PG. 23 + PG. 38 Breaking Bread at Clark Park

money

talks

MARCH 2024

Donors Rule Everything Around Me PG. 8

Did They Just Kill Magill?

2 Get more from your shopping. Weekly digital deals and special offers* Easy online shopping Meal planning inspiration Health services * Subject to program terms. Visit acmemarkets.com/foru-guest.html for full terms and conditions. Download the ACME markets app STUDYING LATE? WE’RE OPEN LATE! Domino’sTM SUN-THURS: 10AM - 2AM FRI & SAT 10AM - 3AM WE MAKE ORDERING EASY! CALL DIRECT OR CHOOSE YOUR ONLINE OR MOBILE DEVICE RECEIVE a FREE! 8 Pcs of Bread Twist (3 options) Use Coupon Code [8149] | Minimum $15 Purchase Delivery Only WHEN YOU ORDER ONLINE 215-557-0940 401 N. 21st St. 215-662-1400 4438 Chestnut St.

38 18

Breaking Bread at Clark Park

It's 11:14 a.m. on a muggy Saturday and Clark Park Farmers' Market is humming with life.

Follow the Money Trail

A week in the life of a Penn student's credit card.

36 1 6

The Untold Story of the Philly BYO

Your Friday night Ambrosia is a modern day adaptation of a Philadelphia's history of prohibition.

The Galleries at the Philadelphia Museum of Art that No One Talks About Don't have 14 dollars for a ticket?

43

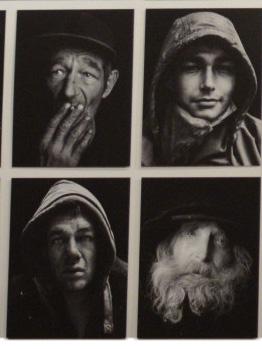

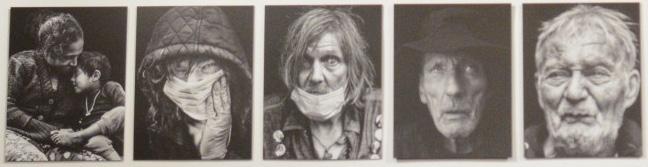

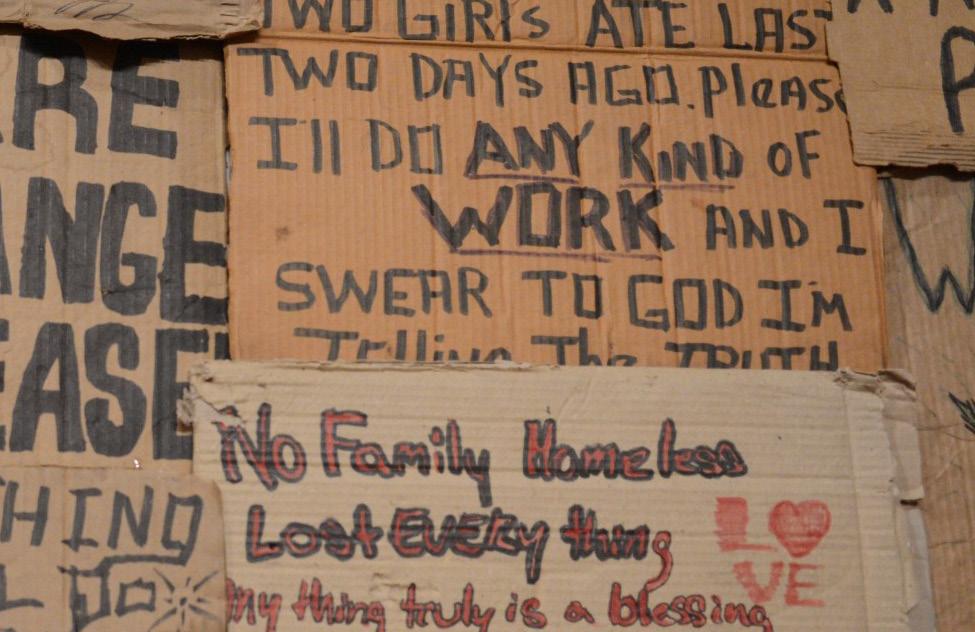

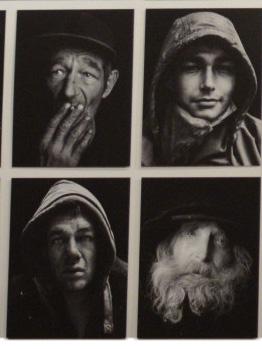

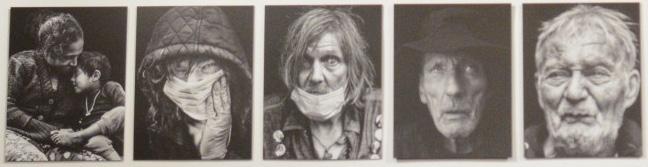

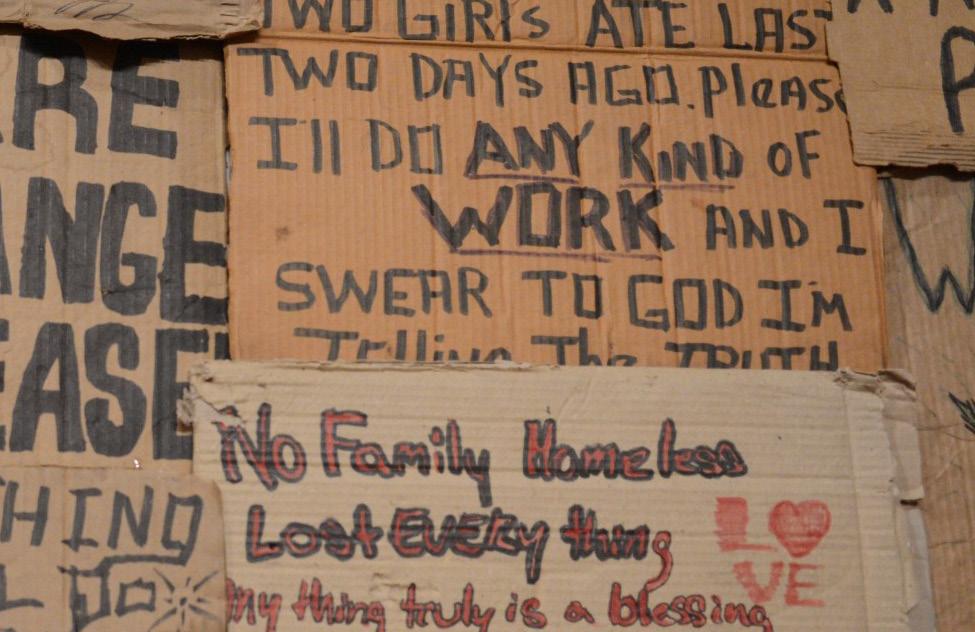

Amplifying Unhoused Voices Through the Power of Art

The Mütter Museum's new art exhibit explores the unhoused experience through the lens of public health.

