BEAMS ENTANGLED

MORETTI CRUCIVERBALIST

Etgar

MID-AFTERNOON

Aridjis

CONVERSATION

Durbin and Simon Moretti

MONSIEUR PICASSO

Andrew Durbin

Can I ask you about the name of this book, Abacus ?

Simon Moretti

It took me a long time to find a suitable title. I didn’t want something too descriptive – something that would anchor the project to a specific concept – but I felt I had to name it. Abacus fit the bill for a book that reflects on 10 years of my collage practice. I liked its various meanings; the most wellknown, of course, is the early numerical adding machine. But I was interested in its Greek etymology – it comes from the word abax , meaning a square tablet covered in dust that would be used for communicating thought-images effectively. In classical architecture, the word describes a flat slab that forms the uppermost member or division of the capital of a column, its main function being to provide a large supporting surface where the top of the column meets the capital.

Andrew Durbin

How does a collage begin for you?

Simon Moretti

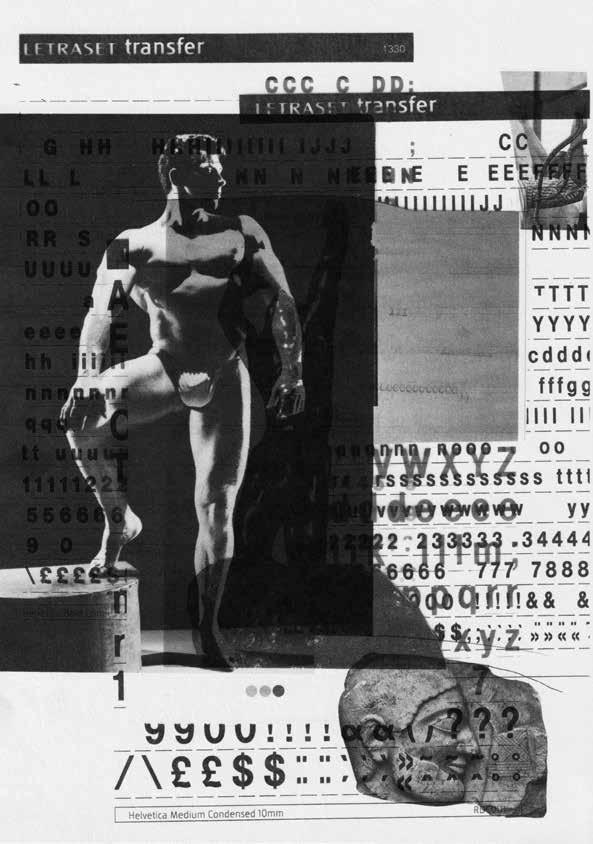

I try to get away from something contrived or pre-planned. I deal with the material and see where it takes me. I collect old books, magazines, newspapers, then cut up images and keep them in archive boxes. The images are not organised or categorised in any way because it’s very important for me to get away from their pre-existing life. Then there are days where I explore the material, and something starts to happen on the studio table and somehow connections are made. The thread that links them all is the fact that it’s an instinctive operation. That doesn’t mean there isn’t a system; there is a system, it’s another system related to the unconscious. When you look back, you see recurring themes, and in a way the exercise of making this book and juxtaposing works from different times is a similar operation.

I came to collage through a slightly different route from most people. Years ago, I made an ephemeral performanceinstallation at Platform – a project space in London that was active in the 1990s – titled Interlude 1990 . I was in the gallery space for six hours, and I arranged and rearranged a variety of found objects into assemblages or collages. Later, I produced a series of collaborative installations, like Spring/Summer (2005) at Program, London, and Expo 21: Strategies of Display (2004) at the Mead Gallery in Coventry, where I hosted other artists as guests in my work. So, for example, I would make a floor piece and then I would arrange other artists’ work on it, or I would make a wall drawing and have other artists’ work in front of it. So, early on, I was already engaging with collaging in space before I turned to paper.

Andrew Durbin

Collage as practice – not necessarily just a practice of collage.

