Table of Contents

RABBI ADIR POSY, PAGE 1

The Expanded Beginning of Pesach

SAMIRA MILLER & HADASSAH MILLER ‘26 , PAGE 6 Message of Our Survival

TAMAR SCHEINFELD ‘24, PAGE 8

The Eternal Miracle -

RABBI PINCHOS HECHT, PAGE 11

The Mitzvah D’Oraita of Maggid

RABBI JOSEPH SCHREIBER , PAGE 13 ״…חבושמ

DANIEL SCHREIBER ‘11, PAGE 15

RAV YITZCHAK ETSHALOM, PAGE 19 What a Difference a Letter Makes

YITZY POSY ‘26, PAGE 20

Pesach, Matzah and Maror

AVRAHAM ETSHALOM ‘21, PAGE 23

Seeing Yourself in the Past

RABBI ARYEH KAPLAN & SHALVA KAPLAN ‘23, PAGE 26

Charoset: We Are What We Eat

MRS. RACHELI LUFTGLASS & SALI LUFTGLASS YG 25’, PAGE 30

The Women Who Frame Sefirat Ha’Omer

ךנבל

תדגהו

הז ירה הברמה לכו...״

ןוֹפְרַט יִּבַרְו אָביִקֲע יִּבַרְו הָיְרַזֲע־ןֶּב רָזָעְלֶא יִּבַרְו ַעֻׁשוֹהְי יִּבַרְו רֶזֶעיִלֱא יִּבַרְּב הֶׂשֲעַמ

Dear YULA Family,

At the heart of our Yeshiva are exceptional Rebbeim and Mechanchot who are each driven to inspire our students to achieve greatness and become outstanding B’nai and B’not Torah and leaders in the 21st century. Being part of a Yeshiva community that makes no excuses and goes lifnim mishurat hadin to ensure we maximize learning has been emotionally uplifting and inspiring.

The Gemorah in Pesachim 109a teaches the importance of asking and prompting children to ask questions at the Seder. It gives an example from Rabbi Akiva who would give the children parched grain and walnuts on Erev Pesach precisely so they should not fall asleep and be able to ask questions. It continues by mentioning the tradition of Rabbi Eliezer who would snatch the matzot on the night of Pesach so the children should not fall asleep. The famous 11th century commentator, Rabbi Shmuel Ben Meir, (Rashbam,) explains that food induces drowsiness, so Rabbi Eliezer snatched the matzah to prevent the children from getting tired. This gave them the energy to ask questions throughout the Seder. The Rambam codifies this concept into Halacha in the 7th chapter of Hilchot Pesach U’Matzoh by saying that a parent must mix things up a bit in order to prompt questions by the children so they can say “What is the difference between this night and every other night - Mah Nishtanah

Halaylah HaZeh MiKol Haleilot ”

Similarly, asking questions is an important part of one’s ability to grow in one’s spiritual growth. At YULA, we promote the back and forth of questions and answers in our daily shiurim and classes! At YULA, no question is a bad one, rather it is viewed as an opportunity to inspire our students to continue on their journey of becoming outstanding B’nai and B’not Torah.

I am excited to share with you the Pesach Edition of Divrei Hitorirut – Words of Inspiration. This publication asks many questions and showcases the reasons that makes YULA an inspiring and spiritually uplifting environment.

The publication includes meaningful and engaging Divrei Torah from our YULA community. This year’s theme is ךנבל תדגהו - featuring parent and children’s Divrei Torah.

Wishing the entire YULA family and community a safe and Chag Kasher V’sameach!

Rabbi Arye Sufrin, Head of School

The Expanded Beginning of Pesach

Each Yom Tov in the Jewish calendar offers us the opportunity to engage in Mitzvos that enhance our spiritual experience and deepen our understanding of the character of the chag. The variety of Mitzvos over the course of Pesach allows us to engage deeply with Zman Cheiruseinu both through our performance of the Mitzvos themselves as well as through our analysis of their nature.

One unique aspect of the Mitzvos surrounding Chametz is the unusual way in which the Torah lays out the timing of their performance. The Torah commands usi ראש ךל הארי־אלו ץמח ךל הארי־אלו

ךלבג־לכב, which is one of the places in which the Torah prohibits the ownership of Chametz. The simple understanding of this Pasuk is that we may not own Chametz over the course of the 7 days of the Chag. This notion is further underscored by the first part of the Pasuk that tells us explicitly םימיה תעבש תא לכאי תוצמ, which commands us to eat Matza over course of the seven days of the holiday. As is the case for most Mitzvos that are connected to a particular chag, it would be fair to assume that the prohibition of Chametz would be relevant for all 7 days of Pesach.

However, the Torah then continues and commands us ןושארה םויב ךא

םכיתבמ ראש ותיבשת, which would seem to imply that the Mitzva to destroy Chametz (ותיבשת) occurs on the first day of Pesach even though the previous Pasuk seems to imply that Chametz would already be prohibited by the time the first day of Pesach arrived.

Chazal have several approaches to resolve this contradiction. R’ Yishmael ii interprets this Pasuk to mean that the Mitzva of ותיבשת is related to Erev Pesach based on the fact that the Torah tells us אל יחבז םד ץמח לע טחשת which means that Chametz cannot be extant at the time of the sacrifice of the Korban Pesach which occurs on Erev Pesach. R’ Akiva reaches the same conclusion based on the fact that the classic method of destroying chametz is through burning which is a prohibited Melacha on the first day of Pesachiii .

The common denominator between these approaches is that the

1 תוררועתה

ירבד

word “ןושאר” in the Pasuk describing ותיבשת refers to the day before Pesach as opposed to the first day of Pesach as well.iv The later Mefarshim discuss the implications of this unique reading of the word ןושאר and explore whether the expansion of ןושאר to refer to erev Pesach applies to other Pesach related Mitzvos as well.

Usually, we recite the Bracha of ונייחהש when we perform a Mitzva for the first time in a year. While the Baal Ha’itur vsuggests that we should make the recite ונייחהש when performing Bedikas Chametz which is part of the Mitzva of ותיבשת, the Tur vi quotes the Rosh saying

ךרבמ ןיאש, meaning that we can rely on the ונייחהש that will be recited at the Seder on the first night of Pesach. The Maharshal quoted in the Ta”z vii immediately raises an objection to the Tur’s position, noting that Bedikas Chametz is performed on the 14th of Nissan, which is before Pesach begins.

Since the prohibition of Chametz is also relevant on the 14th of Nissan, there one should logically follow the Baal Ha’itur’s approach and recite ונייחהש on Erev Pesach. The Maharshal finds it difficult to accept that one could make a ונייחהש the 15th of Nissan on a Mitzva that was performed on a completely different day. The Ta”z himself however counters in defense of the Tur and the Rosh explaining that (ןמז

) the time of the prohibition of Chametz was described as “ןושאר” in the Torah in reference to the first day of Pesach. It could therefore logically follow that a Bracha said on the first night of Pesach could apply to the Mitzva that was intended to occur on that day. Put differently, the Ta”z is introducing a fundamental concept which is that the Torah is expanding the envelope of time called “ןושארה םוי” to encompass a 48 hour period when it comes to these Mitzvos. Thus, it is quite plausible that we would allow a Bracha recited on the first night of Pesach to apply to actions taken on the 14th of Nissan.

