Best of 2022

Ego of the Month, pg. 7

Modigliani, pg. 24

Community Gardens, pg. 14

Internet Trends, pg. 38

The WALK’s 27L, pg. 44

Legal Weed, pg. 20

Tár Review, pg. 50

Best Albums, pg. 30

Best Film & TV, pg. 34

Word on the Street, pg. 5

Ego of the Month, pg. 7

Modigliani, pg. 24

Community Gardens, pg. 14

Internet Trends, pg. 38

The WALK’s 27L, pg. 44

Legal Weed, pg. 20

Tár Review, pg. 50

Best Albums, pg. 30

Best Film & TV, pg. 34

Word on the Street, pg. 5

The Land on which the office of The Daily Pennsylvanian stands is a part of the home land and territory of the Lenni–Lenape people. Per the Diversity Committee, we affirm Indigenous sovereignty and will work to hold the DP and the University of Pennsylvania more accountable to the needs of Indigenous people.

From dragon mommies to fields of Illinois corn, we compiled the best of this year’s narratives into one grid of graphics for you.

Cover by Tyler Kliem

If you have questions, comments, com plaints or letters to the editor, email Emily White, Editor–in–Chief, at white@34st.com You can also call us at (215) 422–4640. www.34st.com © 2021 34th Street Magazine, The Daily Pennsylvanian, Inc. No part may be reproduced in whole or in part without the express, written consent of the editors. All rights reserved.

Emily White, Editor–in–Chief white@34st.com

Eva Ingber, Digital Managing Editor ingber@34st.com

Walden Green, Print Managing Editor green@34st.com

Arielle Stanger, Assignments Editor stanger@34st.com

Hannah Lonser, Features Editor

Jean Paik, Focus Editor

Natalia Castillo, Style Editor

Alana Bess, Ego Editor

Kate Ratner, Music Editor

Irma Kiss, Arts Editor

Jacob A. Pollack, Film & TV Editor

Andrew Yang, Multimedia Editor

Kayla Cotter, Social Media Editor

Tyler Kliem, Design Editor

Sophie Apfel, Copy Editor

Collin Wang, Deputy Design Editor

Alice Choi, Deputy Design Editor

STAFF

Features Staff Writers

Sejal Sangani, Avalon Hinchman, Dedeepya Guthikodna, Katie Bartlett Focus Beat Writers

Samara Himmelfarb, Anna O’Neill–Dietel, Sara Heim Style Beat Writers

Shelby Abayie, Naima Small, Vikki Xu Music Beat Writers

Derek Wong, Grayson Catlett, Halla Elkhwad, Hannah Sung Arts Beat Writers

Jessa Glassman, Emily Maiorano, Grace Busser, Luiza Louback Fontes, Katrina Itona, Eyana Lao Film & TV Beat Writers

Alex Baxter, Emma Marks, Catherine Sorrentino, Weike Li, Rahul Variar Ego Beat Writers

Anjali Kishore, Norah Rami, Sophie Barkan, Riane Lumer

Staff Writers

Ryanne Mills, Morgan Crawford, Olivia Reynolds, Cassidee Jackson, Caroline Clarke, Emma Halper, Alexandra

Kanan

Multimedia Associates

Roger Ge, Derek Wong, Andrea

Barajas, Rachel Zhang, Samita Gupta, Sophie Cai, Hannah Shumsky, Priya Bhavikatti, Nathaniel Babitts, Serene Safvi, Giuliana Alleva, Liz Zhang

Audience Engagement Associates

Kayla Cotter, Yamila Frej, Katherine Han, Emily Xiong, Ivanna Dudych, Felicitas Tananibe, Ainnie Bingle, Lauren Pantzer

Dear Walden, Arielle, Alana, and Collin:

2022 was a big year for Street. I think I always knew it would be, even from the day we were elected and screamed “GLOSSY MAG!” to Walnut Street at 1 a.m.

We had big dreams. And most of them came true.

Decades of newsprint magazines were bid farewell to usher in a new age of glossy paper, and we finally emerged from COVID–19 pan demic–era Street into reimagined normalcy. We returned to BYOs and IRL production nights, and with these transitions we learned the perils of spending too much time in a windowless office.

Now that my time here is coming to an end, I’m not sure how to sum it all up. Most of these letters are a snapshot of the moment I write them, a dispatch from a particular version of myself. This one is a collage of a year, and it’s still being pieced together.

But your time has just begun. You have a year’s worth of blank pag es—416 of them, to be exact—to fill however you choose. Street will be yours, to lead as you wish.

You’ll spend months lamenting the hours you put into this place only to panic at the thought of what you’ll do when it’s no longer the center of your world. You’ll buy each other boba on the way to the of fice and walk each other home when you’re done for the night. You’ll celebrate the changes that have been made already and try out a few of your own.

And some day when you think back on your tenure at 4015 Walnut St., you’ll feel just like I do now—how so many editors–in–chief felt before me. You’ll be ready for a long nap and a three–week vacation, but you’ll also be incredibly proud.

All I ask is this: Take care of our little magazine. More importantly, take care of each other. This job isn’t easy, and it will challenge you in a different way each day. But you’ll be a bit better for each lesson you learn, and hopefully so will Street.

One last time,

For the past 365 days, I've kept a photo diary on Instagram, docu menting the minutiae of every day life—the joyful moments and the chal lenging ones, too. One year has amounted to dozens of sweet, lighthearted photos

with friends old and new, too many pho tos of food captured moments before rav enous consumption, at least half a dozen outfit–of–the–day videos, and the occa sional selfie of me grinning and bearing the pain of academic dread.

My photo diary is not a “perfectly” cu rated feed of my highlights throughout the year—trust me, my massive following (a whopping 17 family and friends) will tell you that I’m incredibly #real with #nofilter.

Some odd inclination motivated me to document the 365 days that spanned my first months of college to a summer at home and my eventual return to campus. This feed captures the birth and even tual blossoming of new friendships, my first attempts at learning to play water polo, and the subsequent concussion. It captures moments of deep academic and existential dread, but also showcases the pure joy that accompanied my first cre ative writing endeavors. In retrospect, I realize that I tend to look back on mo ments in my life and label them as ob jectively good or objectively bad when in reality, my day–to–day life is a patchwork quilt of small joys and also small sorrows.

Now that I’ve made it to the one–year birthday of this photo diary, I dig deep into the recesses of my mind to remember what spurred me to start the project in the first place. During my first semester at Penn, I was swept up in the chaos of collegiate life and convinced myself that I had nothing to show for my time so far. I spent nights toil ing away until mid night only to trudge across the same, famil iar path between Van Pelt and the Upper Quad gate, eventually finding myself back in my dorm, looking in the mirror, never quite recognizing the face that stared back at me. Deep–seated eye bags took up per manent residence on my face, and I looked older, but somehow I didn’t feel any wis er. Moments slipped through my fingers against my will. I felt like I was supposed to be a part of something bigger, something more momentous, but I was trapped in a half–dazed state.

Time passes agonizingly slow and also far too quickly when your calendar is filled with lectures, exams, club meetings, and the occasional social outing. Before I could realize what was happening, days became

weeks, and suddenly it was November, and I couldn’t remember how I'd spent the first three months of what were supposed to be “the best years of my life.” I knew I was growing for the better, but I could never quite slow down for long enough to catch my breath and appreciate the true depth of my experiences.

I wanted to find some way to remember all the good moments gone by and remedy my frustration with the passage of time. I resolved to pull myself out of the hazy un certainty of young adulthood. On Nov. 10, 2021, I made my first post to the Instagram account where I'd continue to document one photo a day for the indefinite future. I

entirely self–directed, I also sincerely enjoy sharing what’s happening in my life with dear friends and family whom I don’t speak to as often as I’d like.

Trying to answer what’s motivated me to maintain this photo diary for a whole year, I think of how cathartic it is to open my cam era roll at the end of a long day and give my self a quiet moment to reflect. I’ve learned what it looks and feels like to equally honor all my emotions. It’s deeply rewarding to look back on my highs and lows and relive those experiences with the benefit of hind sight.

marked each post with the date and occa sionally wrote in the caption about some thing that brought me joy or vented about whatever weighed on my mind that day.

One year later, this photo diary has been an active exercise in appreciating the mi nutiae of my everyday life. To sweeten the deal, it's carved out a space for those I hold near and dear to share in these moments with me. Whether it’s my roommate down the hall, or my mom and dad on the other side of the country, they’re all supportive of my silly daily antics, offering a listening ear when I need it most. They cheer me on in the comment section or express sincere concern for my mental state in the event of an unhappy midnight selfie post. While this photo diary is incredibly personal and

And on late nights when I yearn for mo ments gone by, I lose myself in grid posts of sloping San Francisco hills and never–end ing car rides to water polo tournaments. I’ve built an entire world of four–by–six images, and it’s en tirely inconsequen tial, but it captures an intangible, indescrib able feeling, more precious than any thing I’ve ever known. This account is a tes tament to the love and grace I’ve learned to cultivate for my self. It’s a reminder of nights I spent choking down tears in the Quad dorm bathroom when I felt like I couldn’t recognize my self, and a reminder of nights I spent in the Harnwell rooftop lounge, laughing until my belly ached. But most importantly, it’s a reminder that I don’t need to chase down some arbitrary finish line in a never–end ing race—there's always time to be present in your own mind and start living for the moment before it becomes just a whisper of a memory.

For one year, this account has been, and continues to be, tangible proof that I’ve been doing things and learning how to swim up my own stream. And hey, maybe today can be the first day of your daily photo diary. Let me know how it’s going in a year from now, yeah? ❋

On late nights when I yearn for moments gone by, I lose myself in grid posts of sloping San Francisco hills and never–ending car rides to water polo tournaments. I’ve built an entire world of four–by–six images, and it’s entirely inconsequential, but it captures an intangible, indescribable feeling, more precious than anything I’ve ever known.

