Nature, Infrastructure, and City-making: Houston and Buffalo Bayou

HIS 4374: Cities, Infrastructures, and Politics: From Renaissance to Smart Technologies

Spring 2023

Yimeng DingIntroduction: Cities and Infrastructure

With the deterioration of infrastructure and the surge of environmental disasters, in the past decades we found ourselves caught in the desperate state of crisis In the United States, since the neoliberal governance from Ronald Regan, disinvestment in infrastructure has led to significant shortage in maintenance compared with the rate of deterioration1. The astonishing web of infrastructure that enabled the conquer of the wild and the construction of the cities since the 19th century - railway, electricity lines, pipelines and highways - has undergone numerous failures which challenged our confidence in their competence in serving human settlements.

Yet cities’ relationship with nature has always been that of a constant contestation. Geographer Maria Kaika’s Promethean Project of Modernity theory locates our current “crisis” state with nature to be the third phase since the modernization movement. Phase one began with the problematization and recapture of urban nature. In the 19th century, the horrid

conditions of industrialized English cities led to both environmental decline and social disorder. In line with the rise of modernization process and urban order, social elites responded to the urban blight by concluding “it was the nature of the city and not that of society that needed to change”. Urban nature was sanitized, purified with air and foliage to the nostalgic image of a “wild nature” with parks and later garden cities in hope to achieve social harmony. The second phase lasted from the end of the 19th century to the later half of the 20th century. The nature/city divide remains, but the natural city was considered “a thing of the past” and must be substituted by cities constructed with the rational guidance of modern technology and machines. With the heavy influence of automobiles, this phase concluded with the booming of infrastructure construction. The third phase began as the environmental movement fully channeled the problem of modern planning of nature in the 1960s and 70s until today. The cities’ everincreasing demand for material is caught in between environmental disaster and infrastructure failure. As Andrew Karvonen pointed out, all these factors rendered the

previous efforts in taming nature failure, and nature now is a source of crisis for the cities.2

The crisis perspective has also led to reflections on considering the growth as a default: That is, if there is economic and social need for the city to develop, then the city will develop. The environmental condition which the cities are located in has become a growingly important factor in the discussion - Should cities continue to grow and expand if the environmental condition does not permit it? Should we be able to alter any environment for human settlement? Emerging megapolis in Arizona such as Phoenix have been subjects of such debates: Given that the existing water supply is nowhere near sufficient with the cities’ fast growing population, and the only way to sustain the growth is through tremendous, expensive and arguably not-so-sustainable water infrastructure, why should the cities continue to advertise more people to live in the desert?3

The booming desert cities are not the only ones challenged by the complex relationship

of cities, nature, and infrastructure. Houston is a case where, regardless, the city has been constructed on essentially a floodplain and it anticipates continuous growth despite the growing threat of extreme flooding from its major river, Buffalo Bayou, as well as the seaport, Galveston Bay. Based on the theoretical framework established above, I argue that the ways in which Houstonians approach their water bodies have always been based on that of the modernist controlling and containing. Despite the drastic change in aesthetic and technology, the infrastructure interventions to the natural water way have always been highly engineered. The so-called “reparative flood infrastructure” in restoring the waterway to its natural state rather engineered the landscape, vegetation, recreational system, and monitoring technology to a state of “hyper-natural” - A mimicry of nature in its natural state with complex engineering behind it.

Moreover, the contemporary approach also changes the social relationships between people and water infrastructure: Water infrastructure has gone from a negative

obstruction to a positive asset in Houston. What remains is the patchwork distribution of the infrastructure that leads to the disintegration of the city with or without it. The issue of governance which leads to such disintegration is also worthy of discussion: Who funds the water infrastructure, and who benefits from it? A clear, unbiased and comprehensive planning at regional scale for efficient water infrastructure is still, and even more missing from the city’s table.

A Wet City: Buffalo Bayou, Steamboats, and Houston

Throughout its history, Houston and its port have been at the intersection of technology and geography.

