BIRDCONSERVATION

The Magazine of American Bird Conservancy WINTER

The Magazine of American Bird Conservancy WINTER

2022-23

ABC is dedicated to conserving wild birds and their habitats throughout the Americas. With an emphasis on achieving results and working in partnership, we take on the greatest threats facing birds today, innovating and building on rapid advancements in science to halt extinctions, protect habitats, eliminate threats, and build capacity for bird conservation.

abcbirds.org

A copy of the current financial statement and registration filed by the organization may be obtained by contacting: ABC, P.O. Box 249, The Plains, VA 20198. 540 253-5780, or by contacting the following state agencies:

Florida: Division of Consumer Services, toll-free number within the state: 800-435-7352.

Maryland: For the cost of copies and postage: Office of the Secretary of State, Statehouse, Annapolis, MD 21401.

New Jersey: Attorney General, State of New Jersey: 201-504-6259.

New York: Office of the Attorney General, Department of Law, Charities Bureau, 120 Broadway, New York, NY 10271.

Pennsylvania: Department of State, toll-free number within the state: 800-732-0999.

Virginia: State Division of Consumer Affairs, Dept. of Agriculture and Consumer Services, P.O. Box 1163, Richmond, VA 23209.

West Virginia: Secretary of State, State Capitol, Charleston, WV 25305.

Registration does not imply endorsement, approval, or recommendation by any state.

Bird Conservation is the member magazine of ABC and is published three times yearly

Senior Editor: Howard Youth

VP of Communications: Clare Nielsen

Graphic Design: Gemma Radko

Contributors: Andrés Anchondo, Erin Chen, Marci Eggers, Duane Fogard, Rachel Fritts, Lewis Grove, Bennett Hennessey, Steve Holmer, Brad Keitt, Hardy Kern, Daniel J. Lebbin, Sea McKeon, Jack Morrison Michael J. Parr, Steven P. Riley, Aimee Michelle Roberson, Marcelo Tognelli, Amy Upgren, George E. Wallace, David A. Wiedenfeld, EJ Williams, Kelly Wood

For more information contact: American Bird Conservancy P.O. Box 249 4249 Loudoun Avenue The Plains, VA 20198 540-253-5780 • info@abcbirds.org

ABC is proud to be a BirdLife Partner

us on

Find

social!

COVER: Called Oskanankubi in the Chickasaw language, the Peregrine Falcon appears as a significant symbol throughout the ancient Mississippian Mound Builder cultures. This raptor remains important to Indigenous Nations whose homelands are in the lower Mississippi River Valley. Photo by Glenn Bartley.

LEFT: The male Gray-bellied Comet has understated beauty, including a gold sheen to its elongated tail feathers. Photo by Manuel Roncal-Rabanal. Read more about this species on p. 25.

3 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 20 22-23

FEATURES Lessons from Indigenous Lifeways and Our Feathered Relatives p. 14 Birds of Different Feathers Life in a Mixed-Species Flock

21 Sowing Seeds for Bird Recovery How New Planting Fuels Conservation

24 DEPARTMENTS BIRD’S EYE VIEW Farm Bill Healing p. 4 ON THE WIRE p. 6 BIRDS IN BRIEF p. 12 ABC BIRDING Buenaventura Reserve, Ecuador p. 34 BIRD HERO Nature Study Blooms in the City p. 38 Winter 2022-23

p.

p.

Tending seedlings at the Pauxi Pauxi Reserve, TABLE OF CONTENTS

Colombia. Photo by ProAves Colombia 34

21 24

owendeutsch.com 14 Quail ( Kofi

by

Golden-crowned Kinglet by Frode Jacobsen Long-wattled Umbrellabird by Owen Deutsch,

Nukshopa )

Lokosh (Joshua D. Hinson)

Patching the Tattered Fabric, One Farm Bill at a Time

by Steven P. Riley

I remember being in the outdoors often with my father when I was a boy. My Dad, Zene, was an avid hunter, angler, and unintentional naturalist, and we were in the fields or at the lake nearly daily. Zene was an Iowa farm boy who grew up to be a career military man.

Nature was his respite and great love.

Dad was a wild storyteller and a trickster, always keeping me on my toes, ready to detect malarkey. So, one cloudy pre-dawn when he proclaimed that a distant flock a half-mile away included two drakes and a hen Mallard, I thought it was a joke. To my bewilderment, when the dots turned into ducks that finally swung by our decoys, there were in fact two drakes and a hen Mallard. I was hooked. I wanted to know how Dad knew that, and he began teaching me. With Dad’s help and my curiosity, I may now love the wildlife around me as much as he did. I’m especially fond of the wide-open spaces of grasslands and the birds I find there.

We all come to appreciate nature in our own ways. Once we embrace its beauty and significance, many of us realize that modern life and all its machinations have created a wall between humans and the wild, and that many of our activities have taken a toll on nature.

After we connect with the outdoors, as I did through my father and my ramblings, it’s easy to see Earth’s thin skin as a woven fabric. Looking closer, we can see grasslands and other imperiled ecosystems as frayed patches and declining species as weakened strands. It becomes clear that these things need our care.

You have probably heard that we have lost more than a quarter of the overall population of U.S. and Canadian birds since 1970 — nearly 3 billion birds! The biggest loser: grassland birds, a group with a population that has fallen by 40 percent.

Much of my work focuses on strengthening conservation for these declining grassland birds through the U.S. Farm Bill. It might surprise you to learn that this federal legislation, passed every five years or so, is the largest source of conservation funding in the U.S. We can do a lot for birds by making the Bill stronger for bird conservation, with provisions that encourage bird-friendly conservation while discouraging harmful practices.

I consider the environmentally friendly provisions that may end up in the upcoming Farm Bill as patches that strengthen the biosphere’s dwindling strands. A lot of those strands occur on farm and ranch land, which together make up about half of the land area of the contiguous U.S. states. We spend billions of dollars through the Bill each year to help farmers and ranchers conserve their land. These conservation actions can help by providing improved habitat conditions that help birds thrive, while making agriculture more sustainable. Along with what the

4 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 2022-23 BIRD’S EYE VIEW

It’s easy to see Earth’s thin skin as a woven fabric. Looking closer, we can see grasslands and other imperiled ecosystems as frayed patches and declining species as weakened strands. It becomes clear that these things need our care.

Farm Bill itself holds in store, the recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act has already provided about $20 billion for Farm Bill conservation programs.

Birds have long benefited from Farm Bill funding. Per haps you have heard of the Sage Grouse Initiative that has been championed by USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service. Or maybe you’ve heard of the State Acres for Wildlife (SAFE) provision within the Farm Service Agency’s Conservation Reserve Program. The Farm Bill does a lot for birds already, and with some extra effort, it can do much more.

That’s where ABC comes in. For many years, our Policy team has helped to shape the Farm Bill and how it is administered. For the upcoming Bill, which will

hopefully pass in 2023, ABC is promoting a “Bird Sav er” package of enhanced practices and new policy ideas that boosts bird conservation while helping farmers, ranchers, and rural communities thrive. One example is the Grassland Restoration Incentives Program (GRIP) that was designed and first implemented by ABC and its partners at the Oaks and Prairies Joint Venture in Oklahoma and Texas. GRIP is a partnership-driven pro gram that provides voluntary incentives to landowners to help them restore and manage grasslands for birds and their own livelihoods. Read more at: opjv.org/grip.

If you want to help, please send a letter to your senators and representative supporting the inclusion of our Bird Saver provisions in the next Farm Bill. Here’s wishing for a new year that includes a big boost for grassland birds! Read more about ABC’s ongoing efforts at: abcbirds.org/program/farm-bill/.

5 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 20 22-23

Steven P. Riley is ABC’s Director of Farm Bill Programs.

Bobolink by Ryan Mense, Shutterstock; fabric background by StudioIlanP, Shutterstock.

Key Bird Reserve Expansions, Powered by Partnership

Three recent land purchases highlight ABC and partners’ work to save habitat for some of the Western Hemisphere’s most endangered birds. By targeting parcels that connect and buffer reserve core areas, these expansions help ensure a more stable future for these important conservation areas and the birds they protect.

(LEFT:) Celebrating the expansion of the Dominican Republic's Bosque de las Nubes Reserve, which provides more protected habitat for the Bicknell's Thrush and other migratory birds. From left: César Ros, SOH Conservación board member; Marci Eggers, ABC; Jorge Brocca, SOH Conservación Executive Director; Daniel J. Lebbin, ABC.

Dominican Republic:

Brazil:

Starting in 2004, SAVE Brasil began protecting habitat in the Serra do Urubu, in the only remaining midelevation Atlantic Forest in the Brazilian state of Pernambuco. Since 2019, ABC has supported SAVE Brasil's efforts to expand the reserve and create tourism infrastructure there. The latest addition is 185 acres, which brings the total protected area to 1,060 acres.

The reserve protects 14 globally threatened bird species and 250 bird species overall, including the Sevencolored Tanager, White-collared Kite, and Jandaya Parakeet.

This expansion was made possible by the Robert W. Wilson Charitable Trust, March Conservation Fund, David and Patricia Davidson, David Harrison, Kathleen Burger and Glen Gerada, and The Reissing Family.

Ecuador:

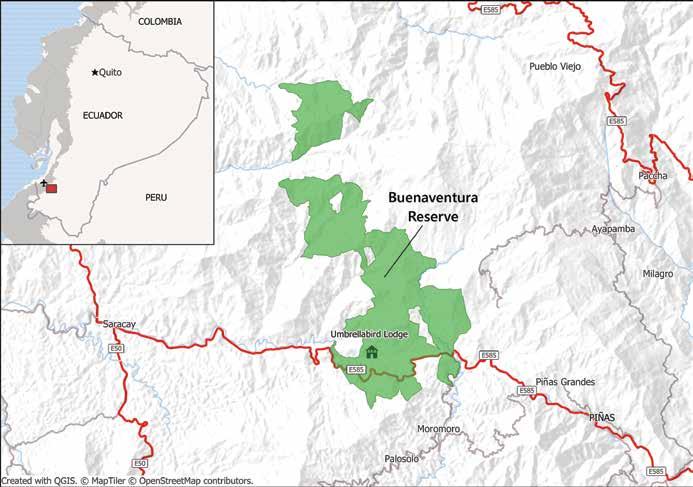

Located in Ecuador’s largely de forested southwestern corner, the Buenaventura Reserve is the only protected area for the Endangered El Oro Parakeet and hosts many other range-restricted species. This fall, it was expanded by 575 acres thanks to the Conserva Aves initiative — an ambitious effort supported by the Bezos Earth Fund and other donors to secure bird habitat from Mexico to Chile.

