Research Posters from the NYS Youth Justice Institute

Elevating Equity and Fostering Healing Conference

March 27th & 28th, 2024

March 27th & 28th, 2024

•Healing in this document is defined as “personal and societal recovery from the lasting effects of oppression and systemic racism experienced over generations” and youth report a variety of practices that help them heal

•Trauma-Informed Care perspectives often causes young people to fall into a medical model of “treating” symptoms of trauma instead of addressing the root causes

•Healing-Centered Engagement’s expansive framework understands trauma as individual and collective experience and highlights and offers responses that focus on healing through strengths-focused, culturally appropriate supports, and building agency

•Access to quality green spaces in urban communities has positive impacts on youth mental health and well-being

•As experts in their own experience, youth report that civic action to address social conditions and oppression, such as advocacy and organizing in their communities is one of the most effective strategies in supporting their healing and well-being

9,11

•Often young people are not engaged in creating programs, interventions, or community conditions that contribute to their well-being

•Following a Participatory Action model and taking a “bythemforthem”approach can increase equity

•Engage young people, especially those from marginalized communities in program development, implementation, and policymaking around increasing well-being gives them a sense of autonomy, and the opportunity to advocate for change in the institutions that caused them harm

13,14

•Youth report that healing requires engaging in conversations to strengthen their connections to their communities, elders, and cultures

•Youthspacesrefer to spaces in public areas, such as schools, community centers, or designated outdoor spaces where young people engage in focus groups to discuss culture, structural racism, and barriers to wellbeing for themselves and other young people in their communities

•Understanding one’s place in society is necessary for developing personal agency and coping skills to handle complex manifestations of trauma

•Youth report that perceptions of various community spaces as dangerous limits their use of the spaces, so there is a need to promote safety in public spaces through investment in urban green spaces

•Because youth living in urban areas are reluctant to use public spaces out of fear of violence in their community, it is necessary to address and promote solutions to community violence

•Transgender and gender diverse youth report that internet communities foster healing by allowing them to:

•Escape from stigma and violence

•Experience belonging

•Build confidence

•Feel hope

•Give back 10

•Examples: NYS Youth Justice Institute Peer Advisory Council (PAC), Make the Road New York Youth Power Project & School Programs, YMCA Youth in Government

Michaela Webb

Michaela Webb

1.Duncan, S., Horton, H. K., Smith, R. K. A., Purnell, B., Good, L., & Larkin, H. (2023). The Restorative Integral Support (RIS) model: Community-Based integration of Trauma-Informed approaches to advance equity and resilience for boys and men of color. Behavioral Sciences, 13(4), 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13040299

2.Ginwright, S. (2020, December 9). The Future of Healing: Shifting from trauma informed care to healing centered engagement. Medium. https://ginwright.medium.com/the-future-of-healing-shifting-from-trauma-informed-care-to-healing-centered-engagement634f557ce69c

3.Portilla, X. A. (2022). HealingSchoolSystems:VoicesfromtheField.SolutionsforEducationalEquitythroughSocialandEmotional Well-Being.https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED623975

4.Goessling, K. P. (2019). Youth participatory action research, trauma, and the arts: designing youthspaces for equity and healing. InternationalJournalofQualitativeStudiesinEducation, 33(1), 12–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2019.1678783

5.Hamby, S., Elm, J. H. L., Howell, K. H., & Merrick, M. T. (2021). Recognizing the cumulative burden of childhood adversities transforms science and practice for trauma and resilience. AmericanPsychologist, 76(2), 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000763

6.Chavez-Diaz, M., & Lee, N. (2015). Aconceptualmappingofhealingcenteredyouthorganizing:Buildingacaseforhealingjustice. Urban Peace Movement. https://urbanpeacemovement.org/report-title-number-1/

7.Vanaken, G., & Danckaerts, M. (2018). Impact of green space exposure on children’s and Adolescents’ mental health: a Systematic review. InternationalJournalofEnvironmentalResearchandPublicHealth, 15(12), 2668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122668

8.McCormick, R. (2017). Does access to green space impact the mental well-being of children: a systematic review. JournalofPediatric Nursing, 37, 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2017.08.027

9.Commons, R. T. C. (2022b, October 25). How Green Space Fosters safer Communities - Reimagining the Civic Commons - medium. Medium. https://medium.com/reimagining-the-civic-commons/how-green-space-fosters-safer-communities-98e54ddbf80f

10.Austin, A., Craig, S. L., Navega, N., & McInroy, L. B. (2020). It’s my safe space: The life-saving role of the internet in the lives of transgender and gender diverse youth. Internationaljournaloftransgenderhealth, 21(1), 33-44.

