This issue: Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

Young architects take the lead in designing a more diverse, equitable and inclusive society/industry/practice. See what impact driven initiatives, resources, and personal stories are shared.

2022 Q3 Vol. 20 Issue 03

The architecture and design journal of the Young Architects Forum

Connection

2022 Young Architects Forum Advisory Committee

2022 Chair Jessica O’Donnell, AIA

2022 Vice Chair Matt Toddy, AIA

2022 Past Chair Abi Brown, AIA

2021 - 2022 Knowledge Director Jason Takeuchi, AIA

2021 - 2022 Advocacy Director Monica Blasko, AIA

2021 - 2022 Communications Director Beresford Pratt, AIA

2022 - 2023 Community Director Sarah Woynicz-Sianozecki, AIA

2022 - 2023 Strategic Vision Director Kate Thuesen, AIA

2022 - COF Representative Kate Schwennsen, AIA

2022 - Strategic Council Liaison Karen Lu, AIA AIA Staff Liason Jonathan Tolbert, Assoc. AIA

2021 - 2022 Young Architect Regional Directors

Central States Malcolm Watkins, AIA

Florida Caribbean Trevor Boyle AIA

Northern California Olivia Asuncion, AIA

Middle Atlantic Kathlyn Badlato, AIA

New York Christopher Fagan, AIA

Pennsylvania Anastasia Markiw, AIA

Northwest and Pacific Brittany Porter, AIA Illinois Holly Harris, AIA

Gulf States Kiara Luers, AIA New Jersey Matthew Pullorak, AIA

2022-2023 Young Architect Represntatives

South Carolina Ryan Lewis, AIA

North Carolina Shawna Mabie, AIA

Kentucky Terry Zink, AIA

Arizona Jordan Kravitz, AIA

Texas Samantha Markham, AIA

Virginia Carrie Parker, AIA

Colorado Kaylyn Kirby, AIA

West Virginia Meghann Gregory, AIA

Georgia Laura Morton, AIA

Indiana Ashley Thornberry, AIA

Nevada Andrew Martin, AIA

Ohio Seth Duke, AIA

New Mexico Efren Lopez, AIA

Utah Melissa Gaddis, AIA Connecticut Brian Baril, AIA

Rhode Island Bryan Buckley, AIA New Hampshire Nathaniel St. Jean, AIA Michigan Trent Schmitz, AIA

Connection is the official quarterly publication of the Young Architects Forum of AIA.

This publication is created through the volunteer efforts of dedicated Young Architects Forum members.

Copyright 2022 by The American Insititute of Architects. All rights reserved.

Views expressed in this publication are solely those of the authors and not those of The American Institute of Architects. Copyright © of individual articles belongs to the author. All images permissions are obtained by or copyright of the author.

Connection 2

5 Editor’s note

Beresford Pratt 6 President’s message Daniel Hart 8 Chair’s message Jessica O’Donnell 10 So you want to… Build an equitable future? Kaitlyn Badlato 13 Walking the walk Abigail Brown & Laura Ewan 16 If not us, then who? Brian Baril 22 Conversations on accessibility, empathy, and implicit bias Gabriella Bermea 24 The voice of the immigrant architects community Saakshi Terway 27 Efforts in education to improve the architecture pipeline Paige Russell

30

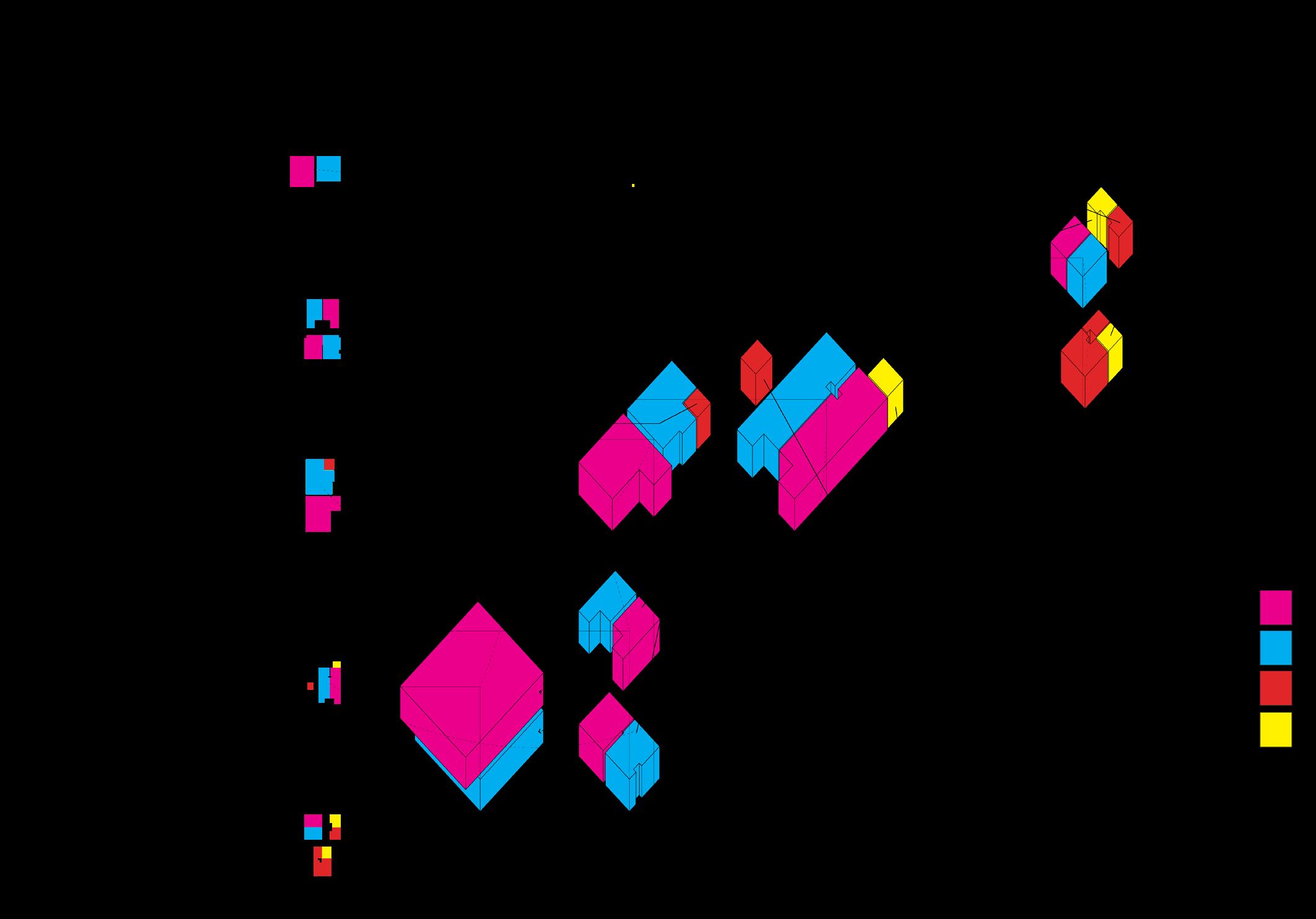

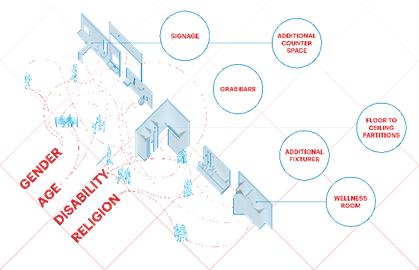

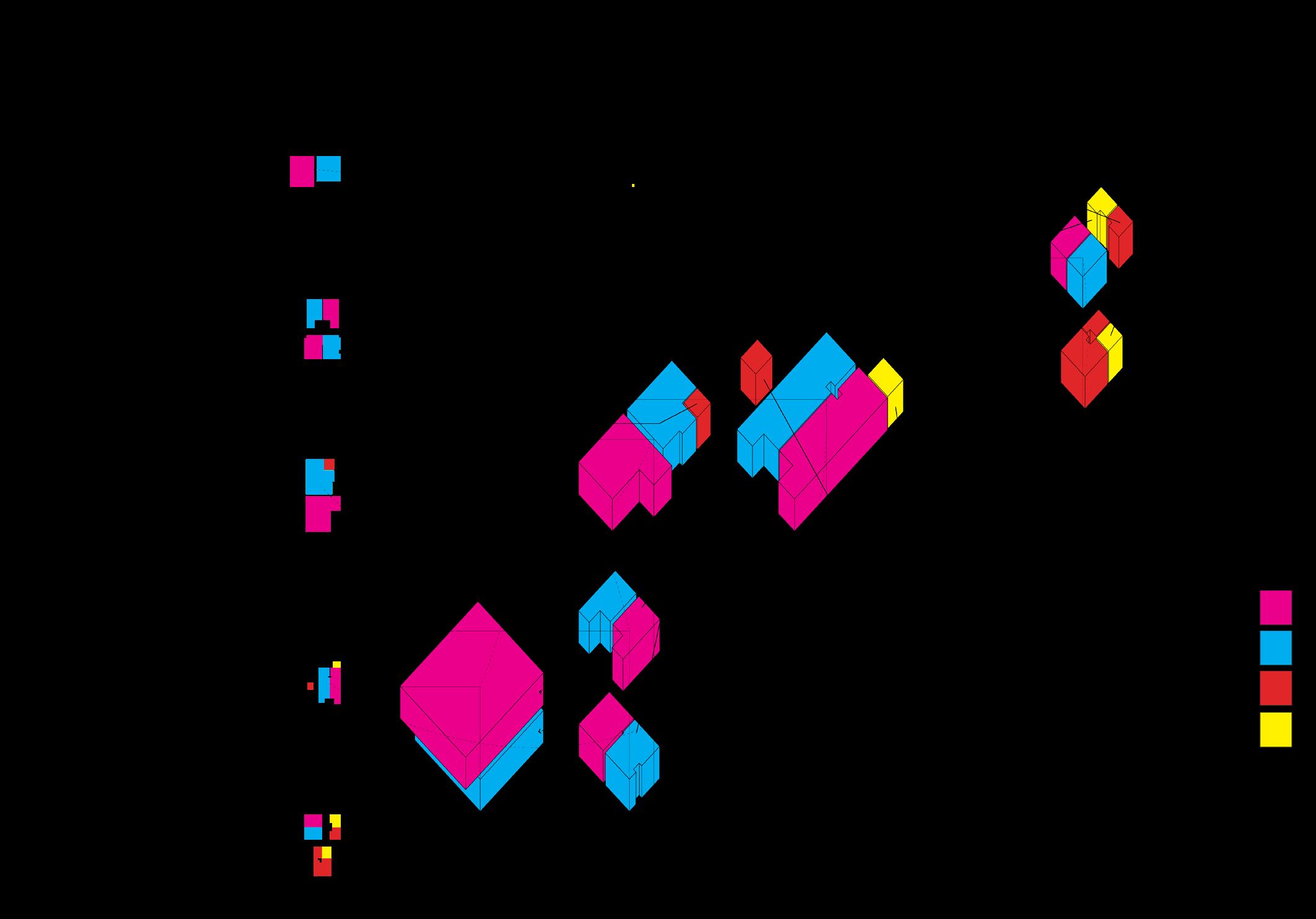

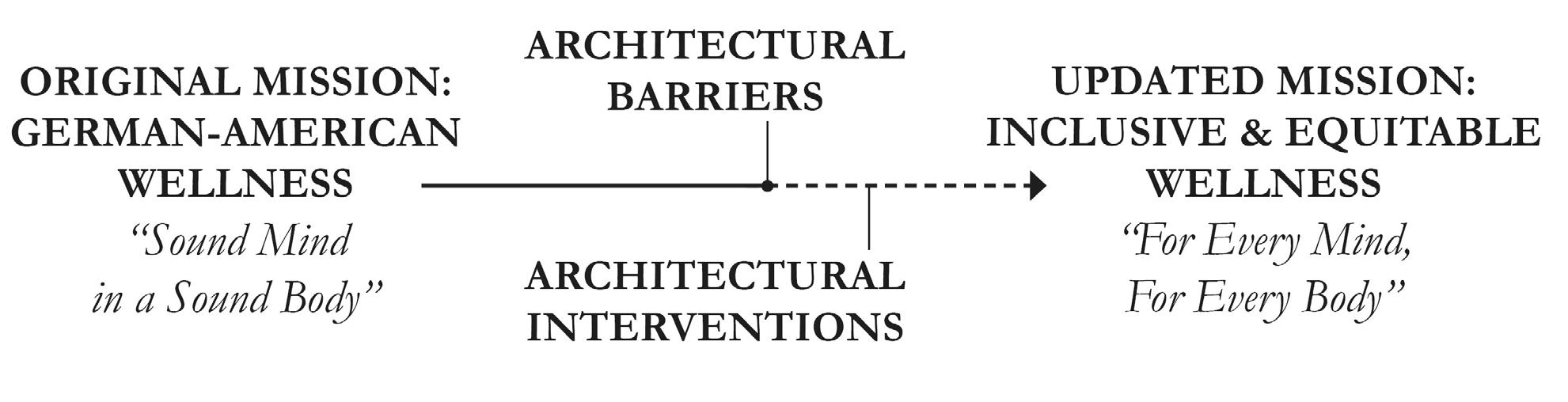

Design that affirms Dennis Dine 32

For every mind, for every body Kurt Green 36

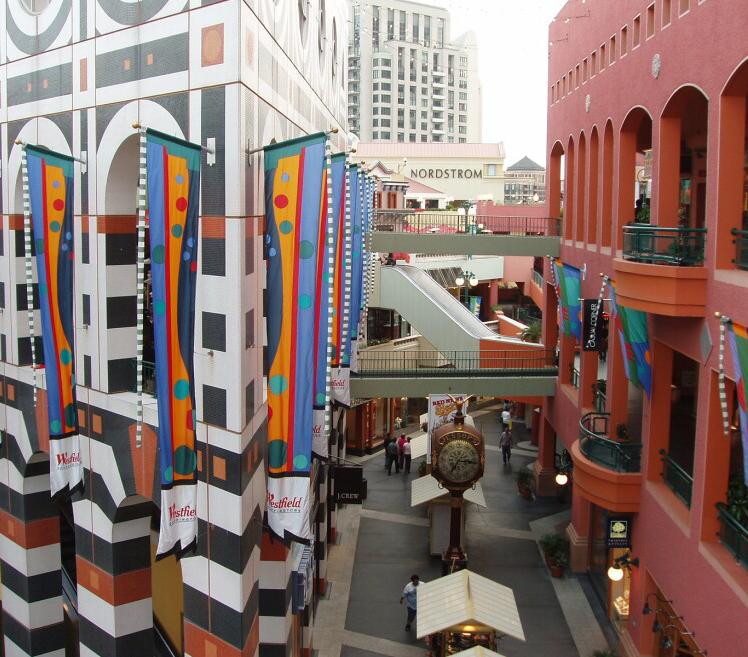

URBANFronts

Heli Shah 38

Licensed and then? AIA YAF Knowledge Focus Group 42

Advocate for immigrant architects and visa challenges Li Ren 44 Riding the vortex Gabriela Baierle 55 Being seen Tracie Reed 56

Connection and chill AIA YAF Knowledge Focus Group 57 Future Forward Grant

Vol. 20, Issue 03 2022 3 Contents

Editorial team

Editor-in-Chief

Beresford Pratt, AIA, NOMA

Pratt is a design manager and architect with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. He co-leads multiple J.E.D.I based architecture pipeline initiatives with Baltimore, Maryland K-12 students. He is the AIA Young Architects Forum communications director.