ABC worked with partner Fundación de Conservación Jocotoco (Jocotoco) on this latest expansion of the Buenaventura Reserve, which now spans a total of 9,947 acres. (Read more about this reserve on p. 34.)

SOH Conservación (SOH), with ABC support, recently purchased 432 acres to expand the SOH-managed Bosque de las Nubes Reserve, adjacent to the Sierra de Bahoruco National Park. This addition provides more protected habitat for the Bicknell’s Thrush and other Neotropical migratory birds, as well as endemic species including the Hispaniolan Woodpecker and Palmchat. This acquisition also helps hold the line against illegal incursions into the nearby national park. ABC thanks Mark Greenfield and the Greenfield-Hartline Habitat Conservation Fund for their support.

BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 2022-23 6

ON the WIRE

The Jandaya Parakeet is one of many rangerestricted bird species found in the Serra do Urubu, Brazil. Photo by Ciro Albano.

Tracking a Grassland Icon

The Eastern Meadowlark’s clear “spring-of-the-year” song once rang across farms and fields throughout the East and much of the Midwest. Today, in many of its former haunts, this lemon-bellied bellwether is but a memory. In fact, over the last 50 years, the species’ population has declined by an astounding 75 percent in the U.S. and Canada.

“The Eastern Meadowlark’s decline is telling us about the loss of grass lands on a massive scale,” says Jim Giocomo, ABC’s Central Regional Director. This iconic bird is just one species in a very troubled group: A 2019 Science paper, co-authored by ABC, reported that more than 720 million U.S. and Canadian grassland

birds were lost since 1970. Largescale, intensive agriculture, including overuse of toxic pesticides, has fueled these declines.

Although Eastern Meadowlarks have been widely studied on their nesting grounds, surprisingly little is known about their migratory patterns and fall and winter habitat needs. So, this past summer, staff from ABC, the Central Hardwoods Joint Ven ture, and several other organiza tions placed tiny solar-powered GPS transmitters on six meadowlarks in Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Tracked birds are being monitored to reveal their fall migra tion pathways and where they spend the winter months.

Most of the Eastern Meadowlark population occurs on private lands. One benefit of this study will be to gain insight into how ABC can work with interested private landowners to manage their properties with meadowlarks in mind, both on nesting and wintering grounds.

“Using the latest technology and building a large partnership across North America, we are learning more about what our grassland birds need to thrive,” Giocomo says. “This insight will help us reverse the steep population declines, includ ing through collaborative habitat management programs across the seasons.”

Secrets revealed by tracking Eastern Meadowlarks during fall and winter will aid efforts to conserve this declining species. Photo by Jarett Thurman, Shutterstock.

Proposed FWS Eagle Rule Weak on Wind, Positive on Powerlines

In September, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) announced a proposed rule aimed at improv ing the permitting process for inci dental take — harm to eagles that results from but is not the purpose of an activity. Unfortunately, this move does not go far enough to protect Bald and Golden Eagles at a time when new energy infrastructure and its potential threats to wildlife are rapidly expanding.

“We at ABC believe that renewable energy can and must be expanded, but with adequate safeguards for birds and other wildlife, to limit unintend ed consequences,” says Lewis Grove, the organization’s Director of Wind and Energy.

There are positives to the proposed rule, including new protections from electrocution at powerlines, a lead ing cause of eagle deaths. The general permit proposed for powerlines could greatly reduce eagle mortality by re quiring mitigation measures for pow erlines installed across eagle habitat and by raising funds to compensate through creation of eagle habitat in other locations. This change is especially timely because many new transmission lines will be installed as renewable energy resources continue to be developed.

“We applaud new protections for eagles from powerline electrocution,” Grove says. “However, the rule fails to provide needed safeguards for eagles

against threats posed by increased wind energy development.” For example, in most cases, compliance monitoring by a third party will not be required.

“We also remain concerned about the lack of an overarching mitigation strategy to ensure balanced develop ment,” says Grove.

According to recent population esti mates, Golden Eagle populations are likely declining in North America. The Bald Eagle, which has marched back from the brink of extinction, still needs strong protection. Both species stand to be especially im pacted by poorly sited wind energy development.

8 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 2022-23 ON the WIRE

An immature Golden Eagle cruises by towering turbines. Photo by Taylor Berge, Shutterstock.

Dangerous Regulatory Loophole Remains for Pesticide-Coated Seeds

In September, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) denied a petition request from ABC and other parties seeking to change a dangerous regulatory loophole for pesticide-coated seeds. Instead of regulating coated seeds as the agency does other pesticide uses, the EPA says it will review labeling language and requirements, and conduct a general review of seed treatment use. The EPA also announced that it “may explore the option” of issuing a rule to ensure coated seeds are used properly — a process that could take years to have any meaningful impact.

This decision means that pesticides applied as a seed coating will continue to be used without being tracked, quantified, or regulated like other pesticides — despite scientific evidence that seeds coated with particularly toxic insecticides called neonicotinoids (neonics) are known to kill birds and other wildlife, often with little benefit to crops.

Pesticide-coated seeds are the number-one use of neonics. When ingested, a single neonic-coated seed can kill a songbird. But the danger to birds doesn’t stop there: With neonic-coated seeds, just 2 to 20 percent of the chemical is taken up by the plant as it grows — the rest leaches into soil and groundwater, where it kills invertebrates that birds rely on for food, and that people need for crop pollination.

Coated seeds remain the most poorly regulated pesticide products, due to the “Treated Article Exemption”

introduced to the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act in 1988. The amendment makes socalled “pesticide-treated articles” exempt from registration, labeling, and tracking. Because of this loop hole, farmers might not even know when they are buying treated seeds.

In 2017, ABC teamed up with other groups representing pollinator health and food safety and petitioned the EPA to track and regulate coated seeds like other crop pesticides. After the EPA failed to respond, members of the petitioning group filed a formal complaint in December 2021, which resulted in the EPA announcement in September.

Actions the EPA suggested instead include putting clarifying language on seed bag tag labels and reviewing

possible misuse of coated seeds. While these steps might improve understanding of coated seed usage, the agency’s decision effectively endorses the continued use of neonic-coated seeds with minimal oversight or regulation.

“We are extremely disappointed by this news,” says Hardy Kern, Director of ABC’s Pesticides and Birds Campaign. “Without a change to the Treated Article Exemption, it is impossible to accurately enforce the Endangered Species Act and other wildlife-saving laws. ABC will continue to fight for change in the way these chemicals are regulated.”

ABC is grateful to the Raines Family Fund for its generous support of our Birds and Pesticides Campaign.

9 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 20 22-23

Seeds coated with neonicotinoid pesticides pose multiple threats to Yellow-headed Blackbirds and many other species. Photo by Jennifer Davis.

Because the World Needs Birds …

and

Birds Need You.

Greater Sage-Grouse by Noppadol Paothong, www.npnaturephotography.com

Birds make the places we love and explore special through their songs, beauty, and the ways that they connect us to the natural world.

Birds also play key roles in their habitats and contribute to human health, improve agricultural production, help boost local economies through ecotourism revenue, and serve as indicators of environmental well-being.

Birds do all this, and so much more for us, but many of them are in trouble.

The U.S. and Canada have lost nearly 3 billion birds, which translates to more than one in four, since 1970. Bird declines, however, aren’t confined to one continent: Populations are down across much of the globe.

We all want to live in a world filled with birds, and with your support, there is hope.

This giving season, please help us save wild birds and their habitats. Thanks to a dedicated group of supporters, we have a 1:1 Match with a goal of raising $1 million by December 31.

Will you make an impact for these incredible creatures that do so much for us, with your most generous gift for birds today? Your support will help us reverse population declines across the Americas and combat the risks birds face daily.

When you support American Bird Conservancy, your gift will be used immediately to:

• Bring Endangered birds back from the brink of extinction, such as the Gray-bellied Comet — a hummingbird with an estimated population of fewer than 1,000 adult birds.

• Conserve breeding, wintering, and migratory stop over habitat for birds of concern, such as the Eastern Whip-poor-will, Painted Bunting, and Chestnutcollared Longspur.

• Reduce threats to all birds by removing trash and plastics from Texas coastlines that impact migrating and beach-nesting birds such as the Snowy Plover.

• Build capacity for a growing bird conservation movement through ABC’s Bird City Network programs, which help communities make their natural areas, parks, main streets, and backyards better for birds and for people.

We are determined to save wild birds, but we cannot do it without YOU by our side.

Please donate today to our 1:1 Match and help us raise $1 million by December 31. Will you please give your most generous gift for birds today?

Because the World Needs

and

Need You!

the enclosed envelope or donate today at: abcbirds.org/world-needs-birds

Birds …

Birds

Return

BIRDS in BRIEF

Over Half of U.S. Bird Species Declining; 70 Especially at Risk

More than half of U.S. bird species monitored since 1970 are trending downward, according to the 2022 State of the Birds Report, which was produced by a consortium of govern ment agencies, private organizations, and bird initiatives led by NABCI (North American Bird Conservation Initiative). The report, published in October, identifies 70 species that lost half their populations over the last five decades, and that will likely lose another half in the next 50 years if their level of conservation does not change.

See: StateoftheBirds.org.

managed stronghold. The plan aims to increase grassland habitat man agement on state-managed lands; continue lek monitoring; increase permanent land protections via ac quisitions and easements; enhance private lands initiatives; and increase education and outreach to raise Wisconsinites’ awareness of this special bird.

Read the plan here: dnr.wisconsin. gov/topic/WildlifeHabitat/ prairiechicken.html

Court Upholds Bird-Friendly Building Ordinance in Wisconsin

A bird-friendly building ordinance enacted in Madison, Wisconsin, in 2020 — the first in that state — with stood a legal challenge by developers, with the Dane County Circuit Court ruling in its favor in August. The ordinance requires new construction and expansion projects to incorpo rate bird-safe strategies and materials into their work.

discussing how solutions like Madi son’s building ordinance save birds’ lives. Twenty-two bird-friendly build ing design guidelines have been ad opted by states and municipalities in the U.S. and Canada; many more are currently pending.

