Through February 9

The off-season is the perfect time to prepare your boat for the adventures ahead. Whether you’re upgrading your equipment or planning for smoother sailing, there’s no better opportunity than our exclusive sale on Harken MKIV and MKIV Ocean furling systems.

For the complete line of Harken sailing hardware please visit fisheriessupply.com/harken

30 Passes of the Gulf Islands

Information for transits of these beautiful, challenging channels. By William Kelly and Anne Vipond

Still So Worth It

A family winter cruise only slightly derailed by a daycare cold.

A would-be mishap illuminates new strength and passion.

44 48° North’s Top 25 Race Boats of 2024

Cheers to these crews who sailed very well throughout the year!

18 Close to the Water: Capsize!

Developing the know-how of self-recovery through practice.

Bateau 20 Diesel Deep Dive: Raw Water Cooled Engines

Surprisingly resilient, many near the end of their operating lives. By Meredith Anderson 22 Shifting Gears: Downshifting on New Year’s Day A paddle-based exploration of the Hylebos Waterway. By Dennis Bottemiller 26 A Northwest Sailor Navigates the Past

Captivated by chasing crabs in Puget Sound. By Lisa Mighetto

42 TTPYC Duwamish Head

The 2025 racing season kicks off with a shortened course.

In any experience as varied and variable as spending time on the water, a lifetime of exploring and enjoyment awaits purely due to the richness of the endeavor, of the possibilities, and of the surroundings. Nowhere is that more true than in our extraordinary corner of the world. Being alone on a boat can offer the deepest personal connection with the natural world and your vessel. Indeed, sailors throughout history have understandably humanized their craft, honoring just such a relationship and partnership.

Venturing solo is extremely worthwhile, and such solitary journeys represent the height of desire and accomplishment for some boating enthusiasts. It certainly displays the impressive combination of a specifically self-sufficient skillset, while also embodying the most well-rounded knowledge and abilities since all facets of responsibility lie with a single person. It’s legitimately amazing. Anyone fueled by adventuring alone has my admiration and respect. Even if it’s not your main goal, there’s something absolutely magical about having a remote anchorage all to yourself, when other boats, humans, and signs of civilization are beyond the horizon or the mountains encircling you.

Still, no matter how appropriate it is to hold-up those remarkable solo voyagers, it is my unscientific but nonetheless firmly held belief that the best thing for almost everyone is to lean into the community, the society, of boat folk. It has certainly meant the world to me in tangible and intangible ways, and it delivers so much more than just warm fuzzies.

In this issue alone, we see the support and rewards of taking to the water with others. Whether that’s a very small crew like the paddling pair from the Shifting Gears column (page 22) or Lauren Upham’s family of four with two children under three years out for a New Year’s cruise (page 34); as well as the exchange of engagement, encouragement, and assistance taking place between those standing by to observe or lend a hand during a capsize drill (page 18); or among the Dancing Bear crew with such varied levels of experience but such equal passion for sailing (page 38). These are, of course, microscopic slices of the broader boating society pie, yet it all illuminates the enrichment of being part of a community. And that stuff adds up to something both special and powerful.

Then there’s the sailboat racers’ sector of our society, some of whom are recognized for their outstanding performances in this month’s Top 25 (page 44). Perhaps no segment is more dependent on one another—almost all race boats require a multi-person crew to share the endeavor, there is some (sometimes vast) outside volunteer support typically involved to put on races, and obviously racing is a game made ever-better by the participation of more fellow race boats. It’s no wonder that those who love racing sailboats tend to relish the camaraderie at least as much as the competition. The Top 25 does a great job of highlighting and celebrating the collective commitment to an activity across the wide range of boats, priorities, and people who share the water—even in that seemingly narrow pursuit.

It probably comes as no surprise that this is top of mind as we put together the issue that comes out just in time for the Seattle Boat Show—a gathering and festival of our region’s society of boat nuts past, present, and future, if ever there was one. We love the boat show, and will be there with bells on, please come visit us in booth West 3. Whether at the boat show, on the water, or in any interaction with the marvelous community of PNW boat folk, lean in—we’re all in this together and here for one another!

I’ll see you at the show and on the water,

Joe Cline Managing Editor, 48° North

Volume XLIV, Number 7, February 2025 (206) 789-7350

info@48north.com | www.48north.com

Publisher Northwest Maritime

Managing Editor Joe Cline joe@48north.com

Editor Andy Cross andy@48north.com

Designer Rainier Powers rainier@48north.com

Advertising Sales Ryan Carson ryan@48north.com

Classifieds classads48@48north.com

48° North is published as a project of Northwest Maritime in Port Townsend, WA – a 501(c)3 non-profit organization whose mission is to engage and educate people of all generations in traditional and contemporary maritime life, in a spirit of adventure and discovery.

Northwest Maritime Center: 431 Water St, Port Townsend, WA 98368 (360) 385-3628

48° North encourages letters, photographs, manuscripts, burgees, and bribes. Emailed manuscripts and high quality digital images are best!

We are not responsible for unsolicited materials. Articles express the author’s thoughts and may not reflect the opinions of the magazine. Reprinting in whole or part is expressly forbidden except by permission from the editor.

SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS FOR 2025

$39/Year For The Magazine

$100/Year For Premium (perks!) www.48north.com/subscribe for details.

Prices vary for international or first class.

Proud members:

swiftsure.org #swiftsure MAY 24 – 25, 202

• Swiftsure Lightship Classic, PHRF NW

•Cape Flattery, PHRF NW & ORC

• Ju an de Fuca, Monohull & Multihull, PHRF NW

• Inshore Course, PHRF BC

In honor of the 80th running of the Swiftsure Lightship Classic, The Skippers Meeting and 2024 Prize Giving will be held at the Royal Victoria Yacht Club, 3475 Ripon Road, Victoria, B.C., 2:00–5:00 pm, Friday May 23, 2025.

REGISTRATION OPENS

Monday, February 3 rd 2025 at swiftsure.org/ registration

48° North has been published by the nonprofit Northwest Maritime since 2018. We are continually amazed and inspired by the important work of our colleagues and organization, and dedicate this page to sharing more about these activities with you.

by Heather J.

Are you ready to push your limits or just explore? Northwest Maritime has a variety of events that promise to test your grit and determination while also enjoying our beautiful waterways. Choose your own adventure. Application windows are open for the following:

WA360 Covering a 360(ish)-mile loop from Port Townsend to Port Townsend, the WA360 race course threads through Washington’s waterways, bringing you within reach of dozens of PNW communities. With no room for slacking, you’ll face diverse conditions—big summer squalls, commercial traffic, ripping currents, and windless doldrums. Anything that floats and abides by maritime law is eligible, so whether it’s a sailboat, paddle craft, or a garage creation, it’s welcome in WA360.

SEVENTY48 Created in 2018, SEVENTY48 is a human-powered, 70-mile race from Tacoma to Port Townsend in 48 hours or less. The rules are simple: no motors, no support, no sails. Racers pedal, paddle, or row, pushing their physical limits to the max. Salish100 This cruise brings together a vibrant community on the water. Cruising the length of Puget Sound—100 miles from the state capital of Olympia to the Victorian seaport of Port Townsend—racers stop each day to share experiences. With an overall length limit of 22 feet, the fleet includes SUPs, SCAMPs, skiffs, Whitehalls, wherries, sharpies, melonseeds, and every conceivable type of home-built sail and rowing vessel.

» nwmaritime.org/nwmc-events/races-cruises NEW CLASS SPOTLIGHT: INTRODUCTION TO FISHING THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST, TWO-PART, IN-PERSON, FEBRUARY 8 AND 22

Attention current and future anglers! Join a new, indepth six-hour saltwater fishing course focused on catching salmon, halibut, and crab in the Northwest, split into two three-hour sessions. This class is designed for those fishing from their boat (or a friend’s) and covers essential tackle, techniques, and the best times and places to maximize your catch.

Led by Captain Don Dybeck, a seasoned fisherman with over 50 years of local experience, this class includes hands-on instruction, valuable tactics, and plenty of entertaining fish stories. It will also cover crucial boat safety tips, including a memorable lesson on what not to do. This course has no prerequisites and is thus perfect for beginners, but even seasoned anglers are sure to pick up new tips and tricks! The class takes place at the Northwest Maritime Campus in Port Townsend. » nwmaritime.org/events/intro-fishing-pnw-2025/

“I can plot courses on paper charts, identify latitude and longitude on a chart and explain the difference. I know the vessel rights of way hierarchy relating to the rules of the road, and can calculate tides and currents and proficiently use the VHF radio.”

