15 minute read

2 Chapter 2 - Literature review

2.1 Introduction

India is known to have dramatic urban growth where it constantly outstrips even the most perspicacious planners’ vision (Roy,2009). The spatial context and background of the area have the capacity to assist us to generate an identity for the space. Following that, it serves as a foundation for establishing criteria for analyzing the area, which is required to determine future sustainable development. There is an even greater urgency in the case of emerging nations like India, which are spending heavily on urban infrastructure projects (Bhattacharya, Patro, and Rathi, 2016). In the second part, we examine the literature on urban sustainability sectors, the frameworks for conducting such an examination, and the fundamental tenets and ideas of sustainability that come from different fields of study.

Advertisement

2.2 History and context

2.2.1 What is urban infrastructure

In simple terms, the urban environment controls how we commute, work, gather, enjoy, and generally go about our everyday activities; to put it another way, the physical architecture of a city's streets and buildings dictates our actions. The fact that we, as users, are bound to rely on the built environment and have a special relationship with it makes it so blatantly clear when the system breaks down (Reiner and Rouse, 2017). There are two types of urban infrastructure: physical infrastructure and social infrastructure. The physical infrastructure, also known as hard infrastructure, comprises transportation, drainage, sewage, water, power, and so on. In contrast, the social infrastructure includes community amenities such as residential complexes, healthcare centers, parks, emergency services, and so on (Mahanta and Borgohain, 2022).

The fragility of the social, cultural, and economic systems that compose a city is tested by the disruption of our physical infrastructure, which also demonstrates how these sectors rely on the functioning of our infrastructure facilities (Reiner and Rouse, 2017) The social infrastructure, on the other hand, builds resilient communities and may be used to entice foreign investment and spur economic expansion. Social attributes enhance communities’ well-being and are crucial for integrating sustainable communities (Mahanta and Borgohain, 2022). Bengaluru, one of the leading global cities, has been dragged down by its infrastructure (Carvalho, 2022); it is one of the most desired places to live due to its weather conditions; yet, it requires adequate infrastructure, which has resulted in dire living conditions that have reinforced negative impacts of traits such as segregation and informality, resulting to low livability and aggravating the poor's situation.

2.2.2 Segregation of Minorities.

It is troubling that India's Muslim community, now the world's third-largest, is subject to residential segregation along religious lines (Susewind, 2017). Present-day India has a significant fraction of its Muslim population living in ghettos (Gupta, 2015a). When neighborhoods are mostly divided along racial, religious, or other social lines, we often use the word "ghetto" (Gupta, 2015a). The availability of public services, such as schools and hospitals, tends to be lower in Indian cities where the Muslim population is more significant Muslims of India are known to be historically disadvantaged people. The practices of racial residential segregation incorporate the social segregation of race with that of the materialistic segregation of property ownership (Armstrong-Brown et al., 2014). Low-income Segregation is a unique problem for India's Muslim population, which differs from other populations in the country (Susewind, 2017) India's religious communities have a troubled past, leading to widespread discrimination and segregation due to security fears and bias. (Susewind, 2017). African Americans in the United States experience segregation is comparable to that of India's minority groups. The same is true in India; caste segregation is associated with poorer incomes and educational opportunities in urban areas, just as it is in the United States (Adukia et al., 2019).

