckius

Associate Editor Katrina Farmer

Contributing Editors Ben Hewitt, Rowan Jacobsen, Nina MacLaughlin, Bill Scheller, Julia Shipley, Kate Whouley

ART

Art Director Katharine Van Itallie

Senior Photo Editor Heather Marcus

Contributing Photographers Adam DeTour, Megan Haley, Corey Hendrickson, Michael Piazza, Greta Rybus

PRODUCTION

Director David Ziarnowski

Manager Brian Johnson

Senior Artists Jennifer Freeman, Rachel Kipka

Vice President Paul Belliveau Jr.

Senior Designer Amy O’Brien

E-commerce Director Alan Henning

Digital Manager Holly Sanderson

Marketing Specialist Jessica Garcia

Email Marketing Manager Eric Bailey

Customer Retention Marketer Kalibb Vaillencourt

E-commerce Merchandiser Specialist Nicole Melanson

ADVERTISING

Vice President Judson D. Hale Jr.

Media Account Managers Kelly Moores, Dean DeLuca , Steven Hall

Canada Account Manager Cynthia Fleming

Senior Production Coordinator Janet Selle

For advertising rates and information, email sales@yankeepub.com or go to newengland.com/adinfo.

ADVERTISING

Director Kate Hathaway Weeks

Senior Manager Valerie Lithgow

Marketing Assistant Natalia Rivera

PUBLIC RELATIONS

Roslan & Associates Public Relations LLC

YANKEE PUBLISHING INC.

ESTABLISHED 1935 | AN EMPLOYEE-OWNED COMPANY

President Jamie Trowbridge

Vice Presidents Paul Belliveau Jr., Ernesto Burden, Judson D. Hale Jr., Brook Holmberg, Jennie Meister, Sherin Pierce

Editor Emeritus Judson D. Hale Sr.

CORPORATE STAFF

Vice President, Finance & Administration Jennie Meister

Human Resources Manager Beth Parenteau

Information Manager Gail Bleakley

Assistant Controller Nancy Pfuntner

Accounting Associate Meg Hart-Smith

Accounting Coordinator Meli Ellsworth-Osanya

Executive Assistant Christine Tourgee

Maintenance Supervisor Mike Caron

Facilities Attendant Ken Durand

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Andrew Clurman, Renee Jordan, Joel Toner, Jamie Trowbridge, Cindy Turcot

FOUNDERS

Robb and Beatrix Sagendorph

NEWSSTAND

Vice President Sherin Pierce

NEWSSTAND CONSULTING

Linda Ruth, PSCS Consulting

SUBSCRIPTION SERVICES

To subscribe, give a gift, or change your mailing address, or for any other questions, please contact our customer service department:

Mail: Yankee Magazine Customer Service P.O. Box 37900, Boone, IA 50037-0900

Online: newengland.com/contact-us

Email: customerservice@yankeemagazine.com

Toll-free: 800-288-4284

Yankee occasionally shares its mailing list with approved advertisers to promote products or services we think our readers will enjoy. If you do not wish to receive these offers, please contact us.

Yankee Publishing Inc., 1121 Main St., P.O. Box 520, Dublin, NH 03444 / 603-563-8111 / editor@yankeepub.com Printed in the U.S.A. at Quad Graphics

Hosts Amy Traverso, Richard Wiese

Directors of Photography

Corey Hendrickson, Jan Maliszewski

Editor Travis Marshall

Executive Producer Laurie Donnelly

Senior Producer Mercedes Velgot

Associate Producer Nora Kirrane

American

Massachusetts

New

Country

Grady-White Boats

he first time I knew the feeling of leaving home I was a month shy of 11, though what I felt then was home leaving me. My mother, sister, and little brother went to spend the summer on the island of Jamaica, where my mother had grown up and where her parents still lived. I stayed home to play Little League. A strange sense of loneliness soon settled in, as I waited all day in the unfamiliar quiet for my dad to come home to take me to practice or a game, and afterward we’d go to a diner or simply open a carton of ice cream. I never forgot what I learned that summer: Home did not just mean a roof and walls and familiar rooms, but the people you lived with inside.

Since then, I have left numerous homes: off to college, leaving college, leaving the Peace Corps, leaving Maine. Then I came to Yankee in October 1979—and never left. I have been part of more than 400 issues of this magazine. I have lived tens of thousands of hours inside this sprawling red building, have worked alongside so many people here, have known and published so many writers. There has been little distance for me between home with family and my second home here with another family— one where day after day we talk ideas, plan issues, look at layouts, meet in hallways and offices, look after each other.

My coworkers have been part of my life for so long that I’ve been here when their children were born and I’ve seen those kids grow up and have their own children. I have lost colleagues I will never forget, and I have welcomed new ones I will never forget.

For the past few years, when people asked me when I was going to retire, I replied by saying they don’t understand the feeling of holding a new issue in their hands, or of finding a story that arrives unassigned, like a stranger knocking on the door asking to come in, and then

beginning to read it and knowing Yankee ’s readers will want to read it, too. They don’t understand what it’s like to get a phone call from a friend to say she’s seen a Facebook post about a Maine lobsterman named Joel Woods who takes photos of a life that few of us ever know. And then to sit in Woods’s cottage on the Maine coast and see his work, and then publish it, and then enter it in the annual City and Regional Magazine Association contest to be judged against photos by professionals across the country. (Joel Woods took first place.)

And then there is that hard-to-define connection with readers, so strong at times I can almost hear their voices when they write. I have kept hundreds of their cards and letters and several thousands of their emails, which speak to a bond that runs deeper than just editor and subscriber. They want me to know how much Yankee means to them. They tell of losses in their lives and how Yankee kept them grounded, how we have kept New England alive for them no matter where they live. They talk about their family as if we here at Yankee all belonged, too.

They write things like this: Dear Mel, I think I can be so familiar as to call you by your first name though we have never met in person; we have known each other for decades, though only through Yankee.

Or this one, a nod to my long-standing editor’s photo: Check your closet, Mel. Caught between all those red shirts must be one navyblue or forest-green shirt you could don for Yankee issues. Please?

But there is always an end time. There is always a sense that if not now, when?

In early January, our conference room filled with everyone who works here in Dublin as well as former colleagues who had left or retired. We all enjoyed some good food, and then I told them what they

had meant to me, and they told me what I had meant to them. And I am 78 but I felt like a boy as I tried, not always successfully, to choke back tears when a colleague was doing the same.

If you were in the room with us, I would have wanted you to know this: Many days I walk with several editors to a dirt path that runs past a pretty cemetery and ends at a spot where we gaze out upon lake and mountain. And each time I say, “Can you believe how lucky we are to see this where we work?”

I’d want you to know how we pulled together during the pandemic and saw one another only on a screen, and we still put together issues that made us all proud.

I’d want you to know about the time Rudy, my Jack Russell, escaped from my car in the Yankee parking lot and I was certain I’d lost him forever. But within an hour my staff had made “Lost Dog” posters, and everyone fanned out to distribute them and to look for Rudy. And late that night, as I lay in the back of my car at Yankee, hoping somehow Rudy would find his way back, my colleague Joe arrived at the parking lot. Driving once more along the darkened roads, he’d found Rudy walking along the highway and called him into the truck. Now, he held Rudy out to me.

I’d want you to know about working alongside Jud Hale, the former editor in chief whose uncle Robb Sagendorph started Yankee in 1935, and hearing him walking to his office calling hello to everyone he passed. And how Sarah, an editor with The Old Farmer’s Almanac, whose offices are just down the hall, always bakes me a chocolate zucchini bread for my birthday because she knows it’s my favorite.

I’d want you to have seen me this past New Year’s Day, alone in my office, stepping over the plastic crates I’d brought to fill

with what I had saved all these years— which seems to be nearly every manuscript, notebook, calendar, magazine, and newspaper clipping, plus enough odds and ends to fill my newly rented storage unit a few miles away. When I took down all the cards from readers and photos from my bulletin board, I remembered the boy from a long-ago summer who had the sensation of home changing right then and there, and I was glad I was alone on New Year’s in my office.

So this is the last issue of Yankee with my name at the top of the masthead. For 90 years, Yankee has evolved, always changing, because times and challenges change. But this remains: We are New England’s voice, whether in this magazine in your hands, or our Weekends with Yankee TV show, or our website and newsletters, or even our online New England Store.

Now, I will be working on a collection of my stories, and I will continue looking for new ones to write. You can find me at melallen716@gmail.com. I leave knowing that the people I have worked with for so long, who care about this region so deeply, will continue to do the work they do so well. I will always hold them close. I will still come by and join the walk on the dirt path to where lake and mountain appear. And I am certain that if I ever lose my way, they will find me and bring me home.