This expanded envelope of time also seems to be found in the words of the Rambam who writes

. The Rambamviii clearly holds that the prohibition of

2 תוררועתה ירבד

לגרד ןמזא ןניכמסו לגרה ךרוצל איה הקידבהש

ןושאר אנמחר הירק אהד לגרהל סחיתמ רוסיאה

אצמ הלעמלו תועש ששמו שש םדוק לטיב אל םא לע רבע הז ירה ורעיב אלו רועיבה תעשב וחכשו ובלב היהו וילע ותעד היהש ץמח אצמי אלו הארי אל

owning chametz is relevant beginning at midday on Erev Pesach. The Raavad objects, noting that the Torah limits the prohibition of owning Chametz to the seven days of Pesach when the Pasuk tells us הארי אלו םימי תעבש ךלבג־לכב ראש ךל. The Magid Mishna tries to answer that the ם”במר only thinks that ותיבשת is extended to Erev Pesach but not the prohibition of owning Chametzix . However, while this may potentially explain the Rambam, Rashix in Psachim explicitly writes:

תועש ששמ אלא הליכאבו הארי לבב הרותה ןמ רוסא וניא ץמח that the prohibition of eating and owning Chametz exists after midday on erev Pesach. It would seem that the only way Rashi could answer the Raavad’s objection would be to use the construct proposed by the Ta”z which extends “ןושאר םוי” through the 14th of Nissan. Perhaps the simplest way to understand the Rambam’s view is that he also agrees with this approachxi .

If this expanded understanding of “ןושארה םויב” applies to the Mitzva of ותיבשת and הארי לב, it is possible that it also applies to other Mitzvos of Pesach as well. For example, the Torah tells us that we must tell the story of Pesach xii ”אוהה םויב” on “that day”. Our natural understanding would be that the term ”אוהה םויב” refers to the first day of Pesach. Yet, in the Haggadah, we raise the possibility of “םויב אוהה” being on Erev Pesach (םוי דועבמ). It seems unusual that we would think that a Mitzva that the Torah explicitly applies to a particular day might be performed on the day beforexiii . However, if we expand our understanding of “ןושארה םויב”, one can plausibly argue that we would be permitted to tell the story of Pesach on Erev Pesach as well.xiv

While this expansion of ןושארה םויב helps us understand certain Mitzvos, it is more complicated to apply it to the entire gamut of the Mitzvos of the day. For example, the Mitzva of eating Matza cannot be completed early as the Mishna in Psachim explicitly says

Tosfos xviwonders why the Mishna needed to explicitly point out that one should not begin eating until nightfall. He suggests that Matza is unique because it is connected to the eating of the חספ ןברק about

תוררועתה ירבד

3

ךשחתש דע םדא לכאי אל החנמל ךומס םיחספ יברעxv

which the Torah says הזה הלילב רשבה תא ולכאו and the general notion of בוט םוי תפסות would not apply. The Mordechai there in Psachim raises an alternative possibility that the words of the Mishna are not intended to be taken literally and he implies that it may be permitted to eat Matza early. While the Mordechai’s opinion is generally not accepted practically, it could be explained by the expansion of “םויב ןושארה”. xvii

The fundamental idea that underlies this discussion is the importance the Torah places on time. When the Jews were subjugated by Pharaoh, they had no control over their time; they lived at the whims of their Egyptian taskmasters. A key component of the Jewish freedom from Egyptian enslavement is thus the ability to be a master over one’s time. Rather than being bound by the wants of others, we can use our time in a Torah way and for a Heavenly purpose. Perhaps it is no accident that Pesach is a holiday that requires a significant investment of time to prepare for its observance. While taxing on many of us to “turn over” our homes, the Pesach experience reminds us that we have the power to shape and mold our time; we have control of our decisions; we can choose to infuse time with holiness and purpose. May we merit to fulfill the mandates of Pesach to the best of our ability and soon see a time when we will all join together in the Beis Hamikdash.

RABBI ADIR POSY

Rabbi Adir Posy serves as the Associate Rabbi of Beth Jacob Congregation, the Director of the OU West Coast office and the OU’s National Director of Synagogue Initiatives.

1 ג״י:ז״י תומש

2 2.ה םיחספ

3. R’ Yosi offers a third approach based on the word ךא in the Pasuk

4. The sugya there in Psachim analyzes the usage of ןושאר at length

5. Quoted in .לת ןמיס ח”וא רוטב”

6. 4 / 4 םש

7. ב ק”ס םש’

4 תוררועתה ירבד

8. ח הכלה ’ג קרפ הצמו ץמח תוכלה

9. He explains the words of the Rambam to mean that once midday of Erev Pesach arrives, one can no longer perform Bittul Chametz, and one will violate the prohibition of הארי לב once Pesach arrives

10. ןיב ה”ד :ד םיחספ

11. It would be necessary to reconcile this with the Rambam’s words in his introduction תיבשהל הוצמ העבש לכ ץמח אצמי אלו העבש לכ ץמח הארי אלש ד”יב רואש

12. ג”י תומש-’ח

13. We only reject this possibility because of a Pasuk that requires us to tell the story when there is Matza in front of us and the Torah is explicit that those Mitzvos must be performed at night ברעב תוצמ ולכאת

14. Rav Betzalel Zolty in Mishnas Yaavetz offers a different approach based on R’ Chaim Soloveichik. He suggests that the reason we might have assumed that the Mitzva of telling the story of Pesach could occur on Erev Pesach is because of the notion of בוט םוי תפסות which extends the observance of a Yom Tov before nightfall. This would be difficult to reconcile with the opinion of the Rambam in וח הכלה א קרפ רושע תתיבש where the Rambam only mentions the notion regarding fasting on Yom Kippur which the Beis Yosef takes to mean that the Rambam only assumes אתיירואד ןיד regarding fasting on Yom Kippur but does not apply it to other contexts

15. טצ:

16. דע ה”ד

17. The Terumas Hadeshen in ז״לק ןמיס uses the approach of Tosfos to similarly prohibit reciting Kiddush and the rest of the Mitzvos of the Seder before nightfall

5 תוררועתה ירבד

Joshua Gerendash ‘23

Message of Our Survival

Pesach signifies our exodus from Egypt and our newfound freedom; we think of matzah and marror and the 10 plagues; we tell the story of Pesach to our children at the Pesach seder and it is rich in meaning, and of course - in food. But what “big picture” meaningful lesson can we find within Pesach that we can pass on from generation to generation? What is the most important message of our survival story? Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks zt”l, shared a beautiful idea that we would like to share with you. He states that we as Jews have survived and surpassed many ancient world powers, even though we were often thought of as a “weak people.” We were slaves in Egypt and the Egyptian Empire thought of the Jews as “low” and worthy of enslaving. They never fathomed that these would be the same people who would be living thousands of years later and flourishing in the complex modern world.