Senior Editor

Bryan Buckley, AIA, NCARB

Buckley is the studio director & business development director at Signal Work in Providence, Rhode Isalnd. He focuses his efforts on both internal and external growth and is the managing architect behind most of the firm’s K-12 and urban rehabilitation projects. He serves as a director-at-large for his local AIA chapter and is Rhode Island’s young architect representative..

Senior Editor

Meghann Gregory, AIA, NCARB

Gregory is a senior project architect at K2M Design. She is the young architect representative for West Virginia and a member of the AIA West Virginia chapter. Her professional interests include adaptive reuse, urban planning, custom residential, and sustainable practices.

Senior Editor

Holly Harris, AIA, ASHE, LEED AP BD+C

Harris is a healthcare architect and planner at SmithGroup in Chicago, Illinois. She was selected for the Herman Miller Scholars Program for emerging professionals in Healthcare in 2019 and recognized as a Rising Star by HCD Magazine in 2021. She is the chair of the AIA Illinois Emerging Professionals Network and serves as the young architect regional director for Illinois.

Senior Editor

Shawna Mabie, AIA, NOMA, LEED AP BD+C, WELL AP

Mabie is a project manager and associate at Hanbury in Raleigh, North Carolina. She has taught at North Carolina State University and University of Arkansas Community Design Center. She currently serves as the young architect director on the AIA North Carolina Board and is the young architect representative for North Carolina.

Senior Editor

Matthew Pultorak, AIA, NCARB

Pultorak is a Senior Planner/ Estimator for Rutgers University’s Planning Development and Design Team and Owner of Time Squared Architect, LLC in New Jersey. He currently serves as the young architect regional director for the region of New Jersey, Emerging Professionals Communities At-Large Director of Mentorship, and AIA Jersey Shore’s president-elect.

Contributors:

Daniel Hart. FAIA

Jessica O’Donnell, AIA

Kaitlyn Badlato, AIA Abigail Brown, AIA

Laura Ewan

Brian Baril, AIA

Gabriella Bermea, AIA

Saakshi Terway, Assoc AIA Paige Russell, AIA

Dennis Dine. Assoc AIA

Kurt Green, Assoc AIA Heli Shah, Assoc AIA Gabriela Baierle, AIA

Kathryn Prigmore, FAIA Li Ren, AIA

Tracie Reed, AIA

Knowledge Focus Group

Kaylyn Kirby, AIA Darguin Fortuna, AIA Ryan Lewis, AIA Kiara Gilmore, AIA Trent Schmitz, AIA Jason Takeuchi, AIA Terry Zink, AIA

Connection 4

Editor’s note:

“Don’t raise your voice. Improve your argument.”

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) have entrenched themselves as a foundation for good design practice and the future. In today’s climate, many seek ways to build on these critical pillars in meaningful, impactful, and action-driven ways. Young architects today have rolled up their sleeves and are at the forefront as they fight for diverse representation within their practices, inclusion on their project teams, equity for their clientele, and much more. Each day they work to advocate for DEI with immense passion.

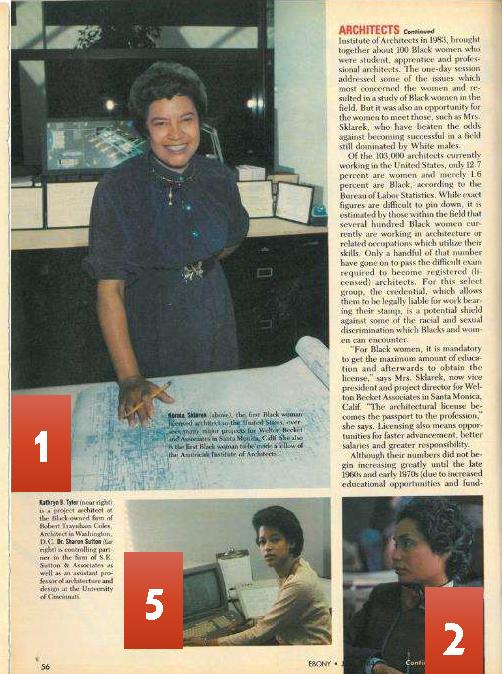

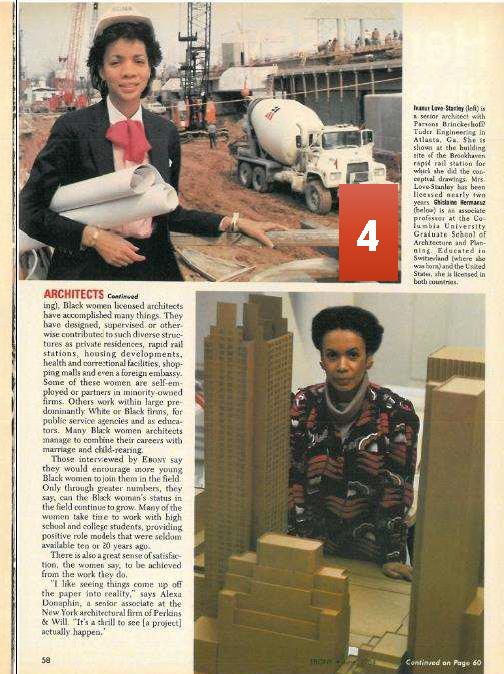

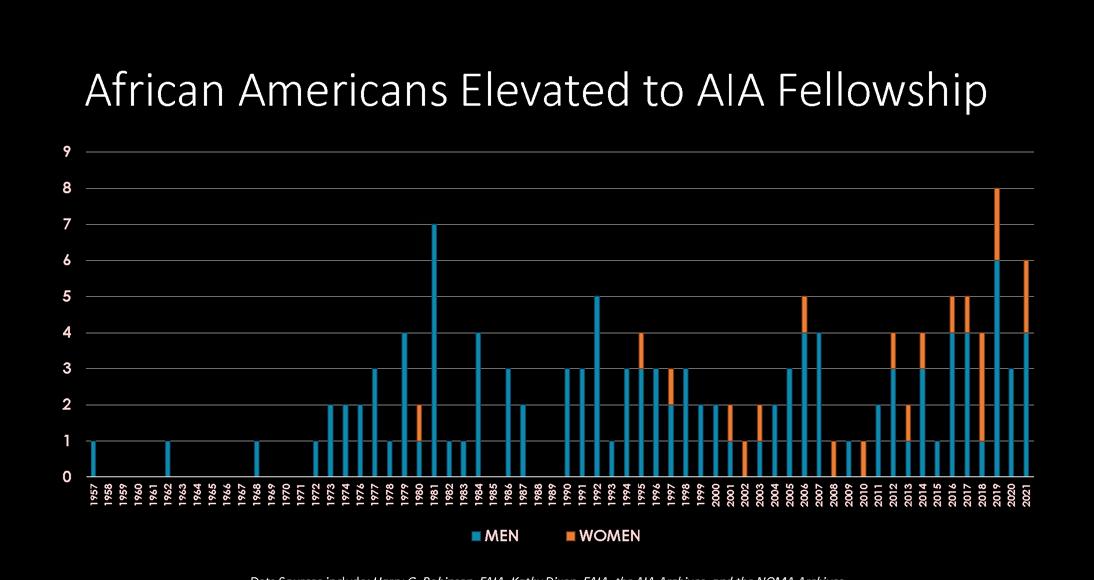

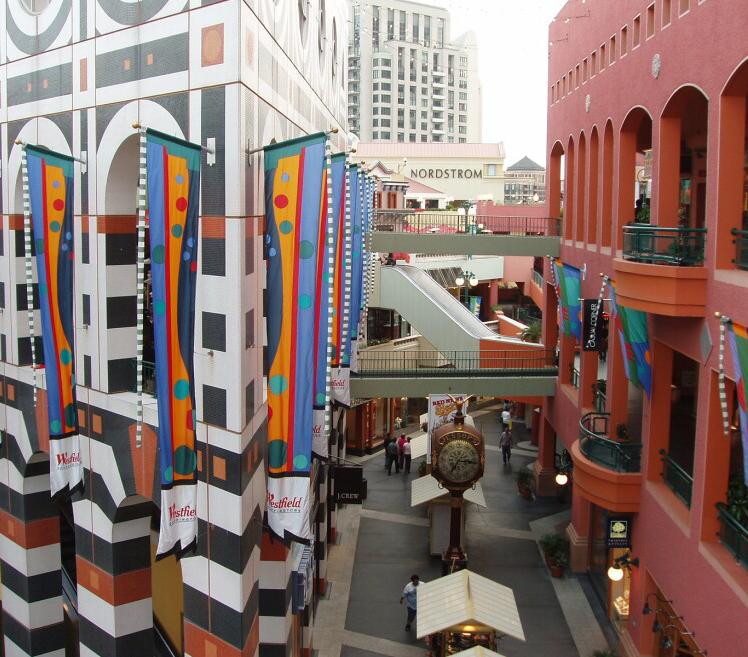

Young architects like Badlato understand the need for designing for a more equitable practice as she highlights the YAF webinar series. Brown and Ewan encourage professionals to lead with action in creating just practice through Just certification. We also hear from diverse voices about how they create a more inclusive industry through both their wins and challenges along the way, as Baril interviews young architects. Bermea brings to the forefront accessibility and the implicit bias that affect inclusive design. Both Teraway and Ren tackle how we can support immigrants as advocates, and elevate their voices and impact within the industry. We see that there is room for improvement in the pipeline process and growth for Women and BIPOC professionals, as Russell breaks down the numbers. Dine speaks to how we can generate empathy through design that affirms. Shah,

