Goff Books

FROM RIGA TO OMAHA: THREE GENERATIONS OF ART

Edgar Jerins is a first generation Latvian American artist born in Lincoln, Nebraska, in 1958. His parents, Rita (née Cepure) and Gunars Jerins, both grew up in Riga prior to the Soviet re-occupation of Latvia in 1944. When World War II ended, they both spent the next six years living as “displaced persons” in refugee camps in Germany. Throughout this period, however, their paths never crossed. It was only after each immigrated to the United States that the couple finally met, this courtesy of mutual friends in the tight-knit diaspora of Latvian asylum seekers. The couple married in 1952. Gunars worked as an accountant, and Rita supplemented the family income through a series of part-time jobs. All the while, she continued to make art, a lifelong passion she’d inherited from her father.

Over the next seven years, the Jerins had four children, all sons. The oldest, Ron, was himself an artist with extraordinary promise. Ron was followed by Edgar, who idolized his older brother’s artistic talent, followed by Tom and finally Alex.

Edgar, who was 64 at the time of this writing, is the only member of his family left alive.

The factors influencing every artist’s vision and trajectory are multiple, idiosyncratic, and complex. In Edgar’s monumental Life in Charcoal series, he combines astonishing technical mastery with deep empathy and compassion for his careworn subjects. Many of these subjects are close friends and relatives of the artist, people who at the time of their portraits were facing a crisis in their lives, from mental illness and drug addiction to economic privation and broken homes. Edgar’s ability to capture in art not just their suffering but their ennobling endurance in the face of it is the work of someone who knows adversity firsthand—a veteran traveler in the land of sorrow and travail.

If you’re lucky enough to meet Edgar in person, you’re unlikely to see this side of him, at least not at first. Most come away with an impression of tremendous bonhomie. What they see in Edgar is a generous, non-judgmental, understanding, and extremely humorous soul—one of those rare individuals who makes fast friendships in every social stratum, from indigents to movie stars.

This impression of Edgar, though accurate, is also incomplete. To understand Edgar’s insight into the darker side of the human condition, it’s best to start in childhood, not his but rather that of his immediate immigrant ancestors.

What follows is a short history of the Jerins family saga as told, as much as possible, through their own written and spoken words.

After Edgar’s mother Rita enrolled at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, she was assigned to write an essay about her early life. An excerpt:

Life in Latvia

My life's journey started in a faraway country called Latvia. Situated on the shores of the Baltic Sea between Russia, Poland, Estonia, and Lithuania, it has been a battle ground for countless political struggles throughout the centuries. It has been invaded by Germans, Poles, Swedes, and Russians. Latvia gained its freedom after World War I in 1918 and lost it again in 1940 when Russians invaded Latvia.

My childhood memories are from the time when Latvia was free and during the Russian and German occupations. We lived in a house that was situated near a beautiful park. I remember little hedgehogs coming out in the evening. We sometimes got them and brought them in the house and gave them milk to drink.

My parents were both teachers. My father had just graduated from the Academy of Art in Riga and besides teaching was painting and doing exhibits and other artistic endeavors in the community. It was a happy time.

I had two younger brothers and quite a few cousins, uncles, and aunts. On holidays and summer vacations, we went to our grandmother Anna Grinberg’s house, where we would sometimes have to help with watering and weeding plants in the greenhouse—my grandfather Karlis had four greenhouses and made his living selling plants. We also enjoyed trips to the seashore, visits to our country relatives, and mushroom and berry picking in the forests.

The happy times ended in 1940, when the Russians invaded Latvia. The aim of the Soviet government was a systematic extermination of Latvian leaders—political, economic, educational, cultural, and clerical.

The Soviet government nationalized all savings accounts over 1,000 rubles [about $20 in US dollars]. Similarly, all industrial and commercial establishments, real estate, and farmlands were nationalized without compensation.

People were arrested for trivial reasons or for no reason at all.

All publications were under censorship and libraries were ransacked and books objectionable to the new regime were destroyed.

Many high-ranking military officers disappeared—some to a military "camp" in Moscow. The rest were ordered on maneuvers, surrounded by Soviet troops with automatic weapons, and massacred on the spot.

During the Soviet occupation, people were afraid to talk openly even with their friends in fear of arrest, torture, and deportations. My mother lost her job as a teacher, and the Secret Police were looking for my father.

In the night of June 13, 1941, the Soviets arrested 16,000 people including children and deported them in cattle cars to slave labor camps to Russia where most of them perished.