Read more about bird-friendly building design here: abcbirds.org/ glass-collisions/.

Louisiana’s Whooping Crane Success

The Whooping Crane once inhabited Louisiana, both as a resident breeder and wintering species, but was wiped out by 1950 due to habitat loss and unregulated hunting. Now, the big bird is back: A reintroduction effort in the southwestern part of the state began in 2011, when ten Whooping Cranes were released. Since then, numbers have grown steadily. This year, a record eight chicks fledged after hatching in the wild. Louisi ana’s flock now totals 76 cranes. This effort is run jointly by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Loui siana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, which leads on the reintro ductions and monitoring.

Wisconsin Aims for Prairie-Chicken Revival

In June, the Wisconsin Natural Resources Board approved a new ten-year plan for restoring the state’s Greater Prairie-Chicken population. Once found across Wisconsin in tall grass prairie and savanna habitats, just a few hundred prairie-chickens remain in the state, mainly in one

In response to the developers’ legal challenge, ABC, Madison Audubon Society, and Wisconsin Society for Ornithology had filed an amicus curiae, or friend of the court, brief in April, which provided background information for the judge, summa rizing the conservation crisis that window collisions pose to birds and

12 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 2022-23

Report cover reprinted with permission from NABCI

Young Whooping Crane by Scott E. Nelson, Shutterstock

Greater Prairie-Chicken by

Steve Oehlenschlager, Shutterstock

“Lost” Hummingbird Rediscovered

A rare hummingbird known only from Colombia’s Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains, the Santa Marta Sabrewing was recently resighted and photographed. This is only the second time the iridescent blue-and-green species has been doc umented since it was first collected in 1946. The Search for Lost Birds, a collaboration among Re:wild, ABC, eBird, and BirdLife International, had ranked the Santa Marta Sabrewing as one of its top ten most-wanted birds.

Rediscovering lost birds sparks a “new beginning”: For the sabrewing, next steps include getting a better understanding of this bird's distribu tion, population size, and the threats it faces, so that an action plan for its protection can be developed.

Find out more here: abcbirds.org/ program/lost-birds

Waved Albatross and Juan Fernandez

Firecrown hummingbird, as well as creating ecosystem resilience to climate change. Islands represent only about 5 percent of Earth’s land area but have endured 61 percent of extinctions since the 1500s. Today, 40 percent of the planet’s highly threatened vertebrate species occur on islands.

Read the study at: nature.com/ articles/s41598-022-14982-5

Hawai‘i Seabird Success

Woodblocks, Women, and Wildlife in Ecuador

In May, an innovative workshop took place in the Chocó rainforest in northwestern Ecuador — home to more than 500 bird species. Fundación para la Conservación de los Andes Tropicales (FCAT) held the event at its nature reserve, bringing together local women to share their experiences, and to spark interest in alternatives to habitat alteration that empower, provide income, and include women in ongoing efforts to save the Chocó. FCAT provided instruction, materials, and assistance relating to woodblock-printed art and products, including paper prints, earrings, and T-shirts.

Study Highlights Successful Eradication of Island Invasives

A study co-authored by ABC’s Oceans and Islands Director Brad Keitt and published on August 10 in Scientific Reports documents an 88-percent success rate in worldwide efforts to eliminate invasive species such as rats, goats, and cats from islands — a critical step toward saving threatened island species such as the

Partners working to establish a new seabird colony at Nihoku, Kīlauea Point National Wildlife Refuge, Kaua‘i, are making great progress. Two of Hawai‘i’s endemic seabirds — the Critically Endangered Newell’s Shearwater (‘A‘o) and the Endangered Hawaiian Petrel (‘Ua‘u) — are returning to Nihoku after having been translocated there years earlier as chicks, then maturing at sea. This year, for the first time, a Newell’s Shearwater translocated as a chick returned as an adult to Nihoku, which is protected by predator-proof fencing and enhanced through habitat restoration. Hawaiian Petrels have been returning for the past several years; this year, the first chick hatched at the site was confirmed. Learn more about this project and its partners at: nihoku.org

13 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 20 22-23

Women's Art Workshop in progress.

Photo by Margarita Baquero

Some workshop products.

Photo by Margarita Baquero

Waved Albatross by Don Mammoser, Shutterstock

Santa Marta Sabrewing by Yurgen Vega, SELVA

14 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 2022-23

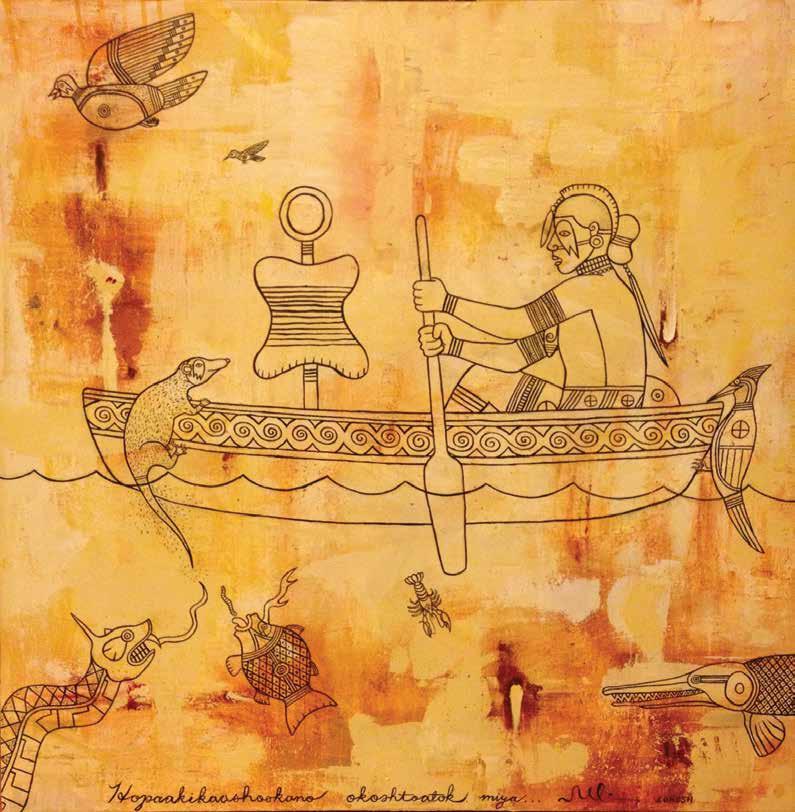

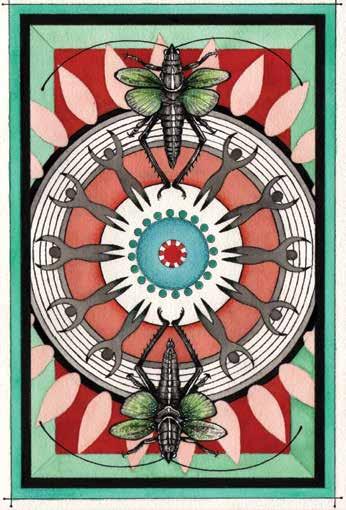

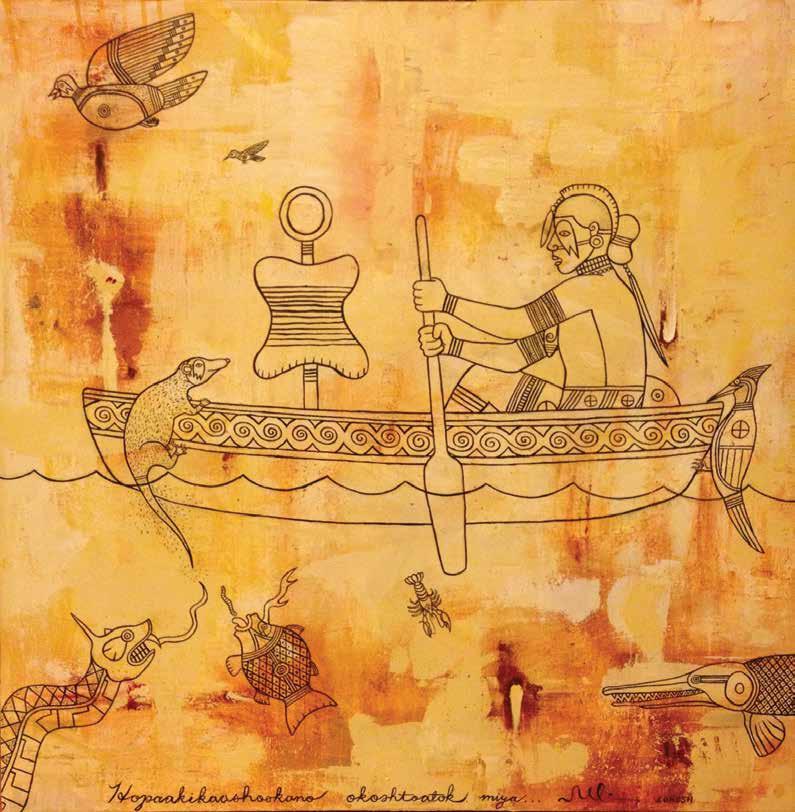

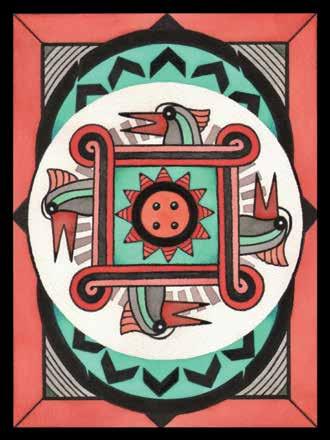

Hopaakikaashookano okoshtoatok miya (“They Say That Long Ago There Was a Flood”) by Lokosh (Joshua D. Hinson).

From the author: To me, this image reflects the sacred relationships of our Chikashsha ancestors with our otherthan-human relatives, and how we are all in this life together, respectfully interconnected.

