In a period of just a little more than 20 years, Brigitte Bardot exploded established perceptions of beauty and femininity. In doing so, she dramatically rewrote expectations around – and perhaps even established a new version of – femininity. She was a movie star and a pop-culture icon whose image was emblematic of a particular moment in time. This book celebrates her legacy and the two photographers whose images of her have become a significant part of the visual record of her life.

Bardot’s film career spanned 21 years, from 1951 to 1973. Her screen performances, and the still images of her that became such a constant and vivid element of popular culture, brought a new sense of what female movie stardom could be, not only in French cinema but globally.

Certainly, there were those who found Bardot’s presence in the movies of the 1950s and 1960s a shock. In 1956, a rather flustered Raymond Cartier, editor of the magazine Paris Match, said of Bardot that she was ‘immoral, from head to toe.’ But there were many, too, who found her image and performances liberating and inspiring. For the feminist writer Simone de Beauvoir, Bardot embodied a ‘modern version of the eternal feminine.’ 1 She rode a cultural wave that moved the idea of being a woman from a long-established sense of reserve and modesty to a far bolder, more assertive and sexually forthright kind of expression. First as a model and then as a movie star, her awareness of her own sex appeal saw her shape and steer it with increasing power.

Early in her career, Bardot was considered a muse to the filmmaker Roger Vadim, who was married to Bardot between 1952 and 1957 and who directed And God Created Woman, in which Bardot starred. In an interview with The Washington Post in 1986, Vadim said of her, ‘I did not invent Brigitte Bardot, I simply helped her to blossom.’ 2 Perhaps she was also a muse of sorts to the photographers who worked with her. But she would move past this condition. In doing so, she gave expression to a newfound attitude of thought and action for women, one that encouraged independence from men’s approval or agency. The art historian Ruth Millington writes that ‘with the

arrival of feminism came a much-needed critique of the muse… it was during the so-called “second wave” of the ’60s and ’70s that the feminist art movement drew particular attention to systemic sexism, inequality and discrimination ingrained in the arts, as well as wider society.’ 3 While not specifically concerned with Bardot, Millington’s very contemporary observation taps into so much of what Bardot represented.

Bardot’s beauty also carried with it an enduring power and meaning, especially for the audiences who had been there when Bardot arrived on movie screens in the 1950s. That moment of impact and the way that it evolved was key to Bardot’s movie career. The idea of beauty has been a constant feature of human culture for millennia. It has found a place for itself in all of the arts, including cinema. Brigitte Bardot’s movie star image is a milestone on that journey. Bardot and the allure of cinema are ineluctably connected and this book captures that romance between the movie star and the movie camera; between the audience and the star.

While Bardot’s fame offered her a powerful role in shaping new perceptions of beauty and femininity, the scale of her fame impacted her own wellbeing in profound ways. In 2012, she spoke to Olivier Lalanne for Vogue Homme magazine, one of very few interviews in the decades since her retirement from film and a particular kind of public life. In that conversation, Bardot noted in an unvarnished, tragically inflected comment that ‘I was literally crushed by celebrity. No one can imagine how awful it was. A nightmare. I just couldn’t live like that anymore.’ 4

Where France had Brigitte Bardot, America had Marilyn Monroe. The images of both women continue to resonate today; each endlessly appropriated and repurposed across all media. In the same 2012 interview, Bardot said of Monroe, who she met just once, ‘She was unique. So sublime. I felt I was light years behind her.’ 5 Both Monroe and Bardot were very much defined and understood by appearance and image. They shared a respective sense of wit and self-awareness regarding those images. As such, they empowered themselves, staking their own place in pop culture.

Born on 28 September 1934, Bardot was perfectly timed for the emergence of the French New Wave cinema of the late 1950s. Critically, Bardot’s principal stardom emerged and developed very much within the world of the French film industry through the 1950s and 1960s, and yet her image travelled globally and remains a touchstone.

