st IAN AMERICA

EDI t ORIA l

By January 1 next year all public school classrooms in Louisiana, from kindergartens to universities, will display posters of a Protestant version of the Ten Commandments in “large, easily readable font.” Depending on your perspective, this is either a much-needed step toward “acknowledging the Christian foundations of America” or a disturbing step toward an America in which the state puts a heavy thumb on the scale in favor of one religion.

Will this law survive the constitutional challenge that has already been filed? Almost 45 years ago the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a similar law in Kentucky, finding that its “plainly religious purpose” violated the First Amendment’s establishment clause. But the answer this time around could be different. Not only have Louisiana lawmakers attempted to frame their law as having an educational purpose rather than a religious purpose, but this Court has shown itself as less-than-friendly toward meaningful church-state separation.

with which many Hindu Indians view so-called rice Christianity. I was helping organize a visit to India by a Christian leader—a visit during which he would meet with various national and state political leaders, as well as the media.

Before the trip I researched current political and religious issues that might arise. It didn’t take me long to realize that one of the most politically sensitive religious issues in India is the perception of aggressive and unethical Christian proselytism, especially among the Dalits—members of India’s lowest social caste. And indeed, this issue did arise multiple times during the trip.

has been true, the reputation of Christianity has suffered immeasurably.

Story 2: Jesus or Jail

In the Colorado case of Janny v. Carmack, everyone agrees that someone had their First Amendment religious liberty rights violated. But who? Was it Mr. Janny, a man recently released from prison and needing a place to stay? Or was it Mr. Carmack, the director of the Denver Rescue Mission, a Christian ministry that provides for the “spiritual and material needs of vulnerable people”?

Putting aside constitutional issues for a moment, though, how should Christians feel about this new law? From a Christian perspective, could there be some social or even spiritual benefit to giving this biblical passage more public exposure?

Before we get to that question, though, consider these two stories.

Story 1: Rice Christianity

It was during a work trip to India in the early 2000s that I first began to understand the utter distain

For many years “rice Christianity” has been a slur thrown at both missionaries and new Christian believers not just in India but around the globe—from countries of Africa and Asia to the islands of the Pacific. It implies that new Christians haven’t experienced a genuine conversion but have switched religions for pragmatic reasons. It’s an insult that suggests Christian missionaries, whether intentionally or unintentionally, have “sweetened the deal” with material benefits: food, medical care, education, or the suggestion of an elevation in social status.

Questions around motivation for conversion are messiest in places in which Christian missionaries followed in the path of colonizers—whether British, American, Spanish, French, or Portuguese. Were those who embraced the Christian faith motivated by fear? by a belief that it would curry favor with their new rulers?

Unfortunately, the historical record shows that Christian mission practices have not always guarded against these evils. And where this

The facts of the case are simple enough. In 2015 a parole officer organized a bed for Mr. Janny at the mission run by Mr. Carmack. But along with the bed came certain expectations: first, that Mr. Janny would participate in Christian worship services, and second, that he would receive spiritual counseling. As an atheist, Mr. Janny refused, and asked either to be excused from religious activities or to be moved to a nonreligious shelter.

The parole officer and Mr. Carmack gave Mr. Janny a choice. Mr. Janny could comply with Mr. Carmack’s conditions, or he could return to prison. The upshot? Mr. Janny was sent back to prison, where he served five additional months.

After being released a second time, Mr. Janny sued, and in 2021 the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in his favor. The court said that the Christian shelter had violated Mr. Janny’s First Amendment rights by requiring his participation in religious activities, knowing that if he refused, his parole officer would send him back to prison.

4 A RECOVERING PRIME MINISTER

Interview with Australia’s Scott Morrison

10 THE X FACTOR Women and religious persecution

14 PARSING THE PRONOUN WARS Beyond an all-or-nothing approach

Extremists on the left and right demand 100 percent compliance with 100 percent of their views 100 percent of the time. P22

16 | PROCEED WITH CAUTION

20 | CASE IN POINT

22 | CELEBRATING COMMON GROUND

26 | THE INDIGENOUS ”OTHER”

Lawyers representing Mr. Carmack and the Denver Rescue Mission, however, had a different take on whose religious rights had been trampled. They argued that the Tenth Circuit decision violated the mission’s religious free exercise rights, forcing its leaders to decide between offering free help to people in need or compromising its religious mission and identity.

They missed an obvious irony. In many countries around the world today, oppressive regimes regularly give faithful followers of Christ a choice between Jesus or jail. In Janny v. Carmack, that same ultimatum was delivered by Christians to an atheist.

Building Authentic Christianity

The point is this: authentic Christianity is the result of personal commitments, freely made. Anything else is not Christianity.

Attempting to affix a large “CHRISTIAN” label to America by whatever means possible does not make our country more Christian. Insisting on the primacy of the Christian faith in American history does not make America more Christian. Leveraging the “Christian vote” to pass laws that favor Christianity does not make America more Christian.

And posting the Ten Commandments on classroom walls does not make America more Christian. At best it’s window dressing. At worst it confirms a growing belief that some Christians—in their determination to Christianize America—will happily run roughshod over other people’s rights and beliefs.

Building a more Christian America is much harder than passing ten-commandment laws, and comes with no guarantee of success. Building a more Christian America requires the authentic transformation of lives, one by one. It requires Christians to reject anything that smacks of coercion. It requires humility of spirit. It requires Christians to follow in the footsteps of the Carpenter of Nazareth, who mingled with people, showing sympathy and compassion—no strings attached—and then, and only then, inviting them to follow Him.

Bettina Krause, Editor Liberty magazine

Please address letters to the editor to editor@libertymagazine.org

DECLARATION

ofP rinciples

The God-given right of religious liberty is best exercised when church and state are separate.

Government is God’s agency to protect individual rights and to conduct civil affairs; in exercising these responsibilities, officials are entitled to respect and cooperation.

Religious liberty entails freedom of conscience: to worship or not to worship; to profess, practice, and promulgate religious beliefs, or to change them. In exercising these rights, however, one must respect the equivalent rights of all others.

Attempts to unite church and state are opposed to the interests of each, subversive of human rights, and potentially persecuting in character; to oppose union, lawfully and honorably, is not only the citizen’s duty but the essence of the golden rule–to treat others as one wishes to be treated.

Interview with former Australian prime minister scott Morrison

On the wall of his office in Australia’s Parliament House, Scott Morrison hung a framed newspaper dated May 1, 2019, proclaiming: “ScoMo’s Miracle!”

It was a headline that appeared the morning after Morrison’s poll- and pundit-defying election to Australia’s top political job. The evening before, Morrison had stood before a cheering crowd at a hotel in Sydney and accepted his unexpected win with the words, “I have always believed in miracles!”

In the months and years that followed, though, divine intervention sometimes seemed in short supply. The COVID pandemic, various international crises, devastating wildfires and floods—even a mice plague that threatened Australian farming—turned Morrison’s tenure as the nation’s thirtieth prime minister into an approval-ratings roller coaster ride. At one point, with his administration’s tough COVID policies protecting Australians from the high mortality rates experienced by almost every other nation, Morrison’s approval ratings were the highest of any Western leader. At other times, though, his approval ratings scraped the bottom end of the scale.

Yet there has been one constant throughout Morrison’s almost 16 years in federal politics: his Christian faith.

As Australia’s first Pentecostal Prime Minister, Morrison displayed his religious devotion openly and, at times, exuberantly. And this within a largely secular culture, where public displays of piety are often treated with suspicion, if not disdain.

Bettina Krause, editor of Liberty magazine, recently talked with Mr. Morrison about how he has sought, through the years, to combine two very different identities: man of faith and hard-charging political partisan.