– Forrest Cox, Junior, PTMA.

During their navigation unit, Port Townsend Maritime Academy (PTMA) students gain a comprehensive understanding of foundational marine navigation skills and techniques. The unit aims to provide students with an overview of subjects covered by the USCG OUPV and 100-ton Master Captain License Course. This includes learning to calculate speed, time, and distance; determine compass error; and navigate using electronic and paper charting systems. Students also learn the basics of route planning, including planning for tidal currents and variable weather conditions. This year, students learned about diverse navigation methods, such as celestial navigation, and wayfinding techniques used by indigenous cultures.

» nwmaritime.org/learn/career-training/ port-townsend-maritime-academy/

Based out of beautiful Anacortes, Washington, we offer a complete range of ASA courses from Basic Keelboat 101 through Advanced Coastal Cruising 106, Cruising Catamaran 114, Docking Endorsement 118, and private instruction.

Call us now to register for our spring 2025 ASA IQC - Instructor Qualification Clinic! Space available in our ASA 201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206 and 218 clinics. www.sailtime.com/location/anacortes/sailing-school

Pay online for courses through the 2025 season. Book Now! Courses are filling up fast! Call us at 206-351-8661 if you want to talk about your sailing future!

719 28th Street

Anacortes, Washington 206-351-8661

Response to the Response to “Art of the Oil Change” from the December 2024 Issue

Last month, a reader wrote in with a thoughtful response adding some ideas to Meredith’s column about oil changes. This month, Meredith responded with some insight:

Hi David and Joe,

I read your comments and you are absolutely right on all of them. One of the struggles I have when writing an article like this is being able to include as many steps or details as I might like, since the articles are somewhat limited in space and I have to stay relatively broad for everyone who may read it.

Things like running the engine and paying attention to amount of oil remaining are details that apply to everyone and are great additions! In my experience, the mounting angles are usually not so dramatic that people have to worry too much about whether to fill above/below their top lines to account for the rake of the engine.

A boat owner with a DIY spirit can become very wellversed with the details that are specific to their engine, but I’m cautious about adding details that could create confusion or concern for folks who are considering applying this information on their own boat. An example might be changing the oil on a Ford Lehman injection pump—very few engines actually have a separate oil reservoir for their injection pumps—and if I mention it, I can guarantee that people will be calling to ask me if their injection pump on their Yanmar needs its oil changed as well! Each engine has its own quirks.

One idea for you, Joe, is if I were to write articles for certain popular engines, I can get more specific about the good/bad and talk about more details? Thanks for reaching out, and for your ideas and feedback, David.

Sincerely, Meredith Anderson

Cruising and Cruising Class Racing

Hey Joe,

I took my family cruising to the San Juan Islands last summer on my 27-foot Catalina that’s as old as I am—two teenagers and my wife. It’s pretty cool reading articles from other folks I know, and I have written about it and would love to contribute and share with our community.

Also here’s a picture from the Duwamish Head Race after we left the Cruising fleet in a hole and led the pack past Three Tree. Best decision I ever made was registering in the cruising class to get that 30 minute head start!

Gerry Austin, Emerald Lady

Boaters throughout the region cherish the Southern Resident killer whales and celebrate the chance to see them. New regulations are now in place to better protect these extraordinary animals.

There’s plenty to read and digest on this topic, but the basics are pretty straightforward. The big change is based on legislation signed into law in 2023 that took effect in January 2025—the standard regulation is now that boaters must stay 1,000 yards (approximately .5 nautical miles) from Southern Resident killer whales. It’s important for boaters to understand the differences between American laws and the Canadian laws (400 meters), so check out the resources from Be Whale Wise—a long-running partnership between governmental agencies, non-profits, and other stakeholders in British Columbia and Washington. Here’s the gist of Washington’s new “mandatory measures” that are now law, from Be Whale Wise:

In the US, Southern Resident killer whales (SRKW) are listed as Endangered under the Endangered Species Act. In 2023, Washington’s Governor Jay Inslee signed into law new regulations governing whale watching in the State of Washington. Federal regulations also still apply to all killer whales in the inland waters of Washington state.

Corinthian Yacht Club of Seattle is once again bringing together a slate of speakers that will be as educational as they are entertaining. There's a social hour and charcuterie potluck at 6:00 p.m. followed by the program running from 7:00 to 9:00 p.m. each Friday. These free events are located at the CYC clubhouse and registration is encouraged. Here’s the lineup:

FISH ON! TIPS AND TRICKS FOR FISHING FROM YOUR SAILBOAT

February 7, 2025, Scott & Karen Tobiason, S/V Tuuli

Fishing from a sailboat presents unique challenges, but it’s easy to do and you can start catching more with a few good tips.

PACIFIC CUP 2024 1ST PLACE DOUBLEHANDED TEAM

February 14, 2025, Taylor Jooston and David Rogers

Months of boat prep, practice, and logistics culminated in a 12 day, 2,400 mile adventure with plenty of ups and downs.

KEEPING IT FUN WHILE CRUISING WITH A 7- AND 9-YEAR-OLD

February 21, 2025, Joe Grieser and Lindsay King

Joe and Lindsay will share how they balance between adventure and family bonding while cruising.

BAHAMAS CRUISING: SEALIFE AND THE SEA LIFE

February 28, 2025, Allen and Norma Goldstein, S/V Afterglow

The story of three unforgettable months in the Bahamas, experiencing the beauty and culture of the country.

» www.cycseattle.org

• Boaters must stay 1,000 yards* from Southern Resident killer whales.

• Boaters must go slow (<7 knots) within ½ mile of Southern Resident killer whales.

• Boaters must disengage engine(s) if Southern Resident killer whales appear within 400 yards.

• Boaters must stay 200 yards from other killer whales (Bigg’s/ Transient killer whales).

• Boaters must not park in the path within 400 yards of other killer whales (Bigg’s/Transient killer whales)

*There are some areas in the Salish Sea where navigable channels are narrower than 1,000 yards. If you encounter Southern Resident killer whales and you are greater than 400 yards away from the whales, you can motor slowly (under 7 knots) away and out of their path of travel. If you are closer than 400 yards, you must disengage your engine(s) and wait for the whales to pass.

» www.bewhalewise.org

Here are a couple of updates to the printed SARC. Reminder: we update the information as it comes in at 48north.com/sarc

• ADDED: Lopez Island YC Lopez Cup, September 13, 2025

• REMOVED: CYCS US Sailing Junior Women's Singlehanded Championship, June 18-22, 2025

» www.48north.com/sarc

Marine Servicenter is thrilled to have Bryan Rhodes joining their professional sales team in the Seattle office. Bryan brings 40+ years of yachting experience, holds a USCG 100 Ton license, and is a certified US Sailing instructor. He races locally on a TP52 and J/70, and lives with his wife aboard a Hanse 455. Bryan was the PNW Service Manager at Marine Servicenter from 2020 - 2021 and is excited to return to the business in a sales role. He already knows the new boats Marine Servicenter sells and services very well. His previous careers in e-commerce and real estate marketing trained an eye for details that will be beneficial for clients both buying and selling.

» www.marinesc.com, bryan@marinesc.com

The Seattle Boat Show is upon us, which means there’s a new lineup of FREE educational seminars for boaters of all stripes to enjoy—150, to be exact! With seminars on favorite destinations, safety, technology, cruising, fishing and more, this year’s show promises something for everyone ready to level-up their nautical knowledge.

The show runs from January 31 through February 8, 2025, and all seminars and panels will take place at the Lumen Field Event Center location. For a full list of seminars, visit SeattleBoatShow.com/seminars

Here are some that we’re looking forward to.

FIRST AID AFLOAT: PRACTICAL TIPS FOR EVERY BOATER BY JOHN TAUSSIG

1:00 p.m. Friday, January 31: Stage #1

Learn how to handle common injuries and illnesses on the water, and discover the must-have items and utility for a wellequipped marine first aid kit. Be prepared for any situation with practical demonstrations and expert advice.

CRUISING TODAY: PANEL DISCUSSION BY SARAH AND WILL CURRY

11:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. Saturday, February 1: Stage #1

Learn, laugh, and be inspired with active sailors/adventurers. Topics will include modern communications to heavy weather to life changing landfalls, and much more.

