AWAY FROM THE ACADEMY

Emile Claus was active in the Antwerp art world in the first decade of his career. Both during and after his studies at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (1869–74), he had an o cial address in the city.1 But why did he choose the academy, run by Nicaise De Keyser, instead of its more progressive counterpart in Brussels headed by Jean-François Portaels, or even the Ghent art school led by Théodore-Joseph Canneel? Around 1865, although the Antwerp academy enjoyed a reputation both at home and abroad, it mainly drew young people from Flanders; Claus’s fellow students included Evariste Carpentier, Juliaan Dillens, Edgard Farasijn, Frans Joris, Jef Lambeaux, Jan Van Beers, Frans Van Kuyck, Piet Verhaert and, last but not least, Théodore ‘Door’ Verstraete, who became one of Claus’s closest friends. 2 Many trainee artists from abroad were also registered; Claus kept in touch with some of them, such as the American Francis ‘Frank’ Davis Millet and the Finn Albert Edelfelt. 3 The reputation of the Antwerp academy would not have escaped Claus, who was a country boy. But the fact that he was able to start these studies in October 1869 (when he was already 20) was mainly thanks to two people: the Waregem collector and philanthropist Felix De Ruyck, a patron of the local art school, where Claus took lessons around 1865, and fellow West Fleming Peter Benoit, who since 1867 had been director of the Flemish Music Academy (today the Royal Conservatoire of Antwerp) in the city on the Scheldt (figs. 3–8, 129 & 130).

The training at the Antwerp academy rested on a long tradition. In the elementary course, students drew [une] tête ombrée d’après l’estampe (‘a shadowed head after a print’). In the intermediate grade, Claus’s professors – Polydore Beaufaux, Edouard Dujardin, Jozef Geefs, Jozef Van Lerius and Nicaise De Keyser himself – all without exception followed the principles of history painting. Their classes were devoted to composition d’histoire, dessin d’après l’antique (statue, expression), anatomie (squelette), anatomie (muscles), perspective pittoresque (‘historical composition, drawing after the antique (statue, expression), anatomy (skeleton), anatomy (muscles), picturesque perspective’) and so forth. The advanced course included the class peinture de torse d’après nature, as well as the generic classes esthétique et littérature générale and histoire. In other words, the programme o ered a practical as well as a broader intellectual training. On 3 May 1874, Claus completed his studies at the academy; he obtained a vermeil medal, coming second after the now forgotten Charles Peeters, but ahead of Edelfelt.

Alongside the classical training, independent artist studios played an important role in a student’s artistic education. During his earliest days at the academy, Claus, thanks to the intervention of Felix De Ruyck, found work at the private studio of Jozef Geefs, possibly together with Jef Lambeaux. As Claus wrote to his brother Jules, he was not there “to do a bit of sculpting, but to paint plaster Stations of the Cross in natural colours. That way I can absorb the style.”4 In the summer of 1874, he was o ered the role of assistant in Nicaise De Keyser’s studio, a highly sought-after position among his fellow

THE LUMINIST ‘SOUS-BOIS’

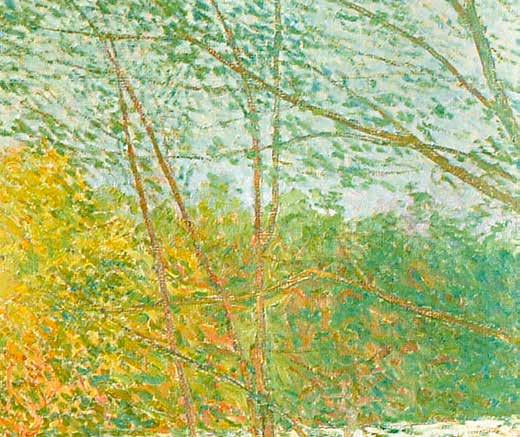

Claus’s search for lifelike scenes led him to limit his field of vision more radically in the 1890s. In Sunny Lane (fig. 42), he approached the herd of animals slightly below eye level; together with the striking cropping, this reinforces the photographic quality of the work. In landscapes of this kind focusing on lanes (which would eventually lead to the “drèves dorées” or ‘sunny lanes’ series), he achieved a quite distinct light e ect, a new “sous-bois” (‘clearing’) genre. In the foliage in particular, Claus used a technique in which the paint is applied in hundreds of stripes and dots placed next to and above each other, which produces a sliding gradation in the light and shadow e ects. The flecks of light whirl like flakes across the canvas; they break through the formal details but do not obstruct the sense of unity, because the whimsical play of shadows has both a constructive and connective e ect. The innovative approach did not escape contemporary commentators. For instance, critic Eugène Georges noted: “A brilliant Claus, Sunny Lane, the fusion of the sunbeams is beautiful, there is an air of cheerfulness, and one can perfectly hear the step of the cows with their heavy hooves.” 113