8

14

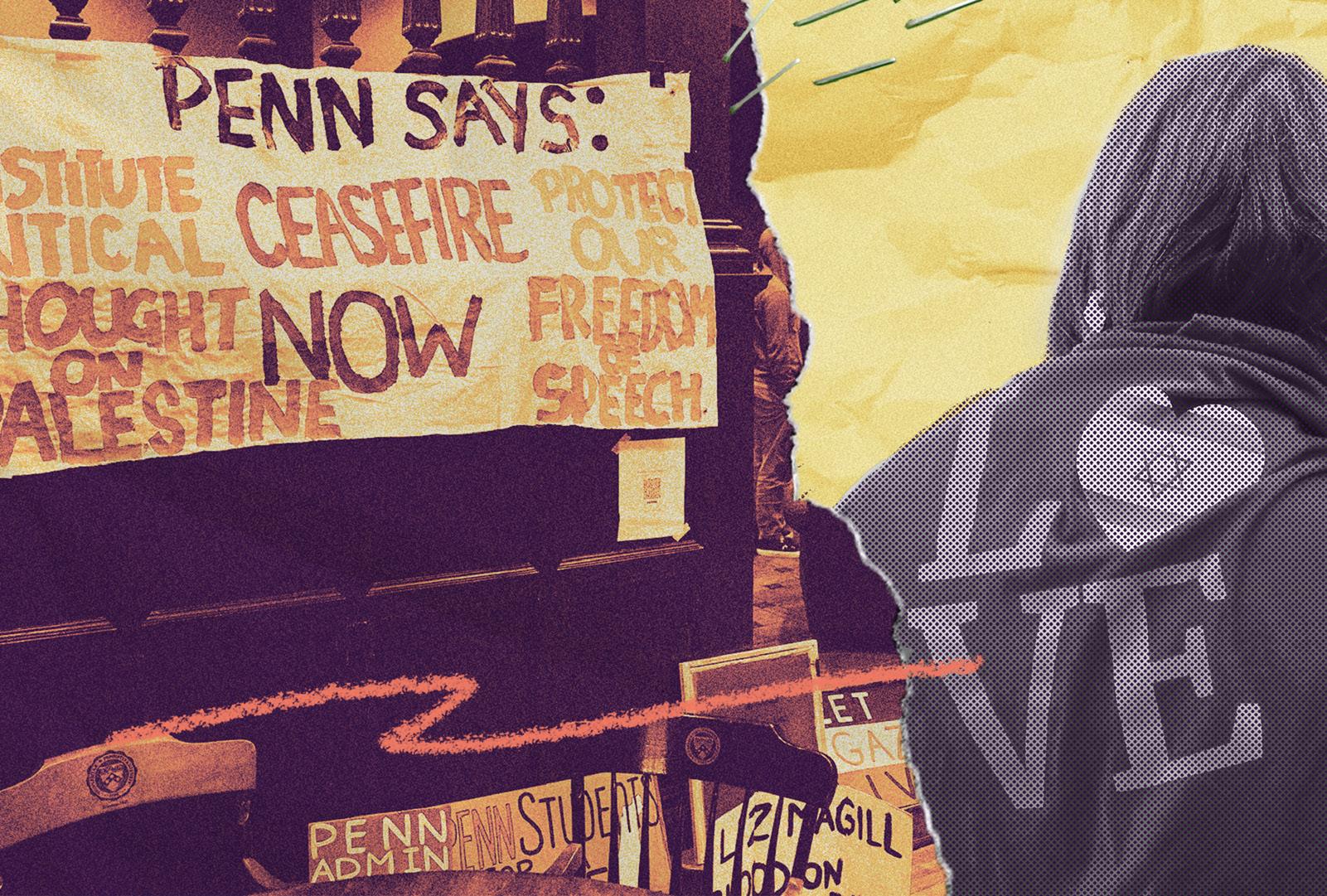

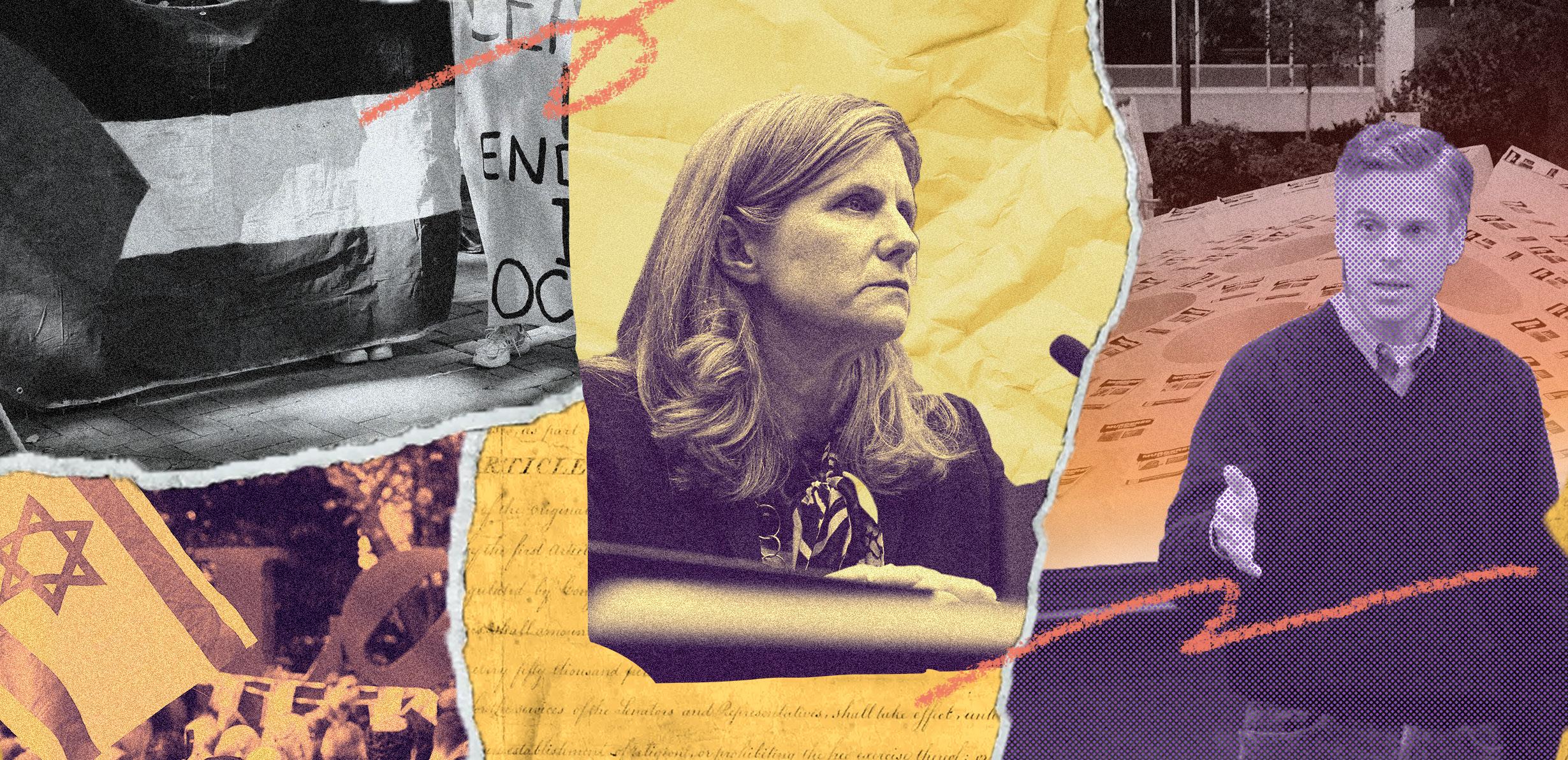

Did They Just Kill Magill?

The newest season of Law and Order begins with an episode that parallels Penn's latest free speech troubles.

Like Taking Collagen From a Baby Sephora is the new sandbox.

FEATURE

Donors Rule Everything Around Me

When money talks, professors are silenced.

23

ON THE COVER

Our gambling addiction all began with monopoly. But if we lost, that money would go fying everywhere on the board.

By Jean Park

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Philosophizing On Material Girls, Money Troubles, and the Multi–Level–Marketing Scheme of a College Education.

At Penn, status is a currency in its own right. Money pumps through the veins of our university—our eyes always green with envy and grasses always seeming greener on the other side of recruitment cycles. Penn is the place where Golden Goose sneakers traipse down Locust and Goyard purses are stuffed to the brim with laptops, Essentia water bottles, and platinum cards. In the words of Madonna, we’re material girls living in a material world.

The gap between the haves and the have–nots at Penn is a cavern. While students jet off to tropical vacations for spring break, other students are knee–deep in belabored FAFSA documents. Sure, our clothes, spending habits, and social groups are indicative of wealth and privilege, but these proxies just scratch the surface of class division at our university.

Last month, The Cut published an article by their financial columnist titled “The Day I Put $50,000 in a Shoe Box and Handed It to a Stranger: I never thought I was the kind of person to fall for a scam.” The internet was set ablaze with debate. Sects of the internet quickly formed, some arguing that they could never fall for such a scam while others sympathized with her.

But let’s be real—we fall for scams every. Single. Day. While we might not be shit out of $50k, we’ve all been swept up in Penn’s financial schemes. From a heinous two—year living and dining plan that promises dorm power outages and cockroaches a-la-mode to the rising cost of tuition, we’re being fleeced. Nevertheless, we persist because we’re told that the Penn education will open doors for us, launch our careers, and yes, hopefully help us “secure the bag.”

However, the promise of financial security post–graduation can mean different things for a student population that ranges from first–generation students to your neighborhood nepo baby. We’re told repeatedly that a Penn education is a privilege in and of itself, but to capitalize off the Ivy name brand students succumb to the pre–professional tides. And who can

blame the student with four years of debt for pursuing their consulting dreams?

Our money troubles took on a new meaning this past fall, extending beyond our pre–professional predicaments. Brought to the forefront of a nationwide debate on academic freedom spearheaded by some of Penn’s wealthiest alumni and donors, Penn underwent a once–in–a–generation identity crisis. In the wake, we’re left to question the role of donors and money in our academic institution.

This month Street explores the age–old adage: “money talks.” From the streets of Philly to the halls of Goldman we lament the graveyard of our artistic dreams abandoned in pursuit of “realistic” prospects. When that first big–girl investment banking check hits we turn to finance influencers on TikTok to tell us how to reinvest to maximize our gains for the future home that we probably won’t be able to afford anyway. Now, as the spotlight fades from Penn’s campus after a six–month whirlwind, we examine the state of free speech asking academics (in the brave words of Oprah) “Were you silent? Or were you silenced?”

While Street doesn’t have a five–point plan to reduce the cost of your Magic Gardens tickets this April or to successfully reinstate your academic freedom, we know better than anyone else that more money means more problems when cash rules everything around us.

EXECUTIVE BOARD

EXECUTIVE BOARD

Natalia Castillo, Editor–in–Chief castillo@34st.com

Walden Green, Editor–in–Chief green@34st.com

Catherine Sorrentino, Print Managing Editor sorrentino@34st.com

Arielle Stanger, Print Managing Editor stanger@34st.com

Norah Rami, Digital Managing Editor rami@34st.com

Alana Bess, Digital Managing Editor bess@34st.com

Kate Ratner, Assignments Editor ratner@34st.com

Collin Wang, Design Editor wangc@34st.com

Wei-An Jin, Design Editor jin@thedp.com

EDITORS

EDITORS

Avalon Hinchman, Features Editor

Hannah Sung, Features Editor

Jean Paik, Features Editor

Jules Lingenfelter, Features Editor

Natalia Castillo, Assignments Editor

Anna O'Neill-Dietel, Focus Editor

Kate Ratner, Assignments Editor

Issac Pollack, Focus Editor

Anna O'Neill–Dietel, Focus Editor

Claire Kim, Style Editor

Naima Small, Style Editor

Sophia Rosser, Ego Editor

Norah Rami, Ego Editor

Nishamth Bhargava, Music Editor

Hannah Sung, Music Editor

Luiza Louback, Arts Editor

Irma Kiss, Arts Editor

Weike Li, Film & TV Editor

Weike Li, Film & TV Editor

Sophia Liu, Design Editor

Rachel Zhang, Multimedia Editor

Jean Park, Street Photo Editor

Kayla Cotter, Social Media Editor

Abhiram Juvvadi, Photo Editor

Jada Eible Hargro, Social Media Editor

THIS ISSUE

Julia Fischer, Copy Editor

THIS ISSUE

Deputy Design Editors

Charlotte Bott, Copy Editor

Wei–An Jin, Ani Nguyen Le, Sophia Liu

Laura Shin, Copy Editor

Design Associates

Deputy Design Editors

Insia Haque, Katrina Itona, Erin Ma, Janine Navalta

Anish Garimidi, Emmi Wu, Insia Haque, Janine Navalta, Katrina Itona Design Associates

STAFF

Asha Chawla

Features Staff Writers

Katie Bartlett, Delaney Parks, Sejal Sangani

STAFF

Focus Beat Writers

Features Staff Writers

Leo Biehl, Dedeepya Guthikonda, Sara Heim, Sophia Rosser, Rahul Variar

Style Beat Writers

Claeb Crain, Keira Feng, Eleanor Grauke, Meeiling Mathur, Lily Markis Mclean, Delaney Parks, Luiza Sulea

Focus Beat Writers

Layla Brooks, Emma Halper, Alexandra Kanan, Claire Kim, Felicitas Tananibe

Music Beat Writers

Maddy Brunson, Charissa Hooward, Prerna Kulkarni, Bobby McCaann, Ellie Meyer, Chloe Norman

Kelly Cho, Halla Elkhwad, Ryanne Mills, Olivia Reynolds, Mehreen Syed

Style Beat Writers

Arts Beat Writers

Madeline Kohn, Steven Li, Natasha Yao

Jojo Buccini, Jessa Glassman, Eyana Lao

Music Beat Writers

Film & TV Beat Writers

Jake Falconer, Meehreen Syed, Ananya Varshneya

Mollie Benn, Kayla Cotter, Emma Marks, Isaac Pollock, Catherine Sorrentino

Arts Beat Writers

Ego Beat Writers

Sophie Barkan, Noah Goldfischer, Ella Sohn, Vikki Xu

Maya Grunschlag, Dylan Grossmann, Kyunghwan Lim, Neha Peddinti, Hannah Qiu

Film & TV Beat Writers

Staff Writers

Aden Berger, Bea Hammam, Emma Halpher, Fiona Herzog, Erin Jeon, Amy Luo, Thu Pham

Ego Beat Writers

Morgan Crawford, Heaven Cross, Angele Diamacoune, Rayan Jawa, Enne Kim, Jules Lingenfelter, Luiza Louback, Dianna Trujillo Magdalena, Yeeun Yoo

Audience Engagement Associates

Sophie Barkan, Parin Keerthi, Gemma Levy, Talia Shapiro, Ella Shusterman, Leah Weinberger, Rosemary Yang

Staff Writers

Annie Bingle, Ivanna Dudych, Yamila Frej, Lauren Pantzer, Felicitas Tananibe, Liv Yun

Charlotte Comstock, Julia Fischer, Caitlyn Iaccino, Andrew Lu, Maia Saks, Zaara Shafi, Aaron Visser

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Land on which the office of The Daily Pennsylvanian stands is a part of the homeland and territory of the Lenni-Lenape people. We affirm Indigenous sovereignty and will work to hold the DP and the University of Pennsylvania more accountable to the needs of Indigenous people.