Rabbi Sacks zt”l goes on to state that the names “Ramses” and “Moses” come from the same root and are similar, yet different. Ramses literally means the “child of the god of sun” and Moses means “the child drawn from the water.” The name Ramses is clearly all powerful, yet the name Moses signifies humility and plainness. As a people, our survival was improbable to those in power of the ancient worlds, including Pharaoh himself. He never imagined that we would be the victors and find freedom at the price of the Egyptians. Moshe’s message in Parshat Bo gives us a deeper understanding as to why and how our people survived and flourished over many generations. When the people were focused on their newfound freedom, Moshe said to them, “You should teach your children in that day.” He reiterates the importance of teaching our children multiple times, because as Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks zt”l states, “Education is the conversation between the generations.”

Our heroes are our teachers, those who learn and those who teach. Our heroes are our parents who take it upon themselves to teach their children their own Torah values and how to ultimately be close

6 תוררועתה ירבד

to Hashem and to one another. This focus on education is our form of immortality, which allows us to live successfully throughout the generations. It is the education and not the monuments of stone that help guide our children and our children’s children. Yes, as a people, we may signify humility and in plain view, we may not always stand out as the “strongest people;” yet, our survival is strong and long lasting from generation to generation. As said, “Engrave your values on the hearts of your children and on theirs,” and this action is what ultimately leads to our survival story, which long surpasses our freedom from slavery.

Pesach helps us remember that true survival of generations is not only about freedom, but rather about what we choose to do with our freedom. May we continue to teach our children the Torah values that will guide us daily for many generations to come.

SAMIRA MILLER & HADASSAH MILLER ‘26

Samira Miller is the Director of Admissions at YULA High School Girls Division and loves being part of the vibrant and warm LA Jewish community.

Hadassah Miller ‘26 is a graduate of Harkham Hillel Academy and is now a Freshman at YULA. She loves being a youth group counselor at Beth Jacob Congregation and is enjoying her time at YULA!

7 תוררועתה ירבד

The Eternal Miracle - ךנבל תדגהו

The holiday of Pesach is one of the most beloved and celebrated holidays of the Jewish calendar. It is a time when we remember and relive the story of our ancestors’ liberation from slavery in םירצמ. One of the central aspects of the Pesach seder is the commandment to tell the story of םירצמ תאיצי to our children, as it says in Shemot 13:8,

“And you shall tell your child on that day, saying, ‘It is because of what the LORD did for me when I came out of Egypt.’”

This commandment of ךנבל תדגהו is more than just a call to recount a story; it is a challenge to learn and to teach, to transmit the entirety of the Jewish experience from one generation to the next. And this transmission is the key, the secret to Jewish continuity and survival.

Our Mesorah teaches that the obligation to tell the story of םירצמ תאיצי applies not only to parents and children, but also to all Jews. The great gadol Rabbi Nosson Gestetner zt”l (1932-2010) explains that the obligation to tell the story of םירצמ תאיצי applies even to individuals who are alone (e.g. no guests, no children), “even if he already knows the story he is still supposed to say it over to himself.” This highlights the sacred significance and inherent importance of the commandment to Jewish identity and continuity, as it is not just a communal obligation, not just a family obligation, but a sacred obligation incumbent on each and every Jew.

The concept of ךנבל תדגהו is not limited to the seder night. Rather, it is an ongoing, lifelong obligation to learn and teach so as to constantly strengthen and preserve Jewish identity. To do this, Pirkei Avot instructs us that we should “acquire for ourselves a teacher” (1:6). The word “acquire” implies effort, care, and value, which are essential for this most essential task. The relationship between teacher and student is a sanctified partnership going back almost 3800 years to Avraham Avinu teaching his son Yitzchak Avinu the Way of Hashem (Vayeira 18:19). It is a hallowed relationship in which both parties learn and grow from each other. The teacher shares

8 תוררועתה ירבד

”םִיָֽרְצִמִּמ יִתאֵצְבּ י ִל ׳ה הָשָׂע הֶז רוּבֲעַבּ רֹמאֵל אוּ הַה םוֹיַּבּ ךְָנִבְל ָתְּדַגִּהְו ” -

her knowledge, experience, and wisdom while the student brings her questions, passion, and devotion. This concept is summed up beautifully in Ta’anit 7a – “And this is what Rabbi Chanina said: I have learned much from my teachers and even more from my friends, but from my students I have learned more than from all of them.” The irreplaceable relationship between student and teacher, in the innumerable forms it takes (parent/child, rabbi/student, teacher/ student, friend/friend, stranger/self, etc.) is the time-proven means to guide us and strengthen us in our learning and teaching. Thus, we are able to grow spiritually, emotionally, and intellectually and ensure the continuity of our Jewish identity.

As Pesach approaches, we can prepare for it by seeking out as many teachers as possible to deepen our experience during the sedarim and during the 8 day chag. We are blessed to have so many resources –rabbis, teachers, haggadahs, divrei torah, online shiurim - to enrich and deepen our experience of retelling the story of our ancestors and re-creating within ourselves the experience of slavery, miracles, and redemption. This is the way of Hashem to learn, teach, and share. This is the way to infuse the love and appreciation of Hashem into our souls and into the souls of family, friends, and community. This is the way to ensure the continuity and continuation of Klal Yisrael.

There are 136 generations, covering over 3200 years, that stretch from Moshe Rabeinu to us this very day. Despite every enemy who has arisen to destroy us (as referenced in the Haggadah in איהו הדמעש) – the Egyptians, the Assyrians, the Babylonians, the Persians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Spanish, the Nazis, the Communists, etc. - we have survived and thrived. We have survived and thrived because we have been faithful, with complete faith, to ךנבל תדגהו. It is this mitzvah which is the foundation to Jewish identity and Jewish survival and continuity. May Hashem strengthen, elevate, and uplift us so that we in this generation can meet the challenge of ךנבל תדגהו and ensure the entirety of the Jewish experience is passed on to another 136 generations and for all eternity.

9 תוררועתה

ירבד

TAMAR SCHEINFELD ‘24

Tamar Scheinfeld ‘24 is a junior at YULA High School Girls Division. She is a member of Model Congress, the YIAC Board, the YULA basketball team, and the co-editor-in-chief of the weekly Paw Print.

10 תוררועתה ירבד

Naftali Bookstein ‘25

The Mitzvah D’Oraita of Maggid

“And you shall tell your son, on that day, saying, ‘It is because of this day that Hashem acted on my behalf when I left Egypt.”

The expression “Talk is cheap” or “You are all talk and no action”, come to mind when one talks too much about something. Yet, on Pesach night we are instructed by Chazal,

חבושמ הז ירה”, the more talk, the better.

Why is speech elevated to the level of a positive commandment on the night of the seder as well as a mitzvah all year long?

HaRav Soloveitchik zt”l speaks directly to the connection between speech and freedom, Hagaddah and cherut. A slave, overtime, would lose his ability for self-expression or speech, becoming a mute being, not all that different from an animal. Yes, animals like humans, experience pain and cry out, but it is only humans that, once the pain recedes, experience suffering. This suffering is the result of humiliation, shame and questioning. Why was I subjected to such injustice, unfairness, and undeserved pain? This experience of suffering is reserved primarily for those who are free or able to recall once being free.