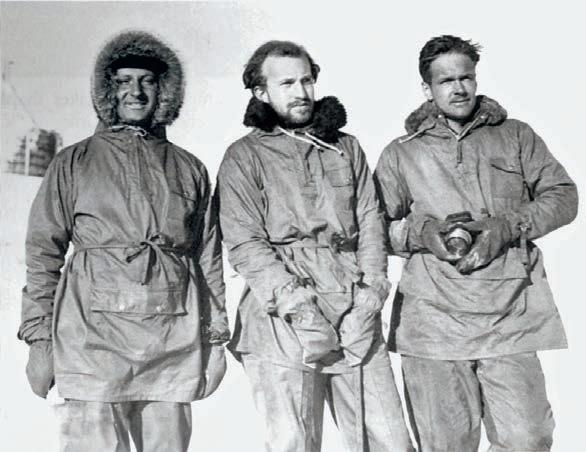

After becoming editor in chief in 2006, Mel continued to report and write stories for Yankee even as he shepherded the work of countless other storytellers— both seasoned journalists and first-time authors—into the magazine’s pages. This photo of Mel reviewing proofs for an upcoming issue is taken from a 2015 New York Times article about Yankee’s 80th anniversary (and yes, Mel’s famous Jack Russell terrier, Rudy, managed to get a mention, too).

[ COLE HAUSER × THE BARN YARD ]

AUTHENTIC POST & BEAM BARNS

Eleven generations of Sherman’s family have called Rhode Island home, creating deep New England roots that influence her work today as an independent journalist and editor. In writing about Worcester, Massachusetts [“Weekend Away,” p. 50], she was initially drawn to the city’s industrial history but was pleasantly surprised by the contemporary creative undercurrents running through its museums, music venues, and public art installations. “That its food scene is so vibrant was another perk!”

In photographing the coastal town of Stonington, Maine [“The Lobster Trap,” p. 84], Spinski was reminded that while the culture, the beauty, and the fishing economy of such a community can feel as though they’ve always existed, “it’s the hardworking folks who live there who make it possible through vision and enormous effort…. It’s a place to be treasured.” A resident of midcoast Maine, Spinski has also had his work published by The New York Times and National Geographic, among others.

Building lean-tos, damming up streams to make swimming holes, sculpting everyday objects from hand-dug clay—having done all these things as a boy in the Vermont woods, McColgan finds they have resonance in his life today [“Lessons of a Very Old House,” p. 36]. “In doing historic preservation work, which requires the use of minimally processed materials—dry-laid stone, hewn timbers, putty for glazing windows—I see an extension of the activities I loved as a kid. A more refined version, anyway.”

“I loved the opportunity to shoot really delicious recipes—since not all recipes are!” says Barboza of photographing our Weekends with Yankee food feature [“Season’s Greetings,” p. 40]. Food is a subject in which she has more than dabbled, having shot threedozen-plus cookbooks and collaborated with several food brands; she’s also a photo instructor with a focus on food photography. Barboza lives in southern Vermont, where she and her husband run Poppy Bee Surfaces, a photography supply specialist.

While no stranger to visiting Worcester, Massachusetts, on photo assignments, Campos says “Weekend Away” [p. 50] was her first chance to explore the city from a traveler’s perspective. “I hit the ground running each day because there was so much to see and do,” says Campos, a Massachusetts-based photographer whose client list includes Bon Appétit and Edible Boston. Delighted by her visits to places like the Worcester Art Museum and the EcoTarium, Campos is looking forward to returning soon

Yankee’s go-to architecture writer has not one but two bylines in our Home & Garden issue, with a deep dive into a historic masonry technique [“Rock Stars,” p. 26] and a feature on the late Russ Morash, a giant in the public television world [“Master of the House,” p. 74]. As a longtime producer on Morash’s This Old House and its sister shows, Irving found writing the latter story to be especially meaningful: “Russ was a mentor, an inspiration, and one big reason I came to love the history of New England.”

My January/February issue of Yankee magazine arrived last night, and I am mesmerized by the cover. Having grown up in Russell, Massachusetts, it was always heartwarming when I could visit a tavern that had a flickering fire to enjoy a meal and beverage. The Publick House in Sturbridge was always a favorite day trip; so was the Red Lion Inn in Stockbridge.

Since relocating to Florida almost six years ago, when I see photos like the one on your cover it takes me back to my time spent with friends at places like these. Thanks for the memories.

Lori Szepelakl Ocala, Florida

As always, the latest issue of Yankee has warmed my heart and informed me of so many wonderful New England people and places. I read Ben Hewitt’s offering [“Force of Nature,” January/ February] with a lump in my throat, as I, too, am a parent. Please pass along to him these words of wisdom from a mother and grandmother: The best and most important gifts we can give our children are love and wings. He has given his son Rye both, and father and son will survive and young Rye is sure to thrive.

Sandy Couture Brookfield, Massachusetts

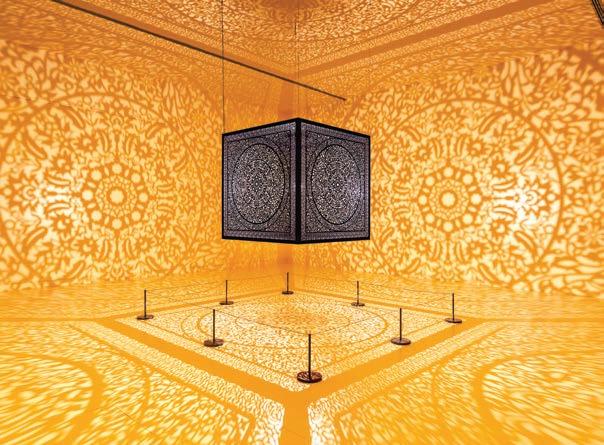

Readers of our museum-themed feature “The Great Indoors” [January/ February] had to rely on the art of deduction to puzzle out the photos for Connecticut’s Florence Griswold Museum on pages 62 and 63, as the caption was inadvertently dropped from the layout as we were going to press. To see that caption alongside images of Florence Griswold’s muralfilled dining room, Everett Warner’s Winter on the Lieutenant River, and Mark Dion’s New England Cabinet of Marine Debris (Lyme Art Colony), check out the January/February Yankee online at issuu.com/yankeemagazine

Last call has come and gone at Bullwinkle’s, the mid-mountain saloon at Sugarloaf where better skiers than me gather to sneak in cold ones before the day’s final run. I am, uncharacteristically, sticking to water, rehydrating and resting my shaky legs as my son builds tiny snowmen on the railing of the outdoor bar. It’s been a long day on the slopes.

Otis and I weren’t expecting to sneak in one last ski day. Then the weather app chimed to say that the mid-March storm dumping freezing rain on our local hill, on Maine’s midcoast, had blessed the state’s western high country with a few inches of fresh powder—just in time, wouldn’t you know, for an in-service day at the elementary school.

So I played hooky. We got up before

dawn, ate gas-station donuts, and were in line for the SuperQuad by 8:30.

Now we’re skiing up to the lip of a mildly precipitous trail called Scoot. The day’s stubborn gray skies have finally cleared, and the views of Bigelow Mountain and the Carrabassett Valley are the stuff of alpine reverie. For hours, we’ve been skiing through a pleasantly otherworldly fog, tracing line after wavy line down the sockedin cruiser trails of Sugarloaf’s West Mountain—green trails all of them, on a newly opened section billed as family-friendly.

The upper part of Scoot, however, is a blue trail: intermediate. But unlike Otis, I am not yet an intermediate skier. What’s more, the two of us can see—not 50 yards ahead and dismayingly far below—a pair of patrollers

lifting an alert but injured woman onto a litter. Otis senses my hesitation.

“Are you ready, Dada?” he asks.

At 10, he still calls me “Dada,” a habit I don’t imagine he’ll nurse much longer. I am relishing its last gasps, because I know—have spent the past decade being told, by parents of older and even grown children—that it goes by so fast. This is one of a thousand clichés about parenting that turn out to be indisputably true. Yesterday, I was taking a 5-year-old to the Snow Bowl for his first Stump Jumpers lesson. Tomorrow, he’ll be a teenager skiing black diamonds with his daredevil friends.

It took Otis learning to ski for me to finally learn. I grew up on the glacial plains of the Midwest, where the ski hills were few and forgettable. Not until my 40s, when the kiddo needed a lift buddy, did I tepidly take to downhill. Now, middle-aged beginner though I am, it’s one of my favorite things about a New England winter.

Ending our season at a megamountain like Sugarloaf feels like a milestone. For the past few years, we’ve stuck to Maine’s mom-and-pop hills, sharing T-bars and aging double chairs and dollar cocoas in the lodge. Otis, increasingly competent, was ready to level up. He isn’t fearless, but he’s brave—and patient with his dad. When I fall, he stops and asks earnestly, “Are you all right, Dada?” I don’t dismiss his concern or hide how cautiously I probe my body for the answer.

It won’t be long before I can’t keep up with him. Or, of course, before he’d rather hit the lifts with his buddies than with his old man. And so I will happily sneak in all of the one last ski days I can get.

We stare down the snaking trail in front of us, dappled with late-day sun filtering through the trees. “Do you want me to go first?” Otis asks. And I do.

“OK,” he says. “Here I go, Dada!” He leans forward, gets a good push, and lets out a small, jubilant yelp as he whizzes past me. He goes by so fast.

