ÁLVARO SIZA UNBUILT WORKS

José Manuel Pedreirinho

ÁLVARO SIZA UNBUILT WORKS

José Manuel Pedreirinho

Manuel Aires Mateus

UNBUILD SIZA

Marc Dubois

FOREWORD

José Manuel Pedreirinho

SIZA, ARCHITECT

Manuel Aires Mateus

If I were asked to associate an image to Siza’s work, I would say a bird. Astonishing, inexplicable and yet incredibly familiar. With Siza, as with Pessoa, the common and the sublime meet on a gentle game of freedom, creating images that touch us for their intelligence as disturb us for its evidence.

In each drawing, Siza finds the right way to show us the problem through clear solution. The physical and cultural reality of each situation, is an intrinsic part of his reflexion and his thought, making each response unique. On the surprising responses and apparent simplicity, Siza generously allows us imagine that we also could have created, drawn.

The path of the project, a solitary and transcendent path read from the beginning to the end is, in the surprise of the result, unequivocal. But it is from the end to the beginning that the project allows us to reread its history, its condition, its place. It reveals to us a new fragment of the world and reinvents another way of looking at it. Each project, each path, is a loose chapter of common logic that finds in its creative freedom the construction of a book, of a life work.

UNBUILD SIZA

Marc Dubois

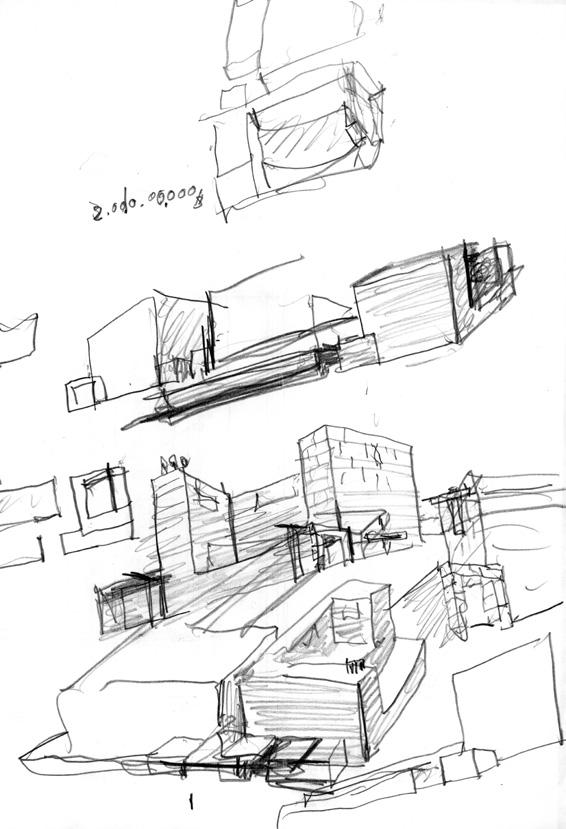

In a design process, the initial phase can be seen as an “unbuild”. A proposal that is far removed from the realised project. It is an initiative with potential that is however abandoned at a certain point in order to follow another path. Archival research into how a design evolves is therefore extremely fascinating. With preserved sketches one can gain insight into the intellectual process. A form of modern archaeology, the question of where it started with the first sketch on paper.