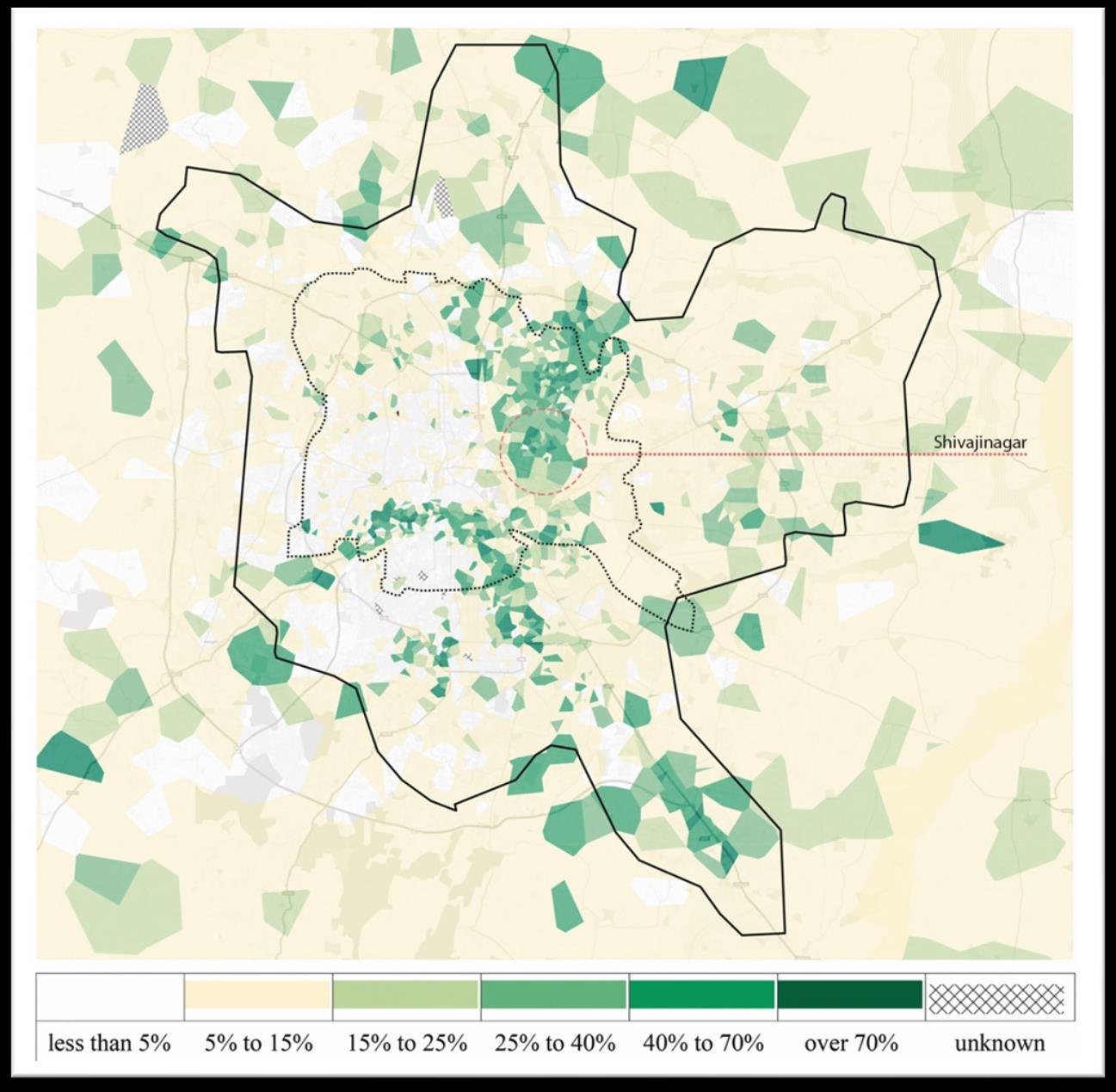

While religious persecution is not a major issue for Muslims in Bengaluru yet, they do have other worries about urban livability (Sen, 2013) The Muslim populations in Bengaluru have been thrown into instability and are starting to fear their security as a result of recent swings in political power, and this has led to more segregation and widened gaps in the city's socioeconomic structure. Shivajinagar is also a part of residential segregation but mainly due to its colonial past in the spatial distribution of the population. It initially started as a ghetto, a vital area that once witnessed the significant mobilization of Muslims in the city (Arif and Aminah, 2012). These low-income ghettos are often bagged with negative inputs where they are denied a proper urban infrastructure. Inhabitants in these regions are prone to relocations and are sometimes compelled to engage in interventions that violate government legislation.

