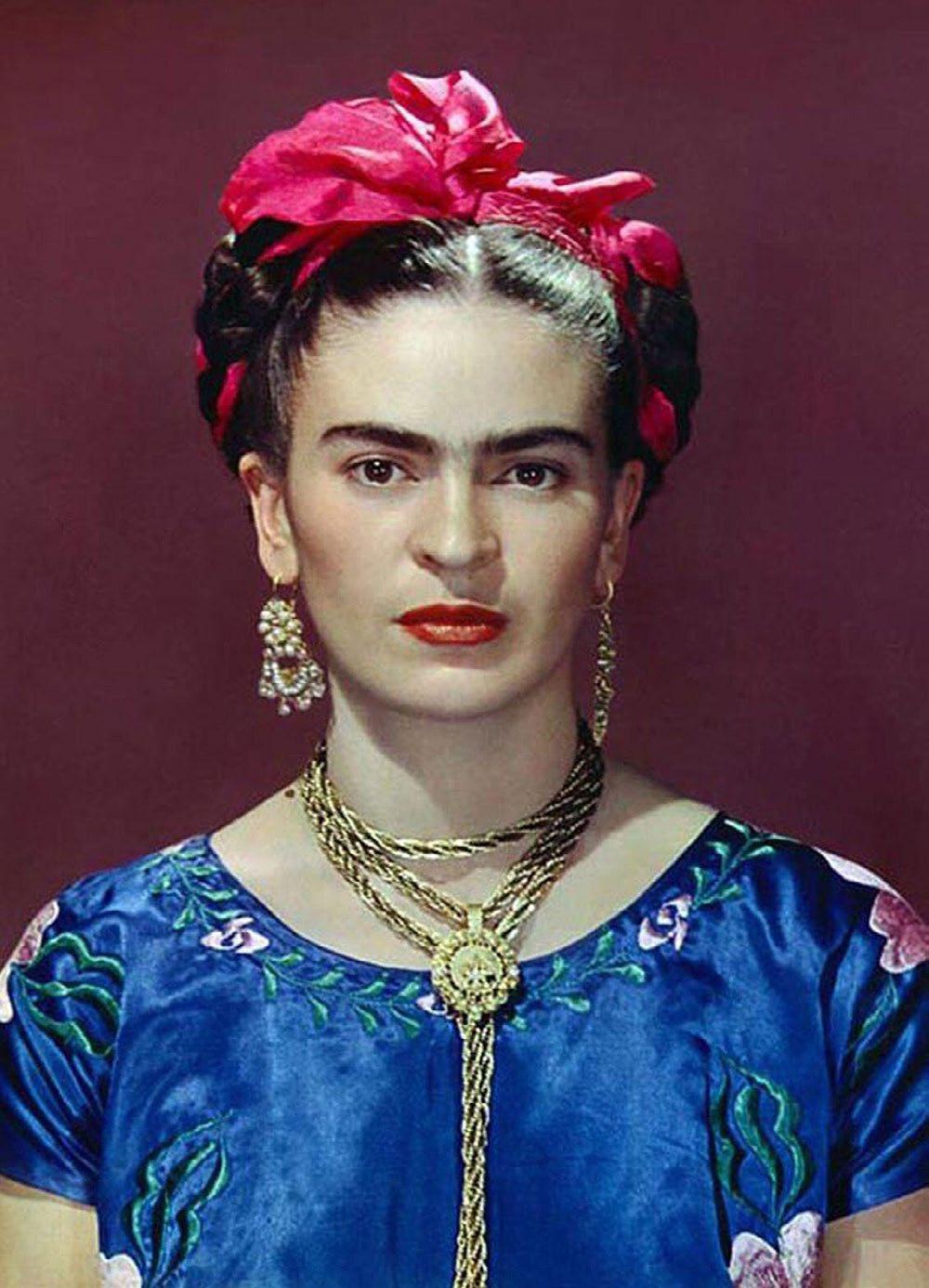

As regal as an Aztec goddess, Frida Kahlo had an exciting and provocative personality. She did not meet the traditional standards of beauty, yet she was a sensational figure. Her black eyebrows formed a single arch on her forehead, and over her mouth there was a shadow of down. But more than any other thing, it was her eyes that made her so magnetic. They were dark and intense, and devoured the gaze of those who observed her. Today, that face has become a global icon, much like that of the Gioconda, better known as Mona Lisa. For that matter, Frida worked all her life creating her image, ending up transforming her being “different” into being “special.” Perhaps this is why she has always been so popular. This was in the early twentieth century, and yet the message she launched is so extraordinarily topical. She understood that one’s identity is fluid and that you can choose it and create it, regardless of your gender, origins, conventions, and sexual orientation.