PREPARING YOUR SAILBOAT FOR A MULTI-YEAR CRUISE BY GIO AND JULIE CAPPELLI

1:00 p.m. Sunday, February 2: Stage #1

Learn how to keep water out, people in, and sails full. They’ll cover key vessel systems, priority refit upgrades, and outfitting tips to ensure years of successful cruising.

SOLAR POWER FOR YOUR BOAT BY MIKE REESE

3:00 p.m. Tuesday, February 4: Stage #1

An informative discussion covering the types and sizing of solar panels, mounting solutions for sailboats and powerboats, proper wiring techniques, and integrating solar panels into your boat’s electrical system.

ENGINE INSPECTIONS AND SURVEYS BY MEREDITH ANDERSON

2:15 p.m. Wednesday, February 5: Stage #2

48° North columnist Meredith Anderson will walk you through what to check when buying a new vessel with a diesel engine, including what you do and don’t want to see.

DUNGENESS CRABBING CURRICULUM BY THOMAS NELSON

3:00 p.m. Wednesday, February 5: Stage #3

Learn how to catch the quintessential Pacific Northwest dinner! This seminar will run you through the times, tides, baits, depths, lines, pots, and gear that will have you getting “crabby” in no time.

BEST PRACTICES FOR STAYING CONNECTED TO THE INTERNET WHILE CRUISING BY DOUG MILLER

4:15 p.m. Thursday, February 6: Stage #2

Sifting through the many options for staying connected including long term cost, power consumption, antenna placement, data plans, and more. This seminar will look at the pros and cons of some of the most popular solutions and provide tips for building the best setup for your boat and crew.

CIRCUMNAVIGATING THE OLYMPIC PENINSULA BY ROWBOAT BY JORDAN HANSSEN

5:15 p.m. Thursday, February 6: Stage #2

Hear captivating stories about exploring the beautiful marine waterways of Puget Sound by rowboat. Discover the hidden gems and breathtaking sights you can experience right in your own backyard, all from the unique perspective of a rower. Adventure awaits, close to home!

CRUISING THE INSIDE PASSAGE FROM B.C. TO ALASKA BY WENDY HINMAN

2:00 p.m. Friday, February 7: Stage #1

Get a taste for the possibilities and how to make the most of the time you have to enjoy the glaciers, waterfalls, and hot springs; as well as wildlife including whales, bears, otters and more; and a native culture like no other place offers.

EXPERIENCE THE MAGIC OF HAIDA GWAII BY KEN PARKER

12:00 p.m. Saturday, February 8: Stage #1

Hear insights and stories on the rich culture and history of the Haida Nation, along with practical tips, tricks, and stories about the incredible wildlife and the amazing people who call Haida Gwaii home.

ADVENTURE CURIOUS?

Gig Harbor Boat Works has some of the more unique adventure-ready offerings at the boat show. Each afternoon of the show, the knowledgeable crew will offer demos showing attendees how to rig Gig Harbor's sloop and lug rigged sailing vessels, and use their sliding rowing seats in booth West Hall #37 (check ghboats.com for the schedule). If smaller boat cruising appeals to you, these demos get you one step closer.

by Bryan Henry

Some fish, such as anchovies, eat the eggs of their own species.

Sponges and some corals can regenerate if broken into pieces.

Sea sponges can remove as much as 95 percent of the bacteria from the water that circulates through it.

Using their echolocation, dolphins can find fish buried in sand and dig them up.

The Kemp’s ridley, the rarest and smallest of the sea turtles, was named in 1880 for Richard Kemp, a Key West, Florida, fisherman who supplied specimens to Harvard University.

An estimated 1,600 species of starfish inhabit the world’s oceans.

1 Compass housing on a ship

5 Pleasant and clear, as weather

8 Melancholy

9 Ocean motions

10 Large deer species

11 May honoree

13 Ship’s ropes and chains

15 White wading bird

16 Period of duty on a ship

20 Shallow areas

22 Trial period

23 Peach state, abbr.

24 Relating to the sea

26 NFL score, abbr.

29 Warning or guiding lights

30 Lowest deck on old warships

33 Compass point, abbr.

34 Curl over and fall apart, as waves

35 Spotted from the crows nest perhaps

1 Front part of a ship

2 Steer or direct a vessel

3 Coolers, briefly

4 Sheltered side of a ship

5 Musical scale note

6 High-ranking naval officer

7 Distant

8 It’s the intro to every Outlander TV series episode, 3 words

12 Twin cities state, abbr.

13 Propel a boat with oars

14 Modern navigational system, abbr.

17 Subside, as a storm for example

18 Connecticut, for short

19 Suspended sleeping net

21 Observe

25 Comes in, as a tide

27 Be bold

28 Moved quickly

29 Float up and down on water 31 Allow 32 Single unit

» See solution on page 51

The most common starfish are the five-arm varieties, but there are species of 10, 15, and even up to 50 arms.

The Magellan penguin is the only bird that migrates by swimming.

Humboldt squid can weigh 150 pounds and measure as long as 12 feet.

Squid have three hearts—a central heart and two more that pump blood through their gills.

Some squid have as many as 35 or more patterns and camouflage changes.

Unlike most other whales and porpoises, belugas have flexible necks, enabling them to move their heads up and down and turn them from side to side.

Baby orcas don’t sleep for the first month after birth.

The bone structure of a whale's pectoral fin is strikingly similar to that of a human arm, with a shoulder blade, upper arm, elbow, wrist, and five fingers.

Because their eyeballs are fixed, whales must turn their entire body to shift their line of sight.

The melon-headed whale, pilot whale, and killer whale (orca) are all actually members of the dolphin family.

Maintaining maximum comfort while sailing is a must, which is what Gill set out to achieve when designing their new front and side zip PFD range. USCG Type III approved and available in sizes from child to XX adult large, the PFD’s overarching feature is that it provides unrestricted freedom of movement when steering, trimming lines, hiking out, or moving around on deck. The choice of front or side zip entry allows sailors to choose the best fit for their type of sailing—with dinghy sailors preferring the side zip and bigger boat sailors liking the front zip. Made with 100% nylon and PE foam, each PFD has a zipper pocket, and adjustment points at the torso and shoulders with neoprene padding. Each style is available in colors orange or steel.

Price: $99.95 » www.gillmarine.com

California-based performance instrument maker, Velocitek, recently announced the launch of their RTK Puck. A stern-mounted RTK GPS receiver, the instrument delivers racing sailors pingless distance to start, synchronized time to start, position, and heading with unprecedented accuracy. Developed with the help of the New York Yacht Club and St. Francis Yacht Club, the Velocitek RTK Puck sets a new standard for race management. The system utilizes RTK (Real-Time Kinematic) GPS technology to achieve an astonishing 1.8 cm positional accuracy—far surpassing the tolerances of conventional systems, which can vary by up to 1 meter. With wired and wireless options, the RTK Puck is versatile, reliable, and designed for events ranging from local club series to world championships.

Price: N/A » www.velocitek.com

Dreaming of summer paddling adventures? This SUP-Kayak combo might be a great new toy to get you out on the water. Isle Surf and SUP’s 11-foot-6-inch Switch is a superstable and incredibly versatile paddleboard-kayak hybrid complete package. Their patent-pending “Isle-Link” connect stem runs the length of both rails for installing the included kayak seat and footrest, or other accessories exactly where you want them. Easy to set up and use, the board weighs in at just 19 pounds, making it the lightest inflatable paddleboard-kayak hybrid on the market. A full-coverage soft and grippy traction pad opens up the entire deck for yoga, pets, kids, and lounging, and the PowerFuse welded rails are constructed to virtually eliminate air-leakage and extend the lifespan of the board.

Price: $696 » www.islesurfandsup.com

by Bruce Bateau

Idistinctly remember the gray November day when I sat on Row Bird’s sheerstrake, looking down into the murky water of the Columbia River, where my sails were rippling below the surface.

I wasn’t in trouble yet, but this wasn’t good.

With surgical clarity I observed my water bottle tumble out of the bailing bucket, closely followed by my seat cushion, and drift downriver. Moments earlier I’d been hit by an errant gust so strong that I didn’t even have time to try adjusting my heading or feathering the main; my 18-foot sailboat was simply knocked over.

From my perch, safe and dry, I studied my situation. The bucket, at least, was tethered to the thwart and just an arm’s reach away; that is, if I could right the boat.

Fortunately, I’d practiced for this very occasion. True, my own capsize drills had taken place on a mild summer day in a placid cove along the Willamette River. A friend in a motorboat stood by, ready to assist if needed. Having sailed Laser sailboats for a few years, I knew the drill: find your way to the centerboard, climb on, and use your weight to right the boat. Jump over the gunwale as the boat comes up. Bail if needed.