Born slaves are unable to experience such suffering. Like animals, once the actual pain recedes, they return to their mute state. Free men have a past , even as they exist in the present and look forward to the possibility of a better future. Generational slaves have no known past. Their present is controlled by others and they have little to look forward to in the future. They are enslaved physically, emotionally and spiritually.

R’ Soloveitchik zt”l depicts the enslaved Jews in Egypt as voiceless, mute and without hope for a better future. He quotes the holy Zohar

When Moshe came to speak to the enslaved Jews in Egypt, their לוק

11 תוררועתה ירבד

ח,גי תומש ”םִיָרְצִמִּמ יִתאֵצְ בּ יִל ’ה הָשָׂע הֶז רוּבֲעַבּ רֹמאֵל אוּהַה םוֹיּבּ ךְָנִבְל תְּדַ גִּהְו ”

“,םירצמ תאיציב רפסל הברמה לכ

“לוק אתא השמ אתא יכ”

or voice returned to them. How so?

Moshe shared with the Jews that they were the descendants of free men, that their forefathers and mothers were chosen by the one true G-d, who promised them that their descendants will one day be kings and priests and a holy nation, residing in a promised land and governed by a perfect law. Upon hearing this, the slaves began to experience suffering. They regained their voice and,” ..וקעציו..”, they cried out with deep anguish and suffering to their Father in heaven.

״לוק אתא השמ אתא יכ” Once the Jewish people could experience suffering, they were no longer enslaved. They were able to recognize the injustice done to them by Pharaoh and the Egyptians. Even as they misplaced their anger and frustration against Moshe and Aharon, the fact that they could express their suffering, was the beginning of their redemption.

Lehaggid is the highest form of speech. Our ability to recall and retell our history, to experience the past , the present and envision a better future is the definition of Geula – redemption and true freedom.

The message of the Pesach story is that speech is freedom Cherut. It is a lesson we have taught the world and why the Torah elevates the mitzvah of Magid, making it the overarching theme of both, Chag HaPesach and the Seder night.

RABBI PINCHOS HECHT

Rabbi Pinchos Hecht is a Judaic Studies teacher at the YULA High School Girls Division. He is a career mechanech with over 35 years as a rebbe and school administrator. He holds a Masters in Education and a second Masters in Administration.

12 תוררועתה ירבד

״חבושמ הז ירה ,םירצמ תאיציב רפסל הברמה לכ” - the more talk, the better!

In the beginning of Parshat “Bo,” Hashem tells Moshe, “… that you may relate in the ears of your son and your son’s son, that I made a mockery of Egypt and My signs that I placed among them– that you may know I am Hashem.” The Oznaim L’Torah explains that the word “you” in this verse is written in the plural form, referring both to whoever tells the story in the future and to whoever listens to it. The Torah uses the plural form to teach us that no matter how many times people might tell the story, they cannot help but be moved and inspired by the story they tell. The Haggadah tells us, “…even if we were all wise and knew the Torah, it would still be a mitzvah for us to tell the story – and anyone who enlarges upon the story of the Exodus, is praiseworthy!”

Rav Yisrael Yaakov Lubchansky zt”l, writes that “anyone who enlarges on the story of the Exodus” does not necessarily refer to one that delves into the intricacies or deeper meanings of the details of the Exodus. Rather, even if one repeats the same facts time and time again, he is considered to be “anyone who enlarges on the story of the Exodus,” so he, too, is praiseworthy. Constant review, even when it does not involve any new or deeper insights, has a profound effect on the mind of the person telling the story.

Rav Meir Simcha Ha’Kohen of Dvinsk, the Ohr Sameach quotes a passage from the Talmud (Pesachim 112b), where the sound for goading an ox is “Hen! Hen!” and for a camel is “Da! Da!” At first glance, this information seems to be so trivial and insignificant, that one wonders why the Talmud felt it necessary that it be recorded? Rav Meir Simcha explains, the Talmud is actually alluding to a very important principle: an animal hears the word or command the first time and is not prodded into action, until it hears the word or command again and again “Hen! Hen!” or “Da! Da!”-- so we, too, must hear things again and again. The more a fact or idea is repeated, the greater the impression it makes. The constant repetition of an appropriate teaching or idea of our sages is often the most effective way to foster change in the innermost levels of the human psyche–

13 תוררועתה ירבד ״… חבושמ הז ירה הברמה לכו ...״

RABBI JOSEPH SCHREIBER

Rabbi Joseph Schreiber is Principal of YULA High School Boys Division and 9th Grade Rebbe in the Baum Family AGT. He also teaches Nach at YULA High School Girls Division.

14 תוררועתה ירבד

and is indeed praiseworthy!

Kayla Schachter ‘26

וּיָהֶׁש ןוֹפְרַט יִּבַרְו אָביִקֲע יִּבַרְו הָיְרַזֲע־ןֶּב רָזָעְלֶא יִּבַרְו ַעֻׁשוֹהְי

It happened once [on Pesach] that Rabbi Eliezer, Rabbi Yehoshua, Rabbi Elazar ben Azariah, Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Tarfon were reclining in Bnei Brak and were telling the story of the exodus from Egypt that whole night, until their students came and said to them, “The time of [reciting] the morning Shema has arrived.”

One of the more well-known passages of the Haggadah is the story of the five sages in B’nei Brak reciting the Pesach story throughout the night until their students told them that it was time to recite the morning Shema prayer. This passage immediately follows the passage of Avadiim Ha’Yenu which summarizes the essence of what we celebrate on Pesach – we were slaves in Egypt, Hashem saved us, and if not for the redemption, we would still be slaves. So, it is understandable that the Haggadah begins with Avadiim Ha’Yenu. But, why then does the Haggadah immediately interrupt the storyline of Pesach and cut to a seemingly tangential story of five rabbis sitting around a table discussing the Pesach story? Further, why does the Haggadah choose to end the story with specifically mentioning the Shema prayer instead of simply saying “until morning”?

The story of the sages teaches us the lesson that after darkness must come light. This concept symbolizes the entire history and future of the Jewish nation, from slavery in Egypt until the coming of Mashiach. Jewish history is riddled with darkness: slavery in Egypt; the destruction of the Temples; the Holocaust; and the current rise in Antisemitism worldwide and terrorist attacks in Israel. The sages stayed up through the darkness of night, representing the darkness that the Jewish people have faced time and time again. However, the sages’ “darkness” was cut by the light of daybreak, representing the Geulah, salvation, from Hashem. Just as their “darkness” turned to

15 תוררועתה

־ןֶּב רָזָעְלֶא יִּבַרְו ַעֻׁשוֹהְי יִּבַרְו רֶזֶעיִלֱא יִּבַרְּב הֶׂשֲעַמ ןוֹפְרַט יִּבַרְו אָביִקֲע יִּבַרְו הָיְרַזֲע

ירבד

םֶהיֵדיִמְלַת

םִיַרְצִמ תַאיִציִּב םיִרְּפַסְמ וּיָהְו קַרְב־יֵנְבִּב ןיִּבֻסְמ תיִרֲחַׁש לֶׁש עַמְׁש תַאיִרְק ןַמְז ַעיִּגִה וּניֵתוֹבַּר םֶהָל וּרְמָאְו

יִּבַרְו רֶזֶעיִלֱא יִּבַרְּב הֶׂשֲעַמ

וּאָּבֶׁש דַע ,הָלְיַּלַה וֹתוֹא־לָּכ

light, so too does the darkness of the Jewish people always turn to light with Hashem’s salvation. With this in mind, we can see why the passage of the five sages fits perfectly right after Avadiim Ha’Yenu. Avadiim Ha’Yenu tells the Pesach story of darkness to light, and the story of the five sages further illustrates this concept.