Reflections Recovering Prime Minister

Bettina Krause: It seems to me, reading some of the many articles that have been written about you—especially when those articles touch on your religious beliefs—that there’s a deep sense of unease with any expression of faith within the context of Australia’s public life. Can you help our North American readers understand why this would be so?

Scott Morrison: Yes, that’s an important observation. Australia is culturally quite different from the United States. It’s more like New Zealand or Canada, I suspect, but also the United Kingdom. Here in Australia there’s a view that faith should be a private matter. It’s not something that should ever be raised publicly, particularly when one is in public life. Now, I had a different view. My view was never, “Oh, vote for me because I’m a Christian.” My view was that I am a Christian and I should be transparent about that. I never sought to proselytize from the speaker’s box in the Parliament or in any of my other roles. But neither was I shy about it.

I received enormous support from many Christians around the country and well beyond our shores—I think they got what I was trying to do. But there is a strong element within Australia, and not just in politics but in the media as well, that is very hostile to this idea, extremely hostile to it.

Krause: You went on the record, numerous times, saying that the Bible is not a public policy book, yet your policy positions were sometimes painted as being influenced by your faith. Was there an element of truth to that? Because your faith is going to inform your moral sensibility and you’re going to bring that sensibility to the issues you face in office, right? Or can you keep those two things compartmentalized?

Morrison: Well, I don’t think there’s so much of a conflict. I mean, Western societies, representative democracies, are founded on JudeoChristian values—issues of human rights, justice, personal responsibility, individual liberty. And those are also values that inform who I am as a Christian. There is a foundational set of values that I would say are entirely necessary to our society. But beyond that, everyone has to work out what they believe is the best way, in a policy sense, to achieve those things. And I certainly know many Christians—and other people of faith—who wouldn’t share all of my political or policy views.

I never sought to ascribe an evangelical, let

alone a Christian, bent to my policy positions. I never thought to explain them in that way or seek to justify them that way, either. Australia is a secular country, as is the United States and most Western democracies, and for very good reasons. But I said in my maiden speech to Parliament: “We have no national religion, but that doesn’t mean secularism is our religion either.”

I do feel that, over time, secularism has almost been elevated to the religion of the state. And I think that’s wrong. I think that’s in direct conflict to what, in Australia’s case, was intended at federation. Or, in the United States, what was intended by those who wrote the Constitution.

Krause: Some perceived you as “too Christian,” yet, ironically, some of your most vitriolic critics were other Christians, right?

Morrison: I remember I got off a plane one day and ran into a former member of Parliament— one from the generation before me—who was at odds with a particular policy position I’d taken. I was minister for immigration at the time. And so he proceeded to lecture me on the position, but then started to lecture me on my faith. And I said, “Well, mate, you have every right to question me on my policies, but you don’t have a right to question my faith. Only God can decide that.”

I often found other Christians who weren’t involved in politics asking, “Oh, is this person a Christian? Is that person a Christian?” I’d reply, “Well, it’s not for me to say. That’s between them and God. And if I tell you they are a Christian, are you going to have a different view of them and their policies? No, judge them on their policies and judge them on their character and judge them on what they’re doing.”

Krause: I have to ask you something I became more and more curious about as I read your book. It’s very clear that you have absolutely no illusions about the nature of politics. You call it “driven by ambition,” and you talk about how the “game” of politics often becomes an end in itself.

Morrison: True.

Krause: All these things you describe are basically the opposite of Christian virtues. If you were to advise a young person, a Christian young person, who wanted to go into politics, what would you tell them? Can they maintain their Christian integrity and still be an effective politician?

Morrison: Well, it’s not easy, and it’s not getting any easier. And this goes back to the first question you asked me. In the United States there’s still a strong element of cultural Christianity and the practice of Christianity. But in Australia, Canada, or New Zealand, for instance, it’s clearly now less than half of the population that makes even a nominal profession of affiliation with the Christian faith.

For 1,500 years Christianity has been the dominant influence in Western culture. That is now changing, and we’re becoming a minority. Rod Dreher talks about that in his book The Benedict Option, and this has become a fairly consistent theme in a lot of the literature around these issues: we’re not in Jerusalem anymore, we’re in Babylon now. And we need to live with that reality.

So that’s why there are two things I’d say to any young person contemplating a life in politics. First, get on your knees and pray.

When I was a [Liberal] party director and I was recruiting candidates, I had the tactic of trying to talk them out of it. Perhaps they were simply excited about all that goes along with politics, or they were just ambitious. I’d say to them, “Well, let me walk you through a few things. Let me tell you about how many marriages fail, about the pressures on mental health, about how long you’re away from home and family, about how many disappointed ambitions there are in politics.”

Politics doesn’t end well for most. You rarely get to choose the time of your exit, but that’s just the nature of it. And so you have to go into this with your eyes wide open. You need to feel quite convicted in your own heart and your own spirit that this is where you’re being led.

And second, I’d say to them, “Just because you think God’s calling you to a life in politics, don’t think that means everything is going to just fall into place for you.”

I’ve always admired William Wilberforce. You read his biographies, and this is a guy who was enormously capable. But he was called to a life on the backbench, tirelessly advocating and campaigning. He found himself constantly as a go-between between both sides of politics and the Parliament at the time. Why? To pursue his one big goal: the abolition of slavery. He made that choice. He was extremely good at politics, but he spent most of his time being attacked by others.

Politics doesn’t end well for most. You rarely get to choose the time of your exit, but that’s just the nature of it.

You have your eyes wide open. Just because God’s calling you into politics, it will still be potentially quite difficult. It may not be the path you thought it would be.

Krause: Following on from that, it’s fair to say that your own path as prime minister was, at times, a difficult and bumpy one. And in your book you mention times, moments of crisis, that you really sought strength and clarity through your faith.

Morrison: I have always been absolutely befuddled by how my colleagues who didn’t have a faith survived. We had a Bible study group that used to meet in my office, from the time our party was in the opposition all the way through to the time I was prime minister. And then again, after I lost the election [in 2022], we kept meeting in my office. We were a great support and encouragement to each other. And for those who don’t have that, I really don’t know how they survive that environment. Because it’s a very isolating environment. It’s a brutal and competitive environment. You’re away from your family and your support structures. And you’re pretty vulnerable. There were so many moments I relied on my faith. I found during many of the crises we

faced, I just seemed to be able to slow things down in my head. It was a bit like seeing the ball come toward you a little more slowly than it did. And with the fast pace of information moving around, I’m just very thankful that God enabled me, I believe, to process that information well and make the best possible decisions I could. And I would pray for that. I would pray that God would prepare the ground upon which I would walk tomorrow. I would pray that prayer a lot, not knowing what tomorrow would bring. All I needed to know was that He would go before me. Now, if you say this type of thing within a non-Christian environment, people think , Oh, you’re just praying that you’ll be successful every day. No, I was praying that I would have God’s presence each day, that I would have His encouragement. And regardless of whatever happened, I would still have His presence, His encouragement, and His peace.

Krause: You write in your book about the connections you made with fellow world leaders who shared your experience of both being a person of faith and carrying the burden of high office. How important were those friendships to you?