11.Rayner, S. R., Thielking, M. T., & Lough, R. L. (2018). A new paradigm of youth recovery: Implications for youth mental health service provision. Australian Journal of Psychology, 70. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12206

12.Youth-Centered Strategies for Hope, Healing and Health - The Children's Partnership. (2022). The Children’s Partnership. https://childrenspartnership.org/research/youth-centered-strategies-for-hope-healing-and-health/

13.Youthrex. Evidence Brief Healing Practices for Black & Racialized Youth. (2018). https://cac-cae.ca/wp-content/uploads/YouthREXEB-Healing-Practices-for-Black-Racialized-Youth.pdf

14.Allen, H. S. (2021, April 14). #SAYHERNAME panelexploresphotography’sroleinactivism. Popular Photography. https://www.popphoto.com/american-photo/what-is-photographys-role-in-activism/

•Trauma is heavily influenced by institutional violence grounded in a legacy of structural racism

•Structural racism refers to the systemic, institutionalized forms of discrimination and inequality embedded within societal structures, policies, and practices

•Structural racism limits access to opportunities through systems including:

•Healthcare,

•Criminal Justice,

•Housing,

•Education,

•Employment, and

•Income

•This has disproportionately burdened Black, Indigenous and other racially and ethnically marginalized people of color socially, politically and economically

•Generational trauma—in which trauma extends across generations from experiences of significant adversity including colonization, slavery, displacement, or systemic oppression has greatly affected communities of color

•This legacy of trauma continues to affect the well-being of youth of color (YOC)

•Centering race in healing and trauma can promote solidarity, allyship, and healing across different identities

•Youthspacesprovide YOC safe public spaces to speak with others about structural racism and promote healing

•Youthspacepractices provide opportunities for youth to develop research, artistic, technical, relational, personal, and leadership skills

•Justice involvement often intersects with preexisting systemic inequalities and experiences of marginalization, exacerbating the challenges faced by youth of color

•YOC in facilities may face barriers to healing including limited access to mental health services, stigma associated with criminalization, and ongoing exposure to violence and trauma within their communities

•Practitioners working with justice-involved youth of color should employ healing centered engagement practices that prioritize safety, empowerment, and cultural sensitivity

•Policymakers have a responsibility to enact policies that promote equity, justice, and healing for youth of color who are justice-involved. This may look like:

•Implementing diversion programs that prioritize community-based alternatives to incarceration,

•Investing in culturally responsive mental health services, and

•Addressing the root causes of systemic inequalities that contribute to disproportionate justice involvement among youth of color

•LGBTQ+ youth are overrepresented in the justice system

•39.4% of girls in juvenile justice facilities identify as LGB

•85% of LGBT and gender non-conforming youth in facilities are YOC

•LGBTQ+ YOC often express the importance of safe spaces where they are not othered and instead affirmed in their identities

•Safe spaces for LGBTQ youth of color to heal from trauma involve cultural competency/sensitivity, peer support, and collaboration with community resources

•Successful integration for LGBTQ youth of color involves not only being accepted into mainstream society but also feeling a sense of belonging, agency, and affirmation within their racial, ethnic, cultural, and LGBTQ communities

•We can combat othering by amplifying diverse voices and experiences through education, advocacy, and media representation

9,10

•Only then can stereotypes be dismantled and foster inclusivity

9,10

•LGBTQ+ YOC have 2 "Talks" with their caregivers because of their intersecting identity. One conversation is centered around how to navigate the world as a YOC and the other is how to navigate the world in their queerness

Ashley Hall

Ashley Hall

1. Allen Mallett, C., Fukushima Tedor, M., & Quinn, L. M. (2019). Race/ethnicity, citizenship status, and crime examined through trauma experiences among young adults in the United States. JournalofEthnicityinCriminalJustice, 17(2), 110–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377938.2019.1570413