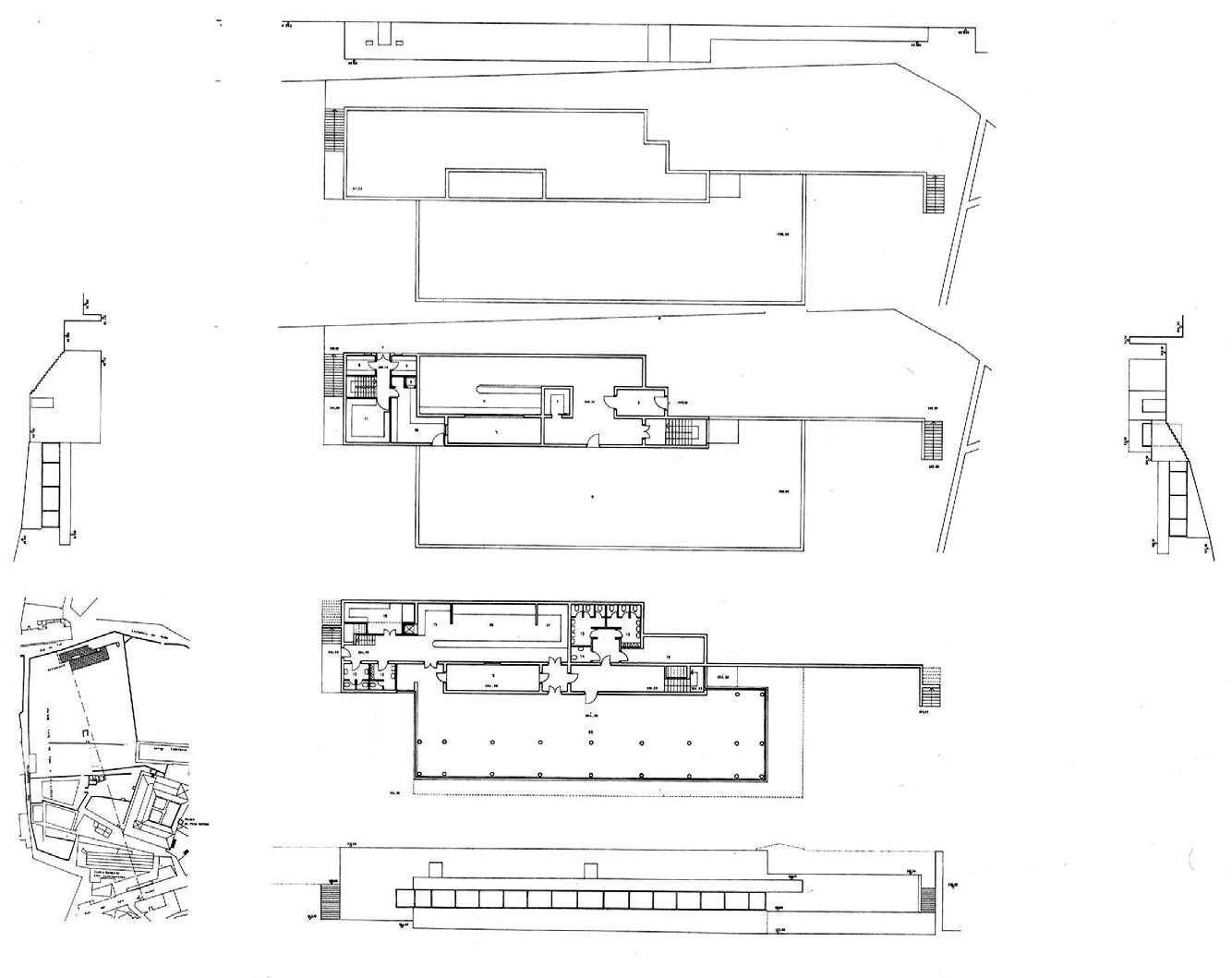

The chosen path is abandoned and this can be for various reasons, a complex decision-making process that can lead to speaking of an “unbuild” phase. The oeuvre of Álvaro Siza is fascinating because in certain projects a radical change takes place that is undoubtedly determined by a diversity of factors that are sometimes difficult to trace. The project for the new architecture school in Porto (FAUP / 1986-1993) is a key work in his oeuvre and consists of two phases. The first phase (1985-1986), also the smallest intervention, is a free standing studio building. It is the “garden pavilion”, an inwardly folded U-shape around an big and existing tree. On the adjacent site, Siza worked from 1986 to 1993 on the second phase, a whole with studios, auditoriums, library and a semi-circular exhibition space. It is an exceptional composition with an open courtyard facing the higher situated first phase with the old villa and the trees.

Many authors have emphasized the large frame of reference that Siza possesses. His ability to capture the essence of buildings and the built environment and to store it in his memory is amazing. It is not used to make collages but to transform and reuse the existing. People often look for the “sources” of his design choices and it must be concluded that a multitude of influences always come together. When you think of the swimming pool with the many skylights near Barcelona (2003-2006), you immediately think of a masterpiece by Alvar Aalto, the library in

Viipuri. It is a certainty that Siza knows Aalto’s oeuvre thoroughly. For a reference project, you do not have to travel all the way to the north; there is a reference project in Porto. The “Palácio de Cristal” is no longer the 19th century building, but a round construction from the early 1950s with a reinforced concrete dome with many skylights.

The initial phase of the FAUP project is special. Siza starts from a large square volume with a patio in the middle and a view of the Duoro. In the historical centre of Porto stands the large Episcopal Palace from the 18th century designed by Niccolùo Nazzoni (1691-1773). Prominently present but subtle in composition and choice of materials, so that no one will experience this building by Nassoni as a break in scale. When I met Siza in Lisbon in the summer of 1990, he gave me tips for my visit to Porto. What he noted at the top are the projects of Nasoni and in particular the Bishop's Palace.

The way in which Siza placed the school in Porto as a large volume on the slope has some reminiscence with the Bishop's Palace. In the cross-section one can find indications that he wanted to connect the slope with the open patio as Le Corbusier conceived for the monastery La Tourette near Lyon. At the top of the sketch Siza is looking for a variation to visually reduce the large volume. It is a U-shape with the opening facing the Douro river.

Siza probably abandoned this path because the program was too large for such a configuration. In the end he chose to bring the studios together in tower volumes on the one hand, and on the other hand a succession of auditoriums, exhibition space and library. This choice created an articulated intermediate space, oriented towards a large tree as a point of reference in the visual experience of this outdoor space, his architecture FORUM in Porto.

The first phase is visible on the sketch in the next page. The volume of the old villa and the U-shaped garden pavilion with the studios.

Next page

Portugal - Leça da Palmeira - Piscina das Marés

FOREWORD José Manuel Pedreirinho

I don’t know of any world study about unbuilt works of architecture, or about “percentage” of unprofitable works and studies, mostly forgotten.

Most probably there is none and we may eventually have to consider it as one of the conditions of the practice of architecture. The fact is that a great lot of projects rest with no sequence and lost.

We all know recognize there are often unexpected reasons that prevent or impose the change of decisions already taken. Competitions also, more and more numerous, oblige a proliferation of proposals from which only one, at the best, will be built.

History tells, however, that many unbuilt projects became, instead, references and belong to the history of architecture, such as Boulée’s or John Soane’s.

By the twentieth century examples multiply: Loos’ project of the columns for the NY Herald Tribune competition, F.L. Wright ‘s tower for Broadacre City, the plans and projects by Speer for Berlin, to which must be added the also monumental stalinist projects, the utopian Archigram ones, the Third International monument by Tatlin, or Le Corbusier’s work for the Society of Nations. Regarding this set only, there is a bit of everything, from charged and abandoned works to competition entries, even purely utopian proposals.

Lately and largely due to the important role attributed to images, a new interest dedicated to these unbuilt works has been manifest in exhibitions as well as competitions dedicated to this specific subject.

That is not the kind of architecture we will approach here.

Actually, “who makes a project in these days never knows if it is in fact to be done. A great part of what we design, is not really done, (…) more than one half of what we project is not really built, because of this or that, or the new Mayor, or no funding… for many reasons” (2001, p.22).

However, many other times, what is not built is the result of an absence of planning of the multiple variables required for the effective achievement.

There are also infinite projects successively charged for the same places, in a procession of situations derived from pure real estate speculation, or demanded by the most elementary needs dictated by propagandistic political agendas, that makes think that “architecture doesn’t really matter” (Siza 2007, p.12).

A whole series of practices that have generalized at such a low cost that it became taken as a small investment considering its potential outcomes. These are practices that reveal the missing planning in program definitions, in low consideration of the multiple implications, as well as in scheduling, economic and social consequences of changing proposals. These facts are the main sources of delays and costs that multiply in the uncontrolled sequence that prevent even the materialization of the projects.

Contradictory interests are, therefore, the causes of unfulfilled projects. Starting by the lack of planning, that reflects in practices lead by circumstantial instead of programming and priority valuing, until the subjection to political schedules or funding, all those issues to be considered.

Other times, the requirements of the commission de characterize the buildings and their memory. That happened, for instance, in the long process of the Amsterdam museum, or Matosinhos house of architecture. Also, the studies for a hotel facility inside Peniche Fortress that started in 2000 and came to an end in 2010 with Siza’s dismissal for his not agreeing with the program and exaggerated number of bedrooms imposed, (more than the double of the initial demand), which he considered inadequate to the place. This same project was now, twenty years over, restarted with a completely different purpose and, of course, without his enrolment.