Mark Lardas, in Port of Houston - The Images of America

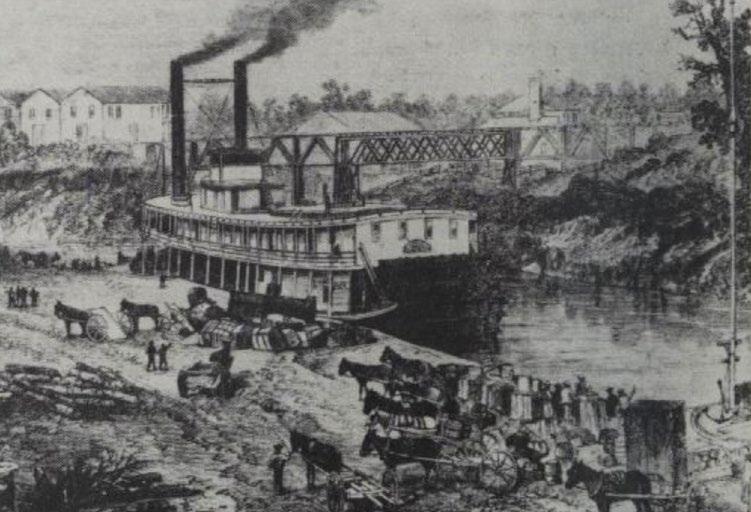

Contrary to its current reputation as the American petroleum and aerospace center, the city of Houston was first conceived given the commercial and trade premise of one of Texas’s largest watersheds, Buffalo Bayou. Flowing east to west through large territories of Texas, the bayou is definitive in the formation of riparian ecology of Texas, while connecting inland Texas to Galveston Bay and also the Pacific. With the abundance of water supporting the growth of riparian flora and fauna, the Buffalo Bayou has

been a lush hunting ground for Indigenous population, centuries before European settlements. In 1836, August and John Allen drifted down Buffalo Bayou and ended up at what is now Downtown Houston and initiated the construction of a port city.

What is counter-intuitive in the Allen brothers’ decision is that the location was not at the head of navigation on Buffalo Bayou and the narrow, winding waterways in Houston were not naturally good for navigation. Thus, the cleaning, dredging, and widening of waterways almost began simultaneously with the city’s birth - not to turn the riverside an emancipatory and healing site from the deteriorating urban core, but to make the bayou productive for transportation from the heart of Texas to Galveston bay. This also explains the early years of water engineering focusing downstream near its estuary for the obvious reason of oceanic transportation. Despite having suffered from numerous flooding downtown, Houstonian reacted to the floods by moving the location of the port to move inland instead of doing any precautionary works upstream.

A crucial influence on the engineering of Buffalo Bayou in this period was the advancement of naval technology. Despite railroads playing an increasingly important

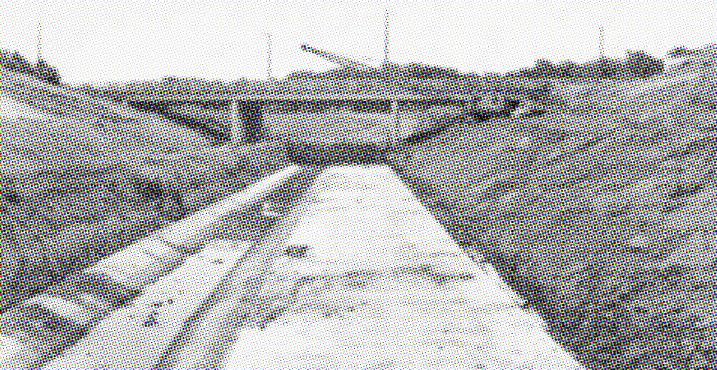

Channelized waterway in Houston since the 1950s. Image from Images of America, Port of Houston