For New Hampshire’s Ben Fisk, a childhood dream has become a maple empire.

BY ANNIE GRAVES

n 1993, when he was 5 years old, Ben Fisk took a field trip to a sugarhouse with his Temple, New Hampshire, preschool class. It’s not hard to imagine the excitement of these little kids, taking their first deep dive into the alchemy that winds up as a delicious puddle on pancakes. And it’s easy to conjure their delight in coming in from the cold and being enveloped in clouds of moist, fragrant steam. To picture the sticky fun of sampling different grades, from light to dark; the magic of sugar on snow; the sugar high that followed. Maybe they got to take samples home. Maybe they thought a little

harder about what they were pouring onto their pancakes the next time.

What’s less predictable is obsession. Passion. Because at the age of 5, Ben Fisk could not stop talking about syrup. He’s a fifth-generation maple maker, so it was only natural that his dad knew how to make it and his grandparents had the tools to get him started. “We borrowed 13 sap buckets from my grandfather and asked the neighbor if we could tap their trees,” he says. That year he produced less than a gallon, but he admits he talked about it “nonstop.” For a Christmas present, his parents bought him an evaporator. Now he was 6.

Fisk’s genial bearded face, outdoorsy demeanor, and ready laugh belie the seeds of intensity and focus that were surely there even three decades ago. When he thinks back on what hooked

At the age of 5, Ben Fisk could not stop talking about syrup. For Christmas, his parents bought him an evaporator.

him about sugaring, he confesses, “I was so young, I don’t remember all of it, but it was probably the process.” Then he grins. “It’s an open flame! You’re getting to play with fire! The sap is coming out of trees! It was all interesting to me.”

Back then, everyone in the area knew about the whiz kid from Temple, the eventual owner and founder of Ben’s

Sugar Shack. After that first year, he tapped 200 more trees, and then kept adding. In the summer, he sold lemonade and maple syrup outside the Temple Store, in the center of this small, historic town. His dad built a sugarhouse that still sits on the family property. Someone had to drive him around to collect the sap, until he was old enough to get his own license. And still he kept adding trees. You’d read about him in the local papers, charting his growth by taps and awards, rather than years. When he was 15, he won the coveted Carlisle award from the New Hampshire Maple Producers Association for the best maple syrup in the state—and was the youngest ever to win.

He hit the big time when he launched his first website in 2003 and the Associated Press got wind of it. “They wrote this great article, everyone published it, and our website blew up,” Fisk remembers gleefully. “I had to take a few days off from school to fill the orders that came pouring in.” Which is funny, because he’d always told his teachers he was going

An adults-only haven in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom. Enjoy luxury accommodations, High Tea with pastries, Stave Puzzles, ne dining at 24 Carrot, and cocktails at the Snooty Fox Pub.

rooms, and savor tapas and cocktails at Sour’s Taverna. Explore nearby trails, bridges, and the famous Chutters candy counter.

Stay at one of the Jackson Collection inns and enjoy access to amenities at all three. A complimentary shuttle connects you to dining, pools, spas, tness centers, and more for a complete Jackson experience.

your body and mind at the Aveda Spa, or dine at 3North Restaurant.

An adults-only retreat combining elegance and warmth. Relax at the Aveda Spa, savor ne dining at Forty at Thorn Hill, or unwind with a glass of wine in the intimate Forty Below Wine Lounge.

Ideal for families and adventurers, with easy access to Black Mountain’s slopes, hiking trails, paddle boating, and rustic fare at the Shovel Handle Pub.

to sell maple syrup for a living.

I should mention that right now it’s mid-February, and we are standing in the Maple Station Market, a handsome building on Route 101 in Temple that opened in December 2023. It houses Fisk’s sugaring operation, Ben’s Sugar Shack, along with a bustling country store and deli that keeps the maple theme front and center. He bought the original 15-acre property when he was in his mid-20s, but then it took years to get to this point.

Fisk boiled this morning and made 330 gallons of syrup; he’ll boil again later this afternoon and probably make another 330 gallons. He’s got sugarbushes scattered over five different towns, over 28,000 taps, all within an hour’s drive; blue tubing snakes through the surrounding woods like rugged spider webs, delivering precious drops to collection tanks. There are five guys working the woods in November, checking the lines and

doing maintenance, and they start tapping the day after Christmas. It is literally his dream come true.

The waxing light of February feels like a New England miracle when it finally comes. By March, it’s incontrovertible, a fact. There are no dog days of winter, but if there were, they might be now, when we’re crawling toward spring. It’s all about the light, and change, and sap is a gravity-defying proof of this metamorphosis. Syrup feels like boiled light. We may be able to explain it scientifically, but it’s still one of earth’s happy mysteries. Why does it taste so good?

In the end, Fisk tells me, it’s about weather. If the 10-day forecast stays like this for the rest of the month, it will be a terrible season, he says. You have to have nights below freezing and days around 40 to 50 degrees. If all goes well, it’ll take 40 to 60 gallons of sap to make one gallon of syrup—that’s according to the signs handily posted

along Fisk’s popular maple tours. A tree can produce more than a gallon of sap a day, there’s another tidbit. Ben Fisk knows as much as anyone about this ebb and flow.

He tells me he’s excited every day when he gets up. Sure, maple syrup may be the stuff of kids’ dreams, but it’s more than that, too. In the end, for him, it’s about being out in the woods.

“You’re out there by yourself listening to the birds and the trees, looking at different things. The earth always grows in different ways. And you’re trying to figure out how to bring the sap out of the tree, this tiny drop of maple sap.”

It’s a unique job, he admits. The tree produces this one drop. And then Ben Fisk brings it home. bensmaplesyrup.com

Step back in time with a visit to Plymouth, Massachusetts. The past comes to life in this coastal community, where beautifully preserved historical homes tell the story of America’s settlers. Learn about architecture, art, period design and the people who lived here. Whether you’re a history enthusiast or a curious traveler, unexpected stories await you.

Discover the Secrets of the Massachusetts South Shore.

Park’s eye-catching reminder of Ted Williams’s record-setting home run.

actually touch a ball.

s a lifelong Boston sports fan, I’ve sat in my share of unforgettable stadium seats. Fenway Park’s Field Box 81, Row C, Seat 1—along the oddball juncture of the left-field wall and third-base line—might be my favorite, since it makes me feel I could seat in Boston sports, which is distinguished among Fenway Park’s forest of green bleacher seats by its flash of Red Sox red. Located 502 feet from home plate, the “Ted Wil-

But I’ve never sat in the of feet liams seat”—Section 42, Row 37, Seat 21—was painted red in 1984 to memorialize the mighty bomb that Williams launched on June 9, 1946, still the longest home run at Fenway.

We don’t have to guess where that first-inning homer landed, because it thunked off the noggin of ticket holder Joseph Boucher. published a photo the next day showing the hole the ball had made in Boucher’s fine straw boater, and quoted the exasperated Fenway first-timer saying, “How far away must one sit to be safe in

He’s not alone in thinking that. Some are skeptical that Williams’s travel 502 feet, and even Red Sox home run bashers like Mo Vaughn and Big Papi have expressed doubt. (It’s said that Big Papi tried to hit the seat in batting practice using an aluminum bat—to

The Boston Globe ball this park?”

Today, many fans make pilgrimages to the Ted Williams seat, both with tickets and without. My friend John, a season ticket holder with seats elsewhere in the park, went through the turnstiles extra-early one game to sit in the fabled chair. His first thought, he says, was, the hell did he hit it this far?!

How ball actually did aluminum no avail.)

Last year an MLB stats analyst named Mike Petriello published an exhaustive report that evaluated launch angles, exit velocity, and jet stream behavior before and after the Fenway Park redesign. In 1946, winds of 20-plus mph were blowing to right field. His judgment? Not only was the distance possible, but Teddy Ballgame probably hit it even

farther. —Todd Balf

How a 19th-century masonry technique from Scotland created a treasure trove of rare buildings in Vermont.

BY BRUCE IRVING

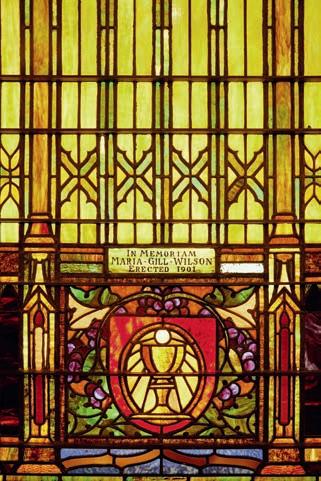

An exterior detail of the Stone Church, officially known as the First Universalist Parish of Chester, Vermont. Built in 1845, it shows how masons fit together irregularly shaped stones with the help of smaller pieces called “snecks.”

hen it comes to building houses, you don’t have to be a little pig or a big wolf to know that wood beats straw and brick beats wood. But for the lucky folks of Chester, Vermont, there’s something even better than brick: stone. The town is home to a unique collection of snecked ashlar buildings, whose aesthetic qualities elevate them beyond simply being well-built and strong and into the realm of folk art. Composing the Stone Village Historic District, 10 of them line Route 103, known locally as North Street, with another 40 or more scattered throughout the surrounding area of south-central Vermont.