Situations came out as projects that" were already contracted and are now in stand by ". Sometimes, cases are consequence of erroneous decisions, and there are many examples of them assigned to the crises of building since 2014. Álvaro Siza has no doubts that "exaggeration took place in Portugal, and in Spain, more!".

There are thousands of empty houses in our neighbour country, which is a problem well too visible from our side of the frontier, because "in Portugal too", he diagnosed, "there was an exaggeration of the investment".

Some works seem to be on the good way to achievement, yet, unexpectedly, all changes. That happened with continuous turnabouts of the long story of Stedelijk Museum that evolved a series of three fully detailed construction projects.

Sometimes unbuilt projects progress in time and become works of expectation, to which we return, like promises unfulfilled, still unhabited. It is a reality that demands understanding the means of production of our living space: political aspects, economical, social and cultural too, because it is where we can find the reasons that prevent much of these products to raise.

Of course, we will never know most of these projects, likewise we will never be able to know most of the unaccomplished ideas of many artists from the different artistic expressions.

Although the project allows us to have a quite precise and detailed idea, we shall never know its impact in the territory. Therefore, any unbuilt project stays inside the realm of intentions, somehow vague and imprecise, whose true dimension would only be acknowledged by building, furthermore, its inhabiting.

It’s always painful to watch the unbuilt, for the architect who’s earlier and significant works provided the knowledge achieved only through finished works. “When interruption occurs in the preliminary drawing it is easier than when you finish the construction project, ready to build and it doen’s happen. Heartbreak is not the right word. It has to do with persons, not with buildings. Annoyance and, eventually, irritation. Bad for us if we take it as disgust. All the works ready to building provoke a certain discomfort when not accomplished, like the first project for Avenida da Ponte, or the first for Fundação Cargaleiro in Lisbon, a house in Algés for a beautiful site that was ready to build” (Cruz, 2005, p.54).

In Siza’s carreer, all buildings characterize by an almost obsessive care for detailing, recognizable since his first houses in Matosinhos (19541957) or even more at the Casa de Chá in Leça (1958-1963). A full attention is given to the careful and adjusted choice of materials, never avoiding an experimental effort, eventually to the limits of fragility.

The difference between built and unbuilt work in architecture is the distance between design and reality. About this, Siza clearly states the need of building as the awareness that “design is a means, what matters is the building, but this one demands the making of a project" (2001, p.20), and "the building makes us go farther".He reminds us that “the project is not architecture, but it is needed to do architecture”. Something that is more and more complex, enrols more participants, some of them sort out of the architect’s “control”.

Portugal - Matosinhos – posto de abastecimento Sacor, 1966-72

Portugal - Matosinhos – restaurante Perafita, 1960

Portugal - Moledo – CODA / Casa Rui Feijó, 1965

Portugal - Vila do Conde – Banco Borges & Irmão – II, 1969

Portugal - Vila do Conde – Banco Borges & Irmão – III, 1969

NEXT PAGE

Portugal - Évora - Quinta da Malagueira

THE ARCHITECT

AS A GLOBAL AND SYNTHETIC FIGURE THE COORDINATOR

“… For another seven years, like Jacob, the architect studied the finishings, to the north and the south, where it was difficult the delivery of what was done to what was there.

In such a way that what came out was a seaside plan, delivered and paid.

But all was useless. Eventually it was understood that the architect choose only where to step and not to go, afraid of dangers and sea rocks.

So, someone said: “anyone knows where to step, and the architect is supposed to step differently than everybody else.

And so, they fired him.”

(Siza, 1980)

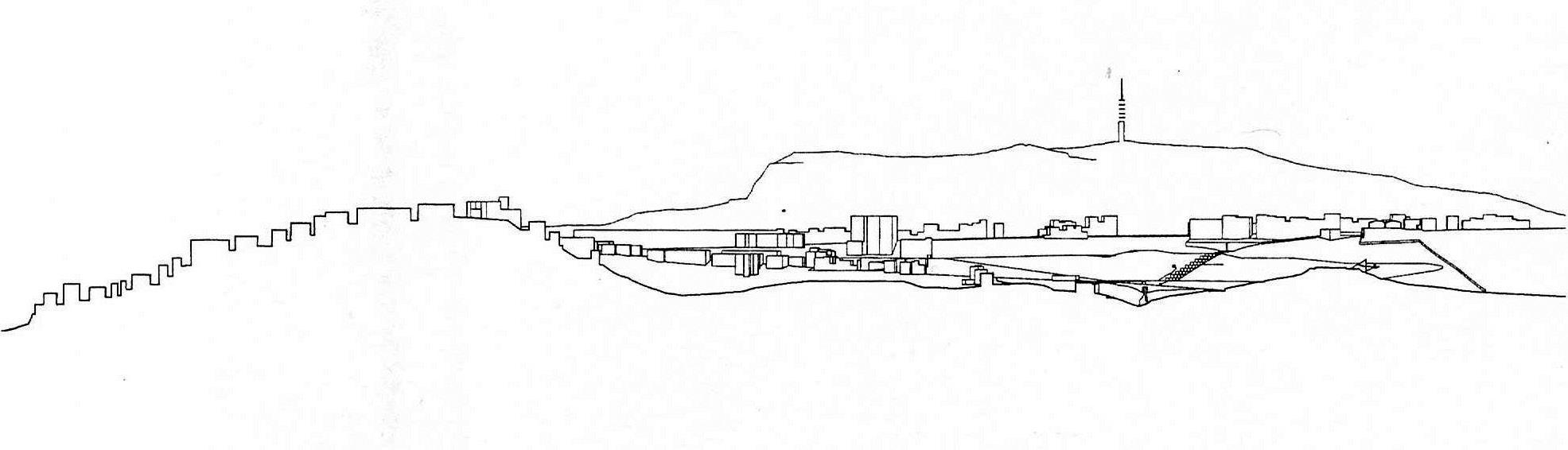

Although it was written some years later, this text approaches one of Siza’s works, in Leça, immediately after the construction of Casa de Chá and the swimming pools at Quinta da Conceição and das Marés. In 1965 he was invited to present the above study for the seaside road of Leça. That was a territory where, by then, nature and building still had an equilibrium that would soon be dismantled by the real estate pressure, and “an allotment distorted the spirit of the place” (Siza, 2009a, p.25), by eroding all references as the reflex of a tendency towards uniformity.