Morrison: They were extraordinarily important. I spent a reasonable amount of time with James Marape, who’s still the prime minister there in Papua New Guinea, and this was a very special relationship. And then I had what I call my “favorite Mikes”—Pence and Pompeo [then U.S. vice president and secretary of state]. I met Mike Pence at an APEC [Asia Pacific Economic Council] Summit at a time that, frankly, no one there had any good reason to give me the time of day, and we’ve remained connected ever since. These sort of diplomatic functions can be tedious affairs. But there we were, seated together after a wonderful meeting earlier in the day, and we just sort of connected. And the same was true with Mike Pompeo. Mike came out to Sydney with his wife, Susan, and we had dinner together at the [prime minister’s] residence in Sydney. Susan came to church with us the next day, and Mike was a bit upset that he couldn’t come too—he had to work that Sunday morning with my foreign minister. But those sort of relationships in politics go deep quick. You recognize each other, and you get that you’re on a similar path.

Krause: There’s one issue that was particularly difficult during your time in office, one that stemmed, in part, from Australia’s 2017 recognition of same-sex marriage. And that’s

the question of religious freedom in relation to LGBTQ rights. In America we’re having similar debates: how we can protect religious freedom when people have traditional views of human sexuality, while at the same time making sure that LGBTQ folk are protected from discrimination. Is there a way forward for Australia on this?

Morrison: Well, these protections were previously never really necessary, because Christianity was the dominant culture in Australia. But that has really shifted, and there are many things that have contributed to that. When you become a minority culture—well, you need a bit of a reality check. You have to change your expectations around what laws should be in place. We’re a representative democracy. We’re not a Christian theocracy. And in a representative democracy, the majority rules.

But then, at the same time, majorities don’t get to rule with tyranny in a democracy. The majority doesn’t get to impose how people should think or believe.

I was incredibly devastated that we were not able to pass these religious freedom protections, because I was simply seeking to make that balance. We already had anti-discrimination laws that applied to gender, sexuality, race, and things of this nature, but not as applied to religion. And I was seeking to apply the same protections to religion as well. We were unsuccessful in that. And I don’t believe [the current government] will be successful in changing these laws now.

Krause: In your final speech before leaving Parliament earlier this year, you spoke about the fact that society is becoming increasingly disconnected from its religious values and heritage. Can you speak more to that?

Morrison: I chose to speak on this because I also spoke about it in my maiden speech to Parliament. So it sort of rounded off my almost 16 years in Parliament, as I saw this issue continue to morph over that period.

There’s no doubt that Western society’s values and principles have their origins in the Christian and Jewish faiths. No historian would argue to the contrary on that. But over time, I think in the West in particular, we feel as though we’ve outgrown it a bit. And so now we’ll pick and choose a bit more. But once you start doing that, frankly, the intellectual rationale for what you’re talking about starts to crumble. And this idea of having one’s own truth, well, where does that end? If there’s no objective standard around truth, if there’s no objective standard around

the key principles of morality and life and the dignity of humans, if they’re not anchored or deeply rooted into anything of substance, well, they just blow away. And that really concerns me, and not just as a Christian. It concerns me as an Australian. It concerns me as a citizen of a Western representative democracy, seeing something that has been our greatest strength being diluted before our very eyes.

President Biden is right when he talks about the contest between autocracies. And I would put it more in this way: it’s a contest between autocracy and freedom. The contest between autocracy and freedom is real. Freedom is about liberty, and I think, from a Christian point of view, it’s about love and care for one another.

Autocracy is about power. And in that fight between love and power, you’ve got to know what you believe. I know the result of those who believe in power. I know what they’re prepared to do. I came up against them, particularly in the form of the Chinese Communist Party. And they’re not kidding. They’re very serious. And in our Western democracies I think we need to understand where our strength resides in order to resist this.

So I worry about that disconnect. When you start chipping away and picking and choosing— or, as it says in Romans 1:25, exchanging the truth of God for a lie—well, I fear we’ve sort of cut that rope and we’re just drifting. Where are we drifting? Who knows?

This is the world we’re living in. Is it really that different from the world that Jesus and His disciples were living in? Is it really that different from the world that Daniel, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego were living in, or the world that Esther was living in? No, probably not.

So what did they do and how did they approach it?

One of the things I always found fascinating about people like Daniel and Joseph is they didn’t try to take over the government. They didn’t try to stack the Parliament. They didn’t engage in some sort of Christian political contest. They were faithful. They did their jobs well. They were respectful of authority. They cared for others. They held to their relationship with God. And they didn’t compromise their identity in who they were in God. They stood firm. And where the regime fell afoul of those things, well, they stood their ground. And they knew they’d either end up in the fire or whatever the case may be. And I think that’s a similar call to us.

So my message is: God does have a plan for us. We need to know who the Author of that plan is, and we need to hold on to it.

the

By Lou Ann Sabatier and Judith Golub

What do these individuals have in common?

Gulmira Amin. Wife and moderator of a Uyghur news and cultural website who is imprisoned for her ethnoreligious identity and protesting against the Chinese government’s treatment of Uyghurs. She is serving a 20-year sentence in the Xinjiang Women’s Prison.

Mahsa Amini. A 22-year-old Kurdish Iranian woman whose death in police custody sparked a national movement. She had been accused of violating Iran’s mandatory hijab dress code.

Mariam Ibrahim . A Sudanese Christian mother who was arrested for apostasy, imprisoned with her nine-month-old son, and sentenced to death. She gave birth to her second child in prison before an international outcry resulted in her release.

Rhoda Jatu. A Nigerian woman who was jailed for a perceived blasphemous message she sent via WhatsApp in response to the religiously motivated murder of Deborah Yakubu. She was granted bail after being detained for more than six months and was relocated to a safe, undisclosed location.

Saba Masih. A Catholic girl from Pakistan who was kidnapped at 15 and forced to marry and convert to Islam. Pakistani police are reportedly refusing to help.

Akhtar Sabet. A daughter and an Iranian nursing student who was expelled from university without receiving the associate degree in nursing she had earned. She was later hanged because of her Baha’i faith.

Let’s look in more detail at Akhtar Sabet’s story. On June 18, 1983, the Iranian government executed Akhtar along with nine other Baha’i women. Their names were Mona Mahmoudnejad, Roya Eshraghi, Simin Saberi, Shahin (Shirin) Dalvand, Mahshid Niroumand, Zarrin Moghimi-Abyaneh, Tahereh Arjomandi Siyavashi, Nosrat Ghufrani Yaldaie, and Ezzat-Janami Eshraghi. The women’s ages ranged from 17 to 57.

What was the crime they had each allegedly committed? They had refused to renounce their faith. Each woman was forced to witness the death of the

Factor

Mapping the unique experiences of women and religious persecution

Women and girls make easy targets when a regime believes its power is on the line.

woman executed before them. They were each hanged by executioners employed by the Iranian government. It must have taken incredible strength for a daughter, Roya Eshraghi, to witness the execution of her mother, Ezzat-Janami Eshraghi. Yet she, along with the others, did not recant her faith.

Last year, on the fortieth anniversary of their execution, the Baha’i international community launched the #OurStoryIsOne campaign to honor and celebrate all Iranian women, regardless of faith and background, who have contributed to freedom of conscience and gender equality over the years.

Like Akhtar Sabet and the other nine Baha’i women, the women and girls whose names are mentioned above have all had their freedom of religion or belief cruelly violated. They represent tens of thousands of others, both named and unnamed, in countries worldwide who have experienced profound human rights violations because of their religious beliefs or nonbelief. These violations—many of them gender-focused—have included discrimination; forced marriages and religious conversions; rape; sterilization; the denial of access to education, health care, and work; and imprisonment, torture, and even death.

Some well-known advocacy organizations have recently sought to better understand the interaction between gender and persecution based on freedom of religion or belief. These groups include the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) and several United Nations special rapporteurs on freedom of religion or belief, along with the All-Party Parliamentary Group for International Freedom of Religion or Belief; Open Doors International; Aid to the Church in Need; Stefanus Alliance; and FoRB Women’s Alliance—the group with which we are affiliated. (FoRB stands for “freedom of religion or belief,” which is what religious freedom is commonly called within the international community.)