2. Alvarez, A., & Tulino, D. (2023). Racial conflict, violence and trauma: Why race dialogues are critical to healing. InternationalJournalofQualitativeStudiesinEducation, 36(8), 1487–1495. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2022.2025480

3. Anderson, R. E., & Stevenson, H. C. (2019). Recasting racial stress and trauma: Theorizing the healing potential of racial socialization in families. AmericanPsychologist, 74(1), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000392

4. Goessling, K. P. (2019). Youth participatory action research, trauma, and the arts: Designing youthspaces for equity and healing. InternationalJournalofQualitativeStudiesinEducation, 33(1), 12–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2019.1678783

5. Lockwood, A., Peck, J. H., Wolff, K. T., & Baglivio, M. T. (2021). Understanding adverse childhood experiences and juvenile court outcomes: The moderating role of Race and ethnicity. YouthViolenceandJuvenileJustice, 20(2), 83–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/15412040211063437

6. Mountz, S. E. (2016). That’s the sound of the police. Affilia, 31(3), 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109916641161

7. Movement Advancement Project. (2017). Unjust: LGBTQ Youth Incarcerated in the Juvenile Justice System. https://www.lgbtmap.org/file/lgbtq-incarcerated-youth.pdf

8. Wells, R., Wray-Lake, L., Plummer, J. A., & Abrams, L. S. (2023). “I feel safe out here”: Youth Perspectives on communitybased organizations in urban neighborhoods. JournaloftheSocietyforSocialWorkandResearch, 14(2), 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1086/714132

9. Borges, S. (2021). “We have to do a lot of healing”: LGBTQ migrant Latinas resisting and healing from systemic violence. LivesThatResistTelling, 38–53. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003142171-3

10. Erney, R., & Weber, K. (2018). Not all Children are Straight and White: Strategies for Serving Youth of Color in Out-ofHome care who Identify as LGBTQ. Child Welfare, Suppl. SpecialIssue:SexualOrientation,GenderIdentity/Expression,and ChildWelfare,96(2), 151-177. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48624548

•Withdrawal from social settings and friends

•Withdrawal from activities

•Sudden mood swings

•Community-Based Interventions focus on providing youth with a larger support network to bring youth a sense of belonging and provide positive rolemodels such as mentors

•The 2021 youth suicide rate is 11 per 100,000

•Suicide rates for youth ages 10-24 has increased by 52% between 2000-2021

•Academic decline

•Changes to appearance and behavior

•Self-harm

•Family instability

•Substance use

•Academic pressure

•Bullying and cyberbullying

•Youth who perceive racial and ethnic discrimination are up to 3 times more likely to have suicidal ideations compared to youth who do not perceive discrimination

•From 2018-2021, Black youth ages 10-19 saw a 78% increase in suicides

•LGBTQ+ teens in 2021 were 3 times more likely to consider suicide, make plans, and attempt suicide compared to their heterosexual peers

•Stressors include discrimination, partner violence, at-home violence, homelessness, and victimization

•Social isolation

•Partner violence

•Mental health conditions which can be exacerbated by these other risk factors

•Black children ages 5-12 are twice as likely to die from suicide compared to their White peers

•Interventions for Black Youth: Faith Organizations, Family Support, and Developing a Strong Racial Identity

•Interventions for LGBTQIA+ Youth:

•LGBTQ+ Affirming School Policies,

•LGBTQ+ Inclusive Curriculum,

•Family and Peer Support, and

•Connections to LGBTQ+ Programs

•Examples: social support from community members and motivational interviewing that seeks to explore and resolve ambivalence

•School-Based Interventions include collaboration between parents, educators, and mental health professionals to provide early screening and intervention as well as ensure that the needs and well-being of the young individual are put first

•Example: Gatekeeper training teaches individuals to recognize warning signs and respond appropriately

•Family-Focused Interventions Families and family dynamics have huge impacts on children's mental well-being. Some models center on improving the family dynamic by helping to build better relationships, communication, trust, and create boundaries

•Example: Problem-solving therapy can help both individuals and families to cope with stressful life situations

•Clinical-based interventions include mental health screenings and seeking therapists, psychiatrists, professional counselors, and even school counselors