First, some definitions. “Ashlar” is cut and dressed stone, and it makes sense that the word comes down from the medieval Latin arsella , meaning a little board or shingle, since ashlar

stones are usually laid up in horizontal bands. “Snecked” is a bit funkier, if Scottish dialect can bring the funk. In Scotland, a sneck is a latch or small bolt used to secure a door. In a snecked ashlar wall, relatively thin stones of different sizes make up the exterior surface pattern. The smallest ones—the snecks—serve both to fill in the gaps left by the bigger ones and, crucially, to penetrate through to an interior rubble wall, not unlike a series of bolts, acting the way metal ties do in a modern brick veneer wall.

But what, pray tell, is a Scottish word doing in Vermont? Like so many American things, the word and the building technique it describes came in thanks to immigration. Snecked ashlar construction is common in Scotland and the border lands with England, where tough weather and a relative lack of trees make it a natural choice. Scottish masons first arrived in Canada in the early 1800s, bringing their skills to bear on forts and canals, where

ABOVE LEFT: Possibly the most unusual Stone Village home is the converted one-room schoolhouse where Joanne and Mike Young reside. Joanne actually attended the school in the 1950s, and the frame on this side table displays portraits of both a young Joanne and her teacher, Idamae Laitinen.

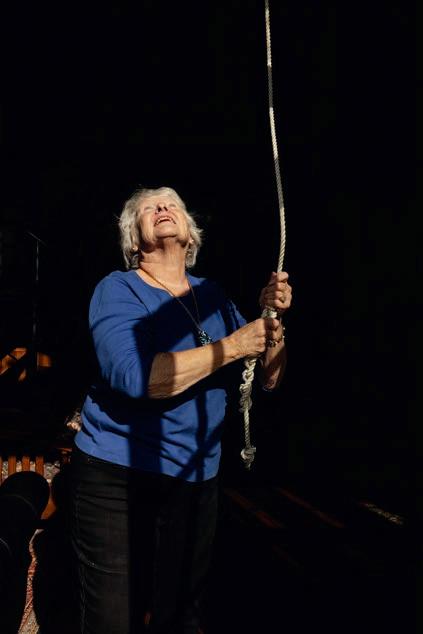

ABOVE RIGHT: As a child, Joanne always dreamed of ringing the schoolhouse bell—and today she can ring it whenever she likes.

stone outdid wood. In the early 1830s, some of them were hired to build a large stone factory in Cavendish, Vermont, just north of Chester.

Word must have spread quickly, because in 1834, Dr. Ptolemy Edson, a forward-minded leading figure in Chester, hired local brothers Addison and Wiley Clark to build him a Federal-style home using the new (to the Vermonters) technique. The brothers, part of a family with Scottish roots that had been in Vermont since the 1700s, likely learned snecked ashlar construction from their overseas kinsmen, possibly even on the Cavendish job. It’s been said that Edson paid each of his masons $5 a week, along with a gallon of good rum.

It’s not known whether Edson was taken by the technique’s novelty, its looks, its snugness

against the huff-and-puff of Vermont winters, or something else, but he became a snecked ashlar booster to his neighbors. Addison and Wiley Clark—joined by a third brother, Orrison, as well as Arvin Earle and other colleagues—built stone buildings at about a one-ayear clip for the next decade, lining a half-mile stretch of North Street with Federal and Greek Revival residences, a one-room schoolhouse, and the village’s centerpiece, the First Universalist Church of 1845, which seats 300.

The Clarks surely must have appreciated the economic advantage of a building material that was literally underfoot and more or less free for the taking. Nearby Mount Flamstead, where they lived, is rich with gneiss and schist, metamorphic stone that splits relatively easily into angular pieces, better for facing a building than for wall-building. They and their farmer neighbors took it from the surface or from shallow quarries, harvesting it off-season and transporting it over the snow by sled in preparation for the summer construction season.

Modern renditions of snecked masonry adhere to a strict protocol using three sizes of stone. The Scottish master stonemason Bobby Watt describes them as “jumpers” or “risers”

you expect and so much more. 17 inspiring showrooms in New England With thousands of products from Kohler, House of Rohl, BainUltra and many other world-class brands, our showroom associates will help you find the perfect selections for your home.

Another view of the First Universalist Parish of Chester. Originally, the first floor was used for worship, while the basement held the town offices. (It’s been noted that church and state were kept separate thanks to the lack of an interior staircase joining the two levels.) Along with the rest of the buildings in the Stone Village, the church was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

(square, or almost square, or up to three times as long as they are high); “levelers” (usually at least twice as long and up to five times as long as they are high); and “snecks”(smaller pieces that enable the mason to make up the differential in height between the top surfaces of the levelers and the risers). Laid up horizontally, the different-height stones key the rows together to make a strong wall.

The work of the Clarks and their friends is far looser and free—and sometimes downright exuberant, with huge risers surrounded by a bevy of attendant levelers and snecks, a pair of triangular stones kissing to form a vertical bow tie, and parallelogram levelers interlocking in a line. Everywhere is the interplay of the stones’ color and texture, with glimmers of mica across every facade. You can almost hear the delight of the crew as they grabbed the perfect next stone from the various piles they’d assembled. (Maybe the rum helped.)

Holding it all together was the mortar, apparently a secret recipe. Some reports have

it containing moss; others describe slaking the lime slowly over fires of green wood. Whatever the trick, it worked, as most is still sticking strong after nearly two centuries. When the exterior walls were complete, carpenters moved in to hang timber joists from wall pockets in the interior. Walls were furred out, providing some insulative air space, and lath and plaster made for smoothly finished rooms befitting a prosperous town such as Chester.

Like ardent art enthusiasts, today’s residents cherish and celebrate their pieces of folk sculpture. Nicholas Boke, former minister of the First Universalist Parish, happily shows the spot in the side pews where a farmhand used to lean his freshly bear-greased head against the stone wall. A square piece of wallpaper would be put up to cover the stain, only to be quickly soaked through. It took a full renovation to conquer the problem.

In 2019, Joanne Young and her husband, Mike, moved into the belfried schoolhouse at 186 North Street that she had attended back in the 1950s, converted to a home by a previous owner and complete with the 48-star flag she pledged allegiance to as a first-grader. Just across the street, at 189, Polly and Ian Montgomery have restored the Gideon Lee House into a five-star Airbnb outfitted with solar panels and Tesla batteries.

And at 146 North Street, Jon Clark, president of the Chester Historical Society, shows off the room where the original owner once sold sheepskin boots and moccasins he made on-site, his sheep on the hillside behind the house. The 14-stone arch over the front door commemorates Vermont’s place in the Union.

“I love the Stone Village,” Clark says. “And my next project is to finally figure out if I’m related to the guys who built it.”

Exploring on foot: Walking-tour brochures created by Chester Townscape, a committee of the Chester Community Alliance, can be found at many locations around town as well as by going to: chestervt.gov

Staying overnight: The writer and the photographer for this story each stayed in a historic stone building in Chester: the Gideon Lee House and the Cairn of Vermont cottage, both of which can be found at airbnb.com.

In the home or in the garden, the whimsical creations of D. Lasser Ceramics lend a jolt of color.

BY BILL SCHELLER

BAmong D. Lasser Ceramics’ newest offerings are these “baby bowls,” sized a bit smaller and taller than dinner bowls and offered in all 48 of Lasser’s vibrant glaze patterns.

lues like the deep sea, greens like the shallows. Dinner plates done in explosively imaginative designs you’d almost hate to hide with food. Vases prettier than the flowers they’re made for.

The pottery at D. Lasser Ceramics in Londonderry, Vermont, ranges from functional to purely decorative, from a full line of tableware to outdoor sculptural ceramics and even glazed garden orbs that make glass glazing balls look staid and old-fashioned. And through it all, color with a generous dollop of whimsy reigns.

“My personality is playful,” says founder Daniel Lasser, “and my personality is all over these things. You’re going to get a playful product.”

Every piece sold at D. Lasser Ceramics is made on the premises. The showroom fronts a workspace dominated by two enormous kilns, one for firing and the other for glazing, and displays of finished work spill out across the lawns. Situated on a gently rolling hillside, it’s an impossible place to miss on a drive along Route 100.

It’s surprising to learn that Lasser, 63, has been making ceramics for more than 50 years—but he got a grade school start. “When I was 11, an art teacher brought in a wheel one day so the class could try it out,” he recalls. “I never looked back. From then on, I knew just what I wanted to be.” He’s proud to show two cups he made back when he was that boy, and both look as if they’d find buyers in no time at all.

Lasser studied ceramics at Alfred University, home of the New York State College of Ceramics, and he went into the business soon after graduating. Although he’s a veteran of the trade show circuit and formerly sold at several outlets, he’s sold his work exclusively at the Londonderry location and via his own website for the past 20 years. “I used to make things with a commercial purpose, repeating designs that were geared to sales,” he says. “But I wasn’t really in it; it was just copying. I went back to being myself.”