The collective findings are clear: Women and girls experience compound persecution because of both their religion and gender, as well as political and economic stressors, and cultural norms that masquerade as religious dicta. Governments often commit and/or tolerate these violations. Authoritarian regimes often feel threatened by women and girls who, despite their marginalization, are key to the strength and continuation of families, communities, and cultures. As a politically less powerful group, women and girls also make

easy targets when a regime believes its power or authority is on the line.

Persecution also takes place behind closed doors, in households and within communities. Family or community members are frequently the perpetrators, and their abuses are especially difficult to uncover. They often go unreported or underreported. The perpetrators in these cases are often less likely to be held accountable than those who commit violations against men.

In 2023 the FoRB Women’s Alliance conducted a global multifaith study of women and freedom of religious or belief, in partnership with the London-based advocacy group Gender and Religious Freedom.

Our study set out to explore the advocacy work currently being undertaken in this space— largely by women and girls, many of whom are active at the grassroots level. Our goal was to create a preliminary mapping of advocates and practitioners. We also aimed to chart the challenges of working in this area, and opportunities for empowering and accelerating this work.

Without this type of research, which documents the current landscape, those who are trying to make practical differences in communities worldwide will continue to face the same obstacles again and again.

Our research revealed roadblocks that women and FoRB advocates repeatedly encounter, but it also uncovered some hopeful avenues for future action. These roadblocks—and the innovations needed to overcome them—speak to the systemic nature of the existing challenges. These challenges are faced not by one or another religious group, here and there, or by a particularly disadvantaged group of women. They are global challenges, impacting women and girls and their communities worldwide.

Here are five key findings from these conversations with women and men around the world about how we can best advance freedom of religion or belief for women.

Key Finding 1: FoRB advocacy often takes place in a “silo,” unconnected with advocacy for other human rights, such as women’s rights. Across cultures and geographies, women and girls with minority beliefs face significant discrimination and persecution by means that are linked to their gender. In many places women additionally receive little or no education about their legal rights, and too often they suffer from the effects of violent, complex, and hidden attacks because of their chosen faith or belief. Participants in this FoRB research study underscored all these facts. Yet being a female

does not lessen a person’s human right to freedom of religion or belief.

The forms of FoRB-related persecution that women and girls face are further buried by the way various advocacy groups often operate within “silos.” There is often little collaboration between those who would speak on behalf of women in the courts, the political realm, and even within their religious community. In addition, the false division between freedom of religion or belief and women’s rights also impedes advocacy efforts.

Key Finding 2: The exclusion of women from power structures also undermines efforts to address FoRB violations committed against women and girls.

Historically, efforts to address FoRB violations have excluded women and their genderspecific concerns. While numerous nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), think tanks, and humanitarian groups focus on defending and advancing FoRB generally, male leadership of the FoRB movement, including in the West, has often dominated the space. Many NGOs and leaders of the FoRB movement fail to comprehensively integrate women at every level. Women have not been equal participants in decision-making, nor have they had equal access to information about FoRB violations. The result is that those women who advocate for their FoRB rights have often found their efforts thwarted, undermined, underresourced, or unacknowledged.

Key Finding 3: Cultural norms masquerading as religious dicta can be creatively and courageously challenged.

There are passionate, committed, and gifted people working to build positive change alongside those women and girls most affected by FoRB violations by addressing belief systems and mindsets based upon patriarchal and religious norms. There are good examples available of grassroots projects and training curricula that can be shared with others in this field. Participants in our study called for more support for these creative and courageous programs— especially at the grassroots level. These efforts require a deep commitment from all who are willing to engage, as creating lasting change is challenging and requires a huge investment of resources and time.

Key Finding 4: Collaboration is a form of empowerment and can increase capacity, influence, and relief.

When communities facing FoRB violations can connect across locations, regions, and

nations to collaborate, the results can be significant. From the participants in this study, there was a clear request to have a shared platform or collective. This would allow collaboration and partnership, access to training, support in advocacy, shared innovations, and access to entry-point resources. This desire to work in collaboration was evident in the examples study participants gave of their current practices and future strategies.

Key Finding 5: An external catalyst is needed to make the structural changes necessary to accelerate advocacy in this space. Women, who are so often disempowered, do not have the necessary resources to “create a space for themselves at the table.”

To accelerate FoRB across the globe, the vitality and capacity of women and their advocates must be brought to the “banquet.” They must be able to speak and act for themselves and their communities; they must be represented, understood, resourced, and activated. This can happen only when women have access to resources that will allow their skills and ideas to flourish. They must be given access to places of power and be involved in decision-making about policies, laws, budgets, and processes.

The Road Ahead

This groundbreaking report encapsulates the experiences of research participants who are working to advance religious freedom or belief for women. Based on this, we have also developed specific recommendations—for both civil society groups and governments—that address each of the challenges above. These are concrete recommendations focused on training and education, funding, sharing data and resources, and amplifying the voices of women in all aspects of advocacy work. The full report, including recommendations, can be found at forbwomen.org.

Since women account for more than half of the world’s population, it is incumbent on activists, NGOs, and governments to incorporate gender perspectives when addressing religious freedom violations. Now, for the first time, we have a vivid picture of the landscape we face, both its challenges and successes. And most important, we have a road map forward.

Lou Ann Sabatier and Judith Golub are cofounders, along with Farahnaz Ispahani, of FoRB Women’s Alliance. FoRB Women’s Alliance is a global community of religious freedom and human rights advocates and future leaders with a shared vision: advancing freedom of religion or belief for women. As a global human rights accelerator, we work across countries, regions, and sectors to increase the impact of stakeholders working on issues focused on the intersection of FoRB and women’s rights.

Parsing the Pronoun Wars

A state court resists an all-or-nothing approach.

By Charles J. Russo

Controversy continues in courts across the nation over pronoun use for transgender students in public schools. It’s a controversy that state legislatures are increasingly engaged with as well. In April, for instance, Colorado adopted a law—which is certainly likely to be challenged—requiring teachers to use students’ preferred pronouns regardless of their own ethical or religious beliefs.

A recent decision by the Supreme Court of Virginia, though, suggests a potential way forward in dealing with what has become a hot-button cultural and political issue. In Vlaming v. West Point Board of Education, decided December 14, 2023, the court upheld freedom of religion, conscience, and speech. Relying on Virginia law, the court reinstated the claims of a high school teacher, Peter Vlaming, who was fired because he was unwilling to call a biological female known as John Doe, who was transitioning to male, by the student’s preferred male pronouns.

A Zero-Sum Attitude

Vlaming, a popular sixth-year French teacher at West Point High School, about 35 miles east of Richmond, consistently earned positive evaluations resulting in his achieving continuing contract, or tenured, status. However, conflict arose early in the fall of 2018 when Vlaming

learned that Doe wanted to be identified by masculine pronouns. To avoid violating his faith while accommodating, and not offending, Doe, Vlaming used the masculine French name he assigned Doe in class in lieu of a pronoun. To limit the risk of Doe feeling singled out, Vlaming also rarely, if ever, used third-person pronouns to refer to any students during class or while the student being referred to was present. Outside of Doe’s presence Vlaming referred to Doe using pronouns aligned with Doe’s biological sex.

When Doe complained, administrators trammeled Vlaming’s religious rights, charging him with insubordination for noncompliance with their written directive to use the student’s preferred pronouns. On December 6, 2018—a few weeks after school officials suspended Vlaming—the school board voted 5-0 to fire him, ignoring an outpouring of support from students and parents for the teacher.