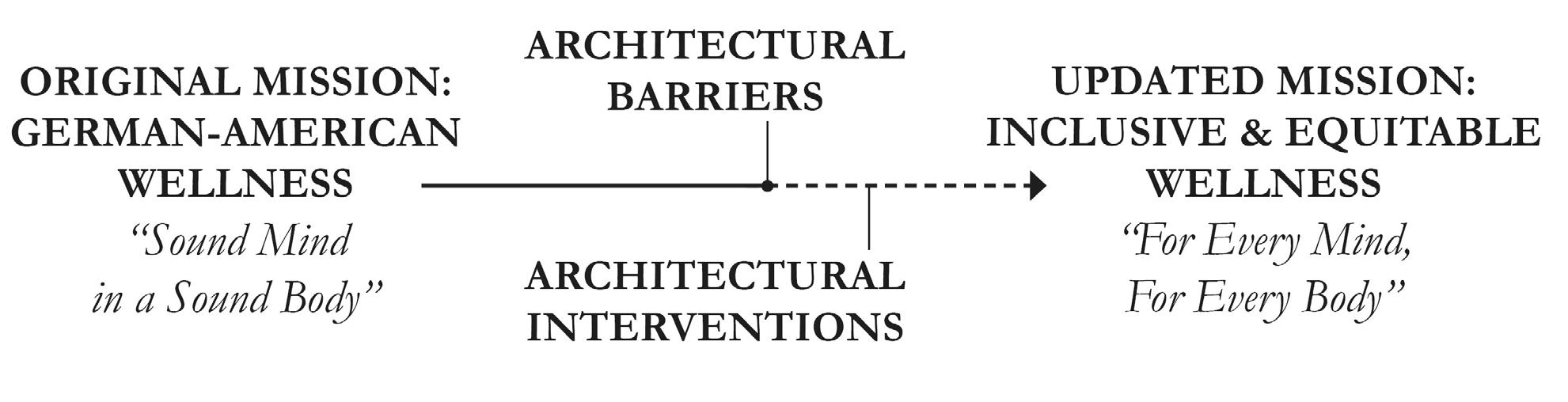

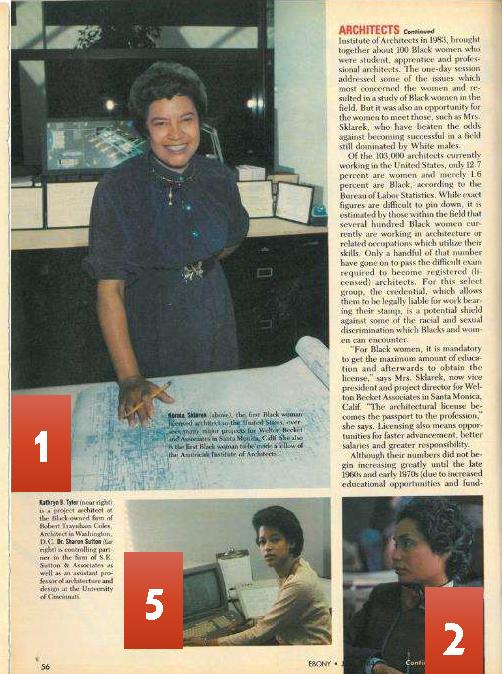

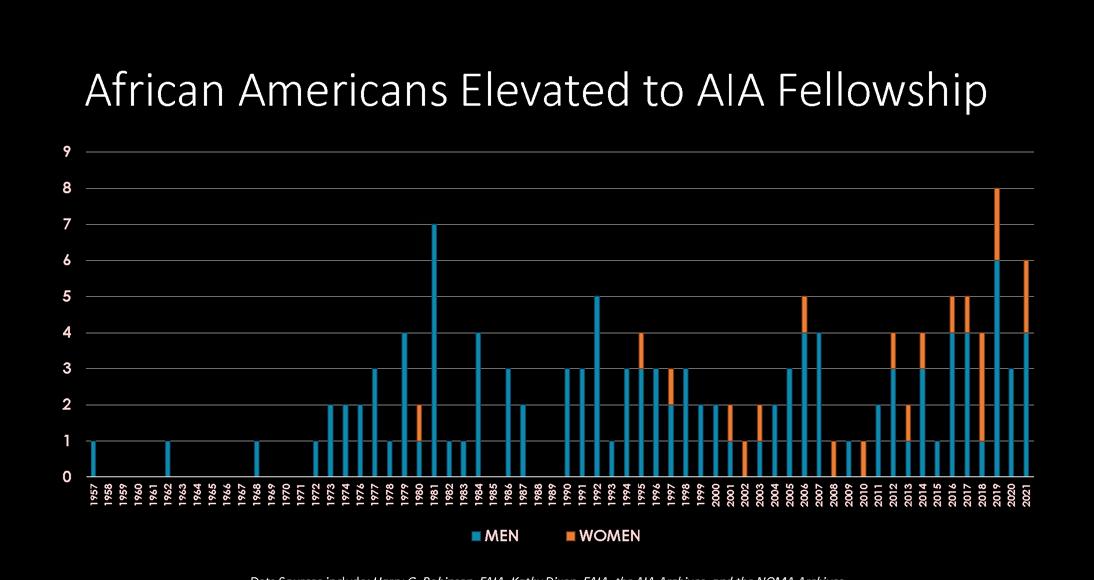

shows us how community-driven projects leave a lasting impact through the study of local history and collaborate with diverse contributors. Prigmore, FAIA shows us the powerful history of the first seven black women to receive AIA Fellowship.

Every day I’m personally impressed by all of the amazing impactful work young architects and professionals contribute across the nation. These are the stories that inspire me to become a better professional. Desmond Tutu once said, “Don’t raise your voice. Improve your argument.” Young architects have continued to build a strong case. I hope that each of you continues to take action, no matter how small or large, to build a more diverse, equitable, and inclusive society and industry. It has been a tremendous honor to serve as the communications director of AIA Young Architects Forum and an editor-in-chief of connection over these last two years.

Editorial committee call

Q4 2022/Q1 2023: Call for submissions on the topic Mission 2130 - YAF Summit

Connection’s editorial comittee welcomes the submission of articles, projects, photography, and other design content. Submitted content is subject to editorial review and selected for publication in e-magazine format based on relevance to the theme of a particular issue.

2023 Editorial Committee: Call for volunteers, contributing writers, interviewers and design critics. Connection’s editorial comittee is currently seeking architects interested in building their writing portfolio by working with our editorial team to pursue targeted article topics and interviews that will be shared amongst Connection’s largely circulated e-magazine format. Responsibilities include contributing one or more articles per publication cycles (3–4 per year).

If you are interested in building your resume and contributing to Connection please contact the editor in chief at: gbermea@vlkarchitects.com

Vol. 20, Issue 03 2022 5

President’s message: The future of architecture

This year, NOMA President Jason Pugh and I visited five of the seven HBCUs with National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAH)-accredited architecture programs. We will visit the other two schools later this year.

Chapter members and officers from both NOMAS and AIAS joined during the visits. Jason and I shared personal stories of our path to architecture. I enjoyed interacting with both the students and faculty to learn about their programs, successes, issues, and challenges.

AIA will continue to seek ways to support and enhance connections to these and other architectural programs to ensure equity and diversity in the pathways from education to practice and through the career continuum for our profession. Less than 3% of practicing architects in the United States are Black. In the 2020 study “Where Are My People? Black in Architecture’’ for the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA), Kendall A. Nicholson, Ed.D., Assoc. AIA, reports that one out of every three Black architecture students attends an HBCU, and explains, “This is substantial, because, on average, each of the remaining degree programs only graduates two Black architecture students each year.”

A recent step in increasing diversity to the profession was to add a new supplement to our Guides for Equitable Practice - Equity in Architectural Education. This report, created in partnership with ACSA, provides actions and prompts to inspire discussion within schools and institutions in achieving goals of equity, diversity, and inclusion. Since school culture and workplace culture interconnect, we’re urging all our members to read it to better understand the connection between academics and practice and how firm culture can support diversity.

We also have work to do when it comes to gender equity. The ratio of women to men graduating from architecture school is 49/51%. Yet women only make up 22% of licensed architects. According to a 2020 report in Architect magazine, only 0.4% of licensed architects in the United States are Black women. The Women’s Leadership Summit addresses this imbalance. The recent gathering was a great success and had speaker presentations on mental health, entrepreneurship, and belonging. This signature event will now take place annually.

We want to continue sharing success stories of women and minorities in architecture so students will continue to see themselves in our membership and in our profession.

Connection 6

We want you as emerging professionals to be engaged throughout your careers. I am heartened by the diversity in your forum. We want to help maintain that same diversity through all levels of the profession. We want to support you so that you can support the next generation of architects.

We also cannot promote diversity without sustainability –the two interrelated issues drive safety and preserve the health and protect the welfare of the public.

AIA alone cannot solve the lack of equity and diversity in the profession. We have and will continue to collaborate closely with other groups that are dedicated to advancing EDI, including NOMA, NOMAS, AIAS, other alliance organizations and even those outside the profession.

Morgan State University graduate student Taylor Hardey, the president of the school’s NOMAS chapter, echoed the need for this collaboration during our HBCU visits when she said, “The future of architecture depends on how much everyone is willing to help each other.”

Daniel S. Hart, FAIA, PE

Vol. 20, Issue 03 2022 7

Hart is the 2022 AIA president. He is the executive vice president of architecture and serves on the board of Parkhill. He was an adjunct instructor of architectural engineering at Texas Tech University and the founding president of the college’s Design Leadership Alliance.

YAF chair’s message:

Design pathways for impact

The Young Architects Forum was created in 1991 to provide a pathway for recently licensed architects to evolve their professional careers. The foundational mission and vision of the YAF galvanizes our work as a committee, but it is the unique perspective of each individual committee member that enables us to collectively engage and amplify voices that are not typically heard on a national platform. Past issues of Connection have challenged readers to keep showing up, to stay accountable, and to disrupt for enduring change. Building upon those, I want to share a few resources in my message as chair to help everyone design pathways for impact to achieve a more equitable future.

As Marian Wright Edelman said, “You cannot become what you cannot see.” Many of us were fortunate enough to be introduced to architecture by a family friend or teacher, but there are many children who grow up not knowing what architecture is or what architects do. The AIA has a robust collection of K-12 Pathway Initiatives that individuals or components can take into their local schools. These programs are wonderful examples of how we can introduce our profession to children through engaging activities. Opening up this type of pathway to information early on creates a variety of opportunities for new voices to enter our profession; the future impact this could have is limitless.

Throughout 2021 and 2022 our YAF Advocacy workgroup developed and hosted a mini-series of webinars to expand access to information that continues to position architects as agents of change in the profession and in our local communities. These sessions create space to grow, share, inspire, and partner with those who have made significant impacts with their equity work. So You Want to be a Citizen Architect?, So You Want to Design for All? Designing for Belonging, and So You Want to Build an Equitable Future? can be found on AIAU and short recaps are in past issues of Connection. The YAF for So You Want to Design for All? Designing for Mental Health was held on 12/6/22.

If you’re looking to create pathways for change within your career trajectory or at your firm, check out the Guides for Equitable Practice. These guides give readers the baseline tools necessary to have meaningful conversations across nine dynamic topics with two supplementary editions, all related to EDI. If you’re not sure how to start these sometimes difficult and uncomfortable conversations, or if you’re just looking to better understand the perspectives of others, a read through these guides will illuminate several pathways forward. Acknowledging biases that exist within the architectural profession can be challenging for anyone who has not personally experienced one. The Elephant in the (Well-

Connection 8

Designed) Room is a short but powerful snapshot of the current biases that do exist. Reading through this information illuminated several biases that I was not aware of but will now be more cognizant of as I go through life. I was encouraged to find that this document also proposes potential solutions to interrupt those biases and break the cycle, so we have no excuse for maintaining the status quo.

AIA Minnesota’s Culture Change Initiative is an aspirational example of impact. If we as a profession continue to do what we have always done and foster the same professional culture, we will never achieve anything different from the status quo. This initiative is available to any form or organization within the architectural profession and provides a training presentation on the ongoing effort to reexamine the culture we are collectively creating as a pathway toward achieving our desired culture.

The recently completed NCARB by the Numbers 2022 shows that progress within our profession is being made. Our challenge is to continue to build upon the meaningful conversations that have started and provide tangible actions that drive impact. The resources noted above are a small sample of pathways that each of us can carve out to open the profession up to new voices.

Resources to check out:

• Guides for Equitable Practice

• https://www.aia.org/resources/6246433-guidesfor-equitable-practice

• Culture Change Initiative – AIA MN

• https://www.aia-mn.org/get-involved/ equity-profession/culture-changeinitiative/#:~:text=The%20Culture%20Change%20 Initiative%20is,in%20achieving%20that%20 desired%20culture.

• AIA K-12 Pathway Initiatives

• https://www.aia.org/resources/154816-k-12initiatives

• The Elephant in the (Well-Designed) Room: An Investigation into Bias in the Architecture Profession

• https://content.aia.org/sites/default/files/2021-12/ AIA_Bias_Interrupters_FINAL.pdf

• https://www.aia.org/pages/6435906-aninvestigation-into-bias-in-the-architec

• NCARB by the Numbers 2022

• https://www.ncarb.org/sites/default/files/ NBTN2022.pdf

• YAF Advocacy webinar mini-series

• So You Want to Be a Citizen Architect? Get Inspired to Take Action! AIAU

• So You Want to Design for All? Designing for Belonging AIAU

• So You Want to Build an Equitable Future? Practice Innovation through Universal + Inclusive Design

• So You Want to Design for All? Designing for Mental Health

• So You Want to be a Citizen Architect? YAF Connection

Vol. 20, Issue 03 2022 9

Jessica M. O’Donnell, AIA O’Donnell is a project architect at Thiven Design in Collingswood, N.J., where she specializes in multifamily housing. She is a 2022 AIA Young Architect Award winner and the 2022 chair of the YAF.

So you want to… Build an equitable future?

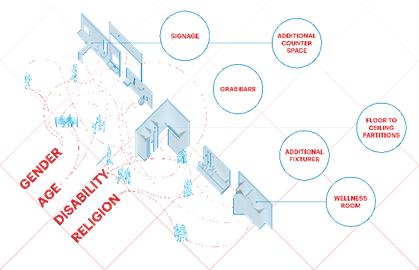

How can the architecture profession go beyond the minimum requirements of codes and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) to create more equitable and inclusive spaces for all? Today, designers are looking at how the built environment can affect a person physically, mentally, and socially. On August 9th, 2022, the Young Architects Forum (YAF) Advocacy Focus Group hosted their third webinar of the “So You Want To…” series bringing together an audience of young architects to learn how to be advocates for incorporating principles of universal design in their projects to achieve not only more successful designs but more equitable communities where all may thrive.

The event was moderated by Olivia Asuncion, project architect at Quattrocchi Kwok Architects and American Institute of Architects (AIA) YAF California Representative, and she was joined by panelists Seb Choe, Associate Director at MIXdesign, Jade Ragoschke, vice president of World Deaf Architecture, and Ileana Rodriguez, principal of Design Access, LLC (Figure 1). The YAF Advocacy Focus Group includes Monica Blasko, Anastasia Markiw, Laura Morton, Melissa Gaddis, Trevor Boyle, Christopher Fagan, and Kaitlyn Badlato.

Informed by lived experience

An architect’s work and values are informed by their identity and lived experience. Each of the panelists shared anecdotes from their upbringing, describing how those experiences and challenges shaped their focus and impacted their decision to become design professionals. From a young age, Olivia was aware of her surroundings and space because of her physical disabilities. Growing up in the Philippines, she found that many environments, including schools, were not accessible. She moved to the United States at age 11, less than a decade after the passage of the ADA, and “accessibility was just there. It wasn’t perfect then and it still isn’t, but it was already built into my surroundings… I very quickly and very clearly learned that the design of the built environment has the power to foster independence, promote inclusivity, and create community.”