By the same time, he faced another challenge, a large and complex project: Avenida da Ponte (1968-1974), the connection between D. Luis I bridge and down town of Porto. “The cursed avenue that, for one hundred years, searches how to honour the entrance to the city” (Siza, 2019, p.45). It is a project that happened when relationships between planning and urban design started to attract a growing attention.

What was in question, here, was not so much nature and building confrontation, instead, there were two distinct urban environments, where an enormous rock mass presented a dramatic condition. The project for the building had a glazed façade that covered the rock but allowed its envisioning. Just like Leça project, this one would never see its development, although a second one was made, thirty years later, of witch we’ll talk further. So, it still remains.

Either cases show that territory is not and end by itself. It serves certain purposes, and the changes that occur are well revealing of the need for the role of the architect as a coordinator.

He coordinates different realities, such as these, as well as other professions that intervene directly or indirectly in architecture, for a longtime process where different phases may be assumed by other specialists. Diverse surrounding realities emerge too.

We are talking of a vision of entireness that Umberto Eco attributes to the architect by the same time, as “the only and last humanistic figure of contemporary society” (1968, p.389), since it is the architect’s role to organize all the remaining actors of the building process. That role is finally questioned by the “recently approved normative that leaves the architects in an unbearable situation. According to the new law, the architect can only do buildings, so public space is out of our competence and in the hands of landscapers or other specialists. It is forgotten that the basis for architecture quality relies on the interdisciplinary work and the sum of knowledges that is organized by architects whose work consists precisely in the coordination of specialists’ work”.

It was the awareness of the coordinator role, between very diverse realities, that conducted the above mentioned study for Leça seaside (1965-1974). Inside the urban conversion plan of Matosinhos, the search was of compatibility between the immense sea front, where nature kept its strength, with an urban fabric that still reflected the natural growth of the city, but real estate advances could already be guessed as well as its fast effects and changes of pre-existant relations. The development was based on a road to serve the beaches mainly. However, it evolved into the leading north access to the city, with parking problems to be solved and, altogether, pipeline needs between the port and the oil refinery.

Siza’s main concern was the safeguard of nature and building connection on the frontier zone of almost 2 Km stretching out to Boa Nova. A plan where the monument to the poet António Nobre was integrated but whose urbanistic design was never concluded, nor was preserved the landscape continuity.

The issue, here, is a search for balance between the object and the city or the territory, only achieved through the domain of proportions as the alternate way to contemporary obsessions for the new images, the fears and monotony. Conscience is insured through the sense of unity and consistency of place manipulation, always employing unpredictable shapes for environment connections, according to a most humanist vision where nature and work are always seen as parts of the whole.

This approach will be underlined, years latter, by the committee for Wolf Prize in Arts, in 2001. Unanimously it referred to the outstanding critical answer of Siza for the continuous featuring either of landscape or urban fabric, starting from modest interventions whose architectonic power had catalytic effect for their surroundings’ qualification.

In those “first works the germ of an obstinate sensation, impossible to repress, of an architecture that has no end, that goes from the object to space, therefore to relations between spaces, and finally meets nature” (Siza, 2000, p.31).

The same awareness is notorious is such diverse projects as the cava di Cusa (1980), the urban park ok Salemi (1986), both in Sicily, or in the Granell museum of Santiago de Compostela (1994), all unbuilt. Also, in the ways how existent water lines organize and systematise the new Alhambra door, the San Domingo gardens in Santiago de Compostela, as well as in the urban park of Lecce at the south of Italy. References may be diverse: a tree (in Santiago, Setúbal and FAUP); a water line (in Santiago and Alhambra); a rock (Lecce, but much earlier also in Boa Nova); and so on. A kind of “micro geography” as Beaudouin refers to it, where Siza “explores the geographic dimensions of the relations between project and nature” (2007, p. 61).

PAG 056 057

The hotel presented in 1997 for Gata Cape in Almeria, Spain, by its insertion in the landscape, recalls the layout for another hotel designed thirty years back for Vale de Canas (1867-70) in Coimbra surroundings. Located on a site next to the salt pans, a natural Park and protected zone assigned for touristic use, the project integrated topography and respected the limits imposed by the Natural Resources Plan and a most strict legislation. Even so, under polemics raised by the extreme interpretation of legislation, the project was refused, stopped and abandoned into the bureaucratic inertia.

In all these projects, the confrontation between natural and built elements acquires an extraordinary dramatism that belongs to the concept, insuring continuity among several forms of expression and multiple scales

The monument was partially built, so years later, but never finished and some essential relations of the sculptural group with the site can not be understood.

PAG 098 099

Important to the relevance of all these proposals is that they were never treated as isolated elements, but as a part of a whole as space organizers. Either in the way how they relate and isert in the surroundings, or by profiting of their natural features, or even, the urban contexts where they inscribe themselves.

They always want to create places, by the relationship established with the sites, where they express aesthetic and symbolic concerns. In the Calafates place, there would be a play between several sculptural elements and the walk; in the António Nobre one, they would result from a clearing formed by two tree massifs never planted; in the victims of Gestapo monument, a kind of crater was proposed for the urban void that remains in the place where first standed the baroque palace of prince Albrecht in Berlin (Pessanha, 2003) and later hosted the nazi police headquarters.

PAG 100 101

Years later, Siza would be invited to make a monument to local power in Coimbra, that would stand near the Mondego river, next to the Portugal pavilion, that wouldn’t leave the paper. Such studies went on to 2005, and explore, again, the use of banal objects to build a monument, this time were several stone blocks with engravings of all the Portuguese municipalities’ names.

The highlight given to the coordinator role of the architect, in times of progressive specialization, stands up as a raising need of connections between very diverse knowledge areas, that go from humanities to the most technological sciences. The second post world war posed the debate of knowledge areas in the center of architect’s concerns, while facing the growing complexity and urgency of responses.