This also explains why the passage specifically mentions Shema. Shema is a Jew’s admission of belief in Hashem and our acceptance of Hashem as our G-d. It is the ultimate statement of Jewish identity, belief and hope. As long as we, as a nation, have Hashem and believe in Hashem, there will always be the light of a Geulah, redemption, at the end of our darkness.

Additionally, it is no coincidence that this story occurred in B’nei Brak at the home of Rabbi Akiva, the ultimate symbol of Jewish hope. The Gemara, in Tractate Makkot 24b, tells the story of when Rabbi Akiva was with Rabban Gamliel, Rabbi Elazar ben Azariah and Rabbi Yehoshua in Jerusalem as they watched a fox running around the Temple Mount in the place of the Kodesh Ha’Kodishiim, the Holy of Holies. At this sight, the other Rabbis began to cry while Rabbi Akiva began to laugh. He explained that just as Uriah’s prophecy of Jerusalem being destroyed with foxes running throughout was fulfilled, so too, Zachariah’s prophecy of Jerusalem once again being alive with Jews must be fulfilled. Rabbi Akiva understood that darkness must always be followed by light.

May this year be the year we receive the ultimate “light” with the bringing of Mashiach and our returning to Jerusalem

DANIEL SCHREIBER ‘11

Doni Schreiber ’11, is a Senior Associate at Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough LLP, in the firm’s Real Estate group. He, along with his wife Sari and daughter Emilia, lives in Boca Raton, FL. He studied at Yeshivat Kerem B’Yavneh, Yeshiva University, and USC Gould School of Law.

16 תוררועתה ירבד

What a Difference a Letter Makes

One of the most popular passages in the Hagadah is the hymn איהו הדמעש. In that song of praise, for which we raise the “cup of salvation”, we extol God who has redeemed us in not just one instance – תאיצי םירצמ - but has saved us from genocidal threats in every generation. This well-known paean is prefaced by another paragraph of praise –לארשיל ותחטבה רמוש ךורב – blessing God Who keeps His promises for His people.

In it, we reference the “Covenant between the pieces’’, which God made with Avraham (Beresheet 15:13-16). We read the first two verses of that covenant: “Know that your progeny will be strangers in a foreign land and they will be enslaved and oppressed for four hundred years. And I will judge the nation that enslaves them and after that they will leave with great wealth.”

There is, however, one phrase in the middle of the first paragraph which seems to contradict the thrust of הדמעש איהו. We declare וניבא

“The Holy One, Who is blessed, calculated the end in order to fulfill that which He had promised to Avraham Avinu…” That opening word –בשיח (calculated) in the past tense, indicates that the fulfillment of this covenant was a one-time experience, a promise of a single salvation and that God calculated the most propitious time to fulfill it. Yet, in the moving hymn that follows it, we do an about face and declare that this covenant was not about protection from a single tormentor, but from tyrant after tyrant, maniac after maniac, each of whom arose to wipe us from the face of the earth (to borrow a phrase from one of the more recent villainous monsters). So – which is it? Is the covenant a one-time deal, good for one redemption? Or is it an eternal promise of God’s protection in every generation?

As we are all aware, the text of the core of the Hagadah predates the printing press by well over a thousand years and nearly every later addition (such as “Dayyenu”, the Midrash of 250 plagues etc.) all became part of the Hagadah during the era of manuscripts

17 תוררועתה ירבד

םהרבאל רמאש המכ תושעל ץקה תא בשיח אוה ךורב שודקהש

(handwritten documents). As such, we have scores of different Haggadot, many of which reflect slight (or not-so-slight) variations from the text that we may be familiar with. One small example is the “simple” son, the םת of our תודגה, who is identified as a “שפט ןב” (stupid son) in the ימלשורי דומלת and in the אתליכמ.

Our opening paragraph is similarly enriched by a variant reading which could not be any smaller – a difference of one letter – yet changes everything.

In Rambam’s text of the Haggadah (and in that of numerous other Rishonim) the paragraph cited above reads בשחמ אוה ךורב שודקהש ץקה תא - to wit, God calculates the end. In other words, instead of praising God for a Divine calculation made over three thousand years ago to extricate His people from the clutches of Egyptian servitude, we thank God Who continues to consider and calculate the most appropriate method and time for saving us from our current travails. This, in turn, becomes a mode of commentary on the “Covenant Between The Pieces”. Instead of reading that promise as a prophecy

18 תוררועתה ירבד

Cloe Tewner ‘23

of one generation’s troubles and God’s commitment to save them, it becomes a meta-historic statement, a blue-print of the pattern of Jewish history. There will be further exiles, Avraham learns, and dastardly as the oppressors may be, vile as the intentions may proveGod will ultimately judge them and bring His people home, as we have been privileged to see in our own generation of redemption. Indeed, the two paragraphs of רמוש ךורב and הדמעש איהו now work seamlessly, the one referencing the promise in foresight and the other, with the pure vision of hindsight, praising God Who has kept His word to Avraham and saved his descendants, time and time again, from the despotic hands of tyranny.

RAV YITZCHAK ETSHALOM

Rav Yitzchak Etshalom has been a Rebbe at YULA for 26 years. An internationally renowned Tanakh teacher, he chairs the YULA Tanakh Masters Program.

Class Project

19 תוררועתה ירבד

Pesach, Matzah and Maror

As the whole family sits at the seder table on Pesach night, every child is excited, finally able to stay up way past bedtime. At the seder, the three most famous and important things are the mitzvot of Korban Pesach, matzah and maror. Obviously today, we cannot fulfill the korban pesach and, instead, have a bone as a zachor, commemoration. However, other than having a bone on our seder plate, eating the matzah and eating the maror, there is an extremely important verse we are required to say in order to fulfill the mitzvah obligation. “Pesach, matzah, Umaror.” The source for this obligation is the following mishna,

Rabban Gamliel would say: Anyone who did not say these three matters on Passover has not fulfilled his obligation: The Paschal lamb (pesach), matza, and bitter herbs (maror).

In this Mishna, Rabban Gamliel explicitly tells us that we must say these three things in order to fulfill our obligation. Rav Ovadia

M’Bartenura notes a seemingly obvious point, namely that Rabban Gamliel does not explain what obligation we are actually fulfilling when we recite these words. What is the obligation?