The Land on which the office of The Daily Pennsylvanian stands is a part of the homeland and territory of the Lenni-Lenape people. We affirm Indigenous sovereignty and will work to hold the DP and the University of Pennsylvania more accountable to the needs of Indigenous people.

CONTACTING 34 th STREET MAGAZINE

CONTACTING 34 th STREET MAGAZINE

If you have questions, comments, complaints or letters to the editor, email Walden Green, Editor–in–Chief, at green@34st.com You can also call us at (215) 422–4640.

If you have questions, comments, complaints or letters to the editor, email Natalia Castillo, Editor–in–Chief, at castillo@34st.com You can also call us at (215) 422–4640.

www.34st.com © 2023 34th Street Magazine, The Daily Pennsylvanian, Inc. No part may be reproduced in whole or in part without the express, written consent of the editors. All rights reserved.

www.34st.com © 2023 34th Street Magazine, The Daily Pennsylvanian, Inc. No part may be reproduced in whole or in part without the express, written consent of the editors. All rights reserved.

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 4

STROOSE

YHBPYANOOMEE

Photo by Jean Park

Hometown

Union City, New Jersey

Major Nursing Activities

Minorities in Nursing Organization, Penn Tabletop, Penn First Plus, Research with Kathryn H. Bowles, Adriana Perez, George Demiris, Nancy A. Hodgson, and Maya N. Clark–Cutaia, TA for Jianghong Liu

Growing up with her grandparents, Samantha Cueto (N ‘24) developed a soft spot for the geriatric population. Now a senior at the School of Nursing, Samantha has dedicated her time at college toward conducting extensive research supporting the elderly. She has particularly enjoyed spearheading a community–based intervention aimed at increasing physical activity among Hispanic elderly individuals with dementia or cognitive impairment. When Samantha's not helping elderly patients at local hospitals and clinics or uncovering medical breakthroughs in the research labs, she’s playing Dungeons and Dragons with Penn Tabletop Club, practicing Japanese, or watching horror movies with her friends. Samatha’s positive energy radiates when she expresses her gratitude to her friends, the people who have undoubtedly made her Penn experience.

What inspired you to apply to Nursing?

When I was a senior in high school, we had to do a bunch of volunteer hours. Initially, I didn't think that I would go into nursing because my mom is a nurse and I was always like, “I don’t want to do what my mom does.” But, I ended up volunteering at an elderly care center. For background, I feel like my grandparents had a really big part in raising me, so I've always had a soft spot for the geriatric

Samantha Cueto

With countless hours spent in the research lab, Samantha Cueto is making a profound on the Philly community.

BY SOPHIE BARKAN

T his in T erview has been edi T ed and condensed for clari T y

Photos courtesy of Samantha Cueto

CAMPUS EGO OF THE MONTH EOTM

population. My time volunteering at the elderly care center included assisting the people in daily living, having conversations with them, and working with nurses. I also talked to the nurses about why they began their careers. In high school I really loved science, but I'm also a pretty sociable person. So, I wanted a career where I'd be talking to people and not one where I’d be behind a desk all day. I also didn't want to go to medical school for seven years. That’s a long time! When I visited Penn, I spoke to the admissions director of [the School of] Nursing. She explained that there are so many career paths for nursing such as midwifery and pediatrics. Talking to her really helped me zone in on that, and I decided to look into nursing.

How has your interest in the geriatric population influenced your research at Penn?

I've done tons of research at Penn. I'm super detail–oriented, and I like working on these projects and seeing them slowly build up. Since freshman year, I've always held around two to three jobs and have tried to do as many research opportunities as I could. I've always loved working with these professors and doing various projects.

A lot of my research focuses on elderly people. For example, I worked for Dr. George Demiris for one summer, and I was able to talk to researchers in Japan about the technology they are building for elderly people. Right now, I'm working with Dr. Kathryn H. Bowles, and I go into the hospital and talk to patients with sepsis. I interview them for about an hour and talk to them about their experiences having sepsis. I like doing research because you really get to see the gaps in the current healthcare system and make a direct impact on people.

I also worked with Dr. Adriana Perez, and her research left a big impact on me. It was my target population, the elderly population, but specifically, we worked with Hispanic elderly individuals with

dementia or cognitive impairment. That really meant a lot to me coming from a Hispanic background. It was the first time that I started going out into the field, meeting the people face–to–face, and talking to them. This research was a community–based intervention where we were trying to increase exercise in these Hispanic communities. They were living in apartments together, and I would go in and conduct interviews. The Hispanic elderly individuals were always so friendly. When we would come into their homes they would offer us food. I felt like I was talking to my grandparents every time I was talking to them because they were so friendly and treated me like family immediately. By going out into the field and being in their space, I was able to learn about their lifestyles. It was my first time actually working with these research tools

and translating this type of friendly conversation into empirical evidence.

What has been your favorite clinical experience during your time at Penn?

My clinical last semester was for community health at Nurse–Family Partnership. Their patient population were mothers with infants up to three–years–old or pregnant mothers. We would go into their homes and do a lot of patient education. For example, if a mother was six months pregnant, we would tell them not to do a lot of exercise. Or, if we were dealing with a mother with a two year old, we would talk about introducing new foods. I really liked it because I feel like with community nursing, you get to make the widest impact on people, and you get to directly meet them too. These were low–income mothers as well, and

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 6

CAMPUS EGO OF THE MONTH

many of them were on food stamps or had trouble maintaining their jobs. I was really happy talking to them and learning more about them. It just reminded me of why I went into nursing in the first place. I really liked that clinical most as it allowed me to reach so many people in need.

How has being FGLI impacted your Penn experience?

That was actually how I met my very first friends at Penn. I would say I'm low–income, but I'm not first gen. Still, I was invited to the Penn First Plus pre–freshman program, and that's how I was able to meet my nursing friends. Those are the very first friends that I made. It's been so fun and amazing with them. It's good to talk to them and stick together because I feel like sometimes at Penn, impostor syndrome is really, really big, especially coming from a low–income background.

Can you tell me about your involvement in Penn Tabletop club?

It's pretty nerdy. We play Dungeons and Dragons together. Freshman year, when it was COVID, this was where I first found my first group of friends. We would meet every weekend, talk to each other, and play together for a couple of hours. I’ve continued going throughout the years, and it’s been really fun. Penn Tabletop has definitely helped me feel creative. I was always unsure if I was creative until I played D&D and saw everyone’s ideas fly off each other and create really crazy scenarios.

What are some of your favorite things to do in your free time?

Japanese class was one of the best experiences I've had at Penn. I picked Japanese for a complete ego reason because I'm Latina and if someone asks me what languages I speak, I can say “English, Spanish, and Japanese.” Learning Japanese has a really close place in my heart. I love learning the language just because

it's completely different from English and it's just so rewarding.

I also really love playing with my Nintendo Switch. When my friends come over, sometimes, we will all play a game together. I've always loved Nintendo since I was a kid. Some of my earliest memories are from playing the consoles.

I also really enjoy watching movies. I've tried to take some cinema classes even though they're not in my nursing curriculum because I love talking about movies. Last year, I took Japanese cinema, and I loved watching the movies and talking about them in class. This year, I'm taking Korean cinema. My family loves horror, so I grew up watching horror. I think that some of the best horror movies are Korean horror movies. I literally joined the class just to talk about Korean horror movies and be exposed to more movies.

Where on campus have you found the best sense of community?

I have this one friend group that I joined sophomore year, and we’re a very

tight friend group. We meet nearly every day. Sophomore year when I first met them, we would go to the rooftop lounges in Harrison or Harnwell multiple times a week and stay there until 5 a.m. I loved the rooftop lounges, it was so much fun. Overall, I’ve just loved gathering with my friends in different places on campus. My friends are the people that have made my Penn experience.

What’s next for you after Penn?

Currently, I'm in a loan forgiveness program with Penn. They give me more aid junior and senior years but in return, I have to work for two years at the Penn Medicine Princeton Medical Center. I’m going to try and work in the ICU for two years at the Princeton Medical Center. After that, I'm currently unsure because I really, really love research, but I’ve also really liked my time that I've had in the ICU. I'm just going to see how I feel at the end of my two years. I'm either going to try and see if I can go to grad school for nursing anesthesia or go to grad school to do nursing research and get a Ph.D. ❋

Favorite place to eat around campus?

Ochatto (I know, it’s a hot take)

Favorite movie?

The Shining

No-skip song?

“See You Again” by Tyler, The Creator

Early bird or night owl?

Early bird by force

There are two types of people at Penn … The people who are career–driven and the ones that are more relaxed and enjoying college.

And you are?

I would like to say the enjoying college one, but I’m probably the career–driven one.

7 MARCH 2024

Did They Just Kill Magill?

The newest season of Law and Order begins with an episode that parallels Penn’s latest free speech troubles.

BY NORAH RAMI Graphic by Anish Garimidi

It’s late at night, the sky deep purple against the New York City skyline as Hudson University President Nathan Alpert walks home. He’s agitated; criticism has been coming from every direction. The campus is in the midst of mounting tensions between pro–Israel and pro–Palestine advocates. Donors have pulled out funding and student groups are protesting. He’s heading home though, complaining to his wife on the phone over the contents of the day and promised a relaxing night for his troubles. But he pauses mid sentence, noticing students spray painting political imagery onto a building. He yells out to them as they disperse and turns to leave. But in that movement, his eyes widen. Out of nowhere, a knife plunges into the president’s body. He falls.

The Law and Order theme song plays and the screen turns black, reading: "The following story is fictional and does not depict any actual person or event."

Did they just kill Liz Magill?

On Jan. 18, America’s favorite legal drama, Law and Order, aired the first episode of its 23rd season. Titled “Freedom of Expression,” the hour–long segment follows the unraveling of a trial surrounding the murder of imagined Hudson University President Nathan Alpert.

The episode is underscored by mounting tensions regarding free speech amid pro–Israel and pro–Palestine demonstrations. The university president remained a controversial figure, characterized by some as an irresponsible advocate of free speech and criticized by others as biased and politically immoral.

Despite opening with a disclaimer that all people and events depicted are "fictitious," Law and Order often explicitly draws inspiration from real–life crimes, from the contemporary Spa Shootings in Atlanta to the reemerging obsession with Jeffrey Dahmer. The show’s plots are often considered “ripped from the headlines.”

