Harrogate, York and Leeds also acted as venues before the Yorkshire Union of Artists settled on the coast in Whitby for a period of four years (1894–98).

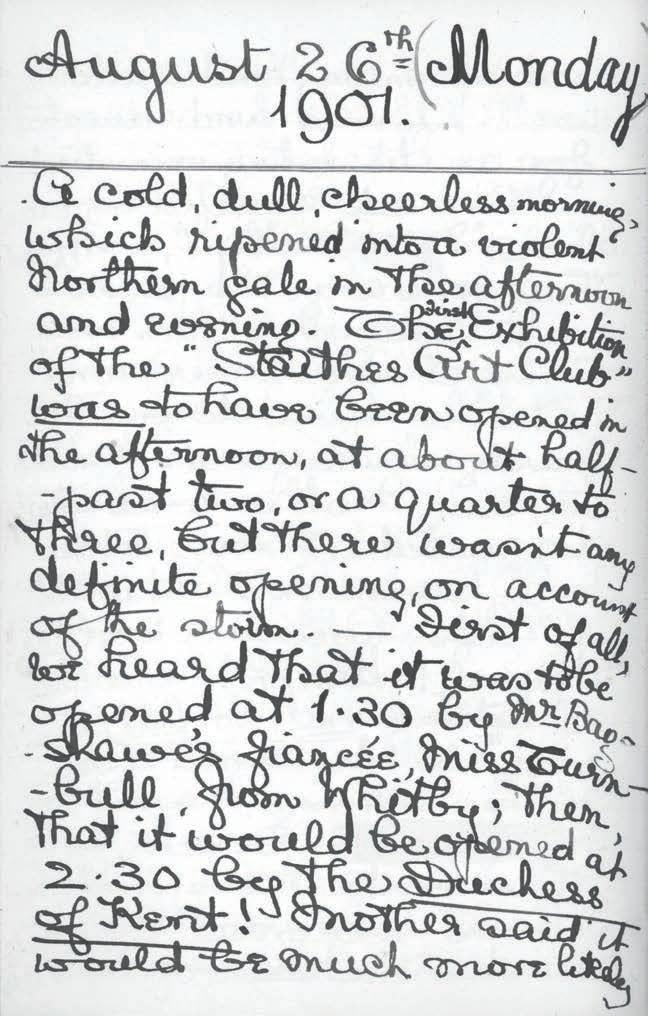

This seems to have coincided with what is acknowledged to be the beginning of the most intense period of activity in Staithes and the surrounding area. After the Union show moved away – albeit with a brief return in 1900 to Scarborough – artists who either lived or regularly worked in the area might have felt the absence of an outlet for their work. From the inaugural Staithes exhibition, its members seem then to have focused their attention away from the Union, until the Art Club and the Union came together in 1905 with, as has been noted, exhibited works making their way from Whitby to Hull in 1904.

As with other colonies there seem to have been almost no `local’ artists who were members of the Club. However, Edward Anderson should probably be considered the exception that proves the rule. He was born in Whitby to a family whose jet business turned into a fine art business and in whose gallery the fourth Staithes Club Art Exhibition was held. Both the Anderson Gallery and its `extension’, The Rembrandt, which opened in 1905, not only represented Staithes Club members (from 1904), but also regularly displayed works by a range of painters who worked locally.

Today their work hangs alongside that of the Staithes Art Club in the Pannett Gallery in Whitby, established as a gift to the town by the industrialist after whom it is named.

Azure Mead, 1894

101.5 x 148 cm Bonhams

‘On both sides of us is a precipitous line of coast, with bristling cliffs, washed by a boiling surf in some places, and in others fringed with a narrow beach, on which gigantic moss-strewn bowlders [sic] are piled. The sea itself melts in the extreme horizon....the wind strikes with unrestrained violence....[it is a] high white coast.....with the German Ocean chafing against it.’

So reads a description of the North-East Coast in Harper’s Magazine of 1884 as Fred Jackson and fellow artists arrived in Runswick Bay, just south of Staithes. It goes on to detail in slightly less daunting but no less pictorial fashion the quaintness and historic nature of the towns, the ‘paintable’ aspect of the villages and the fact that ‘those among the dales of the north-east coast cling to the belief in witchcraft even yet’.

These qualities were seemingly the object of popular artistic endeavour as, during the second half of the nineteenth century, knots of artists established themselves in rural communities across France and then the rest of Europe. Training in the art schools of Paris, in particular, they fanned out during their vacations to identify places and subjects worthy of their new ambitions. These ambitions were a truth to nature and consequently painting en plein air; they followed the example of early pioneers such as Jean-Francois Millet in the forests at Fontainebleau.