Unlike a racing dinghy, Row Bird is an unballasted, open-cockpit yawl, designed to be operated more like a very small cruising boat, with the occupants typically staying dry and vertical. However, push either type of boat too hard, and it will capsize. And here in the Pacific Northwest, capsizing is more than an inconvenience. With water temperatures in the fifties for most of the year, accidentally ending up in the drink is both unpleasant

and dangerous. Nobody wants to capsize. But it happens.

So what is a sailor to do? Practice, practice, practice. My capsize drills paid off on that November day, and by the time a nearby fisherman had approached to help, Row Bird was fully upright and 90% bailed out. Aside from being unnerved and warm from all that bailing, the only assistance I needed was some help finding my errant belongings.

Still the incident only reinforced what I told my friend Mark a few years later, when he was conducting his own capsize drills in Sparrowhawk, the 19-foot wooden Ness Yawl he had recently built, and that he sails with his wife, Fern.

“You want to sail Sparrowhawk like a little keelboat,” I said. “Except for today, under no circumstances are you to let it capsize.”

It was a sunny September afternoon, and my friend Lev and I hovered in a small boat nearby as Mark and Fern prepared to purposely swamp their own vessel. With a “Here goes!” Fern stood on the rail, turning the boat rapidly onto its side and filling the cockpit with water. In their farmer John wetsuits and polyester tops, my friends were well prepared; and with their experience sailing Buccaneer dinghies, they knew what to do and launched into action like a practiced team.

In the submerged cockpit, Mark huddled near the centerboard trunk; while outside the boat, Fern swam around to use the centerboard like a lever and right Sparrowhawk. It came up as planned, but then flipped from port to starboard and back into the river. A second attempt righted the boat, but with so much water sloshing in the cockpit, the mast now swayed unsteadily.

Mark had constructed a flotation chamber in Sparrowhawk’s aft end, leaving the bow open for aesthetics and ease of setting an anchor. In place of a matching chamber, he had lashed a yellow inflatable buoyancy bag near the mast, but it wasn’t equal in volume to the aft tank. As the boat filled with water, the bow dipped markedly, and I began to worry.

“This isn’t going to be good,” I whispered to Lev, hoping that I was wrong.

Then the buoyancy bag came loose itself and popped up amidships. “Oh jeez,” I gasped, wondering whether I should leave Lev at the oars and jump in to help.

But Mark and Fern know how to collaborate. In an earlier conversation, he’d described how much they enjoy the teamwork of sailing the Buccaneer together; it’s part of how they bond on the boat. Now, although the situation looked dim, Fern was still smiling. Mark’s tone stayed calm and polite, even as he struggled to stuff the flotation bag back into a useful location. They chatted about solutions, and then Fern scooted towards the rudder to balance the boat. Things were looking up.

“Hey Bruce,” Mark called, “toss us something to stuff in the centerboard trunk slot.” I threw a towel, and with one source of water now staunched, Mark bucketed out the bulk remaining, while Fern helped with a hand pump. Although they’d been in the river far longer than desirable, they were learning rapidly, and the boat was floating higher by the minute.

This capsize drill was a wise precursor to a trip to the San Juan Islands. Curious to hear how it went, and to see what they learned from their drill, I caught up with my friends in Mark’s workshop after their cruise.

“During the drill, I did not like it one bit when the bow went under,” Fern said.

Mark shot her a sympathetic look, “But we went back the next day and did a second capsize test.”

“I still wasn’t excited about it,” Fern admitted. “But then I understood a lot more about the boat.”

“The second time, I lashed flotation closer to the middle of the boat, which helped with stability,” Mark said, “and we had fewer things float away.”

They also added a canvas bucket, which tucks securely under a thwart. It’s handy, saves space, and avoids scratching the paint or the sailors. Their experimentation and teamwork seemed to pay off. Not everyone is enthusiastic about taking a new craft to lesser known waters, but Fern said that she was, “Confident in our ability to manage Sparrowhawk.”

When I asked Mark why they chose to build another small craft, one that could tip, rather than getting a larger boat, Mark replied, “Because this boat puts me closer to the elemental experience.”

They both seemed taken by Sparrowhawk and saw the process of learning how it works as something fun and interesting—not at all a stressful chore—even if it could put them a little too close to the element. It was a calculated risk worth taking, as is so often the case when playing or adventuring in small boats.

Bruce Bateau sails and rows traditional boats with a modern twist in Portland, Oregon. His stories and adventures can be found at www.terrapintales.wordpress.com.

by Meredith Anderson

Last week I received the all-toocommon call for help: “My engine won’t start and I don’t know why?”

When I arrived, I discovered that this engine was an old 1970s Yanmar YSB 8 single-cylinder engine that is raw water cooled, meaning it is cooled with raw water throughout the engine block, without a heat exchanger mounted or coolant employed.

I knew before I dug into the actual issue that I’d be opening a can of worms. The vast majority of the time, I find myself condemning these engines as they are not worth the money to fix or are in such dire shape they will never run properly again, even if we fix the problem I was called to diagnose.

What about these engines is so bad, though? Why are folks advised to avoid them like the plague? I’m here to share the gritty parts about raw water engine ownership that will hopefully help you decide if you want to avoid them or not.

During the 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s, several manufacturers came out with the raw water cooled engine as a cheaper alternative to their most popular lines of engines they had on the market. Those of you who have repowered or shopped around for marine engines already know just how expensive these little engines can be, so a budgetfriendlier option was a welcome addition to the market. For context, most sailboat engines today range from $11,500 to $40,000 or more depending on size, and larger powerboat engines can have price tags that range from $60,000 to over $100,000.

It is most common to encounter raw water diesels on sailboats, since larger engines were generally not offered in a raw water configuration unless it was an antique engine or a commercial plant with water purification systems for the water jacket cooling systems onboard.

Raw water cooled engines were generally about half the price of the equivalent “fresh water cooled” (coolant cooled) engines. For example, Yanmar’s popular GM series included both fresh and raw water engines, with the difference clearly identified by an “F” at the end of the engine model. A Yanmar 2GM20F was a fresh water cooled engine with a heat exchanger mounted and coolant circulating through the engine block, while a Yanmar 2GM20 was the raw water equivalent of that engine. They were the same or similar engine block, just using different cooling methods and with dramatically different costs.

Raw water engines were built as the cheaper, more “disposable” option for a repower. Their operating life was never meant to be as long as their fresh water counterparts; however, they have proven themselves to be quite resilient over the years, lasting far longer than anticipated. Most raw water engines (unless you are in a body of freshwater) are circulating saltwater throughout their engine blocks. Add saltwater to a cast iron engine block, and the engine’s life is significantly changed. Certain manufacturers, such as Yanmar, built their engine blocks with porcelain embodied in the cast iron, along with adding engine zinc anodes to their engine blocks, making them extremely

Metal fatigue takes many forms, and is ever more common on raw water cooled engines as they age.

corrosion resistant for many years, while other “marinizing companies” such as Universal simply used Kubota engine blocks originally built for tractor applications that couldn’t compete with Volvo or Yanmar for corrosion resistance.

Despite how well these engines may or may not have been built, no engine will survive corrosive liquids forever. Both saltwater and freshwater (lake or river) can wreak havoc on various metallic surfaces over time. While there are still raw water cooled engines out there in service, I am finding that many of them, including the ones in a less corrosive environment such as the Columbia River, are reaching the end of their lives. I am seeing various forms of metal fatigue

Available according to the Yanmar website, the 1GM10 is one of the few raw water cooled engines still listed for purchase today.

Corrosive damage is ultimately unavoidable with raw water cooled diesels, and can show up looking like rust, barnacles, build-up, or busted parts.

(cracking/warping) and corrosive damage (rust, barnacle-like build-up) in addition to general wear and tear.

Most raw water cooled engines I work on today are in pretty tough shape. While I hate to be the bearer of bad news when I recommend a repower, I am seriously impressed that many of these engines are 50-plus years old and some are still running or have just recently given up. That’s not bad for a “half-price” engine designed to last 10 years or less!

These engines typically make it fairly obvious when they are ready to permanently retire. You’ll notice the engine becoming more and more difficult to start, or it won’t cool efficiently anymore and will begin to overheat

when it didn’t before. This is the result of buildup within cooling passages that is so solid no amount of “salt-away” or “Barnacle Buster” will help you. Metal fatigue also takes hold after a while and these engines tend to crack wide open, resulting in the engine never starting again. I have seen pistons broken in half, and cylinder heads and engine blocks with huge cracks that were not the result of overheating like one would expect, but instead just came out of nowhere.