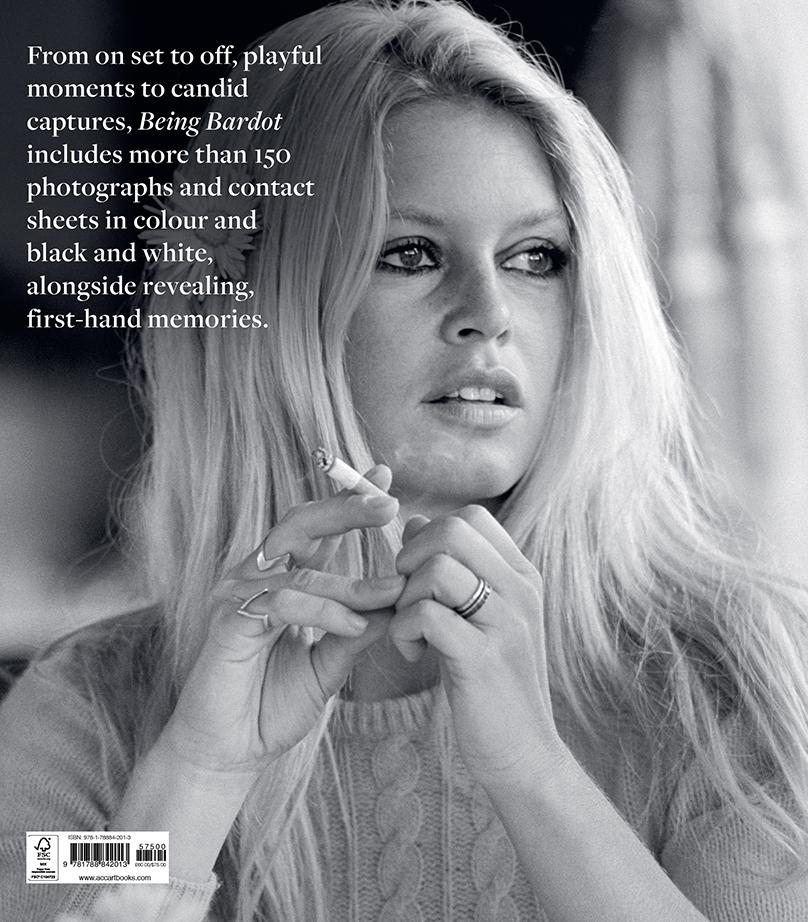

In their work with Bardot, Terry O’Neill and Douglas Kirkland each contributed to the story of Bardot’s career and the ways in which beauty came to be rethought for a modern and contemporary audience. This book showcases and celebrates not just Bardot but the work of O’Neill and Kirkland as well. Contemporaries and friends, both created definitive images of the actress in the latter years of her film career, and they each played a vital role in shaping the wider image of Bardot.

O’Neill and Kirkland each had distinctive ways of recording Bardot in portrait mode, in any number of candid images that show her on-set between takes, alone and in the company of others, at play and in repose. A number of images in this book are published for the first time and go some way to suggesting the rapport that O’Neill and Kirkland had with Bardot. In certain shots, there’s a sense of Bardot admitting O’Neill and Kirkland into her inner life. In the selection of photos by Douglas Kirkland, for example, there’s a set of images of Bardot playfully presenting herself from behind blue curtains during time away from the set of Viva Maria! Elsewhere, we see her hiding her luminous smile and letting a more pensive version of herself emerge.

As their respective careers blossomed, both Douglas Kirkland and Terry O’Neill were photographing female film stars who, like Bardot, inspired many women to find their own sense of liberty through the energy and excitement of pop culture. By the time they came to work with Bardot on a variety of film productions, they had each established themselves as leading photographers of film stars in both Hollywood and European cinema. Critically, both O’Neill and Kirkland were able to capture and contribute to the screen persona and image of the film stars they

encountered, and they were each able to nurture a rapport with their subjects, allowing for more candid, maybe more authentic images to be taken. In a conversation with the American Society of Cinematographers’ magazine, Kirkland commented: ‘My thing is to be honest, and most celebrities respond to that.’ 6 This captures a distinction shared with O’Neill. When it came to photographing the stars, they knew how to use the camera to dissolve the distance that might otherwise exist.

Discussing film-set photography in his book Every Picture Tells A Story (ACC Art Books, 2016), Terry O’Neill recalls, ‘I was able to capture some great, unscripted moments. Actors having fun, reading, eating, sleeping; but when the cameras are about to roll and the actor is waiting to go, there’s a lot of standing around going on.’

These ebbs and flows in the energy of a shoot on the set of the 1971 Western Les Pétroleuses (The Legend of Frenchie King) gave O’Neill the opportunity to take what would become one of the most iconic Bardot images of all. He explains, ‘It was a windy day, and she was standing and waiting to film a scene. I was just wandering around the set, looking for opportunities and taking a few photos here and there. I noticed she kept brushing the hair out of her eyes… combined with the cigarette dangling from those lips – I knew it would capture how sexy, strong and wild her image was.’

By this point in her career, Bardot was an international star, with a filmography of nearly two decades to her name. No one knew that only two short years later, she would retire from making movies.

As Bardot herself once said, ‘A photograph can be an instant of life captured for eternity that will never cease looking back at you.’ 7 Together, both O’Neill and Kirkland helped shape and define Bardot’s image beyond the cinema, her movie star legacy, her fashion stardom (Bardot’s choucroute beehive hairstyle remains a style aspiration) and her wider pop-culture recognition. Their photographs go some way in contributing to her standing as a revolutionary figure and remain vital illustrations of a 20th century icon.

A photograph can be an instant of life captured for eternity that will never cease looking back at you

BRIGITTE BARDOT