Increasingly the artists sought out the hinterland of Brittany for its wildness, as well as its coasts and villages against which to test themselves. It was noted that ‘The rock-bound coast of Brittany offers endless variety of colour and form to the tourist, painter or zoologist.’

However, it was not only the rugged beauty of the landscape that held such a powerful attraction. The way of life of its inhabitants, marked by a picturesque religiosity, was also striking, as the Magazine of Art in 1880 observed:

The remains of ancient art are chiefly to be found in the distant or obscure villages – not reached without much trouble, and accessible only by foot or char-road.....the study of any [calvary] is instructive, showing how the Christian forms of art and local superstition are constantly blended.

This language in part derived, like the boatbuilding tradition and associated trading in materials such as tar and timber from the Baltic and Scandinavia, the literary remnants of the Vikings in the names and language of the coast – the name of Staithes itself, the dialect that persisted in the village, geographical terms such as wyke and on into specialised terms of the fishermen and their gear – kess bowls, gog sticks, haaf pieces and smouts,

trip from the coasts of Brittany and Normandy. So it seems surprising that Laura and Harold Knight’s departure from Staithes in 1907 has been linked to their `discovery’ of Cornwall. It is probable that their exposure to Cornish fisherfolk was a consistent feature of their time in Yorkshire. Much has been made of their early friendship with the fish auctioneer Jimmy James, but Laura writes too of her visit to the family in Cornwall who had made a yawl, The Truelove, bought and sailed by a Staithes family. Many of her fellow artists such as Fred Richardson had also painted in Cornwall. Her friend Rosie Good had spent a holiday there with her sister Catherine in May 1901, enabling both woment to travel throughout the county and to spend time in both Newlyn and Penzance.

Herring boats coming out of the Beck, 1895

Harold Knight (1874–1961) oil on canvas

50.9 x 60.9 cm opposite

Herring boats coming out of the Beck, 1895

Fred Mayor (1874–1961) oil on canvas

50.9 x 60.9 cm

Herring boats coming out of the Beck, 1895 Harold Knight (1874–1961)

oil on canvas

50.9 x 60.9 cm

Igenet ut hit re lab ipiet ut molupta volore nossum re dus re pa derciduciis il illa quis di quam renducid minciet volest vitation rerovit magnimint am, optatum quam, vendus. Dunt volore ium alit quae plicabo. Nequo omnihit quia veribus sapedip sapedi ad. Ed mossuntem re aut quae. Ut eost et, ium invellaut liquam inulpa porehenima suntior ehenihi cipsunt ionsent quia veremporem archicidella susandero volo tes volupta temolo inctusae pro es es poritat rae nulparuptat harum, ero offictur ra qui ut molorer nature eriatem corro quiam exceaquaes repre.

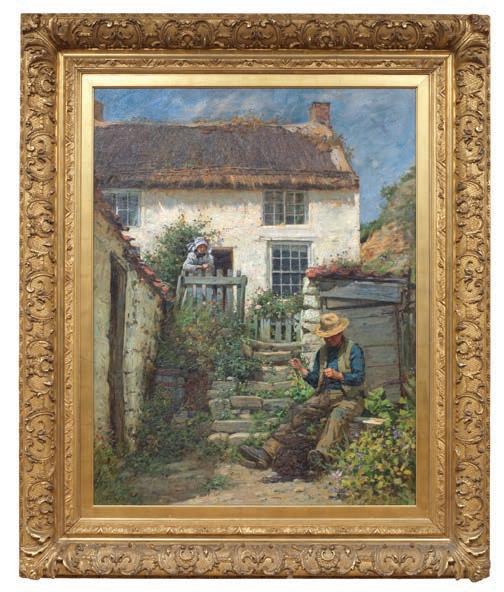

opposite His First Ship

Percy Morton Teasdale (1870–1961) oil on canvas

125.5 x 100 cm

Provenance: Purchased by relatives of John Harold Wood from the Artist’ Studio at Robin Hoods Bay.

, 1903

40 x 30 cm

apparently disappointing period of time he spent in Paris and to the contrasting six-month period in Staithes immediately after their initial time there together.

She remembers thrilling to the advances in his technique while downplaying her own progress. Continuous in her self-criticism, she records the occasional destruction of her own work and failure to find success with exhibition submissions.

This early period of time spent in Staithes is recorded in letters to her friend and one time pupil Rosie Good, and in turn Rosie’s correspondence with her husband-to-be Oliver Sheppard, who seems to have stayed in 1898. All three produced sketchbooks full of work that illustrate both Staithes and their interests in it.