While I can still buy rebuild kits for certain engines such as the Universal 5411, it is not worth it if the engine has been raw water cooled. I have a few training engines I use for classes that are raw water cooled. Though I also have the complete rebuild kits for them, if I were to rebuild them, they would simply overheat as their raw water passages are so badly corroded, they would never be able to cool themselves efficiently, especially with a fresh rebuild that restores the power the engine was designed to have.

A common issue with these engines is that they tend to run much colder than they should. Their equivalent coolant cooled counterparts are designed to run at approximately 180 degrees Fahrenheit, and the coolant temperature remains fairly consistent at that temperature as long as all systems are functioning properly. A raw water engine, whether it is pulling river water or ocean water, will have ranging temps circulating through it at all times, whether you are in 60 degree California waters or 45 degree waters of Puget Sound, these engines tend to run too cold at about 140-170 degrees. This lower running temperature causes a lot of soot/carbon buildup from improper combustion. Soot and carbon are extremely abrasive and harmful to any engine and will damage cylinder walls, valves, pistons, rings, injectors, and exhaust elbows. On most raw water cooled engines that I take apart, there is more abrasive wear and tear on average than that of the fresh water cooled equivalent.

So, are these engines something to avoid? If you currently have a raw water cooled engine, treating the cooling system with fresh water flushes and barnacle buster can prolong the life

enough for you to make plans for the future, but it will be important for you to keep in mind that this engine will eventually have an expiration date and you want to be prepared for that. Keep taking care of it the way you normally would, though, as you may still get several years of faithful service.

If you are shopping for boats and run across one with a raw water cooled engine installed, it is wise to have a good mechanical survey to determine what the engine’s future may entail. A good mechanic will be able to tell you if the engine is approaching the end of its life based on how it starts, whether it smokes, whether it efficiently cools, and more. If you are ok with a potential future repower and it’s your dream boat, by all means, go for it! As someone who loves to tinker, engine issues were the least of my concerns when buying a boat. On the other hand, if a repower in the near future is not something you desire, then I would advise purchasing with caution. When asked for my professional opinion, I usually encourage folks dealing with these engines to avoid dumping excess amounts of money into them, but to maintain them the best you can on a limited basis while also saving for a newer engine that is worth putting your money into.

Raw water cooled engines were an amazing option of their time. I am not sure whether you can still buy a raw water cooled engine—I did note that Yanmar still had their 1GM10 single cylinder on their website, however, whether you can still order one is unknown. At half the price, they were an affordable repower option that far exceeded their own expectations. You should approach these engines with caution as many of them are at the end of their service life. I hope that manufacturers will consider continuing to have these alternative engines as an option so consumers have more choices when repowering in their small sailboats.

Meredith Anderson is the owner of Meredith’s Marine Services, where she operates a mobile mechanic service and teaches hands-on marine diesel classes to groups and in private classes aboard clients’ own vessels.

by Dennis Bottemiller

Shifting gears embodies the idea of change. Gears most often, but it can be a metaphor for changing anything. During our busy holiday season, Tekla and I were looking for a way to get outside and on the water into nature to see birds and enjoy the scenery. Of course, winter in the Pacific Northwest is not always conducive to being outdoors but, on days when conditions are tolerable, it can be spectacular. And lonely, in the best way.

New Year’s Day was predicted to be rain free and calm with temps in the mid-40s, ideal for a winter adventure. Since Sea Lab is winterized and out of the water, my New Year’s Eve project was to find an interesting place to put in the canoe for the first paddle of the year. Tekla mainly wanted to see natural areas, so we talked about Nisqually Delta, Olalla Bay, and Dash Point, but I felt the urge to do something different, to shift gears.

In the olden days, our first “date” was canoeing on Hylebos Waterway followed by beers at the Tacoma landmark Java

Jive, and we have not done that since. It took a little convincing, but we agreed to revisit that trip and loaded up the boat to find a put-in spot. Hylebos Waterway is not your typical picturesque paddling area. It lies on the southwest edge of Commencement Bay and is a part of the Port of Tacoma area, mostly involved in heavy industrial activities like log milling, scrap metal export, and petroleum tank farms. There are a lot of things to see but it’s not what you might consider “scenic.” It is, however, incredibly interesting. We drove up and down Marine View Drive looking for possible launch sites and found that most of the access points have been blocked off to prevent “camping,” but we settled on a pullout where we could lower the boat down some rip-rap and into the high tide without too much difficulty. With that accomplished, we threw in the paddles and dry bag of supplies, zipped up our PFDs, and I gave the skateboard kick off into the glassy channel.

There truly was not a ripple on the

water except for the pure beautiful wake of the canoe and the tiny vortices following our paddle strokes. We fell into the easy rhythm of our past and effortlessly crossed the channel to the parking lot of barges. Hulks of rust, some with plants growing in soil accumulated in their aging crevices. Nature cannot be entirely suppressed.

Being a holiday, there was no activity in the port. One must be cautious around industrial areas during work hours, because giant tugs, barges, and other commercial traffic can move both quickly and imperceptibly, so paddling times must be scheduled accordingly. Today we were able to wander freely along the waterway and gawk at the cranes overhead and the industry on the shores.

Shortly after our first crossing, we paddled into a blind corner between two barges parked perpendicular to each other, and suddenly heard the insistent sound of a big diesel engine wound up and coming fast up the waterway. We couldn’t see what it was until it came around the front of the barge and we quickly realized this to be a canoeing

emergency maneuver. I had maybe 10 seconds to spin our bow into the wake of the Tacoma fireboat Defiance running at around 10-12 knots, lights flashing, going somewhere in a hurry. As I spun the bow I could see the top of the wake at least a foot above Tekla’s head, which is three feet off the water surface, and a friendly fireman waving from the inside of the cockpit. As the bow rose to meet the wake, I became rapidly aware that we were only about 20 feet from the wave reflection wall of the barge behind us and I would have little time to re-adjust to the wave that would hit us from the stern. Fortunately, our reactions were good, and the muscle memory of thousands of hours paddling saved us from rolling into the frigid January waters. That was more excitement than we had anticipated!

A few minutes prior to the fireboat zooming by, I had noted smoke rising from the metal recycling yard on the west side of the channel and, sure enough, that is where the Defiance turned in on the scene. From our vantage across the channel, it looked like a small crew on shore had controlled whatever was

There's always beauty in the reflections

burning. Shortly, the Defiance turned around and began its leisurely return tour of the waterway, again waving to us as they passed, this time with no wake at all.

As we continued down the channel, we passed sand bars and banks adorned with one of my favorite trees, the Pacific madrone, with its smooth muscular trunks of shiny orange bark—an unmistakable native Northwest tree iconic to our bluffs and shorelines, that’s often used as a perch by the belted kingfisher for a good view of lunch just below the water’s surface. We also passed all manner of human industry, reminding us of the cost to natural areas, and it’s in stark contrast to the kinds of places we usually haunt. At some point in history, this channel was undoubtedly a shallow estuary filled with bird life and an abundance of marine animals that live in intertidal areas, like this one at the entry point of

In our previous tours of this waterway, we had ended in the turning basin at the end. This time, we decided to see if we could paddle up the creek itself and see how far we could get. The creek enters the waterway in a straight dredged channel and opens into a wide-open meandering stream resolving into a beautifully restored natural area called the Place of Circling Waters.

This is the site of a former gravel mine which, at some point, closed and became what the Port euphemistically called an “inert waste storage area.”

Some 255,000 tons of contaminated soil were removed, along with 7,800 tons of broken concrete, waste building materials, and invasive plants, and was replaced by winding channels and 35,000 native trees and shrubs. The $13 million project was directed in collaboration with the Puyallup Tribe who named the

area Twulshootseed, which means Place of Circling Waters. Dedication of the project occurred in 2011 and won design awards for wetlands restoration and mitigation. The Port of Tacoma has a very informative website about public access to lands managed by the port authority— worth looking at!

Today, 14 years after the project’s completion, the place is filled with ducks of many species and many other birds we witnessed on our paddle day. I’m no duck expert, but there were a lot of ducks that I don’t commonly see. We did not have binoculars, but if we go back I will certainly bring them. It was quite spectacular and satisfied our need to be out in nature for the day.