She taught the world that physical imperfections should not be hidden but actually valued and enhanced until they become a sign of strength and emancipation. All those who have been struck by illness, whoever has ended up in the abyss of depression, and those who have been victims of suffering and pain, have had the sensation that Frida Kahlo is speaking directly to them. Rebellious and contradictory, she is an example of passion and courage that has never failed to fascinate new generations. And yet, apart from her universal fame, how many people really know the person behind that face and her actual life story? Her dramatic trials and tribulations, and even her splendid works, have often counted less than the symbol into which she was transformed.

This book is an invitation to get to know the true Frida, to discover the woman hidden behind the myth. She lived only forty-seven years, but her biography is eventful and soul-stirring, closely connected to the history of Mexico.

Self-Portrait Dedicated to Dr. Eloesser, 1940. This is one of Frida’s most famous paintings, in which she depicts herself with flowers in her hair, a necklace of spines, and an earring in the shape of a hand that Picasso gave to her.

When she was fifteen, Frida attended the National Preparatory School, one of the best scholastic institutions in Mexico. She was an excellent student and had passed the admission examinations brilliantly. She suddenly found herself far from the protected calm and shelter of her neighborhood and right in the middle of the political ferment of Mexico City. After centuries of colonialism, the decades-long dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz had transformed the country into an oligarchy of foreign firms that domineered the haciendas, where the peasants, deprived of all rights and dignity, were increasingly tired and demoralized. Their rage exploded like a bomb, and the initial protest soon turned into a revolution that was destined to bathe Mexico in blood for over a decade. The campesinos demanded that the land be given back to the peasants, led by such legendary figures as Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, who were eventually assassinated and became heroes in the people’s collective imagination. Frida was only a child, but the recollection of those tumultuous years was indelibly impressed on her mind. “I was seven years old when the ‘tragic ten days’ took place. I witnessed with my own eyes Zapata’s peasants’ battle against the Carrancistas,” she would write in her diary. That political and social turmoil had also given rise to a new image of women that was reflected in politics with new laws sanctioning the right to divorce and the urgent need for universal suffrage. Frida had grown up immersed in that climate, absorbing the idea of the “woman-warrior,” who wore men’s clothing and fought for the people. Just like them, she wanted to defend freedom and was ready to fight with her colors and brushes, the weapons that fate had placed in her hands.

However, at that time, her artistic calling was still far off in the future, as she was then dreaming of becoming a physician. The National Preparatory School would be an ideal

springboard for her ambitions. Girls had been admitted to the school for some time, but they were still few in number. That year, Frida was one of the 32 girls admitted out of a total of 2,000 students, and she did not like the idea of belonging to a minority. She considered her female classmates too frivolous for her taste, and unlike her, they were rather indifferent to politics. That year, she began to wear a communist uniform, entering the classroom wearing a red shirt with a star embroidered on it, a foulard around her neck, a knee-length skirt, and flat shoes. She felt perfectly at ease in the fervent academic atmosphere and soon decided to join the Cachuchas student movement, which was animated by a group of young people destined to become the most influential intellectual elite in Mexico City. The name they had chosen derived from a type of wool beret with a visor that they placed forward over their forehead, worn as a sign of their rejection of the rigorous bourgeois clothing code that required students to wear a straw hat. They were rebels and agitators who thrived on biting comments and camaraderie without hierarchy that negated differences of gender, which Frida totally embraced, learning to have friendships with men and women alike, without distinctions. The group met to exchange views regarding politics, philosophy, and literature in fiery discussions full of enthusiasm and curiosity. But their life did not consist only of political commitment; there was also space for devil-may-care behavior and their antics were legendary. One time they entered the classroom riding a donkey, and they often skipped the lessons whose teachers they considered boring or even unqualified. And they also targeted the painters who in that period had been invited by the government to fresco the walls of the school in order to promote national pride. One of these painters had a particularly striking impact on Frida’s imagination.

