54 /// Best Places to Live

Whether you’re looking to settle into a new home or just a new daydream, our favorite New England towns and small cities are calling your name.

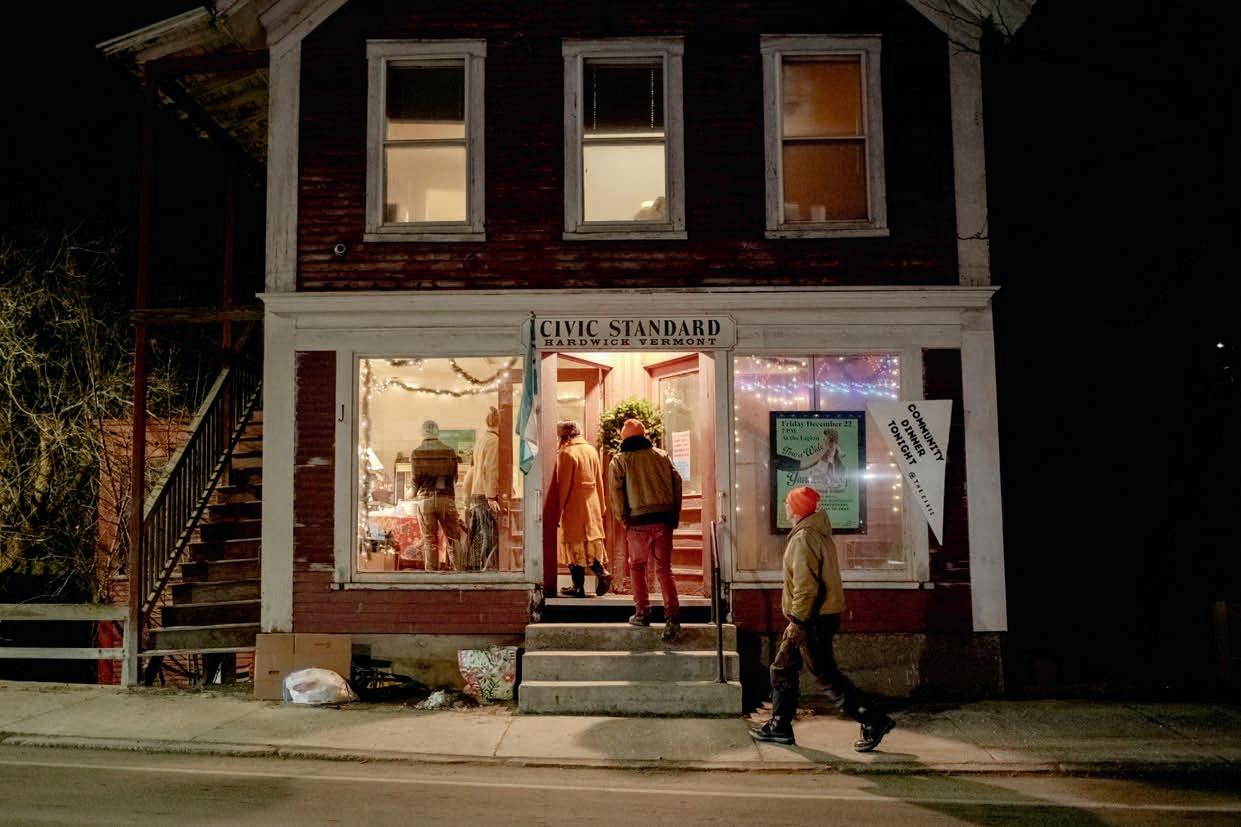

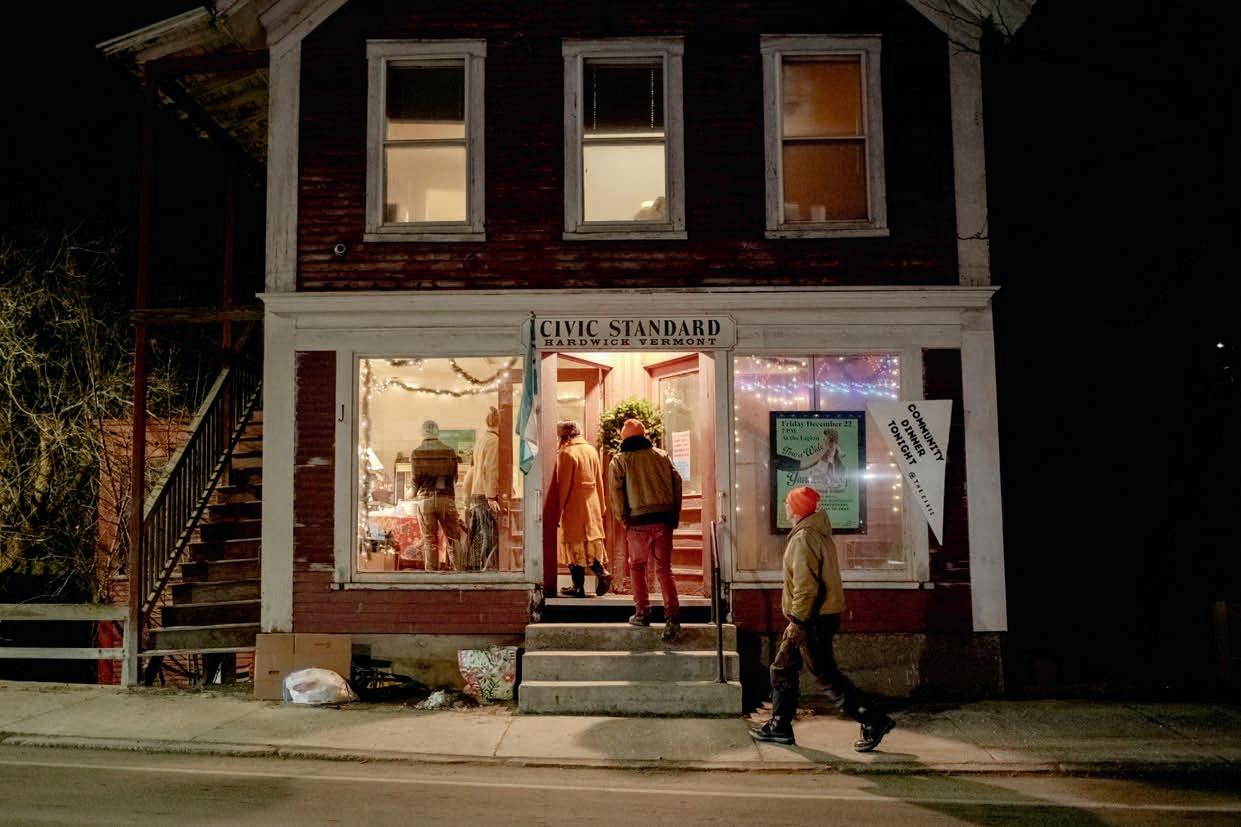

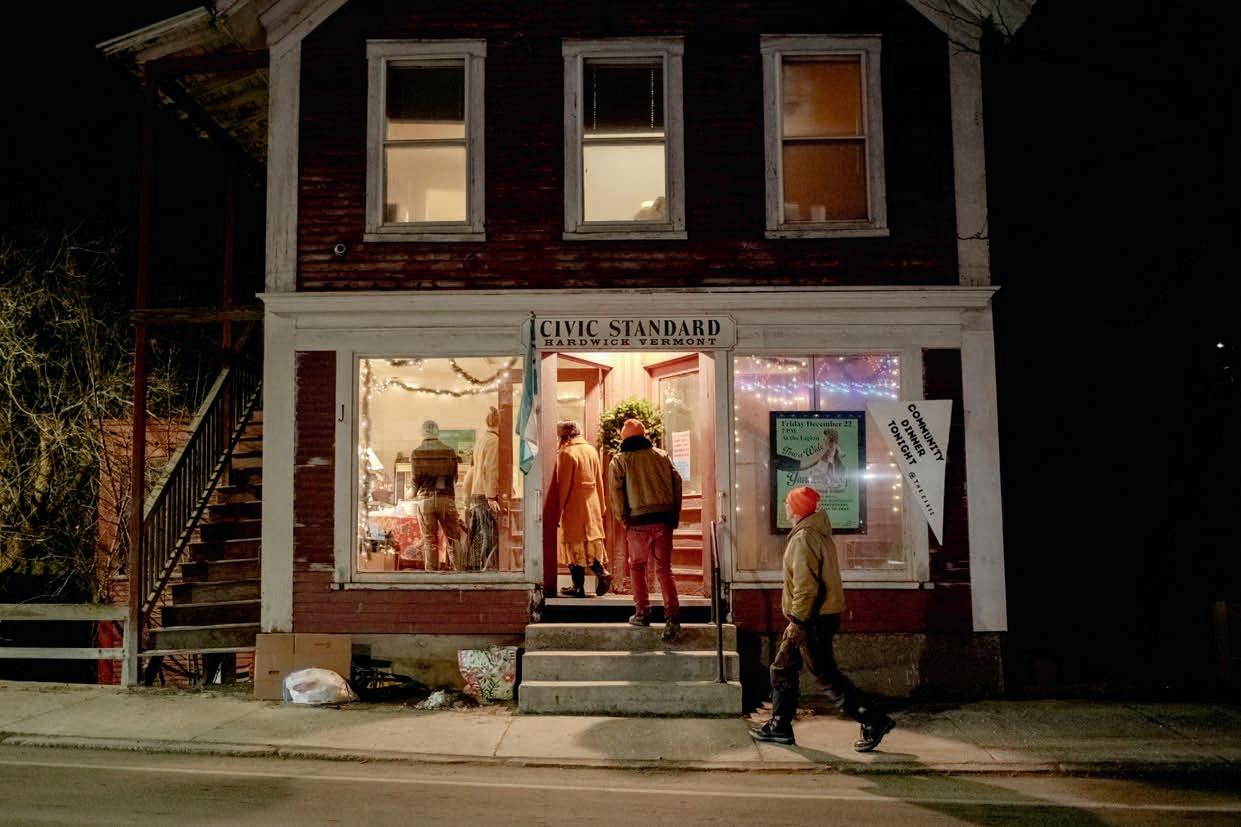

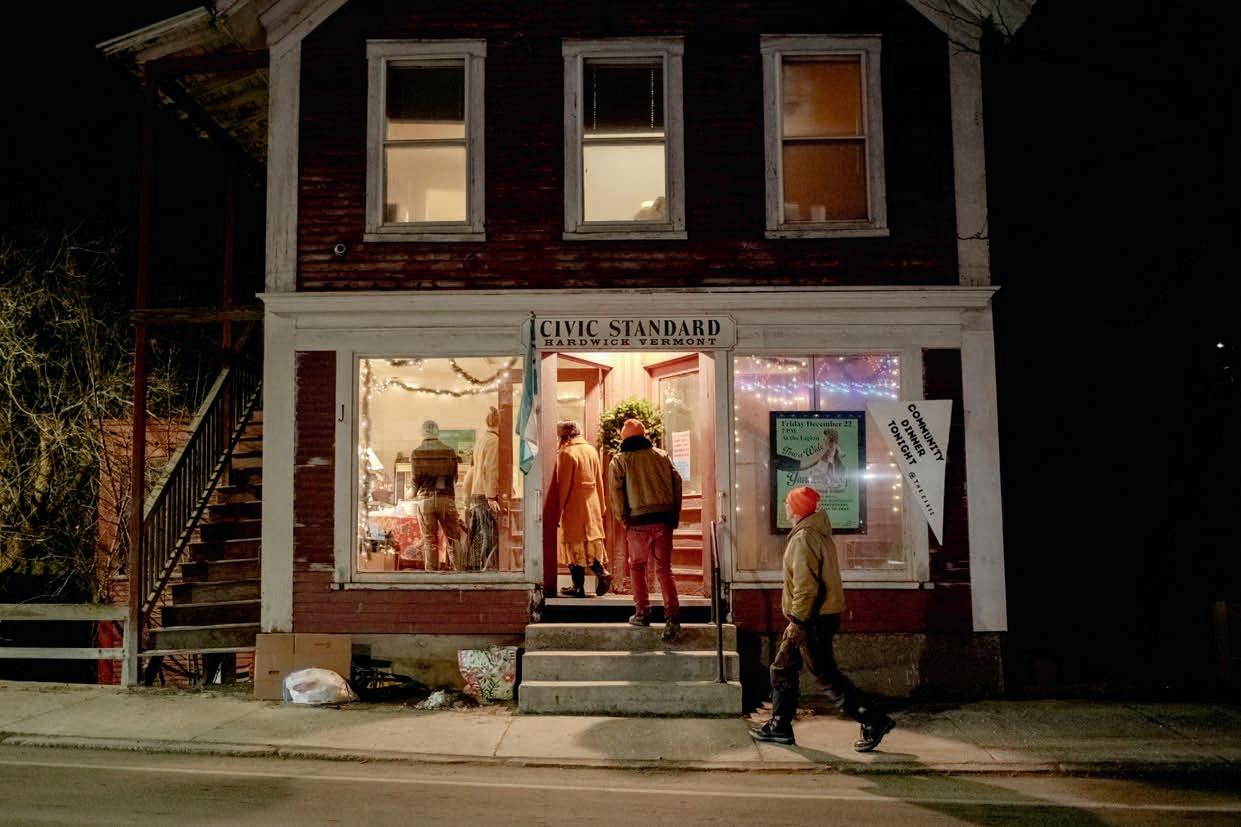

70 /// The Hardwick Blueprint

How one Vermont town’s quirky civic experiment became a primer on community-building. By Rowan Jacobsen

76 /// Home and Away

Spanning cultures and continents, photographer Greta Rybus finds threads that tie us all together.