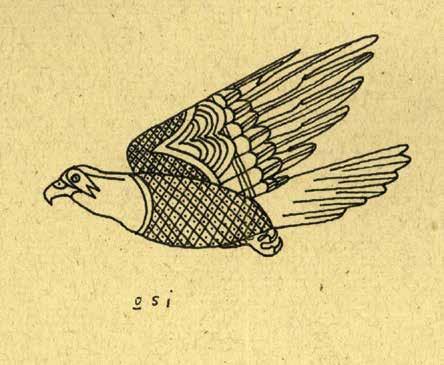

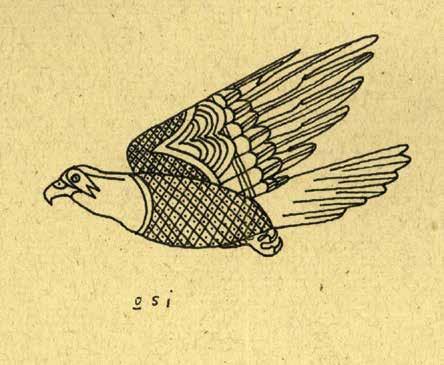

RIGHT: Osi (“Eagle”) by Lokosh (Joshua D. Hinson).

Lessons FROM Indigenous Lifeways

and Our Feathered Relatives

by Aimee Michelle Roberson ABC’s Southwest Regional Director

Halito, sv hochifoyvt Aimee. Chahta micha Chikashsha ohoyo sia. Hattak Api Homma Immi foka achonachi ka isht hachi ittimanompoli la chi.

Hello, my name is Aimee. I am a Choctaw and Chickasaw woman, and I want to talk to you about the continuance of Indigenous lifeways.

Note: Italicized words are in Chahta anumpa (Choctaw language), unless otherwise noted.

15 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 20 22-23

In this time of crises — climate change, ecocide, declining biodiversity, social inequity and injustice — many of us are wondering how we can make a difference. While my degrees in geology and conservation biology help me to understand some of these issues, my holistic perspective as an Indigenous woman gives me a deeper understanding of how they are all connected. I want to share some of this with you, believing that an understanding of Indigenous lifeways and values can help us envision and create a better future for all of us — birds and people alike.

Indigenous Lifeways

In his book “Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World,” Tyson Yunkaporta of the Apalech Clan in Australia defines “Indigenous People” as those who have a cultural memory of a sustainable way of life on the land base their ancestors occupied. He notes that each of us has Indigenous roots somewhere; some of us are just further removed from them. Indigenous lifeways and Traditional Ecological Knowledge are rooted in place and sacred relationship with the Earth, Sun, sky, water, plants, and animals, and nurtured and shared through culture, ceremony, stories, and language. The benefits of kincentric ecology (this interplay between humanity and all of the natural world) are reflected in reports from the United Nations stating that ecosystems stewarded by Indigenous People retain the highest measures of biodiversity, while a 2012 study by L.J. Gorenflo, et al., suggests that when Indigenous languages are endangered, biodiversity declines. As our elders tell us, it is from our relatives who are Indigenous to a place that we must learn how to be in right relationship with Mother Earth.

My own Indigenous roots are with the Chahta and Chikashsha people, and I am an enrolled citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. I also have ancestors from Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and England, further removed from their Celtic roots, who settled in the homelands of the Chahta and Chikashsha people in the 1700s. In “Choctaw Food,” Ian Thompson describes Misha Sipokni (the Mississippi River) flowing through the heart of our homelands, where hvcha (streams) and lusa (cypress swamps) once supported an incredible diversity of fish and freshwater mussels, and uski pvta (dense river canebrakes), oktak (tallgrass prairies), kowi (mixed forests),

BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 2022-23 16

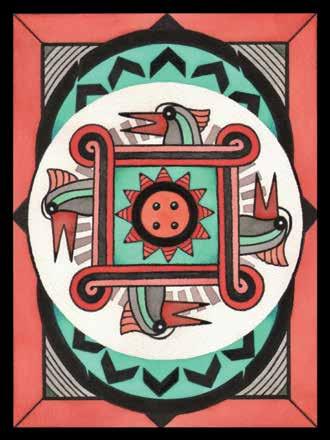

“Holy Number Four” by Karen Clarkson.

From the author: The holy number of the ancient Choctaw religion is four. This is a modern interpretation of an ancient image that was carved into shell gorgets by our Mound Builder ancestors.

From the author:

my

The first

(above)

my Chahta family was taken in Kingston, Oklahoma, in 1923. On the left is my great-great-great-grandmother, Eliza Houston, first generation to be born in Indian Territory away from our homelands. On the far right is her son and my great-great-grandfather, Arthur Greenwood “Green” Beames, and in the middle is his son and my great grandfather, Arthur William “Bois d’Arc” Beames. The babies are Bois d’Arc’s son, Benjamin Daugherty Beames, on the left, and Bois d’Arc’s sister and youngest sibling, Helen Hyahwahnah Beames, on the right.

This photo was taken in Tishomingo, Oklahoma, in 1972. On the lower left is my great-grandfather, Bois d’Arc Beames, again. On the lower right is his wife and my great-grandmother, Hazel Hyahwahnah Willis (Chikashsha). Next to her is her mother, my great-great-grandmother, Gracie Lea Williams. In the back row is my grandfather, Robert William “Bob” Beames, my grandmother, Dorace Mae Floyd, my mother, Cara Story Beames (holding me), and my father, Ivan “Rob” Roberson.

and tiak falaya (Longleaf Pine forests) were carefully stewarded by my ancestors using fire and other methods. These ecosystems supported us, the birds, and all our relatives in return.

Uprooted

Our homelands are now known as Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Tennessee, and the ongoing process of colonization has caused displacement, disconnection, and fragmentation of our people and lifeways. We — along with the land, water, and entire ecosystems — are forever changed. My ancestors were uprooted from our homelands, forced to walk “the trail of tears and death” to Indian Territory, now known as Oklahoma, after President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act in 1830. And birds like Kiliki (Carolina Parakeet) and Tikti (Ivory-billed Woodpecker) have disappeared.

In 1827, my seventh great-uncle and Chikashsha Chief Levi Colbert admonished the U.S. government while ex pressing his anguish over the deracination of our people:

We never had a thought of exchanging our land for any other, as we think that we would not find a country that would suit us as well as this we now occupy, it being the land of our forefathers, if we should exchange our lands for any other, fearing

the consequences may be similar to transplanting an old tree, which would wither and die away, and we’re fearful we would come to the same.

Prior to their displacement, some of my Chahta ancestors lived near a creek called Pachanusi (where pigeons sleep). It was named after the Pachi, or pigeon — in this case, the now-extinct Passenger Pigeon. Pachi was an important food source and a species once so abundant that their flocks darkened the sun for days as they migrated.

Pachanusi Creek is near the Natchez Trace, where there is a National Park Service marker and sign about my sixth great-grandmother, a Chahta woman, Aiahnichih Ohoyo, and her husband, English settler Nathaniel Folsom. They kept a trading post at Pachanusi in the late 1700s and early 1800s. I think about how they relied on Pachi and how our avian relative’s extinction after colonization is a terrible reminder of what happens when humans do not seek balance and harmony within our ecosystems.

The first Removal treaty imposed by the U.S. government was the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, in which the Chahta Alhíha (people) were coerced into ceding land east of Misha Sipokni for promises of payment and land in Indian Territory. My fourth great-grandparents, Amy Folsom and James Beames, were among the first to set out on the arduous journey during the devastating winter

17 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 20 22-23

These two photos span six generations of

family.

photo

of

blizzard of 1831, and others from our families followed in subsequent years. In “Choctaw Food,” Ian Thompson recounts newspapers from the period describing “Chahta women as they set out gently touching the trees of their beloved homeland and telling them goodbye.”

Amy and James survived the journey to Indian Territory, but many did not. Thousands of Chahta Alhíha who at tempted the journey in the summers of 1832 and 1833 died of cholera. As Jason Lewis describes in his master’s thesis, “Home in The Choctaw Diaspora: Survival and Remembrance Away From Nanih Waiya,” after Removal, “Chahta Alhíha became among the most dispersed Indig enous Peoples in the United States.” By 1903, only about 1,000 Chahta Alhíha were still living in the homeland.

I am the seventh generation living away from our home lands. My parents moved from Oklahoma to Minnesota when I was a child. With that move, my family lived again near Misha Sipokni. However, most of our extended family and our Tribes were in Oklahoma, so I had limited oppor tunities to learn our culture and language in my youth. My Mom took us to powwows, sweats, and ceremonies with her friends and colleagues from local Tribes — Dakȟótiyapi (Dakota) and Anishinaabeg (Ojibwe and Chippewa) — and I learned about our sacred obligations in the web of life.

The Four R’s of Indigeneity

Despite tremendous diversity across Indigenous lifeways, in 2004, La Donna Harris and Jacqueline Wasilewski described a concept of “Indigeneity” that had emerged from decades of collaboration with Indigenous People around the world. “The four R’s” they describe are core values that are common to many Indigenous cultures — relationship, responsibility, reciprocity, and redistribution. These values help us to be good stewards of our communities and ecosystems in sacred kinship with all our relatives — whether human, bird, or tree.

During the course of my own life, birds have been important guides and have provided me with an understanding of these values. For example, as young children, my siblings and I learned about our relationships with the world around us. Every spring, we were delighted to see mama ducks emerge from their nests and make their way to the pond next to our house with fluffy ducklings in tow. Most of them were Hakholba (Mallards), but occasionally Hilak (Wood Ducks) nested nearby. We chased after them in excitement. The mama duck would stand tall with her wings spread and squawk

at us defensively, protecting her tiny babies. We took heed, stepping away to give them space.

One year, my Dad rescued three baby ducks whose mother was hit by a car. As surrogate mamas, my brother, sister, and I gained a greater awareness of the delicate balance of the pond’s ecosystem. We noticed the remains of ducklings eaten by an owl, turtle, raccoon, or a cat. With our parents’ guidance, we took good care of the ducklings until they were fully feathered. The day we released them to the pond was bittersweet, but we knew it was right. From the ducklings, we learned about our kinship obligation to respect and value all our relations.