For Lasser, that means being focused on all the possibilities of color and on the pigments that potters use to achieve them. “My work is defined by an exploration with color,” he says. “It’s all about the chemistry, exploring what the colors can do. It’s like playing in your backyard—with a purpose.”

D. Lasser Ceramics isn’t a oneman shop. “There are usually four or five [artisans] working here, sometimes more,” he explains, “but they’re not necessarily trained in ceramics.” Lasser does the training, and all of the

shop’s artisans work from his designs and color schemes.

The shop’s bestsellers are mugs and dinnerware. Pottery meant for outdoors might be second, including purpose-made large sculptural pieces—maybe even a fountain—sure to add a vibrant touch to patios or garden borders and backdrops. Decorative platters 24 inches across, too large for any but a baronial dining room, are perfect for wall mounting in a sunroom or along a piazza.

Lasser’s customers are as playful as he is. “People mix and match,” he says. “We seldom see them buying whole

ABOVE LEFT: Almost any day of the week at D. Lasser Ceramics, visitors can see founder Daniel Lasser busy at his wheel. While he creates his collection with a team of artisans, it’s still his hand that shapes most of the larger pieces.

ABOVE RIGHT: Lasser’s showroom extends outdoors to include displays of dramatic garden accents such as these pedestal planters in Sand Dollar, Blue Moon, Ocean, and Teal glaze patterns.

dinner sets with each place setting in the same pattern and colors—they buy different patterns, in different colors, and mix them up.” It’s easy to imagine a Lasser-enhanced dinner party, with guests taking seats where the table settings most intrigue them.

It’s just as easy to suppose there are households bursting with enough Lasser ceramics to host dinners for dozens. “We meet people in the shop who tell us they’ve been buying our work for years,” Lasser says. “We’ve been here long enough that by now we have second-generation customers.”

On any given Saturday or Sunday

at D. Lasser Ceramics, the number of browsers and buyers usually runs to a hundred or more. And if they miss the weekend, there’s almost every other day in the year: The business closes on just three holidays—Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter, all days when countless feasts might boast a certain special splash of D. Lasser flair.

Looking back on his love affair with clay and color that dates to that day in grade school, Lasser sums up what has mattered most in his career: “My favorite thing here is sitting at the wheel. I’m a potter by nature.” lasserceramics.com

Five more New England artisans to whet pottery lovers’ appetite.

Lucy Fagella | Greenfield, MA

The bucolic surroundings of Fagella’s studio—a popular stop on the Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail, which she helped found—are reflected in her line of mugs, lidded urns, and vases decorated in flowers and leaves that seem to live on the surface of the clay. lucyfagella.com

Salmon Falls Stoneware | Dover, NH

For nearly 40 years, Salmon Falls has been turning out the kinds of classic salt-glazed pieces with hand-drawn patterns that have long been staples of the farmhouse kitchen. At the heart of the collection are ovenware and place settings, but you’ll also find lamps, vases, planters, and even birdbaths. salmonfalls.com

Sheepscot River Pottery | Edgecomb, ME

Sheepscot’s artisans create pottery that could come only from Maine. Lobsters, pine trees, loons, and coastal scenes adorn dinnerware, mugs, and, of course, chowder bowls. Even in non-pictorial pieces, the colors of sea and forest are pure Down East. Satellite locations in Damariscotta and Portland; sheepscotriverpottery.com

Tim Scull Ceramic Studio | Canton, CT

Scull’s work reflects the remarkable variety of glazes and surface textures that traditional wood-fired kilns can produce. A specialty is raku-fired pottery, made using Japanese fastfiring, fast-cooling techniques that create signature crackled glazes. cantonclayworks.com

Pottery Wheel | North Kingstown, RI

Elegantly simple designs and soft, harmonious colors characterize the stoneware by potter Mike Chatterley. His collection honors function as well as form, featuring practical pieces such as casserole dishes, soup crocks, chips-and-dip platters, and a clever corkless salt shaker. Visit by appointment, or shop at the nearby Honey Gallery. potterywheelri.com

In understanding my three-century-old Colonial, I also came to understand a little more about my place in the world today.

BY LEE MCCOLGAN

One summer day my car rolled down a winding road that followed the waves of the Atlantic in the town of Duxbury, on the South Shore of Massachusetts. Tossed stone walls rambled along windswept hills. Behind the walls stood solemn rows of wooden houses, their simple rectangular elevations backlit by the sun. Battered by salt air, weathered shingles had turned from the blond of fresh-cut cedar to a silvery gray, that way that locks of hair change color with time. The jumble of a construction site encroached upon one of the homes, a fine example of early American architecture. In front of it, leaning against a telephone pole, lay a stack of old windows. Beside them, scratched crudely on a torn piece of cardboard, bold black letters proclaimed “FREE.”

The wood from these antique window frames had come from old-growth forests. Tightly clustered together, the trees had grown slowly, competing for water, nutrients, and sunlight. That struggle made the wood dense, less prone to rot than trees that shoot up quickly from clear-cut ground, as in

In 2017, Lee McColgan (RIGHT) left a career in finance to learn how to preserve historic homes and buildings, starting with his own 1702 Colonial in Pembroke, Massachusetts. The home’s original details—such as its painted staircase (LEFT) and seven fireplaces, including this hearth with Georgianstyle paneling (TOP RIGHT)—had been left virtually untouched over the course of its long life.

A joiner had planed the profile on the muntin bars, the thin strips of wood that form the grill within the window frame. Sleek and curvy, the plane iron itself mirrored the pattern that it left in its wake. Then the joiner fit the pieces together with mortiseand-tenon joints. Through a long hollow tube, a glassmaker had blown molten silica and spun it on a gaffer’s chair, like a throne, until the glass spread into a large disc. Its finished surface rippled

with tiny grooves like a vinyl record. He cut the disc into small rectangular panes. From powdery chalk dust and cold-pressed linseed oil, a glazier mixed a doughy putty. He sliced a pristine bevel of it around each pane, securing the glass in place.

When properly maintained, these windows lasted for centuries. Knowing all the skilled work that had gone into them made leaving them on the side of the road anathema to me. To abandon them, like so much fly-swarming garbage, felt wrong. I pulled over and loaded them all into my car.

I understood the skills required, could count the hours of labor, because I’d learned to do what those long-gone workmen had done. My own house had taught me. Fortune had brought me into possession of a three-centuryold Colonial that needed restoration. Hewing as closely as possible to 18th-century building techniques had taught me arduous lessons. But within them, hidden like a secret room, lay a deeper lesson. In understanding my

house, I came to understand a little more about my place in the world.

It began with a book. Large and rectangular itself, The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625–1725 by Abbott Lowell Cummings has a bright red cover like that of a children’s storybook. Given to me as a gift, it thoughtfully catalogs a handful of the earliest surviving houses in the Bay State, detailing exteriors and interiors, floor plans and framing. An entire chapter describes the builders and their resources. It immediately drew me in and compelled me to seek out these structures, one by one.

Most of the houses had survived and were operating as museums. My original interest focused on timber framing. As tour guides spoke about generations of occupants, my eyes fixed on the large beams that ran overhead, studying, analyzing, piecing together how the craftsmen had fashioned and assembled them. Months of poking around these ancient treasures convinced me that I wanted one of my own.

In 2017, real estate listings led me to the Loring House. Built in 1702 in what would become Pembroke, Massachusetts, it stood frozen in time. Most Colonials on the market have endured numerous remodeling jobs over the centuries, but not the Loring House. It felt like digging up a house-size time capsule buried deep in the earth.

The house clearly needed work, though, and I needed to figure out how to do it. In my research, an account of an 18th-century master builder named Richard Macy that I’d stumbled across in Nathaniel Philbrick’s book Away Off Shore provided my path. A passage in the book recounts Macy’s grandson writing: His practice was to bargain, to build a house, and finish it in every part, and find the materials. The boards and bricks he bought. The stones he collected on the common land, if they were rocks he would split them. The lime he made by burning shells. The timber he cut here on island. The latter part of his building, when timber was not so easily procured of the right dimensions, he went off-island and felled the trees and hewed the timber to the proper dimensions. The principal part of the frames were of large oak timber, some of which may be seen at the present day. The iron work, the nails excepted, he generally wrought with his own hands. Thus being prepared, he built the house mostly himself.

Builders—some skilled, some unskilled, some free, some indentured—lived hard lives. They toiled, raised families, and died in comparative obscurity, most now forgotten. But the simplicity of what they did appealed to me. A dozen basic hand tools could do most of the work. Richard Macy captured my imagination, and the decision came almost immediately: Following in those footsteps, I would restore the Loring House myself using period methods and materials. How hard could it be?