role in Houston’s development by the turn of the 19th century, water transportation along Buffalo Bayou remained Houston’s most important link to the outside until the postCivil war era. When the Allen brothers first promoted their city to leading citizens, they organized a steamboat trip with the smallest boat possible - Laura, otherwise the boat would have been snagged by the tree trunks in shallow water. Furthermore throughout the 19th century, the trade route along Buffalo Bayou was dominated by Charles Morgan’s steamboat company which by the 1870s almost monopolized the waterway by taking control of the Buffalo Bayou Ship Channel Company. With the growing size of steamboats and the engineering of waterways going hand in hand, the waterway from Houston to Galveston was dredged to 12-foot deep, accommodating the oceangoing ships with a 14-feet draft. In 1897, the US Army Corps proposed dredging a 150-foot wide, 25-foot deep channel at Galveston Bay, a construction estimated at $4 million with $100,000 annual maintenance cost from the Congress. Work began in 1903 with an initial plan of dredging to 18.5 -foot deep, but later the completion of Panama Canal pushed the number to 25-foot in order to better accommodate oceangoing ships. In 1914, the last piece of port city - the deepwater port of Houston, was dredged, and Houston became the “perennial boom town of 20th century Texas”.4

The political drive for the waterway engineering was a combination of public and private effort in harnessing its connectivity. Private companies, such as Charles Morgan’s Ship Channel Company and Houston Cotton Exchange, usually initiated dredge and channel construction for navigation of their own trade. Where trade provision fell short the public sector kicked in to complete the connection. In the 1880s when Morgan’s construction waned, the US Army Corps of Engineer took over

and completed a series of federal projects on waterway channelization and port construction, including the Houston Ship Channel and Galveston Port that laid the foundation of Houston as a port city today.5

Changes in the Form and Perception of Water Infrastructure

But the more successful the port development was, the more economic damage a storm could do to it. In 1915, Galveston hurricane hit Houston, resulting in $1 million damage. Two storms in 1929 hit Houston back to back, and the resulting floods prompted Houston to reflect on the flooding issue seriously: How may the city continue to grow if the flooding cannot be controlled?6

In response to the devastation, Harris County Flood Control District(HCFCD) was established in 1937 as a local respondent to the US Army Corps of Engineer. The construction and governance over the infrastructure became dominantly public. In the next half a century, the engineering of Buffalo Bayou gradually shifted its focus from channel improvement to flood control, and the location of infrastructural intervention also expanded from the tributaries to the broader watershed upstream, taming the landscape at a territorial scale.

Water infrastructure constructed in the early 20th century also constructed the image of infrastructure Houston is familiar with today: Dams, reservoirs, and most notably, the concrete-lined waterways. Two reservoirs 10 miles upstream from Downtown Houston, Addicks and Barker, were constructed to control the flow volume during floods. From 1954 to the 1960s, with the Federal Flood Control Act, much of the Buffalo, White Oak, and Brays Bayous were cleared, enlarged, and straightened to allegedly increase the capacity of containing water.7

With the large-scale infrastructure construction came the severe destruction of riparian ecology. Much of the river bank along Buffalo Bayou was cleared and concrete-lined, leading to increasing environmental concern. In the 1970s, the Houston Ship Channel was deemed as “the filthiest water in the nation”, reflecting the local’s concern for water pollution.

Political campaigns against the construction of water infrastructure escalated into a “NIMBY” styled movement. In 1966, property owners near Chimney Rock Road along Buffalo Bayou - among whom Terry Hershey, who later was known as the main environmental proponent of Buffalo Bayou - were outraged by the bulldozing and rerouting of bayou in the area by US Army Corps of Engineers and activated Buffalo Bayou Preservation Association. The campaign soon developed to attract wider community activism, and reached a climax in 1975 when Terry Hershey, George H.W. Bush, and others pushed for the halt of the

infrastructure built under the flood damage reduction plan in 1954.

But the shadow of flooding did not cease with the halt on infrastructure construction. In a 1971 Congress Hearing on the effect of channelization on the environment, the director of Office of Chief Engineers of US Army Corps of Engineers, Koisch, responded in his defense:

Since completion of the reservoirs, there has fortunately been no severe storm to critically tax the downstream channel. A major storm could occur at any time, but local residents have the impression that there is no real need for the channelization of Buffalo Bayou… (And) No alternative is yet apparent which would both preserve the natural environment and provide adequate flood control.8

Buffalo Bayou has since been rendered in a state of crisis. The post-war perception of the relative stability and bounty of nature was destroyed with the rise of environmentalism.9 And it is from then

the Bayou entered Phase three in Kaika’s description of modernity’s Promethean Project, requiring new forms of water engineering and political governance.