88 /// The House with 3D Vision

An experimental home created by UMaine engineers offers hope for affordable housing and the future of Maine’s timber industry. By Julia Shipley

Bangor

Camden

Rockland

Bath

Portland

Portsmouth

Boston

MASSACHUSETTS

Plymouth

RHODE ISLAND

Bar Harbor

Boothbay Harbor

Gloucester

Provincetown

Newport Martha’s Vineyard

Nantucket

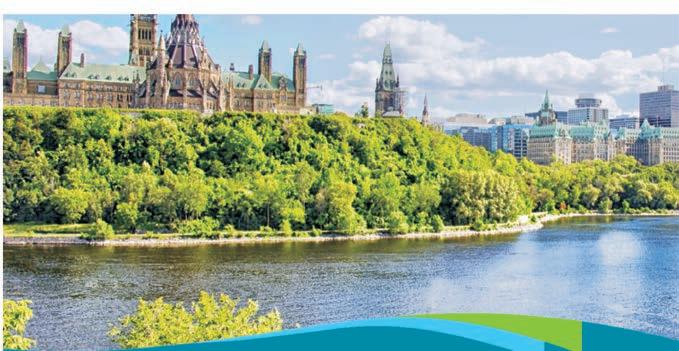

Your Grand New England Cruise Includes:

15-days/14-nights on board the ship

An exploration of 15 ports of call, with guided excursion options at each

All onboard meals and our signature evening cocktail hour

Full enrichment package with guest speakers and nightly entertainment

All tips and gratuities

Immerse yourself in the sights, sounds, and tastes of New England. From quaint island villages to the scenic beauty of the coastline, summer in New England is a delightful experience. Enjoy a local Lobsterbake, indulge in the area’s rich maritime history, and witness magnificent mansions of the Gilded Age. Be welcomed back to the comfort of your sanctuary aboard the ship and enjoy the warm camaraderie of fellow guests and crew.

28 /// Flower Power

With her floral-design career blossoming on Nantucket, Hafsa Lewis wants to inspire others to bring the beauty home.

By Meg Lukens Noonan34 /// Made in New England

Steve Smith’s hand-hewed beams give modern homes a sense of history—and a greener outlook.

By Nina MacLaughlin38 /// TV Dinners

Get a taste of the brand-new season of Weekends with Yankee, debuting on public television stations nationwide this April.

By Amy Traverso42 /// In Season

Celebrate Saint Patrick’s Day with two easy (and cozy) recipes filled with Irish flavor. By Amy Traverso

46 /// Weekend Away

Bring your appetite to West Hartford, the foodie town that no one beyond Connecticut’s borders is talking about … yet. By Kim Knox Beckius

52 /// Spring Flings

Say good-bye to winter with colorful, feel-good events and seasonal attractions in every New England state. Compiled by Bill Scheller

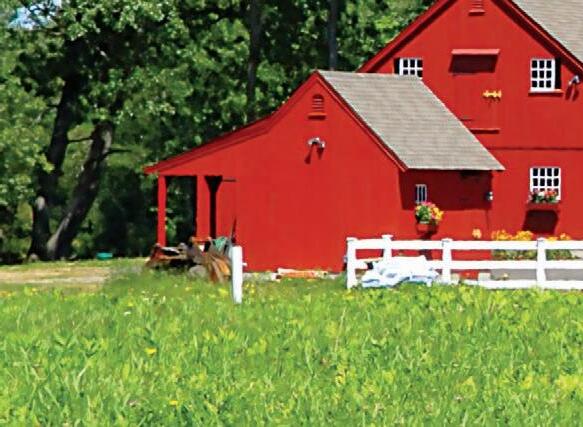

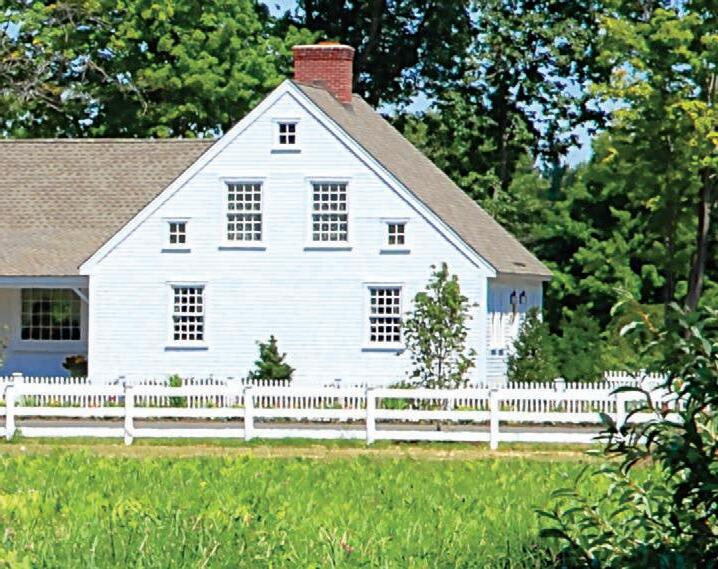

Photo: Gina Campbell

Photo: Gina Campbell

Editor Mel Allen

Managing Editor Jenn Johnson

Senior Features Editor Ian Aldrich

Senior Food Editor Amy Traverso

Senior Digital/Home Editor Aimee Tucker

Travel Editor Kim Knox Beckius

Associate Editor Joe Bills

Associate Digital Editor Katherine Keenan

Contributing Editors Sara Anne Donnelly, Annie Graves, Ben Hewitt, Rowan Jacobsen, Nina MacLaughlin, Bill Scheller, Julia Shipley

Art Director Katharine Van Itallie

Photo Editor Heather Marcus

Contributing Photographers Adam DeTour, Megan Haley, Corey Hendrickson, Michael Piazza, Greta Rybus

Director David Ziarnowski Manager Brian Johnson

Senior Artists Jennifer Freeman, Rachel Kipka

Vice President Paul Belliveau Jr.

Senior Designer Amy O’Brien

Ecommerce Director Alan Henning

Marketing Specialists Holly Sanderson, Jessica Garcia

Email Marketing Specialist Eric Bailey

ESTABLISHED 1935 | AN EMPLOYEE-OWNED COMPANY

President Jamie Trowbridge

Vice Presidents Paul Belliveau Jr., Ernesto Burden, Judson D. Hale Jr., Brook Holmberg, Jennie Meister, Sherin Pierce

Editor Emeritus Judson D. Hale Sr.

CORPORATE STAFF

Vice President, Finance & Administration Jennie Meister

Human Resources Manager Beth Parenteau

Accounts Receivable/IT Coordinator Gail Bleakley

Assistant Controller Nancy Pfuntner

Accounting Associate Meg Hart-Smith

Accounting Coordinator Meli Ellsworth-Osanya

Executive Assistant Christine Tourgee

Maintenance Supervisor Mike Caron

Facilities Attendant Ken Durand

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Andrew Clurman, Renee Jordan, Joel Toner, Jamie Trowbridge, Cindy Turcot

FOUNDERS

Robb and Beatrix Sagendorph

Publisher Brook Holmberg

ADVERTISING

Vice President Judson D. Hale Jr.

Media Account Managers Kelly Moores, Dean DeLuca , Steven Hall

Canada Account Manager Cynthia Fleming

Senior Production Coordinator Janet Selle

For advertising rates and information, call 800-736-1100, ext. 204, or go to NewEngland.com/adinfo.

MARKETING

ADVERTISING

Director Kate Hathaway Weeks

Senior Manager Valerie Lithgow

Specialist Holly Sloane

PUBLIC RELATIONS

Roslan & Associates Public Relations LLC

NEWSSTAND

Vice President Sherin Pierce

NEWSSTAND CONSULTING

Linda Ruth

PSCS Consulting 603-924-4407

SUBSCRIPTION SERVICES

To subscribe, give a gift, or change your mailing address, or for any other questions, please contact our customer service department:

Yankee Magazine Customer Service P.O. Box 37900 Boone, IA 50037-0900

Online

NewEngland.com/contact-us

Email customerservice@yankeemagazine.com

Toll-free 800-288-4284

Yankee occasionally shares its mailing list with approved advertisers to promote products or services we think our readers will enjoy. If you do not wish to receive these offers, please contact us.

Yankee Publishing

We're that charming New England getaway you've been looking for . . . much closer to home!

Located in the heart of Massachusetts, we are the heart of New England. We're best known as Johnny Appleseed Country but with our scenic countryside, outdoor adventures, quaint shops, orchards and farms, we're so much more.

Travel To - Not Through North Central Massachusetts!

For

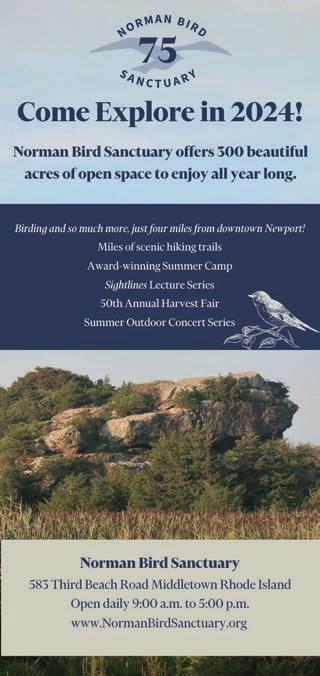

DISCOVER THE BEST OF BOTH WORLDS IN BAR HARBOR

Immerse yourself in the heart of Downeast Maine at any of our properties. It's not just a stay; it's a genuine, warm embrace of the Maine way. We focus on you—your comfort, your smiles, and creating the perfect launchpad for your adventures. With seven unique locations in Bar Harbor and Ellsworth, there's a perfect fit for your lifestyle. Stay with us and discover where harmony meets adventure.

n Thanksgiving Day, five friends and I gathered for a traditional meal. We met in one couple’s townhouse that we all agreed was a rental “find” in our southern New Hampshire town. Just steps from Main Street, it featured a porch, a stylish interior, and across the street a pretty library and a waterfall tumbling into the river. For much of our time, we talked about houses, where we might live one day if we uprooted ourselves, and how impossible it has become to find what most of us would call “affordable.” We remembered our own first houses, and how a $50,000 mortgage once felt as though we had suddenly taken on the weight of the world. And we asked how today’s younger generation could even hope to own their own place one day. Our conversation, I am certain, mirrored many others across the country.

I know we face big existential problems— climate change, the fate of our democracy, what an AI future may hold—but what I hear people talk about the most lies closer to the surface: Where can they or their children call home when it seems out of reach for so many?

But the dream is still there. We love to travel; we love sitting at a café or strolling around a harbor, or walking through a historic neighborhood. And even as visitors, we long to stick around. For our “Best Places to Live” feature [p. 54], we summon that dream. We’ve gathered up favorite places we think you’d

want to know, too. Maybe you’ll live in one of them someday, maybe not. But the search often brings rewards of its own.