It is known that Muslims living in a neighborhood with a 10% more Muslim population are 7.5% poorer, and the others are 6% poorer. One’s health and educational attainments may be negatively impacted by living in a neighborhood with a high minority population. A family's precarity is exacerbated when they must contend with the stresses of segregated neighborhoods with limited access to essential services (Gee and Payne-Sturges, 2004). Over time Shivajinagar, which once started as a ghetto through forced relegation has now become a home to low-income people and attracts new residents who see it much more as an enclave.

2.2.3 Informality in urban infrastructure

In India's largest cities, the informal urban landscape is prominent. In affluent nations, problems were solved by tearing down whole cities or sections of cities, a process known as urban renewal; in India, however, the country's urban centers were never razed and rebuilt from scratch, leading to a more chaotic and unplanned form of urbanism (Vidhate and Sharma, 2017). Another explanation is the prevalence of urban difficulties such as unforeseen and unregulated urban expansion, a rise in the number of urban people living in informal settlements and slums, and the difficulty of delivering urban services to everyone (Sandoval, Hoberman and Jerath, 2019).

Since its founding 450 years ago, the city of Bengaluru has been a major trade Centre. It’s Shivajinagar neighborhood has served as its core market, with its avenues and plazas serving as informal public areas. (Patel, Furlan and Grosvald, 2021b). Roy describes 'urban informality' as "a condition of exception from the formal order of urbanization." (Roy, 2005) In a condition of informality, land ownership, usage, and purpose are not established by any legal or regulatory structure (Roy, 2009). Most cities in developing countries have slums or other forms of informal habitation that have grown over time. Slums in India are deemed informal, hiding a wide cultural variety under a veil of extreme poverty and limited access to services (Roy et al., 2018).

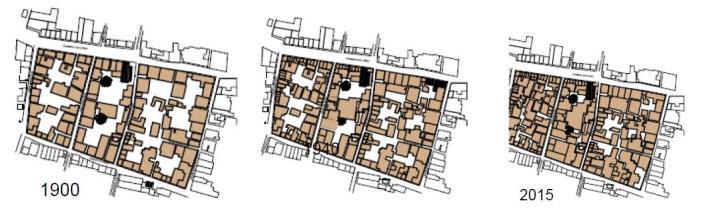

In areas such as Shivajinagar, the bigger question arises why some of these areas are now judged to be unlawful and subject to destruction while others are protected and formalized. Here, the variation does not exist between formality and informality but rather within informality (Roy, 2005). Indian cities' use of privatized planning and methods to ensure their future viability buying principles shows that the country would not be able to effectively plan its cities unless it gives urban informality a higher priority (Roy, 2009). Informal development has been a critical aspect in Shivajinagar regarding residential settlements Chandni Chowk is a small block of Shivajinagar that was formerly famed for its many courtyards. Still, these have been transformed into a collection of private buildings, which is a prime example of contributing to the area's congestion (Patel, 2018).

The impoverished and the marginalized are not the only ones living in informality (Sandoval, Hoberman and Jerath, 2019); informality is a very diverse attribute often found in every aspect of urban interventions in India.

2.2.4 Urban infrastructure and its relation to Livability

Theareas dominatedbypoorminorities have caused majorconcerns regardingthequality of urban livability (Mahanta and Borgohain, 2022) There is currently a lack of research into the concept of urban livability, which is a behavioral function of the interplay between the urban environment and individual characteristics (Mahanta and Borgohain, 2022). It is an essential characteristic of a city to fulfill its users’ needs and expectations. Physical and economic well-being, fundamental security, cultural expression, and a feeling of belonging to a group or a place are all included in the broad definition of livability (Martino, Girling, and Lu, 2021). Urban infrastructure is a distinctive case of infrastructure that forms a close relationship with livability.

A city’s livability may be explained by assessing the quality of the city's urban infrastructure from the perspective of its citizens. Accessibility, equality, urban security, comfort, mobility, transportation, and urban transportation all contribute to a city's livability and are impacted by the same set of principles (Shabanzadeh Namini et al., 2019). In recent times, Bengaluru has just been ratedby theEconomist IntelligenceUnit as India'sleast livablemajormetropolis (Carvalho, 2022) The lives of those who reside in the neighborhood are strongly intertwined with the characteristics of informality and segregation, which have a significant impact on the livability criterion.