Olivia’s experience of the built environment in the Philippines and the United States led her to pursue a career in design, advocacy, and research. “One of the keys to ensuring justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion [JEDI] is providing access to the built environment… How can we expect diversity otherwise?”

While at the University of Oregon, she was able to perform design research into accessible evacuation, improving fire safety, and building evacuation for people with disabilities. Her professional work focuses on universal design across multiple sectors, including higher education and fire houses. Currently, Olivia is serving as a Fulbright Scholar, assessing the accessibility of elementary schools in the Philippines and the impact it has on enrollment of disabled children. Her practice is supported not just by expertise and research but by her own valuable insights from lived experience.

Inclusion means advocacy for all Seb’s work is rooted in the idea that “any project that aims to utilize inclusive design and [focus on] community needs requires us to acknowledge the many identities and roles we play in our communities. This often exceeds the narrow roles of our professional lives and influences our approach to design.” As an educator, performance artist, city council agitator, digitally embodied raver, and community facilitator, they wear many different hats in addition to their professional role as associate director at JSA/MIXdesign. The think tank and consultancy approaches inclusive design “based on this conviction that human experience and embodied identity [are] constituted by a variety of overlapping factors.” MIXdesign advocates for the active participation of stakeholders and endusers. This ensures that those who are most impacted have a seat at the table along with an in-house team of experts in design, policy, and public health who specialize in working with and for deaf, autistic, and physically disabled communities. The firm’s work with the Queens Museum prioritized the spatial needs of diverse visitors who fell outside the cultural mainstream. MIXdesign assembled an interdisciplinary team and organized extensive community engagement. The

Connection 10

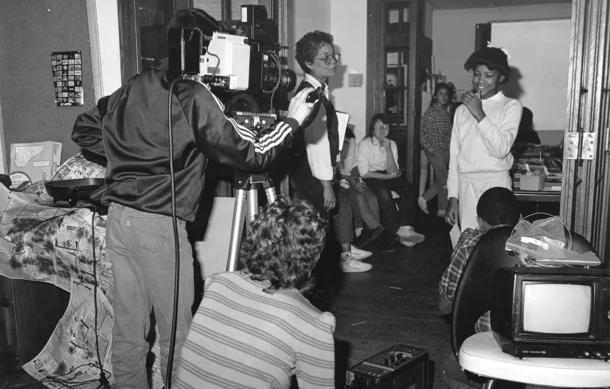

Above: So You Want To…Build An Equitable Future Webinar Panelists courtesy of Monica Blasko

museum design team formed a cohort of 25 Queens residents that reflected the audience the museum wanted to attract, including seniors, wheelchair users, parents with young children, native Spanish speakers, people with low vision, nonbinary people, and more. The paid cohort worked with the design team to create inclusive design recommendations that provided value to the project and broadened the museum’s local audience.

Performance beyond a baseline

After graduating architecture school, Jade Ragoschke was contracted by the Department of Education in New York City (NYC) to bring public schools across the city to 100% accessibility under the ADA. It was during this time that she discovered the ADA’s limitations. Her current role as a thirdparty accessibility code reviewer for the Chicago Department of Buildings has exposed to her how some architects interpret the ADA requirements in ways that miss the mark or simply default to general notes or standard details.

Outside of the office, Jade is dedicated to improving the baseline of accessible and universal design. Jade is profoundly deaf in her right ear, and while she wasn’t integrated into the deaf community or in a position to access deaf culture until college, she soon began learning about the impacts of the

built environment on the community. She became involved with World Deaf Architecture, which provides networking and education for deaf and hard-of-hearing architects and designers. Through this organization she has served as an advisor for the AIA Guidelines for Equitable Practice and is working with a committee developing Deaf Space guidelines and best practice—designed for the deaf community, by the deaf community. Deaf Space is entirely separate from the ADA and provides a creative approach to improving the quality of space for people with and without hearing loss.

As a Paralympic athlete, Ileana Rodriguez believes in the impossible. “You see athletes that can do all things regardless of their disability because this is not what defines them, but what they decide to do.” Ileana uses her agency as an architect to change the perspective that people have on people with disabilities. “If we allow them to perform, if we allow them to have a better life, space can influence the potential of a person… [To do this] we need to move way beyond the code.” Accessibility is often integrated later on in the design process, rather than at the beginning. Ileana wanted to change this, so she started Design Access, LLC to be able to dedicate time and resources to getting it right. This has allowed her to work with the International Paralympic Committee to find opportunities in the venues and facilities of the Paralympic Games where the

Vol. 20, Issue 03 2022 11

Above: Matrix created for Stalled! considering the diversity of end-users and activities of a restroom that lead to design strategies to improve the experience; image courtesy of Seb Choe

‘after’

accessibility could be improved and become more inclusive. Her work spans the world, in countries that don’t even have an accessibility code as extensive as the ADA. In fact, some of these countries are where the best opportunities for improving accessibility lie, since there are so few regulations.

Inclusion in action

Our panelists have used their expertise and passion to create high-performing spaces of inclusive and universal design.

Stalled!, presented by Seb Choe, is MIXdesign’s inclusive design process, which aims to be intersectional. Stalled!Presented by Seb Choe; MIXdesign’s design process aims to be intersectional. The diagram (Figure 2) considers the many different overlapping identities we inhabit as well as the activities that we perform. Restrooms are spaces in which there are many different activities taking place; thus, they need to serve a diverse group of individuals, families, and caregivers.

“There ultimately isn’t a perfect, universal, one-size-fits-all solution,” says Seb. Instead, the prototype, Stalled!, analyzes the many demands of the space and generates spatial strategies that foster sharing space while also rethinking traditional design.

Seb reinforces that this design work is more than just design; it is about “working between design, research, and advocacy.” Stalled! is more than just a prototype; the work includes design recommendations, lectures, workshops, as well as legal initiatives, including amending the 2021 International Plumbing Code to allow for all-gender restrooms.

This tennis club, presented by Ileana Rodriguez, was one of the biggest challenges Ileana faced while consulting for the Paralympic Games in Lima. The owner was hesitant to make any changes, so the team studied and identified both permanent and temporary changes that would provide the biggest impacts for accessibility. After the Games, the owner

was so impressed with the improvements that he decided to keep all of them (Figure 3). The club is now used by a lot of the local elderly community; indeed, anyone can take advantage of the club. Ileana says, “I like to do this work because you have an impact beyond the infrastructure. You have the ability to change the lives of people. You have the ability to change the perspective of people with disabilities, and also improve the experience of people.”

The takeaways

Inclusive and equitable design is not created from a singular code or set of guidelines. True equity is found by including multiple, diverse perspectives throughout the process. This includes not only subject-matter experts and professionals but also the users that you are designing for. As Jade says, “There is a need to advocate for dedicated spaces for many different communities, but it’s not just about making those spaces accessible. It’s also about communicating to users through architectural design that they have permission to engage and belong in that space… As architects, we need to become agents of change and be more civically engaged with the communities] that we design for.” By creating inclusive environments, we create agency for all to utilize the spaces we design, building community and bringing more customers to our clients. “We need to share our own unique experiences that influence our perspectives and approaches to solving problems, while also being willing to take a step back and listen and support the voices of others.”

Kaitlyn Badlato, AIA, EDAC, WELL AP, LSSYB

Connection 12

Above: Accessibility improvements at the site of the Paralympic Games. The left image shows the original entryway with stairs and a steep, small ramp. The right,

image shows a wide ramp with a gentle slope and a person entering in a wheelchair; image courtesy of Ileana Rodriguez

Badlato is a medical planner at HKS in Washington, D.C. She serves as the AIA MidAtlantic young architect regional director.

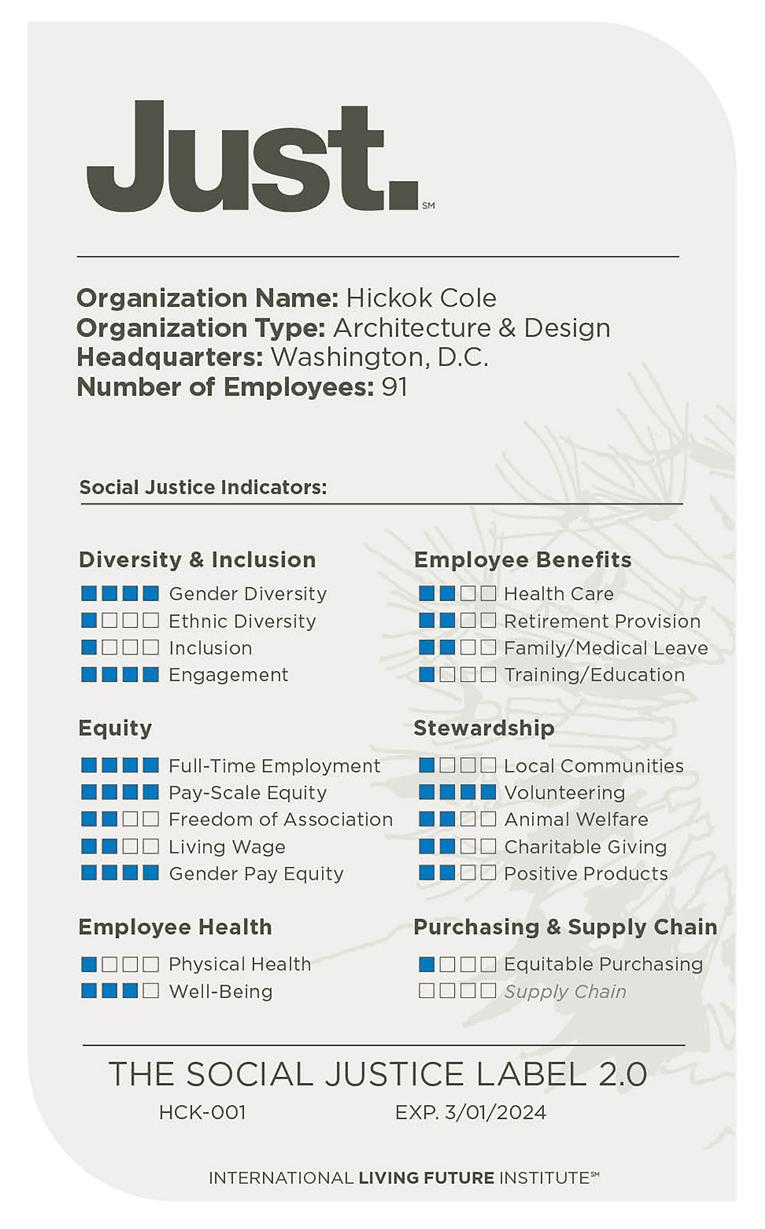

Walking the walk: Using the Just label to benchmark EDI initiatives

The year 2020 challenged all of us to reassess our values and how they show up in how we live our daily lives. Architecture was not immune, with firms of all shapes and sizes taking a critical look at the delta between who they are and who they say they are to find meaningful ways to close the gap. Everyone from emerging professionals to firm leaders are in a position to spark change and ensure that the actions behind our words have impact. But where do we start? And what’s the best way to set significant goals and measure progress over time?

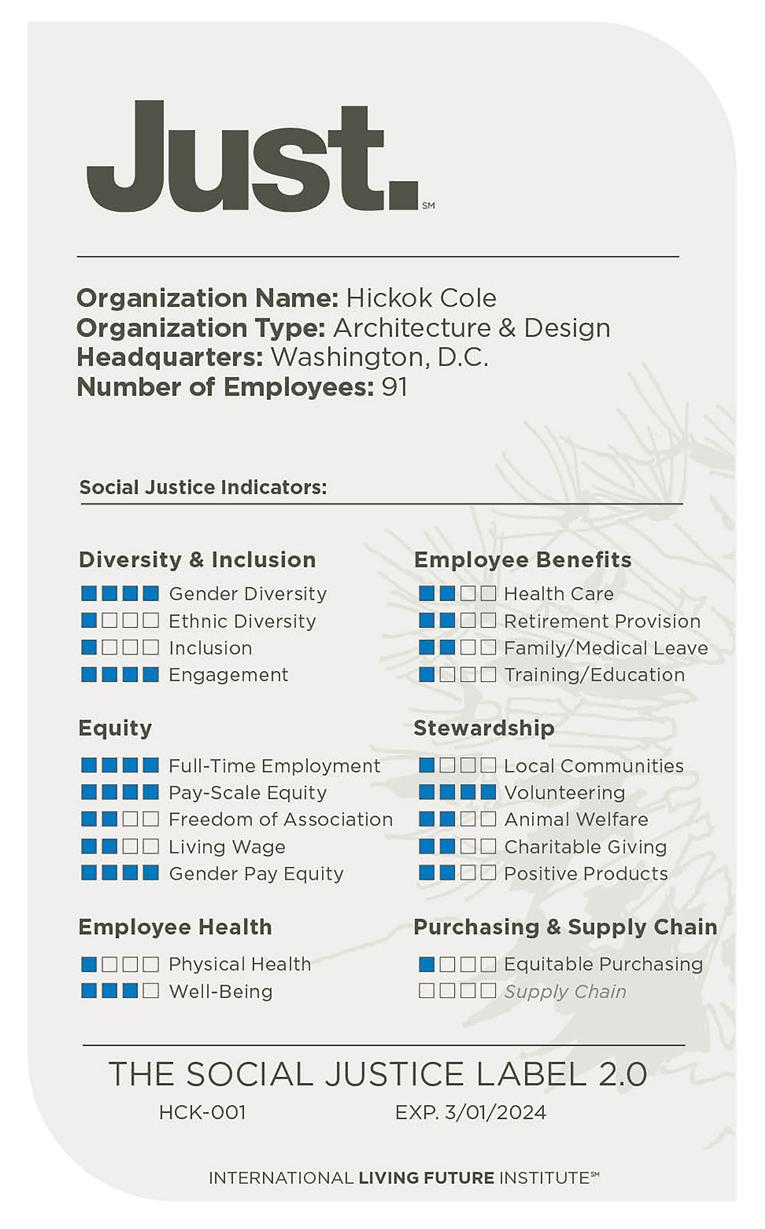

One tool that architecture firms can turn to is the Just label. Developed by the International Living Future Institute the same organization behind the Living Building Challenge and Declare product labels Just is a transparency label for socially just and equitable organizations.