President of Penn Counterparts, A Cappella Council Chair, Vice President of Wharton Alliance, Wharton Cohort Leader, Kite and Key Society, member of the Wharton Ju nior–Senior Advisory Board

Hailing from less than an hour outside of Philly, Jack Franklin has certainly made the most of his four years at Penn, rising to leadership positions in both the A Cappel la Council and Counterparts A Cappella. For those wondering, the Penn a cappella scene is only a little bit like Pitch Perfect, and there are unfortunately no Riff–Offs. Aside from leading tours for Kite and Key, an ex perience he says is “always the highlight of my week,” Jack takes initiative within his school, leading in Wharton Cohorts and serving as the vice president of Wharton Al liance. Most characteristically, though, Jack makes sure to perfectly combine his cre ative and more academic passions, because what’s life without a little music?

Between music, marketing, and making Wharton feel like home, this senior certainly has his plate full.

BY ANJALI KISHORE

BY ANJALI KISHORE

Which of your communities has been most impactful on your time here at Penn?

Counterparts A Cappella. I joined with in the first weeks of my freshman year, and the group immediately became my

primary family on campus. It’s an amaz ing group of people and singers. We’ve gotten to have some amazing experienc es together. Aside from doing what we love—making music together—we also get to travel together. We were in London last

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

March, and in [Los Angeles] my fresh man year. Recently, we’ve gotten to open for John Legend, we just did the Phillies national anthem for the playoffs, and we presented Magill’s inauguration. I’m president this year, and it’s been probably

the most rewarding role I’ve ever had at Penn.

From there, I took over as chair of the A Cappella Council last April, so aside from Counterparts, I oversee 15 a cappel la groups on campus. That has also been, once again, hugely rewarding. I think a lot of the community within the arts was sort of lost over COVID–19, because we weren’t having the same level of interaction with each other [by] going to each other’s shows or having social events. That’s something I’ve really tried to bring back this year— just fostering that connection between groups. Obviously, [in] bringing back in–person performances, there was a huge amount of institutional knowledge loss. I was starting off as president for Coun terparts last year but had never been in a spring show before. Super weird times. But I feel like now that we’re at the oth er end of it, it’s been really cool to see all of the groups forming those connections once again, and through my role helping make all that happen.

The really cool thing about the arts com munity at Penn is that there truly is some thing for everyone. Every group does have such a unique identity, so it’s really cool to see all of those new groups interacting. It goes to show you the amazing diversi ty and talent that is within the Penn per forming arts community—not just within a cappella, but within all the subcommit tees of the Student Arts Council. It’s very rewarding for me to see all of that come together again after, during COVID–19, not being able to perform or see my friends perform. Seeing that comeback has been a huge part of my Penn experi ence and hugely rewarding for me.

How have you been able to foster a sense of community in your Wharton extracurriculars as well?

My involvements in Wharton are re ally all about community, the two main being Wharton Alliance and Cohorts. I basically serve as an Orientation Leader for new students, which has been super rewarding. I’ve done that since I was a first–year representative as a freshman, and now I’m an executive director as a se nior. Forming close connections with the

younger class has been super rewarding. I remember how much I relied on my co hort leaders. I was a mess my first semes ter, so it feels really good to give back in that way. It’s a hugely impactful program to, day one, step on campus and have a few upperclassmen who are really looking out for you. That always felt really special to me.

Wharton Alliance is Wharton’s LGBTQ+ affinity group that’s been growing im mensely. We got a record number of appli cations this semester, which is really cool. It’s really become, I think, one of the larg est queer spaces on campus, so it’s been super great for us to watch that grow, too.

I joined, once again, over COVID–19, when it was really hard to form those connec tions. But now I see all these new students joining, it’s become such a valuable com munity for them.

We’re putting on a queer formal, which is really exciting. In my role as VP, we put on the case competition every year where we have over 100 students sign up across the world, and we focused on Indigenous and sustainability issues. We actually won Wharton’s DEI award for it last year, which was really fun. So that’s been a hugely im pactful community for me, connecting with other queer students and bringing new students into that fold as well.

Especially within Wharton, I think ev eryone’s so focused on what’s coming next—what’s the next internship. It can be an incredibly competitive environment sometimes, but I feel like finding people from similar backgrounds to really con nect with on another level and forming those communities that really do perme ate that culture is something that I’ve al ways tried to do.

I think it’s funny because I went the tra ditional finance concentration route, but pairing it with marketing has been really fun. For me, I like to think I’m a creative person. I think pairing the quantitative and qualitative skills has always been something I’ve been super interested in. I’ve gotten to take classes with people who literally wrote the book on some of these

modern marketing techniques, which is really interesting. Aside from that, taking fun music classes and theater classes has been interesting as well.

I’ve realized that my interests don’t have to be mutually exclusive. I am inter ested in business, but I also love the arts. I have served as manager and president of my a cappella group, which has a ton of administrative and finance work on the back end. I think it’s been an interesting exercise in learning how to manage your friends, because it’s weird, right? It’s 17 of us, it’s a small group. Sometimes there are disagreements or tough decisions that have to be made, so I think being in roles like that, as business manager and pres ident, I’ve used some of the things I’ve learned in the classroom. It’s been inter esting to be able to fuse some of those pas sions in a lot of ways.

That’s been one of my main takeaways: that I can combine a lot of what I’ve learned across campus. Ultimately, I’d actually love to see myself working maybe in a business role in the arts industry and the entertainment industry in general. My end dream would be, you know, work ing for Spotify or something like that: do ing something cool where I get to work with artists and be creative. But, I am also interested in business and becoming a leader in that respect as well.

I’ve appreciated there’s been more of an emphasis on non–traditional career paths within Penn and Wharton lately, and I think that’s hugely important. I worked in banking this summer, and I personally didn’t like it. I’m not going back. A lot of people probably think I’m crazy for that. I’m trying something new, going out West [and] working in tech, and I’m excited for that. I think it’s going to be a new adven ture.

It’s not the classic Penn–to–New York pipeline, but I’ve been lucky to meet a lot of really interesting people. I think the best thing that Penn does in the class room is bring in amazing speakers, so I’ve gotten to make a lot of connections with them, some of whom gave me this advice to take a leap of faith. ❋

Last song you listened to?

“What Once Was” by Her’s.

No–skip album?

I’ve been really into the new album by Charlie Puth.

Which building at Penn are you and why?

I would say Houston Hall, because the best part is deep inside—Houston Market, but you’ve got to dig a little bit.

There are two types of people at Penn… People who go to food trucks, and people who don’t.

I am definitely a food truck person. Don Memo’s, Lyn’s, all that good stuff. You get to try to get some of the best food around, and it’s cheap. People should experiment more with some of the food trucks, be cause they’re really good.

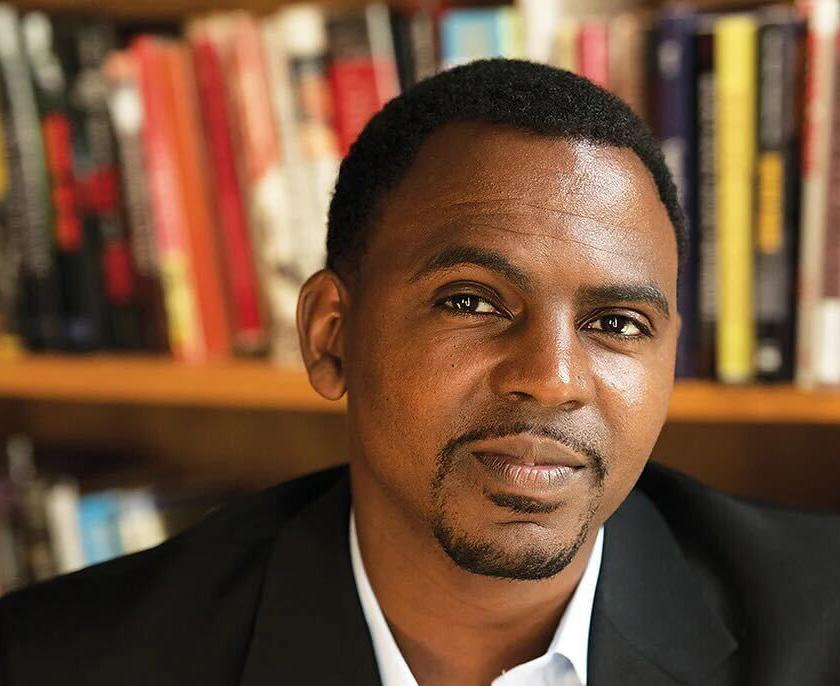

BY RIANE LUMERTo foster inclusive campus culture, universities need diversity at the student level, the faculty level, and in their administration. The most enriching environment possible is when students of all backgrounds feel represented by their role models. Nonetheless, Penn’s Political Science Department—yes, the Political Science De partment—has a stark lack of diversity: only one Black professor.

During the first week of the semester, I introduced myself to the faculty mem bers handing out free swag in the Rodin lobby. When I told Daniel Gillion that I’m majoring in political science, he imme diately welcomed me in and informed me that he’s a professor in the depart ment. “You can look me up. I’m the only Black professor on the website,” he said. Gillion became dead–set on where his education was taking him, but he also understood the barriers that would stand in the way—not just to getting there, but once he arrived.

From a young age, Gillion frequently dis cussed social injustices with his minority friends, many of whom resonated with his concerns. “And [then] I found out that you could literally get a whole Ph.D. in this? I mean, before going to graduate school, [I felt] I was halfway there, because I had these conversations” about racial and ethnic in equality, he says. Little did he know that working toward social justice would become his beacon in life.