We reached an end point of exploration on the water, and we turned to follow the flow of Hylebos Creek back to the urban jungle and the colorful sights of industry made photogenic in the rippled reflections off the water. Even though we were well dressed for the weather, four hours of winter paddling in a canoe had given us cold feet and stiff knees, and by the time we got back to the truck at the put-in we had to walk back and forth for a while to loosen up enough to get the boat out and loaded.

A mile or so before we landed, I had begun to think of warm coffee and French fries, and suggested we hit the SandBar and Grill, one of our old stopping points on our way home from Tyee Marina where Sea Lab was formerly moored. We got the boat tied on and the heater cranked up, and made the 2-minute drive to the SandBar and were welcomed with cups of hot coffee to warm our hands, beer to warm our hearts, and plenty of fries to clog those warm hearts. There are also several nicely framed old photographs of Hylebos Waterway lining the walls of the SandBar showing activity in the port from times past. I’m a sucker for old photos and some of these were real gems.

Looking at charts and Google Earth when we got home, I determined we paddled a little over 6 miles. I was happy that we had shifted gears and started 2025 on the water, one way or another!

Dennis, Tekla, and Tim Tim the sailor dog recently changed their home cruising waters from Tacoma to Case Inlet.

by Lisa Mighetto

Full disclosure: I am pretty sure I’m the clumsiest, least competent crabber in the Salish Sea. Over the years, an assortment of lines, rings, and bait boxes have slipped through my fingers and into the drink. I have fallen out of dinghies and stumbled on docks, tossing equipment into the air. Once I shoved a crab hook into my thumb. Yet I keep at it, because I have discovered that crabbing can add fun to any boat trip.

First, there is the thrill of the catch—pulling up a trap to discover that my bait actually did attract several robust and succulent crabs. The search for crabs puts me close to the elements, bringing a hyper-awareness of the vibrant world under my boat. In addition to connecting with nature, it links me to those who harvested the sea’s bounty in past centuries.

Today’s crabbers are part of an ongoing story in Puget Sound. Catching your own dinner can be a very satisfying experience, and there is nothing like the taste of fresh crab. Although crabbing takes specialized equipment and some instruction, the requirements are not insurmountable. In other words, if I can do it, just about anyone can.

My husband Frank and I got our first crab pot—a round, collapsible trap—for free at a boater’s swap meet in Seattle. A crabbing seminar at the boat show provided an instruction booklet, ruler, and wooden mallet, and we purchased a red-and-white buoy and a special line. Armed with this equipment and a license, we began our quest for crab in the South Sound. Mostly we sought Dungeness crabs, known for their sweet, delicate flavor.

Frank’s friends advised that aged cat food and raw chicken would be the

ideal bait, and when I opened the hatch and entered our boat’s cabin, the smell nearly knocked me flat. “How are we going to sleep here tonight?” I sputtered, wondering how such a vile aroma could attract anything good.

As I pondered the pros and cons of storing the bait outside, Frank climbed into the dinghy and set the pot in our anchorage. For the next several weeks we tried various locations, including Anderson Island and Pickering Passage. Our trap snagged a boot, various plant life, and a sculpin (which we released), but not a single crab. Later we learned

that although it was crab season in the South Sound, the region had been pretty much wiped out.

Then we discovered Anacortes. Our first attempt at crabbing off Guemes Island was a rousing success that we were not prepared for. Frank set two square traps that filled within hours. “Look at this!” he cried, lifting a trap heavy with crabs from the dinghy and plopping it into the cockpit, ”You find the males while I get the other pot.” With my ruler in hand, along with a diagram to identify females (who needed to be returned to the water), I opened the trap to get the first crab. The creatures, however, were not willing to be examined one at a time, and soon they all tumbled out onto the

deck, where they marched around freely, waving their claws with belligerence like a scene from the 1957 movie “Attack of the Crab Monsters.” I love this cult classic, which has entertained generations of Northwest audiences through the years at the Orpheum Theater and Sno-King Drive In. But now I was living it. Grabbing a pair of thick gloves, I managed to drop some of the wandering specimens into a bucket just as Frank pulled up with another full trap. He cooked the males in saltwater, serving them with melted butter—and dinner was never sweeter than that night in our cockpit.

Our most memorable crabbing experience took place at Spencer Spit on Lopez Island. It was a lazy midsummer afternoon, and we were three couples, all family, in two rafted sailboats. My cousin, new to the San Juan Islands, repeatedly inquired about nearby Shaw Island. He asked, “Why is it called that?” so many times that finally in desperation I told him it was named after the playwright George Bernard Shaw (it was not).

The crew found this so hilarious that we joked about it all afternoon. Clearly the wine at lunch had encouraged us to see humor in unlikely topics. When Frank dropped a crab pot over the side of our boat and pulled up one male crab, we named him “George Bernard Claw.” George ended up in a cioppino prepared by my brother-in-law Steve. Before our meal, we continued the literary theme by paraphrasing Dickens in a toast, “It was the best of times for us, it was the worst of times for him.” I felt a pang of regret for our crab, which faded quickly when I

tasted the cioppino. For all our frivolity, we were grateful for the catch, and to this day when we are together eating crab we pay homage “to George Bernard Claw and his kin.”

Dungeness crabs are an important symbol of the maritime culture of the Pacific Northwest, representing the bountiful and renewable resources of the sea. Coast Salish people have harvested these shellfish for thousands of years, incorporating them into ceremonies and communal gatherings. They have become part of the regional identity, much like the blue crabs of the Chesapeake Bay and the king crabs of Alaska.

The author's November crabbing expedition supplied many crabs for Thanksgiving dinner.

Crabbing was a serious business in Puget Sound in the late nineteenth century. When Croatian immigrants left the Adriatic Sea and settled in Anacortes, for instance, they quickly discovered the appeal and marketability of these shellfish. West Coast cities, including San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle had developed an appetite for the sweet taste and smooth texture of Dungeness crabs in particular—and Anacortes became a major supplier.

Commercial crabbers were highly sought after. The Seattle Daily Times repeatedly posted want ads for “married men” willing to harvest shellfish in

northern Puget Sound. “There is a good demand for crabs,” one reporter explained, “with few on the market” [Dec. 18, 1897]. Peter Babarovich, one of the first region’s first commercial crabbers, packed his catch in ice, shipping it from Anacortes to the Seattle market on trains. By the 1920s several crab shacks had lined the western shore of the Cap Sante basin in Anacortes. A “live box” kept the crabs fresh until they were loaded on trucks bound for Seattle. Advancements in transportation and refrigeration expedited shipments, and the canneries that emerged on the shores of Puget Sound in the early twentieth century further widened the market.

Northwest cookbooks and early menus reflected the cuisine enabled by this bounty. The Web Foot Cookbook, dating from 1885, featured several crab recipes, explaining how to “devil” the meat in a “pudding dish,” and how to remove the eggs from females. Similarly, Selected Recipes for Nelson Fancy Dungeness Crabmeat, issued from Tokeland on Willapa Bay in the 1930s, suggested crab burgers, crab shortcake de luxe, and several vague and whimsically named dishes, including crab delight, crab surprise, and my favorite, smoked crab dreams. In 1933, at the height of the Great Depression, the Olympic Hotel in Seattle listed crab cocktail, crab legs, cracked crab, and crab creole among the dishes offered in its dining room. The following year, a restaurateur in Seattle praised the “splendid” crabs of Puget Sound, noting that Crab Louis was one of her most popular menu items [Seattle Post-Intelligencer Oct. 19, 1934].

Crabbing became a significant recreational activity in Puget Sound after World War II. Today, according to the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, sport crabbers catch more than 1.5 million pounds of Dungeness crab every year “using pots, ring nets, and—in the case of wade and dive fishers—their bare hands.” State regulations typically allow harvesting in summer and, like many families, Frank and I associate crab feasts with warm weather and long sunny days. “Summer wouldn’t be the same in Puget Sound without going crabbing for Dungeness!” reported one source [“The Ultimate Puget Sound Crabbing Guide,” Riptidefish, May 29, 2018].

Even so, a few years ago Frank and I got a taste of crabbing in November—and it was a fall to remember. The season had been extended in northern Puget Sound, and when friends invited us on their Tollycraft 57 to try crabbing in the icy waters of Guemes Channel we jumped at the chance. We cruised their boat north from Olympia, anchoring at Port Townsend for the night. After docking the trawler in Anacortes, we ran the dinghy to drop our pots around Guemes Island. Frigid spray hit us as we bounced along in the chop, grateful for our foul weather gear. I had to flex my frozen fingers, encased in thick gloves, to lower the gear as I glanced at snowy Mount Baker [Koma Kulshan] towering in the distance. For several days, ours was the only boat out there, which would never have been the case during summer. This lonely pursuit proved productive, however, and each night we brought home traps filled with

Crabbing equipment viewed from the Tollycraft 57.

hefty crabs.