Patchworked Nature, Patchworked City

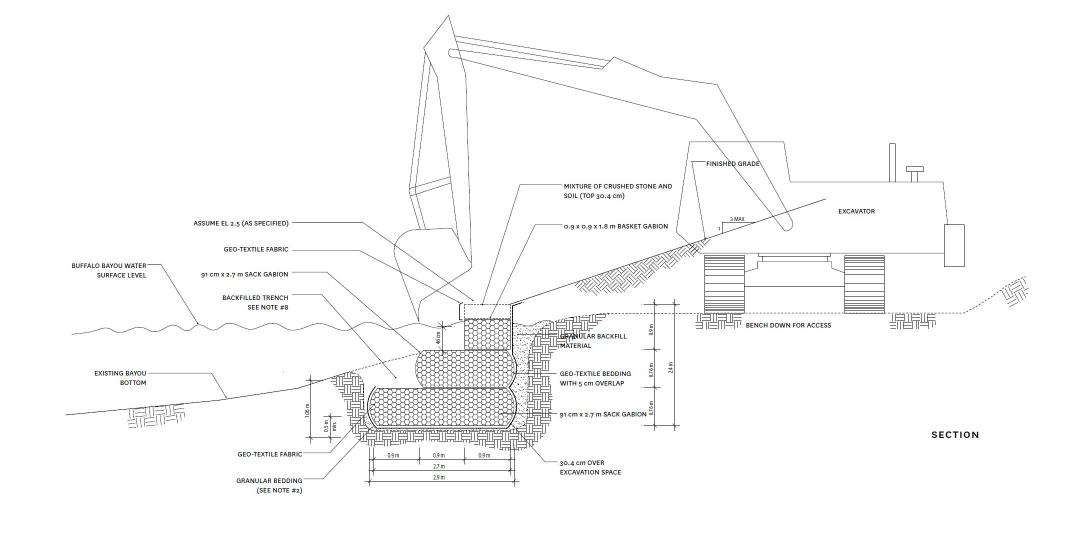

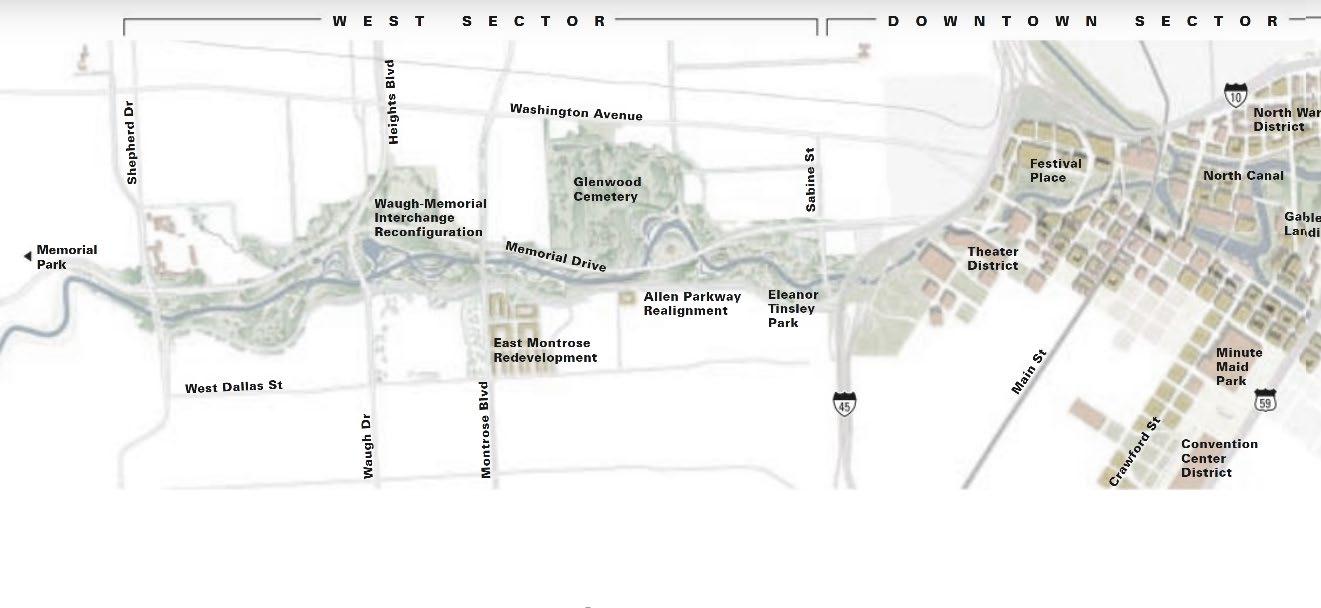

As we enter the 21st century, new forms of infrastructure attempting to “rescue” Buffalo Bayou out of its crisis state have been conceived. Downstream of the Buffalo Bayou before Houston downtown, Buffalo Bayou Park is the inaugural project to transform the urban-section waterway with the consideration of urban design, ecology, recreation-based programming, and hydrologic flood engineering.10

This signaled the shift of water infrastructure in Houston from controlling to restorative. According to the description by SWA - the designer of the park, Buffalo Bayou Park was conceived to address the bank erosion due to the severe flood history in the area that rendered the riparian ecology vulnerable. As a park itself, it is quite an extraordinary piece of landscape design with careful landscaping strategy, vegetation plantation, recreational facility design that turns an unfavorable location under highway to a green, civil corridor. But the following discussion hopes to go beyond what a single park can offer but focus on the technological and political intention upon which the contemporary relationship between nature, infrastructure and city is constructed.

In the case of technology, the bayou park, similarly as the subject of dredging and channelization in the past few decades, becomes a highly engineered object. Despite the very different perspective on flood mitigation and the method of water engineering, the goal of the current intervention is not to restore the waterway to its natural state - Otherwise the park would look like a wild-growing riparian marsh with

barely any space for recreation or view. On the contrary, the park is designed to recreate the image of a tamed nature with wide meadow, clean trails, retail pavilions, and public art. There embedded an idealized vision of nature as the protector of the city. The cleanness of the image conveyed a rather modernist message of control and organization - “Do not worry, we have flooding under control with the new park!”, which surely boosts confidence for local residents and business as well as attracting tourism with this new image of the city.