It’s clear that the Season 23 premiere is a close allegory of the current campus free speech conflict across the nation, referencing Penn most specifically. For the past year, former Penn President Liz Magill has faced scrutiny from all sides—donors, national media, and Congress—over her response to campus speech in the wake of the Israel–Hamas war, culminating in her resignation.

In the Law and Order episode, the Hudson University president is facing similar backlash for his handling of campus expression. The episode is littered with references that map almost exactly to real–life events that have

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 8 CULTURE // FILM & TV

occurred here on campus, to the point that Alpert’s death seems representative of Magill's resignation.

In the episode, donors were pulling out funding from the fictional campus over a Palestinian film festival, which parallels the Palestine Writes Literature Festival that catalyzed Penn’s first wave of donor threats and pushback. Hudson University students who were organizing for Palestine were disappointed by their president’s threats to discipline a student group for showing a film critical of Israel, not far from Penn’s reaction to the Israelism screening by the progressive Jewish group Penn Chavurah. There’s even an out–of–place reference to a professor who was fired for criticizing transgender athletes, referencing a national cultural debate that took place center stage here at Penn.

At one point, a cop asks exactly what we’re all thinking, “Isn’t that like what happened at the University of Pennsylvania?”

It wasn’t until over two decades after he graduated from Penn that alumnus Dick Wolf (C '69) created the hit NBC show Law and Order With over 490 episodes, the show has developed into a full universe that has played a critical role in informing the American pub-

lic’s perception of the criminal justice system. Wolf, attributed as one of the richest men in television, has been closely involved with Penn’s campus, funding the development of the eponymous Wolf Humanities Center and endowing the Dick Wolf Associate Professor of Television and New Media Studies in the Cinema Studies Department.

In the last year, however, Wolf joined the ranks of donors who have cut ties with Penn. Wolf called for Magill and former Penn Board of Trustees Chair Scott Bok to resign over the Palestine Writes Literature Festival. On Oct. 18, 2023, Dick Wolf sent a letter to Penn on Law and Order letterhead criticizing what he viewed as the emergence of hate speech on Penn’s campus. Exactly three months later, those very criticisms were rendered tangible on an episode of Law and Order itself.

Like any serial drama, Law and Order doesn’t pretend to espouse deconstructive legal theory. Rather, the crimes are salacious, existing largely for the entertainment of the weekday cable television viewers. The show is formulaic and predictable. Wolf himself laid out the recipe for every Law and Order episode to The Washington Post, stating, “Stories reflect current events but the show is basically the

9

MARCH 2024

same. A murder mystery in the first half with a moral mystery in the back half.” Still, even with its lack of nuance, it provides unique insight to how the public understands and interprets the nature of the current events and crimes depicted.

As 20th century German film critic Siegfried Kracauer stated popular mass media represents “the daydreams of society, in which its actual reality comes to the fore and its otherwise repressed wishes take on form.” In other words, as a means of popular media, the Law and Order episode can be interpreted as casting aside the truth and instead providing weight to the fears and perceptions around the current campus expression tensions.

Law and Order’s “Freedom of Expression” episode is a visual manifestation of those worst fears surrounding campus speech. The episode imagines a universe where unhindered speech on campus is fresh kindling for overt violence and instability. Simply put, it’s the worst nightmare of Penn’s donors—and everyone else watching this conflict play out on campus.

The episode surmises that free speech is a dangerous enterprise. After all, the fictitious university president’s murder isn’t the only death. Halfway through the episode, a president, a pro–Palestinian student–activist, and a pro–Israel professor are dead.

Gratuitous violence is hardly shocking within the soapy drama of late–night legal television. Still, there’s something particularly unsettling in watching characters, people who could easily represent your peers or professors, murdered in an alternate universe of your reality for the entertainment of audiences across the nation. Free speech kills presidents, but it also kills students and professors too.

In the United States, hate speech is protected under the First Amendment. There is no separate category of speech that regulates speech with potentially hateful content. Instead, under Supreme Court precedent, it is only once language translates into violence and harm that stopgaps are put in place. Think, “sticks and stones may break my bones but words may never hurt me.” But even then, the bright line between speech and harm is hard to place.

The Law and Order episode creates an explicit connection between ideas and action by indicting a professor who supposedly planted the idea in a student’s head to kill the president, even if she herself was not involved in the murder. At the end of the episode, it is a pro–Palestinian, presumably middle–class, white male college student charged with the president’s murder. It is implied that he’s been brainwashed by his Middle Eastern professor, Dr. Nassar, who frequently lectures to students about the Palestinian cause. His parents, straight out of a Norman Rockwell painting, are aghast at the transformation of their perfect boy in the clutches of Dr. Nassar’s manipulation.

Dr. Nassar is put on trial in an attempt to draw a connection between her ideas and his action—as if it were her words that stabbed President Alpert. She is the one, it is said,

Free speech kills presidents, but it also kills students and professors too.

who put the knife in the student's hands and the ideas in his head. However, at the end of the show, she is acquitted and the student is put behind bars, his parents crying as he is dragged off stage.

Around 80% of Law and Order episodes end in some sort of victory, so it feels intentional that Dr. Nassar walks free in the end. The image of higher education as a factory of indoctrination has long been pushed by conservatives, who point to critical race theory and gender studies as harbingers of the collapse of American values. A significant majority of Republicans agree that college professors are trying to “teach liberal propaganda.”

The episode places these fears into the context of the campus free speech wars. With this rhetoric, Law and Order asserts that free speech conflicts on campus are no longer about the authentic expression of young voices. Rather, the current tensions are presented as a symptom of the age–old indictment that universi-

ties are transforming students into soldiers for some imagined “woke agenda.” The students in the episode are represented as puppets for the will of adults, their ideas naive. They have no agency and even fewer lines.

On Friday night, on Penn’s campus, my friends hunkered down for bad TV and a stomachache–inducing ration of snacks. Earlier that week, there had been a demonstration by professors for academic freedom in the face of growing threats to its integrity.

Settling onto a haphazard arrangement of beanbags, we all sing along to the Law and Order theme song “Dun Dun” and laugh about our old lady TV habits. This Friday night ritual was our means of escapism. Instead, we found ourselves transported to an alternate reality of the world outside my dorm. We saw ourselves represented on screen, but as though we were looking at a funhouse mirror, laughing as we pointed out distorted campus reflections.

For Penn students, the Law and Order episode is nothing more than a caricature. But it would be naive to cast it aside as simply “bad TV.” Crime shows like Law and Order significantly impact viewers’ understanding of the news. In that lens, “Freedom of Expression” only continues to promote misunderstanding and misconceptions around free speech on Penn's campus. This sensationalization will only perpetuate the rising tensions between our real lives here on campus and an outside world attempting to peer in. k

You lost one of your three Canada gooses!

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 10

CULTURE // FILM & TV

Jazz was Never Dead, and Laufey Didn't Save it

Critics tout Laufey as the "savior of jazz," while ignoring the rich history of the genre.

BY NATASHA YAO Graphics by Anish Garimidi

11 MARCH 2024

CULTURE // MUSIC

Laufey is the savior of jazz.

At least according to Roll ing Stone , NPR , Billboard , and more.

Laufey (pronounced LAY-VAY) is an Icelandic–Chinese singer, multi–in strumentalist, and songwriter. Draw ing inspiration from Ella Fitzgerald and Chet Baker, Brazilian bossa nova, and her own background in classical music, Laufey’s songs are an amalgamation of all things mid–century. The artist blew up on TikTok with her single "From the Start" in May 2023—less than a year later, she won her first Grammy for her sophomore record, Bewitched . The Bewitched tour showcases the singer effortlessly switching from the piano to the cello, all while singing. The 24–year–old is extremely talented, to say

However, whether or not she is the “savior of jazz“ is debatable. After all, what is jazz? YouTuber and musician Adam Neely identifies the characteristics of her songs that could categorize them as jazz. She draws inspiration from Chet Baker’s scat improvs in her single "From the Start," utilizing syncopation and arpeggiation—all features of jazz.

Yet, there are few agreed–upon definitions of jazz. In a 2001 documentary,

and current artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center , discuss the criteria for the genre. Marsalis states that jazz must have swing, the blues, and improvisation. By these criteria, Laufey would not strictly be jazz. It’s worth noting, though, that Marsalis has a pretty conservative view on jazz and lists these criteria with the intent of keeping out the new evolv ing genre of jazz fusion. On a technical level, Laufey draws inspiration from so many sources that it would be diffi cult to corner her into a specific genre. The Grammys categorized Bewitched as "Traditional Pop," while others call her a mid–century pop singer.

Beyond whether she can be consid ered a jazz artist or not, the issue here lies more in what Laufey being touted as the savior of jazz says about the state of the genre, and what it should repre sent. The genre is much more than just the sound and characteristics of the music. Jazz has cultural significance, and can't be separated from its history of struggle.

Black artists were continually exploited in the industry. Black jazz musicians did not have control over recording and distribution industries; more often than not, the richest jazz artists were white. The industry required a certain level of uniformity for recording, which led to jazz losing out on its crucial characteristic of improv. With this criteria, white jazz bands offered the level of uniformity that recording studios looked for and reaped the economic benefits. Still, jazz created a sense of social cohesion and identity for Black Americans at the time. After World War I with the introduction of the Prohibition, jazz came to gain traction on radio stations and represented a sense of rebellion and freedom in illicit speakeasies. It was also widely accepted overseas, where Black jazz musicians were given many performance opportunities.

Born in the early 20th century in Black and Creole social clubs of New Orleans, jazz developed as resistance music. “It was absolutely about where people weren’t allowed to go, which made them travel in their music,” artist Georgia Anne Muldrow says. Jazz allowed Black artists to integrate with white musicians and, for a select few, offered the chance of social mobility.

However, once production companies discovered the profitability of jazz,

In the 1960s, jazz began to be recognized by institutions as American classical music. American universities wanted to include jazz in their curriculum. But when saxophonist Archie Shepp was hired by the University of Massachusetts in 1969, he was not al -

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 12

CULTURE // MUSIC

The genre is much more than just the sound and characteristics of the music. Jazz has cultural signifcance, and can't be separated from its history of struggle.

lowed to teach jazz in the context of race and history. Although times have changed since then, and jazz curricula are more willing to discuss its historical context, the study remains inaccessible to the very people who created it. According to the United States Department of Education, less than ten percent of students who graduate from American universities with jazz degrees each year are Black.

In an interview with Zach Sang, Laufey acknowledges that jazz can be out–of–reach, given that there is a general notion that you have to be educated to talk about it. She also ad mits that she sometimes feels “small” talking about it, despite having attend ed Berklee College of Music. Especially for younger generations, jazz can feel like it isn't for them. It doesn't help that the most authentic way to consume jazz is often in speakeasies or lounges that younger people cannot attend. So while Laufey may not be considered a full–on jazz musician, what she does do for the genre is make it less intim idating for Gen–Z listeners. She does not box herself into the genre of jazz, as she says to Sang. Instead, the way peo ple consume music now is often based more on a mood or a vibe rather than

a genre (think of those "POV: Dancing in your kitchen" playlists). Jazz itself is also an evolving genre, and there are different schools of thought on what exactly jazz is. As Amiri Baraka said, “[Rhythm and Blues] is contemporary and has changed, as jazz has remained the changing same.”