When Vlaming sued the school board and administrators, most notably for violating his free exercise, free speech, and due process rights under Virginia’s constitution and statutes, a trial court in Virginia dismissed his claims as meritless.

On appeal, reversing in favor of Vlaming, the state’s high court found that “in the Commonwealth of Virginia, the constitutional

right to free exercise of religion is among the ‘natural and unalienable rights of mankind.’ ”

Rejecting the board’s argument that Vlaming forfeited his free exercise rights at work, the high court declared that Virginia’s constitution “seeks to protect diversity of thought, diversity of speech, diversity of religion, and diversity of opinion.” The court specified that “absent a truly compelling reason for doing so, no government committed to these principles can lawfully coerce its citizens into pledging verbal allegiance to ideological views that violate their sincerely held religious beliefs.”

Continuing on, the court explained that “it is a ‘cardinal constitutional command’ that government coercion, even when indirect, cannot constitutionally compel individuals to ‘mouth support’ for religious, political, or ideological views that they do not believe.” The court added that “compelling an educator’s ‘speech or silence’ on such a divisive issue would cast ‘a pall of orthodoxy over the classroom’ on a topic that has ‘produced a passionate political and social debate.’ ”

The court pointed out that because Vlaming’s “free-speech claims involve an allegation of compelled speech on an ideological subject, we hold that the circuit court erred when it dismissed Vlaming’s free-speech claims.” Consistent with 2023’s 303 Creative v. Elenis, wherein the Supreme Court ruled that a Christian wedding website designer in Colorado could not be compelled to offer her services to a same-sex couple, the Virginia panel observed that the board could not require Vlaming to speak in a way offensive to his conscience.

Emphasizing that Vlaming’s dismissal violated his due process rights under Virginia’s constitution, the court commented that “no clearly established law—whether constitutional, statutory, or regulatory—put a teacher on notice that not using third-person pronouns in addition to preferred names constituted an unlawful act of discrimination. . . . If the government truly means to compel speech, the compulsion must be clear and direct.” Moreover, the court noted that the board breached Vlaming’s contract in firing him for asserting his rights to free exercise, free speech, and the Virgiania’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act (VRFRA).

All seven members of the court agreed to reinstate Vlaming’s free exercise claims.

Growing Judicial Consensus

Earlier in 2023, in Kluge v. Brownsburg Community School Corporation, the Seventh Circuit vacated its original opinion upholding the dismissal of a teacher in Indiana who

referred to students by their last names, rather than their preferred pronouns, because of his religious beliefs objecting to transgenderism. The court relied on 2023 Supreme Court precedent from Groff v. DeJoy, requiring the U.S. Postal Service to accommodate an employee by granting him time off for worship on Sundays. In its brief 130-word opinion the court found that the board violated the teacher’s rights by failing to accommodate his religious beliefs.

Previously, in 2021, in Meriwether v. Hartop, the Sixth Circuit upheld the right of a faculty member in Ohio to not violate his religious beliefs by using pronouns with which he disagreed. Reversing an earlier order in their favor, the court reasoned that officials transgressed a Christian faculty member’s right to academic freedom in sending him a written reprimand over his alleged noncompliance with university policies mandating that instructional staff address transgender students by their preferred pronouns reflecting their asserted gender identities. Viewed synoptically, Vlaming, Meriwether, and Kluge agreed that directing educators to use pronouns inconsistent with their faiths violated their constitutional rights.

Case Reflections

Amid emerging judicial consensus, hopefully legislative responses will address pronoun use respecting freedom of religion, conscience, and speech. Doe and others who are transgender certainly have the right to live as they wish. Even so, advocates cannot ignore the twin freedoms of religion and speech by seeking to compel others to communicate using words with which they disagree, especially if their objections are faithbased. The key is for all to respect the diversity of opinion of which the Vlaming court wrote instead of demanding rigid conformity to one viewpoint.

Whether Vlaming is a game-changer remains to be seen because, having been resolved under Virginia law, it is unlikely to impact federal precedent. Still, Vlaming can be a trendsetter if people of good will on both sides of this challenging issue take the court’s rationale to heart by demonstrating respect for freedom of religion and speech, bedrocks of our constitutional system, along with mutual tolerance for differences of opinion.

Charles J. Russo, M.Div., J.D., Ed.D., is the Joseph Panzer chair in education in the School of Education and Health Sciences, director of its Ph.D. program in educational leadership, and research professor of law in the School of Law at the University of Dayton. He can be reached at crusso1@udayton.edu.

the key is for all to respect diversity of opinion instead of demanding rigid conformity.

By Stanley Carlson-Thies

The Biden administration recently has revised the regulations that govern how faith-based organizations can participate in federal, state, or local social service programs funded by federal dollars. These rules cover a broad range of services, from low-income housing and workforce development programs to welfare and homeless services, after-school programs, and more.

That’s a wide and important sweep of services, so it is vital that the rules do not push out faith-based organizations that desire to work with government as a way of serving their neighbors. Some experts have sounded the alarm about the revisions, concerned that organizations will not be able to hire staff faithful to their religious standards and that their ability to offer services reflecting their religious inspiration is being suppressed—just at a time that the U.S. Supreme Court is warning governments not to restrict religious organizations more than secular ones.

The Biden revisions do have troubling elements, and faith-based organizations should

take note. But ministries should not be deterred from operating in the public square to the good of people in need and the common good of our society.

From “No Aid” to “Equal Opportunity”

A revolution has occurred over the past 30 years in the church-state rules for government funding. A “no aid to religion” principle, thought to be required by the First Amendment’s establishment clause, has been replaced by an “equal treatment” requirement: faith-based organizations, even houses of worship, are eligible to partner with government. But can the services funded by government, services the government has decided should be available to everyone with some particular need, include religious teaching and activities? After all, some of those in need—the beneficiaries—may object to those teachings or to all religion. How then will they receive help?

A solution was devised in 1996 and, though imperfect, has continued as the baseline. Called Charitable Choice, it was signed into law by President Bill Clinton that year as part of federal

Faith-based charities come

to grips

with new church-state rules for government funding.

While faith-based providers are welcome to participate, their religion must be kept to the side.

welfare reform and later added to some other federal programs. When President George W. Bush created the White House Office of Faithbased and Community Initiatives and faithbased centers in major federal agencies, he used the regulatory process to apply this Charitable Choice solution to all social services funding administered by those nine major agencies or by state and local agencies that work with them. These “equal treatment” regulations have been modified several times, and now by the Biden administration.

“Direct” and “Indirect” Funding

With these baseline rules, faith-based organizations could compete for funding in the same way as secular social service providers—with their religious identity specifically protected. When a faith-based organization was awarded a government grant—called “direct” funding—it could offer religious teaching and activities to beneficiaries, but it could not incorporate the religion into the government-supported social service nor require beneficiaries to participate in it. And a beneficiary who objected to the faith-based provider could ask the government for a referral. Most of the time this is how federal funding supports social services. One or two organizations receive funding to provide the social service in some area, with no attempt to provide choices.

But sometimes choice is a key feature. The government offers vouchers or scholarships to beneficiaries, and they select a provider, whether secular or religious. With such “indirect” funding, a faith-based provider can incorporate religion into the federally funded service, and then beneficiaries have the option of picking a wholly secular service or one that includes religious activities and religious teaching. This is how federal dollars support higher education, allowing students to take their federal aid to deeply religious colleges and even seminaries, and how federal dollars support childcare for poorer families, enabling families to choose church-based care if they wish. The Bush administration developed a drug treatment program, Access to Recovery, that offered beneficiaries a range of services, some of which incorporated religion.