There are two possibilities of what the obligation might be. First, we might be fulfilling the mitzvot of korban pesach, matzah and maror themselves. Reciting words that describe the mitzvot give these mitzvot their meaning. We cannot simply look at the pesach or eat the matzah or maror; we need to describe why we are doing these acts. Rabban Gamliel is teaching us that just acting is not enough. We need to speak them out. The reason the main way people learn is bechavruta is because when we speak things out to our friend, it not only helps them but it helps us understand better. In his targum on Chumash, Onkelus adds an important layer to this idea. On the pasuk

20 תוררועתה ירבד

וּלֵּאְו ,וֹתָבוֹח יֵדְי אָצָי אֹל ,חַסֶפְבּ וּלֵּא םיִרָבְד הָשֹׁלְשׁ רַמָא אֹלֶּשׁ לָכּ ,רֵמוֹא הָיָה לֵאיִלְמַגּ ןָבַּר רוֹרָמוּ ,הָצַּמ ,חַסֶפּ ,ןֵה

הָיַח שֶפֶנְל םָדָאָה יִהְיַו - the human became a living being he

as אָלְלַמְמ ַחורְל םָדָאְב הָוַהְו - the human became a speaking being. Onkelus’

translates it

translation teaches us that our speech is what makes us alive. It is what distinguishes us from animals, and it is what makes us distinctly human. Now, at the seder table, when we are fulfilling the mitzvot of pesach matzah and maror, we cannot forget our fundamental essence as literate beings and must physically speak out the mitzvot in addition to doing the act (having a shank bone and eating the matzah and maror).

The second possible way to understand Rabban Gamliel’s statement is to explain that he is referring to the the mitzvah of the Haggadah. Meaning, if one does not say pesach, matzah and maror), s/he would not be yotze the mitzvah of reading the Haggadah. While we acknowledge the paramount importance of articulating our values, Rabban Gamliel teaches us that this on its own is not enough. We can’t just tell over the Pesach story, we need to act.

Therefore, Rabban Gamliel says if one just says the words of the Haggadah but never translates that into the practical mitzvot that we do today (namely, the mitzvot of pesach, matzah and maror), then the recitation of the story is incomplete. When we say “pesach, matzah u’maror” we are bringing the story into the realm of action by fulfilling these three principle mitzvot.

Each of these two approaches to understanding Rabban Gamliel’s statement teach us a valuable lesson. On one hand, we see the importance of not simply living our lives based on words but translating the thoughts and ideas in our head into concrete action. The main obligation on Pesach is remembering Yetzias Mitzrayim. It is why we have the seder. But Rabban Gamliel is teaching us that it is not enough to just look back at the past; we must bring the story of yetziat mitzrayim to the present, doing so through action. In our own practical experience, a great example could be when we tell our friends the importance of supporting Israel or the significance of learning Torah. Our words are not worth much unless we actually go out and act, proactively advocating for Israel or setting aside time for limud Torah. Rabban Gamliel, by teaching us this lesson, is showing us how words supported by actions can be an incredible pathway of expressing our values. But in order to be successful in doing so, we

21 תוררועתה ירבד

need both speech and the connectivity of action.

On the other hand, the first approach teaches us an equally important lesson. Whenever we learn or do something, even outside of the seder, it is so important that we express and articulate ourselves. Half the battle when trying to express an idea is actually getting your thoughts out there. One cannot just look at the zeroah, shankbone, or eat the matzah and maror and be done. Just thinking about redemption from Egypt is not enough; we have to also act. We proclaim pesach, matzah and maror as a concrete action - speaking and articulating the ideas to fully fulfill the obligation.

When examining the two understandings of Rabban Gamliel’s words both in the realm of speech and the realm of action, we can see why he wrote his halacha in a potentially ambiguous way. Perhaps, it was Rabban Gamliel’s intention that we prioritize both of the aspects (speech and action) when we experience the seder on each night. He therefore wrote it in such a way that it would be able to be interpreted as a life lesson. The power of speech and the power of action are both vital, and it is when they unite together, that our mitzvot reach their fullest potential.

YITZY POSY ‘26

Yitzy Posy ‘26 is a ninth grader at Yula High School; Boys Division. He grew up in LA and graduated from Hillel in 2022. Yitzy loves hanging with friends, learning, and playing basketball.

22 תוררועתה ירבד

Seeing Yourself in the Past

The obligation of םירצממ אצי וליאכ ומצע תא תוארל םדא בייח that “every person is required to see himself as if he left Egypt”, raises a number of questions both based on the words themselves, as well as the placement of the commandment in the Haggadah. What does it even mean to “see yourself leaving Egypt”? Why is the commandment, which is widely regarded as the most difficult component of the Seder night, such a critical aspect of retelling the Exodus from Egypt? The Abarbanel, in his commentary on the Haggadah, provides a wonderful answer to the first question. First of all, the Abarbanel has the same wording of the phrase as the Rambam does,

…..תוארהל םדא בייח (as opposed to (תוארל, changing the entire essence of the obligation from seeing oneself as if one left Egypt, to showing oneself as if he is leaving Egypt. The Abarbanel points to the people currently living in exile, whether that be outside of Eretz Yisrael or even within the Land awaiting the ultimate redemption and return of the Beit Hamikdash and points out different aspects of suffering that we all endure, drawing a comparison to the suffering which our ancestors experienced in Egypt. He says that our entire task on the Seder night is to see our own personal sufferings as an echo of the suffering our forefathers faced and to strengthen our closeness to God by feeling the redemption of Egypt in the context of our individual sufferings- a proverbial look in the mirror.

While this explanation offers an answer as to what the actual obligation is, we are left asking ourselves why the phrase appears right before we begin saying Hallel. The question is deepened by the phrase used in the Haggada to introduce the Hallel: ונחנא ךכיפל תודוהל םיבייח... therefore we are obligated to give thanks; why is the word “therefore” immediately used following the commandment to see yourself leaving Egypt. An additional problem with this text is Halakhic: Why is there no Bracha before the recitation of this Hallel as there is before every other Hallel? Rav Hai Gaon answers this last question, saying that this Hallel differs as our reading of it is meant

23 תוררועתה

ירבד

to be spontaneous and unplanned as if we are brimming with thanks for God and simply cannot contain ourselves from spilling out the gratitude for God. For this reason, there is no time to stop and say a Bracha, as that would formalize the Hallel and turn it from a הריש- a song to האירק– a recitation.

When combining the answers of the Abarbanel regarding the commandment itself, coupled with Rav Hai Gaon’s understanding of the Hallel directly following it, the whole picture becomes clearer. This commandment is not a passive “seeing yourself” leaving Egypt as the more common wording indicates, but rather an active one of showing yourself leaving Egypt on that day; it’s about taking the sufferings in your life and the sufferings our forefathers experienced in Egypt, and feeling God take us out of those struggles as he did our forefathers. This lively, active experience of leaving our own personal Egypt (as it were), compels us to shout praise for God immediately, unable to contain our gratitude. For this reason, we do not even stop to say a formal blessing before the Hallel, as we are so overwhelmed at God’s greatness, we must immediately burst out in praise. By personalizing the Exodus and turning it into our own, the entire seder night takes on a much different essence: the combination of God’s intervention in Egypt with His intervention every day in our own lives.

AVRAHAM ETSHALOM ‘21

Avi Etshalom ‘21 has just completed two years of study at Yeshivat Har Etzion (“The Gush”) and is on his way to study at Yeshiva University.