The year of terror ended when German troops ousted the Soviet forces from the Baltic states. Latvians were hoping for a restoration of their government, but one occupation was merely replaced by another. While Gestapo ruthlessly exterminated Jews and gypsies and patients in mental institutions, the Nazis interfered very little into the Latvian cultural and religious life. Four years went by, and in 1944 the Germans were retreating from Russia.

When the Russian front was only 30 kilometers from Riga, and after we had spent many nights in the air raid shelters, our family decided to flee Latvia.

The family’s first move was to a refugee camp in Germany controlled by German soldiers. Hitler considered Latvians Aryan and worthy of protection from the invading Russians. Rita’s brother, Uldis, who would later become a Lutheran minister, describes the next step in the family’s odyssey.

We were sent to a little town in the mountains called Brandoberndorf. My mother had to work in a factory. It was a small factory. They made bunk beds there. One night we saw how Wetzlar, a manufacturing center, burned. Another night we saw how Giessen burned. These cities were not more than twenty miles from the place where we were, and that didn't let us to forget that the war was going on and that every day people had to pay for it—guilty or not.

We lived in Brandoberndorf till American forces took us over.

Rita also recalls this day, in the spring of 1945, when the American troops arrived in Brandoberndorf and liberated it.

There was no resistance in the village when the American troops came. The tanks and guns just rolled by. Some troops stopped and set up an outdoor camp near our barrack. The soldiers were friendly and passed out gum to the children. They had an outdoor religious service in the morning.

Soon afterwards, on May 8, 1945, Nazi Germany surrendered to the Allies, ending World War II in Europe. For the Cepures, armistice meant moving from a German-controlled refugee camp to a series of refugee camps, still in Germany, but now controlled by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency. The move improved their living situation greatly. They were no longer forced to work. Even better, they were no longer starving.

Uldis, who was 10 years old, remembers his family’s first moves after the War. After the Americans came, we were somewhat confused about where to go and what to do. We heard that in the city of Wetzlar, the refugees were gathering and there was a relief organization called UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency). Our family and others went to Wetzlar. First, we lived in a small hotel, but later we were moved to an army camp outside the city. We became displaced persons.

Though she didn’t know it at the time, Rita would end up spending most of her adolescence, from age 12 to 17, being shuttled from one refugee camp to another throughout Germany.

TO understand Edgar Jerins’ insight into the darker side of the human condition, it’s best to start in childhood, not his but rather that of his immediate immigrant ancestors.

The camps, though far from luxurious, offered more than just the basic amenities. Each camp quickly established a school for the refugee children as well as a theater to provide entertainment for the whole community. Rita’s father did the set designs and painted scenery for the productions. Besides attending school, Rita was blooming as an artist in her own right. Art supplies were in short supply, so she often had to make do with burnt sticks instead of pencils to draw with. Despite this, her son Edgar says today, her sketches of camp life were excellent. From grandfather, to mother, to her sons, and now to Edgar’s daughters, artistic ability has been passed through the generations like a Cepure family heirloom.

Four nations—England, Australia, Canada, and the US—had agreed to accept some refugees. By luck, Rita’s family had ended up in American-controlled camps, and they held out hope the US would soon take them in. But US officials initially had a different idea: Latvian refugees, they argued, should be sent back to Latvia. For the Cepures, this was an untenable option.

As Rita wrote:

Most foreigners who were in Germany were happy to return to their native countries—except the ones from communist occupied lands. The Russians and some Poles were forcefully deported back. Many resisted and many committed suicide, because they knew what fate awaited them at home. We had no country to return to and were allowed to stay in Germany. UNRRA moved us from camp to camp quite often.

During the years in Germany, we were moved to six different camps. In the fall of 1945, the first Latvian schools began classes. There were more than 200 schools in operation, which ranged from kindergarten to university level—all were taught by professional teachers.

There were also many cultural activities and organizations in the camps, from theater to song festivals.

Churches of different denominations were established, and I was confirmed in a Latvian church in Germany.

Books and newspapers were printed and widely read.

Our living quarters were crowded, but we had adequate food, while the German population was starving after the war. The Germans were willing to part from their treasured family possessions for a can of Spam or Crisco. Coffee and cigarettes were precious.