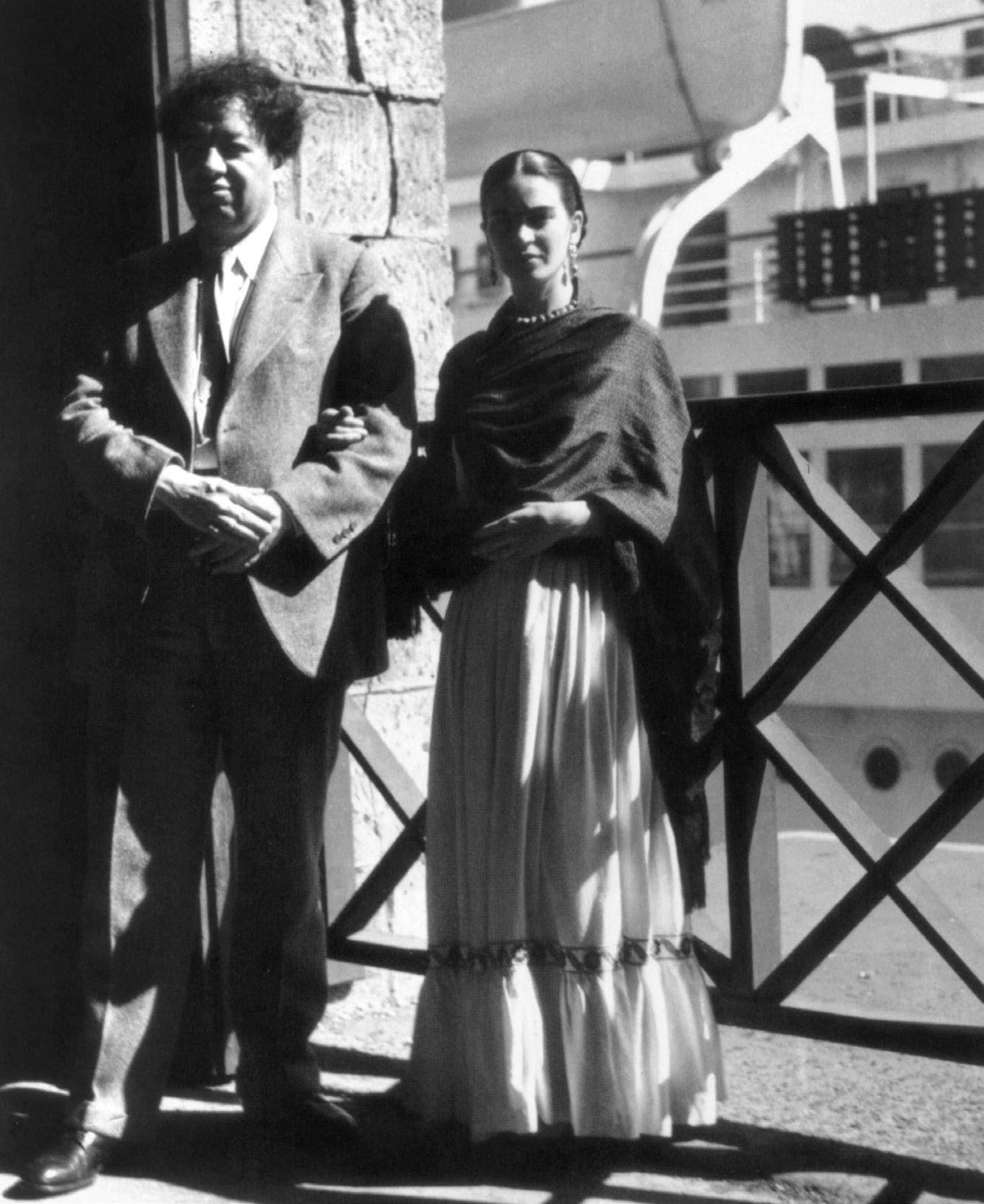

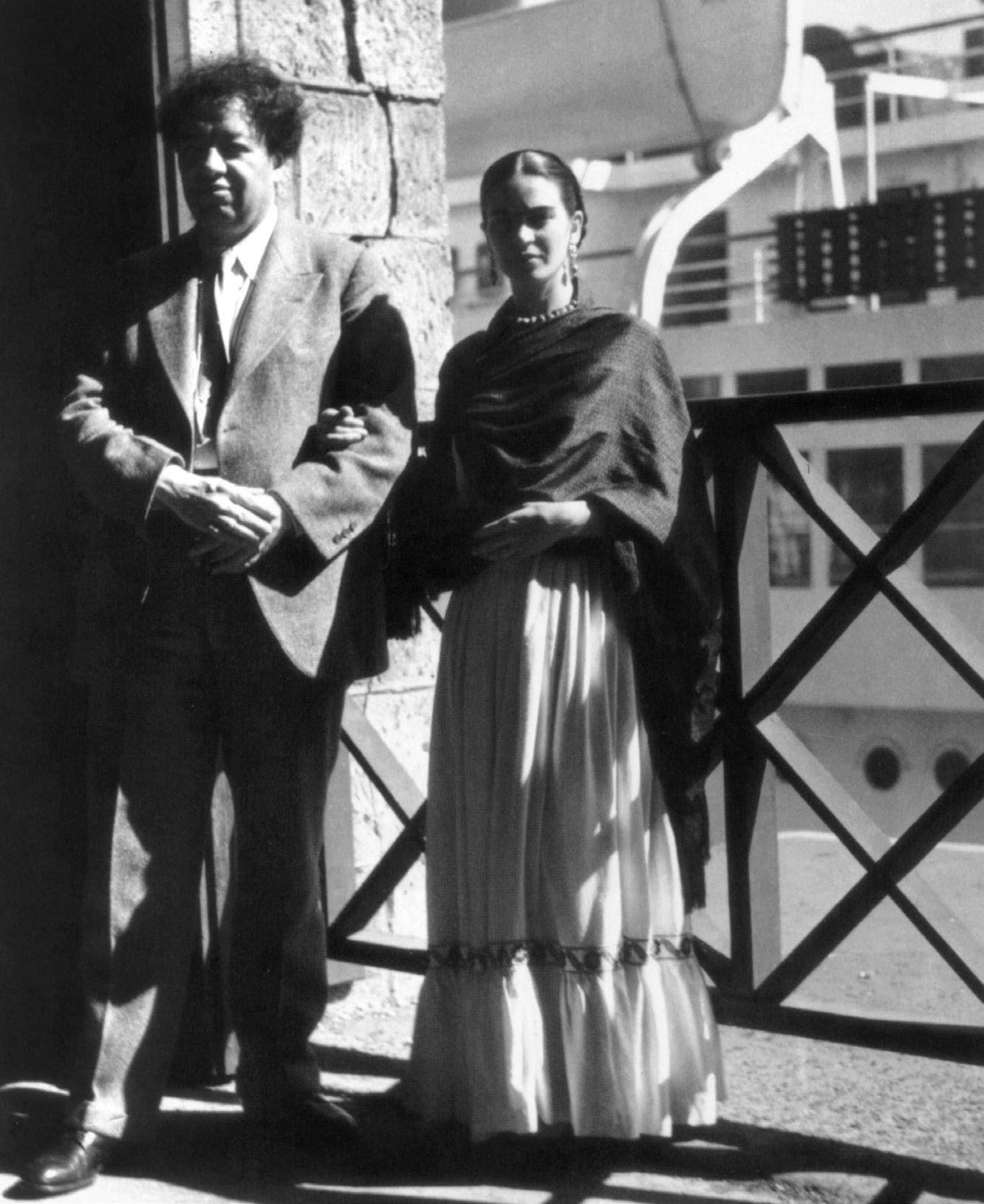

It was precisely during one of these get-togethers, marked by songs and rivers of tequila, that Frida met Diego Rivera again. A few days later, she asked him to give his opinion of her paintings. Did she have talent? This was the question for which she so desperately wanted an answer. Diego encouraged her and urged her to experiment not only with brushes but also with photography, suggesting she should let herself be inspired by Tina Modotti’s abstract style. “I want to photograph what I see, sincerely, directly, without tricks, and I think this can be my contribution to a better world,” Tina stated, expressing a thought that Frida also shared deeply. Their friendship intrigued Diego. He was fascinated by the special bond between the two, so much so that he portrayed them together in Ballad of the Revolution, the mural he was painting on the third floor of the Ministry of Education. In that work, Tina is depicted in profile on one side, while Frida dominates the middle of the scene, wearing a red work shirt with a star on her chest and distributing weapons to the revolutionaries. That cheeky twenty-year-old who drank tequila and always had a cigarette in her hand had already penetrated Diego’s heart. They became comrades and lovers as they went down the streets together with upraised fists. This scene was immortalized by anonymous reporters as well as by Tina Modotti, who photographed them marching in a crowd during a demonstration—which was her very first portrait of them together. Frida and Diego got married a few months later, in August 1929.

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo photographed by Tina Modotti while participating in a May 1 parade in Mexico City in 1929.

“Beauty and ugliness are a mirage, because others end up seeing what’s inside us.”