The Just label requires reporting on 22 indicators organized into six themes: diversity and inclusion, equity, employee health, employee benefits, stewardship, and purchasing and supply chain. Each indicator outlines accountability metrics organizations must meet to earn recognition at four levels of performance. To attain level one, organizations must have a written policy statement addressing the issue in that indicator. To attain levels two through four, organizations must demonstrate compliance with specific metrics of increasing difficulty. Unlike LEED or WELL Building Standard certifications, there are no points with Just. Successful organizations ultimately receive a transparency label that illustrates the level they’ve obtained for each indicator.

Well known architecture firms like Ayers Saint Gross, BNIM, CallisonRTKL, Lake Flato, and ZGF have all pursued Just labels to chart a course toward transparency and continual improvement. We began our Just journey at Hickok Cole in 2019 with a grassroots effort spearheaded by our Staff Operations Committee. The Staff Ops team is tasked with strengthening the firm’s employee experience from recruiting and onboarding to mentoring, licensure, and professional development. Completing our application took two full years, with a lot of lessons learned along the way.

We’ve broken the process down into eight steps to help firms interested in earning their own label.

Step 1: Determine if Just is the right label for your firm Spend some time thinking about why a transparency label is appropriate for your firm. Hickok Cole chose to pursue Just because it provided a clear roadmap that touched on multiple aspects of firm operations from demographics to employee benefits to how we identify partners and where we buy our supplies. Our mission is about doing work that matters

Above: Hickok Cole’s Just label

through our project work and in our community. Just provided a formalized framework to measure our progress and ensure we’re walking the walk of the core values and culture we’ve established.

Keep in mind that Just is not the only third party transparency program available. Other programs include B Corporation certification, the UN Global Compact, and AIA’s state and local Emerging Professional Friendly Firm programs. All of these programs have different market visibility, application requirements, and associated costs, so it is important to choose the one that best fits your firm’s needs.

Step 2: Get buy-in from leadership and stakeholders

Sometimes the decision to pursue a Just label is initiated by firm leadership, but a grassroots effort is just as effective. If you think Just would benefit your firm, don’t be afraid to pitch it to your leadership. Talk to your colleagues to get support. Good partners might come from your marketing department, as they are responsible for demonstrating your firm’s EDI commitments in proposals, or from your hiring and recruitment team. Gather data about the cost to your firm (it is based on the number of employees), because that is often the first question a decision maker will ask. Additionally, you’ll want

Vol. 20, Issue 03 2022 13

to make sure leadership understands the policy statements and data you submit will be publicly accessible on the IFLI’s Just Database. If that is a dealbreaker, then a different transparency program may be a better fit.

Step 3: Assess where your firm stands today, then identify low hanging fruit

A good initial step is to read through the Just Manual and determine where you think your firm falls on each indicator today. Then, identify any indicators that could easily be leveled up before you submit your application.

Hickok Cole quickly realized that expanding insurance coverage in our benefits package was a low cost action that could be implemented at the next open enrollment period. Another example: employees were not eligible to enroll in the 401k program until they reached six months of employment. We worked with our plan provider to change this policy so new employees are immediately eligible and automatically enrolled unless they opt out.

Step 4: Determine champions for each indicator

Just indicators touch many facets of firm operations, so preparing an application requires input from many players.

Hickok Cole found that the highly collaborative process united members from across the firm in a way that few initiatives had before. Our process included contributions from human resources, accounting, marketing and business development, committee chairs, and firm leadership while regularly informing and engaging staff at all levels.

Keeping that many contributors engaged over time can be a challenge. Since this work is often extra-curricular, it can easily move to the back burner. Make a plan and schedule regular checkins to keep things moving, but expect that it will take longer than you think. A good strategy is to create a Just Task Force and assign an appropriate champion to lead each indicator.

Step 5: Look for creative ways to level up

During the process, it will become obvious that reaching the next level of some indicators is difficult or prohibitive. For example, the gender and ethnic diversity of your firm is not something you can change overnight, as that requires intentional and sustained action over the long term. Additionally, some indicators will require financial investments that your firm might not be able to commit to at this time or ever

Connection 14

Above: Collaboration space at Hickok Cole. Photo credit: Garrett Rowland

Don’t be afraid to look for creative solutions. Hickok Cole had historically budgeted one billable hour per week for each employee to participate in a Friday happy hour. The Just process, and a new hybrid work policy, challenged us to reevaluate the tradition. The team identified Just indicators where hours could be reallocated to diversify our benefits package and enrich our culture. The 52 billable hours are now divided three ways: 24 hours for volunteering in our community, 16 hours for volunteering internally on committee work, and 12 hours reserved for less frequent, but more meaningful social events. Maximum impact for our employees—and a Level 4 score for Volunteering—without impacting our bottom line at all.

Step 6: Gather, write, analyze, and submit your application

Time to roll up your sleeves and do the work! If your firm is anything like Hickok Cole, you’ll need to gather a lot of data, write a lot of new policy statements, develop staff surveys on things like demographics and engagement, and determine which level your firm reaches for each indicator.

After you submit your application, you will receive comments from the International Living Future Institute. You may be updated or downgraded in some indicators depending on IFLI’s confirmation and interpretation of your data. Hint: establish a line of communication with ILFI early to ask questions and minimize changes on the back end. Once you respond to and finalize all comments, your firm will be issued its label and your data will be added to the Just Database

Step

7: Share your label

It’s time to celebrate! Make time to share your newly acquired Just label with your firm. Let everyone know what it means, answer questions, and launch any new policies that were developed during the application process. Work with your marketing department to write a press release to share on your firm’s website and social media, and start identifying how it can be used in marketing and recruitment collateral. Ask team members to help spread the word. The Hickok Cole Just

announcement on LinkedIn received unprecedented levels of employee engagement

Step 8: Continue benchmarking progress and make a plan for what’s next

The work doesn’t stop here. Getting your initial label is a huge accomplishment, but the real benefit of Just is using it as a tool to benchmark progress over time. Spend some time reflecting on indicators your firm can strengthen and make a plan to work toward those goals. Just labels need to be renewed every two years which gives you plenty of time to make progress before preparing your next application.

Choosing to participate in any transparency program is an opportunity to get aspirational about your firm’s future while creating real and tangible organizational change. Hickok Cole team members felt the impact immediately and we’re just getting started. The Just label serves as a north star and gut check for our firm committees and leadership to ensure we’re all working towards a shared vision and a more equitable future. Will you join us?

Abigail R. Brown, AIA

Brown is an architect at Gensler in Washington, DC, where she works as a project architect on mixed-use projects. She previously led Hickok Cole’s effort to apply for a Just label.

Vol. 20, Issue 03 2022 15

Above: Open office space at Hickok Cole. Photo credit: Garrett Rowland

and shares to their networks

Laura Ewan, CPSM Ewan is the director of marketing + communications at Hickok Cole in Washington, DC. She is an active member of the Society for Marketing Professional Services.

Above: Collaboration space at Hickok Cole. Photo credit: Garrett Rowland

If not us, then who?

In Connecticut, two members of NOMAct have begun grassroots initiatives that achieve the organization’s stated goal of promoting, championing, and highlighting the work of architectural professionals throughout Connecticut, as well as promoting equity, diversity, inclusion (EDI), and belonging. I spoke with both members to discuss their efforts.

Dominique Moore is an architect and interior design professional with a demonstrated history of domestic and international design collaborations for residential, educational, commercial, and hospitality projects. She serves as a co-founder of My Architecture Workshops Inc., as treasurer, as a member of the board for NOMAct, and as chair for the NOMAct Budget & Finance Committee. Dominique is also a regional associate director for AIA New England, co-chair for the AIA CT EDI Committee, an advisory board member for the University of Hartford (UHart), and a co-founder of DCMS (Design Coalition of Minority Students) at Philadelphia University. Dominique graduated from Philadelphia University with a Bachelor of Architecture degree.

Brian Baril (BB): Can you tell me a little about yourself?

Dominique Moore (DM): I’ve wanted to be an architect since I was six years old. I’m a Philadelphia University alumna; I received my Bachelor of Architecture degree and began my professional career working on high-end residential projects in New York.

From there, I developed a passion for hospitality, and began working on luxury international hotels around the world. My love for architecture comes intertwined with my passion for people and how the two are interconnected.

I spent three months volunteering in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake and focused my career on balancing the art of architecture with compassion for those who interact with it.

BB: How did Architecture Workshops come to be?

DM: It all started with a very simple question: “So what are you going to do about it?” These were the words of my co-founder Alex Hidalgo, who on Juneteenth 2020 challenged me to be proactive in creating change in our industry for other black and brown children who are otherwise not exposed to our field and profession in general.

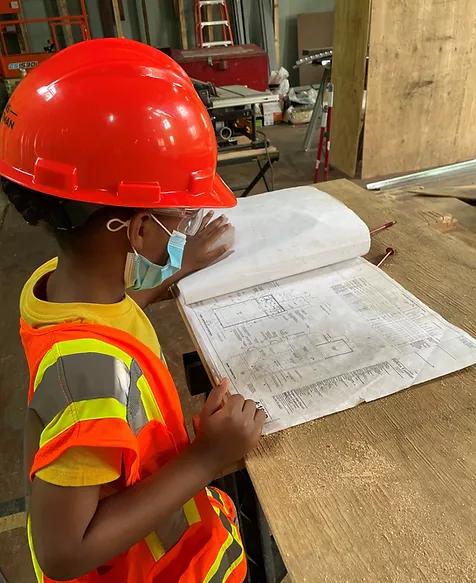

Since then, with co-founders Alex and Rebecca Spangler, I’ve hosted a series of after-school and summer programs that consist of construction site tours to expose students to architecture, design, and construction. During the pandemic, we were also able to offer virtual classes to teach SketchUp, and discuss principles of architecture, interior design, and graphic design, in addition to our site tours.

In summer 2021, we also successfully partnered with J.M. Wright Technical School and launched a summer program teaching students how to use Revit.

BB: What has been the most successful aspect of the program thus far?

DM: There have been so many extraordinary moments, but our greatest success to date has been the creation of our 2022 six-week architecture summer camp, launched summer 2022,

Connection 16

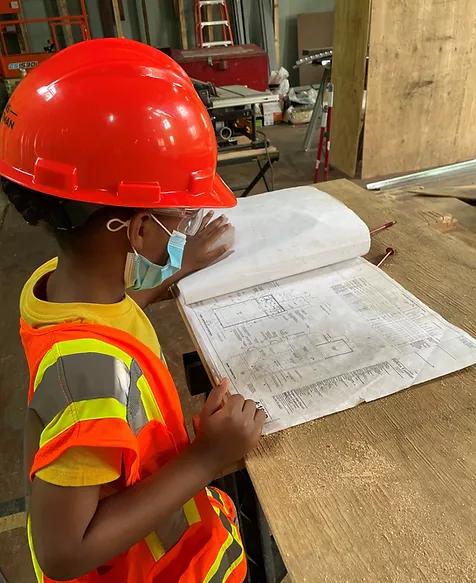

Above: Architecture Workshops construction site tours.

which provided exposure to architecture, design, engineering, and much more to K-8th grade students. The camp ran a full eight-hour-a-day program, five days a week, and was led by our amazing camp director Angela Hunt. Angela was instrumental in bringing this camp to fruition.

BB: Was there anything that surprised you?

DM: Many things surprised me, including our payroll, operational logistics, the developing curriculum, and the socialemotional aspects of our students. We soon realized that what we had created was more than an architecture summer camp; it became a place for students to engage and feel safe, to learn how to team build and be leaders.

The camp became an outlet for parents, mentors, and staff. It was entirely staffed by undergraduate, graduate, or soonto-be college students with either an interest or a major in architecture or design. This was the surprise of a lifetime!

BB: Where are you looking to improve the program?

DM: The greatest need we are seeing with our students (especially our high-school students) is mentorship. We would like to improve

Above: Studio teams collaborating on their summer camp final project. this portion of our programming to help fill this void.

BB: What is your vision for the future of the program?

DM: We envision expanding our summer camp program to reach more students in areas outside of Stamford, Connecticut, our flagship location.

We also plan to increase our design-build program, which runs during the school year, for our high-school and trade-school students, who receive hands-on design and construction experience.

BB: How do you think architecture workshops can promote EDI and belonging initiatives within the architecture profession?

DM: Architecture Workshops was founded on the mission to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion within the profession. Within architecture, we see disparaging gaps between professionals from disadvantaged backgrounds and what others are able to attain. These disadvantages are connected to children from low-income families, children with disabilities, English learners, and migrant students, students experiencing homelessness, and children and youths in foster care. These subgroups of students most often do not get exposed to the field as a possible profession; nor do they have the economic means to maintain a pursuit of the profession. Our program provides opportunities for these youths to explore architecture, offering guidance and support along the way.

Vol. 20, Issue 03 2022 17

Above: Architecture Workshops Summer Camp Future Builders

BB:

DM: Yes: don’t think, just do! There is such a great need to create avenues for youths to explore and pursue this industry. As professionals, we have a responsibility to help foster that pipeline. We don’t have all the answers, but one thing that has helped us is to just “keep it moving.” When we come up to an obstacle, we don’t let that stop our progress; we keep it moving.

When one door closes, another opens. In other words, don’t bang your head against the closed door; just pivot and walk through the open one.

