https://issuu.com/yuxu-rae/docs/g1.5._ex5

Designing for Well-being: The Green Buildings in Modern Design Student 1: Yu Xu A1834380 Student 2: Yiding Yan A1841855

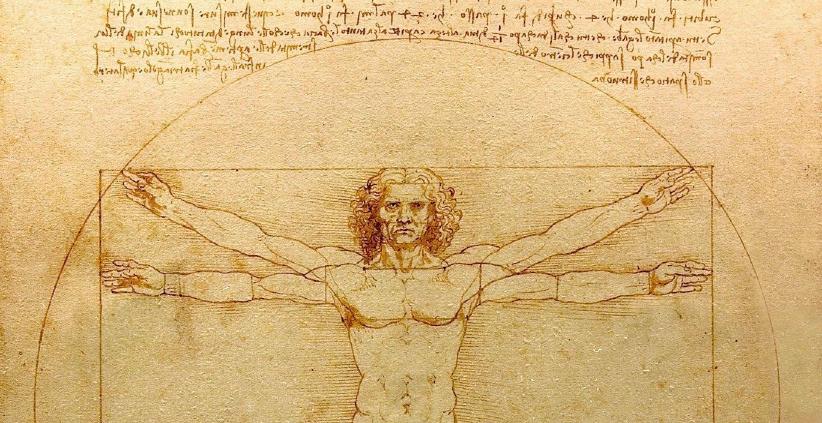

Are we Human?

Notes on an archaeology of design

"Design always presents itself as serving the human but its real ambition is to redesign the human. The history of design is therefore a history of evolving conceptions of the human. To talk about design is to talk about the state of our species."

———— Colomina and Wigley Are we Human?

01 07 02 08 03 09 04 10 05 06 Summary 01 07-10 15-16 17-18 19 02 11-12 03-04 13 14 05-06 Introduction Literature Review Theoretical Framework Design for Well-being Theoretical Sources support Discussion Conclusion Endnotes Bibliography Aknowledgement Contents 11

Summary

Modern architecture has begun to seek sustainable solutions to promote well-being, influenced by contemporary design concepts and environmental issues. Green building has become an important practice, and the design of architectural spaces significantly affects public health and individual well-being. The ability of green buildings to sustainably realise increased well-being has become a topic of debate. We argue that green building can enhance well-being through natural elements and that active engagement can amplify the well-being benefits of natural elements. We conclude that green buildings are designed for humanistic and sustainable concepts and can enhance the wellbeing of residents.

(97 words)

01

Introduction

The relationship between the living environment and well-being has existed since the Paleolithic era, and the interaction between humans and buildings has changed each other.1

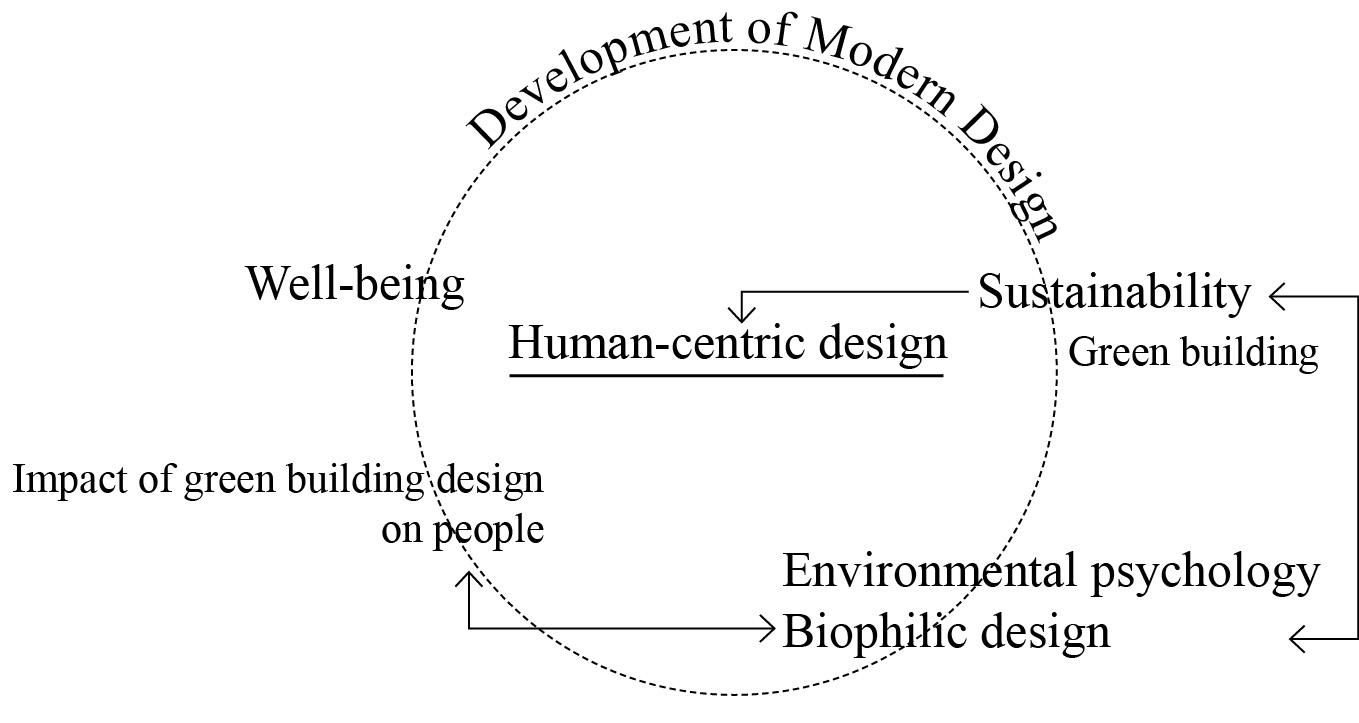

Rapid industrialisation and urbanisation in the 20th century hurt human living and working conditions, and the concept of modern design emerged as a response to the problems of the age.2 Modern design emphasises function over form, aiming to improve the quality of life for all people by creating good designs that can be mass-produced.3 Buildings are the main spaces within cities that house the production and living of their inhabitants. Statistically, human beings spend 85-90% of their lives in buildings; therefore, the building environment directly impacts the well-being of all human beings.4 Against this backdrop, the emergence of green architecture as a synonym for sustainability in modern architecture is a natural progression of the modern design philosophy. (Fig 1)In the book Are We Human, co-authored by architectural historians Beatriz Colomina and Mark

Wigley, the authors mention that modern design promotes a human-centred approach, a natural way for humans to protect humans, but that modern architecture is reshaping human well-being as it protects humans.5 Whether or not green architecture, as an emerging tool, can sustainably achieve improved well-being has been debated.

This essay presents two arguments on this topic. Firstly, green buildings invite natural elements into the living space, which improves the comfort and well-being of the inhabitants; secondly, active participation in the design and renovation of green buildings can improve personal well-being, thus contributing to the improvement of the design of green buildings and the realisation of sustainable design. This essay concludes that green buildings are designed to promote the concepts of humanism and sustainability and can improve the well-being of residents. (287 words)

(Source: PxP Design Workshop, 2023)

02

Fig 1. Sustainable modern architecture

Literature Review

Since the emergence of biophilia hypothesis, much literature has begun to investigate the link between the environment and the psyche. The American environmental psychologists Rachel Kaplan and Stephen Kaplan summarised the results of their investigations in 1989. They pioneered the Attention Restoration Theory (ART), which suggests that human contact with natural elements can reduce stress and evoke a stronger sense of satisfaction. In the workspace, natural elements can also relieve the mental fatigue of office workers and enhance their cognitive function.6 This conclusion laid the groundwork for research into the impact of natural elements on well-being and design principles in green buildings.

After Kaplan’s developed the theory of ART, Terry Hartig et al. demonstrated the positive psychological effects of being in natural environments in 1991.7(Fig 2) Subsequently, several studies began to demonstrate that different natural elements (e.g., light, plants, water) can positively affect different aspects of well-being in different kinds of spaces.