Yet, with jazz being born out of Black American culture and the opportunities it gave to Black artists, it's tone–deaf for elite music publications to label a non–Black artist the “savior of jazz.”

If we want to talk about young Black jazz artists, we can turn our attention to Samara Joy. The 24–year–old singer from New York City won three Grammys this year, one for Best Jazz Performance. Esperanza Spalding is another contemporary jazz singer. She also attended Berklee and has five Grammy awards to her name. If you want to listen to some live jazz, you can tune into “Live from Emmet’s Place.” The stream started during the COVID-19 pandemic when jazz musicians had nowhere to perform. A major element of jazz is the community and the culture. Because of the improvisation aspect of it, jazz players need to play live and around

each other to thrive. Now, to be on Emmet Cohen's stream is considered a prestigious achievement. Whether Cohen intended it or not, his arrangement of having jazz players in his Harlem apartment living room is a brilliant nod to Harlem rent parties, where tenants would hire musicians to perform and raise money to pay rent. These venues became breeding grounds for budding jazz artists.

So, jazz is not really dying, and Laufey is not doing the saving. One can definitely acknowledge her contributions to the genre without dismissing her contemporaries. To dismiss her for not following jazz conventions because of the specific technicalities of her music would only contribute to the gatekeeping of jazz. Jazz is associated with the idea of liberation, and it should be free to everyone as long as we acknowledge its origins and credit the Black artists who created it.

Laufey never really sets out to "rescue" jazz; she simply pulls inspiration from different genres to create a timeless sound that, as she says, “can remind older generations of something they listened to when they were young and is something new for younger generations and can tie those generations together.” As long as jazz, by Laufey or by anybody else, is still being listened to, it will never need a savior. k

13 MARCH 2024

ISephora is the new sandbox.

BY ZAARA SHAFI Illustration by Emmi Wu

first dipped my toes into the world of beauty and skincare at the age of nine. As soon as my mom left to run errands, I snuck into her room and planted myself at her magical vanity. With the contents of her makeup bag laid out in front of me, Zoella’s iconic makeup tutorials playing on an iPad mini, and a luxurious black bullet of lipstick in hand, I meticulously applied a scarlet shade to my lips. Armed solely with practice in using Maybelline’s BabyLips, it’s no surprise that the final result was far from ideal—I looked more like Miranda Sings than Red–era Taylor Swift.

As a beauty–obsessed preteen in the 2010s, I quenched my thirst for makeup and skincare by secretly using my mom’s collection and

subsisting on the three products I owned. For young girls today, the situation could not be more different.

The epidemic of 10–year–old girls crowding Sephoras worldwide has set the internet aflame. But why is this such an issue? According to a plethora of TikTok storytimes by Sephora employees and customers, these girls are not the easiest of customers: Most of them, who come in search of expensive viral skin care products, often mistreat employees and leave stores in disarray. In a Vanity Fair article, a Sephora employee recounts young girls pumping foundations onto the floor and drawing on displays with lipstick.

An essential part of girlhood is the desire

to be treated as equals to adults. The controversial “Sephora Gen–Alphas" seek to embody the “perfect” female influencers they idealize, from their dietary restrictions to their beauty routines. In a 2021 study, The New York Times highlights how Instagram worsens body image issues for one in every three teenage girls. Ads and other online content glamorize disordered eating and excessive exercise, instilling a desire in women and girls to be “skinny.” By adding clear and smooth skin to our "things–women–must–aspire–to" list, body image issues in women and girls will only heighten.

Young girls look to emulate their favorite influencers from head to toe: They want to look like them, dress like them, and, of course, have

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 14

CULTURE // STYLE

the same airbrushed skin that they have. What better way to do this than buy the very products these influencers use? Some have referred to this fixation on skincare as dermorexia, and its repercussions can be disastrous. From their tweenage years, girls begin comparing themselves to the faces and bodies they see on social media, catalyzing a vicious cycle of deteriorating self image and mental health.

Moreover, the physical effects of an over–reliance on skincare can be consequential. When it comes to skincare, the overarching mantra on TikTok preaches that more is better. Layering too many products, however, can do significant damage to the skin’s moisture barrier, which can worsen skin issues. By constantly buying

and trying new skincare products, young girls may intensify any future skin problems.

As we watch a plethora of young girls showcase their 10–step skincare routines and post “What I Got For Christmas" hauls to thousands of online followers, we have to ask ourselves: Does this signal the demise of the preteen phase? The preteen years mark a critical moment of transformation in a young person’s life. My preteen self was obsessive, chaotic, and weird (I, for one, had an entire diary dedicated to One Direction, with every fact I could find about them, from the exact minute they were born to their blood types). I wore hideous outfits to later cringe at, filled photo albums with embarrassing selfies, and tried so hard

to recreate Cara Delevingne’s heavy brow look. However, after all this time, I wouldn’t be the person I am today without my pre–teenage years. They gave me space and time to grow into the best version of myself (I threw my 1D diary away, I promise).

It is no secret that the preteens of 2024 have strayed from boy band obsessions and Rainbow Loom addictions. While it’s jarring to see a 10–year–old girl applying Drunk Elephant moisturizer in her neon pink bedroom, this is no laughing matter. Just like me, she deserves the time to enjoy her defining preteen years (even the awkward moments); the burden of obsessing over her body or skin will only weigh her down. k

15 MARCH 2024

The Galleries at the Philadelphia Museum of Art that No One Talks About

Don’t have 14 dollars for a ticket?

In 1967, Darryl “Cornbread” McCray had a crush. Many modern teenagers would meander endlessly through a tedious talking stage that takes months to develope, but Cornbread had some gargantuan balls. Using a can of spray paint, he began tagging “CORNBREAD LOVES CYNTHIA” around the streets of Philadelphia as a vehicle for his intense feelings. McCray didn’t know it then, his public display of puppy love would be the predecessor for the modern graffiti movement marked by the likes of Bas-

BY KYUNGHWAN LIM

Graphics by Emmi Wu

quiat and Banksy.

Today, McCray has since given up tagging the streets, but many continue his legacy to prop up Philadelphia’s title as the “Mural Capital of the World.” Yet, despite the city’s role as the birthplace of the art form, street art lacks a place in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Well, indoors, that is. If you take a look outside, the nooks and crannies of the Greek Revival architecture are plastered with Rust-Oleum.

For instance, muralists have taken a

liking to the north and south ends of the museum due to copious amounts of vegetation that will keep their work from being detected. However, the south end contains an exposed wall where a single artist has flouted among the rest. As if to openly challenge the high–and–mighty art of the museum, our anonymous graffitist has placed two cheeky human–like faces on opposite sides of an ornate facade decorated by Greek sculpture and lettering. The resulting juxtaposition is comical, a visual dialogue between the

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 16 CITY // FOCUS

worlds of “sacred” and “profane” art.

And just a few steps away, onlookers find the work of an artist I’ve dubbed Steve at the North Cliffside Path. Steve uses a particular shade of black paint so dark it absorbs the various textures of the sharp crags and the plants into a dark void. With this as his weapon of choice, Steve signs his name and grafts “FREE MICHAEL WES JOS TOVELOKE R.DOT” among other monikers onto the mossy rock. The lettering is in the '70s punk style associated with Stüssy and The Sex Pistols, a common motif in graffiti.

Yet, the most impressive collection of graffiti at the museum is located on the southwest end of the museum directly facing the Schuylkill. From its humble beginnings as a SEPTA trolley path, the Spring Garden Street Tunnel is now a

poorly maintained one–way road that’s filled with trash and flickering lights—a perfect breeding ground for street art. Although it’s probably the creepiest place I’ve ever stepped foot in, my anxiety fades as I gaze in awe at the paint–covered walls. Unbridled by the seclusion of the location, the artwork here is beautifully chaotic. The block letters of the throw–up lack structure, the color palette is almost Fauvist, and the jumbles of text don't hesitate to tower over the viewer as they go from one end of the tunnel to another. Some of my favorites among these works include a caricatured drawing of a man on fire that looks as if a Schiele self–portrait was high on copious amounts of weed.

However, the most exciting thing

the work I just described will exist in a couple of weeks. Unlike various Picassos and Rubens stored just a few hundred feet away, the Philadelphia Museum of Art doesn’t conserve or restore any of the “vandalism” on their property, leaving it to the weather or government groundskeepers to clean it up. But the blank slate they’ll leave behind will give way to a fresh generation of graffiti, with each wave yielding to the birth of the new. This is what sets the genre apart. Unlike its museum counterparts, graffiti thrives on any form of decay—whether that be the North Cliffside Path, the Spring Garden Street Tunnel, or the fading ink of its forefathers. Who knows, maybe Steve’s tags are sitting on top of where Cornbread felt love for the first

9:00 a.m. — Usual coffee of the day, this time at Stommons.

7:00 p.m. — Incredibly cold day. The type of cold that makes you NEED a ramen desperately. I decided to go to Terakawa Ramen, which never dis- appoints. 19 dollars for the best ramen I have ever had.

Day One: Girl Math Monday

9:00 a.m. — Wait in line at Stommons to get an iced caramel macchiato and a plain bagel with cream cheese. In my mind, it's free because it’s dining dollars. Girl math.

9:20 a.m. — Change of mind, going to Saxby’s; the line at Stommons is too long.

9:30 a.m. — Just paid 15 dollars for a bagel and a macchiato. My mind immediately converts this to my country’s currency. Ouch! That was expensive.

12:00 p.m. — Really wanted to eat off campus at places like DIG or Honeygrow. Thought twice about spending more than 20 dollars on a meal. Okay ... let’s go to KCECH.

The only thing good about KCECH food is the pizza. The. Only. Thing. Oh, and for the omelets you have to wait 10 minutes in line.

1:00 p.m. — Craving some dessert after lunch (also, I'm on my period). Went to CVS, and craved every bit of Reese’s peanut bu er cups (the thin ones) and the chocolate raspberry TruFru. Or should I get sea salt caramel instead?

Decided to get TruFru. It is an obsession by this point.

3:00 p.m. — Ordered a book at Amazon for a class. Modern and Contemporary Irish Drama would not be my first choice for spending 33 dollars.

STYLE

A week in the life of a penn student's credit card

BY LUIZA LOUBACK

Follow the Money Trail

Each year, Penn students shell out tens of thousands in tuition money and remain shackled to the ever–treacherous two–year on–campus living and dining scheme. But that’s not all we spend our money on. Street knows well that the bleak reality of a Penn student can only be soothed by the sweet embrace of a $7–15 daily treat— or two. Feel no shame, take no blame—we too have had our wallets run dry at the Walnut Street CVS, Lyn’s food cart, and Saxby’s 6-dollar cold brews. In honor of this month’s money issue, one of Street’s writers chronicled their daily purchases in a tell–all money diary.

