The Census. Britain and British-India, a partial quantitative archival piece

Essay: A short text. A reflection piece. A pre-cursor and after-effect of creating ‘The Archive of Tables’.

SHARVAREE PRASHANT SHIRODEThe collection of population data, commonly known as the Census, has been taking place periodically every 10 years in the United Kingdom, specifically in England, since 1801 The only exception was made in 1941 when the Second World War took precedence over population enumeration The Office for National Statistics (ONS), which is responsible for conducting the Census in England and Wales, states:

"The census is a survey that takes place every 10 years It gives us the most accurate estimate of all the people and households It asks questions about you, your household and your home, and it builds a detailed snapshot of society Information from the census helps the government and local authorities to plan and fund local services, such as education, doctors' surgeries and roads " (ONS, 2022)

It is the complete enumeration method for every unit of the population, and one of the only methods statisticians use for primary data collection, informing thousands of other surveys around the country and the rest of the world The modern definition, as stated by the United Nations (UN), outlines the four main features of a census:

1 It must count individuals separately

2 It must cover everyone within a defined area

3 It must present a "snapshot" of a population (i e , it is taken on a specific date to prevent double-counting).

4 It should be part of a series, at defined intervals (e g , every 10 years to be able to identify trends over time)

(UNSD, 3, 2017).

In this essay, I explore why definitions and parameters such as these for a census can facilitate coercive methods of data collection, past and present-day, as well as quantitative and qualitative The essay will also probe the question of an inherent need to categorise populations in foreign (coloniser and colonised) contexts Throughout the narrative, the focus will be on the British-Indian census; what it means to separate qualitative and quantitative data, and what it means to quantify a community, a country, a whole sub-continent.

The purpose of this essay is to discuss the distancing of numbers from text, pre-empting the archival exercise of doing so. This is an exploration, not for "What are the numbers behind British imperial Raj in India, and what are the categories?" but rather, "Why are there numbers? Why are there categories?" It is these numbers that sanction a systemic change

within a population, as they are the "science" that "back up" and "justify" the need to promote sovereignty.

Out of the scope of this essay is pinpointing individual data points, as the archive is a tool for investigation, for the individual This essay is merely to provide a context for the need to create such an archive. Therefore, this short text will only speak generally about the tables collated for it/within it The archive itself is a text to be read by itself It is an exercise for contemplation and reflection, to ask the question – why?

History of British and British India Census

The British have been conducting numeration exercises of their population since the early ages of its monarchy (ONS, 2016). Therefore, collecting population data was not a new ordeal when the first synchronous censuses were administered, in Britain as well as its colonies

In 1086, William the Conqueror ordered a detailed survey for information that would account for only those who owned the land, where and how much land, and therefore their possessions in parallel to this (cattle, herds, and other "objects" to do with animal husbandry) to understand how much tax he could charge them. This became the Domesday Book (ONS, 2016).

In the 13th century, King Edward I divided the country into hundreds of administrative areas for a survey of the population that came to be known as the ‘Hundred Rolls’. Again, this was a list of wealthy landowners but also, far more detailed than the Domesday Book, it counted peasants and ‘serfs’ - people who were not free to leave the land where they worked It also divided people into classes, a significant change in the way enumeration of the population was conducted (Barry, 2021).

After Iceland (1703) and Sweden (1749) conducted their first official census (ONS, 2016), scholars and politicians in Britain meditated on the country’s growing population. Towards the end of the 18th century, thinkers like Thomas Malthus published an essay suggesting the country would eventually be unable to produce enough food to support its rapidly growing population (Malthus, 1798) His observations were later disproven, confirming the idea that there was no real record of the population of Britain (Barry, 2021).