Daina & Doyle at Home With Anita’s Children

60” x 96” Charcoal on paper 2007

Goff Books

Goff Books

Goff Books

Goff Books

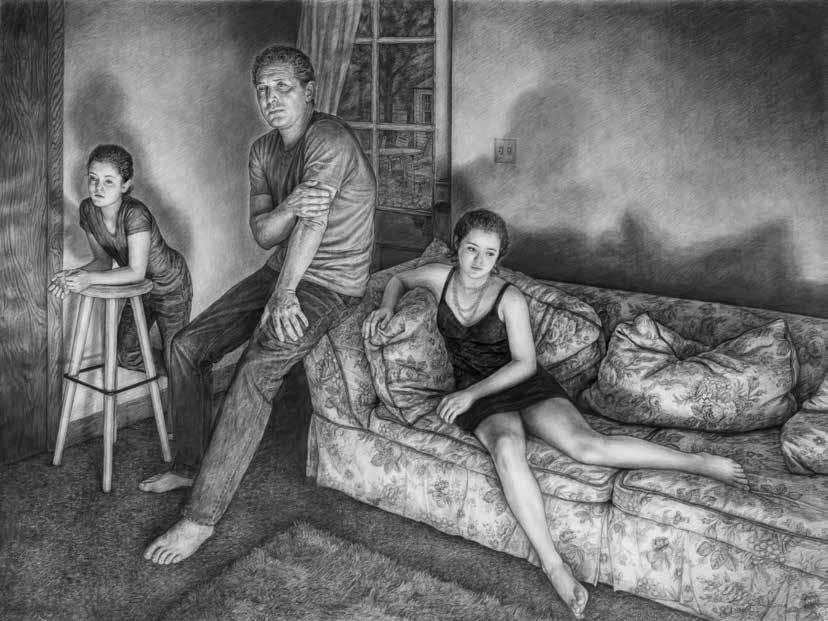

Emma and Kiera at Dads

60”x 86” Charcoal on paper 2009

Goff Books

Goff Books

Goff Books

Anita

Goff Books

Goff Books

Goff Books

TWIN SUBJECTS INTERVIEW THEIR ARTIST: A COLLOQUY BETWEEN LIFELONG FRIENDS

In 2001, artist Edgar Jerins completed a nearly life-sized portrait of middle-aged identical twin brothers and their elderly father. Drawn in charcoal, it was one in a series of acclaimed narrative portraits of Americans facing hard times. The twins’ father, Jake Thornton, died several months after the drawing was completed. He never learned how Edgar’s work would immortalize the three Thorntons.

The next year, NYC art dealer Peter Tatistcheff gave Edgar a one-man show of six of these monumental drawings. Prior to the show’s opening, Townsend Durant Wolfe III, director and chief curator at the Arkansas Art Center, traveled to New York to view them. Gazing at the Thornton portrait, he announced he had to acquire it for his museum’s permanent collection. “I’ve never had any collector purchase an artwork so decisively,” Tatistcheff would later tell Edgar. “This was the first time Townsend purchased a drawing outright.””

One of the twins, documentary filmmaker John Thornton, drove up from Philadelphia to attend the opening. Two decades later, he still recalls being gob smacked by the exhibition.

“With Edgar’s new body of work,” John says today, “I felt he had finally reached his full potential as an artist. His drawings were technically brilliant but

also deeply moving–a portrait of human endurance that I just hadn't seen depicted in art. I've read it in novels, like Russell Banks’s Affliction and The Sweet Hereafter, but I’d never seen it drawn. Edgar’s drawings are as good as any art you’ll ever see.”

John and Edgar first met as students at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art in the 1970s. Soon thereafter John introduced Edgar to his twin brother, Jim. The three have remained the closest of friends ever since.

Jim Thornton, who won a National Magazine Award for journalism in 1998, recalls thinking how his accolade was nothing compared to being a subject in one of Edgar’s artworks. “Magazine writing is ephemeral and soon forgotten,” Jim says. “But I imagine hundreds of years from now, art lovers will still see Edgar’s drawing of our father, brother, and me—and still marvel at the artist’s skill.”

The three friends recently talked through FaceTime. Their conversation has been edited for clarity.

Jim: Edgar, you said that before you began this charcoal series, John had given you a brutal critique of one of your oil paintings.

Edgar: It was an image of a siren and a drowning man that I’d created out of my imagination. I was excited about it and brought it down from New

York to Philadelphia to show John. Ever since art school, we’ve been critiquing each other’s work and encouraging each other’s efforts.

Jim: A siren? That sounds a bit pre-Raphaelite.

Edgar: It was. I love the pre-Raphaelites. Art critics have tended to dismiss their work as maudlin. John and I were taught in art school to consider it as well-made kitsch. I remember talking with a fellow student from Great Britain, and I told him I thought the Pre-Raphaelites were terrible. He looked surprised and said, “No! They’re quite wonderful!” Art school has its prejudices as to who the winners and losers in art history are. At that moment, I reassessed what I had been told and realized I agreed with my British friend.