Shortly afterward, the couple was traveling once again. Diego had accepted an invitation from the New York Museum of Modern Art, which had just been inaugurated, to have a retrospective show held there. They arrived on a transatlantic ship in November 1931 right in front of the skyscrapers of Manhattan and were met by journalists and a crowd of admirers who had come to welcome the master of muralism. They stayed at the Barbizon Hotel, in a room with a view of the yellowed winter trees in Central Park, which Frida gazed at as if it were a mirage in the midst of all that cement. The evening of

December 22, all the elite of New York City went to the inauguration of Diego’s exhibition. In the midst of that elegant crowd, so snazzy in its brilliant, stylish attire, Frida stood out like a wildflower in her flashy Mexican dress. “The gringas really like me a lot,” she wrote in a letter to her mother, “and they take notice of all the dresses and rebozos I brought with me and gape at my jade necklaces.” The American newspapers also became aware of her, and the articles concerning Diego never failed to refer to his exotic wife and her flamboyant clothes, which in fact caught everyone’s eyes.

Above: Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo at an exhibition of Lionel Reiss’s works in New York.

The origin of this progressive transformation is to be found in the painting Memory, in which her hair is cut very short and she is wearing a short brown leather jacket over a white dress, her chest transfixed by the rod that had pierced her pelvis in the streetcar accident. The school uniform she wore that day is hanging at her right, while at left is the pre-Columbian costume that represents her new identity. But Frida’s obsession with self-representation is not revealed only in her self-portraits. The nostalgia for her childhood and the trauma of abortion and miscarriage is to be seen in her paintings of children, which she depicted with her own face. This osmosis is also repeated in the portrait