For example, in 1994, Roger Ulrich demonstrated that patients’ access to natural views through windows aided physical recovery in

03

Fig 2. Part of the Kaplan's ART experiments scenes in 1991

(Source: Hartig, Terry, Marlis Mang, and Gary W. Evans.)

hospitals.8 At the same time, the development of modern design concepts has also influenced the design of green buildings. In 1993, Douglas Schuler and Aki Namioka systematically sum-

marised the principles and practices of participatory design, emphasising the importance of user-initiated design.9 In 2021, Danlei Zhang and Tu Yong expanded the integrated theoretical framework based on the well-being model and environmental psychology, expanding the integrated theoretical framework. Research has shown that physical green features, have a more significant impact on residents. These features can help improve well-being and happiness and motivate residents to participate actively. 10 However, some research studies have also suggested the opposite. Andrew Thatcher and Karen Milner’s experiments showed that green buildings did not significantly improve the psychological well-being of employees, thus suggesting that designers should focus on specific design features.11 Richard M. Ryan et al.’s (2010) study suggests that simulated or manmade natural elements within a building may not provide the same psychological benefits as real natural environments.12

(332 words)

04

Theoretical framework

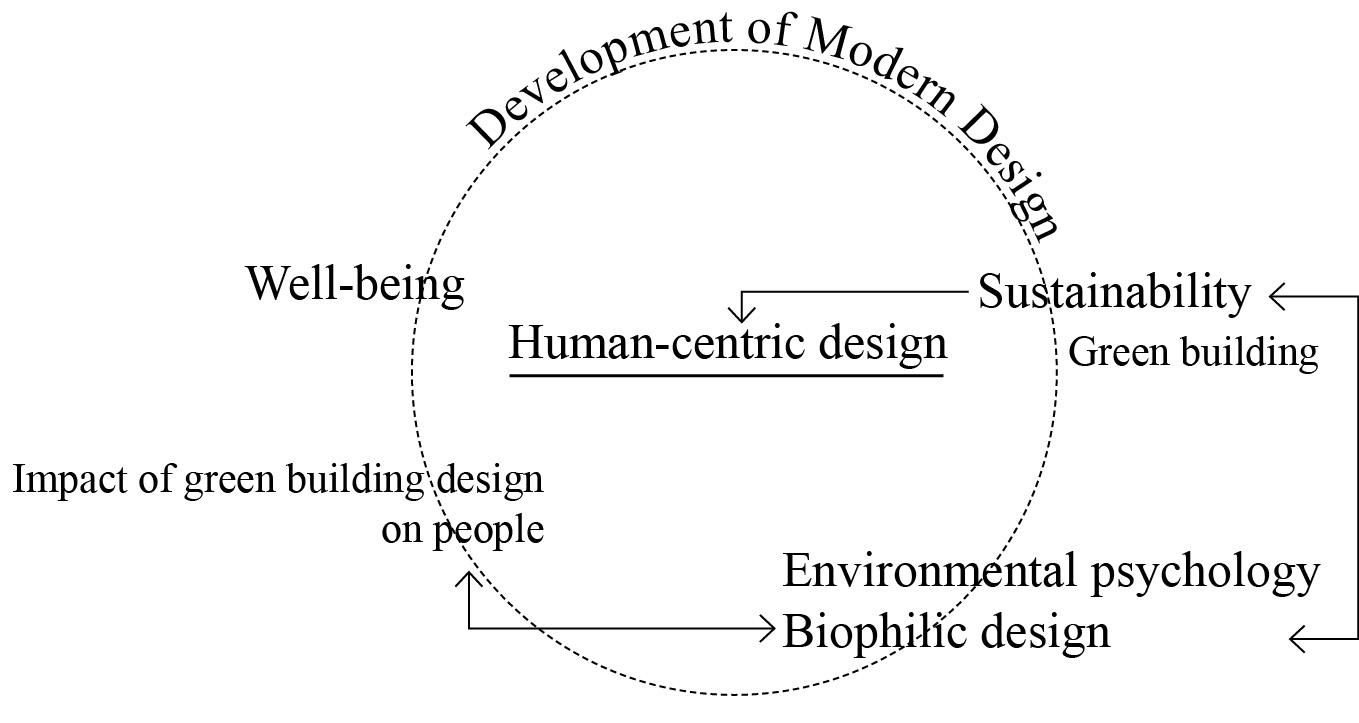

In the context of modern design, theoretical frameworks such as sustainable design, nature-friendly design, environmental psychology, and participatory design are concerned not only with the function and form of the structure, but also with how architectural design can be used to produce a living environment that is conducive to human health.

Sustainable design in green building is utilized to produce healthier and more comfortable indoor spaces by including ecologically friendly materials, energy-efficient technologies, and recycling. However, the initial version of the Green Building Reference Standard was utilized as a building-centered checklist to establish important sustainable design ideas. Herwagen, an environmental psychologist from the United States, suggested that human interests should be the focus of green building research, while Wilson’s proposed biophilic design demonstrated that contact with nature is critical to human physical and mental health. It modifies the intrinsic interaction between the built environment’s design

process and embodies the inherent connection between humans and nature.

13 14

Heerwagen et al. developed the biophilic design theory in 2.000 in conjunction with Wilson’s biophilic hypothesis, which emphasizes incorporating natural aspects into architectural design to improve people’s relationship with nature and increase health and well-being. Green vegetation, natural light, and landscape vistas are used to create architectural spaces that are more in tune with their surroundings.

15

Furthermore, environmental psychology seeks to explain how individuals interact with the built environment, how humans are inextricably linked to a physical location, and how people and places influence one another. Environmental psychologists the Kaplan and Roger Ulrich created the Attention Restoration and Stress Recovery Theories to assist explain why people feel healthier and happier in natural settings. According to the Attention Restoration Theory, natural environments offer an effortless concentration

known as “soft fascination,” which allows the mind to relax and heal. 16

Participatory design in architectural practice involves residents in the planning, design, and decision-making processes to ensure that the building satisfies their requirements and preferences, increases their sense of belonging and happiness with the building, and adds to their well-being.17