It was just in time for Thanksgiving. That year, our family prepared several crab dishes, mixing the shellfish into stuffing and stews. For all the sumptuous possibilities, everyone at our table preferred the crab plain—boiled or steamed with melted butter for dipping. As my cousins cracked the claws and

picked out the meat with tiny forks, we all agreed: this is a dish that requires no embellishment. And once you’ve tasted fresh crab, you’ll never want to go back to frozen or processed. “I don’t know how we’ll ever top this feast,” my cousin remarked. Frank and I looked at each other. That’s what we say every time we catch our own dinner from a boat.

Frank displays his catch on the stern of their sailboat.

Lisa Mighetto is a historian and sailor residing in Seattle. She is grateful to the Anacortes Museum for information and images. She recommends checking the 2025 Seattle Boat Show schedule for crabbing seminars. For information on crabbing equipment, techniques, and regulations, see: https://wdfw. wa.gov/fishing/shellfishing-regulations/crab

The author’s brother-in-law has cruised many places, including the Bay Area and the Chesapeake, and has concluded that “nothing beats Dungeness crab.” While we prefer our crab plain, dipped in butter, cioppino is a good way to expand the meal, as we did while rafting at Spencer Spit. In general, you can use whatever is handy on your boat.

FOR THE BROTH:

• Sautee chopped onion and celery in olive oil

• Stir in minced garlic

• Add V8 (Steve’s favorite) or Clamato, tomato juice, and/or chicken bouillon with canned tomatoes

• Add 1/2 cube of butter

• If desired, stir in diced potatoes, Italian seasoning mix, cayenne pepper, white wine, garlic powder, and/or onion powder (all optional)

• Simmer on low heat for 20 minutes or so

AND THE BEST PART:

• Remove the back from the body of the crab; wash with cold water

• Break into large pieces before adding raw meat to broth

• Add fish and/or shrimp if desired

• Cook for 20 minutes or until seafood is done

• Garnish with flat leaf parsley

• Serve with bread or pasta and Tabasco sauce

Our catch in the galley of the Tollycraft 57. Live crabs can be stored on ice to keep them fresh. Typically I use a cloth or cardboard layer to prevent them from freezing.

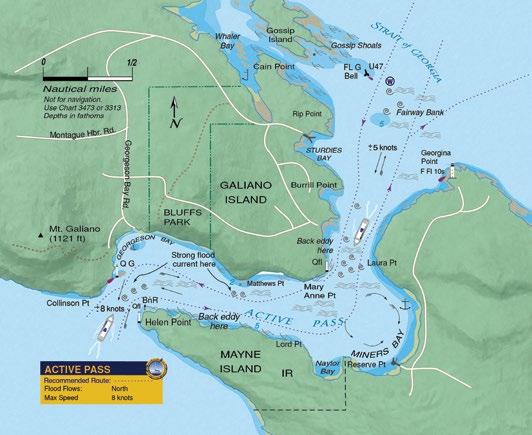

by William Kelly and Anne Vipond

Perhaps the greatest source of fear for boaters on the B.C. coast are the currents of the many passes one must navigate. The idea of your vessel being swept along by the power of a pass’s unstoppable hydrodynamic force can be a little intimidating. However, passes can lead to greater things—from secluded anchorages to significant shortcuts to your destination—and transiting a pass can be its own reward.

Passes are as changeable as the weather. This is not surprising when you consider how tidal currents are created by a complex interaction of the moon and sun, as well as the local topography and bathymetry. You soon learn that a pass transited on a calm day can be decidedly different on another day when a strong wind is blowing. For example, Porlier Pass between Galiano Island and Valdes Island turns into quite a monster if, during a large flood, a south-easterly gale comes up.

In this article, we’ll examine the major passes of the Gulf Islands—from Active Pass in the south to Dodd Narrows up north near Nanaimo—with the hope that your next transit will be a pleasant one. Be sure to have all nautical charts as well as Canadian Hydrographic Services (CHS) tide tables and Sailing Directions for this area. Tide tables and Sailing Directions are free online at: charts.gc.ca/publications/tables-eng.html.

This strip of water straddles the Canada-U.S. border and marks the eastern entrance to Haro Strait, which separates the Canadian Gulf Islands from the American San Juan Islands to the south. It is not an especially tricky pass as long as the wind is not too strong against the current. When it is, the pass can be choppy.

Boundary Pass is also part of the main shipping route, so it’s prudent to cross at right angles and make the transit as quickly as possible if traveling to or from American waters. Westbound ships rounding East Point can quickly be on a collision course with you.

Although Boundary Pass is wide—over 2.5 miles—currents can exceed 5 knots south of Saturna Island. During a strong flood, tide rips and overfalls form at the north end of Patos Island and tremendous turbulence often forms from Tumbo Island to East Point on Saturna Island. This is the main turning point for

flood currents flowing into the Strait of Georgia from Haro Strait and often creates a large eddy extending to Active Pass. When wind is against the tide, steep seas will form south and east of East Point. During an ebb, the current sets onto this reef, as the captain of the barque Rosenfeld discovered in 1886 when his vessel, in tow from Nanaimo, ran on the rock now bearing the ship’s name. As the Sailing Directions notes, ebb currents run in surges that form eddies; the flood, however, runs more evenly.

Killer whales are frequently sighted in the waters off East Point and Pacific white-sided dolphins have escorted us when crossing Boundary Pass. Boaters must observe the Interim Sanctuary Zone around East Point. On our last cruise from Sucia Island in April last year, two humpback whales followed us to the north end of Patos Island.

Further west along Haro Strait, the currents diminish to about three knots on spring tides but flood currents can be strong along the south side of Pender Island to Tilly Point.

This S-shaped channel between Galiano Island and Mayne Island is the main pass for commercial and recreational vessels heading in and out of the Gulf Islands, and its transit is complicated by the regular arrival of large, wave-generating car ferries. These BC Ferries, often traveling at speeds in excess of 10 knots, can kick up a lot of wash and must always be given the right of way. Some pleasure boaters avoid Active Pass because of the ferry traffic, but they are missing a beautiful channel abundant with wildlife, towering bluffs, and impressive hydraulics. It is also a forgiving pass in the sense that currents aren’t excessive for small boats and there are often ways to work the eddies if you have missed slack.

However, Active Pass remains a challenging stretch of water and requires a skipper to be on full alert from beginning to end. Ferry traffic is almost constant and emerges quickly around points of land concealing the bends in the pass, and the recreational boater should never obstruct or impede the course of a ferry. You can monitor their movements on VHF and AIS. Ferries normally announce their arrival at Active Pass on Channel 16 but it’s a good idea to contact Victoria Traffic on Channel 11 to receive details.

Heading west or inbound (coming from the Strait of Georgia), you can motor between Fairway Bank and the green can buoy at the south end of Gossip Shoals or enter near Georgina Point if that side of the pass is clear of ferry traffic. If we have missed slack, we’ll make our way along an eddy to Mary Anne Point. Once around this point, we are normally able to make our way

through the pass, keeping to the Galiano Island side. However, if strong current at Matthews Point is too much for our sailboat, we’ll cross over to Lord Point on Mayne Island and work our way close along the Mayne Island shore toward the kelp bed east of Helen Point, and then cross back to the Galiano side to exit the pass. If the current is too strong for your boat to complete this maneuver, you can cross over to the Mayne Island side at Mary Anne Point and wait in Naylor Bay or Miners Bay for slack.

The area from Helen Point to Collinson Point is where the current is strongest on a flood (up to 7 knots on the Mayne Island side) and where you may be tempted to turn up the engine revs to get free. If it looks dicey or the current appears to be too strong, you can turn around and drift back into Georgeson Bay to wait for the current to slacken. Be absolutely sure to stay clear of the reef marked with a green quick flashing beacon near Collinson Point and do not, on a flood, position yourself in front of it until well out of the pass.

The flood stream pushes a pronounced tongue of water into the pass and you can see currents gain speed east of Helen Point. The stream makes a beeline to the bluffs on the opposite shore where it turns 90 degrees southeast. When this stream combines with ferry wash, tremendous overfalls and rips form in the area west of Matthews Point and can reach strengths that generate a dangerous standing wave.