Also in this issue, we invite you to step inside an extraordinary project at the University of Maine. The ingenuity of its engineers has led to the promise of thousands of efficient, affordable 3D-printed homes, each “constructed” from local wood waste [“The House with 3D Vision,” p. 88]. The project provides a glimpse into a time when we embrace living in a new way, using technology our forebears could never have imagined.

And in “The Hardwick Blueprint” [p. 70], we visit a small town in northern Vermont that’s imbued with a spirit of community and cooperation and looking out for one another. You will come away from this story knowing that what makes any place truly special is the connections we make with those around us. Maybe one day, our children will delight in living in a cozy, affordable house that took shape as if by magic in a giant lab. And when they gather with friends, they will reflect on when they feared they would never know true roots, or truly belong to a place. Now look at us, they will say.

Mel Allen editor@yankeepub.com

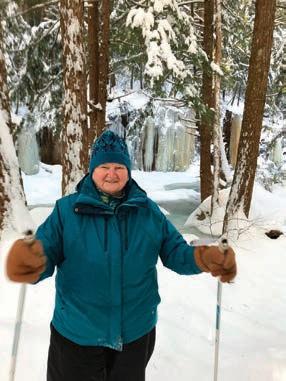

JULIA SHIPLEY

“A home is something with emotional resonance for everyone,” says Shipley, an award-winning Vermont journalist and longtime Yankee contributor. In reporting “The House with 3D Vision” [p. 88], she came away deeply impressed by UMaine engineers’ efforts to “provide a safe, lovely, environmentally sound house and home for people in desperate need … and how they are ambitiously, systematically, and creatively engineering infrastructure solutions.”

SUSIE SPIKOL

When not catching frogs with preschoolers, tracking bobcats with middle schoolers, or hawk-watching with her own three children, this New Hampshire naturalist puts her love of the outdoors onto the page [“Ode to Mud Season,” p. 16]. Her writing has appeared in Northern Woodlands, Taproot, and Minding Nature, and she recently published her first book: The Animal Adventurer’s Guide: How to Prowl for Owls, Make Snail Slime, and Catch a Frog Bare-Handed (Roost Books).

TARA ANAND

Originally from Mumbai, India, Anand is a New York–based illustrator and painter who works with clients such as The New Yorker and Apple as well as illustrates children’s books. Whereas creating artwork for “Ode to Mud Season” [p. 16] may have challenged others (“Mud as subject matter is so delightfully gross,” she notes), Anand found grace in the grubbiness. “The meat of my work as a painter is really light and texture, and this allowed me to explore both.”

ROWAN JACOBSEN

Born in rural Vermont, where he’s lived most of his life, Jacobsen has written eight books, including Apples of Uncommon Character and Truffle Hound, and contributed to Harper’s and Outside, among others. Although the author of “The Hardwick Blueprint” [p. 70] tries to maintain a solid wall of journalistic objectivity, he admits that some of his old chicken wire played a key role in a certain papier-mâché head used in the Civic Standard’s Halloween haunted house.

GRETA RYBUS

Saying “it feels like both an eternity and just yesterday” since beginning her career as a photographer, Rybus was excited to put together a retrospective of her work for Yankee, to which she’s been a frequent contributor. But in contrast to her Yankee assignments—often portraits of New England artists and makers, or beautiful travel images—“Home and Away” [p. 76] invites readers along on her globe-trotting journey to document people’s connections to the natural world.

COREY HENDRICKSON

As director of photography for season 8 of Weekends with Yankee, Hendrickson spent months shooting video all across New England—but he still found time to create the deliciouslooking photos for this issue’s food-centric feature on Yankee’s nationally broadcast travel and lifestyle show [“TV Dinners,” p. 38]. A resident of Middlebury, Vermont, where he lives with his wife and two kids, he recently finished a documentary film about food insecurity, Ramen Day, now showing at festivals.

I wanted to thank you for your recent articles on the dangers facing New England due to climate change. Most travel magazines ignore the subject despite the fact that transportation is one of the major contributors of carbon emissions. I love this part of the world and am saddened to see the destruction caused by the extreme weather we now experience. In fact, the ancient South Portland fishing shacks pictured in Jim Westphalen’s photo essay “Vanishing Beauty” [January/February] were destroyed in the storm and high tide of January 14. I hope that by bringing attention to the issue of climate change you can encourage people to travel more responsibly.

Gail Handelmann Stow, MassachusettsI enjoyed the simplicity of your “In Season” fish recipes [January/February] in terms of their ingredients, along with prep and cooking time. I actually tried the first recipe with black sea bass I caught last summer fishing between Point Judith and Block Island. It was absolutely delish, and I look forward to trying the second one.

However, what an insult to hake, sole, and redfish by listing them with tilapia, which is a farm-raised freshwater fish.... One of my favorite bumper stickers can be found on many vehicles in Galilee, Rhode Island: Tilapia is not seafood Because it is not, and should never be listed with any bona fide seafood!

Rick Black Narragansett, Rhode Island

Learning to love the squish of early spring.

I’m an outlier, an admitted rebel. I stand up for things in nature that most people find gross, alarming, or just plain ugly. A short list of animals I love includes carrion-eating turkey vultures, any type of slug, and short-tailed shrews—the only venomous mammal in North America. It isn’t just animals, either. I’d rather bend down to admire a carnivorous pitcher plant than stop to sniff a rose.

When it comes to seasons, don’t expect anything different from me. I’m the one, perhaps the only one, ready to raise my glass and cheer that soft, squishy time of year in New England known as mud season. As winter fades and the temperatures rise, snow melts. Below the melting snow, the deep layers of the ground remain frozen. Combined with early spring rains, a slurry of mud rules the land, making an ordinary walk on a back road a boot-sucking slog.

This isn’t a quick season, either. It has tenacious staying power, starting and stalling in late February and ending in May when the ground has thoroughly thawed. Mud season is a dirty, sloppy, soggy, ugly time of year that makes many New Englanders want to abandon their quaint villages and move somewhere normal, without so much mud.

I say to them: Don’t go.

Instead, grab your best muck boots and sink into this mire with me. See it for what it is—a season full of hope— when winter yields to spring, and the world becomes soft and sweet again.

I know mud season has arrived before any brown slush graces the landscape. It starts on the first warm days of February when the sun feels surprisingly warm, almost tropical. After being frozen for so long, the air smells awake with pine and spice. That’s when I see them: tiny, darkbluish-gray springtails that fill my snowshoe tracks like sprinkled pepper. Springtails, also known as snow fleas, are ancient, petite invertebrates that use their furcula—a forked appendage

on the underside of their abdomen— to fling themselves forward, like corn popping. They gather in my snowy prints, a riot of little bodies searching for mates. I am down on my hands and knees, a witness to this first signpost of my favorite season. If they weren’t so tiny, I would kiss them.

Right around the return of the springtails, the softening ground ushers in the sweetest time of the year: sugaring time. There wouldn’t be maple syrup without the mudproducing freezing and thawing that maple trees need to get their sweet sap flowing. Cold nights in the 20s are fol-

Grab your best muck boots and sink into this mire with me. See it for what it is—a season full of hope.

lowed by warm days in the 40s, loosening winter’s grasp. The sap flows, and the mud oozes. Every year, my sweetheart and I gather with friends at his sugar shack, and we talk win-

ter away with our cups filled with hot syrup and whisky and our faces ruddy with steam. Outside, we grill while our dogs run dirty through the melting snow. I wouldn’t trade these days of sugaring for a trip to the beach. Give me mud if it means there is a sugar shack filled with syrup and friends at the end of the day.

But the thing I love most about mud season is how moist and juicy it is. It is sensual. The frozen earth unbuttons and yields, spreading nutrients back to the plants, so ribbons of grass threaded with wildflowers can carpet the meadows. It is a time of courtship—you can hear it day and night throughout this season. Barred owl pairs hoot, Who cooks for you, who cooks for you all? from bare trees during the deep nights of March, and Okaree! rings from the cattail marsh as male red-winged blackbirds return to their breeding grounds. Skunks scent the air with romance, and bald eagles grasp each other’s talons as they spin and tumble to the ground in a freefalling embrace. At dawn and dusk, courting red foxes light up the browning meadows with flashes of red.

Mourning cloak butterflies dip along roadside mud puddles, fluttering down with curly tongues out to lap up the rich muck. It is the glimpse of these velvet brown butterflies, trimmed in cream with electric-blue spots, that stops me in my tracks. There it is, a butterfly, loving the mud as much as me.

It might not be pretty, and it is definitely messy, but mud season is primordial. It is the soup of life for New England. Without the melt and the ooze, the slosh and squash, spring would be too easy for us. We need mud season. It is our sugar season—when the sweetness of what is to come entices us. It is the tiny chirp of a spring peeper calling from the scrappy brown ground that reminds us that just around the muddy corner, the world still turns, love is in the air, and life continues.

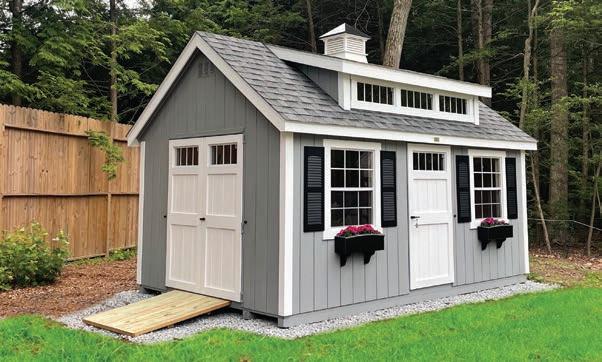

Wander through our 16-acre outdoor living display park. Whether you need a simple shed or a two-story multi-car garage, we’ll help you create an exceptional building.

storage buildings • garages • sunrooms

pool houses • pe rgolas • pavilions

swing sets • patio furn iture & more

Step inside....filled with solid wood American Made furniture and home decor. Come see why folks travel from all over New England. We’re worth the ride!

dining • bedroom • kitchen islands

sofas + sectionals • tv consoles

kitchen cabinet design - build & install

Listening to spring’s siren song at Hancock Shaker Village: peeps, squeals, and bleats from barnyard newborns.

BY JUSTIN SHATWELL PHOTOS BY MEGAN HALEYhe lamb certainly isn’t shy. On knobby knees, it takes its star turn in the middle of a circle of children. Giggling, they dart their hands closer and closer until they summon the courage to pat the creature on its head. The lamb responds with happy bleats and exploratory nibbles on the children’s shorts.

A few feet away, a group of parents—smiling, but clearly undercaffeinated—watch over their flock. When one of the children inevitably asks, “Can we get a pet sheep?” it’s answered with a heavy sigh.

While lambs and children instinctively embrace spring, we who’ve seen

a few need a little more coaxing. As our children run barefoot through the grass, we’re still pulling on wool socks out of habit and wondering if we can push off the first mow another weekend. But since 2002, the unambiguously named Baby Animals Festival at Massachusetts’s Hancock Shaker Village has provided just the jolt some of us need. A chance to get up close with the museum’s newborn animals—it’s a simple idea, but effective. This festival is to spring what a polar bear plunge is to winter; it’s a full-body immersion into everything green and young and new.