Some tried to answer that knowledge diversity by a multiple instalments of specialized ignorants (Santos, 1987, p.46), others searched, through the coordination of them, ways of keeping the necessary consistence of the discipline. For Siza, the specifics of this activity involve such a large variety of areas that make it incompatible with a primary idea of specialization, as if it was admissible to think of “an architect competent for little houses, (…) for museums, or for sky-scrappers”.

In a way, the mode how knowledge has been excessively fragmented makes it incompatible with the need for successive analysis, because human mind does not work in a linear way, but in a syncretic one instead, in curves or zigzags. Siza takes this non-linearity of thinking and its openness to eventualities, as what allows the production of non-existent information. They are memories, where times and dimensions of the present can be of variable duration, for ones or the others, and that means a great variety of interpretations. The will to search for difference in experimentation and learning, through the variety of works, leads him to accept small commissions, even when overloaded by large ones, because those are the ones that allow him tests that, in some way, are restricted at the others. He is quite clear by saying “I am against the idea of specializing. I like to diversify my workz” (Siza, 2012a, p.117). So, the references to Alvar Aalto, go further beyond the non specialization, in the search of a global performance of the architect’s figure and its presence in the history and culture of each country.

Leça waterfront plan, Matosinhos, Portugal, 1965-74

Leça waterfront plan, Matosinhos, Portugal, 1965-74

Restaurant in Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 1989

Urban Park in Salemi, Italy, 1986

Ishmaelite Centre, Lisboa, Portugal, 1995

Casino and Restaurant Winkler extension, Salzburg, Austria, 1986

Italy - Roma – church of Santa Maria del Rosario, 1998

Italy - Roma – church of Santa Maria del Rosario, 1998

Portugal – Porto – monumento aos Calafates, 1959

CONTINUITIES AND DENSITIES OF HISTORY IN THE RELASHIONSHIP OF TIME AND SPACE THE UNITY OF ARCHITECTURE

“Designing an exhibition space for the Pietà Rondanini is a small, but highly inspiring task. An international tender was launched to create an environment for this marvellous sculpture by Michelangelo, which has an extraordinary history in its own right. Each of the architects invited for the tender studied the museum and its interior itineraries.” (...)

“The unfinished reverse side of the Pietà constitutes, however, an extraordinary document, related to its history. The work was carved from a block of marble offered to Michelangelo. He started to sculp the block, attempting to achieve a treatment similar to that of the Pietà in the Vatican, with very perfect polished marble, allowing the observer to almost feel the skin. He died before completing the work, aged well over eighty. However it is not known why the artist broke his original work and commenced an entirely different sculpture.” (...)

“The proposal was to sub-divide the current room, organizing a square-shaped space intended solely for the Pietà Rondanini, not exactly in the sentre but a distance from the room’s walls, thus making it possible to walk around the sculpture. It was also planned to place Michelangelo’s bronze death mask on the wall together with a stone head that was discovered which is thought to be that of Christ in the initial sculpture. It is a highly moving display, partly due to the fact that the Pietà hab been missing for many years. I was chosen for the implementations project and also to build an extension for the other part of the museum, at the invitation of the Director of the Milan Museums. However a polemical whirlwind was set off ... Finito. But I’ll never forget the experience of spending an entire day with the Pietà Rondanini.“ (Siza, 2005)

(1999 – Competition study Pietà Room – Sforzesque Castle – Milan) The above description of the project for the pietà setting is a good example

of how to work and make architecture with a minimum of elements. In this case, it is the structure of a walk by one or two pieces that must be in a pre-delimited space.

PAG 124 125 126 127

The mode of display “includes the scenography and the staging, the physical, objective, real conditions (...) and also the virtual, dreamt or so often desired conditions that condition the function of ‘seeing’. The mode of display should enable us to know the position and time that permitted ‘that’ perspective. It should be possible to understand the conditions and structure of relations between the observer and the observed. The mode embodies the duration and time. In the mode, the subject and object interact in its ontological irreducibility” (Salgado, p.26).

As Baumann would say, the more liquid the world becomes, the less space and time are the undetermined references of identity, where different times coexist. References to time and space lead us to the fields of history and geography, where architecture expresses the changes and conflicts that are social, politic and economical. It makes us understand the continuity of history times.

This understanding and consistency are also expressed when Siza explains what it means, for himself, “beginning” while thinking of work materialization[33]. Such reasons may have led him to opt for construction courses in teaching, aware that there would be where to fing the connections between architecture, project and history. The same issues stand for Gregotti as the material of architecture. They reflect a comprehension of times and spaces, as well as relations in ‘density’ of a wider structure that translates temporal space, social and economic, therefore cultural and historic.

The kind of history whose study “has indirect routes to influence action” (Tafuri, 2011), taken as a product of experience and not as a memory warehouse, seen as a continuum between past, present and future, as van Eyck liked to say. For Siza “things are in flux. Even when a project can be connected to some historical model, the link is never a direct one. There is this sort of metamorphosis” (Curtis, 2007a).

When Siza began his work, in the 50’s, it was largely overpassed by the first generation of the modern architects, the need for a break with [33] Cfr text dated 2007, “Arquitectura: Começar-acabar” in Textos 01, p. 365; Architecture d’Aujoud’hui, nº 211, p. 1

past and history. Such rupture with the past meant, “what all avant-garde groups wanted to liquidate was not exactly the past but the pastism instead, the attitude that is based on a devaluation of the present in favour of a supposed immutability of the past” (Hatherly, 1979, p.61).

It was about ‘tempering’ the reading of the facts with the new features, taking them away from any paternalistic or moralistic thoughts. So, it is abandoned the idea of understanding them as a known and planed becoming, that released human beings from de duties of choice and personal responsibility, once things would be made without us; ‘living up to’ was enough. This situation was, by 1928, acknowledged by Fernando Pessoa as a “portuguese provincialism”, and Bauman calls it an “intellectual provincialism”, or folk-pop (Bauman, 2002). It was mainly a rational, cognitive and temporal decision. Social issues are understood as the results from a wide analysis of history, recovering the idea of historic continuity, not as the expression of conservatism but of rupture both in planning and project.

Much of the second post war debate locates in the epistemology aspects and the continuity of time and history. That was the outcome of reality awareness before the need of answers for the massive destruction caused by the war. It was also the fruit from human sciences development, such as history, where anthropology and sociology play an essential role for the attention payed to man, to his individuality and his social relationships.