Her aims in sketching are later outlined in her memoir of the same name, in which she reveals: ‘Many days I was out drawing from morning until night. The training I went through in doing notes of moving figures has proved an invaluable asset to later work.’

While Homer and contemporaries Hopwood and perhaps her husband Harold Knight did not seemingly make or keep sketches from which to work in the studio, Laura certainly did:

I prefer every time a picture composed and painted outdoors … it is impossible to paint an outdoor figure in studio light with any degree of certainty … These making studies and then taking them home to the use them is only half right. You get the composition, but you lose freshness; you miss the subtle, and, to the artist, the finer characteristics of the scene itself.

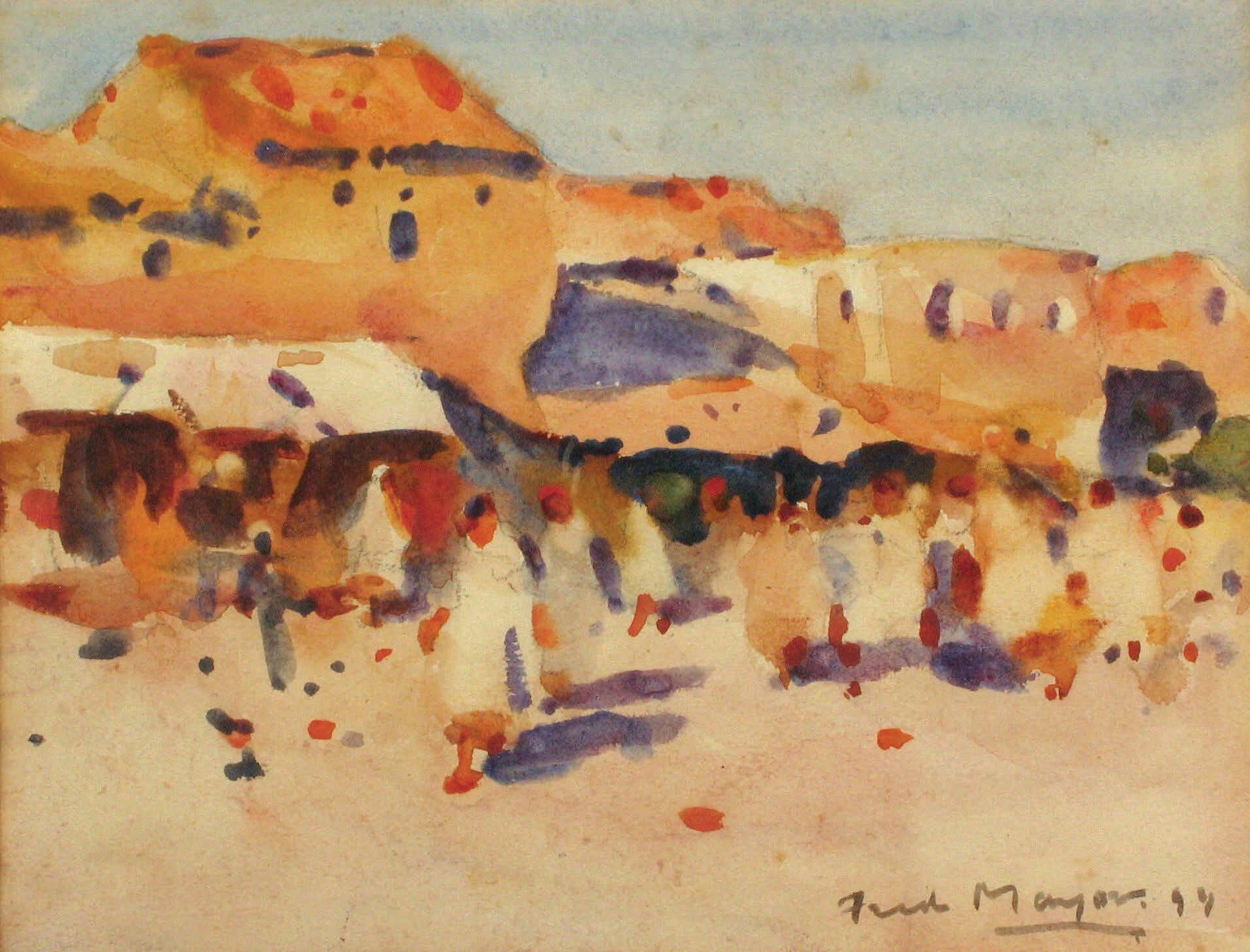

Market scene, 1899

Frank Mayor watercolour on paper 18 x 22 cm

© Hugh Lane Gallery. Cathleen Sheppard Bequest, 1986. © Frank Mayor