Of course, the theme was not new – just think of the oeuvre of Max Liebermann (at whose Berliner Secession exhibitions Claus was a welcome guest) or, in Belgium, of Franz Courtens and AdrienJoseph Heymans. Claus would often depict the road between Deinze and Deurle, usually without figures (fig. 56). The village of Astene remained rather underexposed (fig. 45), in contrast to the lane in Bachte-Maria-Leerne and the surroundings of Ooidonk Castle, which he painted several times around 1900 (figs. 57–59), paintings that are midway between the “drèves dorées” and the “façades ensoleillées”. Incidentally, Claus also repeatedly paid attention to Deurle, not coincidentally the village where his friend Cyriel Buysse would later live (more specifically on the Molenberg) (figs. 44 & 126).

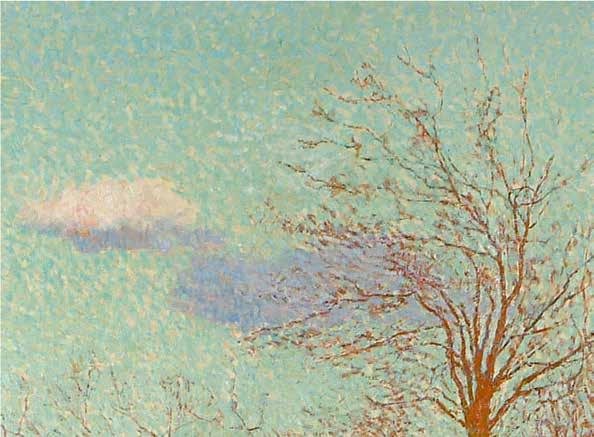

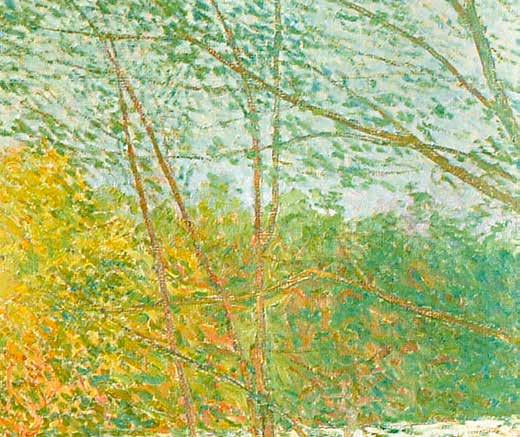

He also, though less frequently, painted the imposing trees surrounding his house, in winter (fig. 99), but especially in between seasons. Sunny Tree (fig. 96) and The Chestnut Tree (fig. 93) are fine examples. Sunny Tree shows one of the rare close-ups he made of natural elements. Rather than make a detailed nature study, he chose to depict the warm glow of a spring sun, the di use, slipping light taking centre stage. The impressive old beech takes shape in short, nervous touches in several gradations of yellows, greens and reds, a colouring that shows the sun gliding across the tree’s surface. It fully illustrates Claus’s luminism, which is seen in the di erentiated brushwork and striking colouristic control, and elicited this lyrical outpouring from the critic duo Marius and Ary Leblond:

A Claus who lovingly studies the giant tree in front of his country house, singing of it with all the lyrical notes of his palette that glows with the colours of sunsets and sunrises, who, in his studies of the trunk, renders the fiery resin, welling up from the flaming centre of the earth… a magnificent work. Just let someone else after him paint the Tree, just as Michelet wrote L’Oiseau [‘The Bird’], writing the history of the tree, species upon species, on the scale of frescoes, the monograph of the chestnut, the monograph of the poplar, that of the pine and the red beech, that of the Assyrian cedar, that of the African baobab, that of the American sequoia, that of the tropical benzoin tree. These series of tableaux will establish a great museum of painting. Natural history painting is as legitimate a genre as history painting, and it will be superior to it to the extent that the history of nature is superior to that of battles.163

Sunny Tree has also been discussed in the context of intimist symbolism, the emphasis being on “the delicacy of line and an empathy with living forms”. 164 A smaller version with this theme is known to have been created a year earlier, in April 1899 (fig. 97). The same beech features a less classical profile, is more suggestive, rougher and closer to nature. At the same time, in the later version there is a certain abstraction to the whimsical interplay of lines, which is less apparent in the first. Both versions show that Claus had not yet renounced the tried-and-tested formula of copies, begun in the 1880s. Always following market demand (and perhaps also the purse of the interested party), he would reduce or enlarge the original, down to the smallest detail.