Another hidden engineered aspect of the park is its complex management system. In 2017, Hurricane Harvey hit Houston and caused historical damage. As a flood infrastructure, Buffalo Bayou park is designed to be flooded. Yet, the park would not have recovered without the significant amount of post-flooding management. In the case of Hurricane Harvey, the main challenge was the clean up of sediment that was carried downstream by the water and piled up up to 6 ft along the banks. It took a team of 15 park staff, 20 temporary staff, and more than 2000 volunteers over the course of 8 months to clean up 60 million tons of sediments, recover 500 trails, and replanted more than 1500 trees.11

The politics behind the park is an exemplary case of the changing responsibility in supplying water infrastructure from public to private. Buffalo Bayou Park was funded through a public private ownership between the City of Houston and Buffalo Bayou Partnership(BBP), who collaborated closely with private donors for funding. The total funding amount reached 75 million dollars, 50 million of which came from the private funding of the Kinder family and foundation, one of the major philanthropic groups local to Houston.12

However, these privately funded projects

require tremendous public funding in their daily operation and maintenance, depleting public resources while not allowing for reinvestment of profits in public services.13 First, the regular operation is largely funded publicly with Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone #5. Moreover in 2019, a total of $9.7 million funding from the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) will be used to contain erosion and repair riverbanks. According to BBP, these are precautionary measures to stabilize the channel and prevent future damage.14 While these works are not completely unnecessary, they are definitely expensive. Such a utility patchwork stands in stark contrast to modernity’s dream of rational and systematic planning of the city and infrastructure.

