The traditional nomadic ger becomes sedentary in the city.

The traditional nomadic ger becomes sedentary in the city.

The traditional nomadic ger becomes sedentary in the city.

The traditional nomadic ger becomes sedentary in the city.

For thousands of years, Mongolians have been living in gers —circular structures of timber and wool felt wrapped in stretched white canvas and pulled taught with horsehair rope. The ger is a highly evolved design object, easy to disassemble, move, and reassemble in a matter of hours without any tools or fixings. For these reasons it is a perfect dwelling for nomads who move up to 500 kilometers each year in search of seasonal pastures.1 Historically, however, the ger has been a part of all forms of Mongolian settlements, urban or rural, and it remains the most affordable form of dwelling today.

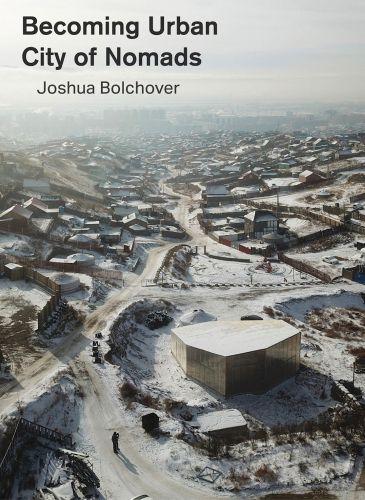

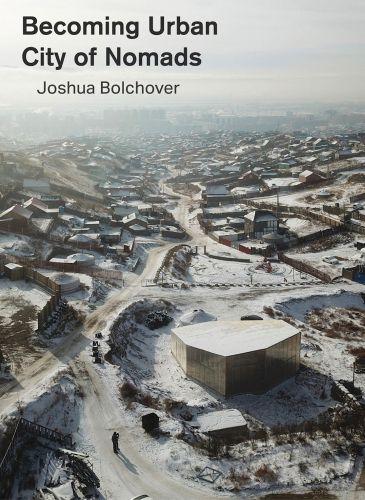

Mongolia’s 1990 democratic revolution and the subsequent collapse of Soviet state control precipitated a rapid rise in migration into the capital city of Ulaanbaatar, which saw its population increase 280 percent between 1989 and 20202 while its area extended to 35 times its original size.3 The influx of people has resulted in the sprawl of settlements known as ger districts, which extend outward from the city, carpeting the valleys and hillsides with a mix of one- to two-story brick houses and traditional gers. This sprawl comprises thousands of individual plots, each surrounded with a two-meterhigh fence (6.6 foot) wall made from wooden posts or salvaged metal. When walking the dirt roads of the districts, these barriers block views into each home, where typically a dog barks vociferously as you pass.

The summers in the countryside were beautiful. The days were long. Back then we milked the sheep and goats twice a day. The grown-ups herded the sheep and goats while the children herded the lambs and the kids. We used to take them to the river and play all day. We took turns herding them, but mostly we just played at the banks of the river building mud gers.

Being a herder requires a lot of skill and intuition. It’s not just work for the unemployed. The Mongolian heritage is truly in being a herder.

O yunbat

O yunbat

Today a visit to the ger districts of Ulaanbaatar reveals a context that is a complex interplay between the urban and the rural that has formed its own unique identity and spatial character. It is not an in-between condition on a linear trajectory from nomadic to sedentary life but something distinct, offering a viable alternative between the countryside and the traditional city center.

Ger districts are not new phenomena. They have always been present in Mongolian cities, functioning as sites of exchange and reconciliation between nomadic and urban life. Historically, ger districts would expand and contract at the edges of more permanent settlements in response to seasonal trading or religious festivals. To this day, any permanent urban center in Mongolia still has its own contingent ger district. However, their evolution on the fringes of Ulaanbaatar represents something new. Here the ger districts have become sedimented into an urban fabric, containing over 840,000 residents who mostly own their land and their property. 28 It could be argued that they make up the defining entity of Ulaanbaatar itself. A proportion of ger district residents are migrants who moved only recently from the countryside. 29 For these recent arrivals, the districts do represent a hinge between urban and rural life, a place of transition from nomadic to sedentary living and assimilation to urban life. Other new residents came after giving up on city apartment living, having chosen the ger districts as an affordable opportunity to own land and build a house. At the same time, 45 percent of residents have lived in the ger districts for over 20 years and have no intention of moving. 30

The Gandan district today.

The Gandan district today.

The first settlement of Ulaanbaatar, Urguu, was founded in 1639 by Mongol nobles to consolidate Mongolian national interests as a reaction to the occupation of Inner Mongolia by the Manchus. Operating as a monastic trading post, the town itself was nomadic for its first 139 years, relocating somewhere between twenty-five and forty times before occupying the area of the current city. 50 Mongolia succumbed to the Qing Dynasty in 1691, and it was this influence, together with the influx of traders and religious figures, which resulted in the formation and growth of more permanent structures in the area.

These eventually developed into the settlement of Ikh Khuree, which was administrated from 1778 to implement Qing policies. During this period, the city evolved into a religious and trade node where Buddhism and commerce thrived. This initiated the creation of more permanent structures within the emerging city. Accounts of the settlement at this time describe a mixture of permanent brick and stone structures mainly associated with religious buildings, some residents living in low-rise mud huts, and expanding areas of ger districts housing traders and monks alike. 51 Traces of this embryonic city remain: the temple structures built between 1834 and 1838 within the Gandantegchlin monastery led to the formation of a ger district around its edges that forms the Gandan area today, the territory inscribed by the district having outlasted the impermanent nature of its building typology.

My wife is a kindergarten teacher, but she’s currently at home looking after our baby son. Because I live in a ger, the first thing I do in the morning is build a fire. Then I prepare the wood and coal for the rest of the day and drop my daughter off at school before heading to work. I spend most of the day working in my studio.