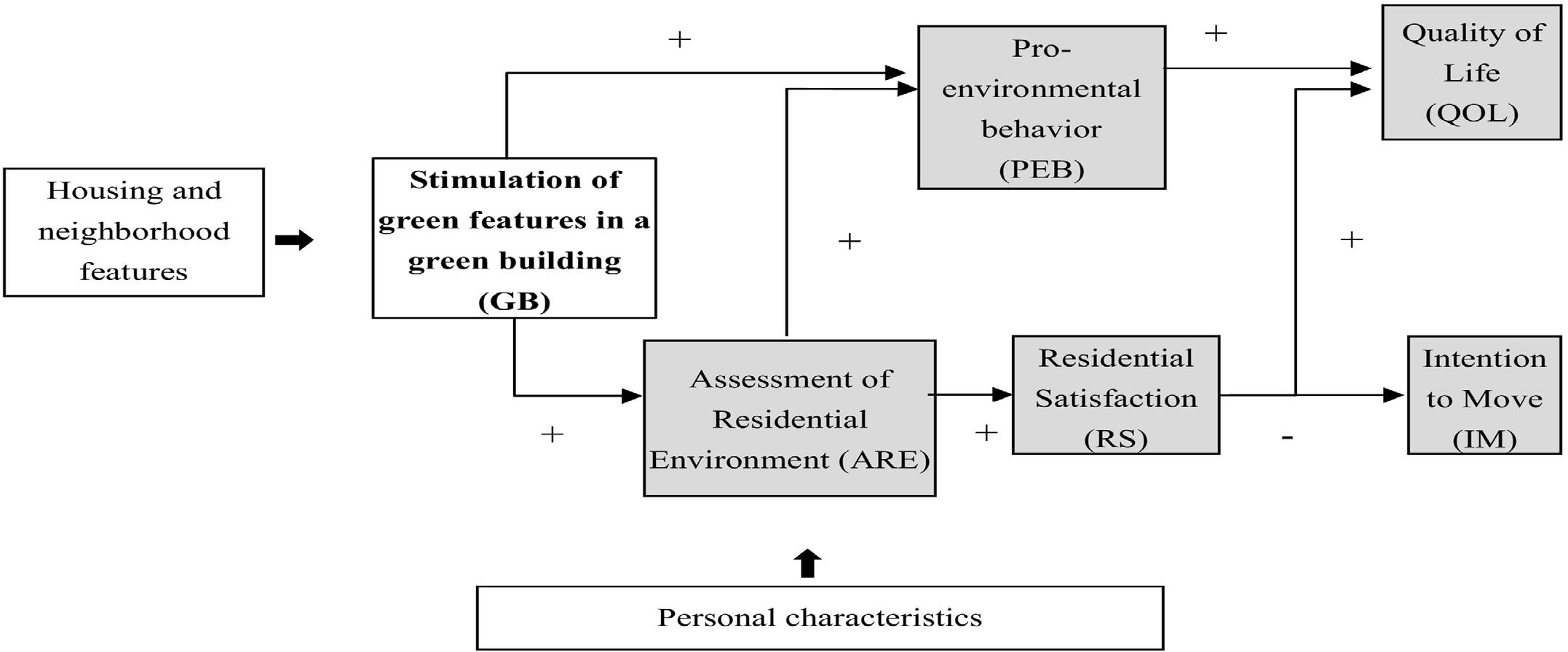

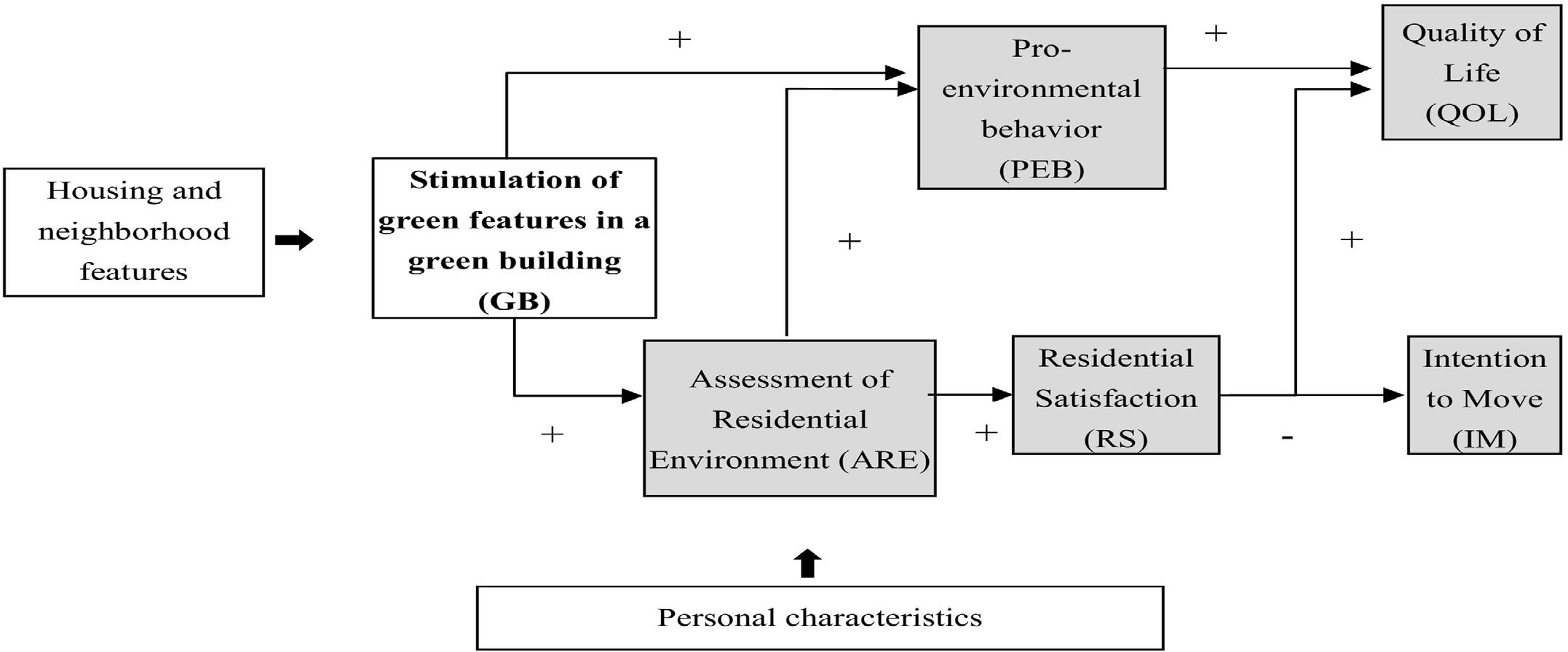

Combining these theories, we refer to Danlei et al.’s pro-environmental behavioural framework (Fig 3) to integrate these theories into a cohesive framework for promoting well-being (Fig 4), which provides an important theoretical basis for our study of green buildings’ contribution to promoting human well-being.18

(380 words)

05

3. Framework for the research of pro-environmental behaviour

(Source: Zhang, Danlei, and Yong Tu. 2021)

Fig 4. Theoretical research foundations of green buildings for human well-being

(Source: Drawn by author)