•Example: Cognitive-behavioral Therapy (CBT) explores ways to manage negative emotions and change relationships

•Social isolation during the Covid-19 pandemic increased levels of anxiety and depression by 25% in children compared to 2016

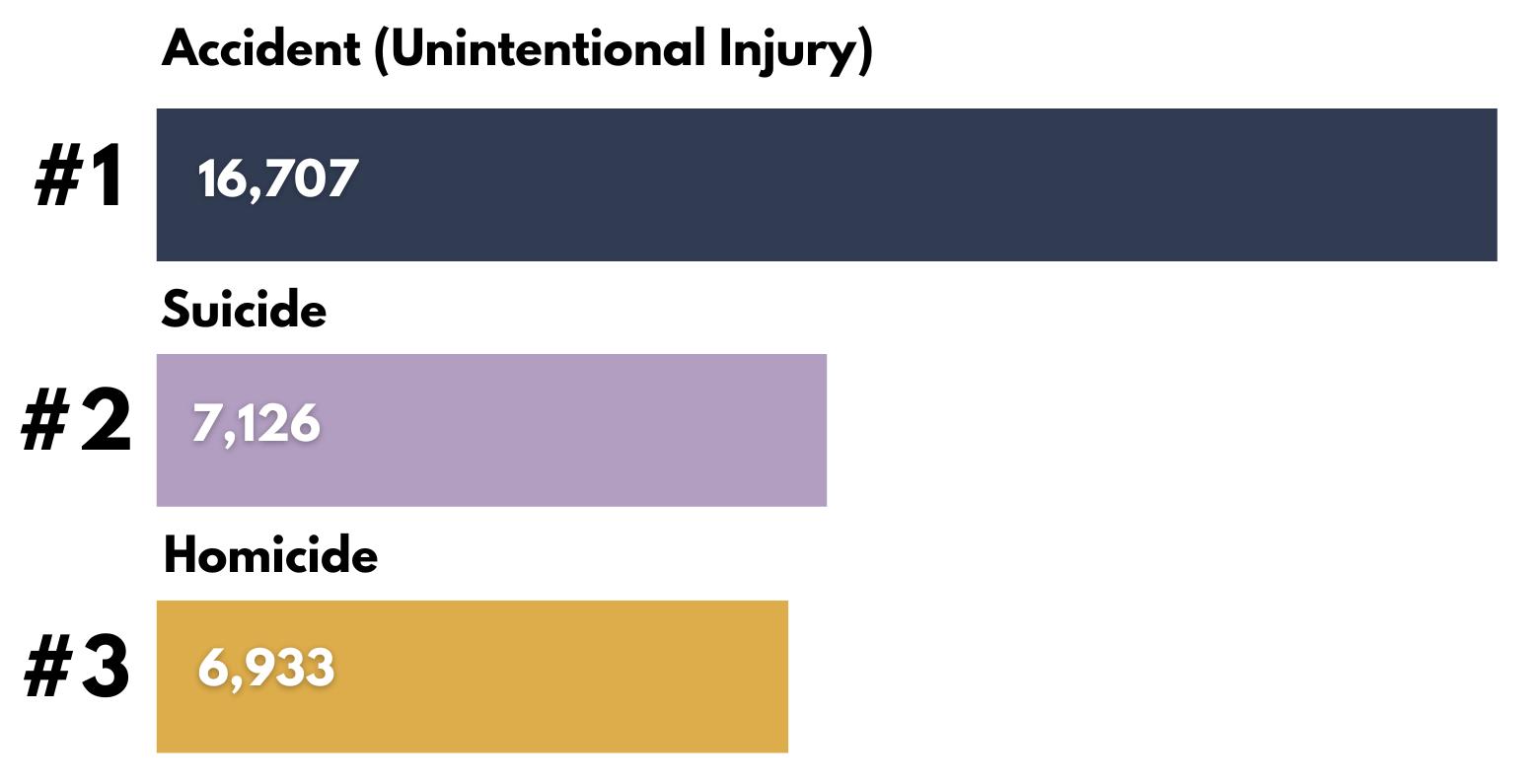

Leading Causes of Death for Youth (Ages, 10-24), 2021

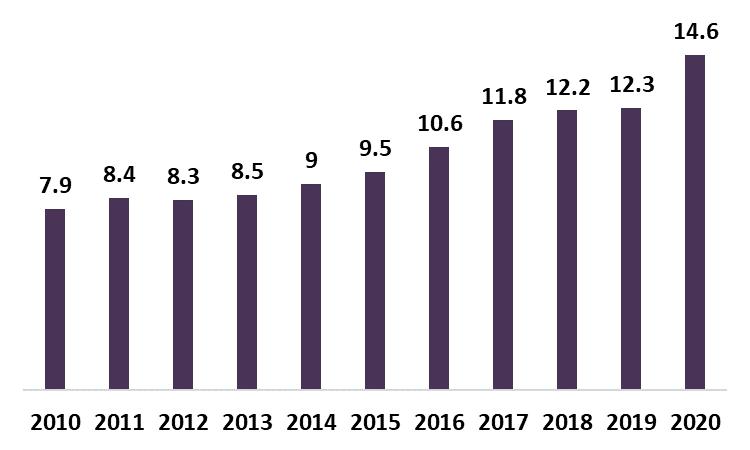

Suicide Death Rates per 100,000 among Black Boys & Young Men (Ages 10-24), 2010-2020

Source:

Morgan Magierski

Morgan Magierski

1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (n.d.). Suicide Facts. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/index.html

2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (n.d.). Risk and Protective Factors. SuicidePrevention. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/factors/index.html

3.Bilsen, J. (2018). Suicide and youth: risk factors. FrontiersinPsychiatry, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00540

4.Sheftall, A. H. (2023, April 11). TheTragedyofBlackYouthSuicide. Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/news/tragedy-black-youth-suicide

5.Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. (2023, August 23). StillRingingtheAlarm:AnEnduringCalltoActionforBlack YouthSuicidePrevention. Johns Hopkins University. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2023/still-ringing-the-alarm-an-enduring-call-to-actionfor-black-youth-suicide-prevention

6.Gorse, M. M. (2020). Risk and Protective Factors to LGBTQ+ Youth Suicide: A Review of the literature. ChildandAdolescentSocial WorkJournal, 39(1), 17–28.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00710-3

7.Williams, A. J., Arcelus, J., Townsend, E., & Michail, M. (2019). Examining risk factors for self-harm and suicide in LGBTQ+ young people: a systematic review protocol. BMJOpen, 9(11), e031541. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031541