24 תוררועתה ירבד

Charoset: We Are What We Eat

As Pesach approaches, we eagerly anticipate the iconic Seder treat of Charoset. An unusual condiment, we love it and enjoy trying new recipes every year. This year we asked ChatGPT for recipe suggestions and were not disappointed. In fact, in just one search they offered us four different ways to prepare Charoset! The variety of recipes and customs made us wonder, how important are the ingredients of Charoset and, more importantly, what is the relevance of each one to the Seder?

There are varying opinions on the importance of Charoset. On the one hand the Chachamim maintain that eating Charoset is not even a Mitzvah. It is simply part of the Seder to blunt the bitter taste of the Maror. On the opposite extreme there is the somewhat surprising opinion of Rav Elazar Ben Tzadok in Masechet Pesachim, who argues that Charoset is not simply a condiment for the Maror, but is actually a Mitzvah itself!

The Talmud Bavli offers two reasons for the Mitzvah of eating Charoset. The first explanation is the classic understanding that the Charoset’s consistency is a reminder of the mortar used by our ancestors in Egypt as slaves. The second explanation offered by the Gemara, as to why eating Charoset is a Mitzvah, has to do with the ingredients inside of it. The focus is specifically on the Tapuchim, which is translated as apples in modern Hebrew or citrus fruits in the classic understanding. Rashi explains the significance of Tapuchim as related to the fact that the Jewish women would give birth in Tapuach orchards outside of the city so the Egyptians would not discover a Jewish baby had been born.

The Gemara explains that ideally one should add spices into the Charoset, as whole dried spices are reminiscent of straw, which we used in Mitzrayim.

Tosfot, quoting the Talmud Yerushalmi, says Charoset should be red in color as a reminder of the various symbols of blood in Egypt. It is this opinion that inspires the many recipes that include red wine.

25 תוררועתה ירבד

Tosfot quotes the Teshuvot HaGeonim that teaches that Charoset should incorporate ingredients that are used to symbolize the Jewish people in Shir Hashirim, such as almonds. Finally, the Ramabm includes that we should add in raisins and dates.

Regardless of the recipe used, Charoset teaches us one of the great pedagogical lessons of the Seder as a whole. ALL of the food items utilized are vehicles to share our stories and traditions. Even the most seemingly insignificant aspects of the Seder symbolize important aspects of

Yetziat Mitzrayim and are instrumental in bringing the narrative to life around our Seder table each year.

Chag Sameach!

RABBI ARYEH KAPLAN & SHALVA KAPLAN ‘23

Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan is a proud YULA parent. He is the Executive Director of the OU’s Jewish Learning Initiative on Campus and a 10th grade Talmud Rebbe at YULA Girls.

Shalva Kaplan ‘23 is a senior at YULA High School Girls Division. She enjoys being captain of the YULA Model Congress team and co-president of YIAC. Shalva is excited to attend MMY in Israel next year.

26 תוררועתה ירבד

The Women Who Frame Sefirat Ha’Omer

While the period of Sefirat HaOmer is a time of mourning for the Jewish people, as we commemorate the deaths of the students of Rabbi Akiva, it is also a time of great anticipation and excitement as we approach the holiday of Shavuot, Z’man Matan Torahteinu. Marking each passing day until Shavuot, the counting of the Omer is not just a numerical countdown, it is also a spiritual journey of selfimprovement and growth.

To help frame this journey, the Jewish people envelope the counting of the Omer surrounded by narratives of two different women: the Shulamit maiden- the Ra’aya of Shir HaShirim which we read on Pesach, and Rut of Megillat Rut which we read at the end of the sefira period, on Shavuot.

Both megillot fuse the spiritual with the romantic. Shir HaShirim, as viewed through the Midrashic allegorical prism, depicts the reciprocal love of God and Israel reflected in the constant waxing and waning of the King’s courtship of his Shulamit maiden, as well as other challenges and obstacles placed in the path of their union. This creates a sense of unattainability and reinforces the idea that their love is not without its challenges.

At times, the Shulamit maiden expresses her love and admiration for the King, describing him as “radiant and ruddy” (5:10) and extolling his virtues. However, there are also moments when she feels neglected or abandoned by him, “I opened [the door] for my beloved, but my beloved was gone. My heart sank at his departure” (5:6).

Similarly, the King is depicted as deeply in love with the Shulamit maiden, expressing his love for her and declaring her beauty. However, there are also moments when he seems distant or unattainable, such as when she attempts to find him. “Who is this that appears like the dawn…. bright as the sun, majestic as the stars in procession? I went down to the grove of nut trees to look at the new growth in the valley… Before I realized it, my desire set me among the royal chariots of my people.” (6:10-12) Although the maiden is

27 תוררועתה ירבד

searching for the King, it seems he is surrounded by his people and it is difficult for her to reach him.

These fluctuations in the relationship create a sense of tension and inconsistency. While the megillah emphasizes the joy, passion, and intense nature of their love, it simultaneously highlights the contrasting feelings of separation, longing, and vulnerability. This story serves as a reminder that even when we feel distant from HaShem, He is always there for us, awaiting our return.

The story of Rut may similarly be viewed through the prisms of romance and allegory. Rut - like the Shulamit maiden in her pursuit of love - must overcome many obstacles in her desire to achieve union with Judaism, notably bereavement, poverty, and estrangement from homeland, family, and religion. Rut declares her unwavering loyalty to Naomi and then works hard to provide for her mother in law by gleaning in the fields to gather grain for them to eat. She even goes to Boaz, a wealthy landowner, to ask for his protection and support.

Rut’s commitment to Naomi is also expressed in her famous declaration: “Where you go I will go, and where you stay I will stay. Your people will be my people and your God my God. Where you die I will die, and there I will be buried. May HaShem deal with me, be it ever so severely, if even death separates you and me.” (1:16-17) This statement shows Rut’s deep commitment to Naomi, to the extent of adopting Naomi’s people and God as her own. Her commitment is unwavering, even in the face of adversity and uncertainty. It is a powerful testament to the strength of their relationship and to the values of loyalty and devotion.

The romance prism of Megillat Rut is also expressed in the determined way that Boaz woos Rut and in his persistence to keep her close: instructing her to glean only in his fields and fraternize only with his female employees (2:8), instructing his lads to help her in every way and never to obstruct or pester her (2:9, 16), spreading his robe over her as an indication of his wish to make her his wife (3:8-9), and in the way he contrives to displace the go’el in order to become her redeemer once he learns that Ruth is a relative of Naomi’s. Boaz

28 תוררועתה ירבד

recognizes the responsibility that comes with being a kinsmanredeemer and offers to marry Ruth in order to preserve Naomi’s family line and provide for her and Ruth. He also takes steps to ensure that Ruth is legally protected and cared for, going through the proper channels to make sure that their marriage is recognized and that their rights are protected.

Megillat Rut presents itself as a complement to Shir HaShirim by portraying an ideal love that is based upon responsibility and faithfulness in contrast to Shir HaShirim’s depiction of a passionate and hopeful love that is not always ideal and consistent.

