text

JEANS

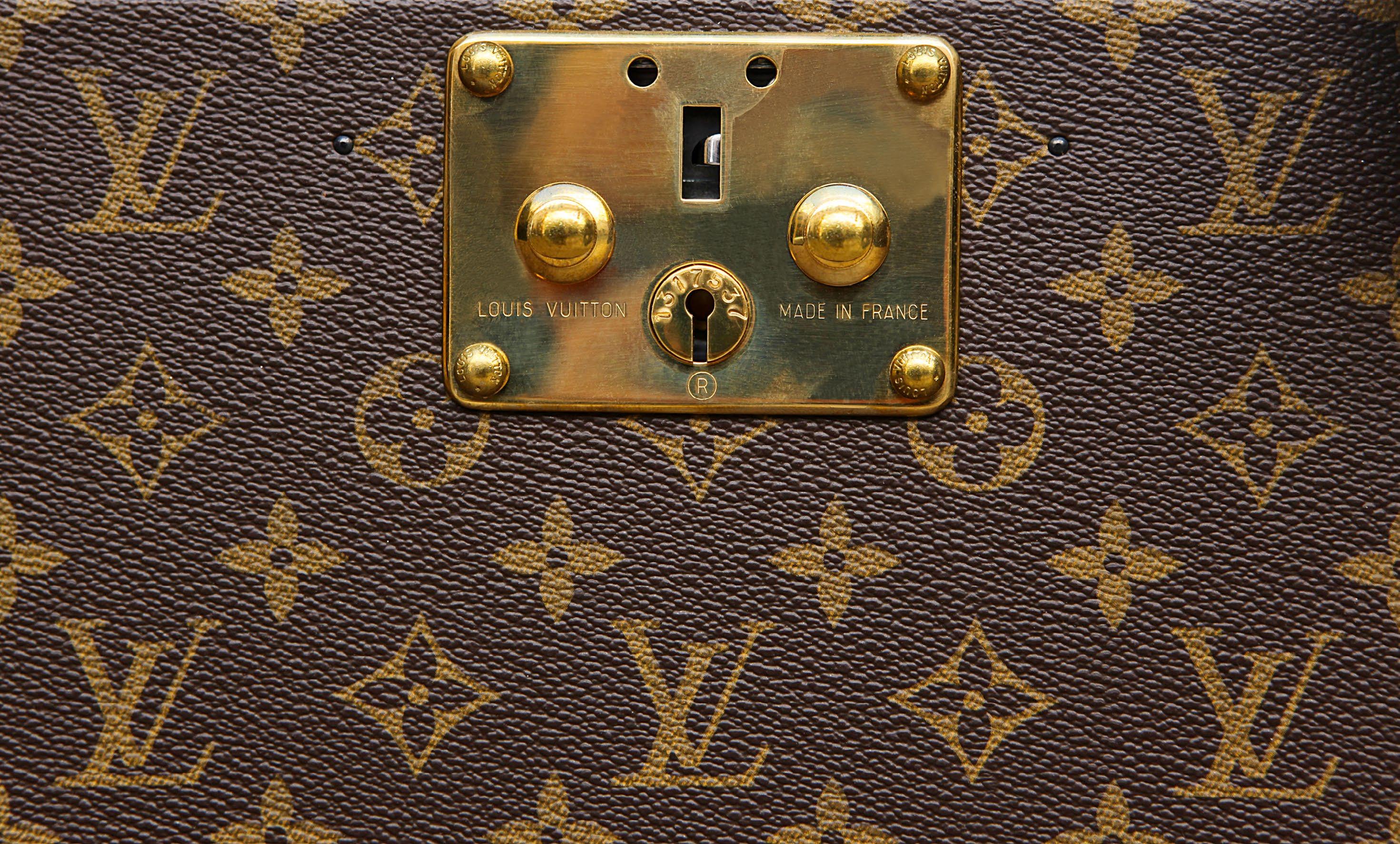

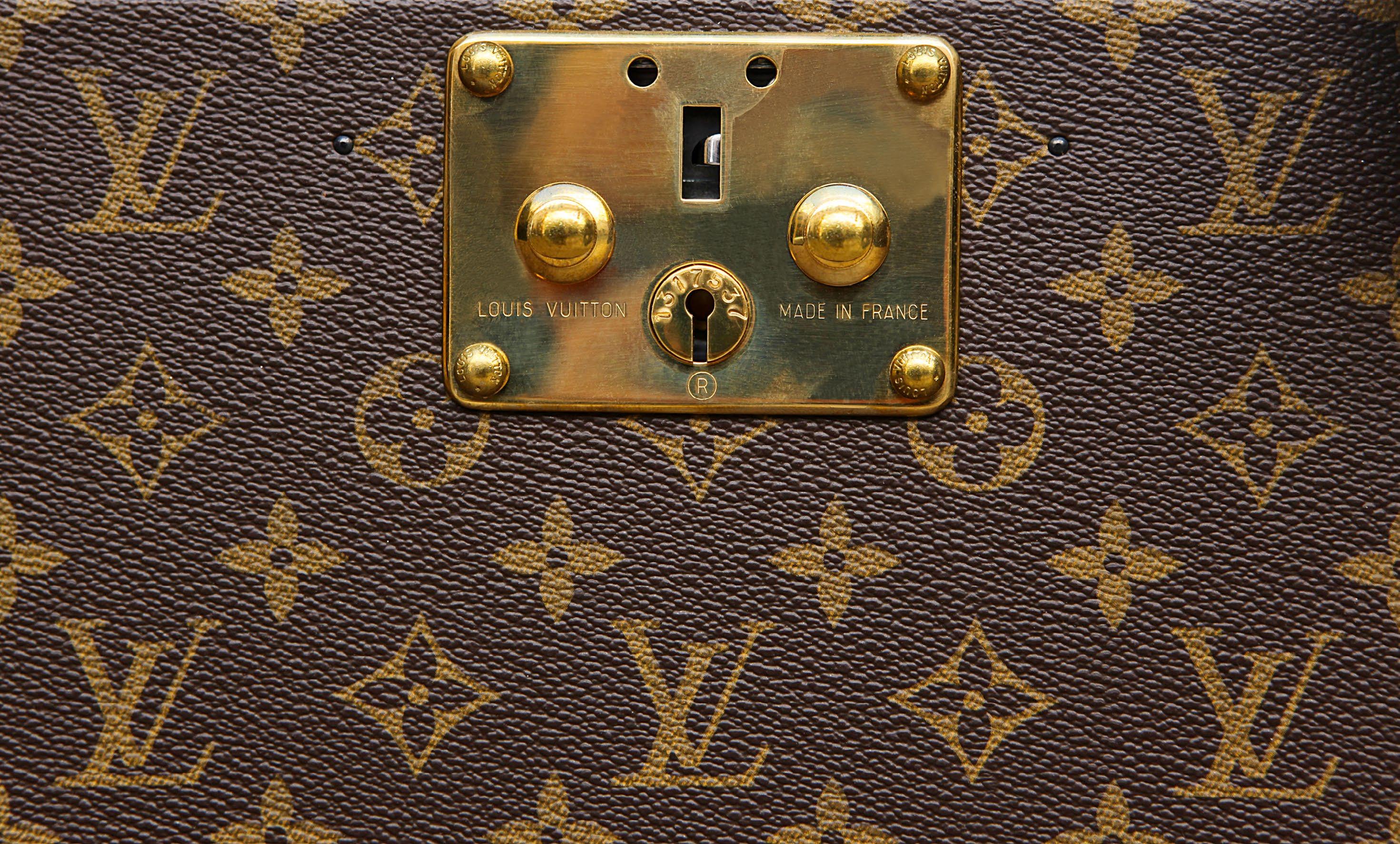

LOUIS VUITTON

THE TRENCH COAT

BORSALINO

THE MARINIÈRE

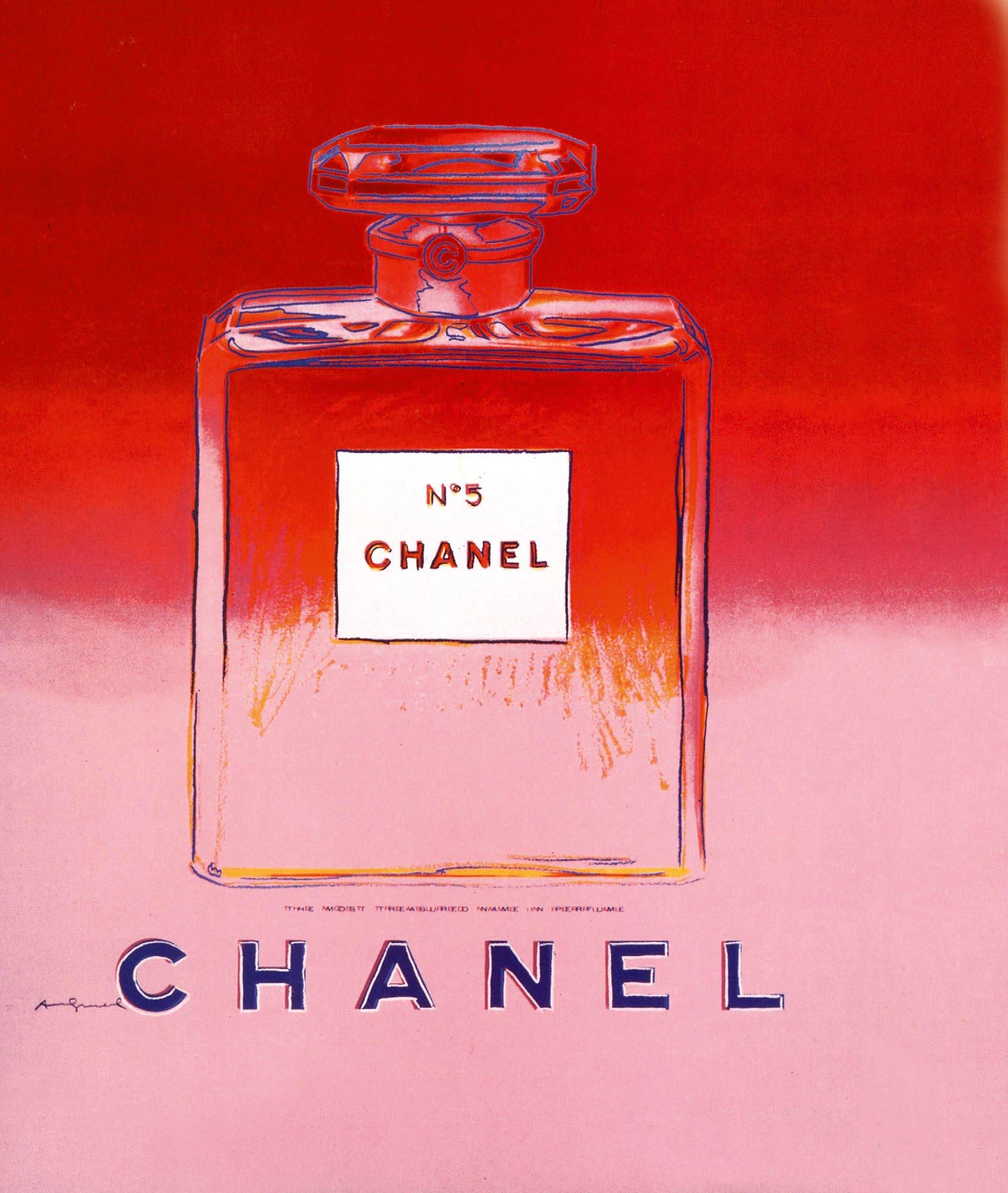

CHANEL N°5

LACOSTE

HERMÈS SCARVES

THE

RAY-BAN &

KELLY

LITTLE BLACK DRESS

THE JACKIE BAG

THE STILETTO

text

JEANS

LOUIS VUITTON

THE TRENCH COAT

BORSALINO

THE MARINIÈRE

CHANEL N°5

LACOSTE

HERMÈS SCARVES

THE

RAY-BAN &

KELLY

LITTLE BLACK DRESS

THE JACKIE BAG

THE STILETTO

Levi’s. From mines to catwalks.

Style

“on the road.”

Dance classes on city streets.