Simon Moretti

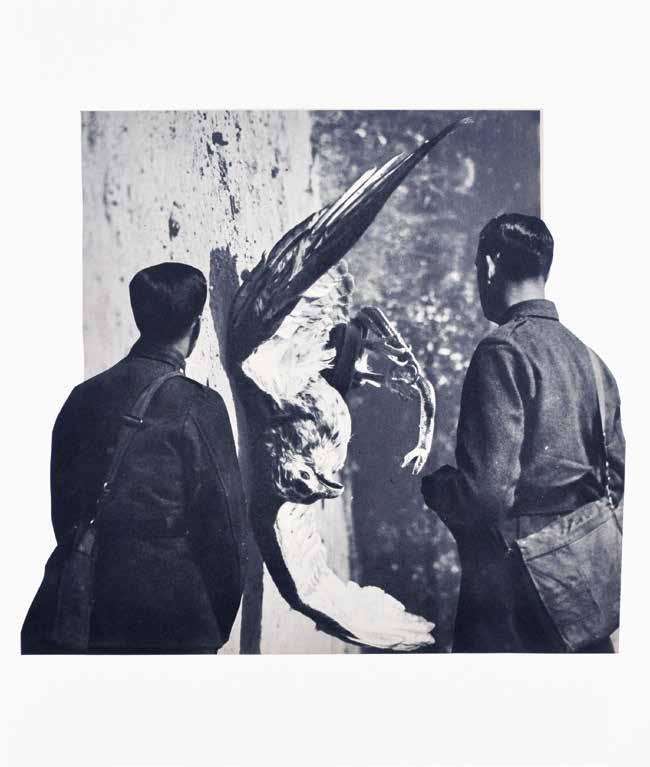

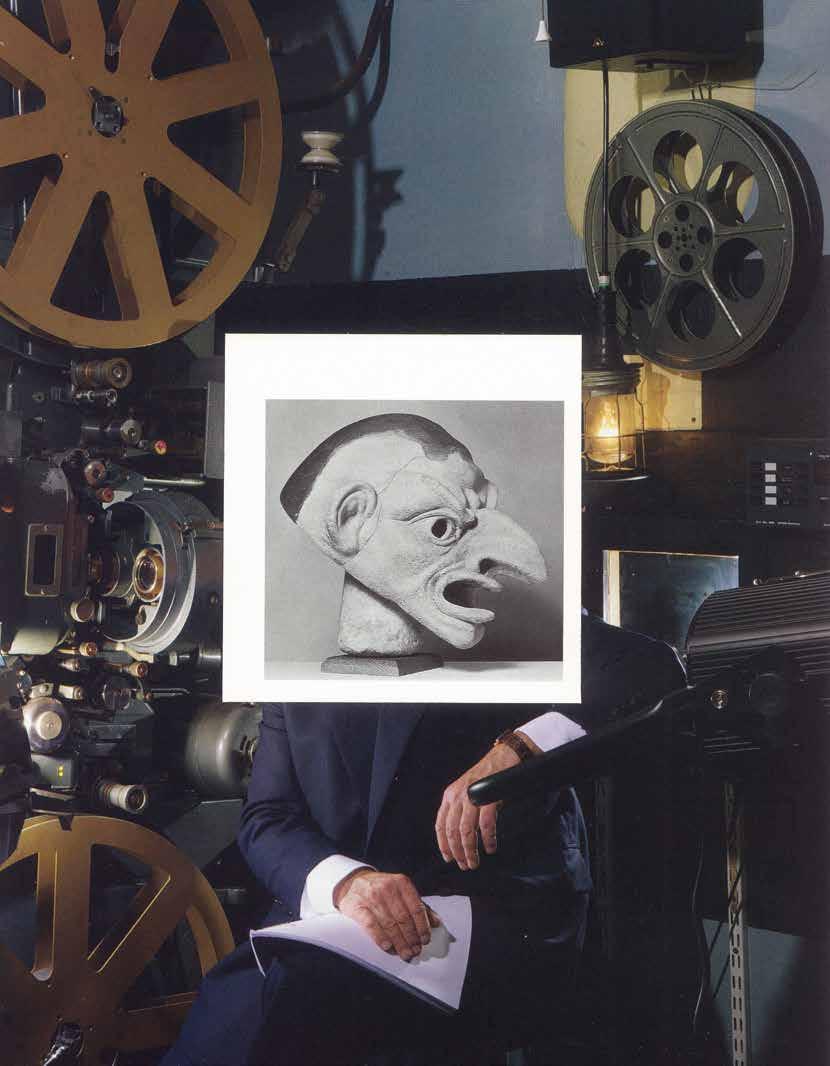

Yes, the way I’ve been making books and exhibitions is the same – they are all collages, in their own way. The difference is, I’m including other people’s artworks and not only found images from magazines. In the works on paper I include other people’s images, of course, and in the beginning I was very interested in bringing together various photographers from different times and different qualities of image. Later, I began to introduce found graphic elements, such as the crossword puzzles and Sudoku, fragment of texts. Most recently, I appropriated images of paintings from modernist artists – Pablo Picasso, Mark Rothko.

Andrew Durbin

What about the relationship between modernism and queerness? The story of early twentieth-century art is often written at the exclusion of queer lives. We always see Marcel Duchamp seated at the chessboard, never dressed as Rrose Sélavy. But your collage sutures Picasso, Rothko and others with an explicit – almost pornographic – queerness that might otherwise have been left out. To me, you’re executing a kind of revenge on the macho, straight guys of modernism.

Simon Moretti Definitely. In terms of the gay pin-ups you’re referring to, I am giving visibility to these queer bodies and aesthetics by including them literally within icons of modernism. In the past, I used images of more classical sculpture – the classical body, the ritual of desire, the emotive poses in Rodin’s sculptures. In the most recent series, with the Picasso or Rothko paintings, I realised that there was something interesting about this interference – obstructing modernism as a way of becoming part of that history, becoming visible within it. I am ambivalent about Picasso, and so this series was also a way of reconciling my admiration for his artistic style with my misgivings about his very public machismo.