An older man approaches the crowd. “I’m Bill Mangiardi, and I’m the farm director of this beautiful place,” he says, then starts herding people onto a hay wagon. It’s an hour before the museum

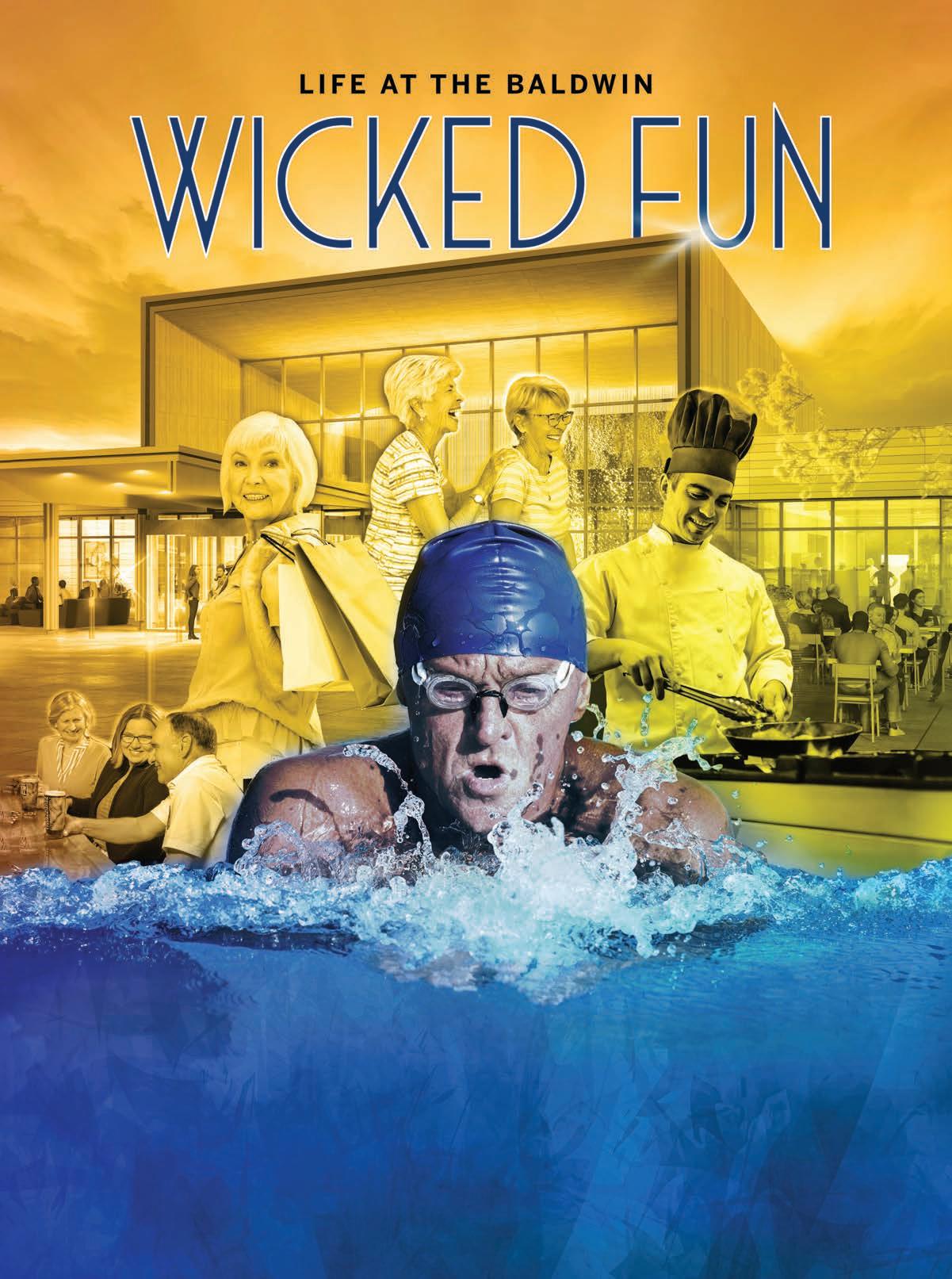

Who says kids should have all the fun? At The Baldwin — an all-new Life Plan Community (CCRC) — we say this is your time. Make a splash in the pool. Dance, stretch, lift, and box in the tness center. Learn for the love of it. Take to the nearby trails, then top o your day at the local brewery. De ne life on your terms and do whatever you choose — whether that’s everything or nothing at all.

OPEN NOW!

To learn more, call 603.699.0100 or visit TheBaldwinNH.org today.

50 Woodmont Avenue | Londonderry, NH 03053 603.699.0100 | TheBaldwinNH.org

Scan to see the latest video update or go to TheBaldwinNH.org/ Construction_Update

opens, and he’s giving a behind-thescenes tour to two dozen guests, something he’ll do every day of the festival. The lamb, adopted by Mangiardi after being rejected by its mother, trots close behind him as the last guest climbs into the wagon. “Come on, this little one needs a bottle!” he shouts.

Hancock Shaker Village is both a museum and the oldest working farm in the Berkshires. The wagon rolls peacefully by the green buds peeking up in a CSA garden. Donkeys bray from their pen; a mother cow stands protectively over a calf born just yesterday. Beyond the farm stands a line of Shaker dormitories and workhouses, each beautiful in its plainness. The Shakers were utopians who sought to make heaven on earth, which to them meant order, peace, and simplicity. Their minimalist aesthetic is still enchanting to anyone who sees the divine in a right angle and a well-swept floor.

At the heart of the village stands a massive circular stone barn. Inside, mother goats, sheep, and cows rest in pens with their newborns. A particularly vocal ewe greets the tour with a full-throated baaaah . Immediately, Mangiardi encourages children to clamber into the pens. He teases and jokes with them, paying special attention to the shy ones. With a “Here you go!” he surprises one boy by shoving a baby goat into his arms, and in an instant the youngster transforms from timid to beaming. Mangiardi ends the tour by placing a chick on each of the guests’ heads. It’s a silly moment that lets the kids laugh at their parents, and lets the parents laugh at themselves.

Outside the barn, the museum’s gates open and an unbroken column of families begins marching across the grounds. Soon a small parking lot of baby strollers appears along the barn’s curved wall. Mangiardi points to it

and grins. “That’s my favorite sight,” he says.

Inside, the barn is alive with sound. Everywhere parents are lowering children into pens, letting new life meet new life. Above, dozens of birds nesting in the rafters add their song to the chorus of laughs, moos, cheers, and baahs. It’s a peaceful chaos, almost pagan in its freedom. The straitlaced Shakers probably would have disapproved of all this clamor. It wasn’t quite their idea of heaven, but it’s heaven nonetheless.

This year’s Baby Animals Festival at Hancock Shaker Village will be held 4/13–5/5. For more information, go to hancockshakervillage.org.

The

Lewis touch can be seen everywhere on Nantucket. She wants others to bring the beauty home.BY MEG LUKENS NOONAN PHOTOS BY EMILY ELIZABETH PHOTOGRAPHY

There’s a saying: All flowers must grow through dirt ,” floral designer Hafsa Lewis tells me over lunch on a sparkling late-spring Nantucket day. “The first time I heard it, it just slapped me in the face.”

It’s easy to see why that expression hit home when you learn how Lewis found her way to floristry—and to a rebirth, of sorts—on this Massachusetts island. A series of traumatizing experiences beginning about a decade ago had left her reeling. First, she was near the Boston Marathon finish line in 2013 when the bombs went off, and she went to the aid of a gravely injured woman. Two years later, she lost her savings in a Ponzi scheme, and then in 2017 her husband abruptly left her. Devastated, she quit her job at a Boston hospital, abandoned her plan to become a mental health counselor—she holds a master’s degree in clinical psychology—and moved to Nantucket to take a bartending gig.

“It was a dark, dark time in my life. I lost 30 pounds. I had no confidence,” she says. “The only time I didn’t feel like I wanted to die was when I was surfing—or playing with flowers.”

Lewis had enjoyed dabbling in floristry as a freelancer for an event planner. But now flowers felt like her salvation, a way to lose herself in beauty when things felt so

bleak. They also presented a path forward. In 2018, she launched Hafsa & Co. as a floral marketing company specializing in the kind of large-scale fresh and faux installations that businesses increasingly use to beautify their spaces, attract customers, and generate social media hits. After attending workshops in her native England, as well as in Ecuador and Mexico, to learn the mechanics of the displays (hint: it’s all about chicken wire and zip ties), she started building her portfolio.

Among Hafsa & Co.’s most enthusiastic clients is Lemon Press, the airy organic café where we’ve met for lunch. It’s owned by cousins Darya Afshari Gault and Rachel Afshari, who happen to share Lewis’s Persian heritage and her belief in the magic of flowers.

“Our first install with Hafsa was [a small piece] over the coffee bar,” says Gault. “It was so well-received— people would come in just to Instagram

it—we said, ‘Wow, let’s keep going.’ ”

Now, the Hafsa & Co. touch is everywhere at the café. An ethereal 16-foot swag of preserved white blooms—hanging amaranthus, lunaria, helecho fern, and others— graces a brick wall in the dining area; a canopy of faux wisteria dangles over the bar; and a border of foraged grapevines and silk daffodils and forsythias frames the eatery’s exterior doorway. (Lewis would soon be shifting that seasonal entrance display to summery spray roses and ranunculus.)

Lewis has also “flowered” the Artists Association of Nantucket gallery, the Nantucket Hotel, the Nantucket Dreamland movie theater, and a host of boutiques both on and off the island. She’s done displays for annual events including the Nantucket Wine & Food Festival, the Christmas Stroll, and the Daffodil Festival; made custom pieces for private parties (floral crowns, anyone?); and presented workshops for aspiring florists.

In 2021, the noted Los Angeles–based fine-art photographer Gray Malin enlisted Lewis to create elaborate floral props for a series of vignettes he’d come to the island to shoot. That same year and again in 2022, the local Coast Guard station asked her to put her creative touch on the iconic seasonal wreaths—daffodils in spring and poinsettias at Christmastime—that it hangs on the Brant Point lighthouse. (Lewis wasn’t involved with the 2023 daffodil wreath, which was delayed by lighthouse renovations, and then made and hung at the last minute by the Coast Guard when repairs were complete.)

Like most small-business owners, she’s faced challenges. When Covid hit, she stayed afloat by making and delivering $50 bouquets with inspirational messages to residents who

Nantucket’s Sign Advisory Council questioned whether her temporary outdoor installations were technically “signs” and therefore subject to a permitting process, a red tape–heavy requirement that likely would have sunk her business. Some detractors also sniffed that her displays were not appropriate on Nantucket.

Lewis went to every council meeting for six weeks to argue that her pieces were not signs—and that they were no different from the flower boxes most shops maintain. “I also wanted them to know the reason they were seeing more installations is because our community wants them. They make people happy.”

The controversy ended when the town unexpectedly ordered the council to disband before it made any recommendations. “And I’m still here to flower another day,” she says, smiling broadly.

Through it all, Lewis has remained mindful of what drew her to flowers: their power to heal, to express joy and sorrow, and to forge connections.

“The science part of my brain,” she says, “is really interested in how therapeutic flowers can be”—so interested, in fact, that she’s starting a doctorate program in clinical psychology this year with the idea of one day using flowers in a counseling practice.

“We have art therapy and pet therapy,” she says. “Why not flower therapy?”

There’s a bit more to the tale of how Hafsa Lewis blossomed on Nantucket. Those Coasties she helped with the lighthouse wreaths? Last summer, she married one of them.

“It was such a ‘meet cute,’” she says. “My friends tell me my life should be a Hallmark movie.” hafsaandco.com

Granted, you’re probably not planning to erect an elaborate floral installation in your home. But Hafsa Lewis says the principles behind her “big stuff” apply to the simplest arrangements, too.

l Picking your flowers: “Go with the ones that make you feel something,” she says, “whether it’s a $24 stem or a sad-looking Charlie Brown–type grocery-store flower. If you’re moved enough by something that nature’s created, and it sparks joy inside of you, then you should take it home and make it your own.”

l Choosing your vessel: “Pick one that allows your flowers space to breathe. If they’re stuck in a vase that just stands them straight up, they can feel stiff. That’s not how they are in nature. They grow loose and wild and free. Let each flower have its moment—it doesn’t matter if it’s the side or the back or the front of the stem. Flowers are beautiful from all angles.”

l Setting up for success: “First, make sure your vessel is clean. Remove any leaves from the stem that would be under the waterline, since submerged leaves can cause bacteria that will shorten the flowers’ shelf life. Give the stems a fresh cut before you put them in water.”

l Taking your time: “I often walk away from a piece for a while so that I can come back to it with fresh eyes. And I take pictures in order to get a different perspective. That helps me see what’s missing and what I could do differently. I think that works for both large- and smallscale things.”

l Honing your skills: Lewis recommends photographing one arrangement you do now and one you do in six months, then studying the pictures to see what you’ve done differently and what has stuck with you. “Did the shape change? Did you pick different colors? Once you start to pay more attention, you learn what you like and what is most meaningful to you.”