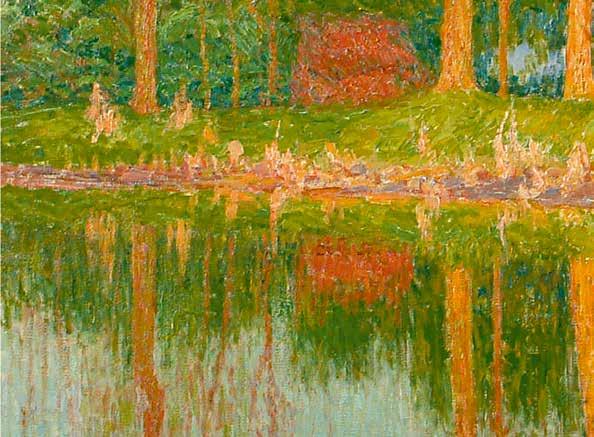

The more panoramic landscape of The Chestnut Tree appears also as a dreamscape, although here other elements play a leading role. In this work, painted (or conceived) on the other side of the Lys, with the garden wall of Villa Sunshine on the right, the bank is reflected in the gently flowing water of the Lys; the landscape is doubled, as it were, via the slightly fading reflection. This dreamy image forms a well-considered whole, Claus imposing a strict composition by placing the impressive chestnut tree to the left of centre and compensating the slight imbalance with the repoussoir of the leaning branches to the right. Nature has just awakened and is being stimulated by the

93. Emile Claus, The Chestnut Tree, May 1906 Oil on canvas, 135 × 144 cm La

compositions. The number of preparatory, wet-in-wet and on-thespot oil studies, or drawings sketched rapidly with a usually oily pencil, suggests that photographs only played a partial role in this whole process. Based on a conversation with Claus, Edmond-Louis De Taeye wrote about his working method during the early 1890s:

To begin with, for fear of spoiling their purity, he will only superpose two colours when the first is perfectly dry. Then he will proceed confidently, following a strict method that consists in placing a series of carefully selected chromatic reference points on his canvas and connecting the space between them little by little with intermediate coloured dots, so that the pictorial notation of the observed piece of nature is established clearly and accurately, precisely and mathematically.191

The argument is of course related to De Taeye’s book published at the time (1894); certainly after 1906-07, Claus’s technique would become increasingly free, even in large-format paintings.

AN OFFICIAL ARTIST

By 1900, Claus was one of Belgium’s most celebrated artists, including outside Belgium. His work led to this success, of course, but he was also a skilled networker and self-promoter. Ten years earlier, Claus’s swerve towards luminism had confused his buying public; for a while, sales of his work declined.192 Antwerp newspapers such as Het Handelsblad, which had previously praised him to the skies, suddenly reproached him for following “Parijzer kladderij naar [na] van de zesde klasse” (‘sixth-grade daubs from Paris’).193 The situation reversed following remarkable expressions of support from critics such as Octave Maus, Edmond Picard and Émile Verhaeren, and government o cials such as Ernest Verlant and Paul Lambotte, with appreciation for the ‘new’ Claus often leading to friendships.194 The Belgian state played a key role in this turnaround. Between 1891 and 1912, the government subsidised purchases of Claus’s work every year or so. For example, it helped in the purchase of The Skaters (fig. 32) for Ghent and Lifting the Traps (fig. 43) for the Brussels municipality of Ixelles. For the central museum in Brussels (today’s RMFAB), it acquired Sunny Lane (fig. 42) and The Flax Harvest (fig. 70). Purchases also served to adorn o cial buildings, for example Villa Sunshine (fig. 110, now at MSK Ghent) or Evening in June (fig. 102). Sometimes the purchase did not take place without a struggle, as in the case of Sunny Day (fig. 55). After the Brussels museum commission refused the painting, friends of Claus, including Maus and Lambotte, reacted by taking up their pens (the latter as a civil servant involved in the transaction!); Picard, a senator for the Belgian Workers’ Party whose Maison d’Art had organised an important exhibition by Claus in 1898, even raised the matter in Parliament. The purchase involved a ‘Belgian compromise’; as will be shown later, the work ended up not in the national museum, but in a ‘provincial’ institution (as fine arts museums outside Brussels were