During his initial foray into research at the graduate level, Gillion eagerly presented his interests about the efficacy of protests to his advisor, only to be told that the subject lacked value and “didn’t matter” because it didn’t connect to broader American political influ ence. His grandmother, who taught along side Coretta Scott King—civil rights leader, author, and wife of American hero Martin Luther King Jr.—reassured him in his pursuit to study protest activism. Thus, he delved into the under–researched topic, publishing books displaying the direct correlation be tween protests as a form of “democratic re sponsiveness” and governmental behavior.

Since then, Gillion has broadened his studies to racial and ethnic politics, polit ical institutions and behaviors, policy, and American elections. He published his first book in 2013, entitled The Political Power of Protest: Minority Activism and Shifts in Public Pol icy, followed by another during 2020’s tur bulent social landscape: The Loud Minority: Why Protests Matter in American Democracy. As people took to the streets to shake the world during the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, Gillion’s work highlight ed the consequential act of protesting as a vehicle for change through political pres sure. “Why is this the case? Why has this existed in America for so long?” he wonders on the question of racial tension and op pression. “I’m curious about the question, but finding the answer motivates me to pursue that question.”

Growing up as a Black man in America, Gillion doesn’t study this contentious work “behind a desk”; he experienced the theo ries he studied playing out firsthand. “I’ve experienced racial inequality throughout my life. That drive to find answers isn’t superficial, it’s real. Exploring solutions will help not only me, but help generations that come after me … my kids, and their kids, and so on,” he says.

Research and writing are both mentally challenging and taxing. When he first em barked on his political writing journey, Gil lion couldn’t shake away his fear of receiving negative feedback. But, as Gillion’s pieces have attracted more attention, he’s learned how to adjust his tone and style for his au dience. A New York Times podcast recently discussed his latest book, and news outlets often seek his opinions on pertinent social issues. However, over time, he’s grown a thicker skin, taking in both positive and neg ative criticism to rework his research into methods that are “sexy” and digestible to the American public. “I came out of graduate school with such a formal academic way of talking about research, as opposed to a lay man, colloquial tone. And that matters when you’re trying to present work that will reso nate with the overall nation,” he says.

source of debate in school. He’s even said, ‘Who’s this Daniel Gillion guy? It’s just you, Dad?’ Like, yes, I’m the only Daniel Gillion at the University of Pennsylvania. That’s when it becomes cool—not only to him, but to his friends,” Gillion says.

Gillion’s research is multifaceted and un deniably difficult. Working to push equali ty forward is challenging, and as racism in America becomes increasingly implicit, acts of discrimination are becoming progressively more difficult to tease out. Thus, it’s an ardu ous task to “engage in research that tries to inform individuals that there’s a problem in America along racial lines when they don’t see it,” he says. Race–neutral governmental rhet oric poses additional challenges to exploring social disparities. At the surface, these poli cies don’t explicitly reference racial or ethnic minority issues in society, but in actuality,

His latest book, The Loud Minority, is frequent ly mentioned during election cycles because it investigates how protest ideologies impact elections. “People often don’t connect how protests affect elections. So, my ability to draw those connections is pretty interesting to in dividuals nowadays,” he says. “I can show you the probability of a protest affecting elections based upon various characteristics [in both story and data patterns],” he says. In an effort to cater directly to his audience, Gillion speaks to those outside of the realm of academia, gather ing their opinions to frame his style.

A family man at heart, Gillion shares his studies with his young children, noting that if they don’t fall asleep, he knows he’s doing OK. “My oldest son has actually come across one of my papers and one of my books as a

still indirectly contribute to systemic racism. Omitting racial language doesn’t signify that a policy isn’t racially or ethnically motivated, as seen in cases like the war on drugs and social welfare. Though lacking racial language when implemented, both are are discriminatory in their origins and practice.

On the other hand, Gillion finds these un comfortable conversations with students to be the most energizing part of his job. Stu dents are young minds with “blank slates,” he says. “Individuals come in wanting to learn without being tainted by ideology and a long history of racism in America. They just want to be informed.” These students are more receptive to engaging with a multitude of perspectives and concepts. By presenting his students with ideas, he hopes that they

People often don’t connect how protests affect elections. So, my ability to draw those connections is pretty interesting to individuals nowadays. I can show you the probability of a protest affecting elections based upon various characteristics.

DANIEL GILLION

will “then pick up the mantle to further in vestigate it on their own.” Rather than per forming an act of persuasion, he stimulates students to think critically about American inequality in varied contexts.

“I love the back and forth with my stu dents. Sometimes the students push back, sometimes they’re cheering me on, almost like a cheer squad or choir,” Gillion says. At this particular point in his research efforts, he frequently turns to students to spur fresh ideas with a new sense of energy as young students see the world anew in ways that he may have missed. One way that Gillion deepens his research is by surveying stu dents about whether or not they find protest efforts valuable. Depending on the students’ responses, he may shift the focus of his next paper. Sometimes students question if pro tests truly do lead to policy changes and indi vidual impacts, prompting Gillion to initiate new investigations in these areas, beyond electoral influence. “There’s a real joy in sit ting down and talking to students about my research,” he says, because it enables him to approach racial and ethnic inequality ideol ogy through different avenues.

In his work, Gillion maintains his golden rule of “continuance as opposed to a goal of finality.” Confronting marginalization and social disproportionality is a ceaseless pro cess—a never–ending story. “It’s almost like whack–a–mole, where you talk about one par ticular topic in one particular problem area and another one pops up,” he says. “My work is never done.” He adds, “We can move from the colloquial discussions at the water cooler and engage in very technical discussions of how [injustices] take place,” an objective that Gillion exhibits in his daily efforts.

Although Gillion is the only Black profes sor in the Political Science Department at Penn, his innovative work is crucial in nar rowing pervasive social inequities in Amer ica. As an institution that is on a “quest for eminence” through diversity, equity, and in clusion efforts, Penn should prioritize DEI in terms of its faculty as well, and across mul tiple disciplines at that. Gillion’s exceptional work within and outside of the classroom ex emplifies that necessity for representation.

To students looking to explore political research, Gillion urges, “Go big or go home. Take a deep dive.” The world needs more risk–takers. k

My work is never done. We can move from the colloquial discussions at the water cooler and engage in very technical discussions of how injustices take place.

DANIEL GILLION

Wei-An Jin

BY KATIE BARTLETT

Wei-An Jin

BY KATIE BARTLETT

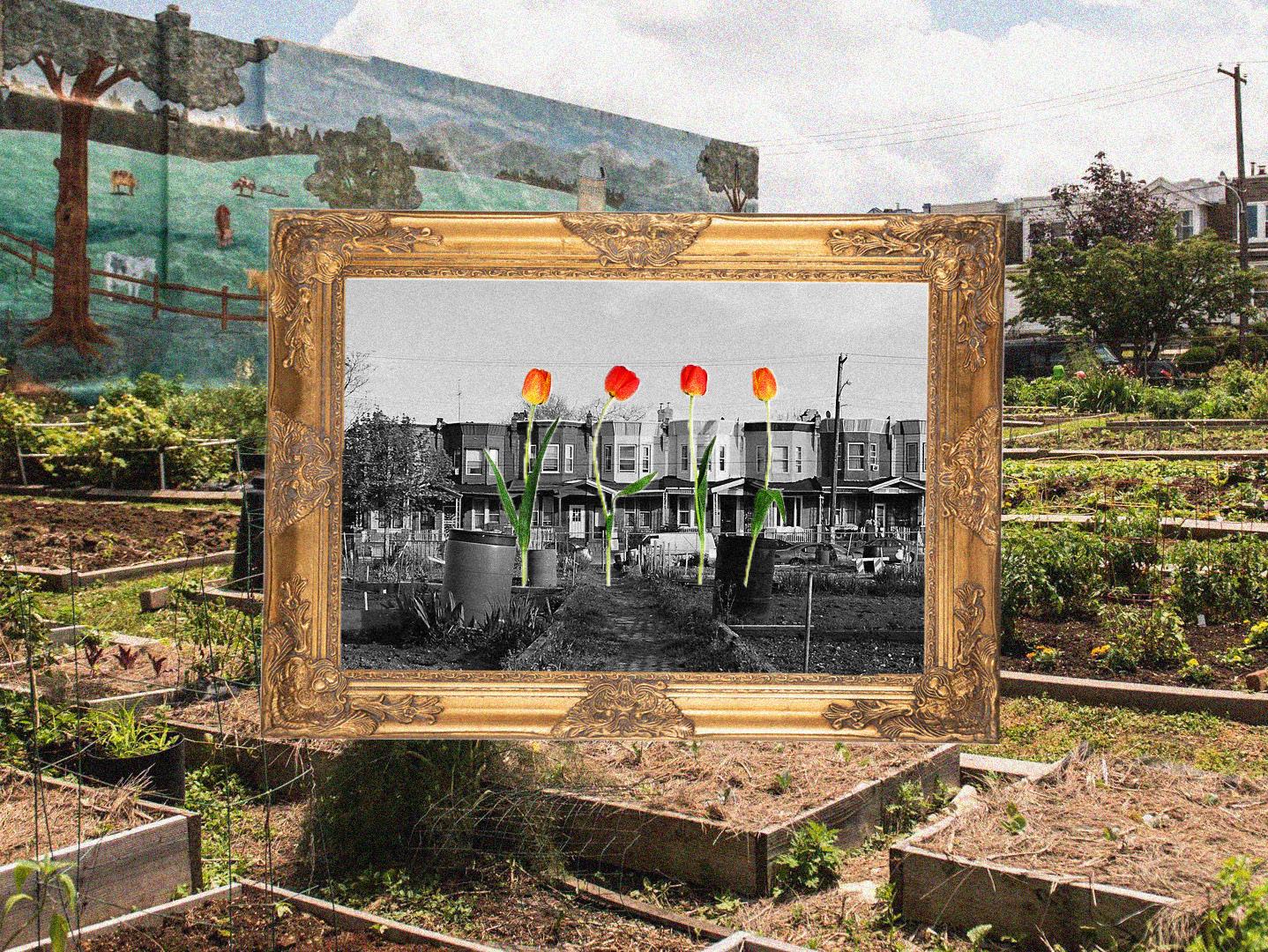

A look at the past, present, and future of Philadelphia’s community gardens

Iris Brown, a founder of the gardens at Norris Square Neighborhood Project (NSNP), sits at a picnic table against the backdrop of a brightly colored pergola in scribed with the word “hope” in three lan guages as she shares the story of how the Kensington–area urban garden came to be.