Like a mad scientist, I found out. I stumbled through acquiring tools and sourcing supplies. I tracked down living builders using traditional techniques

to learn the tricks of their trades. I performed my own sometimes demented experiments with the materials to encourage them to yield to my demands. Through it all, house museums continued guiding the way. The more I learned, the more those relics revealed. After a summer working with a traditional plasterer, I saw anew the rich textures and details of walls and ceilings. In sections abutting wood or brickwork, where the plaster was crumbling, tufts of fur sprang from the chalky white material like coastal sea grass.

Blacksmiths had forged the iron hardware of latches, hinges, and door handles, heating them until they glowed orange and bent to their will like clay. Hammer blows flattened and fanned the metal into simple shapes—circles, triangles, rectangles, spades—that they finished with delicate file work. Where they had welded two pieces together, subtle lines called “peen marks” remained evident.

Swinging too close to the ground, my broadax once caught a small rock, nicking the blade. As it sliced through

the fibrous cellulose of new wood, that nick left a small track in its wake, a tiny arch like a rainbow. The old wood in some of the house museums revealed similar marks. “That carpenter’s ax had a small nick in it,” I announced to no one in particular. Macy deserved far more credit for what he had done.

But as the restoration progressed, a simple question pulled at me. Why did it matter? Saving an old house doesn’t save lives. On a long-enough timeline, I will go, and so will the structure. Finding an answer to that deceptively straightforward question felt like trying to dislodge a splinter from my brain.

Our possessions reflect us. I began to understand what my house said about me. Living in an untouched three-century-old house was not ordinary, and this spoke to my eccentric nature. Working with minimally processed materials—wood, lime, stone, iron, glass, brick—held an allure, too. These materials live in better harmony with the natural world than most modern building supplies, full of petrochemicals and plastics that destroy untouched landscapes and eventually gorge landfills. On my watch, the Loring House would age with grace, but even when it finally crumbles beyond repair, its materials can return to the earth with a calm magnanimity. In its way, the house itself had become an environmentalist, too.

In the meantime, the work grounded me, made me happy. Our relationship, the house’s and mine, became symbiotic. It provided shelter for my family and me, and my efforts kept it standing and functioning as intended. In it, so many of the people in my life had converged. The hardships and triumphs of the restoration eventually made it clear that the work was less about the building itself than about all the people whom it had protected. It always had been. Beneath an old, weathered roof, we told new stories and made new memories to fill our own lives and others’. What better to do with our time than that?

Our food-forward preview of Weekends with Yankee season 9, premiering on public television stations this spring.

BY AMY TRAVERSO | PHOTOS BY CLARE BARBOZA | STYLING BY GRETCHEN RUDE

n early July, I was rowing a dory in Maine’s Belfast Harbor with Nicolle Littrell just as the bright disk of the sun began to penetrate the upper layers of fog.

As we reached the outer harbor, Nicolle, a Registered Maine Guide who leads excursions through her company DoryWoman Rowing, pulled out a thermos of tea and fluffy biscuits seasoned with finely chopped seaweed. While we snacked, a harbor seal swam over to say hello. If mermaids or selkies were real, that would’ve been my cue to roll overboard and find my pod. Instead, we picked up our oars and made sure the camera crew in the chase boat had gotten enough good shots of the moment that everyone watching Weekends with Yankee, the public television show we produce with WGBH, could enjoy it, too.

The ninth season of the show, which premieres in early April and rolls out over the course of 13 weeks, is full of memorable moments like that one. We comb Connecticut’s coastline with chef and forager Chrissy Tracey as she sources a meal from the small miracles growing all around her. At Newport’s Castle Hill Inn, we enjoy a lobster bake on top of a bluff so gorgeously lit by nature’s golden hour you might think our camera crew used filters. We meet the Old Ladies Against Underwater Garbage, who patrol nearly 1,000 ponds on Cape Cod to clean these beloved waters with humor and spirit. We experience the beauty of a New Hampshire lavender farm in full flower, a cozy afternoon on a Maine houseboat, a bike trip to find the best fried clams on Boston’s North Shore, and a maple farm in Vermont where a “happy” (aka group) of golden retrievers welcomes guests for playtime and snuggles. And we visit Mashpee Wampanoag tribal lands in Massachusetts to cook squash stew in

a traditional hut called a wetu with James Beard Award–winning chef Sherry Pocknett.

It’s our best season yet, and we hope you’ll tune in. In the meantime, here are five recipes that we prepare on the show, along with the stories that inspired them. To find all the recipes from our new season, go to newengland.com/ season-nine-recipes.

After decades spent in restaurant kitchens, Sherry Pocknett came to national

attention when she won the 2023 James Beard Award for the Northeast’s best chef. Her food reflects both Wampanoag and European influences, emphasizing the former, and we were honored to cook with her in the Mashpee, Massachusetts, wetu where her tribe still conducts official business. You can visit her restaurant, Sly Fox Den Too (it’s named after her father, tribal leader Vernon “Sly Fox” Pocknett), in Charlestown, Rhode Island—but until then, here’s a recipe to make at home.

The method Sherry used (“the Wampanoag way,” she called it) was new

to me. By long-simmering the squash until the cooking water was reduced by about half, you end up with a very concentrated squash-enriched base; from there, you incorporate additional flavors. As much as possible, Sherry uses ingredients indigenous to the Northeast, like sunflower oil instead of butter. While shallots are not native to this region, they are far easier to source than wild onions. The cream is optional (but delicious). Note: Sherry uses all kinds of cranberries in this soup—fresh, dried, sweetened, unsweetened. You can choose any type, or go for a combination.

2 large butternut squash, peeled, seeded, and cut into medium chunks

3 tablespoons sunflower oil

2 large shallots

1 teaspoon plus 2 teaspoons kosher salt

1½ teaspoons fresh thyme leaves or chopped fresh sage

²⁄ 3 cup dried or fresh cranberries, sweetened or unsweetened

1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

3–4 cups chicken or vegetable stock, or water

3 tablespoons heavy cream (optional)

Sunflower oil, cream, pepitas, and flaky sea salt, for garnish

Put the squash in a large soup pot and cover with water. Set the pot over high heat, cover, and bring to a boil. Remove cover and reduce heat to an active simmer. Continue simmering until the squash is very tender and the water is reduced by half, which will take anywhere from 30 to 45 minutes, depending on the size and shape of your pot.

Want to know where to watch the brand-new season of Weekends with Yankee? Go to weekendswithyankee.com, where you’ll also find full episodes from past seasons and 200-plus snackable segments—many of which are available @yankeemagazine on YouTube, too.

Meanwhile, in a small skillet, heat the sunflower oil over medium heat. Add the shallots and 1 teaspoon salt and sauté, stirring often, until translucent, about 5 minutes. Add the thyme or sage, and sauté briefly.

Roughly mash the cooked squash and add the shallot mixture and cranberries to the pot. Add the remaining 2 teaspoons salt and the pepper, then add 3 cups of the stock or water and stir. Use an immersion or standing blender to puree the mixture until very smooth (if using a standing blender, you’ll need to do this in batches). If the soup is still too thick, add more stock or water until you get the texture you like. Add heavy cream (if using) to taste. Taste and add salt if needed. Serve hot, garnished with a drizzle of sunflower oil and/or cream, some pepitas, and a pinch of flaky sea salt. Yields 8 to 10 servings.

After a morning of rowing in Belfast, I headed to one of the town’s newest and best restaurants: Dos Gatos Gastropub, where tequila and mezcal reign supreme and where the tacos are inspired by co-owner Jesse Soto’s memories of growing up in Texas. Using modern Tex-Mex as a culinary framework, chef Gary Cooper works wonders in dishes like this one: scallop tacos topped with crunchy pico de gallo flavored with cucumber, lime, tomatillo, and cilantro. We recommend using natural or “dry” sea scallops, which

are not treated with phosphates and have a pale tan color. These not only taste better, but also let you achieve that delicious caramelized crust. The recipe also works beautifully with sautéed shrimp and seared salmon.

Note: The chili pepper known as aji amarillo is a foundational ingredient in Peruvian cooking. Look for the jarred puree (as well as the Tajín seasoning) in the Latin American section of your supermarket, or use a chili sauce of your choosing.

FOR THE PICO DE GALLO

2 limes

1 European (seedless) cucumber, finely diced

1 small red onion, finely diced

1 large jalapeño, seeded and finely diced

1 tomatillo, finely diced

¹⁄

3 cup minced cilantro

½ teaspoon ground cumin

1½ teaspoons Tajín seasoning, plus more for sprinkling

Heavy pinch of kosher salt

FOR THE AIOLI

1–2 tablespoons aji amarillo puree

½ cup mayonnaise

FOR THE TACOS

1¼ pounds natural sea scallops

Salt and freshly ground black pepper, to taste

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

12 taco-size corn or flour tortillas

First, make the pico de gallo: Zest and juice one of the limes into a medium bowl. Using a knife and working from top to bottom, carefully cut the peel off of the second lime, then cut the flesh segments out, leaving the membranes behind. Chop the lime segments and add to the bowl. Add the cucumber, onion, jalapeño, tomatillo, cilantro, cumin, and Tajín seasoning. Check flavor, then add salt to taste. Set aside.