The relationship between Pesach to Shavuot is parallel to the relationship of the megillot to each other. Whereas Pesach celebrates the promise of liberation and HaShem’s passionate relationship with His chosen nation, Shavuot celebrates Matan Torah, the giving of the mitzvot reflecting the commitment which grounds that aforementioned relationship. Pesach and Shavuot respectively reflect passion and responsibility in the service of HaShem. Interestingly, the Torah links the two chagim by commanding us to count the interim days without a date even given for the latter. Alluded to by its name, Shavuot (weeks) is simply described as seven weeks after Pesach. Inasmuch as these chagim need each other; we must fuse commitment and dedication on the one hand with a passionate and uncompromising vision of our ideal and goal on the other.

The Rambam in Moreh Nevuchim describes the necessity of both of these components in his discussion of human perfection. He explains that we need both ahava and yirah to achieve this ideal as we strive to grow in our relationship with HaShem. Love is the result of truth taught in the law including true knowledge of HaShem and awe of His existence, while fear is produced from halachic practices prescribed in the law.

Shir HaShirim epitomizes that passion without commitment lacks consistency, yet, commitment without passion lacks meaning. The connection between the beloved (HaShem) and His Ra’aya (the Jewish People) in Shir HaShirim is crucial, but the problem is that the

29 תוררועתה ירבד

inconsistent passion depicted sometimes led to missed opportunities. It is the faithful committed relationship between Boaz and Rut which produces the Davidic dynasty which ultimately leads to our spiritual potential. Let us internalize the messages of both of these narratives in an effort to recognize our personal and national opportunities with a renewed sense of passion and commitment.

MRS. RACHELI LUFTGLASS & SALI LUFTGLASS YG 25’

Mrs. Racheli Luftglass is the Judaic Studies Principal of YULA High School; Girls Division and a proud YULA parent.

SaLi Luftglass ‘25 is a sophomore at YULA High School; Girls Division. She is proud to be a part of STUCO, YULA L’eila, captain of JV Volleyball, a member of Model Congress, Track and Field, and a frequent contributor to the weekly Paw Print. When she’s not busy with school, you can find her baking for SaLi’s Sweets.

30 תוררועתה ירבד

31 תוררועתה ירבד

Chana Horowitz ‘23

Ariel Naim ‘24

32 תוררועתה ירבד

33 תוררועתה ירבד Young Israel of Century City | 9317 W Pico Save the Date! Wednesday May 10th, 7pm

34 תוררועתה ירבד Young Israel of Century City | 9317 W Pico Save the Date! Thursday May 11th, 7pm

35 תוררועתה ירבד

36 תוררועתה ירבד

Candle Lighting for Yom Tov

TIMES LISTED ARE FOR LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA

Wednesday, April 5 ......... Candle Lighting 6:58pm

*Eruv Tavshilin

Thursday, April 6 .............. Candle Lighting after 8:02pm

Friday, April 7 .................... Candle Lighting 7:00pm

Saturday, April 8 ............... Havdalah 8:04pm

Tuesday, April 11 .............. Candle Lighting 7:03pm

Wednesday, April 12 ....... Candle Lighting after 8:07pm

Saturday, April 23 ............ Havdalah 8:08pm

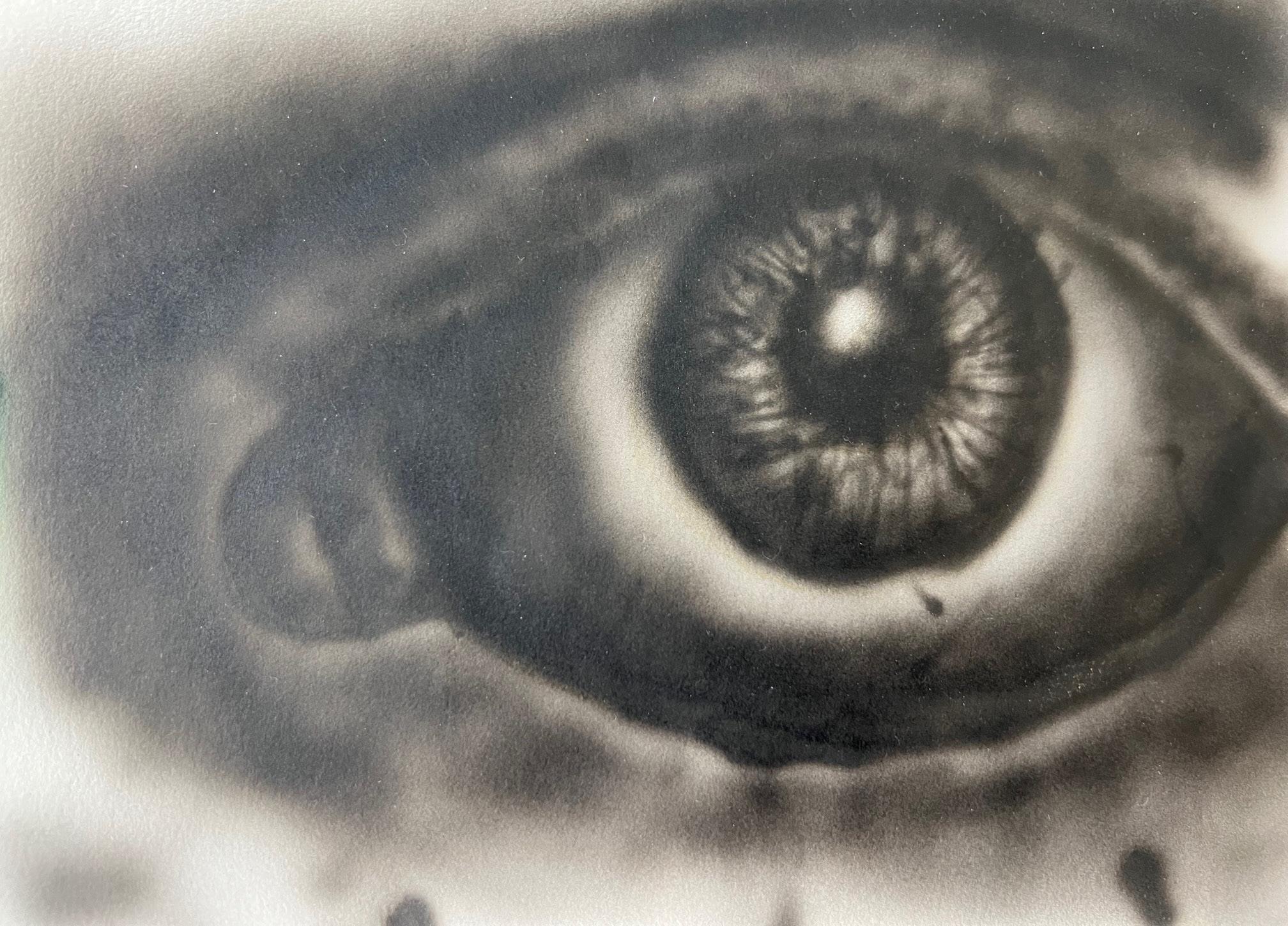

Cover Art: Shira Cohn ‘22

The artwork in this edition was provided by Ms. Holmes’ and Ms. Utratat’s Fine Art classes.