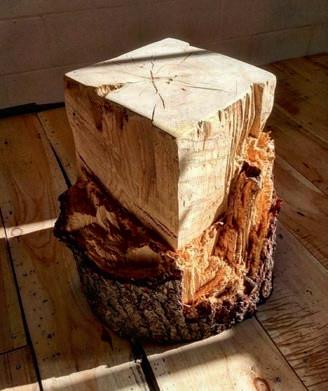

Using only an ax, Steve Smith resurrects the centuries-old craft of hand-hewing to bring both history and new life into today’s homes.

BY NINA MACLAUGHLINThe thunk comes first, the sound of ax through wood. It’s a sound that registers in the body as much as the ears, a sound that one feels in the center of oneself: the exchange between blade and trunk, forces of muscle, bone, gravity, and tree, and then the whisper of wood-chip shrapnel landing on the grass.

Such is the aural landscape of Renaissance Timber in Cumberland, Maine, where Steve Smith practices the craft of hand-hewing, taking the round trunk of a tree and shaping it into a square beam. No power tools, no screaming saws or spinning blades. Just his body, the tree’s body, the ax.

And what results—structural beams and mantels of white pine, cedar, cherry, oak—breathe with life and history. They take their places in homes, above the hearth or supporting the ceiling, and become part of the soul of the place. They draw the eye, and more than the eye.

“People are homesick for imperfection,” says Smith. Every mark you see on one of his beams was a decision, part of an intimate connection between man and tree. “It’s a conversation between souls,” he says. And that conversation reverberates, providing a palpable sense of warmth absent from the sterility of industrialized

perfection. And it will last longer, too.

Smith, 43, talks of the planned obsolescence of modern-day building materials. “The stuff I’m making will be here 200 years from now,” he says, the wood speaking to the future as well as the past in its rough Maine vernacular. It’s a legacy item, he says, and to be in a room with wood he’s hewed is to “step into the river of history. It gives a sense of movement in a way that sheetrock doesn’t.”

Smith’s evolution as a hand-hewer has its roots in the past as well. His great-great-grandfather drove logs downriver in Maine; another sold used lumber. And Renaissance Timber is based on the farm where Smith grew

up. A sense of heritage is important to him, the circle of life and growth and connection. When we met, he’d just finished building a small cabin playhouse for his two boys and was readying to turn the front section of the dairy barn into a showroom. The trees he uses come from his land, or that of his clients; the carbon footprint of his work is zero.

We met on a bright, warm September afternoon, the autumn equinox, and Smith was hewing a tree by the barn as the sun made the grasses glow gold in the field to the south. He’d marked the edges and snapped chalk lines down the length of the trunk; he’d stood on one side of the tree and axed a series of wide notches, concave openings every 18 inches or so. And then, with left knee resting on the log and right foot planted on the ground, he raised the ax and brought it down, that great deep thunk, jogging out the sections between the wide inviting openings, fragments of wood flying through the afternoon light.

Broad of shoulder, thick of bicep, Smith does not have the vanity-driven

THIS PAGE: A partially hewn stool shows the alchemy of Steve Smith’s work: transforming round logs into square beams.

OPPOSITE: Smith holds a bearded broad ax that he had custom-forged by another Maine traditionalist, blacksmith Nick Downing.

chiseled form of a gym-goer but the fullbody strength of someone who uses that body for his work. It hasn’t always been so: He’s relatively new to hand-hewing, having started the business in 2019. Working a white-collar job, he tore his bicep lifting something heavy, tweaked his back logging so many hours at a desk, and worse, knew the staticky fuzz of being in front of a screen all day. Then a book crossed his path, A Reverence for Wood by Eric Sloane, and he watched the hewing process on YouTube. He took down a cedar and gave it a shot. “It resonated,” he said. While his days in front of a screen blurred together as one, “I remember every place I’ve been in the woods for clients. I remember the bugs, the temperature, the light.”

Smith carries himself with the humility of someone who’s asked himself the hard questions, recognized the painful fact that how he’d understood the world was wrong, and had the courage to make a change. He has the spark in his eye that people who are in intimate relationship with the land have,

LED bulbs use less energy and last longer than their fluorescent counterparts. Not to mention they give off less heat and offer more flexibility in color, dimmability, and directional lighting.

Planning to travel this spring? Limit greenhouse gas emissions by ditching those planes and automobiles in favor of trains, a more sustainable mode of transportation.

Join us for a unique farm-stay experience that your family will never forget. We’re proud to be Vermont’s first certified Green Agritourism Enterprise and a member of Cabot Creamery, a farmer-owned cooperative and certified B Corp.

ROCHESTER, VT | (802) 767-3926

LIBERTYHILLFARM.COM

ROCHESTER, VT | (802) 767-3926

LIBERTYHILLFARM.COM

Choosing broccoli over bacon isn’t just good for your body: Studies show that reducing meat consumption is a great way to shrink your carbon footprint.

Potato peels and eggshells do far more good in your garden than in a landfill. Starting a compost pile lets you add nutrients back into your soil while cutting down on what you lug to the dump.

Rabbit Hill Inn aims to minimize its environmental impact, while still providing a luxury getaway experience. A guest favorite is our sustainable bottled water program. Glass water bottles are filled from an on-site natural spring and placed in the rooms and throughout the inn.

LOWER WATERFORD, VT | (802) 748-5168 | RABBITHILLINN.COM

Celebrating 15 years!

Thousands of happy customers continue to enjoy Owl Furniture’s comfortable postural support and ergonomics. Join the party!

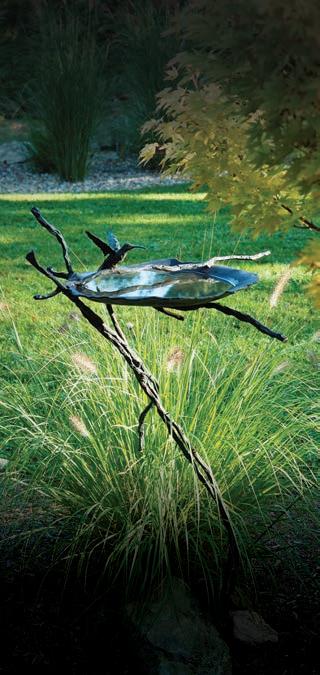

HANDCRAFTED BEAUTY

SUSTAINABILITY COMMITMENT MADE IN MAINE

ROCHESTER, VT | (802) 767-3926

LIBERTYHILLFARM.COM

STONINGTON, ME | (207) 367-6555

OWLFURNITURE.COM

Senior food editor Amy Traverso chats with Jonathan Laurence, captain and founder of Moon Dog Excursions, during a Weekends with Yankee shoot in Camden, Maine.

Taste a preview of the new season of Weekends with Yankee, coming to public television stations nationwide in April.

BY AMY TRAVERSO | PHOTOS BY COREY HENDRICKSON | STYLING BY LIZ NEILYTo make the eighth season of Weekends with Yankee , the public television show that we produce with Boston’s GBH, I traveled across New England by skiff, by lobster boat, and by hayride. I hiked the dunes of Cape Cod to collect beach plums for jam, made honeyberry ice cream in the White Mountains, fried cider doughnuts at an orchard in Massachusetts, drank Maine-made bubbly in a treehouse hot tub, and ate a scallop fresh from the

waters off Stonington, Maine. In short, it was a season of adventures, stunning scenery, and culinary delights. I hope you’ll tune in as we roll out 13 new episodes over the coming weeks, and that you’ll enjoy watching them as much as we enjoyed making them.

To whet your appetite, here are five recipes from season 8, along with the stories that inspired them. To find all the recipes we made over the course of filming the show, go to newengland.com/tv-dinners.

A bright gremolata of fresh parsley, garlic, and lemon zest pairs with creamy pasta and delicate lobster in this dish from acclaimed Maine restaurant Aragosta (recipe, p. 40).

A bright gremolata of fresh parsley, garlic, and lemon zest pairs with creamy pasta and delicate lobster in this dish from acclaimed Maine restaurant Aragosta (recipe, p. 40).

Chang Thai Café | Littleton, NH

A native of Bangkok, Emshika Alberini moved to the U.S. to study business but changed course after her beloved sister, Sriwipha, passed away in 2006. Her sister’s dream had been to open a modern Thai restaurant, so Emshika made that dream her own. She’s been earning culinary accolades ever since with her Littleton restaurant, Chang Thai Café.

On a peak-foliage fall day, I visited the home that Emshika shares with her children and mother, “Mama Nee” Ketsatin, to make pumpkin curry. I’ve had Thai red curry before, but never anything this good. This easy, flavor-packed dish is now in my regular weeknight rotation.

If you don’t have access to a market with a decent selection of Thai ingredients, you may need to go online to source three key ingredients: red curry paste, fish sauce, and kaffir lime leaves (feel free to use dried lime leaves instead of fresh). The recipe also calls for Thai basil, but you can substitute the more common sweet Italian basil. And vegans can make the dish without chicken—just add tofu or an extra pound of squash.

Note: Emshika recommends using Thai fish sauce, such as Squid brand. For red curry paste, she and her mother either make it from scratch or use Maesri brand. For coconut milk, you’ll get the creamiest results if you use the full-fat version, but you can certainly use the reduced-fat type.

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

2 tablespoons Thai red curry paste

2 cups coconut milk

½ medium peeled and seeded kabocha squash, sugar pumpkin, or butternut squash, cut into 1-inch cubes (about 1 pound)

1 pound boneless, skinless chicken breast or thighs, cut into 1-inch pieces

3 kaffir lime leaves, torn

2 tablespoons fish sauce, plus more to taste

Yankee’s national travel and lifestyle series, WEEKENDS WITH YANKEE, kicks off its new season this April on public television stations across the country. To find out how to watch, go to weekendswith yankee.com.

3 tablespoons brown sugar, plus more to taste

½ teaspoon kosher salt

C ooked jasmine rice, for serving

1 sliced serrano, jalapeno, or other chili pepper (optional)

½ cup chopped Thai basil or sweet Italian basil

Warm the oil in a 4- or 5-quart Dutch oven over medium heat. Add the red curry paste, stir, and let it cook for a minute, then whisk in the coconut milk.

Add the squash, chicken, kaffir lime leaves, fish sauce, brown sugar, and salt and cook until the squash is tender and chicken is cooked through, 20 to 30 minutes.

Serve the curry over cooked rice and sprinkle with chili (if using) and basil. Serve hot. Yields 6 to 8 servings.

LOBSTER PASTA

Aragosta | Stonington, ME

The dirt road that leads down to Goose Cove is so exquisitely bordered by spruce, moss, and aspens that we were in a reverie by the time we pulled up to Aragosta, the storied farm-to-coast-totable restaurant and inn in Stonington. Piling out of our cars, we blinked at the sweeping view of sandy beach and East Penobscot Bay for just a moment before chef-owner Devin Finigan stepped out of the kitchen, prepped and ready to cook.

In Italian, aragosta means lobster, and the one dish that Devin can never take off her menu is the agnolotti with lobster and beurre blanc. This stuffed pasta dish is a signature, one that she was kind enough to adapt into something that

a home cook can easily make, provided you’re willing to buy precooked lobster meat (or steam and shell your own). It’s a splurge, but it’s absolutely worth it.

1 tablespoon minced garlic

1 tablespoon minced fresh parsley

1 tablespoon freshly grated lemon zest

1 p ound cooked lobster, cut into bite-size pieces

½ cup mascarpone cheese

1 tablespoon lemon juice

Freshly grated zest of 1 lemon

1 small garlic clove, minced

¼ cup chopped fresh parsley

Kosher salt, to taste, plus more for pasta water

12 ounces dried linguine or tube-shaped pasta

½ cup dry white wine, such as pinot grigio

1 small shallot, minced

2 tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into small cubes

2 tablespoons heavy cream

First, make the gremolata: In a small bowl, stir together the garlic, parsley, and lemon zest. Set aside.

Now, make the lobster mixture: In a large bowl, use a spatula to fold the lobster meat with the mascarpone, lemon juice, lemon zest, garlic, and parsley. Add salt to taste. Set aside.

Set a large pot of salted water over high heat and bring to a boil. Add pasta and cook according to package instructions until it is still just a bit firm in the center, or al dente.