Jim: When you showed John the siren painting, were you secretly hoping he’d love it?

Edgar: Well, at least like it. But he did NOT, right John?

John: Let me first say that at the time, Edgar’s wife, Alana, was pregnant with their first child, and he was doing everything he could to make money from art: commissioned portraits, Christmas cards, album covers for the Trans-Siberian Orchestra. He was also hired to paint angels for a series of collectible ceramic plates.

Goff Books

100

Daina and Tiger

22" x 30" I Oil on paper I 2017

Collection of Eric Brecher

100

Daina and Tiger

22" x 30" I Oil on paper I 2017

Collection of Eric Brecher

In all these projects, his technique was impeccable, and the images were beautiful. But the philosophy imprinted in us at the Pennsylvania Academy was to pursue art for art’s sake. And angels on plates wasn’t that.

So, I was sympathetic to Edgar’s financial situation. But when I saw this painting of the siren, I had an overwhelming sense he was squandering his talent. One of my favorite Edgar pictures of all time was a pastel portrait his cousin Mike back in Omaha. It was realistic, it belonged to our own times, and it was absolutely honest. It showed Edgar’s ability to really get at human life. To me, the siren painting was just an imitation of something from the nineteenth century—technically. Technically great but empty.

Jim: How’d you break the news to Edgar?

Edgar: (laughing): John’s critique was a double slap. “Edgar,” he cried, “not only have you appropriated nineteenth-century painting technique!” Slap! “You’ve also appropriated nineteenth-century subject matter.” Slap!

John: Edgar, I’m sorry if I hurt your feelings. Had I not truly believed you could do so much better, I wouldn't have said anything.

Edgar: What you said was one hundred percent accurate, and like all good critiques, it had to be tough. It completely changed the way I paint. I went back to New York, and my next major painting was of Alana. She was a couple weeks from the due date of our first child. We both knew our lives would soon be transformed. I’d painted Alana many times before—she was even the model for my angel plates. Had I still been under the sway of the nineteenth

century, I probably would have tried to capture the ethereal beauty of a young woman on the cusp of maternity. Now I wanted to capture the reality of Alana’s late-stage pregnancy. She agreed to model for me nude on a plain wooden chair in my studio. When the painting was finished, she said she liked it more than any other portrait I’d done of her. She said it was because she could see her true self in it.

John: Wow! I didn’t know that.

Edgar: That painting is also the reason the Tatistcheff Gallery offered me my first New York one-man show. All this happened, John, because of your critique. So, thank you!

Jim: What kinds of work did your dealer want you to create for the show?

Edgar: He said he’d show whatever I wanted to paint, but he also presented me with a challenge. For artwork to be noticed in New York, he said, it must have an edge, it must be difficult. Difficult work isn’t “pretty.” What he was telling me was like what John said. In effect, Peter was daring me to make work that doesn't sell.

John: That’s such a great challenge. He was opening a door for you to do anything.

Edgar: When he asked me about my life, I told him about the suicides of two of my brothers. I told him how Tom, my only remaining sibling, was slowly killing himself through alcoholism and drug addiction. I had always hoped to paint the darker side of my life, but I could never figure out how to do it. If I tried to conjure an image, it’d be my older brother, Ron, lying on the floor with a bullet in his head.

John: Edgar, I can’t imagine living through the things you’ve endured. Maybe I’m making too much of it, but in so much of your early art, the aim was to create paintings that were beautiful and uplifting.

Edgar: Right. Life-affirming. I used art as a refuge from the sadness and trauma I’d experienced.

Jim: It reminds me of Goya, whose whole artistic trajectory changed after he witnessed the carnage of the Napoleonic Wars.

Edgar: Goya has always been one of my favorite painters. Before the war, he did a lot of beautiful portraits of the aristocracy as well as sketches of common folk enjoying popular pastimes of the day. It was only after Napoleon invaded Spain that he went on to create the “Black Paintings” for which he’s so famous today.

John: Did living in New York during 9/11 play any role in your artistic change of heart?

Edgar: The 9/11 experience was traumatic for every New Yorker who lived through it, and I was no exception. But what had a much greater impact on me personally was when my dad died of a heart attack. He had long been my brother Tom’s main support system, and after he died, Tom just got sicker and sicker. I thought I’d soon be the only Jerins kid left.

Jim: How old a “kid” were you then?

Edgar: I was just turning 40, an age when you get a clearer sense of how the rest of your life is likely to go. You’re not exactly old, but you’re no longer young. Youthful dreams of fame and fortune have faded, if not entirely evaporated. By forty, most working artists I know have no money and are really

Goff Books