At the moment, I’m focusing on building a house on my plot rather than trying to get an apartment. But the conditions are difficult, like the water for example. To build a house, you have to manually bring the water from the well. Even after you build your house there’s still the problem of heating.

The expanse of ger districts that carpet the hillsides and valleys of Ulaanbaatar.

The expanse of ger districts that carpet the hillsides and valleys of Ulaanbaatar.

Zulaa, twenty-six, and Urangua, thirty-three,67 live in a ger on the edge of Bayankhoshuu, one of Ulaanbaatar’s ger districts, a thirty-minute drive from the city center. Like other migrants to the city they have had to transition to sedentary living. They now have neighbors, take buses and taxis for transportation, and are confronted with debilitating air and ground pollution found in the city. Zulaa works at a printing company where she makes wholesale cardboard boxes and Urangua works at the Gobi Cashmere factory. Their combined monthly income, after taxes, is around ₮1,200,000, or $490.

Due to the lack of basic infrastructure in the ger districts, the couple spends a significant amount of their income, and their time, on basic needs. There is no piped, running water in the district, so they collect and pay for it from the local water kiosk—a round trip of forty minutes that involves lugging plastic containers of water uphill on a trolley—at least eight times per week, rain or shine. There is no sewage infrastructure, so they dug a two-meter-deep pit latrine. When it is full, they will dig another hole. In the extreme winter, with temperatures reaching -40ºC (-40ºF), the couple must light a coal fire at least three times a day, equating to a fuel cost of 20 to 30 percent of their income.

The couple is far from unique among the 840,000-plus people who live in the ger districts, accounting for over 60 percent of the city’s population.68 With the population of the city growing by an average of 38,000 each year between 2000 and 2019, 69 and 21,000 of those accountable to the ger districts, the urban risks associated with this form of settlement are becoming increasingly threatening, particularly with respect to sanitation,

New migrants claim a plot of land, fence it in, erect their ger, and dig a pit latrine. Over time, if they can afford to, they will build a baishin, or small house, like this family on the edge of Khan-Uul ger district.

After the difficulties we encountered with the waste collection points, we continued to actively engage in the ger districts. We shifted our focus to deepen our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the growth of the settlements in order to better position design strategies that could change future patterns of the urbanization process there. We made this research the subject and focus of architectural studios we taught at the University of Hong Kong in 2016 and at Columbia University in 2017. The studios enabled us to conduct a parallel line of investigation that used the constraints of the conditions as a springboard to generate more speculative design projects. They also provided an opportunity to become more engaged with the community by conducting fieldwork, household interviews, and workshops with local people to get feedback on proposals. The fieldtrips and workshops provided energy and momentum to the project that otherwise might have been lost without a definitive building commission.

The first workshop was in the winter of 2016 in a primary school in Sukhbaatar-16, involving combined groups of residents and students drawing and sketching over three different scaled aerial photos of the district, highlighting ideas for scenarios of future change. The second workshop, in the summer of 2016, was a collaboration with a vocational training school, the Institute of Engineering and Technology (IET), in which we designed and built the timber structure of a housing prototype that could plug into a ger. Critical to the success of these trips was the involvement and collaboration of Badruun Gardi and Enkhjin Batjargal. We had met them both on our very first trip to Ulaanbaatar in 2014, when they

The completed Ger Innovation Hub in winter, January 2020.

The completed Ger Innovation Hub in winter, January 2020.

Under the current model, planning of the ger districts is done almost entirely under the auspices of the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The ADB conceives and initiates redevelopment plans through collaborations with government bureaus, international consultants, and local partners. Following the approval of such projects in the Mongolian parliament, the ADB provides preferential loans to the government and assists with project implementation and coordination of different specialist consultant teams. The present, ADB-backed strategy for ger district development is to create four subcenters, with connections to high-speed bus routes and new infrastructure to support densification in the form of five- and six-story townhouses.142 The intention is to stimulate the housing market and assist developers by preparing the land for development. This includes confirming land exchange agreements with landowners, funding infrastructure, and negotiating preferential mortgage rates for consumers.

The ADB plan to improve housing is contingent on residents voluntarily exchanging their 500 to 700 square meter (5382 to 7534.7 square foot) plots of land for 37 to 42 square meter (398 to 452 square foot) apartments. Economic recession has meant income levels of ger districts are low—on average ₮1,157,500 ($406) per month 143 —while promised ‘low-interest’ mortgages for the housing are much higher than expected, at between 8 percent and 16.8 percent. This means that the success of the market-rate housing component of the ADB scheme is uncertain, which has put off developers. Even if successful, the tracts of housing currently planned for development at the Bayankhoshuu, Selbe, Dambadarjaa, and Denjiin subcenters will only provide capacity for approximately 12 percent of

All my life I have lived in a ger and only in the last decade or so, I have lived in a baishin. I struggled and struggled to reach this life. Wow! All my kids have grown up with their own families and are living comfortably. I worked very hard to raise my kids alone, but now, all is good.

Oyunchimeg Dunkher

1

Нэг өнөр өтгөн айл үр үү дийн амт дундын гал тогоо ба угаалгын өрөөтэй тус тусын гэртэй нэг орон сууцанд амьдарч боло юм.

One large family of several generations can share one Apartment House with one kitchen and one bathroom and use a ger for sleeping.

2Гурван өөр гэр бүл тус тусын угаалгын өрөө, гал тогоо ба гэртэй байж боло 3 нэгж бү ий нэг орон сууц зэрэг сонголтууд үүсч боло юм. Three different families could each have a separate unit with their own bathroom and kitchen and use their individual gers for sleeping.