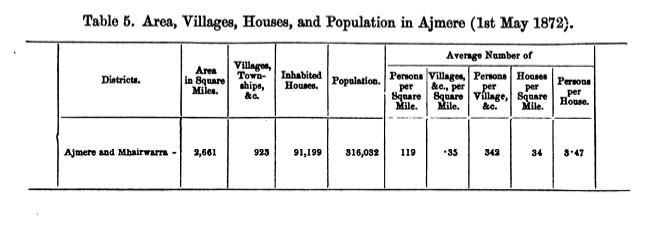

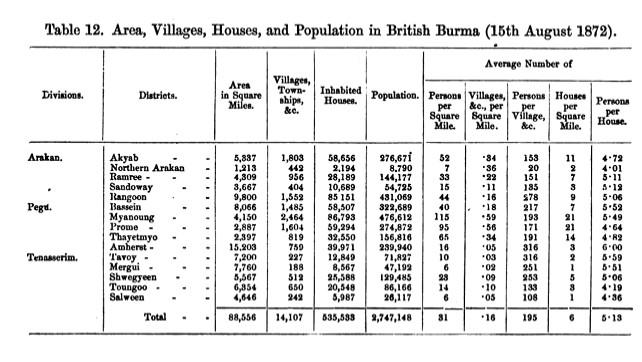

The British Empire periodically conducted 8 official censuses in the Indian subcontinent, from 1865 to 1941, since the Raj was established in 1858 until the Independence of India and Pakistan in 1947. The exiling of the East India Company from British-India in 1858 allowed for a motivation in administrative rule, and the Empire conducted their first non-synchronous census from 1865 to 1872 This census was held non-unanimously, with each province conducting their own, bringing it into one collective published survey (Bates, 1995) It is obvious in the archive, therefore, how the tables vary in information; some provinces were left out of some surveys, and some tables conducive to specific findings in a particular province

In Britain, census-taking methods had evolved since 1841 when responsibility for recording information was delegated to households Each home was delivered a form that they had to

complete by recording the details of every inhabitant These forms were then returned to an official called an ‘enumerator’ who came to collect them (The National Archives, 2016). The census records that survive today are the collected return of these forms, the information copied by hand into books 1841 also saw a significant addition to the census, asking people where they were born, not only where they lived, demonstrating the acknowledgement of mobility across the country as well as from different parts of the world (Barry, 2021).

The collection method was conducted differently in India, where enumerators were delegated to a community of households with whom they would observe and conduct the survey questions through a translator. It can be speculated that some form of conversation took place between the “collector” and “collected” to engage in a suite of understanding However, the text displays an undisputed bias in the language (Alborn, 1999) The method of observing from afar is the enumerator’s own context, own experiences, and unique set of ideals (informed mostly by the Empire) It is obvious in the text that accompanies the numerical tables in the census that it is informed by a binary perspective, not able to withstand any other system of what is acceptable and what is “right ”

Hierarchical methods such as this were a tool of the Empire to always remain in power It is said that the census was primarily concerned with administration, but the language in the text and the surveys conducted, which produced the tables, highlights an entirely different story. It becomes obvious that not the social realities of the population but rather over time, the methods of social engineering (Mann, 2015) (Bates, 1995), and therefore the census acted as an apparatus of control Categorisation becomes the method of execution for this tool.

The Violence of Categorisation

It is not unnatural for the human brain to automatically categorise, divide, subjugate, allocate, and distribute information that the subconscious mind collects It is an instinct that we have evolved with to make sense of the world that is ever-changing but also one which we need to survive. The mechanisms in our brain automatically divide what is most important, forming the conscious mind. The consciousness then acts on this “filtered” information to allow us to move forward with matters at hand It is an instinctive need for humans to act efficiently, and so the impulse to categorise becomes part of our DNA and our apparatus to conduct ourselves in the world (Anderson, 2016).

It is when power relations are attached to those categories that they become the motivation for violence (Anderson, 2016) When these categories induce hierarchies, it leads to the provocation of racism, classism, sexism, etc. These become the source for why and how power is demonstrated, ultimately deducing the population into the pyramid By placing a certain “category” in a position of power, and they become the sole bearer of that power, the other “categories” suffer under their newly accumulated influence. They have no choice but to abide, and so communities become disenfranchised in this way (Steel and Gardiner, 1898) Then, categorisation here does not speak about a method to understand populations, but to control them The conclusions drawn from biased observation become a way of telling people how to live.