“We had nothing in this community until we started gardening,” she says.

A native of Puerto Rico, Brown moved to Norris Square, a neighborhood in West Kensington, in 1970. During her early years, she remembers Norris Square to have been a vibrant and close–knit community, where four generations of Puerto Rican residents lived. She could walk to any local business, be it the bank or the corner store, and know the owners by name.

Associate professor of city planning and urban studies Domenic Vitiello explained that Kensington was once the “textile cap ital” of the United States. Just a few blocks away from Norris Square, Stetson Hats had employed 5,000 people at the beginning of the mid–20th century.

Yet, by the mid–1970s, the loss of manu facturing jobs associated with ongoing dein dustrialization, combined with the arrival of drugs, hollowed out the neighborhood’s institutions. Brown remembers this period as “a nightmare.” Drugs were sold on every corner, sirens and gunshots pierced the air, people died of overdoses on the streets, and houses burnt to the ground, turning the block into a shell of what it once was.

In response, many of her neighbors moved to other parts of the United States or back to Puerto Rico, Brown explains. The banks, hos pital, and other community spaces closed. As the neighborhood emptied out, vacant lots emerged that soon became sites of open–air drug markets.

In the 1980s, an anti–drug raid incarcerat ed about 60 members of the community who were involved with the drug trade. Brown and others had hoped this would improve the neighborhood, but their removal ulti mately had the opposite effect.

The aftermath of the drug raid was “a different kind of suffering,” according to Brown. It ripped families apart, leaving some children without caregivers. There were no social workers or other forms of support of fered to families impacted by the raid.

“Our community never had much, but

what little we had was gone,” Brown says.

In response to the community’s struggles, Brown and a group of neighborhood wom en called Grupos Motivos committed them selves to providing a much–needed support system for the community. They joined forc es with Natalie Kempner, a local elementary school teacher who founded NSNP as a na ture center for children in 1973.

One such garden, Las Parcelas, features a traditional Puerto Rican farmhouse, while El Batey includes a Taíno hut—pro viding opportunities for residents to en gage with different elements of Puerto Rican history. Murals portraying Puer to Rico’s past and the women of Grupos Motivos overlook the students as they learn together.

One of their first priorities was figuring out how to transform the vacant lots scattered throughout the Norris Square neighborhood into spaces that could uplift all of its inhabitants.

“What can you do in an empty lot?” Brown asks. “A garden is the only option.”

Over 45 years later, NSNP offers local youth a safe space to develop their leadership skills, build relationships, explore culture, learn about urban agriculture, and express their creativity through art.

It’s this dedication to community enrich ment that is at the heart of NSNP’s mission.

Approximately 40 eighth grade and high school students currently participate in an after–school program “designed to keep them off the streets, be fun, and teach 21st–century skills,” says NSNP Director Teresa Elliott. The program offers technology, arts, and gardening education as well as home work support. Meanwhile, outdoor kitchens provide a space for cooking demonstrations. Students also participate in running a week ly farmers market, selling produce to the Norris Square community.

Themed gardens also celebrate Puerto Rican culture and instill heritage pride, paying homage to the community’s roots.

Brown emphasizes that the inspiration for the hut came from witnessing frequent fights over race among Puerto Rican youth. She views it as a space to instill pride and “explore the beauty that came from Africa.”

Several decades after the founding of NSNP and two and a half miles west, Tommy Joshua Caison, the founder and executive di rector of the North Philadelphia Peace Park, was facing a similar predicament. Debating how to fill the vacant lots surrounding the Norman Blumberg Apartments, a 499–unit housing project in the Sharswood area of North Philadelphia, Caison too believed that installing a garden would best serve the in terests of the local community.

Caison’s background as a neighborhood resident, longtime activist, and educator allowed him to bring people of many back grounds together to make his vision a reality. In 2012, the North Philly Peace Park opened its doors to the public.

“We believe ourselves to be introducing an alternative development model,” Caison says. “We felt that it was something that the whole city and even the country could learn from and benefit from.”

Sharswood was historically a hub for African American arts and culture, Caison notes. Pearl Bailey, Duke Ellington, and the Nichols Broth ers performed at the Pearl Theater, a local jazz and dance venue that closed in 1971. Famous activists—including Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Cecil B. Moore—worked, spoke, and marched the district’s streets during the Civil Rights Movement. This legacy continues: Today, Sharswood is still 76.4 percent Black.

As well–paying job opportunities declined in North Philadelphia, crime and drug–use rates rose. Today, about 56 percent of res idents live below the poverty line, making Sharswood one of the poorest communities in the city. The North Philly Peace Park, Ciason highlights, serves to uplift and empower this population that has traditionally been under served and overlooked by local government.

“I started the Peace Park as both a stance against our current conditions and a contin uation of the African American quest for de mocracy here in America,” he says.

Caison explains that the park serves as an extension of African American attempts to revolutionize the Constitution and expand the notion of citizenship beyond a white male property owner. He draws inspiration from his early experiences in the outdoors, including visits to his uncle’s farm in North Carolina and explorations of abandoned warehouses in Fairmount Park.

“Just like somebody would use paint or clay, I view soil as a medium for human rights, hu man creativity and community,” he says.

Similarly to NSNP, the Peace Park has also made youth engagement a pillar of its mission.

The Peace Park seeks to encourage Black pride and an understanding of Black history. Cutouts displayed in and around the garden pay homage to Black activists, artists, and teachers.

This pride extends to the park’s afrofutur ist design. Afrofuturism is a cultural aesthet ic that fuses science–fiction, history, and fan tasy to examine the Black experience.

Caison explains that afrofuturism allows African Amercians to “reconnect to a time before enslavement or colonialism and chal lenge the anti–Black status quo.” Peace Park creators utilize afrofuturism to “imagine without limits,” he says.

The afrofuturist lens has been combined with sustainable building practices to create a community–designed school house, which is scheduled to be complete in fall 2023. The school house will support a “dynamic, cul turally relevant” STEM education to further what youth are already learning through their involvement with the park’s gardens.

“We’re looking to produce innovators and humanitarians who can go on to solve some of the problems in the world,” he says.

Skip Wiener, a native of West Philadel phia’s Haddington neighborhood, returned to the community to found Urban Tree Con nection (UTC) in 1989. Decades later, UTC has transformed 29 vacant lots, totaling

more than 86,000 square feet of land, into spaces for communal growing and gather ing, sustainable food production and distri bution, and multigenerational health and wellness education.

After receiving a master’s degree in land scape architecture from Penn, Wiener worked as a landscape architect at John Rahenkamp Consultants. When he lost his job, he knew that he wanted to continue his vocation and saw an opportunity to use his skills to enrich the neighborhood that he grew up in.

That same year, the William Penn Foundation had taken on a project to provide after–school enrichment for students who live in high crime neighborhoods, including Haddington. Wiener got involved with the effort, engaging students in neighborhood gardening projects.

“I met some of the brightest, most competent kids living in Haddington,” Wiener says. “But their days were lacking structure. Our programs became a source of stimulation for them.”

The students brought Wiener to an aban doned lot that had become a drug hotspot. The group began to garden on it, covering the area in wood chips and plants. Wiener described the process as “very organic,” with no initial long term plan.

Wiener pointed to the Haddington block captains—residents who opt to lead cleaning and community efforts—as essential contrib utors to the growth of UTC. The block cap tains suggested neighborhood lots that could be improved through UTC, and they worked together to redirect kids involved with the drug trade and violence.

“While some people looked at UTC as a funky garden program, I saw it as a community de velopment program,” Wiener says. “You could hire for and fund the technology of farming at any level, but you could not deal with how kids were spinning out of control, guns and drugs without a community dialogue.”

At UTC, the development of youth education al programming has created a space for commu nity dialogue and relationship–building.

Monthly workshops teach gardening skills and act as a space for discussion about the neighborhood. Conversations are “often rooted in food, land, and environmental justice in a way that speaks to people’s dai ly lives,” according to Noelle Warford, who assumed the role of UTC executive director after Wiener retired in 2016.

Like the North Philly Peace Park, UTC’s programming also hopes to address many of the major concerns facing residents—includ ing food insecurity.

In 2009, Haddington residents expressed a desire to repurpose a vacant lot being uti lized as a chop shop for stolen cars to create a community farm that would generate af fordable, chemical–free, and Haddington–grown food available to anyone in need. A lawyer recommended Wiener go to court

the food grown on the land was donated to community organizations and food banks. The rest was sold by residents at farm stands throughout the neighborhood at af fordable prices.

When the COVID–19 pandemic hit, UTC changed their model to make all farmed pro duce free. In collaboration with city block captains, UTC began a door–to–door delivery service—a practice that “aligns with their goal of uplifting community leadership,” Warford says. Through a collaborative process, UTC has provided support to the community and has innovated in the face of new challenges.