We are all quite accustomed to the theatrical installations set up by Maison Chanel for its fashion shows. Flamboyant, bombastic backdrops animated by the movements of elegant creatures forged by the pencil of Maison’s creative director, Karl Lagerfeld. These are displays of grandeur that Chanel can most certainly brag about. But one more than all others deserves a special place in our collective memory. In January 2008, in the already enchanting setting of the Grand Palais in Paris, King Karl presented Chanel’s 2008 spring/summer haute couture collection. Before the show began, journalists, buyers, and celebrities were treated to a grandiose spectacle. An enormous jacket no less that 25 meters high stood precisely under the building’s glass dome. It was grey, as if it were made of raw cement, perfect in its proportions and details, absolutely identical to an authentic Chanel jacket. The models–beginning with Sasha Pivovarova–emerged from the slightly open hem of the gigantic jacket, received their portion of admiration and applause, and went back where they had come from, into that magical darkness of the world of fashion unknown to common mortals. The jacket was presented like a totem, like the alpha and omega of the spirit of Chanel, the imaginary place where everything begins and everything ends.

“Every stylist dreams of inventing the Chanel jacket,” Lagerfeld admitted. “It is the equivalent of jeans and the T-shirt. Something that is at once neutral, feminine and masculine, as well as the symbol of a timeless fashion.” The talented designer’s metaphor is as accurate as it is simple. The very essence of the Chanel style, its DNA, its entire story, is contained in the iconic and unmistakable tailleur jacket.

Yes, because the entire creative course of Chanel, with its double C, vacillates between the apparently incompatible extremes that Coco was able to fuse as if by magic: style and functionality, taste and practicability. Her outfit is a prime example of this synthesis. The invention of the woman’s suit consisting of a jacket and skirt is attributed to English tailor John Redfern, who supposedly created it way back in 1885. But Coco Chanel deserves full credit and the highest esteem for having revived it in a totally new way in the 1920s. She did away with heavy cloth and stiff lining, which, instead of making women comfortable, only ended up making them feel more ungainly since they were forced to walk with limited and tiring movements. So she opted for jersey fabric, which was “borrowed” from men’s underwear and proved to be ideal for making soft and flowing items

147 1959: a model poses in front of the Paris Chanel boutique.

149 A detail of the light blue tailleur worn by Diana, Princess of Wales, at her son William’s confirmation in 1997.

The double C pattern of the buttons is the Chanel “signature.”

The pride and joy of Italian creativity, inventiveness and excellence are the Persol sunglasses. Behind the success of this world-famous brand stands an entrepreneur from Piedmont, Italy, who was a photographer and owner of Berry’s opticians, which in 1917, in a courtyard on Via Caboto in Turin, began to make avant-garde sunglasses expressly for early aviators and intrepid sports pilots. The Protector model, which had a rubber frame and round lens, was used by the Italian armed forces and air force. Among the most enthusiastic fans of the Piedmontese label was Gabriele D’Annunzio, who wore them–not as a poet but as a major–during an historic flight over Vienna in 1918, during which he dropped thousands of patriotic leaflets. But it was in 1938 that the Persol trademark proper was created. As its name suggests (it is the abbreviation of per il sole, or “for the sun”), it was designed to protect wearers from the sun’s rays. The period was marked by two technical innovations that will always be proudly worn on the chest of the Persol label much like a soldier’s medals. The first is Meflecto, a futuristic system that introduced flexible, and virtually unbreakable, frame wings. The second is the iconic Freccia or arrow–the hinge on the frame wing decorated with an arrow whose shape drew inspiration from ancient warriors’ swords–which was to become one of the unmistakable (and frequently copied) details of the Persol style.

But the turning point for the small company was 1957 thanks to the 649 model. Conceived to help tram drivers in Turin, who were at the mercy of the wind, air, and dust because their drivers’ seats were still exposed to the elements, the Persol 649, with its unmistakable yellow-brownish lens, covered a large area and protected both the eyes and part of the face from sunlight, and at the same time added a touch of Latin charm and glamor. That is the reason why, among a host of international stars who have worn them, from Greta Garbo to Steve McQueen, the most memorable is Marcello Mastroianni in Divorce Italian Style (1961).

WS whitestarTM is a trademark property of White Star s.r.l. © 2013, 2025 White Star s.r.l. Piazzale Luigi Cadorna, 6 20123 Milan, Italy www.whitestar.it

Translation: Richard Pierce

Revised edition

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. ISBN 978-88-544-2126-4