The British conducted surveys that included predetermined categories, worded in a weary effort of “adopted from the native,” and presented these communities in a chauvinistic way of being. Inducing a feeling of being “othered” automatically enables resistance amongst people within communities who feel like they do not belong in their own country In the physical sense, categorisation coaxes violence where people strive for freedom, freedom from being held within the confines of binaries, freedom from being told how to speak, behave, think, and act, all of which are determined by the “Western” way of life (Tagore n d )

What is the archive?

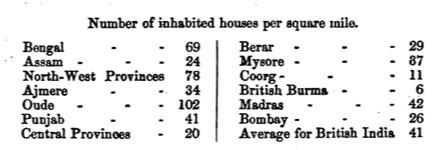

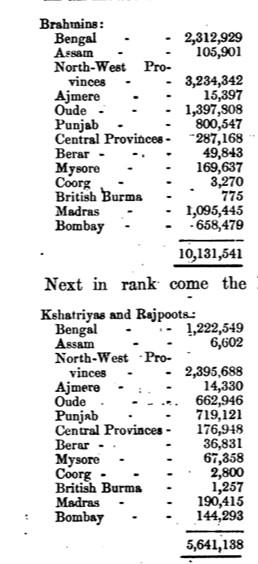

The archival piece documents each of the numerical tables drawn, written and published in the British-India census, a sample of which was created alongside this essay in 1872 The tables contain numbers and percentages, as well as categories of information in which the population of British-India was required to define themselves

The archive removes the text from the censuses, making it obvious that it contains only the methods of statistical data and "evidence". The right-hand side consists of the British India census tables, and on the left is the equivalent British Census

Obviously, the left-hand side is blank.

This is about vacancy and accountability The tables on the left are missing because they are not available in the same accessibility modes as the British-Indian census They are not available to access online. What is accessible in the digital National Archives are the forms that the public at the time sent, but the results of these censuses are not (The National Archives, 2016) The Census Confidentiality Act 1991 has prevented the census data records from being fully accessible to the general public and those on digital Internet search engines:

“An Act to make provision with respect to the unlawful disclosure of information acquired in connection with the discharge of functions under the Census Act 1920; and for connected purposes.”

(Legislation govuk, n d )

Access to the archive requires membership to the National Archive, as well as presenting a reason for access and a letter of recommendation from your research base Most of these research bases are universities, and so inaccessible to those who do not attend one Institutional systems therefore become the roadblock to accessing records that are supposedly public knowledge The blank page represents systemic inaccessibility that remains prevalent even today, and this is a secondary point the archive strives to make

The sketch attached to this essay shows one method in which the archive could be used/printed The concertina tracing paper allows users and readers to directly compare and reflect on the tables that change over time By just comparing how the tables changed over the series of censuses, it is obvious that the categories changed, adapted and became a tool for oppression

Purpose of the archive

It should be noted that this exercise is not intended as a means of perpetuating the same methods of violence. Separating the data collection methods only contributes to the same violence that was imposed when these census records were collected For the purpose of this archive, it must be acknowledged that the archive is not the "whole truth" (whatever that may be) and initiates the conversation about partial histories The qualitative text is equally significant as the quantitative numerical data, despite these not together encompassing the "whole truth" Separating the data collection methods allows us to look at the data for what it is, without the text "distracting" from the statistics that were published

The purpose of the archive is to make the reader look solely at the numbers, the "science" colonizers needed to make juridical changes within the Indian governing system The quantitative tables indicate what the colonizers were actually measuring over time By isolating the table from the text, we take away its "justification". It becomes clear how the population became divided as an exercise of categorizing, dividing, and ruling

Without the text, the census is a series of numbers made up of digits and percentages. It provides a snapshot, a binding contract between the person, a category, and the statistician who looks at and draws conclusions from their combined categorical analysis Here, there is no room to push beyond the boundaries of these categories, which may not accurately represent one's identity.