While the work of these community leaders has brought much–needed resources to under served neighborhoods, many of their land rec lamation efforts have been met with pushback.

In March 2022, renovations to the UTC memorial garden in honor of gun violence victims were completed—providing resi dents with a well–lit walking trail in line with their desires. A month later, UTC got word that the garden—along with 30 to 40 other lots—was slated for redevelopment.

IRIS BROWNWarford learned that the redevelopment was part of the city’s Turn the Key initia tive, which is intended to support affordable housing. The $400 million plan will build up to 1,000 houses on publicly owned land. The monthly mortgage will be less than the me dian monthly for a two–bedroom apartment, and the Neighborhood Preservation Initia tive will also be offering up to $75,000 in soft loans on the houses for first–time buyers.

and share a video describing his plans for the land and to request ownership of it.

“The judge stood up ten minutes into the video and said, ‘I don’t want to hear any more, it’s yours. Take the piece of land,’” Wiener says.

Weiner received superfund money to re move contamination from the land and to prepare it for growing. He had no agricul tural background, but soon found support among the community’s older members.

“All these Black 70– and 80–year–olds came out of their houses and said, ‘You’re doing it wrong, this is the way to do it,’” Wiener says. “All of a sudden, I had tapped into a southern Black farming culture that was dormant.”

In the farm’s early years, a portion of

Yet, Haddington residents were skeptical of the plan. They weren’t told about the de velopment, nor informed about the cost of the finished housing, making them feel like it wasn’t being carried out in their best in terests. UTC gathered over 100 signatures of neighbors who wanted to save the gardens.

Through the petition and support of other city organizations, UTC was able to save half of their land. Still, the other half will be devel oped in line with the Turn the Key initiative.

“It’s very frustrating how we often get pit ted against affordable housing,” Warford says. “The roots of housing and food insecu rity are the same.”

The community’s concerns are not un founded. While Turn the Key’s maximum sale price of $280,000 may be affordable

We cannot sit and wait for somebody to give us things because they’re often the wrong things.

when considering the median income of Philadelphia County as a whole ($105,400 for a family of four), the average annual house hold income in Haddington is $32,000—leav ing the new development well out of reach for many locals.

As UTC continues to fight to preserve the other half of their land, Warford emphasiz es that the issue has sparked conversation in the neighborhood about other forms of de velopment that are occurring.

Although the mission of the North Philly Peace Park is now supported by the city, Caison explains that this backing was not won easily.

In 2014, after being alerted by a neighbor,

Caison attended a Philadelphia Housing Au thority (PHA) meeting at Miller Memorial Baptist Church—just a few blocks away from the original Peace Park site—where he dis covered lawyers and developers in conver sation. Caison tried to introduce himself and speak to the value of the park and to push for dialogue about development. Ultimately, he says he was ignored.

Caison and others who supported the Peace Park began attending these meetings regular ly, transforming them into a “lively debate.”

“We stopped being farmers and became revo lutionaries,” he says.

The PHA eventually recognized the Peace

Park’s resistance efforts. When the PHA sur veyed the Peace Park’s land, they reached an agreement to consult the park on major decisions.

Yet, soon after, Caison received an anony mous email from a PHA employee warning him that PHA intended to run stabilization tests on the property—a clear violation of the agreement. Caison reached out to PHA to request reconsid eration and received no response. Instead, he awoke one morning in winter 2014 to news that the PHA had arrived to drill.

Caison and others arrived at the park to protest, and the PHA retreated. He says that the encounter “electrified the neighbor

Just like somebody would use paint or clay, I view soil as a medium for human rights, human creativity and community.Katie Bartlett

hood,” attracting the mainstream media and city hall in the process.

In the spring of 2015, the PHA fenced in the park. Caison recalls this as “extremely traumatizing.” Neighborhood kids were in tears, unable to understand what was hap pening to their park.

Caison mobilized a resistance and took the fence down. In response, one promi nent city politician personally threatened to arrest him for trespassing and destroying city property.

“I was like an outlaw,” he says.

This period of resistance and altercations with the PHA lasted for over six months. Eventually, Caison and other Peace Park leaders decided to engage in a land trade, swapping the property for new land with guaranteed security. The Peace Park moved to their current location on 22nd and Jef ferson streets, around the corner from the original location. They lost all that they had built in its first three years, including gar dens and an earthship.

“It was very difficult to walk away from all that we had achieved and invested in the orig inal park, but revolution is a process,” Caison says. “Sometimes in order to take two steps forward, you have to take one step back.”

Despite some continued challenges, the PHA and the Peace Park have forged a working relationship. Caison and the Peace Park team are in the process of expanding the park over a full city block utilizing an afrofuturist lens.

“I hope that the Peace Park will stay true to its principles while also continuing to outdo itself,” he says. “And I hope the mission will grow across Philadelphia and to new cities.”

The people who tend Philadelphia’s ur ban gardens are united by a willingness to take initiative and learn as they go. Like the neighborhoods in which they flourish, their progress is not always linear and the hur dles they face sometimes come from people who purport to be allies in the struggle to better their communities.

“We cannot sit and wait for somebody to give us things because they’re often the wrong things,” Brown emphasizes.

It’s unclear what the future has in store for Philadelphia’s community gardens. As property values rise citywide and neighbor hoods struggle to hold onto their histories amid ongoing gentrification, communi ty initiatives like these gardens remain a source of collective power.k

A cannabis advocate’s take on what she expects from the new administration SARA HEIM

Many human rights were on the bal lot this election season, including, but not limited to, Pennsylvanians’ legal right to smoke some weed. As politi cians battled for the majority vote, employ ing tactics from accusatory advertisements to “Darties for Democracy,” the issue of mar ijuana legalization was overshadowed by the salient issues of reproductive rights and high crime rates. But as the new elects are soon to be ushered into office, the future of marijua na legislation hangs in the balance. Cannabis remains an illegal drug across the state of Pennsylvania, resulting in 20,200 arrests for marijuana possession in 2020, indicating that the enforcement of prohibi tion persisted even in midst of the COVID–19 pandemic. Arrests continue to be dispro portionately concentrated among Black Pennsylvanians, who represent 32 percent of the arrests yet comprise only 12 percent of the state’s population. On the city level, marijuana has been decriminalized in Phil adelphia since 2014, meaning that residents will not be prosecuted for personal canna bis use, instead receiving a fine, citation, or community service requirement through civil proceedings. Philadelphia District Attor ney Larry Krasner has elected not to pursue small–scale marijuana possession charges in civil court, resulting in a 78 percent decline in marijuana arrests in Philadelphia between 2013 and 2014. Even with relatively low arrest numbers, Black Philadelphians are detained disproportionately, making up 44 percent of the city’s population but 76 percent of its marijuana arrests. Decriminalization isn’t enough to prevent the use of police force and incarceration, which directly harms Black and brown communities.

Earlier this year, Gov. Tom Wolf and Lt. Gov. John Fetterman began working to remedy this disparity through the Pennsylvania Marijuna Pardon Project, which offers a one–step on line application to be officially pardoned for a non–violent marijuana offense. The project followed Wolf and Fetterman’s tour of all 67 Pennsylvania counties, where they listened to constituents’ perspectives on cannabis issues.

While small gains have been made in Har risburg toward expanding cannabis access, marijuana activist and political organizer

Tsehaitu Abye says it’s imperative that pol iticians communicate with cannabis advo cates to better inform cannabis legislation. Abye commends that midterm elects Josh Shapiro and Fetterman have “been actively having those discussions and participating in the work” to understand what the cannabis community needs from its political repre sentatives. The stigmatization of prohibition makes users feel they can’t talk to their elect ed officials about marijuana use or use po litical spaces to advocate for cannabis access and legalization. Abye emphasizes that “the election can help you with your relationship with cannabis. And your access to cannabis. Because it’s access to health care.”

In Pennsylvania, cannabis has been rec ognized as a health care tool since the state passed its Medical Marijuana Act in 2016. The legislation began Pennsylvania’s widely suc cessful medical marijuana program, which serves nearly 600,000 Pennsylvanians, pro viding them with care for 23 qualifying med ical conditions ranging from autism to sickle cell anemia. In the past, Harrisburg has rec ognized the value of cannabis for Pennsylva nia residents, and the incoming administra tion must maintain this understanding as it seeks to expand access to marijuana.

Abye is encouraged by the past work of Sha piro and Fetterman in engaging with canna bis advocates, but also expects them to “make sure we have different stakeholders that rep resent the community of Pennsylvania, in particular considering those who are Black and have been specifically impacted by the war on drugs.” While legalization remains the ultimate goal on the horizon, it’s important to Abye that the cannabis community heals from the damage that’s been inflicted on them by criminalizing thousands of people. Not only does this criminalization forcibly remove individuals from their communities, but also stigmatizes them as criminals for the rest of their lives. The “amount of organized power, organized money, and organized peo ple” gives politicians the power to speak for those who have been shamed into silence by prohibition.

Politicians must work toward destigma tizing cannabis use as much as expanding access and fighting for legalization, as stigma

hinders users from advocating for themselves and developing a strong community.

Senator–elect Fetterman dedicates a page of his website to his political goals surround ing marijuana access; the page itself states Fetterman’s ultimate goal for cannabis pol icy. He expresses concern that “people who are using this plant legally in their home may still be denied federal employment,” pointing to the government’s systemic discrimination against marijuana users. As senator, Fetter man will be able to advocate for cannabis access at the federal level, working to change the drug’s status as a Schedule I substance and expand access across the country. On the campaign trail, Senate candidate Mehmet Oz took to Twitter to criticize his competitor’s promotion of weed legalization, publishing a crude video of a bong emerging from Fetter man’s head.