After the first experiments on façade restoration in some cities, it was quickly observed that “urbanity is much more than the form of the city, it is a way of life, a civic culture that may, eventually, develop in another setting and that, most likely, will only be achieved in another setting” (Innerarity, 2010, p.138).

The second post war relocated the concept of place in the center of attentions as well as in architecture, because, as an “activity of practices” she must “observe” and “overpass” the “functional data, the daily elements, the rooted habits and legitimate expectations, the learned shapes, the ones that may be transformed and others that seem definitive, (…) all this is called the idea of architecture” (Grassi, 1979, p.191).

This was the cultural background of all artistic manifestations debate, all over the world. It was also where the problem of regionalism was placed, and ‘a necessary initiative’ was defended, materialized in Portugal, by the Inquérito à Arquitectura Popular[34] This survey was a source of many misunderstandings: [34] Inquérito à Arquitectura Popular- Popular Architecture Survey, so far referred as ‘survey’. The field work for this survey was developed between 1955 and 1957, the publication was in 1961.

Desperate because the projects were made and developed under a complete consonance of client and architect, which was not enough to overcome political pressures. These led to the removal of the previous director of the museum and the responsible for the project, to a posterior project and its very fast construction, which shows what was the great doubt of the time: was it still a museum with a restaurant, or a restaurant and a shop with a museum ahead[62].

PAG 160 161 162 163

For Álvaro Siza, the relation between form and function, as between local and universal, are so complex that can not be analysed through a linear vision or inevitable connections. That is why in most projects, the great merit lies in seeming that the architect was never there, did nothing. It happened in such works like Rotunda da Boavista in Porto, and the gardens of San Domingo in Santiago de Compostela.

Often, recovering is enough, to highlight what is there, which is a hard to understand aspect before construction. Other times, it is necessary to alter what’s more and does’t make sense anymore, so that new uses may be possible, and territories reviewed.

To complete our analysis of time we can not forget the changes made after what is considered the conclusion of an architecture work. It happened in the hotel of Vidago, through the inclusion of, so called, ‘decorative’ elements, which, most of times, entirely subvert the project and disturb its reading. It also happens when the unity of the work is broken by a succession of phases that overlap with no conceptual connection, and their delivery to distinct ‘specialist’ professionals: exterior – interior; architecture – furniture; etc.

This is, for sure, one of the advantages of the unbuilt, because it keeps the clarity of the proposal’s ideas, without changes that often come from successive interventions of the materialization process. It has to do with an understanding of architecture assumed at all scales and dimensions of the project, where detail needs consistency, not only formally but also conceptually, with all the other dimensions of the building.

Consistency is what grants unity to a process of work that is embracing of the many and diverse intervening that make architecture. For the same reason, when it is broken, unity remains significantly affected.

*

[62] A new competition, in 2004, choosed the project that was built, added a small museological and office area, but occupies a terrain area that almost duplicates the old museum one. Marc Dubois refers the result as “very disapointing from a museographic point of view” and quotes that “the new building was nicknamed ‘the bathub”.

Italy – Milano – Rondanini Museum, Pietà, 1999

Italy – Milano – Rondanini Museum, Pietà, 1999

Italy – Siena – Matteoti Piazza, 1988

Spain - Valencia – Alcoy – Reconstruction of portal de Riquer, 1987

Portugal – Lisboa – Remodelação cinema Condes, 1991-1992

–

– Library of the University, 2001-2002

Spain

Salamanca

v Portugal – Sines – Centro cultural em Santo André, 1982-1985

Italy – Caorle – Municipal building, 1995

COMPLEXITY NEW PROGRAMS AND PROBLEMS

About Bahia House (1983-1993)

“I presented the project for Bahia house in diferente places. There was always laughter.

Not for displeasure, I kink; the way how I presented it may have been interpreted as ironic, or demagogic.

But it was not so.

The project was defined after analysis of what, very directly, conditioned it.

Finished, I couldn’t imagine it differently; although I recognize that it might take a thousand shapes, less weird, eventually less controlled.

1. What makes it apparently capricious, scarcelly depends from the drawing moment or moods of the time; what makes it understandable has to do with centuries of elaboration, from which each of us knows –still – but a tiny part.

2. The unbridable search for originality impresses me; anxiety does’t bring but banality, a monotonous accumulate of “variations”.

What amazes me is the frequent complex of “lack of imagination”, or, the opposite to affirmation. As if imagination was something outside reason – overpassing it – something to introduce in the act of project as an autonomous process; or as if it might be one more instrument, to use in this or that moment, according to methods or intutions; or, as if it might be a rare aptitude.

What floats pre-consciently is not a disease or (something else). Frontier between conscient and unconscient depends on the ways of the reason, on its energy and requirement.

To live in liberty – to learn to live – goes through breaking that frontier line.

3. A brief explanation of the project:

a) A house was to be built on the right border of the river Douro, next to the city of Porto, between the marginal road and the water, in a narrow and large slope terrain controlled by supporting walls of loose stones: the terraces of wine cultivation that build the Douro landscape from east to west.

b) The road profile of the national road does’t allow parking outside the terrain and the Building Regulation for the place obliges a 15-metre clearance from the road. The terrain slope (from level 28,88 m to 9,20 m) makes impossible the hypothesys of an access ramp to the only terrace that has enough size for the deployment of the house (9,20).

The solution for the parking of a car is the construction of a garage at the road level, through a pontoon, if we want to keep the landscape continuity not accepting an enormous landfill.

c) The acess to the house terrace may only offer the necessary comfort if it includes an elevator, to be complemented by ladder – a diagonal that allows continuity between the volumes of the house and the garage, together with structural an image consistency.

d) Ladder and elevator lead to an atrium and, from it, to the several previewed spaces, distributed around a yard. The whole floor is raised from the terrace level and stands on an existing wall and two pillar supports. You get, so, the convenient interiority when landscape is of an asphixiant beauty.

e) So, there is no caprice in the form that results from such pressing conditioning; and the comments I heard of “imagination at last” were not opportune.

d) What reason produces may become mostruous. Architecture - cosa mentale – survives through a control that overpasses subjectivism: through the codes that become universal, by agreement on the “good proportions” that have been tested through experience, where a me-who-design is not enough. A system of control, a safe code – universal – for space and form organization has been always the “responsible” purpose of architecture: “ The Orders”.