Fig

Fig

06

Design for Well-being

1. Green building can enhance well-being through natural elements

1.1 Objective well-being

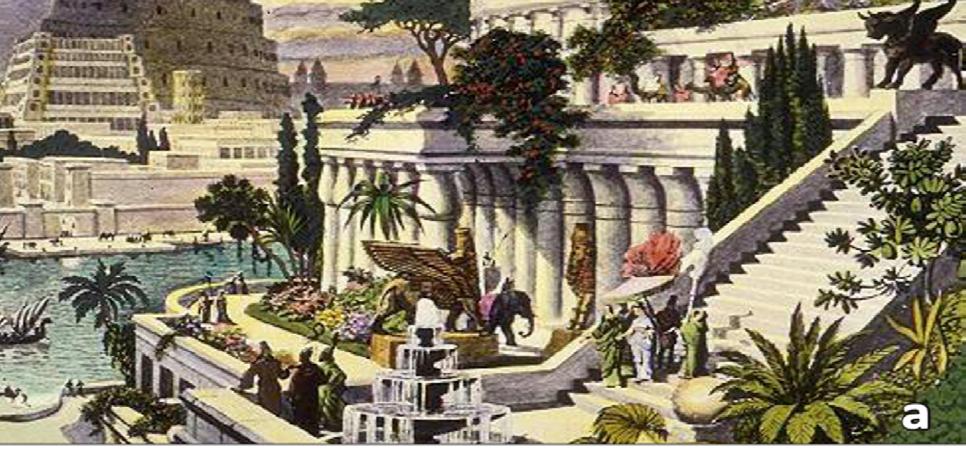

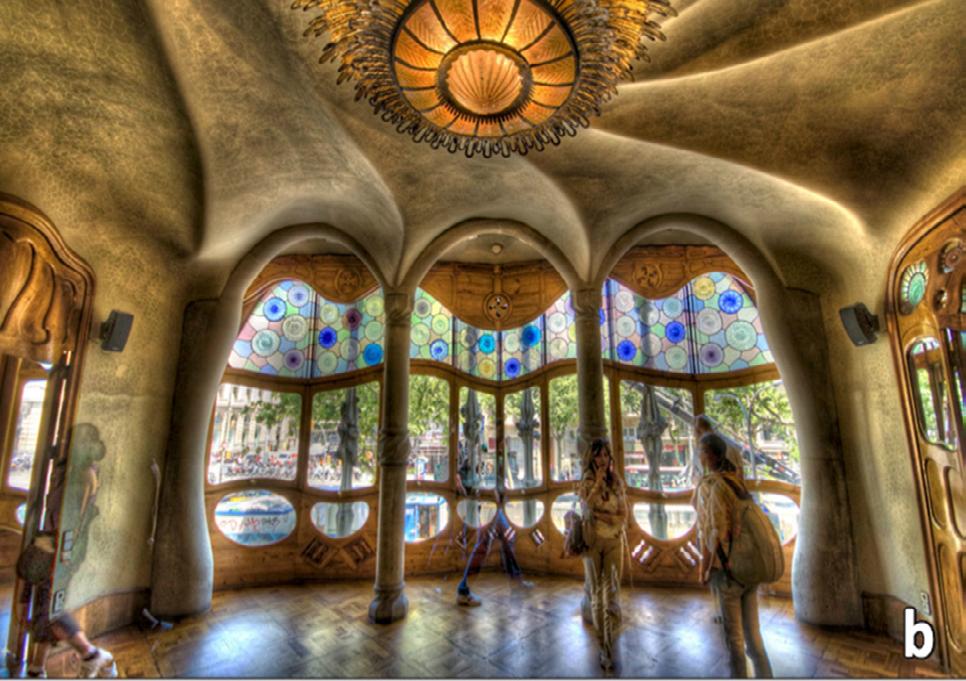

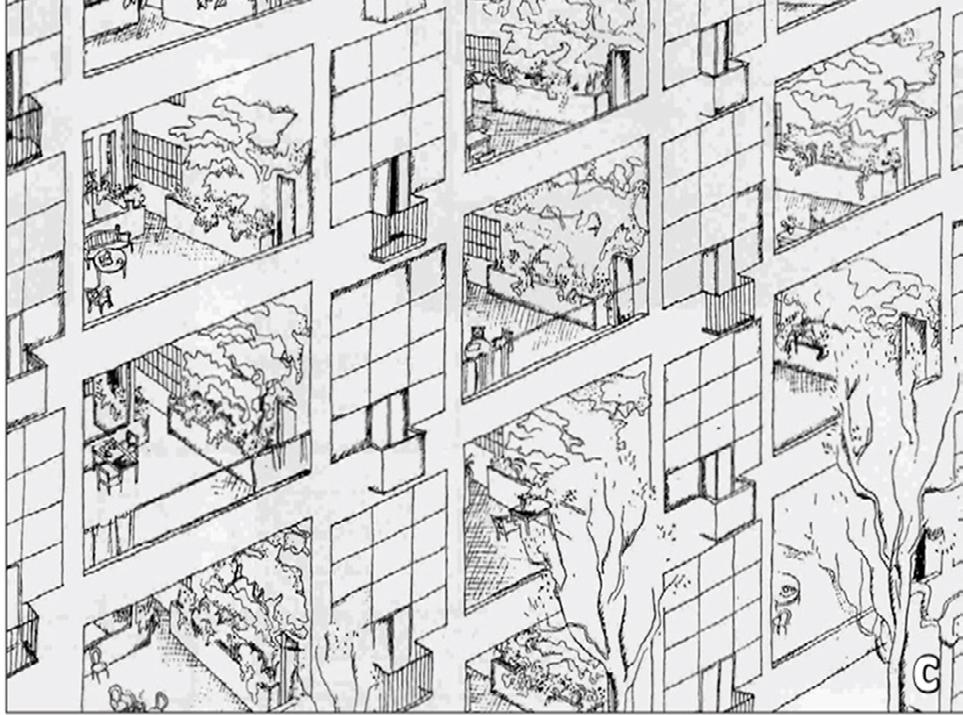

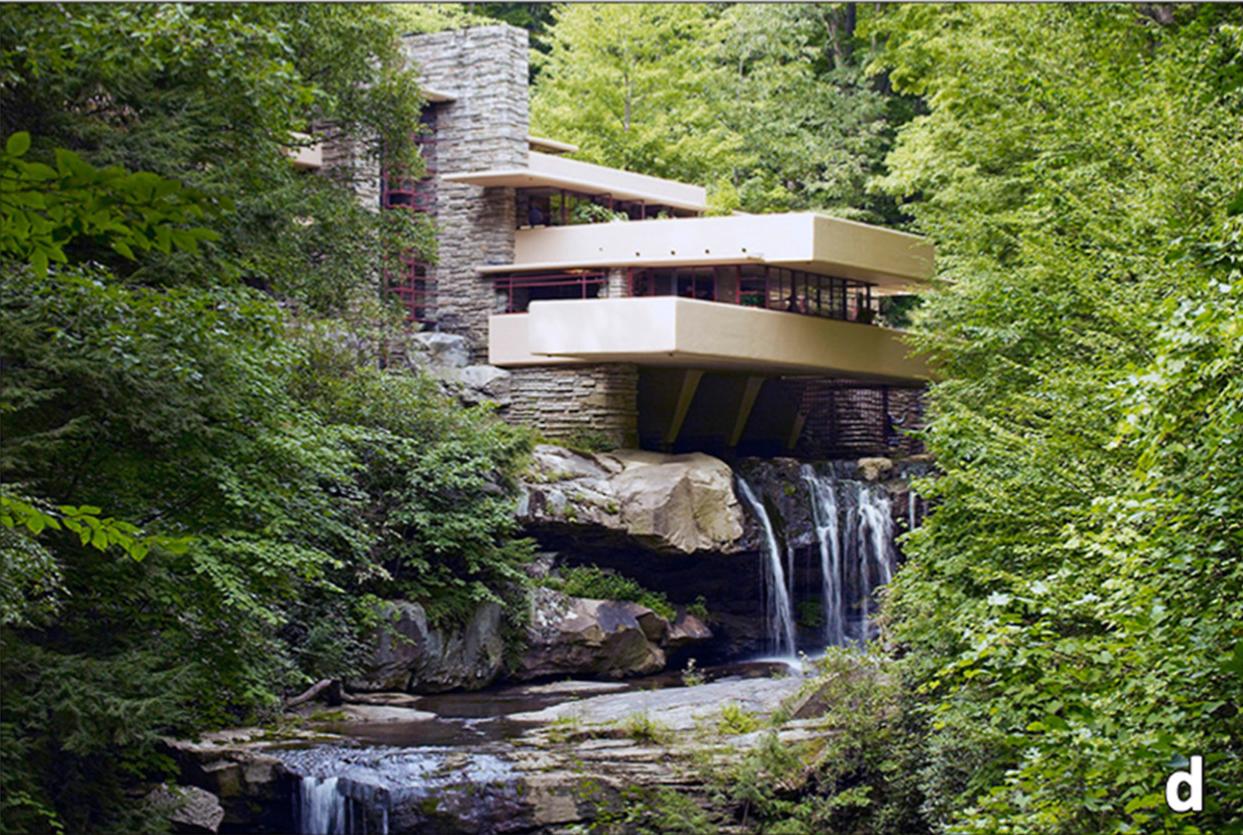

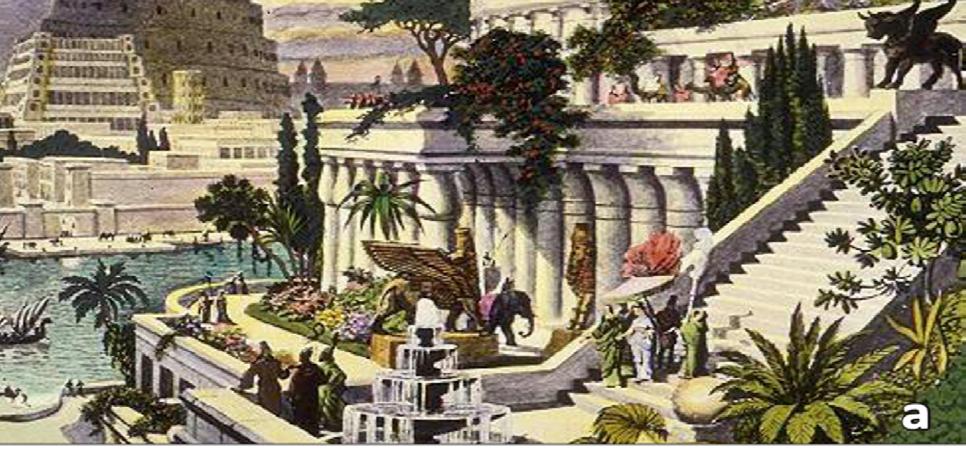

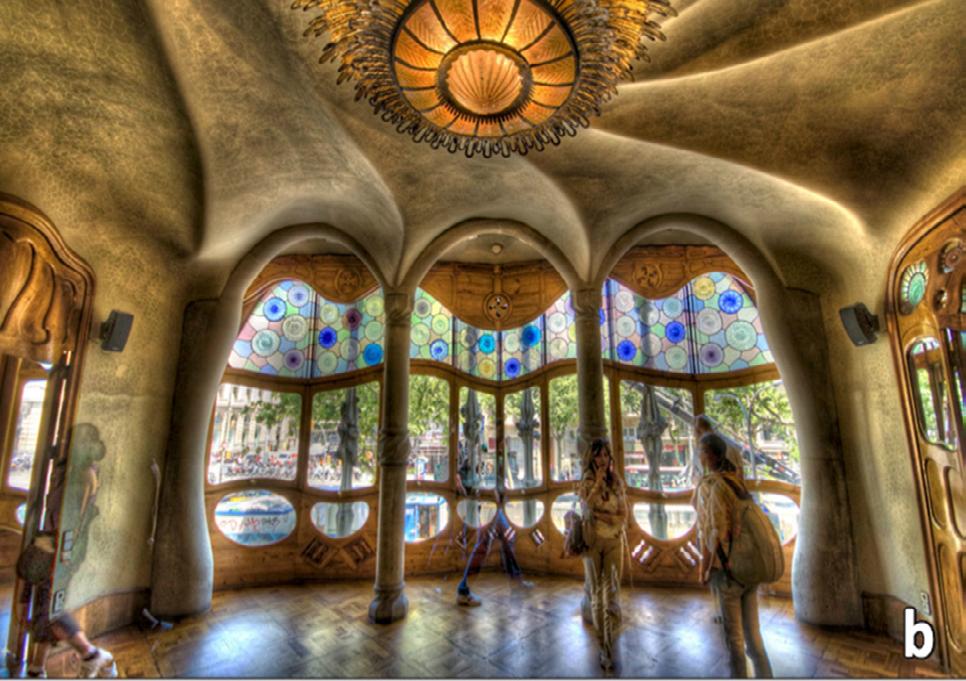

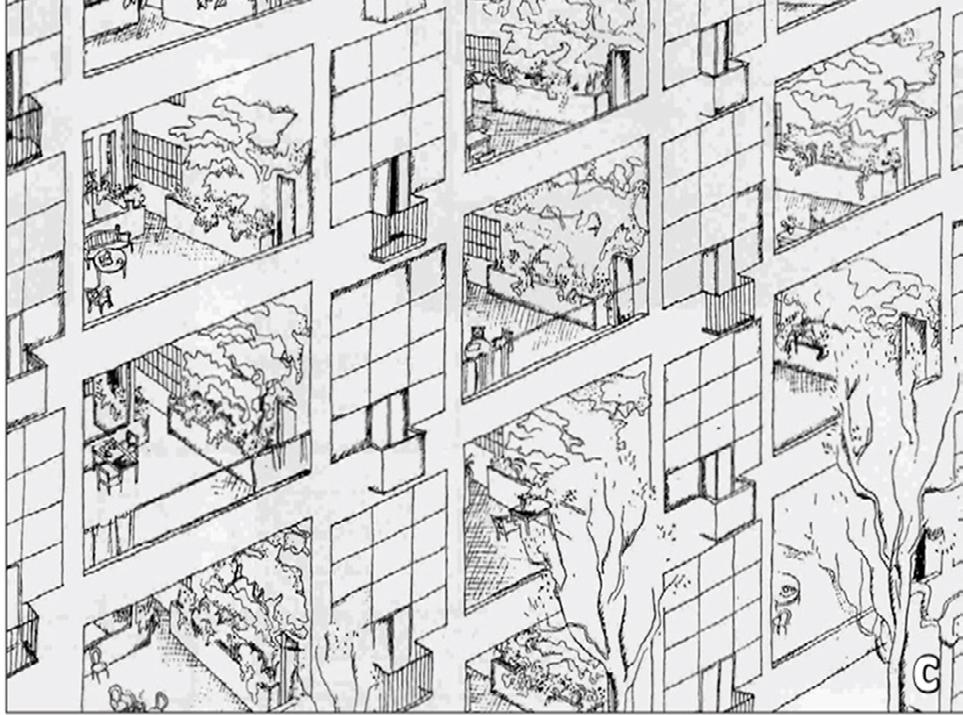

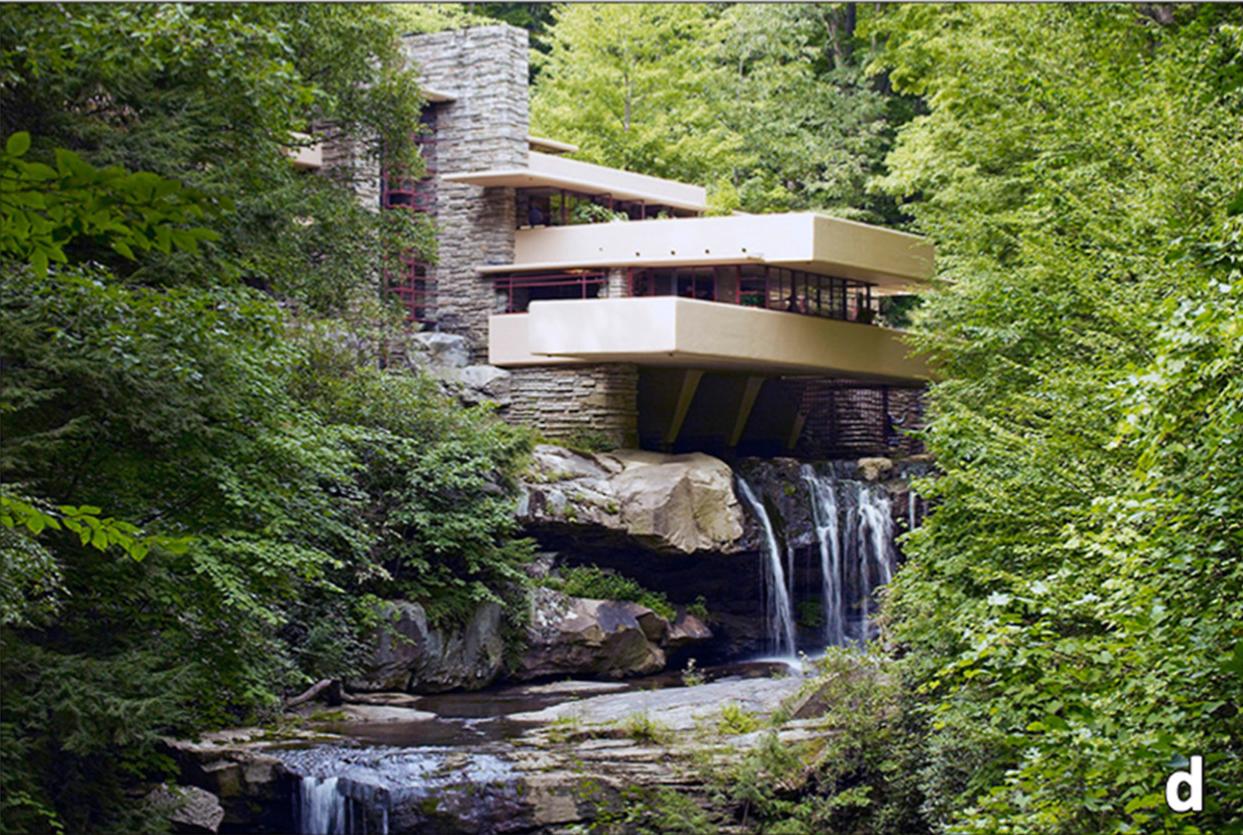

As evidenced by prior examples, architecture has a long history of incorporating natural elements into its designs (Fig 5). Incorporating environment-friendly components into green building design, such as the utilization of natural light, ventilation, and enhanced connectivity between buildings (indoors) and nature (outdoors), can benefit human health.

Humans spend the majority of their time working and living indoors, and one of the most important aspects of the human advantages of green buildings is the quality of the indoor environment. Joseph et al. demonstrated that green buildings that incorporate natural elements may achieve a higher level of indoor environmental quality than conventional buildings and that occupants of green buildings typically have better indoor environmental quality, which leads to improved health, such as fewer

respiratory symptoms and greater satisfaction with the living or working environment. 19 According to Xue et al, incorporating biophilic design into green buildings promotes the perception that contact between the constructed and natural environments might alleviate stress, anxiety, and depression while also improving mental health.20 The presence of natural components produces a more pleasant and personal environment, which aids in the strengthening of emotional bonds among residents and the community.As a result, incorporating natural elements into green buildings not only improves the quality of the living environment, but also improves the residents’ physical and mental health.