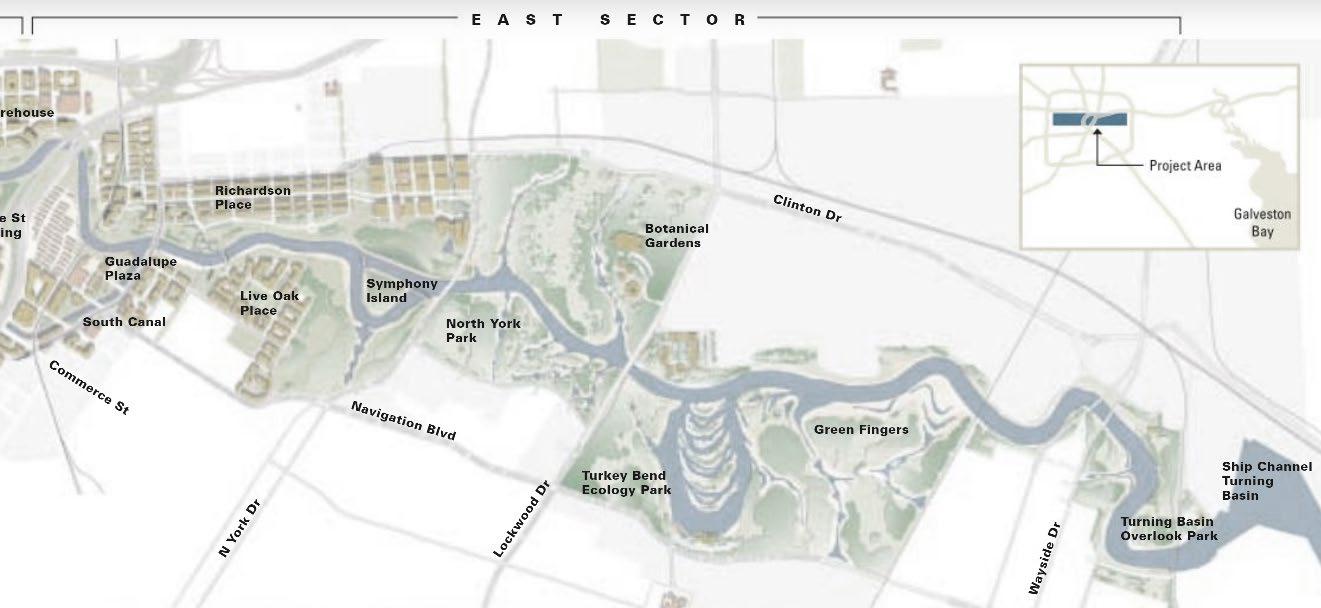

The founding source may have also explained the specific location of the park:

By prioritizing the park development west of downtown Houston, the flood infrastructure may not only alleviate the flooding for the expensive business area but also provide space for civic recreation that contribute to the tourism in Houston. On the other hand, the socially disadvantaged groups east of downtown still await their flood infrastructure, namely the Buffalo Bayou East project, to embark after decades of planning. Similarly, neighborhoods around Brays Bayou still await a comprehensive flood infrastructure planning, despite the dominantly channelized waterway imposes much more threat to urban development with riverine flooding.15 It is clear that the park is still a continuation of the 19th century elitist vision where a “fix” with urban nature can alleviate certain local problems. But it is sure to accelerate socio-ecological disintegration elsewhere.16

Conclusion

As seen in the case of Houston, the recent construction of reparative water infrastructure continued a certain modern ideology of the relationship between city and nature, while generating new technological and political organization within the city: The users and the beneficiaries of the new flood infrastructure are clearly defined by its location, and the city and the waterway may be more segregated by selective placement of the infrastructure. Continuing the research, more questions may be raised based on new infrastructure beyond the urban center, beyond the Buffalo Bayou Park: How does urbanization affect our perception and engineering of the same stream of water, beyond its physical impact on water and river bank quality? Overall, the changing relationship between water infrastructure, nature, technology, and politics of the city highlights the need for a more holistic approach to infrastructure development that takes into account the social, environmental, and economic impacts on urban and peripheral waterways. By addressing these issues, we can create a more sustainable and equitable future for all communities.