2.3 Delivering a sustainable framework for cities

2.3.1 Concept of sustainable cities

The situation in many of our contemporary cities is such that only a few can access infrastructure and services that are of higher quality and equivalent to first-world levels; most others are denied access to even its most rudimentary form (Benjamin and Bhuvaneswari 2006). Ecologically sound urban environments and natural environments are founded on solid infrastructure. Infrastructure is commonly misinterpreted in urban studies, which view it through the lens of massive construction projects rather than the lens of people going about their everyday lives (Taufen and Yang, 2022b). Sustainable development may be thought of as the kind of growth that helps the current generation without sacrificing the potential of future generations to cope with their own demands (Nkhabu, 2021) Understanding how the urban environment interacts with people's unique traits is crucial for creating a sustainable city because it continues the process of changing urban infrastructure to improve the quality of urban space.

As India creates a lens to guide the sustainability of urban infrastructure, this article will identify elements of sustainability that have been overlooked in locations like Shivajinagar, which is also the situation for most of the ghettos across India (Bhattacharya, Patro, and Rathi, 2016) Creating sustainable urban development indicators is an ongoing process that has received a lot of attention and resources. There are three mainstays of sustainability that must be established to build a framework that provides for sustainability. A practical framework must incorporate the three most crucial pillars: economic, social, and political. (Bhattacharya, Patro, and Rathi, 2016). The framework which will be developed will act as a mechanism that will be responsible for the entire assessment, inquiries, and monitoring of urban infrastructure within Shivajinagar. A better understanding of the challenges faced in Shivajinagar is crucial for designing future sustainable cities since low-income communities are often exposed to negative living situations. To better grasp the present state of affairs, I will construct a framework for assessing global and Indian indicators across urban infrastructure sectors, taking into account the 3E's of sustainability.

United Nations member states have accepted a set of goals outlined in "Changing our planet: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development" with the express purpose of forging a link between the three pillars of sustainable development (Leal Filho et al., 2018). It is essential to consider the SDG, which plays a crucial role in understanding sustainability based on the context. India was 121st out of 163 nations on the Global Index of Sustainable Development in 2022. The position steadily dropped between 2018 and 2021 (Bansal, 2022). This paper proposes a framework for the four central guiding principles principle which will cross-cut the three pillars and the SDG objectives which are closely related to urban infrastructure. The following section describes each aspect briefly, which will further help us set out questions for the people of Shivajinagar.

2.3.2 Accessibility in urban infrastructure

When talking about a city, "accessibility" refers to how convenient it is for residents to access various services and opportunities. There is a strong correlation between inequity in urban neighborhoods and barriers to accessibility. The gentrification processes in developing countries, along with residential segregation and informality, have, over time, forced low-income minority groups to dwell in urban neighborhoods that have degraded and been denied access to a significant fraction of government investment (Nicoletti, Sirenko, and Verma, 2022) Increasing accessibility for specific populations is critical since it will allow them upward socioeconomic progress and significantly curb urban social isolation and disparity. Access to a neighborhood mainly depends on the ease with which people can travel throughout the city. Transportation is one of the most critical factors in making cities long-term sustainable. Individuals who are disabled confront extensive barriers to accessing built environments ranging from roads and houses to public buildings and places in developing cities. Inadequate accessibility places disabled persons in precarious circumstances, resulting in excessive poverty rates (www.un.org, n.d.). Accessibility should be considered a long-term investment that contributes to successful, sustainable, and equitable development for everybody, rather than just a cost or compliance concern (www.un.org, n.d.) Low-income individuals and families Nowadays, having access to essential services is more of a luxury than a right. A proper and well-executed infrastructure is derived from well-planned accessibility to demonstrate its commitment to economic reform, be it roads, schools, business centers, housing, hospitals or health centers, markets and social centers, parks, stadiums, etc., Inaccessibility issues have arisen in many parts of India due to historical neglect of religious minorities and current social unrest between religious groups (Adukia

et al., 2019)