07

5. Examples of integrating plants, water or similar natural forms into buildings

Source: (a) Hanging Garden of Babylon (b) Antoni Gaudí’s Casa Batllo; (c) Le Corbusier's Immeubles-villas; (d) Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater

1.2 Subjective well-being

Incorporating natural components into green building design, such as natural light and green plants, can assist deliver richer and more varied sensory stimulation while encouraging the development and strengthening of cognitive capabilities.

Rachel and Stephen Kaplan’s Attention Restoration Theory proposes that contact with the natural world can increase attention, memory, creativity, and individuals’ cognitive levels.21Zhong et al. propose that putting green features into buildings and connecting them to the local natural environment can produce a “sense of place” and a “sense of community” which can lead to personal identification, a sense of belonging, and cohesion.22

It can not only improve people’s perspective and experience of the surroundings, but it can also encourage them to embrace healthier and more positive behaviours. For example, by shifting from the concept of occupants as passive recipients to occupants who actively contribute to their comfort.23

Incorporating natural features into green building design improves subjective well-being, creates healthier, more comfortable, and enjoyable living spaces, and meets people's requirements for a high quality of life.

(428 words)

Fig

08

Design for Well-being

2. Active participation can expand the well-being of the natural elements

2.1 Ownership and Responsibility

Active participation expresses the behaviour of residents who voluntarily participate in the green design and maintenance of green buildings.(Fig 6) For example, residents will consider how to better invite biophilic elements into their living spaces. According to Choguill, active participation in urban development enhances longevity by strengthening community ties and increasing residents’ sense of ownership and responsibility to proactively maintain their living environment.

24

Passive participation is a government- and designer-driven behaviour, where residents only receive information but have no decision-making power.(Fig 7) For example, multidisciplinary experts are involved in the structural technical and aesthetic design of green buildings, and Elizabeth OjoFafore et al. argue that passive par-

ticipation allows a wide range of people to benefit from green buildings, and is therefore more inclusive, which is in line with modern design concepts from a popular perspective.25 However, green buildings under modern design are more focused on individual preferences, which means they can be customised. Erwin Hofman et al. have articulated that builders customise their clients’ living spaces according to individual habits and preferences, thereby optimising personal comfort and health.26 Thus, in terms of impact on personal well-being, active engagement is an accelerator for passive engagement, which more precisely enhances the benefits of passive engagement for human well-being.

2.2 Sustainability

After a number of researchers, including kaplan, demonstrated that biophilic elements can improve the well-being of residents by increasing the comfort of the living environment, active participation in green building behaviours has

09

Fig 6. Resident participation in design (Source: sohailkhan2k22. 2024)

also been shown to directly encourage residents to interact with biophilic elements in a way that positively influences their subjective well-being. In 2009, Way Inn Koay and Denise Dillon demonstrated that residents who engaged in horticultural activities had significant positive effects on both physical and psychological well-being, particularly subjective well-being.27 The effects of active participation were a sense of self-gratification and a clear sense of responsibility, and these positive psychological activities made people more willing to actively think about and participate in the design of green buildings.

Passive participation is designed for the well-being of a broad group of people, architects and engineers will improve the building design according to the needs of a group of people, residents can benefit from it but cannot adjust it again according to their individual needs, however, green buildings with active participation can bring more subjective emotional value to promote the improvement of sustainable structures.

(396 words)

Fig 7. Government-supported green buildings

10

(Source: Fredericks, Murray, Michael Lassman, and Ryan Ng. 2019)

Theoretical Sources Support

According to Heerwagen, the key to green building is not how green you make it, but how you make it green, pointing out that in previous studies of green building design, cost and resource utilisation were always the primary considerations, and that green technologies and design strategies will improve indoor environmental quality, contributing more to human well-being than standard practices.She emphasized that previous research on green building design has always focused on cost and resource utilization, whereas green technologies and design strategies will improve the quality of indoor environments, making green buildings more conducive to human well-being than buildings that use standard practices.And she suggests that human well-being should be a hot topic in green building research.28 This provides a direction for our research.

Heerwagen, Judith H. et al. created the notion of biophilic design, which has been used in architecture to fulfill the “natural” desire. The concept of biophilic design has been established and utilized in architecture, with the goal of satisfying the demand for “nature” in building and drawing people’s attention to the necessity for interaction between humans and the natural world. It is critical to investigate how green buildings might connect with nature and improve human well-being.29

Furthermore, Xue, Zhong, et al. explored the use of pro-natural design in green buildings, arguing that it will boost health and well-being.30 This lends credence to our notion that green buildings can improve well-being through natural features.

The Kaplans’ have investigated the human experience of engaging with natural environments from an environmental psychology perspective, contributing to the understanding of why people feel healthier and happier in natural environments.31

Their theory of attentional restoration lends theoretical credence to the claim that adding natural components into design promotes human well-being and that active participation can increase the

11

benefits of natural elements. Ryan et al.’s research validates the uplifting effect of outside natural surroundings on individuals, i.e. the positive influence of natural habitats on individual health and well-being.32Danlei’s research provides an empirical study of the impact of green buildings on enhancing pro-environmental behaviours and well-being, as well as a framework for the study of pro-environmental behaviours, implying that green buildings can encourage their occupants to adopt environmentally friendly behaviours. 33

Sanoff investigates the advantages of participatory design approaches. He claims that integrating occupants in the design process promotes a sense of ownership and connection to the space, resulting in surroundings that better satisfy their requirements and improve psychological well-being.34

Forsyth et al. and Kosk contend that social involvement in residential architecture can be a transforming instrument for both the building and the individuals participating. Their findings highlight the need to integrate locals in the design and decision-making processes to improve sustainability and social cohesion. 35 36

Buildings can evolve to meet the diverse needs and preferences of their inhabitants by incorporating participatory approaches, such as creating shared spaces and involving users in the retrofitting process, fostering a sense of ownership and belonging. This collaborative approach affects not only the physical aspects of the built environment but also behavioral changes in sustainable living practices.

(553words)

12

Discussion

Attention Restoration Theory (ART) and Stress

Reduction Theory (SRT) are key theories on the positive impact of green spaces on well-being. These two theories provide a framework for understanding how biophilic elements in green buildings can enhance well-being.

The attention restoration theory proposed by the Kaplans in 1989 proves that the natural environment is restorative and helps to supplement cognitive abilities that have been dulled by urban life. The Kaplans pointed out that modern life requires long periods of concentration, and such a lifestyle can easily lead to mental fatigue. Natural environments composed of plants, natural light, water, etc., provide a relaxing distraction called soft fascination that allows the brain to recover from the exhaustion of cognitive overload.37 Incorporating biophilic elements such as indoor plants and natural materials in green buildings can create spaces conducive to spiritual recovery.

On this basis, the stress reduction theory pro-

posed by Roger Ulrich shows that exposure to the natural environment can significantly reduce physical distress and psychological stress. Even viewing the natural environment outside through a window can help reduce the production of stress hormones.38

In green buildings, applying biophilic design principles can create environments that promote relaxation and reduce stress. Natural ventilation and outdoor green spaces are both practices of SRT theory in green buildings, and these elements help create a healthier living and working environment.

design and stress recovery, and bring subjective emotional value. A sense of ownership and positive subjective emotions will also encourage people to continue to improve green building design in depth, thereby achieving sustainable development.

Applying ART and SRT theories in green buildings combines biophilic elements and participatory design. Architects and engineers can support their occupants’ physical health and mental recovery by increasing daylighting and using natural materials when creating green buildings. The active participation of residents can establish a connection with the space according to personal circumstances, improve subjective emotional value, bring a higher sense of happiness, and promote the improvement of green buildings.

Based on ART and SRT, residents’ active participation in the design of green buildings has promoted the improvement of well-being. Active participation is a manifestation of residents’ voluntary design and maintenance of green buildings, which enhances their sense of ownership.39 Participatory design can make the spatial layout of the building better meet individual needs, amplify the effects of biophilic (386 words)

13

Conclusion

The practice of green building, influenced by modern design principles, has a positive impact on human well-being. Green architecture integrates natural elements and invites the outdoors into the indoor space, providing living environments that promote physical and mental well-being, and the Kaplan’s theory of attention restoration and Ulrich’s theory of stress reduction provide a framework for this argument, explaining how natural elements in architectural spaces can enhance cognitive abilities and calm negative emotions.