As a young adult, Oskanankubi (Peregrine Falcon in Chikashsha language) led me to the Rio Grande basin

18 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 2022-23

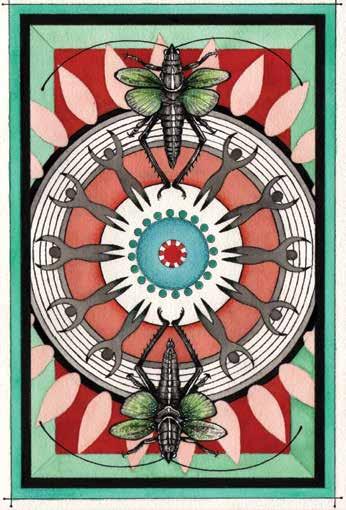

“Choctaw Creation Legend” by Karen Clarkson. From the author: This image reflects the Chahta creation story of emergence from Nanih Waiya, Holitopa Ishki (our Beloved Mother Mound). This painting has been done in the ancient two-dimensional style showing grasshoppers and people emerging from the earth during their creation. The land surrounding Nanih Waiya, in what is now known as Winston County, Mississippi, was given back to the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians by the state in 2008.

and taught me about responsibility. The Rio Grande is a place I love dearly and where I have settled for many years now. During my first job as a wildlife biologist, I canoed through Santa Elena Canyon in the homelands of the Jumanos, Chiso, Ndé Kónitsąąíí Gokíyaa (Lipan Apache), Coahuiltecan, and Mescalero Apache — a place now known as Big Bend National Park in Texas. We were observing Oskanankubi, then an Endangered species. Waking before dawn to climb from our riverside camp to the top of the tall canyon wall, we would then look across at an eyrie on the Mexican side of the river.

As I watched and listened intently, Oskanankubi wailed, taking her first flight of the day and locking eyes with me as she crossed the canyon toward us. I was mesmerized as she flew above the canyon walls tightly hugging the Rio Grande flowing between two countries and through the middle of my heart. Oskanankubi was revered by my ancient Mound Builder ancestors, representing strength, long life, family, and a long line of descendants.

I had come to the Rio Grande to observe our avian relatives because pesticides such as DDT were impacting their ability to reproduce. Birds and fish ate the insects that had been sprayed with DDT, and they were in turn eaten by birds of prey, such as Oskanankubi and Osi (Bald Eagle), which received concentrated doses, causing their eggshells to be thin and break before their chicks were ready to hatch. Observing the decline and eventual rebound of Oskanankubi after the ban on DDT taught me about our community obligation — our responsibility to care for our relatives.

Years later, our bird kin and my role as the Rio Grande Joint Venture Coordinator brought me back to our traditional homelands — and helped me to experience the essence of reciprocity. I attended a meeting of Migratory Bird Joint Venture coordinators on Chikashsha homelands — now Memphis, Tennessee.

After the meeting, I journeyed to central Mississippi — our traditional Chahta homelands, stewarded by the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. The Mississippi Chahta’s persistent resistance to Removal, resilience, and continual acts of community care allowed them to stay in our homelands. They were finally recognized by the U.S. government in 1945, more than 100 years after my ancestors

were uprooted. I visited our Mother Mound, Nanih Waiya, the central place of creation and emergence that connects all Chahta Alhíha to a homeland. Although at the time I did not know any humans there, I was greeted by many other relatives. After the experience, these words flowed from my heart:

Nanih Waiya. Holitopa Ishki (Beloved Mother). My mouth finds the words as I speak softly to the Earth. Her waters call me, speaking of life and death. My heartbeat quickens as she comes into view, cloaked in green, yellow, and red grass. Nanih Waiya, Holitopa Ishki. Coming home to a place I’ve never been. Nanih Waiya, Holitopa Ishki. Climbing slowly, I have feelings I have never felt before. I step gingerly as I reach the top. Nanih Waiya, Holitopa Ishki. Bright rays of sunshine break through the moody clouds, piercing the fog, illuminating my mind.

Scanning the landscape, my heart delights to see Fvkit (Wild Turkeys) walking across the field below me. I drop to my knees to watch them and feel the softness of her — Holitopa Ishki. My hand touches Mother Earth, a ray of light from Hvshtahli (Father Sun) catches my eyes, and my heart bursts into flames. Holitopa Ishki. The Fvkit call to each other, slowly walking across the field toward the river. Fala (American Crow) calls from the trees. Tishkila (Blue Jay), Bishkommak (Northern Cardinal), and Hattak Lhiposh (Red-shouldered Hawk) respond. Biskinik (Yellow-bellied Sapsucker), the news bird, is drumming, announcing my presence. My heart sings. I am home.

Holitopa Ishki. A part of me lives here with my ancestors. I pull some strands of hair from the back of my head and press them into the Earth so they will not forget me. I will not forget this home. Holitopa Ishki. I lay on my back, making full contact with her. With them. My body relaxes completely. Peace washes over me. I am — we are — Earth. Holitopa Ishki. Chahta sia hoke. (I am proud to be Choctaw.)

Reconnection with my homelands lit a spark in me that intensified my learning of our lifeways and language. A year later, Jason Lewis, who works for the language program in the Department of Chahta Immi (Lifeways) for the Mississippi Chahta, asked if I would help with a dictionary project. At first, I was hesitant. How could I — just beginning to understand Chahta anumpa — help in developing a dictionary? He explained that they needed someone who knew about birds to help them match up Chahta names gathered from various historical sources with common English names used today. I felt honored to share my knowledge of birds and to give something

19 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 20 22-23

Bakbakishkobo’ homma’ ishto’ (“Ivory-billed Woodpecker” in ) by Lokosh (Joshua D. Hinson).

Conserving Kofi Nukshopa (Northern Bobwhite)

Populations of Kofi Nukshopa are declining across their homelands due to habitat loss, the use of pesticides, and climate change. ABC leads several collaborative programs in which many partners work together to restore and steward their habitats, including the Tombigbee BirdScape in the Chahta homelands of the Southeast, as well as programs implemented by the Central Hardwoods, Oaks and Prairies, and Rio Grande Joint Ventures.

In many ways, these programs reflect the “four R‘s” — core values common to many Indigenous cultures. We recognize our reciprocal relationship with Kofi Nukshopa as a food source, our responsibility to care for our avian relatives, and the importance of redistributing technical knowledge and financial assistance to land stewards who want to be good relatives.

— Aimee Michelle Roberson

back to Chahta Alhíha as well as our bird relatives. This was a wonderful opportunity to practice reciprocity, our cyclical obligation to contribute to the cycle of life and care for our community.

One of the birds whose name was not lost — Kofi Nukshopa (Northern Bobwhite) — has taught us about redistribution. In sacred kinship, the Mississippi Chahta continue to dance in honor of this avian relative. Kofi Nukshopa shares our traditional homelands and also the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma’s reservation. The Kofi hila (quail dance) helped revive our culture and reconnect Oklahoma Chahta with Mississippi Chahta from whom they re-learned dances, songs, and customs in the 1960s and 1970s. In this way, Kofi Nukshopa has taught us about redistribution — our obligation to share not only material wealth, but also time, talent, and knowledge.

(To see a video of the Kofi hila, or quail dance, go to: bit.ly/QuailDance.)

Our Roots Are Still Alive

Recalling the words of my ancestor Levi Colbert, while some of us have indeed been transplanted like an old tree, we survived Removal, and our roots are still alive. While some traditional Chahta bird names may be lost to the ravages of colonization and displacement, others are being reconnected. As we breathe new life into our language, we also revive knowledge and lifeways, seeking balance and harmony with nature.

I hope we may find our way back to wholeness. Rekindling kincentric ecosystem stewardship, including

careful tending of our gardens, communities, and lifeways, will allow us to continue to flourish. As Chikashsha author Linda Hogan writes in her book “Dwellings: A Spiritual History of the Living World”:

As an Indian woman I question our responsibili ties to the caretaking of the future and to the other species who share our journeys .… It is clear that we have strayed from the treaties we once had with the land and with the animals. It is also clear, and heartening, that in our time there are many — Indian and non-Indian alike — who want to restore and honor those broken treaties.

I am grateful to be here to learn and carry on the Indigenous values and lifeways of my ancestors as I work to conserve our feathered relatives and the ecosystems we all depend on.

Aimee Michelle Roberson is ABC’s Southwest Regional Director.

About the artists: Lokosh (Joshua D. Hinson) is of Chikashsha, Chahta, Muscogee (Creek), Cherokee, and EuroAmerican ancestry and is a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation. For more information, see: lokosh.com.

Karen Clarkson is of Chahta and Cherokee ancestry and is a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. For more information, see: clarksonart.com and etsy.com/ shop/ClarksonArt.

BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 2022-23 20

Kofi (“Quail”) by Lokosh (Joshua D. Hinson).

Birds of Different Feathers, Flocking Together

Why do different bird species roam and forage together? The quick answer: More eyes help them find food and stay safe. Particularly in the Northern Hemisphere, some members of the family Paridae, comprising the chickadees and titmice, are ringleaders of mixed foraging flocks. Other flock participants follow these birds and react to their alarm calls. The Pacific Northwest provides a lush backdrop for glimpsing how one of these cohorts operates.

The scene on the following pages takes place in winter, when food can be scarce. Unfettered from the need to breed, feed young, or defend territory, birds wander together in search of sustenance.

Each species brings a different “skill set.” By finding food in slightly different places, flock members work an area with little competition between species. Here’s how it plays out in this Pacific North west flock:

Chestnut-backed and Black-capped Chickadees often form the nucleus of feeding flocks. Versatile foragers, they hover, glean, and tip upside-down on branches to find insect eggs and other invertebrate food, seeds, and small berries. Like jays, these birds will stash food for times of shortage.

The “inspector of craggy trunks,” the Brown Creeper often loosely associates with a flock, slowly winding its way up and around a tall tree, extracting prized morsels with its “tweezer bill.”

The Red-breasted Nuthatch hitches its way up and down trunks and works horizontal branches as well. This bluish-backed bird favors conifers in winter, extracting seeds from the trees’ cones with its chisel-like beak.

The smallest member of its family in the U.S. and Canada, the Downy Woodpecker works trunks, branches, and weed stalks with its stubby bill, procuring hidden invertebrates, as well as berries and seeds.