BB: How does your program tie in to Cassie’s efforts with the “I Am” series?

DM: Cassie is leading such an amazing production with the “I Am” series! Both programs share a common goal, which is to present architecture to a diverse group of youths by sharing our experiences and inspiring others to reach their goals. We’re both working to make architecture more tangible.

BB:

DM: Our Design/Build program is a partnership with J.M. Wright Technical School, in Stamford, Connecticut, to design and build an e-house on the school campus. Originally, several of the students who had enrolled in the Design/Build program attended a construction site tour of the Barn Facility at Strawberry Hill School in 2020. From there, we built more specific programming for the technical school, including Revit training and student mentorships. Through those channels, we were invited to relaunch a Design/Build program that had been defunct for several years.

We loved the idea of bringing the program back and began building a team of design and construction professionals. We created workshops with the students to learn Passive House, sustainable design, Revit, and actual construction, in collaboration with the teachers. We are very excited and are looking forward to seeing this completed in the summer 2023.

Connection 18

Do you have any recommendations for others that are considering starting similar programs?

Tell me about the Design/Build program that you’re initiating. How did your initial efforts with Architecture Workshops lead into this effort?

BB: Who are some of your aligned partners (sponsors and partner firms) in this effort?

DM: We have been very fortunate in getting the support of a variety of firms and organizations as we continue to build the program.

To name a few: Newman Architects, Crosskey Architects, Pickard Chilton, the Connecticut Architecture Foundation, NOMAct, CPG Architects, Huestis Tucker Architects, Marc G. Andre Architects, 1220 Art Salon, Puppy Loving Care, Sound Federal, Stamford Moms, the City of Stamford, and the Connecticut Department of Education.

BB:

DM: Our students!

We’re always asking ourselves how we can continue to engage students, and make our programs more applicable, purposeful, and obtainable. We consider our programming to be organic in nature as it is created based on students’ needs; we simply continue to build as they grow.

More information can be found at http://www. myarchitectureworkshops.com

Vol. 20, Issue 03 2022 19

Above: Open air classroom at Chester (CT) Elementary School

What’s the biggest catalyst for the future success of the program?

Cassandra Archer received a Bachelor of Science in Architecture from Wentworth Institute of Technology, Boston in 2012. After graduating, she moved to California to begin her career as a project designer for a San Jose firm specializing in education and commercial interior fit-outs. In 2016 she returned to the East Coast, working at New Haven’s Kenneth Boroson Architects before joining Centerbrook in 2018, where she’s been actively working on a variety of projects from educational to housing. In 2019, Cassandra completed her architectural licensing.

Cassandra’s passion for mentoring the next generation of architects is evident in her active involvement with NOMAct; as their Sponsorship Committee chair and K-12 Outreach co-chair, she is responsible for engaging with the architectural community to create internship, scholarship, and experiential learning opportunities for students. In addition to NOMAct, Cassandra is involved with several EDI initiatives dedicated to making the field of architecture accessible to all. Cassandra extends her volunteerism to her local community as an active member of the Lyme Academy of Fine Arts’ Board of Trustees as well as the Connecticut Architecture Foundation.

Brian Baril (BB): Can you tell me a little about yourself?

Cassandra Archer(CA): Throughout my career, I’ve discovered a passion for community design and collaboration, specifically within K-12 education. It’s quite moving to be part of the process and watch teachers, principals, community leaders, and parents come together to create a better environment for the next generation. My favorite project I’ve worked on is a small outdoor classroom that I volunteered to design and help manage. It started during the height of COVID, when two retired educators in Chester, Connecticut saw the challenges that indoor learning presents to both students and teachers. They spearheaded a campaign to build a permanent sustainable outdoor learning space that is now used for both classes and community events. It was great to see the community come together to make this possible.

BB: How did the “I Am” series come to be?

CA: The series was born from a discussion with Sara Bruno, Sustainable Architecture Department Head at Platt Technical High School in Milford, Connecticut, who highlighted the need for students to be more aware of opportunities available in the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry. We wanted to create a space where all students can see that they, too, can one day be an architect, an electrical engineer, a structural engineer, a construction manager, a virtual design and construction (VDC) engineer, and so on! And so the “I Am” series was born.

BB: What was your role in initiating the “I Am” series?

CA:You could say that I’m the co-founder of the series. After the discussion with Sara, Juan Pinto (co-chair of our NOMAct K-12 Outreach program) and I were left thinking of ways to make the AEC industry and its opportunities more accessible to students. Given our professional network, access to NOMAct, and the new age of Zoom, we thought, “Why not reach out to our network and see who would be willing to give 30 minutes of their day to talk to some kids?”

BB: Who are some of the people that have lectured?

CA:We kicked off with Juan, who also happens to be a graduate of Platt Tech. It was a great way for the kids to see their future selves through him. We have also been lucky to have Nette Compton (landscape architect and president/CEO of Mill River Park Collaborative), Rene Martinez, PE (electrical engineer and co-owner of DME Design), and Thaddeus Stewart, AIA (architect and principal of Integrated Design & Construction).

BB: What has been the most successful aspect of the program thus far?

CA: Being able to break the boundaries between the professional and educational worlds through communication has been very rewarding, as well as watching students be more at ease having in-depth conversations with professionals. It prepares them for future job interviews and has even led to opportunities including scholarships and paid internships.

Connection 20

BB: Was there anything that surprised you?

CA:The willingness of the kids to learn and ask questions. At first, they were a little reluctant to speak, but once we got the ball rolling, the kids opened right up!

BB: Where are you looking to improve the program?

CA:Visibility! We launched in collaboration with Platt Tech, which has expanded our reach to the Connecticut tech schools. Ideally, we’d like to reach more classes throughout the Connecticut public schools. Given that the series is on Zoom, it’s easily accessible for all to join.

BB: How do you think the “I Am” series can promote EDI and belonging within the architecture profession?

CA: The series highlights the different paths toward a career in the AEC industry and educates students on the various available career options. For example, what is the difference between an accredited five-year Bachelor of Architecture program and an unaccredited four-year Bachelor of Science in Architecture? Given the cost of higher education today, it’s important for students to fully understand the financial impacts of the different available paths.

We also show students the increasing diversity that exists within the AEC industry through our lecturers themselves. We want them to see not only that they can be part of the AEC industry but also that they can excel and take a leadership position.

BB: Do you have any recommendations for others that are considering starting similar programs?

CA: Just do it! Start by forming relationships with schools and educators and go from there. You’ll find that professionals are more than willing to talk about themselves and there’s never a lack of participants!

BB: Tell me about the University of Hartford summer program for high-school kids and the scholarship, and how it ties into the “I Am” series.

CA: Thanks to our sponsors, we’ve been able to sponsor a full scholarship for a student to attend the UHart Architecture Summer Institute. It’s a fully immersive program for highschool students and gives snippets of what pursuing an

architecture degree could be like. A part of the series highlights different resources available to students that they may not be aware of, including NOMAct scholarships, ACE mentoring, and other internship opportunities.

The adjacent picture is the work of this year’s scholarship recipient, Mariangel Quiros. The work includes site visit perspective sketches, diagrammatic explorations, and physical models made during the duration of the program.

BB: How does your program tie in to Dominique’s efforts with Architecture Workshops?

CA: An important thing for organizations to recognize is that we can’t do it all. However, we can support, collaborate, and raise awareness of others working toward the same goal. Given the funds raised this year through sponsorships, we were able to contribute to Architecture Workshops. We also used our platform to make others aware of not only Dominique’s effort but the opportunities available within their program. The grant from NOMAct and other organizations drove down costs for kids to attend the summer camp.

BB: Tell me about the student who signed up for architecture school after hearing a presentation about VDC.

CA: I guess we didn’t fully realize the impact these conversations would have on students. You start off saying, “Let’s try this out and hope it helps in any small way.” In this case, after Juan’s presentation, a student from the audience committed to going to school for architecture. Ultimately, they were impressed with the versatility of an architectural degree and inspired by the different pathways available. We were all proud to help make that possible.

More information can be found at http://www.nomact. org/k-12-outreach

Vol. 20, Issue 03 2022 21

Brian Baril, AIA

Baril is a preconstruction manager with A/Z Corporation, a construction management/design build company in North Stonington, Connecticut. He serves on the Preconstruction Team with a focus on applying design principles to the estimating process. He is the young architect representative for Connecticut.

Conversations on accessibility, empathy and implicit bias

More than one billion people across the world experience a form of disability. In the United States alone, one in four adults live with at least one disability. With the great foundation laid by the ADA and universal design, there have been significant strides toward equal access across multiple facets of civil justice. Disability rights advocates and AIA associates Ricardo León and Richard Sternadori both consider that there is still work to do in the realms of implicit bias and ableism.

Ricardo León, Assoc. AIA, is an architectural designer at Baldridge Architects in Austin, Texas and has a Master of Architecture from Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation and a Bachelor of Science in Architecture from the University of Texas at Arlington. His perspective aligns with that of JSA/MIXdesign. Quoting Joel Sanders, FAIA, he argues that “what makes someone disabled is not their medical condition, but ableism, whose ramifications lead to barriers that prevent people with disabilities from accessing the built environment.”

Richard Sternadori, Assoc. AIA, has been senior education coordinator and research director for the University of Missouri (MU) Department of Architectural Studies, Great Plains ADA

Center since 2008. He holds a Master of Architecture from MU where he is honorary faculty. He also has a Master of Education in Counseling Psychology, with a specialty in disability rehabilitation.

Gabriella Bermea (GB): How would you describe the impact of implicit biases challenging accessibility today?

Ricardo León (RL): Accessibility is just one part of this topic of implicit bias. It is the direct interface of how we translate our work with people with disabilities. Architects rely heavily on code and ADA to resolve our needs, but the conversations we have when designing and making decisions create spaces that are for a certain audience. Disability is something I deal with every single day. It is not something I can turn off. I am living and I am disabled. This is my life and how I navigate.

Richard Sternadori (RS): We are grateful to be working with organizations like AIA, NOMA, and the International Code Council on a national level toward impact. Learners begin to see the complexity and nuances of what we can do as designers. Often, the content points back to an implicit bias, and how disabilities impact those with them, as well as families,

Connection 22

Above: Ricardo León

Above: Richard Sternadori

and friends. Living with a disability is when people begin to ‘get it.’ Understanding that about the reader is important. What will compel our designers to want to know more?

GB: Where are our gaps?

RL: Representation is important. It is about who you bring to the table in design and while talking about its impact on accessibility. Accessibility is not a topic as highly focused in school. It is hard to combat implicit biases because no one is in our corner, fighting for our voice, and thinking about design solutions accessibly.

RS: We are not requiring training for students and catching biases early on. We can open the doors of exploration for accessibility conversations. The accessibility foundation of education is sorely lacking when it comes to having designers conversant in building codes and ADA design standards. After graduation, interns are not prepared for the realities of construction permitting. Eliminating biases must come early in architectural education.

GB: What are your words of advice for the future of universal design and social equity?

RL: We must understand the needs of our disabled audience and for what we are fighting. You must understand your own implicit biases and what language to use; you must also have respect for people with disabilities and trust what they are saying and believe in it. It is not clear cut; we do not all have the same story. Each person has a unique experience based on their forms of disability, and ethnic and gender orientation. Understanding people’s perspectives is the first step toward … fighting injustices. There must be dialogue and allyship. There’s work on the architect’s part to get out there and understand different perspectives. Immerse yourself in what it is that the disability community is talking about and fighting for, in any way you can define.

RS: The educational process must look beyond mobility to include other impairments like chemical sensitivities, hearing, and visual impairments. There are nuances. Architects do not always understand what it means to have a disability when using a building. It is an implicit bias within an implicit bias. We must target empathy and education.

GB: How can we improve as a profession toward a socially accessible environment?

RL: To truly look toward change, we must look beyond the ADA. Although it is great in its efforts, there is a need to think beyond the existing guidelines and look internally at the impact architects and designers have on the built environment. We have to be a part of the solution.

RS: We need to impact professional development and licensure with mandatory educational credit hours in accessible design. Licensure candidates are having to learn about the minimums too late. The ADA and adopted building codes are the line in the sand, the bare minimums. Improving requires education. We must compel people to seek greater perspectives.

Given the advice from both Ricardo and Richard, we must challenge ourselves, for the future of our work, to decide how design will help or hurt the environments around us and accessibility for all. Architects and designers have a social responsibility to deepen the understanding of the perspectives of a wide audience of people with different identities and embodiments. There is a need for inclusivity to bring the voices of all persons together to create social equity and inclusive public space from architectural education to professional practice.

Resources:

• Stella Young, “I’m not your inspiration, thank you very much”

• Crip Camp – Netflix

• Body Politics: Social Equity and Inclusive Public Space

Vol. 20, Issue 03 2022 23

Gabriella Bermea, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP BD+C

Gabriella Bermea, AIA Bermea is a design architect at VLK Architects in Austin, Texas, specializing in the design Pre-K-12 educational facilities. She is the 2022 co-chair of the Texas Society of Architects Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Committee.