Participatory design has been shown to directly encourage residents to interact with nature, develop a sense of ownership, and become more actively involved in the design and maintenance of green buildings. At the same time, participatory design can adjust the space according to individual preferences, pinpointing the benefits of well-being to the individual, and encouraging residents to actively participate in the improvement of green buildings to achieve sustainable development.

We have demonstrated that nature-friendly elements can enhance well-being and that active participation can magnify the effect of well-being. By combining ART, SRT, and participatory design, green building projects can create individually tailored environments that support physical and mental health, thereby promoting well-being.

By examining other works and theoretical frameworks, we can expand our understanding and discover new insights to further advance the field of green building design.

Alexander emphasizes the importance of designing living buildings that are in tune with the natural order. 40 By embracing his ideals, green building design can progress to produce environments that not only sustain human life, but also enliven and enrich it, creating a greater sense of well-being. Green buildings of the future should continue to explore this fabric of life, improving their residents’ general well-being and happiness via healthy coexistence with nature.

Green building design not only improves resident well-being, but it also promotes longterm development. In the future, promoting the growth of green building design will require the integration of attention restoration theory, participatory design, human factors engineering concepts, and regenerative design. We can create more compassionate and sustainable built environments that benefit urban development and human well-being by working together.

(341 words)

14

Endnotes

1.Cedeño-Laurent, J.G., A. Williams, P. MacNaughton, X. Cao, E. Eitland, J. Spengler, and J. Allen. 2018. “Building Evidence for Health: Green Buildings, Current Science, and Future Challenges.” Annual Review of Public Health 39 (1): 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1146/ annurev-publhealth-031816-044420.

2. Colomina, Beatriz, and Mark Wigley. 2016. Are We Human? : Notes on an Archaeology of Design. Zürich, Switzerland: Lars Muller.

3. Carpenter, Megan, and Steven Hetcher. 2014. “FUNCTION over FORM: BRINGING the FIXATION REQUIREMENT into the MODERN ERA.” Fordham Law Review 82: 179–229.

4. Apanaviciene, Rasa, Rokas Urbonas, and Paris A. Fokaides. 2020. “Smart Building Integration into a Smart City: Comparative Study of Real Estate Development.” Sustainability 12 (22): 9376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ su12229376.

5. Colomina, Beatriz, and Mark Wigley. 2016. Are We Human? : Notes on an Archaeology of Design. Zürich, Switzerland: Lars Muller.

6. Kaplan, Rachel, and Stephen Kaplan. 1989. The Experience of Nature : A Psychological Perspective. Ann Arbor, Mi: Ulrich’s Bookstore, Cop.

7. Hartig, Terry, Marlis Mang, and Gary W. Evans. 1991. “Restorative Effects of Natural Environment Experiences.” Environment and Behavior 23 (1): 3–26. https://doi. org/10.1177/0013916591231001.

8. Ulrich, Roger. 1984. “View through Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery.” Science 224 (4647): 420–21. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6143402.

9. Schuler, Douglas, and Aki Namioka. 1993. Participatory Design : Principles and Practices. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates.

10. Zhang, Danlei, and Yong Tu. 2021. “Green Building, Pro-Environmental Behavior and Well-Being: Evidence from Singapore.” Cities 108 (January): 102980. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102980.

11. Thatcher, Andrew, and Karen Milner. 2012. “The Impact of a ‘Green’ Building on Employees’ Physical and Psychological Wellbeing.” Work 41 (Supplement 1): 3816–23. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2012-0683-3816.

12. Ryan, Richard M., Netta Weinstein, Jessey Bernstein, Kirk Warren Brown, Louis Mistretta, and Marylène Gagné. 2010. “Vitalizing Effects of Being Outdoors and in Nature.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (2): 159–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.10.009.

13.Heerwagen Judith, “Green Buildings, Organizational Success and Occupant Productivity,” Building Research & Information 28, no. 5-6 (September 2000): 353–67, https://doi.org/10.1080/096132100418500.

14.Wilson, Edward O. 1984. Biophilia. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

15. Heerwagen, Judith H, Stephen R Kellert, and Martin L Mador. 2008. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Hoboken, Nj:

Wiley.

16. Kaplan, Rachel, and Stephen Kaplan. 1989. The Experience of Nature : A Psychological Perspective. Ann Arbor, Mi: Ulrich’s Bookstore, Cop.

17. Luck, Rachael. 2018. “Participatory Design in Architectural Practice: Changing Practices in Future Making in Uncertain Times.” Design Studies 59 (November): 139–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2018.10.003.

18. Allen, Joseph G., Piers MacNaughton, Jose Guillermo Cedeno Laurent, Skye S. Flanigan, Erika Sita Eitland, and John D. Spengler. 2015. “Green Buildings and Health.” Current Environmental Health Reports 2 (3): 250–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-015-0063-y.

19.Xue, Fei, Stephen SiuYu Lau, Zhonghua Gou, Yifan Song, and Boya Jiang. 2019. “Incorporating Biophilia into Green Building Rating Tools for Promoting Health and Wellbeing.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 76 (May): 98–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.eiar.2019.02.004.

20.Kaplan, Rachel, and Stephen Kaplan. 1989. The Experience of Nature : A Psychological Perspective. Ann Arbor, Mi: Ulrich’s Bookstore, Cop.

21.Zhong, Weijie, Torsten Schröder, and Juliette Bekkering. 2021a. “Biophilic Design in Architecture and Its Contributions to Health, Well-Being, and Sustainability: A Critical Review.” Frontiers of Architectural Research 11 (1): 114–41.https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.foar.2021.07.006.

15

22.Zhang, Danlei, and Yong Tu. 2021. “Green Building, Pro-Environmental Behavior and Well-Being: Evidence from Singapore.” Cities 108 (January): 102980. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102980.

23.Heerwagen, Judith. 2000. “Green Buildings, Organizational Success and Occupant Productivity.” Building Research & Information 28 (5-6): 353–67. https://doi. org/10.1080/096132100418500.

24.Choguill, Charles L. 1996. “Toward Sustainability of Human Settlements.” Habitat International 20 (3): v–viii. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-3975(96)81830-3.

25.OjoFafore, Elizabeth, Clinton Aigbavboa, and Pretty Remaru. 2018. “Benefits of Green Buildings.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, 2289–97.

26. Hofman, Erwin, Johannes I. M. Halman, and Roxana A. Ion. 2006. “Variation in Housing Design: Identifying Customer Preferences.” Housing Studies 21 (6): 929–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030600917842.

27. Koay, Way Inn, and Denise Dillon. 2020. “Community Gardening: Stress, Well-Being, and Resilience Potentials.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (18): 6740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijerph17186740.

28. Heerwagen, Judith H, Stephen R Kellert, and Martin L Mador. 2008. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Hoboken, Nj: Wiley.

29. Heerwagen, Judith H, Stephen R Kellert, and Martin L Mador. 2008. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Hoboken, Nj: Wiley.

30. Xue, Fei, et al. “Incorporating Biophilia into Green Building Rating Tools for Promoting Health and Wellbeing.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review, vol. 76, May 2019, pp. 98–112

31.Kaplan, Rachel, and Stephen Kaplan. 1989. The Experience of Nature : A Psychological Perspective. Ann Arbor, Mi: Ulrich’s Bookstore, Cop.

32.Ryan, Richard M., Netta Weinstein, Jessey Bernstein, Kirk Warren Brown, Louis Mistretta, and Marylène Gagné. 2010a. “Vitalizing Effects of Being Outdoors and in Nature.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (2): 159–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.10.009.

33.Zhang, Danlei, and Yong Tu. 2021. “Green Building, Pro-Environmental Behavior and Well-Being: Evidence from Singapore.” Cities 108 (January): 102980. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102980.

34.Sanoff, Henry. Community participation methods in design and planning. John Wiley & Sons, 1999.

35.Forsyth, Ann, Gretchen Nicholls, and Barbara Raye. “Higher density and affordable housing: Lessons from the corridor housing initiative.” Journal of Urban Design 15.2 (2010): 269-284.