12:00 favor Treat 20 dollars—it's 3:00 ing the and a ractions items of ories. 7:00 p.m. aff matoair—whip sauce and it saves

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 18

DAY TWO: TERAKAWA TUESDAY

Day THREE: Workout wifey WEDNESday

8:00 a.m. — Hit the snooze bu on a few too many times and miss breakfast at home. Grab a quick bite at Saxyby’s again—another bagel and macchiato combo sets me back 15 dollars. Starting to wonder if this habit is sustainable.

12:30 p.m. — Lunchtime rolls around, and I'm craving something different. Decided to treat myself to sushi from Maki—a salmon avocado roll for eight dollars. Not that bad. It's a good change from McClelland sushi.

3:00 p.m. — Feeling sluggish after lunch, so I swing by the campus gym to check out their classes. Sign up for a trial session of yoga—it's free, so why not?

12:00 p.m. — of a late brunch at a trendy café downtown. myself to avocado toast and a fancy la e for dollars—it's the perfect start to the weekend.

p.m. — Spend the afternoon explor- city with friends, stopping at various shops ractions along the way. Splurge on a few new of clothing, but it's worth it for the fun memp.m. — Dinner tonight is a homemade air—whip up a batch of pasta with pesto and to- sauce from ACME. It's simple but satisfying, saves me from spending money on takeout.

Day FOUR: Tightening the belt THURSDAY 9:00 a.m. — Feeling ambitious; I decided to kickstart my day with a morning run. Realize I don't have running shoes, so I splurge on a new pair from Adidas (on sale for 54 dollars). It's an investment, right?

12:00 p.m. — Opt for a homemade lunch to-

5:00 p.m. — It's been a long day, so I treat myselftobobateafromGongChaonmywayhome. Indulge in a passion fruit yogurt with tapioca pearls for eight dollars—the perfect pick–me–up (kinda expensive though).

day to save some cash. Whip up a simple salad withingredientsfromthefridge—it'snotthemostexciting meal, but it gets the job done.

10:00 a.m. — Needed to get an extra large Dunkin' coffee before my art history recitation. Here’s to an excruciating one hour.

2:00 p.m. — Spend the afternoon catching up on readings and chores around the house. It's not the most exciting way to spend a Friday, but it's satisfying to check things off my to–do list.

6:00 p.m. — Dinner tonight is a Philly cheesesteak at Greek Lady. It’s huge, so the 14–dollar price makes sense. If you’re not that hungry, the halal cart in front of Gregory College House is the best.

19 DECEMBER 2023

10:00 a.m. — Spring break is coming. My boyfriend and I have zero plans. Had a psychotic crisis and decided to go to the most expensive place on earth. Yes, you got it right if you said Disneyland. Splurge on park tickets, car rental, Airbnb, and airfare. Disney adults, here I come.

I am broke now.

I would rather become a stripper than sell out in the way Vivek Ramaswamy has.

34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 20

springfield distributor beer Post finals pre game CALLS FOR A We’ve got THE BEER FOR your holiday party! Get beer delivered for ST. PAT’S DAY PARTIES 40th & Spruce St., University City • 215-382-1330 • copauc.com WEDNESDAYS 1/2 PRICE BURGERS 11:30AM - 4PM SATURDAY & SUNDAY BRUNCH 11:30AM - 3PM BLOODY MARYS 40th&SpruceSt.,UniversityCity•215-382-1330•copauc.com

Pu ing Money Where Your Mic is: Grooves About Greenbacks

In the tumult of midterm season (which is to say, anytime after the second week of classes) Penn students need motivation. What be er way to fuel a study session or shift at work than with music pointing toward the ultimate end goal? According to some, it’s not love—Valentine’s Day is over.

`

“Money” — Pink Floyd

One of many songs to proudly inherit from your dad’s music taste, “Money” starts with a unique in-

tro: literally, the sound of money. After the distinctive sound of an old cash register comes a splicing ofingnoises,includingtheclinkofshinycoinsandthetearof paper. They make up a seven–part loop that gradually melts into one of the best basslines in ‘70s rock. Then the song’s lyrics come in, satirizing theitylifestylesoftheobscenelyrich.“I’minthehigh–fidelfirst–class traveling section / And I think I need a

Lear jet,” David Gilmour sings.The best line,though, might come near the end: “Money / So they say / Is

the root of all evil today,” it declares. “But if you ask

for a rise / It’s no surprise that they’re giving none away.” In true Pink Floyd fashion, add in about three minutes of instrumental—saxophone and guitar so-

los delivered by Dick Parry and Gilmour, respectively—and you’ve gotyourself a classic.

Street’s curated list of five of the best songs about money—a penny for our thoughts.

BY JULIA FISCHER GRAPHIC BY INSIA HAQUE

Not altruism either: “Changing the world” is much harder than your college admissions essays might’ve assumed. The answer is cold, hard cash—but not according to all of these tracks, which provide a variety of outlooks. All that gli ers is not gold, but these songs sure are.

` “Money Trees” — Kendrick Lamar, Jay Rock

We encounter another iconic loop in Kendrick Lamar’s 2012 hit “Money Trees,” with one of the most creative uses of a sample you’ll ever hear. The otherworldly instrumentation that repeats throughout the track is a snippet of alternative band Beach House’s "Silver Soul." Producer Dahi reversed the sample and addeddrumstoittocreateastellarmotifthatrepeats throughout the track. In terms of the song’s storyline, though, “Money Trees” couldn’t be more different from “Money.” In contrast to the nameless one–percenter protagonist in Pink Floyd’s lyrics, Lamar raps about growing up in poverty in Compton, Calif. He discusses “dreams of living life like rappers do,” even while tempted by the temporary payout—emotional and financial—of sex, drugs, and crime. Economic stability is elusive, gang violence abounds, and the phrase “ya bish” is all too catchy. Money might not grow on trees, but young Kendrick was determined to plant his own and turn his circumstances around. “Money trees is the perfect place for shade,” Lamar sings, “And that’s just how I feel.”

MUSIC

"Can’t Buy Me Love" — The Beatles

Ah, The Beatles, with their mop–top bowl cuts, awk- ward grins, and starstruck crowds of fangirls. "Can't Buy Me Love" is a short but sweet tune off their 1964 albumAHardDay’sNight , combining catchy chorus- es with punchy drums and guitar. For a band aimed at worldwide success, Paul, John, George, and Ringo express a surprising detachment from material riches. With the realization that you can’t purchase a re- lationship at the local five and dime, cash becomes extremely expendable: “I’ll buy you a diamond ring my friend / If it makes you feel alright.” It’s easy to understand the track’s romantic appeal, as it places love above all else; “I may not have a lot to give / But what I got, I’ll give to you,” Paul McCartney sings. (Later on, looking back on The Beatles’ vacation in Miami after their first American tour, he would joke, “It should have been ‘[Money] Can Buy Me Love,’ actually.”) Regardless, once you know the words, it’s a song that bounces around your head for hours … and you’re not upset about it.

“Money, Money, Money” — ABBA

“Money, Money, Money” is ABBA's contemplation on the merits of becoming a trophy wife. What else is a girl expected to do in “a rich man’s world”? The piano and synthesizer that dominate the sound create a sense of drama, and the song is as much a relatable rant as it is the pinnacle of disco pop. Any college student can empathize with working hard, paying the bills, and in the end, as Anni–Frid Lyngstad sings, feeling “there never seems to be / A single penny left for me” (first years, if this doesn’t strike a chord yet, just wait). Taking into account that it wasn’t until 1974, just two years before this song’s release, that women in the United States gained the right to open a bank account on their own, “Money, Money, Money” is more than just a would–be gold digger’s anthem. “Ain’t it sad?”

Bills"

—

ABBA’sdebateonragsandrichesfindsadetermined and sassy answer, courtesy of legendary girl group Destiny’sChild.On"Bills,Bills,Bills,"welistentothe taleofawomanwhoseboyfriendisabittoocomfortableafterthehoneymoonphaseatthestartoftheir relationship and is starting to take far more than he gives.He’sprovinghe’s“ascrub…/Whodon’tknow what a man’s about.” What are they saying a man’s about? Earning money, or at the very least being dependable.The lush vocal harmonies that abound on the track—especially on the “so” in “so, you and me are through”—are so good we’re convinced the girlfriendmeansbusiness.Andofcourse,thesnappy lyricism hits its peakwith a greatpun:“Canyou pay mybills?/Canyoupaymytelephonebills?/Doyou paymyautomo’bills?”Iftheanswerstothesequestionsareno…Destiny’sChildhasbadnewsforyour romance,andgoodnewsforyourwallet.

“Million Dollar Man”

—

Lana Del Rey

stuffed wallet and a lover who “look[s] like a million dollar man,” Del Reyteaches us there are other, more devastating ways to be bankrupt.The masterof double meanings still sings, “Why is my heart broke?”

`

`

Finally, we have the tenth track on Lana Del Rey’s debut major–label album, BorntoDie—a grandiose ode to a “Million Dollar Man.” The song is relatively slow in terms of tempo, but Del Rey’s low vocals, matched with jazzy piano and sweeping violin, build to a chorus that’s as heartwrenching as it is cinematic, especially near the three–minute mark. The lyrics describe a relationship that, on the surface, seems glamorous and easilylives up to the standards we received from Destiny’s Child. Del Rey is with this man for two main reasons. In a reference to Elvis Presley’s cover of “Blue Suede Shoes,” it’s “one for the money / and two for the show”—which is to say, for his wealth and for the thrill. But the man she describes is “dangerous, tainted and flawed.” “You’ve got the world, but baby, at what price?” she asks, suggesting that money isn’t everything. As nice as it is to have a 34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 22

