6 minute read

Weather: with Simon Rowell, Rowell Yacht Services

CONTRIBUTED BY SIMON ROWELL, ROWELL YACHTING SERVICES

The Round the Island Race in 2019 was a classic change of systems race, with one wind for the start, a changeover period then a new wind for the finish – in other words ripe for a long period of light winds to tempt you to retire. When you have two separate systems driving your weather it’s even more important to not just read the numbers off the forecast but to try and understand how the weather is coming in and what physical signs you’ll see.

Advertisement

The forecast chart (Figure 1) shows the big picture, with the morning and early afternoon dominated by the generally E flow off the departing high moving into the North Sea, and the later SSW breeze driven by the next low coming in from the Atlantic. The tricky bit is what happens in between these two systems.

Theyr provided a high resolution forecast for the event (Figure 2), and the model run issued the day before illustrated the change in wind regime well. The changeover from the dying SE into the gradually building SW coming up the Channel is clearly shown.

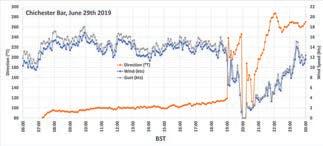

The wind station at Chichester Bar (Figure 3) shows that the forecast was pretty good – the ESE breeze died off at 1900 BST, was light and variable for an hour or so, then gradually built back in from the S veering W.

Later on: To start off with: • Low pressure driven, light • High pressure driven, to modrate SW/W/WNW moderate E/ESE • Sunny, 24-26°C

Figure 1: Met Office forecast chart for 1300BST, July 29th 2019. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v1.0

Figure 2: 0.08° Theyr forecast for 1800 BST on Race Day, issued at 1800 UTC the previous day.

Figure 3: wind at Chichester Bar - the new breeze started to come in around 1900 BST Data provided by the Solentmet Support Group

So – given that the forecast clearly showed two different wind regimes with a likely light patch in between, how do we make use of this during the day without spending too much time on it? The thing to do is to translate what the charts and the forecast numbers say into what is likely to happen in practice, and to do this system by system.

Looking at the morning breeze, driven by the high moving off into the North Sea, this ESE breeze was basically coming up the Channel off Europe with no fronts or anything else there. This means that the air will be quite dry and mostly cloud-free. The Channel isn’t really enough water to allow clouds to form in air coming off the dry and hot Continent. The day was forecast to start clear and warm and continue clear, getting very hot – and it did so. The Island itself will heat up quickly in these conditions, causing air to rise above it and effectively bubble up – this tends to cause the air flowing on to the Island to be pushed up, creating a very patchy and shifty zone close in to the land. This zone increases as the land heats up during the early afternoon. So while the ESE was in then, it was prudent to plan on going a little further offshore round the back of the Island to keep the best of the breeze. The boats that went inshore did get some benefit from the stronger tide in places, but this wasn’t enough to make up for the onshore breeze effectively being pushed up away from the surface by the air bubbling up off the hot Island surfaces.

The next bit is the “in between bit” – which judging by the tiny pressure gradient shown on the isobars of the synoptic chart (Figure 1) is likely to be really light. There’s not a lot you can do about this expect to really make sure you know where to find the tide, and to take advantage of any light puffs that may come down. This is probably the most uncertain part of the day, because a small difference between the actual and predicted paths of the low will make a big difference to the wind on the surface. By big, I mean 5 kts of wind instead of 2 kts – basically, if you assume that there’s going to be very little wind from all around the compass and just react to what you get as effectively as you can, then that’s about as good as it gets. This is not the time to go by the forecast numbers!

Then there’s the incoming low with the long-awaited new wind. As it’s a low coming in from the Atlantic there will be a lot more moisture in the air, and you can expect clouds to herald the new wind. Generally ahead of a low you will see high cirrus clouds, then a progression of lower and increasingly substantial ones. These will come in ahead of the surface wind, but at least you know the breeze is on the way. With the forecast S/SSW/SW wind direction this meant that it was going to come over the Island for much of the fleet, but later on in the afternoon as the land was cooling down. This meant that while there’d still be the same problem of the hot land effectively preventing the wind from reaching the sea as the afternoon cooled into the evening the new wind would eventually mix down to the surface.

This is what happened. One of the boats that year was an E-boat entered by the Greig City Academy sailors, crewed by one of the youngest crews in the race. They had thought about what they’d see as the weather changed, and they carried on going through the light and variable stage, happy that because they could see the clouds coming in from the SW the new wind was on the way (Figure 4). They finished just 12 minutes after the time limit sadly, but they did finish, and had a great day on the water for it. The benefit of the boys (Azat, Seun and Samuel) persisting didn’t really become clear

until weeks later. Unknown to them, just behind them, a Folk boat with Ross Appleby had also continued, waiting for the wind shift to come in. He was so

Image: Jon Holt impressed by their Figure 4: GCA boat sailing well in the new wind just perseverance that as before sunset, with the incoming clouds showing what’s a result, helmsman happening. Seun was invited to sail on Scarlett Oyster which went to on to win the ARC later that year. The main thing was this was learning at its best. Having studied the weather the night before they saw it play out for them the day after, learning in the best way possible what a ‘heads out of the boat day’ is all about. The overall ethos then is to look carefully at the forecast and go through what it will mean for you on the water, in terms of what you’re likely to see. Then think carefully about any nearby land and how the changing temperature of that will affect the surface wind through the day. If you have more than one weather system to deal with then deal with each of them in turn, and pay close attention to what may go on in the transition period – this is when the forecast is likely to be weakest, and you need to keep your head out of the boat even more than usual. And then have a great day’s sailing!