of one of her favorite animals, the spider monkey Fulang-Chang, which poses with her in a self-portrait in which her dark hair mingles with the primate’s fur in a reference to symbologies that evince her wildest side. She even considered still lifes a sort of self-portrait. The fruit in the canvas is split in two and open, the juice as dense as blood—a reference to her wounds. From that moment on, living and painting were one and the same for her. Frida lived in her canvases.

Memory (1937): Frida is portrayed with a European hairdo and continental clothing, between a schoolgirl uniform and a traditional Mexican costume.

“I am not sick; I am broken, destroyed. But I am happy to be alive as long as I can paint.”

The handwritten annotations with their full, rounded, and brilliantly colored letters with bright colors alternate with messages of love for Diego, declarations of political commitment, and thoughts concerning death. But they also contain bizarre drawings executed with colored inks, pencils, and watercolors with extravagant hues, as well as many self-portraits. Next to the drawings, she often wrote poetic phrases, reflections on her life and her perception of herself. “The one who gave birth to herself, who wrote the most beautiful poem of her life,” one of them states.

Around the mid-1940s, the high-spirited Frida became a sick woman forced to stay home, immobile in her bed. In the painting The Dream, she reveals her most profound fears, depicting herself resting on her bed with a skeleton on the canopy above her. Her health continued to worsen, as did the pain in her spinal cord and her foot. She was unable to work, and even the slightest movements exhausted her. She had to have transfusions and underwent treatment with various medicines, but she ate hardly at all and lost weight to an alarming degree.

This photo by Bernard Silberstein portrays Frida next to her canopied bed, which is crowned with a skeleton.