` "Bills, Bills,

Destiny’s Child

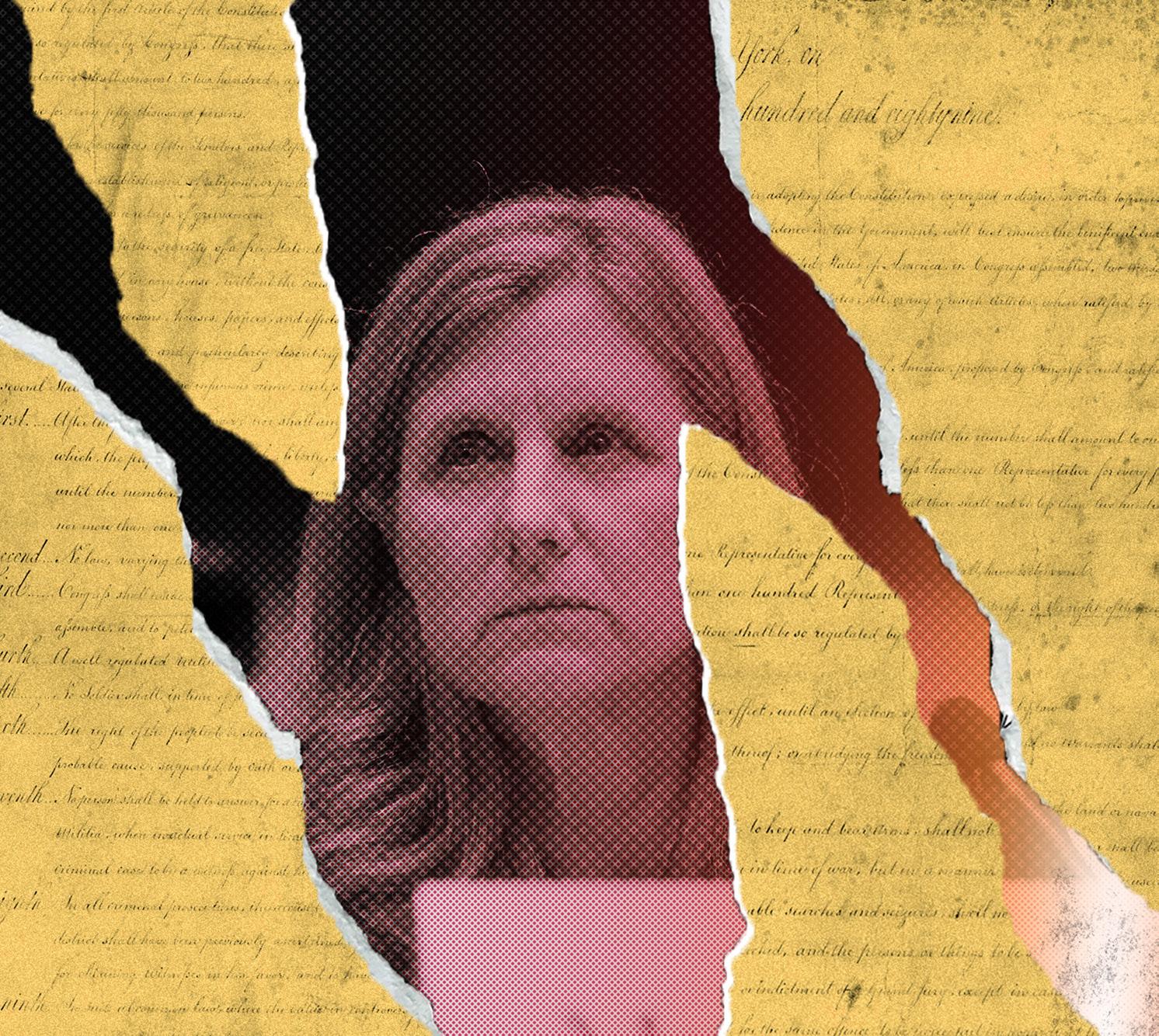

FEATURE

Donors Rule Everything Around Me

When money talks, professors are silenced

BY HANNAH SUNG AND JULES LINGENFELTER

GRAPHICS BY EMMI WU

Early in the morning on June 16, 1915, professor Sco Nearing received notice of his dismissal from Penn. “As the term of your appointment as assistant professor of economics for 1914–1915 is about to expire,” disclosed the le er from the Provost, “I am directed by the trustees of the University of Pennsylvania to inform you that it will not be renewed."

Nearing, in his autobiography, wrote, “I was fired without previous notice, without charges, without a hearing, without recourse, from a job I held for nine years.” His crime? Expressing anti–Capitalist sentiments and ad-

vocating for child labor laws. Penn fired the popular professor, whose lectures garnered the largest enrollment in any class at the time.

Penn's Board of Trustees at the time—which included bankers, corporation lawyers, and a partner at J.P. Morgan—had been troubled by the economist’s research. The Wharton School alumni commi ee insisted on firing faculty members who “tended to arouse class prejudice,” including Nearing, who they claimed reached “fallacious conclusions.” Nearing’s dismissal impacted the role of tenure at Penn and spurred nationwide debates surrounding free speech.

$$$$$

Over a century after Nearing’s expulsion, the state of academic freedom at Penn remains tenuous.

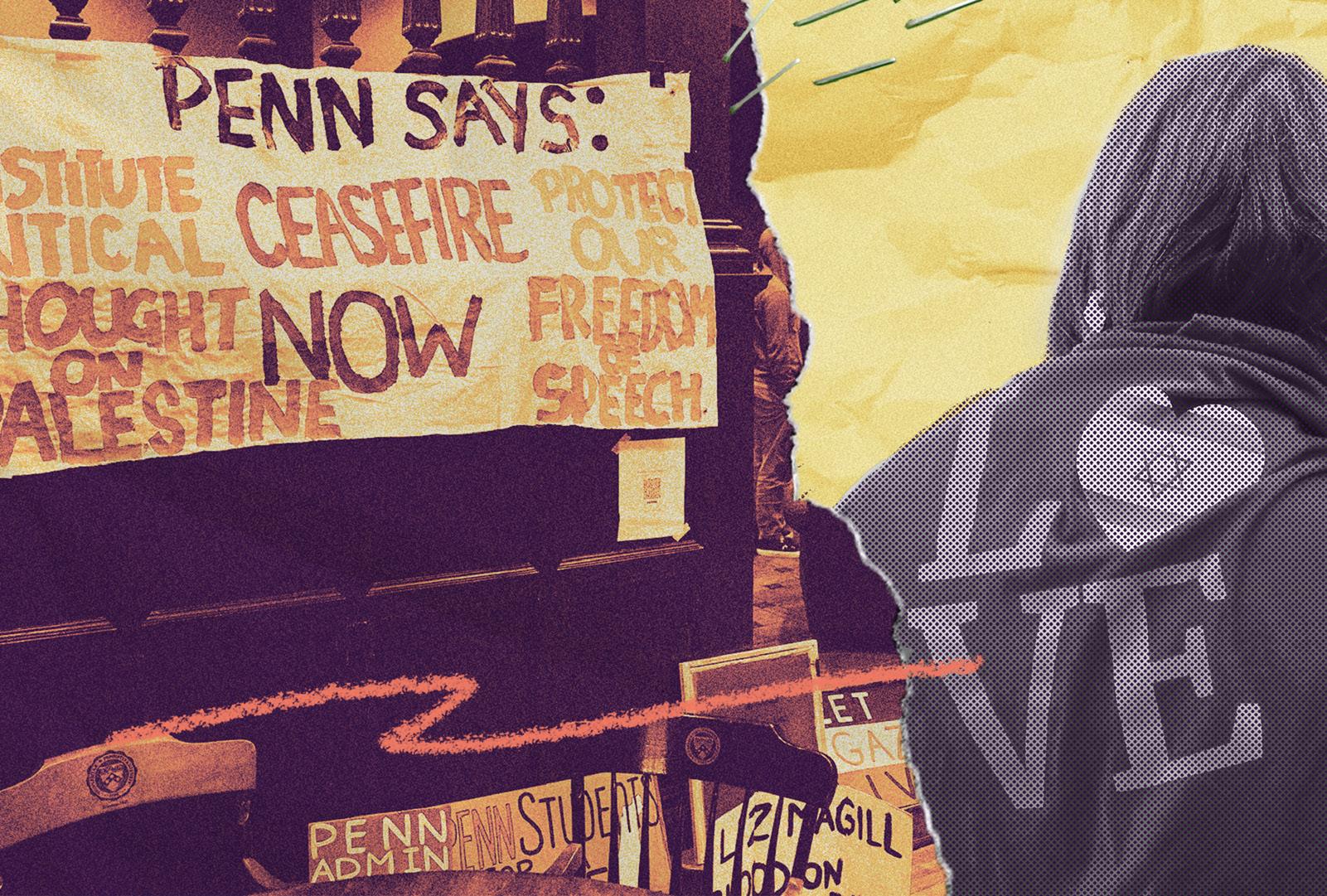

The spotlight on Penn began in late September 2023 with the Palestine Writes Literature Festival controversy and immediate backlash from donors. Tensions further escalated after the Oct. 7 Hamas a acks, the ensuing war, and former Penn President Liz Magill’s highly publicized response. In a series of statements, Magill sought to appease students, alumni, and donor concerns regarding rising antisemitism on

23 MARCH 2024

campus. Her wavering response was deemed insufficient by Penn donors, many of whom withdrew funding and called for Magill and former University Board of Trustees Chair Sco Bok to resign.

Beyond Penn, the national scrutiny surrounding claims of rising antisemitism on college campuses mounted an investigation by the United States House Commi ee on Education and Workforce. Magill testified in front of the commi ee on Dec. 5, 2023. Following a widely–circulated clip, Magill was criticized for her responses to questioning by Rep. Elise Stefanik (R–N.Y.), who asked if individuals who call for the genocide of Jewish people violate Penn’s policies or code of conduct. Magill called it a “context–dependent decision.” Soon after the hearing, on Dec. 9, Magill and Bok resigned from their respective positions.

Magill’s resignation and the events of last fall have placed Penn at the forefront of debates about University and donor–led threats to academic freedom. For example, Penn initially denied progressive Jewish student group Penn Chavurah's request to screen the movie Israelism on Nov. 28, 2023. Just over a month before that, 1965 Wharton graduate Ronald Lauder wrote to Magill demanding that no students at the Lauder Institute be taught by any instructors who were involved or supported the Palestine Writes Literature Festival. But these free speech conflicts didn’t end after Magill’s resignation.

$$$$$

On Feb. 1, Annenberg School for Communication lecturer Dwayne Booth, who publishes political cartoons under the name Mr. Fish, came under fire for a series of highly controversial images intended to criticize the Israeli government. The public a ention “started when the Washington Free Beacon released an article accusing me of antisemitism,” he explains.

Despite the comics being published months earlier, Interim Penn President Larry Jameson did not release a statement regarding Fish’s work until after the Washington Free Beacon’s accusations against the political cartoonist. Jameson condemned the cartoons, describing them as “reprehensible, with antisemitic symbols, and incongruent with our efforts to fight

hate,” further stating that they “do not reflect the views of the University of Pennsylvania, or me personally.” Jameson’s prompt response comes among Penn’s many efforts to rehabilitate its public image, reflecting a pivot from Magill’s past six months of turmoil on campus.

Fish has been teaching at Penn for ten years and creating political cartoons since the ‘90s; he’s dealt with criticism—and hate—for most of his art career. But this latest incident is the first time his artistic work has elicited a response from the institution. Even if his art is extracurricular, it is now being characterized as a representation of Penn as an institution. Fish acknowledges that the reaction his work has garnered no longer affects just him.

“[Jameson] released his statement, unfortunately giving a certain amount of credibility to the Washington Free Beacon’s assessment of my work,” Fish says. “These were misstatements because they’re just inaccurate and tend to justify the shu ing down of voices rather

than the expansion of conversations and debate, which is what should be happening on college campuses.”