Next, make the aioli: Stir the aji amarillo puree into the mayonnaise until evenly combined. Then, make the tacos: Dry the scal-

lops with paper towels, then lightly sprinkle one side with a bit of salt and pepper. Set a medium pan on high heat to warm up, then add the oil and heat until shimmery. Swirl the pan to coat, then place half the scallops into the pan. Cook without moving them until you see the edges turn brown, 2 to 3 minutes. Reduce the heat to low, flip the scallops, and cook until just done at the center, 1 to 2 minutes more. Let the scallops rest on paper towels while you cook the second batch.

To assemble the tacos, slice the cooked scallops in half crosswise. Fill each tortilla with a few scallop slices, then top with pico de gallo, a drizzle of the aioli, and a sprinkle of the Tajín seasoning. Serve warm. Yields 12 tacos.

We spent a sunny day with chef Michael Serpa biking along the coast of Ipswich

(Continued on p. 98)

Two recipes that celebrate maple syrup, including one my friends rank among the tastiest things I’ve ever made.

BY AMY TRAVERSO

STYLED AND PHOTOGRAPHED BY LIZ NEILY

n his 1923 poem “Maple,” Robert Frost wrote of “when the maples / stood uniform in buckets, and the steam / of sap and snow rolled off the sugarhouse.” It takes you right there, doesn’t it? I like to think of the maples as uniformed in buckets, a thicket of worker trees in full production mode. Twenty years ago when I lived in New Hampshire, I drove around the bend of Highway 101 one late winter day and was confronted with a sugar shack in full boil, fresh clouds of steam roiling out of the cupola and into the bluebird sky. It still remains my reference point for a perfect March day.

To celebrate the return of this glorious season, here are two recipes. The first is a sweet-savory all-in-one dinner of maple-glazed sweet potatoes stuffed with chorizo and spinach and topped with a dollop of maple-sweetened sour cream. When I served the rustic dish to two friends, each told me separately it was one of their favorite things I’d ever made for them. Take that as your invitation to give it a try.

The second recipe is inspired by our neighbors to the north, the Québécois, who celebrate le temps des sucres with an enthusiasm that puts even New England to shame. Entire families gather around giant picnic tables at sugar shacks and eat multicourse meals of ribsticking fare doused in syrup. If you’ve never visited the region in March or April (or sometimes early May), here’s your invitation to try that, too.

You can use orange, red, or white (Japanese) sweet potatoes here. What’s most important is that they be wide enough to stuff—think of the size being somewhere between a soda can and a one-pint mason jar.

1 tablespoon plus 3 tablespoons olive oil, plus more for the baking sheet

3 large chunky sweet potatoes, sliced in half lengthwise

1 tablespoon plus 3 tablespoons maple syrup (any grade)

1 cup sour cream

1 pound chorizo sausage (pork, chicken, or vegan), removed from casing

10 ounces fresh baby spinach

1 large garlic clove, very thinly sliced

½ teaspoon kosher salt

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

Cilantro and thinly sliced scallions, for garnish

Preheat your oven to 400°F and set a rack to the middle position. Generously grease a large rimmed baking sheet with olive oil. Lay the potatoes cut side down and slide them around in the oil to prevent sticking. Roast until fully cooked and tender when pierced with a sharp knife, 40 to 50 minutes.

Meanwhile, in a small bowl, stir 1 tablespoon maple syrup into the sour cream. Cover and refrigerate.

Next, set a medium skillet over medium heat until hot. Add 1 tablespoon oil, then the chorizo, using a spatula to press it into a large patty. Cook, without stirring, until browned on one side, 3 to 4 minutes. Flip the patty, then use a wooden spoon to break the chorizo into small pieces and continue to cook

until there are no raw pieces left.

In a large skillet over medium heat, warm the remaining 3 tablespoons oil. Add the spinach and garlic, then use tongs to turn the leaves over in bunches until they begin to soften. Add salt and pepper, stir, then reduce heat to low and cover. When the spinach is all wilted, remove it from heat and set aside.

When the potatoes are done roasting, turn them over with tongs. Scoop out just enough of the potato flesh to create a small well in the center of each potato half. Brush each potato generously with the remaining 3 tablespoons maple syrup. Fill the wells with equal portions of spinach and then the chorizo. Top each potato with a dollop of maple sour cream, cilantro, and sliced scallions. Yields 6 servings.

This Depression-era dessert (whose name roughly translates as “poor man’s pudding”) is a type of upside-down cake that yields two layers: one cake, one sauce. The toasted walnuts are optional, but I love how they balance the cake’s sweetness.

1 cup maple syrup (any grade)

1 cup heavy cream

½ teaspoon plus ½ teaspoon kosher salt

²⁄ 3 cup salted butter, softened, plus more for greasing ramekins

¾ cup granulated sugar

2 large eggs, at room temperature

1½ cups (210 grams) all-purpose flour

1½ teaspoons baking powder

1 teaspoon ground cardamom (optional)

½ cup milk

½ cup chopped walnut halves Whipped cream, for garnish

Preheat your oven to 350°F and set a rack to the middle position. Grease 8 ramekins with butter and arrange them on a rimmed baking sheet. Set aside. First, make the sauce: Put the maple syrup, cream, and ½ teaspoon salt in a medium saucepan over medium-high heat. Bring to a boil, then remove from heat. Set aside ⅓ cup sauce in a small bowl. Divide the remaining sauce evenly among the 8 ramekins.

Next, make the dough: Using a stand or handheld mixer, beat the butter and sugar on high speed until fluffy, about 3 minutes, scraping down the sides of the bowl halfway through. Add the eggs, one at a time, beating well and scraping down the bowl after each.

In a medium bowl, whisk together the flour, baking powder, ½ teaspoon salt, and cardamom (if using). Add the dry ingredients to the wet and beat on low speed until blended. Scrape down the sides of the bowl. Add the milk and beat on low until evenly combined.

Divide the dough evenly among the prepared ramekins and transfer the baking sheet to the oven. Spread the chopped walnuts in a single layer on a small baking sheet or pan and put it in the oven. Toast the walnuts until golden brown, about 5 minutes, then remove. Bake the cakes until they are browned on top and puffed in the center, 20 to 25 minutes total. Let cool for 20 minutes. Serve warm with a dollop of whipped cream, a drizzle of the reserved sauce, and a sprinkle of toasted walnuts. Yields 8 servings.

In Central Florida, you hold the keys to unexpected vacation memories.

There’s your luggage, already on the carousel. There’s your rental car, right outside the door. Lakeland Linder International has just two gates, so when you land at Central Florida’s airport—a competitively priced direct flight of about three hours from New Haven or Manchester-Boston thanks to new Avelo routes—you won’t waste precious vacation time getting on your way.

On your way to Tampa or Orlando, perhaps. Both are about an hour’s drive. But that would be

soooo predictable. And you and your beloveds deserve a trip that’s uniquely unforgettable and as easybreezy as jetting to this land of citrus and sunshine and Old Florida allure. Which of these worlds will you explore together on your first visit … and on your next?

A Garden of Musical Enchantment

By March, it’s full-on springtime at Bok Tower Gardens in Lake Wales, as thousands of azaleas and camellias erupt in magentaand-white bloom blasts. On

this perpetually colorful hilltop, wildscapes converge with cultivated landscapes in what is considered one of Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.’s supreme achievements. Kids have their own garden, Hammock Hollow, for digging and climbing and learning through play.

Longtime Ladies’ Home Journal editor and world-peace advocate Edward Bok (an interesting guy; you’ll want to read his autobiography) left us this soulsoothing sanctuary, but that’s not

all. Built of pink marble and the seashell rock coquina, and ornately embellished by some of the best artisans alive in 1929, the Singing Tower soars 205 feet above it all. It looks like a castle, but it’s actually an instrument: one of the most impressive carillons in the world. The reverberation of 62 tons of five-octave bells will stop you in your tracks, then pull you toward the tower’s reflecting pool for the listen of your life.

A walking tour of Florida Southern College in Lakeland isn’t just for prospective students. The campus is home to the largest collection of Frank Lloyd Wright–designed buildings in the world. Usonian House, designed in 1939 but built in 2013, is a model of the famed architect’s vision for minimalist living. A dozen other midcentury buildings, which still appear futuristic, are very much in use. You’ll be shaded by Wright’s mileplus-long Esplanade as you hear about his organic inspiration and the unique construction methods he employed. Danforth Chapel, with its Wright-designed stained glass, is a photogenic highlight. You might be accompanied on your walk by one of 36 campus

cats, although only two, Dexter and Gilbert, are super friendly.

A Genuine Dude Ranch

They’re not herding cats at Westgate River Ranch, an authentic, Western-themed resort that’s the largest of its kind east of the Mississippi. So pack your faded jeans and cowboy boots (you can buy a wide-brimmed hat at the general store), and fill your days with horseback and mechanicalbull rides, archery, fishing, hearty meals, and a few thrills you won’t find in Montana like loud-and-fast and totally exhilarating airboat tours. Gator sightings are routine. You don’t have to stay or “glamp” here to attend Saturday-night rodeos with their intoxicating blend of wild action and Americana pageantry you can only experience when bull riders and barrel racers give it their all.