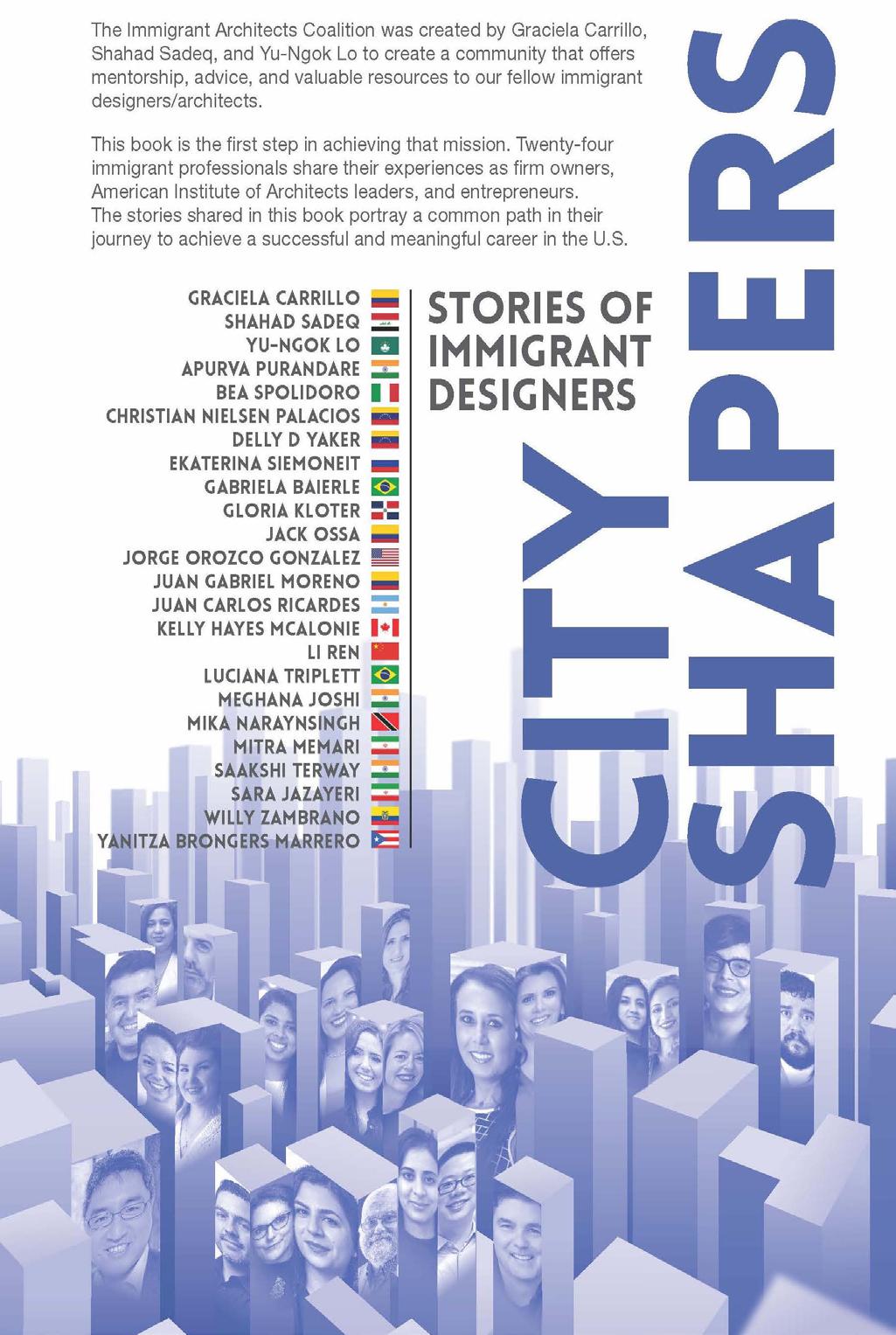

The voice of the immigrant community: An interview with the Immigrant Architects Coalition co-founders

IAC (Immigrant Architects Coalition): The Immigrants Architects Coalition (IAC) was created after presenting a successful session at A19 “How Immigrant Architects Can Prosper In the U.S.?.” The session organizer Yu-Ngok Lo, FAIA, and session speakers Graciela Carrillo, AIA and Shahad Sadeq, Assoc. AIA decided to continue the mission of helping their fellow immigrant architects. As a result, the Immigrant Architects Coalition was created.

The IAC’s mission is to help and provide resources for immigrant architects to achieve a prosperous career in the U.S. The IAC provides support to other immigrant architects through mentoring and conducting informational sessions through local AIA chapters and architectural schools. The IAC is developing a comprehensive guide that highlights different topics of interest on immigrant professionals that are starting the career path in this country. The guide can be found on the IAC website. Click Here

Graciela Carrillo, AIA, LEED AP BD+C

Carrillo is a senior manager at Nassau BOCES in Garden City, New York. Carrillo serves as the AIA New York State representative for the AIA National Strategic Council, the past president of the AIA Long Island Chapter, and the Chapter’s Women In Architecture co-founder and Co-Chair. Carrillo is one of the cofounders of the Immigrant Architects Coalition. Carrillo was the recipient of the AIA NYS Young Architect Award, the AIA Young Architect Award, and she was an honoree of the Top 50 Women in Business in Long Island.

Shahad Sadeq, Assoc. AIA

Sadeq is the executive director at AIA Springfield Chapter, Missouri and adjunct professor at Drury University. Sadeq co-founded the EDI task force at AIA Dallas and the Equity in Architecture Committee at AIA Kansas City. She is one of the co-founders of the Immigrant Architects Coalition.

Yu-Ngok Lo, FAIA, CDT, LEED AP

Lo is the principal at YNL Architects in Culver City, California. Lo’s work received numerous design awards. His work is also published at various national and international publications such as ArchDaily, Hinge Magazine Hong Kong, Hospitality-Interiors UK, Conde Taiwan, and CommArch USA. Lo is one of the cofounders of the Immigrant Architects Coalition.

Graciela Carrillo(GC): To be successful in the architecture profession, immigrant architects must overcome many obstacles throughout their careers. Some of those obstacles are their education, cultural challenges, and finances.

Even if you attended the best architectural school in your home country, validating your architectural foreign degree will be a challenge. Each State has its own requirements regarding

education and licensing, so if an immigrant architect doesn’t have a mentor to help in this process, it will be a difficult one. It is achievable, be prepared to spend some time getting familiarized with State requirements, NCARB requirements, and make sure your licensing board from your home country is willing to communicate with NCARB. Besides your degree validation, immigrant architects must learn the imperial measuring system, as opposed to the metric system, as well as codes and standards.

Cultural challenges play an essential role in the performance of immigrant architects. Some of us moved to the US without our family, our first support system, and we needed to adapt to a

Connection 24

Saakshi Terway(ST) : What are some of the common obstacles / challenges that are unique to immigrant professionals and what are the resources available for the immigrant community

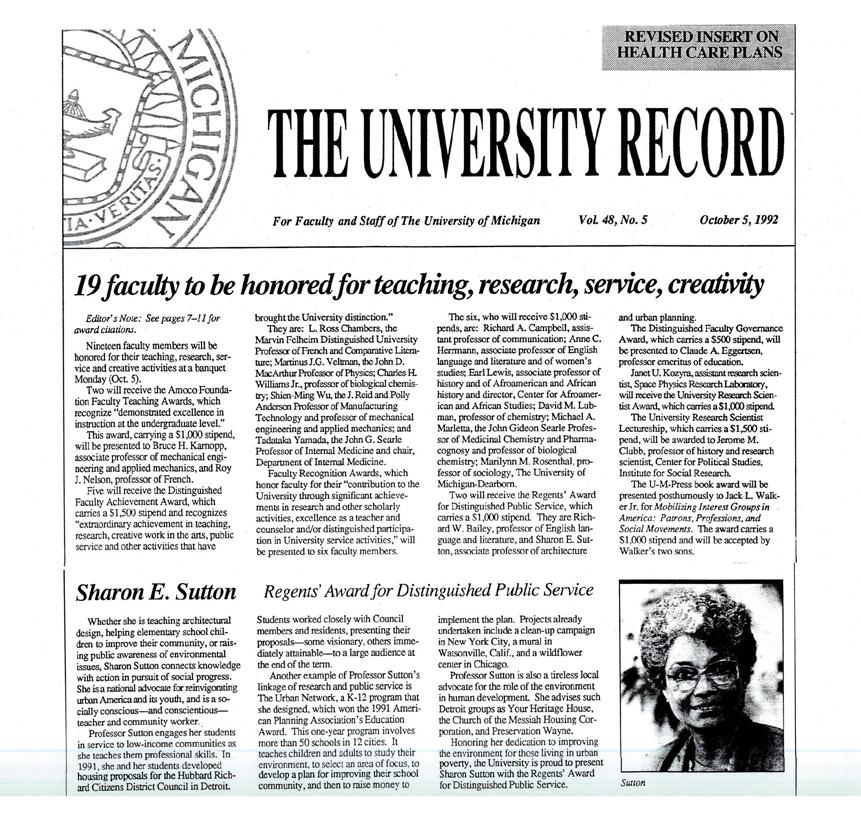

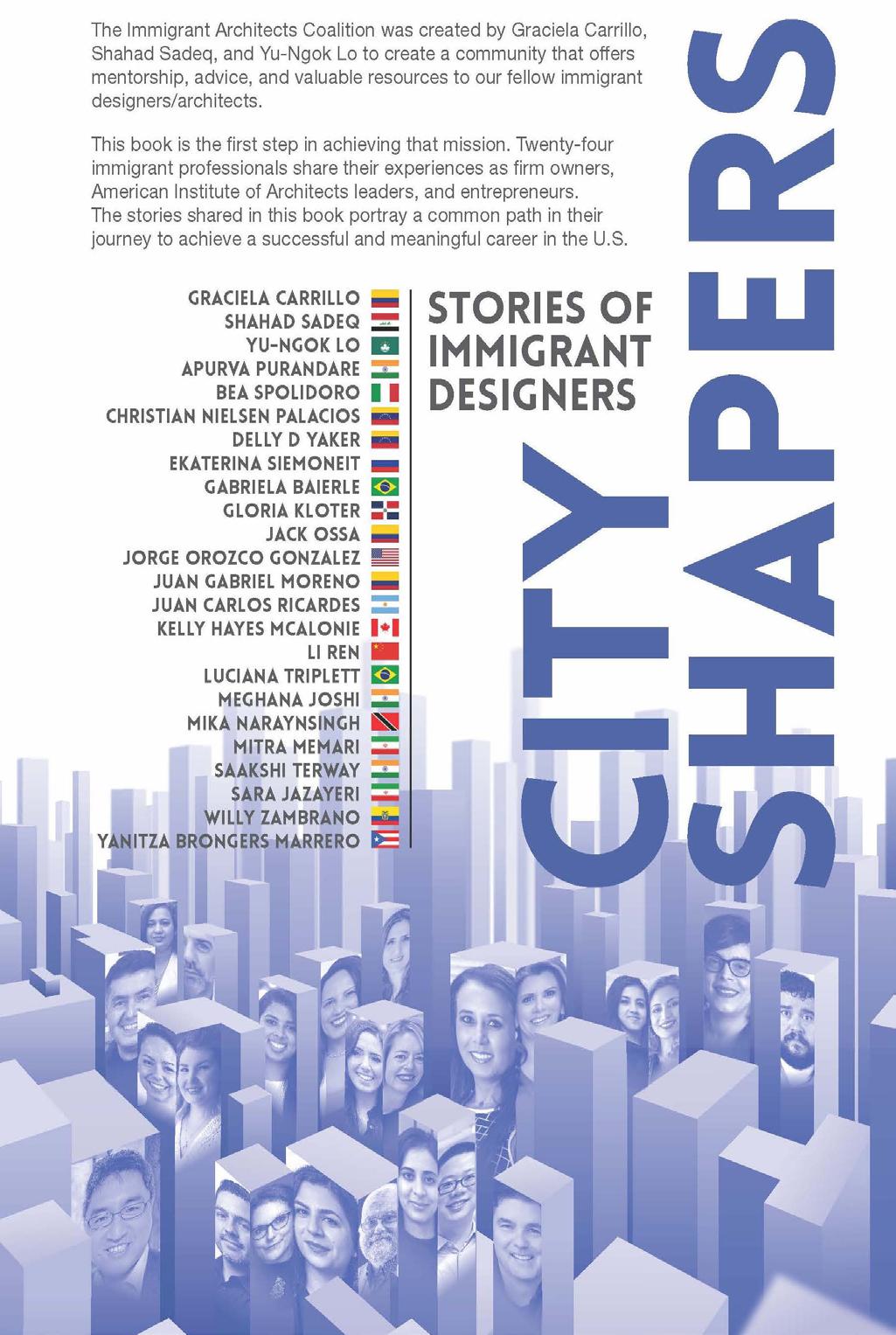

Above: Cover of book

new culture, language, and interaction with different religions and politics. Blending in the “new” culture may be difficult for some, depending on where they are coming from, and easier for others from similar cultures. Still, leaving your home, your family, and your friends puts you out of your comfort zone, and this is one of the most complicated challenges immigrant architects could overcome.

Lastly, the financial challenges for some may be stressful. Adapting to a new life and renting a place means you have to furnish your new home, buy a car (if transportation means are unavailable in your town/city), and pay for your licensure process. Some immigrant architects are also supporting their families abroad or saving funds to bring them to the US, so all these factors become challenging while trying to adapt to a new culture and work.

Above: Back cover of book

Shahad Sadeq (SS): No one except yourself will know how to cultivate and expand your potential. Self-advocacy presents you with the opportunity to demonstrate what you value and the measure of your capabilities. Those who work around you, above you, and for you can only deal with the knowns, not the guesses. Do not expect them to pay attention to you and your work. In America, individualism is the norm. You speak for and sell yourself. The quicker you grasp that, the faster you will succeed in any industry.

The immigrant architects’ first task is to recognize the culture they occupy. Once you know how people communicate, you can learn that your background will have limits that clash with your current culture. Take a moment and recognize that and then adapt. Second, create relationships to help you in your self-advocacy. Speaking up for yourself is half the battle; the other is having people vouch for you. Make sure you surround yourself with people who can give you honest feedback that has your best interest in mind. Third, do not take things personally. Self-advocacy is not because you are not valued.