Only a bit larger than typical hummingbirds, Ruby-crowned and Golden-crowned Kinglets are the smallest and among the most active flock members, restlessly jittering across branches while flicking their wings, and hovering at branch tips in search of invertebrate prey.

Turn the page for artist Chris Vest’s rendering of the feeding flock and other species sharing the same forest habitat.

21 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 20 22-23

(Left to right:) Chestnut-backed Chickadee by Bob Pool, Shutterstock; Black-capped Chickadee @ Michael Stubblefield; Brown Creeper by MVPhoto, Shutterstock; Red-breasted Nuthatch by Larry Master, www.masterimages.com; Downy Woodpecker by Rejean Aline Bedard, Shutterstock; Rubycrowned Kinglet by Annette Shaff, Shutterstock; and Golden-crowned Kinglet by Frode Jacobsen.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

1 Red-breasted Nuthatch 2 Western Sword Fern 3 Western Hemlock 4 Golden-crowned Kinglet 5 Douglas-fir 6 Chestnut-backed Chickadee 7 Western Red-cedar 8 Cooper’s Hawk 9 North American Porcupine 10 Banana Slug 11 Black-capped Chickadee 12 Ruby-crowned Kinglet 13 Red Alder 14 Downy Woodpecker 15 Brown Creeper 16 Douglas’ Squirrel Artwork by Chris Vest A TEMPERATE WINTER Thanks to a bounty of conifers and coastal weather influences, Pacific Northwest winters trend green and mild. In this scene you will find 16 species, including a busy foraging flock of birds, sharing a fictitious Washington forest. 13 8 9 10 11 12 14 15 16

Sowing Seeds for Bird Recovery

In the battle to save declining species, the shovel and greenhouse are a powerful sword and shield.

by Howard Youth

is when you leave the natural world to its own devices, right? That may be what many people think. Yet as we face invasive species, climate change, and widespread habitat loss and deg radation, solutions are not so simple: More and more these days, saving im periled species requires getting hands dirty. You could call it the power of the “green” green thumb.

Humans have been sowing seeds since the dawn of civilization, but now conservationists are turning over a new leaf on age-old practices — bringing back plants once plowed under or cut down, and in some cases adding others, on protected acreage, working lands, or neglected spaces.

“Planting for birds” certainly pervades ABC’s work across the Americas. To date, the organization and its partners

have planted more than 6.8 million trees and shrubs to help bring back birds and the species sharing their habitats. And it’s making an impact: From slow-growing Polylepis trees in the Andes, to endangered magnolias in the Caribbean, to nectar-producing trees valued by Neotropical migrants wintering on Central American shadecoffee farms, thoughtful planting is giving birds a helping hand.

BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 2022-23 24

Andean Alder seedlings, Peru. Photo by ECOAN.

Conservation

For a Fading

Every plant certainly counts in the race to save the mysterious and Endangered Gray-bellied Comet. This sombercolored, fork-tailed hummingbird is known from just five locations in northern Peru. There is currently no reserve protecting this species. The sloped and scrubby habitat it favors is also home to nine other endemic birds, including the Black Metaltail hummingbird, Rufousbacked Inca-Finch, and Striated Earthcreeper. Carlos A. Soto Camacho, a reforestation coordinator for Asociación Ecosistemas Andinos (ECOAN), is one of the few people working to save the comet. He leads the ECOAN effort, supported by ABC, to grow and establish native plants important to the species in its stronghold in the Chonta Canyon, five miles from the bustling city of Cajamarca.

People living and farming in the region certainly see a lot of hummingbirds, but most don’t know

Comet,

a Helping Hand

the comet. “It is very difficult to observe this species,” Soto Camacho explains. “In a day, we may see one individual or two. I’ve seen only one female in my life.” The Graybellied Comet’s already localized habitat continues to be winnowed down by livestock overgrazing, crop agriculture, and fire-setting in an impoverished region where farmers struggle to make a living working hardscrabble soil.

For four years now, ECOAN has been leasing space on a farm, where it built a greenhouse. There, Soto Camacho and his team grow eight native plant species that provide food and nesting habitat for the comet. These include two important nectar sources: a small yellow-flowering tree called the Trumpetflower or Hada (Tecoma sambucifolia) and a pink-blossomed shrub called the Campanilla (Delostoma integrifolium), which naturally grows in humid areas bordering the nearby river.

Soto Camacho and his team also grow some flowering and fruiting trees appealing to local farmers, such as the fruit-bearing Black Cherry (Prunus serotina). In the coming year, ECOAN hopes to have 20,000 to 25,000 plants in the ground, with 5,000 of those being the “incentive” plants given to farmers to encourage participation in the project.

This ECOAN effort, supported by ABC, provides paid seasonal greenhouse and planting jobs, especially during the three months when rain touches the region. That’s when community members install these plants in spaces not currently used for crops or livestock.

“In the greenhouse, the work is going well,” says Soto Camacho. “With rains, the plants in the ground do well. But rains used to be more frequent and heavier. Now, when rains pass elsewhere, the plants have trouble growing.”

25 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 20 22-23

ABOVE: Gray-bellied Comet by Thibaud Aronson.

sowing seeds for bird recovery

native plants, they see as having no benefit. And many people don’t see the comet as any different from the other hummingbirds they see daily.”

But the comet is distinctive. In the right light, the male’s tail shines an irresistible gold, and its throat flashes blue. And as it flies among the flowers, the bird feeds on different plants in different ways, probing the Hada or Trumpetflower but “robbing” nectar from other blooms by pecking a hole at a flower’s base, as do perching birds called flowerpiercers.

“No one has done anything for the comet before,” Soto Camacho says. “We are advancing slowly. If we don’t keep going, it will not survive.” As the native plants continue to grow with the help of Soto Camacho’s planting team, he looks to the future. “We need to get a lot of information out to the local communities and to the nearby city,” he says. “And we need to talk to the young ones, the next generation.”

Compounding the tricky precipitation situation is the condition of the soil: After decades of cultivation, nutrient levels are reduced. This means that planting requires not only water but added fertilizer. “The plants need monitoring and care,” says Soto Camacho, who adds that if they are not tended, just 5 to 10 percent would survive. In the normally dry conditions, plants require two to four years of regular watering before becoming fully established. The care provided by participating local farmers greatly boosts the plants’ survival rate.

Another challenge to the program is fire. “The people here believe that smoke brings rains, so after we plant, we sometimes come back and see that fire, started in nearby fields, has spread and burned down the plants,” explains Soto Camacho.

Although he frequently talks to people about their special hummingbird neighbor, Soto Camacho says it has been an uphill battle to build local support for this species and its habitat. “Fruiting plants serve the local people. But

ECOAN, ABC, and Rainforest Trust are raising funds to establish a firstever Gray-bellied Comet reserve. Soto Camacho hopes that in the future, the community will continue to find income through jobs relating to comet conservation, including not only more habitat restoration work but increased nature tourism. And he hopes that a sense of local pride will grow around this unique bird.

BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 2022-23 26

Río Chonta Valley near Cajamarca, Peru, site of the Gray-bellied Comet project: Adrian Torres Paucar, ECOAN (far left) and ABC’s Daniel J. Lebbin (far right) with local residents including Maria Amalia Culcui Chilón (next to Lebbin), whose land hosts the plant nursery. Juana Huaman (center) operates a restaurant across the street from the nursery, where she sells her hand-woven textiles. Photo by ABC.

Greenhouse interior with plants being cultivated for the Gray-bellied Comet, Peru. Photo by ECOAN.

The Thrush and the Cacao Pod: A Sweet Combo

While its nesting grounds in stunted coniferous forests of New England and eastern Canada sit locked in winter cold storage, the Bicknell’s Thrush is predominantly a bird of the Dominican Republic. There, few people see this brown-backed songbird as it skulks in the shadowy tropical montane forest. Yet this understated species, with its perilously small range, is now a bit of a celebrity, symbolizing a “sweet” marriage between forest conservation and the cultivation of cacao, the plant that gives us chocolate.

A good portion of the Bicknell’s Thrush’s winter range falls within the Septentrional BirdScape. This ABC-designated conservation landscape spans rugged mountains of

TOP: Rancho Don Lulu hotel in the Septentrional BirdScape by Daniel J. Lebbin. CENTER: The Bicknell's Thrush winters predominantly in the Dominican Republic, where sustainable cacao production can aid in its conservation. Photo by Larry Master, www.masterimages.com. RIGHT: Cacao pods by chamski, Shutterstock.

northern Dominican Republic. There, several government and private reserves dot broad expanses of cleared pasture and cropland, along with cacao and coffee farms.

One large private reserve is named Zorzal, the Spanish word for thrush. Spanning 1,019 acres, it was estab lished in 2012 to protect habitat for Neotropical migrants including the Bicknell’s Thrush, Louisiana Water thrush, Worm-eating Warbler, and Black-throated Blue Warbler, along with many of the country’s endemic bird species, like the Antillean Piculet, Hispaniolan Parrot, and Hispaniolan Trogon (see back cover).

Funds to manage and finance the reserve come from sustainable cacao production that takes place within it. For this purpose, the reserve’s founders also started Zorzal Cacao, a cacao producer that practices bird-friendly cultivation such as planting native shade-tree species and leaving as much understory as

27 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 20 22-23

sowing seeds for bird recovery

The Louisiana Waterthrush winters in the Septentrional BirdScape, where sustainable cacao operations help conserve forest cover.

Louisiana Waterthrush by William Leaman/Alamy

Stock

Photo

The Louisiana Waterthrush winters in the Septentrional BirdScape, where sustainable cacao operations help conserve forest cover.

Louisiana Waterthrush by William Leaman/Alamy

Stock

Photo

possible on the landscape. Zorzal Cacao also works with local farmers to implement sustainable practices on their properties.

Zorzal Cacao has been working with the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center (SMBC) to blend agricultural and conservation work to benefit people and wildlife, culminating in what will be the first-ever globally certified “Bird-Friendly” cacao, which should be on the market within the coming year. ABC has been supporting Zorzal Cacao in its efforts to recruit interested landowners to embrace sustainable farming and processing practices.