Fetterman also seeks to “prevent the mo nopolization of this new industry,” as does Abye through her marketing company, Black Dragon Breakfast Club. Abye limits her cli ents to BIPOC women interested in canna bis entrepreneurship in an effort to redefine how people of color relate to cannabis, transi tioning from a narrative of criminality to one of ownership and agency. The stated mission of BLBC is to change the perception of canna bis and “take control of the hemp and canna bis industry.” Large corporations are already beginning to overtake the state’s budding weed industry, with one company establish ing 21 medical marijuana dispensaries across the state. As is the pattern across large corpo rations, the leaders of these companies tend to be white men, excluding the demographic that Abye works to uplift.

Despite the will for legalization from the state’s governor– and senator–elects, many still doubt that legalization is in the near fu ture for Pennsylvania. Although six out of ten Pennsylvania voters support marijuana legal ization, the issue still lacks bipartisan support in the state legislature, as some Republican legislators continue to oppose the bill. On the other hand, the election of Shapiro, who has publicly stated his goal of legalizing marijua na and rectifying the harms inflicted by pro hibition laws, is promising for the future of cannabis policy. ❋

CO–OP Restaurant & Bar is nestled on South 33rd Street in Univer sity City, catering to residents and visitors alike, offering them a re fined yet unpretentious dining experi ence. The restaurant is just as chic as its cafe space and hotel aptly named “The Study.” Recently, CO–OP held a preview event celebrating the debut of their new restaurant concept, featuring an all–new head chef and restaurant staff and a focus on locally sourced ingredi ents, Mid–Atlantic cuisine, and regional cooking practices complimented with a modern twist. This new direction is in dicative of CO–OP’s intention to bring more upscale options to the University City area, particularly to those visiting or attending local universities such as Penn.

CO–OP is part of Study Hotels, a hos pitality brand that’s opened locations near a number of elite college campus es, including Yale University, the Uni versity of Chicago, and an upcoming location in Baltimore at John Hopkins University. Since its University City lo cation opened in 2017 it has been named one of the best hotels in Philadelphia by

publications Curbed and Condé Nast Trav eler , as well as highlighted as a standout among hotels in college towns by The New York Times and USA Today .

With a new menu inspired by the fla vors and cultures of the Mid–Atlantic, it’s clear that CO–OP Restaurant & Bar wants to invite guests to taste the unique in gredients available in the region during their stay at The Study. CO–OP’s menu renovation is “inspired by the hardwork ing fishing and farming communities which immigrated to the East Coast— communities which valued quality, hos pitality, and sharing,” according to a press release. Philadelphia has histori cally been a popular city for immigrants, which in turn has shaped the city’s cu linary diversity. Utilizing the multitude of ingredients and cooking techniques native to the region, CO–OP’s new menu is meant to reflect the many flavors of Mid–Atlantic’s culinary scene.

CO–OP’s new executive chef, Kyle Berman, comes from a background of high–end eateries including the Miche lin–starred Alinea in Chicago. Under Berman’s direction, CO–OP said they’re “look[ing] forward to welcoming [their]

neighbors—students and faculty of the surrounding universities, residents of University City, West Philadelphia, and beyond—to experience the history of Philadelphia and the Mid–Atlantic re gion through our new food and bever age menus.”

On the inside, CO–OP has an upscale atmosphere, perfect for a special occa sion meal with friends and family. There is an abundance of seating options, from the bar to smaller tables, but also ample space to stand, making it a great setting for an event like a cocktail hour. I visit ed at night, but I could imagine that the restaurant would be absolutely gorgeous during the day, with the large windows letting in plenty of light.

Over the course of my night, I began to realize that CO–OP excels in the presen tation of food. Our first course is a pump kin soup, served inside a hollowed–out pumpkin. The innovative presentation was actually unplanned; I’m informed later in the night that, upon realizing they didn’t have enough small bowls for the dinner, the chef decided to hollow out some pumpkins they’d bought for restaurant decor. The soup itself is one

of the highlights of the night; its texture is delightfully creamy with the cultured cream adding a tangy flavor to the other wise sweet pumpkin.

Another memorable dish is the lingui ni and clams. It was the perfect mixture of savory, coming from the clams and bottarga, and zestiness from the light sauce. I also delight in the beef short rib dish, which is so tender that I don’t even need a knife to cut through it. The dish comes with zucchini and grits that bal ance out the slight sweetness of the short rib. With each course, I’m impressed by the choice of fresh ingredients and the blend of seasonal flavors, each offering a unique twist on classic cuisine.

I happily recommend CO–OP to any one looking for a classy restaurant to host a birthday dinner or to take their parents to if they stop by campus. While I’m lucky enough to have tried so many wonderful dishes, I’d absolutely return to try more of the menu.

TL;DR: Sit down at CO–OP for a de licious meal—and an abundance of drink options—and lavish in the re fined atmosphere and creative menu options. k

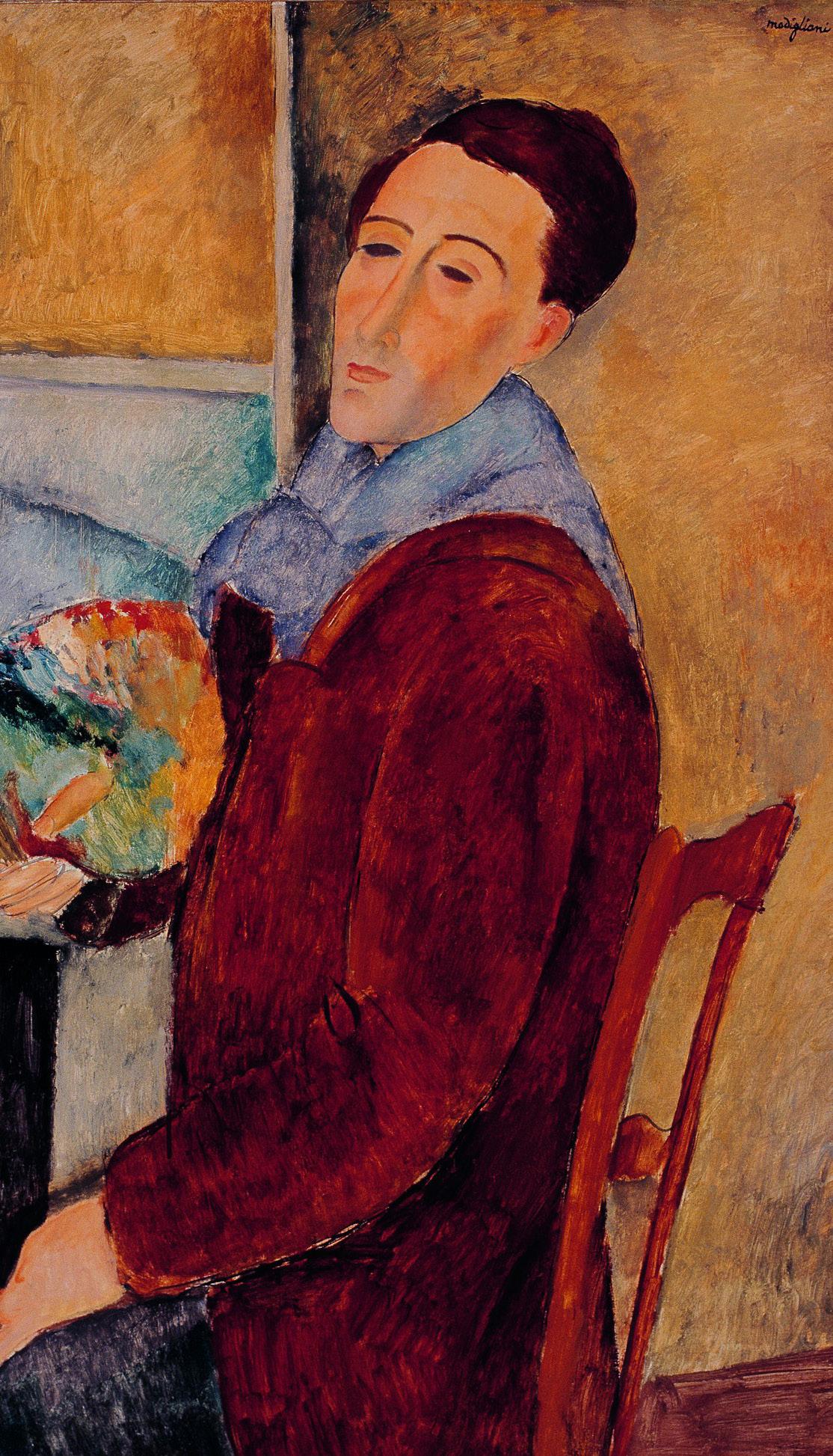

In Amedeo Modigliani’s case, it was destiny. Painting was the only path for the winsome, sick ly boy whose mother once wrote, “He behaves like a spoiled child, but he does not lack intelli gence. We shall have to wait and see what is inside this chrysalis. Perhaps an artist?”

That he became one of the most recogniz able artists of the 20th century isn’t shocking. Now, just over a hundred years after Modigli ani’s death, the Barnes Foundation unites over 50 works for a retrospective without precedent in scale, focus, and ambition.

Spearheaded by Deputy Director for Col lections and Exhibitions Nancy Ireson, Modigliani Up Close comes on the heels of the Tate Modern’s major 2017 retrospective. In contrast to this earlier show, the Barnes’ exhibition exceeds Ceroni’s catalogue rai sonné, the most definitive compilation of Modigliani’s works. Four previously unlist ed paintings are on display here in the third gallery. Sweeping in scale, the show unites works from locations as varied as Jerusalem, Dallas, Turin, and Paris.

stances changed drastically, such as when he moved from Paris to the Mediterranean, he continued to rely on his trusty dealer for supplies.