Endnotes

1 Aman and Becker. US Infrastructure : Challenges and Directions for the 21st Century, Chapter 1.

2 Andrew Karvone. “The Dilemma of Water in the City.” In Politics of Urban Runoff

3 Mark Brodie. “As Valley faces water shortage, city leaders look for new potential sources”

4 Stanley Siegel. Houston, a chronicle of the supercity on Buffalo Bayou, p55.

5 Mark Lardas. The Port of Houston, p40

6 James Sipes and Matthew Zeve. The Bayous of Houston, p33.

7 Ibid., 35.

8 Effect of Channelization on the Environment. Congressional Hearing, 1971-07-279

9 Maria Kaika. City of Flows, p20.

10 Ying-Yu Hung and Aquino Gerdo. Landscape Infrastructure: Case Studies by SWA, p44.

11 Buffalo Bayou Partnership 2017 Annual Report, p3.

12 Ariel Worthy. “Houston to expand Buffalo Bayou Park to Houston’s East End with new funding”

13 Kaika. p164.

14 Buffalo Bayou Partnership. “Harris County Flood Control District and Buffalo Bayou Partnership Making Repairs along Buffalo Bayou as part of the Hurricane Harvey Recovery Program”

15 Juan et al. “Comparing floodplain evolution in channelized and unchannelized urban watersheds in Houston, Texas.”

16 Kaika. p21.

Reference

Khan, Aman, and Klaus Becker. 2020. US Infrastructure : Challenges and Directions for the 21st Century. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kaika, Maria. 2005. City of Flows : Modernity, Nature, and the City. New York ;: London : Routledge.

Karvonen, Andrew. 2011. Politics of Urban Runoff :nature, Technology, and the Sustainable City. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Brodie, Mark. “As Valley faces water shortage, city leaders look for new potential sources” in KJZZ. January 23, 2023. https://kjzz.org/content/1836634/valley-faces-water-shortage-cityleaders-look-new-potential-sources

Siegel, Stanley, Patrick H. Butler, Gerald. Egger, and Harris County Historical Society. 1983. Houston, a Chronicle of the Supercity on Buffalo Bayou. 1st ed. Woodland Hills, Calif.: Windsor Publications.

Lardas, Mark. 2013. The Port of Houston. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing.

Sipes, James L., and Matthew K. Zeve. 2012. The Bayous of Houston. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub.

The Effect of Channelization on the Environment. Hearing, Ninety-Second Congress, First Session. July 27, 1971. 1971. District of Columbia: U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1971.

Hung, Aquino, Bélanger, Czerniak, Geuze, Robinson, Skjonsberg, et al. 2013. Landscape Infrastructure : Case Studies by SWA. 2nd. ed. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Buffalo Bayou Partnership. “Buffalo Bayou Partnership 2017 Annual Report”. https://issuu. com/buffalobayou/docs/2017_bbp_annual_report_final

Worthy, Arial. “Houston to expand Buffalo Bayou Park to Houston’s East End with new funding”. https://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/articles/news/houston/2022/09/26/433897/ city-announces-plans-to-expand-buffalo-bayou-park-to-houstons-east-end-with-newfunding/#:~:text=Houston%20Mayor%20Sylvester%20Turner%20said,be%20utilized%20 for%20Park%20projects.

Buffalo Bayou Partnership. “Harris County Flood Control District and Buffalo Bayou Partnership Making Repairs along Buffalo Bayou as part of the Hurricane Harvey Recovery Program”. https://www.buffalobayou.org/harris-county-flood-control-district-and-buffalobayou-partnership-making-repairs-along-buffalo-bayou-as-part-of-the-hurricane-harveyrecovery-program/

Juan, Anew, Avantika Gori, and Antonia Sebastian. 2020. “Comparing Floodplain Evolution in Channelized and Unchannelized Urban Watersheds in Houston, Texas.” Journal of Flood Risk Management 13 (2): n/a–n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12604.