8.Schnitzer, P. G., Dykstra, H., & Collier, A. (2023). The COVID-19 Pandemic and Youth Suicide: 2020–2021. Pediatrics, 151(3).

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-058716

9.Colorado Health Foundation. (2018). What Interventions Help Teens and Young Adults Prevent and Manage Behavioral Health Challenges? RAPIDEVIDENCEREVIEW, 1–29.

https://academyhealth.org/sites/default/files/Rapid_Evidence_Review_Behavioral_HealthJan2018.pdf

10.Colizzi, M., Lasalvia, A., & Ruggeri, M. (2020). Prevention and early intervention in youth mental health: is it time for a multidisciplinary and trans-diagnostic model for care? InternationalJournalofMentalHealthSystems, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-00356-9

11.Southerland, R. (2023, October 17). Strategies for Effective Intervention for At-Risk Teens. ClearforkAcademy.

https://clearforkacademy.com/blog/strategies-for-effective-intervention-for-at-risk-teens/#:~:text=School12.Akkas, F. (2023). Youth suicide risk increased over past decade. ThePewCharitableTrusts. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/researchand-analysis/articles/2023/03/03/youth-suicide-risk-increased-over-past-decade

13.Ehlman, D. C., Yard, E., Stone, D. M., Jones, C. M., & Mack, K. A. (2022). ChangesinSuicideRates- UnitedStates,2019and2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7108a5.htm

14.Moss, S. J., Mizen, S. J., Stelfox, M., Mather, R. B., Fitzgerald, E., Tutelman, P. R., Racine, N., Birnie, K. A., Fiest, K. M., Stelfox, H. T., & Leigh, J. P. (2023). Interventions to improve well-being among children and youth aged 6–17 years during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. BMCMedicine, 21(1).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02828-4