But how many achept, today, the Orders, even when they are desperately or happily unburied? Orders are the bridge between Man and Nature; they establish the necessary relationship. Through them Man places himself, not to become a body strange to the Nature where he emerges.

When a code goes into crisis, when only a few accept its references, or they are not enough anymore, it remains but to find the direct sources: landscape, cloud passing by, clearance, body, dance, immobility, stability. Particularities that make the Universe, things that turn around one man and of the gestures of men when they meet.

g) The design of this house stands naturally on what, of very old, lyes “sous la lumiere”. Sudenly it got a neck and a head and wings; its paws descended to the last terrage and plunged. A shiver must have gone through its riscs.” (Siza, 2005)

Mário Bahia house in Gondomar, is the explanation of haw a form, apparently complex an almost weird in design, can be a natural consequence of a simple solution.

This description of one the unbuilt works of Álvaro Siza reflects what his project process is, by finding amidst site contradictions and program needs, the complex reasons for project development.

PAG 182 183

Complexity is here highlighted in the program of one family house and a small terrain. The kind of situation that may belong to what Bauman, referring to relations between complexity and liquid modernity, calls “contexts that depend on their initial conditions” (2007, p.65).

This is one of the paramounts, if not the greatest, transformation we assisted through the second half of the XX century, rapidly accelerating but more aware after the 70’s, that is globalization.

Its origins have different and diverse causes, acting on a space that is strongly compressed and extraterritorial, where economic structures hold a determinant role, by altering ways of life, social structures, political and cultural which, as Virilio says, does not deport people any more but their spaces of subsistence and life.

Maybe, before, we thought that “more or less everything could be solved by the simple operation of externalizing the problem, by its transference to an out of sight “outscape”, to a far away place or another time, the ‘future’ (Inerarity, 2009, p.124), and, now, we became aware of a need to face our own time and space.

Portugal – Gondomar - casa Mário Bahía, 1983-1993

Portugal – Gondomar - casa Mário Bahía, 1983-1993

Portugal - Lisboa – Plano Praça de Espanha, av. José Malhoa, 1989-1992

Portugal - Lisboa – Plano Praça de Espanha, av. José Malhoa, 1989-1992

Portugal - Lisboa – Fundação Cargaleiro I, 1991-1995

Portugal - Lisboa – Fundação Cargaleiro I, 1991-1995

Portugal – Porto – Plano da Boavista, 1990-1998

Portugal – Lisboa – Plano para Alcântara, 2003

Next pagez

Portugal – Setúbal – Setúbal Scholl

THE UNBUILT – THE POETICS

“…The hardest thing in a project is to begin it. It is like catching the end of tissue mesh and start to undo it little by little. For me, one of the main ends is the function. To do it we need a fantastic functional program. The project development is its to break free from the respect for functions.

Breaking free in the sense of not respecting, is proposing something that may follow very diverse paths.”

(Siza, 2008)

One of the first monographic studies of Siza’s work, published in 1986, with writings from K. Frampton, B. Huet, O. Bohigas and V. Gregotti, has justly the title: “poetic profession”. It is a title that expresses also the understanding of poetics by Muntañola, that can and must be used as an instrument for the critical analysis of any work of art.

Some times even behind the possibility of an analytical description, but absolutely necessary for our understanding of his work.

Long before, however, Heidegger stated that “all art is essentially poetry”, a thought that relates people’s experience and spaces “in harmony with the environment, the earth, the sky and the divine”.

Gregotti, in 1972, called it “ a kind of autonomous archaeology made from strata from previous trials and error corrections that in anyway introduce in the final proposal, which is built by accumulation and purification of successive discoveries that become the data of the posterior ones”, that is an “archaeological foundation, only known to himself”.

And Siza knows very well that “the idea is in the site (…) what starts as very simple and linear, will become complex and akin to reality – genuinely simple” (Mendes), but also refers to “rediscovering the magic strangeness, the special nature of obvious things” (1986, p.9), something that is besides the obvious, a vision besides the program, the place or the cost, and Alves Costa refers the task of architecture “to find out what already exists” (2015, p.121).

This kind of poetics exists in any scale works, since architectonic space must go farther the three physical dimensions, to include time and go beyond its boundaries. Poetic quality must be articulated with the immense technological availabilities and the growing complexity of cultural demands (Muntañola, 2000, p.23).

If focusing the architect’s performance and his production helps us restrain any thoughts about the theoretical limits and the disciplinary practice of architecture, the analysis of its complexity allows to establish an approach to his exercise, yet neither of these aspects or the whole make any sense without the poetical dimension. It is such that, by inherence to any artistic manifestation, tends in architectural specificity and its functionalism, to be often forgotten.

To search for the poetic expression presupposes understand the way how projects are approached and developed, according to Siza “architectonic creation is born from an emotion provocqued by a moment and a place” (2009a, p.79).

From Távora, his master, Francesco Dal Co says, “the most important that Siza learned from Távora was a working method. Having appreciated Távora’s professional attitudes and the refinement of his culture, Siza renewed his commitment on the level of design, as revealed in his more than promising early works”. (p. 23)

Differently from Távora, who reflected over the blank page, as the place and material of all creation anguish, Siza sees uncertainties always related to a building approach that starts at the need to analyse the place and make a drawing before beginning to calculate the square meters of the construction (Costa, 1990, p.13). So, they are placed in the multiplicity of paths open by the permanent demand, without certainties, expressed by his words, “I don’t dare put my hands on the helm, watching only the polar star.

And I don’t point a clear path. Paths are not clear”. (Siza,1983; 2009a, p.28)

A clarification is found in Tafuri when referring to the “fundamental difference between beginning and origin? And why a beginning? Wouldn’t it be more productive to multiply beginnings, where everything comes

together so that I may recognize the transparency of an unitarian cicle that grows from intertwined phenomena that want to be recognized as such?” (1980, p.6)

In such beginnings may be found “the expression of any singularity that, not betraing the essence, may free design from too obvious reasons. It achieves, so, a touch of authenticity that attracts in a not aggressive way, but, at the same time and partly, emerges as banal. To start with an originality obsession is an uneducated and primary process. “(Siza, 2009a, p.241).

Actually, “to the moment before we start (…) we have the world to our disposition – what, for each of us, constitutes the world, a um of informations, experiences, values” (Calvino, 1990, p.149).