Vol. 20, Issue 03 2022 25

Saakshi Terway (ST): Why is self-advocacy important? What are the tips for immigrant professionals to effectively advocate for himself / herself

It is just the way American business culture works. Lastly, be empathetic with yourself and others as you figure out your career growth. It is a mixed blessing to stretch and challenge yourself. Growth is immensely beneficial, but it calls for sacrifice. The sacrifice is comfort.

In conclusion, self-advocacy ensures you have the power to shape the vision you have of your life. That said, it is equally important to recruit mentors and peer advocates on your way there. Finally, get comfortable with being uncomfortable and watch yourself soar.

Yu-Ngok Lo (YL): Establishing your own firm is never easy. It is especially hard for people not born in the U.S. Immigrant architects coming to the United States face many obstacles: learning a new language, understanding a new culture, obtaining the appropriate education and work visas, and competing with Americans for intern positions at prominent architectural firms. The biggest challenge for me is building relationships with clients and maintaining a sustainable practice.

Many international students and emerging professionals struggle to get sound advice on how to start his / her own firm and the obstacles and rewards that come with it. What is especially valuable for them is to receive that advice from someone who has already experienced what they are going through, someone who has succeeded in achieving this dream. That is one of our goals at Immigrant Architects Coalition.

ST : What project(s) is IAC working on?

IAC: The IAC just released the book “City Shapers: Stories of Immigrant Designers”. This book is the first step in achieving the IAC mission. Twenty-four immigrant professionals share their experiences as firm owners, American Institute of Architects leaders, and entrepreneurs. The stories shared in this book portray a typical path in their journey to achieve a successful and meaningful career in the U.S.

The IAC is also working on launching a mentoring program in the upcoming year, where mentors can provide advice about licensure, NCARB accreditation, cultural bias, employment skills, opportunities, etc.

Some future projects include a podcast (we are looking for people passionate about radio), Book part II and a scholarship for immigrant architects.

ST: Anything else you would like to add?

IAC: We are actively looking for people of all backgrounds (regardless of your nationality or immigration status) to join our community. As mentioned previously, we are planning on launching multiple projects next year, and we need all the help we can get from passionate people like you.

Connection 26

Saakshi Terway (ST): Tell us about the unique challenges for immigrants to start his / her own firm?

Saakshi Terway, Assoc. AIA, LEED GA Saakshi is a licensed architect from India and designer at Wiencek + Associates in Washington, D.C. . She is a co-author of the book “City Shapers: Stories of Immigrant Designers”, and a contributing author for the IAC Guidebook.

Above: Immigrant Architects Coalition (IAC) co-founders

Efforts in education to improve the architecture pipeline

Earlier this summer, on the plane ride home from the 2022 AIA Conference on Architecture in Chicago, I was reflecting on the June 23rd keynote, a conversation between Jeanne Gang, Vishaan Chakrabarti, and Renee Cheng. The discussion focused at length on diversity in architecture, and more specifically diversity in the pipeline to the profession. The consensus across the stage was the need to make the profession attractive to younger children. “There are so many brains at work that aren’t

even thinking that architecture is a potential career, or that they have agency to be an architect,” said Cheng. “How many young students have met an architect or thought about it as a career? Our job is to make it accessible.”

As a young female entering college to pursue a degree in architecture, I may have been the outlier as someone who had never met an architect growing up. My exposure probably

Vol. 20, Issue 03 2022 27

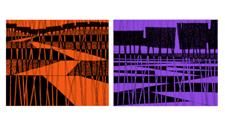

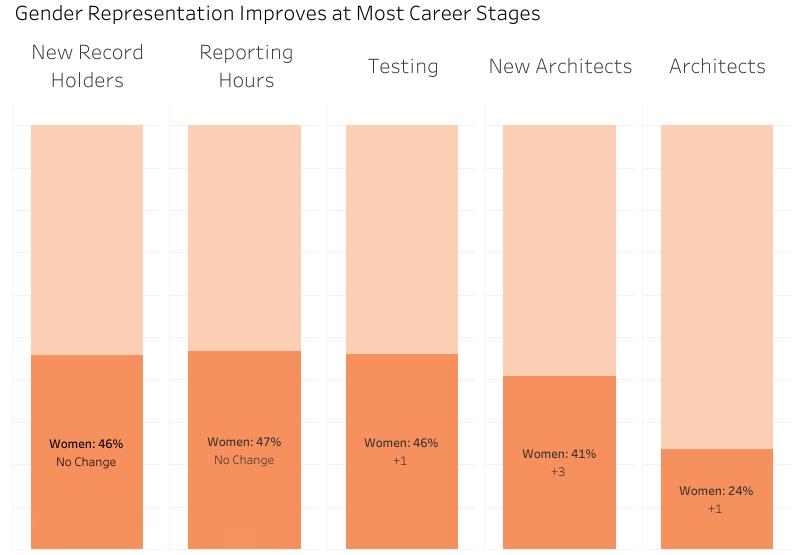

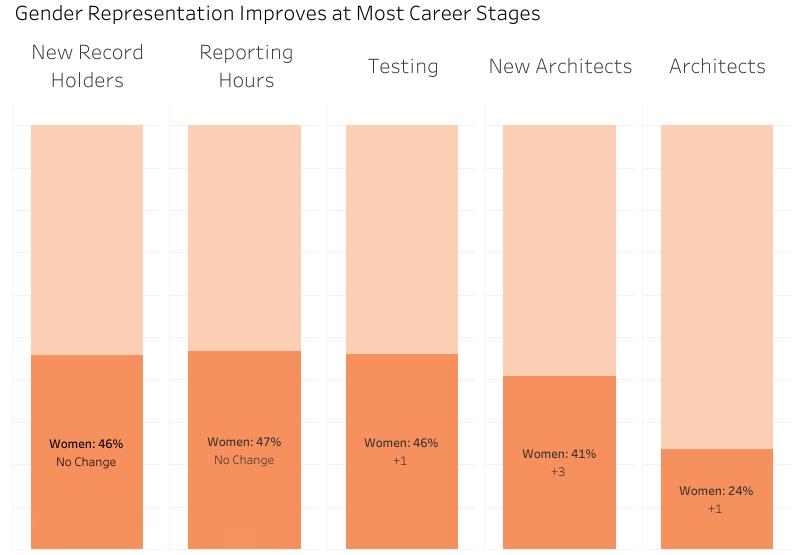

Above: Gender Representation shows improvement at most career stages with the highest growth in newly licensed architects. Image courtesy of NCARB.

just looped back to watching HGTV a lot with my mother I remember being very nervous that I would be the only girl in my architecture cohort when I walked into our studio space the first day of classes. I was wearing an oversized T-shirt with my sorority letters plastered across my chest. Every sorority did this at Texas A&M on the first day to have an excuse to talk to someone wearing the same shirt as an easy way to meet new people. To my surprise, when I walked in that day, I wasn’t the only one wearing some brightly colored T-shirt. There was another girl. I sat next to her and, as we talked, other girls started to trickle in. Today, the architecture program at Texas A&M is over 55% women.

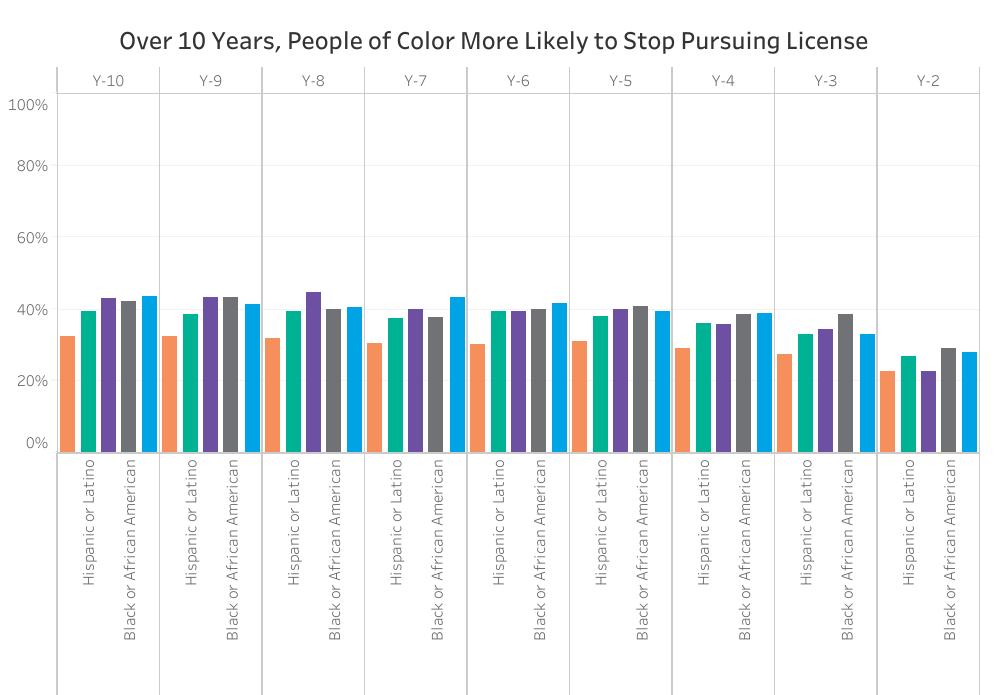

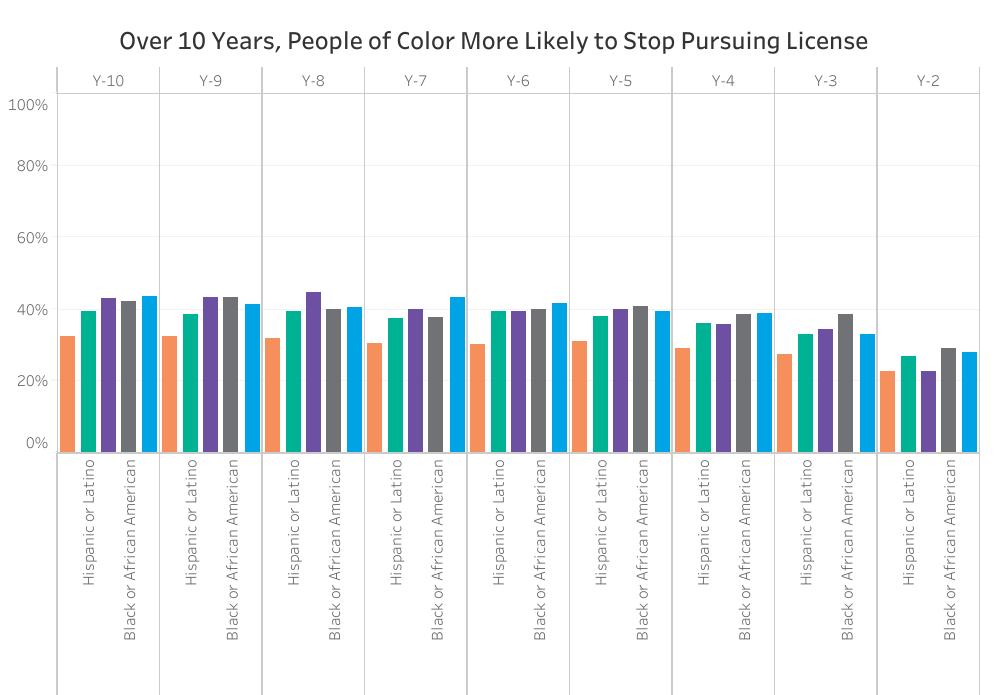

While other universities are seeing the same increase in female students as Texas A&M, this isn’t seen when data reveals women only make up 24% of all licensed architects.1 The influx of women entering school does bode well for the profession, even if we must wait a few years for those students to graduate and enter the workforce. However, when focusing on licensure, 36% of those on the path to licensure do not complete the process. This number increases when looking at certain

minority groups with 43% of African American and 40% of Hispanic or Latino candidates starting the process but not obtaining licensure 2

The Integrated Path to Licensure (IPAL) program aims to combat this by allowing students to receive their license upon graduation from an accredited degree program. Texas A&M University is starting its second year of offering students the option to apply for the IPAL program. When speaking with Dr. Valerian Miranda, the current IPAL & AXP Advisor for the Department of Architecture at Texas A&M, I learned that the initial interest exceeded his high hopes for the program. The process of getting approved to start an IPAL program requires close coordination between NCARB and the respective universities. Initially, the plan was for Texas A&M to slowly ramp up enrollment in the program, starting at five students the first year and progressing forward until they reached 20 new students per year.

“Well, so much for plans,” Dr. Miranda said. “Out of the second-year students, I had 13 who met and exceeded all the

Connection 28

Above: Over a 10 year period, people of color are more likely to stop pursuing licensure. Image courtesy of NCARB.

application criteria. Then, I went to the incoming Master of Architecture class and about 15 of them already had NCARB records. When I met with them individually, I found two of them already had 3500 AXP hours and many others were in the 2500–3000 range.” It turns out, many of the students Dr. Miranda met with had taken a gap year before returning to get their accredited degree purely out of a need to work to pay for school. By getting the experience and then enrolling in an IPAL program once back at school, they are expected to test during their two years in the graduate program and graduate licensed. “We have tremendous support for our program from TBAE Texas Board of Architectural Examiners,” said Dr. Miranda. “It makes the profession of architecture more accessible for people of lesser financial means because you must work to earn AXP hours and in working you must get paid. That helps pay for school and get licensed faster. Inherently, this program is ideal for students of lesser means.”

In addition to being a positive impact for lower-income students, Dr. Miranda is confident in the long-term effects on diversity the profession will see from the program. The number of students that are currently enrolled in IPAL and are considered Hispanic, or a Person of Color, is nearly 3x the university average and over 65% are female. Dr. Miranda added, “I think that’s a great feather in the cap of this program. It is attracting female and minority students who are proving to be very committed to architecture.”