The census (and therefore the Empire) caused constitutional, cultural, and ingrained damage to the people of British-India, leading to the question of Indian identity (Roy, 1997) Misrepresenting data like the censuses did, including the methods surrounding them and the categories in which they were displayed, skews the way history is interpreted The same hierarchical methods repeated over hundreds of years changed the way a community viewed itself and others living within it.

The pan-Indian, Hindutva identity has therefore become the narrative for a "post-colonial" way to "decolonize" the country However, this identity stems from the need to disassociate from those colonial methods, to change the way the country was colonized to one that follows a narrative pre-colonization (Tuck, E and Yang, K W, 2012) The aim is to avoid falling under a definition that is not our own but forced upon us But is using the same methods to create a nation-state, one national identity, not perpetuating the same colonial methods? India has a population of 1 billion people; how can 1 billion people have one national identity? What then does it mean to be Indian? The current method of governance, nationalism, is just another form of colonialism

In this complex web of colonial, post-colonial, neo-colonial, and decolonial, what then is the point of quantification? The way the world is viewed becomes skewed towards the narrative of the capital, and present-day norms, which becomes unrealistic when comparing data from hundreds of years ago, even a few decades ago. So what is the point of measuring, statistically analyzing, and quantifying a population if that population does not fit within prejudiced, confined boundaries?

Reflection:

When accessing an archive, or dataset such as this one, it can be quite daunting without the archivist present to help navigate the document. The text, the "justification," becomes the voice of the creator and, therefore, the archivist

The archivist and creator become intertwined What is written in history becomes the way we perceive and understand it, often disregarding other forms of understanding. Alternative forms of history, such as artistic performances, ballads, poems, folk songs, drawings, etchings, pyramids, fossils, and more, are all valid methods of understanding history that help with cultural preservation and instilling moral values in the present day. Unfortunately, much of this narrative falls under "spirituality" or "religion," which tends to be disregarded in the chronology and legitimacy of history

The role of the archivist has been undertaken unknowingly by many who have not anticipated the importance of their position The creators of the census records of British-India have therefore become instigators in creating a narrative for present-day post-colonial India to try and de-colonise. The role of the archivist is transferrable and often only held by those in power, which destroys the point of an archive as we understand it to be unbiased

This raises the question: can an archive exist without bias? Can the role of the archivist ever be in the hands of those not in power?

--END OF ESSAY--

2,705 words

Reference List – Harvard formatting

“About the census” (2022) Office of National Statistics Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/census/aboutcensus/aboutthecensus (Accessed: December 7, 2022)

Alborn, Timothy L (1999), "Age and Empire in the Indian Census, 187I-1931", Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 30 (1): 6I–89, doi:10.1162/002219599551912, JSTOR 206986, S2CID 2739080

Anderson, B. (2016) “Chapter 11 - Memory and Forgetting,” Imagined Communities. London, United Kingdom: Verso Books, pp 187–206

Barry, A M (2021) “The Census through time,” The National Archives Govuk, 13 May Available at: https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/the-census-through-time/ (Accessed: December 8, 2022)

Bates, Crispin (1995), Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: The Early Origins of Indian Anthropometry (PDF), Edinburgh Papers In South Asian Studies, ISBN 1-900-79502-7

“Census (Confidentiality) Act 1991” (n.d.) Legislation.gov.uk. Statute Law Database - The National Archives Available at: https://wwwlegislation govuk/ukpga/1991/6/contents

(Accessed: December 8, 2022)

Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistics Division (ed ) (2017) Principles and Recommendations for Population and Housing Censuses United Nations Available at: https://unstats un org/unsd/demographic-social/Standards-and-Methods/files/Principles and Recommendations/Population-and-Housing-Censuses/Series M67rev3-E.pdf.

An Archive of Tables

Appendices

thick, translucent, tracing paper pages

archive pieces from different years of census put together for comparison