But the usual practice is “direct” funding, and so, while faith-based providers are welcome to participate, their religion must be kept to the side. They can offer, say, biblical teaching on dealing with workplace challenges or urge a commitment to God as a person wrestles with an addiction, but this cannot be the core of the service supported by federal dollars. And this means that, in effect, many faith-based providers are excluded, even though there is supposed

to be a level playing field, an equal opportunity to compete for federal funding.

Is There a Better Way?

In a series of decisions, the U.S. Supreme Court has buried the old idea that government should privatize religion. Instead, it has ruled that if a state offers funding so that playgrounds can be resurfaced, it cannot simply refuse to award the support to a church (Trinity Lutheran Church v. Comer, 2017). If, to combat the spread of COVID-19, a government restricts gatherings, it cannot privilege secular meetings over religious ones (Tandon v. Newsom, 2021). If a state makes support available to private, and not only public, schools, it cannot exclude religious schools because they are religious (Espinoza v. Montana Dept. of Revenue, 2020) or because their teaching is religious (Carson v. Makin, 2022).

What does this reading of the First Amendment entail for social services funding? The current Court has not yet ruled on such a case. And the social services situation is distinct, in my view, because usually only one provider is funded for a locale, unlike the variety and choices with playgrounds, gatherings, and schools. If a provider that incorporates religion into its services gets the grant, what happens to the beneficiaries committed to a different religion or to none?

Responding to the Court’s interpretive trajectory, the Trump administration changed the regulations to expand faith-based participation. The rules had required faith-based, but not secular, providers to bear the burden of facilitating referrals and to inform beneficiaries of their rights. However, the Trump rules simply dropped these requirements instead of spreading the burden of fulfilling these important tasks. Under the Trump administration regulations, funding would be deemed “indirect,” allowing faith-based providers with services that incorporate religion to participate, if beneficiaries could choose among providers—even if all of the choices were religious. And the beneficiaries would have to participate in the religious elements if these were important to the service.

But now the Biden revisions have reversed those Trump changes—in part. The referral and notice requirements have been restored, but in an even-handed way: secular as well as religious providers must give the notice of rights, and it will be government agencies, not the faith-based providers, that will facilitate requested referrals.

The “indirect” funding changes were changed again. Beneficiaries are again free to refuse to participate in religious activities incorporated into a social service. And for funding to be considered “indirect” such that faith-based providers with

services that incorporate religion can participate in the federally funded program, the presence of a secular option for beneficiaries will be important—but not essential. The administration says this: If it turns out that some of the participating providers do include religion and some of the beneficiaries need a secular choice, then the government must find for them a secular alternative— or it might instead demand that the faith-based providers push all of their religious teaching and activity out of the funded social service as if they had accepted a “direct” funding grant.

This is not a viable solution. Many beneficiaries will need a secular choice, which cannot be conjured up at will. And breaking a signed agreement with a faith-based provider and requiring it to drastically reconfigure the service it had promised to deliver is an unacceptable demand that surely violates administrative law. But the Trump arrangement also was not viable. To be sure, faith-based organizations whose services include religious elements ought not to be sidelined, excluded from partnership with government. What they offer might be just what some or many beneficiaries desire to receive; what they offer may best fulfill the purposes of the funding: effective social services. And yet it cannot be right that when the government provides funding so that everyone with some particular need can be assisted, some or many of those people will discover that the only available provider has incorporated into its social service various religious activities and teaching that are religiously unacceptable.

The underlying problem is that there are too few choices in government-funded social services. It would be better for faith-based providers, and also for beneficiaries, if the default pattern was “indirect” funding that offers multiple choices to beneficiaries, who, after all, are themselves diverse in convictions, needs, expectations, values, and preferences. This does not require an elaborate system of vouchers, but it does require that government officials recruit diverse providers and have ready a nonreligious social service for those beneficiaries who seek such.

What About Hiring?

It is well established that a faith-based organization that accepts government funds does not give up its Title VII freedom to use religious criteria in its employment policies. The Court, in its Bostock decision (2020), ruled that Title VII’s ban on sex discrimination in employment entails a ban also on discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, although the Court added that it was ruling only about secular employers. May, then, a faith-based provider that has religion-based conservative standards

concerning sexuality decline to hire, for instance, an applicant in a same-sex marriage? The Trump administration modified the funding regulations to affirm that such action would not constitute illegal job discrimination. The Biden administration, in revising the regulations, stressed that it held the opposite view. So it took the Trump language out of the regulations—but it did not add new language obligating faith-based providers to hire without regard to sexual orientation and gender identity. Faith-based organizations already know the Biden administration’s determination to advance LGBTQ rights. What is binding, though, is the actual regulatory language. Further, as the administration knows and acknowledges, religious organizations have multiple constitutional and statutory protections for their religious identity and religious exercise.

What Is to Be Done?

Whatever the season, and certainly now, wisdom dictates that faith-based organizations be public about how their policies, identity, and practices are rooted in specific religious and moral convictions. American law and principles provide strong protections for religious organizations—but the organizations have to be publicly religious and consistent in how they put their convictions into practice.

Faith-based organizations that believe a particular social service ought to include religious activities and religious teaching should now, as before, investigate whether the rules that accompany government funds will accommodate such inclusive services or instead require a separation. We should recall that separation does not mean that beneficiaries must be treated as though religion was irrelevant, but it does require care in how a service is designed and carried out, and that beneficiaries are only invited, not pressured, into participating in the separated religious activities.

American society is becoming not only more diverse but also more secular and even more anti-religious. But there are many protections for religious exercise, including protections for the operations and identity of faith-based organizations. And even now, the church-state rules that apply to the federal funding of social services are, if imperfect, in many ways supportive of faith-based social services. Serving in the public square, serving with the support of government funds, remains a viable way for faith-based organizations to love their neighbors.

Stanley Carlson-Thies is the founder and senior director of the Institutional Religious Freedom Alliance, a division of the Center for Public Justice. He is an expert on the federal Faith-based Initiative and served in the inaugural White House Office of Faith-based and Community Initiatives in the administration of President George W. Bush.

May a faithbased provider that has religion-based conservative standards concerning sexuality decline to hire, for instance, an applicant in a same-sex marriage?

Religious liberty in the courts and culture

Case in Point

Religion

Goes to the Games

The more than 10,000 Olympic athletes competing in the Paris Olympic Games this summer will have access to more than just sports doctors, physiotherapists, and masseuses. They’ll also have the option to receive spiritual care. The Paris Games organizing committee has credentialed some 120 chaplains representing Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam and Judaism. In a large tent structure in the Athlete’s Village, these faith leaders have created space for chaplains to minister to athletes’ spiritual needs—whether its anxiety before competition, bad news from home, or simply loneliness. Each major world religion has been given just over 500 square feet within the tent. Jewish and Muslim leaders chose to set up their spaces next to each other to show their commitment to peaceful relations, despite the conflict in Gaza. Buddhist and Hindu chaplains, who expect fewer athletes of those religions, donated half their spaces to the Christians to help accommodate some 100 chaplains who will serve Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant athletes.

But not all religious issues at the Olympics are being resolved harmoniously. The French sports minister has banned female French athletes from wearing sports hijabs, which are specially designed athletic wear that complies with conservative Islamic dress requirements. The minister cites France’s strict separation of church and state, known as laicite, for the ban. France is home to the largest Muslim population in Western Europe and for the past two decades has banned the wearing of headscarves by public employees, such as school teachers. Bans on the wearing of hijab in public enjoy widespread popular support in France, but have long attracted criticism from religious liberty advocates. Several international organizations, including Amnesty International, have protested the hijab ban to the International Olympic Committee, saying it discriminates against female Muslim competitors on the French Olympic team.