Watching the continuity between these works unfold is uniquely rewarding, while the various historical tidbits revealed throughout the exhibit lend us a new per spective on their creator. We learn, for exam ple, that the stone for many of Modigliani’s sculptures was likely acquired illicitly, giving some credence to the myth of Modigliani the maverick. (The legend endures of the artist as an inveterate womanizer, alcoholic, and drug addict.)

Though much is gained by this focus on the works’ physical characteristics, the show falters slightly when it comes to that other, inner substratum: Modigliani’s private uni verse. In its understandable reluctance to dredge through Modigliani’s many muddled influences, the Barnes merely grazes the art ist’s debts to history.

BY IRMA KISSThe decision to display these objects to gether is hard–won, resulting from years of rigorous technical analysis. In preparation for the exhibition, an international cohort of scholars, curators, and conservationists per formed X–radiography of the works. Pictures were then submitted to the Thread Count Automation Project. The process uncovered new connections between canvases from dif ferent stages of Modigliani’s career; we now have reason to believe that works made in Paris and the South of France were literally cut from the same cloth.

This diligence makes sense in light of Modigliani’s exhibition history. Perhaps more than any other celebrated artist, forg eries of his work abound. When fakes were discovered at a 2017 exhibition in Genoa, It aly, the displaying gallery was shuttered and the sponsoring foundation dissolved. Hence, precision is essential.

Yet, technical analysis always runs the risk of estranging the viewer from the work. What do fiber counts and canvas measurements have to do with why a painting compels us?

Mercifully, the Barnes’ efforts are subtle, purposeful, and targeted. They have the ef fect not just of bringing new works to the viewer’s attention, but of offering precious insight into Modigliani’s craft. The exhibi tion reveals that Modigliani often reused existing paintings, adding new layers onto previous artists’ works. Even as his circum

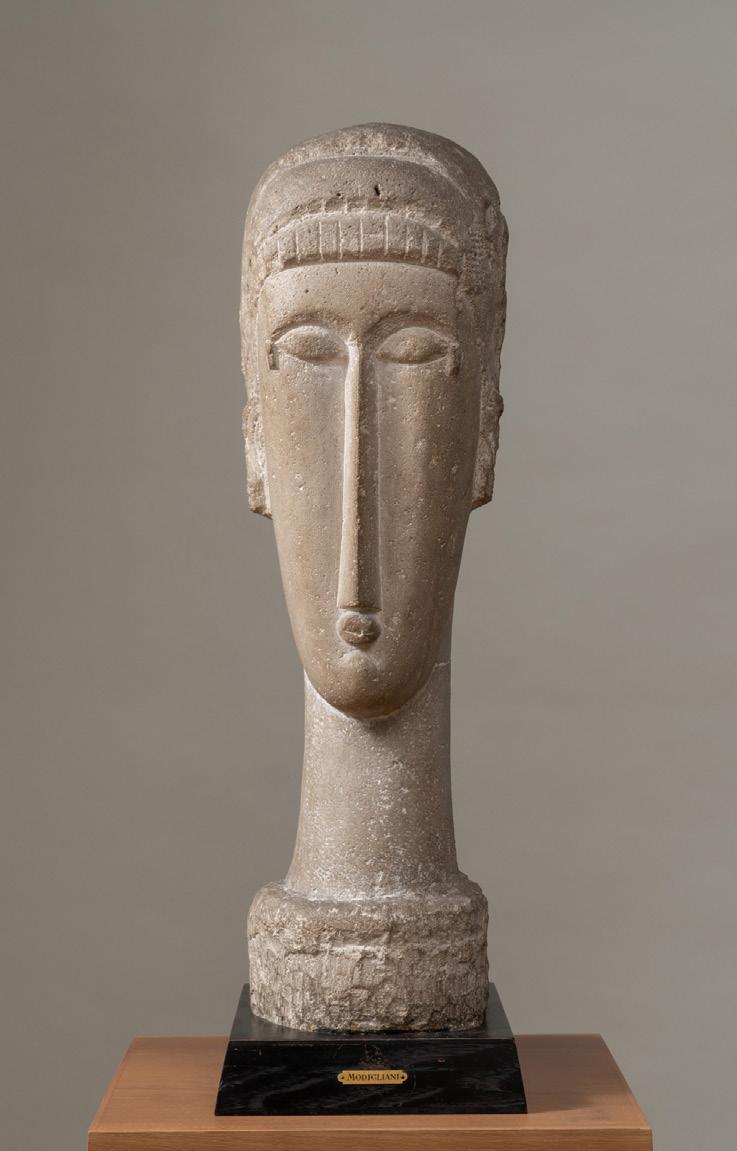

Modigliani was the self–appointed inheri tor of a long tradition. It doesn’t take a keen observer to recognize his African influenc es. There are many records of his visits to the Musée d’ethnographie de Genève near the turn of the century—consistent with the budding avant–garde interest in so–called “primitive” art hailing from Africa, Oceania, and East Asia. These frequent jaunts left their mark: The planar, elongated faces common to so many of his pieces are an instant tell.

At the Barnes, this visual affinity is appar ent in the limestone Head of a Woman (1912). One can argue that the drooping arch of her nose, rosebud mouth, and narrow face were all cribbed from equatorial Africa.

But in its sweeping overview of Modigli ani’s creative methods, the Barnes treats these knotty contingencies—or debts, to speak frankly—like small potatoes. The omis sion smarts somewhat in light of the recent ly closed Isaac Julien show. Any institution that mans the gates of the so–called canon has special responsibility. The stakes are too great to be ignored when admission to the club can be life–changing. Occlusion, espe cially in the case of historically overlooked and exploited creators, is often fatal.

That said, the presentation of these sculp tures at the Barnes is both novel and satisfy ing. We learn that trace amounts of wax were discovered on the objects, and land on this charming image: Modigliani likely used the sculptures as candle stands. A fitting use for the medium, stone is firm and definite. It

can be held and played with in a way that a painting can’t. And this makes irony possible in sculpture, a special affordance of the me dium.

Modigliani made the peculiar choice to cast that irony aside along with the sculptural mode. When he reverted to painting by the mid–1910s, he also committed to an unwav ering formal clarity. Unlike the limestone busts, which lend themselves to tactile play, these later works were destined to be looked at—and only that. Their characteristic flat ness, frontal compositions, and subtle shifts in color invite a detached viewing position. And though Modigliani’s paintings exist uniquely qua paintings, there are little glyph ic nods here and there. This is the case in Madam Pompadour, which bears a slight verbal inscription.

This shift in his working methods took place for health reasons (painting is less la bor–intensive than sculpture), if Paul Alex andre’s account is to be trusted. But perhaps there’s another reason, that absolutes are vi tal for the artist who lived in extremes. And in Modigliani’s world, illness is fatal, love is redemptive, and poverty keels over into op ulence. Moreover, the heights and depths of this biographical drama have a solid founda tion.

Much has been said already about Modigli ani’s character—handsome, volatile, and highly gifted, the artist labored under a persona of fated creative agony. To many, his prophetic, exceptional status was visible even in his perfect features: Long, straight nose; high cheekbones; dark, haunting eyes. Modigliani was the rare artist who both ex uded beauty and extracted it.

Somehow, I’ve never felt alienated by Modigliani’s women the way I have with oth er artists of his period. This despite the fact that his female subject is bounded by a sexual halo, and is so often contorted into offering herself. In Reclining Nude (1917), she archly peels away on a mattress. Or she caresses her own decolletage, as in Woman with Red Hair (1917). Maybe she simply bares her chest, as in Nude with a Hat (1908). And yet the artist can’t fix her—she remains impenetrable.

Among women, this dynamic is common wisdom. Cynical as it sounds, to love and be

loved by men is to draw away constant ly, to retreat into the imagination. We make the choice, day after day, to perform a pecu liar alchemy, turning pity and boredom into affection. And somehow we’re happy in love.

Often, we find ourselves enjoying an em brace not for the texture of the lived–in moment, but for the mere fact of being em braced. Because for all the progress of the last century, few would argue that we’ve achieved true male–female sexual parity. There’s still a desiring subject and a desired object, and what this lack of reciprocity entails for wom en is the following routine, learned by rote: I can’t count the times I’ve heard a girl friend, after a glass or two, stare at the ceil ing and sigh, Oh, but he’s so boring/unimpressive/ mediocre. But we go on. What always redeems this or that bum is his power to discern. In the right circumstances, anyone can be led to behold the more polished dimensions of our character. And, indeed, our beauty.

Maybe Modigliani saw this, maybe not— but it’s there in the gravid blankness of his models. He’s the rare male artist who lets women look at themselves without any at tempt at self–stroking artifice. At the Barnes, this comes to bear in the glorious, ethereal Jeanne Hébuterne (1919). The picture lets us

finally behold ourselves as we are: inscruta ble. There’s a total absence of any attempt to temper or ennoble the confusion of staring at the beloved. No smile. No eyes. She grants us nothing.

But one might protest: What about those luminous, brilliant nudes? They, at least, surrender to the artist. They are compre hensible. And it must be granted that these nudes are a representational triumph of an entirely different order.

Modigliani doesn’t hurl himself on the fe male figure. Unlike Pierre–Auguste Renoir, whose pictures are strewn throughout the Barnes collection, this artist doesn’t inflate his subjects into formless beings. Rather than avail himself of women’s anatomy, he grants his subjects the essential quality of eroti cism—exclusion.