36.Kosk, Katarzyna. “Social participation in residential architecture as an instrument for transforming both the

architecture and the people who participate in it.” Procedia engineering 161 (2016): 1468-1475.

37.Kaplan, Rachel, and Stephen Kaplan. 1989. The Experience of Nature : A Psychological Perspective. Ann Arbor, Mi: Ulrich’s Bookstore, Cop.

38.Ulrich, Roger S., Robert F. Simons, Barbara D. Losito, Evelyn Fiorito, Mark A. Miles, and Michael Zelson. 1991. “Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 11 (3): 201–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/s02724944(05)80184-7.

39.Schuler, Douglas, and Aki Namioka. 1993. Participatory Design : Principles and Practices. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates.

40.Alexander, Christopher, and Center For Environmental Structure. 2002. The Nature of Order : An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe. Berkeley: Center For Environmental Structure. (957 words)

words)

16

All:(4060

Bibliography

Alexander, Christopher, and Center For Environmental Structure. 2002. The Nature of Order : An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe. Berkeley: Center For Environmental Structure.

Allen, Joseph G, and John D Macomber. 2020. Healthy Buildings : How Indoor Spaces Drive Performance and Productivity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Allen, Joseph G., Piers MacNaughton, Jose Guillermo Cedeno Laurent, Skye S. Flanigan, Erika Sita Eitland, and John D. Spengler. 2015. “Green Buildings and Health.” Current Environmental Health Reports 2 (3): 250–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-015-0063-y.

Apanaviciene, Rasa, Rokas Urbonas, and Paris A. Fokaides. 2020. “Smart Building Integration into a Smart City: Comparative Study of Real Estate Development.” Sustainability 12 (22): 9376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ su12229376.

Carpenter, Megan, and Steven Hetcher. 2014. “FUNCTION over FORM: BRINGING the FIXATION REQUIREMENT into the MODERN ERA.” Fordham Law Review 82: 179–229.

Cedeño-Laurent, J.G., A. Williams, P. MacNaughton, X. Cao, E. Eitland, J. Spengler, and J. Allen. 2018. “Building Evidence for Health: Green Buildings, Current Science, and Future Challenges.” Annual Review of Public

Health 39 (1): 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurevpublhealth-031816-044420.

Choguill, Charles L. 1996. “Toward Sustainability of Human Settlements.” Habitat International 20 (3): v–viii. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-3975(96)81830-3.

Colomina, Beatriz, and Mark Wigley. 2016. Are We Human? : Notes on an Archaeology of Design. Zürich, Switzerland: Lars Mul̈ler.

Hartig, Terry, Marlis Mang, and Gary W. Evans. 1991. “Restorative Effects of Natural Environment Experiences.” Environment and Behavior 23 (1): 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916591231001.

Heerwagen, Judith. 2000. “Green Buildings, Organizational Success and Occupant Productivity.” Building Research & Information 28 (5-6): 353–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/096132100418500.

Heerwagen, Judith H, Stephen R Kellert, and Martin L Mador. 2008. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Hoboken, Nj: Wiley.

Herzog, Thomas R., Colleen, P. Maguire, and Mary B. Nebel. 2003. “Assessing the Restorative Components of Environments.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 23 (2): 159–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S02724944(02)00113-5.

Hofman, Erwin, Johannes I. M. Halman, and Roxana A. Ion. 2006. “Variation in Housing Design: Identifying Customer Preferences.” Housing Studies 21 (6): 929–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030600917842.

Hu, Ming, Madlen Simon, Spencer Fix, Anthony A. Vivino, and Edward Bernat. 2021. “Exploring a Sustainable Building’s Impact on Occupant Mental Health and Cognitive Function in a Virtual Environment.” Scientific Reports 11 (1): 5644. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41598-021-85210-9.

Kaplan, Rachel, and Stephen Kaplan. 1989. The Experience of Nature : A Psychological Perspective. Ann Arbor, Mi: Ulrich’s Bookstore, Cop.

Koay, Way Inn, and Denise Dillon. 2020. “Community Gardening: Stress, Well-Being, and Resilience Potentials.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (18): 6740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijerph17186740.

Kuo, Frances E, and William C Sullivan. 2001. “Environment and Crime in the Inner City: Does Vegetation Reduce Crime?” Environment and Behavior 33 (3): 343–67.

Luck, Rachael. 2018. “Participatory Design in Architectural Practice: Changing Practices in Future Making in Uncertain Times.” Design Studies 59 (November): 139–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.destud.2018.10.003.

17

OjoFafore, Elizabeth, Clinton Aigbavboa, and Pretty Remaru. 2018. “Benefits of Green Buildings.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, 2289–97.

Romm, Joseph. n.d. “Increasing Productivity through Energy-Efficient Design G R E E N I N G T H E B U I L D I N G a N D T H E B O T T O M L I N E.” https://www. terrapinbrightgreen.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/ Greening_the_Building_and_the_Bottom_Line.pdf.

Ryan, Richard M., Netta Weinstein, Jessey Bernstein, Kirk Warren Brown, Louis Mistretta, and Marylène Gagné. 2010. “Vitalizing Effects of Being Outdoors and in Nature.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (2): 159–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.10.009.

Schuler, Douglas, and Aki Namioka. 1993. Participatory Design : Principles and Practices. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Thatcher, Andrew, and Karen Milner. 2012. “The Impact of a ‘Green’ Building on Employees’ Physical and Psychological Wellbeing.” Work 41 (Supplement 1): 3816–23. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2012-0683-3816. Ulrich, Roger. 1984. “View through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery.” Science 224 (4647): 420–21. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6143402.

Ulrich, Roger S., Robert F. Simons, Barbara D. Losito, Evelyn Fiorito, Mark A. Miles, and Michael Zelson.

1991. “Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 11 (3): 201–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/ s0272-4944(05)80184-7.

Wilson, Edward O. 1984. Biophilia. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Zhang, Danlei, and Yong Tu. 2021. “Green Building, ProEnvironmental Behavior and Well-Being: Evidence from Singapore.” Cities 108 (January): 102980. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102980.

Zhong, Weijie, Torsten Schröder, and Juliette Bekkering. 2021. “Biophilic Design in Architecture and Its Contributions to Health, Well-Being, and Sustainability: A Critical Review.” Frontiers of Architectural Research 11 (1): 114–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2021.07.006.

18

Aknowledgement

This thesis is the first time in two years that we have known each other, and we have worked together on a single outcome for the entirety of our lives. It is the final assignment for both of us in our graduate studies. At this point in our journey, it means that our milestone-like two years have come to a close.

First of all, I would like to thank Prof Samer Akkach for helping us with our new knowledge and logic of academic writing. We were lost and anxious during the process of completing this piece of writing, but Prof Samer Akkach's patient answers at every stage gave us some inspiration and made our progress smooth.Secondly, we would like to thank all the professors and tutors we have met over the past two years.This essay is not just about our views on society and architecture, but it is also a feedback of the knowledge we have learnt over the past two years, so thank you to all the tutors for passing on their knowledge to us over the past two years.

Finally, it is our thanks to each other. The argument during the completion of this article was the first one we had in the two years we have known each other, but each other would calm down as soon as possible to find a new solution and finally finish this article together.

We believe that every experience is learning and growing, expanding the width of life. Thank you to the University of Adelaide for providing us with educational resources.

19

尾注

CheckList

⃝ Adhered to the word limit in the summary and the article.

⃝ Inserted the main quote by C+W on the inside of the front cover.

⃝ Followed the 5-sentence template in writing of the summary.

⃝ Inserted word count of the summary.

⃝ Inserted word count of the article.

⃝ Adhered to the prescribed number of spreads.

⃝ Adhered to the prescribed number of images.

⃝ Researched and cited the required number of sources.

⃝ Uploaded PDF file on issuu.com and provided active link on the from cover.

⃝ Inserted the checklist on the back cover.

⃝ Uploaded final PDF file on MyUni and Box.

⃝ Uploaded final Black+Blue word file on MyUni and Box.

Student 1 Student 2

Name:Yu Xu A1834380

Name:Yiding Yan A1841855

√ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √ √

Fig

Fig