Ebb current is generally less turbulent, although ferry wash will continue to be a problem for small recreational boats throughout the pass. Generally, rips are not as bad during ebbs.

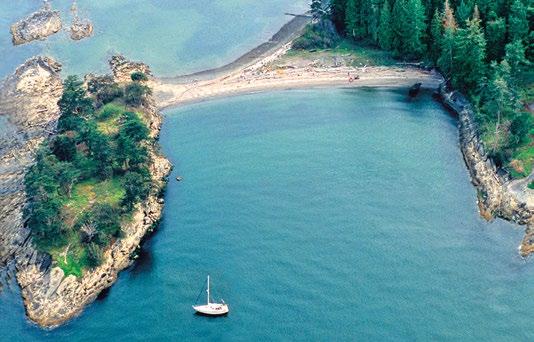

If you don’t want to transit Active Pass after a late-evening crossing of the Strait of Georgia or need a spot to wait for slack water, there is a usable anchorage in Whaler Bay just inside the reefs at Cain Point. Miners Bay is another possible overnight location, either at anchor or at the government dock (both of which will be bumpy).

The largest gate pass (meaning short and fast) south of Seymour Narrows, with currents reaching 10 knots, Porlier Pass is potentially the most dangerous of all the Gulf Islands passes. Currents here can generate large whirlpools and overfalls— from Race Point to the reef opposite Dionisio Point—and these are especially hazardous if current is flowing against strong easterly winds. On big floods, the view of the water pushing

The anchorage outside of Porlier Pass at Dionisio Bay is a good place to drop your hook.

against the rocky west shore of Race Point is impressive. In addition to currents, turbulence from numerous shoals and reefs within the pass can make the seas in the pass dangerous in strong south winds.

If you miss slack water, and the tide is not too large, you can usually work your way through Porlier Pass by staying parallel with the current and steering as close to the middle of the pass as possible. If westbound, we arrive within a quarter- to a halfmile southeast of the green flashing buoy at the north entrance. Lining up this buoy with the light at Race Point allows us a course through the deep water of the pass and out of danger of the rocks off Valdes Island. Once we are about one cable or about an eighth-of-a-mile off Race Point, we take a middle route through the pass between Virago Rock and Virago Point. There is a Q RW (quick-flashing light that is red or white, depending on your angle of approach) sector light on Virago Rock for night transits and we stay in the middle of the pass until clear of the light. Be aware there can be strong turbulence off Romulus Reef and there’s a north set towards the reef extending from Black Rock in floods. It is essential to maintain your bearings, especially at night, to ensure you are clearing these dangers. Interestingly, the maximum current for the pass at flood (10 knots), is 40 percent stronger than the ebb (7 knots). The stream, in either direction, is a fairly straight and short run, with two major deflections caused by the island topography and numerous reefs. The main danger when transiting Porlier Pass is being swept onto reefs at the east and west ends of the pass. Boaters sometimes steer a little too close to Galiano Island and find they are being set onto the reef extending from Dionisio Bay where depths at low water can be just a few feet. The area northeast of this shoal water can be very dangerous in gale conditions and is where some of the Strait of Georgia's roughest and largest seas can occur.

One of the main drawbacks of Porlier Pass is the lack of shelter on the Strait of Georgia side for vessels waiting for slack. Dionisio Bay, a marine park at the north end of Galiano Island, provides some shelter in south winds but is quite open to the north. This bay however makes for a good temporary stop in settled weather, with good holding in sand and mud, and a chance to visit the sandy shell beaches of Dionisio Marine Park. The park has a rich history, as evidenced in the shell middens that make up the beach and date back more than 3,000 years. Archaeologists have determined the Penelakut First Nation used this beach extensively.

Tugs and barges often use Porlier Pass and you can obtain information on their movements by listening to Channel 11, Victoria Traffic. Tug operators can usually be contacted directly on Channel 16.

Few passes along the entire B.C. coast are as straightforward as Gabriola Passage. This pass is a yes/no situation and either your boat has the guts to buck the current or it doesn’t, because in a slow-moving sailboat there is no chance to wiggle through if you arrive late.

In the 1950s, Canadian Hydrographic Service field workers were using baby bottles with flashlights inside to measure nighttime currents at Gabriola Passage. The bottles were cast out by fishing rods from shore and as they gained speed and, were swept through the pass, the workers would take transits on the lights and reel the bottles back to shore. By the 1970s, field workers were experimenting with fixed pods on boats to measure current. As a result of study and analysis done in 1979, daily tables were introduced for Gabriola Passage, starting with the 1987 edition of the Tide and Current Tables. (Prior to this, predictions for Gabriola were based on Active Pass.)

Gabriola Passage is a straight-line stream with the main turbulence occurring on a flood, starting at the pass and extending to Rogers Reef. Some turbulence can also be expected around the reef near Dibuxante Point. Current in this pass can attain over 8 knots on both flood and ebb. The danger at the

west end is near the light beacon off Dibuxante Point where a vessel can get swept onto this reef in either tide direction. You can wait out the tide behind Kendrick Island if bucking a flood or in Wakes Cove if fighting an ebb. The reefs at the south end of Degnen Bay can generate impressive whirlpools and should be given plenty of room.

This short pass, with no submerged hazards and a straightline stream, presents few problems except those created by other boaters. Because this pass is very narrow (often with fast streams and no room to work the eddies) it is susceptible to

for oncoming powerboat traffic.

A flood current pushing into Northumberland Channel against a strong summer northwester can result in significant chop for a few miles north of the pass. Also, there can be strong turbulence on ebbs just east of Joan Point. Maximum currents in the pass are in the 8- to 9-knot range.

Nearby lies one of the great temptations in passes—False Narrows. This is a pretty pass, in a dinghy. We haven’t mustered the courage to go through in a sailboat. With streams easily 4 knots, shoal water, kelp and numerous reefs, this is obviously not a safe pass and best left to the locals who know it well.

The information in this article and for other passes on the B.C. coast is included in Best Anchorages of the Inside Passage by Anne Vipond and William Kelly. It is now in its 2nd revised edition and is available at bookstores, chandleries, and online.

by Lauren Upham

And then there were four. Our second child, Carina, was born on June 24, 2024. She went sailing for her first time when she was just over two weeks old. We had taken her older sister, Vela, sailing for the first time when she was around the same age; she’s two-and-a-half now.

It was harder for me to get excited about going cruising now that we had two. Postpartum emotions were running high and low, and staying in our home bubble felt easier and less stressful. Packing and planning with two kids (and a dog) in tow was just that much harder to mentally wrap my head around.

My husband, Ches, was going to be super busy with work through the fall— he wouldn’t be taking his paternity leave until the spring—and we were both feeling the pressure to make the most of the summer. As I oscillated between crippling mom-guilt for choosing not to go and anxiety when we did choose to go,

we made it out only a few times together as a family before the semester started at UBC and Ches was working seven days a week, every week.

Leading up to the winter holidays, we had been talking about going out for a week or so around New Year’s. We rang in the last two New Years at Sucia Island, and this year we planned to make our way over to the Gulf Islands. As we had gotten settled into a rhythm with our expanded family, the anxiety had dissipated, and I was excited to get out on the water. We kept our eyes on the weather and, as we kept explaining to friends and family, we were looking for a safe wind window, not rain window. As I’m sure you know, avoiding rain while cruising in the Pacific Northwest in December and January is nearly impossible.

We headed down to Point Roberts, where we moor our J/40 Velella, on the Saturday before New Year’s to get settled and provision. I loaded up on groceries

at the International Marketplace and the woman at the checkout said that I won the award for biggest cart of the day. It had been a while since I had to stock up for such a long trip, and I probably overbought. But it’s better to have too much than need to break into the backup stash of canned soup for every meal. We tucked away the groceries and all the baby gear, and spent the night at the dock.

We headed out first thing in the morning to make it to Active Pass for slack. There wasn’t much wind, so we motored our way across the Strait of Georgia. With two kids with often competing needs, we found ourselves needing to divide and conquer the childcare responsibilities. Ches usually found himself up in the cockpit with Vela keeping an eye out for whales (we saw two pods of orcas on this trip!) while I was often down below feeding Carina or putting her down for a nap. Ches’s biggest challenge was Vela refusing to wear mittens and my biggest challenge was wanting to bash my head against the wall listening to the engine in the close quarters of the salon while breastfeeding. Still, we were out there—a young family of four underway for a week-long winter cruise!