When grown in shade, cacao cultivation, like shade-coffee production, can help to effectively add and conserve canopy trees valued by wildlife. But depending upon

the farmer and farm conditions, this is not always feasible. So, SMBC and Zorzal Cacao also work with farmers to offset cleared “sun” cacao acreage with equal areas of protected forest. With these set-aside acres, these farmers can also be certified as “Bird-Friendly.”

This growing effort puts working lands to work for wildlife, which bodes well for the region’s birds. “We’re cobbling together this mosaic of private lands that are sustainably managed, with shade cacao being a part of this, in the context of linking to existing protected areas,” says Marci Eggers, ABC’s Director of Migratory Bird Habitats in Latin America and the Caribbean. “If we can keep finding ways to make productive landscapes bird-friendly, it can really have an impact on the entire BirdScape.”

Combining both strict protection and sustainable production, the Zorzal Reserve provides a great example for other projects. The goal there is to have 30 percent of the property under sustainable cacao cultivation. According to the company’s founder Charles Kerchner: “Our model is to use 30 percent of the land to finance 100 percent of it. That means 70 percent can be ‘forever wild.’”

29 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 20 22-23

ABOVE: Zorzal Cacao founder Charles Kerchner (standing in center), discusses cacao harvest and processing with colleagues and local farmers. Photo by Marci Eggers, April 2022. BELOW: The Black-throated Blue Warbler is among the Neotropical migrants wintering at the Zorzal Reserve. Photo by Paul Rossi.

With mature Black Ash woodlands expected to dwindle, conservationists are planting replacement species, so that woodland birds including the Red-eyed Vireo remain.

sowing seeds for bird recovery

Red-eyed

Vireo by Linda Freshwaters Arndt/Alamy

Stock Photo

A Future rising from the ashes

Conservation in the 21st century calls for normbending vision set on an uncertain future. Take northern Minnesota: There, low, wet forested areas are often dominated by mature Black Ash stands, a habitat now in the crosshairs of the Emerald Ash Borer — an introduced green beetle that drills into ash trees and kills them from within. First detected in the Detroit area in 2002, this Asiatic beetle now occurs in 36 states, including Minnesota, where it is marching north and west, likely aided by warmer winters. Often, most mature ash trees die within a few years of this beetle’s arrival.

Many Black Ash-dominated forests in Minnesota harken back to the 1930s, the decade dominated by the Dust Bowl. Then, prolonged drought

TOP: Tree-planting in anticipation of the Emerald Ash Borer's arrival. Photo by Duane Fogard. CENTER: Golden-winged Warbler by FotoRequest, Shutterstock. RIGHT: Black Ash leaves © Manitoba Forestry, CC BY-NC.

allowed lowland tree species such as the Black Ash and American Elm to take hold in places that might otherwise have been too wet for tree growth. When introduced Dutch Elm Disease swept through Minnesota in the 1970s and 1980s, these forests were left almost pure Black Ash. Today, these areas provide important wildlife habitat for woodland birds including the Ovenbird and Redeyed Vireo, and also for brushnesting species with fledged young that feed in adjacent woodlands, such as the Golden-winged Warbler. The oldest trees, now about a century old, provide cavities where Wood Ducks nest and weasels called Fishers and American Martens den.

Anticipating rapid loss of this habi tat as the borers advance, ABC and partners are trying to keep a step ahead so that bottomland areas re main forested if the ashes die off. As part of the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, a federal grant program

31 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 20 22-23

established in 2009 to accelerate ef forts to protect and restore the Great Lakes, ABC secured a grant to work with Carl ton County, the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, and the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources to plant 60,000 native trees other than ash on 100 acres of ash-domi nated sites within the Lake Superior watershed. Selected planting sites are on land with open growing space left after recent timber harvests, storm blow-downs, or where trees are dying of old age.

“So far, we’ve planted four sites and we’re trying to find some more for next spring,” says Duane Fogard, ABC’s Private Lands Forester for Minnesota. “We’ve already planted 36,300 trees; that means that we’re 60 percent done.

“We’re trying to diversify these stands,” explains Fogard. “If the ash trees were all killed at once, the wa ter table would probably come up. The hope is to keep forest on the sites, by introducing some other spe cies that will provide a seed source to replace the Black Ash. Most of these types of trees occur around here,” he says.

For this effort, replacement species include Burr Oak, White Spruce, Northern White-cedar, Yellow Birch, Balsam Fir, Silver Maple, and a tree currently found to the south that is anticipated to march north with warming winters. “Swamp White Oak is not native here but is found 200 miles to the south,” Fogard says. “We’re sort of experimenting here with assisted migration,” he adds.

The work involves careful planning and several stages of execution.

Mark Westphal, the forester for the Carlton County Land Department, explains how the collaboration has worked in his area: “Duane got the trees from the Minnesota Depart ment of Natural Resources when they became available. Prior to planting our site, the Carlton County Land Department (my boss Greg and my self) spent copious hours mowing the planting area to give the tree seed lings a fighting chance of establish ing themselves,” he adds. When the best time for spring planting arrived in late April and early May, Westphal came back with a tree-planting crew. He and colleagues followed the crew, marking the hundreds of saplings with flags. “Then we came back after the fact with tree tubes and cages,” Westphal says, “to protect the young trees from deer.”

A year later, most of the trees are well established. Westphal believes this joint tree-planting campaign began not a moment too soon. “We now have Emerald Ash Borers approxi mately 8 miles as the crow flies from that location,” he says. This means that in a few years, many of the Black Ash trees may be dead. “It’s sad and initially you want to put your head in the sand. But our collabora tion gives me hope. We’re a small

county with a small land base. Being able to have groups like ABC come in to facilitate this tree-planting is important. It makes economic and ecological sense to us. And we think it will make a difference.”

ABC thanks George and Cathy Ledec, Kathleen Burger, Andrew Goodwin, and Larry Thompson for supporting Graybellied Comet habitat restoration efforts.

ABC’s work in the Septentrional BirdScape has been generously supported by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Neo tropical Migratory Bird Conservation Act grant program; Environment and Climate Change Canada; Richard and Nancy Eales; and Andrew and Patricia Towle.

The Black Ash project is funded by a Great Lakes Restoration Initiative grant through the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 2022-23 32

ABOVE: Ovenbird by Dennis W Donohue, Shutterstock; LEFT: Emerald Ash Borer, CC BY 3.0 us.

Howard Youth is ABC’s Senior Writer/Editor.

sowing seeds for bird recovery

This Winter, Plan to Plant for “Your” Birds

Wherever plants can be put in the ground, bird habitat can be created or enhanced. Gardening can be richly rewarding, and when it comes to wildlife gardening, thoughtful toil in the soil reaps great benefits both to birds and those who love to watch them.

Winter is the perfect time to plan a wild make-over for garden spaces. Here are six bird-gardening tips you can follow to do some conservation planting of your own:

• Big pruning and cutting projects are best done in late fall and early winter, when trees and shrubs are dormant — and when birds aren’t nesting.

• Plan to plant native shrubs and trees that provide optimal food, cover, and nesting places.

• Most birds feed their young copious amounts of invertebrates, so go pesticide free if at all possible,

and leave as much leaf litter and native underbrush as you can, so a diversity of invertebrates will overwinter.

• Learn to identify native plants important to birds, so you can locate “volunteer” plants — those that pop up on their own. Buy those you need from a grower or nursery; do not collect native plants from the wild.

• In many areas, a few types of introduced, invasive vines, shrubs, or trees can overwhelm native plants valuable to wildlife. Learn to identify these weeds and how to control them on your property.

• Plant in fall, winter (if in a mild climate), and the start of spring so you can focus spring through summer on observing wildlife using your habitat. (At that time, some weeding, minor pruning, and occasional watering would be main activities.)

Northern Mockingbird in Common Winterberry bush.

Photo by Danita Delimont, Shutterstock.

ABC BIRDING

BUENAVENTURA RESERVE , Ecuador

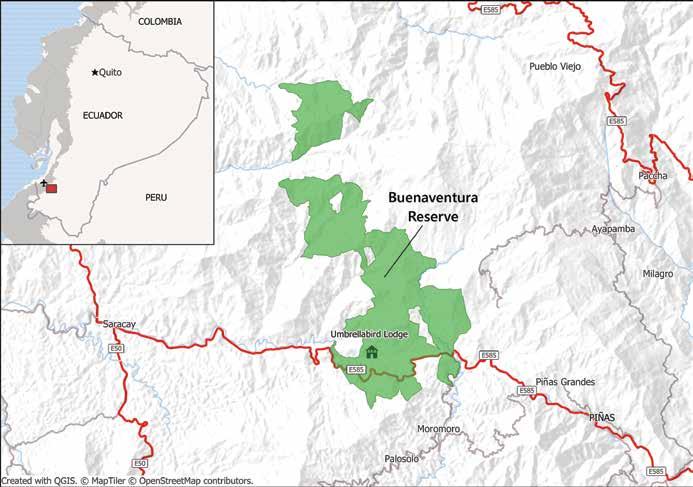

Lay of the Land: The Buenaventura Reserve spans 9,947 acres of lower montane cloud forest in the southwestern Andes of Ecuador. This incredibly rich and varied protected area ranges from 1,500 to 3,600 feet in elevation and blends elements of the flora and fauna of two ecoregions — the Chocó, which runs from southern Colombia to the reserve area, and the Tumbesian, which runs up from northwestern Peru.

Focal Birds: About 370 bird species have been recorded in the reserve, according to the eBird database. These include two Endangered endemic bird species — the El Oro Parakeet and El Oro Tapaculo — as well as the Endangered Gray-backed Hawk. The latter species is found only in a handful of locations in Ecuador and far-northern Peru. A few other species regularly seen at the reserve include: Rufous-headed Chachalaca (listed as Vulnerable to extinction on the IUCN Red List), White-whiskered Hermit, Green Thorntail, Violet-tailed Sylph, Green-crowned Brilliant, Crowned Woodnymph, Violet-bellied Hummingbird, Yellow-throated and Choco Toucans, Black-andwhite Owl, Guayaquil Woodpecker, Red-masked Parakeet, Club-winged

LEFT: Among the many wildlife sightings a visitor to Buenaventura Reserve might enjoy: a display ing male Long-wattled Umbrellabird. Photo by Greg Homel, Natural Elements Productions.