Georges Bataille, in his comprehensive study on the topic, makes the case that eroti cism rests on difference. There’s an essential discontinuity between the desiring subject and the desired object, and to overcome this gulf would be to die. The temptation to dis solve this discontinuity and cross over is the erotic impulse.

Accordingly, the bodies here are exposed and extended away from the viewer. The fa mous Reclining Nude (1917) recedes even as she welcomes our gaze. To borrow again from Bataille, “Eroticism … is assenting to life up to the point of death.” Here is a woman sus pended between the two.

The result is painted bodies that brim with erotic charge. More than that, they tower— and judging by Modigliani’s lasting popular ity, they endure like all the best–constructed wonders of the ancient world. Modigliani has captured the gulf between lover and beloved.

His is a subtractive eroticism, where beau ty and temptation are found in what’s ab sent. Small wonder that these bodies appear carved out of a whole, muscle and bone al luded to as mere curves but never fully artic ulated. The truth Modigliani lays bare is that we’re attracted to the question mark: what ever is implicit in the body, what can only be coaxed out by an artist or a lover.

ness, and cruelty. In front of Standing Nude (Elvira) (1918), I remember one face in par ticular. What it must be doing now—chewing the end of a pen, squinting at some difficult text, tumbling through a thousand brilliant thoughts. Recently, I found a note that I never sent for lack of courage:

I think of what to paint and always come back to your face. If I close my eyes and try to reconstruct it feature by feature, it’s no challenge. I can see you as clearly as if you were standing in front of me.

I never delivered the portrait I promised. But Modigliani plates that lovely, haunting face up to me now, along with a thousand others. John Berger called his work an “al phabet of love,” but that love, rendered in such firm and finite form, feels remote.

To return to the notion that women can see themselves in Modigliani, if these portraits feel like mirrors, the reflected image stings. Walking through the galleries is akin to cy cling through a rolodex of hurt. Here are the ghostly faces of the mother you never call, the front–row girl you gossip about, the niece or nephew you snapped at. The saint and the sour–faced lover keep each other quiet com pany.

Caught between these mute, listless faces, one is tempted to hew to the cliche of Modi maudit: the damned painter who ravaged his

I look at these nudes, see his earnest long ing, and feel a surge of guilt. My love, unlike Modigliani’s, is cowed by insecurity, fickle

body, his young lover, and his unborn child— and, for that matter, the subject of love for all subsequent painters, for as long as these images persist. Modigliani peeled back the horror of loving another; without even con sidering his tragic trajectory, these portraits are inscribed with the knowledge that the in toxication and surrender of love can so easily unravel into suffering.

cuses and locks you in its disappointment. Like so many Modigliani works, the painting kills.

One look at the angelic, impassive face of The Little Peasant (1918) stops me dead in my tracks. There’s no recourse against the fig ure’s judgment because there are no eyes to meet. Instead, the portrait implores and ac

But maybe there’s another way, the way of Modi the gutter king, who made pover ty sumptuous. Modigliani’s destitution is a known fact. He’s the artist who could feast on only bread and water, who could make the naked body stately. To live on simple, sparse matter, to have everything you own fit into a suitcase, means existence, down to the crumb, has become naked and frontal.

Fabric, sunlight, blood, sky, sex—in Modigliani’s visual lexicon, these terms are equal, and equally venerable. This unique visual register—crude, earthly, and devastat

ing as it is—is apparent in his portraits of his pregnant lover, Jeanne Hébuterne. Here, he offers a way to begin life, not inside another human being, but on a canvas.

The circumstances of her death bear re peating. A century later, they remain un fathomable. The day after Modigliani died of tubercular meningitis aged 35, the heavily pregnant Jeanne threw herself out of her par ents’ apartment window. She was 21.

In the years since, her estate has been no toriously guarded about the details of her brief, tragic life. There’s a grandson who dog gedly refuses to cooperate with biographers, so we’re left with few relics of Hébuterne and the unborn child. The intricate circumstanc

es of their deaths—the cold and the hunger, the father’s illness and the mother’s fatal dis tress—are, miraculously, made cogent here. Modigliani Up Close’s emphasis on physical ity is fitting, given that the paradox of Jeanne Hébuterne (1919) is the paradox of all repre sentation. That child knew no existence, save what’s implied in this unintended memorial. Yet, its being is captured for all eternity. So, too, is Hébuterne’s. And here lies yet anoth er articulation of eroticism: the longing for the sacred, the elevation of human to ghost. The real bodies denoted here are nothing but dust, but the fickle, vaporous feeling of love has been made matter. Flat, sure, on the skin of the canvas. But real matter. ❋

2022 has been a year for rebirth. Not just for us, but also for music.

As we relearn the simple pleasures of packed concert halls and achieving “Certified Fan” status, music, too, is becoming new again. This year, we’ve seen everything from The 1975’s revival of Tumblr alt–rock to Beyoncé’s tribute to Black dance music of the 1970s.

The list of new album releases this year seems never–ending. Luckily, Street has you covered! We’ve collected our staff’s ten fa vorite albums of 2022, which run the gam ut from K–pop to indie folk. Sit back, hit play, and join us in reflecting on this year through song.

— Kate Ratner, Music editor

— Kate Ratner, Music editor

This has been a year is for relearning old habits; likewise, our favorite records and artists made the old feel new again.Erin Ma

Big Thief’s Dragon New Warm Mountain I Be lieve in You is an all–timer.

When I say all–timer, I don’t just mean exceptional; I mean these are songs that feel like they’ve been playing on repeat since the beginning of time. The tune of “Sparrow” is threaded across history all the way back to Genesis, and “The Only Place” plumbs even deeper––to the Big Bang and the formation of the first atoms in the universe. Its con cerns—change and space, heartbreak and death—are writ large across the cos mos, but Dragon is also crammed full of mundane details. Adrianne Lenker un derstands that sometimes even eternity is quotidian.

Top Tracks: “Spud Infinity,” “Little Things,” “The Only Place”

Lenker is the greatest songwriter of our time, bar none. Her intricate poetry is diffuse, like wind blowing through the reeds, and also deeply human—a dense ly packed study of her own life. She’s not afraid to use humor as a stepping stone to transcendence, either; on “Spud Infini ty,” it takes her two lines to wander from kissing our elbows to the “edges of expe rience.” At the end–of–album closer “Blue Lightning,” you can hear one of Lenker’s bandmates asking, “What should we do now?” Dragon is a continuous journey, and with Lenker as our guide, Big Thief allows us to join them for a part of that voyage into the unknown.

— Walden Green, Print editor

Beyoncé’s RENAISSANCE lives up to its title—a cultural and artistic rebirth. As extraordinary as the Queen Bey herself sitting atop a glass horse, clad in precious metals, this album is nothing like what we’ve seen from her so far. Paying homage to the pioneers of ‘70s Black dance music and ballroom culture, “ALIEN SUPERSTAR” calls us to the dancefloor to experience a moment of liberation and cosmic connec tion. This energy persists for the remain der of the album, which is nothing short of a celebration of joy and movement. On “CHURCH GIRL,” Beyoncé reclaims her body, mind, and soul as her own. She has

finally reached a point of solace, “swim min’ through the oceans of tears we cried.” “MOVE” is self–explanatory and arrives without warning. When Beyoncé realizes she’s in full control, there’s no force strong enough to stop her. “I’m with my girls and we all need space,” she demands. “PURE/ HONEY” begins with a sample of Kevin Aviance’s “Cunty”—cunt to the feminine, what?” This song brings the record to a close, inviting the audience back to the dance floor once again. Whether you’re a “bad bitch,” a “money bitch,” or both, this album is for everybody to experience.

— Kate Ratner, Music editorA revolutionary artist who made it ac ceptable to talk about emotions in hip–hop, Kid Cudi offers his deep, psycholog ical take on romance with Entergalactic . In contrast to a previous few albums that touched on poor mental health, depres sion, and addiction, Entergalactic portrays Cudi as a revitalized, healthy artist ready to live happily and lovingly. While Cudi is known for witty, innovative bars, most of the lyrics in Entergalactic are straight forward, joyously recounting the ups and downs of a relationship.

Though the common theme of the al bum is love, Cudi experiments with dif ferent music styles, ranging from mellow, dreamy ballads (“Angel”), to more upbeat R&B tracks like “Somewhere to Fly” with Don Toliver. Swerving from his progres sive drill–style rap, a good portion of the album features Cudi’s distinctive croon, singing about how he “Can’t Shake Her” and the experience of being “In Love.” Cudi uses the more classic hip–hop tracks to reflect the hardships that come with relationships; on “Livin’ My Truth,” he passionately raps about how life goes on and all that’s important is staying true to yourself. Of course, Kid Cudi stays true to his own carefree, drug–friendly outlook with “Do What I Want,” reassuring long time fans that the old Cudi is back—he never really left.

— Ryanne Mills, Staff writer

Therapy and throwing it back are two–for–one with Rina Sawayama’s new album Hold The Girl. Sawayama envisioned her second studio album as a “reparenting” of herself—looking back to her childhood memories and hold ing the girl she once was. While the album is an ambitious endeavor, it doesn’t disappoint. Speaking to her younger self, Rina also speaks directly to the unaddressed feelings and expe riences of her listeners, writing hits that fans can dance their hearts away to while unpacking their childhood trauma. There’s a song for ev eryone in Hold The Girl; Sawayama experiments in storytelling through a variety of avenues, from dance–pop beats with “This Hell” to coun try ballads in “Send My Love To John.” The al bum’s best moments come when she leans into these dichotomies—bridging the differences that exist within our relationships with others and with ourselves. Hold The Girl is the perfect Friday night album, whether you’re going out or crying your eyes out at home.

Top Tracks: “Bread Song,” “Haldern,” “The Place Where He Inserted the Blade”