In Brief

In a landmark case, the Supreme Court of South Korea has ruled in favor of a Sabbath keeper’s request for religious accommodation. The Court said that it was unlawful for Chonnam National University law school to refuse to reschedule an interview for a Seventh-day Adventist student. According to a Supreme Court spokesperson, this is the first decision by either the Constitutional Court or the Supreme Court of South Korea “to explicitly acknowledge a Seventh-day Adventist’s request for a change in the test schedule. It clarifies the obligations of administrative authorities to prevent Seventh-day Adventists and other minorities from facing undue discrimination due to their religious beliefs.” The decision comes after decades of hardship for students and professionals in South Korea who keep Saturday as Sabbath.

The United Nations General Assembly has approved the first-ever multilateral resolution on artificial intelligence. The resolution says the nations of the world must work

together to make sure this new, quickly evolving technology is “safe, secure, and trustworthy” and upholds human rights. The resolution was co-sponsored by 123 countries, including China, which is accused of using AI facial recognition technology as a tool of oppression against Uyghur Muslims.

Schools in the 25 largest school districts in Texas have rejected a controversial state-funded chaplaincy program, created by state lawmakers last year. Many feared that the initiative would prove divisive in Texas’ religiously diverse public schools. School boards in these 25 districts, however, voted not to install state-funded chaplains as school counselors. It appears that politics was not the deciding factor; these districts represent both politically conservative and liberal areas.

Hate acts in America rose in the wake of Hamas’ October 7 attack on Israel. The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) said it recorded 2,031 antisemitic incidents nationwide between October 7 and December 7 last year. This is a more than four-fold increase over the same

period in 2022, when only 465 similar incidents were recorded. The ADL says this represents the highest number of any two-month period since it began tracking antisemitic incidents in 1979.

The Council on American-Islamic Relations says it also tracked complaints of bias incidents or requests for help in the two months following October 7, 2023. It received some 2,171 complaints, amid what it called ”an ongoing wave of anti-Muslim and anti-Palestinian hate.”

Religion’s role in America’s public life is shrinking—at least that’s the belief of 80 percent of adults in the United States, according to a recent survey conducted by the Pew Research Center. The same survey also found that about half of U.S. adults say it’s “very” or “somewhat” important to them to have a president who has strong religious beliefs, even if those beliefs are different from their own.

At a time when fierce partisanship defines American politics, a gala dinner at the Russell senate Office Building on Capitol Hill showcased religious liberty as an American value that transcends political and religious differences.

Representatives from Congress, civil society organizations, and faith groups came together May 3 for the 18th annual Religious Liberty Dinner, co-sponsored by Liberty magazine and the Seventh-day Adventist Church in North America.

Many of those present had been part of an effort to ensure that strong religious liberty protections were included in the Respect for Marriage Act (RMA), legislation passed by the U.S. Congress in 2022, which codified a 2015 Supreme Court decision extending legal recognition of same-sex marriages. Thanks to advocacy efforts by religious and civil groups, however, the RMA also provided robust religious freedom protections for those holding a traditional view of marriage.

Melissa Reid, who represents the Seventhday Adventist Church in North America on Capitol Hill, introduced both the keynote speaker, Senator Collins, and Shirely V. Hoogstra, President of the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities, who received the Religious Freedom Advocacy Award. She thanked Senator Collins for her commitment to ensuring that legislation advancing LGBTQ civil protections also included necessary religious liberty protections.

Reid introduced Hoogstra by noting her “visionary leadership, her record of success, and her passion for her member schools and their students. Shirley is a vigilant protector of the rights and dignity of all humanity. Her professional achievements are only eclipsed by the respect and compassion she extends to others.”

Celebrating Common Ground

“I cannot address an event hosted by Seventh-day Adventists without noting that the co-founder of your Church, Ellen G. White, was born and raised—and educated and shaped to become a great teacher and leader—in my state of Maine. I was amazed to see that the Ellen G. White Center in nearby Silver Spring now offers on its website her extensive writings in 155 languages. What a remarkable woman! Among her writings is a statement that I believe describes the spirit that brings us together tonight: “Every act, every deed of justice and mercy and benevolence, makes heavenly music in Heaven.”

Those deeds often come at a price. At a time of deep divisions, when extremists on the left and the right demand 100 percent compliance with 100 percent of their views 100 percent of the time, it takes courage to stand up to criticism.”

Shirely V. Hoogstra, President of the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities, received the 2024 Religious Freedom Advocacy Award.

“My life’s Bible verse is I Peter 3:15 which says, and I paraphrase, ‘Always be prepared to give the reason for the Hope that you have in Christ Jesus and do so with gentleness and respect.’ This guidance offers both personal and civic implications. … Think back to 2015. The Supreme Court expanded the definition of marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges. Suddenly, the landscape for religious liberty in our society shifted. Biblical marriage was brought into conflict with a new civil category of legalized same-sex marriage. Nine years ago, you may remember great uncertainty about how groups that held to the traditional understanding of marriage would be able to operate in the midst of new federal law. Would accreditation and federal funding be taken away? Or would we find a way to coexist? And perhaps be a blessing to each other? After serious prayer, study and consideration, the CCCU Board of Directors decided that our approach would be to sit ‘at the table’ with the groups that could be influential in finding a way forward for orthodoxy along with understanding the new civil paradigm without compromise. Our goal was to persuade decision makers that any bill moving LGBTQ civil rights forward would always include the protection of religious belief and practice at odds with those expanding civil rights. To the surprise of many, we succeeded with this paradigm shift. The passage of The Respect for Marriage Act, led so courageously by Senator Collins, here tonight, is an example of the national commitment to religious liberty.”

Thomas C. Berg, the James L. Oberstar Professor of Law and Public Policy at the University of St. Thomas School of Law, received the Religious Liberty Scholar Award for 2024. His recent book, Religious Liberty in a Polarized Age (Eerdmans, 2023) was cited by Christianity Today as one of those most likely to influence evangelical thought in 2024. In introducing Berg, Bettina Krause, editor of Liberty magazine, said his “scholarship is providing those who work in religious liberty advocacy with concrete, actionable approaches to resolving deep conflicts; conflicts that often seem insoluble.”

In his acceptance speech, Berg quoted James Madison, who said that “strong religious liberty for all—‘equal and compleat’ liberty— was the ‘true remedy’ for religious conflict. … Today again, strong religious liberty for all can serve that purpose….In my book I try to explain why religious liberty is so important to believers, why Christians and Muslims have an interest in protecting each other’s freedom, how freedom for religious organizations serves the common good, and how with careful thinking, one can draw lines that protect religious freedom strongly while still accounting for the interests of other persons and of society.”

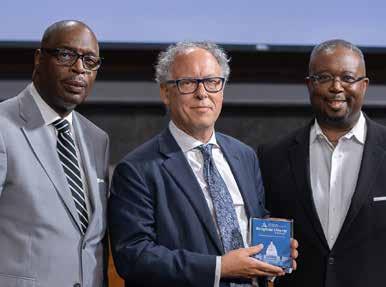

Alan Reinach, (left) president of the Church State Council, and Todd McFarland, (right) deputy general counsel for the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, received the 2024 Religious Liberty Jurist Award.

Bettina Krause, editor of Liberty magazine, lauded their tireless work, over many decades, to address a fundamental wrong in American civil rights law—a legal standard under Title VII, which has weakened protection for the religious practices of Jews, Muslims, Seventh-day Adventists, Sikhs, and many other people of faith, in America’s workplaces.