Manakin, Long-wattled Umbrellabird (Vulnerable), Ochraceous Attila (Vulnerable), Bay and Song Wrens, Swainson’s Thrush (a winter resident), and Bay-headed, Golden, and Silver-throated Tanagers.

Other Wildlife: White-nosed Coati, Central American Agouti, Mantled Howler Monkey (Vulnerable), Brownthroated and Hoffmann’s Two-toed Sloths, and Red-tailed Squirrel. Many other mammals occur, including the secretive Puma, Ocelot, and Northern Tiger Cat (Vulnerable). Plant life includes many rare species, such as a recently discovered magnolia that is still being described.

When to Visit: A visit to Buenaventura Reserve will be rewarding at any time of year, but note that the rainy season runs from December to March. From October to June, male Long-wattled Umbrellabirds are an outlandish sight as they display on a lek near the lodge: The birds lean forward, extending and flaring their long black-feathered wattles, then utter low “mooing” calls. See a male umbrellabird in action at: abcbirds. org/blog/cool-birds.

Conservation Activities: The reserve was established in 1999 by ABC partner Fundación de Conservación Jocotoco to protect the El Oro Parakeet, first described in 1980, and the El Oro or Ecuadorian Tapaculo. The reserve has been expanded several times since, with support from ABC and other partners. Degraded habitats acquired for the reserve have been either allowed to regenerate or replanted with

35 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 20 22-23

TOP: Green Thorntail by Greg Homel, Natural Elements Productions. ABOVE: Mantled Howler Monkey by Marcelo Tognelli.

native species. The El Oro Parakeet population has thrived under protection and benefited from a successful nest box program.

El Oro Province, where the reserve is located, is now mostly an agricultural landscape, with only a small percentage of original cloud forest remaining. Recent reserve expansions aim not only to provide protection for species, but also to connect already-protected habitats and higher-elevation areas that provide extra insurance if species’ ranges push higher due to the effects of climate change.

Directions: One of the easiest ways to reach Buenaventura is to fly from Quito to the southwestern town of

LEFT: Buenaventura Reserve is the only protected area for the endemic El Oro Parakeet. A successful nest box program has helped boost the population of this Endangered species. Photo by Greg Homel, Natural Elements Productions.

BELOW, from left to right: Rufous-headed Chachalaca by Marcelo Tognelli; El Oro Parakeet by Marcelo Tognelli; Guayaquil Woodpecker by Nick Athanas.

BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 2022-23 36

Santa Rosa. From there, it’s an hourand-a-quarter drive to the reserve. The reserve can also be reached via a four-hour drive from Guayaquil.

Where to Stay: The Umbrellabird Lodge is located on the property and features a deck and dining area thronging with hummingbirds that visit the feeders there. Dining com panions may include a coati or two. Accommodations include five cabins, each with a private bathroom. The reserve's extensive trail system can be accessed from the lodge. For in formation, see: conservationbirding. org/?reserve=buenaventura-reserve

In the Area: Several other stel lar Jocotoco reserves dot southern

Ecuador.

37 BIRD CONSERVATION | WINTER 20 22-23

Many visitors to Buenaven tura continue on to Tapichalaca Re serve (higher-elevation cloud forest and home to the Jocotoco Antpitta), and to dry-forest habitats at Utuana

and Jorupe Reserves, close to the Peruvian border.

ABOVE: One of the cabins at Umbrellabird Lodge. Photo by Benjamin Skolnik.

On the inset map, the shaded area shows where the Chocó and Tumbesian ecoregions occur. The Chocó runs from Panama down to western Ecuador, where it approaches the Tumbesian, which reaches up from northern Peru. The Buenaventura Reserve protects species of both ecoregions. Map by Marcelo Tognelli.

As a child growing up in the Detroit metropolitan area, Brianna always loved animals — especially horses — but she did not have a lot of access to the outdoors, until her grandmother found a place where she could ride horses for free, in exchange for stall-cleaning and other duties. In high school, Brianna went trail riding in northern Michigan. It was her first time out in nature. “I was blown away,” she says. “I never knew any of that was out there.” This is more of Brianna’s story, in her own words.

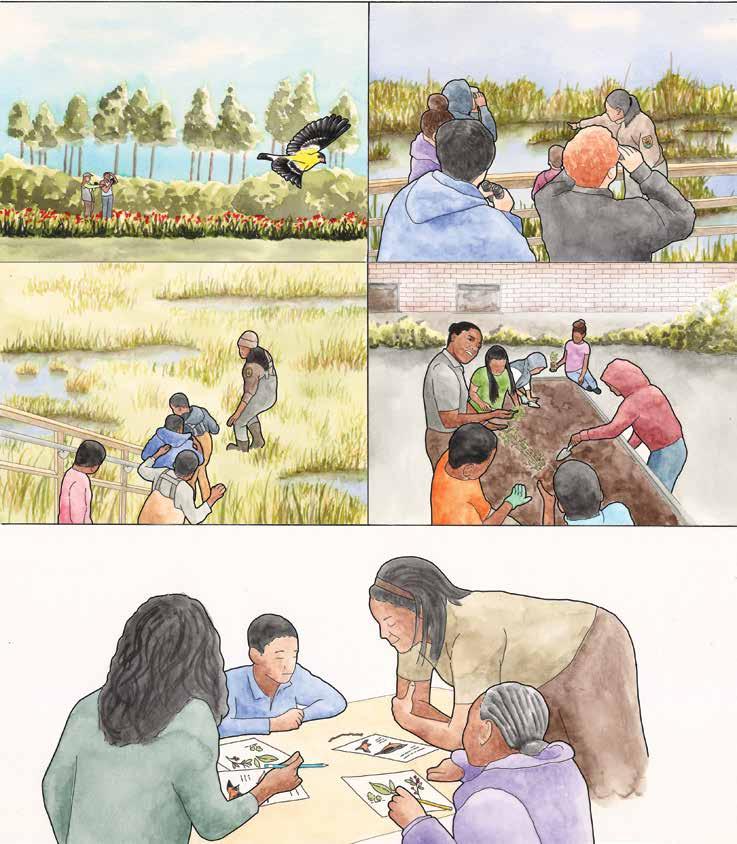

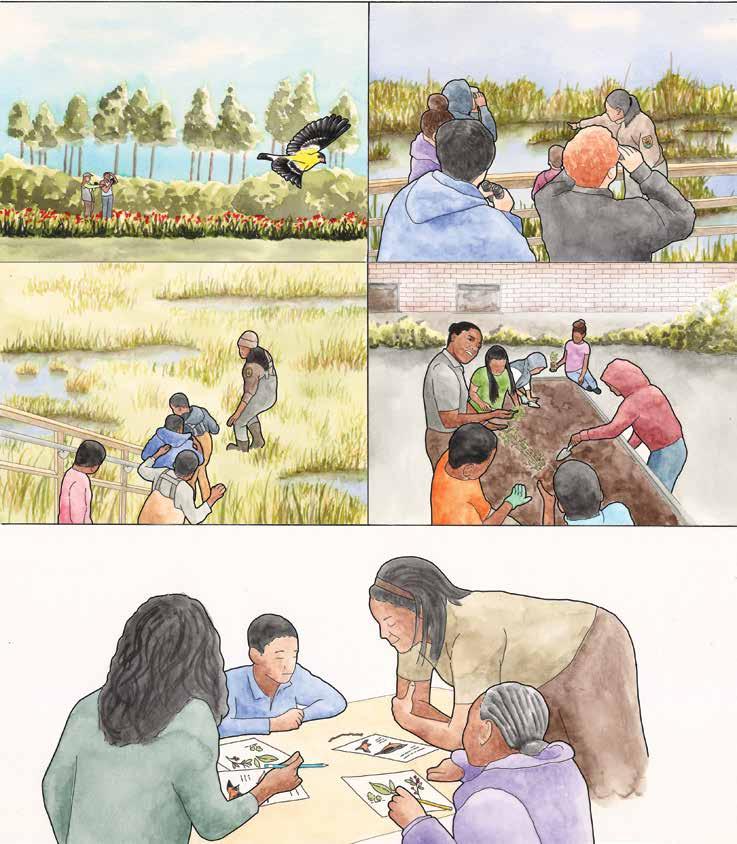

At Michigan State University, I majored in animal science. For the summer, I applied for an internship with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), which I had never heard of before that time. I wound up interning for FWS each summer of college. My first summer, ranger/educator Laura Bonneau at Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) in Ohio took me out birding and showed me an American Goldfinch. I’d never seen a yellow bird before.

Five years ago, I moved to Philadelphia to be Environmental Education Supervisor at John Heinz NWR, which was founded in 1972 as “America’s first urban refuge.” We see a lot of birds here (eBird reports 312 species). Sharing observations with others is my favorite kind of birding — especially with kids and families.

I manage the refuge’s education program, particularly Philly Nature Kids. Each year, about 150 fourth-grade students — all living within a few miles of the refuge in Southwest Philadelphia — meet with us every other week for the whole school year (about 20 times).

It’s great to see them connect with a refuge right in their backyard.

I enjoy working with city kids like myself and also want to widen that reach to others not just right here, but through digital work, including through Black Birders Week, an annual series of online events that began in 2020. It’s amazing to see people connecting across the globe and shining a light

Laura pointed out the species’ “potato-chip…potato chip…potato chip” flight call. She got me very excited about birds. For more information: • fws.gov/refuge/john-heinz-tinicum •bit.ly/PhillyNatureKids

As they work with us on nature-based stewardship projects in their community, refuge, or school, it's amazing seeing the change in the students: Many start out uncomfortable in the outdoor environment. Then they start to see it as part of their neighborhood.

on all the different ways that Black people engage in nature, from recreation to conservation and everything in between!

Award-winning watercolor painter Beatriz Benavente lives in Spain, where she specializes in scientific and bird illustration. You can follow her on Instagram: www.instagram.com/wildstories.art

A Legacy for the Birds That Remain

For nearly 60 years, I have followed the decline and extinction of Hawaiian birds, an avifauna that has suffered the highest extinction rate of any geographic area on Earth. In just my lifetime, I have seen seven Hawaiian bird species in the wild that are now extinct. The situation is very sad, but I never give up hope for those species that remain.