Meanwhile, in a large skillet over medium-high heat, bring the wine to a simmer with the shallot. Simmer until the wine reduces to about 2 tablespoons. Add the butter, a few cubes at a time, whisking as you go. It should blend in and look creamy. Add the cream and stir until the sauce

Amy joins chef Dan Coté in the Pelham House Resort kitchen for a walkthrough of his clam chowder (RIGHT). Recipe, p. 94

Cider doughnuts meet bread pudding in a delectable dish (LEFT) inspired by Cider Hill Farm, which is tended by field manager Grigore Chitas and his family.

Recipe, p. 94

“Mama Nee” Ketsatin makes Thai pumpkin red curry (LEFT), a favorite offering at daughter Emshika Alberini’s Chang Thai Café.

Amy joins chef Dan Coté in the Pelham House Resort kitchen for a walkthrough of his clam chowder (RIGHT). Recipe, p. 94

Cider doughnuts meet bread pudding in a delectable dish (LEFT) inspired by Cider Hill Farm, which is tended by field manager Grigore Chitas and his family.

Recipe, p. 94

“Mama Nee” Ketsatin makes Thai pumpkin red curry (LEFT), a favorite offering at daughter Emshika Alberini’s Chang Thai Café.

Celebrate Saint Patrick’s Day with this pair of easy (and cozy) recipes.

BY AMY TRAVERSO STYLED AND PHOTOGRAPHED BY LIZ NEILY

ormally, I develop recipes for this column based on an ingredient that comes into season at the same time each issue hits your mailbox. And every year, March presents a challenge: In early spring, there isn’t much in the way of fresh produce on offer. Newfoundlanders traditionally called March “the long and hungry month,” a reference to the waning stores in their root cellars. Of course, there’s always maple syrup. But this year, my mind turned to Saint Patrick’s Day and Irish food.

Specifically I thought of colcannon, a dish of mashed potatoes, shredded cabbage or kale, and herbs. I like to make it with Napa cabbage and scallions, two green ingredients that give flavor and character to the spuds (and add nutritional value, too). And while colcannon is usually served as a side dish, it makes a fine topping for a simple shepherd’s pie, which you can make with beef or lamb, and which gets its added layers of flavor from a dollop of tomato paste and Worcestershire sauce.

For dessert, I decided to take a classic chocolate Guinness cake and reimagine it as brownies. This took many testing attempts to perfect, since brownie recipes don’t usually incorporate liquid ingredients. But the stout adds a lovely flavor that’s almost gingerbread-like. And you can make the batter in one pot in a matter of minutes. So much for a long and hungry month.

Tasting Boxes, Gifts, Gift of the Month Clubs I Leave the Sending to Us!

Tasting Boxes, Gifts, Gift of the Month Clubs I Leave the Sending to Us!

Kosher salt, to taste, plus more for the cooking water

1½ pounds Yukon Gold potatoes, peeled, cut into 1-inch chunks

4 tablespoons salted butter, divided

2½ cups shredded Napa cabbage

2 scallions, all parts except root, thinly sliced crosswise ²⁄3 –1 cup milk, warmed

Freshly ground black pepper

3 tablespoons olive oil, divided

1½ pounds ground beef or lamb

1½ teaspoons kosher salt, divided 2 carrots, diced

2 celery stalks, diced

1 medium onion, diced

3 garlic cloves, minced

1 teaspoon dried thyme

1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

3 tablespoons tomato paste

1 tablespoon Worcestershire sauce

3 tablespoons all-purpose flour ½ cup beef or chicken stock, or stout

First, make the topping: Put the potatoes in a medium pot with enough

salted water to cover them by 1 inch. Bring to a boil, then reduce heat to medium and simmer until tender, 12 to 15 minutes. Using a strainer, remove the potatoes to a bowl and set aside. Discard the water.

Return the pot to medium heat. Add 2 tablespoons butter, swirl to melt, then add the cabbage and scallions and cook, stirring, until tender, about 5 minutes. Season with a pinch of salt. Return the potatoes to the pot and mash until nearly smooth. Add the milk and remaining butter, stirring and mashing until creamy. Season with salt and pepper. Cover and set aside.

Preheat your oven to 375°F and set a rack to the middle position. Now, make the filling: In a large skillet, warm 1 tablespoon oil over mediumhigh heat. Add the beef or lamb and ½ teaspoon salt and cook, stirring and breaking up the meat, until no longer pink, 7 to 9 minutes. Transfer to a bowl with a slotted spoon.

Remove all but 1 tablespoon fat from the skillet; return to medium heat. Add the remaining 2 tablespoons oil. Add the carrots, celery, onion, garlic, thyme, pepper, and remaining 1 teaspoon salt. Cook, stirring occasionally, until vegetables are softened and a bit browned, 6 to 8 minutes. Add the tomato paste and Worcestershire sauce

and stir until the vegetables are coated. Return the meat and any juices to the skillet. Sprinkle the flour over all and cook, stirring, for 1 to 2 minutes. Add the stock (or stout) in a slow stream, stirring as you go. Simmer until the mixture has thickened slightly, 1 to 2 minutes. Remove from heat.

Spoon the topping in dollops over the filling. Use the back of a spoon to gently spread it evenly over the top. Bake until golden brown in places and bubbling along the edges, 30 to 35 minutes. Let sit for 10 minutes before serving. Yields 6 to 8 servings.

CHOCOLATE STOUT BROWNIES

1 cup (2 sticks) unsalted butter

½ cup Guinness or other stout

½ cup unsweetened cocoa powder

1¾ cups granulated sugar

2 large eggs, beaten

1¼ cups (175 grams) all-purpose flour

1 teaspoon baking soda

1 teaspoon table salt

Preheat your oven to 350°F. Take a 9-by-13-inch baking pan and cut 2 lengths of parchment paper to fit in the pan but long enough to hang over the sides by a few inches. Lay them in the pan, one in each direction, so they cover the bottom.

In a 3- or 4-quart pot over medium heat, melt the butter with the stout and whisk to combine. Remove from heat and whisk in the cocoa powder. Add the sugar and whisk until smooth. (Each addition will lower the temperature of the batter.) Whisk in the eggs.

In a medium bowl, whisk together the flour, baking soda, and salt. Add the dry ingredients to the wet, and stir with a spatula until smooth and evenly combined. Pour the batter into the prepared pan and bake until the brownies are set in the center and beginning to pull away from the sides, 30 to 45 minutes. Let cool in the pan and then transfer to a rack or plate to cool completely. Yields 12 to 16 servings.

Lady Captain’s SparHawk Maine Tourmaline Ring G4685...$1,350

Wellspring SparHawk Maine Tourmaline & Diamond Ring X3823...$2,650

Olympian Winner SparHawk Maine Tourmaline Ring G4698...$2,275

Revere SparHawk Maine Tourmaline & Diamond Ring G3080...$4,375

The Schooner SparHawk Maine Tourmaline & Diamond Ring G4192...$6,150

Star Light, Star Bright SparHawk Maine Tourmaline & Diamond Necklace G4573...$3,075

SparHawk Maine Tourmaline & Diamond Earrings G3709...$4,875

We’ve been mining gems in Maine for over two-hundred years. Something amazing happened in our Western Mountains 12 years ago. One of the richest finds of tourmaline in the world occurred just 25 miles north of Portland. The tourmaline find was amazing, it was called SparHawk, It had some of the prettiest green tourmaline ever found in Maine’s Western Mountains.

The large picture is a glimpse into the Silver Dollar Pocket. A cave in a cliff. Tourmaline crystals were covered with a type of white clay that when washed away revealed green tourmaline crystals of extraordinary color and clarity.

The large SparHawk tourmaline crystal held in the smaller picture came from the Silver Dollar Pocket and is now in the Smithsonian Museum in Washington D.C.

is always Safe, Fast and

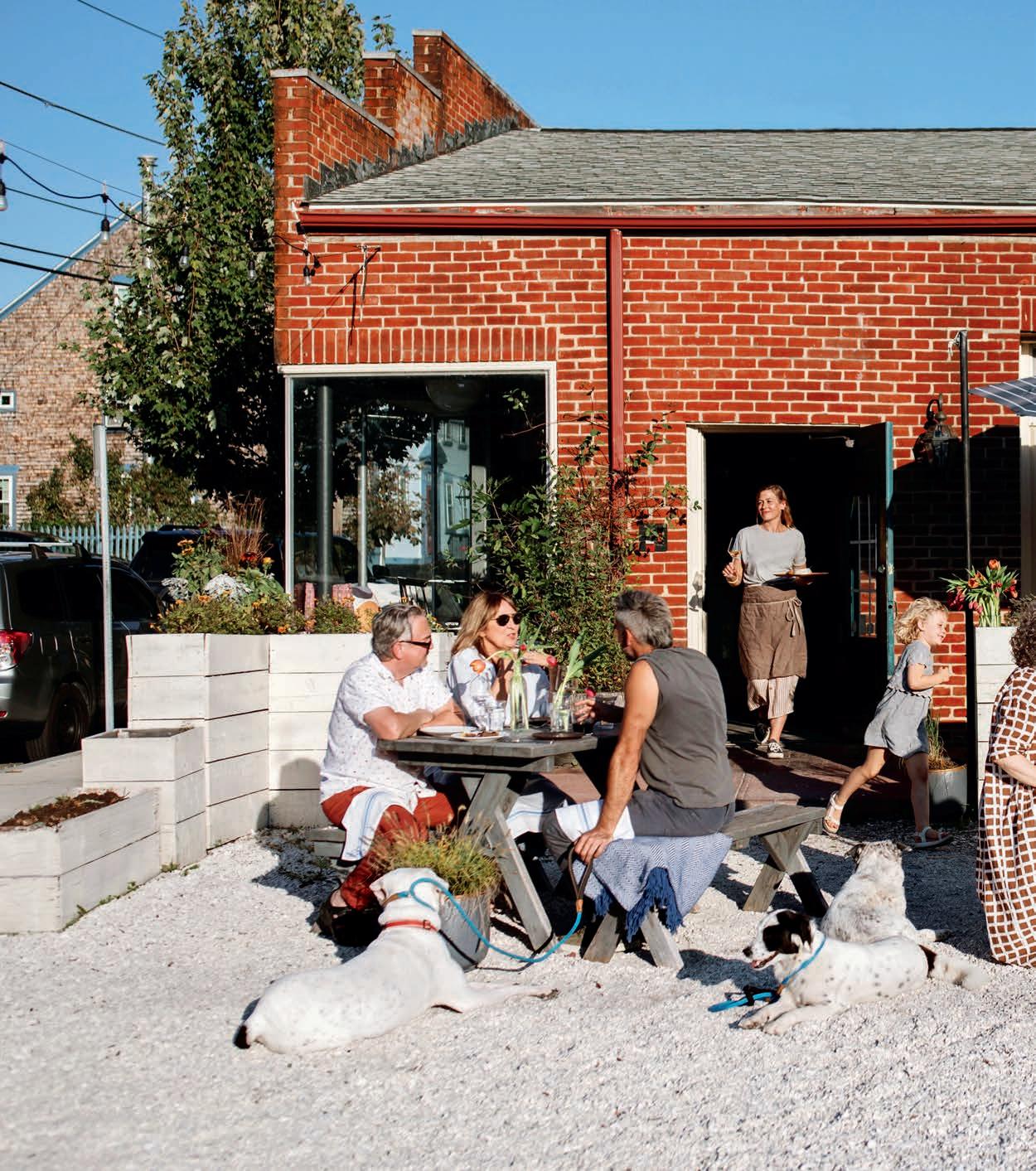

THIS CULTURED SUBURB IS THE FOODIE TOWN NO ONE BEYOND CONNECTICUT’S BORDERS IS TALKING ABOUT … YET.

PHOTOS BY JULIE BIDWELL

PHOTOS BY JULIE BIDWELL

THIS PAGE: Àvert Brasserie lends a soupçon of French flavor to West Hartford’s sidewalk dining scene. OPPOSITE, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: Ella Baker, Martin Luther King Jr., and Bernard Lafayette Jr. grace a mural by Corey Pane in Blue Back Square; blooming wonders in Elizabeth Park; a passel of pots at Moscarillo’s Garden Shoppe; elevated Peruvian fare at Coracora.

THIS PAGE: Àvert Brasserie lends a soupçon of French flavor to West Hartford’s sidewalk dining scene. OPPOSITE, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: Ella Baker, Martin Luther King Jr., and Bernard Lafayette Jr. grace a mural by Corey Pane in Blue Back Square; blooming wonders in Elizabeth Park; a passel of pots at Moscarillo’s Garden Shoppe; elevated Peruvian fare at Coracora.