It is after this multiplicity of beginnings that work develops because “when I am called to project a building for a place that I don’t know, or have a vague idea, sometimes the first drawings help to trigger a series of thoughts that materialize later” (Siza, 2009a,p. 47).

The same difficulty places itself to decide the moment when a work must be finished, even because, for Siza, a job never ends. It doesn’t matter him, so, the imposition of perfection or style before the construction of a support for urban life and its changes.

Just like Borges who said “we publish not to spend life correcting drafts”, so he feels the need to get free from projects, even when refers to ‘end’ as “an imprecise word, a kind of translation error, to replace by the word start” (Siza, 2009a, p.366).

However, if the unbuilt is not (yet) architecture, it becomes it by the authenticity of a process that does not suffer alterations, and is for sure, where best and more freely is registered and expressed the project poetics.

Even so, because you don’t project for not building. That would be an absurd, and the denial of the very idea of a project. The unbuilt is always the consequence of a series of circumstances posterior to the project development, it never is an a priori decision.

Obviously, exception made for some of the very rare examples of an architecture that may called utopian, projects that are unbuilt are exactly made the way the others are, and must be always understood as experiences that integrate in the continuity of a life’s work.

Among most unbuilt works that fill architects portfolios, many were contest submissions. They are the kind of projects that, for their own specificity, often explore the most spectacular and formal features of the proposals.

recently materialized in a natural park of South Corea[79]. It was adapted to a terrain of quite different topographic characteristics from the ones of Madrid, but with an excellent sight of the forest, although, naturally, without the two Picassos[80].

This is not the same building as the one he designed to Madrid, because this is not the same site, but undoubtedly an exceptional work of art, situation deserving our reflection (attention). Probably another confirmation oh his words that “many of my works were never really finished from my point of view. They live with me as part of my ongoing search” (Curtis, 2007b).

“What have I learned of architecture; they ask me. I try to answer following a recent interview of the writer José Saramago. About his ‘gift of writing’, he declared that the real gift is, in reality, the reading one, because who doesn’t read can’t learn to write.

I believe something alike may be said about architecture and, while reviewing my work, I think of how many “readings” I made since I was little and was mostly interested by painting and sculpture. My first meeting of architecture goes back to 1947: my father took me for vacations to Barcelona and we visited Gaudi’s works. I would draw “La Pedrera” and enjoyed because I saw it as a sculpture. Then I noticed that everything I could watch at home - banal things like doors, windows, doorknobs, handles, baseboards, etc. – the whole set, in Gaudi’s houses, sang. (…) Remembering those circumstances, I’m interested in transmitting to the students that, then as now, there can not be one unique reference, but a multiplicity of friends. When an architect is working, all the readings, everything he saw, are present, but what he produces is only his. Even because architecture is not the systematic use references, instead it is something much more complex, a convergence of different interests, emotions and, casualties.” (Siza, 2009b).

[79] In Saya Park Art, in the district of North Gyeongsang, followed with Carlos Castanheira. The building was constructed in a large park inside a pine forest where took place two other buildings also designed by Siza: an observatory tower and a chapel.

[80] Siza designed a rusty corten steel piece to be hanging from the roof, and 2 other pieces were shiped from Portugal to be on display there.

Greece – Thessaloniki – Docking pier, 1996

Portugal – Braga – Hotel e restaurante no Monte Picoto, 1981

Spain - Madrid – Visiones para Madrid, 1992

South Corea - Gyeongsang – Saya Park Art Pavilion, 2021

SPECIAL THANKS TO

Álvaro Siza Vieira

Marc Dubois

Manuel Aires Mateus

Teresa Fonseca

PUBLISHER

AMAG publisher

COLLECTION

Pocket Books

SERIES

Notes on architecture

VOLUME

PB 07

TITLE

Álvaro Siza

Unbuilt Works

ORIGINAL TEXTS

by the respective authors

TRANSLATIONS

Teresa Fonseca

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Ana Leal

EDITORIAL TEAM

Filipa Ferreira

Inês Rompante

João Soares

Ricardo Figueiredo

PUBLICATION DATE

November 2024

ISBN 978-989-35767-6-2

LEGAL DEPOSIT 475406/20

PRINTING

Graficamares

RUN NUMBER 1000 numbered copies

OWNER

AMAG publisher

VAT NUMBER 513 818 367

CONTACT hello@amagpublisher.com

FOLLOW US AT www.amagpublisher.com

ÁLVARO SIZA

UNBUILT

WORKS

José Manuel Pedreirinho, graduated by ESBAL (1976) and Doctorate by the School of Architecture of the University of Seville, in 2012. Working in a liberal profession in his own office since 1980 and as a teacher since 1985, at the Porto Art School, Oporto Lusíada University, and at the University School of Arts in Coimbra, where he was Director of the Department of Architecture and the school headmaster until 2014.

Associated since 1979 in several newspapers and magazines, and author of several books on themes of History of Portuguese Architecture of

Álvaro Joaquim Melo Siza Vieira was born in Matosinhos in 1933.

He studied Architecture at the former School of Fine Arts of the University of Porto, between 1949 and 1955. Being his first work built in 1954.

He was a teacher at the Oporto School of Architecture of the University of Porto, city where he works.

He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; he is an “Honorary Fellow” of RIBA/ Royal Institute of British Architects; he is a member

the 20th century, namely “History of the Valmor Prize” (1987), “Dictionary of Portuguese Architects and active in Portugal” (1998 2nd edition , updated in 2017). Co-author of the “Lisbon Historical Dictionary” (1994) and “Siza not built” (2011).

Jury in several architecture competitions. From January 2017 to 2020 he was the President of the Portuguese Architects Association and the Fundación Docomomo Iberian, and member of the Executive Committee of Europe’s Council of Architecture (2018-2020). Vice president of CIALP.

of BDA/Bund Deutscher Architekten; “Honorary Fellow” and “Honorary FAIA” of AIA/American Institute of Architects; he is a member of Académie d’Architecture de France; of Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts; of IAA/International Academy of Architecture; National Geographic Portugal; Honorary Partner and Honorary Member of the Portuguese Architects Association; member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters; Honorary Professor at China Southeast University and the China Academy of Art and Honorary Member of the Academy of the Portuguese Language Architecture and Urbanism Schools.