A LEGO Lover’s Dream (with a Dash of Peppa)

Discover several worlds wrapped up in one at LEGOLAND Florida Resort in Winter Haven. Leave it to LEGO to engineer an attraction that’s sized just right and keeps everyone—little kids to grandfolks— smiling. For wee ones, the world’s first Peppa Pig Theme Park is the perfect introduction to amusement rides, shows, character photo ops, and simple pleasures like tricycling around a track. LEGOLAND offers 50 more rides and experiences like MINILAND USA with its detailed cityscapes, plus a water park for warm days. You’ll marvel at life-size (and larger!) creations. Sit behind the wheel of a red-brick LEGO Ferrari, then build and test your own race car.

Save time for a nostalgic stroll through the botanical wonders of Cypress Gardens, Florida’s original tourist attraction, or see them from the water with local guide

Rue Denton’s The Living Water Boat Cruises. Two hotels with LEGO activities galore, including in-room treasure hunts and exclusive workshops, are a few blocks from all the fun.

Swan City

Don’t overlook downtown Lakeland when you crave an elevated escape. The largest city in a county that’s a bit bigger than Rhode Island is nicknamed for its myriad swans, all descended from a mated pair gifted by Queen Elizabeth II. The century-old Terrace Hotel is the grande dame here, and it’s steps from shopping, events in Munn Park, Revival’s sophisticated cocktails, and a superb brunch at Nineteen61 (the pastelitos will spoil you for any other guava pastries). The stress-free airport’s less than 20 minutes away, so linger and squeeze every drop of juice out of your time away.

Begin planning your Central Florida vacation at

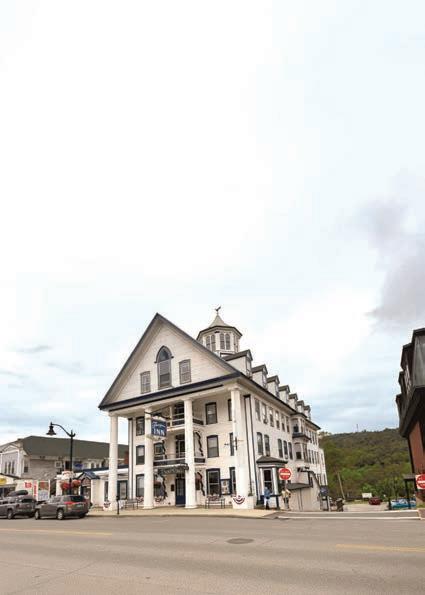

New England’s second-largest city marries a legacy of invention to a thoroughly modern mix of art, culture, and dining.

BY ANNIE SHERMAN | PHOTOS BY LINDA CAMPOS

Did you know that the monkey wrench was born in Worcester, Massachusetts? The first Valentine’s Day card, too. The birth control pill, the space suit, the liquid-fuel rocket—yup, all invented in the Woo. Even modern-day emojis can be traced back to this city, with the creation of the smiley face in 1963 for an insurance company’s marketing campaign. ¶ Worcester rose to fame as a 19th-century manufacturing epicenter, which when paired with its diverse, modern identity may spark a “Wait, Worcester has that?” moment—especially if you’ve only driven through on your way somewhere else or parachuted in for a concert at the DCU Center. But Worcester’s legacy of invention brought with it a surprisingly contemporary joie de vivre that has endured as the city’s character evolved over the decades.

Sitting almost smack-dab between Boston and Springfield, Massachusetts, the second largest city in New England boasts a population of more than 205,000, including academics and students coming from around the world to the eight colleges and universities here. Its Union Station, a stunning transportation hub built in 1911, affords easy access, too, with Amtrak, MBTA commuter rail, and city and regional bus service.

As with many New England manufacturing towns, Worcester saw its share of hard times when the industrial revolution met the Great Depression. But what drew folks to the city in the first place created a melting pot of diverse food, art, culture, and music that still percolates today. So much so that stories of laborers and craftspeople seem to ooze as much from historic stone structures in the city’s central business district as they do from its more modern Canal District or verdant green spaces that dot the City of Seven Hills’ outskirts.

Even the “Wormtown” nickname reflects this cocktail of identities. Flash back to 1978, amid the neon haze of the pseudo-underground

LEFT: A sampling of the 40-plus small plates to be had at Bocado Tapas Wine Bar.

OPPOSITE: Among the Canal District’s eclectic retail offerings is Seed to Stem, a boutique filled with wow-worthy plants and one-of-akind home decor.

the scene needed a little love, so he published a handwritten one-sheet fanzine whose title, “Wormtown Punk Punk Press,” derived from his own moniker. After other businesses and events adopted the name, too, “Wormtown” stuck.

Perhaps only in Worcester would the origins of such an irreverent-turned-affectionate nickname be remembered in a museum. The Museum of Worcester, which recently celebrated its 150th anniversary, has a library archive of written material that tells the tale (research buffs should call ahead, though, to ensure it’s available for viewing). Meanwhile, at the Worcester Art Museum just down the street, visitors can walk through part of a 12thcentury Benedictine priory as well as 2,000 years of global history in one afternoon.

It seems like everything here is “just down the street,” because Worcester is such a blissfully walkable and approachable city. At the restaurant Deadhorse Hill, solo diners bump elbows with their neighbors while relishing a glass of natural wine and perhaps some local pork chops with spring ramps that chef

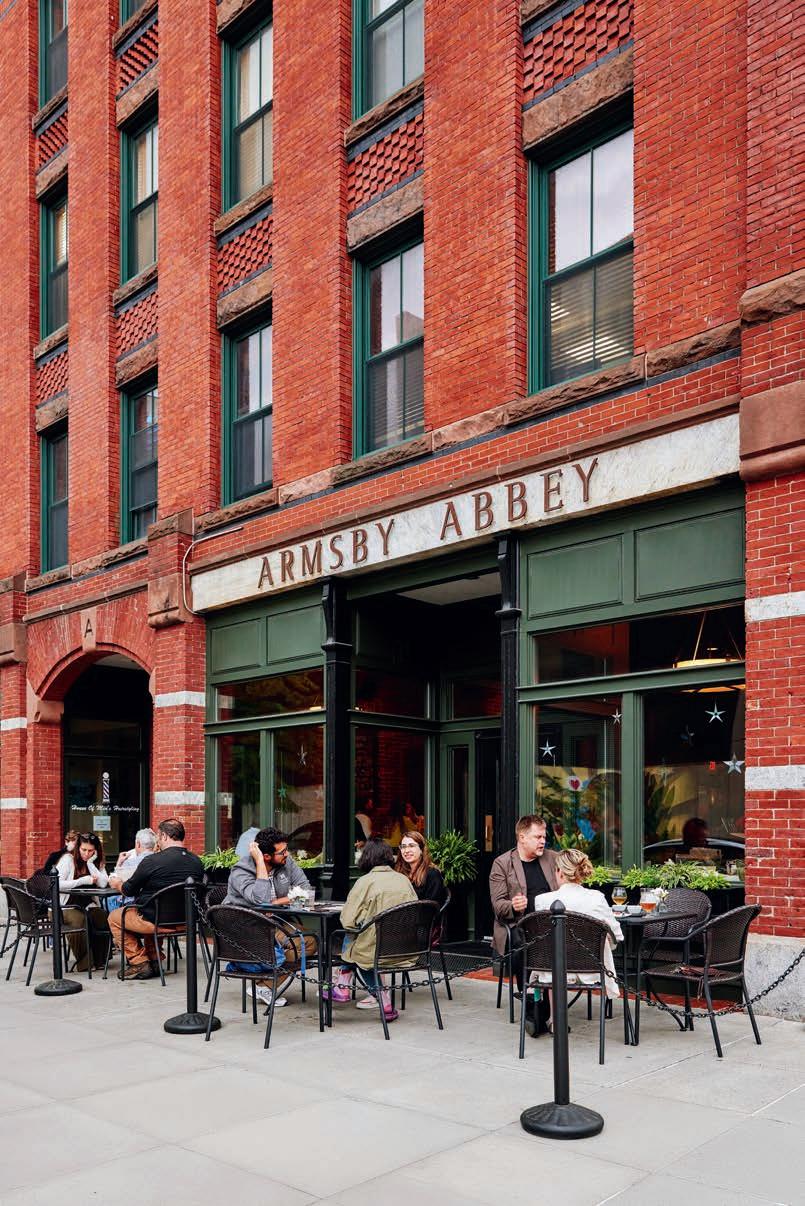

Sidewalk seating adds people-watching to the lures at Armsby Abbey, a gastropub that’s become widely known for its farm-totable fare and stellar lineup of craft beers since opening on Main Street in 2008.

Jared Forman harvested just the day before. A transplant to Worcester, Forman describes his adopted city as having a large-town feeling in a small space, where strangers can become friends in a New York minute.