I’ve never been to Paris in the springtime, but I’ve been to West Hartford. Don’t laugh-cry for me. Connecticut’s own little slice of Europe is one of those “if you know, you know” places that many travelers overlook. It’s equidistant from Boston and New York City, and you’d be hard-pressed to find a few-block area in either metropolis with the variety of cuisine that awaits in this sophisticated suburb with 63,000 residents and two Whole Foods Markets. When temperatures nudge up in April, out come the sidewalk tables, the street musicians, the couples of all persuasions strolling hand in hand through West Hartford Center and adjacent Blue Back Square. Up spring the tulips, in parks with architectural features and flowering trees worthy of Impressionist paintings.

I’ve known West Hartford for half my life, but I sometimes forget how rich it is in Connecticut-centric shopping. In places to walk. In neighborhoods like Elmwood and Bishops Corner, with their own character and restaurant finds. How steeped it is in history.

The newest commercial district is named for local son Noah Webster’s Blue Back Speller. His birthplace is one of 41 notable locations mapped on a weathered sign on South Main Street, not far from his 13-foot marble likeness, sculpted for the town by Korczak Ziolkowski of Crazy Horse Memorial fame. I feel like a slacker as I circle the statue of my dictionary idol, reading his credits: Activist, Author, Educator, Farmer, Journalist, Patriot, Publisher, Scholar.

There is value in slacking, though. So I’ve been weekending in WeHa often with the aim of setting to rest a question I hear perennially from Connecticut friends: Why doesn’t anybody write about West Hartford as a destination?

Truthfully, it’s with some reluctance. Can I live with longer lines for my food-truck favorites at the year-round GastroPark (oh, Hindsight Barbecue, you slay me with your pulledpork mac and cheese)? Could it become more challenging to secure a table at Coracora, a foodie magnet since chef Macarena Ludena’s Peruvian dishes earned this unassuming Elmwood eatery (it’s in a former McDonald’s) a 2023 James Beard Award nomination for most outstanding restaurant in the country?

And what about divulging secrets like the labyrinth concealed in the forest behind

DORO Marketplace: The pastries are scrumptious, but don’t miss the homemade bagels, fried-chicken sandwiches, sourdough pizza slices, and Connecticut-roasted Shearwater coffee drinks. doromkpl.com

Sparrow Pizza Bar: In a state known for pizza, leave it to Chopped grand champ Adam Greenberg to prove “New Haven style” is not the only way to go. The bar here stays lively until midnight on weekends. sparrowpizzabar.com

Coracora: Accolades pour in for this familyowned Peruvian standout. Head chef Macarena Ludena worked her way up from bussing tables in her parents’ restaurant, and recently her empanadas, ceviches, and fried whole sea bass earned 2023 Connecticut Restaurant of the Year honors. coracoraeats.com

DORO Restaurant Group: Any one of DORO’s three West Hartford Center restaurants would warrant a road trip. How about nibbles at all three? Mussels aux frites and fondue at Àvert Brasserie, ricotta-stuffed zucchini blossoms and the ravioli del giorno at Treva, and seasonally inspired hummus and colossal roasted cauliflower at Zohara dororg.com

Delamar West

Hartford: With its own farm-to-table-focused Artisan restaurant

Copper Beech Institute, a nonreligious mindfulness-education nonprofit at Holy Family Passionist Retreat Center? It’s open free to anyone. Whenever I’ve lost myself in its twists—aimlessly aiming for the moon gate at its center—it’s been mine alone, save for the songbirds, the whistle of budding branches.

I’m reminded of the benefits of sharing when I meet my West Hartford–based friend Jeannette at DORO Marketplace on a sunny April morning, and we select eight handcrafted French-butter pastries including a filled, glazed, nut-sprinkled pistachio croissant puffy enough to fill me all day. On the patio, dressed with lush plants from Moscarillo’s, we chat with DORO Restaurant Group owners Dorjan and Mira Puka: Albanian immigrants

who’ve helped internationalize West Hartford Center with their Treva (Italian), Àvert (French), and Zohara (Mediterranean) restaurants. As our conversation meanders from the extraordinary food scene to the uniqueness of this community—where art, education, and history are revered, businesses collaborate, and being outdoors is central to life—it’s clear I can’t keep WeHa under wraps.

Just where to send you, though, when in West Hartford Center alone you’ll also find top-notch Afghan, American, Caribbean, Chinese, Japanese, Mexican, steak, and seafood restaurants? Jeannette and I contemplate this at celebrity-chef-owned Sparrow Pizza Bar, where toppings like ramps and pesto are splashed to the outer edges of crispy pies. Our debate continues at the West Hartford Reservoirs, where 30 miles of trails are open to walkers, runners, and cyclists. “You’ve made me fall in love with my town all over again,” she says, as we realize for every recommendation in this guide, we have a handful more. So, visit while West Hartford’s still relatively undiscovered. And please let me know if there’s an extra seat at your table.

and a spa that spoils guests and locals, you could spend all weekend luxuriating here, even though chauffeured tours are available and all of Blue Back Square and West Hartford Center is on your doorstep. delamar.com

PLAY

Elizabeth Park: Known for its roses, this late-19th-century landscape on West Hartford’s eastern edge fires up its cavalcade of color earlier than you might expect. A fragrant and photogenic greenhouse show in March is followed by unimaginable deals on unique and heirloom bulbs. By late April, more than 10,000 tulips shimmer and shine. elizabeth parkct.org

Noah Webster House: Tablet tours allow you to dive as deeply as you’d like into the history and stories that reverberate through the house where “America’s Schoolmaster” grew up. Purchase West Hartford–themed gifts, and support programming for all ages including poetry readings and Life on the Farm demonstrations. noah websterhouse.org

SHOP

Moscarillo’s Garden

Shoppe: Whatever weather spring may bring, you’ll feel sunny and light on a walk through the immense greenhouse at this fifthgeneration-owned plant emporium near Bishops Corner. moscarillos.com

CHERRY

BLOSSOM CELEBRATION,New Haven. Back in 1973, New Haven’s parks department planted 72 Japanese flowering cherry trees in Wooster Square Park. The trees’ bounty of pale-pink blossoms emerges over the course of two weeks in April, an abundance marked by the Historic Wooster

Square Association’s annual community event featuring music and food vendors. 4/14; historicwoostersquare.org

COLORBLENDS HOUSE & SPRING GARDEN, Bridgeport. A 1903 Colonial Revival mansion in the city’s historic Stratfield district is the backdrop for a half-acre garden featuring nearly 100,000 bulbs:

tulips, daffodils, crocuses, narcissus, and many more spring-flowering favorites. The garden, created by Dutch floral landscaper Jacqueline van der Kloet, was designed to inspire home gardeners, who are invited to stroll the property and tour the house and art gallery when blooms appear in early April. Check website for details; colorblendsspringgarden.com

DENISON HOMESTEAD DAFFODIL DAY, Mystic. Mystic’s 1654 Denison Homestead hosts this celebration of the surrounding nature center’s thousands of daffodils. Look for tours of the 1717 Pequotsepos Manor and its gardens, demonstrations of open-hearth cooking, and children’s activities including crafts and a scavenger hunt. Check website for details; denisonhomestead.org

FLAMIG FARM, Simsbury. April marks a new season at the family-owned Flamig

Farm and its petting zoo, where kids can meet critters ranging from the familiar—horses, cows, sheep, etc.—to exotics such as peacocks and emus. On weekends, the farm’s ponies are saddled up for rides. Want to linger? Reserve a couple of nights at Flamig’s Airbnb accommodations, and join in the life of the farm. Reopening date 4/1 (weather permitting); flamigfarm.com

GREENFIELD HILL DOGWOOD FESTIVAL, Fairfield . The gorgeous dogwood blossoms gracing the grounds of Greenfield Hill Congregational Church have inspired a spring festival since 1936. Highlights include live music, craft vendors, baked goods, plant sales, a history walking tour, and of course the festival’s inspiration, once described by Eleanor Roosevelt after a 1938 visit as “an avenue of pink and white dogwood such as I have never seen anywhere else in this country.” 5/11–5/12; greenfieldhillchurch.com

MAY MARKET AT HILL-STEAD MUSEUM, Farmington . During the rest of the year, the main attraction at Hill-Stead is its renowned collection of Impressionist paintings. But in springtime, art competes with the museum’s 152 acres of flowers, blossoming shrubs, and natural woodlands. May Market, held on the first weekend of the month, is the perfect time to enjoy the grounds and browse the offerings of more than 40 vendors plus Mother’s Day plants and cut flowers. Dates 5/4–5/5; hillstead.org

AROOSTOOK COUNTY FIDDLEHEAD

FESTIVAL, Presque Isle. Fiddleheads— those tightly curled, bright green ferns freshly popped up from the damp spring earth—are a popular foragers’ quarry in Aroostook County. They’re also the centerpiece of this annual festival featuring a fiddlehead cooking contest for both amateurs and professionals, a craft fair, live music, and fiddlehead picking at a designated spot where the tasty morsels grow. 5/18; visitaroostook.com

DOWN EAST BIRDING FESTIVAL, Trescott

Migrating birds visit the diverse habitats of the Cobscook Bay region in late May, giving birders the chance to observe and identify some 300 species. Participants at the Cobscook Institute event comb fresh and saltwater

PHOTO BY MAAIKE BERNSTROM

PHOTO BY MAAIKE BERNSTROM

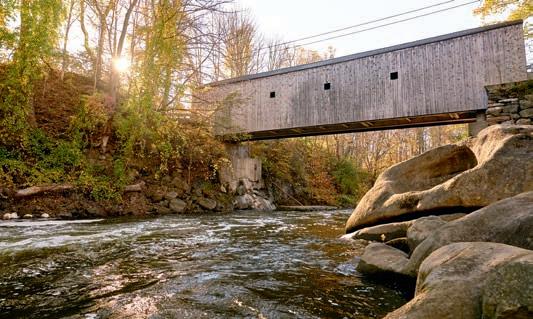

Whether you’re looking to settle into a new home or just a new daydream, our favorite New England towns and small cities are calling your name.

I wonder what it would be like to live there. To settle in, make a friend or two, wander around until the streets become familiar. Until it feels, well, like home. The sense of knowing what makes our own best place to live is elusive. Finding somewhere to love, to grow with, to enjoy remains one of life’s great rewards. But getting there often means going on a search, and being open to a new experience.

If you have been feeling that tug—even just a bit—to look around, the following pages are meant to pique your curiosity, to crack open the door. We put them together by asking our editors and trusted writers what their own best town would be, knowing all the while that one person’s choice is unlikely to be another’s. If you love outdoor adventure, New England holds its own with any other region. But you may yearn instead for tranquil ocean waves, or for cities that excite you with shows and exhibits and more places to dine than days in a year. You may be drawn to a town settled in the 17th century, with homes that look as if they grew from the soil and where history is in the air. Or you may desire a sense of wilderness and solitude on your doorstep.

About Our Numbers: Median home prices are for the first three quarters of 2023; populations are from the 2020 U.S. census.

We also understand the reality of 2024: One may simply hope to find a place to live without taking on crushing debt. It’s true we cannot talk about any place without considering what “affordable” means now. Throughout New England, median home prices these days hover near $400,000, a sum that only a decade ago would have seemed outrageous. The region, and the country, needs a staggering number of new homes—and the tension between knowing that and creating them will likely divide residents of many towns for years to come. But here, at least, we can shed light on some places that may surprise you with what “affordable” can offer.

This “Best Places” feature was great fun to create, as we, too, went on an odyssey to find and select our favorites. And in fact, we could have named 10 times as many worthy towns. That is the region’s gift to all of us. —Mel

AllenPS: No doubt many of you have “Best Places” picks of your own. We’d love to know not only the “where,” but also the “why.” Email us at editors@yankeepub.com or drop us a line at P.O. Box 520, Dublin, NH 03444.