Despite Jameson’s highly public statement, Fish reports receiving support from students, alumni, and his colleagues at Annenberg. Although Fish has found himself in a complicated situation, he admits that it’s exactly what he is trying to teach his students. “It’s the subject of our conversation in class: How provocative artist communication can be and how it can be misconstrued to be something else. So when this broke, it’s a real–life organic example of stuff we’ve been talking about theoretically. The class is really thrilled,” he says.

However, the condemnations of Fish run deeper than Jameson’s statements; Fish has since received death threats and calls for resignation. He even chose to move one of his classes temporarily online after its time and location were made public, fearing for both his and his students’ safety. While Fish has not received

PRINT // LEGACY 34 TH STREET MAGAZINE 24

any disciplinary action, he believes Annenberg would be willing to support him. But the controversy that has erupted around his work—or rather, the threats he’s received in response to his work—threatens the intellectual and physical safety of Penn students and faculty.

Following the a acks on Fish, the Penn chapter of the American Association of University Professors released a statement condemning both the “targeted harassment of Annenberg faculty Dwayne Booth” and “Interim President Jameson’s dangerous and unwarranted response,” citing both as threats to academic freedom. AAUP–Penn pointed to the University’s own handbook, which protects extramural speech of all faculty, and that any disciplinary action towards Fish would result in the justification of a formal investigation by the group.

The AAUP’s stance on the ma er was clear: “The fundamental duty of the university administration in a time of war and political conflict is to protect academic freedom.”

$$$$$

The AAUP has a long history with academic freedom. The association was founded in 1915, the same year as Nearing’s firing; 32 of its charter members were Penn faculty. The forces that fired Nearing and led to the formation of the advocacy group are the same forces at work targeting Fish—donors, politicians, and the public that read fear mongering accounts of campus

melee.

In the decades following Nearing’s dismissal, events such as the Second Red Scare took hold of college campuses. Around a hundred professorships were terminated in the mid–20th century in the wake of the Scare. Political subversives that caused mass hysteria have been and continue to be a recurring phenomenon, even over 100 years after Nearing’s firing.

Have we dawned on a new era of censorship? According to the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, a.k.a. FIRE, we just might have. Greg Lukianoff, current president and CEO of FIRE, states on FIRE’s website that there have been over “1,000 campaigns to get professors punished” by their adversaries in the past decade; almost one–fifth succeeded in ge ing them fired, which is noted to be “nearly twice the number estimated for the Red Scare.”

FIRE claims to be unflinchingly nonpartisan, not who is “right or wrong.” They have explicitly refrained from taking a position on the Israel–Palestine conflict. However, the organization recently stated, “FIRE has been troubled to see some college leaders react to protected speech and peaceful protests with calls to prohibit speech they view as inflammatory or even to ban student groups because of their viewpoints.”

Joseph Cohn, a University of Pennsylvania Carey Law and Fels Institute of Government alumnus, worked for FIRE as its previous legislative and policy director for the past 12 years until

he began his bid for Congress in New Jersey’s third congressional district this past December. While at FIRE, Cohn noticed an alarming spike in people contacting the nonprofit regarding freedom of speech and academic freedom on campuses.

In the past, students would be up in arms and at each other's throats, but their main enemy was the man—the man being the administration. “Students would rally behind all students, even if they were their political adversaries, if the administration tried to shut them up, being a collective force for each other,” Cohn says. But in the last decade, students have been vying for administrators to join their side of the fight and punish their opposition. The implications of this development are concerning—by stifling conversation, these conflicts become a pissing contest beyond solely debate, inviting money and political influence into the equation.

As a private institution, Penn is not constitutionally protected by the First Amendment. But, thanks to Penn’s wri en policies in the Faculty Handbook and Pennbook, this liberty is still afforded to us. In theory, these rights are protected for students and faculty, but recent events have raised doubts over their validity in practice.

$$$$$

The combined effect of recent turmoil on Penn’s campus and pressure from donors has mounted fears for academic freedom inside and outside the classroom.

Following the University’s initial response to the Palestine Writes Literature Festival and the Oct. 7 Hamas a acks, the Chairman of the Board of Advisors of the Wharton School and Penn alumnus Marc Rowan published what became one of the most publicly stated funding withdrawals in an open le er: “I call on all UPenn alumni and supporters who believe we are heading in the wrong direction to ‘Close their Checkbooks’ until Magill and Chair Sco Bok resign,” Rowan published on Oct. 14, 2023. Rowan’s call to action triggered similar donor withdrawals from notable Penn alumni, like Jon Huntsman Jr. and Ronald Lauder.

“There’s this enormous gap between what the world thinks Penn is like—or what the world is coming to think—and what actually is the case,” says Ian Lustick, Professor Emeritus and Bess W. Heyman Chair in the Political

25 MARCH 2024

Science Department at Penn. He’s taught a course on the history of Israel and Palestine at various universities for decades, including this past fall semester at Penn. Amid the controversies on campus, Lustick and his students found themselves thrust into a real–time analysis of the events. “There was not a single moment of distress in the class or tension, but there was intense discussion and questioning.”

There was, however, a dissonance between the experience Lustick describes within the classroom, and the one privy to the public. “While these students reported that there were tensions on campus, they did not report feeling afraid or unsafe. But what they did say is that they were receiving frantic phone calls from family members, journalists, and friends at other universities, who had formed an impression that things were absolutely haywire when it came to this,” he says.

The severity of the situation lies in donors’ a empts to further increase their power and control over how our academic institution operates. “This is not about somebody who has some money and won't give $50,000 if their son doesn’t get accepted into the University,” Lustick says. “We’re talking about demands for the disciplining of masses of students, demands for the adoption of a particular catechism on a very important issue, for the ve ing of syllabi, for control over hiring decisions, and over the creation and destruction of particular departments. This is absolutely beyond the pale.”

There seems to be a conflation between money and power, and the role of donors has further distorted that dynamic in the last six months. Penn is not isolated from market forces.

What happened last semester shows the direct consequences of when money is weaponized within the academic sphere. When universities place donors’ demands above their mission to promote academic freedom, the integrity of our learning institution is compromised.

What happened last semester shows the direct consequences of when money is weaponized within the academic sphere.

Lustick echoes FIRE’s sentiment and believes that we are on a new Red Scare era. “I would compare the pressures that people are under to McCarthy’s period in the ‘50s in the United States,” he says. “People went into hiding, essentially intellectually, and their careers suffered. That’s the kind of situation which we’re now facing.”

In reaction to Fish’s political cartoons, Lustick states, “I don’t want to punish the person that I may not agree with … I don’t expect all faculty members to agree with me either about my extracurricular views, or even my curricular views. That’s not what I’m here for. I’m not here to agree with everybody.” He further argues that Fish acted within his right of freedom of speech and that any calls for resignation and disciplinary action are unjustified. For a university to function, it must be able to acknowledge the free-

dom of its participants to pursue academics without fear of consequence.

$$$$$

While faculty solidarity in cases of academic freedom is largely widespread, the AAUP and its constituent faculty have no bargaining power. Andrew Vaughan, an assistant professor for biomedical sciences at the School of Veterinary Medicine and a member of AAUP–Penn, recognizes the limitations the group has. “We're limited to trying to raise concerns and advocate for changes without any ability to actually institute those changes themselves,” he says.

Part of this advocacy involves the role of the Faculty Senate. “Over the last couple of months, I feel as though the Faculty Senate executive commi ee has really tried to step up and similarly champion the same concerns of AAUP,” Vaughan says. The Faculty Senate is Penn professors’ one avenue to have a say in University governance. The organization is only made up of tenure–track faculty, while the AAUP chapter is made up of faculty of all levels. In a statement on its website, Penn’s Faculty Senate declared solidarity across rank, especially for those “affected by recent efforts of intimidation.” The statement reads, “Let us be clear: academic freedom is an essential component of a world–class university and is not a commodity that can be bought or sold by those who seek to use their pocketbooks to shape our mission.”

There has been speculation among the Faculty Senate itself about the extent of its role. Vaughan recounts an anecdote that he heard about Faculty Senate representatives at the

PRINT // LEGACY

Board of Trustees Meetings not being allowed to speak. “We're actively trying to engage more with the Board of Trustees, and we'd like to try to get ourselves more of a seat at the table,” Vaughan says. Penn’s faculty, Vaughan adds, were blindsided by the fact that the administration can “essentially [do] whatever they like within their own bylaws. They can completely ignore any language.” When viewing Penn as a workplace, beyond an academic institution, these standards are horrific.

AAUP–Penn works to dismantle the hierarchy of faculty. The gift of camaraderie and cross–department interaction is important in any workplace—the ability to talk among employees about shared experiences and grievances, and bring these to an employer. “It’s a missed opportunity; we’re all so siloed in our own li le worlds,” Vaughan says, remarking how before AAUP, he had never interacted with anyone in other departments, like English or history.

Though Vaughan himself hasn’t been personally affected in his ability to teach, he refers to his colleagues as comrades, stating, “Have I seen it impact colleagues and professors across campus? Absolutely, and I am concerned about it.”

In December 2023, the Pennsylvania legislature halted funding to the School of Veterinary Medicine—the only state–funded veterinary school in Pennsylvania—and the Penn Medicine Division for Infectious Diseases. This decision was in response to allegations of antisemitism on campus.

“I think those of us in life sciences and medical sciences sometimes take it for granted that these outside forces aren't going to have as much influence on us,” Vaughan reflects.

This decision underscores how the reach and influence of money in academic institutions knows no bounds.

$$$$$

How did Penn get out of the McCarthy–era trenches to where it is now? To answer this, we need to look back at Nearing’s martyrdom as a cautionary tale. Free speech and academic freedom, which lend themselves to a quality education, all hinge on faculty support. Decreasing tenure provisions, denial of due processes for

some faculty, and lack of transparency from the administration affect everyone at Penn. But things don’t have to be bleak.

“The principles of free speech are evergreen,” Cohn says. “It’s easy to reject notions of free speech when you're in charge. But on a long enough timeline, those tables turn … people on the receiving end start realizing they need to have more consistent practices and policies. Most people don't accept being silenced.” Cohn a ributes a short–term worsening scenario to the pressure on the University to respond to Gaza. The lines for what is protected—speech, protests, controversial speakers on campus—and not protected—targeting groups of students, and of course violence— are blurred. “This moment will eventually pass,” Cohn assures.

As well as normalizing disagreements without fear of retribution from outside influences, supporting faculty is key. There are problematic implications in relying on contingent faculty, especially when teaching controversial topics. Strategic self–censorship becomes the norm, and job precariousness supersedes academic integrity. Penn’s administration ought to prioritize protecting faculty in exercising their autonomy in teaching and researching. Expanding the accessibility of the tenure track can guarantee both academic freedom and economic stability—something a majority of Penn’s faculty lacks.

“Trustees hold the ultimate authority to ensure colleges focus on truth–seeking, not truth–dictating,” Lukianoff writes on the FIRE website. “A top–down, father–knows–best mentality is