“It’s thanks in no small part to the groundwork laid by Alan and Todd—as they’ve litigated these cases through the years—that this legal standard was finally, last year, brought before the Supreme Court for review in the case of Groff v. DeJoy.

This case involved a U.S. postal worker, Mr. Groff, who had been given an untenable choice—it was a choice between keeping his Sabbath or keeping his job. Alan and the Church State Council represented Mr. Groff from the beginning, and—at the appellate levels—they were joined by First Liberty Institute, the Independence Law Center, and law firm of Baker Botts. Todd, with his wealth of experience in litigating Title VII cases, also played a key role in shaping the legal arguments of the case.

The decision of the Court in Groff has fundamentally altered the legal landscape in this area. It has brought end to a quest that’s almost five decades long—to hold America’s employers to a higher standard of accountability in how they respond to requests for religious accommodation.”

God, Gold, and the Indigenous “Other”

A church-state tragedy in three acts

By Lynn Neumann McDowell

The day after Pope Francis II made his historic July 25, 2022, apology to survivors of the residential schools for Indigenous children run by the Roman Catholic Church in Canada , the New York Times ran a front-page story and photo of the pontiff amid white crosses. They were grave markers in the Ermineskin Cree Nation cemetery in Maskwacis, Alberta, not far from where Canada’s largest Catholic residential school had loomed—a school from which many children never made it home.

Chief Randy Ermineskin, himself a survivor of abuse in the Ermineskin Residential School, sat on the pope’s left with level gaze as media captured the spiritual leader and head of state delivering his apology. As the pontiff exited the platform, a voice rang out from the mostly Indigenous crowd: “We need the Doctrine of Discovery repealed!”

It was a political and a religious statement, and yes, even a legal one. Regardless of how one answers the question “Was the United States of America founded as a Christian nation?” the inescapable conclusion regarding the law as it pertained to Indigenous peoples living in North America—and which continues to impact them—is based in theology.

It doesn’t much matter which brand of empireenabling theology or which side of the Canada-U.S. border you look at.1 The devastating results of legislators using theological views to buttress laws concerning Indigenous peoples is a centuries-long tragedy of intertwined church and state interests.

Act 1

The Doctrine of Discovery as Legal Bedrock

The 1493 bull “Inter Caetera” of Pope Alexander VI, issued in direct response to Columbus’s voyage of discovery, reflects the basis of pre-World War I colonial thought going back to the Roman emperor Constantine and his vision of the cross. The bull was a pragmatic response to a political-economic squabble between the Portuguese and Spanish, who vied for new trade routes and valuable commodities. Alexander’s bull built on a series of earlier papal bulls that were part of church canon law connected to the Crusades authorizing the Christian kings of Portugal and Spain to conquer Muslim and non-Christian pagans, and “reduce their persons to perpetual servitude and convert their land to your use and the use of your successors” (fifth bull of Pope Nicholas V, 1452). Alexander’s 1493 bull gave both petitioners the right to terra nullius (empty lands) territories they might discover within separate geographical points defined in the bull. Although populated, they were defined as “empty lands” because they were not subject to a Christian overlord and the inhabitants were not Christian. The bull further granted the full and exclusive right to convert the discovered inhabitants to the “true faith.”

The papacy, widely accepted as heir of Constantine’s fabled “Holy” Roman Empire, upheld in these bulls the Constantinian tradition of ruthless conquest and proselytizing used by the emperor in his pursuit of a Roman Christian empire, combining political and religious ends. Part of the Requerimiento, a document Spaniards were required to read to native leaders prior to taking control of their lands (seldom read in the hearing of the inhabitants; sometimes read on board ship before seeing any inhabitant—and always in Spanish), reads:

“I beg and require of you . . . to recognize the church as lady and superior of the universe and to acknowledge the Supreme Pontiff, called Pope . . . if you do not do it . . . then with the help of God . . . I will take you personally and your wives and children, and make slaves of you, and as such sell you off . . . and I will take away your property and cause you all the evil and harm I can.”

Though the sovereignty of the Spanish over the Western Hemisphere and the bru-

tality of its conquest was protested within the church by fifteenth-century social reformer Bartolomé de Las Casas, a priest and contemporary of Luther, the motivating mixture of “God, Gold, and Glory,” as identified by de Las Casas, proved too attractive to overcome. The triune motivators of religion, profit, and empire power was confirmed by Cortes in his famous 1521 declaration that ends with “Let us go forth, serving God, honoring our nation, giving growth to our king, and let us become rich ourselves; for the Mexican enterprise is for all these purposes.”

Protestants decried Spain’s abuses as “popery,” but justified their own treatment of Indigenous peoples by essentially the same line of reason. The English, both Puritan and Pilgrim, had a slightly different take on the recognition of the pope but essentially came to the same conclusion—that colonialism (specifically British Protestant colonialism) was mandated by God. In 1620 King James I (of King James Version of the Bible fame) lost no time claiming the death of thousands of Native Americans from smallpox as evidence of God’s favor, and urging the colonists, with this evidence of God’s “great Goodness and Bountie towards Us,” to take all the land.

A Pragmatic Shift with Lasting Consequences

In a constitution-based America, viewing non-Christian inhabitants as less human (and therefore having lesser rights) evolved more along race lines, with less reference to religious practice. Race, which now included Black slaves, proved a more practical way to determine groups of people who were “Other” or “Not Settler-Colonists.” By the time Indigenous peoples started taking their cases to court—a true rarity for many reasons—the diminished rights of Othered peoples was so ingrained that the U.S. Supreme Court confirmed in the 1823 case of Johnson v. McIntosh (where the term “Doctrine of Discovery” is first used in jurisprudence) that once European settlers came ashore, the title in the land was vested in or moved to the British crown, “so the doctrine was a valid part of U.S. law,” as stated by the chief justice. As recently as 2005 the Supreme Court acknowledged the continued relevance of this doctrine to U.S. property law in an Indian land dispute case. Johnson v. McIntosh was adopted by Canada in the 1888 St. Catherines Milling case and thus became an integral part of Canadian law as well.

Act 2

How the West Was Won

WithEuropean settler title clearly established regarding land and the implied inhumanity and lesser rights of Indigenous peoples widely accepted, the stage was set for atrocities in both the United States and Canada. Canada, observing the Trail of Tears and the high cost of the American Indian Wars (not officially ended by the U.S. government until 1890), opted for the alternative of forced starvation. The destruction of the bison was the first step, followed by a brisk cross-border business in emaciated U.S. cattle. The animals were driven north to provide rations in starvation quantities to be distributed (or not) by Indian agents on reserves—the area to which treaties now restricted Indigenous peoples on the Canadian plains. The God, Gold, and Glory formula was still intact: U.S. cattlemen and Canadian entrepreneurs had a new market, missionaries flocked to the new territories, and Sir John A. MacDonald, Canada’s first prime minister (aka “Father of Confederation”), was effectively clearing the plains in cooperation with them for the glory of a Christian empire.2

Religion and the Management of the “Other”

As an othered and subjugated group, Indigenous peoples struggled to retain individual and group identity. Exhibiting dominance by the creation of levels of rights that were conferred in legislation rather than assumed as inalienable rights conferred by God (as settler rights were) was a means of breaking Indigenous spirit on both sides of the border, making “the Indian

Problem” easier to manage. Indigenous lives, associations, and livelihood options became ever more prescribed. Separating Indigenous people from their spiritual beliefs was key if these Others were to fit into the Manifest Destiny that flowed from the Doctrine of Discovery and propelled westward expansion.