2.3.3 Inclusivity in Urban Infrastructure

Inclusive is an ideology that believes that the possibilities and benefits of progress should be extensively shared with all members of society (Florida and McLean, 2017) The potential for a moreinclusivefutureis crucialto thesuccess oftheworld and its cities oftomorrow. Toendsevere poverty and promote economic stability, it is essential to understand that the concept of inclusive cities requires an inclusive range of spatial, social, and economic considerations (World Bank, 2017). As a result, the most recent efforts in global development have had to place a greater emphasis on environmental challenges, such as providing infrastructure in transit, homes, health, sanitation, and social health. It is crucial to comprehend and build a concept containing elements like urban inclusion to guarantee that current and future cities give opportunities and improved living situations (Majid Cooke, 2006, p.208). The most disadvantaged members of society need to have their rights protected and be given a fair chance to participate in society as a whole. This is especially important in today's urban areas, where residents are increasingly being asked to share their opinions on the causes and effects of social and economic unrest. However, many city dwellersarestill unableto reap theadvantages ofgrowth becausethey lack access to basicservices (World Bank, 2017).

The worldwide social and economic components of urban inclusion are closely intertwined and tend to follow a negative route, trapping people in poverty and denying them opportunities; hence, a more corrective and suitable strategy is needed that may raise people out of exclusion and better their lives. (World Bank, 2017). Inclusion and sustainable infrastructure need to be evaluated and integrated through a Governing body (Municipal) that will make it function successfully over the long term and cover all city segments. Services that exclude the poor are not inclusive as, over a period, they fall into neglect or disrepair or deplete the area’s natural resources. Therefore, it is necessary to have a comprehensive plan through an upfront assessment to be incorporated in the designs and implementation process, thereby successfully able to control and sustain the infrastructure networks for an extended period (50 years) before another round of significant capital upgrades (USAID, 2011).

2.3.4 Health and well-being in urban infrastructure

Health is a crucial concept for sustainable and urban development since it directly affects people's morality and well-being via the activities and interactions they build in their surroundings (Stimson, 2013). Factors like social setting, environmental exposures, toxicity, social structures, mental health, and physical health all add to the whole lifespan. At the same time, socioeconomic status, education, nutrition, housing, and access to vital utilities all contribute to good living conditions and are therefore of paramount importance (Yang and Taufen, 2022). Well-being is the domain of comprehensive measure of health, and the main factors that influence good health, and well-being are driven by its relationship to urban parks, cultural centers, and places of social interactions.

A modern measure of well-being is evaluated through aspects of day-to-day life activities and accessing how society facilitates or inhibits the enjoyment of life (Larson, Jennings, and Cloutier, 2016). Today it is seen from a broader perspective to the growth factors like physical, and mental health, community attachment, and economic security are more fully interdependent within the domain of health and well-being (Larson, Jennings and Cloutier, 2016). It is found that residents with access to greener urban areas display a more positive indication of mental health and selfconfidencehencethe concentrationofparks andgreenspaces arekeycorrelatesofhealthand wellbeing (Larson, Jennings and Cloutier, 2016).

Intheglobal south, informal areas showvulnerability thatmayplayasignificant rolein developing health problems. Many people are more likely to be exposed to environmental contaminants such as air pollution, which may lead to elevated stress levels (Gee and Payne-Sturges, 2004). Air pollution is one of the biggest concerns in Indian cities and is closely related to the city's transportation system Bengaluru is now the most congested city in the world (Mishra, 2020), with rising difficulties in air quality and non-communicable diseases. Seventy percent of fatalities in India over the last two years have been attributable to NCDs (Kanwal, 2022).

Mobile phone gaming has surpassed outdoor activities among both young and elderly, and the proliferation of social media has replaced face-to-face interaction, leading to increased isolation and a decline in physical activity (Banerjee, 2019) Long hours spent in front of screens at the workplace have been a significant contributor to the rise of the sedentary lifestyle in recent years due to shifts in the work culture, particularly after the release of covid-19 (Banerjee, 2019) and the lack of green spaces in low-income ghettos has aggravated the issue of having an active lifestyle within the community.