MORE ONLINE! After you’ve gotten the bird’s-eye view of our “Best Places to Live” towns, discover our editors’ picks for places to eat and things to do: newengland.com/best-places

Tknown beyond Rhode Island. Just 20 minutes southeast of Providence, Warren retains its small-town feel while boasting a lineup of restaurants that hits every cuisine and price point. At the affordable end, you’ll find homey diner classics at Rod’s Grille, fish and chips at Amaral’s, and a time capsule of a soda fountain at Delekta Pharmacy, where a one-scoop coffee cabinet is the local go-to. There’s a cheese shop (Wedge), an excellent pasta shop (Prica Farina), a cidery (Sowams), a brewpub (The Guild), and a terrific coffee shop (Coffee Depot). The only missing element is a great bread bakery, but we see that Bywater, a sophisticated farm-and-sea-to-table restaurant, has just added a cozy bakeshop/café.

at said, the best thing about Warren’s food scene is that it’s still young and a ordable enough to allow for quirky hybrids, such as Arc{hive}, a bookstore/bar/ small-plates eatery, and the Galactic eatre, a music venue/micro-cinema/bar. Added to these are eclectic restaurants like the Southern-accented Hunky Dory, creative-coastal Waterdog, and artful Metacom Kitchen, where Jacques Pépin was a recent guest. ere’s even a food incubator, Hope & Main, that has launched businesses including Yankee Food Award winner Anchor To ee. Come to think of it, why would those of us who love food live anywhere but here? —

Amy TraversoWORTHY ALTERNATIVE:

BRISTOL, VT

This tiny hamlet punches above its weight with offerings that include Minifactory, a café/market where Yankee Food Awards honoree V Smiley makes her extraordinary jams; The Tillerman, an inn whose restaurant centers on woodfired cooking; and the new Smoke and Lola’s, which turns out next-level comfort food. Don’t miss the Bicycle Mill Baking Co., which mills its own flour with bicycle power. Pop. 3,782; median home $382,500

AFFORDABLE OPTION: BATH, ME

Get your foot in the door now, folks: From the local bivalves and natural wine at the woman-owned OystHers Raw Bar & Bubbly, to the heavenly baked goods at Solo Pane, to the retro pleasures of deli/scoop shop The Fountain, this famous shipbuilding town is now on the foodie map. Pop. 8,766; median home $350,000

While other New England towns also draw an outdoorsy crowd, few can boast the variety of attractions and ease of access as North Conway, a village within the town of Conway and one of the most storied mountain destinations on the East Coast. Popular in the 19th century among hikers who strove to reach Mount Washington’s Tip Top House and landscape artists seeking to capture the grandeur of the White Mountains, North Conway cemented itself as the year-round capital of outdoor recreation when Hannes Schneider, an Austrian ski instructor, fled the Nazis in 1939 and settled in the valley. His ski school at Cranmore Mountain, just a few blocks from downtown, helped create an Alpine culture that brought vacationers in droves.

Ask a local what makes North Conway special today, and they’ll likely cite the sheer diversity of outdoor adventures found in and around the village. Novice hikers can trek Black Cap’s 2.3-mile trail, while elite climbers can tackle some of the most di cult ice routes in North America. ere’s mountain biking, gravel cycling, and whitewater kayaking, too, not to mention rst-class cross-country skiing at nearby Jackson XC [pictured above]. Whatever adventure you choose—and wherever you decide to grab your après burger and beer—you will understand as soon as you arrive why North Conway gets people’s hearts pumping. —

Michael Wejchert

AWORTHY ALTERNATIVE: BURKE, VT

The action here centers on the village of East Burke, home to the mountain biking mecca Kingdom Trails as well as Burke Mountain, whose ski academy helped train future Olympians such as Mikaela Shiffrin. Swimmers and sunbathers will rejoice in stunning fjord-like Lake Willoughby, half an hour away. Pop. 1,651; median home $525,000

AFFORDABLE OPTION: MILLINOCKET, ME

Having struggled after its paper mills closed, Millinocket is reemerging as a four-season gateway to “forever wild” Baxter State Park, while hosting a popular marathon and new maker spaces right in town. Seeing Mount Katahdin every day provides adventurers with both inspiration and motivation. Pop. 4,114; median home $122,000

breeze ruffles Marblehead’s harbor, having sailed in from across the world. Colorful houses grow mellow in the dusk as vintagestyle streetlamps glow. A few blocks beyond the section known as Old Town, restaurant stovetops are fired up and diners settle in. e houses look on, their historic markers reminding us that they’re here, too: Ambrose Gale, Fisherman, 1663; Mrs. Ruth Morse, Widow, 1750. Seafarers, shoremen, chandlers, and bakers. With so many vintage structures—300 or so—packed together so tightly, you can glimpse a cross-section of centuries at every turn. e town sits

comfortably in its deep drifts of coastal history.

Sooner or later you’ll stumble across a yacht club here (there are at least six), but maybe that’s mandatory in a North Shore town set on a beautiful harbor just 17 miles from Boston. A quick scramble up the hill at Crocker Park, with its broad water views, con rms why Marblehead touts itself as America’s yachting capital, as well as the birthplace of the nation’s navy.

Duck inside F.L. Woods, a Marblehead institution since 1938, where sailors and aspirational landlubbers can pick up a mariner’s jacket or the latest Eldridge Tide and Pilot Book. Peruse new and classic titles at the excellent Saltwater Bookstore, and get a

WORTHY ALTERNATIVE: WESTERLY, RI

Miles of powdery beaches. A historic downtown and its green centerpiece, Wilcox Park. Star chef Jeanie Roland’s Ella’s Food & Drink. Grey Sail Brewing. All this creates a small-town feel wrapped in coastal beauty that has attracted the likes of Taylor Swift. Toss in the tiny village of Watch Hill and its lovely Napatree Point Conservation Area, and you have reason enough to sing. Pop. 18,423; median home $515,000

AFFORDABLE OPTION: EASTPORT, ME

The easternmost town in the country attracts those who prefer the timeless purr of fishing boats to traffic, shopping centers, and cineplexes. The downtown holds handsome brick buildings and an art institute, and here an ethic of preservation and nature conservation runs deep. Pop. 1,288; median home $214,000

seafood x with a tuna melt or poke wrap from Shubie’s Marketplace. And for a reminder of the mainland’s charms, please, oh please, duck into the ower shop Flores Mantilla, where Buddhas and birdbaths disappear into drifts of greenery. —Annie

Graves➜ POP. 4,484 | MEDIAN HOME $602,000

The best places often catch us by surprise with the mix of their ingredients. Settled in 1761, Manchester Village offers low-key elegance, “cottages” of every era, and white marble sidewalks. Then adjacent Manchester Center kicks in, with its designer outlets and lively independent shops such as Northshire Bookstore, whose 10,000-square-foot sprawl includes a vast collection of used and rare finds.

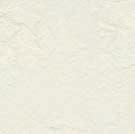

Just a few minutes from the streets of downtown is the serene Southern Vermont Arts Center, where sculptures dance through elds and forest, and art- lled walls enliven a historic mansion. ere are workshops to sample, performances at the Arkell Pavilion, and sophisticated dining at the on-site restaurant. In summer, the hills are alive with the sounds of the

Manchester Music Festival, now in its 50th year of classical music performances, talks, and master classes.

Manchester’s culture goes hand in hand with its outdoor beauty. e legendary Battenkill River has challenged shermen for decades—not surprisingly, Orvis was founded here in 1856—and the American Museum of Fly Fishing illustrates the ner points of the sport, with lures appearing as tiny works of art. Abraham Lincoln’s son Robert was so dazzled by the landscape that he built his summer mansion, Hildene, here in 1905; it’s now a must-see house museum. And then there’s the natural masterpiece of Mount Equinox, at 3,848 feet, looming over all; ascend via the Skyline Drive to enjoy its breathtaking views, courtesy of the silent Carthusian monks who own it. —A.G.

WORTHY ALTERNATIVE: RIDGEFIELD, CT

What do Roz Chast, Eugene O’Neill, and Maurice Sendak have in common? They’re all among the creatives who’ve lived in this picturesque culture hub less than 60 miles from Times Square. And the arts keep coming, with community and professional theater, an art museum, a history museum, and an orchestra, too. Pop. 7,228; median home $1.05M

AFFORDABLE OPTION: NORTH ADAMS, MA

The arts scene in this former mill town gets a spectacular boost from Mass MoCA, the largest contemporary art museum in the country. There are also local galleries and artists’ lofts and the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts; meanwhile, nearby Mount Greylock and Natural Bridge State Park are testaments to nature’s artistry. Pop. 12,961; median home $179,950

Haverhill, MA, offers a portrait of a city on the verge.

Haverhill was once a monument of New England industry, with a busy commercial district and imposing brick mills along the Merrimack and Little rivers. But when those factories shuttered, the onetime “Queen Slipper City” saw its downtown languish and its manufacturing infrastructure descend into abandoned, graffitied disrepair.

Now, after decades on the cusp of a renaissance, Haverhill is ready to reclaim some of its former luster with a project that uses the past to look toward the future. The preservation organization Historic New England is embarking on a visionary effort to transform a gritty three-acre swath of downtown into a cultural destination spotlighting New England history.

Dubbed the Historic New England Center for Preservation and Collections, it will feature a visitor center and exhibition space showcasing some of Historic New England’s 125,000-piece collection of clothing, shoes, jewelry, furniture, paintings, wallpaper, housewares, and other objects, along with selections from its 1.5 million archival documents. The center will be more than just a museum or artifact repository, though: The multiyear, $150-millionplus project could also include housing, retail, a hotel, a theater, a public green space, and artist and maker spaces.

—Alexandra PecciNEW LONDON, CT: New London is poised for a maritime-driven boom, thanks to a $300 million state pier redevelopment, an offshore wind turbine project, and the in-progress National Coast Guard Museum. Look for downtown revitalization to come along for the ride.

WATERVILLE, ME: Colby College has led downtown Waterville’s revival, with two new arts centers, beautification projects, improved traffic patterns, and the city’s first hotel in more than 100 years. Next up? New housing and commercial space in once-abandoned mill buildings.

To see how town and gown fit together in Brunswick, begin at the historic mill complex Fort Andross and walk one mile south on Maine Street to Bowdoin College. Within a few blocks are two Indian restaurants, plus gelato and brick-oven pizza, homemade pasta, Japanese and Greek cuisine, and Maine seafood. One could dine out on Maine Street every day. Except—you’ll also want to cook at home with the local bounty of Brunswick’s summer and winter farmers’ markets.

Step inside Gulf of Maine Books and chat with poet-owner Gary Lawless, whose store has been a xture since the 1970s and whose displays favor banned books. A bit farther along is Pleasant Street; turn here to nd the wall mural Dance of Two Cultures. Christopher Card’s painting showcases the people and heritage of Brunswick and its sister city of Trinidad, Cuba; looking at it, you will feel this town’s embrace of inclusivity and multiculturalism.

Heading back to Maine Street, you’ll want to linger at the town green, which stays vibrant even in winter with its outdoor skating rink. e green ows to Bowdoin College and one of the most beautiful campuses in the country. Look around. Sit by trees planted before Hawthorne and Longfellow studied here. Explore the museums.

en, after downtown Brunswick has won your heart, take a short drive to the Harpswell Peninsula. And as you soak in its ocean views, you may wonder: With all this, why would any student ever want to graduate? —

Mel AllenHollywood’s ideal college town would look just like this: streets lined with little shops and eateries that lead to a stately campus ringed by red brick buildings. Hanover also throws in a river for kayaking, a ski hill, an art museum, and access to the Appalachian Trail. Pop. 11,870; median home $1.13M

When U.S. News & World Report put the University of Maine at Farmington in its top 10 for “best value” last year, it focused on UMF’s academics and in-state cost of only $10,989. Yet one should also factor in proximity to lakes and major ski resorts, upscale pubs and cafés, and a festival honoring native son and earmuff inventor Chester Greenwood. Pop. 7,592; median home $242,500

➜ POP. 7,172 | MEDIAN HOME $505,000

Support of local farmers is fierce in Great Barrington, a culinary cradle in the Housatonic River Valley. Indeed, in this small town named one of America’s best by Smithsonian magazine, a closer look confirms a conscious commitment at every level of eating and drinking. Restaurants raise their own meats and produce. Barrington Brewery makes its beer with solar power. SoCo Creamery sources dairy for its ice cream from a family farm (and makes its own cookie dough, to boot).