2.3.5 Reliability and resiliency of urban infrastructure

Our daily lives entail contact with a wide range of vital infrastructure, which puts individuals in the position of its reliability, where reliability may be defined as the capacity to not fail. Reliability is the key to efficient cities since it directs and analyses a city's performance in terms of resources to accomplish the city's objectives (Bhattacharya, Patro, and Rathi, 2016). The present state of our nation's infrastructure is primarily due to degradation caused by age and a lack of asset maintenance, which directly impacts its resilience (Reiner and Rouse, 2017). Another essential aspect of reliability is resilience, which is defined as a system that performs the same tasks or recovers fast after stress or disruption. Infrastructure resilience is critical in surviving natural disasters, with flooding being one of the most severe difficulties that Indian towns face. Urban flooding produces substantial infrastructural challenges, massive economic losses in terms of output, and severe damage to property and products; it not only ruins physical buildings but may also impede or entirely obstruct movement (Ramachandra and Mujumdar, 2009)

Rises in impermeable surfaces are a leading cause of flooding because land use shifts from open to impervious surfaces in the catchment region due to increased urban development (Ramachandra and Mujumdar, 2009). As a result of corruption, city planners in India only focus on short-term problems. Corruption also adds to crumbling infrastructure; recently, a group representing state contractors accused state authorities and officials of pressing them to contribute a commission of 40% on govt contracts (Carvalho, 2022), demonstrating that it is challenging to finish a new project, let alone maintain the existing infrastructure. For resilient infrastructure, rapid recovery from stress or absorption of the impact is essential, but there is a gap between the directions for hazard intensity and post-disaster restoration and the day-to-day problems of public works and utility management. Achieving the aims of sustainable development requires a strong and long-term perspective, which may be gained via the regular practice of foresight. This will foster a dedication to highlighting the city's long-term concerns and objectives, and it will assist construct the capacity to address future disasters.

2.4 Conclusion

The literature research makes it clear that sustainability is a multifaceted concept that depends on a web of interconnected variables that work together to better the lives of people. Additionally, this has assisted in developing the conceptual framework for evaluating the Shivajinagar neighborhood's urban infrastructure.

2.5 Conceptual framework

The ability of individual countries to adapt the global indices to their contexts will significantly impact how far they have come in achieving the SDGs. A growing body of literature shows how factors local to an individual, particularly segregation and informality, have a role in shaping their upbringing and hence their subsequent abilities and character (Kling and Liebman, 2004; Chetty and Hendren, 2018).The literatureledto theformation ofaframeworkbasedonthefourindicators such as inclusivity, accessibility, mental health, and reliability, which act as the background to evaluate further the current situation of the picked neighborhood (Shivajinagar).

The first 11 sectors are selected as they are recognized by the ULBs (Urban Local Bodies) in India and evolved from the basic requirements within the context of physical and social infrastructure. The 4 indicators extracted from the concept of sustainability will be used as a basis for developing questions on the 11 urban infrastructure sectors. The diagram below explains the conceptual framework of the research as we next move on to the methodology.

2.6 Research gap

It is essential to highlight the challenges being faced as increasing poverty within these segregated neighborhoods may deter human capital accumulation and further encourage crime (Adukia et al., 2019). As I completed the literature review, I identified a gap in the research within the context of minorities. many pieces of research on low-income minority areas have been done using quantitative methods without understanding the context's background and essence. It is essential to know that the concept of sustainability is context-specific and has different annotations in diverse cultural and geographical contexts (Zetter and Georgia Butina Watson, 2017) Especially in Bengaluru, no efforts have been made to understand the people’s situation of the marginalized group and their accessibility to urban infrastructure. Most of the studies I read on Shivajinagar focused solely on the city's politics, and the few that touched on urban revitalization efforts there were quite limited. This raises the topic of what is going on in this area, which has sparked the interest of several scholars. This is where I step in, aiming to fill the hole of how a ghetto’s urban infrastructure, such as Shivajinagar's, is failing and, more significantly, how it impacts the people who live there.